Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Identification and Molecular Characterization of the Alkaloid Biosynthesis Gene Family in Dendrobium catenatum

1 College of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China

2 Jiangsu Academy of Forestry, Nanjing, China

3 Jiangsu Yangzhou Urban Forest Ecosystem National Observation and Research Station, Yangzhou, China

* Corresponding Author: Yingdan Yuan. Email:

# These authors contributed equally

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2024, 93(1), 81-96. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2023.045389

Received 25 August 2023; Accepted 22 November 2023; Issue published 26 January 2024

Abstract

As one of the main active components of Dendrobium catenatum, alkaloids have high medicinal value. The physicochemical properties, conserved domains and motifs, phylogenetic analysis, and cis-acting elements of the gene family members in the alkaloid biosynthesis pathway of D. catenatum were analyzed by bioinformatics, and the expression of the genes in different years and tissues was analyzed by qRT-PCR. There are 16 gene families, including 25 genes, in the D. catenatum alkaloid biosynthesis pathway. The analysis of conserved domains and motifs showed that the types, quantities, and orders of domains and motifs were similar among members of the same family, but there were significant differences among families. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the gene family members showed some evolutionary conservation. Cis-acting element analysis revealed that there were a large number of light-responsive elements and MYB (v-myb avian myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog)-related elements in these genes. qRT-PCR showed that expressions of gene family members involved in alkaloid synthesis were different in different years and tissues of D. catenatum. This study provides a theoretical basis for further exploration of the regulatory mechanisms of these genes in the alkaloid biosynthesis of D. catenatum.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileAbbreviations

| DXS | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase |

| DXR | 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase |

| MCT | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate cytidylyl-transferase |

| CMK | 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase |

| MDS | 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase |

| HDS | 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-butenyl 4-diphosphate synthase |

| HDR | 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-butenyl 4-diphosphate reductase |

| FPPS | Farnesyl diphosphate synthase |

| AACT | Acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase |

| HMGS | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase |

| HMGR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase |

| MVK | Mevalonate kinase |

| PMK | Phosphomevalonate kinase |

| MPDC | Mevalonate diphosphosphate decarboxylase |

| IPPI | Isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase |

| GGPPS | Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase |

D. catenatum is a perennial herb of the orchid family Dendrobium, mainly distributed in Southeastern, Southern, and Southwest China [1]. Dendrobium plants have high medicinal value and are widely used in traditional Chinese medicine [2]. Dendrobium has special pharmacological effects on resisting aging [3] and treating gastritis [4], diabetes [5], and cancer [6]. It has been used as a folk medicine in China for more than 2,000 years [7]. The main active components of Dendrobium include alkaloids [8], polysaccharides [9], and polyphenolic compounds [10], of which alkaloids are the main medicinal components, with significant antioxidant [11], anticancer [12], analgesia [13], neuroprotection [14], and other effects. D. catenatum is one of the most famous Dendrobium species in China but is now on the brink of extinction due to its widespread use in healthcare [15–17] and has been listed as one of the rare medicinal plants in China [18].

Alkaloids have been said to be important biomarkers because of their complex chemical structure and variety [19]. These include pyrrole, indolizidine, terpenoid alkaloids, organic amine alkaloids, indole, quinazoline, and others [20]. Most of the alkaloids in D. catenatum are terpenoid indole alkaloids [21], which are concentrated in the leaves. The amount of alkaloids in the leaves is between 0.0291% and 0.0421% [22], which is less than the total alkaloid content of related Dendrobium species [23]. However, the alkaloids produced by D. catenatum are of higher quality than other related species [24]. The upstream biosynthetic pathway of D. catenatum alkaloids consists of the conserved MVA pathway and MEP pathway, providing the basic skeleton for terpenoid alkaloids [25]. There are a series of P450 monooxygenases and aminotransferases following strictosidine in the downstream of Dendrobium alkaloid synthesis pathway [23]. Cytochrome P450 is involved in oxidation and hydroxylation reactions, and aminotransferases convert amino acids to form alkaloids [26].

In recent years, with the publication of the complete gene sequence of Dendrobium [27,28], there have been many studies on genes related to alkaloid biosynthetic pathways in Dendrobium. For instance, Yuan et al.’s transcriptome analysis of Dendrobium huoshanense revealed numerous differentially expressed genes involved in the production of alkaloids in various samples, and they also confirmed the expression patterns of the five important enzyme genes involved in terpenoid pathway in different tissues [29]. Transcriptome analysis revealed related genes and genetic markers in alkaloid biosynthesis pathways in D. catenatum, including 25 alkaloid backbone biosynthesis genes, P450 genes, transaminase genes, methyltransferase genes, multidrug resistance protein transporter protein genes, and transcription factor genes [23]. By using MeJA, alkaloid biosynthesis was induced and abundant MeJA-induced transcription factor-encoding genes were found, indicating that the genetic network that affect the metabolism of terpenoid alkaloids in D. catenatum is very complex [30]. By analyzing transcripts from four organs of D. catenatum, genes associated with putative upstream elements of the alkaloid biosynthesis pathway in D. catenatum were identified [31]. Song et al. introduced the biosynthetic pathways and associated gene clusters for each class of alkaloids in Dendrobium [32]. Wang et al. analyzed the correlation between gene expression levels and metabolite content from comparative transcriptome sequencing of different organs of D. catenatum, identifying putative genes for enzymes involved in alkaloid biosynthesis [33]. These studies have made great contributions to the further development and application of Dendrobium alkaloids, but there is a lack of studies on the structure and function of gene families related to the alkaloid biosynthesis of Dendrobium, and their roles in complex regulatory networks are not well understood. Therefore, in this article, we conducted a more in-depth understanding and mining of related gene families in the alkaloid biosynthesis of D. catenatum.

In this study, we identified 16 types of gene family members in the alkaloid biosynthesis pathway by using D. catenatum genome data as a resource platform and using relevant bioinformatics methods. The physicochemical properties, gene structure, phylogeny, and cis-acting elements of the encoded protein were analyzed. Quantitative analysis of D. catenatum in different years and different tissues was performed using qRT-PCR to verify the differential regulation of structural genes in the alkaloid biosynthesis pathway. Our research will help to further interpret the molecular mechanism of D. catenatum alkaloid biosynthesis and regulation and can also provide references for alkaloid research in other Dendrobium species.

The D. catenatum stems were grown in the greenhouse of Jiangsu Yangzhou Urban Forest Ecosystem National Observation and Research Station, China. Half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) culture media supplemented with 6-BA 0.1 mg·L−1, NAA 0.5 mg·L−1 and 1% additives (30 g·L−1 sucrose + 4 g·L−1 agar + 20% potato) were used for seed germination and protocorm-like body. The plants were cultured at 25°C ± 2°C and the photoperiod was 12/12 h (day/night, 30 μmol·m−2·S−1). After 18 months, the plants were transplanted into a greenhouse pot, the environmental conditions were 25°C–27°C, the day and night light was 12/12 h and the relative humidity was 60%–70%. They were sampled at one, two, three and four years of age. Annual, biennial, triennial, and quadrennial D. catenatum stems were collected and then frozen quickly in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction.

2.2 Data Mining and Identification of Alkaloid Biosynthetic Genes

By the A. thaliana Information Resource (TAIR) database, sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana AtDXS, AtDXR, AtMCT, AtCMK, AtMDS, AtHDS, AtHDR, AtAACT, AtHMGS, AtHMGR, AtMVK, AtPMK, AtMPDC, AtIPPI, AtFPPS, and AtGGPPS were downloaded (Supplementary file 1 Table S1). By using BLAST program (E-value < 1e-5) in TBtools (v1.098745), the protein sequence for identifying homologous genes in the D. catenatum genome was inquired. The sequences obtained were compared with NCBI database by BLASTp program and corrected manually. The conserved domains of obtained candidate protein sequences were predicted by the Pfam database (v35.0) (http://pfam.xfam.org/) and manually removed incomplete conserved structural domains. Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) database (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) was used to verify conserved domains. Finally, 25 protein sequences with conserved structural domains corresponding to 16 gene families were obtained and named.

2.3 Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Gene Structure

ExPASy (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/) was used to predict proteins’ physical and chemical properties, such as length, molecular weight, isoelectric point, instability index, fat index, and hydrophilic average. The online tool WOLF PSORT (http://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) was used to predict the subcellular localization of proteins encoded by genes in the alkaloid biosynthesis pathway of D. catenatum. The program SOPMA secondary structure prediction (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl/page=npsa_sopma.html) was used for predicting the secondary structure of members of gene families, including α-helix, β-fold, extended chain, and irregular crimp ratio.

2.4 Analysis of the Domain and Conservative Motif

Pfam was used to predict protein domains of members of gene families and the protein domain map was created. Conserved motifs of proteins encoded by all members of the gene family were predicted by MEME (http://meme.nbcr.net/meme/). It was set to 15 as the maximum motif number and the rest of the values were set to default. TBtools was used to visualize the results of the analysis in conjunction with the phylogenetic tree [34].

2.5 Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

As part of the analysis of evolution within and between gene families of alkaloid biosynthesis in D. catenatum, the protein sequences of 32 genes involved in alkaloid biosynthesis have been downloaded from the TAIR database and we downloaded the protein sequences of 131 genes from 47 species from the NCBI database. The obtained gene precursor sequences were compared using ClustalX2.1 online software, and the results were entered into MEGAX [35,36]. Based on the adjacency method (Nearby-joining, NJ), phylogenetic trees of gene families were constructed for the D. catenatum genome and complex multi-species. We set the Bootstrap value to 1000, and the other parameters were set to the system defaults.

2.6 Prediction of Cis-Acting Elements

The promoter sequences for gene family members (2000 bp upstream of transcriptional initiation sites) were obtained from the genome of D. catenatum. Plant CARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) was used for predicting cis-acting elements and visually mapped by using TBtools [34].

2.7 Expression Analysis of Alkaloid Biosynthesis Gene Family

The alkaloid biosynthesis gene family was resolved using tissue-specific and different growth years analysis with the online database NCBI, then we downloaded the raw data from the NCBI database (PRJNA476016 and PRJNA776680), and the expression level of these genes was extracted [37,38]. To estimate the gene expression based on the Fragments Per Kilobase of the gene model per Million fragments mapped (FPKM), RSEM (v1.2.15) with default parameters was employed [39].

2.8 RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

Omni Plant RNA kit (CWBIO, China) was used to check the purity of total RNA extracted from D. catenatum stems. cDNA was converted from two hundred ng Poly(A)+ mRNA from different samples at 42°C in a 20 μL reaction volume by AMV Reverse Transcriptase. Gene-specific primers were designed by Oligo 7 (Supplementary file 1 Table S2). Amplification conditions of all PCRs were performed as follows: 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 15 s at 50°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Based on the expression level of the Actin gene (GenBank accession number: KC831582.1) in D. catenatum as the reference gene [40]. The expression level of the target gene was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method [41]. The qRT-PCR was performed by using the ABI 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA).

3.1 Identification and Characterization of the Alkaloid Biosynthetic Gene Family in D. catenatum

Sixteen gene families in the alkaloid synthesis pathway of D. catenatum were identified and 25 enzyme genes were obtained in this study. “Dc” was used as a prefix for the genes in the D. catenatum alkaloid synthesis pathway and sorted the genes according to their chromosome position. The number of these 16 gene family members in D. catenatum and A. thaliana were compared (Fig. 1). It was found that there were 13 GGPPS gene family members in A. thaliana, while only 3 in D. catenatum. The remaining 15 gene family members in D. catenatum, except for GGPPS, were similar in number to those in A. thaliana.

Figure 1: Comparative analysis of gene numbers in families in the alkaloid biosynthesis pathway in D. catenatum and A. thaliana. The pink and blue boxes indicate the number of genes in D. catenatum and A. thaliana, respectively

In addition, the physicochemical properties, subcellular localization, and secondary structure of these 25 proteins were analyzed and compared, which ranged from 137 (DcMDS1) to 745 (DcHDS) amino acids in length, with an average length of 407. The grand average of hydropathicity for these proteins ranged from −0.440 (DcHDR) to 0.307 (DcHMGR3), and there were 16 hydrophilic proteins and 9 hydrophobic proteins (Supplementary file 1 Table S3). Subcellular localization showed that 16 genes were localized in chloroplasts, 4 in cytoplasmic stroma, 2 in mitochondria, 1 in endoplasmic reticulum, 1 in plasma membrane, and 1 in chloroplasts and endoplasmic reticulum (Supplementary file 2). These proteins have four types of structures, including alpha-helix, beta-turn, random coil, and extended strand. The major secondary structure types of these proteins were alpha helix and random coil, accounting for 24.82%–63.51% and 27.24%–53.28%, respectively. Beta turn accounted for 2.30%~10.15%, and extended strand accounted for 5.19%~25.89% (Supplementary file 3).

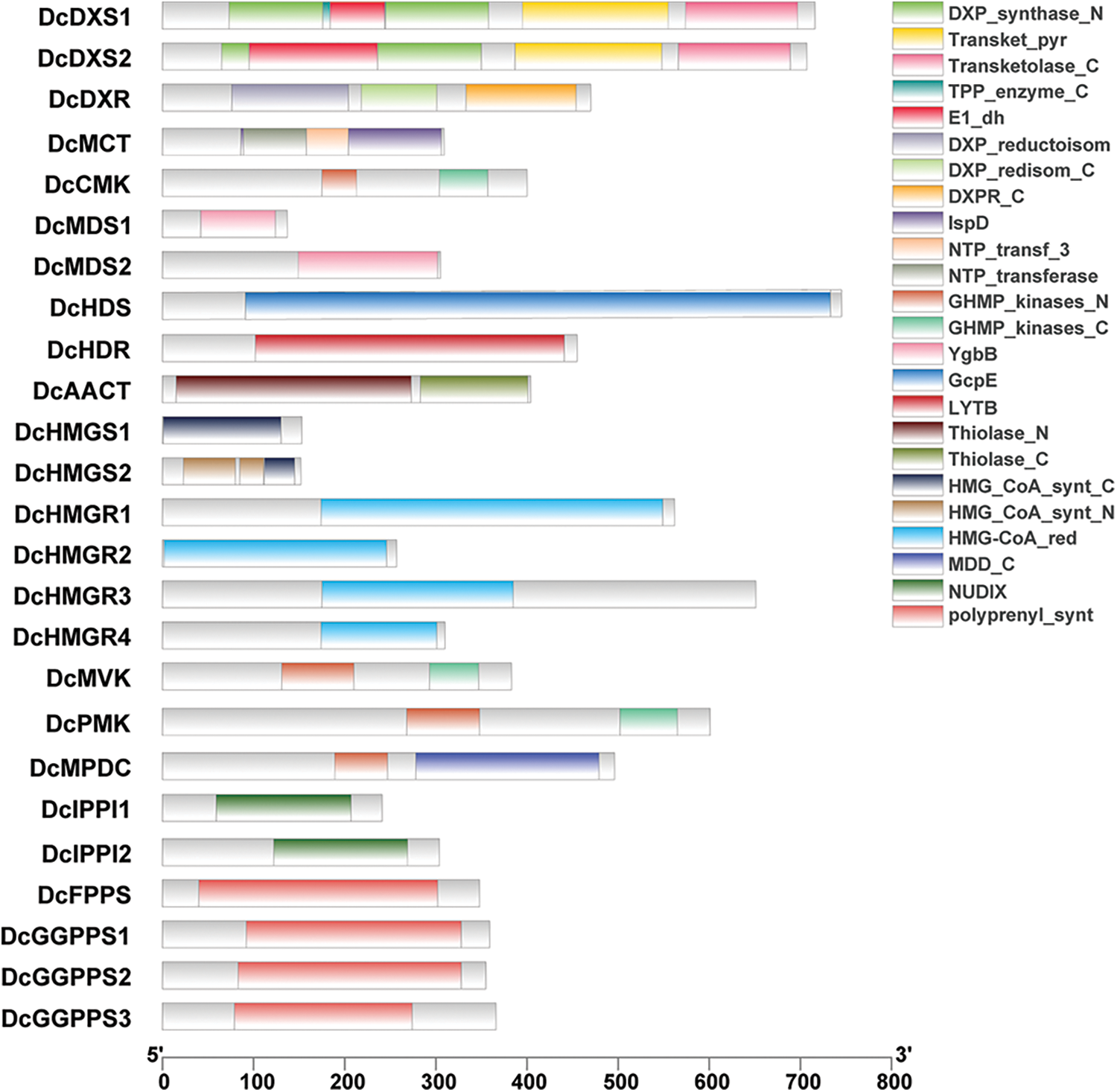

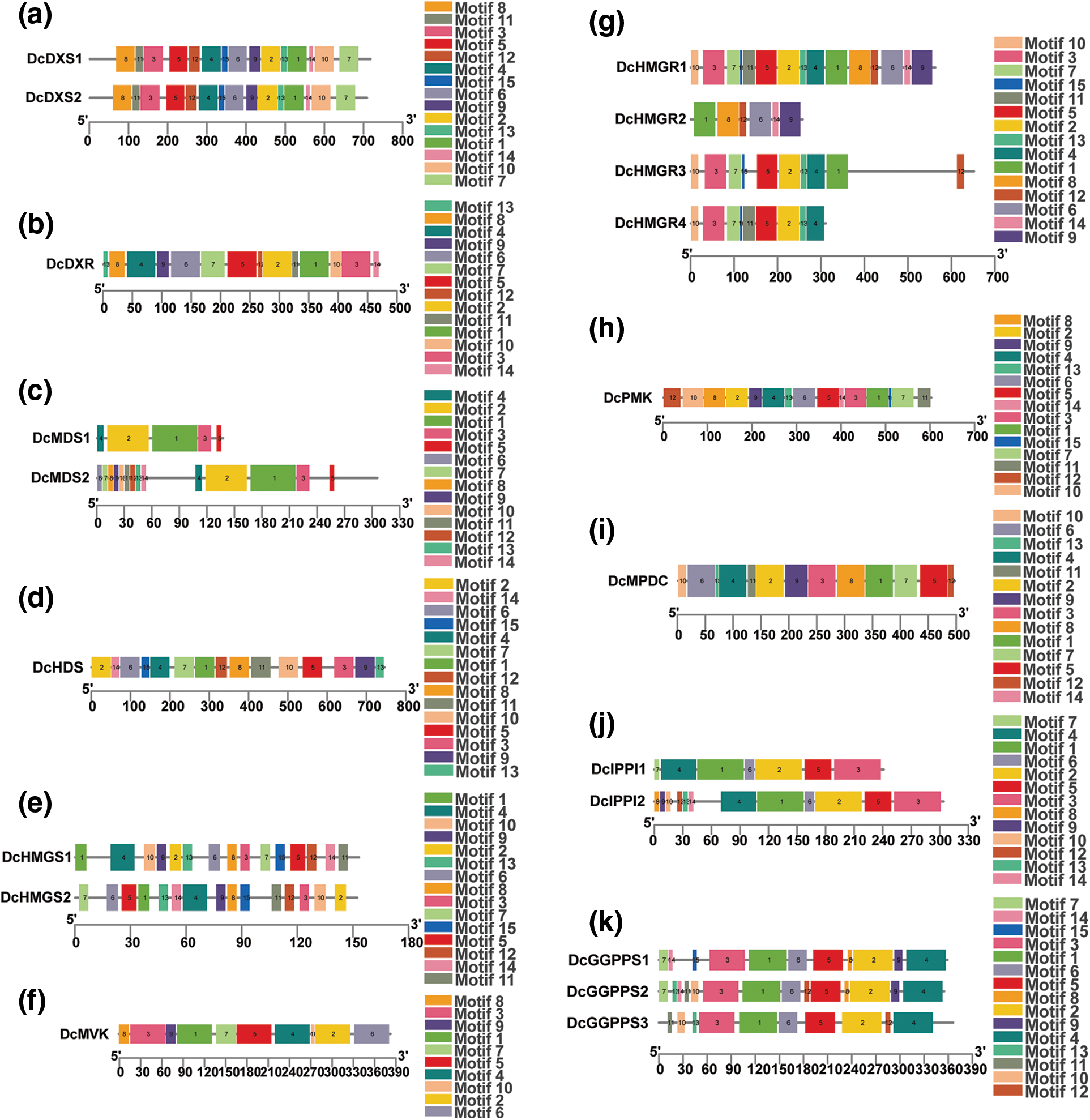

3.2 Structural Analysis and Protein Domain Prediction of Genes Related to Alkaloid Biosynthesis

In order to clarify the structure and function of gene families related to the D. catenatum alkaloid biosynthesis pathway, the conserved domains of 25 genes in these gene families were identified and compared, and the domain composition was explored (Fig. 2). It was found that members of the same protein family share the same conserved domains which are not specific to one family. For example, DcFPPS and DcGGPPS both contain polyprenyl_synt; DcCMK, DcMVK, and DcPMK all contain GHMP_kinases_C; DcCMK, DcMVK, DcPMK and DcMPDC all contain GHMP_kinases_N. In addition, motifs of proteins in gene families were analyzed the conserved. It was found that proteins have multiple conserved motifs with similar types, numbers, and order in the same gene family (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Protein domain analysis. Different colors represent different structural domains

Figure 3: Analysis of conserved motifs of proteins. Different colored squares represent different motifs. (a) DcDXS, (b) DcDXR, (c) DcMDS, (d) DcHDS, (e) DcHMGS, (f) DcMVK, (g) DcHMGR, (h) DcPMK, (i) DcMPDC, (j) DcIPPI, (k) DcGGPPS

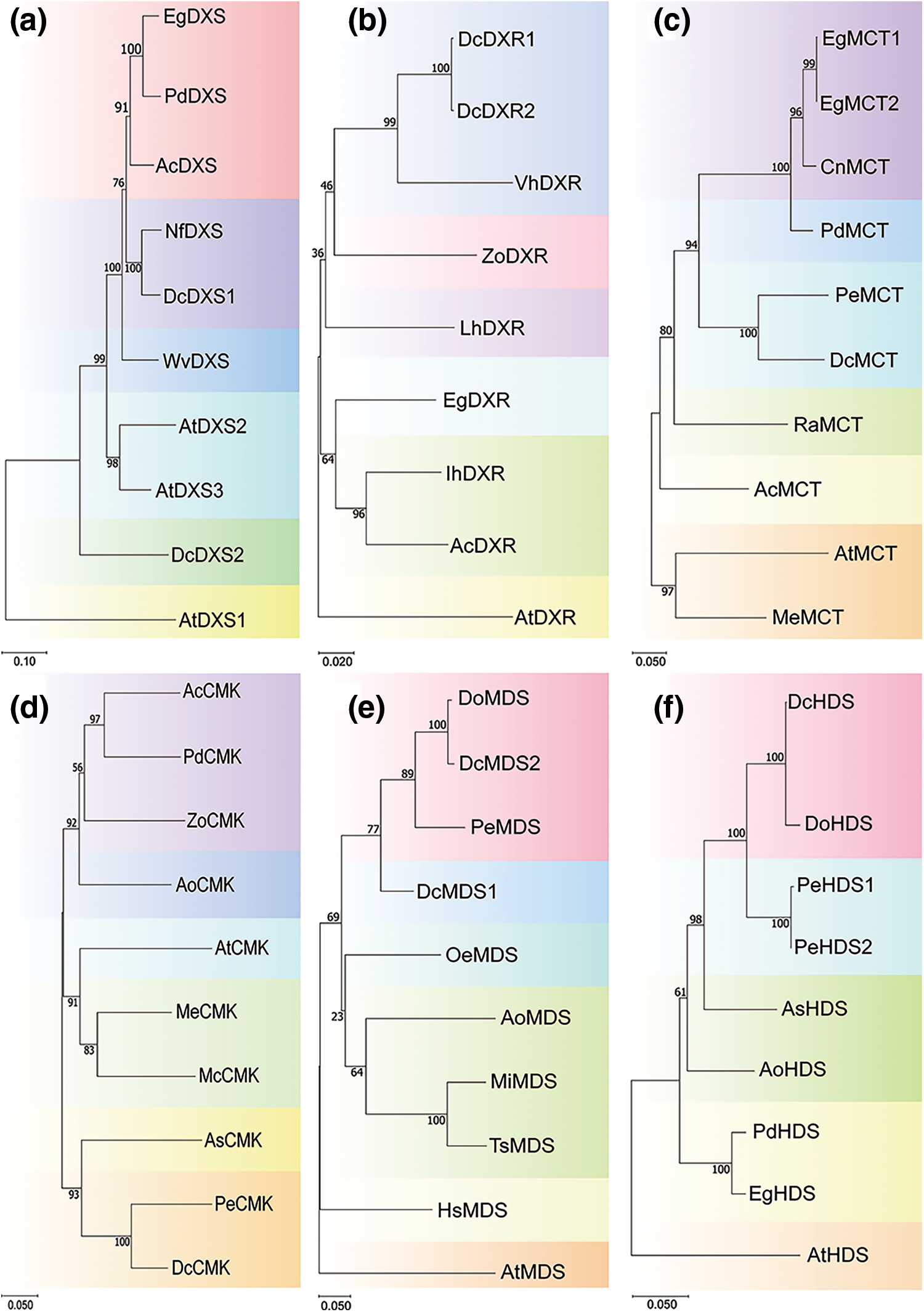

3.3 Phylogenetic Analysis of Gene Families

A phylogenetic tree of each gene family was constructed to clarify the evolutionary relationships of these 16 gene family members between D. catenatum and other species (Fig. 4, Supplementary file 1 Figs. S1 and S2). Notably, the two members of the DcDXS family are evolutionarily distant. In the DcHMGR family, unlike DcHMGR1 and DcHMGR2, DcHMGR3 and DcHMGR4 are evolutionarily distant from the HMGR in other plants. In the DcGGPPS family, DcGGPPS3 is located in a separate small evolutionary branch, away from the genes of other species. All family members of DcDXR, DcPMK, and DcIPPI are on a small evolutionary branch.

Figure 4: Phylogenetic analysis of genes in different species. (a) DXS, (b) DXR, (c) MCT, (d) CMK, (e) MDS, (f) HDS

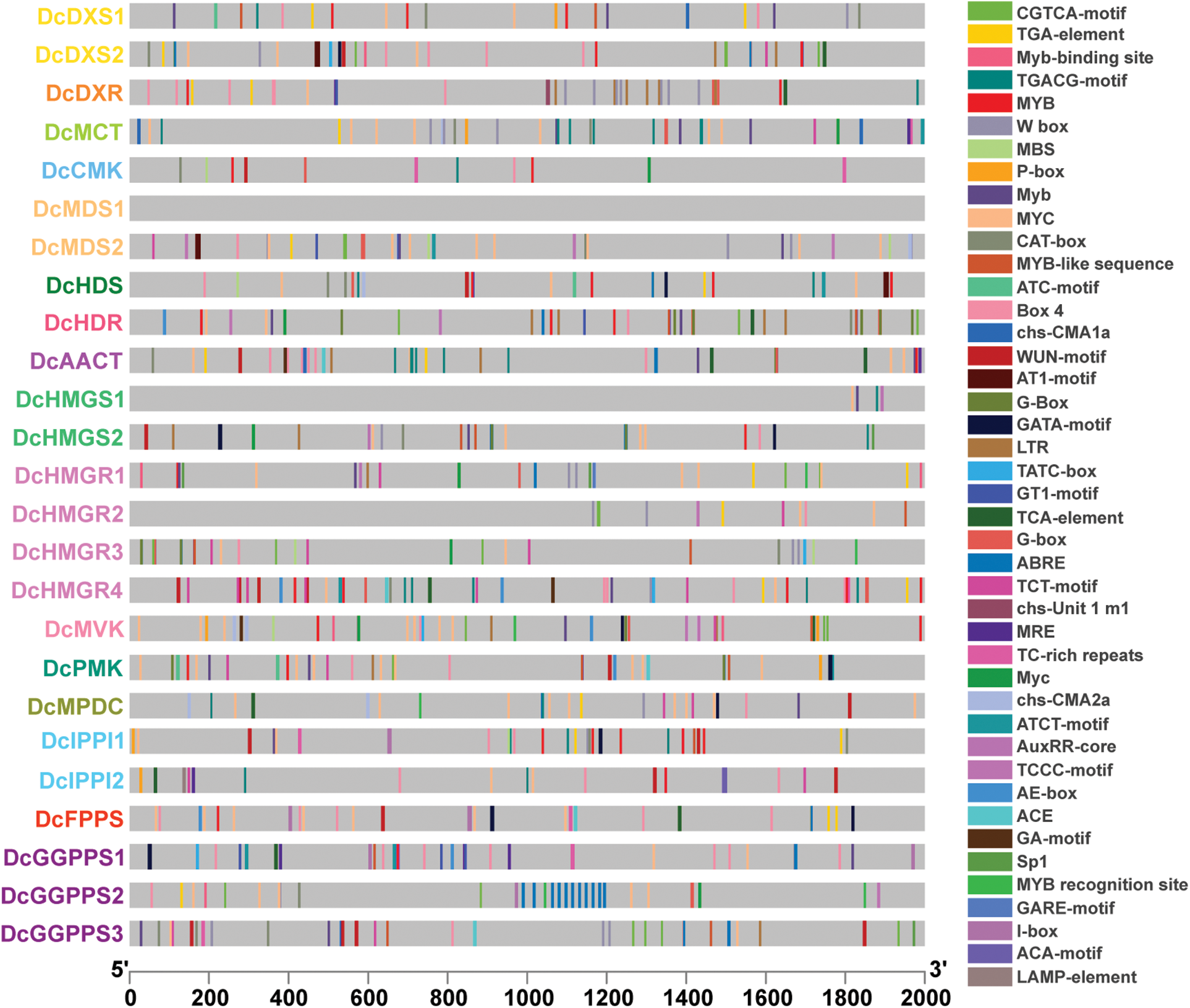

3.4 Promoter Cis-Acting Element Analysis

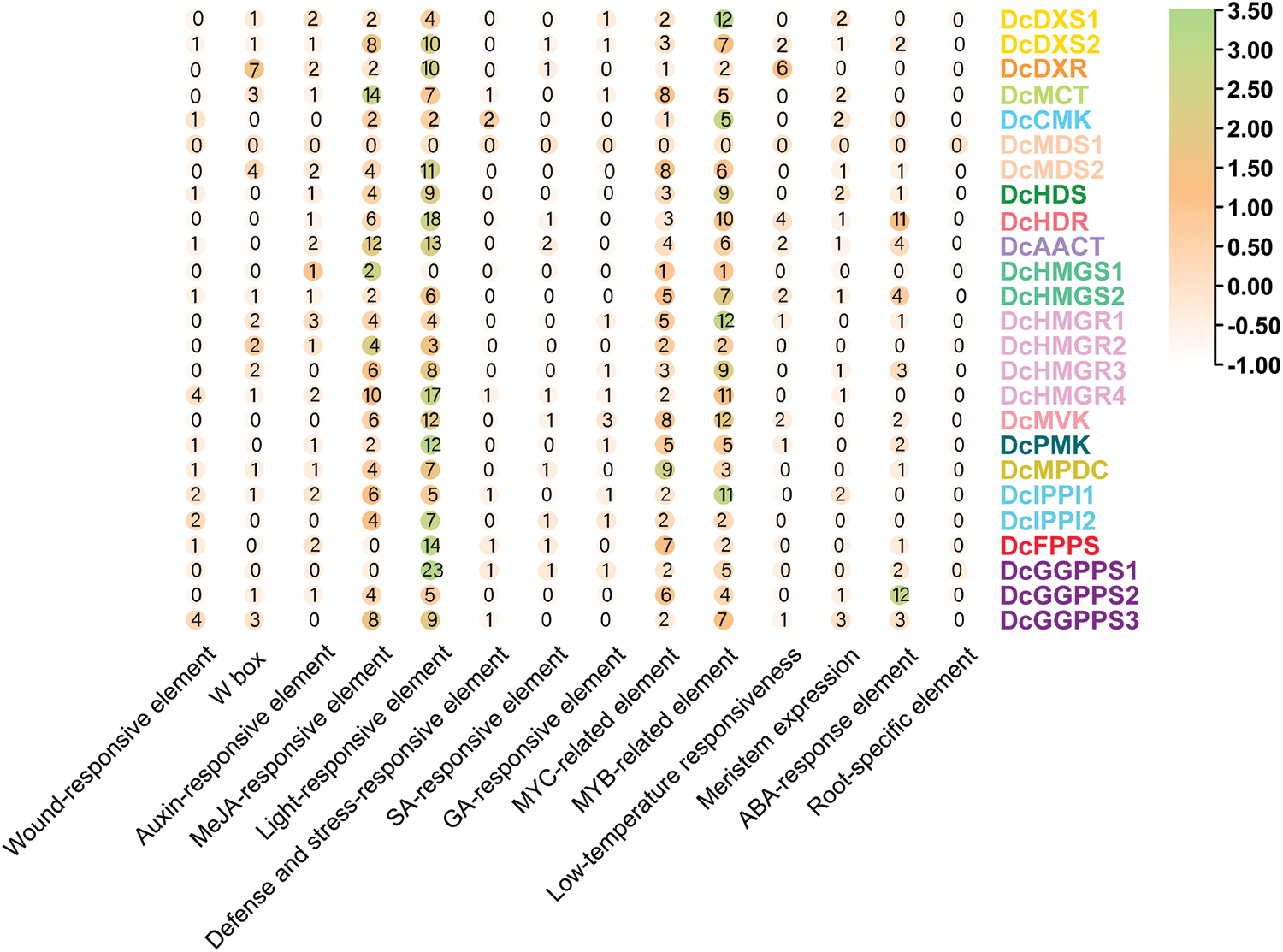

To determine the potential biological roles of these genes in D. catenatum, cis-acting elements were identified in the promoter regions of these genes (Fig. 5). Except DcMDS1, a total of 43 cis-acting elements in the promoters of other genes were detected. The promoters of these 24 genes contain 5-55 cis-acting elements and with an average of 32. DcHDR had the most cis-acting elements, while DcHMGS1 contained the fewest cis-acting elements. These cis-acting elements are associated with plant growth and development, hormone response, and stress response. For example, MRE is related to flowering, CAT-box is related to shooting and root meristem tissue expression; MBS is related to drought induction, LTR is related to low temperature stress; ABRE is related to abscisic acid, and TGA-element related to growth hormone.

Figure 5: Cis-acting element analysis of promoters. Different colored squares represent different cis-acting elements

The occurrence of 14 cis-acting elements in each gene were counted and analyzed (Fig. 6). In the heatmap, the frequency of cis-acting elements was similar for these 25 genes. The light-responsive element was the most prevalent among almost all genes, especially in DcHDR, DcAACT, DcHMGR, DcMVK, DcPMK, DcFPPS, and DcGGPPS families. MeJA-responsive element, MYC-related element, and MYB-related element also appeared more frequently. In addition, the ABA-response element was more abundant in DcHDR and DcGGPPS2, but very few or even absent in other genes. In addition to the root-specific element, the remaining eight elements were detected, but in very small numbers and distributed only in individual gene families.

Figure 6: The number of heatmap clustering occurrences of cis-acting elements in the promoter sequences

3.5 Gene Expression Analysis of Different Samples of D. catenatum

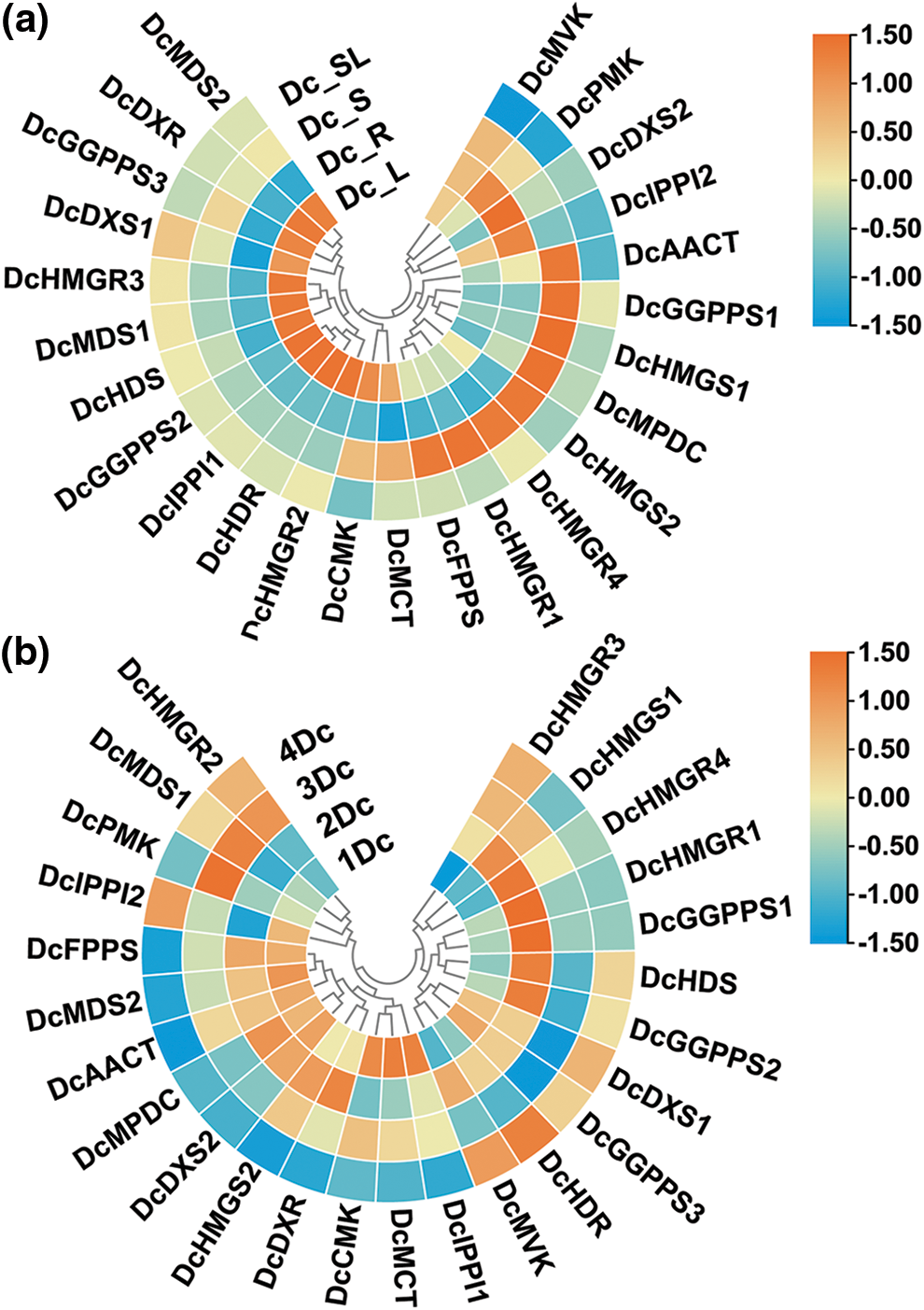

To explore the regulatory functions of genes in D. catenatum, we compared the expression of these genes in different tissues of biennial D. catenatum (Fig. 7a). Interestingly, the expression of these genes was generally low in the aboveground parts. DcAACT, DcGGPPS1, DcHMGS1, DcMPDC, DcHMGS2, DcHMGR4, DcHMGR1, and DcFPPS were highly expressed in the stem but lowly in the root, leaf, and aboveground parts, suggesting that they may play a regulatory role in the stem. DcDXS2 was highly expressed in the roots and lowly in the stems, leaves, and aboveground parts, indicating that it may play a regulatory role in the roots.

Figure 7: Heatmap of gene expression. (a) Heat map of gene expression in different tissues of biennial D. catenatum. (b) Heatmap of gene expression at different years of stem. Expression levels are indicated using a color scale from blue (low expression) to red (high expression)

In addition, the expression of 25 genes was analyzed in four different years in the stem of D. catenatum (annual, biennial, triennial, and quadrennial, respectively) (Fig. 7b). The results showed that the expression levels of these genes were highly variable among the samples of different years, but there was some similarity. DcHMGR1 and DcGGPPS1 were highly expressed in biennial D. catenatum and lowly expressed in other years. DcDXS1, DcDXR, DcAACT, DcHMGS2, DcIPPI1, and DcGGPPS3 genes were highly expressed, which indicated that these genes may play an important regulatory role in the alkaloid biosynthetic pathway. We also found that the expression levels of different members of the same family differed in different years. For example, DcMDS1 was expressed at low levels in annual and biennial D. catenatum and at higher levels in triennials and quadrennials, while DcMDS2 was the opposite.

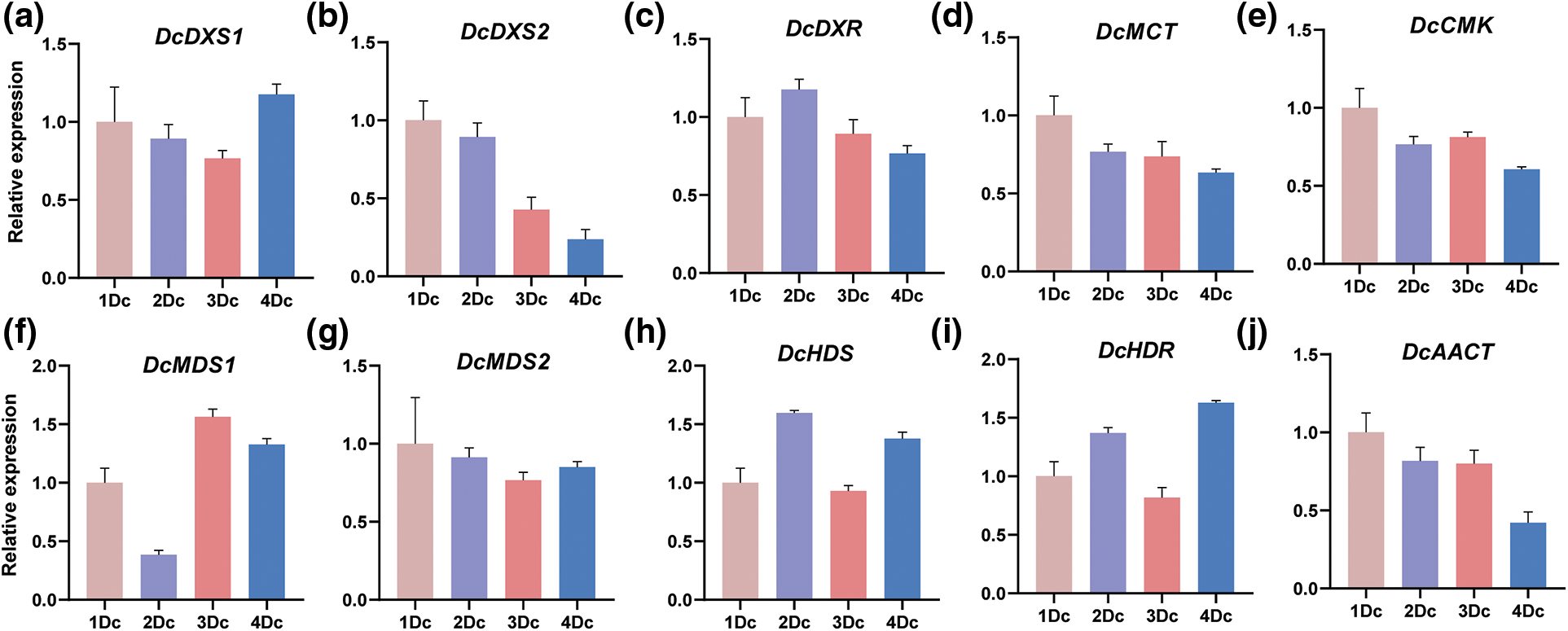

To further investigate the expression of alkaloid biosynthetic pathway gene family members in different years of D. catenatum, we selected 10 genes and determined their expression in four different years of plants using qRT-PCR. The results showed that the expression was relatively high in annual and biennial samples, and the expression of different genes in the triennial and quadrennial samples had large differences (Fig. 8). The highest expression of DcMDS1 and the lowest expression of DcDXS2 were found in the triennial samples. Therefore, we speculate that genes related to D. catenatum alkaloid biosynthesis have different functional and regulatory effects in different years.

Figure 8: qRT-PCR of D. catenatum in different years. 1Dc indicates annual D. catenatum, 2Dc indicates biennial D. catenatum, 3Dc indicates triennial D. catenatum and 4Dc indicates quadrennial D. catenatum. The error bars indicate the mean ± SD (n = 3)

The alkaloid extracted from D. catenatum is a natural product with significant biological activity, with neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-tumor activity effects [8]. Genes related to alkaloid biosynthesis have been identified in other species, such as the model plants of alkaloid biosynthesis Nicotiana tabacum [42], Catharanthus roseus [43], Sophora flavescens [44], and Papaver somniferum [45]. Currently, studies on secondary metabolites of D. catenatum have focused on phenylpropanoids such as flavonoids [46] and anthocyanins [47]. The distribution of terpenoids in D. catenatum was determined by Zhan et al. [48]. It was found that Dendrobium alkaloid biosynthesis could be induced by MeJA treatment [30] and mycorrhizal fungal infestation [49]. AgNP applications significantly increased the indole alkaloid indirubin production in the shoot cultures of Isatis tinctoria and Isatis ermenekensis [50]. 14 potential genes associated with D. catenatum alkaloid biosynthesis were identified by Chen et al. which are similar to our identification [30]. There are few gene family analyses based on genome-wide identification of entire secondary metabolites, and all gene families on the flavonoid biosynthesis have been identified only in Ginkgo [51] and Salvia [52]. However, systematic analysis of all gene families in alkaloid biosynthesis has not been studied. In this study, bioinformatic analysis of 25 genes in 16 gene families of alkaloid biosynthesis in D. catenatum has laid the foundation for studying the gene regulatory network of D. catenatum alkaloids.

By structural analysis of these 25 genes, we found that the conserved structural domains exhibited significant differences among different family members. However, in the same family, there may also be differences in the composition of the conserved structural domains. For example, in the DcDXS family, compared to DcDXS2, DcDXS1 has an additional conserved structural domain TPP_enzyme_C. In the conserved motif analysis, there were also differences between members of the same family, indicating that these genes are likely to also perform certain specific functions. The analysis of conserved domains and motifs revealed the structural diversity of gene family members in D. catenatum, which laid an important foundation for the subsequent exploration of the functional diversity of related gene families. We also constructed a multispecies evolutionary tree to screen for genes of other species with similar evolutionary relationships to functional genes. In constructing the evolutionary tree, we found that two family members of DcHMGS could not be made in the same evolutionary tree, and the remaining genes and homologs were in a large evolutionary branch. However, each of the two members of DcHMGS can form an evolutionary tree with the HMGS of other species. Therefore, we speculate that the HMGS gene was broken into two genes due to problems in genome sequencing or analysis. Phylogenetic analysis showed that members of the gene family were mostly clustered together, while a few genes were loosely distributed. The DcDXR family is evolutionarily closely related to VhDXR. Previous studies have shown that the transcription level of DXR is higher in florescence and full florescence of Vanda and regulates the generation of odor [53]. We guess that the DXR family in D. catenatum plays a role in regulating the generation of floral odor. DcPMK and AtPMK are not in the same branch and are far apart in an evolutionary relationship, which indicates that the PMK family plays different regulatory roles in these two species. Our results show that members of different gene families have different functions in the evolutionary process, which provides a way to predict the relationship between gene functions and specific biological processes.

Cis-acting elements are important molecular switches that participate in the transcriptional regulation of gene activity dynamic networks and control various biological processes, including abiotic stress responses, hormone responses, and developmental processes [54]. Through cis-acting element analysis, we found that except for DcMDS1 and DcHMGS1, light-responsive elements appeared in a large number of other genes, so we speculated that these genes participated in and responded to plant photomorphogenesis. In addition, the MeJA-responsive element appears frequently in the gene. It has been shown that MeJA treatment can induce D. catenatum alkaloid biosynthesis [30]. We identified a large number of hormone response elements and stress response elements in different quantities and types and speculated that D. catenatum alkaloid biosynthesis-related genes can respond to stimulation and hormone signal transduction.

To sum up, 16 gene families in D. catenatum alkaloid biosynthesis were identified in this study, and 25 genes were obtained. The protein structure, physicochemical properties, subcellular localization, evolutionary relationship, cis-acting elements of the promoter, and expression level of the gene were analyzed. By analyzing the expression level of gene family members in the alkaloid biosynthesis in different years and tissues of D. catenatum, it was found that the gene expression levels varied greatly in different years and different tissues. For example, the expression level of DcHMGR1 in the stems of biennial D. catenatum was significantly higher than that in other years. Therefore, our future research on plant genetics and stress resistance will pay more attention to the expression level of specific genes in specific years and tissues of D. catenatum. These gene family members not only play an important role in alkaloid biosynthesis, but also participate in stress and hormone response, and play an important regulatory role in plant growth and development. This study revealed the characteristics of 16 gene families in alkaloid synthesis, which is helpful to further explore the structure and function of these family members.

Acknowledgement: This project funded by the Forestry Science and Technology Innovation and promotion Project of Jiangsu Province ‘Long-Term Research Base of Forest and Wetland Positioning Monitoring in Jiangsu Province’ (Grant No. LYKJ [2020]21), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (Grant No. BK20210800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 32001341 and 32202523) and Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund (Grant No. CX (21)3047).

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: L. Yang: conceptualization; data curation; resources; software; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. X. Wan: conceptualization; data curation; investigation; resources; visualization; writing—review and editing; writing—review and editing. R. Zhou: visualization; writing—review and editing. Y. Yuan: conceptualization; funding acquisition; resources; supervision; validation; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original contributions presented in the study are included the article and in Supplemental Materials. Further inquiries should be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: This article does not contain any studies with animals or humans performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2023.045389.

References

1. Hou B, Luo J, Zhang Y, Niu Z, Xue Q, Ding X. Iteration expansion and regional evolution: phylogeography of Dendrobium officinale and four related taxa in Southern China. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

2. Teixeira da Silva JA, Ng TB. The medicinal and pharmaceutical importance of Dendrobium species. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101(6):2227–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-017-8169-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yoon MY, Hwang JH, Park JH, Lee MR, Kim HJ, Park E, et al. Neuroprotective effects of SG-168 against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. J Med Food. 2011;14(1–2):120–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Wang Y, Chu F, Lin J, Li Y, Johnson N, Zhang J, et al. Erianin, the main active ingredient of Dendrobium chrysotoxum Lindl, inhibits precancerous lesions of gastric cancer (PLGC) through suppression of the HRAS-PI3K-AKT signaling pathway as revealed by network pharmacology and in vitro experimental verification. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021a;279:114399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Li M, Zhang B, He S, Zheng R, Zhang Y, Wang Y. Elucidating hypoglycemic mechanism of Dendrobium nobile through auxiliary elucidation system for traditional Chinese medicine mechanism. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2015;40(19):3709–12 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Song JI, Kang YJ, Yong HY, Kim YC, Moon A. Denbinobin, a phenanthrene from Dendrobium nobile, inhibits invasion and induces apoptosis in SNU-484 human gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2012;27(3):813–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Cheng J, Dang PP, Zhao Z, Yuan LC, Zhou ZH, Wolf D, et al. An assessment of the Chinese medicinal Dendrobium industry: supply, demand and sustainability. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;229:81–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Duan H, Er-bu A, Dongzhi Z, Xie H, Ye B, He J. Alkaloids from Dendrobium and their biosynthetic pathway, biological activity and total synthesis. Phytomedicine. 2022;102:154132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Jiang M, Li S, Zhao C, Zhao M, Xu S, Wen G. Identification and analysis of sucrose synthase gene family associated with polysaccharide biosynthesis in Dendrobium catenatum by transcriptomic analysis. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Zhang X, Gao H, Wang N, Yao X. Phenolic components from Dendrobium nobile. Zhong Cao Yao. 2006;652–5 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

11. Ng TB, Liu J, Wong JH, Ye X, Wing Sze SC, Tong Y, et al. Review of research on Dendrobium, a prized folk medicine. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(5):1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

12. Kim YR, Han AR, Kim JB, Jung CH. Dendrobine inhibits γ-irradiation-induced cancer Cell migration, invasion and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Biomedicine. 2021;9(8):954. [Google Scholar]

13. Hasriadi, Wasana PWD, Sritularak B, Vajragupta O, Rojsitthisak P, Towiwat P. Batatasin III, a constituent of Dendrobium scabrilingue, improves murine pain-like behaviors with a favorable CNS safety profile. J Nat Prod. 2022;85(7):1816–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Wang Q, Gong Q, Wu Q, Shi J. Neuroprotective effects of Dendrobium alkaloids on rat cortical neurons injured by oxygen-glucose deprivation and reperfusion. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(2):108–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Halberstein RA. Medicinal plants: historical and cross-cultural usage patterns. Ann Epidem. 2005;15(9):686–99. [Google Scholar]

16. Shoemaker M, Hamilton B, Dairkee SH, Cohen I, Campbell MJ. In vitro anticancer activity of twelve Chinese medicinal herbs. Phytother Res. 2005;19(7):649–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Wojcikowski K, Gobe G. Animal studies on medicinal herbs: predictability, dose conversion and potential value. Phytother Res. 2014;28(1):22–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

18. Xi G, Zhao G. Advances in the cultivation techniques of Dendrobium officinale. Medicinal Plant. 2012;3(5):67–70. [Google Scholar]

19. Mou Z, Zhao Y, Ye F, Shi Y, Kennelly EJ, Chen S, et al. Identification, biological activities and biosynthetic pathway of Dendrobium alkaloids. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:605994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

20. Tang H, Zhao T, Sheng Y, Zheng T, Fu L, Zhang Y. Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo: a review on its ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and industrialization. Evid-Based Compl Alt. 2017:7436259. [Google Scholar]

21. Xu J, Han QB, Li SL, Chen XJ, Wang XN, Zhao ZZ, et al. Chemistry bioactivity and quality control of Dendrobium, a commonly used tonic herb in traditional Chinese medicine. Phytochem Rev. 2013;12:341–67. [Google Scholar]

22. Yuan Y, Zhang B, Tang X, Zhang J, Lin J. Comparative transcriptome analysis of different dendrobium species reveals active ingredients-related genes and pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Guo X, Li Y, Li C, Luo H, Wang L, Qian J, et al. Analysis of the Dendrobium officinale transcriptome reveals putative alkaloid biosynthetic genes and genetic markers. Gene. 2013;527(1):131–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Chen XM, Xiao SY, Guo SX. Comparison of chemical compositions between Dendrobium candidum and Dendrobium nobile. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2006;28(4):524–9 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Chang M, Wang Z, Zhang T, Wang T, Liu R, Wang Y, et al. Characterization of fatty acids, triacylglycerols, phytosterols and tocopherols in peony seed oil from five different major areas in China. Food Res Int. 2020;137(17):109416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li L, Cheng H, Gai J, Yu D. Genome-wide identification and characterization of putative cytochrome P450 genes in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Planta. 2007;226(1):109–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-006-0473-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yan L, Wang X, Liu H, Tian Y, Lian J, Yang R, et al. The genome of Dendrobium officinale illuminates the biology of the important traditional Chinese orchid herb. Mol Plant. 2015;8(6):922–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

28. Zhang GQ, Xu Q, Bian C, Tsai WC, Yeh CM, Liu KW, et al. The Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. genome sequence provides insights into polysaccharide synthase, floral development and adaptive evolution. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

29. Yuan Y, Yu M, Jia Z, Song Xe, Liang Y, Zhang J. Analysis of Dendrobium huoshanense transcriptome unveils putative genes associated with active ingredients synthesis. BMC Genom. 2018;19(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

30. Chen Y, Wang Y, Lyu P, Chen L, Shen C, Sun C. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveal the regulation mechanism underlying MeJA-induced accumulation of alkaloids in Dendrobium officinale. J Plant Res. 2019;132(3):419–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-019-01099-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Shen C, Guo H, Chen H, Shi Y, Meng Y, Lu J, et al. Identification and analysis of genes associated with the synthesis of bioactive constituents in Dendrobium officinale using RNA-Seq. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

32. Song C, Ma J, Li G, Pan H, Zhu Y, Jin Q, et al. Natural composition and biosynthetic pathways of alkaloids in medicinal Dendrobium species. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:133. [Google Scholar]

33. Wang Z, Jiang W, Liu Y, Meng X, Su X, Cao M, et al. Putative genes in alkaloid biosynthesis identified in Dendrobium officinale by correlating the contents of major bioactive metabolites with genes expression between Protocorm-like bodies and leaves. BMC Genom. 2021b;22(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

34. Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

35. Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. NAR. 1997;25(24):4876–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

37. Yuan Y, Zhang J, Liu X, Meng M, Wang J, Lin J. Tissue-specific transcriptome for Dendrobium officinale reveals genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis. Genomic. 2020;112(2):1781–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.10.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Yuan Y, Zuo J, Zhang H, Zu M, Yu M, Liu S. Transcriptome and metabolome profiling unveil the accumulation of flavonoids in Dendrobium officinale. Genomic. 2022;114:110324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2022.110324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatic. 2011;12(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

40. Jin Q, Yao Y, Cai Y, Lin Y. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of a phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene from Dendrobium. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

41. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

42. Dewey RE, Xie J. Molecular genetics of alkaloid biosynthesis in Nicotiana tabacum. Phytochemistry. 2013;94:10–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

43. Pan Q, Mustafa NR, Tang K, Choi YH, Verpoorte R. Monoterpenoid indole alkaloids biosynthesis and its regulation in Catharanthus roseus: a literature review from genes to metabolites. Phytochem Rev. 2016;15(2):221–50. [Google Scholar]

44. Han R, Takahashi H, Nakamura M, Bunsupa S, Yoshimoto N. Transcriptome analysis of nine tissues to discover genes involved in the biosynthesis of active ingredients in Sophora flavescens. Biol Pharm Bull. 2015;38(6):876–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

45. Beaudoin GA, Facchini PJ. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy. Planta. 2014;240(1):19–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

46. Lei Z, Zhou C, Ji X, Wei G, Huang Y, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis and accumulation in Dendrobium catenatum from different locations. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

47. Zhan X, Qi J, Zhou B, Mao B. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal the regulation of pigmentation in the purple variety of Dendrobium officinale. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

48. Zhan X, Qian Y, Mao B. Metabolic profiling of terpene diversity and the response of prenylsynthase-terpene synthase genes during biotic and abiotic stresses in Dendrobium catenatum. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(12):6398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

49. Li Q, Ding G, Li B, Guo SX. Transcriptome analysis of genes involved in dendrobine biosynthesis in Dendrobium nobile Lindl. Infected with mycorrhizal fungus MF23 (Mycena sp.). Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

50. Cessur A, Albayrak İ., Demirci T, Baydar NG. Silver and salicylic acid-chitosan nanoparticles alter indole alkaloid production and gene expression in root and shoot cultures of Isatis tinctoria and Isatis ermenekensis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;202:107977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

51. Liu S, Meng Z, Zhang H, Chu Y, Qiu Y. Identification and characterization of thirteen gene families involved in flavonoid biosynthesis in Ginkgo biloba. Ind Crop Prod. 2022;188:115576. [Google Scholar]

52. Deng Y, Li C, Li H, Lu S. Identification and characterization of flavonoid biosynthetic enzyme genes in Salvia miltiorrhiza (Lamiaceae). Molecules. 2018;23(6):1467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

53. Chan W-S, Abdullah JO, Namasivayam P, Mahmood M. Molecular characterization of a new 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) transcript from Vanda Mimi Palmer. Sci horticul. 2009;121(3):378–82. [Google Scholar]

54. Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic-and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10(2):88–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools