Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Overexpression of Wheat TaELF3-1BL Delays Flowering in Arabidopsis

State Key Laboratory of Crop Biology, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an, 271018, China

* Corresponding Author: Yanrong An. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this paper

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Omics in Challenging Environment)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2023, 92(1), 79-90. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2022.022225

Received 28 February 2022; Accepted 21 April 2022; Issue published 06 September 2022

Abstract

EARLY FLOWERING 3 (ELF3), a light zeitnehmer (time-taker) gene, regulates circadian rhythm and photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis, rice, and barley. The three orthologs of ELF3 (TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL) have been identified in wheat too, and one gene, TaELF3-1DL, has been associated with heading date. However, the basic characteristics of these three genes and the roles of the other two genes, TaELF3-1BL and, TaELF3-1AL, remain unknown. Therefore, the present study obtained the coding sequences of the three orthologs (TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL) of ELF3 from bread wheat and characterized them and investigated the role of TaELF3-1BL in Arabidopsis. Protein sequence comparison revealed similarities among the three TaELF3 genes of wheat; however, they were different from the Arabidopsis ELF3. Real-time quantitative PCR revealed TaELF3 expression in all wheat tissues tested, with the highest expression in young spikes; the three genes showed rhythmic expression patterns also. Furthermore, the overexpression of the TaELF3-1BL gene in Arabidopsis delayed flowering, indicating their importance in flowering. Subsequent overexpression of TaELF3-1BL in the Arabidopsis ELF3 nonfunctional mutant (elf3 mutant) eliminated its early flowering phenotype, and slightly delayed flowering. The wild-type Arabidopsis overexpressing TaELF3-1BL demonstrated reduced expression levels of flowering-related genes, such as CONSTANS (AtCO), FLOWERING LOCUS T (AtFT), and GIGANTEA (AtGI). Thus, the study characterized the three TaELF3 genes and associated TaELF3-1BL with flowering in Arabidopsis, suggesting a role in regulating flowering in wheat too. These findings provide a basis for further research on TaELF3 functions in wheat.Keywords

Bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is an important food crop species. It is grown on more than 220 million hectares worldwide with an annual global production of 750 million tons. Nearly 50 billion dollars (US) worth of wheat are traded worldwide every year. It is the staple food for about 40% of the world population and is widely cultivated for other needs, including animal feed [1]. The timing of flowering is an important agronomic trait of wheat influencing its adaptation to specific cropping environments. A better understanding of the genes controlling flowering time will help breeders develop new cultivars with adaptive traits [2,3].

In wheat, flowering is determined by vernalization (VRN), photoperiod (PPD), and earliness per se (EPS) genes. Numerous quantitative trait loci (QTL) for flowering have been identified, and few of their target genes have been cloned in wheat. Characterization of four VRN genes (VRN1, VRN2, VRN3, and VRN4) controlling vernalization-mediated flowering has advanced our understanding of vernalization regulatory pathways [4–9]. Researchers have identified PPD genes, including Ppd-A1, Ppd-B1, and Ppd-D1, in wheat that contribute to photoperiod sensitivity and strongly influence flowering time [10–14]. Meanwhile, EPS genes influence flowering time, independent of vernalization and photoperiod responses [15,16]. The QTLs controlling EPS were detected on most chromosomes in wheat, but only a few genes were cloned [17–23]. Moreover, the complex regulatory mechanisms of flowering in wheat remain largely unknown.

Wheat is a long-day plant, similar to the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Several genes related to flowering time in wheat have been identified and characterized via cloning based on Arabidopsis homologs [24–27]. This strategy has accelerated studies on the molecular mechanisms of flowering in wheat. Among the various genes, EARLY FLOWERING 3 (ELF3) is a zeitnehmer (time-taker) that regulates circadian clock and photoperiod flowering in Arabidopsis [28–35]. OsELF3-1 and OsELF3-2, the rice homologs of ELF3, are essential for circadian rhythm regulation and photoperiodic flowering [36]. In barley, too, HvELF3, a homolog of ELF3, is responsible for early flowering [37,38]. Meanwhile, Wang et al. [39] identified three homologs of ELF3 (TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL) in wheat and associated TaELF3-1DL with heading date based on a QTL found segregating with this locus. However, no study has characterized the three genes and investigated the roles of TaELF3-1BL and TaELF3-1AL.Therefore, the present study aimed to analyze the characteristics of three TaELF3 genes and the role of the TaELF3-1BL gene. We obtained the ELF3 ortholog sequences from bread wheat, characterized them, and analyzed their expression patterns across tissues and under various day and night cycles. Furthermore, a transgenic approach was used to explore the functions of TaELF3-1BL in WT (wild-type) and elf3 mutant of Arabidopsis. Collectively, the study will enrich our understanding of TaELF3 genes and the role of TaELF3-1BL in photoperiod flowering, providing a basis for further research on TaELF3 functions in wheat.

2.1 Experimental Materials and Growth Conditions

The winter wheat cultivar Yannong15 was used in the present study. The coding sequences of TaELF3 genes were obtained, and the tissue expression patterns were analyzed by growing Yannong15 in a field at the experimental station of Shandong Agricultural University (Taian, Shandong, China, 36.17°N, 117.17°E). For rhythmic expression analysis, the winter wheat cultivar Yannong15 was grown in chambers at 60% humidity under LD (long day; 16 h light at 23°C and 8 h darkness at 16°C), or SD (short day; 10 h light at 23°C and 14 h darkness at 16°C), or SL (standard light; 12 h light at 23°C and 12 h darkness at 16°C). The samples collected from these plants were used to analyze the rhythmic expression of the genes. The study used the WT Arabidopsis (Columbia ecotype) and the Arabidopsis elf3 mutant for genetic transformation. The seeds of the WT and mutant plants were surface-sterilized in 70% ethanol for 1 min and kept at 4°C in the dark for 3 d and under LD conditions at 23°C for one week to germinate. The seedlings coming from seed germination were transplanted to vermiculite and grown under LD conditions. The seeds of the Arabidopsis elf3 mutant were purchased from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC).

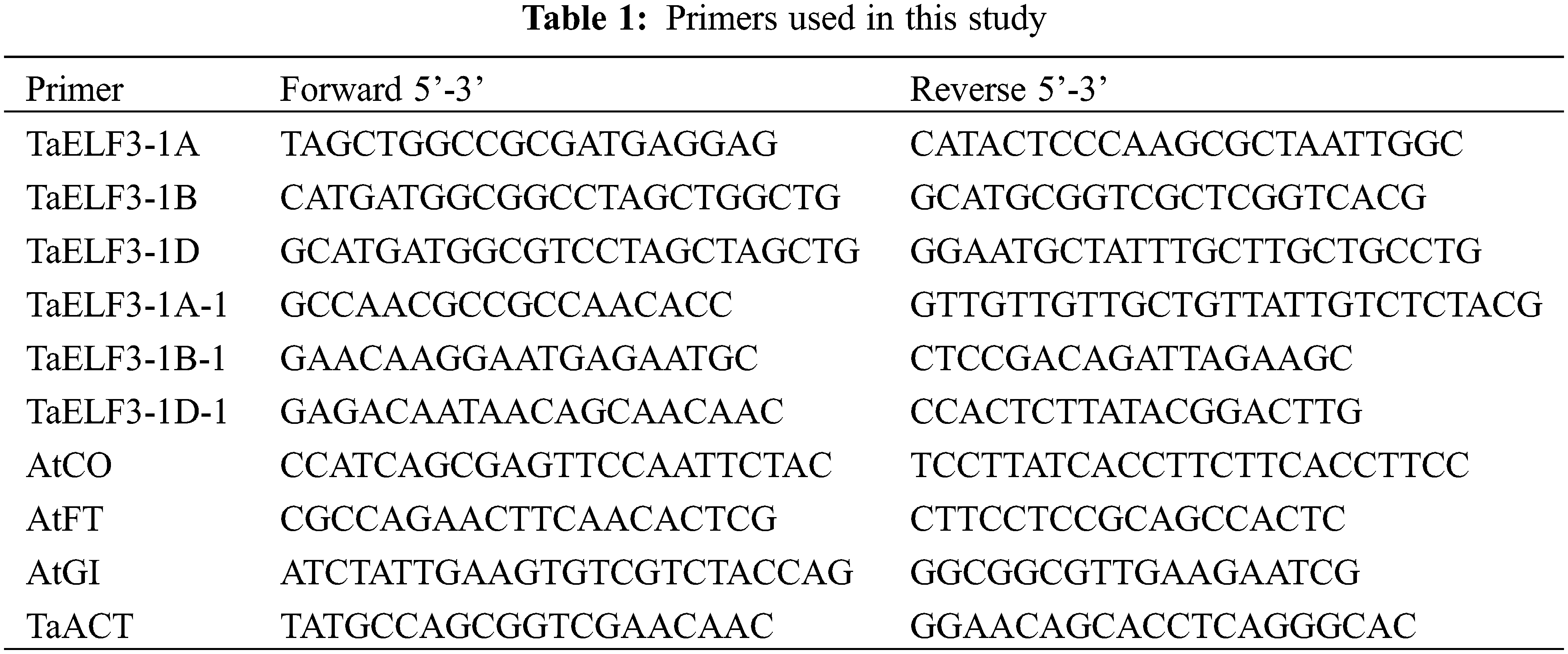

2.2 TaELF3 Gene Amplification and Vector Construction

The Arabidopsis ELF3 protein sequence (AT2G25930) was used to query BLAST against the wheat genome database (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html), and the three wheat sequences homologous (highest similarity) to Arabidopsis ELF3 were extracted. Based on sequence alignment, three gene-specific primers pairs (TaELF3-1A, TaELF3-1B, and TaELF3-1D) were designed by Primer Premier Version 5.0 and adjusted manually (Table 1). The amplicons were sequenced, and the predicted amino acid sequences were aligned and compared using DNAMAN software (version 7.212, Lynnon Corp., Quebec, Canada).

Total RNA was extracted from the young wheat leaves using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and 2 μg of the RNA were used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA with the Superscript II First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Cat. No. 11904-018; Invitrogen). The cDNA was used to amplify TaELF3 genes by PCR (20 μL; 80 ng of template DNA, 2 pmol of each primer, and 10 μl of 2 × Taq PCR Mix; HT-biotech, http://www.ht-biotech.net) performed at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of amplification at 94°C for 30 s, 60°C–66°C (depending on the primers) for 30 s, 72°C for 2 min 30 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR product was separated on 1% agarose gels, purified, cloned into the pEASY-T1 vector (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing; http://www.transgen.com.cn), sequenced at Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China; http://www.sangon.com), and ligated into the expression vector pBI121 to generate the 35S::TaELF3-1BL expression construct.

2.3 Tissue and Rhythmic Expression Patterns of TaELF3 Genes

Total RNA was extracted from the young root (Rt), stem/shoot (St), flag leaf (Fl), leaf sheath (Ls), internode (In), and young spikelet (Sl) of field-grown wheat plants at the booting stage using the Trizol reagent. Approximately 2 μg of the total RNA were used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA, and the expression level of the three TaELF3 genes was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using gene-specific primers (TaELF3-1A-1, TaELF3-1B-1, and TaELF3-1D-1, Table 1). The relative expression levels of the genes were quantified following the ΔΔCt method [40], using Actin (TaACT) as the reference gene and three biological replicates per sample.

For the rhythmic expression analysis, the leaves of 14-day-old wheat seedlings grown under various light-dark conditions (LD, 16 h light/8 h dark; SD, 10 h light/14 h dark; SL, 12 h light/12 h dark) were used. Leaves of the seedlings grown under LD or SD conditions were collected at zeitgeber time (time giver or time cue; environmental factor that acts as a circadian cue) 0 (ZT0, light on 6:00 AM) and every 4 h over a 24 h period. Meanwhile, seedlings grown under standard light (SL, 12 h light/12 h dark) for 14 d were divided into two groups and exposed to continuous light or continuous darkness in the morning (ZT0). Leaves were collected starting from the 15th day at 6:00 AM (ZT24) and every 4 h over a 24 h period, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Finally, the expression levels of TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL genes in these samples were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) following the described method.

2.4 Heterologous Transformation of TaELF3-1BL Gene in Arabidopsis

The 35S::TaELF3-1BL expression construct was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101 strain) and transformed into Arabidopsis thaliana by the floc staining method. The transformants selected on an agarose plate containing Kanamycin (50 mg L−1) were planted in vermiculite and watered regularly with nutrient solution. DNA was extracted from the leaves of these seedlings following the CTAB method [41], and the transgene integration was confirmed by PCR.

2.5 Analysis of the Phenotype and Flowering-Related Gene Expression in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants

Thirty transgenic plants expressing 35S::TaELF3-1BL and 30 WT plants were selected as the population for phenotypic and gene expression analyses. The flowering time and the number of rosette leaves at flowering were measured after growth under LD conditions.

Total RNA was extracted from the Arabidopsis leaves at bolting and flowering using Trizol reagent and reverse transcribed to obtain the first-strand cDNA. Then, qRT-PCR was carried out using this cDNA to analyze the expression of flowering-related genes, including CONSTANS (AtCO), FLOWERING LOCUS T (AtFT), and GIGANTEA (AtGI), under LD conditions. The primers used are shown in Table 1.

3.1 Analysis of the Three Wheat TaELF3 Genes

BLAST analysis against the Chinese genome v1.1 database using Arabidopsis ELF3 protein sequence on the EnsemblPlants website (http://plants.ensembl.org/Triticum_aestivum/Tools/Blast) identified three annotated genes, TraesCS1A02G443200, TraesCS1B02G477400, and TraesCS1D02G451200, with the highest homology, on chromosomes 1AL, 1BL, and 1DL, respectively. Wang et al. [39] had previously cloned these three genes and named them TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL. The present study initially obtained the coding sequences (CDS) of these three genes. Sequence analysis revealed that TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL had an intact open reading frame (ORF) of 2304, 2304, and 2295 bp, encoding polypeptides with 768, 768, and 765 amino acid residues, respectively. These three TaELF3 genes had similar amino acid sequences; however, the sequences were highly different from the Arabidopsis ELF3 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Amino acid sequence alignment of ELF3 from wheat and Arabidopsis thaliana

The deduced amino acid sequences of wheat ELF3 (TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL) were aligned with Arabidopsis ELF3 using the DNAMAN software. Pink boxes indicate conserved regions in the amino acid sequences of the three wheat genes, and black regions indicate conserved regions in amino acid sequences of the four genes.

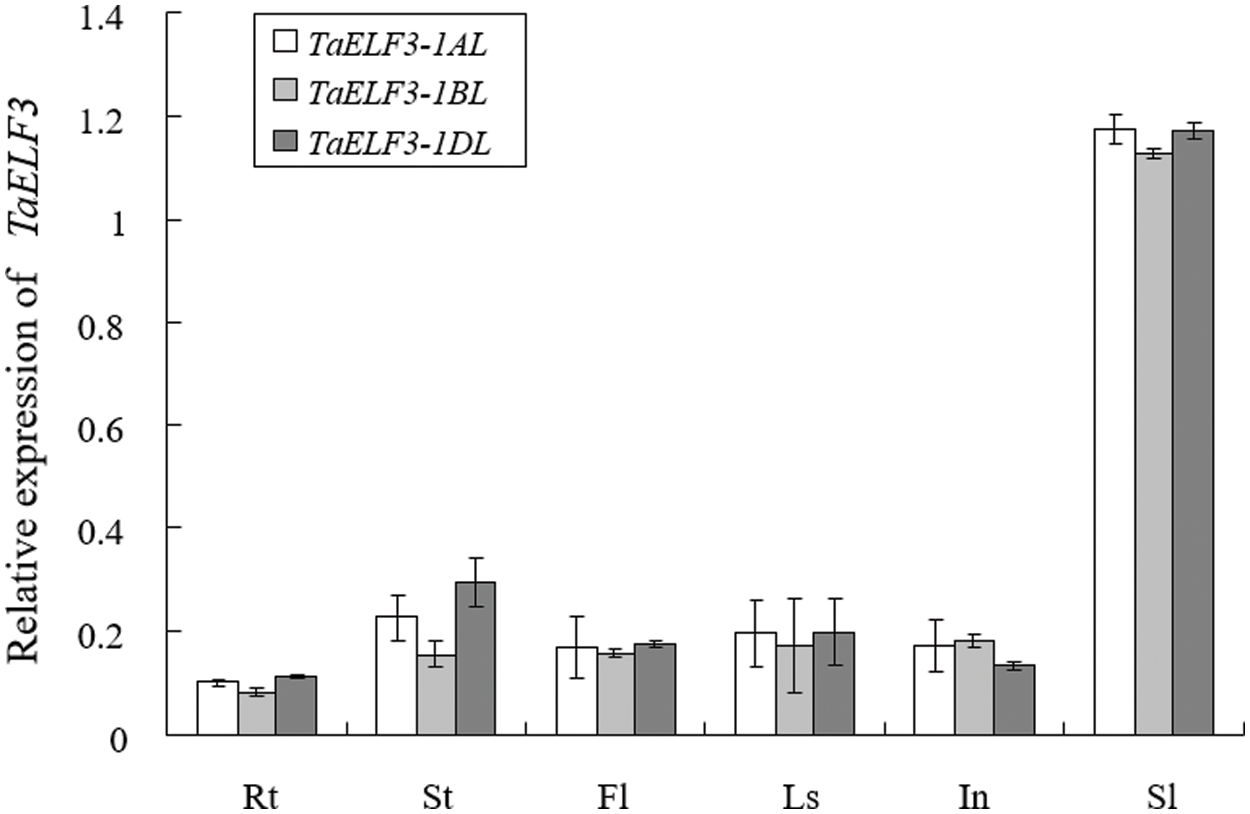

3.2 Tissue Expression Pattern of TaELF3 Genes

We analyzed the expression patterns of the three TaELF3 genes in various wheat tissues at the booting stage by qRT-PCR. The analysis revealed expression of these three genes in all tissues, including young root (Rt), stem/shoot (St), flag leaf (Fl), leaf sheath (Ls), internodes (In), and spikelet (Sl). In each tissue, the expression patterns of these three genes were similar; however, the expression levels of each gene were different across the tissues (Fig. 2). The highest expression of TaELF3 genes was detected in the young spikes.

Figure 2: Expression pattern of the three TaELF3 genes in various wheat tissues. The expression patterns of TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL in the young root (Rt), stem/shoot (St), flag leaf (Fl), leaf sheath (Ls), internode (In), and young spikelet (Sl) of wheat plants at the booting stage were determined by qRT-PCR. Data represented are mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3)

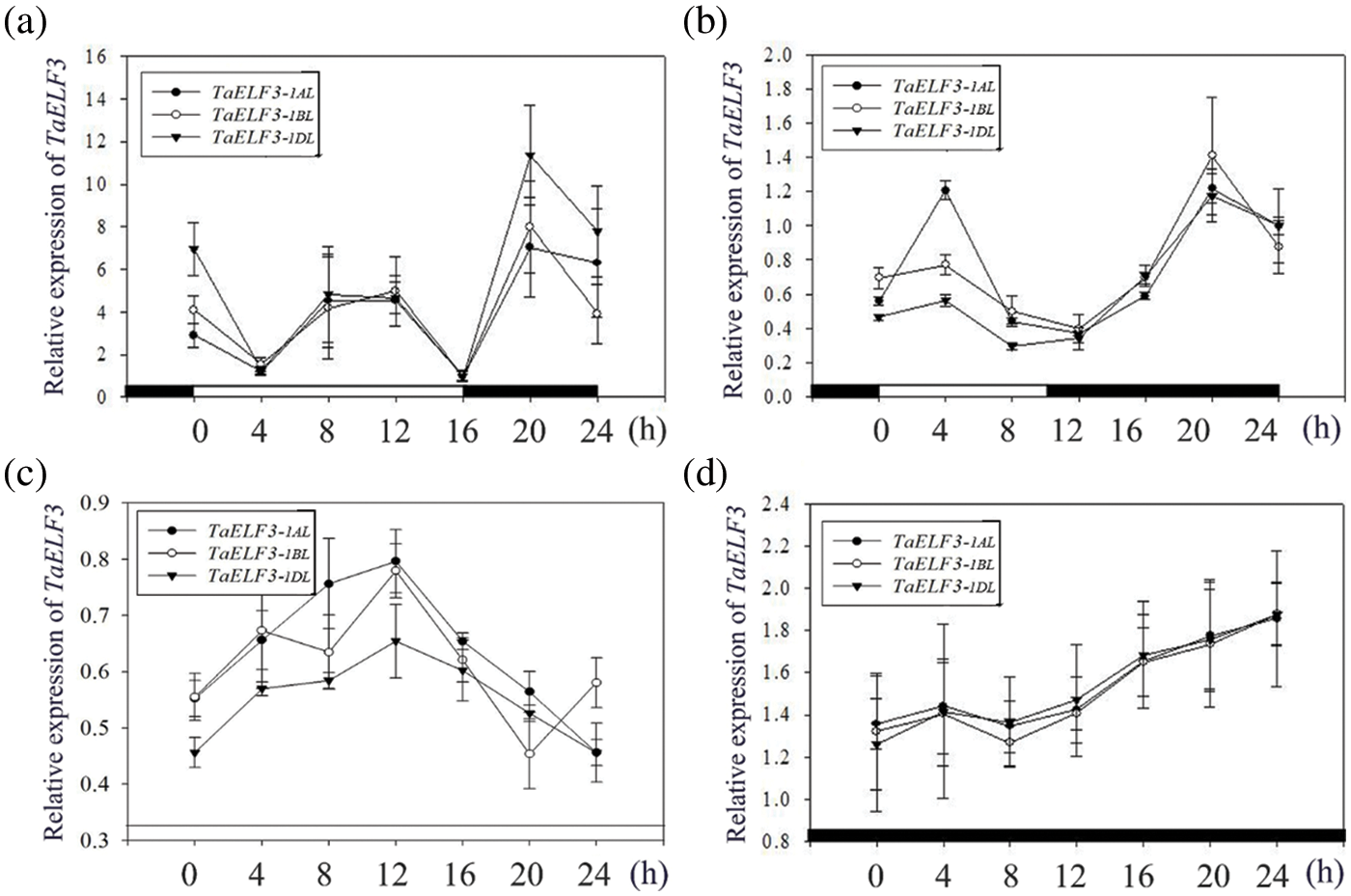

3.3 Rhythmic Expression Analysis of TaELF3 Genes

Furthermore, the transcript levels of TaELF3 genes in the leaves of wheat seedlings grown under four conditions, including LD, SD, continuous light (LL), and continuous darkness (DD), were examined every 4 h for 24 h to explore the role of the circadian clock in regulating the expression of the genes under all four conditions. The analysis revealed similar rhythmic expression patterns for TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL genes. Under LD conditions, the expression levels of the three TaELF3 genes were low at the beginning and gradually progressed as a wave at ZT8 and peaked at ZT20 (Fig. 3a). Meanwhile, under SD conditions, the expression levels of the three TaELF3 genes peaked after the light exposure at ZT4 and after darkness exposure at ZT20 (Fig. 3b). However, the rhythmic expression of the three TaELF3 genes was disrupted under LL (continuous light) and DD (continuous darkness) conditions (Figs. 3c and 3d).

Figure 3: Rhythmic expression analysis of the three TaELF3 genes in wheat under various light conditions. The expression patterns of TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL genes in wheat seedlings grown under (a) long-day conditions; (b) short-day conditions; (c) continuous light; and (d) continuous darkness were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data represented are the mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3)

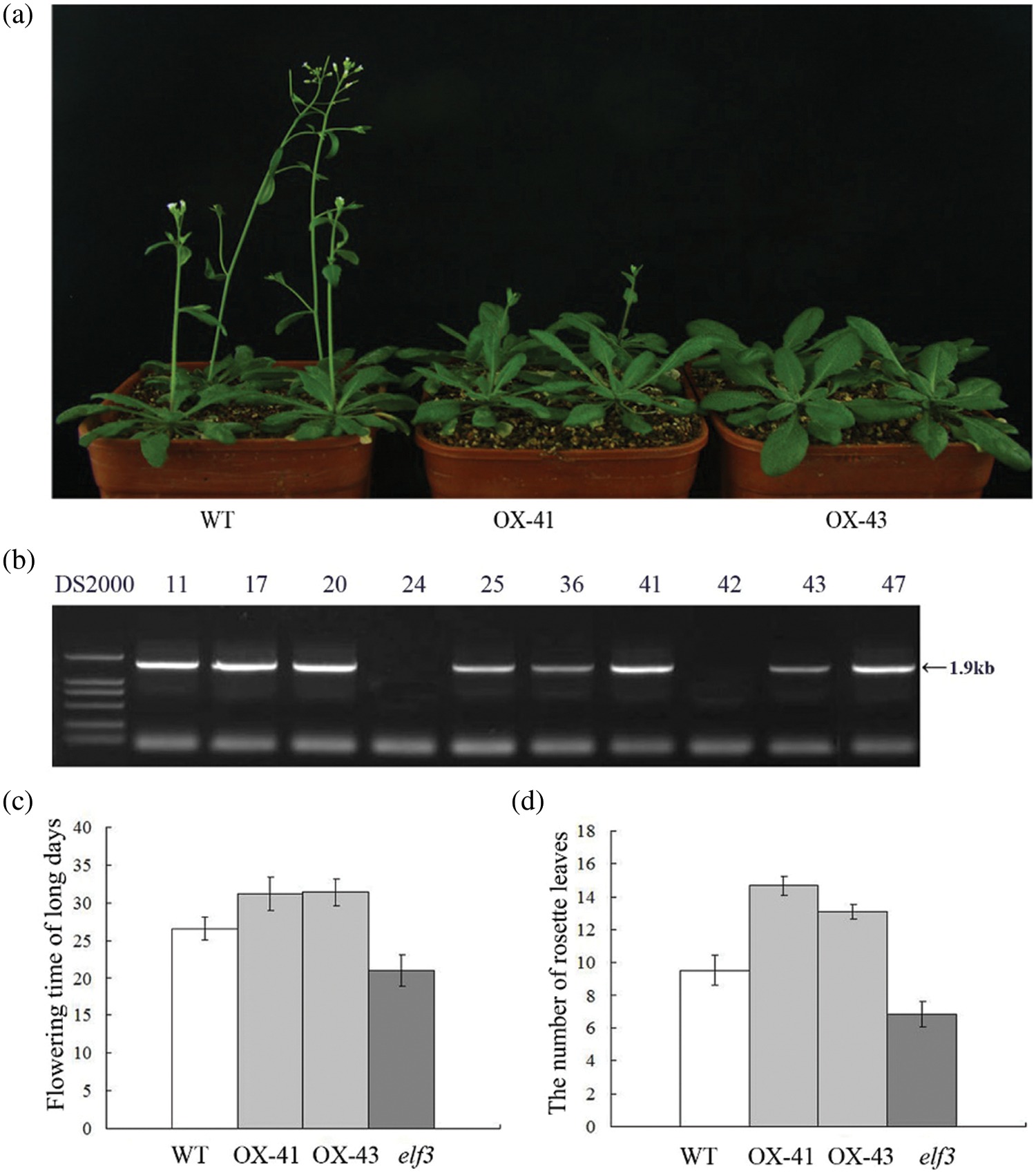

3.4 Overexpression of Wheat TaELF3-1BL Delays Flowering in Arabidopsis

To further investigate the role of TaELF3 genes, one of the three genes, TaELF3-1BL, was overexpressed in Arabidopsis. PCR analysis of the transgenic lines confirmed the integration of the transgene TaELF3-1BL into the Arabidopsis genome (Fig. 4b). The overexpression of TaELF3-1BL in Arabidopsis delayed the flowering time under LD conditions (Fig. 4a). The WT plants flowered at 27 days after transplanting, while the transgenic plants flowered at about 32 days after transplanting (Fig. 4c). The transgenic Arabidopsis lines had an average of five rosette leaves more than the WT plants (Fig. 4d), indicating delayed flowering with TaELF3-1BL overexpression.

Figure 4: TaELF3-1BL overexpression delays flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana. (a) Flowering in wild-type (WT) and TaELF3-1BL overexpressing Arabidopsis plants; OX-41 and OX-43 are the two transgenic lines; (b) PCR confirmation of transgenic plants (11, 17, 20, 24, 25, 36, 41, 42, 43, and 47 represent the putative transgenic plants analyzed, and 11, 17, 20, 25, 36, 41, 43, and 47 represent the positive plants). The expected amplicon is 1.9 kb long; DS2000 indicates the marker. (c–d) Flowering time (number of days from transplanting to flowering) (c) and the number of rosette leaves (d) in the transgenic plants and the wild-type plants. Data represented in (c) and (d) are mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 30)

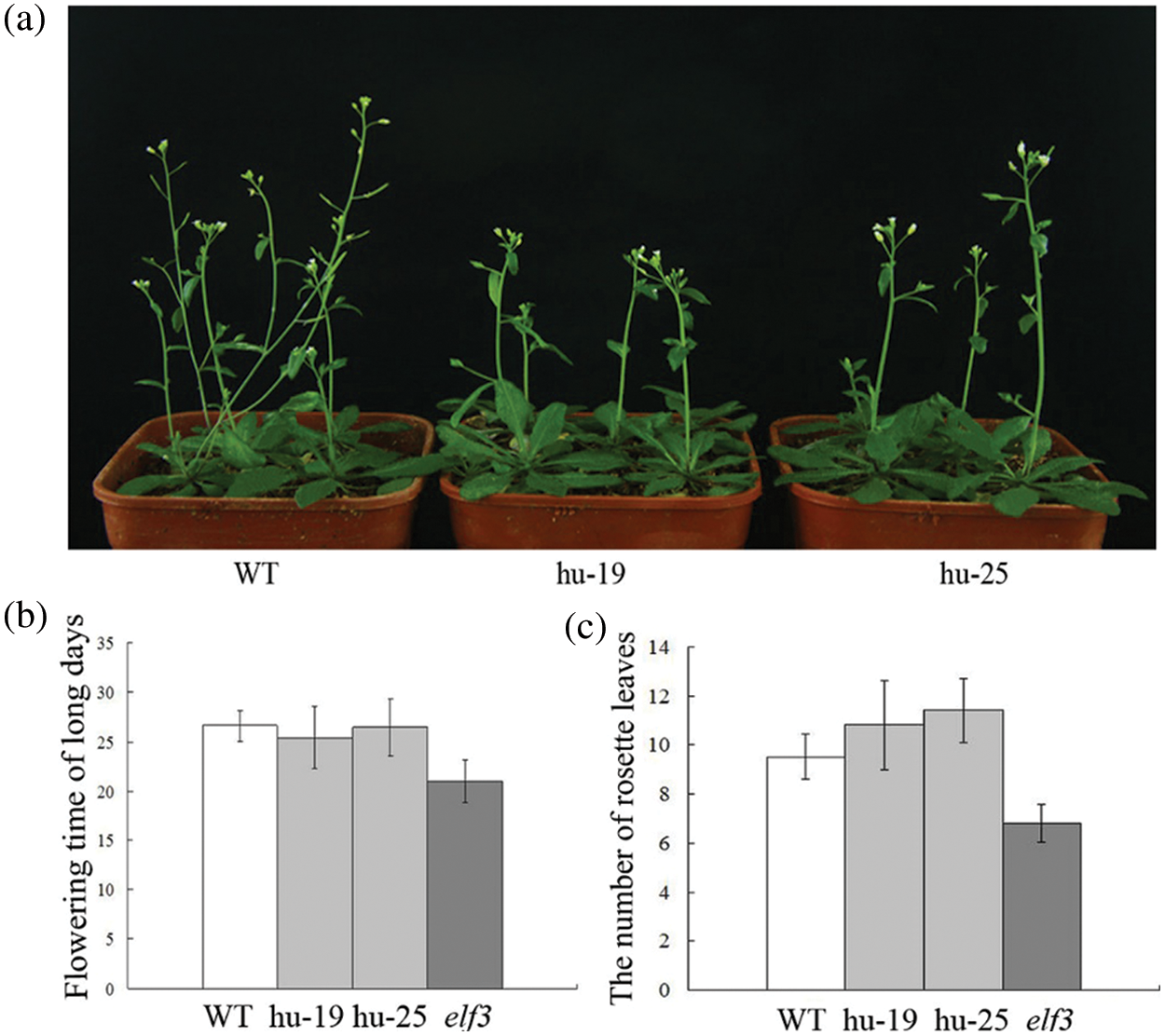

To further confirm the function of TaELF3-1BL, the 35S::TaELF3-1BL construct was expressed in the Arabidopsis elf3 mutant. The overexpression of TaELF3-1BL in the Arabidopsis elf3 mutant slightly delayed flowering (Fig. 5a). The WT took 26 days to flower, while the elf3 mutant took 22 days. Overexpression of TaELF3-1BL in the mutant, delayed the flowering to about 26 days. (Fig. 5b). Meanwhile, both the transgenic lines and the WT had more rosette leaves than the elf3 mutant. The number of rosette leaves of the overexpressing plants was slightly more than on the WT, indicating retention of the WT flowering phenotype (Fig. 5c). These observations indicate that the overexpression of TaELF3-1BL in the Arabidopsis elf3 mutant slightly delayed flowering compared with the WT, it is obtained from the number of rosette leaves.

Figure 5: Overexpressing TaELF3-1BL delays flowering slightly in the Arabidopsis elf3 mutant plants. (a) Phenotype; (b) flowering time; and (c) rosette leaf number of wild-type (WT), elf3 mutant overexpressing TaELF3-1BL (hu-19 and hu-25), and elf3 mutant plants. Data represented in (b) and (c) are mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 30)

3.5 Expression Pattern of Flowering-related Genes in TaELF3-1BL Overexpressing Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants

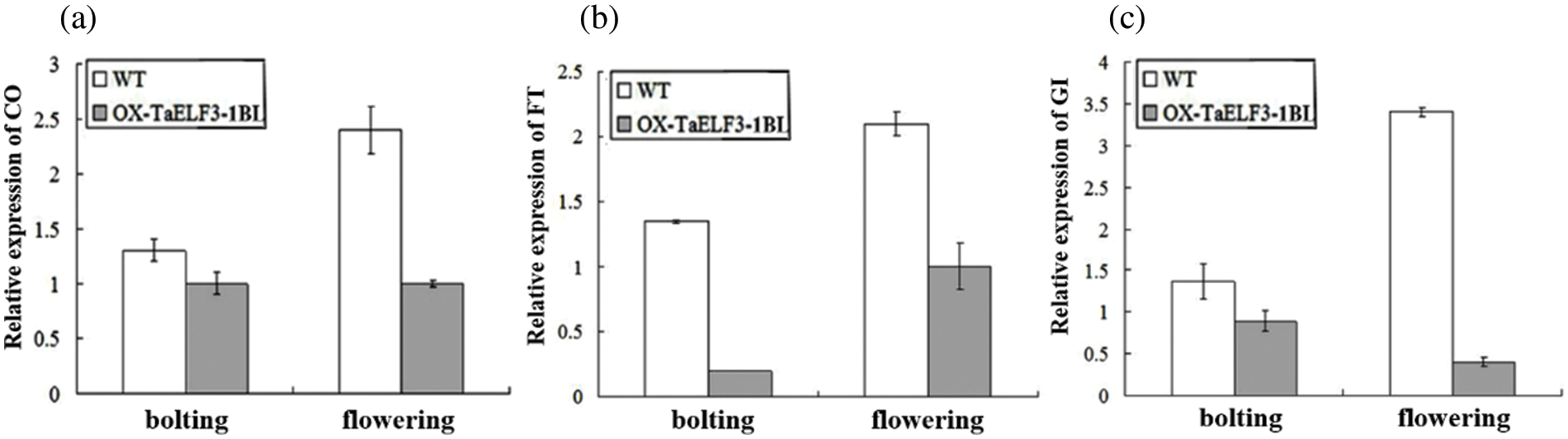

Further, the effects of TaELF3-1BL overexpression on the flowering-related genes were analyzed via qRT-PCR using RNA isolated from the WT and 35S::TaELF3-1BL overexpressing Arabidopsis plants. The results indicated that AtCO, AtFT, and AtGI were repressed in the transgenic plant (Fig. 6a). These observations suggest that the overexpression of TaELF3-1BL altered the expression of flowering-related genes, leading to delayed flowering in Arabidopsis.

Figure 6: Overexpression of TaELF3-1BL influences the expression of flowering-related genes at bolting and flowering in Arabidopsis. The expression levels of AtCO, AtFT, and AtGI genes in wild-type (WT) and TaELF3-1BL overexpressing plants were determined by qRT-PCR. Data represented in (a), (b), and (c) are mean ± standard deviation (SD; n = 3)

The ELF3 gene shows a circadian rhythmic expression pattern and regulates photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis. Studies in bread wheat have identified three TaELF3 genes and associated the TaELF3-1DL gene with heading date [39]. However, the characteristics of the three TaELF3 genes and the roles of TaELF3-1AL and TaELF3-1BL have not been fully explored. Therefore, the present study pulled out the three TaELF3 genes (TaELF3-1AL, TaELF3-1BL, and TaELF3-1DL) from the winter wheat cultivar Yannong 15, analyzed their amino acid sequences, and found similarities among the three genes; however, these amino acid sequences were different from the Arabidopsis ELF3. Further analysis revealed that three genes were expressed in all wheat tissues tested, with the highest expression in young spikes, suggesting a significant role in developing young panicles and a constitutive expression of the three TaELF3 genes. In addition, the three TaELF3 genes showed similar rhythmic expression patterns under LD and SD conditions, which were disrupted under continuous light and continuous darkness conditions. Earlier, Hicks et al. demonstrated a rhythmic expression for ELF3 in Arabidopsis after exposure to LD conditions, with a low expression at dawn and a peak expression at dusk [42]. Similarly, our experiments showed the rhythmic expression of these three TaELF3 genes, similar to Arabidopsis ELF3 under LD conditions, which suggests a probable rhythmic function of TaELF3.

Under LD conditions, loss-of-function mutations in the Arabidopsis (elf3 mutant) gene caused early flowering, while overexpression of ELF3 caused late flowering, with reduced expression of the flowering-related genes AtCO, AtFT, and AtGI [31,37,38,43–45]. Similarly, the present study found that the overexpression of TaELF3-1BL in Arabidopsis delayed flowering. Overexpression of the TaELF3-1BL gene in the Arabidopsis elf3 mutant also slightly delayed flowering, confirming the role of the TaELF3-1BL gene in Arabidopsis flowering. These observations suggest that the TaELF3-1BL gene may also regulate wheat flowering, which needs to be further investigated. Further analysis of the expression of flowering-related genes at bolting and flowering in the WT Arabidopsis overexpressing the TaELF3-1BL gene revealed reduced expression of AtCO, AtFT, and AtGI genes. Thus, our study suggests that the overexpression of TaELF3-1BL delayed flowering in Arabidopsis by reducing the expression of the flowering-related genes. The findings on the characteristics of the three genes and the effect of TaELF3-1BL in Arabidopsis flowering provide a basis for further research on the three TaELF3 genes.

Authors’ Contributions: YA and SL designed the experiments. JS, HZ and MZ performed the experiments. JS and HZ analyzed the data. JS and YA wrote the manuscript.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Not applicable.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

Acknowledgment: Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Zhao, G. C., Chang, X. H., Wang, D. M., Tao, Z. Q., Wang, Y. J. et al. (2018). General situation and development of wheat production. Crops, 34(4), 1–7. DOI 10.16035/j.issn.10017283.2018.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Beniston, M., Stephenson, D. B., Christensen, O. B., Ferro, C. A., Frei, C. et al. (2007). Future extreme events in European climate: An exploration of regional climate model projections. Climatic Change, 81(1), 71–95. DOI 10.1007/s10584-006-9226-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Jung, C., Müller, A. E. (2009). Flowering time control and applications in plant breeding. Trends in Plant Science, 14(10), 563–573. DOI 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yan, L., Loukoianov, A., Tranquilli, G., Helguera, M., Fahima, T. et al. (2003). Positional cloning of the wheat vernalization gene VRN1. PNAS, 100(10), 6263–6268. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0937399100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yan, L. L., Loukoianov, A., Blechl, A., Tranquilli, G., Ramakrishna, W. et al. (2004). The wheat VRN2 gene is a flowering repressor downregulated by vernalization. Science, 303(5664), 1640–1644. DOI 10.1126/science.1094305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yan, L., Fu, D., Li, C., Blechl, A., Tranquilli, G. et al. (2006). The wheat and barley vernalization gene VRN3 is an orthologue of FT. PNAS, 103(51), 19581–19586. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0607142103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li, C., Dubcovsky, J. (2008). Wheat FT protein regulates VRN1 transcription through interactions with FDL2. Plant Journal, 55(4), 543–554. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03526.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yoshida, T., Nishida, H., Zhu, J., Nitcher, R., Distelfeld, A. (2010). Vrn-D4 is a vernalization gene located on the centromeric region of chromosome 5D in hexaploid wheat. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 120(3), 543–552. DOI 10.1007/s00122-009-1174-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kippes, N., Debernardi, J. M., Vasquez-Gross, H. A., Akpinar, B. A., Budak, H. et al. (2015). Identification of the VERNALIZATION 4 gene reveals the origin of spring growth habit in ancient wheats from South Asia. PNAS, 112(39), E5401–E5410. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1514883112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Beales, J., Turner, A., Griffiths, S., Snape, J. W., Laurie, D. A. (2007). A pseudo-response regulator is misexpressed in the photoperiod insensitive Ppd-D1a mutant of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 115(5), 721–733. DOI 10.1007/s00122-007-0603-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Distelfeld, A., Li, C., Dubcovsky, J. (2009). Regulation of flowering in temperate cereals. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 12(2), 178–184. DOI 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dhillon, T., Pearce, S. P., Stockinger, E. J., Distelfeld, A., Li, C. X. (2010). Regulation of freezing tolerance and flowering in temperate cereals: The VRN-1 connection. Plant Physiology, 153(4), 1846–1858. DOI 10.1104/pp.110.159079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nishida, H., Yoshida, T., Kawakami, K., Fujita, M., Long, B. (2013). Structural variation in the 5′ upstream region of photoperiod-insensitive alleles Ppd-A1a and Ppd-B1a identified in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.and their effect on heading time. Molecular Breeding, 31(1), 27–37. DOI 10.1007/s11032-012-9765-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sun, H., Guo, Z. A., Gao, L. F., Zhao, G. Y., Zhang, W. P. et al. (2014). DNA methylation pattern of Photoperiod-B1 is associated with photoperiod insensitivity in wheat (Triticum aestivum). New Phytologist, 204(3), 682–692. DOI 10.1111/nph.12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Worland, A. J. (1996). The influence of flowering time genes on environmental adaptability in European wheats. Euphytica, 89(1), 49–57. DOI 10.1007/BF00015718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Slafer, G. A. (1996). Differences in phasic development rate amongst wheat cultivars independent of responses to photoperiod and vernalization. A viewpoint of the intrinsic earliness hypothesis. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 126(4), 403–419. DOI 10.1017/S0021859600075493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Reif, J. C., Maurer, H. P., Korzun, V., Ebmeyer, E., Miedaner, T. et al. (2011). Mapping QTLs with main and epistatic effects underlying grain yield and heading time in soft winter wheat. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 123(2), 283–292. DOI 10.1007/s00122-011-1583-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rousset, M., Bonnin, I., Remoue, C., Falque, M., Rhone, B. et al. (2011). Deciphering the genetics of flowering time by an association study on candidate genes in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 123(6), 907–926. DOI 10.1007/s00122-011-1636-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bennett, D., Izanloo, A., Edwards, J., Kuchel, H., Chalmers, K. et al. (2012). Identification of novel quantitative trait loci for days to ear emergence and flag leaf glaucousness in a bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) population adapted to Southern Australian conditions. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 124(4), 697–711. DOI 10.1007/s00122-011-1740-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Le Gouis, J., Bordes, J., Ravel, C., Heumez, E., Faure, S. et al. (2012). Genome-wide association analysis to identify chromosomal regions determining components of earliness in wheat. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 124(3), 597–611. DOI 10.1007/s00122-011-1732-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gawroński, P., Ariyadasa, R., Himmelbach, A., Poursarebani, N., Kilian, B. et al. (2014). A distorted circadian clock causes early flowering and temperature-dependent variation in spike development in the Eps-3Am mutant of einkorn wheat. Genetics, 196(4), 1253–1261. DOI 10.1534/genetics.113.158444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zikhali, M., Wingen, L. U., Griffiths, S. (2016). Delimitation of the Earliness per se D1 (Eps-D1) flowering gene to a subtelomeric chromosomal deletion in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum). Journal of Experimental Botany, 67(1), 287–299. DOI 10.1093/jxb/erv458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Fan, M., Miao, F., Jia, H. Y., Li, G. Q., Powers, C. et al. (2021). O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase is involved in fine regulation of flowering time in winter wheat. Nature Communications, 12(1), 2303. DOI 10.1038/s41467-021-22564-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhao, X. Y., Hong, P., Wu, J. Y., Chen, X. B., Ye, X. G. et al. (2016). The tae-miR408-mediated control of TaTOC1 genes transcription is required for the regulation of heading time in wheat. Plant Physiology, 170(3), 1578–1594. DOI 10.1104/pp.15.01216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu, H., Li, T., Wang, Y. M., Zheng, J., Li, H. F. et al. (2019). TaZIM-A1 negatively regulates flowering time in common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 61(3), 359–376. DOI 10.1111/jipb.12720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang, L., Zhang, H., Qiao, L. Y., Miao, L. F., Yan, D. et al. (2021). Wheat MADS-box gene TaSEP3-D1 negatively regulates heading date. The Crop Journal, 9(5), 1115–1123. DOI 10.1016/j.cj.2020.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xie, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, K., Luo, X. M., Xu, D. A. et al. (2021). TaVrt2, an SVP-like gene, cooperates with TaVrn1 to regulate vernalization-induced flowering in wheat. New Phytologist, 231(2834–848. DOI 10.1111/nph.16339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hicks, K. A., Millar, A. J., Carre, I. A., Somers, D. E., Straume, M. et al. (1996). Conditional circadian dysfunction of the Arabidopsis early-flowering 3 mutant. Science, 274(5288), 790–792. DOI 10.1126/science.274.5288.790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. McWatters, H. G., Bastow, R. M., Hall, A., Millar, A. J. (2000). The ELF3 zeitnehmer regulates light signaling to the circadian clock. Nature, 408(6813), 716–720. DOI 10.1038/35047079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Covington, M. F., Panda, S., Liu, X. L., Strayer, C. A., Wagner, D. R. et al. (2001). ELF3 modulates resetting of the circadian clock in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 13(6), 1305–1315. DOI 10.1105/TPC.000561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kim, W. Y., Hicks, K. A., Somers, D. E. (2005). Independent roles for EARLY FLOWERING 3 and ZEITLUPE in the control of circadian timing, hypocotyl length, and flowering time. Plant Physiology, 139(3), 1557–1569. DOI 10.1104/pp.105.067173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yoshida, R., Fekih, R., Fujiwara, S., Oda, A., Miyata, K. et al. (2009). Possible role of EARLY FLOWERING 3 (ELF3) in clock-dependent floral regulation by SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP) in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytologist, 182(4), 838–850. DOI 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02809.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Thines, B., Harmon, F. G. (2010). Ambient temperature response establishes ELF3 as a required component of the core Arabidopsis circadian clock. PNAS, 107(7), 3257–3262. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0911006107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Boden, S. A., Weiss, D., Ross, J. J., Davies, N. W., Trevaskis, B. et al. (2014). EARLY FLOWERING3 regulates flowering in spring barley by mediating gibberellin production and FLOWERING LOCUS T expression. Plant Cell, 26(4), 1557–1569. DOI 10.1105/tpc.114.123794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhu, C. M., Peng, Q., Fu, D. B., Zhuang, D. X., Yu, Y. M. et al. (2018). The E3 ubiquitin ligase HAF1 modulates circadian accumulation of EARLY FLOWERING 3 to control heading date in rice under long-day conditions. Plant Cell, 30(10), 2352–2367. DOI 10.1105/tpc.18.00653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhao, J. M., Huang, X., Ouyang, X. H., Chen, W. L., Du, A. P. et al. (2012). OsELF3-1, an ortholog of Arabidopsis EARLY FLOWERING 3, regulates rice circadian rhythm and photoperiodic flowering. PLoS One, 7(8), e43705. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0043705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Faure, S., Turner, A. S., Gruszka, D., Christodoulou, V., Davis, S. J. et al. (2012). Mutation at the circadian clock gene EARLY MATURITY 8 adapts domesticated barley (Hordeum vulgare) to short growing seasons. PNAS, 109(21), 8328–8333. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1120496109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zakhrabekova, S., Gough, S. P., Braumann, I., Muller, A. H., Lundqvist, J. et al. (2012). Induced mutations in circadian clock regulator Mat-a facilitated short-season adaptation and range extension in cultivated barley. PNAS, 109(11), 4326–4331. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1113009109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang, J. P., Wen, W., Hanif, M., Xia, X. C., Wang, H. G. et al. (2016). TaELF3-1DL, a homolog of ELF3, is associated with heading date in bread wheat. Molecular Breeding, 36(12), 161. DOI 10.1007/s11032-016-0585-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Livak, K. J., Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods, 25(4), 402–408. DOI 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Saghai-Maroof, M. A., Soliman, K. M., Jorgensen, R. A., Allard, R. W. (1984). Ribosomal DNA spacer-length polymorphisms in barley: Mendelian inheritance, chromosomal location, and population dynamics. PNAS, 81(24), 8014–8018. DOI 10.1073/pnas.81.24.8014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hicks, K. A., Albertson, T. M., Wagner, D. R. (2001). EARLY FLOWERING 3 encodes a novel protein that regulates circadian clock function and flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 13(6), 1281–1292. DOI 10.1105/tpc.13.6.1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kardailsky, I., Shukla, V. K., Ahn, J. H., Dagenais, N., Christensen, S. K. et al. (1999). Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science, 286(5446), 1962–1965. DOI 10.1126/science.286.5446.1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Samach, A., Onouchi, H., Gold, S. E., Ditta, G. S., Schwarz-Sommer, Z. et al. (2000). Distinct roles of CONSTANS target genes in reproductive development of Arabidopsis. Science, 288(5471), 1613–1616. DOI 10.1126/science.288.5471.1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Weller, J. L., Liew, L. C., Hecht, V. F., Rajandran, V., Laurie, R. E. et al. (2012). A conserved molecular basis for photoperiod adaptation in two temperate legumes. PNAS, 109(51), 21158–21163. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1207943110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools