| Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany |  |

DOI: 10.32604/phyton.2022.018708

ARTICLE

Nitric Oxide Alleviates Photochemical Damage Induced by Cadmium Stress in Pea Seedlings

1Department of Life Sciences, Central University of Jharkhand, Ranchi, 835205, India

2Department of Biotechnology, Ch. Bansilal University, Bhiwani, Haryana, 127021, India

3Horticulture Research Institute (HRI), Agricultural Research Center (ARC), Giza, 12619, Egypt

4School of Environment and Sustainable Development, Central University of Gujarat, Gandhinagar, 382030, India

*Corresponding Author: Ekhlaque A. Khan. Email: ekhlaquebiotech@gmail.com

Received: 12 August 2021; Accepted: 18 October 2021

Abstract: Cadmium (Cd), a life threatening hazardous heavy metal is abundant in nature. Cd amounts are greater in leaves than other plant parts, and it shows considerable effects on photosynthesis. Nitric oxide (NO), a free radical present in living organisms, is now known as an important signaling molecule playing various physiological processes in plants. In this study, the possible ameliorative effect of NO on photosynthesis was examined on pea seedlings grown under Cd stress. Results showed that chlorophyll, net photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, photochemical efficiency of Photosystem II and Photosystem I decreased, and Fo and non-photochemical parameters for PSII and PSI significantly increased due to Cd stress. This suggests that Cd affects the photochemistry efficiency at both the PSII and PSI levels. Nitric oxide supplementation through SNP ameliorated Cd stress by enhancing all the above mentioned parameters but causing a reduction in the Fo, and non-photochemical parameters of PSII and PSI in pea plants. These data indicate that the exogenous application of NO was useful in mitigating Cd-induced damage to photosynthesis in pea seedling.

Keywords: Chlorophyll; fluorescence; oxidative stress; Photosystem I; Photosystem II

Heavy metals including Cd occur naturally in soils in trace amounts. Anthropogenic activities have led to Cd contamination of agricultural lands [1]. Cd is taken up from soil and transported to all parts of plant, as a result become potential hazard for both plant and animals [2]. Cd causes (1) inhibition of many physiological processes in plants like nitrogen assimilation, mineral nutrition, photosynthesis, respiration, transpiration, and carbohydrate metabolism (2) increases in chlorosis, wilting, necrotic lesions, and oxidative stress, and induction of senescence, all of which reduce biomass production [3,4]. Furthermore, Cd stress has also been associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, including superoxide ions (O2−•), hydroxyl radicals (HO•) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [5,6].

Photosynthesis, one of the most important physiological processes in plants, affects the entire metabolism of plants. Cd (1) disrupts thylakoid and chloroplast of the photosynthetic apparatus [1,7,8], (2) decreases Chl and carotenoid pigments [9], (3) inhibits the enzymes involved in Chlorophyll synthesis [10] in addition to RUBISCO [11,12], and (4) affects photoreduction and association of protochlorophyllide in etioplast inner membrane preparations and dark-grown leaves of wheat. Chlorophyll biosynthesis is a physiological phenomenon which is connected to photosynthetic efficiency of plants. The δ-amino levulinic acid, an important intermediate of the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway, can be synthesized from 5-carbon compounds, like glutamate [12]. Further, the enzyme δ-amino levulinic acid dehydratase, of the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway, has been shown to be hindered by Cd in radish leaves. Cd2+ is also reported to replace the Mg2+ central atom of chlorophyll in water plants [13,14].

PSII plays an imperative role in the response to environmental worries and stresses in photosynthesis in higher plants [15]. It was reported that Cd targets PSII instead of PSI [16,17]. The NADP oxidoreductase, ATP-synthase and oxygen-evolving complex of the photosynthetic electron transport chain are considered sensitive to Cd [18]. Oxidizing or reducing sites of PSII are probably common sites for heavy metal action in plants [13]. Cd2+ replaces Mn2+ from the water-oxidizing system of PSII leading to PSII reaction inhibition [7]. Only few studies have been done to study the effects of Cd on PSI electron transport in vivo. Most of the effects of Cd on the photosynthetic electron transport have been shown in vitro. PAM fluorometry and especially P700 absorbance–two noninvasive, net photosynthetically informative measuring techniques–are really important tools to detect photochemical changes with appreciable sensitivity due to heavy metal toxicity in photosynthetic organisms. Moreover, P700 absorbance measurements may well provide additional in vivo data to magnify our information on the impacts of heavy metals on PSI photochemistry in plants.

NO is one among the few known gaseous signaling molecules [17]. The high reactivity and diffusibility make NO perfect for a transient signaling molecule [19–21]. Both photorespiration and photosynthesis can be influenced by NO in various plants. Depending on its concentrations, the plant age or tissue, and the form of stress, some researchers reported NO as a stress promoting factor, whereas others have shown its ameliorating role [22–24]. Treatments with NO donors, such as SNP, have been shown to enhance photosynthetic rate, chlorophyll concentration, stomatal conductance and transpiration rate in plants [25]. In contrast, SNP diminished the quantity of β subunits of the RUBISCO subunit-binding protein and Rubisco activase in mung bean [26]. Cd toxicity is a major problem which inhibits many physiological processes in plants including photosynthesis and thus reduces crop yield. Therefore, the present work was undertaken with the objective of studying the ameliorating role of NO in alleviating photochemical damage induced by Cd stress in pea.

2.1 Plant Material, Treatments and Growing Conditions

Pea (Pisum sativum L.) seeds were surface sterilized by immersion in a 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution for 5 min and then washed three times with sterile, distilled water. Seeds were germinated on filter paper moistened with deionized water for 4 days. Following germination, seedlings were transferred to plastic pots filled with 2L hoagland solution [27] as a control treatment. At the same time, two concentrations of CdCl2 (50 and 200 μM) with or without SNP (NO donor) (50 μM) were added to the nutrient solution and used as the treatment solutions. Seedlings were grown in a growth chamber with 12 h day/12 h night, temperatures of 25/20°C day/night, white fluorescent light intensity of 350 μmol photons m–2·s–1, and 70% relative humidity. Growth solutions were continuously aerated and renewed every three days. After 15 days of treatment, a full expanded leaf was used for photosynthetic parameters measurements.

2.2 Determination of Chlorophyll

The chlorophyll determination was made following Arnon [28]. After discarding major veins and any tough, fibrous tissue, leaves were cut in small pieces. Fresh leaves weighing 0.5 g were grinded in 10 ml of 80% acetone (acetone:water 80:20 v:v) using a mortar and pestle. Leaf homogenate was filtered using filter paper. The extract was transferred to a graduated tube and filled to 10 ml with 80% acetone and assayed immediately. The absorbance was measured at 664, 647 and 470 nm in 1 cm cells using an 80% aqueous acetone as blank. Chl a, Chl b, total Chl (Chl a + b) and carotenoids concentrations were calculated using Arnon equation and expressed as mg·g−1 fresh weight.

2.3 Determination of Photosynthetic Rate, Transpiration Rate, Stomatal Conductance and Water Use Efficiency

Gas exchange was measured with a portable photosynthesis system CI-340 (CID Bio-Science). Photosynthetic (Pn) (μmol CO2 m−2·s−1), transpiration (Tn) (mmol H2O m−2 s−1), and stomatal conductance rates (mmol m–2·s–1) were registered every 30 sec on fully expanded leaves during 40 min. Measurements were performed on one randomly selected seedling per pot. From these data, a daily mean of measured indices was calculated. Water use efficiency (WUE) (μmol CO2 mmol H2O−1) was calculated by dividing the photosynthetic rate by the transpiration rate. The environmental conditions during the experiments were as follows: air flow rate 400 μmol·s−1, block and leaf temperatures 25°C, CO2 concentration in sample cell 300–400 μmol CO2 mol−1, relative humidity in sample cell 30%, lightness in quantum 180 μmol m−2·s−1.

2.4 Measurement of Chlorophyll Fluorescence and P700 Parameter

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters and the redox change of P700 were assessed with a Dual-PAM-100 measuring system (Walz) on fully expanded leaves. Leaves of the different treatments (Control, 50 μM SNP, 50 μM Cd, 50 μM Cd + 50 μM SNP, 200 μM Cd, and 200 μM Cd + 50 μM SNP) were exposed to darkness for 30 min before determining the following Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters: Fo; Fm; Fv/Fm = (Fm-Fo)/Fm; qN = Fm-Fm’/Fm-Fo; qL = qP(Fo’/F’); qP = (Fm’-F)/(Fm’-Fo’); NPQ = (Fm-Fm’)/(Fm’); Y(II) = (Fm’-Fo’)/Fm’; D = Fo′/Fm′; Y(NPQ) = 1-Y-Y(NO); Y(NO) = 1/NPQ + 1 + qL((Fm/Fo)-1); Y(I) = 1-Y(ND)-Y(NA); Y(NA) = (Pm-Pm’)/Pm, and Y(ND) = 1-P700 red.

One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was carried out using Graph Pad PRISM version 5.01. Multiple linear regression (MLR) and β-regression analysis were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2010 [29,30]. Values shown are means ±1 standard error (SE), and *, ** and *** represent significant differences at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01, and P ≤ 0.001, respectively.

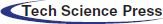

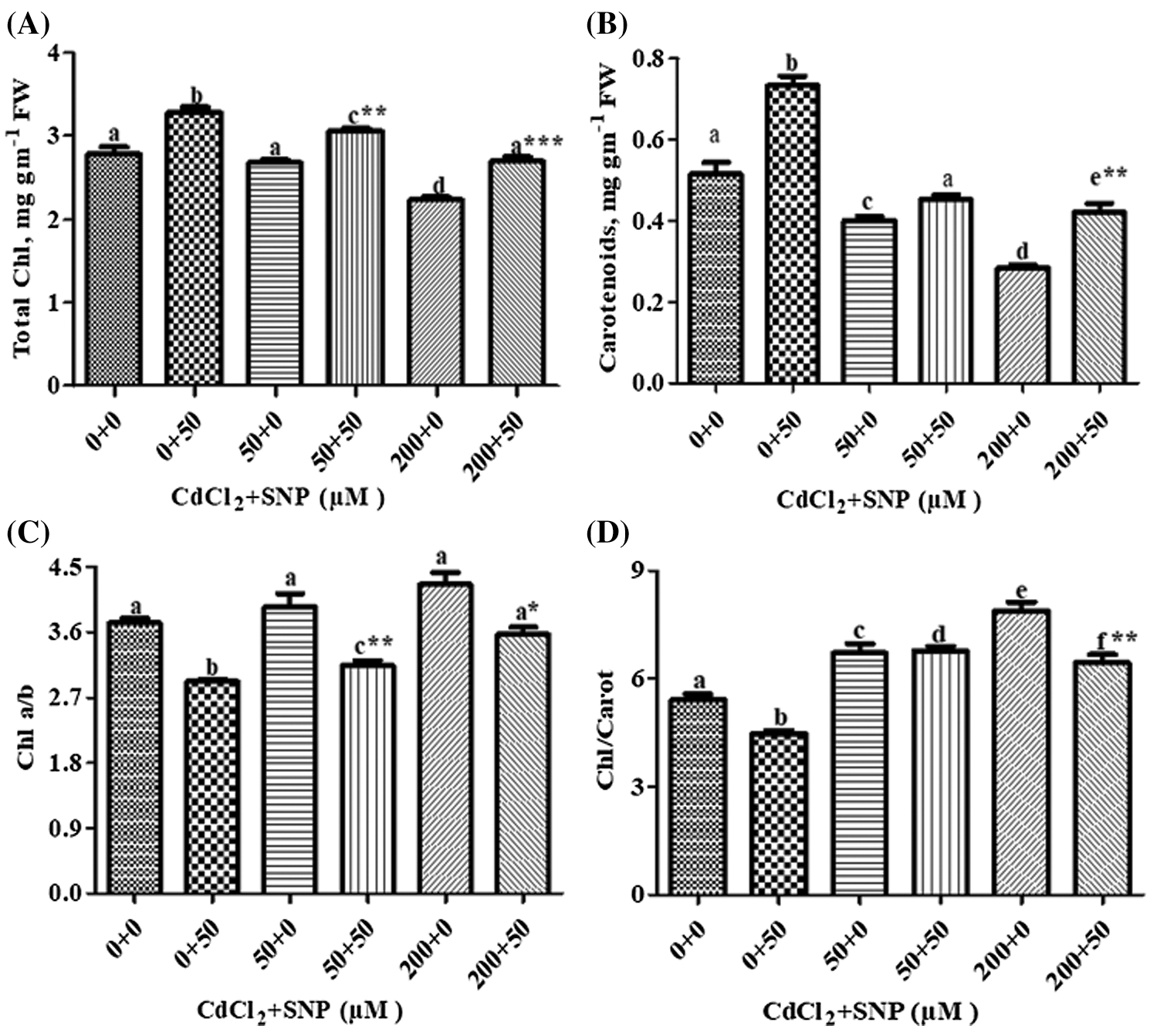

3.1 SNP Enhances Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Concentration under Cd Stress

Total Chl and carotenoids decreased by 3.95% and 24.00%, respectively, at 50 μM Cd, and by 20.00% and 46.00%, respectively, at 200 μM Cd-treated seedlings compared to controls (Figs. 1A and 1B). Ratios of Chl a/b and Chl/Carotenoid increased by 6.00% and 24.00%, respectively, at 50 μM Cd, and 14.00% and 46.00%, respectively, at the 200 μM Cd treatment compared to controls (Figs. 1C and 1D). Application of 50 μM SNP alone as well as in combination with 50 or 200 μM Cd improved photosynthetic pigment concentrations in Cd stressed plants. Application of 50 μM SNP with 50 or 200 μM Cd led to 15.00% or 22.00% increase in chlorophyll concentration, respectively; 13.00% or 50.00% increase in carotenoid concentration, respectively, 19.00% or 21.00% decrease in chl-a/b ratio, respectively, and 2.00% increase or 17.00% decrease in chl/carotenoids ratio, respectively, compared to the plants treated with 50 or 200 μM Cd alone. Moreover, multiple linear regression analysis (MLR) revealed that seedlings in presence of Cd resulted in a reduction of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll and carotenoid concentrations. However, the application of nitric oxide donor (SNP) along with Cd significantly increased the concentrations of all pigments. This is, while the relationships between Cd vs. the pigment concentrations were negative, those between Cd + SNP vs. the pigment concentrations were positive (Table 1).

Figure 1: Effect of Cd, SNP and their combinations on total chlorophyll (A), carotenoids (B), chlorophyll a/b (C) and chlorophyll/carotenoid (D) In leaves of pea seedlings. Values are means ±1 standard error (SE). Different letters represent significant differences compared to the control treatment at P ≤ 0.05. *, ** and *** represent significant differences between the Cd + SNP treatment and the Cd treatment at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01 and P ≤ 0.001, respectively

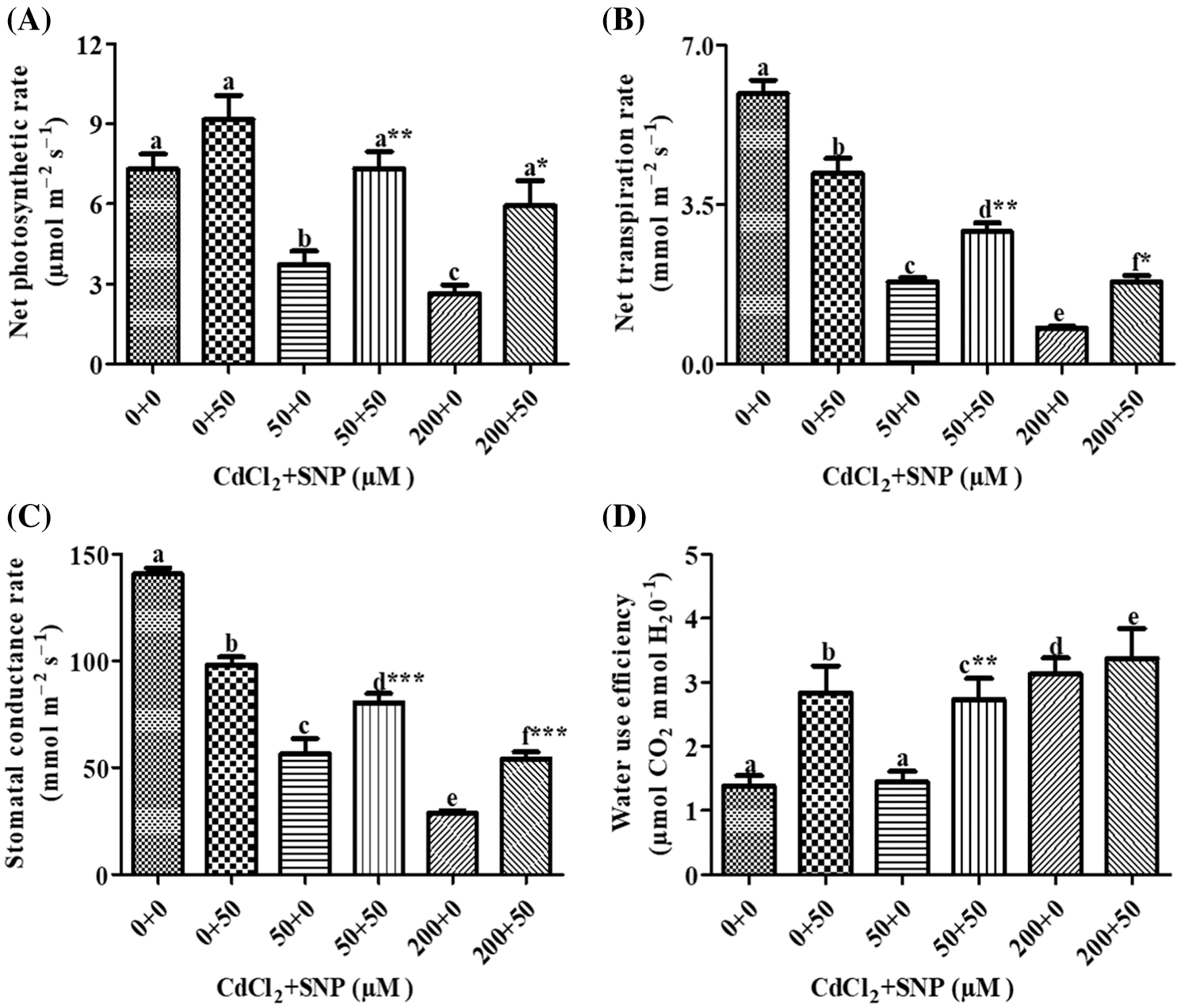

3.2 Photosynthesis Rate, Transpiration Rate, Stomatal Conductance and Water Use Efficiency

In the presence of 50 μM Cd, there were decreases of 49.31% in photosynthetic rate, 69.52% in transpiration rate and 59.89% in stomatal conductance on leaves of pea plants as compared to controls (Figs. 2A–2C). At 200 μM Cd concentration, photosynthetic rate decreased by 63.87%, transpiration rates by 86.60% and stomatal conductance by 80.00% as compared to controls. In plants treated with both 50 μM CdCl2 and 50 μM SNP, photosynthesis, transpiration rates and stomatal conductance were partially recovered by 97.75%, 60.89% and 43.00%, respectively, compared to those treated only with 50 μM CdCl2. Plants treated with 200 μM CdCl2 and 50 μM SNP showed 124.66%, 126.62% and 88.12% recovery in photosynthetic rate, transpiration rates and stomatal conductance, respectively, compared to plants treated only with 200 μM Cd (Figs. 2A–2C). Treatment of 50 or 200 μM Cd increased water use efficiency by 5.00% or 125.18%, respectively, as compared to the control treatments. However, plants treated with 50 or 200 μM CdCl2 along with 50 μM SNP showed an enhancement in water use efficiency by 88.89% and 8.34%, respectively, compared to plants treated only with 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 (Fig. 2D). Moreover, MLR also revealed that Cd application resulted in a decline in photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, and stomatal conductance of the plants, whereas Cd treatment with SNP significantly increased these parameters on pea plants (Table 1). This is, the relationships between the Cd levels vs. the photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, and stomatal conductance of the plants were negative. However, those between the Cd levels + SNP vs. the photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, and stomatal conductance of the plants were positive (Table 1).

Figure 2: Effect of Cd, SNP and their combinations on photosynthetic rate (A), transpiration rate (B), stomatal conductance rate (C) and water use efficiency (D) In leaves of pea seedlings. Values are means ±1 standard error (SE). Different letters represent significant differences compared to the control treatment at P ≤ 0.05. *, ** and *** represent significant differences between the Cd + SNP treatment and the Cd treatment at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01 and P ≤ 0.001, respectively

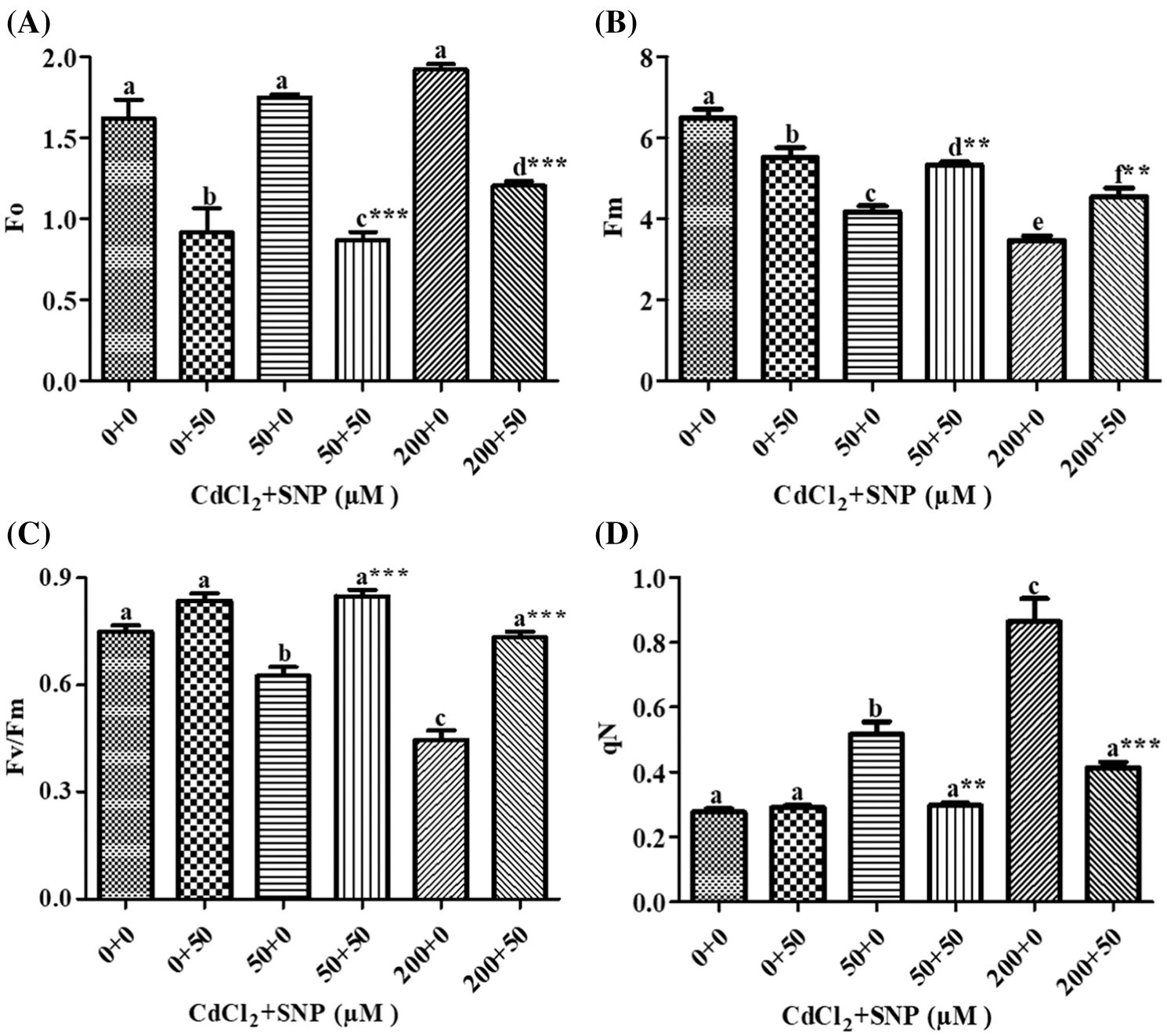

3.3 SNP Maintains Chlorophyll Fluorescence under Cd Stress

Fo, Fm and Fv/Fm were used to measure the photochemical efficiency and PSII activity. Compared to the control, Fo increased by 7.36% or 18.45% in leaves of 50 or 200 μM CdCl2 treated plants, respectively. Addition of 50 μM SNP along with the 50 or 200 μM CdCl2 treatment resulted in a significant decrease of 44.00% or 37.24%, respectively, as compared to plants treated with 50 or 200 μM CdCl2 alone (Fig. 3A). Compared to the control, Fm decreased by 35.71% or 46.47% in the 50 or 200 μM CdCl2 treatment, respectively. Addition of the 50 μM SNP treatment resulted in a significant increase of 27.85% or 30.88% in comparison to plants treated with 50 or 200 μM CdCl2, respectively (Fig. 3B). In contrast, Fv/Fm in 50 or 200 μM Cd-treated pea leaves decreased by 16.56% or 40.53%, respectively, as compared to the control. However, the 50 μM SNP treatment inhibited the decrease of Fv/Fm by 35.79% or 64.48% as compared to plants treated with 50 or 200 μM Cd alone, respectively (Fig. 3C). qN in 50 or 200 μM CdCl2-treated plants increased by 87.36% or 2.14 folds, respectively, compared to the control. However, 50 μM SNP treatment along with 50 or 200 μM CdCl2 inhibited the increase of qN by 42.76% or 53.00%, respectively (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3: Effect of Cd, SNP and their combinations on Fo (A), Fm (B), Fv/Fm (C), and qN (D) on leaves of pea seedlings. Values are means ±1 standard error (SE). Different letters represent significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 as compared to the control. *, ** and *** represent significant differences between the Cd + SNP treatment and the Cd treatment at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01 and P ≤ 0.001, respectively

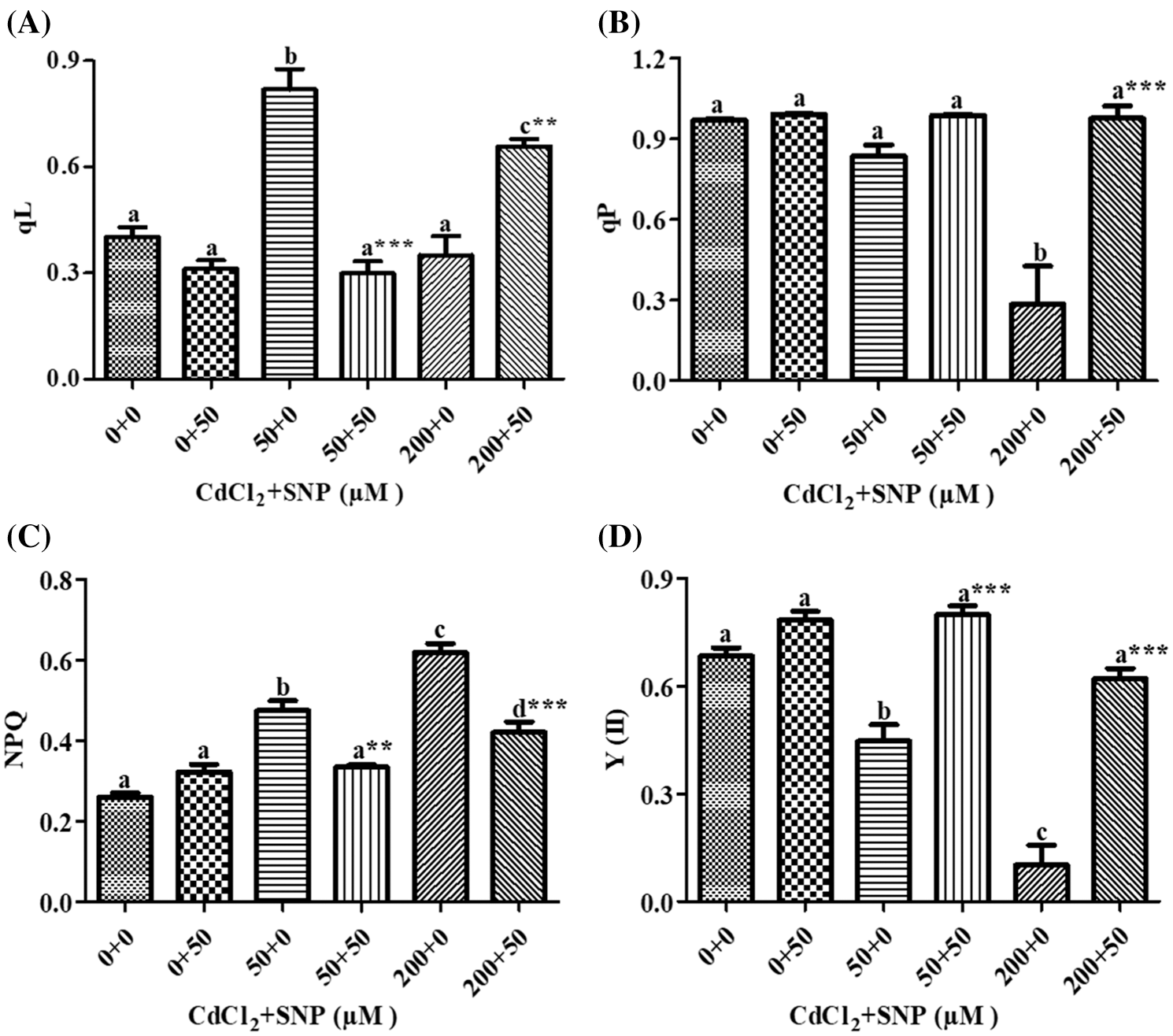

In our study, qL increased by 103.35% and decreased by 42.67% on leaves of 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treated seedlings, respectively, compared to the control (Fig. 4A). In turn, 50 μM SNP treatment decreased qL by 63.50% and increased it by 1.86 folds in comparison to the 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatments, respectively (Fig. 4A). qP decreased by 13.65% and 70.65% on leaves of 50 and 200 μM CdCl2-treated seedlings, respectively, in comparison to the control. The 50 μM SNP treatment decreased qP by 18.15% and 2.48 folds as compared to the 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatments, respectively (Fig. 4B). NPQ increased by 82.28% and 137.36% in 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatment, respectively, over values on the control. However, 50 μM SNP treatment inhibited the increase of NPQ by 29.45% and 32.02% as compared to 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatments, respectively (Fig. 4C). Y(II) was decreased by 34.72% and 86.00% to the 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatements, respectively in comparison to the control (Fig. 4D), However, 50 μM SNP treatment inhibited the decreases in Y(II) by 78.63% and 5 folds as compared to 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatments, respectively (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4: Effect of Cd, SNP and their combinations on qL (A), qP (B), NPQ (C), and Y(II) (D) on leaves of pea seedlings. Values are means ±1 standard error (SE). Different letters represent significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 as compared to the control. *, ** and *** represent significant differences between the Cd + SNP treatment and the Cd treatment at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01 and P ≤ 0.001, respectively

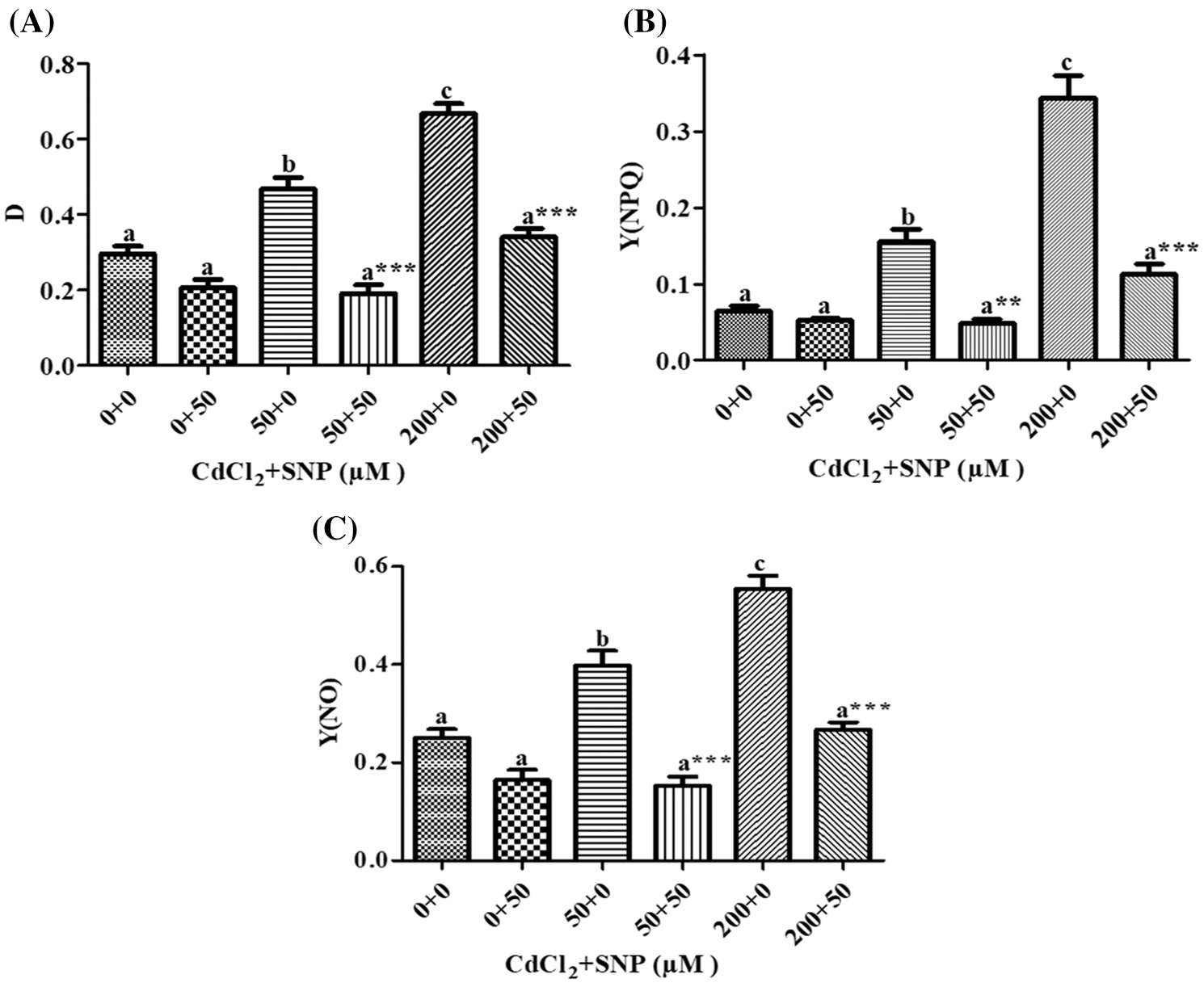

Our results showed that on leaves of 50 and 200 μM CdCl2-treated seedlings, dissipated thermally D increased by 58.35% and 1.26 folds, respectively, (Fig. 5A); Y(NPQ) increased by 1.38 folds and 4.28 folds, respectively, (Fig. 5B), and Y(NO) increased by 59.16% and 121.69%, respectively, (Fig. 5C), in comparison to controls. However, 50 μM SNP treatment inhibited (1) the increase in D by 59.14% and 50%, (2) the increase in Y(NO) by 61.62% and 51.96%, and (3) the decrease in Y(NPQ) by 68.72% and 67.23% in comparison to the 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatments, respectively (Figs. 5A–5C).

Figure 5: Effect of Cd, SNP and their combinations on D (A), Y(NPQ) (B) and Y(NO) (C) on leaves of pea seedlings. Values are means ±1 standard error (SE). Different letters represent significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 as compared to the control. *, ** and *** represent significant differences between the Cd + SNP treatment and the Cd treatment at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01 and P ≤ 0.001, respectively

Moreover, MLR also revealed that Cd application resulted in a decline of Fm, Fv/Fm, Y(II) and qP, and an increase of Fo, qN, qL, NPQ, D, Y(NPQ) and Y(NO) of the fluorescence parameter. In turn, the Cd treatment with SNP significantly increased Fm, Fv/Fm, qP, and Y(II), and decreased Fo, qN, qL, NPQ, D, Y(NPQ) and Y(NO) of the fluorescence parameter on pea plants. The relationship between the Cd levels vs. (1) Fm, Fv/Fm, Y(II) and qP was negative, and (2) Fo, qN, qL, NPQ, D, Y(NPQ) and Y(NO) of the fluorescence parameter was positive (Table 1). In turn, the relationship between the SNP treatment vs. (1) Fm, Fv/Fm, qP, and Y(II) was positive, and (2) Fo, qN, qL, NPQ, D, Y(NPQ) and Y(NO) of the fluorescence parameter was negative (Table 1).

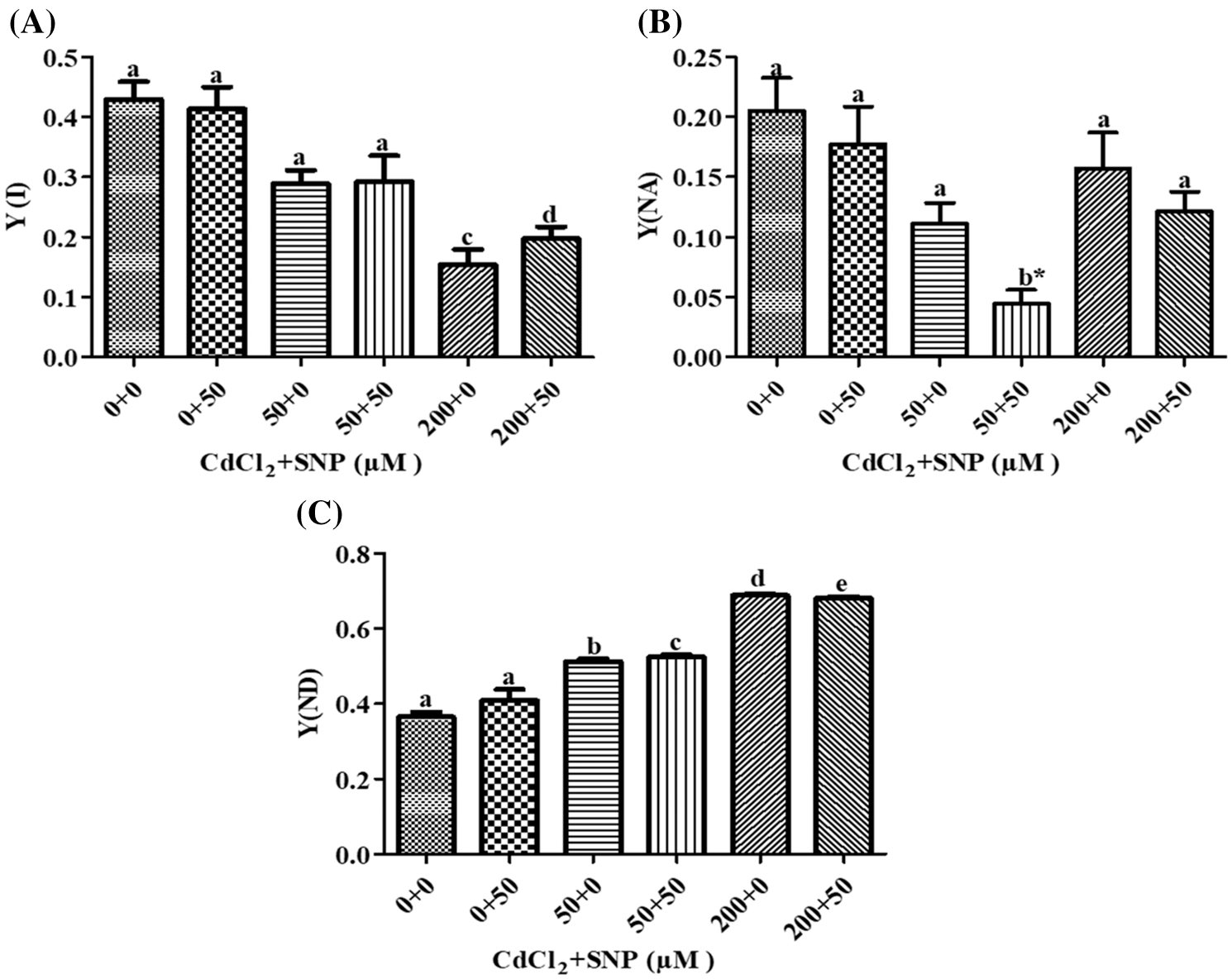

3.4 Effect of SNP on PSI under Cd Stress

In our study, Y (I) decreased by 30.96% and 62.80% on leaves of 50 and 200 μM CdCl2-treated plants, respectively, as compared to control (Fig. 6A). Addition of 50 μM SNP along with Cd did not show a significant change in Y (I) when compared to the Cd treatments. Furthermore, Y(NA) decreased by 45.89% and 23.63% due to the 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatments, respectively. Addition of 50 μM SNP to50 and 200 μM CdCl2 further reduced Y(NA) by 60.23% and 22.77% compared to the 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatment, respectively (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, Y(ND) increased by 46.63% and 88.76% due to the 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatments, respectively. Supplementation of 50 μM SNP with 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 did not cause any significant change in Y(ND) in comparison to the 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 treatments (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6: Effect of Cd, SNP and their combinations on PSI Y(I) (A), Y(NA) (B), and Y(ND) (C) in leaves of pea seedlings. Values are means ±1 standard error (SE). Different letters represent significant differences at P ≤ 0.05 as compared to the control. *, ** and *** represent significant differences between the Cd + SNP treatment and the Cd treatment at P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01 and P ≤ 0.001, respectively

MLR revealed that Cd treatment caused reduction in Y(I) and Y(NA) but increased Y(ND). However, the application of the nitric oxide donor (SNP) along with Cd significantly increased Y(I) and Y(ND) and decreased Y(NA). The relationships between the Cd levels vs. Y(I) and Y(NA) were negative while that vs. Y(ND) was positive (Table 1). In turn, the relationship between SNP vs. Y(I) and Y(ND) was positive while that vs. Y (NA) of PSI was negative (Table 1).

Photosynthesis is considered as one of the most important physiological processes in plants. The whole metabolism of plants specifically or by implication depends on this process and hence any change in photosynthetic rate will automatically affect the remaining plant processes. Cd can inhibit photosynthesis and induce damage and dysfunction of chloroplast. This decrease may be because of (i) inhibition of photosynthetic electron transport chain [31], (ii) inhibition of the enzymes required for Chl biosynthesis [31], (iii) disturbance in the PSII reaction center [32], (iv) replacement of central Mg2+ of Chl [33] and (v) reduction in P uptake which is involved in pigment biosynthesis [33]. The Cd could harm chloroplast submicroscopic structure, through damaging grana stacking structure [34,35]. The ability of the chloroplast for capturing light energy is greatly decrease in presence of Cd, thus affecting the role of many functions associated with photosynthesis [36].

Our results showed less concentration of photosynthetic pigments in leaves of Cd-treated Pisum sativum. This could be because of Cd-led increases in the activity of chlorophyllase, inhibition of the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of photosynthetic pigments and destruction of photosynthetic pigments by oxidative stress [37]. In the present study, a significant loss in chlorophyll concentration was seen in Cd-treated plants. Chl b was affected more strongly than Chl a. Chlorophyll concentration was also strongly diminished in Oryza sativa [38], Hordeum vulgare [39], Lycopersicon esculentum [40–42], Zea mays [43] and Brassica oleracea [44,45] exposed to Cd. A putative debasement of chlorophyll and additionally the hindrance of its biosynthesis were proposed to be responsible for the inhibition of photosynthesis and growth due to Cd [36]. In the present study, NO supplementation to Cd stressed plants reverted chlorophyll loss in pea which can be corroborated with findings in maize [46], lettuce [47,48], fava bean [31] and mustard [49] under Cd toxicity. Increased Chl due to NO supplementation could be due to reduced oxidative stress and damage to chlorophyll pigments in Cd-treated plants (Fig. 1A). NO inhibits photosynthetic pigment degradation by protecting the photosynthetic membrane, Rubisco, cytochrome b6/f, and D1 and D2 proteins [50]. Carotenoids by acting as light-harvesting pigments can protect chlorophyll and membranes from damage by quenching triplet chlorophyll and removing oxygen from the excited chlorophyll [51]. Carotenoids enhancement in pea plants exposed to 50 μM SNP with 50 μM Cd and 200 μM Cd-treated plants (Fig. 1B) may reflect an attempt to protect chlorophyll and the photosynthetic mechanical assembly from the photo oxidative destruction of Cd toxicity [52]. Our results suggested Cd-induced inhibition of the photosynthesis rate, transpiration rate, and stomatal conductance in pea plants (Figs. 2A–2C). Similar to our results, several studies have shown Cd-led inhibition in photosynthesis rate, transpiration rate, and stomatal conductance in pea plants [53]. The observed amelioration in photosynthesis rate, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance and water use efficiency in presence of SNP could be due to the impact of NO on stomatal closure (Figs. 2A–2C).

PSII is one of the prime targets of Cd toxicity. Chl fluorescence was studied to evaluate the effects of Cd, SNP and the combination of Cd and SNP on PSII on Cd-stressed pea plants. Similar to prior studies, Cd diminished PSII values and decreased electron yield of PSII [9,54]. The Fv/Fm, representing the maximal efficiency of excitation energy capture by the ‘‘open’’ PSII reaction center, is usually used as a stress indicator on plants [55]. In this study, the Fv/Fm ratio decreased with Cd treatment (Fig. 3C). In pea plants exposed to 50 and 200 μM Cd, the increase of Fo and the decrease of Fm resulted in a reduction of the Fv/Fm ratio (Fig. 3A–3C). An increase of Fo points to photo damage, and a decline in Fm, reflect an enhanced non-radiative energy. The Fv/Fm was reduced in several plant species, including pea, exposed to Cd [56]. The decrease in Fv/Fm and PSII efficiency suggested that Cd stress led to the inhibition of the PSII photoactivation. This might have been due to damage of the antennae pigments and the limitation of QA (quinone) reoxidation due to the decrease or partial blockage of the electron transport from PSII to PSI [57]. The exogenous application of SNP increased the Fv/Fm ratio, which specifies that the plant is healthy, and not suffering from photoinhibition (Fig. 3C).

Under various stress conditions, an increment in NPQ and qN can be associated with photoinactivation of PSII reaction centers, that leads to an oxidative damage to the reaction centers and an increase in Fo [58]. In the present study qN and NPQ increments were with increases in Fv/Fm under Cd toxicity (Figs. 3D and 4C). Use of SNP along with Cd led to a decrease in qN and NPQ through regulating photochemistry. It can be considered as an additional mechanism to adjust for the excess of absorbed light energy; therefore, SNP counters photoinhibition of PSII caused by Cd toxicity. Under Cd stress, SNP increased Fv/Fm and photochemical efficiency, and decreased NPQ and qN of PSII in ryegrass seedling leaves treated with NaHCO3 [59]. SNP restored the chlorophyll fluorescence. This might have been due to its role in (i) protecting the pigment systems from oxidative damage, (ii) keeping up the chlorophyll biosynthesis.

PSI is considered to be less sensitive to heavy metals; however, apart from a few exceptions [35], earlier studies generally preferred several artificial electron donors and inhibitors to study the PSI activity [16,60] under heavy-metal stress, which may itself affect the PSI activity. Therefore, in the current study we used P700 absorbance measurements, which made direct, noninvasive monitoring of the PSI photochemistry in whole leaves without using electron donors or inhibitors. Our results clearly indicated that Cd decreased PSI photochemistry. Significant damages were observed to the photosynthetic electron transport at concentrations of 50 and 200 μM CdCl2 (Fig. 6A). PSI efficiency measurements on the Cd-treated plants revealed decreased yields of PSI Y(I), and Y(NA), and increased Y(ND), which can be caused by an increased cyclic electron flow (CEF) around the PSI (Figs. 6A–6C). Earlier reports demonstrated that Cd caused iron deficiency in cell organelles which is probably a reason for PSI damage [61,62]. Long-term iron deficiency resulted in ROS production in thylakoids which primarily damage iron-sulphur centres (PSI) and LHC I antennae [63]. Cd-induced damage to PSI has been noticed in Cucumis sativus [64,65] and Triticum aestivum [66]. Unlike the chlorophyll concentration and PSII, SNP treatment did not show any ameliorative effects on PSI parameters. These results suggest that Cd stress caused damage to both PSI and PSII in Pisum sativum. They also suggest that exogenous NO application is useful in mitigating the Cd-induced damage to photosynthesis on pea seedlings because of its ameliorating effects on the photosynthetic pigment concentrations and PSII.

Funding Statement: The authors thank to DBT for the financial support of BUILDER Project No. BT/PR-9028/INF/22/193/2013. EAK acknowledge the receipt of UGC-MANF for minority students, MM acknowledge the award of UGC-PDF for women, and PS thanks to UGC-FRP during the period of this work.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Sharma, A., Kumar, V., Shahzad, B., Ramakrishnan, M., Sidhu, G. P. S. et al. (2019). Photosynthetic response of plants under different abiotic stresses: A review. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 39, 509–531. DOI 10.1007/s00344-019-10018-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Xu, W., Lu, G., Dang, Z., Liao, C., Chen, Q. et al. (2013). Uptake and distribution of Cd in sweet maize grown on contaminated soils: A field-scale study. Bioinorganic Chemistry and Applications, 1, 2013. DOI 10.1155/2013/959764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Azevedo, H., Gloria Pinto, C. G., Fernandes, J., Loureiro, S., Santos, C. A. O. (2005). Cadmium effects on sunflower growth and photosynthesis. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 28(12), 2211–2220. DOI 10.1080/01904160500324782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sharma, A., Kapoor, D., Wang, J., Shahzad, B., Kumar, V. et al. (2020). Chromium bioaccumulation and its impacts on plants: An overview. Plants, 9, 100. DOI 10.3390/plants9010100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mittler, R. (2002). Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends in Plant Science, 7(9), 405–410. DOI 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sharma, P., Jha, A. B., Dubey, R. S., Pessarakli, M. (2012). Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. Journal of Botany, 2012, 1–26. DOI 10.1155/2012/217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Siddiqui, M. H., Alamri, S., Nasir Khan, M., Corpas, F. J., Al-Amri, A. A. et al. (2020). Melatonin and calcium function synergistically to promote the resilience through ROS metabolism under arsenic-induced stress. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 398, 122882. DOI 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bielen, A., Remans, T., Vangronsveld, J., Cuypers, A. (2013). The influence of metal stress on the availability and redox state of ascorbate, and possible interference with its cellular functions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 14(3), 6382–6413. DOI 10.3390/ijms14036382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hattab, S., Dridi, B., Chouba, L., Kheder, M. B., Bousetta, H. (2009). Photosynthesis and growth responses of pea (Pisum sativum L.) under heavy metals stress. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 21(11), 1552–1556. DOI 10.1016/S1001-0742(08)62454-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Siddiqui, M. H., Al-Whaibi, M. H., Sakran, A. M., Basalah, M. O., Ali, H. M. (2012). Effect of calcium and potassium on antioxidant system of Vicia faba L. under cadmium stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 13(6), 6604–19. DOI 10.3390/ijms13066604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Khan, M. N., Manzer, H. S., Mazen, A. A., Saud, A., Yanbo, H. et al. (2020). Crosstalk of hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide requires calcium to mitigate impaired photosynthesis under cadmium stress by activating defense mechanisms in Vigna radiata. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 156, 278–90. DOI 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.09.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kapoor, D., Singh, M. P., Kaur, S., Bhardwaj, R., Zheng, B. et al. (2019). Modulation of the functional components of growth, photosynthesis, and anti-oxidant stress markers in cadmium exposed Brassica juncea L. Plants, 8, 260. DOI 10.3390/plants8080260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kupper, H., Kupper, F., Spiller, M. (1996). Environmental relevance of heavy metal-substituted chlorophylls using the example of water plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 47(2), 259–266. DOI 10.1093/jxb/47.2.259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kaur, P., Bali, S., Sharma, A., Kohli, S. K., Vig, A. P. et al. (2019). Cd induced generation of free radical species in Brassica juncea is regulated by supplementation of earthworms in the drilosphere. Science of the Total Environment, 655, 663–675. DOI 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lu, C., Qiu, N., Wang, B., Zhang, J. (2003). Salinity treatment shows no effects on photosystem II photochemistry, but increases the resistance of photosystem II to heat stress in halophyte Suaeda salsa. Journal of Experimental Botany, 54(383), 851–860. DOI 10.1093/jxb/erg080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chugh, L. K., Sawhney, S. K. (1999). Photosynthetic activities of Pisum sativum seedlings grown in presence of cadmium. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 37(4), 297–303. DOI 10.1016/S0981-9428(99)80028-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Khan, E. A., Misra, M., Sharma, P., Misra, A. N. (2017). Effects of exogenous nitric oxide on protein, proline, MDA contents and antioxidative system in Pea seedling (Pisum sativum L.). Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 10, 3137–3142. DOI 10.5958/0974-360X.2017.00558.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Assche, F. V., Clijsters, H. (1990). Effects of metals on enzyme activity in plants. Plant, Cell & Environment, 13(3), 195–206. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1990.tb01304.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Misra, A. N., Misra, M., Singh, R. (2010). Nitric oxide biochemistry, mode of action and signaling in plants. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research, 4(25), 2729–2739. DOI 10.5897/JMPR.9000930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Misra, A. N., Misra, M., Singh, R. (2011). Nitric oxide ameliorates stress responses in plants. Plant Soil and Environment, 57(3), 95–100. DOI 10.17221/PSE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Siddiqui, M. H., Saud, A., Qasi, D. A., Hayssam, M. A., Khan, M. N. et al. (2020). Exogenous nitric oxide alleviates sulfur deficiency-induced oxidative damage in tomato seedlings. Nitric Oxide-Biology and Chemistry, 94, 95–107. DOI 10.1016/j.niox.2019.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hsu, Y. T., Kao, C. H. (2004). Cadmium toxicity is reduced by nitric oxide in rice leaves. Plant Growth Regulation, 42(3), 227–238. DOI 10.1023/B:GROW.0000026514.98385.5c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sharma, A., Sidhu, G. P. S., Araniti, F., Bali, A. S., Shahzad, B. et al. (2020). The role of salicylic acid in plants exposed to heavy metals. Molecules, 25, 540. DOI 10.3390/molecules25030540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sharma, A., Soares, C., Sousa, B., Martins, M., Kumar, V. et al. (2020). Nitric oxide-mediated regulation of oxidative stress in plants under metal stress: A review on molecular and biochemical aspects. Physiologia Plantarum, 168, 318–344. DOI 10.1111/ppl.13004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Khan, M. N., M., M., Zahid, K. A., Manzer, H. S. (2017). Nitric oxide-induced synthesis of hydrogen sulfide alleviates osmotic stress in wheat seedlings through sustaining antioxidant enzymes, osmolyte accumulation and cysteine homeostasis. Nitric Oxide-Biology and Chemistry, 68, 91–102. DOI 10.1016/j.niox.2017.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Siddiqui, M. H., Saud, A. A., Mutahhar, Y. Y. A. K., Mohammed, A. A. Q., Hayssam, M. A. et al. (2017). Sodium nitroprusside and indole acetic acid improve the tolerance of tomato plants to heat stress by protecting against DNA damage. Journal of Plant Interactions, 12(1), 177–86. DOI 10.1080/17429145.2017.1310941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hoagland, D. R., Arnon, D. I. (1950). The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Circular California Agricultural Experiment Station, 347(2nd edit), 32. DOI 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)73482-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Arnon, D. I. (1949). Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiology, 24(1), 1. DOI 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sharma, A., Kumar, V., Bhardwaj, R., Thukral, A. K. (2017). Seed pre-soaking with 24-epibrassinolide reduces the imidacloprid pesticide residues in green pods of Brassica juncea L. Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry, 99, 95–103. DOI 10.1080/02772248.2016.1146955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sharma, A., Kumar, V., Singh, R., Thukral, A. K., Bhardwaj, R. (2016). Effect of seed pre-soaking with 24-epibrassinolide on growth and photosynthetic parameters of Brassica juncea L. in imidacloprid soil. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 133, 195–201. DOI 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.07.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Feng, Y., Fu, X., Han, L, Xu, C., Liu, C. et al. (2021). Nitric oxide functions as a downstream signal for melatonin-induced cold tolerance in cucumber seedlings. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 1432. DOI 10.3389/fpls.2021.686545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sakouhi, L., Kharbech, O., Massoud, M. B., Munemasa, S., Murata, Y. et al. (2021). Oxalic Acid Mitigates Cadmium Toxicity in Cicer arietinum L. Germinating Seeds by Maintaining the Cellular Redox Homeostasis. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 187, 1–13. DOI 10.1007/s00344-021-10334-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kamran, M., Wang, D., Alhaithloul, HAS., Alghanem, S.M., Aftab, T. et al. (2021). Jasmonic acid-mediated enhanced regulation of oxidative, glyoxalase defense system and reduced chromium uptake contributes to alleviation of chromium (VI) toxicity in choysum (Brassica parachinensis L.). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 208, 111758. DOI 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Goussi, R., Manaa, A., Derbali, W., Ghnaya, T., Abdelly, C. et al. (2018). Combined effects of NaCl and Cd2+ stress on the photosynthetic apparatus of Thellungiella salsuginea. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Bioenergetics, 1859(12), 1274–1287. DOI 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Moussa, H. R., El-Gamal, S. M. (2010). Role of salicylic acid in regulation of cadmium toxicity in heat (Triticum aestivum L.). Journal of Plant Nutrition, 33(10), 1460–1471. DOI 10.1080/01904167.2010.489984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Sandalio, L. M., Dalurzo, H. C., Gomez, M., Romero Puertas, M. C., Del Rio, L. A. (2001). Cadmium induced changes in the growth and oxidative metabolism of pea plants. Journal of Experimental Botany, 52(364), 2115–2126. DOI 10.1093/jexbot/52.364.2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yildiztugay, E., Ceyda, O. K., Fevzi, E., Aysegul, Y., Mustafa, K. (2019). Humic acid protects against oxidative damage induced by cadmium toxicity in wheat (Triticum aestivum) roots through water management and the antioxidant defence system. Botanica Serbica, 43(2), 161–73. DOI 10.2298/BOTSERB1902161Y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Singh, P., Shah, K. (2014). Evidences for reduced metal-uptake and membrane injury upon application of nitric oxide donor in cadmium stressed rice seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 83, 180–184. DOI 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.07.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Vassilev, A., Lidon, F. C., Matos, M. D. C. U., Ramalho, J. C., Yordanov, I. (2002). Photosynthetic performance and content of some nutrients in cadmium-and copper-treated barley plants. Journal of Plant Nutrition, 25(11), 2343–2360. DOI 10.1081/PLN-120014699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ammar, W. B., Nouairi, I., Zarrouk, M., Ghorbel, M. H., Jemal, F. (2008). Antioxidative response to cadmium in roots and leaves of tomato plants. Biologia Plantarum, 52(4), 727. DOI 10.1007/s10535-008-0140-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Anjum, N. A., Sharma, P., Gill, S. S., Hasanuzzaman, M., Khan, E. A. et al. (2016). Catalase and ascorbate peroxidase—representative H2O2-detoxifying heme enzymes in plants. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23, 19002–19029. DOI 10.1007/s11356-016-7309-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lopez-Millan, A. F., Sagardoy, R., Solanas, M., Abadia, A. N., Abadia, J. (2009). Cadmium toxicity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants grown in hydroponics. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 65(2), 376–385. DOI 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ekmekci, Y., Tanyolac, D., Ayhan, B. (2008). Effects of cadmium on antioxidant enzyme and photosynthetic activities in leaves of two maize cultivars. Journal of Plant Physiology, 165(6), 600–611. DOI 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.01.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Mobin, M., Khan, N. A. (2007). Photosynthetic activity, pigment composition and antioxidative response of two mustard (Brassica juncea) cultivars differing in photosynthetic capacity subjected to cadmium stress. Journal of Plant Physiology, 164(5), 601–610. DOI 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kaur, R., Yadav, P., Thukral, A. K., Sharma, A., Bhardwaj, R. et al. (2018). Castasterone and citric acid supplementation alleviates cadmium toxicity by modifying antioxidants and organic acids in Brassica juncea. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation, 37, 286–299. DOI 10.1007/s00344-017-9727-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Siddiqui, M. H., Al-Whaibi, M. H., Mohammed, O. B. (2011). Role of nitric oxide in tolerance of plants to abiotic stress. Protoplasma, 248(3), 447–455. DOI 10.1007/s00709-010-0206-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Beligni, M. V., Lamattina, L. (2000). Nitric oxide stimulates seed germination and de-etiolation, and inhibits hypocotyl elongation, three light-inducible responses in plants. Planta, 210(2), 215–221. DOI 10.1007/PL00008128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Sharma, A., Shahzad, B., Kumar, V., Kohli, S. K., Sidhu, G. P. S. et al. (2019). Phytohormones regulate accumulation of osmolytes under abiotic stress. Biomolecules, 9, 285. DOI 10.3390/biom9070285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ahmad, P., Sarwat, M., Bhat, N. A., Wani, M. R., Kazi, A. G. et al. (2015). Alleviation of cadmium toxicity in Brassica juncea L. (Czern. & coss.) by calcium application involves various physiological and biochemical strategies. PLoS One, 10(1), e0114571. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0114571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Li, X., Gong, B., Xu, K. (2014). Interaction of nitric oxide and polyamines involves antioxidants and physiological strategies against chilling-induced oxidative damage in Zingiber officinale Roscoe. Scientia Horticulturae, 170, 237–248. DOI 10.1016/j.scienta.2014.03.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Young, A. J. (1991). The photoprotective role of carotenoids in higher plants. Physiologia Plantarum, 83(4), 702–708. DOI 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1991.tb02490.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Choudhury, N. K., Behera, R. K. (2001). Photoinhibition of photosynthesis: Role of carotenoids in photoprotection of chloroplast constituents. Photosynthetica, 39(4), 481–488. DOI 10.1023/A:1015647708360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Januškaitienė, I. (2010). Impact of low concentration of cadmium on photosynthesis and growth of pea and barley. Environmental Research, Engineering and Management, 53, 24–29. DOI 10.5755/j01.erem.53.3.85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Burzynski, M., Klobus, G. (2004). Changes of photosynthetic parameters in cucumber leaves under Cu, Cd, and Pb stress. Photosynthetica, 42(2), 505–510. DOI 10.1007/S11099-005-0005-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Broddrick, J. T., Welkie, D. G., Jallet, D., Golden, S. S., Peers, G. et al. (2019). Predicting the metabolic capabilities of Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 adapted to different light regimes. Metabolic Engineering, 52, 42–56. DOI 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Kycko, M., Romanowska, E., Zagajewski, B. (2019). Lead-induced changes in fluorescence and spectral characteristics of pea leaves. Remote Sensing, 11(16), 1885. DOI 10.3390/rs11161885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Mallick, N., Mohn, F. H. (2003). Use of chlorophyll fluorescence in metal-stress research: A case study with the green microalga Scenedesmus. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 55(1), 64–69. DOI 10.1016/S0147-6513(02)00122-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Baker, N. R. (2008). Chlorophyll fluorescence: A probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 59, 89–113. DOI 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Liu, M., Qi, H., Zhang, Z. P., Song, Z. W., Kou, T. J. et al. (2012). Response of photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence to drought stress in two maize cultivars. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 7(34), 4751–4760. DOI 10.5897/ajar12.082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Zhou, W., Juneau, P., Qiu, B. (2006). Growth and photosynthetic responses of the bloom-forming cyanobacterium microcystis aeruginosa to elevated levels of cadmium. Chemosphere, 65(10), 1738–1746. DOI 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Lu, J., Wang, Z., Yang, X., Wang, F., Qi, M., Li, T. et al. (2020). Cyclic electron flow protects photosystem I donor side under low night temperature in tomato. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 177, 104151. DOI 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Timperio, A. M., D’Amici, G. M., Barta, C., Loreto, F., Zolla, L. (2007). Proteomics, pigment composition, and organization of thylakoid membranes in iron-deficient spinach leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany, 58(13), 3695–3710. DOI 10.1093/jxb/erm219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Michel, K. P., Pistorius, E. K. (2004). Adaptation of the photosynthetic electron transport chain in cyanobacteria to iron deficiency: The function of IdiA and IsiA. Physiologia Plantarum, 120(1), 36–50. DOI 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.0229.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Sarvari, E. (2005). Effects of heavy metals on chlorophyll and protein complexes in higher plants. In: Handbook of photosynthesis (Second edition). USA: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

65. Sun, H., Dai, H., Wang, X., Wang, G. (2016). Physiological and proteomic analysis of selenium-mediated tolerance to Cd stress in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 133, 114–126. DOI 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Atal, N., Saradhi, P. P., Mohanty, P. (1991). Inhibition of the chloroplast photochemical reactions by treatment of wheat seedlings with low concentrations of cadmium: Analysis of electron transport activities and changes in fluorescence yield. Plant and Cell Physiology, 32(7), 943–951. DOI 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a078181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |