| Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany |  |

DOI: 10.32604/phyton.2022.021507

ARTICLE

Participation of Auxin Transport in the Early Response of the Arabidopsis Root System to Inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense

1Laboratorio de Transducción de Señales, Edificio B3, Instituto de Investigaciones Químico-Biológicas de la Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Ciudad Universitaria, Morelia, 58030, México

2Tecnológico de Monterrey, School of Engineering and Sciences, Campus Querétaro, San Pablo, Querétaro, 76130, México

3School of the Environment, Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, 32307, USA

*Corresponding Author: Elda Beltrán-Peña. Email: eldabelt@umich.mx

Received: 18 January 2022; Accepted: 09 April 2022

Abstract: The potential of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) has been demonstrated in the case of plant inoculation with bacteria of the genus Azospirillum which improves yield. A. brasilense produces a wide variety of molecules, including the natural auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), as well as other phytoregulators. However, several studies have suggested that auxin induces changes in plant development during their interaction with the bacteria. The effects of A. brasilense Sp245 on the development of Arabidopsis thaliana root were investigated to help explain the molecular basis of the interaction. The results obtained showed a decrease in primary root length from the first day and remained so throughout the exposure, accompanied by a stimulation of initiation and maturation of lateral root primordia and an increase of lateral roots. An enhanced auxin response was evident in the vascular tissue and lateral root meristems of inoculated plants. However, after five days of bacterization, the response disappeared in the primary root meristems. The role of polar auxin transport (PAT) in auxins relocation involved the PGP1, AXR4-1, and BEN2 proteins, which apparently mediated A. brasilense-induced root branching of Arabidopsis seedlings.

Keywords: Auxin; Azopirillum brasilense; Arabidopsis; auxin transport; lateral roots

The inoculation with bacteria of the genus Azospirillum, a well-known PGPR, has demonstrated the potential of these microorganisms to promote plant growth and improve crop yield in different types of soil and growth conditions. The most common phenotype in roots modulated by PGPR is the inhibition of primary root growth coupled with proliferation and growth of lateral roots and root hairs, which support vegetative, green biomass [1–3]. Azospirillum produces many molecules, including the natural auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and harbors lipopolysaccharides that elicit complex responses in the plant [4]. IAA regulates virtually any aspect of the plant’s development, so a large number of studies have focused on analyzing the beneficial effect of IAA produced by Azospirillum on cereal crops [5].

Recently, to elucidate the molecular mechanism that regulates the interaction of this bacterium with plants, the root development of Arabidopsis thaliana was investigated. It is crucial pointing that primary root growth is due to both root meristem cell division and cell elongation [6]. It was observed a reduction in the primary root length, an increase in the lateral root number and root hairs, as well as an elevation in the internal auxin levels [7,8]. This same phenotype was also observed when exposing the plant to high auxin concentrations [9]. In the Azospirillum-Arabidopsis interaction reported by Spaepen et al. [7], they evaluated the effect of the auxins produced by the bacteria when inoculating A. thaliana with two strains of A. brasilense Sp245: a wild-type strain and a mutant in auxin biosynthesis (FAJ009). The inoculation with the wild-type strain caused inhibition of primary root growth and an increase in the number of lateral roots and length of root hairs. The mutant strain did not alter the root architecture of the plant. These results allowed them to suggest that the auxins produced by the bacteria could be involved in the morphological changes of the root architecture.

Fine-tuning control of auxin homeostasis and time-space distribution is crucial to promoting growth. This is because suboptimal concentrations of auxins cannot elicit the desired physiological responses, and high concentrations can be growth repressing. Thus, auxin biosynthesis, transport, signaling, and degradation, are critical factors for sensing biotic and abiotic stimuli within cells and tissues [10]. For the plant-Azospirillum interaction, bacterially-produced auxins could be involved in alterations of root architecture, such as the programmed lateral root formation. Nevertheless, little information has been generated to elucidate the molecular mechanism behind this important agronomical trait. The present study aimed to uncover the genetic component of the Arabidopsis response pathway to auxins potentially involved in the root response to A. brasilense. Novel evidence was gathered that the overall bacterium increases internal auxin levels, changes the root system development, and promotes lateral root primordia initiation. We also tested how the presence of this bacterium modulated the root architecture of several Arabidopsis mutants by altering the auxin response pathway.

2.1 Disinfection, Sowing, and Incubation of Seeds

The seeds of the wild-type Ecotypes Columbia (Col-0), or Landsberg Erecta (Ler), transgenic lines DR5::uidA [11], CycB1::uidA [12] and EXP7::uidA [13], as well as the mutants in auxin synthesis yuc2 yuc6+/− [14]; auxin carriers aux1-7+/− [15], pin1+/− [16], pin2+/− [17], pin3+/− [18], pgp1−/− [19], pgp4 −/− [20], pgp19−/− [21], axr4-1+/− [22], ben2+/− [23]; the auxin signaling axr1-3−/− [24], slr1+/− [25], arf7 arf19−/− [26], the mutant tt4+/− [27] and the line 35S::YUC4 DR5::uidA [28] were all disinfected with a 5% chlorine 1% SDS solution and stratified at 4°C for 48 h [29]. Subsequently, the seeds were sown in Petri dishes containing 0.2× Murashige and Skoog (MS) culture medium, 0.5% sucrose, 0.8% agar and 200 μL/L of a vitamin solution (thiamine 1 mg/mL, pyridoxine 5 mg/mL and nicotinic acid 5 mg/mL) and incubated in a vertical position for 5 days in a plant growth chamber (Percival Scientific AR-95L, Parry, IA, USA). The photoperiod was 16 h light/8 h dark at 22°C, and light intensity was 100 µmol m−2 s−1.

2.2 Preparation of Culture Medium

The Murashige-Skoog (MS) culture medium (Phytotechnology Laboratories) was prepared by dissolving in distilled water the amount of salts corresponding to the 0.2× concentration and 0.5% of sucrose. After adjusting the pH to 5.7, 0.8% agar was added. After that, 200 μL/L of a vitamin solution was added to the warm medium previously sterilized at 121°C for 20 min. All reagents used came from the Sigma brand unless otherwise specified.

2.3 Preparation of Culture Medium for Maintenance and Inoculation of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245

The bacteria were kept in Luria-Bartani (LB)-tetracycline culture medium (10 g/L peptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl, 0.186 g/L MgSO4, 0.2775 g/L CaCl2, 1 g/L agar and 10 µg/mL tetracycline) at 4°C, they were reseeded every 10 days in Petri dishes with LB-tetracycline medium, and incubated overnight at 37°C. Then the bacterium was incubated for 16 h at 37°C. Afterwards, an aliquot of bacteria was taken from this plate and resuspended in 1 mL of sterile distilled water to reach absorbances of 0.9, equivalent to 1 × 108 CFU/mL or 2.5 × 105 CFU. The 0.2× MS medium included 0.5% sucrose and 0.8% agar.

2.4 Transfer of Seedlings to Culture Media Supplemented with Azospirillum brasilense Sp245

Five-day-old seedlings were transferred to Petri dishes containing 0.2 × MS medium with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum or without the bacterium. The seeded Petri dishes were incubated for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 9 days in the plant growth chamber under the conditions as mentioned above.

2.5 Histochemical Activity of uidA

Transgenic seedlings expressing DR5::uidA, CycB1::uidA and EXP7::uidA were exposed to the bacterium for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 9 days. The seedlings were placed in microtiter boxes and incubated in a solution of X-Gluc (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D glucuronide) (Phytotechnology Laboratories) (1 mM in a phosphate buffer) (NaH2PO4 and 0.1 M Na2HPO4 pH 7) adding 2 mM of K4Fe (CN)6 and K3Fe (CN)6, at 37°C for 16 h. The seedlings were then incubated in an acid solution (0.24 N HCl and 20% methanol) for 80 min at 60°C, transferred into in a basic solution (7% NaOH and 60% EtOH) for 40 min at room temperature and dehydrated with 40%, 20% and 10% ethanol solutions for 15 min [30]. Finally, 50% glycerol was added and the seedlings were incubated overnight. The seedlings were mounted on slides and observed under the microscope with a 10× objective; photographs of the primary and lateral roots were taken.

2.6 Evaluation of Root Architecture of Seedlings

To evaluate the effect of Azospirillum on root architecture, five-day-old Wt seedlings were transferred to culture media without and supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of A. brasilense and incubated for 1, 3 and 6 days. The parameters of root architecture were determined: Primary Root Length (PRL), Lateral Root Number (LRN) and Lateral Root Density (LRD). The PRL was measured with a ruler (cm), the LRN was obtained by counting the roots emerging from the primary root under a stereomicroscope (Iroscope ES-24 Leica) with a 4× objective, and the LRD was obtained by calculating the ratio between LRN, and PRL [31].

All the experiments were carried out at least three times independently, taking 25 seedlings per treatment as a representative sample. Statistical analysis was applied to the data obtained, with the Statistic 8.0 program, and the data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA. When F tests were significant, differences among means were tested using the post hoc Tukey test with a statistical significance of P < 0.05.

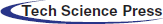

3.1 Azospirillum Modifies Arabidopsis Root Architecture

In this study, the changes in the Arabidopsis root system during short times of exposure to the bacteria were analyzed. Azospirillum inhibited the growth of the primary root throughout all the incubation times (Fig. 1A), while the lateral root number increased markedly after three and six days of exposure to the bacteria (Fig. 1B); the lateral root density increased twenty-five times (Fig. 1C). Representative images of seedlings clearly show that Azospirillum induced a reprogramming of the root architecture from the third day of exposure to the bacteria (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1: Effect of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 on Arabidopsis root architecture. (A) Primary root length. (B) Lateral root number. (C) Lateral root density. (D) Representative photographs of the Wt seedlings on the control medium and inoculated with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum. The values shown represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error (n = 3). Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between treatments on any study variable at P < 0.05

3.2 Azospirillum Regulates Proliferation and Elongation of Primary Root and Stimulates Lateral Root Development

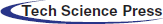

To determine which process would be affected in the arrest of primary root growth in the presence of Azospirillum (Fig. 1A), cell division was first analyzed. For this, the line CycB1::uidA was used, which expresses this gene in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. It was observed that from the third day of exposure, the marker CycB1::uidA disappeared from the primary root meristem, being detected only in the lateral root meristems (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 modifies the CycB1::uidA expression in the Arabidopsis root. Arabidopsis CycB1::uidA seedlings were transferred to a control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media, and incubated for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 9 days. At the end of the incubation time, the seedlings were treated with X-Gluc, followed by a clearing process. The seedlings were mounted on slides, and microscopic observations were made at 10× magnification. Representative photographs of the roots from the seedlings in the control medium and those inoculated with Azospirillum (of at least 25 seedlings from three different trials with similar results) are shown

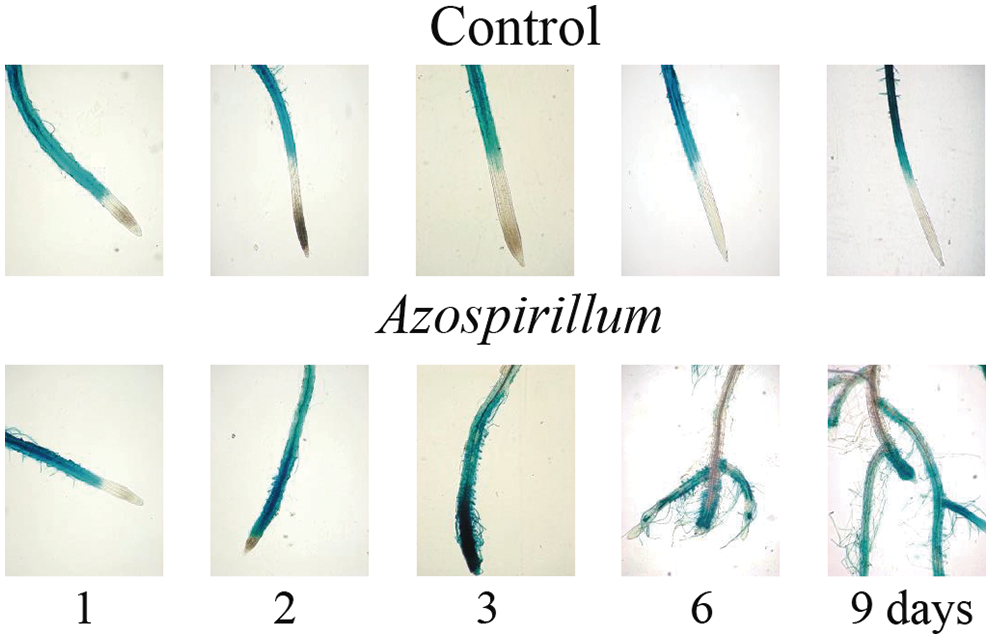

On the other hand, to assess the effect of the bacteria on cell elongation, the behavior of Exp7::uidA on seedlings, which specifically marks the differentiation zone from any primary root was analyzed [13]. In Fig. 3, we show that Exp7::uidA expression extended towards the root tip and the strength in the elongation zone decreased. Together these results showed that Azospirillum repressed primary root growth, inhibiting both cell division and elongation, thus promoting cell differentiation at very short exposure times to the bacteria.

Figure 3: EXP7::uidA expression in Arabidopsis roots in the presence of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245. EXP7::uidA seedlings were transferred to a control media and those supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum, and incubated for 1, 2, 3, 6 and 9 days. At the end of the incubation time, the seedlings were treated with X-Gluc, followed by a clearing process. The seedlings were mounted on microscope slides and observations were made at 10× magnification. Representative photographs of seedling roots in control medium or incubated with Azospirillum media of at least 25 seedlings from three different trials with similar results are shown

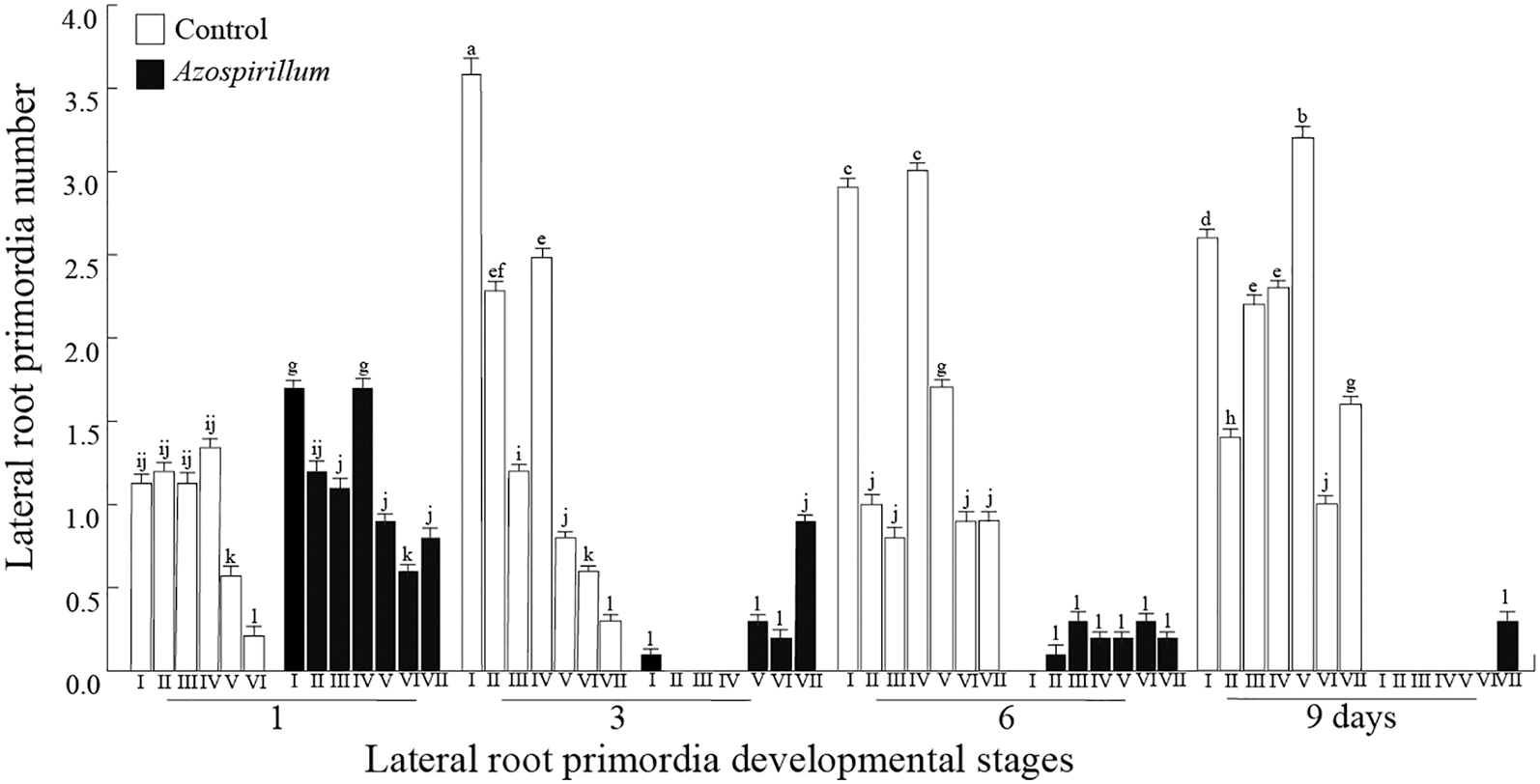

Then, the effect of A. brasilense in stimulating the initiation and/or maturation of lateral roots was analyzed. The number of the lateral root primordia (LRP) was assessed at different developmental morphology stages, which are summarized below: I. The first evidence of LRP initiation is the appearance of closely spaced cell walls in the pericycle layer in perpendicular orientation to the root axis. II. A periclinal division occurs that divides the LRP into two layers outer layer (OL) and inner layer (IL). Hence, as the OL and IL cells expand radially the domed shape of the LRP begins to appear. III. The OL divides periclinally, generating a three layer primordium. This further emphasizes the domed shape of the LRP. IV. The IL divides periclinally, creating a total of four cell layers. At this stage the LRP has penetrated the parent endodermal layer. V. A central cell in OL1 and OL2 divides anticlinally to form four small cuboidal cells. The cells adjacent to these two cells in the OL1 and OL2 also divide, creating an outer layer that contains 10–12 cells. The LRP at this stage is midway through the parent cortex. VI. This stage is characterized by several periclinal division. The LRP has passed through the parent cortex layer and has penetrated the epidermis. VII. It appears that many of the cells of the LRP continue to undergo anticlinal divisions. The LRP appears to be just about to emerge from the parent root [32]. DR5::uidA seedlings were used to facilitate the analysis of these structures. The quantification of lateral root primordia showed, that Azospirillum promoted both the initiation (stage I) and maturation (stages IV, V, VI, and VII) of the primordia. Later on, the number of lateral root primordia on the Azospirillum samples increased towards stage VII when was compared to the axenic seedlings, where lateral root primordia were at the earliest developmental stages (Fig. 4). These results showed that at very short exposure times, the bacteria promoted lateral root development.

Figure 4: Lateral root primordia of Arabidopsis in the presence of Azospirillum. DR5::uidA seedlings were transferred to control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media, where they were incubated for 1, 3, 6 and 9 days. On each day of exposure to the bacteria, the number of root primordia at different development stages were counted. The values represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Different letters above the histograms indicate significant differences between treatments within each day of the study

3.3 Azospirillum Stimulates Auxin Transport in Root System of Arabidopsis

The halted primary root growth in the presence of Azospirillum can be attributed to an accumulation of auxins at the root tip or to a decrease of auxins. To discern between these two possibilities, Arabidopsis DR5::uidA seedlings were used. As can be seen in Fig. 5, on day three of interaction, the level of auxins increased in primary root vascular tissue, particularly in the differentiation zone of lateral roots; this effect intensified by day fourth of exposition. The results showed that the maximum of auxins in the primary root meristem disappear from the fifth day of interaction with the bacteria, while the auxins accumulated in the vascular tissue were redistributed to lateral root meristems (Fig. 5B). Thus, the arrest of primary root growth was due, among other factors, to the disappearance of the maximum amount of auxins at the root tip.

Figure 5: Effect of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 on auxin levels in roots of A. thaliana. DR5::uidA seedlings were transferred to control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media. These media were incubated for 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 9 days. At the end of the incubation time, the seedlings were treated with X-Gluc, followed by a clearing process. The seedlings were mounted on slides and microscopic observations were made: (A) with 4× magnification and (B) 10×. Representative photographs of the roots from the seedlings in the control medium and that inoculated with Azospirillum of at least 25 seedlings from three different trials with similar results are shown

According to the changes observed in the auxin levels in the primary root and its distribution to lateral roots in Arabidopsis when interacting with Azospirillum (Fig. 5), its polar transport (PAT) could be modulated. As N-1-naphthylthalamic acid (NPA) is a specific inhibitor of PAT [33] and has been widely used as a valuable tool in plant development research, we evaluated the effect of NPA on changes in root architecture in presence of the bacteria. For this, Wt seedlings were transferred to culture media with 1 µM NPA to assess the interaction with Azospirillum. Subsequently, the material was incubated for 3, 6 and 9 days under the aforementioned conditions. The Wt seedlings grown in the presence of Azospirillum and Azospirillum plus NPA, had a decrease in root length of 70% at different times of exposure (Fig. 6A). The lateral root number in the presence of Azospirillum and NPA increased in a lesser proportion than on seedlings treated only with the bacterium (Fig. 6B). These results show that PAT inhibition prevents the stimulation of lateral root formation by the bacteria.

Figure 6: Effect of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 on root architecture of Arabidopsis in the presence of NPA. Arabidopsis Wt seedlings were transferred to control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media, added both media with NPA (1 µM) and incubated for 3, 6 and 9 days. (A) Primary root length. (B) Lateral root number. (C) Lateral root density. (D) Representative photographs of the seedlings are shown. The values represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error. Different letters above the histograms indicate statistically significant differences between treatments using the Tukey test (P < 0.05). The experiments were repeated three times with similar results

Then, the effect of the bacterium in root architecture on tt4 mutant seedling that shows an increase in PAT was analyzed. As can be seen in Fig. 7, Arabidopsis Ler and tt4 seedlings, A. brasilense arrested the growth of the root from the first day of exposure. On the other hand, the bacteria increased lateral root formation in the tt4 seedlings from the third day in a more significant proportion than in the Wt (Ler) line. It should be noted that the primary root of control tt4 seedlings showed the loss of gravitropism, which was reversed in seedlings exposed to A. brasilense. Thus, this contrasting effect between PAT inhibition with NPA and PAT increase in tt4 seedlings on root branching of Arabidopsis in the presence of Azospirillum suggests the participation of PAT in this plant-microbe interaction.

Figure 7: Effect of Azospirillum on root architecture of tt4 seedlings. tt4 seedlings were transferred to control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media and incubated for 1, 3 and 6 days. (A) Primary root length. (B) Lateral root number. (C) Lateral root density. The values shown represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error (n = 3). Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between treatments on any study variable at P < 0.05

3.4 Elements of the Auxin Response Pathway are Involved in the Effect of Azospirillum on Root Architecture of Arabidopsis

To identify genetic elements potentially involved in readjustments of the root system already influenced by A. brasilense, growth parameters in Arabidopsis Wt; and yuc2 yuc6, aux1-7, pin1, pin2 and pin3, axr1-3, slr1, and arf7 arf19 mutants were evaluated. In all mutants analyzed as in Wt line, a 70% decrease in root length was observed in the presence of the bacterium (Fig. 8A). Regarding the stimulation of root branching with Azospirillum, in the slr1 and arf7 arf19 mutant seedlings, the bacterium was unable to induce the formation of these structures, while in the other mutants; there was an increase comparable to Wt line (Figs. 8B and 8C).

Figure 8: Effect of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 on root architecture in Arabidopsis mutants in auxin synthesis, transport, and signaling. Arabidopsis mutants were transferred to control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media and incubated for 9 days. (A) Primary root growth based on the values of the control treatment relative to 100. (B) Lateral root number. (C) Lateral root number based on the values of the control treatment relative to 100. The values shown represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error (n = 3). Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between treatments on any study variable at P < 0.05

Next, we analyzed the effect of Azospirillum on mutants of other types of auxin efflux carriers such as the PGP/MDR/ABCB proteins (P-glycoprotein/multi-drug resistance/ATP-binding cassette B) [33]. For this, pgp1, pgp4, and pgp19 mutant seedlings were supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum and incubated for 9 days under the conditions as mentioned above. As can be seen in Fig. 9, in the mutants pgp1, pgp4 and pgp19 seedlings, there was a decrease in root length of around 78% and an increase in root branching in lines pgp4, and pgp19 comparable to the Wt line. Interestingly, only the pgp1 mutant did not show an increase in root branching (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9: Effect of Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 on root architecture of pgp1, pgp4, and pgp19 seedlings. Arabidopsis seedlings Wt, pgp1, pgp4, and pgp19 were transferred to control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media and incubated for 9 days. (A) Primary root length. (B) Lateral root number. (C) Lateral root density. (D) Representative photographs of the seedlings are shown. The values shown represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error (n = 3). Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between treatments on any study variable at P < 0.05

Furthermore, the AXR4-1 and BEN proteins have been reported to aid in positioning of AUX/LAX and PIN carriers, respectively [22,23]. The axr4-1 and ben2 seedlings exposed to A. brasilense showed a decrease in root length equal to Wt, while the bacteria did not stimulate the root branching in axr4-1 and ben2 seedlings (Fig. 10). The above results suggest that PGP1, AXR4-1, and BEN2 participate in the PAT regulation, allowing Azospirillum to stimulate the root branching in Arabidopsis seedlings.

Figure 10: Effect of Azospirillum brasilense on root architecture of axr4-1 and ben2 seedlings. Mutants seedlings were transferred to control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media and incubated for 9 days. (A) Primary root length. (B) Lateral root number. (C) Lateral root density. (D) Representative photographs of the seedlings in control medium and inoculated with A. brasilense. The values shown represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error (n = 3). Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between treatments on any study variable at P < 0.05

3.5 Effect of Azospirillum on Root Architecture of 35S::YUC4 DR5::uidA and yuc2 yuc6 Seedlings

To assess the effect of A. brasilense on root architecture of A. thaliana seedlings with different levels of endogenous IAA, we evaluate the response of 35S::YUC4 DR5::uidA line (which overproduces auxins) at 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of A. brasilense. In Fig. 11A it can be seen that after three days of exposure, the bacteria arrested root growth in the same way as in Wt seedlings, while the root branching increased by 165% and 110% on the third and sixth day of the interaction (Fig. 11B). In the meantime, the double mutant yuc2 yuc6 seedlings exposed to A. brasilense, showed a reduction in the root length similar to control, and an increase in the root branching of 200% and 600% on the third and sixth days, respectively (Figs. 11A and 11B).

Figure 11: Effect of Azospirillum on root architecture of 35S::YUC4 DR5::uidA and yuc2 yuc6 seedlings. 35S::YUC4 DR5::uidA and yuc2 yuc6 seedlings were transferred to control or supplemented with 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media and incubated for 1, 3 and 6 days. (A) Primary root length. (B) Lateral root number. (C) Lateral root density. The values shown represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error (n = 3). Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between treatments on any study variable at P < 0.05

Both lines showed an increase in the root branching; however that effect was more significant in double mutant yuc2 yuc6 than in the 35S::YUC4 line.

3.6 Effect of Yucasin on Root Architecture of DR5::uidA Seedlings Exposed to Azospirillum

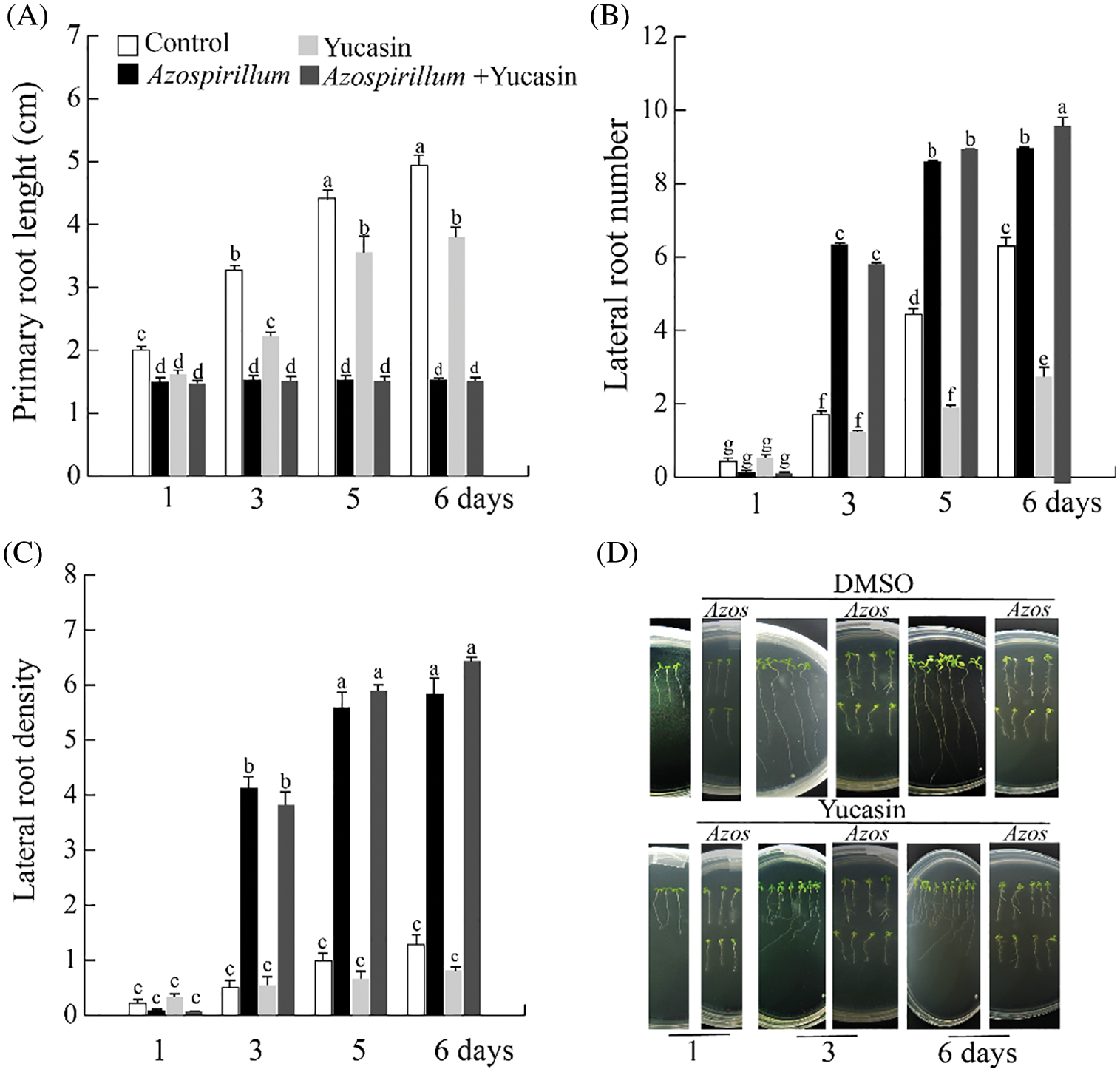

The five-day-old seedlings were transferred to culture media supplemented with 100 µM of yucasin and 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL. The plants were incubated for one, three, five, and six days of exposure to yucasin and the bacteria; at the end of these times, the radicular architecture parameters were evaluated. The results showed that A. brasilense and yucasin together reduce the root length and increase the root branching in the same proportion as the treatment only with the bacteria (Figs. 12A and 12B), which suggests that the effect on radicular architecture of Arabidopsis exposed to the bacteria is dependent of bacterial auxins and not because the stimulation of endogenous auxin synthesis. In Fig. 12D, it can be observed that seedlings in the presence of yucasin are agravitropic, while in those exposed to the bacteria; the agravitropism is lost due to bacterial IAA.

Figure 12: Effect of yucasin on root architecture of Arabidopsis Wt seedlings exposed to Azospirillum. The seedlings were transferred to control or supplemented with 100 µM yucasin and 2.5 × 105 CFU/mL of Azospirillum media and incubated for 1, 3, 5 and 6 days. (A) Primary root length. (B) Lateral root number. (C) Lateral root density. (D) Representative photographs of the seedlings exposed for 1, 3 and 6 days to Azospirillum and yucasin. The values shown represent the average of 25 seedlings +/− standard error (n = 3). Different letters above columns indicate significant differences between treatments on any study variable at P < 0.05

The first reports of the effect of Azospirillum on wheat and Arabidopsis showed that the bacteria decreased the length of the root and increased the root branching when the plants interacted with Azospirillum for six and seven days [7,8,34–36]. It seemed to us that this time was too long and that the observed effect was the result of changes occurring at shorter times. So, we decided to evaluate what happened at shorter interaction times. Surprisingly, we found dramatic changes on the first day of exposure to the bacteria, such as the arrest of the growth of the primary root, whose length is maintained throughout the experiment (Fig. 1A), and stimulation of maturation of the lateral root primordia (Fig. 4). After three days of exposure of Arabidopsis to Azospirillum, the observed changes were very noticeable in an increase of lateral root number (Fig. 1B), the arrest of the cell cycle in the meristem of the primary root (Fig. 2) and disappearance of the elongation zone of primary root (Fig. 3). The aforementioned data clearly indicate that the effect of bacteria on Arabidopsis root architecture development begins from early times of exposure.

Upon detailed revision of the literature on the effect of PGPR in different plants, none of these interactions has reported that the arrest of primary root growth is affected by the two events that determine the development of this organ [2,7,37–39], as it happens during interaction with Azospirillum. In addition, the bacteria caused a depletion of root meristem of primary root after three days of exposure. Regarding the stimulation of Azospirillum on lateral root development, our results show that it begins on the first day when the bacteria stimulated the induction and maturation of lateral root primordia (Fig. 4). It has been widely reported that Azospirillum brasilense alters the root architecture of a large number of plants and this effect has been attributed to the auxins it produces [1–3,7,8,34–36]. In the Azospirillum-Arabidopsis interaction reported by Spaepen et al. [7], they evaluated the effect of the auxins produced by the bacteria, when inoculating A. thaliana with two strains of A. brasilense Sp245: one wild-type and the other mutant in auxin biosynthesis (FAJ009). Their results allowed them to suggest that the auxins produced by the bacteria could be involved in the morphological changes of the root architecture. The authors also analyzed gene expression by microarrays of Arabidopsis roots exposed for three and seven days to Azospirillum. They observed that the bacterium induced changes in the expression of genes related to defense and the synthesis of cell wall components and that these were more pronounced at seven days of interaction. Regarding the expression of genes related to the auxin response pathway, they only observed an increase in the expression of a family of GH3 genes, so this analysis did not allow them to propose a mechanism by which auxins could be involved in the changes in the root system. Our results on the auxin levels in Arabidopsis seedlings exposed to Azospirillum indicate that auxins begin to increase after three days of exposure in primary root, specifically in the differentiation zone of the lateral roots, reaching a maximum in the same zone one day later. Subsequently, auxins showed to be distributed to meristems of the lateral roots and from the fifth day on, auxins disappeared from the root meristem of the primary root (Fig. 5).

Since auxins appear to be involved in the effect of Azospirillum on root architecture development, we decided to investigate what elements of the auxin response pathway might be participating in the outcome. For this, we analyzed the effect of the inoculation of the bacteria on the root architecture of several mutant lines of this pathway such as: yuc2 yuc6, aux1-7, pin1, pin2 and pin3, axr1-3, slr1, and arf7 arf19 mutants, affected in the genes that code for proteins that participate in the synthesis, transport, repressors and transcription factors of auxin response pathway [10]. However, we did not observe differences in the parameters of the root architecture of the mutants with respect to the control (Fig. 8). This was unexpected, especially in the auxin carrier mutants, since our results with the DR5::uidA line indicated that auxins increased in the vascular bundle at short exposure times and were eventually mobilized to the meristems of lateral roots (Fig. 5). To directly analyze the participation of PAT during the Azospirillum-Arabidopsis interaction, we used the PAT inhibitor, NPA [40]. On the other hand, flavonoids are known to affect expression, location of PIN efflux carriers [41–43] and the PIN transport cycle in endosomal vesicles [44]. Furthermore, flavonoids also modify the activity of ABCB-like auxins transporters and modulate the root gravitropism [33]. Thus, in the present study, was analyzed the effect of A. brasilense on root architecture of Arabidopsis tt4 mutant seedlings with decreased levels of flavonoids [27]. The results of the experiments with NPA (Fig. 6) and with the tt4 mutant (Fig. 7) strongly suggested that PAT was one of the factors necessary to prompt Azospirillum-induced changes in root architecture. So, we decided to test the pgp1, pgp4, and pgp9 mutant lines of other auxin efflux carriers, and in this way, we were able to determine that the PGP1 carrier seemed to be involved in this effect (Fig. 9B).

It seems relevant to highlight that an atypical efflux carrier is involved in the mobilization of bacterial auxins, such as PGP1 (Fig. 9) and the AXR4-1 and BEN proteins (Fig. 10) that help the correct positioning of the AUX/LAX and PIN carriers respectively, and not the classic transporters or some other element of the auxin response pathway as it occurs in most interactions with other PGPR [37–39]. We think that perhaps, the root system, faced with an excess of bacterial auxins in the root, does not respond through the usual channels and makes use of other elements that participate in PAT. Therefore, we decided to investigate what happens during the Arabidopsis-Azospirillum interaction, in 35S::YUC4 seedlings that have an excess and a double mutant yuc2 yuc6 with a deficiency of endogenous auxins. The results in both lines showed an increase of root lateral (Fig. 11), being the effect greater in yuc2 yuc6 than in 35S::YUC4, which suggests that a plant with excess endogenous auxins has developed a molecular system that allows it to regulate an auxins excess.

The IAA is involved in all processes that regulate plant development. The tryptophan-dependent indolpyruvic acid (IPA) pathway is the main pathway by which A. thaliana synthesizes IAA [45]. In this pathway, tryptophan is converted to IPA by Trp aminotransferase, which, when it is oxidized by yucca becomes IAA. Yucasin is an inhibitor of yucca enzymes [45], so we analyzed the effect of yucasin on the root architecture of A. thaliana seedlings exposed to A. brasilense. Our results, suggests that the effect on the radicular architecture of Arabidopsis exposed to the bacteria dependent on bacterial auxins and not on the stimulation of endogenous auxins synthesis.

Novel evidence was gathered that bacterium A. brasilense increases internal auxin levels, changes the development root system and promotes the initiation and maturation of the lateral root primordia of A. thaliana.

Author Contributions: E. B.-P. and M. E. M.-R. conceived and designed the experiments. E. C.-F., J. A.-R., D. M. P.-S., M. F.-R. and G. F.-R. conducted experiments. E. B.-P. collected and analyzed the date. E. B.-P., M. E. M.-R. and G. F.-R. wrote the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Coordinación de la Investigación Científica UMSNH. E. C.-F. and J. A.-R. were fellows of CONACYT-México.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Dobbelaere, S., Vanderleyden, J., Okon, Y. (2003). Plant growth-promoting effects of diazotrophs in the rhizosphere. Journal Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 22(2), 107–149. DOI 10.1080/713610853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fibach-Paldi, S., Burdman, S., Okon, Y. (2012). Key physiological properties contributing to rhizosphere adaptation and plant growth promotion abilities of Azospirillum brasilense. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 326(2), 99–108. DOI 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02407.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Verbon, E. H., Liberman, L. M. (2016). Beneficial microbes affect endogenous mechanisms controlling root development. Trends in Plant Science, 21(3), 218–229. DOI 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.01.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Méndez-Gómez, M., Castro-Mercado, E., Peña-Uribe, C. A., Reyes-de la Cruz, H., López-Bucio, J. et al. (2020). Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 lipopolysaccharides induce target of rapamycin signaling and growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Plant Physiology, 253(6), 153270. DOI 10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bashan, Y., de-Bashan, L. E. (2010). How the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum promotes plant growth-a critical assessment. In: Sparks, D. L. (Ed.Advances in agronomy, pp. 2–315. USA: Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar]

6. Barrada, A., Montané, M. H., Robaglia, C., Menand, B. (2015). Spatial regulation of root growth: Placing the plant TOR pathway in a developmental perspective. International Journal of Molecular Science, 16(8), 19671–19697. DOI 10.3390/ijms160819671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Spaepen, S., Bossuyt, S., Engelen, K., Marchal, K., Vanderleyden, J. et al. (2014). Phenotypical and molecular responses of Arabidopsis thaliana roots as a result of inoculation with the auxin-producing bacterium Azospirillum brasilense. New Phytologist, 201(3), 850–861. DOI 10.1111/nph.12590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Méndez-Gómez, M., Castro-Mercado, E., Peña-Uribe, C. A., Reyes-de la Cruz, H., López-Bucio, J. et al. (2020). TARGET OF RAPAMYCIN signaling plays a role in Arabidopsis growth by Azospirillum brasilense Sp245. Plant Science, 293, 110416. DOI 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yoon, E. K., Kim, I. W., Yang, J. H., Kim, S. H., Lim, J. et al. (2014). A molecular framework for the differential response of primary and lateral roots to auxin in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Plant Biology, 57(5), 274–281. DOI 10.1007/s12374-013-0239-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Vanneste, S., Friml, J. (2009). Auxin: A trigger for change in plant development. Plant Cell, 136(6), 1005–1016. DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ulmasov, T., Murfett, J., Hagen, G., Guilfoyle, T. J. (1997). Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. Plant Cell, 9(11), 1963–1971. DOI 10.1105/tpc.9.11.1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Colón-Carmona, A., You, R., Haimovitch-Gal, T., Doerner, P. (1999). Technical advance: Spatio-temporal analysis of mitotic activity with a labile cyclin-GUS fusion protein. The Plant Journal, 20(4), 503–508. DOI 10.1046/j.1365-313x.19999.00620.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cho, H. T., Cosgrove, D. J. (2002). Regulation of root hair initiation and expansin gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 14(12), 3237–3253. DOI 10.1105/tpc.006437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cheng, Y., Dai, X., Zhao, Y. (2006). Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissue in Arabidopsis. Genes and Development, 20(13), 1790–1799. DOI 10.1101/gad.1415106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pickett, F. B., Wilson, A. K., Estelle, M. (1990). The aux1 mutation of Arabidopsis confers both auxin and ethylene resistance. Plant Physiology, 94(3), 1462–1466. DOI 10.1104/pp.94.3.1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Benková, E., Michniewicz, M., Sauer, M., Teichmann, T., Seifertová, D. et al. (2003). Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation. Cell, 115(5), 591–602. DOI 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00924-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xu, W., Jia, L., Baluška, F., Ding, G., Shi, W. et al. (2005). PIN2 is required for the adaptation of Arabidopsis roots to alkaline stress by modulating proton secretion. Journal of Experimental Botany, 63(17), 6105–6114. DOI 10.1093/jxb/ers259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Friml, J., Wiśniewska, J., Benková, E., Mendgen, K., Palme, K. (2002). Lateral relocation of auxin efflux regulator PIN3 mediates tropism in Arabidopsis. Nature, 415(6873), 806–809. DOI 10.1038/415806a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Geisler, M., Blakeslee, J. J., Bouchard, R., Lee, O. R., Vincenzetti, V. et al. (2005). Cellular efflux of auxin catalyzed by the Arabidopsis MDR/PGP transporter AtPGP1. The Plant Journal, 44(2), 179–194. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02519.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Terasaka, K., Blakeslee, J. J., Titapiwatanakun, B., Peer, W. A., Bandyopadhyay, B. et al. (2005). PGP4, an ATP binding cassette P-glycoprotein, catalyzes auxin transport in Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant Cell, 17(11), 2922–2939. DOI 10.1105/tpc.105.035816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Noh, B., Bandyopadhyay, A., Peer, W. A., Spalding, E. P., Murphy, A. S. (2003). Enhanced gravi- and phototropism in plant mdr mutants mislocalizing the auxin efflux protein PIN1. Nature, 423(6943), 999–1002. DOI 10.1038/nature01716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hobbie, L., Estelle, M. (1995). The axr4 auxin-resistant mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana define a gene important for root gravitropism and lateral root initiation. The Plant Journal, 7(2), 211–220. DOI 10.1046/j.1365-313x-1995.7020211.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Tanaka, H., Kitakura, S., Rakosová, H., Uemura, T., Feraru, M. I. et al. (2013). Cell polarity and pattering by PIN trafficking through early endosomal compartments in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genetics, 9(5), e1003540. DOI 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lincoln, C., Britton, J. H., Estelle, M. (1990). Growth and development of the axr1 mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 2(11), 1071–1080. DOI 10.1105/tpc.2.11.1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Fukaki, H., Tameda, S., Masuda, H., Tasaka, M. (2009). Lateral root formation is blocked by a gain-of-function mutation in the SOLITARY-ROOT/IAA14 gene of Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal, 29(2), 153–168. DOI 10.1046/j.0960-7412.2001.01201.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Okushima, Y., Fukaki, H., Onoda, M., Theologis, A., Tasaka, M. (2007). ARF7 and ARF19 regulate lateral root formation via direct activation of LBD/ASL genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 19(1), 118–130. DOI 10.1105/tpc.106.047761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Burbulis, I. E., Iacobucci, M., Shirley, B. W. (1996). A null mutation in the first enzyme of flavonoid biosynthesis does not affect male fertility in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 8(6), 1013–1025. DOI 10.1105/tpc.8.6.1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Munguía-Rodríguez, A. G., López-Bucio, J., Ruiz-Herrera, L. F., Ortiz-Castro, R., Guevara-García, A. A. et al. (2020). YUCCA4 overexpression modulates auxin biosynthesis and transport and influence plant growth and development via cross with abscisic acid in in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics and Molecular Biology, 43(1), e20190221. DOI 10.1590/1678-4685-gmb-2019-0221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kellermeier, F., Amtmann, A. (2013). Phenotyping jasmonate regulation of root growth. In: Goossen, A., Pauwels, L. (Eds.Jasmonate signaling, methods in molecular biology, pp. 25–32. New York, USA: Springer Science Business Media. [Google Scholar]

30. Jefferson, R. A., Kavanagh, T. A., Bevan, M. W. (1987). GUS fusions: Beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO Journal, 6(13), 3901–3907. DOI 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. López-Bucio, J., Hernández-Abreu, E., Sánchez-Calderon, L., Nieto-Jacobo, M. F., Simpson, J. et al. (2002). Phosphate availability alters architecture and cause changes in hormone sensitivity in Arabidopsis root system. Plant Physiology, 19(1), 244–256. DOI 10.1104/pp.010934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Malamy, J. E., Benfey, P. N. (1997). Organization and cell differentiation in lateral roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Development, 124(1), 33–36. DOI 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bailly, A., Sovero, V., Vincenzetti, V., Santelia, D., Bartnik, D. et al. (2008). Modulation of P-glycoproteins by auxin transport inhibitors is mediated by interaction with immunophilins. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283(31), 21817–21826. DOI 10.1074/jbc.M709655200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Spaepen, S., Vanderleyden, J., Okon, Y. (2009). Plant growth-promoting actions of rhizobacteria. Advances in Botanical Research, 51, 283–320. DOI 10.1016/s0065-2296(09)51007-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Méndez-Gómez, M., Barrera-Ortiz, S., Castro-Mercado, E., López-Bucio, J., García-Pineda, E. et al. (2021). The nature of the interaction Azospirillum-Arabidopsis determines the molecular and morphological change in root and plant growth promotion. Protoplasma, 258(1), 179–189. DOI 10.1007/s00709-020-01552-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dobbelaere, S., Croonenborghs, A., Thys, A., Broek, A. V., Vanderleyden, J. (1999). Phytostimulatory effect of Azospirillum brasilense wild type and mutant strains altered in IAA production on wheat. Plant and Soil, 212(2), 153–162. DOI 10.1023/A:1004658000815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Contesto, C., Milesi, S., Mantelin, S., Zancarini, A., Desbrosses, G. et al. (2010). The auxin-signaling pathway is required for the lateral root response of Arabidopsis to the rhizobacterium Phyllobacterium brassicacearum. Planta, 232(6), 1455–1470. DOI 10.1007/s00425-010-1264-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chamam, A., Sanguin, H., Bellvert, F., Meiffren, G., Comte, G. et al. (2013). Plant secondary metabolite profiling evidences strain-dependent effect in the Azospirillum-Oryza sativa association. Phytochemistry, 87(12), 65–77. DOI 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.11.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sukumar, P., Legue, V., Vayssieres, A., Martin, F., Tuskan, G. A. et al. (2013). Involvement of auxin pathways in modulating root architecture during beneficial plant-microorganism interactions. Plant Cell Environment, 36(5), 909–919. DOI 10.1111/pce.12036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Nagashima, A., Uehara, Y., Sakai, T. (2008). The ABC subfamily B auxin transporter AtABCB19 is involved in the inhibitory effects of N-1-naphthyphthalamic acid on the phototropic and gravitropic responses of Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Plant and Cell Physiology, 49(8), 1250–1255. DOI 10.1093/pcp/pcn092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Brown, D. E., Rashotte, A. M., Murphy, A. S., Normanly, J., Taque, B. W. et al. (2001). Flavonoids act as negative regulators of auxin transport in vivo in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology, 126(2), 524–535. DOI 10.1104/pp.126.2.524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Peer, W. A., Bandyopadhyay, A., Blakeslee, J. J., Makam, S. N., Chen, R. J. et al. (2004). Variation in expression and protein localization of the PIN family of auxin efflux facilitator proteins in flavonoid mutants with altered auxin transport in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell, 16(7), 1898–1911. DOI 10.1105/tpc.021501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Santelia, D., Henrichs, S., Vincenzetti, V., Sauer, M., Bigler, L. et al. (2008). Flavonoids redirect PIN-mediated polar auxin fluxes during root gravitropic responses. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283(45), 31218–31226. DOI 10.1074/jbc.M710122200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Geldner, N., Friml, J., Stierhof, Y. D., Jürgens, G., Palme, K. (2001). Auxin transport inhibitors block PIN1 cycling and vesicle trafficking. Nature, 413(6854), 425–428. DOI 10.1038/35096571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Nishimura, T., Hayashi, K., Suzuki, H., Gyohda, A., Takaoka, C. et al. (2013). Yucasin is a potent inhibitor of YUCCA, a key enzyme in auxin biosynthesis. The Plant Journal, 77(3), 352–366. DOI 10.1111/tpj.12399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |