International Journal of

Experimental Botany

| Phyton- International Journal of Experimental Botany |  |

DOI: 10.32604/phyton.2021.014962

ARTICLE

Soil Fungal Community Structure Changes in Response to Different Long-Term Fertilization Treatments in a Greenhouse Tomato Monocropping System

College of Resource and Environment, Qingdao Agricultural University, Qingdao, 266109, China

*Corresponding Author: Bin Liang. Email: liangbin306@163.com

Received: 11 November 2020; Accepted: 09 January 2021

Abstract: Greenhouse vegetable cultivation (GVC) is an example of intensive agriculture aiming to increase crop yields by extending cultivation seasons and intensifying agricultural input. Compared with cropland, studies on the effects of farming management regimes on soil microorganisms of the GVC system are rare, and our knowledge is limited. In the present study, we assessed the impacts of different long-term fertilization regimes on soil fungal community structure changes in a greenhouse that has been applied in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivation for 11 consecutive years. Results showed that, when taking the non-fertilizer treatment of CK as a benchmark, both treatments of Conventional chemical N (CN) and Organic amendment only (MNS) significantly decreased the fungal richness by 16%–17%, while the Conventional chemical N and straw management (CNS) restored soil biodiversity at the same level. Saprotroph and pathotroph were the major trophic modes, and the abundance of the pathotroph fungi in treatment of CNS was significantly lower than those in CK and CN soils. The CNS treatment has significantly altered the fungal composition of the consecutive cropping soils by reducing the pathogens, e.g., Trichothecium and Lecanicillium, and enriching the plant-beneficial, e.g., Schizothecium. The CNS treatment is of crucial importance for sustainable development of the GVC system.

Keywords: Continuous cropping; straw return; FUNGuild; biocontrol agent

Soil fungi are indispensable to soil quality. They are involved in various processes, e.g., nutrient cycling, organic matter (OM) decomposition, and toxin removal [1–3]. The group functions diversely. Some play important roles as plant symbionts, such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) [4,5]; some are biocontrol agents (e.g., Trichoderma spp.) [6]; and some are pathogens (e.g., Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium spp., etc.) [4,7].

Greenhouse vegetable cultivation (GVC) is a kind of intensifying agriculture aiming at increasing food production using more agricultural resources. As the largest operator, China has been the bellwether for nearly 50 years [8]. However, after long-time intensive management and consecutive cropping, soil fertility of the GVC system and crop yield decrease, while, soil-borne diseases aggravate [9,10]. Fungi were considered as the causative agent for plant disease [11]. Results have shown that, after consecutive cropping, fungal community structure shifted with beneficial fungi decreasing and the pathogenic increasing, which contributed to the continuous cropping obstacles [12–15].

Straw return is an effective practice to change soil microbial community structure in ago-ecosystems. Owing to its high content of organic C (about 50% or higher), straw incorporation increases the abundance of the C-related microflora by regulating soil organic C storage and compensating the loss of native soil C [16–18]. Also, fertilization can ameliorate soil microbial properties [19,20]. Compared to chemical fertilizers, organic fertilizers bring more benefits to soil microbial communities for it is more sustainable in nutrient releasing and the OM it contains offers various carbon resources and abundant substrates to microbial habitats [21,22].

Thanks to the high-throughput pyrosequencing, interpreting microbiome data and tracking the community changes in complex habitats turn to be feasible in light of differences in relative abundance [23]. Because of the ecological complexity of microbial communities, taxon with relative abundance above a certain threshold (e.g., 1%) was considered as the dominant that would be further selected as the research focus [24]. Reports concerning on the impacts of fertilization and straw return on soil microbial diversity and dominant microflora are numerous [25–29]. However, most of them are relevant to cropland, little is known about the GVC system with high temperature and high humidity environment that may affect OM decomposition [30,31]. Besides, compared with the studies on soil bacteria, relevant evaluations of the equally important soil fungi are scarce [32].

To make up the shortfall, soils of a greenhouse that have been used in tomato (S. lycopersicum L.) cultivation for 11 consecutive years (2004–2015) were subjected to pyrosequencing analysis. The aim of this study was (1) to have an accurate diagnosis about the fungal community composition after continuous cropping, and (2) to understand the effects of different fertilization practices on community structure in the GVC system.

The fertilization experiments were based in Shouguang City (36°55′N, 118°45′E), Shandong Province, China, where the climate is semi-humid. Texture of the soil in the 0–30 cm has been characterized as 46% sand, 52% silt, and 2% clay, and the soil type is Fluvo-aquic Ochri-Aquic Cambisols. The original soil had a pH value of 7.8, contents of OM and total N (TN) were 18.3 and 1.37 g kg-1, available N (AN), available P (AP) and available K (AK) were 112, 437 and 299 mg kg-1, respectively.

2.2 Tomato Cultivation and Management

The experiment was conducted in a plastic greenhouse established in 2002. Tomato cultivation and management were the same to that described in Liang et al. [33]. In brief, plants were cultivated twice a year, i.e., the winter-spring (WS) season and the autumn-winter (AW) season (corresponding growth periods were mid-February to mid-June, and early-August to the next January). Furrow irrigation (9–11 times each season with 60 mm of water each time), calcium superphosphate (12% P2O5, 300 kg P2O5 ha-1 season-1) and potassium sulfate (50% K2O, 400 kg K2O ha-1 season-1) as the P and K fertilizers were employed.

2.3 Description of the Long-Term Experiments

The different long-term fertilization experiments started from 2004. Twelve plots (1.6 × 1.2 m2 each) were established and divided into four different treatments. Each treatment were scattered randomly in three repetitive plots. The abbreviations and applications for each treatment were: the non-fertilizer treatment (CK) = no urea or straw applied; Conventional chemical N treatment (CN) = chicken manure + urea; Organic amendment only treatment (MNS) = chicken manure + pre-cut wheat straw; and Conventional chemical N and straw management (CNS) = chicken manure + urea + pre-cut wheat straw. All treatments (except CK) were first broadcast with air-dried chicken manure (10 t ha-1 season-1) as the base fertilizer, and incorporated into the top soil by ploughing. Urea (with the dosage of 120 kg N ha-1 time-1 and at least 6 times per season) was side-dressed in treatments of CN and CNS, and pre-cut wheat straw (3–5 cm in length) was applied at a concentration of 8 t ha-1 season-1 in MNS and CNS. For more detailed information about the long-term experiments, please consult in Zhang et al. [34].

After the harvest of tomato in the WS season of 2015, soils within the depth of 0–20 cm were collected with a 2 cm diameter soil auger using five-point sampling method, and pooled together to obtain a composite sample per plot. The representative samples were then passed through a 2 mm sieve, homogenized, and utilized for genomic DNA extraction using soil DNA kits (Omega Bio-Tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA).

The qualified DNA and the primer sets of 1737F (5’-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3’) and 2043R (5’-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3’) were employed to amplify the internal transcribed spacers (ITS) rRNA gene fragments [35]. The 20-μL PCR reaction mixture comprised of 4 μL 5x FastPfu Buffer, 2 μL 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.8 μL each primer, 0.4 μL FastPfu Polymerase and 10 ng Template DNA. The amplification was conducted using ABI GeneAmp® 9700 (ABI, Foster City, USA), and the procedure was: pre-degeneration at 95°C for 3 min, 33 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s and 72°C for 45 s, followed by the final elongation at 72°C for 10 min. Sequencing was performed using the GS FLX titanium platform (Roche GS FLX, Roche Life Sciences, USA). Processes for sample differencing and raw data filtering were the same to that described in [34,36,37]. The trimmed sequences were phylogenetically assigned according to their best matches to the sequences in the ITS reference database, Unite (http://unite.ut.ee/index.php) [38]. The operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were classified using a 97% identity threshold, and the phylogenetic affiliation was assigned using the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) classifier at a confidence level of 70%.

All data were examined for homogeneity of variance and were normally distributed. The α-diversity indices of the number of observed OTUs (Sobs), Shannon and Simpson were compared after resampling the read number of each sample to the same (30379 reads) in Mothur (version v.1.30.1 http://www.mothur.org/wiki/Schloss_SOP#Alpha_diversity). ANOVA was applied to compare the α-diversity indices and the relative abundances (RAs) of each taxon among treatments based on the Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test using SPSS v20.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). The β- diversity indices were evaluated by the PERMANOVA test on Bray-Curtis distance measures with the “vegan” package in R (version v. 2.4–4), and the Kruskal-Wallis test function was employed in the Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) to identify biomarkers that differed significantly (p < 0.05) with Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) score >3 [39]. Stack columns of the community composition were drawn by Origin 9.0, and heatmap of the genus was generated by Matlab (version R2014a). Main genera (with average RA>1% in either treatment) were selected to analyze the effects of urea (MNS vs. CNS) and straw (CN vs. CNS) with paired t-test. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the fungal communities based on the composing OTUs was conducted using Canoco 5.0 (Microcomputer Power, Ithaca, USA). FUNGuild: Taxonomic Function (http://www.stbates.org/guilds/app.php) was applied to explore the fungal functional group composition [40].

3.1 Diversity of Soil Fungal Communities

A total of 465,063 sequences were obtained after quality control. The sample sequence numbers ranged from 30,379 to 43,959 with an average length of 306 bp. A 3% dissimilarity threshold was used to classify the sequences into 1027 OTUs before taxonomy assignment. In each sample, 268–446 OTUs were obtained. There were 436 OTUs defined as “unclassified” owing to the inadequate development of the ITS reference database of Unite, which accounted for 28%, 9%, 6% and 21% of the total sequences detected in the CK, CN, MNS and CNS treatments.

Values of Sobs differed significantly among treatments, but there was no difference in either values of Shannon or Simpson. Taking CK treatment as a benchmark, CNS maintained a good biodiversity of fungi (the Sobs value was 419 vs. 415 in CK), but CN and MNS treatments significantly decreased the community richness by 16% and 17%, respectively (Tab. 1).

Table 1: The α- diversitya of fungal community

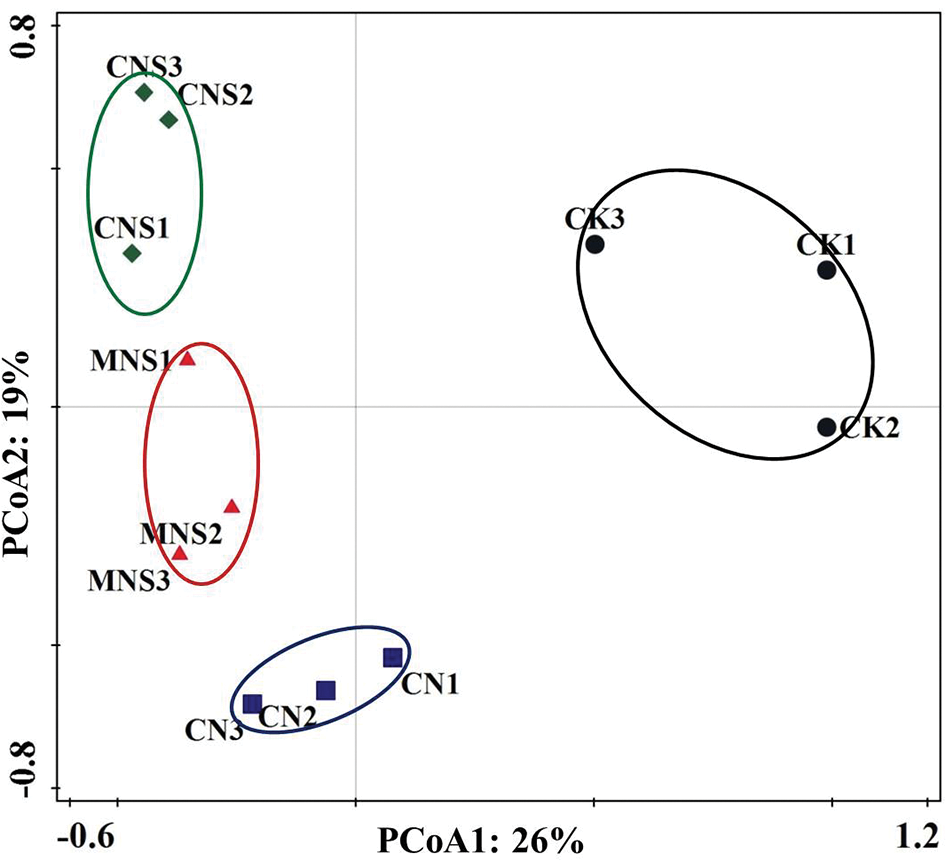

PCoA score plot based on the composing OTUs showed that the fungal community profiles of the three replicates for each treatment were with high reproducibility. Effects of fertilizers were the main factors (26% of contribution rate), separating CK on the positive side and other treatments on the negative side of the X-axis (Fig. 1). PERMANOVA test showed that the fungal community structures between CK and CNS soils were significantly different (R2 = 0.5001, p = 0.014, Appendix A).

Figure 1: PCoA score plot based on weighted UniFrac metrics to show overall structural changes of soil fungi. The three replicated plots of each treatment were represented by the number 1, 2 and 3, respectively

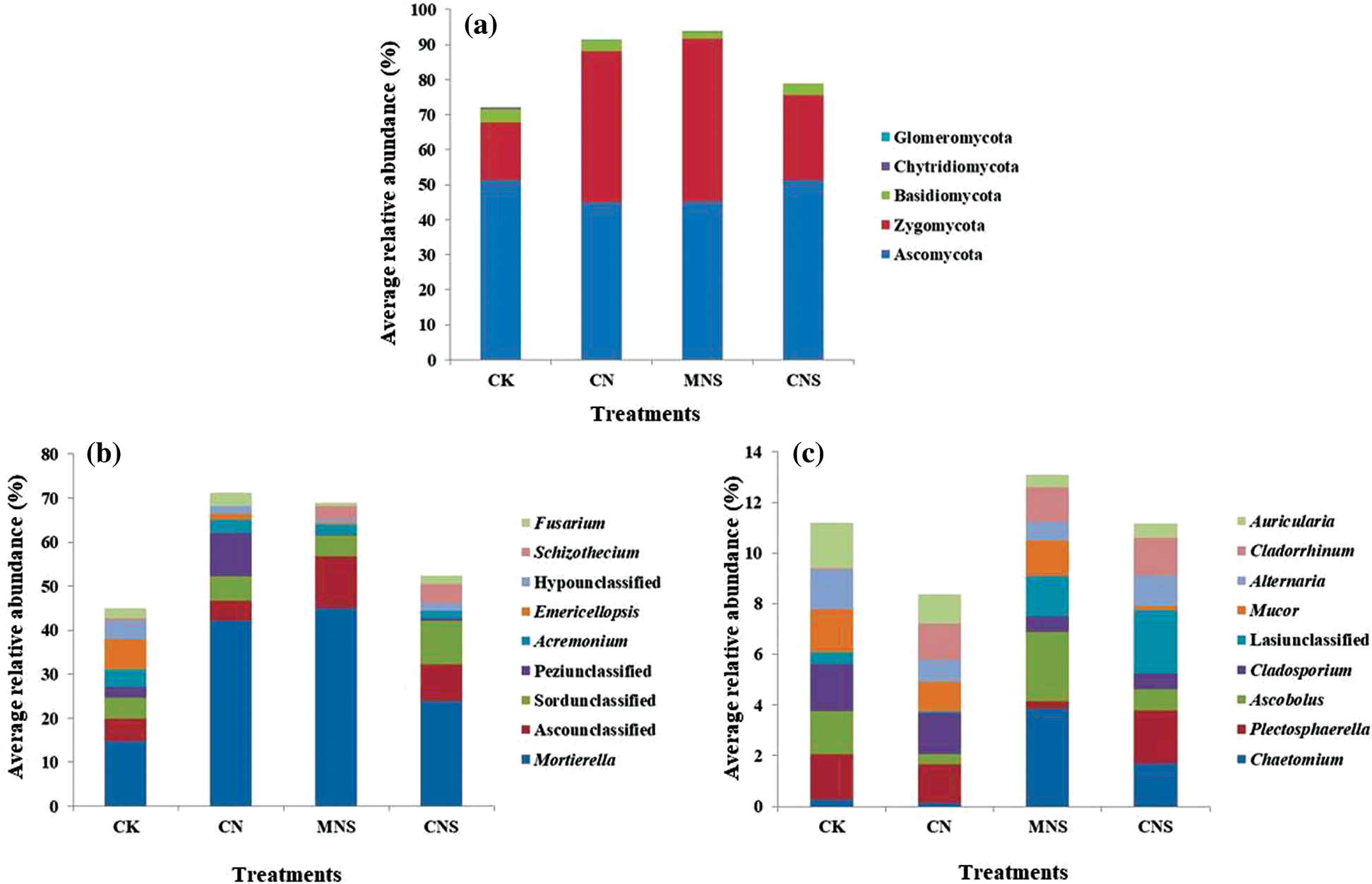

Figure 2: Fungal community structure at the levels of phylum (a) and genus (b, c). Taxons with average RA > 1% are listed. For more clarity, genera with average RA > 2% are shown in (b), and the rest (with average RA in the range of 1%–2%) are shown in (c)

3.2 Composition of Fungal Community

The retrieved and assigned sequences were classified into three main (with average RA > 1%) fungal phyla: Ascomycota (45%–51%), Zygomycota (17%–47%) and Basidiomycota (1.9%–3.8%, Fig. 2a). Corroborating previous studies conducted in agricultural ecosystems [41], Ascomycota was the dominant with Sordariomycetes (23%–33%) as the primary class, and Mortierella (15%–45%), Acremonium (1.6%–3.9%), Emericellopsis (0.3%–6.9%), Schizothecium (0.04%–4.5%) and Fusarium (0.8%–3.0%) as the predominant genera with average RA > 2% (Fig. 2b). Other main genera with average RA values ranging from 1% to 2% were listed in Fig. 2c. Schizothecium was detected with higher proportion in CNS soils (4%), while Acremonium, Emericellopsis and Fusarium were more abundant in CK soils. For example, the proportions of Acremonium and Emericellopsis in CK soils were 4% and 7%, respectively; while the corresponding ratio of the former was merely 2% and the latter was even undetectable in CNS soils.

3.3 Significantly Enriched Communities in Each Treatment

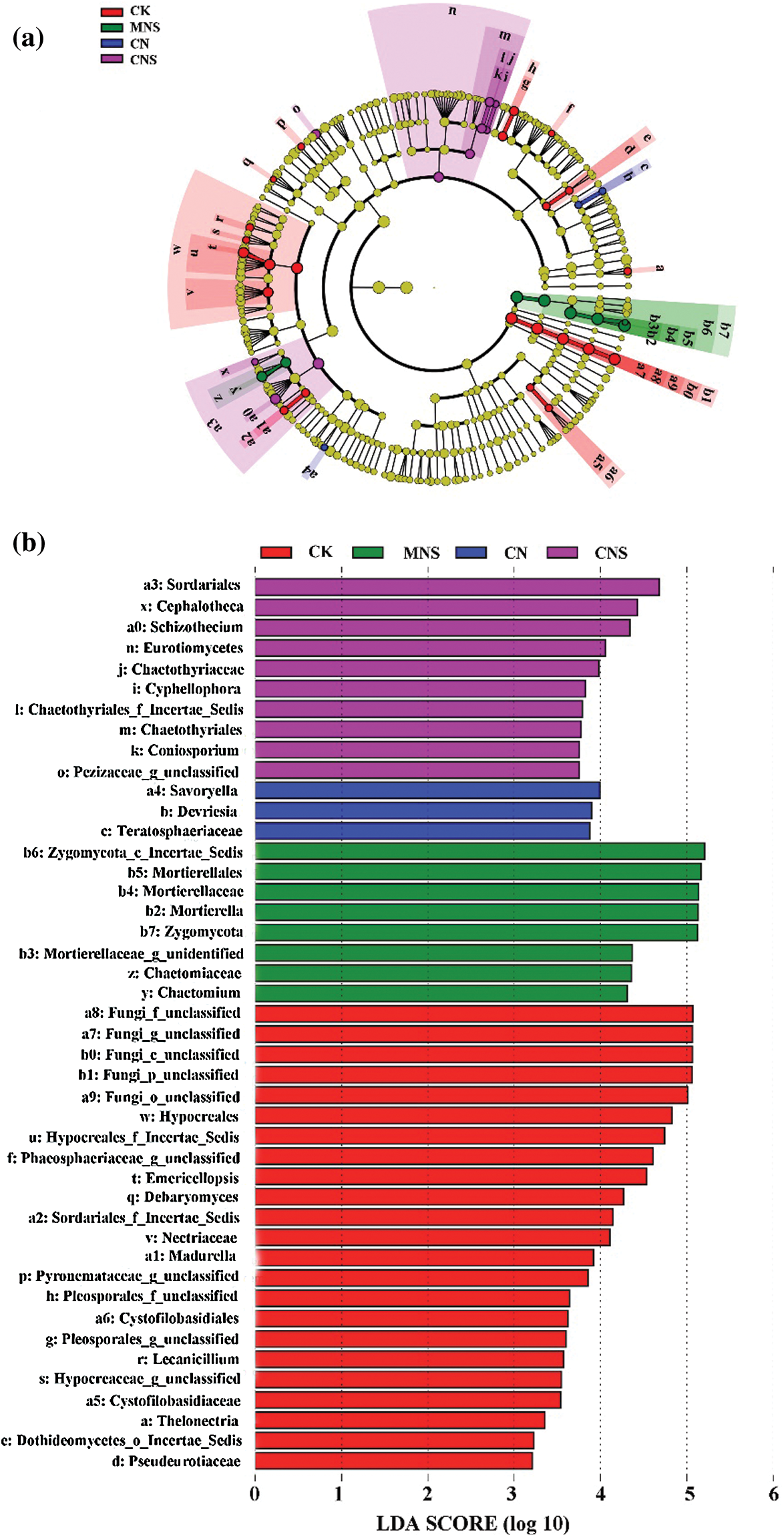

Following CK treatment, members of Hypocreales (i.e., Nectriaceae, Emericellopsis, and Lecanicillium) and Sordariales_Incertae_Sedis (e.g., Madurella) were enriched, while in CNS soils, members of Sordariales (i.e., Schizothecium and Cephalotheca), Chaetothyriales, and Pezizaceae were more abundant. In CN soils, Savoryella and the subordinate of Teratosphaeriaceae (i.e., Devriesia) were enriched. And in MNS soils, both the clades of Zygomycota (phylum to genus; Zygomycota_Incertae_Sedis, Mortierellales, Mortierellaceae, Mortierella) and Chaetomiaceae (family to genus; Chaetomium) were predominant (Figs. 3a and 3b).

Figure 3: Identification of the enrichment in each treatment. Cladogram showing the phylogenetic distribution of the predominant fungi (a) and LDA scores of the enriched (b). Circles denote clades from domain (the innermost) to genus (the outermost), and circle’s diameter is positively correlated with abundance

3.4 Composition of Functional Groups (Guilds)

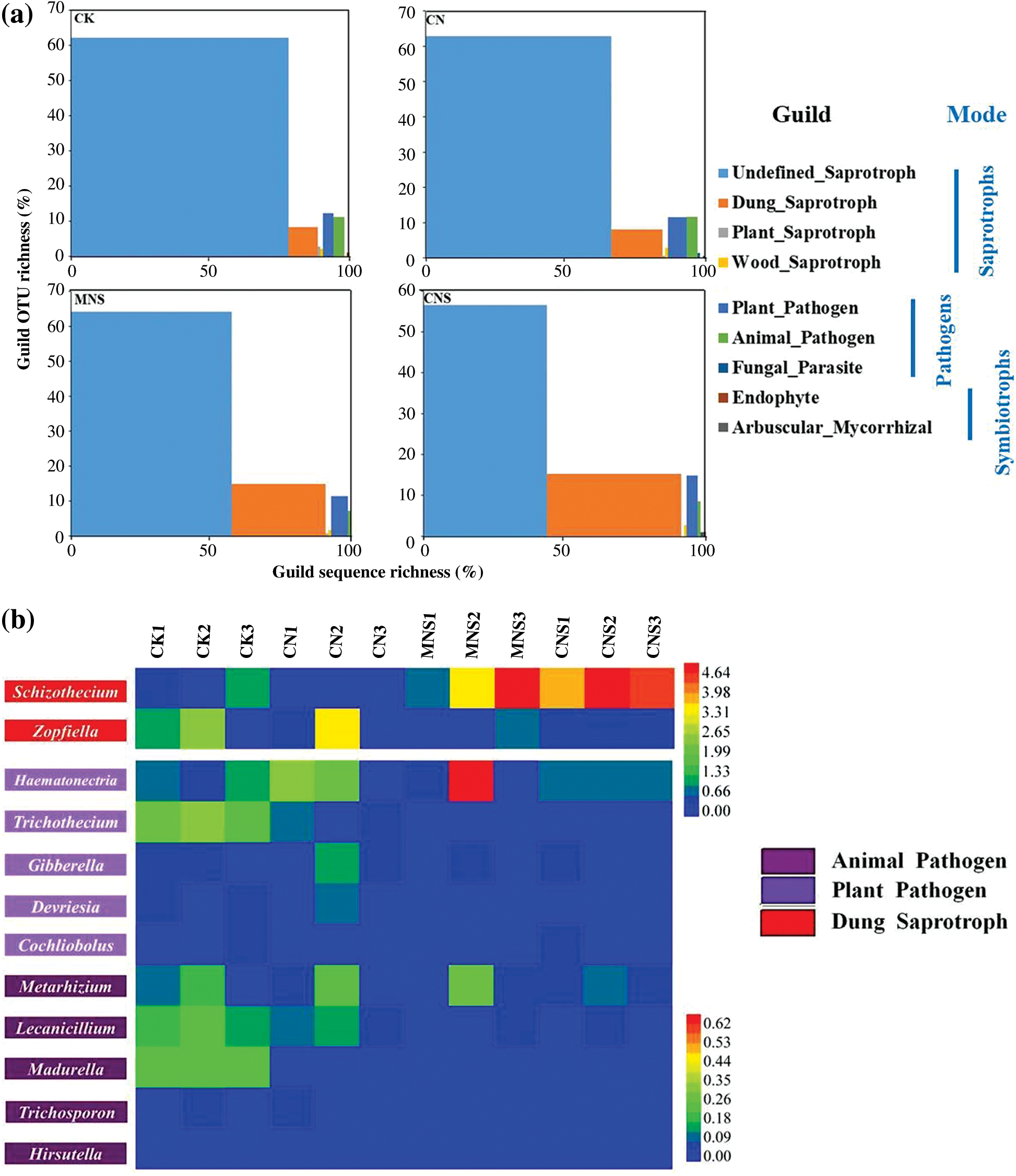

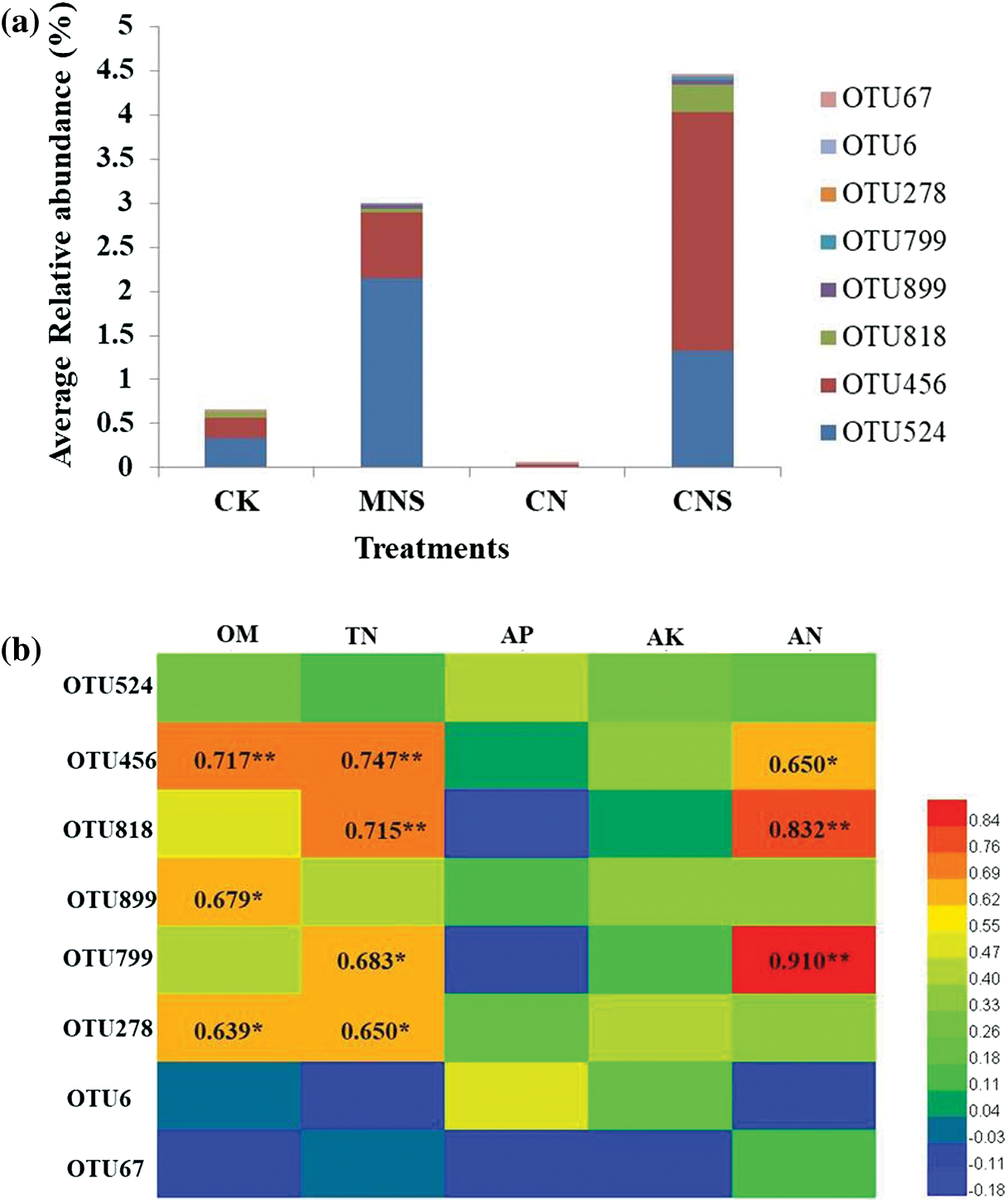

FUNGuild detected all the three trophic modes and nine guilds, of which saprotrophs and pathotrophs dominated after removing the unassigned OTUs. The proportions of the OTUs that could be predicted with a trophic mode ranged from 54% to 74% in all treatments; and when it concerned to mode with the confidence ranking of “probable” or “highly probable”, the sequence ratios decreased to 11%–21% (Appendix B). Although both OTU and sequence richness of guilds varied among treatments, the undefined saprotroph and dung saprotroph dominated. As to OTU richness, undefined saprotroph was the largest guild in all treatments. However, with regard to sequence richness, saprotrophs of the undefined only dominated with great advantages in soils of CK, CN and MNS. In the treatment of CNS, dung saprotroph (49%) outweighed the undefined (45%), and its sequence ratio was 1.4–4.2 times of that in other treatments (Fig. 4a). Schizothecium was the typical dung-dweller. Its abundance differed significantly between CNS (4.5%) and the treatments without straw applied, i.e., CK (0.65%) and CN (0.04%, Fig. 4b).

Figure 4: Guild assignments for the datasets using FUNGuild. (a) Proportions of the sequence richness and OTU richness assigned to guilds in each treatment; (b) Heatmap of the main genera affiliated to animal pathogen, plant pathogen and dung saprotroph. Unpredicted OTUs and the assigned OTUs with the confidence ranking of “possible” have been excluded in (a). Because Schizothecium and Zopfiella constitute a vast majority of dung saprotroph, the two genera were selected and separated with other low-abundance pathogens

Beside the two guilds of saprotrophs, plant pathogen and animal pathogen followed in the rank of guild sequence richness. Although there was no significant difference in the ratios of plant pathogen among treatments, the typical representative of Trichothecium differed between CK (0.28%) and other treatments (0.01%–0.06%). Meanwhile, both the animal pathogen of Lecanicillium and the whole guild had significantly higher abundances in CK (0.19% and 0.62%) than in MNS and CNS-treated soils (both ratios of the genus were 0.02%, and both percentages of the animal guild in the two treatments were 0.14%, Figs. 4a and 4b).

In this study, changes of soil fungal community structure over a 11-year different fertilization managements in a commercial greenhouse monoculture system was assessed. Coupled with our previous study on soil bacteria [34], a comprehensive evaluation of the long-term fertilization on soil microflora was presented.

In the last study, treatment of CNS was proved to have the greatest positive effect on soil fertility, maintaining a high biodiversity as the non-fertilizer treatment of CK and a rational structure of the bacterial community [34]. Coincidentally, the fungal diversity following the CNS treatment was also as high as CK, while, both richness in treatments of CN and MNS significantly decreased (Tab. 1). Result that the no-fertilizer control plots maintained relatively higher fungal diversity and richness was consistent with previous reports [42,43]. Indeed, soil fungal biomass and abundance was found to be negatively correlated with soil fertility [43,44]. In the nutrient-poor environment (i.e., the non-fertilizer treatment of control), crop needs certain functional fungi, e.g., AMF, with a larger population size and a higher diversity to meet the demand for its growth, while, in a nutrient-rich environment (i.e., soils fertilized), diversity of the AMF decreases [42]. Also, the imbalanced addition of nutrients contributes to the reduction of species richness in CN and MNS soils. As calculated in our last study, the C/N ratios of the fertilizers applied in CN, MNS and CNS treatments were 18, 44 and 33, respectively [34]. Soils after long-term CN and MNS treatments might be C-lacking or N-devoid, which will inevitably suppress some fungal species. For example, in CN soils, the abundance of the cellulose-responsive fungi was supposed to be low or even undetectable. However, the soil treated by CNS recovered the decrease of biodiversity brought by CN and MNS, and it was reported that soils with higher degree of species richness are more stable in ecosystem function, and resistant to environmental stresses [41,45].

Although both CK and CNS soils maintained higher species richness, the variation of fungal assemblages between the two treatments was significant as revealed by the PERMANOVA test. The CK soils mainly assembled members of Hypocreales and Sordariales_Incertae_Sedis (Fig. 3). Chen et al. [46] reported that Hypocreales showed increased abundance with continuous cropping, and interestingly, most of the enrichment of Hypocreales identified in CK soils were pathogens as inferred by FUNGuild (Fig. 4). For example, the subfamily Nectriaceae, especially Fusarium, was notorious for the broad-spectrum pathogenicity [47], Lecanicillium were leaf miners, Madurella was animal pathogen causing mycetoma [48], and species of Pleosporales were reported to be able to attack Chusquea serrulatae by producing elongated yellow spots in leaves [49]. Similar to the assemblages in CK soils, pathogens also converged in CN soils. For example, Devriesia as revealed by LEfSe (Fig. 3) was recorded to be able to cause sooty blotch and flyspeck on trees [50].

Unlike the CK and CN soils, most of the microbial enrichment in CNS soil was beneficial. For example, Pezizaceae dominates the beneficial ectomycorrhizal fungal communities [51]. Cephalotheca (C. sulfurea) is known to promote plant growth by producing Gibberellins [52], and the Ascomycetes belonging to Chaetothyriales (MSX 47445) have antibacterial activities against Staphylococcus aureus [53]. Of all the enrichment, Schizothecium is the most prominent. As a coprophilous fungus, Schizothecium can be found in various types of dung, and is a well-known biocontrol agent against soil-borne pathogens [54,55]. Although Schizothecium had no direct relationship with soil fertility, the dominant subordinator, OTU456 was found to be positively correlated with contents of soil OM, TN and AN (the correlation coefficients were 0.717, 0.747 and 0.650, Appendix C). This implied that it was reciprocal for enrichment of the dung-dweller of Schizothecium and high fertility of the greenhouse soil.

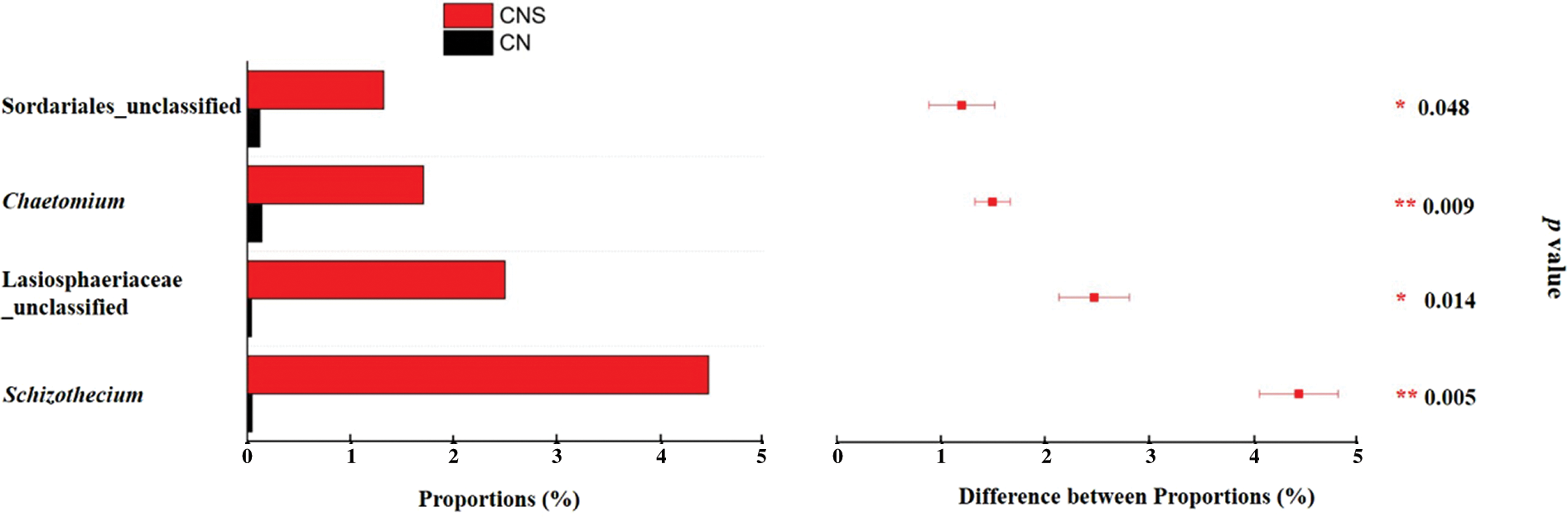

Sordariales was reported to dominate the cellulose decomposition process after straw return to field [56]. In this study, we also found that, the relative abundance of Sordariales in CNS soils (12.4%) was significantly higher than that in CN soils (3.3%). Specifically, on the genus level, Schizothecium and Chaetomium differed significantly (Fig. 5). Except Schizothecium is beneficial as illustrated above, the lignocellulosic degrader Chaetomium is also famous for its ability in activating the defense system of plant to antagonize pathogens, e.g., Pyrenophora tritici-repentis and Rhizoctonia Solani, etc. [57,58]. Results that pathogens accumulated in treatments of CN while the beneficial assembled in CNS soils proved that straw return was effective in mitigating the continuous monocropping obstacles in the GVC system.

Figure 5: Extended error bar plot showing the significantly (p < 0.05) abundant genera in soils of CNS. Comparison was conducted for the main genera (with average relative abundance >1% in either treatment) with paired t-test

In conclusion, we conducted an accurate diagnosis about the fungal community composition after continuous cropping, and evaluated the effects of different long-term fertilization regimes on community structure in the GVC system. After consecutive monoculturing, pathogenic fungi accumulated, and the obstacles can be relieved by effective fertilizing. The CNS treatment restored soil biodiversity and significantly altered the fungal composition with pathogens decreasing and probiotics increasing. The CNS treatment is of crucial importance for sustainable development of the GVC system.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Major Science and Technological Innovation Project of Shandong Province (2019JZZY0110721), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31600084), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFD0800403).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

1. Brussaard, L., De Ruiter, P. C., Brown, G. G. (2007). Soil biodiversity for agricultural sustainability. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, 121(3), 233–244. DOI 10.1016/j.agee.2006.12.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Leticia, P. L., Mario, Z. A., Santiago, C. G. M., Marc, B. (2019). Plant intraspecific variation modulates nutrient cycling through its below ground rhizospheric microbiome. Journal of Ecology, 107(4), 1594–1605. DOI 10.1111/1365-2745.13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xu, J., Liu, S. J., Song, S. R., Guo, H. L., Tang, J. J. et al. (2018). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi influence decomposition and the associated soil microbial community under different soil phosphorus availability. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 120, 181–190. DOI 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.02.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bonfante, P., Anca, I. A. (2009). Plants, mycorrhizal fungi, and bacteria: A network of interactions. Annual Review of Microbiology, 63(1), 363–383. DOI 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Leigh, J., Hodge, A., Fitter, A. H. (2009). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi can transfer substantial amounts of nitrogen to their host plant from organic material. New Phytologist, 181(1), 199–207. DOI 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02630.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Verma, M., Brar, S. K., Tyagi, R. D., Surampalli, R. Y., Valéro, J. R. (2007). Antagonistic fungi, Trichoderma spp.: Panoply of biological control. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 37(1), 1–20. DOI 10.1016/j.bej.2007.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kim, Y. C., Hur, J. Y., Park, S. K. (2019). Biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea by chitin-based cultures of Paenibacillus Elgii HOA73. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 155(1), 253–263. DOI 10.1007/s10658-019-01768-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chang, J., Wu, X., Wang, Y., Meyerson, L. A., Gu, B. et al. (2013). Does growing vegetables in plastic greenhouses enhance regional ecosystem services beyond the food supply? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 11(1), 43–49. DOI 10.1890/100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Guo, J., Liu, X., Zhang, Y. (2010). Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science, 327(5968), 1008–1010. DOI 10.1126/science.1182570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gao, Z. Y., Han, M. K., Hu, Y. Y., Li, Z. Q., Liu, C. F. et al. (2019). Effects of continuous cropping of sweet potato on the fungal community structure in rhizospheric soil. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 49. DOI 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shang, H. S. (2013). Modern immunology of plants. China: China Agriculture Press. [Google Scholar]

12. Li, X. G., Ding, C. F., Zhang, T. L., Wang, X. X. (2014). Fungal pathogen accumulation at the expense of plant-beneficial fungi as a consequence of consecutive peanut monoculturing. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 72, 11–18. DOI 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.01.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li, X. Y., Xiao, L. K., Li, Q. Y., Cao, A. C., Hong, J. et al. (2018). Effect of continuous-cropping on rhizosphere soil fungal community structure of outdoor strawberry. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 31, 2514–2519. [Google Scholar]

14. Wang, S., Cheng, J., Li, T., Liao, Y. (2020). Response of soil fungal communities to continuous cropping of flue-cured tobacco. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 155. DOI 10.1038/s41598-020-77044-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wen, Y. C., Li, H. Y., Lin, Z. A., Zhao, B. Q., Li, Y. Q. (2020). Long-term fertilization alters soil properties and fungal community composition in fluvo-aquic soil of the North China Plain. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1527. DOI 10.1038/s41598-020-64227-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cong, P., Wang, J., Li, Y. Y., Liu, N., Dong, J. X. et al. (2020). Changes in soil organic carbon and microbial community under varying straw incorporation strategies. Soil and Tillage Research, 204, 104735. DOI 10.1016/j.still.2020.104735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li, F., Cao, X., Zhao, L., Yang, F., Wang, J. et al. (2013). Short-term effects of raw rice straw and its derived biochar on greenhouse gas emission in five typical soils in China. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition, 59(5), 800–811. DOI 10.1080/00380768.2013.821391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu, C., Lu, M., Cui, J., Li, B., Fang, C. M. (2014). Effects of straw carbon input on carbon dynamics in agricultural soils: A meta-analysis. Global Change Biology, 20(5), 1366–1381. DOI 10.1111/gcb.12517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ge, Y., Zhang, J. B., Zhang, L. M., Yang, M., He, J. Z. (2008). Long-term fertilization regimes affect bacterial community structure and diversity of an agricultural soil in northern China. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 8(1), 43–50. DOI 10.1065/jss2008.01.270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. He, J. Z., Zheng, Y., Chen, C. R., He, Y. Q., Zhang, L. M. (2008). Microbial composition and diversity of an upland red soil under long-term fertilization treatments as revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 8(5), 349–358. DOI 10.1007/s11368-008-0025-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Miller, M. N., Zebarth, B. J., Dandie, C. E., Burton, D. L., Goyer, C. et al. (2008). Crop residue influence on denitrification, N2O emissions and denitrifier community abundance in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 40(10), 2553–2562. DOI 10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.06.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Philippot, L., Hallin, S., Schloter, M. (2007). Ecology of denitrifying prokaryotes in agricultural soil. Advances in Agronomy, 96, 249–305. [Google Scholar]

23. Schloss, P. D., Gevers, D., Westcott, S. L. (2011). Reducing the effects of PCR amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16S rRNA-Based studies. PLoS One, 6(12), e27310. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0027310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang, L. L., Zhang, H. Q., Wang, Z. H., Chen, G. J., Wang, L. S. (2016). Dynamic changes of the dominant functioning microbial community in the compost of a 90-m3 aerobic solid state fermentor revealed by integrated meta-omics. Bioresource Technology, 203, 1–10. DOI 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.12.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sun, R., Zhang, X. X., Guo, X., Wang, D., Chu, H. (2015). Bacterial diversity in soils subjected to long-term chemical fertilization can be more stably maintained with the addition of livestock manure than wheat straw. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 88, 9–18. DOI 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yuan, H., Ge, T., Zhou, P., Liu, S., Roberts, P. et al. (2013). Soil microbial biomass and bacterial and fungal community structures responses to long-term fertilization in paddy soils. Journal of Soils and Sediments, 13(5), 877–886. DOI 10.1007/s11368-013-0664-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu, J., Zhang, J., Li, D. M., Xu, C. X., Xiang, X. J. (2019). Differential responses of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities to mineral and organic fertilization. MicrobiologyOpen, 9(1), 335. DOI 10.1002/mbo3.920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xiang, X., Liu, J., Zhang, J., Li, D., Kuzyakov, Y. (2020). Divergence in fungal abundance and community structure between soils under long-term mineral and organic fertilization. Soil and Tillage Research, 196, 104491. DOI 10.1016/j.still.2019.104491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ji, L. F., Ni, K., Wu, Z. D., Zhang, J. W., Yi, X. Y. et al. (2020). Effect of organic substitution rates on soil quality and fungal community composition in a tea plantation with long-term fertilization. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 56(5), 633–646. DOI 10.1007/s00374-020-01439-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lalitha, M., Kumar, P. (2015). Soil carbon fractions influenced by temperature sensitivity and land use management. Agroforestry Systems, 90(6), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

31. Tang, V. T., Fu, D. F., Binh, T. N., Rene, E. R., Thanh, T. T. et al. (2018). An investigation on performance and structure of ecological revetment in a sub-tropical area: A case study on Cuatien River, Vinh City, Vietnam. Water, 10(5), 636. DOI 10.3390/w10050636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Anderson, I. C., Cairney, J. W. G. (2004). Diversity and ecology of soil fungal communities: Increased understanding through the application of molecular techniques. Environmental Microbiology, 6(8), 769–779. DOI 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00675.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liang, B., Kang, L. Y., Ren, T., Li, J. L., Chen, Q. et al. (2015). The impact of exogenous N supply on soluble organic nitrogen dynamics and nitrogen balance in a greenhouse vegetable system. Journal of Environmental Management, 154, 351–357. DOI 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.02.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang, X. M., Zhang, Q., Liang, B., Li, J. L. (2017). Changes in the abundance and structure of bacterial communities in the greenhouse tomato cultivation system under long-term fertilization treatments. Applied Soil Ecology, 121, 82–89. DOI 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.08.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. F., Sninsky, J. J., White, T. J. (1990). PCR Protocols–A guide to methods and applications. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

36. Yu, C. Q., Han, F. S., Fu, G. (2019). Effects of 7 years experimental warming on soil bacterial and fungal community structure in the Northern Tibet alpine meadow at three elevations. Science of the Total Environment, 655, 814–822. DOI 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang, H., Fu, G. (2020). Responses of plant, soil bacterial and fungal communities to grazing vary with pasture seasons and grassland types, northern Tibet. Land Degradation & Development, 21(12), 48. DOI 10.1002/ldr.3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kõljalg, U., Nilsson, R. H., Abarenkov, K., Tedersoo, L., Taylor, A. F. S. et al. (2013). Towards a unified paradigm for sequence-based identification of fungi. Molecular Ecology, 22(21), 5271–5277. DOI 10.1111/mec.12481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Segata, N., Izard, J., Waldron, L., Gevers, D., Miropolsky, L. et al. (2011). Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biology, 12(6), R60. DOI 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Nguyen, N. H., Song, Z., Bates, S. T., Branco, S., Tedersoo, L. et al. (2015). Funguild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecology, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

41. Klaubauf, S., Inselsbacher, E., Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S., Wanek, W., Gottsberger, R. et al. (2010). Molecular diversity of fungal communities in agricultural soils from Lower Austria. Fungal Diversity, 44(1), 65–75. DOI 10.1007/s13225-010-0053-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lin, X. G., Feng, Y. Z., Zhang, H. Y., Chen, R. R., Wang, J. H. et al. (2012). Long-term balanced fertilization decreases arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity in an Arable Soil in North China revealed by 454 pyrosequencing. Environmental Science & Technology, 46(11), 5764–5771. DOI 10.1021/es3001695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Monika, M., Hanna, K., Wojciech, S. (2015). Fungal communities in barren forest soil after amendment with different wood substrates and their possible effects on trees’, pathogens, insects and nematodes. Journal of Plant Protection Research, 55(3), 301–311. DOI 10.1515/jppr-2015-0042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Hgberg, M. N., Chen, Y., Hgberg, P. (2007). Gross nitrogen mineralisation and fungi-to-bacteria ratios are negatively correlated in boreal forests. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 44(2), 363–366. DOI 10.1007/s00374-007-0215-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Xun, W. B., Li, W., Xiong, W., Ren, Y., Liu, Y. P. et al. (2019). Diversity-triggered deterministic bacterial assembly constrains community functions. Nature Communications, 10(1), 59. DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-11787-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Chen, M., Li, X., Yang, Q., Chi, X., Pan, L. et al. (2012). Soil eukaryotic microorganism succession as affected by continuous cropping of peanut-pathogenic and beneficial fungi were selected. PLoS One, 7(7), e40659. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0040659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Waalwijk, C., Heide, R. V. D., Vries, I. D., Lee, T. V. D., Schoen, C. et al. (2004). Quantitative detection of Fusarium species in wheat using Taqman. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 110(5/6), 481–494. DOI 10.1023/B:EJPP.0000032387.52385.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Cuthbertson, A. G. S., Walters, K. F. A. (2005). Pathogenicity of the entomopathogenic fungus, Lecanicillium muscarium, against the sweetpotato whitefly Bemisia tabaci under laboratory and glasshouse conditions. Mycopathologia, 160(4), 315–319. DOI 10.1007/s11046-005-0122-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang, Y., Crous, P. W., Schoch, C. L., Hyde, K. D. (2012). Pleosporales. Fungal Diversity, 53(1), 1–221. DOI 10.1007/s13225-011-0117-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Li, W., Xiao, Y., Wang, C., Dang, J., Chen, C. (2013). A new species of Devriesia causing sooty blotch and flyspeck on rubber trees in China. Mycological Progress, 12(4), 733–738. DOI 10.1007/s11557-012-0885-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Tedersoo, L., Hansen, K., Perry, B. A., Kjller, R. (2006). Molecular and morphological diversity of Pezizalean ectomycorrhiza. New Phytologist, 170(3), 581–596. DOI 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01678.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hamayun, M., Khan, S. A., Khan, A. L., Afzal, M., Lee, I. J. (2012). Endophytic Cephalotheca sulfurea AGH07 reprograms soybean to higher growth. Journal of Plant Interactions, 7(4), 301–306. DOI 10.1080/17429145.2011.642013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Elelimat, T., Figueroa, M., Raja, H. A., Graf, T. N., Adcock, A. F. et al. (2012). Benzoquinones and terphenyl compounds as phosphodiesterase-4B inhibitors from a fungus of the order Chaetothyriales (MSX 47445). Journal of Natural Products, 76(3), 382–387. DOI 10.1021/np300749w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Richardson, M. J. (2001). Diversity and occurrence of coprophilous fungi. Mycological Research, 105(4), 387–402. DOI 10.1017/S0953756201003884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Watanabe, T. (2009). Evaluation of sordaria spp. as biocontrol agents against soilborne plant diseases Caused by Pythium aphanidermatum and Dematophora necatrix. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 57, 680–687. [Google Scholar]

56. Ivan, P. E., Rima, A. U., Donald, R. Z. (2008). Isolation of fungal cellobiohydrolase I genes from sporocarps and forest soils by PCR. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 74(11), 3481–3489. DOI 10.1128/AEM.02893-07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Istifadah, N., Mcgee, P. A. (2006). Endophytic Chaetomium globosum reduces development of tan spot in wheat caused by Pyrenophora tritici-repentis. Australasian Plant Pathology, 35(4), 411–418. DOI 10.1071/AP06038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Di, P. A., Gutrella, M., Pachlatko, J. P., Schwinn, F. J. (1992). Role of antibiotics produced by Chaetomium globosum in biocontrol of Pythium ultimum, a causal agent of damping-off. Phytopathology, 82(2), 131–135. DOI 10.1094/Phyto-82-131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Appendix A: PERMANOVA test based on Bray-Curtis distance measures

Appendix B: Proportion of reads with function predicted and different confidence rankings inferred by FUNGuild

Appendix C: OTU composition of Schizothecium and correlations with physicochemical properties. (a) Average relative abundance of the composing OTUs in each treatment; (b) Person’s correlationship between OTUs and physicochemical properties. Abbreviations in (b) were as follows: OM, organic matter; TN, total nitrogen; AN, available nitrogen; AP, available phosphorus; AK, available potassium. * and ** represent significance at p < 0.05 and 0.01

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |