| Journal of Renewable Materials |  |

DOI: 10.32604/jrm.2021.015292

ARTICLE

Nodes Effect on the Bending Performance of Laminated Bamboo Lumber Unit

1College of Civil Engineering, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, 210037, China

2Ganzhou Sentai Bamboo Company Ltd., Ganzhou, 341001, China

3University of Melbourne, Melbourne, 3010, Australia

4University College London, London, WC1E 6BT, UK

5University of Naples Federico II, Naples, 80133, Italy

*Corresponding Author: Haitao Li. Email: lhaitao1982@126.com

Received: 07 December 2020; Accepted: 20 January 2021

Abstract: This research studied the ultimate bearing capacity of laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit and thereby calculated the maximum bending moment. The load-displacement chart for all specimens was obtained. Then the flexural capacity of members with and without bamboo nodes in the middle section was coMPared. The bending experiment phenomenon of LBL unit was concluded. Different failure modes of bending components were analysed and concluded. Finally, the bending behaviour of LBL units is coMPared with other bamboo and timber products. It is shown that the average ultimate load of BS members is 866.1 N, the average flexural strength is 101 MPa, the average modulus of elasticity is 8.3 GPa, and the average maximum displacement is 17.02 mm. The average ultimate load of BNS members is 1008.1 N, the average flexural strength is 118.02 MPa, the average modulus of elasticity is 9.9 GPa, and the average maximum displacement is 18.26 mm. Laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit without bamboo nodes (BNS) has relatively higher flexural strength coMPared with LBL unit with bamboo nodes (BS). The presence of bamboo nodes reduces the strength of the entire structure. Three failure modes were concluded for BS members, and two failure modes were observed for BNS members during the experimental process. According to a coMParison between the LBL unit and other products, the flexural strength and bending modulus of elasticity of the LBL unit are similar as bamboo scrimber and raw bamboo components, which is much higher than timber components.

Keywords: Laminated Bamboo Lumber; bending test; flexural strength; bamboo node

Since the 21st century, high-rise reinforced concrete structure is still the mainstream of architecture. Still, reinforced concrete’s building process is accoMPanied by huge energy loss and carbon dioxide emission [1]. Hence, green building materials and prefabricated buildings are gradually entering people’s life. As building materials, wood and bamboo are both familiar and historical materials. From environmental iMPact and material nature, the advantage of wood as a building material still exceeds other products on the market [2−6]. The mechanical properties of bamboo are similar to those of wood [7], and bamboo resources are abundant in Asia, Africa and Latin America [8−14]. Bamboo is highly reproducible, and the stems of bamboo could mature in eight years. It is an excellent building material. With sufficient research, bamboo can become a sustainable alternative to the world's current building materials. Therefore, the study and application of bamboo have attracted wide attention from scholars in recent years. According to bamboo mechanical tests, bamboo has high tensile strength, specific strength to weight, and loads bearing capacity. Bamboo also has strong earthquake resistance due to the long, elastic and robust nature of its fibres. It also has a natural insulation performance and can save heat. Besides, it is a durable material under appropriate treatment [15−22].

Mahdavi et al. [23,24] revealed that a lack of experience with bamboo processing and construction is considered a factor in current low efficiencies and high costs associated with bamboo construction. With further study of this material, it is expected that this material can be more fully utilized. Bamboo is a hollow tube with a significant moment of inertia and cross-sectional area ratio, which can effectively resist bending forces. However, it is difficult to create connections for the circular tube section and adopted in building structures that require a flat surface. Laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) solves the problem of round tube shape of bamboo materials because it can maintain a rectangular section and can be used in traditional building structures [23,25]. Besides, due to the species, age, climate, moisture content and different heights of the bamboo, it is difficult to generalise the bamboo’s characteristics. LBL can make its mechanical properties relatively consistent [15].

Laminated bamboo lumber unit is a unit component with a fixed width and thickness that make up laminated bamboo lumber (LBL). Through split, planed, bleached, caramelized, the fast-growing and short period original bamboo can be made into laminated bamboo lumber unit [26]. According to Mahdavi et al. [23], LBL is a kind of laminated bamboo glued together by unit components with adhesive [27]. LBL is mainly used to make up the situation that the unprocessed round bamboo components cannot meet the requirements of physical and mechanical material properties and components’ size of the modern building structure.

Li et al. [27] contended that LBL has high strength, which can meet the physical and mechanical properties of multi-story building structures. Also, LBL can be widely used in beams and columns of building structures to solve large-diameter natural wood’s technical problems in general multi-story bamboo structures. Bamboo has been commonly used in making formwork, floorboard, floor, furniture and other products, but as a building material application has just started. The current technology of bamboo composite production can flexibly control its components’ size and length and has a reasonable prospect of popularisation and application.

For laminated bamboo lumber (LBL), Zhang et al. [28] coMPared physical and mechanical properties of bamboo with those of wood, bamboo, porous brick masonry and concrete used in several common building structures, and found that the tensile strength and flexural strength of LBL are higher than that of larch larix gmeini, fraxinus mandshurica and cunninghamia lanceolata, and much higher than that of C20 concrete and sintered porous brick. Besides, LBL has high compressive strength and low density, making the structure occupy less area and improve the usable building area. The shear strength of LBL is higher than that of timber materials, and it shows good ductility. Mahdavi et al. [23] proved that LBL is a good building material and can be used as a substitute for common timber materials.

According to Botanicals [29], bamboo tends to have a connected stem called a culm. Bamboo node is an entity node, where each culm segment begins and ends. Nodes are characterized by a ring expanding around the end of the stem node. Bamboo nodes have a considerable iMPact on the mechanical properties of bamboo members. Shao et al. [30] revealed that the tensile strength and shear strength of moso bamboo experimental members without nodes were higher than members with nodes about 30%. In contrast, the bending strength of moso bamboo members is similar with or without bamboo nodes. The study conducted by Anokye et al. [31] shows that the bending properties of laminated bamboo timber with bamboo nodes increased with increasing node spacing. The failures tended to occur at the bamboo nodes location.

Laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) plays an essential role in the engineered bamboo field for construction. However, there are few studies on laminated bamboo lumber units in the market. As the primary component of LBL, the study of mechanical properties is indispensable for LBL unit. This study mainly focuses on the ultimate bearing capacity, flexure strength and bending modulus of elasticity of LBL units. In this paper, the flexural strength of laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit is measured by the four-point bending resistance method under the guidance of Chinese standard JG/T 199-2007. Two different types of specimens of a similar size (about 7.65 × 22 × 220 mm) were used in the experiment and were coMPared: With bamboo nodes sections in the middle of the specimen and without bamboo nodes sections in the middle of the specimen. Here, all the bamboo nodes had similar sizes (about 7.65 × 22 × 8 mm) and were located in the middle of the experimental component. Then through the coMParison with sections with other materials, the advantages and disadvantages of LBL units in bending performance can be obtained. By coMParing the bending strength and elastic modulus of the two groups of specimens, the effects of bamboo nodes on the bending performance of the LBL unit were coMPared and analyzed.

However, there are many challenges in the whole research process. First, there are no specific codes and standards of the LBL unit for structural use. Second, because the mechanical property of bamboo material is not stable, and the structure reliability is low, the mechanical properties of bamboo members of the same type and size may vary significantly. It is necessary to exclude the members with substantial differences and consider the average strength of the specimens. Finally, the failure modes and mechanism of different specimens vary greatly, so it is difficult to summarize all the failure modes and find the rules.

Because of the correlated research direction and specific research methods on bamboo materials in China, this experiment was designed according to China’s construction industry standards. The dimensions, processing methods, experimental methods and calculation formulas of the experimental specimens are mostly based on Chinese standard JG/T 199-2007 Testing methods for physical and mechanical properties of bamboo used in building [32].

2.2 Specific Data on Experimental Members

Harvested at 3-4 years, moso bamboo (phyllostachys pubescen) were chosen from Yongan, Fujian. Both the inner yellow and outer green parts were removed, processed into bamboo chips of fixed width, thickness and length, and dried to a moisture content of 8% to 12%, thus obtaining experimental specimens.

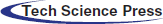

Two types of experimental specimens are designed and manufactured for the experiment. Sixteen specimens have bamboo nodes in the middle part, shown in Fig. 1a, while the other sixteen specimens have no bamboo nodes in the central region, which is shown in Fig. 1b. Here, BS components mean laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit with bamboo nodes, while BNS components mean laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit without bamboo nodes.

Figure 1: Laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit experimental members (a) Laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit with bamboo nodes (BS) (b) Laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit without bamboo nodes (BNS)

The designed dimension is the same for the two types of specimens. The length (L), the thickness (t) and the height (h) are 220 mm, 22 mm and 7.65 mm, respectively. Specific dimension data is shown in the results part.

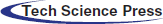

According to Chinese standard, JG/T 199-2007 Testing methods for physical and mechanical properties of bamboo used in building [32], the testing machine is adopted to apply force and measure displacement. The approach of symmetrical loading at two points was adopted. The distance between the two loading points and the support centre line was 50 mm, respectively, and the spacing between loading points was 80 mm ± 1 mm. The specimen is placed on the two supports of the experimental device, as shown in Fig. 2a. Here, specific experimental apparatus is shown in Fig. 2b.

Figure 2: Experimental apparatus for bending test (a) Specific experimental Set-up (b) Experimental apparatus

The load control method is displacement load mixed control. The load is loaded at the speed of 10 N/s to about 60% maximum bearing capacity of and then uniformly loaded to the failure of the specimen at the speed of 2 mm/min. The ultimate bearing capacity P is recorded, and the bending strength is calculated according to the formula Eq. (1):

Here,

is flexural strength, MPa,

is flexural strength, MPa,

is ultimate loading, N,

is ultimate loading, N,

t is the thickness of specimen, mm,

h is the height of specimen, mm,

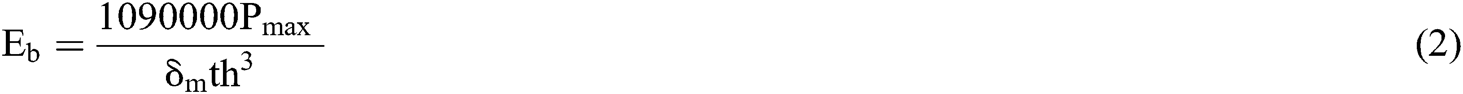

The bending modulus of elasticity is calculated according to the formula Eq. (2):

Here,

is bending modulus of elasticity of rift grain,

is bending modulus of elasticity of rift grain,  ,

,

is ultimate loading, N,

is ultimate loading, N,

is the deflection of the pure bending section under the action of

is the deflection of the pure bending section under the action of  ,

,

t is the thickness of specimen, mm,

h is the height of specimen, mm,

3.1 Mechanism and Failure Modes Analysis

The experimental phenomena are as follows: Relationship between load and displacement linear increase early experiments; there is no change on the specimen surface to 0.4 to 0.5 times the ultimate loads. The pressure points have visible extrusion deformation across the top surface in the middle, which accounts for the bamboo pore in single-point pressure compressed, causing unrecoverable deformation. Deformation of the part has no iMPact on the subsequent development of flexural bearing capacity and crack of the specimen. With the increase of the bearing capacity to 0.5 and 0.7 times the maximum load, the specimen yields gradually, and the vertical displacement in the mid-span is evident. Then, the specimen has a slight sound. When the maximum bearing capacity is reached, there is a clear cracking sound. As the displacement control continues to be loaded, the bottom crack develops, and the load decreases rapidly.

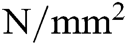

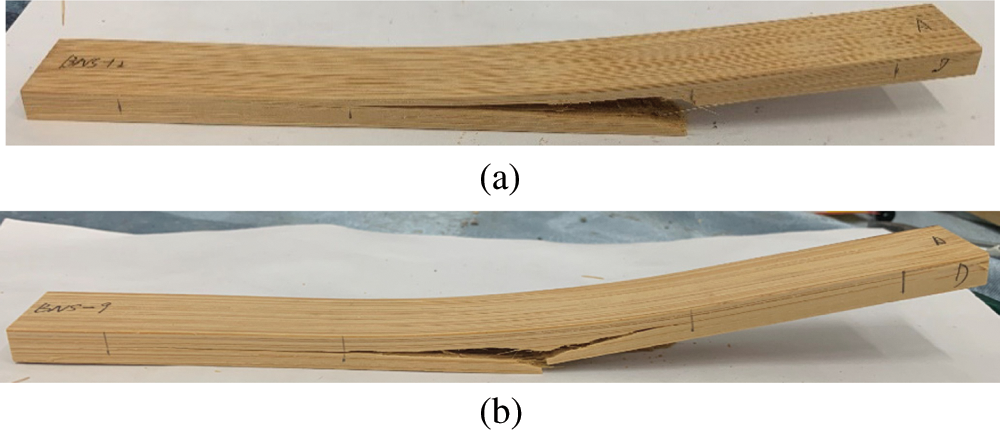

During the whole experimental process, three failure modes were observed for BS components, and BNS components mainly show one failure mode during the experimental process.

3.1.1 Failure Mode of BS Members

As shown in Fig. 3, three failure modes observed for BS components have different features, which are described below:

I-Mode

The failure starts from the bamboo nodes in the middle of the member, and the crack extends along the longitudinal direction to one side, which is shown in Fig. 3a.

II-Mode

The failure starts at approximately 1/3 and 2/3 distance of the member and extends vertically up to about half its height, shown in Fig. 3b.

III-Mode

The failure starts from approximately 1/3 distance of the member, and the crack extends along the longitudinal direction to the other side, which is shown in Fig. 3c.

Figure 3: Three Failure Mode of BS members (a) I Failure Mode example for BS members (b) II Failure Mode example for BS members (c) III Failure Mode example for BS members

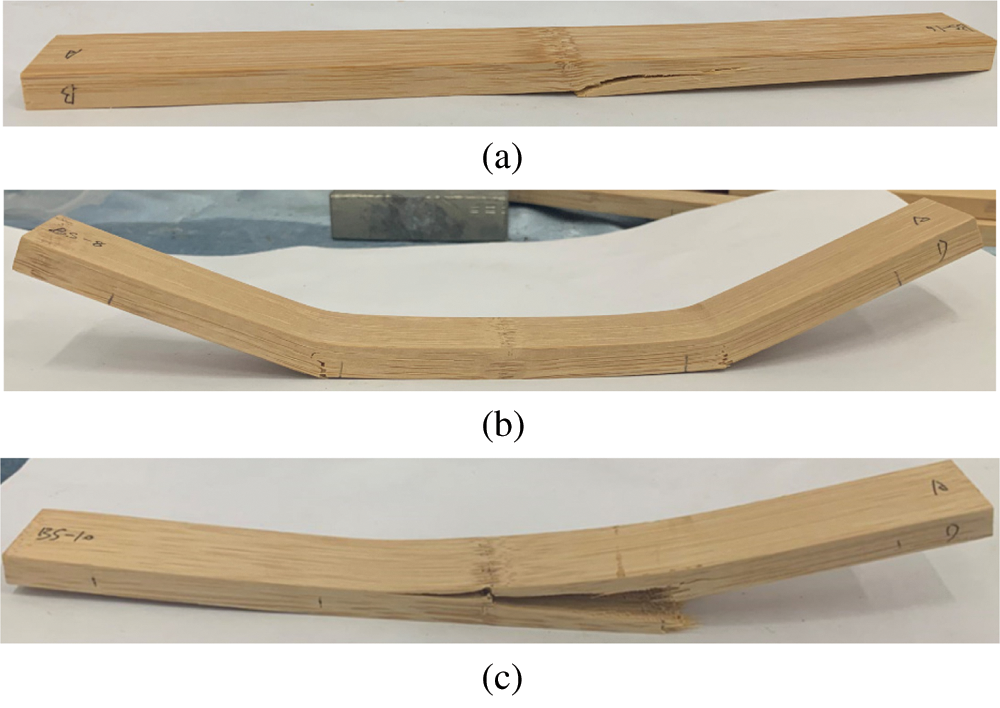

As shown in Tab. 1, the proportion of III-Mode is 25%, which is fewer than that of I-Mode and II-Mode. These three failure modes are common in bending process of BS members.

Table 1: Quantity and percentage of different failure modes for BS members

3.1.2 Failure Mode of BNS Members

According to the observation of BNS members, IV failure occurs in most BNS components. Only one-member (BNS-19) show V failure mode phenomenon, which shows a certain fortuity.

IV-Mode

Similar to III-Mode, the failure starts from approximately 1/3 distance of the BNS member. The crack extends along the longitudinal direction to the other side, shown in Fig. 4a.

V-Mode

The failure starts from in the bottom middle of the member, and the crack extends along the longitudinal direction to two sides, which is shown in Fig. 4b.

Figure 4: Failure mode of BNS members (a) IV Failure Mode example for BNS members (b) V Failure Mode example for BNS members

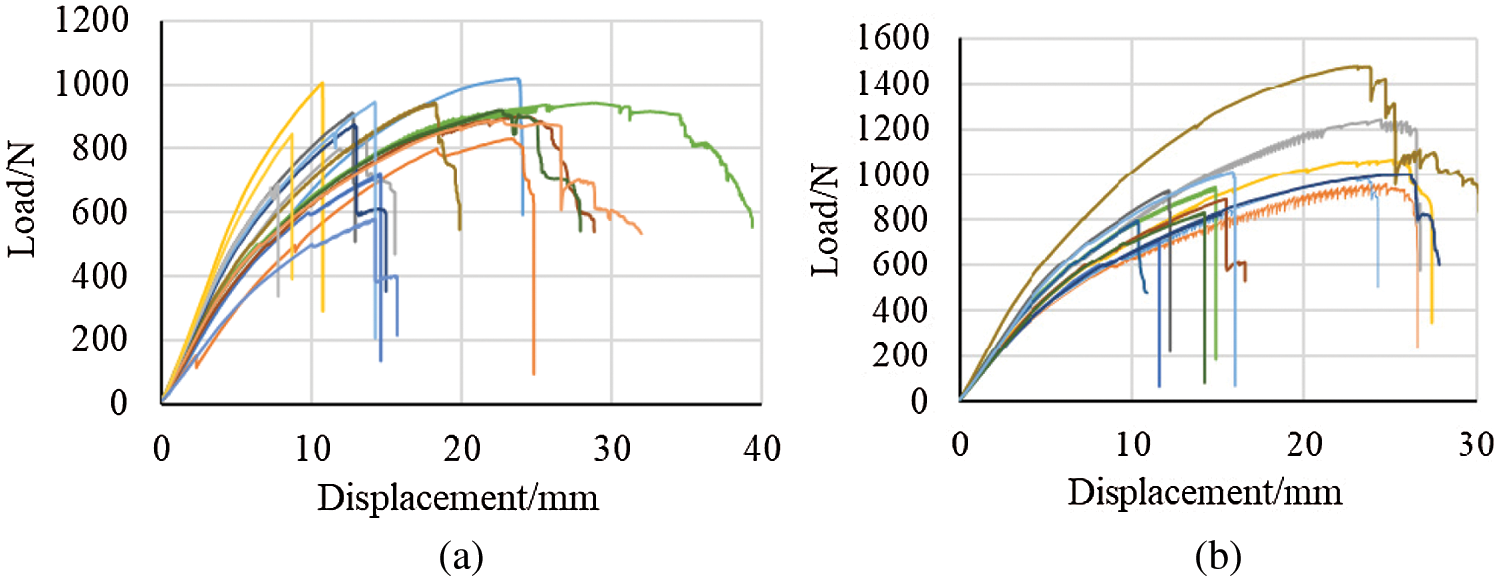

3.2 Load-Displacement Response

The load-displacement curve for the two groups is shown in Figs. 5a and 5b. It can be seen from the displacement load curves of two groups that the specimens are subjected to brittle failure due to bending, and the yield load of each specimen rises obviously. As the displacement control increases, the load begins to decrease.

Figure 5: BS and BNS Load-Displacement Chart (a) BS Load-Displacement Chart (b) BNS Load-Displacement Chart

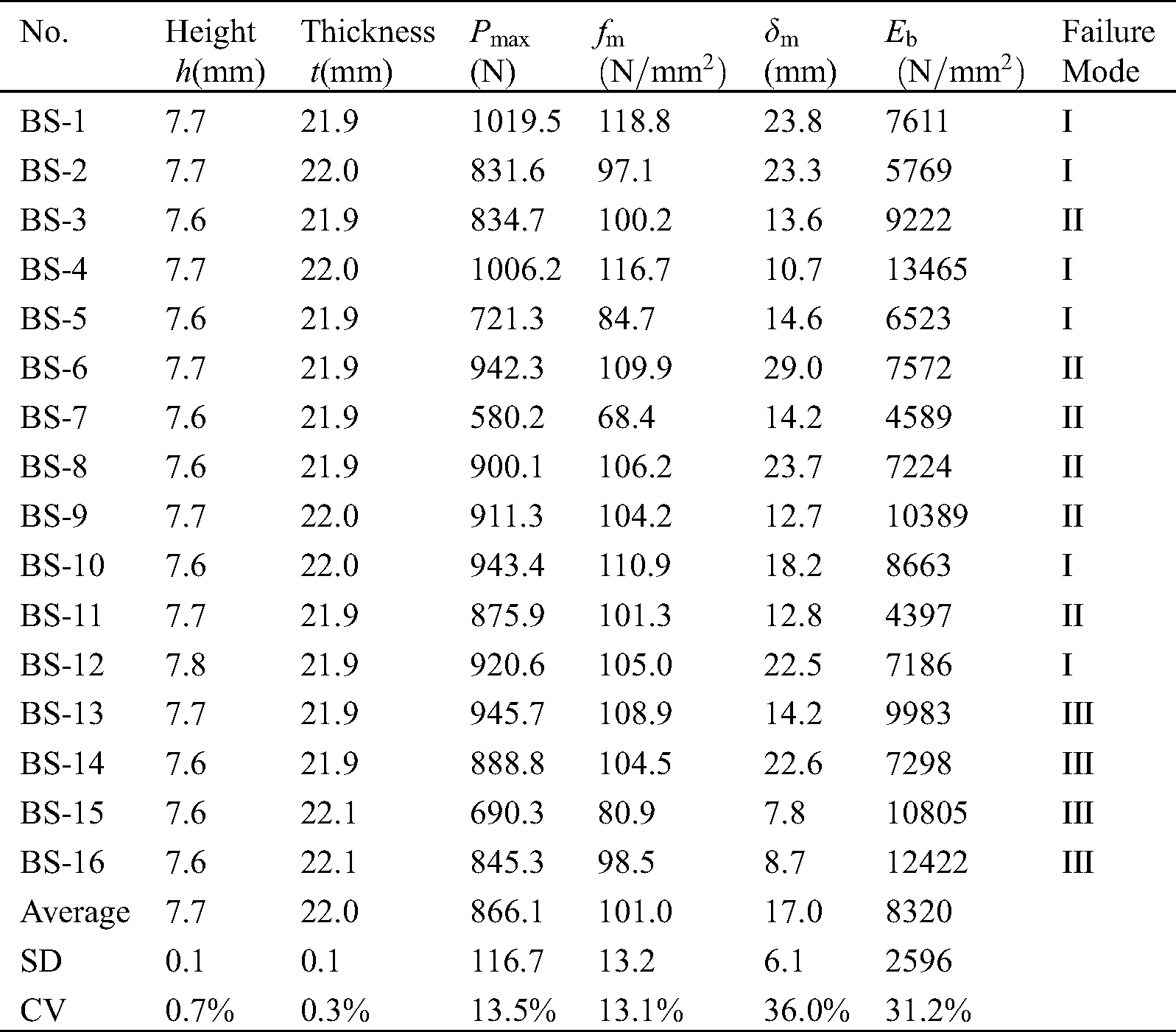

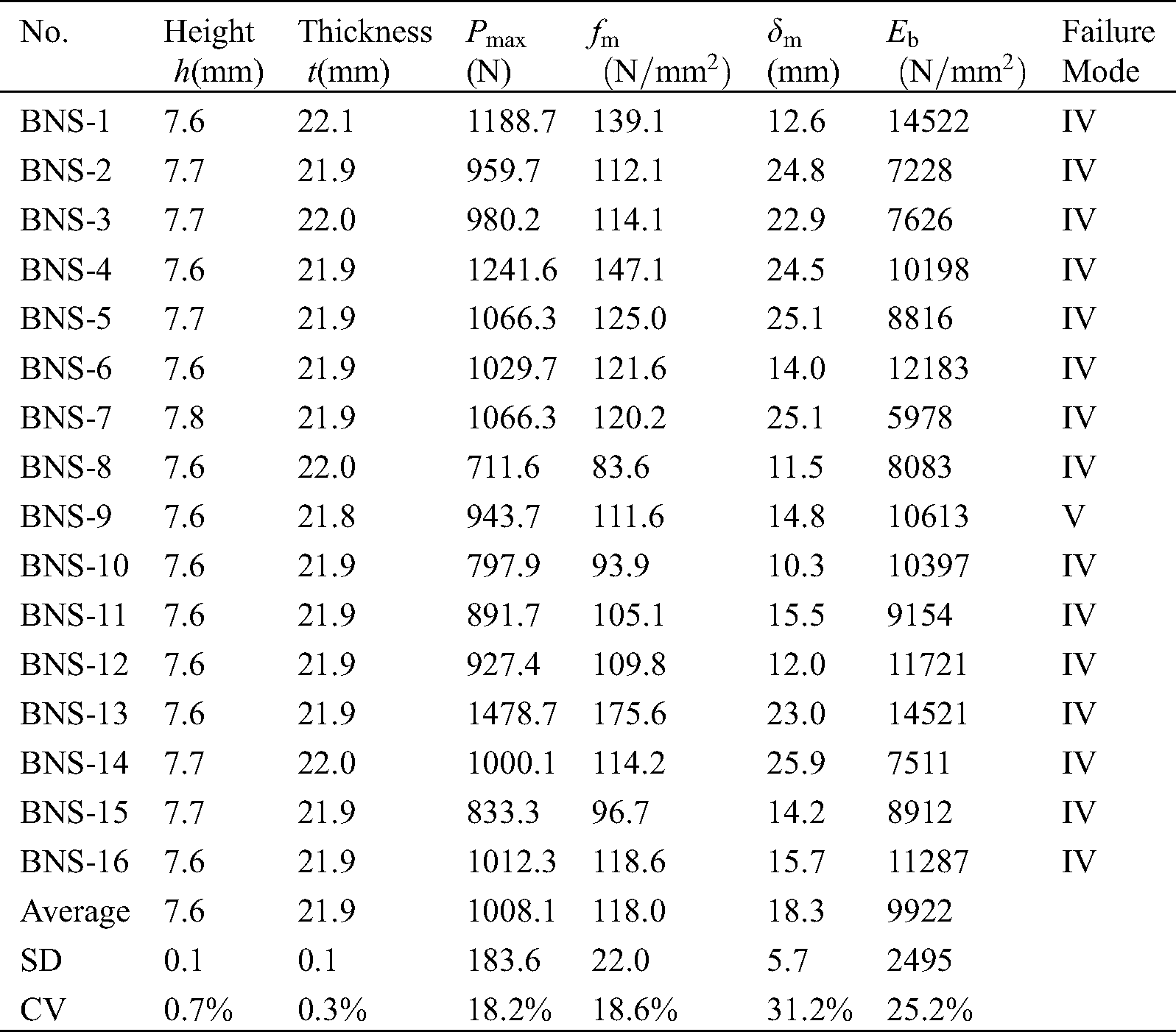

The results of ultimate bearing capacity, flexural strength and bending modulus of elasticity of two groups of different types of LBL units are shown in Tabs. 2 and 3, respectively. Here,  is ultimate loading,

is ultimate loading,  is flexural strength,

is flexural strength, is the deflection of the pure bending section under the action of

is the deflection of the pure bending section under the action of  ,

,  is bending modulus of elasticity of rift grain, Average is the average value of the parameters, SD and CV are standard deviations and coefficient of variation of parameters respectively.

is bending modulus of elasticity of rift grain, Average is the average value of the parameters, SD and CV are standard deviations and coefficient of variation of parameters respectively.

Table 2: Results of BS components

Table 3: Results of BNS components

For some failure modes with obvious fracture extension (such as III- Failure Mode), when the cracks begin to develop laterally, the specimen curve enters short yield stage. After the crack continues to extend, the load decreases again, which leads to the apparent waviness of the displacement load curve when the load drops. For some of the members whose cracks extend instantaneously, the load will drop all at once.

BS components show I, II and III Failure Modes. There is a big difference in crack extension, I-Mode and III-Mode produce very long transverse crack, while II-Mode produces only small crack, which does not extend. BNS components mainly present IV Failure Mode, which means that most failure starts from approximately 1/3 distance of the members. The crack extends along the longitudinal direction to the other side.

Although there are five different failure modes, almost all of the components that come close to failure are: When the maximum bearing capacity was reached, there was a clear cracking sound, then the bottom crack developed, and the load decreased rapidly. However, the difference was the path of cracks development. For I, III, IV and V Mode, the cracks developed and extended immediately along the longitudinal direction to the other side, while the cracked for II Mode extends vertically. All cracks development was instantaneous.

There is no significant relationship between the failure modes and the maximum displacement.

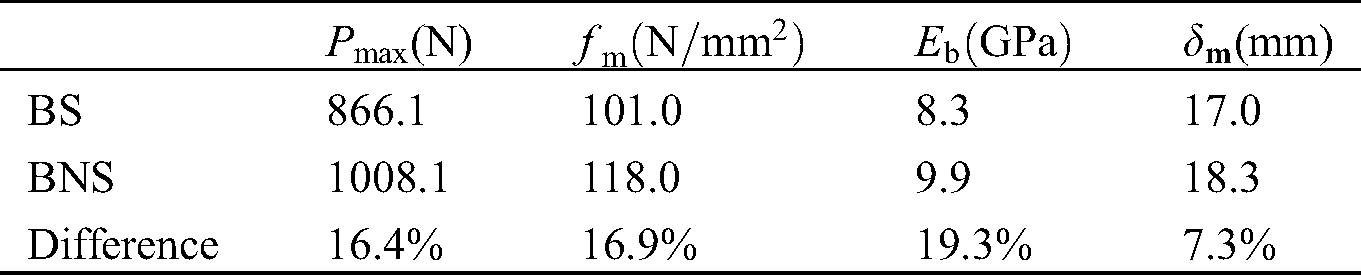

4.2 Flexural Strength and Bending Modulus of Elasticity of Rift Grain Results Analysis

The average ultimate load of BS members is 866.1 N, the average flexural strength is 101 MPa, the average modulus of elasticity is 5.7 GPa, and the average maximum displacement is 17.0 mm. The average ultimate load of BNS members is 1008.1 N, the average flexural strength is 118.0 MPa, the average modulus of elasticity is 5.9 GPa, and the average maximum displacement is 18.3 mm. As shown in Tab. 4, the average ultimate load and flexural strength BNS specimens are about 16.5% higher than BS specimens. The modulus of elasticity of both BS and BNS components are similar. Hence, laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit without bamboo nodes (BNS) has relatively higher flexural strength. The presence of bamboo nodes reduces the strength of the entire structure, but bamboo nodes have few iMPacts on the modulus of elasticity. According to the standard deviation and coefficient of variation, the ultimate loads of the two groups of components are relatively consistent.

Table 4: Difference between BS and BNS specimens

There is a little difference in displacement between two groups, and the average displacement is about 17–18 mm (standard deviation is about 6 mm). It is shown that it is necessary to improve the stiffness of the LBL unit to reduce the deflection and increase the use of flexural strength.

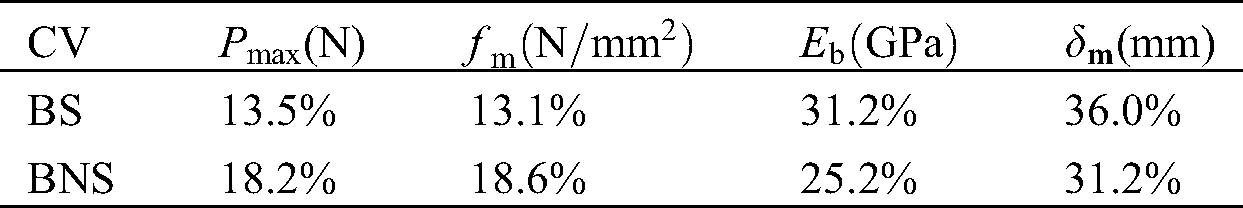

Table 5: Coefficient of variation of BS and BNS results

Tab. 5 shows the coefficient of variation of flexural ultimate bearing capacity and flexural strength data ranged from 13.1% to 18.6%. The test results showed that the overall stability was relatively good. However, the coefficient of variation of maximum deflection and the modulus of elasticity ranged from 25.2% to 31.2%, which showed relatively worse stability. There was no significant influence of failure modes in the bearing strength along the grain.

The standard deviation and variation of the maximum displacement are significant, and the displacement is mostly in the range of 10 mm–15 mm and 20 mm–15 mm. The possible reasons are that the mechanical properties of different moso bamboo materials selected for the experiment are different, the failure modes are different, and the moisture content is different. Also, because of the relationship between the characteristics of biological materials and the special treatment during the fabrication of LBL units, the varying stiffness of LBL units is reasonable.

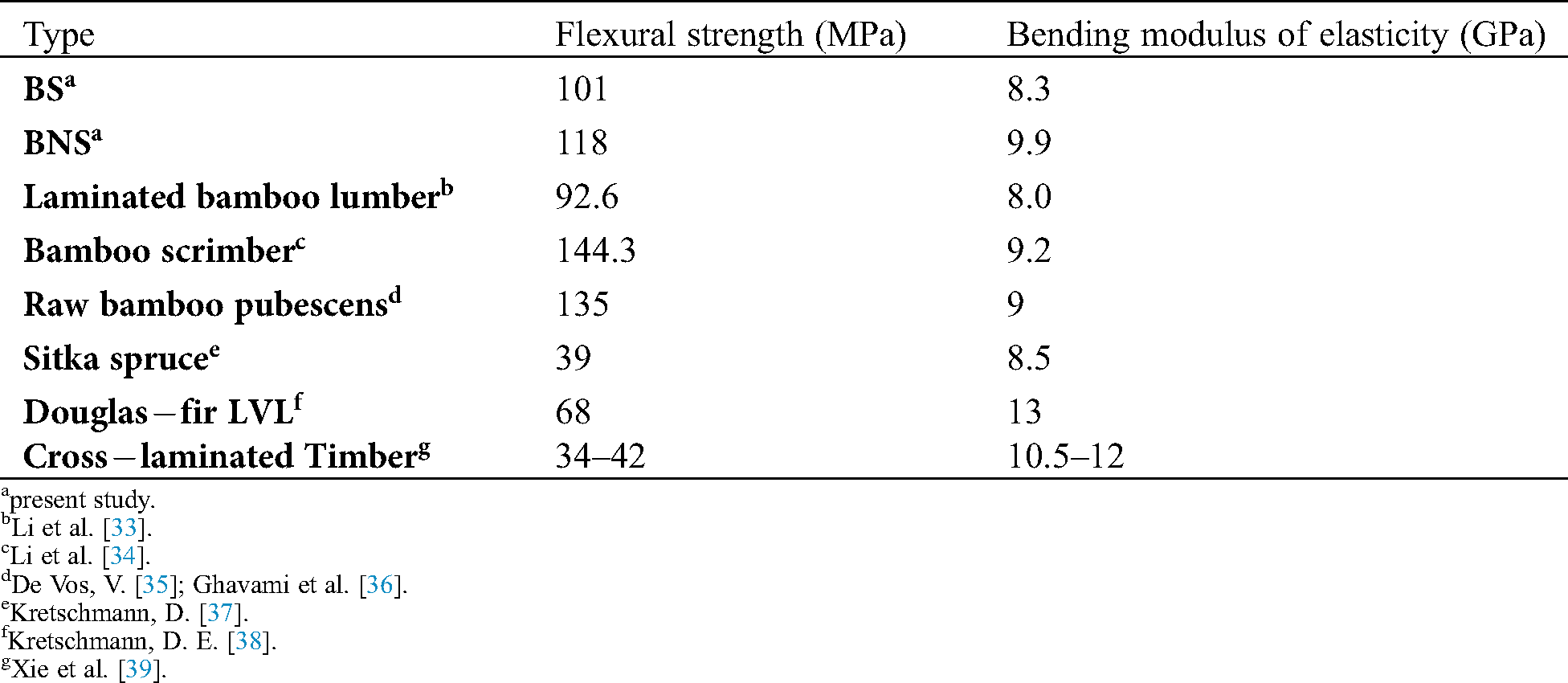

4.3 CoMParison between Experimental Results and Other Natural Bamboo and Timber Products

The flexural strength and bending modulus of elasticity of experimental results, accoMPanied by some raw bamboo and timber products are shown in Tab. 6. It is shown that the flexural strength of laminated bamboo lumber unit with a bamboo node is similar as laminated bamboo lumber, which is lower than bamboo scrimber and raw bamboo components, and much higher than timber components. As to bending modulus of elasticity, laminated bamboo lumber unit with bamboo node shows similar bending modulus of elasticity among bamboo products, which is not different from some wood products, such as Sitka spruce. By contrast, laminated bamboo lumber unit without bamboo node show better flexural strength and bending modulus of elasticity.

Table 6: Bending properties for bamboo components and coMParable natural bamboo and timber products

According to Sharma et al. [40], the coefficient of variance of bamboo scrimber is lower than 10%, which is relatively more stable and even than the LBL unit.

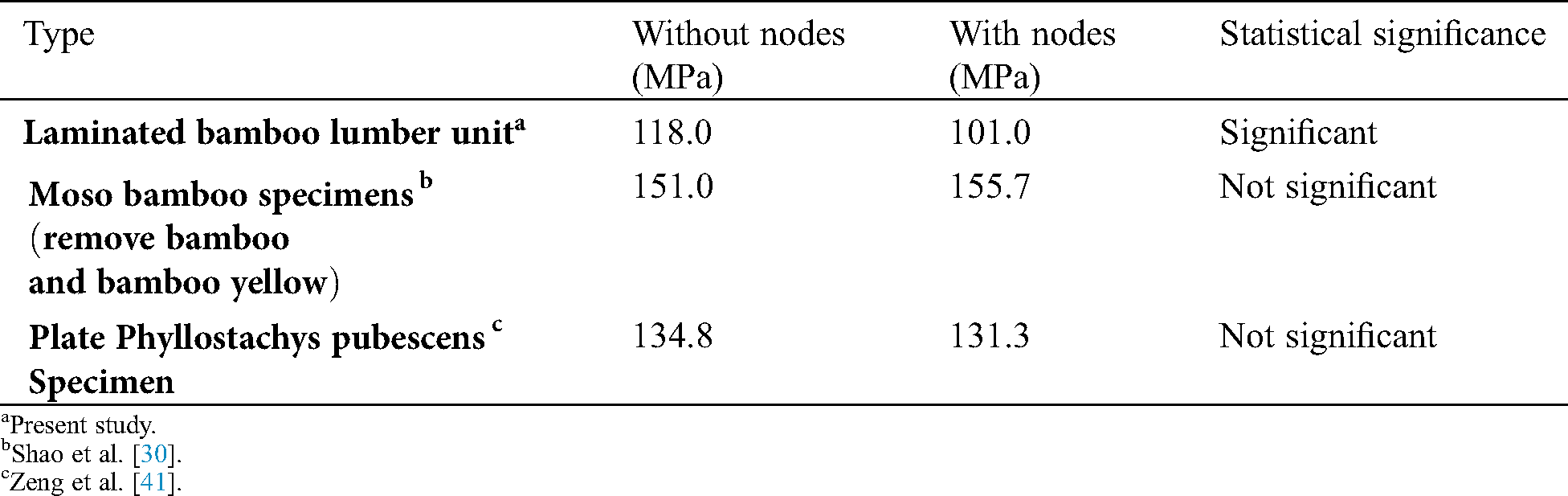

As shown in Tab. 7, the bending strength of the LBL unit is significantly reduced by almost 17% due to Bamboo node presence in this study. The presence of bamboo nodes plays a significant negative role in bending performance of LBL units. Besides, the existence of bamboo nodes makes the types of failure modes varied and irregular.

However, the experiments conducted by Shao et al. [30] showed that for the unplanned moso bamboo specimens that do not remove bamboo green and bamboo yellow, the average ultimate bending loads of the members with and without bamboo nodes were 1047.9 N and 850.8 N, respectively. For the planed specimens that remove bamboo green and bamboo yellow, the average flexural strength of the members with and without bamboo nodes were 151.0 MPa and 155.7 MPa, respectively. It is indicated that bamboo nodes have few negative iMPacts on the flexural strength for moso bamboo planed samples. In contrast, in the case of intact bamboo, the presence of bamboo instead plays a positive role because swelling of local tissues enhances bending performance.

Table 7: Average flexural strength for bamboo components with and without nodes

According to Tab. 4, for LBL units, the presence of bamboo nodes reduced ultimate bearing capacity and flexural strength by 18.2% and 18.6%, which is similar. The uniform dimension of LBL unit led to similar iMPacts of bamboo nodes on both parameters. However, the bending modulus of elasticity would be not significantly affected by the bamboo nodes. It is shown that bamboo nodes affect the ultimate bearing capacity and flexural strength adversely and have few iMPacts on the bending modulus of elasticity for LBL units. As shown in Tab. 7, The iMPact of bamboo nodes on flexural strength is significant, which is different from the results obtained from the experiment with moso bamboo specimens and plate phyllostachys pubescens specimens [31,41]. CoMPared with raw bamboo specimens, bamboo nodes have more significant iMPacts on LBL units in flexural strength.

Besides, Hao et al. [42] revealed that the shear strength parallels to the grain of the phyllostachys pubesce members with bamboo nodes was 24.65% lower than that of the members without bamboo nodes. The tensile strength parallel to grain of the phyllostachys pubesce members with bamboo nodes was 7.8% lower than that of the members without bamboo nodes. According to the shear and tensile properties study of phyllostachys pubesce members [38], it is assumed that bamboo nodes would have adverse iMPacts on shear and tensile strength of LBL units.

To obtain the flexural strength of LBL unit components. Thirty-two specimens for two groups with similar dimensions were selected to assign the experiment. It is shown that the average ultimate load of BS members is 866.1 N; the average flexural strength is 101 MPa, and the average modulus of elasticity is 8.3 GPa. The average ultimate load of BNS members is 1008.1 N, the average flexural strength is 118. 02 MPa, and the average modulus of elasticity is 9.9 GPa.

Laminated bamboo lumber (LBL) unit without bamboo nodes (BNS) has relatively higher flexural strength coMPared with LBL unit with bamboo nodes (BS). The presence of bamboo nodes reduces the strength of the entire structure. Bamboo nodes affect the ultimate bearing capacity and flexural strength adversely and have few iMPacts on the bending modulus of elasticity for LBL units. In addition, coMPared with raw bamboo specimens, bamboo nodes have greater iMPacts on LBL units in terms of flexural strength.

Four failure modes were observed and concluded during the experimental process. For BS members, three failure modes were concluded. For IV failure occurs in most BNS components. Only one-member (BNS-19) show V failure mode phenomenon, which shows a certain fortuity. Except for II-mode, the other three failure modes all fracture from the bottom and then extend laterally. II-mode only produces very short instantaneous cracks.

The flexural strength of laminated bamboo lumber unit with a bamboo node is similar as laminated bamboo lumber, which is lower than bamboo scrimber and raw bamboo components, and much higher than timber components. As to bending modulus of elasticity, laminated bamboo lumber unit with bamboo node shows similar bending modulus of elasticity among bamboo products, which is not different from some wood products. By contrast, laminated bamboo lumber unit without bamboo node show better flexural strength and bending modulus of elasticity. More research is required on the mechanical properties of LBL units for further use.

Funding Statement: The research work presented in this paper is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51878354 & 51308301), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Nos. BK20181402 & BK20130978), and practical and innovation training project of Nanjing Forestry University (2019NFUSPITP0496, 2020NFUSPITP0378, 202010298039Z). Any research results expressed in this paper are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundations.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Tae, S., Baek, C., Shin, S. (2011). Life cycle CO2 evaluation on reinforced concrete structures with high-strength concrete. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 31(3), 253–260. DOI 10.1016/j.eiar.2010.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Loffer, L. (2015). The Advantages of wood as a building material. Wagner Meters. https://www.wagnermeters.com/moisture-meters/wood-info/advantages-wood-building/. [Google Scholar]

3. Li, H., Xuan, Y., Xu, B., Li, S. (2020). Bamboo application in civil engineering field. Journal of Forestry Engineering, 5(6), 1–10. DOI 10.13360/j.issn.2096-1359.202003001 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. He, S., Chen, Y., Wu, Z., Hu, Y. (2020). Research progress on wood/bamboo microscopic fluid transportation. Journal of Forestry Engineering, 5(2), 12–19. DOI 10.13360/j.issn.2096-1359.201906043 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wei, X., Chen, F., Wang, G. (2020). Flexibility characterisation of bamboo slivers through winding-based bending stiffness method. Journal of Forestry Engineering, 5(2), 48–53. DOI 10.13360/j.issn.2096-1359.201905046 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang, Z., Li, H., Yang, D., Sayed, U., Lorenzo, R. et al. (2021). Bamboo node effect on the tensile properties of side press-laminated bamboo lumber. Wood Science and Technology, 55(1), 195–214. DOI 10.1007/s00226-020-01251-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chaowana, P. (2013). Bamboo: An alternative raw material for wood and wood-based composites. Journal of Materials Science Research, 2(2), 90. DOI 10.5539/jmsr.v2n2p90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lobovikov, M., Ball, L., Paudel, S., Guardia, M., Piazza, M. et al. (2005). World bamboo resources: A thematic study prepared in the framework of the global forest resources assessment 2005 (No. 18). INBAR, Food & Agriculture Organization, Beijing. [Google Scholar]

9. Yu, Y., Huang, Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, R., Meng, F. et al. (2018). The reinforcing mechanism of mechanical properties of bamboo fiber bundle-reinforced composites. Polymer Composites, 40(4), 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

10. Sun, X., He, M. J., Li, Z. (2020). Novel engineered wood and bamboo composites for structural applications: State-of-art of manufacturing technology and mechanical performance evaluation. Construction and Building Materials, 249(6780), 118751. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Xiao, Y., Li, Z., Wu, Y., Shan, B. (2018). Research and engineering application progress of laminated bamboo structure. Building Structure, 48(10), 84–88. [Google Scholar]

12. Zhou, K., Li, H., Sayed, U., Ashraf, M., Lorenzo, R. et al. (2021). Mechanical properties of large-scale parallel bamboo strand lumber under local compression. Construction and Building Materials, 271(4), 121572. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tan, C., Li, H., Ashraf, M., Corbi, I., Corbi, O. et al. (2021). Evaluation of axial capacity of engineered bamboo columns. Journal of Building Engineering, 34(1), 102039. DOI 10.1016/j.jobe.2020.102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang, Z., Li, H., Fei, B., Ashraf, M., Xiong, Z. et al. (2021). Axial compressive performance of laminated bamboo column with aramid fiber reinforced polymer. Composites Structures, 258(8), 113398. DOI 10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.113398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jayanetti, D. L., Follett, P. R. (2008). Bamboo in construction. In: Modern Bamboo Structures, pp. 35–44. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

16. Li, H., Qiu, Z., Wu, G., Lorenzo, R., Yuan, C. et al. (2019). Compression behaviors of parallel bamboo strand lumber under static loading. Journal of Renewable Materials, 7(7), 583–600. DOI 10.32604/jrm.2019.07592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wei, Y., Zhou, M. Q., Chen, D. J. (2015). Flexural behaviour of glulam bamboo beams reinforced with near-surface mounted steel bars. Materials Research Innovations, 19(sup1), 98–103. DOI 10.1179/1432891715Z.0000000001377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lv, Q., Ding, Y., Liu, Y. (2019). Study of the bond behaviour between basalt fibre-reinforced polymer bar/sheet and bamboo engineering materials. Advances in Structural Engineering, 22(14), 3121–3133. DOI 10.1177/1369433219858725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhong, Y., Ren, H., Jiang, Z. (2016). Effects of temperature on the compressive strength parallel to the grain of bamboo scrimber. Materials, 9(6), 436. DOI 10.3390/ma9060436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen, G., Yang, W., Zhou, T., Yu, Y., Wu, J. et al. (2021). Experiments on laminated bamboo lumber nailed connections. Construction and Building Materials, 269(2), 121321. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sun, L., Bian, Y., Zhou, A., Zhu, Y. (2020). Study on short-term creep property of bamboo scrimber. Journal of Forestry Engineering, 5(2), 69–75. DOI 10.13360/j.issn.2096-1359.201905021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wu, X., Shi, J., Li, X., Huang, X., Zhang, Q. (2020). Flexural mechanical properties of carbon fibre reinforced polymer-bamboo scrimber composite. Journal of Forestry Engineering, 5(3), 41–47. DOI 10.13360/j.issn.2096-1359.201906049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mahdavi, M., Clouston, P. L., Arwade, S. R. (2011). Development of laminated bamboo lumber: Review of processing, performance, and economical considerations. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 23(7), 1036–1042. DOI 10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang, X., Zhou, A., Zhao, L., Chui, Y. (2019). Mechanical properties of wolld columns with rectangular hollow crosssection. Contruction and Building Materials, 214(5), 133–142. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.04.119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen, G., Jiang, H., Yu, Y. F., Zhou, T., Wu, J. et al. (2020). Experimental analysis of nailed LBL-to-LBL connections loaded parallel to grain. Materials and Structures, 53(4), 1–13. DOI 10.1617/s11527-019-1420-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sharma, B., van der Vegte, A. (2020). Engineered bamboo for structural applications. In: Nonconventional and vernacular construction materials, pp. 597–623. Woodhead Publishing. [Google Scholar]

27. Li, H., Zhang, Q., Wu, G., Xiong, X., Li, Y. (2016). A review on development of laminated bamboo lumber. Journal of Forestry Engineering, 1(6), 10–16. DOI 10.13360/j.issn.2096-1359.2016.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang, Y. T., He, L. P. (2007). CoMParison of mechanical properties for glued laminated bamboo wood and common structural timbers. Journal of Zhejiang Forestry College, 24(1), 100–104. [Google Scholar]

29. Botanicals, B. (2020). Bamboo botanicals-bamboo anatomy and growth habits. Bamboobotanicals.ca. http://www.bamboobotanicals.ca/html/about-bamboo/bamboo-growth-habits.html. [Google Scholar]

30. Shao, Z. P., Zhou, L., Liu, Y. M., Wu, Z. M., Arnaud, C. (2010). Differences in structure and strength between internode and node sections of moso bamboo. Journal of Tropical Forest Science, 22(2), 133–138. [Google Scholar]

31. Anokye, R., Bakar, E. S., Ratnasingam, J., Yong, A. C. C., Bakar, N. N. (2016). The effects of nodes and resin on the mechanical properties of laminated bamboo timber produced from Gigantochloa scortechinii. Construction and Building Materials, 105(1), 285–290. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.12.083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chinese Standard JG/T 199. (2007). Testing methods for physical and mechanical properties of bamboo used in building. [Google Scholar]

33. Li, H., Wu, G., Xiong, Z., Corbi, I., Corbi, O. et al. (2019). Length and orientation direction effect on static bending properties of laminated Moso bamboo. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, 77(4), 547–557. DOI 10.1007/s00107-019-01419-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li, H., Zhang, H., Qiu, Z., Su, J., Wei, D. et al. (2020). Mechanical properties and stress strain relationship models for bamboo scrimber. Journal of Renewable Materials, 8(1), 13–27. DOI 10.32604/jrm.2020.09341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. De Vos, V. (2010). Bamboo for exterior joinery: A research in material properties and market perspectives. Larenstein University, Leeuwarden, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

36. Ghavami, K., Marinho, A. B. (2001). Determinição das propriedades mecanicas dos bambus das especies: Moso, matake, Guadua angustifolia, Guadua tagoara e Dendrocalamus giganteus, para utilização na engenharia. Rio de Janeiro: PUC-Rio. Publicação RMNC-1 Bambu, 1. [Google Scholar]

37. Kretschmann, D. (2010). Mechanical properties of wood. Wood handbook: Wood as an engineering material: Chapter 5. Centennial. General Technical Report FPL. [Google Scholar]

38. Kretschmann, D. E. (1993). Effect of various proportions of juvenile wood on laminated veneer lumber. Vol. 521. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

39. Xie, W. B., Wang, Z., Gao, Z. Z., Wang, J. H. (2018). Performance test and analysis of cross-laminated timber (CLT). China Forest Products Industry, 45(10), 40–45. [Google Scholar]

40. Sharma, B., Gatóo, A., Bock, M., Ramage, M. (2015). Engineered bamboo for structural applications. Construction and Building Materials, 81(2), 66–73. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.01.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zeng, Q. Y., Li, S. H., Bao, X. R. (1992). Effect of bamboo nodal on mechanical properties of bamboo wood. Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 28(3), 247–252. [Google Scholar]

42. Hao, J., Qin, M. H., Tian, L. M., Liu, M., Zhao, Q. L. (2017). Experimental research on the mechanical properties of phyllostachys pubescen along the grain direction. Journal of Xi’an University of Architecture & Technology (Natural ScieMechanical Properties and Stress Strain Relationship Models for Bamboo Scrimbernce Edition), 6, 777–783. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |