Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Facile Preparation of Dopamine-Modified Magnetic Zinc Ferrite Immobilized Lipase for Highly Efficient Synthesis of OPO Functional Lipid

1 College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering, Guangzhou, 510225, China

2 Guangzhou Vocational College of Science and Technology, Guangzhou, 510450, China

* Corresponding Author: Xue Huang. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2023, 11(5), 2301-2319. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2023.025888

Received 03 August 2022; Accepted 08 October 2022; Issue published 13 February 2023

Abstract

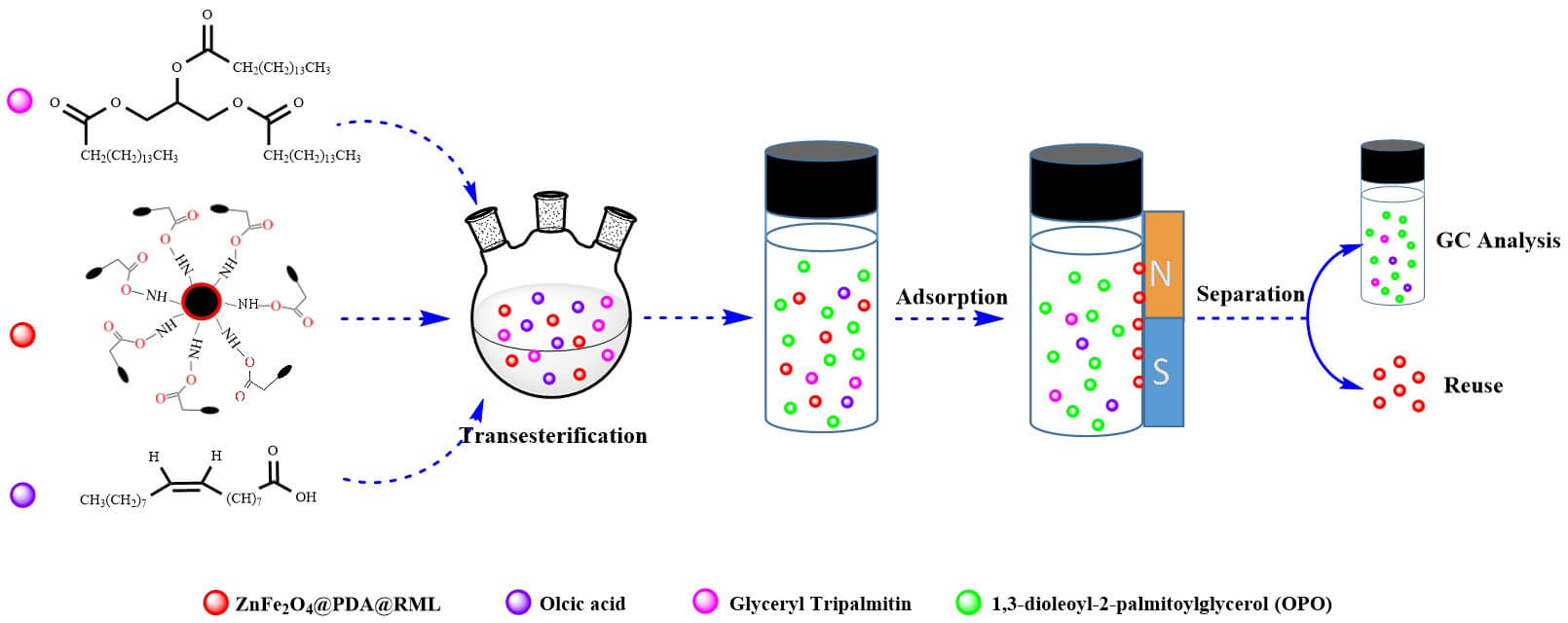

1,3-Dioleoyl-2-palmitoylglycerol (OPO) has been a hotspot of functional oils research in recent years, but due to the high cost of sn-1,3 specific lipase in enzymatic synthesis and the lack of biocatalyst stability, large-scale industrial application is difficult. In this study, the prepared magnetic ZnFe2O4 was functionalized with dopamine to obtain ZnFe2O4@PDA, and the nano-biocatalyst ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was prepared by immobilizing sn-1,3 specific lipase of Rhizomucor miehei lipase (RML) via a cross-linking method. The existence of RML on ZnFe2O4@PDA was confirmed by XRD, FTIR, SEM, and TEM. This strategy proved to be simple and effective because the lipase immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles could be quickly recovered using external magnets, enabling reuse of the lipase. The activity, adaptability to a high temperature, pH value, and operational stability of immobilized RML were superior to those of free RML. After optimizing the synthesis conditions, the OPO yield was 42.78%, and the proportion of PA at the sn-2 position (PA-Sn2) was 54.63%. After the first four cycles, the activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was not significantly affected. The magnetically immobilized lipase has good thermal stability, long-term storage stability, reusability, and high catalytic activity. It can be used as a green and efficient biocatalyst to synthesize the OPO functional lipid.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The World Health Organization confirms that breast milk is the best nutritional food for babies [1]. The sn-2 position of triglycerides (TAGs > 98%) in human milk fat is mainly saturated fatty acids, and this unique structure and composition have prompted much research on alternatives to human milk fat [2]. With the continuous improvement of the quality requirements for infant formula milk powder, OPO has also attracted much attention as one of the leading nutritional components of human milk fat. Enzymatic synthesis of OPO requires the selection of sn-1,3 specific lipase as a catalyst to catalyze the esterification reaction between acyl donors and TAGs [3]. Rhizobium miehei lipase (RML) can catalyze hydrolysis, acid hydrolysis, esterification, and trans-esterification reactions [4]. Moreover, RML is favored in OPO synthesis because of its sn-1,3 specificity [5]. The high sensitivity, poor stability, and difficulty of recovery and reusability of natural enzymes hinder their practical application [6,7]. It is possible to overcome these problems by immobilizing the enzymes onto the substrates [8]. Therefore, it is essential to develop novel immobilized lipases for OPO synthesis.

Commonly used immobilization technologies include physical and chemical methods [9]: the physical processes include the adsorption method and embedding method; the chemical processes include cross-linking and covalent bonding methods. The covalent bond method is the most widely used method to immobilize enzymes on carriers, preventing the enzyme from leaching out from the carrier surface [10]. Carriers and scaffolds for immobilizing enzymes [11–14] include carbon nanomaterials, mesoporous materials, magnetic particles, silica, polysaccharides, and resins. Magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4) have the advantages of recyclability, good biocompatibility, stability, large surface area, and superparamagnetic properties [15].

However, the problems of agglomeration and easy oxidation of Fe3O4 limit its application [16]. The surface functionalization of Fe3O4 can effectively overcome the above shortcomings and provide an adhesion layer for enzyme immobilization [17]. The surfaces of magnetic particles can be functionalized with polysaccharides, carbon, polydopamine, and silica [18]. Although many pioneering works have improved the stability and recyclability of enzymes, it is still necessary to study effective substrates and technologies for the immobilization of high-performance enzymes. Dopamine contains catechol and the amine group, which efficiently interact with metal oxide nanoparticles [19]. The oxidized dopamine monomer self-polymerizes under weak alkaline conditions to form polydopamine. The residual quinones and catechol groups on the surface after polymerization are reactive toward nucleophiles such as thiol and amine groups. These lipases are covalently immobilized on polydopamine through Schiff base formation and Michael addition reactions [20]. Therefore, it is essential to study dopamine-modified magnetic zinc ferrite immobilized lipase to advance the efficient synthesis of the OPO functional lipid.

In this study, magnetic metal oxide nanoparticles were prepared using the solvothermal method, and polydopamine was used to graft and fix RML to develop nano-biocatalysts. The hydrothermal method was used to synthesize magnetic ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles to realize high magnetization of high-efficiency recovery. The activity of immobilized RML and lipase loading conditions (pH values, temperatures, times, and dosage of lipase solution) were optimized. The operational stability of free RML and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML in storage, thermal stability, acid–base stability, and reusability were also investigated. The results show that the synthesized ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML exhibited excellent heat resistance and good reusability, and it was able to withstand harsh environmental conditions (storage stability and pH values). The catalytic reaction conditions were optimized, and the effect of recycling on OPO yield was investigated. It is exciting to find that ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML can improve the catalytic efficiency and reuse efficiency of OPO synthesis, which has the potential to be used in batch or continuous production processes of OPO.

Iron trichloride hexahydrate, zinc chloride, sodium acetate trihydrate, ethylene glycol, ethyl alcohol, hydrochloric acid, sodium chloride, sodium hydroxide, isopropanol, oleic acid (OA, 99%), palmitic acid (PA, 97%), n-hexane, acetic acid, ether, methanol, anhydrous sodium sulfate, calcium chloride, and sodium cholate were obtained from Guangzhou Jinyuan Chemical Co., Ltd., China. Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris), dopamine, N-hydroxy succinimide (NHS), gum arabic, p-nitrophenyl palmitate, p-nitrophenol, and n-hexane (chromatographically pure) were obtained from Shanghai McLean Biotech Co., Ltd., China. Polyethylene glycol (PEG-400) and glyceryl tripalmitate (PPP, 85%) were obtained from Hefei Bomei Biotech Co., Ltd., China. Rhizomucor miehei lipase (RML, food grade, 4.3 mg·mL−1) was purchased from Beijing Gaoruisen Technology Co., Ltd., China. Bovine serum albumin, Coomassie brilliant blue (G250), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC), Triton X-100, and porcine pancreatic lipase (PPL) were obtained from Sigma. The reagents purchased from Sigma were of biological grade.

2.2 Synthesis of ZnFe2O4 Nanoparticles

Magnetic nanoparticles of ZnFe2O4 were prepared via the solvothermal method [21] with some modifications of chloride salts of Fe3+ and Zn2+. First, 1.35 g FeCl3·6H2O, 0.34 g ZnCl2, 0.5 g PEG-400, and 2.72 g NaAc·3H2O were placed in a beaker, and 30 mL ethylene glycol was added under even magnetic stirring at 50°C. The mixture was transferred to a polytetrafluoroethylene-lined autoclave, heated at 180°C for 18 h, and cooled to 25°C in a drying oven. The crude ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles were quickly separated from the solution using a magnet, washed with deionized water, and dried in a vacuum at 50°C for 8 h. The ZnFe2O4 was ground to powder for use.

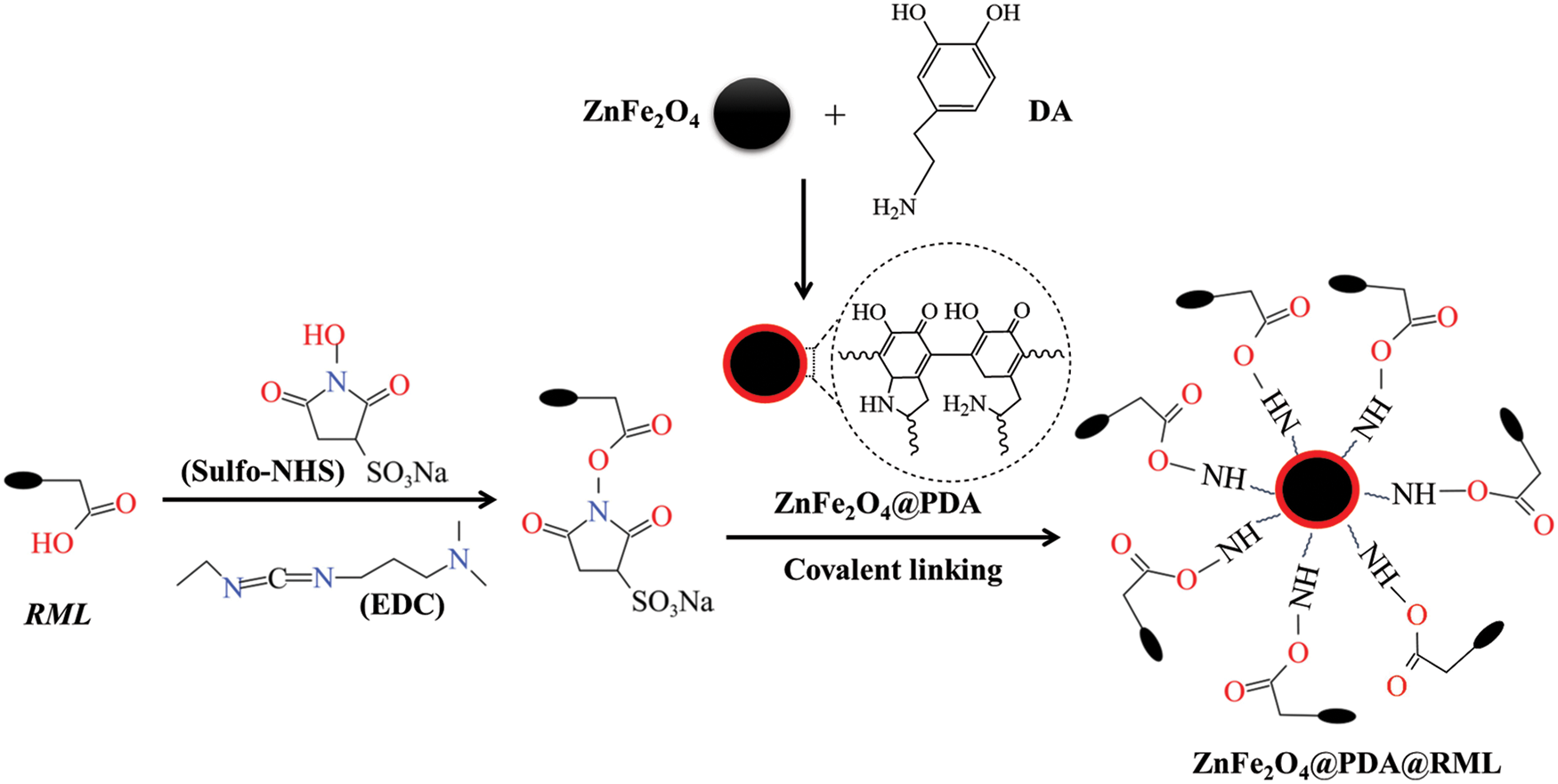

First, 0.1 g ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles and 1.0 g PEG-400 were dispersed in 50 mL Tris-HCl buffer (50 mmol·L−1, pH 8.5), stirred well, and sonicated for 30 min. After the ultrasound, 0.1 g of dopamine (DA) was slowly added to the suspension and mechanically stirred at 300 r·min−1 for 3 h. By self-polymerizing dopamine in alkaline conditions, nanoparticles coated with polydopamine (PDA) were formed [22]. After the reaction, the separated ZnFe2O4@PDA nanoparticles were washed with deionized water. The final products were freeze-dried and stored at 4°C. The mechanism is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Mechanism of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

2.4 Immobilization of RML on ZnFe2O4@PDA

First, 0.1 g ZnFe2O4@PDA was dispersed in 50 mL of pH 7 phosphate buffer solution (0.9% NaCl) and sonicated for 10 min to form a ZnFe2O4@PDA suspension. Next, 1 mg·ml−1 EDC/NHS crosslinking agents was added to the suspension and stirred evenly. Subsequently, 1 mL of RML lipase solution was slowly added and stirred for 5 h at 40°C and 250 r·min−1. The carboxyl group on RML is first combined with EDC to generate an unstable O-acylurea intermediate, which can be converted to a stable succinimide ester by adding NHS. The succinimide ester reacts with an amino group on the ZnFe2O4@PDA surface to form an amide bond (Fig. 1) [23,24]. The ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML nanoparticles were then magnetically separated and washed with phosphate buffer to remove any unreacted lipase. After freeze-drying for 8 h, the final products were stored at 4°C.

The amount of the immobilized RML was calculated using formula (1).

where W is the amount of RML immobilized onto ZnFe2O4@PDA (mg·g−1); C0 and C are the initial and final concentrations of RML (mg·mL−1); V is the volume of the solution (L); and M is the mass of ZnFe2O4@PDA (g); 1000 is the conversion ratio between mL and L. Bradford’s method was used to measure the protein content before and after the immobilization processes to check the immobilization yield [25].

2.5 Hydrolytic Activity of Free and Immobilized RML

The lipase activity was evaluated via the yield of p-nitrophenol (p-N) from the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl palmitate (p-NP). The equation of the p-N standard curve was y = 16.4214x + 0.0329, r = 0.9954. First, 0.1 mL of RML (or 5 mg of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML), 1 mL of 1 mmol·L−1 p-NP isopropanol solution, and 4 mL of 0.1 mol Tries-HCl buffer (0.80 wt% Triton x-100, 0.12 wt% gum arabic) at pH 8 were added to a tube. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min, and a 2 mL ethanol solution was added to terminate the reaction. The solution was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min and 1 mL of supernatant was taken and diluted with purified water. The absorbance at 410 nm was measured with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to determine the generated concentration of p-N based on a previously established calibration curve from p-N standard solutions [26]. The lipase activity (U) of one unit was defined as the amount of free RML (or immobilized RML) to generate 1.0 μmol of p-N at 37°C for 1 min under these experimental conditions, which was calculated using formula (2):

where 1000 is the conversion ratio between mmol and μmol; V is the total volume of the reaction system (L); t is reaction time (min); y is the absorbance value; b and K are the intercept and the slope of the standard curve; m is the quality of the enzyme (g).

2.6 Characterization of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

SEM was applied to study the morphology of the sample using the EVO 18 (Zeiss, Germany). The pieces were coated out of gold. TEM images of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML were taken using a JEOL JEM-2100 (JEM, Japan). XRD testing of the crystal structures of the samples was done with an Empyrean diffractometer (X’Pert Powder, Holland). FTIR spectra of the samples were also detected using a Spectrum 2000 spectrometer (PerkinElmer, USA). TGA curves were obtained with a TG209F1 thermogravimetric analyzer (Netzsch, Germany). The magnetic properties were measured with a 7404 VSM (Lakeshore, USA).

2.7 Characterization of Enzymatic Properties of Free RML and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

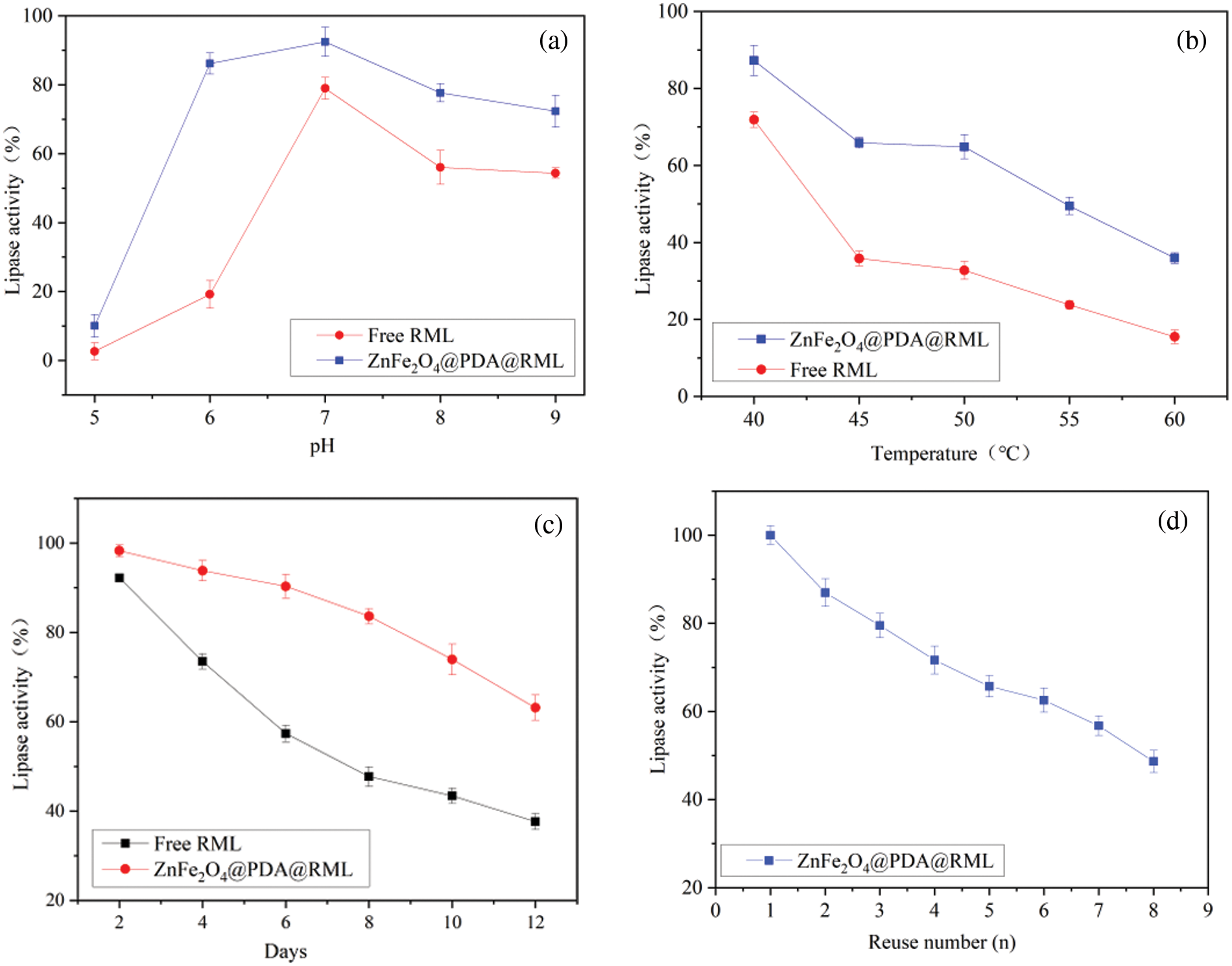

The acid–base stability of the free RML and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was investigated after incubating preparations of different pH values from 5 to 9 in phosphate buffer for 3 h. The magnetically separated ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was washed to remove residual products or unreacted substrates. Lipase activity before incubation was defined as 100% to evaluate the percentage of the remaining activity at different pH values.

The thermal stability analysis of free RML and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was carried out by evaluating the residual activity of RML after incubating in phosphate buffer (pH 7) for 3 h at different temperatures of 40°C to 60°C. The lipase activity obtained before incubation was recorded as 100%.

The lipase activity measured on the first day was defined as 100%. The residual activity was measured every 2 days for 12 days to investigate the storage stability.

2.7.4 Reusability of Immobilized RML

The reusability of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was evaluated by referring to the method in Section 2.5. After each cycle, the magnetically separated ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was washed three times and stored at 4°C. The percentage of remaining activity after each use was evaluated.

2.8 Biochemical Characterization of Immobilized RML

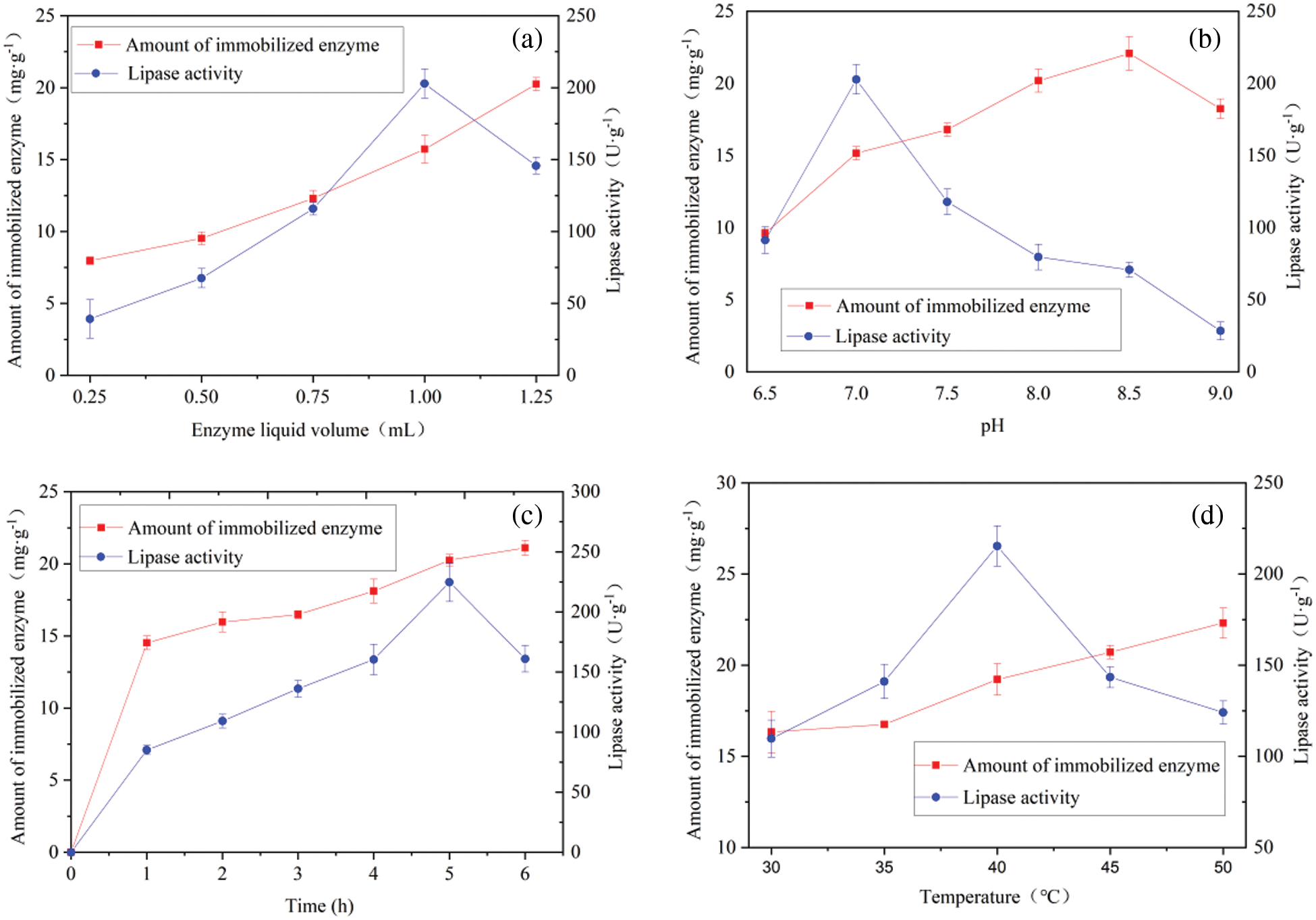

The assay method was used to study the effects of enzyme solution dosage, immobilization time, temperature, and pH value on the activity of immobilized lipase. The impact of enzyme solution dosage was analyzed from 0.25 to 1.25 mL at 40°C for 3 h. The influence of immobilization time between 1 and 6 h was studied after determining the optimal amount of enzyme solution. Under the optimum conditions of enzyme solution and immobilization time, the influence of pH value between 6.5 and 9.0 was studied. Under the optimal conditions of enzyme solution, immobilization time, and pH value, the effect of temperature between 30°C and 50°C was studied.

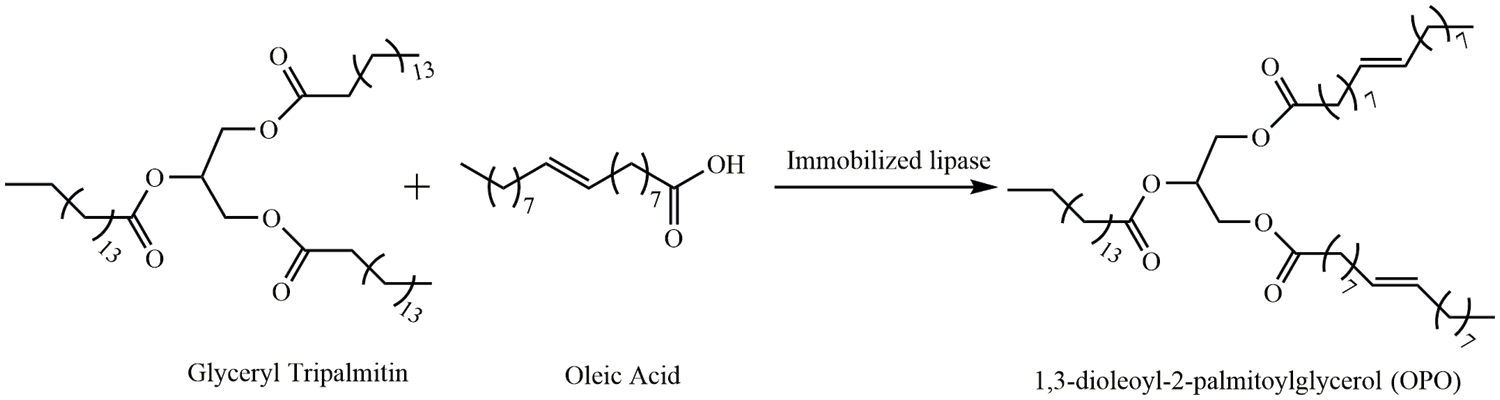

2.9 Enzymatic Synthesis of OPO

PPP (0.12 mmol), OA (0.24–1.2 mmol), and n-hexane (3 mL, CP) were added to the flask, placed in a 50°C water bath to dissolve the substrate fully, and cooled to room temperature, after which ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML (15–45 mg) was added and oscillated evenly. The reaction flask was placed on a shaking table at a specific temperature and an oscillation rate of 150 r·min−1 allowed to react for 9 h. After the reaction, the oil sample and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML were magnetically separated, and the oil sample was stored at 4°C (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: Synthesis of OPO by immobilized lipase

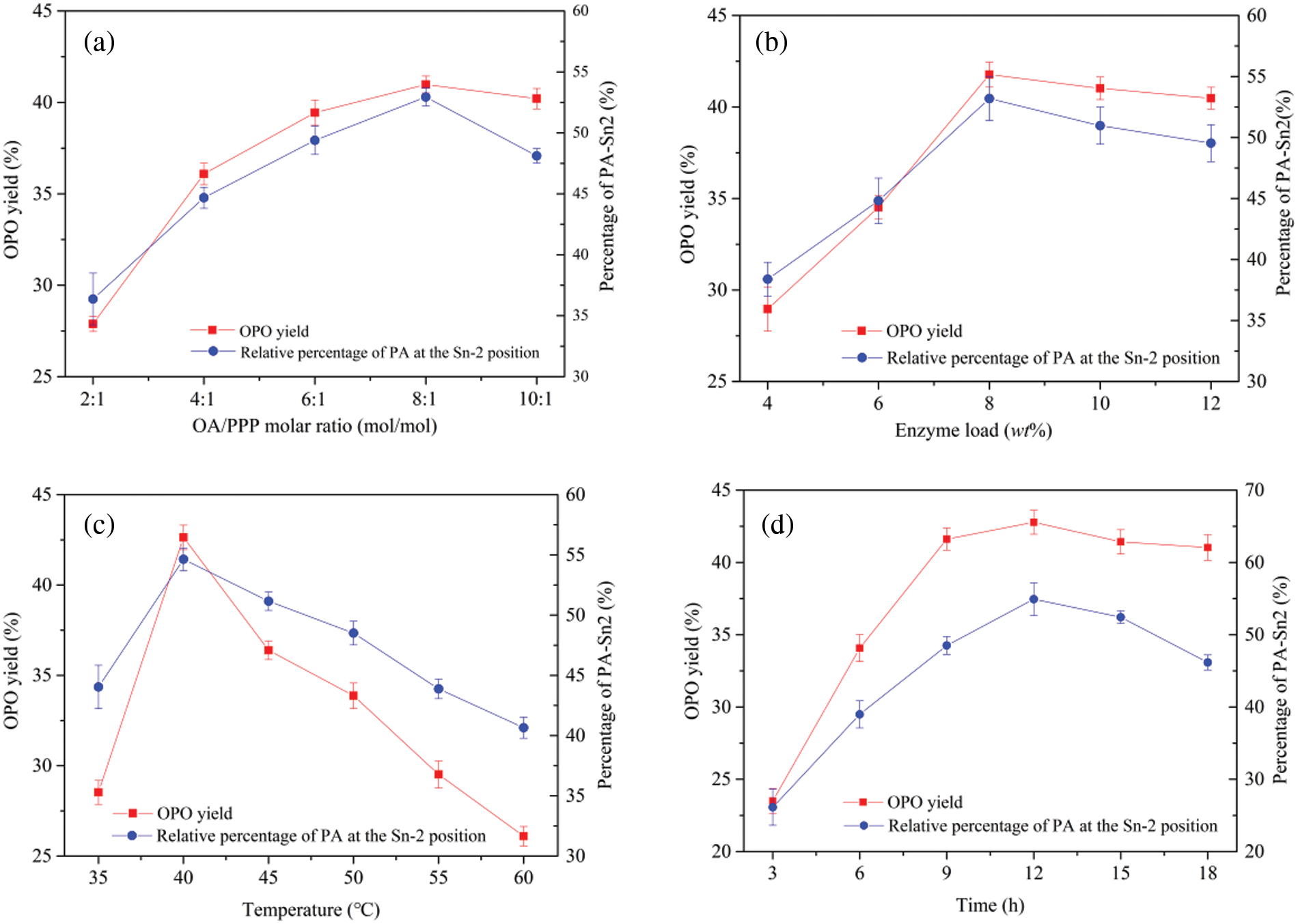

The effects of reaction conditions on the enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of OPO were investigated. The catalytic reactions were assessed using OPO yields and percentage of PA-Sn2, examining the following conditions: temperature of response (35°C, 40°C, 45°C, 50°C, 55°C, and 60°C), molar ratio of substrates (2:1, 4:1, 6:1, 8:1, and 10:1), enzyme load (4%, 6%, 8%, 10%, and 12%) and reaction time (3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 h).

2.10 Analysis and Determination of OPO by GC

2.10.1 Analysis of Triglyceride in Transesterification Products by GC

The triglyceride composition of the transesterification products was detected using an Agilent 7820A gas chromatograph. The parameter settings were as follows: capillary column (DB-1HT, 15 m × 250 μm × 0.10 μm), detector temperature 370°C, injection port temperature 350°C; injection volume 10 μL (split ratio 1:20); nitrogen flow rate 6.5 mL·min−1, airflow rate 400 mL·min−1, hydrogen flow rate 30 mL·min−1. The heating program: the initial column temperature was 200°C for 2 min, and then heated to 350°C at a heating rate of 15 °C·min−1 for 6 min. The triglyceride standard calibration curve was obtained by GC analysis under the above conditions. Quantitative analysis of triglyceride content was accomplished by peak area normalization.

2.10.2 Fatty Acids in Triacylglycerols by GC

1. Fatty acid composition analysis

Preparation of fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) [27]: A certain amount of purified transesterification product was added to the flask and 2 mL of n-hexane was added to dissolve the product, followed by addition of 1 mL of NaOH-methanol solution (2 mol·L−1). The flask was put in a 50°C water bath for 15 min, then placed on a micromixer for 5 min and left to stand until the solution had naturally stratified. The upper organic liquid was taken from the centrifuge tube and 0.5 g anhydrous sodium sulfate was added to remove water. After centrifugation, the organic liquid was taken out and stored at 4°C for testing.

A gas chromatograph (Agilent 7820A GC) equipped with a hydrogen flame ionization detector was used along with a capillary column (DB-WAX, 30 m × 320 μm × 0.25 μm). Quantitative analysis of fatty acid composition was accomplished by peak area normalization.

2. Analysis of the fatty acid composition of sn-2 position:

Preparation of the sn-2 position monoglyceride (2-MAGs): Regiospecific distribution was estimated via the fatty acid composition of 2-MAGs. Frist, 0.1 g OPO was dissolved in 2 mL of Tris-HCl buffer (0.05 mol·L−1, pH 8.0), 2 mL of CaCl2 (2.2 wt%), and 0.2 mL sodium cholate solution (0.1 wt%), and 20 mg porcine pancreatic lipase were successively added while incubating at 40°C for 10 min, after which 1 mL of HCl (6 mol·L−1) and 1 mL of n-hexane were added to terminate the reaction. The mixture was centrifuged at 4000 r·min−1 for 10 min. The upper solution was transferred to a test tube and the 2-MAGs sample was obtained by concentration under nitrogen.

Separation and purification of 2-MAGs by thin-layer chromatography (TLC): The samples were separated and purified on a silica gel G254 TLC plate using a solution of n-hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid (50:50:1, v/v/v) as a developing solvent. The TLC plates were stained with 2,7-dichlorofluorescein (0.2%, w/v) in ethanol, and the 2-MAGs were identified in 254 nm ultraviolet light. The 2-MAGs strip was then scraped and dissolved with n-hexane.

Next, according to the method of methyl esterification in fatty acid composition analysis and the parameters of GC, 2-MAGs were methyl esterified and analyzed by GC. The proportion of PA-Sn2 of the total content PA is an essential indicator for judging the synthesized OPO [28], which was calculated using formula (3):

All experiments were conducted in three parallel replicates and the results were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD).

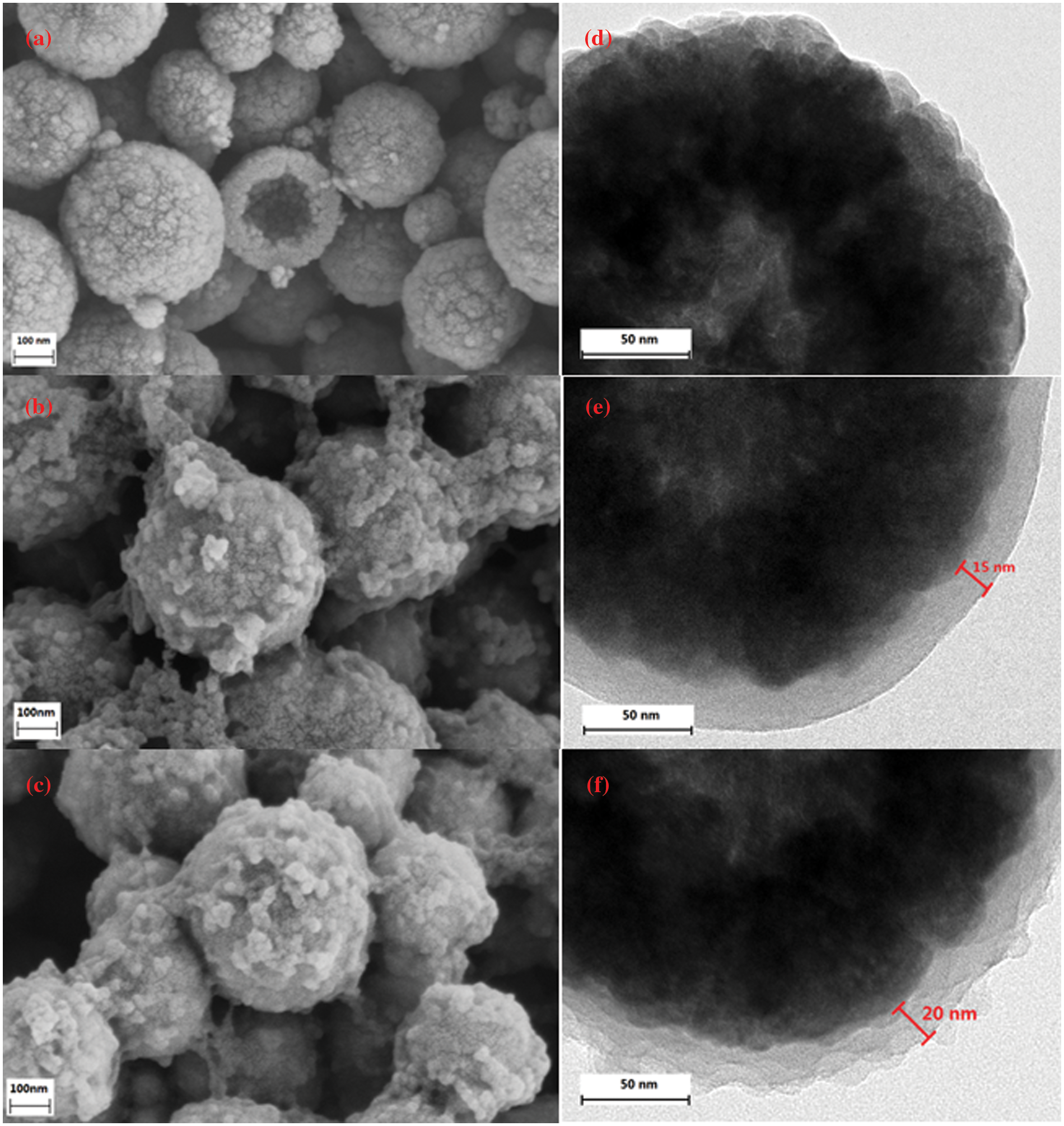

3.1 Characterization of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

SEM and TEM were used to observe the micromorphology of the material. The SEM images of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML are shown in Figs. 2a–2c. The sizes of the three kinds of nanoparticles were not much different, the size was about 250~300 nm, and the ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles showed a hollow spherical structure with a smooth surface (Fig. 2a). The ZnFe2O4@PDA and the ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML presented a globular form (Figs. 2b and 2c). Compared with ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML were denser due to the oxidative self-polymerization of dopamine on ZnFe2O4 in the weak alkali and oxygen atmosphere in the air, forming an adhesive PDA. The formation of sticky PDA made the particles adhere to each other and become dense, thus enhancing the adsorption capacity of ZnFe2O4@PDA for lipase. Figs. 2d–2f illustrate the TEM photos of the ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML, respectively. PDA grafting onto the ZnFe2O4 was confirmed by the thin border of black nanoparticles [29]. The PDA layer thickness was about 15 nm (Fig. 2e). Under the influence of this layer of the PDA, the particles became more compact, but the particle shape of the particles was not changed, which was in line with the SEM observations. The increased particle size illustrated the successful fixing of RML onto the ZnFe2O4@PDA in the TEM image (Fig. 2f).

Figure 2: Illustrates the SEM (a, b, c) and TEM (d, e, f) of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

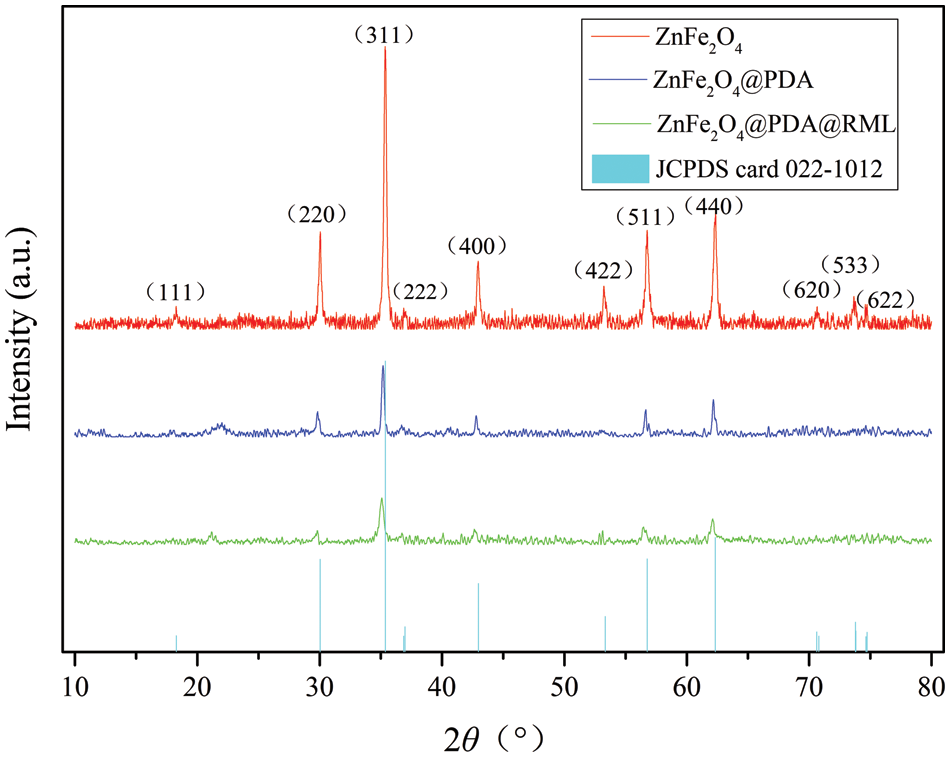

XRD was used to detect the crystal structures of the samples to confirm the structure formation of the magnetic nanoparticles. The XRD patterns of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML are shown in Fig. 3. The formed ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles exhibited well-resolved peaks at 30.04°, 35.37°, 42.97°, 53.33°, 56.77°, 62.33°, 70.622°, and 73.79°, which corresponded to (220), (311), (400), (422), (511), (440), (620), (533), and (622) reflections, respectively (JCPDS card 022–1012), with no extraneous peak, which showed the high purity of the magnetite. ZnFe2O4@PDA and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML had a particular diffraction peak of PDA at 2θ = 21.58°, which showed that PDA successfully modified the surface of ZnFe2O4. In addition, other peak shapes of ZnFe2O4@PDA did not change, and the lattice structure of ZnFe2O4 did not change either. XRD data from ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML showed no significant difference in the crystal structure of ZnFe2O4 after PDA coating and lipase immobilization. However, the peak area of the unique diffraction peak and the characteristic plane of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was decreased compared with ZnFe2O4@PDA due to the masking effect. The results also indirectly prove that ZnFe2O4@PDA had RML successfully fixed on its surface.

Figure 3: XRD patterns of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML, and characteristic peaks of ZnFe2O4

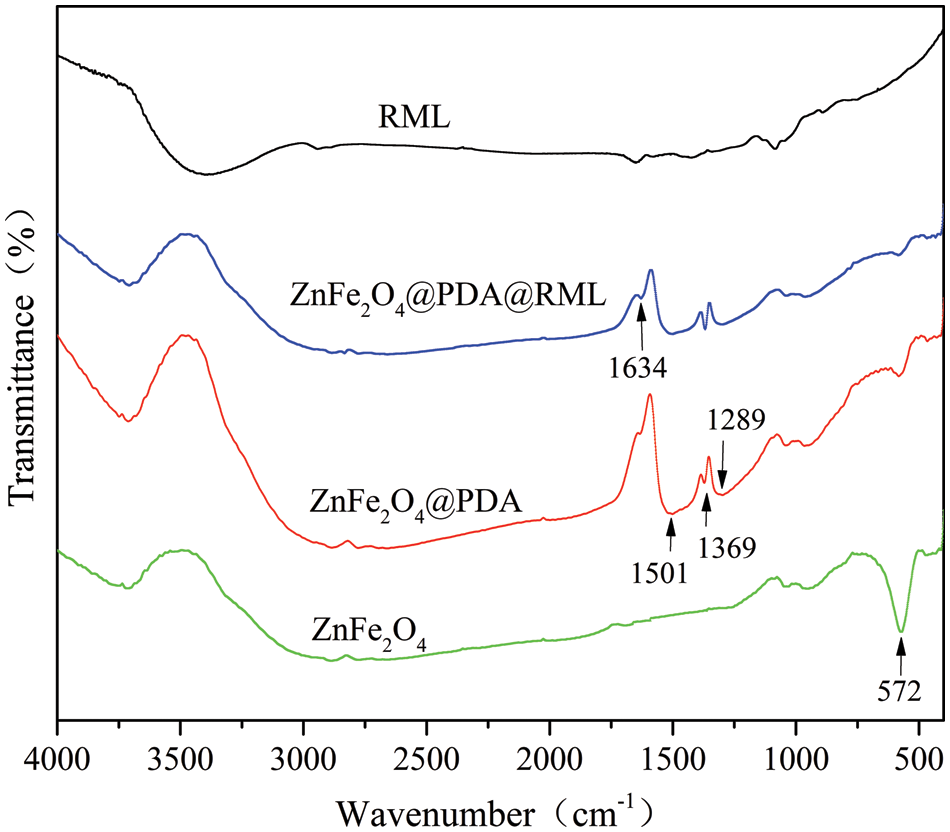

FTIR was used to determine the existence of distinct groups of each product over the RML assembly and modification. Fig. 4 shows the FTIR spectra for free RML, bare ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML recorded between 400 and 4000 cm−1. All samples except RML had a distinct peak at 572 cm−1, attributed to the Fe-O stretching vibration of ZnFe2O4, indicating the existence of ZnFe2O4 magnetic cores in the samples. Compared with ZnFe2O4 particles, a peak at 1289 cm−1 showed a C-O bond, and the in-plane bending vibration peak of C-H at 1369 cm−1. The characteristic peak at 1501 cm−1 corresponds to the skeleton vibration caused by the unique C=C of the benzene ring, indicating the existence of PDA in ZnFe2O4. The amide regions (I and II bands) are the FTIR spectrum recognition regions, which can confirm the main-chain conformation of the protein [30]. In the ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML sample, the absorption peak caused by the C=O stretching vibration (amide I) was at 1634 cm−1. The results of the FTIR showed that the magnetically immobilized enzyme was successfully prepared.

Figure 4: FTIR spectra of RML, ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

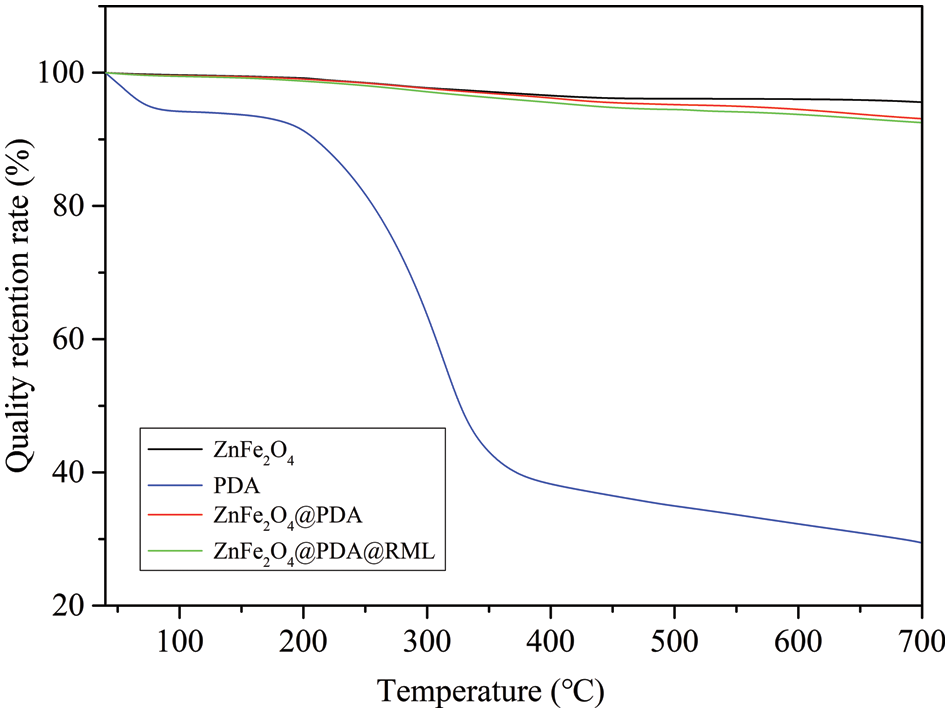

Fig. 5 shows the thermogravimetric curves for ZnFe2O4, PDA, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML. Weight loss (%) was used in this study to determine the PDA coating weight and the amount of immobilized lipase. In the temperature range of 40°C~700°C, ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML were 95.58%, 93.10%, and 92.51%, respectively, while the retention rate of PDA was only 29.42%. The weight loss of PDA was higher, which showed that the prepared ZnFe2O4@PDA and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML were more heat-resistant than pure PDA. ZnFe2O4 was 5.14% at 450°C due to the release of adsorbed water. ZnFe2O4@PDA was about 6.9% at 700°C due to the release of water and PDA decomposition. The content of PDA in the ZnFe2O4@PDA was about 2.48% (24.8 mg PDA/g ZnFe2O4). In addition, according to the TGA result of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML, the amount of the immobilized lipase in ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was calculated to be 0.59% (5.9 mg lipase/g carrier), which along with the results obtained by Bradford’s method, proved that the PDA was successfully coated on the ZnFe2O4 particles and RML was successfully immobilized on ZnFe2O4@PDA.

Figure 5: TGA thermograms of PDA, ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

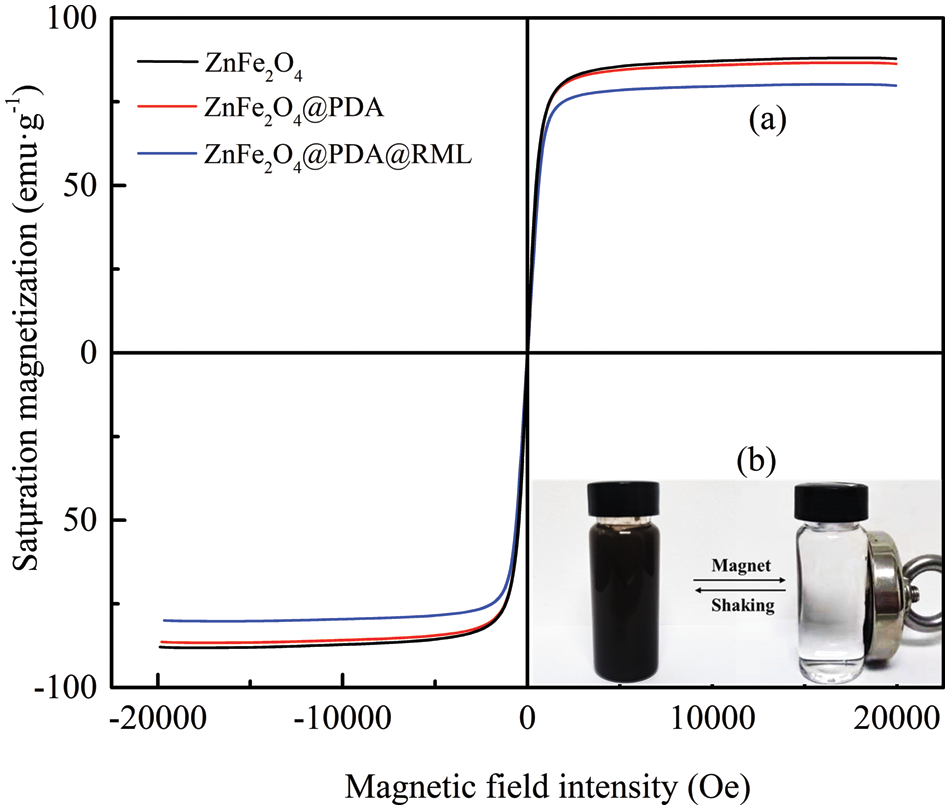

The magnetization curves of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML are shown in Fig. 6a. The saturation magnetization of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML were 87.9, 86.3, and 79.8 emu·g−1, respectively. The saturation magnetization of immobilized enzyme materials synthesized in other literature [31,32] is 34.5 and 30.73 emu·g−1. The ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML has obvious advantages of being recycled. After successively coating PDA and immobilizing the enzyme, the saturation magnetization of magnetic particles decreased gradually. However, ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML could still be rapidly separated by an external magnet. Fig. 6b shows that the ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML could quickly be collected from the solution using an external magnet. The magnetic nanoparticles are rapidly redispersed under slight shaking when the magnetic field disappeared. These results indicate that ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML is a magnetic biocatalyst with excellent magnetic response and re-dispersibility.

Figure 6: (a) Magnetic hysteresis loops of ZnFe2O4, ZnFe2O4@PDA, and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML; (b) magnetic separation and re-dispersion process of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

3.2 Optimization of Lipase Activity and Loading of Immobilized RML

The classical Coomassie blue binding method was used to study the loading capacity on ZnFe2O4@PDA onto the lipase [30]. The conditions of the immobilized RML were optimized by investigating the influence of factors such as the amount of enzyme solution, pH, time, and temperature.

3.2.1 Effect of Lipase Liquid Dosage

The effects of the lipase solution dosage (0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, and 1.25 mL) on the amount and activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML were studied. As shown in Fig. 7a, the amount of immobilization increased with the increasing dosage of enzyme solution, which showed that the carrier loading was far from the maximum within the dosage range of enzyme solution. However, with an increase in the amount of the lipase solution, the activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML first increased and then decreased. The activity of the immobilized RML reached its peak when the enzyme solution dosage was 1 mL, with a lipase activity of 209.80 ± 7.90 U·g−1 and enzyme loading of 15.72 ± 0.97 mg·g−1. This indicates that a higher enzyme concentration effectively cross-linked RML with the carrier material at the beginning of the immobilization process. However, excessive accumulation of lipase on the carrier surface increased the enzyme’s steric hindrance and diffusion resistance, making it difficult for the enzyme to release, and the enzyme’s activity decreased accordingly. Therefore, the appropriate amount of enzyme solution was 1 mL.

Figure 7: Effect (a) lipase liquid dosage, (b) pH, (c) time, and (d) temperature on immobilization capacity and lipase activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

Based on the immobilization ability and activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML, the appropriate pH value of the buffer was determined. The influence of pH values between 6.5 and 9.0 was investigated (Fig. 7b), and it was found that the lipase activity reached its maximum at pH = 7.0. The lipase activity was 202.80 ± 10.12 U·g−1. However, the maximum immobilization capacity of 20.06 ± 1.17 mg·g−1 was observed at pH 8.5, because the reactive groups of PDA have the highest activity at pH 8.5. However, too high a pH led to the inactivation of the lipase. At the same time, too high an amount of enzyme led to excessive covalent bonding between the lipase and the carrier, thereby reducing the enzymatic activity. Therefore, the appropriate pH was 7.0.

The effects of immobilization time from 1 to 6 h on lipase’s immobilization ability and activity were investigated. As shown in Fig. 7c, the immobilized load curve showed a continuing rising trend, which shows that the protein content of the sample increased with time. In contrast, the lipase activity curve first increased and then decreased. The results demonstrate that ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML reached its maximum activity in 5 h, with a lipase activity of 224.75 ± 16.12 U·g−1 and enzyme loading of 20.25 ± 0.40 mg·g−1. Combined with the literature analysis [33], it was determined that at the beginning, the concentration of the total enzyme in the liquid was high, and the lipase naturally adsorbed onto the surface of the carrier, so that the mass transfer effect was good. The lipase activity of the sample increased with time. Over the immobilization time of 5 h, excessive lipase molecules gathered and accumulated on the carrier surface. The interactions between the enzyme molecules became larger and larger, and the steric hindrance increased. After 5 h, although the amount of immobilized enzyme was still growing, the lipase activity of the sample began to decrease. The reason for this is that the steric hindrance increased with enzyme immobilization. The substrate could not effectively combine with the enzyme’s active site, and the diffusion resistance increased, leading to decreased lipase activity. Therefore, 5 h was used as a fixed time for further testing.

3.2.4 Effect of Immobilization Temperature

The activity change of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML between 30°C to 50°C was investigated. As shown in Fig. 7d, the immobilized load curve showed a continuing rising trend, which showed that the protein content of the sample increased with temperature. The lipase activity curve first increased and then decreased. The results show that ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML had the highest lipase activity at 40°C, with a lipase activity of 215.32 ± 11.08 U·g−1 and enzyme loading of 19.22 ± 0.86 mg·g−1. The immobilization load was slower when the temperature was lower, and the lipase content on the carrier was lower after the reaction. Fewer enzyme active sites on the carrier contacted the substrate, resulting in lower enzymatic activity in the sample. The free enzyme was denatured and inactivated if the temperature was high. Too high a loading amount led to a significant interaction between lipases on the carrier, which increased steric hindrance and diffusion resistance. Therefore, the appropriate temperature was 40°C.

3.3 Enzymatic Properties of Free RML and ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML

Acid–base stability has always been one of the critical reasons for the broad application of restriction enzymes, and immobilization technology can improve the acid–base stability of enzymes, thereby broadening the application field of enzymes. Therefore, acid–base stability is one of the essential enzymatic properties of immobilized enzymes. As shown in Fig. 8a, the immobilized and free lipases showed an optimum pH = 7. In addition, at different pH values, the activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was higher than that of free lipase. In particular, the lipase activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was 86.14% at pH 6, while that of RML was only 19.18%. The immobilized lipase activity reached over 70% at pH 6~9, which shows that the catalytic activity of immobilized RML was higher than that of free RML [34].

Figure 8: The activity of free and immobilized RML. pH (a), temperature (b), storage stability (c), and reusability (d)

Without substrate, free RML and immobilized RML were incubated at different temperatures (40°C~60°C) to study their thermal stability. As shown in Fig. 8b, the activities of both lipases decreased with increasing incubation time. However, at the same temperature, the activity of immobilized RML decreased to a lesser degree than that of free RML. At 45°C~55°C, free RML lost about 60% of its activity, and the activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML remained above 50%. At 60°C, ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML retained 35.94% activity, and free RML only retained 15.50% activity, which proves that immobilization improved the thermal stability of RML. These results can be attributed to the immobilization technology significantly improving the enzyme’s structural stability. Therefore, immobilization of RML on ZnFe2O4@PDA prevented the typical thermal denaturation from extensive conformational changes [35]. ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML maintained the lipase activity at high temperatures, thus expanding the application scope of the enzyme.

Lipase activity tends to decrease with storage time, and one of the advantages of immobilized enzymes is their good storage stability. This advantage is essential for evaluating and selecting enzymes that can be applied to industrialization. Fig. 8c shows the changes in activities of free and immobilized RML stored for 12 days. During storage, the activity of the enzymes decreased, while that of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML decreased slowly. The activity of free RML was only 38% after 12 days, while that of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML remained at 63%. Therefore, ZnFe2O4@PDA played an essential role in improving the storage stability of RML.

3.3.4 Reusability of Immobilized RML

Fig. 8d shows the results of the immobilized enzyme after eight consecutive cycles. With the increase of cycle number, the lipase activity of immobilized lipase decreased gradually, which may have been due to the inactivation of the lipase and the partial loss caused by repeated use [36]. Taking the enzymatic activity of the first cycle as 100%, the lipase activity of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was still 48% after eight repeated uses. Therefore, ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML had satisfactory activity and operation stability, which could be due to the following: Firstly, the covalent bond between enzyme and carrier inhibited the leakage of lipase [37]. Secondly, the strong saturation magnetism of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML enabled it to be entirely recovered with minor weight loss.

3.4 Optimization of Transesterification Synthesis Conditions

This study aimed to maximize OPO yield. Meanwhile, the percentage of PA-Sn2 also needed to be considered because its high value means a lower content of PA at the sn-1,3 position [38]. This study investigated the lipase catalysts from different OA/PPP molar ratios, time, temperature, and lipase amount for sn-1,3 specificity.

3.4.1 Effect of the Molar Ratio

Transesterification’s reversibility and side reactions may lead to incomplete substrate conversion [39]. Therefore, the effect of the molar ratio of oleic acid to glyceryl tripalmitate (OA/PPP) from 2:1 to 10:1 on the yield of OPO and the percentage of PA-Sn2 was investigated. As shown in Fig. 9a, with the increase of OA/PPP from 2:1 to 8:1, the OPO yield increased from 30.89% to 41.98%. There were no significant differences in the total yield with further increases in substrate ratio. This result may have been because the enzyme’s active site could not accommodate excessive OA. Excessive OA increases the viscosity of the reaction system, and the mass transfer resistance also increases correspondingly, which is not conducive to the transesterification reaction [40]. The increased percentage of PA-Sn2 was due to the substitution of OA for the sn-1,3 position of the PA. Considering the OPO yield, acyl migration, and production cost, a molar ratio of 8:1 was suitable.

Figure 9: The effect of optimized conditions on OPO yield and the percentage of PA-Sn2. (a) molar ratio, (b) enzyme load, (c) temperature, and (d) time

3.4.2 Effect of the ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML Dosage

The influence of dosages of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML from 4% to 12% (w/w) of the total mass of the substrate on the OPO yield was studied. As shown in Fig. 9b, as the lipase dosage increased from 4% to 8%, the OPO yield increased from 28.82% to 41.77%. When lipase was less than 8%, the OPO yield rapidly increased because there were fewer active lipase sites to catalyze the reaction. However, the OPO yield decreased with further increases in the amount of RML. The results can be explained by the contact of the enzyme with the substrate causing a hydrolysis side reaction, resulting in the transfer of acyl groups [41]. As with the OPO yield curve trend, the percentage of PA-Sn2 increased first and then decreased, which may have been due to the more accessible contact between immobilized RML and the substrate with the increase of lipase loading, thus promoting hydrolysis and acyl migration. Considering the high yield of OPO and the cost of the enzyme, 8 wt% lipase loading was appropriate.

3.4.3 Effects of Reaction Temperature

Temperature has a significant influence on the reaction system. Increasing the temperature is conducive to mass transfer, thus increasing the reaction rate. However, excessive temperature inactivates lipase [42,43]. We studied the appropriate reaction temperature to obtain a high OPO yield and low acyl migration. As shown in Fig. 9c, the yield curve of OPO first increased and then decreased, reaching a maximum value of 42.63% at 40°C. Above 40°C, the yield of OPO fell obviously, indicating that lipase was inactivated. It can also be seen from Fig. 9c that the percentage trend of PA-Sn2 was consistent with that of OPO and reached its maximum value (54.63%) at 40°C. A possible explanation for this is that the immobilized lipase activity decreased when the reaction temperature increased, and acyl migration increased. Therefore, 40°C was chosen for the following study.

3.4.4 Effects of Reaction Time

Appropriate reaction time is beneficial to reducing the production cost, so the effect of reaction time from 3 to 18 h on the yield of OPO was studied. Fig. 9d shows that the OPO yield increased with increasing reaction time and remained relatively stable. The highest OPO yield was 42.78% at 12 h, decreasing after 12 h. The percentage of PA-Sn2 also reached the maximum at 12 h, which may have been due to the migration of acyl groups in the lipase-catalyzed reaction. Therefore, the reaction used subsequently time was 12 h.

The commercial immobilized lipases of Novozym TL IM and Novozym RM IM have been used to synthesize OPO, and the yield is mostly 38%~42% [41,44], but they are expensive. It can be found that the yield of OPO prepared by self-made immobilized lipase is slightly higher than that of commercial immobilized lipase.

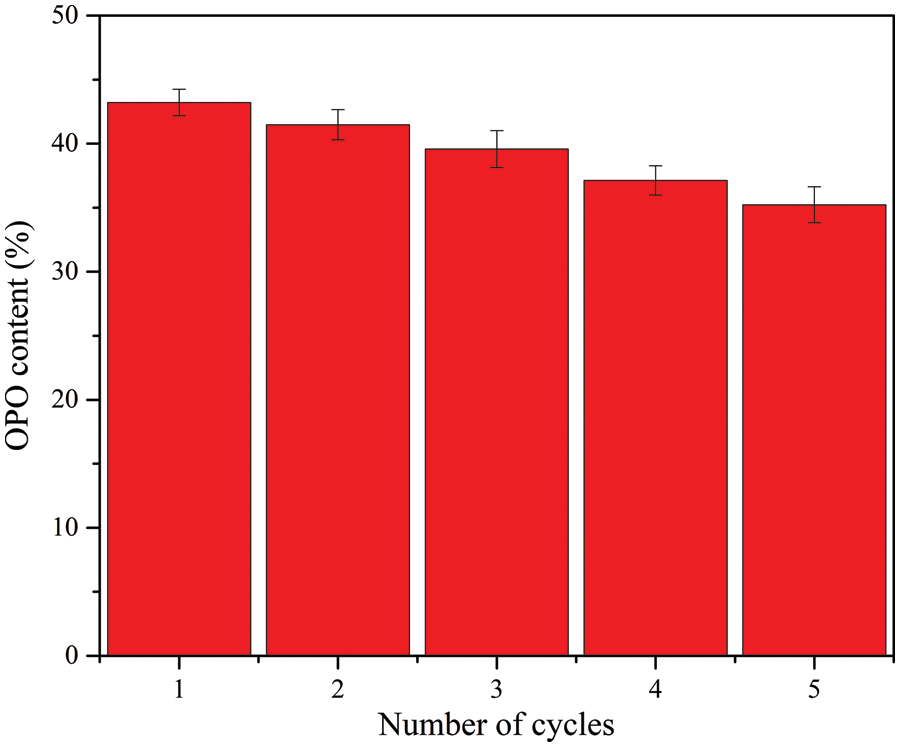

3.5 Reusability of the Immobilized Lipase and Leaching

The repeated use of immobilized lipases is critical to their industrial applicability. Fig. 10 shows the results of five consecutive transesterification reactions of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML. The OPO yield gradually decreased with the increasing cycle number, which may be attributable to the loss of a proportion of the enzyme content over repeated use and the denaturation of the immobilized RML. After five repeated uses of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML, the OPO yield reached 35.23%. These findings verify its potential in biocatalytic industries [45]. In addition, a leaching experiment of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was carried out. In a typical experiment, ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was separated by a magnet after 6 h of OPO synthesis. The transesterification reaction was continued for another 6 h with the remaining filtrate. The results showed that no additional OPO was detected in the reaction mixture. In addition, no enzyme leaching was detected in the solution, which indicates that only a covalent bond bound the RML onto ZnFe2O4@PDA.

Figure 10: Reusability of ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML for the synthesis of OPO

In summary, magnetic ZnFe2O4@PDA was prepared and successfully used as the immobilized carrier of RML. The following conditions were optimized to immobilize RML: 40°C, pH 7.0, 1 mL of enzyme solution, and 5 h of fixation time. Under these conditions, ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML was efficiently obtained. ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML showed better activity and adaptability to higher temperatures or pH than free RML and could be reused by rapid recovery with external magnets. The following conditions were optimized to synthesize OPO: 40°C, n(OA):n(PPP) = 8:1, 8 wt% lipase loading, and 12 h. Under optimized conditions, a high-efficiency OPO yield (42.78%) was obtained, in which the percentage of PA-Sn2 was 54.63%. The results confirm that ZnFe2O4@PDA@RML can be considered a stable and efficient biocatalyst for OPO synthesis.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Science and Technology Program in Guangzhou City of China (Grant No. 201904010087), the National College Students Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program of China (Grant No. 202111347022), the Science and Technology Innovation Fund for Graduate Students (Grant No. KJCX2021005), Innovative Team Projects of Universities in Guangdong Province of China (Grant No. 2016KCXTD003), and 2021 Guangdong University Research Platform and Scientific Research Project (Grant No. 2021ZDZX2056).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Martysiak-Żurowska, D., Malinowska-Pańczyk, E., Orzołek, M., Kiełbratowska, B., Sinkiewicz-Darolc, E. et al. (2022). Effect of convection and microwave heating on the retention of bioactive components in human milk. Food Chemistry, 374(10), 131772. DOI 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang, X., Jiang, C., Xu, W., Miu, Z., Jin, Q. et al. (2020). Enzymatic synthesis of structured triacylglycerols rich in 1,3-dioleoyl-2-palmitoylglycerol and 1-oleoyl-2-palmitoyl-3-linoleoylglycerol in a solvent free system. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 118, 108798. DOI 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hasibuan, H. A., Sitanggang, A. B., Andarwulan, N., Hariyadi, P. (2021). Enzymatic synthesis of human milk fat substitute–A review on technological approaches. Food Technology and Biotechnology, 59(4), 475–495. DOI 10.17113/ftb.59.04.21.7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tiago, S., Francisco, V., Carla, T., Suzana, F. D. (2014). Production of human milk fat substitutes catalyzed by a heterologous Rhizopus oryzae lipase and commercial lipases. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 91(3), 411–419. DOI 10.1007/s11746-013-2379-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pereira, A. S., Souza, A. H., Fraga, J. L., Villeneuve, P., Torres, A. G. et al. (2022). Lipases as effective green biocatalysts for phytosterol esters’ production: A review. Catalysts, 12(1), 88. DOI 10.3390/catal12010088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Stepankova, V., Bidmanova, S., Koudelakova, T., Prokop, Z., Chaloupkova, R. et al. (2013). Strategies for stabilization of enzymes in organic solvents. ACS Catalysis, 3(12), 2823–2836. DOI 10.1021/cs400684x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dubey, N. C., Tripathi, B. P. (2021). Nature inspired multienzyme immobilization: Strategies and concepts. ACS Applied Bio Materials, 4(2), 1077–1114. DOI 10.1021/acsabm.0c01293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Landarani-Isfahani, A., Taheri-Kafrani, A., Amini, M., Mirkhani, V., Moghadam, M. et al. (2015). Xylanase immobilized on novel multifunctional hyperbranched polyglycerol-grafted magnetic nanoparticles: An efficient and robust biocatalyst. Langmuir, 31(33), 9219–9227. DOI 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rodrigues, R. C., Ortiz, C., Berenguer-Murcia, Á., Torres, R., Fernández-Lafuente, R. (2013). Modifying enzyme activity and selectivity by immobilization. Chemical Society Reviews, 42(15), 6290–6307. DOI 10.1039/c2cs35231a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Agrawal, S., Kango, N. (2019). Development and catalytic characterization of L-asparaginase nano-bioconjugates. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 135(1), 1142–1150. DOI 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Monterrey, D. T., Ayuso-Fernández, I., Oroz-Guinea, I., García-Junceda, E. (2022). Design and biocatalytic applications of genetically fused multifunctional enzymes. Biotechnology Advances, 60, 108016. DOI 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.108016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Smith, S., Goodge, K., Delaney, M., Struzyk, A., Tansey, N. et al. (2020). A comprehensive review of the covalent immobilization of biomolecules onto electrospun nanofibers. Nanomaterials, 10(11), 2142. DOI 10.3390/nano10112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Rezaei, A., Akhavan, O., Hashemi, E., Shamsara, M. (2016). Ugi four-component assembly process: An efficient approach for one-pot multifunctionalization of nanographene oxide in water and its application in lipase immobilization. Chemistry of Materials, 28(9), 3004–3016. DOI 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b00099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Escudero, A., Ríos, A. P. L., Godínez, C., Tomás, F., Hernández-Fernández, F. J. (2020). Immobilization in ionogel: A new way to improve the activity and stability of Candida antarctica lipase B. Molecules, 25(14), 3233. DOI 10.3390/molecules25143233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Song, J. Y., Su, P., Ma, R. A., Yang, Y., Yang, Y. (2017). Based on DNA strand displacement and functionalized magnetic nanoparticles: A promising strategy for enzyme immobilization. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 56(17), 5127–5137. DOI 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b00595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhao, J. F., Lin, J. P., Yang, L. R., Wu, M. B. (2019). Enhanced performance of Rhizopus oryzae lipase by reasonable immobilization on magnetic nanoparticles and its application in synthesis 1,3-diacyglycerol. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 188(3), 677–689. DOI 10.1007/s12010-018-02947-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Patel, S. K. S., Choi, S. H., Yun, C. K., Lee, J. K. (2017). Eco-friendly composite of Fe3O4-reduced graphene oxide particles for efficient enzyme immobilization. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 9(3), 2213–2222. DOI 10.1021/acsami.6b05165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang, Y. L., Zhu, G. X., Wang, G. C., Li, Y. L., Tang, R. K. (2016). Robust glucose oxidase with a Fe3O4@C-silica nanohybrid structure. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 4(27), 4726–4731. DOI 10.1039/c6tb01355d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang, C. H., Han, H. B., Jiang, W., Ding, X. B., Li, Q. S. et al. (2017). Immobilization of thermostable lipase QLM on core-shell structured polydopamine-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Catalysts, 7(2), 49. DOI 10.3390/catal7020049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lee, H., Rho, J., Messersmith, P. B. (2009). Facile conjugation of biomolecules onto surfaces via mussel adhesive protein inspired coatings. Advanced Materials, 21(4), 431–434. DOI 10.1002/adma.200801222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xie, W. L., Zang, X. Z. (2017). Covalent immobilization of lipase onto aminopropyl-functionalized hydroxyapatite-encapsulated-γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles: A magnetic biocatalyst for interesterification of soybean oil. Food Chemistry, 227(5), 397–403. DOI 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gu, Y. H., Yuan, L., Li, M. M., Wang, X. Y., Rao, D. Y. et al. (2022). Co-immobilized bienzyme of horseradish peroxidase and glucose oxidase on dopamine-modified cellulose-chitosan composite beads as a high-efficiency biocatalyst for degradation of acridine. RSC Advances, 12(35), 23006–23016. DOI 10.1039/d2ra04091c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Marakana, P. G., Dey, A., Saini, B. (2021). Isolation of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: Synthesis, characterization, modification, and potential applications. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 9(6), 106606. DOI 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Andrade, M. F. C., Parussulo, A. L. A., Netto, C. G. C. M., Andrade, L. H., Toma, H. E. (2016). Lipase immobilized on polydopamine-coated magnetite nanoparticles for biodiesel production from soybean oil. Biofuel Research Journal, 3(2), 403–409. DOI 10.18331/brj2016.3.2.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bradford, M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry, 72(1–2), 248–254. DOI 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Asmat, S., Husain, Q. (2018). Exquisite stability and catalytic performance of immobilized lipase on novel fabricated nanocellulose fused polypyrrole/graphene oxide nanocomposite: Characterization and application. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 117(15), 331–341. DOI 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu, S., Dong, X., Wei, F., Xiang, W., Lv, X. et al. (2015). Ultrasonic pretreatment in lipase-catalyzed synthesis of structured lipids with high 1,3-dioleoyl-2-palmitoylglycerol content. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 23, 100–108. DOI 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.10.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang, X. S., Zou, W. Z., Sun, X. M., Zhang, Y., Wei, L. Y. et al. (2015). Chemoenzymatic synthesis of 1,3-dioleoyl-2-palmitoylglycerol. Biotechnology Letters, 37(3), 691–696. DOI 10.1007/s10529-014-1714-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ingle, R. V., Shaikh, S. F., Bhujbal, P. K., Pathan, H. M., Tabhane, V. A. (2020). Polyaniline doped with protonic acids: Optical and morphological studies. ES Materials & Manufacturing, 8, 54–59. DOI 10.30919/esmm5f732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Qiu, C., Han, H. H., Sun, J., Zhang, H. T., Wei, W. et al. (2019). Regulating intracellular fate of siRNA by endoplasmic reticulum membrane-decorated hybrid nanoplexes. Nature Communications, 10(1), 2702. DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-10562-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mosayebi, M., Salehi, Z., Doosthosseini, H., Tishbi, P., Kawase, Y. (2020). Amine, thiol, and octyl functionalization of GO-Fe3O4 nanocomposites to enhance immobilization of lipase for transesterification. Renewable Energy, 154(80), 569–580. DOI 10.1016/j.renene.2020.03.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhao, J. X., Ma, M. M., Yan, X. H., Zhang, G. H., Xia, J. H. et al. (2022). Green synthesis of polydopamine functionalized magnetic mesoporous biochar for lipase immobilization and its application in interesterification for novel structured lipids production. Food Chemistry, 379, 132148. DOI 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tan, T. W., Lu, J. K., Nie, K. L., Deng, L., Wang, F. (2010). Biodiesel production with immobilized lipase: A review. Biotechnology Advances, 28(5), 628–634. DOI 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Madan, L. V., Nalam, M. R., Takuya, T., Colin, J. B., Munish, P. (2019). Suitability of recombinant lipase immobilised on functionalised magnetic nanoparticles for fish oil hydrolysis. Catalysts, 9(5), 420. DOI 10.3390/catal9050420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hanefeld, U., Gardossi, L., Magner, E. (2009). Understanding enzyme immobilisation. Chemical Society Reviews, 38(2), 453–468. DOI 10.1039/b711564b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Matuoog, N., Li, K., Yan, Y. (2018). Thermomyces lanuginosus lipase immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles and its application in the hydrolysis of fish oil. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 42(5), e12549. DOI 10.1111/jfbc.12549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zheng, M. M., Huang, Q., Huang, F. H., Guo, P. M., Xiang, X. et al. (2014). Production of novel “functional oil” rich in diglycerides and phytosterol esters with “one-pot enzymatic transesterification. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 62(22), 5142–5148. DOI 10.1021/jf500744n. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ferreira-Dias, S., Osório, N. M., Tecelão, C. (2018). Lipase-catalyzed synthesis of structured lipids at laboratory scale: Methods and protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1835(8), 315–336. DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-8672-9_17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Pulido, I. Y., Prieto, E., Jimenez-Junca, C. A. (2021). Ethanol as additive enhance the performance of immobilized lipase lipA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on polypropylene support. Biotechnology Reports, 31, e00659. DOI 10.1016/j.btre.2021.e00659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang, X., Chen, Y., Zheng, L., Jin, Q., Wang, X. (2017). Synthesis of 1,3-distearoyl-2-oleoylglycerol by enzymatic acidolysis in a solvent-free system. Food Chemistry, 228(928), 420–426. DOI 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zheng, M., Wang, S., Xiang, X., Shi, J., Huang, J. et al. (2017). Facile preparation of magnetic carbon nanotubes-immobilized lipase for highly efficient synthesis of 1,3-dioleoyl-2-palmitoylglycerol-rich human milk fat substitutes. Food Chemistry, 228(1), 476–483. DOI 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Meneses, A. C., Lerin, L. A., Araújo, P. H. H., Sayer, C., Oliveira, D. (2019). Benzyl propionate synthesis by fed-batch esterification using commercial immobilized and lyophilized Cal B lipase. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 42(10), 1625–1634. DOI 10.1007/s00449-019-02159-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kim, B. H., Akoh, C. C. (2005). Modeling of lipase-catalyzed acidolysis of sesame oil and caprylic acid by response surface methodology: Optimization of reaction conditions by considering both acyl incorporation and migration. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 53(20), 8033–8037. DOI 10.1021/jf0509761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Cai, Z. X., Wei, Y., Wu, M., Guo, Y. L., Xie, Y. P. et al. (2019). Lipase immobilized on layer-by-layer polysaccharide-coated Fe3O4@SiO2 microspheres as a reusable biocatalyst for the production of structured lipids. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering, 7(7), 6685–6695. DOI 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Flávia, A. P. L., Jaquelinne, J. B., Maria, C. C. C., Larissa, M. T., Jaine, H. H. L. et al. (2016). Preparation of a biocatalyst via physical adsorption of lipase from Thermomyces lanuginosus on hydrophobic support to catalyze biolubricant synthesis by esterification reaction in a solvent-free system. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 84, 56–67. DOI 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools