Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Conductive Carbon Black on Thermal and Electrical Properties of Barium Titanate/Polyvinylidene Fluoride Composites for Road Application

School of Highway, Chang’an University, Xi’an, 710064, China

* Corresponding Author: Yejing Meng. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2023, 11(5), 2469-2489. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2023.025497

Received 17 July 2022; Accepted 19 August 2022; Issue published 13 February 2023

Abstract

In the field of roads, due to the effect of vehicle loads, piezoelectric materials under the road surface can convert mechanical vibration into electrical energy, which can be further used in road facilities such as traffic signals and street lamps. The barium titanate/polyvinylidene fluoride (BaTiO3/PVDF) composite, the most common hybrid ceramic-polymer system, was widely used in various fields because the composite combines the good dielectric property of ceramic materials with the good flexibility of PVDF material. Previous studies have found that conductive particles can further improve the dielectric and piezoelectric properties of other composites. However, few studies have investigated the effect of conductive carbon black on the dielectric and piezoelectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF composites. In this study, BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites were prepared with various conductive carbon black contents based on the optimum ratio of BaTiO3 to PVDF. The effects of conductive carbon black content on the morphologies, thermal performance, conductivities, dielectric properties, and piezoelectric properties of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites were then investigated. The addition of conductive carbon black greatly enhances the conductivities, dielectric properties, and piezoelectric properties of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites, especially when the carbon black content is 0.8% by weight of PVDF. Additionally, the conductive carbon black does not have an obvious effect on the morphologies and thermal stabilities of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites.Keywords

In a variety of fields, including electrical engineering, communications engineering, and civil engineering, piezoelectric materials that transform mechanical energy into electrical energy have attracted increasing attention in recent years [1–3]. Much effort has been put into developing the raw materials and process technologies of piezoelectric materials to convert different sources of energy into electrical energy to meet the varying requirements of different fields [4–7].

The piezoelectric phenomenon was first discovered by the Curie brothers in 1880, but piezoelectricity was first primarily applied by Lanngevin in 1917 [8]. Piezoelectric materials are numerous, however, there are primarily three types: natural piezoelectric materials, piezoelectric ceramics, and polymer-film piezoelectric. Quartz was considered the most common natural piezoelectric material and the only available piezoelectric material until 1940 [8]. The application used a quartz single crystal piece sandwiched between two steel plates to transmit an ultrasonic pulse. The secondary category is piezoelectric ceramics. Barium titanate (BaTiO3) was the most widely utilized during that period since piezoelectric BaTiO3 ceramics exhibited a high coupling coefficient and nonaqueous solubility [9]. But the drawback of original BaTiO3 ceramics is that their low Curie temperature causes an aging effect [10]. To overcome this problem, various solutions were intensively studied, such as using metal ions (i.e., Pb and Ca) to replace barium ions. In particular, lead zirconate titanate (Pb (Zr, Ti)O3: PZT), a perovskite-type crystalline structure, was first discovered by Shirane and coworkers in 1952 [11], and its piezoelectricity was found by Jaffe et al. in 1954 [12]. Since then, the BaTiO3 ceramic had been gradually replaced by PZT in a variety of fields due to its superior piezoelectric properties and excellent shaping flexibility. PZT, however, contains more than 60% lead (Pb) regardless of the processing technologies. Due to increasing environmental awareness and governmental restrictions, lead-in PZT ceramic materials are being increasingly limited around the world. The third type is polymer-film piezoelectric, such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF). PVDF has been rapidly applied in various fields, such as underwater acoustic detection, pressure sensing, ignition, and detonation, because it has the advantages of good shaping flexibility, low density, and a high piezoelectric voltage constant [13,14].

What is more, piezoelectric materials are extensively used not only in electronics and communications but also in roadways [15,16]. Roadways are continuously subjected to repetitive vehicle loading for long periods [17–19]. Vehicles ride over pavement, which leads to stress and strain raisers under the wheel, as shown in Fig. 1. Under the pavement, piezoelectric materials can convert the mechanical vibration to electric energy that can be further used for road facilities (Fig. 1), such as traffic signals and streetlights. Therefore, piezoelectric materials applied to roadways should possess a certain mechanical strength and deformability [20]. Piezoelectric ceramics have excellent dielectric properties but are prone to brittleness and require high-temperature processing [21]. On the other hand, polymer-film piezoelectric materials have excellent mechanical performance and good flexibility at low temperatures but poor piezoelectric properties [22]. A compound ceramic-polymeric composite is an available solution to address and remedy these weaknesses [23]. In recent years, ceramic and polymer composites have attracted increasing attention due to convenient fabrication, low cost, and excellent performance, such as low dielectric loss, low leakage current, and low conductivity.

Figure 1: A schematic diagram of a roadway with piezoelectric materials

The BaTiO3/PVDF composite is a common hybrid ceramic-polymer system. The size and surface of BaTiO3 ceramic powder play an important role in the dielectric properties of the composite during the preparation process [24]. Specifically, the dielectric and piezoelectric properties of the composite can be effectively improved by increasing the ceramic content and decreasing the grain size [25]. The piezoelectric and dielectric properties of the composite, however, will deteriorate when the content and grain size exceed a certain value [26]. Therefore, the electrical properties of the composites cannot be simply improved by increasing the ceramic content and reducing the ceramic size. Recent studies have found that the conductivity and piezoelectric properties of ceramic and polymer composites can be effectively enhanced by the addition of conductive particles, such as carbon black [26], carbon nanotubes [27], and graphene [28]. Additionally, the nanoparticles were added to enhance the piezoelectric of ceramic and polymer composites, such as ZnO nanoparticles [29] and iron nanoparticles [30]. Previous studies found that the addition of small contents of carbon black can enhance the conductivity of composites [31]. Our previous study also demonstrated that carbon black could improve the mechanical and piezoelectric performances of PZT/PVDF composites [32]. However, few studies have investigated the effect of carbon black on the piezoelectric performance of BaTiO3/PVDF composites.

In this study, BaTiO3/PVDF composites with different volume ratios of BaTiO3 to PVDF were first prepared by the hot-press method. The optimum ratio was then determined by balancing the morphologies, dielectric properties, and piezoelectric performance. Based on the optimum ratio of BaTiO3/PVDF composites, BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites were prepared with different conductive carbon black contents using the hot-press method. The morphologies and thermal performance of the composites were then examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and a thermal analyzer (TA), respectively. The effects of carbon black content on the conductivities, dielectric properties, and piezoelectric properties of the composites were evaluated using electrical conductivity, the relative dielectric constant, and the piezoelectric strain constant, respectively. Finally, a summary and conclusions were created. It is believed that this study will deepen our understanding of how carbon black affects the electrical properties of composites, thereby contributing to the development of piezoelectric materials in roadways.

BaTiO3 is a white powder provided by Shandong Guoci Functional Materials Co., Ltd., China. The melting point and relative density are 1625°C and 6.017 g/cm3, respectively. The distribution of ceramic particles with various particle sizes is relatively uneven, as shown in Fig. 2. And the maximum particle size is no more than 200 μm, the minimum particle size is not less than 0.01 μm, and the particle size is mostly concentrated in 0.1∼100 μm. As is shown in Fig. 3, the contents of carbon, oxygen, barium, and titanium are 31.58%, 30.61%, 28.11%, and 8.85%, respectively. There are also a small amount of Al, Si, and Co impurities. Therefore, BaTiO3 ceramic is a completely eco-friendly green ceramic material that essentially lacks any toxic heavy metal components.

Figure 2: Particle size distribution of BaTiO3

Figure 3: Mass percentage of elements in BaTiO3

The SEM morphology of BaTiO3 is shown in Fig. 4, due to the effect of surface energy, there is a certain agglomeration phenomenon and the particles have an irregular spherical shape with a small particle size difference in the unburned ceramic particles. As shown in Fig. 5, the FTIR spectra of BaTiO3 showed enhanced absorption at 423 and 489 cm−1, which mainly corresponded to the bending and stretching of the Ti-O bond, respectively. Additionally, the FTIR spectra also showed the absorption peaks at 1423 and 3513 cm−1, which mainly corresponded to the bending and stretching of the O-H bond, respectively. It means that there may be water or alcohol impurities in the BaTiO3 powders. These impurities will, however, evaporate in the high-temperature environment of the test without affecting the results.

Figure 4: The SEM morphology of BaTiO3

Figure 5: The FT-IR spectrum of BaTiO3

The XRD spectrum of BaTiO3 is shown in Fig. 6. At the (110) crystal surface of BaTiO3 crystal, the main diffraction peak of BaTiO3 was high and the intensity was large, which indicated that BaTiO3 crystal grows preferentially along the (110) crystal surface. The XRD diffraction peak of BaTiO3 powder is consistent with the diffraction peak of the tetragonal BaTiO3 standard card (PDF#05–0626). After amplifying at roughly 2θ = 45° and observing its diffraction peak, it was discovered that the diffraction peak on the crystal plane were double peaks, which were (002) and (200), respectively. At the same time, it was also found that there were strong diffraction peaks at the crystal planes (100), (111), and (200) of BaTiO3 crystal, which indicated that BaTiO3 has good crystallinity and is a pure tetragonal perovskite structure, and also confirms that BaTiO3 ceramics have certain piezoelectric properties [33–35]. Barium titanate crystals exhibit paraelectricity above the Curie temperature (approximately 120°C) and ferroelectricity below the Curie temperature [36].

Figure 6: The XRD spectrum of BaTiO3

PVDF is a powder manufactured by Shanghai 3F New Materials Co., Ltd., China. The detailed properties are shown in Table 1.

The FTIR spectrum of PVDF powder is shown in Fig. 7. The FTIR spectra of PVDF showed enhanced absorption at 522 and 846 cm−1, which corresponded to the bending of CF2 and rocking of CH2, respectively. The FTIR spectra also showed absorption peaks at 613 and 762 cm−1, which corresponded to the CF2 bending and skeletal bending. Additionally, the absorption peak at 976 cm−1 corresponded to the out-of-plane deformation. It was shown that PVDF exhibited at least four crystalline phases, known as α, β, γ, and δ [37,38]. The different absorption peaks in the FTIR spectrum of PVDF give valuable information about the crystal phase of PVDF [39]. As shown in Fig. 7, vibrational bands at 522, 613, 762, and 976 cm−1 corresponded to the α phase, while, vibrational bands at 846 cm−1 referred to the β phase. Therefore, in the PVDF powder, the α phase crystal is the main.

Figure 7: The FT-IR spectrum of PVDF powder

As seen in Fig. 8, neat PVDF exhibited major crystalline peaks at 2θ = 17.9°, 20.0°, 26.5°, and 38.4°, which were attributed to the α phase. This result was generally consistent with the findings which obtained from the analysis of the FTIR. These peaks represented (020), (110), (021), and (002) crystal planes, respectively [40,41]. The piezoelectric properties of α phase crystal of PVDF are poor, so the polymer only acts as the effect of mechanical toughening and the elimination of interphase voids of ceramics in the composite. As a result, its contribution to the overall piezoelectric properties of the composite is less obvious.

Figure 8: The XRD spectrum of PVDF powder

Cabot’s Black Pearls® 2000 (BP 2000) was chosen as the conductive carbon black. The physical properties are listed in Table 2.

2.2 Preparation Process of Composites

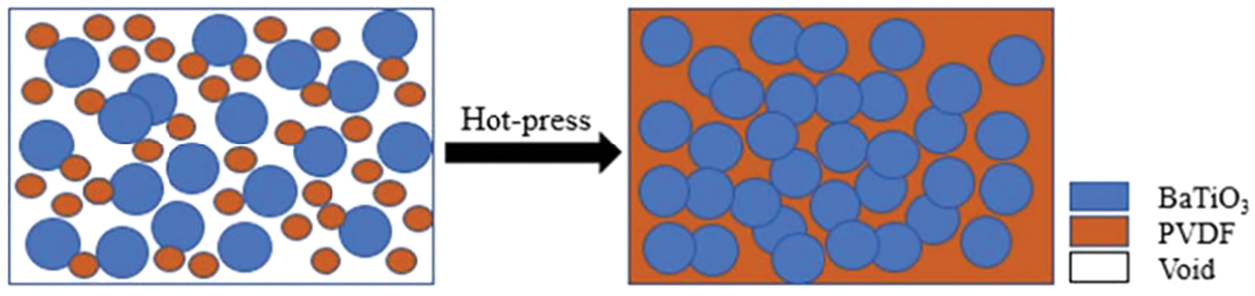

In this study, the hot-press method, a method of integrating the heating and pressing process, was used for the preparation process of composites. As shown in Fig. 9, in the hot-press process, the piezoelectric ceramic powder (BaTiO3) was fully mixed with the polymer matrix (PVDF), and the polymer was heated and melted so that the ceramic powder was wrapped by the polymer. This process made the ceramic materials still combined without sintering ceramic growth, and had certain mechanical strength. Therefore, composite materials can reduce the brittleness of ceramics and improve the overall mechanical toughness.

Figure 9: The schematic diagram of the preparation process

The steps of the preparation process are shown in Fig. 10, the specific steps are as follows: (1) BaTiO3 powder and PVDF polymer were placed in a muffle furnace at 950°C for 3 h and in an oven at 60°C for 3 h, respectively. (2) After drying and cooled to room temperature, BaTiO3 and PVDF were poured into a beaker with ethyl alcohol, and put into an ultrasonic washer to accelerate the mixing process for 30 min. (3) After drying in an oven at 90°C, the dried mixture was put into a grinding machine to grind into powder. (4) Then, the powder was heated to 180°C in heating equipment and then pressed into a cylinder 13 mm in diameter and 1 mm in thickness at 25 MPa for 30 min using a hot-press forming machine. (5) TYD-110Y conductive silver fluid, provided by UV Tech. Material, Ltd. (Guangzhou, China) was evenly coated on the top and bottom of the cylinder. (6) The dried and coated cylinder samples wer put into an oil bath at 120°C and then polarized at 3 kV/mm for 30 min using a polarization device. (7) The polarized BaTiO3/PVDF samples (Fig. 11) were placed in a dried container to discharge for 24 h.

Figure 10: The flowchart of composites preparation

Figure 11: The polarized BaTiO3/PVDF samples with five volume ratios of BaTiO3: (1) 50%, (2) 60%, (3) 70%, (4) 80%, and (5) 85%

2.2.3 BaTiO3/PVDF/Conductive Carbon Black Composites

The preparation process of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites is identical to that of the BaTiO3/PVDF composite (Fig. 12), except for Steps 2 and 3 in Section 2.2.2. Steps 2 and 3 in this section are described as follows: (2) The PVDF polymer and conductive carbon black were poured into a beaker with ethyl alcohol. The beaker was then put into an ultrasonic washer to accelerate the mixing process for 30 min. (3) The mixed liquor (PVDF polymer and conductive carbon black) and BaTiO3 were poured into a ball grinder and milled for 40 min.

Figure 12: BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites with five conductive carbon black contents: (a) 0.4%, (b) 0.6%, (c) 0.8%, (d) 1.0%, and (e) 1.2%

2.3.1 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

The structural composition of the raw material was determined by TENSOR II Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer.

The crystal structure of BaTiO3 particles, PVFD, and BaTiO3/PVDF samples with five volume ratios of BaTiO3 was analyzed by D8 Advance X-ray Diffractometer (XRD).

The morphologies of BaTiO3/PVDF and BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites were examined using a Hitachi S−570 Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).

The thermal stability of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites was investigated using a TGA/DSC3+ thermogravimetric analyzer manufactured by Mettler-Toledo Inc., Columbus, USA Samples were scanned from 30°C to 800°C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min.

Electrical conductivity (σ), the ratio of current density to electric field strength, is an important indicator used to characterize a piezoelectric material’s ability to conduct electric current. The σ values of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites were measured using an HP 4294A precision impedance analyzer.

The relative dielectric constant, the ratio of the permittivity of piezoelectric materials to the absolute dielectric constant, was used to characterize the polarization degree of the piezoelectric materials. It also represents the amount of charge that can be stored in the piezoelectric materials. In this study, the capacitance of piezoelectric materials was measured using a Hioki LCR Meter IM3536 with a high-speed measurement of 1 ms and high-precision measurement of ±0.05% representative value. The relative dielectric constant (

In this study, dielectric loss (tanδ), the ratio of effective conductance to effective susceptance in a parallel circuit, was also used to investigate the dielectric properties of the piezoelectric materials. It also indirectly represents the coupling degree between BaTiO3 and PVDF. A smaller tanδ represents a denser BaTiO3/PVDF composite and vice versa. The tanδ values can be directly measured using a Hioki LCR Meter IM3536.

2.3.7 Piezoelectric Properties

In this study, piezoelectric materials after 24 h of polarization were used to measure the piezoelectric charge constant (d33) using a ZJ-3AN Quasi-Static Piezo Meter. d33 is an important index of a piezoelectric material’s suitability for strain-dependent applications. Larger d33 values represent better field emission properties and a higher emission sensitivity of the piezoelectric materials [42]. The piezoelectric voltage constant (g33) was then calculated by the ratio of d33 and εr. g33 is another important indicator for assessing the piezoelectric material’s suitability for sensor application; the greater the g33 values, the better the receptivities of the piezoelectric materials.

3.1 Determination of the Optimum BaTiO3/PVDF Ratio

The dielectric and piezoelectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF composites can be effectively improved by increasing the ceramic content before a critical value. The high amount of BaTiO3, however, renders it difficult to resist the deformation of the composites. The low embrittlement resistance is not suitable for application on roadways under repeating traffic loading. Hence, there is an optimum BaTiO3/PVDF ratio that can balance the piezoelectric properties and deformation resistance performance of BaTiO3/PVDF composites.

In this study, BaTiO3 ratios were chosen to be 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, and 85% by the volume of the BaTiO3/PVDF composite. The optimum ratio was then investigated by analyzing the X-ray diffractometer, SEM morphologies, dielectric properties, and piezoelectric performances of the composites.

The XRD spectrum of BaTiO3 and PVDF was analyzed in 2.1.1 and 2.1.2, as shown in Fig. 13, the XRD spectrum of BaTiO3/PVDF composites appears to be a superposition of the two spectra, indicating that the formation of composites from BaTiO3 and PVDF is dominated by physical changes. Additionally, the XRD spectrum of BaTiO3/PVDF composites showed subtle differences in five volume ratios of BaTiO3. As the volume ratios of BaTiO3 increased, the crystal plane (110) and (020) which were characteristic peaks of PVDF gradually weakened, however, the crystal plane (100), (110), (111), (200), (210), (211), and (220) which were characteristic peaks of BaTiO3 gradually increased.

Figure 13: The XRD spectrum of BaTiO3/PVDF composites with five volume ratios of BaTiO3

The high and low magnified morphologies of BaTiO3/PVDF composites with different ratios of BaTiO3 to PVDF were examined using SEM. The BaTiO3 ceramic particles were evenly dispersed in the PVDF matrix (marked by red circles in Fig. 14), while PVDF materials formed a connect net structure and coated the partial surface of the BaTiO3 particles (marked by blue circles in Fig. 14). As the BaTiO3 content increased, the gaps between the BaTiO3 particles displayed a downward trend, and the BaTiO3/PVDF composites became denser, as shown in Fig. 14. Especially, as shown in Fig. 14e, when the BaTiO3 content rose to 85%, the BaTiO3 particles reunited together to form larger particles, as the PVDF content was too low to separate the BaTiO3 particles.

Figure 14: The SEM morphologies of BaTiO3/PVDF composites with five volume ratios of BaTiO3: (a) 50%, (b) 60%, (c) 70%, (d) 80%, and (e) 85%

3.1.3 Effect of BaTiO3 Content on the Dielectric Properties of BaTiO3/PVDF Composites

The relative dielectric constant (εr) and dielectric loss (tanδ) were used for evaluating the dielectric properties of the BaTiO3/PVDF composites with different BaTiO3 contents, as shown in Fig. 15. The εr values of the composites dramatically increased at first and then decreased with increasing BaTiO3 content. The εr of the composites reached the maximum value when the BaTiO3 content was 70% by volume of the composite. Compared with the BaTiO3/PVDF composite with 50% BaTiO3 ceramic, the εr value of the BaTiO3/PVDF composite increased by 78.4% when the BaTiO3 content was 70%. When the BaTiO3 content was greater than 70%, the εr value decreased with increasing BaTiO3 content because BaTiO3 particles reunited together to form larger particles. The reunited BaTiO3 particles resulted in a lower polarization efficiency of the BaTiO3/PVDF composites.

Figure 15: Effects of BaTiO3 content on the dielectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF composites

Fig. 15 also shows that the tanδ values of the BaTiO3/PVDF composites steadily increased as the BaTiO3 content increased. This is because the carriers in the dielectric material generated a flow of electric charge caused by an external electric field and then consumed electricity that was converted into heat. However, the tanδ value of the composite is still less than 0.024, which is a small value for dielectric materials with a BaTiO3 content of 85%.

3.1.4 Effect of BaTiO3 Content on the Piezoelectric Properties of BaTiO3/PVDF Composites

The piezoelectric property of the BaTiO3/PVDF composite is mainly governed by BaTiO3 particles. The effect of BaTiO3 content on the piezoelectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF composites was examined using the piezoelectric charge constant (d33) and piezoelectric voltage constant (g33), as shown in Fig. 16. The d33 values of the composites initially showed an upward trend and then decreased with increasing BaTiO3 content. The d33 value reached the maximum value (26 pC/N) when the BaTiO3 content was 70% by volume of the composite, increasing by 44.4% compared with the composite containing 50% BaTiO3 particles. When the BaTiO3 content was 85% by volume of the composite, the d33 of the composite decreased to 20 pC/N.

Figure 16: Effects of BaTiO3 content on the piezoelectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF composites

Fig. 16 also illustrates the relationship between g33 values, the ratio of piezoelectric charge constant to dielectric constant (g33 = d33/ε), of BaTiO3/PVDF composites, and BaTiO3 contents. The g33 values showed a descending trend at first and then slightly increased as BaTiO3 contents increased because of the difference in changing rates of d33 and εr.

According to a summary of the morphologies, dielectric performance, and piezoelectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF composites, it can be stated that the optimum BaTiO3 content is 70% by volume since at this level, the composite reaches a plateau in the dielectric and piezoelectric properties. The BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites were prepared based on the optimum content and then evaluated in the following sections.

3.2 Effect of Conductive Carbon Black on the Performance of BaTiO3/PVDF Composites

As shown in Fig. 17, the PVDF polymer was evenly mixed with BaTiO3 particles, while the BaTiO3 particles were bound together. There was no defect on the surface of BaTiO3 particles or at the interfaces between the PVDF polymer and BaTiO3 particles. Conductive carbon black, however, was not observed because the particle size of conductive carbon black is far less than that of PVDF polymer and BaTiO3 particles. Additionally, the addition of conductive carbon black did not affect the microstructure of the BaTiO3/PVDF composites.

Figure 17: The SEM morphologies of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites with five conductive carbon black contents: (a) 0.4%, (b) 0.6%, (c) 0.8%, (d) 1.0%, and (e) 1.2%

In addition to being loaded repeatedly by traffic, roadways also suffer from high temperatures, especially during the paving and compacting process. As a result, to function properly on a road, BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites need to have certain temperature stability under complex and variable road environments. Fig. 18 shows the thermos gravimetry analysis (TGA) curves of BaTiO3/PVDF and BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites. It can be seen from Fig. 18 that there was no obvious mass loss of the two composites below 400°C, indicating that both composites can meet the requirements of the entire road environment from compaction to service life. Additionally, the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composite showed better thermal resistance than the BaTiO3/PVDF composite over the entire temperature range, especially above 500°C.

Figure 18: TGA curves of BaTiO3/PVDF and BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites

3.2.3 Effect of Conductive Carbon Black Content on Electrical Conductivities of BaTiO3/PVDF Composites

The electrical conductivity (σ), a reciprocal of resistivity, was adopted to examine the composites’ ability to conduct electricity. In this study, the conductive carbon black contents were chosen to be 0.4%, 0.6%, 0.8%, 1.0%, and 1.2% by mass of PVDF. Fig. 19 shows the relationship between σ values of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites and conductive carbon black contents at room temperature. As shown in Fig. 19, the addition of conductive carbon black dramatically improved the conductivities of the BaTiO3/PVDF composites, increasing the conductive carbon black content, especially when the conductive carbon black content was less than 0.6%. Compared with the BaTiO3/PVDF composites, the σ values of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites with 0.4% and 0.6% conductive carbon black by weight of PVDF increased by 45.8% and 58.1%, respectively. This phenomenon largely accounts for the fact that the added conductive carbon black particles are acted as tiny capacitors that shortened the moving distance of carriers and increased the conductive path in the composites. The conductivities of the composites were thus enhanced. A higher conductive carbon black content led to a more obvious conductivity of the composite. However, the punch-through phenomenon of composites is likely to occur when the conductive particle content in the composites exceeds a certain range. BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites will not become polarized and thus cannot have a high-voltage electrical property. Hence, the amount of conductive carbon black in the composites should have a maximum value.

Figure 19: The conductivities of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites with relationship to conductive carbon black content

3.2.4 Effect of Conductive Carbon Black Content on Dielectric Properties of BaTiO3/PVDF Composites

The dielectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites were evaluated using the relative dielectric constant (εr) and dielectric loss (tanδ), as shown in Fig. 20. The εr values of the composites first increased and then decreased with increasing conductive carbon black content. The increasing rate of εr values appears to be more significant before the 0.6% conductive carbon black by weight of PVDF. Compared with the BaTiO3/PVDF composite, the εr values of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites increased by 39.0% and 60.2%, respectively, when the conductive carbon black contents were 0.4% and 0.6% by weight of PVDF. This phenomenon was caused by the fact that the conductive carbon black, as a high dielectric constant material, improves the overall dielectric constant of the polymer matrix and thus reduces the difference in dielectric constant between the polymer matrix and piezoelectric ceramic, thereby optimizing the polarization efficiency and increasing the relative dielectric constant of the composites. The addition of conductive carbon black enhanced the conductivity of the composites, but the leakage current had a negative effect on the polarization process of the composites. This is the reason that the εr values decreased with increasing conductive carbon black content when the content was greater than 0.8% by mass of PVDF. During the polarization process, the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites could not be polarized due to the large leakage current when the conductive carbon black content exceeded 1.2% by weight of PVDF.

Figure 20: Effects of conductive carbon black content on the dielectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites

Fig. 20 also shows that the tanδ values of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites revealed a nearly linear increase with increasing conductive carbon black content. This is because the carriers in the dielectric material generated a flow of electric charge caused by an external electric field and then consumed electricity that was converted into heat. The tanδ values of the composites thus showed an upward trend with increasing conductive carbon black content until the large leakage current results in the composite not being polarized. However, the tanδ value of the composite is still less than 0.1, which is a small value for dielectric materials.

After considering the effect of conductive carbon black content on the conductivities and dielectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites, the optimum amount of conductive carbon black in the BaTiO3/PVDF composites is recommended to be 0.8% by weight of PVDF.

3.2.5 Effect of Conductive Carbon Black Content on Piezoelectric Properties of BaTiO3/PVDF Composites

The piezoelectric property of the BaTiO3/PVDF composite is mainly governed by the BaTiO3 material, but the piezoelectric property is limited because of the large difference in the dielectric constant between BaTiO3 and PVDF results in the fractional polarization of the composite. The addition of conductive carbon black can enhance the piezoelectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites. Fig. 21 shows the relationship between the piezoelectric properties of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites and the conductive carbon black content. It can be seen in Fig. 21 that the piezoelectric charge constant (d33) of the composites initially presented an upward trend and then dropped as the conductive carbon black content increased. The d33 value of the composite containing 0.8% conductive carbon black increased by 57.9% compared with the composites without conductive carbon black. This shows that conductive carbon black could significantly improve the piezoelectric performance of the composites, since the conductive carbon black can boost the dielectric constant of PVDF and narrow the gap in the dielectric constant between BaTiO3 and PVDF, indicating that the polarizability of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites can be vastly improved. The reinforcing effect achieved the maximum value when the carbon black content was 0.8%. The d33 values of the composites then decreased with increasing conductive carbon black content because the punch-through phenomenon of the composites has a negative effect on the piezoelectric property.

Figure 21: Effect of carbon black content on the piezoelectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites

Fig. 21 also illustrates the relationship between the piezoelectric voltage constant (g33), the ratio of the piezoelectric charge constant, and the dielectric constant (g33 = d33/ε), of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites and the conductive carbon black content. The changing range (19.9–23.9 mV*m/N) of g33 values was small when the conductive carbon black content ranged between 0.0% and 1.2% by weight of PVDF.

The dielectric and piezoelectric properties of BaTiO3/PVDF composites can be effectively enhanced by increasing the ceramic content and decreasing the grain size, but these properties cannot be simply improved by increasing the ceramic phase content and decreasing the ceramic size. The addition of conductive carbon black in the composites is an effective approach. In this study, the optimum ratio of BaTiO3 to PVDF was first determined by balancing the morphologies, dielectric properties, and piezoelectric performance of the BaTiO3/PVDF composites. Based on the optimum ratio of BaTiO3/PVDF composites, BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites were prepared with various conductive carbon black contents using the hot-press method. The effect of conductive carbon black content on the morphologies, thermal performance, conductivities, dielectric properties, and piezoelectric properties of the BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites was then examined. Finally, the following conclusions can be drawn from this study:

(1) The aggregation phenomenon appears in the BaTiO3/PVDF composites when the BaTiO3 content rises to 85%.

(2) The BaTiO3/PVDF composite with 70% BaTiO3 content by volume of the composite shows the best dielectric and piezoelectric properties.

(3) The conductive carbon black does not have an obvious effect on the morphologies and thermal stabilities of BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composites.

(4) The addition of conductive carbon black dramatically can improve the conductivities of BaTiO3/PVDF composites, especially when the conductive carbon black content is less than 0.6%.

(5) The BaTiO3/PVDF/conductive carbon black composite achieves the best dielectric and piezoelectric properties when the carbon black content is 0.8% by weight of PVDF.

Acknowledgement: This paper is supported by Innovative Talent Promotion Program of Shaanxi Province.

Funding Statement: We are grateful for the financial supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52178408), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFE0103800).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang, H., Jasim, A., Chen, X. (2018). Energy harvesting technologies in roadway and bridge for different applications–A comprehensive review. Applied Energy, 212, 1083–1094. DOI 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Omar, O. S. (2022). Monolayer MoS2/n-Si heterostructure schottky solar cell. Journal of Renewable Materials, 10(7), 1979–1988. DOI 10.32604/jrm.2022.018765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen, C., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Yang, D., Yao, F. et al. (2020). Additive manufacturing of piezoelectric materials. Advanced Functional Materials, 30(52), 2005141. DOI 10.1002/adfm.202005141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li, Y., Xing, X., Pei, J., Li, R., Wen, Y. et al. (2020). Automobile exhaust gas purification material based on physical adsorption of tourmaline powder and visible light catalytic decomposition of g-C3N4/BiVO4. Ceramics International, 46(8), 12637–12647. DOI 10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.02.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang, H., Xia, S., Ma, M., Li, Z. (2022). Anisotropic growth kinetics and electric properties of PZT-5H single crystal by solid-state crystal growth method. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 105(5), 3238–3251. DOI 10.1111/jace.18336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sezer, N., Koç, M. (2021). A comprehensive review on the state-of-the-art of piezoelectric energy harvesting. Nano Energy, 80, 105567. DOI 10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.105567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Safaei, M., Sodano, H. A., Anton, S. R. (2019). A review of energy harvesting using piezoelectric materials: State-of-the-art a decade later (2008–2018). Smart Materials and Structures, 28(11), 113001. DOI 10.1088/1361-665X/ab36e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Manbachi, A., Cobbold, R. S. (2011). Development and application of piezoelectric materials for ultrasound generation and detection. Ultrasound, 19(4), 187–196. DOI 10.1258/ult.2011.011027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang, B., Iocozzia, J., Zhao, L., Zhang, H., Harn, Y. W. et al. (2019). Barium titanate at the nanoscale: Controlled synthesis and dielectric and ferroelectric properties. Chemical Society Reviews, 48(4), 1194–1228. DOI 10.1039/C8CS00583D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Panda, P., Sahoo, B. (2015). PZT to lead free piezo ceramics: A review. Ferroelectrics, 474(1), 128–143. DOI 10.1080/00150193.2015.997146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shirane, G., Takeda, A. (1952). Phase transitions in solid solutions of PbZrO3 and PbTiO3 (I) small concentrations of PbTiO3. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan, 7(1), 5–11. DOI 10.1143/JPSJ.7.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jaffe, B., Roth, R., Marzullo, S. (1954). Piezoelectric properties of lead zirconate-lead titanate solid-solution ceramics. Journal of Applied Physics, 25(6), 809–810. DOI 10.1063/1.1721741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yang, J., Pan, P., Hua, L., Feng, X., Yue, J. et al. (2012). Effects of crystallization temperature of poly(vinylidene fluoride) on crystal modification and phase transition of poly(butylene adipate) in their blends: A novel approach for polymorphic control. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 116(4), 1265–1272. DOI 10.1021/jp209626x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Muravyev, N. V., Monogarov, K. A., Schaller, U., Fomenkov, I. V., Pivkina, A. N. (2019). Progress in additive manufacturing of energetic materials: Creating the reactive microstructures with high potential of applications. Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics, 44(8), 941–969. DOI 10.1002/prep.201900060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Subbaramaiah, R., Al-Jufout, S. A., Ahmed, A., Mozumdar, M. M. (2020). Design of vibration-sourced piezoelectric harvester for battery-powered smart road sensor systems. IEEE Sensors Journal, 20(23), 13940–13949. DOI 10.1109/JSEN.7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ahmad, S., Abdul Mujeebu, M., Farooqi, M. A. (2019). Energy harvesting from pavements and roadways: A comprehensive review of technologies, materials, and challenges. International Journal of Energy Research, 43(6), 1974–2015. DOI 10.1002/er.4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li, Y., Ma, X., Tang, H., Pei, J., Li, D. et al. (2021). Investigation on aging resistance of ternary compound carbon nitride (CN-Bi-Tr-DC) modified asphalt. Construction and Building Materials, 313, 125522. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li, Y., Dai, X., Pei, J. Z., Li, R., Zhang, J. P. et al. (2020). Investigation on preparation and rheological properties of grafted organic long-chain carbonitride (CNDC) modified asphalt. Construction and Building Materials, 262, 120539. DOI 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li, Y., Zhang, J., He, Y., Huang, G., Li, J. et al. (2022). A review on durability of basalt fiber reinforced concrete. Composites Science and Technology, 225, 109519. DOI 10.1016/j.compscitech.2022.109519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wen, Y., Wang, Y. (2019). Effect of oxidative aging on dynamic modulus of hot-mix asphalt mixtures. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 31(1), 04018348. DOI 10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang, J., Li, X., Liu, G., Pei, J. (2019). Effects of material characteristics on asphalt and filler interaction ability. International Journal of Pavement Engineering, 20(8), 928–937. DOI 10.1080/10298436.2017.1366765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wu, Y., Ma, Y., Zheng, H., Ramakrishna, S. (2021). Piezoelectric materials for flexible and wearable electronics: A review. Materials & Design, 211, 110164. DOI 10.1016/j.matdes.2021.110164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li, J., How, Z. T., Zeng, H., Gamal El-Din, M. (2022). Treatment technologies for organics and silica removal in steam-assisted gravity drainage produced water: A comprehensive review. Energy & Fuels, 36(3), 1205–1231. DOI 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c03751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Fu, J., Hou, Y., Zheng, M., Wei, Q., Zhu, M. et al. (2015). Improving dielectric properties of PVDF composites by employing surface modified strong polarized BaTiO3 particles derived by molten salt method. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 7(44), 24480–24491. DOI 10.1021/acsami.5b05344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lukacs, V., Airimioaei, M., Padurariu, L., Curecheriu, L., Ciomaga, C. et al. (2022). Phase coexistence and grain size effects on the functional properties of BaTiO3 ceramics. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 42(5), 2230–2247. DOI 10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2021.12.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lallart, M., Cottinet, P. J., Lebrun, L., Guiffard, B., Guyomar, D. (2010). Evaluation of energy harvesting performance of electrostrictive polymer and carbon-filled terpolymer composites. Journal of Applied Physics, 108(3), 034901. DOI 10.1063/1.3456084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Guan, X., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Ou, J. (2013). PZT/PVDF composites doped with carbon nanotubes. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 194, 228–231. DOI 10.1016/j.sna.2013.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sahoo, S., Krishnamoorthy, K., Pazhamalai, P., Mariappan, V. K., Manoharan, S. et al. (2019). High performance self-charging supercapacitors using a porous PVDF-ionic liquid electrolyte sandwiched between two-dimensional graphene electrodes. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 7(38), 21693–21703. DOI 10.1039/C9TA06245A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sahoo, S., Ratha, S., Rout, C. S., Nayak, S. K. (2022). Self-charging supercapacitors for smart electronic devices: A concise review on the recent trends and future sustainability. Journal of Materials Science, 57(7), 4399–4441. DOI 10.1007/s10853-022-06875-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang, C., Chi, Q., Dong, J., Cui, Y., Wang, X. et al. (2016). Enhanced dielectric properties of poly (vinylidene fluoride) composites filled with nano iron oxide-deposited barium titanate hybrid particles. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1–9. DOI 10.1038/srep33508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Guo, J., Tsou, C. H., Yu, Y., Wu, C. S., Zhang, X. et al. (2021). Conductivity and mechanical properties of carbon black-reinforced poly(lactic acid) (PLA/CB) composites. Iranian Polymer Journal, 30(12), 1251–1262. DOI 10.1007/s13726-021-00973-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li, R., Guo, Q., Shi, Z., Pei, J. (2018). Effects of conductive carbon black on PZT/PVDF composites. Ferroelectrics, 526(1), 176–186. DOI 10.1080/00150193.2018.1456308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Küçük, Ö., Teber, S., Kaya, İ. C., Akyıldız, H., Kalem, V. (2018). Photocatalytic activity and dielectric properties of hydrothermally derived tetragonal BaTiO3 nanoparticles using TiO2 nanofibers. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 765, 82–91. DOI 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.06.165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Nayak, S., Sahoo, B., Chaki, T. K., Khastgir, D. (2014). Facile preparation of uniform barium titanate (BaTiO3) multipods with high permittivity: Impedance and temperature dependent dielectric behavior. RSC Advances, 4(3), 1212–1224. DOI 10.1039/C3RA44815K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Jiang, X., Hao, H., Yang, Y., Zhou, E., Zhang, S. et al. (2021). Structure and enhanced dielectric temperature stability of BaTiO3-based ceramics by Ca ion B site-doping. Journal of Materiomics, 7(2), 295–301. DOI 10.1016/j.jmat.2020.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Paul, S., Kumar, D. (2013). Barium titanate as a ferroelectric and piezoelectric ceramics: Barium titanate as a ferroelectric and piezoelectric ceramics. Journal of Biosphere, 2(1), 55–58. [Google Scholar]

37. Teoh, G. H., Ooi, B. S., Jawad, Z. A., Low, S. C. (2021). Impacts of PVDF polymorphism and surface printing micro-roughness on super hydrophobic membrane to desalinate high saline water. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 9(4), 105418. DOI 10.1016/j.jece.2021.105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mishra, H. K., Gupta, V., Roy, K., Babu, A., Kumar, A. et al. (2022). Revisiting of δ–PVDF nanoparticles via phase separation with giant piezoelectric response for the realization of self-powered biomedical sensors. Nano Energy, 95, 107052. DOI 10.1016/j.nanoen.2022.107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sencadas, V., GregorioJr, R., Lanceros-Méndez, S. (2009). α to β phase transformation and microestructural changes of PVDF films induced by uniaxial stretch. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B, 48(3), 514–525. DOI 10.1080/00222340902837527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. El Achaby, M., Arrakhiz, F., Vaudreuil, S., Essassi, E., Qaiss, A. (2012). Piezoelectric β-polymorph formation and properties enhancement in graphene oxide–PVDF nanocomposite films. Applied Surface Science, 258(19), 7668–7677. DOI 10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.04.118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Layek, R. K., Samanta, S., Chatterjee, D. P., Nandi, A. K. (2010). Physical and mechanical properties of poly (methyl methacrylate)-functionalized graphene/poly(vinylidine fluoride) nanocomposites: Piezoelectric β polymorph formation. Polymer, 51(24), 5846–5856. DOI 10.1016/j.polymer.2010.09.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sun, Q., Xia, W., Liu, Y., Ren, P., Tian, X. et al. (2019). The dependence of acoustic emission performance on the crystal structures, dielectric, ferroelectric, and piezoelectric properties of the P(VDF-TrFE) sensors. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 67(5), 975–983. DOI 10.1109/TUFFC.2019.2959353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools