Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Near Term Hybrid Quantum Computing Solution to the Matrix Riccati Equations

1 Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, 91711, USA

2 Marist College, Poughkeepsie, 12601, USA

* Corresponding Author: Augusto González Bonorino. Email:

Journal of Quantum Computing 2022, 4(3), 135-146. https://doi.org/10.32604/jqc.2022.036706

Received 10 October 2022; Accepted 07 April 2023; Issue published 03 July 2023

Abstract

The well-known Riccati differential equations play a key role in many fields, including problems in protein folding, control and stabilization, stochastic control, and cybersecurity (risk analysis and malware propagation). Quantum computer algorithms have the potential to implement faster approximate solutions to the Riccati equations compared with strictly classical algorithms. While systems with many qubits are still under development, there is significant interest in developing algorithms for near-term quantum computers to determine their accuracy and limitations. In this paper, we propose a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm, the Matrix Riccati Solver (MRS). This approach uses a transformation of variables to turn a set of nonlinear differential equation into a set of approximate linear differential equations (i.e., second order non-constant coefficients) which can in turn be solved using a version of the Harrow-Hassidim-Lloyd (HHL) quantum algorithm for the case of Hermitian matrices. We implement this approach using the Qiskit language and compute near-term results using a 4 qubit IBM Q System quantum computer. Comparisons with classical results and areas for future research are discussed.Keywords

Quantum computing is an emerging field which utilizes the principles of quantum physics to perform computations in fundamentally different ways from classical computers. For certain problems, quantum algorithms offer significant improvements in execution time over their classical counterparts. One of the most famous examples is Shor’s algorithm for factoring large (100–200 digit) numbers into the product of two primes, thus making it possible to break modern public-private key encryption schemes [1]. While the theoretical basis of this field has been understood for many decades, only within the past few years have small working quantum computers become available. One of the largest currently available quantum computers is the IBM Q System One, which is programmed using the Qiskit language [2]. Much of the near-term research in this field involves proof of concept implementations, which are limited by the scalability of current quantum computer hardware. Nevertheless, it’s critical to study these applications at a small scale now, in preparation for larger quantum computers becoming available within the next few years (current systems are limited to a handful of qubits; however, IBM roadmaps plan for a 1,000-qubit machine by 2024 or sooner [3]). For example, IBM has recently announced quantum resistant encryption features on the latest model z16 enterprise server [4], even though we are years away from building a large enough quantum computer to seriously threaten conventional encryption.

While there are currently only a few known examples where quantum computers offer a potential performance advantage, one promising area is the solution of systems of linear differential equations. For this problem, it has been shown [5] that under certain conditions, quantum algorithms can yield an exponential improvement in execution time compared with the best-known classical algorithms. In this paper, we investigate the use of quantum algorithms to generate approximate solutions to systems of nonlinear differential equations. Our approach involves a transformation which turns a set of nonlinear differential equations into an approximation using linear differential equations with second order non-constant coefficients. We can then solve a matrix representing this set of linear differential equations using a version of the Harrow-Hassidim-Lloyd (HHL) quantum algorithm, for the common case of Hermitian matrices.

Specifically, we are interested in the well-known Matrix Riccati nonlinear differential equations [6], which play a role in a wide range of fields including problems in protein folding, control and stabilization, stochastic control, and cybersecurity (risk analysis and malware propagation) [7–10]. These equations have been studied extensively using classical computing techniques, including significant efforts by national research labs [11], and approximate solutions with varying degrees of accuracy have been demonstrated. We propose a novel hybrid quantum-classical algorithm, the Matrix Riccati Solver (MRS), which is implemented on a near-term 4 qubit quantum computer using Qiskit. We then compare the accuracy achievable with the MRS and conventional approaches over a limited neighborhood of values. It is possible to achieve useful accuracy with this approach, and future quantum computers with additional qubits are expected to offer even better performance.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Following a short introduction, we describe the fundamental Riccati equation formulations, the quantum linear systems problem, and the HHL algorithm. We then describe our implementation of the MRS hybrid algorithm, and present experimental results running on a 4-qubit quantum computer. We compare the MRS results with the best available classical approximations and suggest areas for further research.

2 Riccati Equations Fundamentals

In general, a Riccati equation is any first order ordinary differential equation that is quadratic in the unknown function, such as equations of the form

where a(t), b(t) and c(t) are nonzero, continuous functions of t. More generally, the term Riccati equation is used to refer to matrix equations with an analogous quadratic term, which occur in both continuous-time and discrete-time linear quadratic Gaussian control systems. The steady-state (non-dynamic) version of these is referred to as the algebraic Riccati equation. The non-linear Riccati equation can always be converted to a second order linear ordinary differential equation (ODE).

To date, there is no general approach for finding solutions to the Riccati equations, although there are analytical techniques which allow solutions under certain conditions as well as numerical approximation solutions for other cases. For example, suppose we have a particular solution y1 to this general equation. Then we can make the following change of variables

and so, we can rewrite the general equation as

It follows that, since y1 is a particular solution to the Riccati equation we can cancel out

Note that u′ is a Bernoulli equation and thus we can apply well-established methods to find the general solution. First, we make the substitution z = u1−m, where m = 2 in this case, to transform the Bernoulli into the following linear differential equation:

We will expand these methods to a matrix formalism, which is the standard approach used in quantum computing state machines.

3 Quantum Linear Systems Problem

The “Classical” Linear System Problem (LSP) states the following:

Given an N × N matrix A, an N–dimensional vector

Solve for

Analogously, the Quantum Linear System Problem (QLSP) states that given a Hermitian Given an N × N matrix A, an N –dimensional vector

Prepare a quantum state that approximates the column vector

where

The Harrow-Hassidim-Lloyd (HHL) quantum algorithm [3] may be applied to expressions like those we developed in the previous section. Given a Hermitian matrix A, the HHL algorithm will compute the vector of unknowns

where

• Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE)

• Invert the eigenvalues

• Measurement

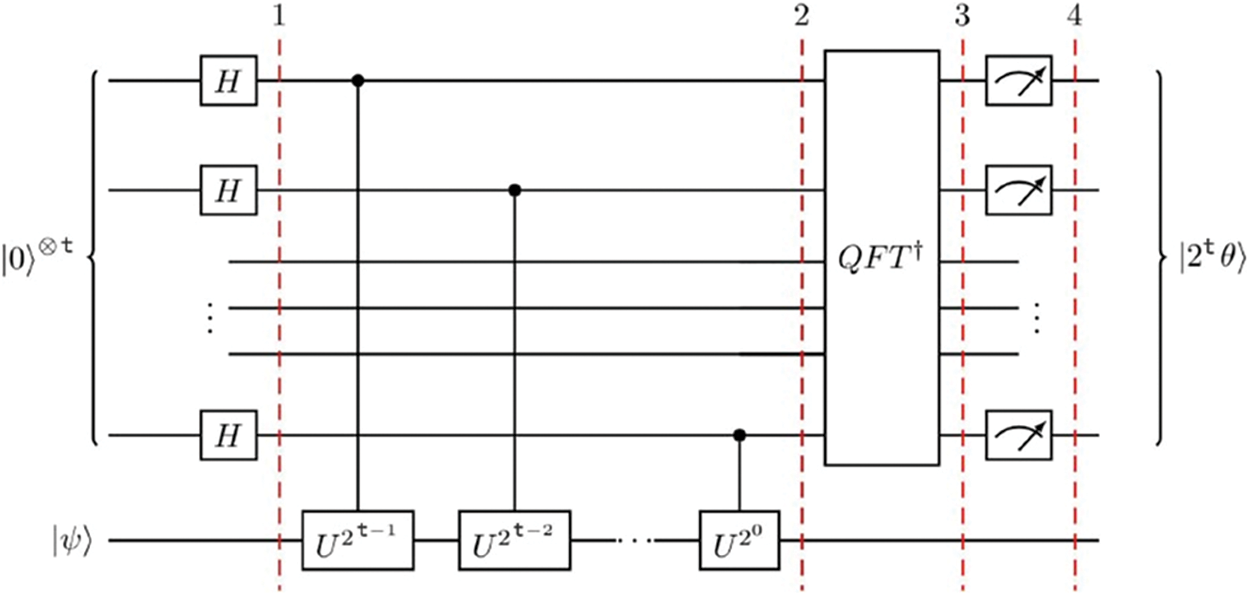

QPE is a central building block for many quantum algorithms. As shown in the quantum circuit of Fig. 1, QPE estimates the phase of an eigenvalue of the unitary operator U that we create by using the properties of Hermitian matrices. Given a unitary operator, U, QPE estimates the phase angle theta in

where

Figure 1: Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) circuit using quantum fourier transform (QFT), hadamard gates (H), and various unitary transforms (U)

A quantum circuit for this algorithm is shown in Fig. 2, incorporating the QPE circuit from Fig. 1 and leveraging the lin_alg package from Qiskit so that we can treat the HHL algorithm as a black box.

Figure 2: Quantum circuit for the HHL algorithm

After encoding the solution vector

5 The Matrix Riccati Solver (MRS)

We propose a hybrid algorithm, the Matrix Riccati Solver (MRS), to find solutions for the matrix form of these equations given a set of initial conditions. First, we show that some Matrix Riccati equation can be re-written as a Hermitian matrix, given certain conditions are met, and encode this fact in the classical component of the proposed algorithm. Then, we feed the Hermitian matrix to HHL on IBM’s 4-qubit near-term quantum computer to obtain the solution.

Let R denote the following Matrix Riccati equation

where Y ∈ ℝn × m, D(t) ∈ ℝn × m, C(t) ∈ ℝn × n, B(t) ∈ ℝm × m and A(t) ∈ ℝm × n. The goal is, given an initial condition Y(0), to obtain solutions Y(t), ∀ t > 0.

We propose the following theorems (see Appendix for full proof):

Theorem 1: Assuming m = n, if B(t) = 0 and if A(t) is invertible, then Eq. (17) can be converted to the following second order matrix differential equation:

By using the change of variables Y = − A−1 ⋅ u′ ⋅ u−1, where u is invertible.

Theorem 2: If ACA−1 + A′A−1 = S where S is a matrix with constant entries and diagonalizable, and

A ⋅ D = −I , then (18) can be converted into the following equations:

where D1 is a diagonal matrix.

From (18) we derive the following linear system

where M11 = 0, M12 = 1, M21 = 1, M22 = −αi, and αi denotes the entries in the diagonal matrix D1,

wii = [vii (0), v′ ii (0)]T, where vij are the entries of v so v = (vij) and 1 ≤ i, j ≤ n .

Solving (20) is equivalent to solving the system

where

where A(t), B(t), C(t) are real-valued functions of t. We seek to compute y(t) given an initial condition y(0). We convert the Riccati equation to a second order differential equation by applying the change of variables

Such that we obtain the following equation:

Next, let

From this, we obtain a system with vector of unknowns

and thus, the corresponding eigenvectors are:

Finally, we construct a 2 × 2 passage matrix P = (V1, V2), such that we can rewrite our matrix M as H = P ⋅ D ⋅ P−1 where D is a diagonal matrix with entries λi.

It follows that to solve this system we must compute

Figure 3: Matrix Riccati Solver (MRS) algorithm’s pseudocode

The MRS checks that the required conditions are met. If not, the program displays an error and halts. To ensure that α is a constant MRS checks its derivative equals zero and then registers the variable as a constant quantity using the Python package SimPy constant quantity [13]. Then, MRS computes the eigenvalues λi of the system of equations we derived in the previous section. The eigenvalues are then utilized to compute the values of each component in our new matrix . We solve for

We can then input M and

To test the algorithm’s performance, we used the following example. Consider the following Riccati equation with initial condition y(0) = 1

Recall the Uniqueness and Existence theorem [2] states that there is a unique solution for a given initial value problem within a local neighbourhood, defined by ε > 0 . Fig. 4 shows the results of both the quantum solution (i.e., Matrix Riccati Solver) and classical solution over the local neighborhood (0.30, 0.38) with a time step of 0.001.

Figure 4: Comparison of classical solution and hybrid quantum-classical MRS solution

The accuracy of the quantum algorithm varies from a nearly exact solution near the edges of this neighborhood to a worst-case error of −1.444 at T = 0.3570. For some applications this is an acceptable error tolerance; in other cases, such as risk assessment analysis, the quantum algorithm will slightly under-estimate risk factors over this neighborhood. This error is likely attributed to the relatively small number of qubits used in the near-term approximate solution. Although there will always be some error due to quantum fluctuations, future quantum computers are expected to provide a better approximation of the classical solution over a larger neighborhood.

We propose a hybrid classical-quantum algorithm to generate solutions to nonlinear differential equations, specifically the Riccati equations, by approximating them as a series of linear differential equations. Previous research indicates that quantum assisted solutions should provide an exponential speedup in execution time. Although this may not be fully realized using near-term quantum computers, we investigate algorithms which can be scaled to larger numbers of qubits in future systems. Near term results indicate that over neighborhoods of interest the hybrid MRS algorithm offers good accuracy for a number of applications. Additional research is planned to investigate larger quantum computers as they become commercially available.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the Mathematics and Computer Science department at Marist College for supporting our academic endeavors with insightful conversations and advice.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. P. Shor, “Polynomial time algorithms for prime factorization and discrete logarithms on a quantum computer,” SIAM Journal on Computing, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1484–1509, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1137/S0097539795293172 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. A. Asfaw, L. Bello, Y. Ben-Haim, S. Bravyi, N. Bronn et al., “Learn quantum computing using Qiskit,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://community.qiskit.org/textbook [Google Scholar]

3. J. Hruska, “IBM unveils quantum roadmap, plans 1,000 qubit chips by 2023,” English. 2020. Available: https://www.extremetech.com/computing/315020-ibm-unveils-quantum-roadmap-plans-1000-qubit-chip-by-2023 [Google Scholar]

4. IBM, “Announcing IBM z16: Real-time AI for Transaction Processing at Scale and Industry’s First Quantum- Safe System,” 2022. Available: https://newsroom.ibm.com/2022-04-05-Announcing-IBM-z16-Real-time-AI-for-Transaction-Processing-at-Scale-and-Industrys-First-Quantum-Safe-System? [Google Scholar]

5. A. W. Harrow, A. Hassidim and S. Lloyd, “Quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations,” Physical Review Letters, vol. 103, no. 15, pp. 150502, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.150502 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. R. Haberman, “Applied Partial Differential Equations with Fourier Series and Boundary Value Problems,” in English, 5th ed., London, UK: Pearson, 2018. [Google Scholar]

7. A. Mohammadi and M. Spong, “Quadratic optimization based nonlinear control for protein conformation prediction,” IEEE Control Systems Letters, vol. 6, pp. 2755–2760, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1109/LCSYS.2022.3176433 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. A. Anees and I. Hussain, “A novel method to identify initial values of chaotic maps in cybersecurity,” Symmetry, vol. 11, no. 2140, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11020140 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. W. Zhongru, L. Chen, S. Song, C. Pei Xin and R. Qiang, “Automatic cybersecurity risk assessment based on fuzzy fractional ordinary differential equations,” Alexandria Engineering Journal, vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 2725–2731, 2020. [Google Scholar]

10. L. Lystad, N. Per-Ole and H. Ralph, “The Riccati equation–an economic fundamental equation which describes marginal movement in time,” Modeling, Identification and Control, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 3–21, 2006. https://doi.org/10.4173/mic.2006.1.1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory research brief, “NSDE: Nonlinear solvers and differential equations,” 2005. [Online]. Available: https://computing.llnl.gov/projects/nsde (accessed on 08/20/2022). [Google Scholar]

12. M. Hestenes and E. Stiefel, “Methods of conjugate gradients for solving linear systems,” Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 409, 1952. https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.049.044 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. A. Meurer, M. Paprocki, C. P. Smith, O. Čertik, S. B. Kirpichev et al., “SymPy: Symbolic computing in Python,” PeerJ Computer Science, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. e103, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Appendix

Let R denote the following Matrix Riccati equation

where Y ∈ ℝn × m, D(t) ∈ ℝn × m, C(t) ∈ ℝn × n, B(t) ∈ ℝm × m and A(t) ∈ ℝm × n.

Theorem 1: Assume m = n. If B(t) = 0 and if A(t) is invertible, then (R) can be converted to the following second order differential equation:

By using the change of variables Y = −A−1 ⋅ u′ ⋅ u−1, where u is invertible.

Proof.

Recall (A−1)′ = − A−1 ⋅ A′ ⋅ A−1. Then,

It follows that, since B(t) = 0

and so

By right multiplying by u we get

Then, left multiply by A

Which yields

Theorem 2: If A ⋅ C ⋅ A−1 + A′ ⋅ A−1 = S , where S is constant and diagonalizable, and A ⋅ D = − I.

Then, (A1) can be converted to the following equation

where D1 denotes a diagonal matrix.

Proof.

We know the S is diagonalizable, thus we can rewrite it as S = P ⋅ D1 ⋅ P−1 where P denotes the passage matrix P−1 ⋅ S = D1 ⋅ P−1. Next, let F denote the following equation:

By left multiplying both sides by P−1 we get

or

Finally, let v = P−1 ⋅ u which yields

Obtaining the system from (A15)

Let αi denote the eigenvalues of

Next, let Vij ∈ ℝ, 1 ≤ i ≤ n and 1 ≤ j ≤ n be the entries of v. Then, (A15) leads to

Now, notice that vii = vij since αi does not depend on j. Thus, we get

Next, let

To find the solution to (A18) we solve for

Computing e−tMi

Let

If we multiply both sides by -t and exponentiate we obtain the following equation

And therefore the following matrix:

Normalizing the solution vector

For the input system to be valid, HHL requires that the solution vector

Let

Since

Expressed as sums instead of matrix notation

We know apply the normalization condition

where

Putting everything together yields the solution

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools