DOI:10.32604/iasc.2021.017586

| Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing DOI:10.32604/iasc.2021.017586 |  |

| Article |

Parameter Estimation of Alpha Power Inverted Topp-Leone Distribution with Applications

1High Institute for Management Sciences, Belqas, 35511, Egypt

2Faculty of Graduate Studies for Statistical Research, Cairo University, Giza, 12613, Egypt

3Faculty of Business Administration, Delta University for Science and Technology, Mansoura, 11152, Egypt

4Faculty of Commerce, Mansoura University, Mansoura, 35516, Egypt

*Corresponding Author: Ehab M. Almetwally. Email: ehabxp_2009@hotmail.com

Received: 03 February 2021; Accepted: 21 March 2021

Abstract: We introduce a new two-parameter lifetime model, referred to alpha power transformed inverted Topp-Leone, derived by combining the alpha power transformation-G family with the inverted Topp-Leone distribution. Structural properties of the proposed distribution are implemented like; quantile function, residual and reversed residual life, Rényi entropy measure, moments and incomplete moments. The maximum likelihood, weighted least squares, maximum product of spacing, and Bayesian methods of estimation are considered. A simulation study is worked out to evaluate the restricted sample properties of the proposed distribution. Numerical results showed that the Bayesian estimates give more accurate results than the corresponding other estimates in the majority of the situations. The flexibility of the suggested model is demonstrated given some applications related to reliability, medicine, and engineering. A real data set is used to illustrate the potentiality of the alpha power transformed inverted Topp-Leone distribution compared to inverted Topp-Leone, inverse Weibull, alpha power inverse Weibull, inverse Lomax, alpha power inverse Lomax, inverse exponential, and alpha power exponential distributions. Criteria measures and their results showed that the suggested distribution is the best candidate for the considered data sets. The alpha power transformed inverted Topp-Leone distribution operates well for lifetime modeling.

Keywords: Inverted Topp-Leone; moments; maximum likelihood; maximum product spacing; weighted least squares; Bayesian estimation; MCMC

In recent times, probability distributions play a significant role in modeling naturally occurring phenomena. In fact, the statistics literature contains hundreds of continuous univariate distributions and their successful applications. However, there still remain many real-world phenomena involving data, which do not follow any of the traditional probability distributions. So, several attempts are introduced by many researchers to provide more flexibility to a family of distributions. Mahdavi et al. [1] introduced the alpha power transformation (AP) technique by adding an extra shape parameter to well- known baseline distributions. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the AP method is defined by:

Relevant works have been provided based on the AP method, for instance; AP Weibull distribution [2], AP generalized exponential distribution [3], AP extended exponential distribution [4], AP Lindley distribution [5], AP power Lindley distribution [6], AP inverse Lindley distribution [7], AP exponentiated Lomax distribution [8] and AP inverse Lomax distribution [9].

The inverted distributions were suggested in the literature using the inverse transformation of probability distributions. These distributions display different features in the behavior of the density and hazard rate shapes. They allow applicability to the phenomenon in many fields such as; biological sciences, life testing problems, survey sampling, and engineering sciences. Inverted distributions and their applications were discussed by several authors (see [10–18]).

In Hassan et al. [18], the CDF and the probability density function (PDF) of the inverted Topp-Leone (ITL) distribution with shape parameter

and,

In this paper, we propose a new two-parameter related to the ITL distribution depending on the AP family. We call it alpha power inverted Topp Leone (APITL) distribution. The basic motivations to introduce the APITL model are (i) Generalizing a new useful version of the ITL distribution based on the APT method along with deriving its statistical properties, (ii) Providing flexible PDF with right-skewed and uni-modal shapes, (iii) Modeling decreasing, increasing, upside-down hazard rate function (HRF), and (iv) Introducing some real applications in some areas.

This paper is constructed as follows. Section 2 describes the APITL distribution. Section 3 gives some structural properties of the APITL distribution. Section 4 gives the maximum likelihood (ML), the weighted least squares (WLS), the maximum product of spacing (MPS), and Bayesian estimators. Section 5 examines the effectiveness of the proposed estimates through a numerical illustration. Data analyses and some concluding remarks are employed, consequently, in Sections 6 and 7.

In this section, based on the AP family we introduce a new probability distribution related to the ITL distribution. We define the PDF, CDF, HRF and cumulative HRF of the APITL distribution.

Definition 2.1

A random variable X is said to have the APITL distribution when we substitute the CDF (Eq. (2)) and PDF (Eq. (3)) in CDF (Eq. (1)). The CDF of a random variable X has the APITL distribution with parameters

The PDF related to Eq. (4) is given by:

Descriptive PDF plots of the APITL distribution for some choices of parameters are represented in Fig. 1. It can be seen that the PDF of APITL distribution is uni-modal as well as possesses a long tail right-skewed.

Figure 1: The PDF plots of the APITL distribution

Definition 2.2

The reliability function and the HRF of X are given by:

and

An illustration of the HRF plots for the APITL distribution, for some choices of

Figure 2: The HRF of the APITL distribution

Here, we give some statistical properties.

The APITL distribution is simulated by inverting CDF Eq. (4) as follows:

The uth quantile for the APITL random variable is obtained by solving F(x) = u for x as follows:

where,

where Q(.) is the APITL quantile function. The Moor’s kurtosis is given as:

Skewness and kurtosis plots of the APITL model, based on the quantiles, are exhibited in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: 3D Plots of (a) Skewness and (b) Kurtosis of the APITL distribution

Moments of a probability distribution are crucial to deduce its properties such as measures of central tendency, dispersion, skewness, and kurtosis. The ordinary rth moment of the APITL distribution is derived. The rth moment of the APITL distribution is obtained from Eq. (5) as follows:

Since the power series representation is written as:

Using the power series expansion Eq. (13) in Eq. (12), then we get

Using the binomial expansion in Eq. (14) then

After using binomial expansion, then the rth moment is given by:

where,

The first four moments, for r = 1, 2, 3 and 4, of the APITL distribution are obtained from Eq. (16). The rth central moment

Values of mean

Table 1: Some moments values of the APITL distribution for specific values of parameters

We concluded from Tab. 1 that, as the value of

3.3 The Probability Weighted Moments

The class of probability-weighted moments (PWMs), denoted by

Substituting Eq. (4), and Eq. (5) in Eq. (18), further using expansion Eq. (13) and binomial expansion in Eq. (18), then the PWM of the APITL distribution is obtained as follows:

where,

3.4 Residual and Reversed Residual Life

The mth moment of the residual life (RLe), say

Therefore, the mth moment of RLe for APITL distribution is obtained by substituting PDF Eq. (5) in Eq. (20), then employing binomial expansions and Eq. (13) as follows:

where

where,

The mean of RRLe serves as the waiting time elapsed since the failure of an item on the condition that this failure had occurred.

The entropy of a random variable measures the amounts of information (or uncertainty) contained in a random observation; i.e., large value of entropy indicates higher uncertainty in the data. Rényi entropy of X, for

Substituting PDF Eq. (5) in Eq. (23), we obtain Rényi entropy of the APTIL model as follows:

From Eq. (24), and after simplification, the Rényi entropy of the APITL distribution will be:

where,

4 Parameter Estimation of the APITL Model

In this section, we deal with parameter estimators of the APITL distribution based on ML, WLS, MPS, and Bayesian estimation methods.

Let X1,…, Xn e the observed values from the APITL distribution with parameters

Then the log-likelihood function, say

Therefore, the ML equations are given by:

and,

Solving the non-linear equations

Let X1,…, Xn be a simple random sample from the APITL distribution and let X(1)< X(2)<…<X(n) be the associated order statistics. The WLS estimators of

where

The MPS method is an alternative procedure of the ML method which provides a parameter estimate of continuous distribution. The MPS estimators of

Solving the non-linear equations

and,

Equating Eqs. (33) and (34) with zero and using optimization algorism (conjugate-gradient or Newton-Raphson optimization) we get the solution.

Here, we get the Bayesian estimator of the APITL parameters. The Bayesian estimator is regarded under symmetric (squared error loss function (SELF)) which is defined as

To elicit the hyper-parameters of the informative priors, the ML estimator for

where,

From Eqs. (26) and (35), the joint posterior of the APITL distribution with parameters

To obtain the Bayesian estimators, we can use the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach. A useful sub-class of the MCMC techniques is the Gibbs sampling and more general Metropolis within Gibbs samplers. The Metropolis-Hastings (MH) algorithm along with the Gibbs sampling are the two most popular examples of the MCMC method. We use the MH within Gibbs sampling steps to generate random samples from conditional posterior densities of α and λ as follows:

and

The Bayesian estimators are obtained via SELF and LINEX loss function (for more information see [19–23]).

A Monte-Carlo simulation study was conducted to evaluate and compare the behavior of the different estimates based on mean square errors (MSEs) and biases. Generate 10000 random samples of sizes n = 50, 100, 150 and 200 from APITL distribution. Different actual parameter values were considered.

We calculated the ML estimate (MLE), WLS estimate (WLSE), MPS estimate (MPSE), and Bayesian estimate (BE) of

1. The bias and MSE for all estimates decrease as n increases (see Tabs. 2 and 3).

2. As values of

3. For a fixed value of

4. For a fixed value of

5. The measures of WLSEs are better than MLEs and MPSEs with decreasing sample size.

6. The measures of MPSEs are preferable to MLEs and WLSEs with sample sizes.

7. The BEs under the LINEX loss function is preferable to the other estimates.

Table 2: Biases and MSEs of the APITL distribution under different methods

Table 3: Biases and MSEs of the APITL distribution under different methods

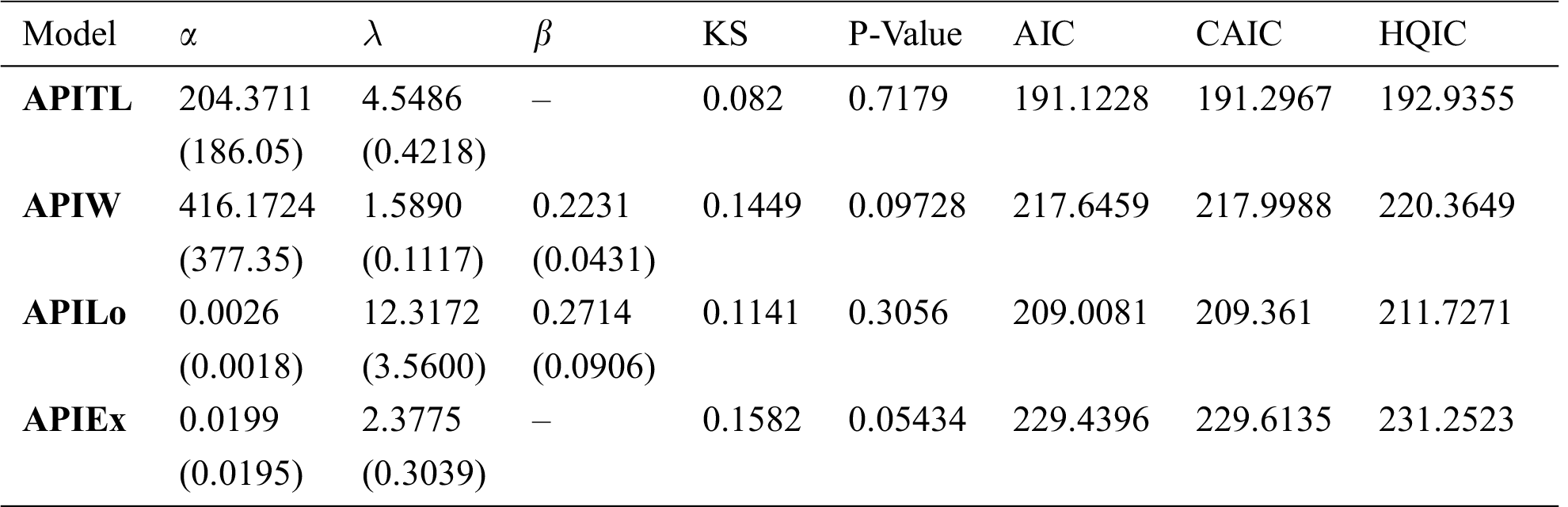

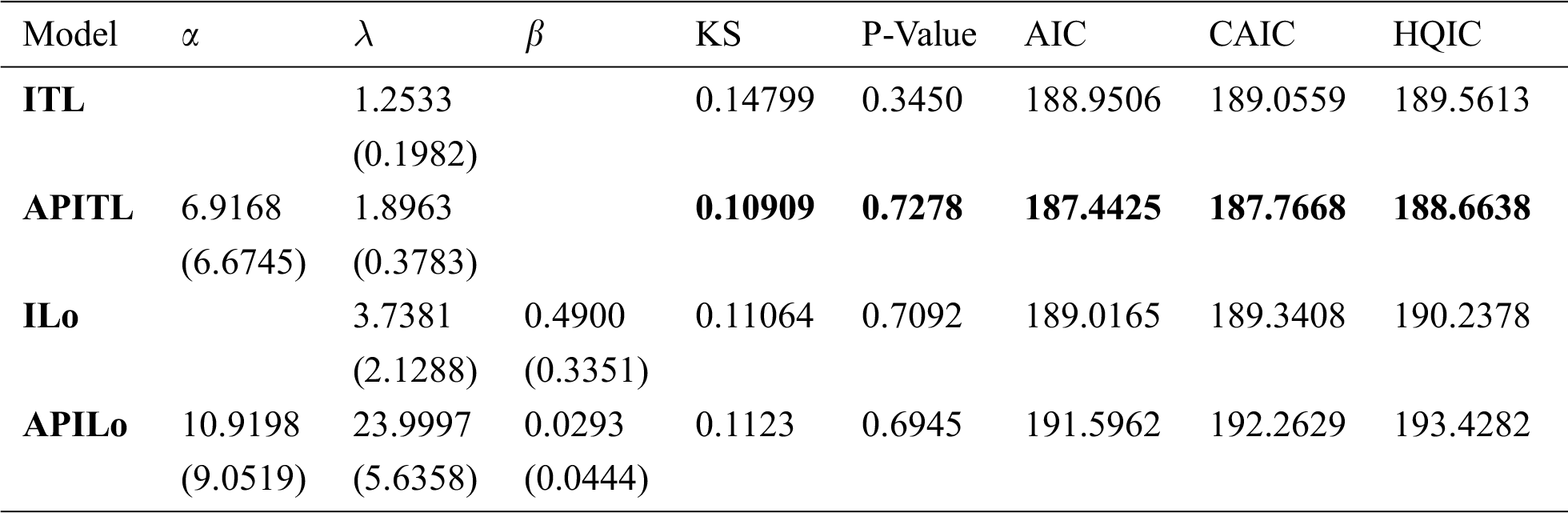

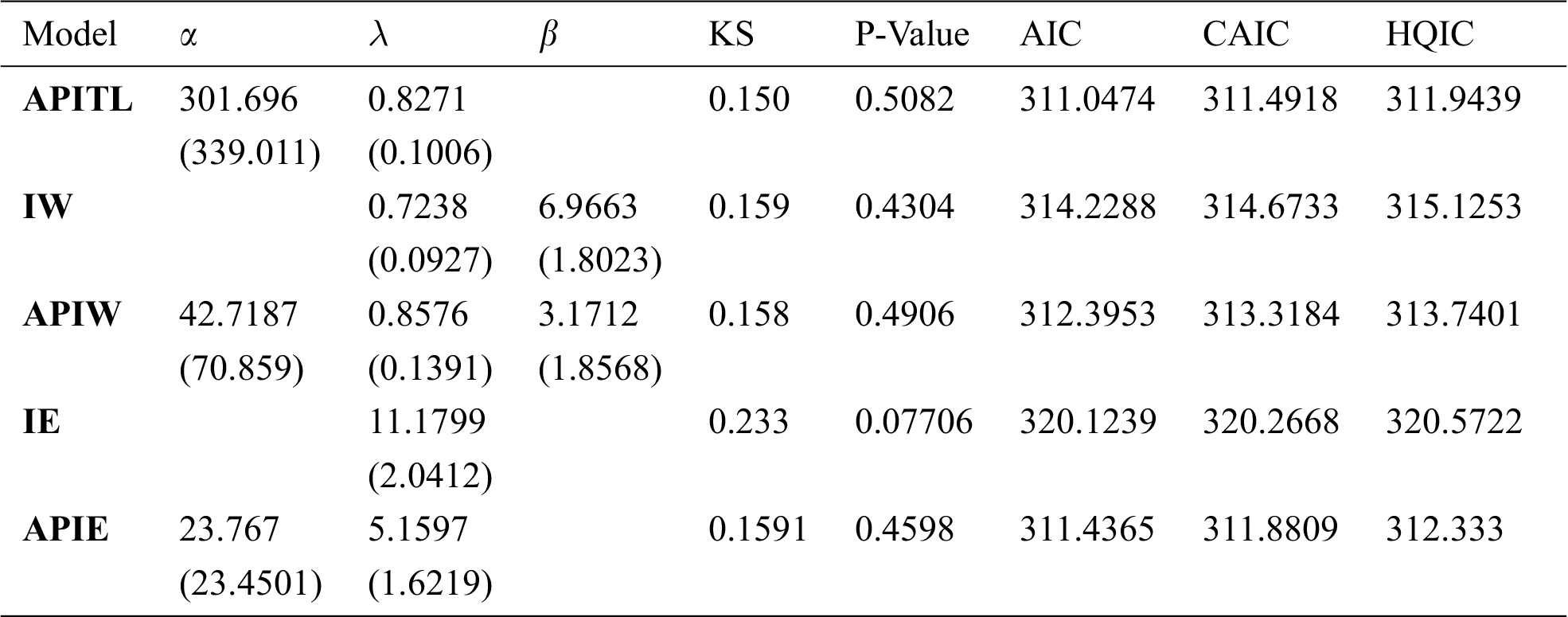

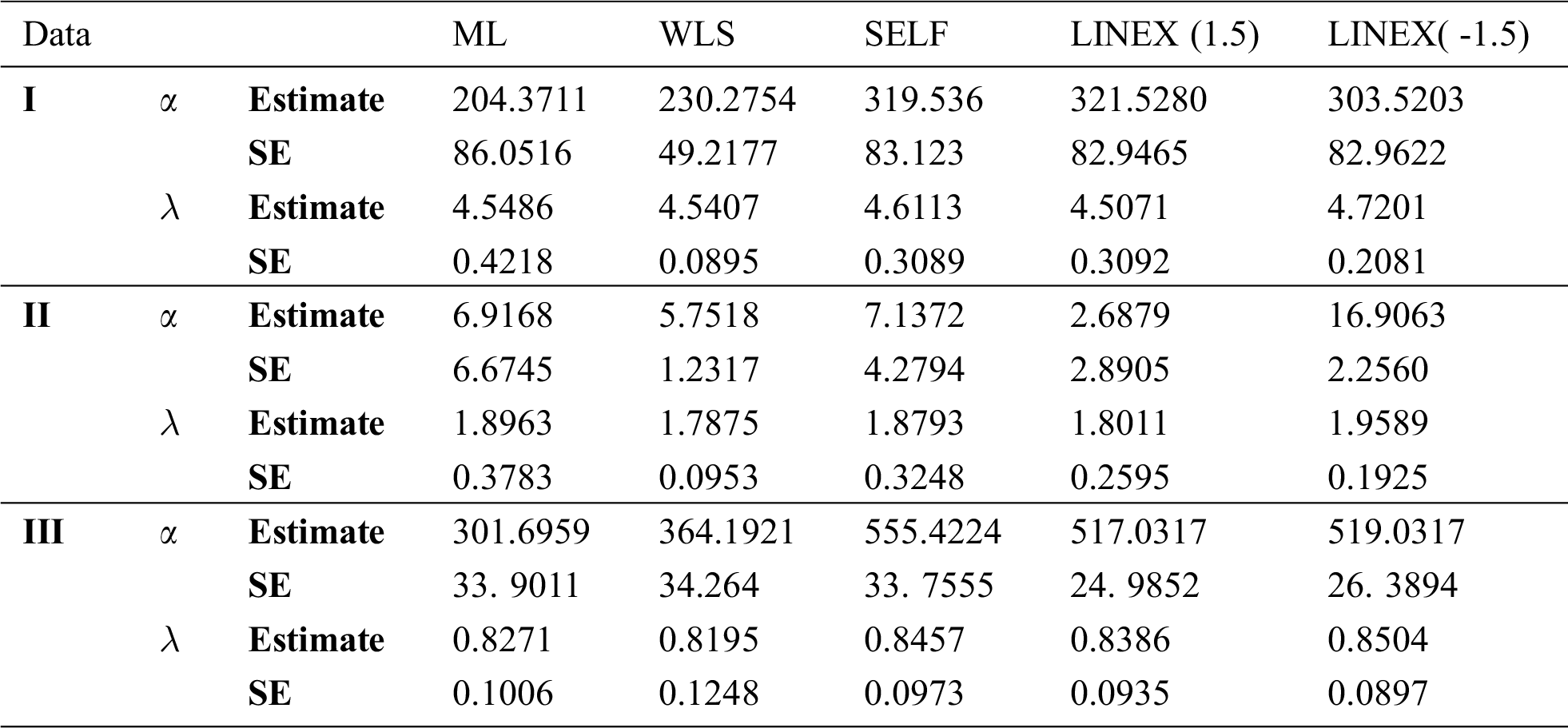

Here, we fit the APITL distribution under three real data taken from fields of survival times of medicine, engineering, and reliability. The APITL model is compared to other competitive models as, ITL, inverse Weibull (IW), alpha power IW (APIW), inverse Lomax (ILo), alpha power ILo (APILo), inverse exponential (IEx), and alpha power inverse exponential (APIEx) distributions.

Tabs. 4–6 provide values of Akaike information criterion (AIC), corrected AIC (CAIC), Hannan-Quinn information criterion (HQIC), and Kolmogorov- Smirnov (KS) statistic along with its P-value for all fitted models for three real data. In addition, these tables contain the MLEs and standard errors (SEs) (appear in parentheses) of the parameters for the considered models. We compared the fits of the APITL model with the ITL, IW, APIW, ILo, APILo, IEx, and APIEx models (see Tabs. 4–6). The fitted APITL PDF, CDF, PP-plot and QQ-plot of the three real data were displayed in Figs. 4–6, respectively. These figures indicated that the APITL distribution has the smallest values of AIC, CAIC, HQIC, KS and the largest P-value among all fitted models.

The first (I) set of data was studied in Bjerkedal [24]. It represents the rth survival times (in days) of 72 guinea pigs infected with virulent tubercle bacilli. These data were analyzed in Refs. [25,26]. Tab. 4 listed values of MLEs and statistic measures for data I. Fig. 4 provided estimated PDF, CDF, PP-plot, and QQ-plot of APITL distribution for data I.

The second (II) set of data represents the active repair times (hr) for an airborne communication transceiver [27]. The data are as follows: 0.50, 0.60, 0.60, 0.70, 0.70, 0.70, 0.80, 0.80, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.00, 1.10, 1.30, 1.50, 1.50, 1.50, 1.50, 2.00, 2.00, 2.20, 2.50, 2.70, 3.00, 3.00, 3.30, 4.00, 4.00, 4.50, 4.70, 5.00, 5.40, 5.40, 7.00, 7.50, 8.80, 9.00, 10.20, 22.00 and 24.50. The MLEs and statistic measures for data II listed in Tab. 5. Fig. 5 provided estimated PDF, CDF, PP-plot, and QQ-plot of the APITL model for data II.

The third (III) set of data was studied in Aarset [28]. It refers to 30 failure times of air-conditioning system of an airplane. Tab. 6 listed values of MLEs and statistic measures for data III. Fig. 6 provided estimated PDF, CDF, PP-plot and QQ-plot of the APITL for data III.

Table 4: MLEs, SEs, and statistic measures for data I

Figure 4: Estimated PDF, CDF, PP-plot and QQ-plot of the APITL model for data I

Figure 5: Estimated PDF, CDF, PP-plot, and QQ-plot of the APITL model for data II

Figure 6: Estimated PDF, CDF, PP-plot, and QQ-plot of the APITL model for data III

Table 5: MLEs, SEs, and statistic measures for data II

According to tables and Figs. 4–6, we observed that the APITL distribution provides well overall the fitted model and consequently could be selected as the more suitable model than other models.

Furthermore, the suggested methods of estimation (see Section 4) for the APITL parameters were considered based on the three data. Tab. 7 displayed different estimates of the APITL parameters for the three data sets. In these data, we cannot use the MPS method because there are equal observations in the data and consequently the spacing followed by the product will be zeros. For more information about this method see [29,30].

Table 6: MLEs, SEs, and statistic measures for data III

Table 7: Different estimates of the APITL parameters for real datasets

The convergence of the MCMC estimation of

Figure 7: Convergence of the MCMC estimation of α and λ for data I

Figure 8: Convergence of the MCMC estimation of α and λ for data II

Figure 9: Convergence of the MCMC estimation of α and λ for data III

We proposed and studied the alpha power transformed inverted Topp-Leone distribution. Some structural properties of the APITL distribution were provided. Bayesian and non-Bayesian methods of estimation were considered. We obtained the ML, WLS, and MPS estimators of the population parameters. The Bayesian estimator was deduced under LINEX and SELF. The Monte Carlo simulation study was worked out to assess the behavior of estimates. Generally, we concluded that the Bayes estimates are preferable to the corresponding other estimates in approximately most of the situations. We proved empirically that the APITL model reveals its superiority over other competitive models for different real data.

Acknowledgement: Thank a lot for every one help full.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. A. Mahdavi and D. Kundu, “A new method of generating distribution with an application to exponential distribution,” Communication in Statistics–Theory & Methods, vol. 46, no. 13, pp. 6543–6557, 2018. [Google Scholar]

2. M. Nassar, A. Alzaatreh, M. Mead and O. Abo Kasem, “Alpha power Weibull distribution: Properties and applications,” Communications in Statistics – Theory & Methods, vol. 64, no. 20, pp. 10236–10252, 2017. [Google Scholar]

3. S. Dey, A. Alzaatreh, C. Zhang and D. Kumar, “A new extension of generalized exponential distribution with application to ozone data,” Ozone: Science & Engineering, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 273–285, 2017. [Google Scholar]

4. Hassan A. S., Mohamd R. E., Elgarhy M. and Fayomi A., “Alpha power transformed extended exponential distribution: Properties and applications,” Journal of Nonlinear Sciences and Applications, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 239–251, 2018. [Google Scholar]

5. S. Dey, I. Ghosh and D. Kumar, “Alpha power transformed Lindley distribution: Properties and associated inference with application to earthquake data,” Annals of Data Science, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 623–650, 2019. [Google Scholar]

6. A. S. Hassan, M. Elgarhy, R. E. Mohamd and S. Alrajhi, “On the alpha power transformed power Lindley distribution,” Journal of Probability and Statistics, vol. 2019, no. 13, pp. 1–13, 2019. [Google Scholar]

7. S. Dey, M. Nassar and D. Kumar, “Alpha power transformed inverse Lindley distribution: A distribution with an upside-down bathtub-shaped hazard function,” Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, vol. 385, no. 2, pp. 130–145, 2019. [Google Scholar]

8. A. S. Hassan, M. A. Khaleel and R. E. Mohamd, “An extension of exponentiated Lomax distribution with application to lifetime data,” Thailand Statistician, forthcoming, 2021. [Google Scholar]

9. R. A. ZeinEldin, M. S. Haq, S. Haq and M. Elsehety, “Alpha power transformed inverse Lomax distribution with different methods of estimation and applications,” Complexity, vol. 2020, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

10. V. K. Sharma, S. K. Singh, U. Singh and V. Agiwal, “The inverse Lindley distribution: A stress-strength reliability model with application to head and neck cancer data,” Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 162–173, 2015. [Google Scholar]

11. E. M. Almetwally, R. Alharbi, D. Alnagar and E. H. Hafez, “A new inverted Topp-Leone distribution: Applications to the COVID-19 mortality rate in two different countries,” Axioms, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 25, 2021. [Google Scholar]

12. M. Abd AL-Fattah, A. A. EL-Helbawy and G. R. AL-Dayian, “Inverted Kumaraswamy distribution: Properties and estimation,” Pakistan Journal of Statistics, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 37–61, 2017. [Google Scholar]

13. E. M. Almetwally, “Extended odd Weibull inverse Rayleigh distribution with application on carbon fibres,” Mathematical Sciences Letters, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 5–14, 2021. [Google Scholar]

14. K. V. P. Barco, J. Janeiro and V. Mazucheli, “The inverse power Lindley distribution,” Communication in Statistics - Simulation and Computation, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 6308–6323, 2017. [Google Scholar]

15. M. H. Tahir, G. M. Cordeiro, S. Ali, S. Dey and A. Manzoor, “The inverted Nadarajah-Haghighi distribution: Estimation methods and applications,” Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation, vol. 88, no. 14, pp. 2775–2798, 2018. [Google Scholar]

16. A. S. Hassan and M. Abd-Allah, “On the inverse power Lomax distribution,” Annals of Data Science, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 259–278, 2019. [Google Scholar]

17. A. S. Hassan and R. E. Mohamed, “Parameter estimation for inverted exponentiated Lomax distribution with right censored data,” Gazi University Journal of Science, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 1370–1386, 2019. [Google Scholar]

18. A. S. Hassan, M. Elgarhy and R. Ragab, “Statistical properties and estimation of inverted Topp-Leone distribution,” Journal of Statistics Applications & Probability, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 319–331, 2020. [Google Scholar]

19. A. M. Abd El-Raheem, E. M. Almetwally, M. S. Mohamed and E. H. Hafez, “Accelerated life tests for modified Kies exponential lifetime distribution: Binomial removal, transformers turn insulation application and numerical results,” AIMS Mathematics, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 5222–5255, 2021. [Google Scholar]

20. E. M. Almetwally, H. M. Almongy and A. Elsayed Mubarak, “Bayesian and maximum likelihood estimation for the Weibull generalized exponential distribution parameters using progressive censoring schemes,” Pakistan Journal of Statistics and Operation Research, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 853–868, 2018. [Google Scholar]

21. A. S. Hassan and A. N. Zaki, “Entropy Bayesian estimation for Lomax distribution based on record,” Thailand Statistician, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 96–115, 2021. [Google Scholar]

22. A. S. Hassan, M. Abd-Alla and H. F. Nagy, “Estimation of P(Y<X) using record values from the generalized inverted exponential distribution,” Pakistan Journal of of Statistics & Operation Research, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 645–660, 2018. [Google Scholar]

23. A. S. Hassan, M. Abd-Alla and H. F. Nagy, “Bayesian analysis of record statistics based on generalized inverted exponential model,” International Journal of Advanced Science Engineering and Information Technology, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 323–335, 2018. [Google Scholar]

24. T. Bjerkedal, “Acquisition of resistance in guinea pies infected with different doses of virulent tubercle bacilli,” American Journal of Hygiene, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 48–130, 1960. [Google Scholar]

25. A. S. Hassan, E. A. Elsherpieny and R. E. Mohamed, “Odds generalized exponential-power function distribution: Properties & applications,” Gazi University Journal of Science, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 351–370, 2019. [Google Scholar]

26. E. S. A. El-Sherpieny, E. M. Almetwally and H. Z. Muhammed, “Progressive type-II hybrid censored schemes based on maximum product spacing with application to power Lomax distribution,” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, vol. 553, no. 268, pp. 124251, 2020. [Google Scholar]

27. B. Jorjensen, “Statistical properties of the generalized inverse Gaussian distribution,” New York: Springer-Verlag, 1982, Lecture Notes in Statistics, 9, 2012. [Google Scholar]

28. M. V. Aarset, “How to identify a bathtub hazard rate,” IEEE Transactions on Reliability, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 106–108, 1987. [Google Scholar]

29. E. M. Almetwally, H. M. Almongy, M. K. Rastogi and M. Ibrahim, “Maximum product spacing estimation of Weibull distribution under adaptive Type-II progressive censoring schemes,” Annals of Data Science, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 257–279, 2020. [Google Scholar]

30. R. Alshenawy, M. A. Sabry, E. M. Almetwally and H. M. Almongy, “Product spacing of stress-strength under progressive hybrid censored for exponentiated-gumbel distribution,” Computers Materials & Continua, vol. 66, no. 3, pp. 2973–2995, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |