DOI:10.32604/iasc.2021.016381

| Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing DOI:10.32604/iasc.2021.016381 |  |

| Article |

Workflow Models to Establish Software Baselines in SSMEs

1Department of Computer Science, COMSATS University Islamabad, Wah, Pakistan

2Department of IT and Computer Science, PAF-lnstitute of Applied Sciences and Technology, Haripur, Pakistan

3College of Computer Science and Information Technology, Al Baha University, Al Baha, Saudi Arabia

4Department of Information Technology, Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, University of Jeddah, Jeddah, Suadi Arabia

5Department of Information and Computer Science, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran, 31261, Saudi Arabia

6Department of Information and Communication Engineering, Yeungnam University, Gyeongsan, 38541, Korea

*Correspondence: Muhammad Shafiq. Email: shafiq@ynu.ac.kr

Received: 31 December 2020; Accepted: 21 February 2021

Abstract: Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) is used for Software Process Improvement (SPI) worldwide. Research reveals that CMMI adoption needs a lot of resources in terms of training, funds, and professional workers. Software Small & Medium Enterprises (SSMEs) cannot, however, reserve resources for the purpose. One of the challenges of CMMI adoption is that CMMI identifies “What-to-Do” as a requirement to fulfill and leaves “How-To-Do” to implementers. Implementation of Configuration Management Process Area (CM-PA), being one of the umbrella activities, presents more obstacles generally to the software industry and particularly to SSMEs as compared to other PAs. Establish software baselines is the first Specific Goal (SG-1) needed by CMMI for the effective implementation of CM-PA. Workflow Models (WFMs), an identified set of activities performed in a logical sequence to accomplish a specific practice with probable actors and potential work products, were designed for implementation of its three contributing Specific Practices (SPs). The proposed WFMs were evaluated through the Expert Panel Review (EPR) process. Additionally, a case study was conducted to validate the proposed models. The results of the EPR/Case Study showed that the proposed WFMs are useful, easy to use, supportive in the achievement of SG-1, and applicable to SSMEs. It is important to mention that this research work adds to the empirical software engineering body of knowledge as well as contribute to the implementation of CM-PA.

Keywords: SPI; CMMI; CM-PA; SSMEs

There is no global definition of SSMEs. However, the software enterprises having employees from 6 ~ 250 are considered as SSMEs. The success or failure of SSMEs depends upon the quality of their products or services. Clients expect high-quality software that runs flawlessly and never crashes. One way to improve quality is to improve software development processes. Continual software process improvement and periodic appraisal for effectiveness are bound to pave the way towards high-quality software. It cannot be denied that the CMMI model helps the software industry to take the quality of its software development process to higher levels. However, no significant number of SSMEs decide to adopt it. Xu et al. [1] believe that CMMI offers software enterprises only guidelines and does not provide clear workflow models.

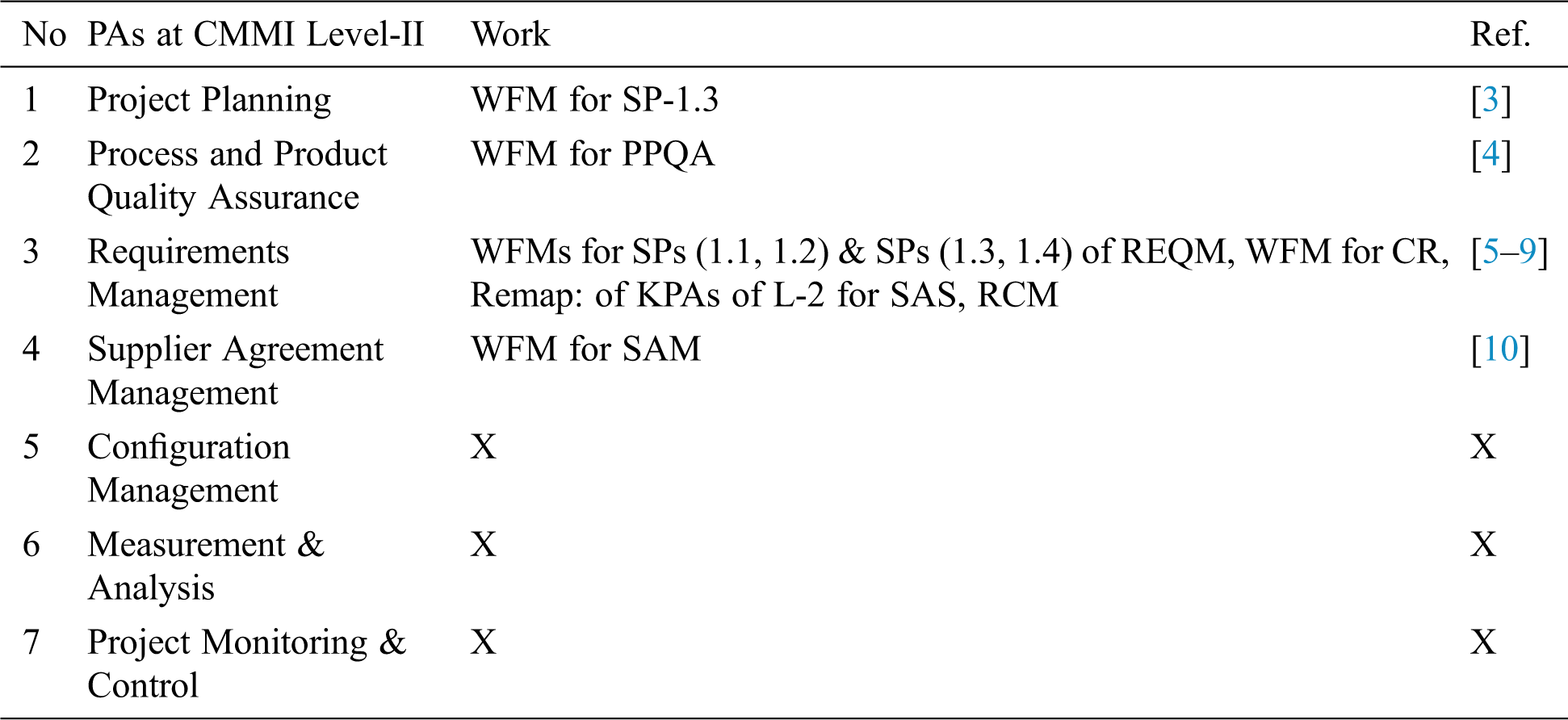

CMMI Level-II [2] comprises seven PAs, including CM-PA. A wide range of research has been carried out for the implementation of PAs at Level-II. However, no workflow model was found for establishing a baseline to help SSME, as shown in Tab. 1. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop configurable workflow models for this purpose.

Table 1: Summary of workflow models devised earlier for various SPs of PAs at CMMI Level-II

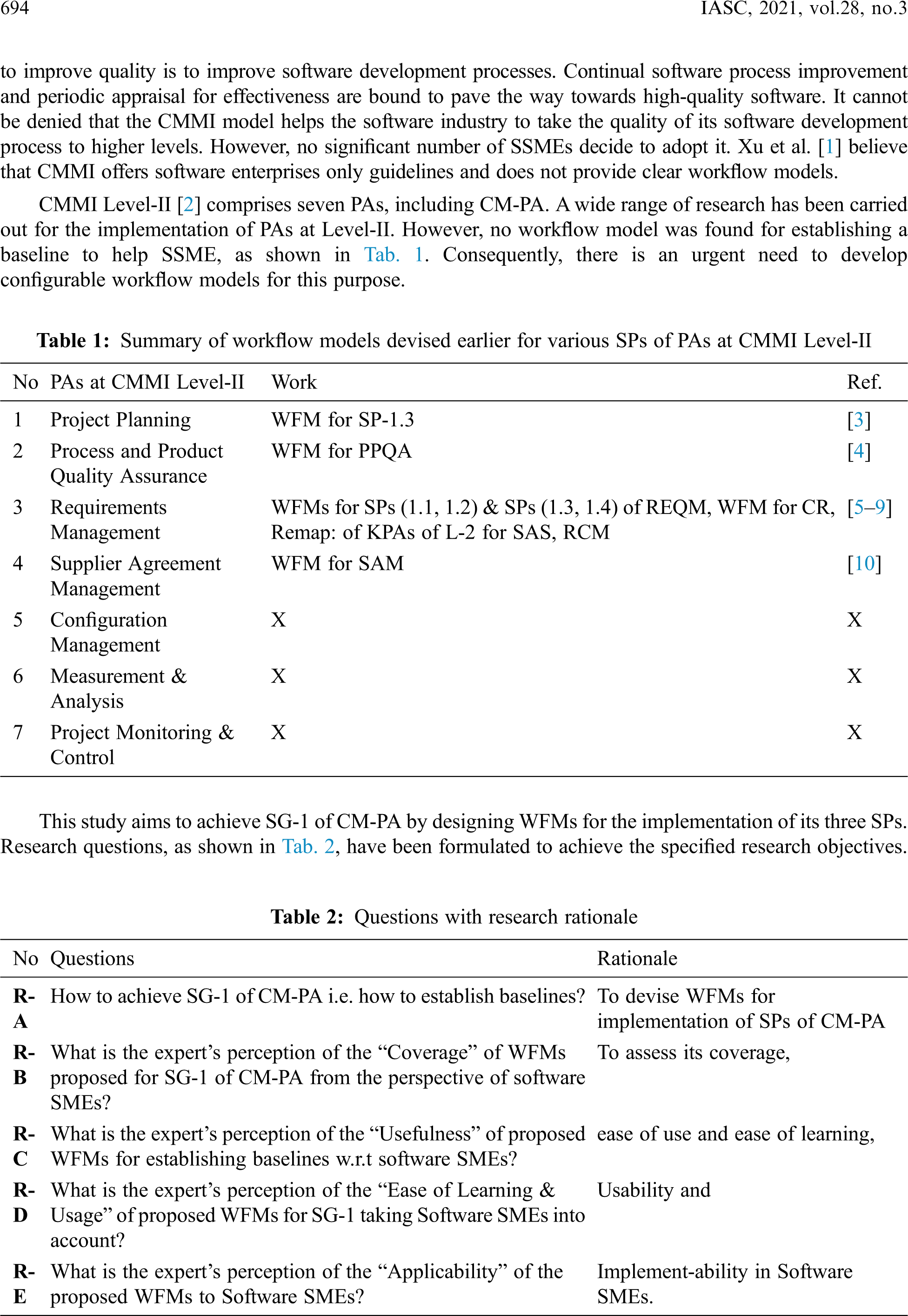

This study aims to achieve SG-1 of CM-PA by designing WFMs for the implementation of its three SPs. Research questions, as shown in Tab. 2, have been formulated to achieve the specified research objectives.

Table 2: Questions with research rationale

Research methodology has always been considered to have a profound impact on the study, so it was very meticulously designed. The phases involved in the designing of the WFMs are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Research methodology

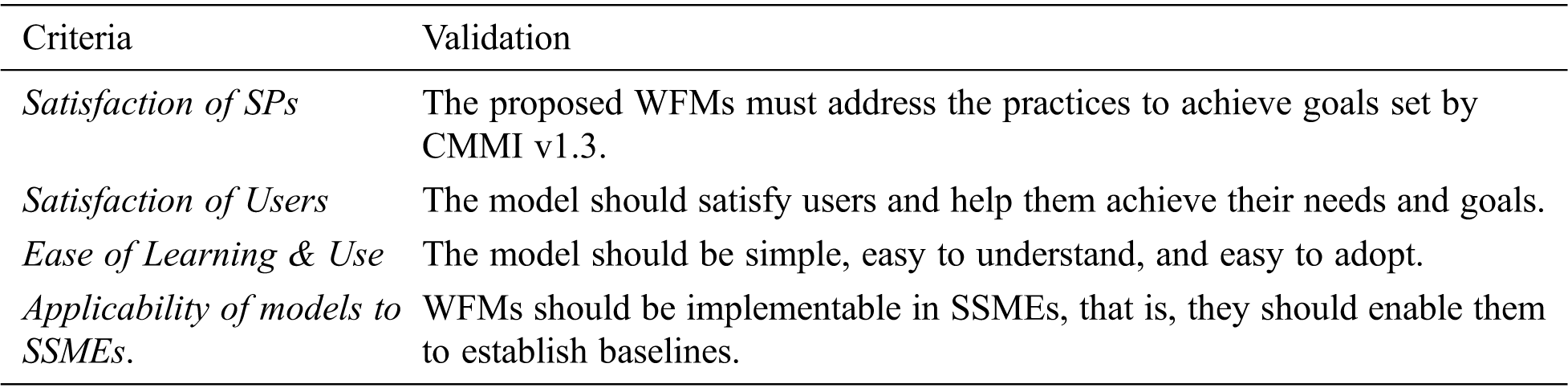

Identification of the criterion is the first phase of this research methodology. The criterion, because of its similar nature, was derived from the work of Keshta [3–6], and Niazi et al. [9] respectively, as briefed in Tab. 3. The rest of the phases, being self-explanatory, need not be further elaborated.

A variety of related research was explored. However, for brevity, only very close research, i.e., WFMs designed for implementation of PAs at CMMI Level-II is presented. Keshta [3] devised a WFM for implementation of SPs 1.3 of PP-PA and defined phases for a project life cycle keeping in view the SSMEs. The model comprises four stages: “Plan”, “Design”, “Review”, and “Update / Rework”. Keshta et al. [4] further developed WFMs for all SPs of PPQA-PA from the perspective of SSMEs. Two of the SPs, (SP - 1.1 and SP - 1.2) of PPQA comprise four stages i.e., “Plan”, “Prepare”, “Audit” & “Report”. The models were validated using EPR. Besides, Keshta et al. [5] designed WFMs for four SPs of REQM-PA to support SSMEs to implement the best practices. The five phases of the WFM for SP 1.1 are: “Request”, “Understand”, “Evaluate”, “Accept” and “Finalize”. SP 1.2 also include five stages: “Assess”, “Report”, “Negotiate”, “Record”, and “Commit”. The WFMs [6] for SP 1.3 has six stages: “Initiate”, “Validate”, “Implement”, “Verify”, “Update” and “Release” whereas WFM for SP 1.4 also constitutes six stages: “Request”, “Maintain”, “Validate”, “Allocate”, “Verify” and “Release”. The EPR process was used to validate the WFMs using the specified criteria. The applicability of models to SSMEs was evaluated in Saudi Arabian software industry.

Other researchers have also done similar work. Tariq et al. [7] proposed that an additional SP be included in REQM-PA for Software as a Services (SAAS) and carried out validation through a case study “Allwebid”. Similarly, Batti et al. [8] proposed a six-phase methodology to deal with changing requirements i.e., “Initiate”, “Receipt”, “Approve/Disapprove”, “Evaluate”, “Implement” and “Configure” with CCB to act as a central player and process owner. In the same manner, Niazi et al. [9] developed the CMMI-compliant Requirements Change Management (RCM) Model with five stages: “Request”, “Validate”, “Implement”, “Verify” & “Update” which was evaluated through the EPR process. Consequently, Vivatanavorasin et al. [10] proposed a three-layer WFM for SAM-PA containing “Contextual layer,” “Elaboration layer”, and “Description layer”. A tool was also developed for Supplier Agreement Management as a proof-of-concept prototype.

After a thorough literature review, it was found that no WFM is available. However, there is an acute need to design WFMs to support the implementation of SG-1 in SSMEs.

The first SG of CM-PA “Establish Baselines” is achieved through three SPs.

4.1 Identify Configuration Items

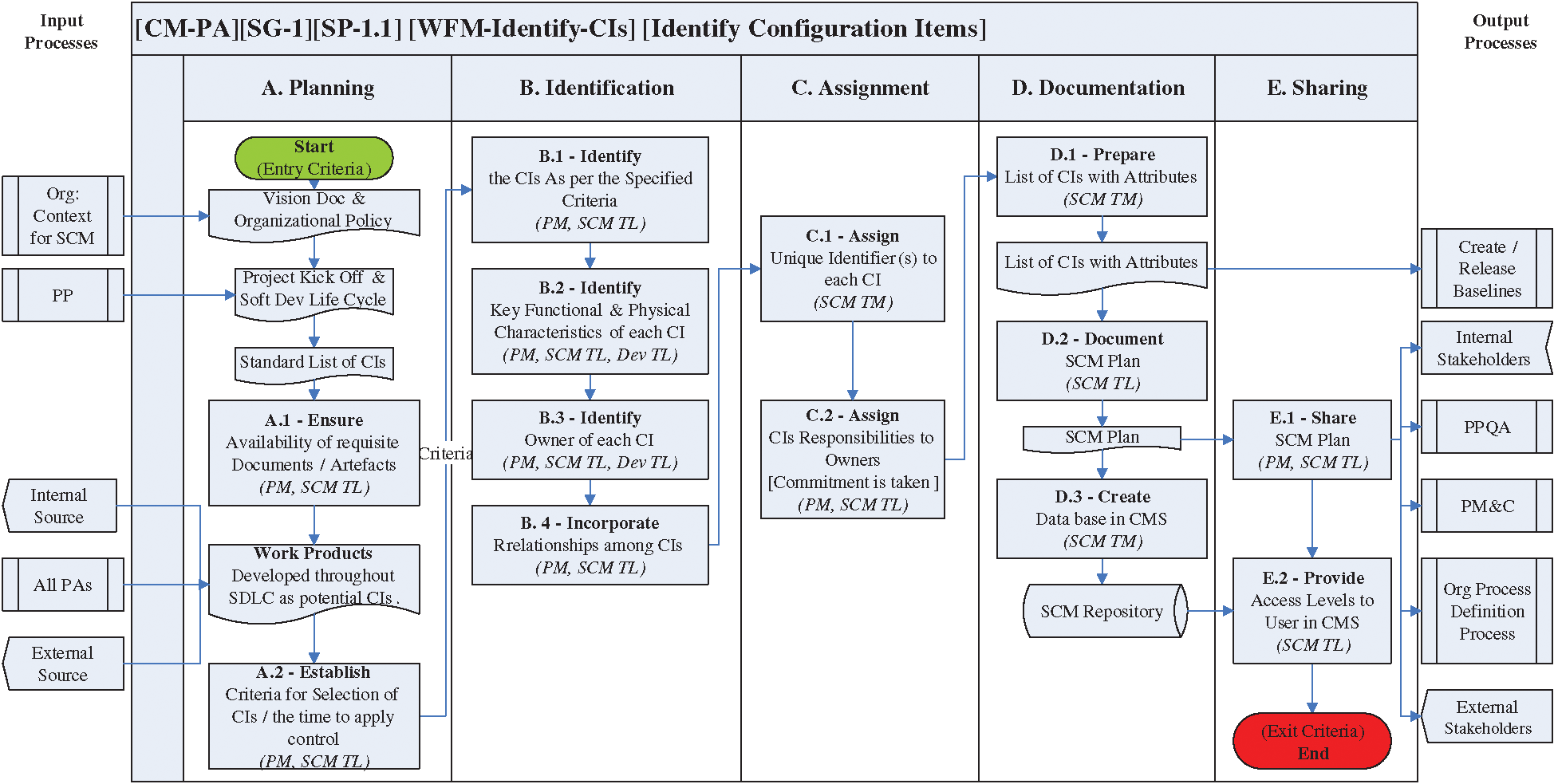

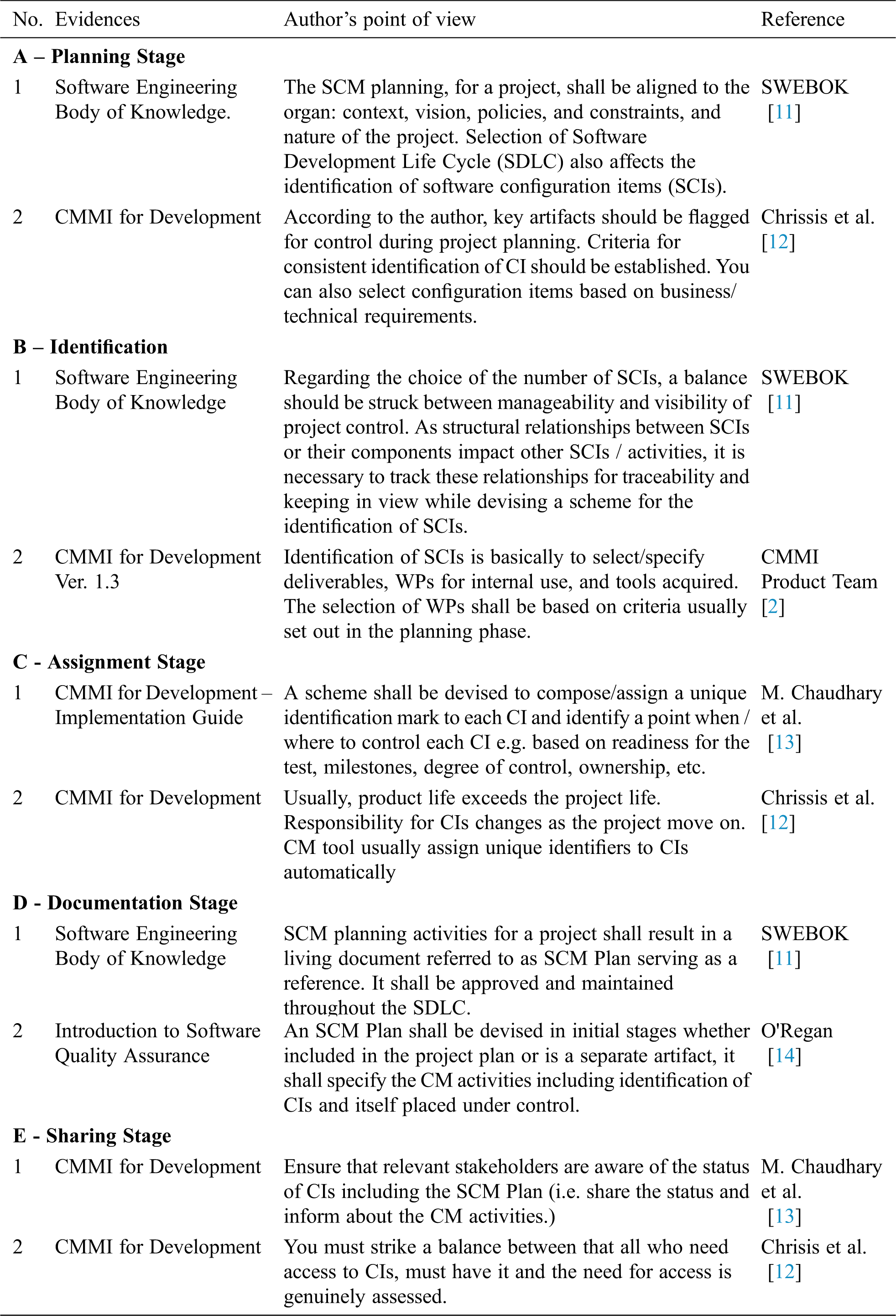

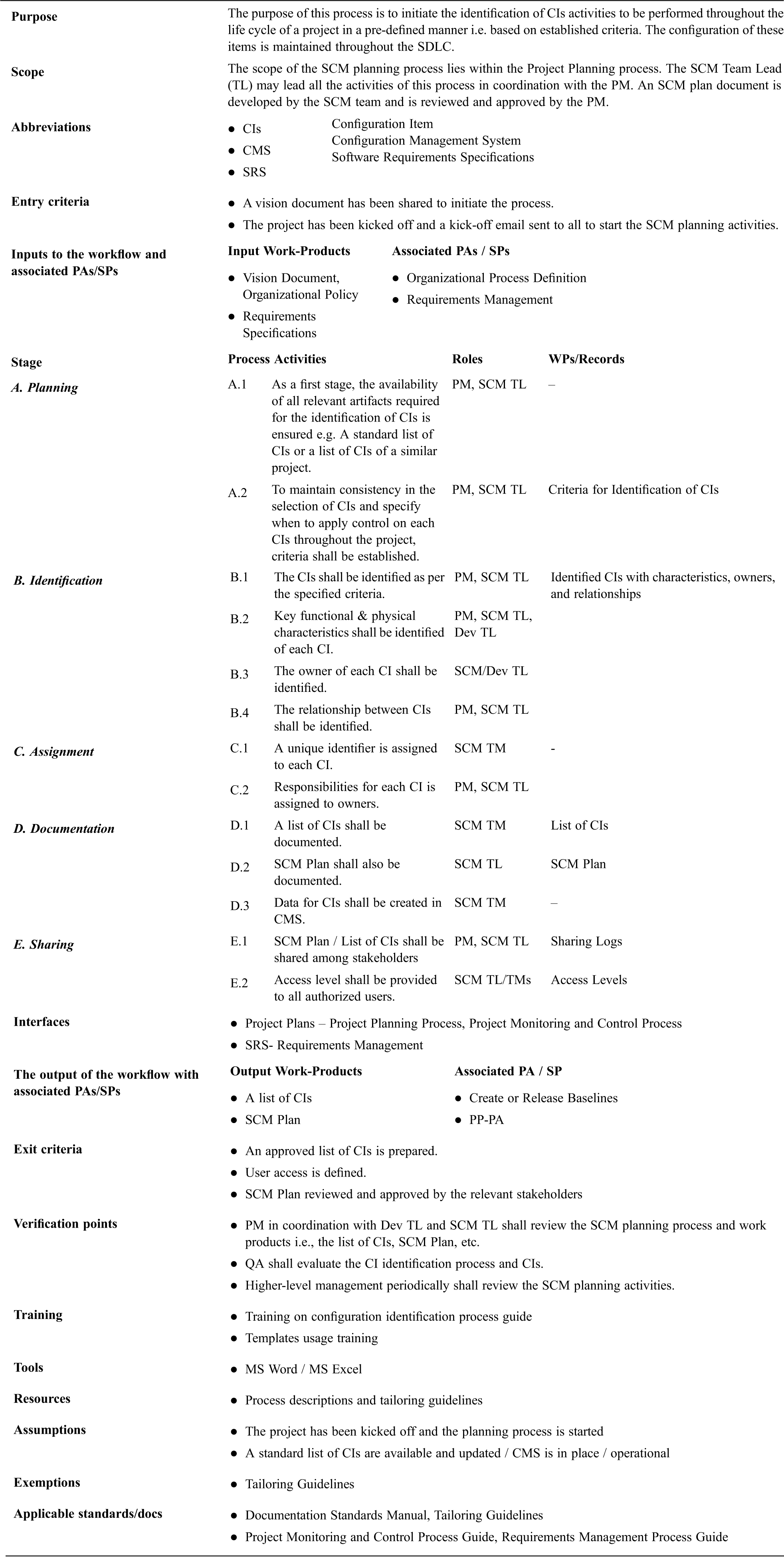

WFM for the first SP has five stages namely: “Planning”, “Identification”, “Assignment”, “Documentation” and “Sharing” as illustrated in Fig. 2. Supportive pieces of evidence are shown in Tab. 4 and a pertinent process guide is given in Tab. 5.

Figure 2: Proposed workflow model to identify configuration items (SP - 1.1)

Table 4: Evidences from the literature supporting the proposed WFM for identification of CIs

Table 5: A process guide for WFM to identify CIs

4.2 Establish Configuration Management System

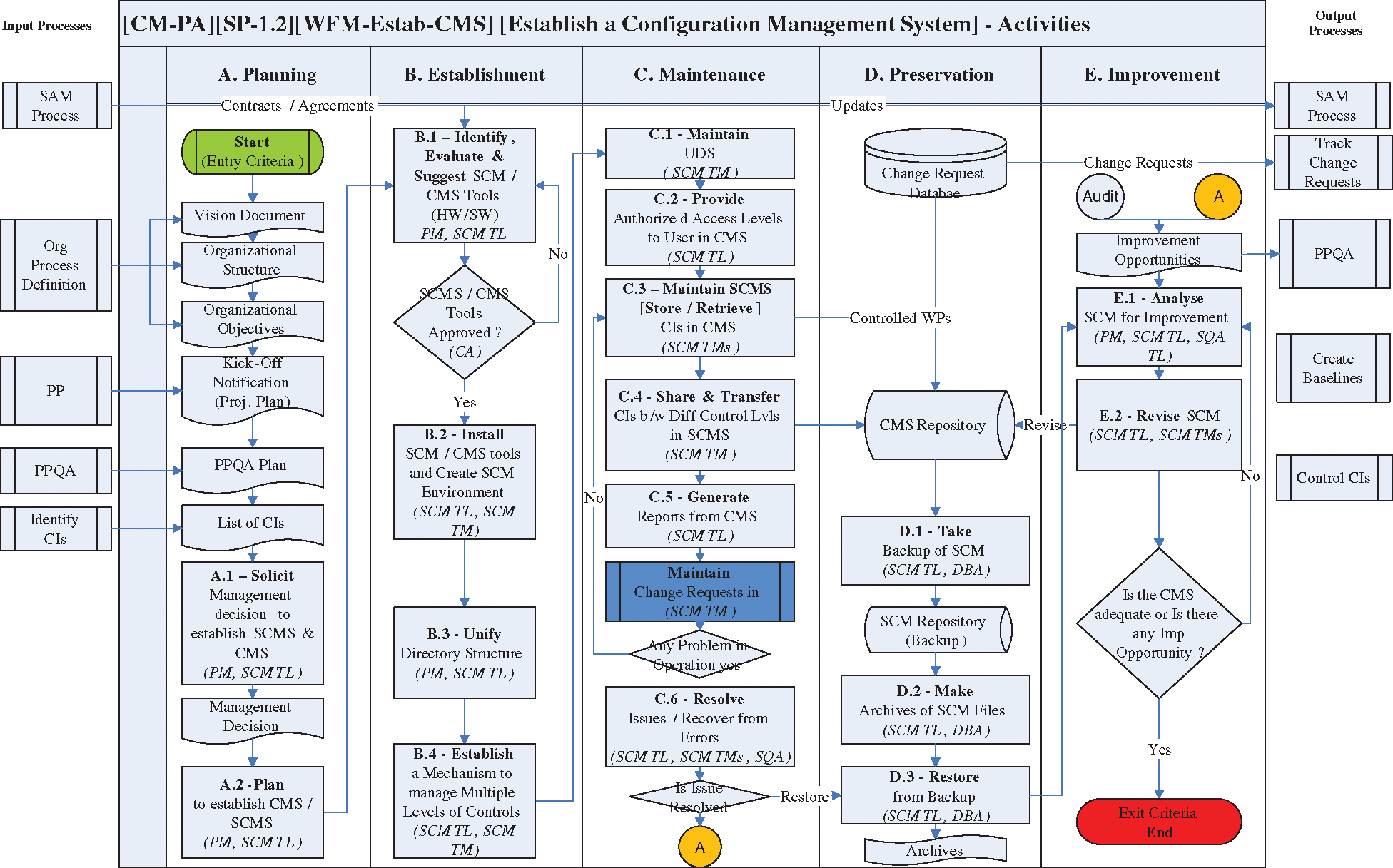

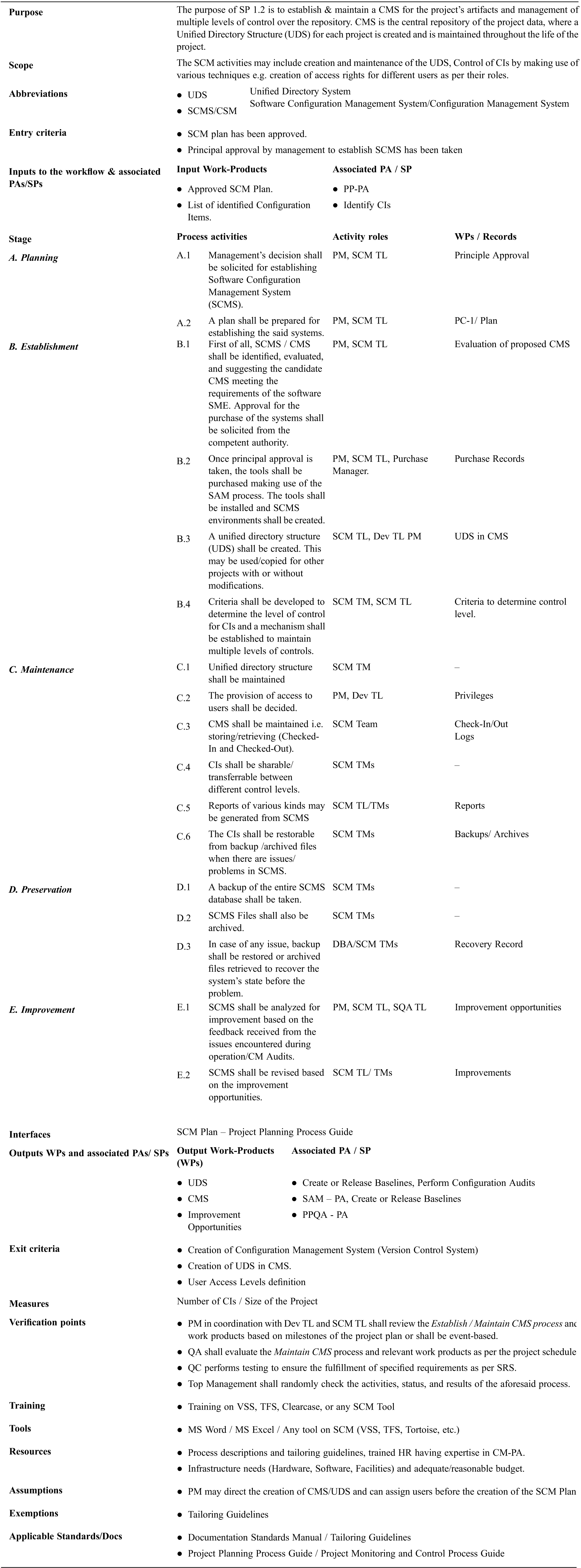

Few among the findings supportive of the proposed WFM are given in table Tab. 6. The proposed WFM is divided into five stages i.e., “Planning”, “Establishment”, “Maintenance”, “Preservation” and “Improvement” and is illustrated in Fig. 3 followed by the pertinent process guide in Tab. 7.

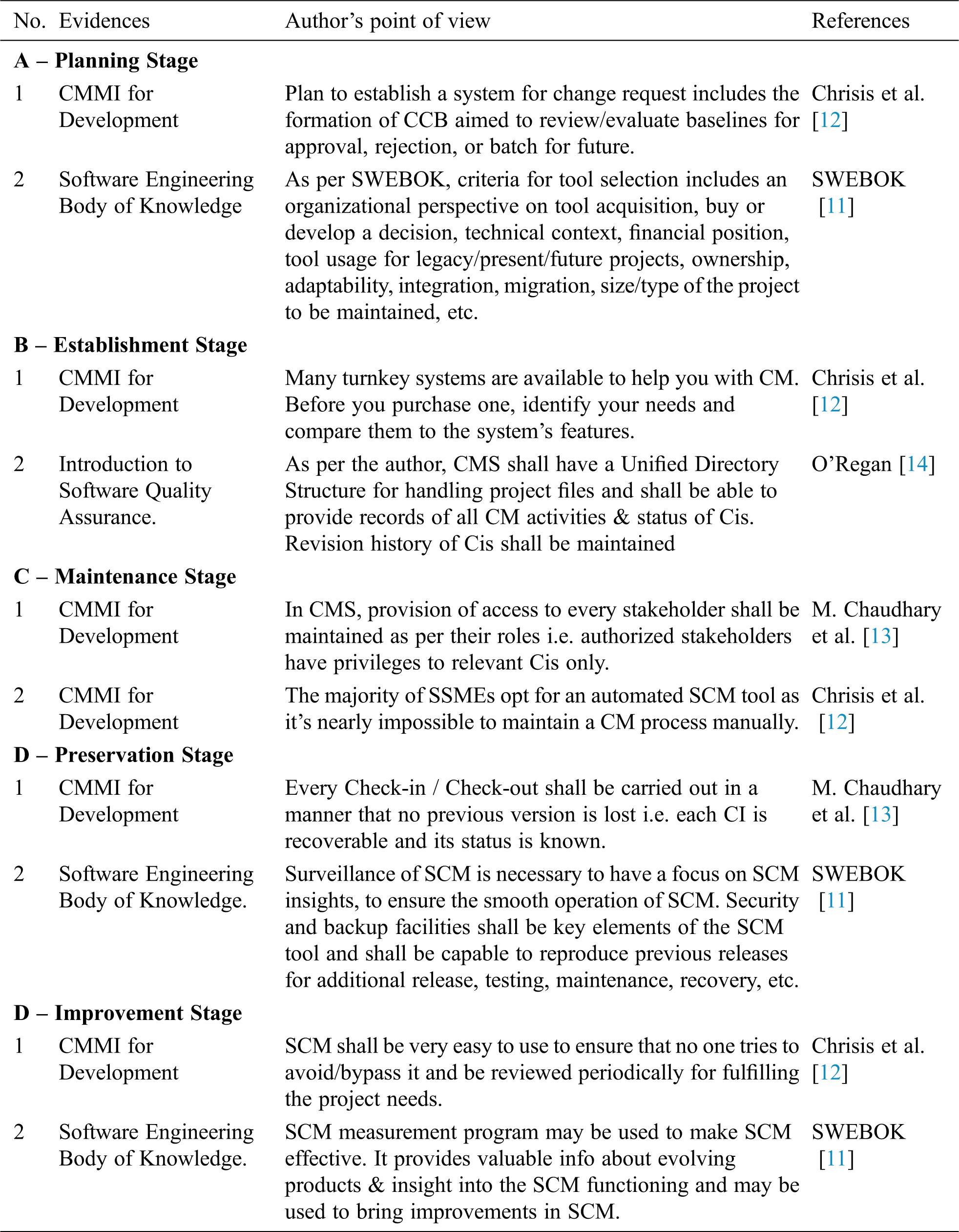

Table 6: Evidences from the literature supporting proposed WFM to establish CMS

Figure 3: Workflow model for SP - 1.2

Table 7: A process guide for establishing a configuration management system

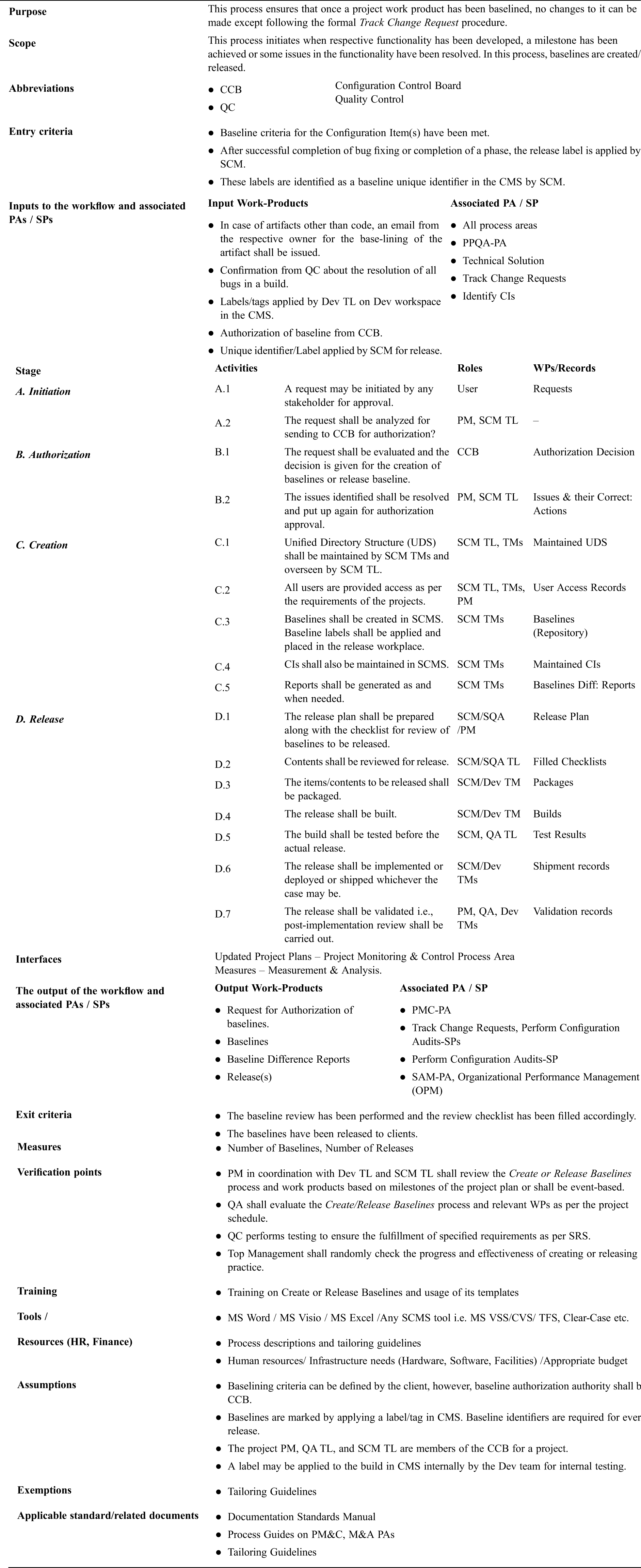

4.3 Create or Release Baselines

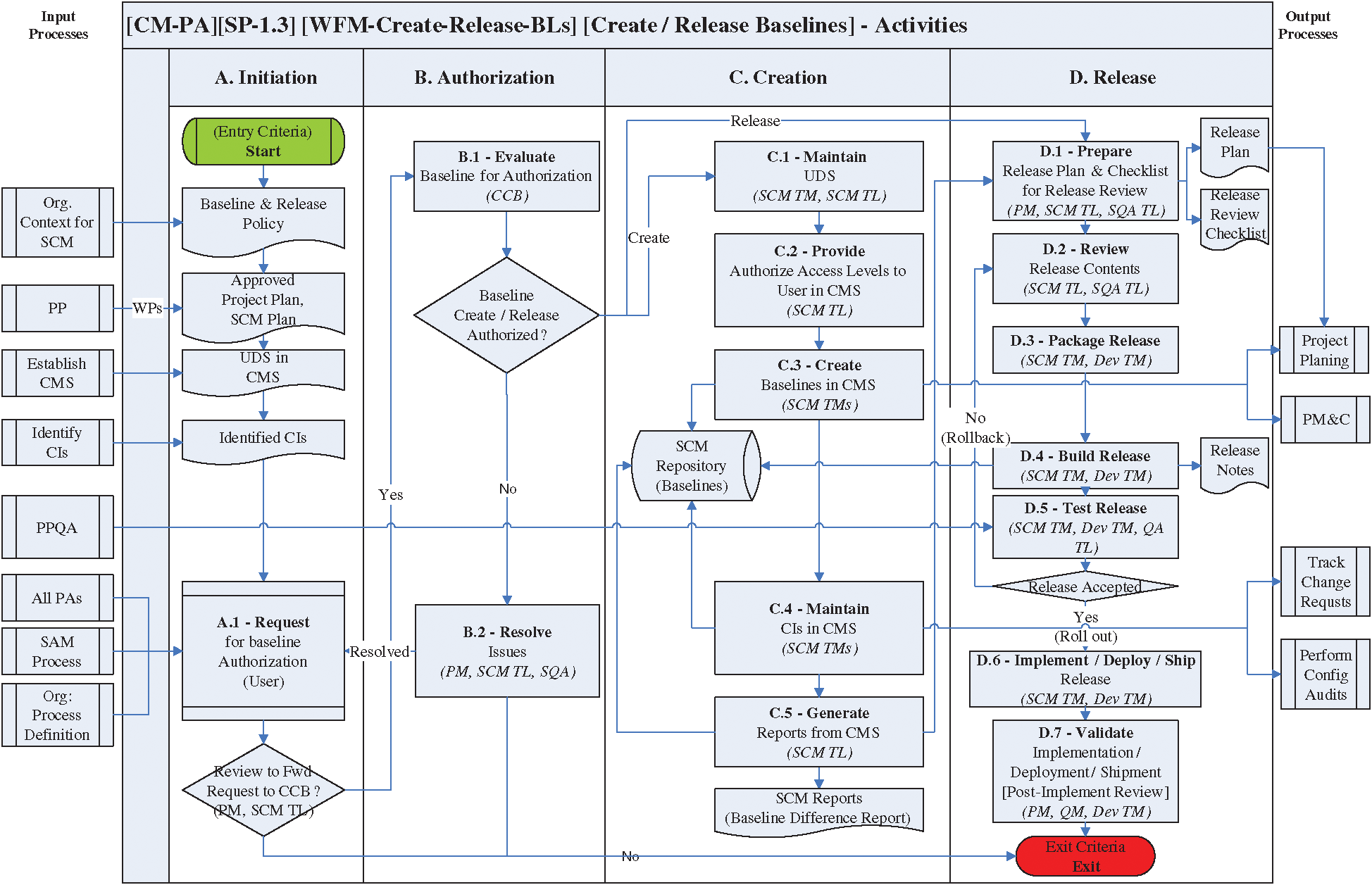

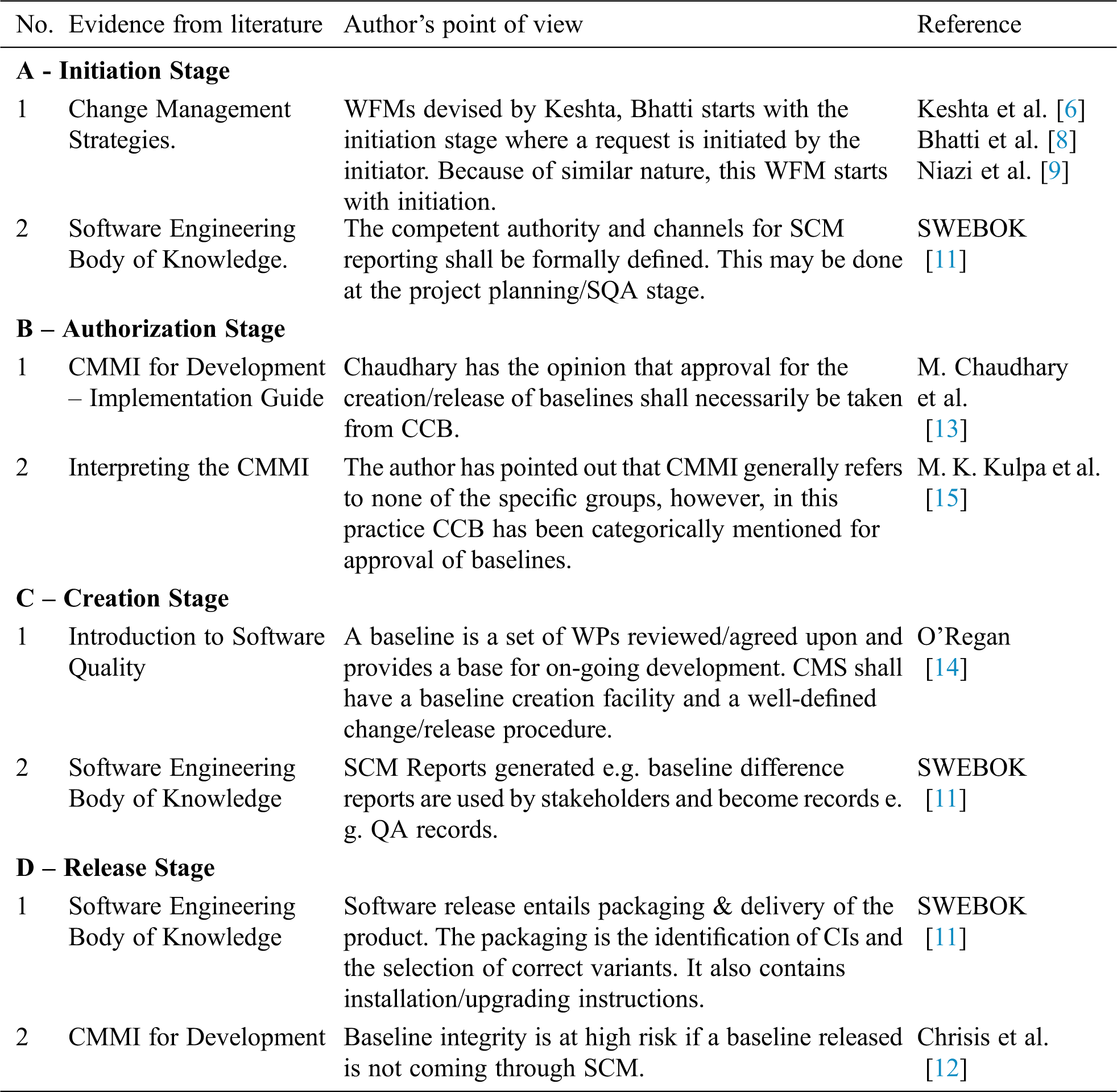

Proposed WFM for creating/releasing baselines is divided into four stages i.e., “Initiation”, “Authorization”, “Creation” and “Release” and is illustrated in Fig. 4. Only two of the supportive findings from literature are given in Tab. 8 and the pertinent process guide in Tab. 9.

Figure 4: Workflow model for SP - 1.3

Table 8: Pieces of evidence from the literature supporting WFM for creating or releasing baselines

Table 9: A process guide for creating/releasing baselines

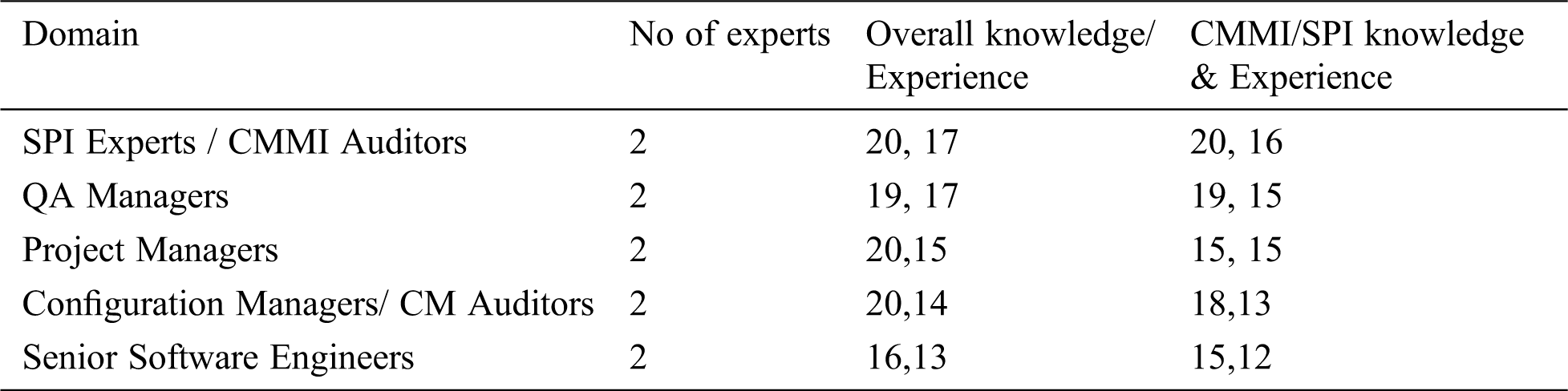

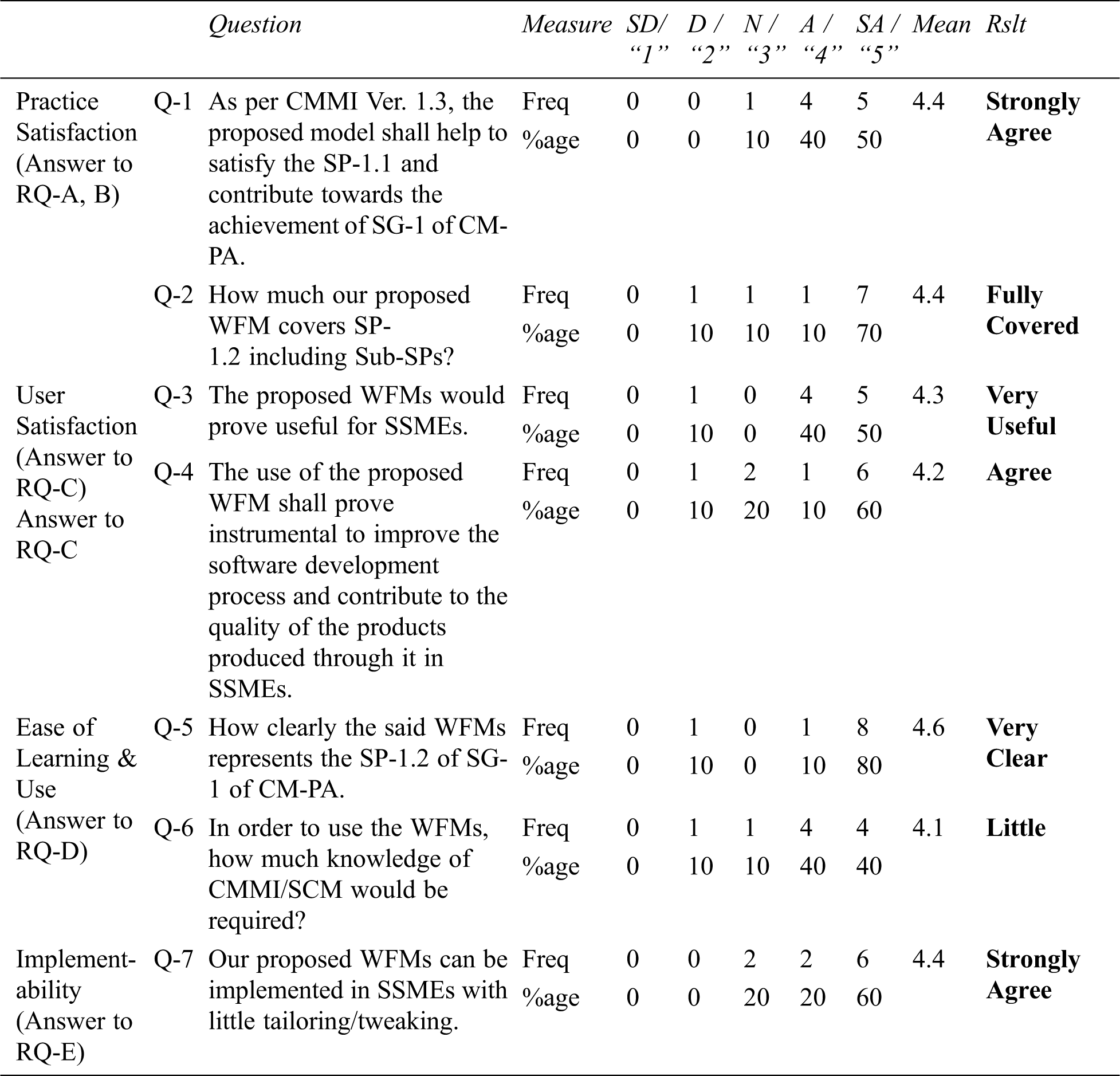

An EPR process was carried out to validate the proposed WFMs, where opinions on the models based on the specified criteria were collected from 10 experts with experience in the fields of SPI, Project Management, Configuration Management, and Software Development as shown in Tab. 10.

Table 10: Profiles of the panel members

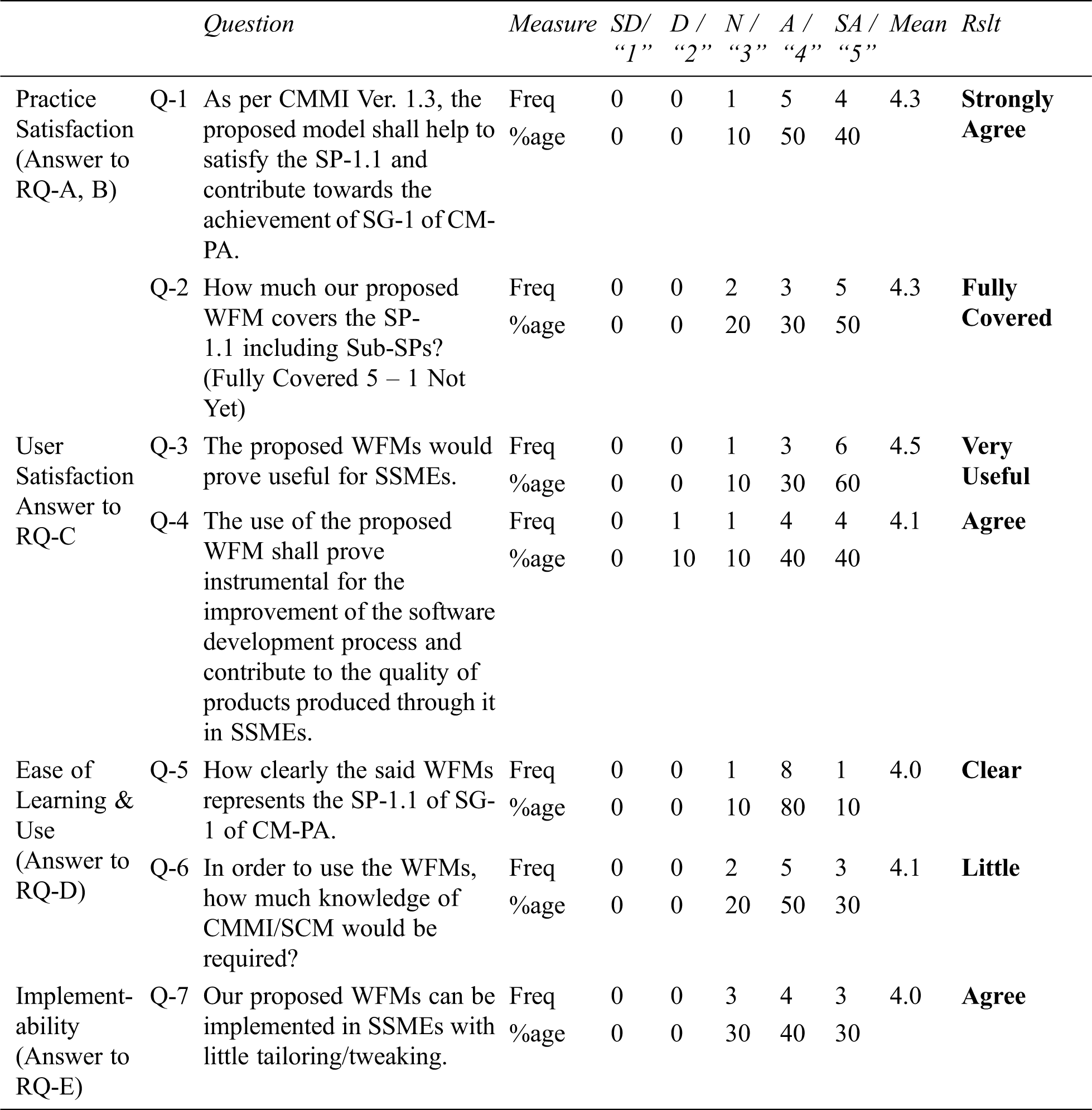

According to Khan et al. [16], researchers are free to establish their criteria. Experts were divided into 3 groups based on their experience/knowledge. Experts with less than 15 years of experience were classified as Junior, with more than 17 years of experience as Senior, and the rest were classified as Intermediate. According to this criterion, the panel consisted of 4 senior, 2 junior, and 4 intermediate experts. The questionnaire was formulated based on the work of Keshta [3–6], and Niazi et al. [9] specifically to obtain the panel's opinion on the proposed WFMs. A summary of the experts' responses based on the 5-point Likert scale is presented in Tabs. 11–13. The Q-8 was an open-ended question that was used to collect feedback to improve the models.

Table 11: Summary of the responses to the proposed WFM for identification of configuration items

Table 12: Summary of the responses to the proposed WFM for establishing a CMS

Table 13: Summary of responses to the proposed WFM for creating/releasing baselines

According to the ERP results, experts believe that the models are easy to learn, effective in implementing the SPs, supportive in achieving SG-1, cover the sub-practices, improve the process, are very useful for industry software, contribute to the quality of the software produced, and applicable in SSMEs. However, as with other things, there is room for improvement in the proposed WFMs.

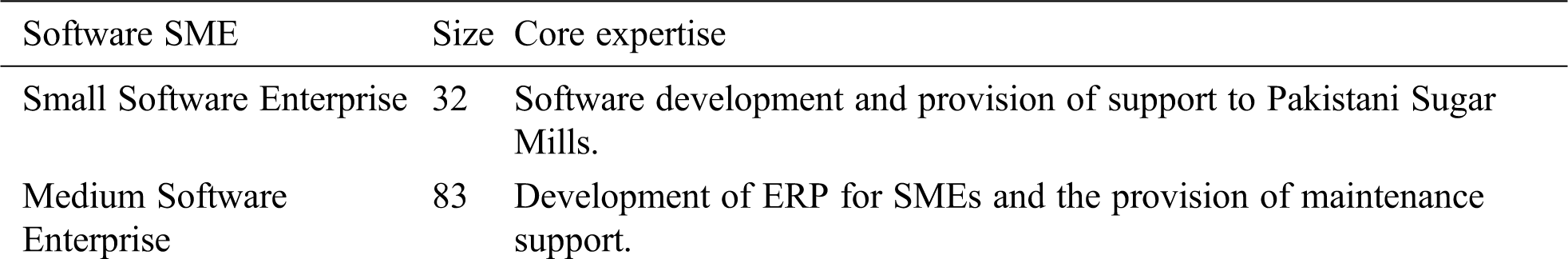

To build trust, a case study was conducted in two Pakistani SSMEs that were willing to implement the WFMs. For reasons of confidentiality, cover names are being used. Briefs of the SSMEs are tabulated in Tab. 14.

Table 14: Participant SMEs of the study

The above-mentioned SSMEs were assessed by a CMMI expert as a readiness review of the three SPs of CM-PA and were found not ready. Two SSMEs agreed to participate in these case studies. A brief presentation covering the objectives of the study was given at the opening session for both the SSMEs. To assess the effectiveness of the proposed WFMs after implementation, the lead auditor in both SMEs performed SCAMPI type “C” and type “B” assessments for these SPs. The result of the assessments was encouraging. All three SEs (SP 1.1, SP 1.2, and SP 1.3) were considered “Fully Implemented” and their contribution to the satisfactory achievement of the said SG-1, i.e., “Establish Baselines” in both SSMEs. According to the lead auditor's statement, both SSMEs will easily produce a "Fully Implemented" score in SCAMPI type “A”. Feedback from participating professionals was also collected in the closing session.

First, the closed-ended questions in the questionnaire may not have captured the true respondent’s feelings. An open-ended question was included to reduce the impact and capture the opinions freely. This added to the veracity of the response. Second, panel members may have interpreted the questions / WFM differently and answer accordingly. Due to the close connection, the questionnaire was taken from Keshta’s work [3–6]. This has been further refined by adding framework coverage at the sub-practice level and reviewed by another academician Third, the responses could be limited to the respondents' knowledge and experience. As part of building trust, experts with extensive industry experience participated in this research. The presence of world-renowned experts on the panel contributed to the effectiveness of the review process. Fourth, there may be a difference between the responses from Senior, Intermediate, and Junior experts. The P of Chi-Square (X2) test was found > 0.05 for ∞ = 0.05 and degree of freedom = 2 against the responses. It shows ignorable variation among the responses provided by the aforementioned three categories of experts. Fifth, the possibility that the usual literature review process may not have discerned relevant research work. As stated by Hossain et al. [17], this cannot be treated as a systemic omission. Finally, the results and conclusions may not be applicable in varied or typical environments. In addition to the EPR, case studies were conducted in the Pakistani SSME. Hence, the results can be generalized to the Pakistani SSME, however, more case studies should be carried out for external validity.

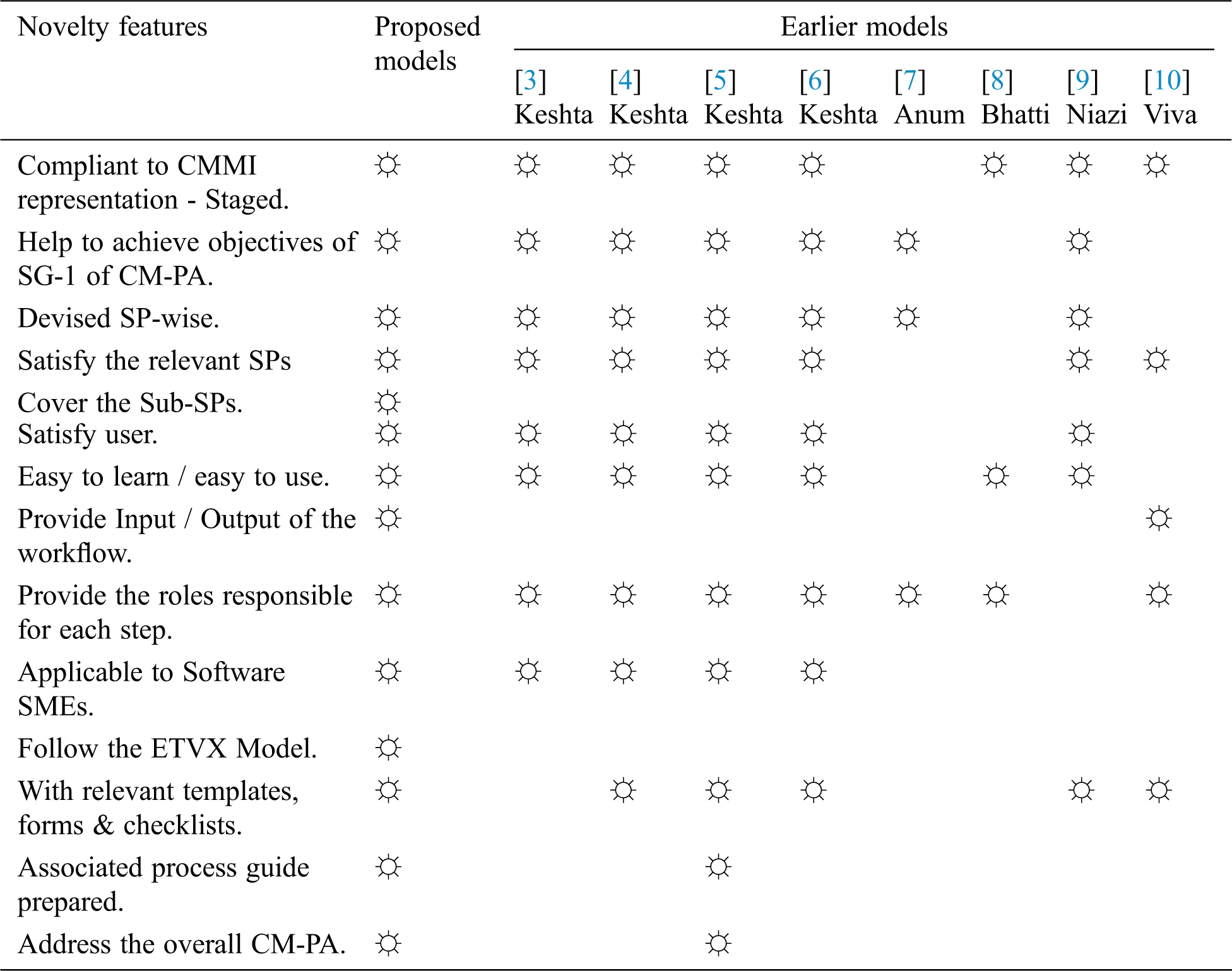

The novelty of the models is tabulated in Tab. 15 as under.

Table 15: The novelty of the WFMs in terms of features compared with earlier models for PAs

The development of a workflow model to achieve the SG-1 “Establish Baselines” of CM-PA at CMMI maturity level-II and its validation was the main objective of this study. For this purpose, five research questions (RQ-A ~ RQ-E) were formulated. Further WFMs were devised for all the three SPs contributing towards the establishment of baselines. The experts’ responses met the criteria listed. The results were further confirmed by conducting case studies. It is worth mentioning that the case studies have shown the ability of the Pakistani SSME to adopt the proposed models with slight changes to adapt to their contexts. Satisfactory comments from the participating organizations and experts speak well of WFMs and increase confidence in the evaluation results. During face-to-face discussions with participating professionals, it was found that they had no problem understanding / using models with related templates, forms, checklists, and process guides as supporting tools. WFM has been refined after several rounds of improvement taking into account the suggestions of scientists, specialists, and finally feedback from case study participants. This work should be continued to develop WFMs for other PAs for which the workflow models have still not been developed. Models should also be reviewed for external validity and future CMMI versions.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. G. Xu, H. Hu, P. Yu, J. Lv, P. Qu et al., “Supporting flexibility of the CMMI process framework with a multi-layered process model,” in Proc. Web Information System and Application Conf., Yangzhou, China, pp. 409–414, 2013. [Google Scholar]

2. CMMI Product Team, “CMMI for Development Version 1.3,”2010. [Google Scholar]

3. I. Keshta, “A model for defining project lifecycle phases: Implementation of CMMI level 2 specific practice,” Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 48, 2019. [Google Scholar]

4. I. Keshta, M. Niazi and M. Alshayeb, “Towards implementation of process and product quality assurance process area for Saudi Arabian small and medium-sized software development organizations,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 41643–41675, 2018. [Google Scholar]

5. I. Keshta, M. Niazi and M. Alshayeb, “Towards the implementation of requirements management specific practices (SP 1.1 and SP 1.2) for small- and medium-sized software development organisations,” IET Software, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 308–317, 2020. [Google Scholar]

6. I. Keshta, M. Niazi and M. Alshayeb, “Towards implementation of requirements management specific practices (SP1.3 and SP1.4) for Saudi Arabian small and medium-sized software development organizations,” IEEE Access, vol. 5, pp. 24162–24183, 2017. [Google Scholar]

7. A. Tariq, S. A. Khan and S. Iftikhar, “Remapping of CMMI level-2 KPA’s for development process improvement of software-as-a-service (SaaS) cloud environment,” in Proc. Int. Conf. on Open Source Systems and Technologies, Lahore, Pakistan: IEEE, pp. 43–51, 2014. [Google Scholar]

8. M. W. Bhatti, F. Hayat, N. Ehsan, A. Ishaque, S. Ahmed et al., “A methodology to manage the changing requirements of a software project,” in Proc. Int. Conf. on Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management Applications, Krakow, Poland: IEEE, pp. 319–322, 2010. [Google Scholar]

9. M. Niazi, C. Hickman, R. Ahmad and M. Ali Babar, “A model for requirements change management: implementation of CMMI level 2 specific practice,” in Lecture Notes Computer Science (including Subserial Lecture Notes Artificial Intelligence Lecture Notes Bioinformatics). Vol. 5089, Monte Porzio Catone, Italy: LNCS, pp.143–157,2008. [Google Scholar]

10. C. Vivatanavorasin, N. Prompoon and A. Surarerks, “A process model design and tool development for supplier agreement management of CMMI: capability level 2,” in Proc. XIII ASIA PACIFIC Software Engineering Conf., Bangalore, India: IEEE, pp. 385–392, 2006. [Google Scholar]

11. A. Abran, J. W. Moore, R. Dupuis, R. Dupuis and L. L. Tripp, “Software Configuration Management,” in Guide to the Software Engineering Body of Knowledge (SWEBOKVer 3.0. A Project of the IEEE Computer Society, vol. 6, pp. 1–15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

12. Mary Beth Chrissis, M. Konrad and S. Shrum, “Configuration Management,”in CMMI for development,3rd ed., Addison - Wesley, pp. 243–2552017. [Google Scholar]

13. M. Chaudhary and A. Chopra, “CMMI Design,” in CMMI for Development – Implementation Guide, India: Apress,2, pp. 9–69, 2017. [Google Scholar]

14. G. O’Regan, “Configuration Management,” in Introduction to Software Quality Assurance, Ireland: Springer Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London,5, pp. 89–99, 2014. [Google Scholar]

15. M. K. Kulpa and K. A. Johnson, “Understanding Maturity Level 2: Managed,” in Interpreting the CMMI - A process improvement approach, Boca Raton: Auerbach Publications,5, pp. 59–79, 2008. [Google Scholar]

16. S. U. Khan, M. Niazi and R. Ahmad, “Empirical investigation of success factors for offshore software development outsourcing vendors,” Institute of Engineering and Technology Software, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2012. [Google Scholar]

17. E. Hossain, M. Ali Babar and H. Y. Paik, “Using scrum in global software development: A systematic literature review,” in Proc. Fourth IEEE Int. Conf. on Global Software Engineering, Limerick, Ireland: IEEE, pp. 175–184, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |