DOI:10.32604/csse.2021.016506

| Computer Systems Science & Engineering DOI:10.32604/csse.2021.016506 |  |

| Article |

External Incentive Mechanism Research on Knowledge Cooperation-Sharing in the Chinese Creative Industry Cluster

1Sun Glorious School of Business, Donghua University, Shanghai, 200051, China

2Unviersity Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia

*Corresponding Author: Shiyu Liu. Email: Saber0471@163.com

Received: 04 January 2021; Accepted: 28 February 2021

Abstract: The creative industry is a knowledge-based industry, but it is difficult and complex to create knowledge for enterprises. The principle of cooperation-sharing posits that companies’ limited resources prohibit them from gaining a competitive advantage in all business areas. Therefore, cooperation-sharing can help businesses overcome this hurdle. Cooperation-sharing expedites economic development, breaks the barrier of independent knowledge creation, and enhances resource utilization. However, the effectiveness and stability of knowledge cooperation-sharing are key problems facing governments and other regulators. This study can help regulators promote honesty in enterprise cooperation-sharing. Based on the hypothesis of bounded rationality, the evolutionary game theory was used to construct the “Enterprises–Informal Institutions–Government” tripartite game matrix. Next, based on this game matrix, a simulation analysis method was used to analyze the effects of external incentives on the stability of evolutionary strategies. The analysis shows that the strategic choice of the “Enterprises–Informal Institutions–Government” tripartite game could be affected by the initial state strategy choices of the other two players, but more influential were the cost and external incentive levels of the game players. The results indicate that the government and informal institutions should regulate enterprises with a rational external incentive mechanism that boosts the enterprises’ incentive to cooperate honestly. Thus, an effective external incentive mechanism can significantly improve the probability of enterprises behaving honestly in cooperation-sharing and promote the development of the creative industry.

Keywords: Creative industry; knowledge sharing; evolutionary game; external incentives

China has experienced a difficult period of economic structural adjustment since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in 2019. The traditional industry is over-capacity, and the demographic dividends, which refer to the economic growth that results from the changing age of a country’s population, have decreased, making exportation difficult. As such, the prior development model is no longer applicable to the current Chinese economy. To break through the bottlenecks and constraints of the present economic development, the Chinese government has proposed some guidelines and policies. One of these policies involves the internal circular economy model [1] and the vigorous development of creative industries. The internal circular economy model encourages citizens to set up stalls, which helps them increase profits during a crisis such as the pandemic, as daily work is less available. Developing the creative industry is a signal that the Chinese government is trying to change the existing economic system into a high-knowledge economy. Knowledge is the most valuable strategic resource because it helps companies manufacture more products [2], enables the government to improve the market economy mechanism [3], and accelerates the development of the green economy by reducing pollution and strengthening sustainable development.

The creative industry has distinct characteristics. Its high integration and diversity of knowledge promote knowledge transfer to different fields [4], and restructure the knowledge system for companies and their products. In the early years of the creative industry’s growth, most people believed that the gathering of creative workers formed creative settlements, provided an effective platform for innovative products, and laid a foundation for further expansion [5]. With its evolution and continuous social development, the gathering of creative workers transformed into the gathering of creative enterprises, and gradually formed creative clusters [6,7]. Creative clusters are constructed under a professional organizational structure in a geographical space, thus helping creative enterprises enhance industrial cohesion and improve their ability to redistribute industrial resources [8]. The creative industry has gradually developed a network with knowledge as its core, the clusters as the carrier, and the enterprises as the nodes [9,10]. On this basis, knowledge transfer, sharing, and cooperation are the three main ways to boost the creative industries’ process and the creative economy’s development. With the increasing complexity and diversity of the economic society, enterprises must create new competitive advantages through innovation. Some researchers propose the use of non-cooperative games to optimize resource scheduling [11,12], gather all the resources, or reject cooperation to avoid the risk of losses. However, in the current situation, limited resources and high costs are barriers to enterprise innovation. Cooperation-sharing [13] has become a significant choice for enterprises to develop, innovate, and establish advantages. It can reduce innovation costs and technical requirements, lower the risk of independent innovation, and shorten the innovation cycle. Cooperation-sharing helps enterprises engage with markets and promotes resource integration and utilization in the whole value chain. Eventually, it enables enterprises to reach a higher level [14].

Cooperation-sharing is a win-win option to help enterprises overcome difficulties. However, it may lead to a leakage of core knowledge and cause enterprises to suffer more losses [15]. Thus, the choice of whether to conduct cooperation-sharing is of great significance to enterprises. Cooperation-sharing is a joint innovation mode [16] in which both sides of the cooperation represent the main body of innovation at the same time, take common interests as the goal, jointly conduct knowledge input, and bear costs and risks (as well as the innovation results). According to research by Zhou et al. [17] and Yang et al. [18], the distance between partners in different dimensions, such as the social status of potential partners, goodwill, compatibility with their enterprises, and differences in the working level between the two parties, directly affects cooperation-sharing behavior. Even the geographical and technical distances have different degrees of impact on cooperation-sharing. Diversified external incentives also have a crucial influence on cooperation-sharing, and the external subsidies can effectively improve the efficiency and enthusiasm of cooperation-sharing [19]. According to Wu’s research [20], the essence of cooperation-sharing innovation behavior is to accelerate the flow and transformation of knowledge. Different characteristics of knowledge have different influences on cooperation-sharing, such as the different characteristics of knowledge, the degree of trust, the heterogeneity of knowledge, and the cost of knowledge sharing [21]. Moreover, knowledge characteristics, degree of trust, knowledge heterogeneity, knowledge sharing cost, and other factors add to the difficulties of enterprises’ cooperation-sharing behavior. However, if the characteristics are fully designated, the cooperation process may be improved. For example, full sharing of explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge maximizes the innovation rate and quality of the enterprises. Similarly, the geographical location, cultural differences, religious beliefs, and other factors may lead to conflicts in cooperation-sharing behavior, which reduces the cooperation probability and the effectiveness of cooperation-sharing. Both sides of cooperation-sharing face the leakage or transfer of the shared knowledge to a third party [22,23]. If there is a relatively high degree of cooperation, the risk of knowledge loss or leakage will be higher when there is more shared knowledge, higher knowledge relevance, and a higher acceptance level of both sides.

In the current literature, we found detailed analyses and discussions on the objectives, influencing factors, corresponding risks, and incentives of enterprise knowledge cooperation-sharing. However, there has been little research on enterprise cooperation under dual supervision to date. We examined the enterprises in the creative industry cluster, the government, and informal institutions as players and established a tripartite cooperation game model with the duplication of supervision by the government and informal institutions. We then used the evolutionary game theory to analyze enterprises’ strategy about knowledge cooperation-sharing in the creative industry cluster. We then conducted a numerical simulation through MATLAB to explain enterprises’ behavior in the process of cooperation-sharing. This study provides guidance to creative enterprises for facilitating cooperation and to the government and informal institutions for regulating enterprises during cooperation-sharing.

According to the assumption of bounded rationality in the evolutionary game, bounded rational agents cannot accurately predict their payoff function and make the most effective strategy choice. Thus, decision-makers need to simulate and learn the revenue strategy through repeated experiments and then find an effective and stable equilibrium state to support their decision-making. By analyzing the decision-making equilibrium of each participant to set up a payment function, we can get the corresponding copy dynamics and draw a conclusion. The creative industry cluster has sociality. When enterprises start to cooperate and share knowledge, they are social participants with bounded rationality. In the creative industry, the policies issued by the government serve as formal constraints. Also, some informal institutions, such as industry associations, chambers of commerce, and industrial alliances, provide regulatory and supervisory functions other than formal constraints for the operation of creative industry clusters and enterprise exchanges and cooperation. We label such constraints implicit contracts [24].

Hypothesis 1: When enterprises cooperate and share knowledge, there are benefits to the enterprises and government. When informal institutions can provide effective implicit contracts, informal institutions can also derive some economic benefits. Suppose

Hypothesis 2: In the evolutionary game system, the decision-making of each participant may come with different costs. When the government decides to regulate the cluster, it needs some cost;

Hypothesis 3: Incentive mechanism. If the informal institutions can ensure that the implicit contract is implemented effectively in the market, the government will reward the informal institutions with certain benefits. Suppose the reward is

Hypothesis 4: Suppose that the collaboration coefficient of cooperation-sharing among enterprises in the cluster is

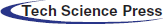

According to the above hypothesis, from the government’s perspective, when the government regulates the creative industry cluster, and the government pays the corresponding control cost and obtains certain economic benefits. It provides a cost subsidy to the enterprises that maintain the integrity of the knowledge cooperation-sharing behavior and fines the enterprises that fail to maintain honesty in the cooperation. When informal institutions effectively supervise the enterprises in the cluster, ensure the smooth implementation of the implicit contract, and pay a supervision cost, the informal institution gains certain benefits from the government. If the informal institutions do not supervise and guarantee the implicit contract implementation, the informal institutions will not pay any costs or get any benefits. If the enterprises are honest in knowledge cooperation-sharing, they will obtain benefits and get the cost subsidies. However, if the enterprise cannot be honest, or betray others in the process of knowledge cooperation-sharing, the cost of knowledge cooperation-sharing will be reduced, but it will pay a fine to the government regulator and the informal institution supervisor.

3 Model Establishment and Analysis

According to the above hypothesis, the behavior probability of the present parties in the game is as follows: cluster enterprises: honest-(

Table 1: Tripartite game matrix of enterprises, informal organizations, and governments in creative industry clusters. *I stands for the Informal Institution Supervision

By analyzing the assumption and combing the matrix, we could obtain the payoff function of each player in different situations, as well as the corresponding strategy probability and the strategy set of each function, as shown in Tab. 2.

Table 2: Three-party game payment function and strategy set of enterprises, informal organizations, and governments in creative industry clusters

3.1 The Government’s Expected Return Function, Evolution Strategy, and Stability Analysis in the Three-party Game

Assuming that

Assuming that

Assuming that

According to the replication dynamic equation of the evolutionary game, the government’s replication dynamic equation could be obtained:

If

Figure 1: Dynamic evolution of the government’s regulation strategy

In Fig. 1, the shadowy area divides the whole space into two parts: the upper part of the space, A1, and the lower part, A2. When the initial strategic state of the government was in space A1, the government’s regulation on the enterprises and the informal institution in the creative cluster was invalid because when

3.2 The Expected Return Function, Evolution Strategy, and Stability Analysis of Informal Institutions in Tripartite Game

Suppose that

Suppose

Suppose

According to the replication dynamic equation of evolutionary game, the replication dynamic equation of informal institutions could be obtained:

If

Figure 2: Dynamic evolution of the informal institutions’ regulation strategy

In Fig. 2, the shadowy area divides the whole space into two parts: the left part, B1, and the right part, B2. When the initial strategic state of the informal institutions was in space B1, the information institutions’ regulation on the enterprises in the creative cluster was effective, and when

3.3 The Enterprises’ Expected Return Function, Evolution Strategy, and Stability Analysis in the Three-party Game

Suppose

Suppose

Suppose

According to the replication dynamic equation of evolutionary game, the enterprises’ replication dynamic equation could be obtained:

When

If

In Fig. 3, the shadowy area divides the whole space into two parts: the upper part, C1, and the lower part, C2. If the initial strategy of enterprises was stated in the space C1,

Figure 3: Dynamic evolution of the enterprises’ strategy

By deducting the replicator dynamics function of each player, we could get the following equations:

By analyzing the three equations, we found out that the evolution of the dynamic strategy was related to the cost of different players, the reward, and the punishments from the supervisors.

Hypothesis 5: According to the parameters required in the replication dynamics, based on bounded rationality and consultation with experts, we made assumptions about the required parameters:

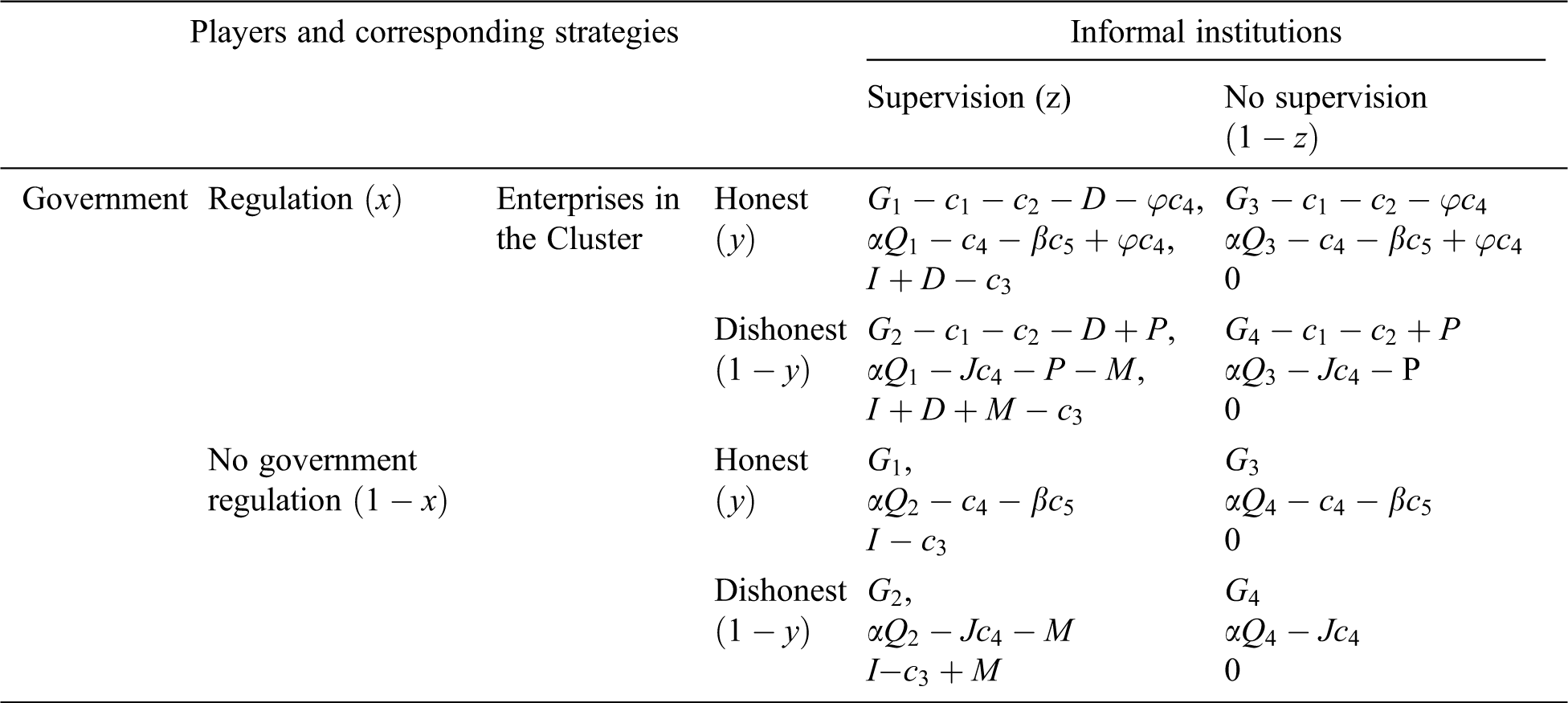

Figure 4: Simulation of the dynamic strategy evolution of enterprises, informal institutions, and governments (1)

The government’s replication dynamic equation is composed of the cost and subsidy, so the government showed a change in strategy that tended to be unregulated. When the government was unwilling to supervise, the informal institutions did not derive benefit

Hypothesis 6: Based on bounded rationality and consultation with experts, the required parameters are assumed. Assume

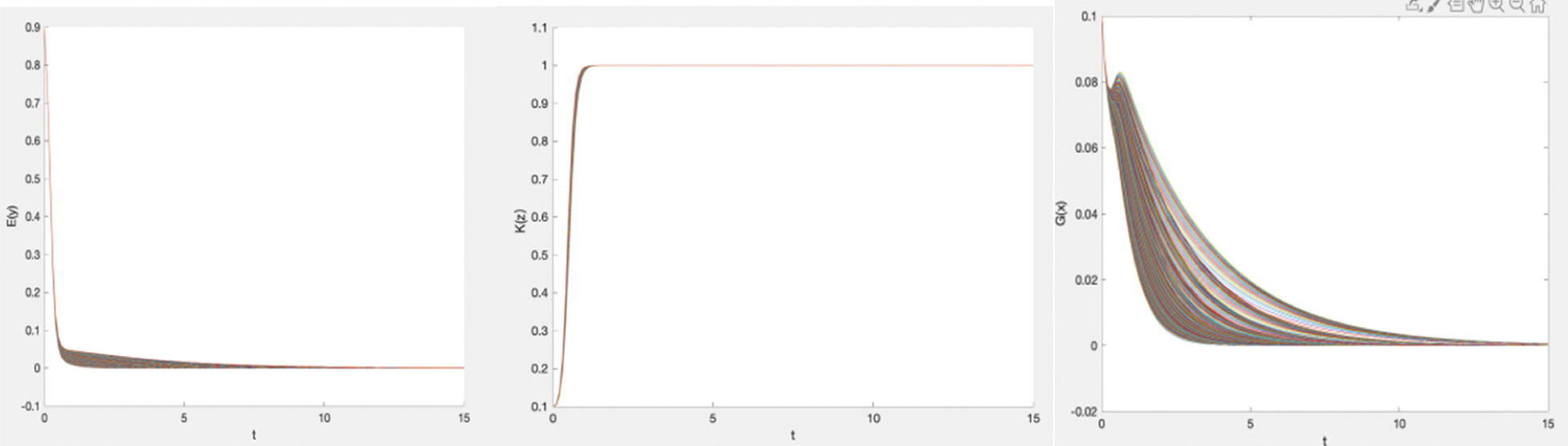

Figure 5: Simulation of the dynamic strategy evolution of enterprises, informal institutions, and governments (2)

The government’s replicator dynamics function is composed of the cost and subsidy, so the government showed a change in strategy that tended to be unregulated. However, because of the high penalty amount, the enterprises could not reduce the cost and improve the profit through the dishonest cooperation-sharing behavior. Thus, the enterprise tended to cooperate honestly. As the enterprises could not fully be honest in the cooperation, the higher penalty amount made the informal institutions profitable. At the beginning stage, informal institutions wanted to obtain fines from dishonest enterprises, which improved benefits. Therefore, during a period at the beginning of the simulation, informal institutions had a process that was inclined toward supervision. However, in the later stage, enterprises were honest in cooperation-sharing, so informal institutions gradually opted not to supervise. Therefore, with the same cost level of cooperation-sharing, a higher level of external incentives could help enterprises in the cluster to cooperate and share honestly.

Hypothesis 7: Based on bounded rationality and consultation with experts, some required parameters are assumed. Suppose that

Figure 6: Simulation of dynamic strategy evolution of enterprises, informal institutions, and governments (3)

Wihtin Hypothesis 7, the cooperating cost and knowledge leakage cost were related more closely than in Hypothesis 6. From the government’s perspective, the cost control issue led the government not to regulate. Moreover, the high operating cost made it difficult for enterprises to continue being honest in cooperation-sharing. In the face of high operating costs, enterprises can save many costs if they are dishonest. As such, although the punishment level was high, compared with the high cost that could be saved by being dishonest, enterprises preferred to be dishonest or betray the cooperation-sharing. Due to the high costs, the enterprises always chose to be dishonest in the cooperation-sharing, so the informal institutions spared no effort to supervise enterprises and obtain fines from them to improve income. In the case of excessive cost, if the external incentive failed to cover the loss caused by the cost, even if facing the problem of penalty, the enterprises still chose the dishonest cooperation-sharing behavior to save costs for themselves.

Hypothesis 8: Suppose that

Figure 7: Simulation of the dynamic strategy evolution of enterprises, informal institutions, and governments (4)

Under these assumptions, enterprises still faced high costs. Due to the supervision of the informal institutions and government regulation, enterprises faced high fines at the initial stage. Therefore, at the initial stage, enterprises had an increased probability of integrity cooperation. As time passed, enterprises found that the governments’ control decreased; enterprises could not obtain effective cost subsidies from the government. Even if they had to face the fines from informal institutions, the high cost they faced on their own may have been higher than the fine, so enterprises tended not to be honest during the knowledge sharing and cooperation in the later period. As the enterprises were dishonest in the cooperation-sharing, the informal institutions maintained a high level of supervision to improve benefits by fining the enterprises. If the informal institutions took their interests as the goal, they did not need to adjust their strategy. If the informal institutions wanted to promote the enterprises’ honesty in cooperation-sharing, increasing the punishment level is the best way.

Hypothesis 9: Based on the parameter assignment of Hypothesis 7, the initial strategy probability of the three parties in the game was adjusted, and we observed the dynamic strategy evolution of the three parties in the game. We assumed that

Figure 8: Simulation of the dynamic strategy evolution of enterprises, informal institutions, and governments (5)

As Fig. 8 shows, when the government and the informal institutions were unwilling to supervise and control in the early stage, the enterprises tended to be dishonest more quickly in cooperation-sharing. At the beginning of the game, the government and informal institutions showed their unwillingness to supervise, and the enterprises did not have the concern of high fines. Therefore, enterprises chose to be dishonest during the cooperation-sharing from the beginning. As the enterprises were dishonest, the government and informal institutions could increase their interest through fines. Therefore, both the informal institutions and the government chose to supervise and control the enterprises and then collect corresponding fines to increase benefits. Although the enterprises had a high probability of being honest during the cooperation, we observed that the government and informal institutions had a low probability of regulation and supervision. So, enterprises would tend not to be honest during the cooperation. As the level of dishonesty of the enterprises rose, both the government and the informal institutions hoped to restrain the occurrence of this phenomenon or seek profit for themselves in this way. Thus, the supervision probability of the informal institution quickly tended to be willing to supervise the enterprise. In the early stage, the government also hoped to be like the informal institutions to regulate effectively, but owing to the excessive level of subsidies, the government finally gave up the regulation.

Through analysis and research on the tripartite game among the government, enterprises, and informal institutions, we drew the following conclusions. The level of enterprises being honest in cooperation-sharing was affected by the external incentive, which refers to fines imposed by the government and informal institutions. Both the government and the informal institutions could encourage enterprises to be honest in cooperation-sharing. However, the government and informal institutions must consider more about the external incentive level. If the enterprises’ income from being dishonest in the cooperation-sharing is greater than the punishment, the enterprise continued to be dishonest in the cooperation-sharing while knowing that they would be punished. In such a situation, the external incentive mechanism was useless. If, however, the income level of dishonesty was lower than the punishment, enterprises preferred to be honest during the cooperation-sharing. The cost level of enterprises in the creative industry cluster had a decisive impact on whether they cooperated honestly.

The cost level also directly determined the level of the external incentive. The government and informal institutions should not make the external incentive level optional but decide after analyzing the enterprises’ income and cost level. A good credit market is conducive to the development of the industry and economy. However, if the government and the informal institutions still implement a higher level of external incentives to intervene in the case of higher enterprises’ cooperating costs, the enterprises may find themselves in a dilemma. Therefore, the enterprises’ cost level is at the core of the government and informal institutions when formulating a rational external incentive mechanism. Our study showed that the initial strategy state had no significant impact on the game. There was no great influence on the final steady states of the evolutionary game when the parameters were left unchanged, but they did adjust the initial probability of different strategies. No matter how much the initial state was, the game system approached the stable state when the cost and the external incentive level were in a relatively stable characteristic range. When the probability of government regulation was approaching zero, whether the enterprises chose to be honest during cooperation-sharing was more influenced by the informal institutions. The core influence was mainly related to the cooperating costs and the intensity of incentive and punishment from the informal institutions. Whether an enterprise chose to be honest during cooperation-sharing was also determined by the cooperating costs level and the relative level of external incentives. The external incentives had some impact on whether the enterprises were honest in cooperation-sharing. However, the enterprises’ cooperating cost level was the main factor affecting honesty in cooperation-sharing. Therefore, the rational external incentive should be based on the enterprise cost, and it should urge enterprises to be honest in cooperation-sharing. Ignoring the enterprises’ cost level and making the external incentive level optional could make cooperation-sharing more disorderly.

Funding Statement: General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (71874027).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the present study.

1. P. Su and Z. Li, “Matching mechanism of Chinese investment to domestic demand under the internal economic cycle,” On Economic Problems, no. 01, pp. 47–56, 2021. [Google Scholar]

2. C. Wu, V. Lee and M. E. McMurtrey, “Knowledge composition and its influence on new product development performance in the big data environment,” Computers, Materials & Continua, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 365–378, 2019. [Google Scholar]

3. C. Wu, H. Yin, X. Yang, Z. Lu and M. E. McMurtrey, “Pricing method for big data knowledge based on a two-part tariff pricing scheme,” Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1173–1184, 2020. [Google Scholar]

4. H. Zhou, T. Shen, X. L. Liu, Y. R. Zhang, P. Guo et al., “Knowledge graph: A survey of approaches and applications knowledge graph,” Journal on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 89–101, 2020. [Google Scholar]

5. T. A. Hutton, “Reconstructed production landscapes in the postmodern city: Applied design and creative services in the metropolitan core,” Urban Geography, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 285–317, 2013. [Google Scholar]

6. J. Howkins, The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas. London: The Penguin Press, 24–65, 2001. [Google Scholar]

7. J. Hartley, Creative Industries. U.S: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 24–33, 2005. [Google Scholar]

8. J. Zhang, “A research on the impact of Multi-proximity of entrepreneurial firms on synergetic innovation relationship,” Science Research Management, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 78–85, 2018. [Google Scholar]

9. Y. Wang and C. Yu, “Network structure and innovation knowledge flow in the cultural and creative industries cluster—based on the perspective of social network analysis,” Science and Technology, vol. 37, no. 11, pp. 158–163, 2017. [Google Scholar]

10. F. Wang and Y. Song, “Study on tacit knowledge sharing and shift in creativity industry clustering network,” Soft Science, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 4–9, 2013. [Google Scholar]

11. Y. Jiang, Q. Liu, W. Dannah, D. Jin, X. Liu et al., “An optimized resource scheduling strategy for hadoop speculative execution based on non-cooperative game schemes,” Computers, Materials & Continua, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 713–729, 2020. [Google Scholar]

12. C. Duan, J. Feng, H. Chang, J. Pan, L. Duan et al., “Research on sensor network coverage enhancement based on non-cooperative games,” Computers, Materials & Continua, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 989–1002, 2019. [Google Scholar]

13. L. Wang and M. Pan, “Research on manufacturing enterprises knowledge sharing strategy of cooperative innovation,” Science& Technology Progress and Policy, vol. 37, no. 10, pp. 128–135, 2020. [Google Scholar]

14. A. Wu, Z. Wang and S. Chen, “Impact of specific investments, governance mechanisms and behaviors on the performance of cooperative innovation projects,” International Journal of Project Management, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 504–515, 2017. [Google Scholar]

15. P. Ritala, H. Olander, S. Michaliloa and K. Husted, “Knowledge sharing, knowledge leaking and relative innovation performance: An empirical study,” Technovation, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 22–31, 2015. [Google Scholar]

16. Z. Wu and L. Zhao, “Cooperative Innovation or Iindependent Iinnovation? ——an expanded AJ model and It's used in the internet industry of China,” Economic Management, vol. 33, no. 12, pp. 141–149, 2011. [Google Scholar]

17. Q. Zhou, W. Du and W. Han, “Technological standard alliance in China: Partner selection and innovation performance,” Journal of Science and Technology Policy in China, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 196–209, 2012. [Google Scholar]

18. B. Yang, Y. Wang and X. Li, “The impact of multidimensional proximity on cooperative innovation,” Studies in Science of Science, vol. 1, pp. 154–164, 2019. [Google Scholar]

19. Y. Pan and S. Ni, “Opportunities and challenges of Sino——German science and technology innovation cooperation in the context of the Belt and Road Initiative,” Scientific Management Research, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 116–119, 2018. [Google Scholar]

20. J. Wu, X. X. Peng, Y. X. Sheng, L. Peng, Q. F. Shi et al., “Research on knowledge transfer cooperative Game in university-Industry cooperation based on dynamic control model,” Chinese Journal of Management Science, vol. 25, no. 30, pp. 190–196, 2018. [Google Scholar]

21. S. Shang and Z. Zhang, “The knowledge sharing of virtual enterprise based on evolutionary game,” China Soft Science, vol. 93, pp. 150–157, 2015. [Google Scholar]

22. K. Tan, P. Wong and L. Chung, “Information and knowledge leakage in supply chain,” Information Systems Frontiers, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 621–638, 2016. [Google Scholar]

23. J. Xu, J. Fu and F. Li, “Research on the service innovation diffusion of manufacturing enterprises based on evolutionary game theory,” Operation Research and Management Science, vol. 27, no. 7, pp. 177–183, 2018. [Google Scholar]

24. M. Gürtler and O. Gürtler, “The interaction of explicit and implicit contracts: A signaling approach,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 108–146, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |