Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Artificial Intelligence Revolutionising the Automotive Sector: A Comprehensive Review of Current Insights, Challenges, and Future Scope

1 Faculty of Mechanical and Automotive Engineering Technology, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah, Pekan, 26600, Malaysia

2 Institute for Intelligent Systems Research and Innovation (ISSRI), Deakin University, Warun Ponds, VIC, 3216, Australia

3 Automotive Engineering Centre, Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah, Pekan, 26600, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Md Mustafizur Rahman. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Current Perspectives and Alternative Paths: From eXplainable AI to Generative AI and Data Visualization Technologies)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2025, 82(3), 3643-3692. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.061749

Received 02 December 2024; Accepted 06 February 2025; Issue published 06 March 2025

Abstract

The automotive sector is crucial in modern society, facilitating essential transportation needs across personal, commercial, and logistical domains while significantly contributing to national economic development and employment generation. The transformative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionised multiple facets of the automotive industry, encompassing intelligent manufacturing processes, diagnostic systems, control mechanisms, supply chain operations, customer service platforms, and traffic management solutions. While extensive research exists on the above aspects of AI applications in automotive contexts, there is a compelling need to synthesise this knowledge comprehensively to guide and inspire future research. This review introduces a novel taxonomic framework that provides a holistic perspective on AI integration into the automotive sector, focusing on next-generation AI methods and their critical implementation aspects. Additionally, the proposed conceptual framework for real-time condition monitoring of electric vehicle subsystems delivers actionable maintenance recommendations to stakeholders, addressing a critical gap in the field. The review highlights that AI has significantly expedited the development of autonomous vehicles regarding navigation, decision-making, and safety features through the use of advanced algorithms and deep learning structures. Furthermore, it identifies advanced driver assistance systems, vehicle health monitoring, and predictive maintenance as the most impactful AI applications, transforming operational safety and maintenance efficiency in modern automotive technologies. The work is beneficial to understanding the various use cases of AI in the different automotive domains, where AI maintains a state-of-the-art for sector-specific applications, providing a strong foundation for meeting Industry 4.0 needs and encouraging AI use among more nascent industry segments. The current work is intended to consolidate previous works while shedding some light on future research directions in promoting further growth of AI-based innovations in the scope of automotive applications.Keywords

In the fourth industrial revolution era, artificial intelligence (AI) significantly impacts the world in resolving hitherto intractable issues from different sectors. AI mimics human behaviour like planning, reasoning, learning, problem-solving, thinking, perception, and decision-making in machines. This cognitive capability is achieved through human intelligence simulation utilising data with feasible algorithms [1,2]. As a result, AI can simplify complex tasks to minimise errors more efficiently, whereas humans are more prone to errors and require more time to complete the same tasks. Therefore, AI adoption in different sectors is increasing dramatically [3], i.e., the automotive sector [4], healthcare sector [5], power sector [6], real estate sector [7], entertainment and gaming sector [8], fast-moving consumer goods sector [9], education sector [10], e-commerce and retail shop sector [11], agriculture sector [12], cybersecurity [13], finance and banking sector [14], and so forth. Since the number of AI-adopted sectors is rising with time, its market is also expanding. VTT Technical Research Centre discusses these matters in their technical paper. They found that the AI market price in 2019 was $39.9 billion, and market analysts predict that this will increase to $733.7 billion in 2027 [15].

Moreover, based on this evidence, it is clear that AI’s significance in different sectors is rising due to its massive beneficial prospects and the outstanding growth of related research activities. Similarly, its importance is also visible in the automotive industry in minimising issues that arise and maximising outcomes intelligently. For example, intelligent fault diagnosis systems [16], intelligent manufacturing processes [17], intelligent control systems [18], intelligent supply chains, sales and service systems [19], intelligent traffic management systems [20], etc. Adopting AI for the abovementioned purposes makes the automotive sector more intelligent and sophisticated. Curiosity about AI is expanding in the automotive domain because it holds the key to the new future. It can extract essential information without the direct intervention of humans and utilise these to run any operation/activity smoothly to gain desired outcomes efficiently besides minimum losses in the automotive sector. As a result, the AI deployment rate in this sector for various purposes is also praiseworthy [21]. According to the report of Precedence Research, the worldwide automotive AI market generated revenue of $3.22 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow from $3.87 billion in 2024 to $35.71 billion by 2033. This remarkable expansion represents a compound annual growth rate of 28% over the nine-year forecast period [22]. Enhancing it in this sector will accelerate economic growth worldwide and improve desired functionalities. However, nuTonomy, AutoX, Optimus Ride, Drive.ai, Waymo, Zoox, CarVi, Nauto, Rethink Robotics, DataRPM, and many other organisations have been using AI technology in the last few years to shape the business context of the automotive sector and move it ahead [3].

Furthermore, the AI technology in this sector acts as a machine-enabled intelligent system that can perceive, learn, analyse, and comprehend the outcomes by following human cognition activity. To ensure the facility of this technology, it usually comprises algorithms with an arrangement of instructions loaded in a machine-like computer, which transforms input data into meaningful output [23]. In this instance, traditionally, it is not confined to machine learning (ML) algorithms used in the automotive sector as AI to expedite the desired work without complexity [24]. Artificial neural networks (ANN), deep learning (DL), reinforcement learning (RL), fuzzy logic, and so on are also currently used to mimic human cognition for better results with utmost efficiency [23]. In previous times, due to AI implementation for different purposes in this sector, various challenging issues arose during the operational period, hindering continuity and reducing overall efficiency. In this case, data quantity context (big data), large-scale implementation, real-time results, processing speed, systems downtimes, costing, and many other issues usually appear challenging. However, the respected researchers continue their exceptional work to mitigate these challenges by perfectly performing the AI system [23,24].

The recent progress of AI adoption and its potential prospects for the future in the automotive sector motivated us to gather valuable information to assist future research work and step ahead of this sector with more sophisticated AI technology. Numerous types of exceptional research have already been carried out independently by focusing on particular issues. For example, Fedullo et al. [25] reviewed the application of AI techniques in the automotive sector, with a focus on innovative measurement systems, advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), Internet of Things (IoT), and intelligent industrial systems to improve road safety, predictive maintenance (PdM), and build the intelligent automotive factory of the future. Subsequently, to enhance traffic control and vehicle communication in connected vehicle frameworks, Rana et al. [26] summarised a review showing a broad range of AI applications in the automotive industry beyond just ADAS, including car emissions, PdM, and security. However, the researchers suggested future studies on network architecture, connectivity, and performance metrics related to automotive AI and ML applications. Additionally, Ammal and coworkers [27] provided an overview of AI and sensor technology to develop innovative products and applications in the automotive industry, reducing human errors such as aggressive driving, accidents, and traffic collisions. Moreover, a literature study by Vermesan and colleagues [28] summarised that AI technologies enable intelligent functions and optimisation for electric-connected autonomous and shared vehicles to support sustainable green mobility. Nevertheless, decision-making mechanisms in autonomous vehicles need to be developed using AI, machine learning, deep learning, and other advanced techniques to make the processes more reliable and resilient. Despite recent review works offering valuable insights into the use of AI methods in specific aspects of the automotive sector, such as control systems, vehicle diagnostics, traffic management, autonomous driving, and accident prevention, these studies often approach applications in isolation. This fragmented analysis fails to provide a comprehensive understanding of how AI techniques interact, complement, or conflict with one another when integrated into a cohesive automotive ecosystem. Additionally, cross-functional challenges such as interoperability issues, data sharing, and real-time decision-making within interconnected automotive domains remain underexplored, limiting the potential for a unified and optimised implementation of AI in the industry. To address this research gap, it is essential to develop a holistic perspective that integrates various AI techniques, such as machine learning, deep learning, computer vision, and natural language processing, across all application areas within the automotive sector. This integrated approach would enable a comprehensive understanding of the combined potential of these technologies, uncover synergistic opportunities, and provide clarity on overarching challenges. By fostering such a consolidated framework, the automotive industry can move toward building truly intelligent, resilient, and optimised systems. Therefore, this review aims to bridge this gap by holistically examining the state-of-the-art AI techniques, assessing their collective impact, and outlining a roadmap for future research to address these integrative challenges in the automotive industry. In particular, this article infers:

i. Fundamental details about AI technology for the automotive sector;

ii. As pictorial maps, a proposed taxonomy of AI in the automotive field;

iii. Dig out the inclusive information of different AI approaches and their applications in the automotive sector;

iv. Profound analysis of benefits, associated challenges, and future application scope of AI in this sector.

Ultimately, we anticipate that this article’s outcome will represent the credible capture of AI technology’s diversified utilisation and advancement in the automotive sector. Additionally, it will assist as a robust foundation for fulfilling the demand of Industry 4.0 requirements and intensifying the adoption of AI technology in the underprivileged branches of this sector.

The remaining portions of this paper are presented in the following order. Firstly, Section 2 presents a history of AI adoption in the automotive field and utilises this information to portray the taxonomy in Section 3, besides the extensive discussion. Then, Section 4 describes the automotive-based AI conceptual framework, and Section 5 outlines the challenges and potential areas for future AI research in the automotive field. Finally, Section 6 ends this review by emphasising significant contributions and observations.

Due to the pressing need for the quick processing of large amounts of data, AI’s importance in daily life is becoming indispensable. However, this stage of AI is not achieved in a day or a year. It evolved over 70 years and started from the 1940s; indeed, 1942 through Runaround was a short story written by Isaac Asimov, the American Science Fiction writer, where he plotted a robot that allowed it to work for human beings based on some fundamental rules. Later, it inspired scientists and was first coined as “Artificial Intelligence” in 1956 by John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky through many transformations and changes [29]. In 1961, General Motors installed an AI-based industrial robot to advance the automotive industry for managing die castings smoothly. Later, they inspired and enhanced the Lordstown assembly plant using this technology in 1969. They established an AI-based automated vehicular assembly plant in the mid-1970s with MIT to expedite the vehicle manufacturing process [30]. After the industrial cases, the automotive sector also enhanced drive-in highways using this technology.

In 1979, Tsugawa and his research team [31] proposed driverless vehicles as autonomous vehicles (AVs) by recognising road patterns using TV cameras. Such autonomous vehicles could move within 30 Km/hr without driver assistance in different road environments. Also, in the early 1980s, autonomous land vehicles with AI-contained high-performance computing facilities were introduced by DARPA to run the vehicle over the highway at a maximum 45 mph speed [32]. The AI system was confined to the purposes mentioned above for the automotive sector, and it was extended to diagnosing vehicles like an expert system by 1986 [33]. Recently, this concept has attained great attention and is being applied in various cases to diagnose faults in the automotive sector to minimise downtime and increase operational time, which is discussed later elaborately. However, in the early 1990s, researchers began to realise the significance of intelligent traffic management and the employment of AI technology in this sector, which is eloquently discussed in [34]. Besides these, this technology also showed praiseworthy outcomes for intellectual vehicular performance controlling systems in 1995. Furthermore, this work inspired and upgraded AI technology to achieve supremacy for regulating vehicular performance more sophisticatedly [35].

It is noticeable that from the beginning, AI technology’s footprint significantly appeared in the automotive field for manufacturing, autonomous driving, traffic management, vehicle performance regulating, and fault diagnosing purposes [23,36]. Before 2000, AI’s evolution in this sector was in its initial stages compared to other industries. The giant leap happened in 2009, as over the last decade, Google, Tesla, General Motors, Volvo, Intel Corporation, IBM Corporation, and so forth, renowned organisations have undertaken many projects to employ AI technology with a more sophisticated approach for advancing the automotive sector to a great extent [37–39]. However, the adoption of AI is increasing outstandingly, and it is necessary to portray the taxonomy as a map of detailed implementation in the automotive field, described extensively in the upcoming section.

3 Taxonomy of AI in the Automotive Sector

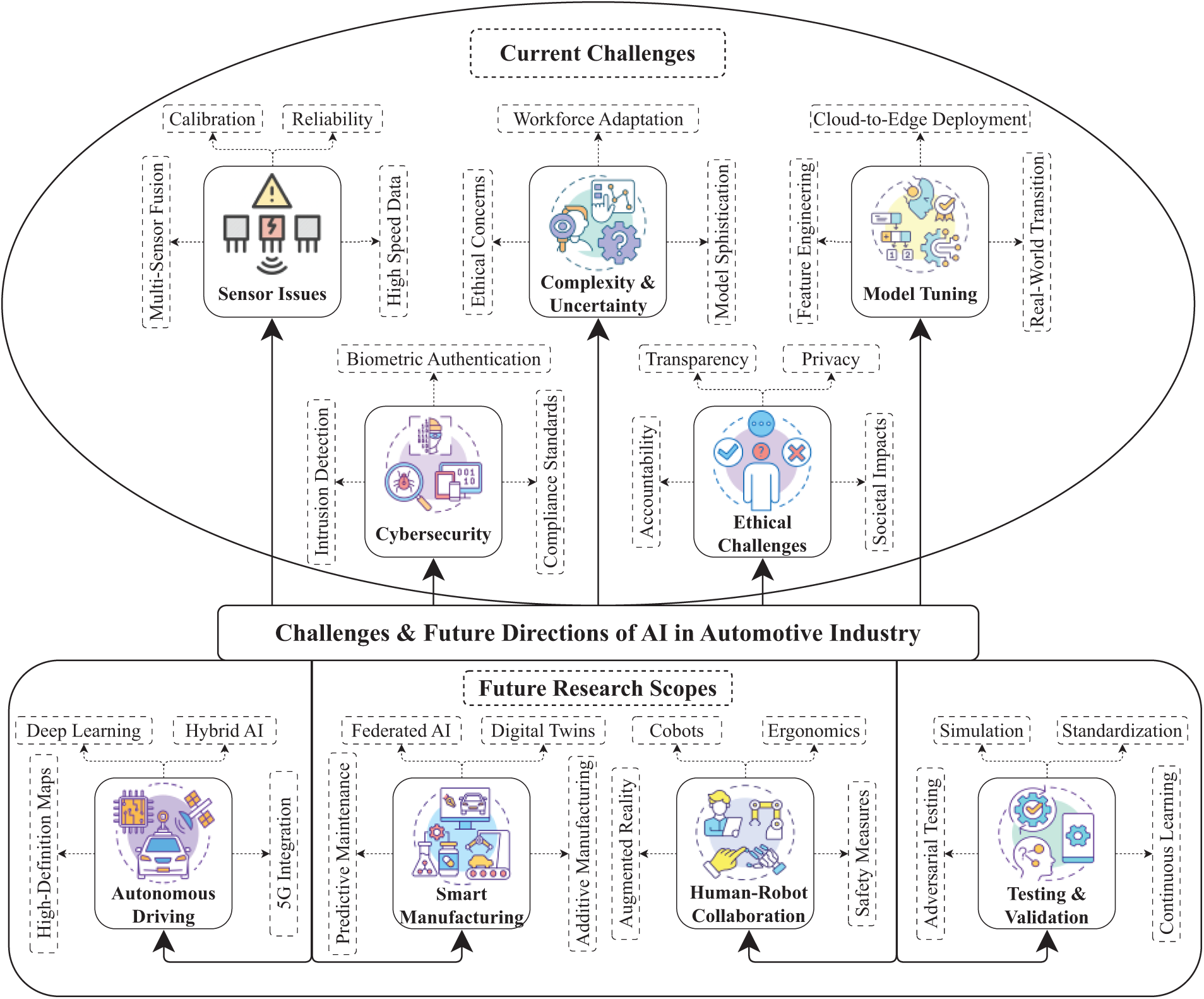

AI applications in the automotive industry have made our lives easier and more dynamic. Therefore, it is unavoidable that all the related aspects of AI in the automotive sector be depicted in an integrative format. For this reason, a taxonomy has been developed (Fig. 1) to give a clear view of AI’s employment in the automotive sector.

Figure 1: Proposed taxonomy of AI in the automotive sector

3.1 Classification of AI Systems

Through human-inspired, analytical, and humanised, depending on the intelligence exhibition (emotional, cognitive, and social) and the evolutionary stage of AI in the automotive sector, it is divided into two distinct groups: Type I and Type II [29,40].

Under this category, the employed AI technology in the automotive sector could behave like a human mind exhibiting the ability to think and feel based on the functionality of the AI system. Moreover, it is classified into four subcategories [41] and described as follows:

The AI system does not depend on memory or utilise previous experiences and decides only based on the current situation or existing scenario [42]. As a result, all control and decisions in the system might be conducted by light processing using current data. So, in this case, low-priced and limited resources are required to get better output, but in some cases may be trapped in complex environments [43]. For example, Mr Roberts and his research team proposed [44] an autonomous underground mining vehicle to ensure operator safety, reducing operational complexity using reactive machines AI. The robust reactive wall-following behaviour was the control architecture for 30 tons Load-Haul-Dump trucks.

The AI system can acquire knowledge and learn from historical data as past experiences, stored data, actions, and learnings to make subsequent decisions. That means this combination of observational data and preprogrammed knowledge is used to make the necessary decision. In this case, the past data is not stored for an extended period [40–42]. AVs are a real-world example of limited-memory machines. It can read their environment to discover patterns and changes in external elements to adapt and learn them, besides observing and understanding how to drive human-operated vehicles efficiently. Also, it can detect other vehicles and pedestrians in their line of sight [45]. Previously, such feats may take up to 100 s, but this time has drastically lowered due to recent technology and software advancements, i.e., deep learning and machine learning [40].

The theory of mind AI is a more advanced stage of AI systems than the previous two systems, which can be described as a human mind. As a result, this system may study human emotional complexities besides behavioural patterns and make predictions about their emotions, intentions, desires, thoughts, and beliefs [41]. In this case, the significant aspect involves grouping entities based on similarity, proximity, symmetry, continuity, common fate, etc. [46]. Thus, drones and AVs might benefit from this AI system because it could avoid physical harm to ordinary people and pedestrians by predicting the movements as humanity’s collective ability [47]. Also, in automotive manufacturing environments, it could help measure employees’ perceptions and behaviour to expedite the manufacturing process [48].

The last step of AI system development is self-aware AI, which currently exhibits hypothetically, and in this case, will attain human-level perception, emotions, desires, and independent decision-making ability based on its own moral compass and philosophical approach. Respected researchers are working on adopting it in the automotive sector, such as AVs, autonomous manufacturing systems, and industrial management; it has a broad scope to continue safe and effective operations in all cases [49].

In this context, AI technology classified based on capabilities and technology in the automotive sector could be organised into three subcategories [49], which are discussed as follows:

Narrow intelligence can be defined as not exhibiting intelligent functionality beyond the particular application domain precisely on what they have been programmed to do [41]. Widely, it performs efficiently on specific tasks based on the given initial training, but generalisation ability is missing except for these particular tasks [48]. Such limited focus capabilities represent AI’s narrowness, also termed “weak AI” [41]. However, the examples of narrow intelligence are related to afore-discussed reactive machines and limited-memory machines AI. Also, in some cases, the theory of the mind machine’s rudimentary examples is involved [40].

Artificial general intelligence can be defined as a system that not only performs like a weak AI. However, that system also has the capabilities or functionalities to understand, learn, perceive, and make decisions entirely the same as human beings [46]. That means the system in the automotive sector could perform any operation like a human without human fatigue besides error [40]. Because of this, it is also called “strong AI.” Moreover, though it does not exist, the continuous development and advancement of narrow AI in the automotive sector minimised the distance between humans and AI machines’ capabilities. Therefore, hopefully, it will lead to general intelligence very soon [41].

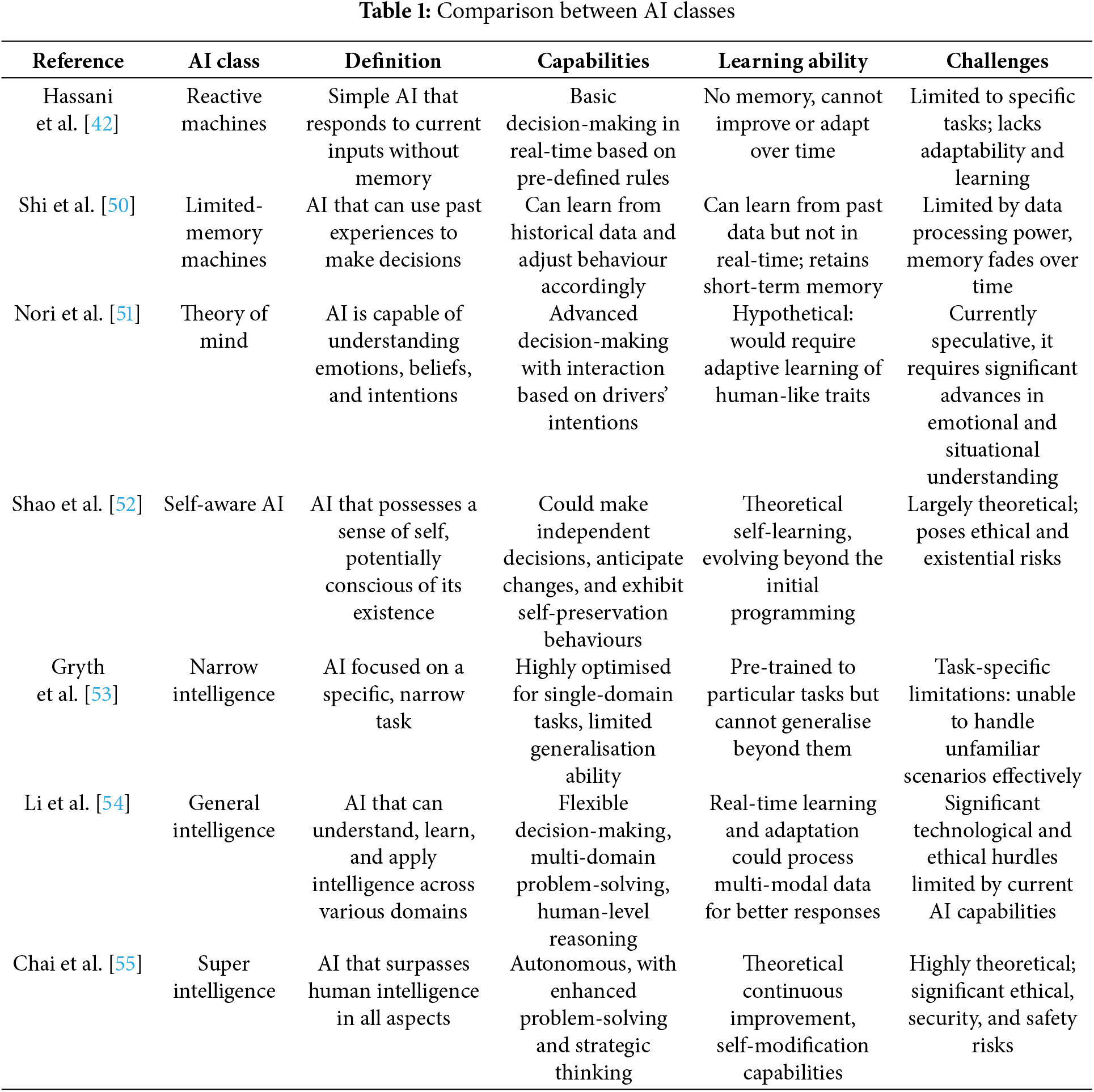

It is still in the conceptual stages where the AI system in the automotive sector could have higher cognitive functional capabilities than the human brain. However, since it exists hypothetically, it is hoped that the system may have the total ability to perform moving and transportation services due to enhanced memory besides significantly faster data processing, handling, and decision-making abilities [23]. Table 1 presents the fundamental differences between the different categories of AI in various aspects.

3.2 AI Techniques Used in the Automotive Sector

Commonly used techniques or advanced methods of AI in the automotive field have been applied to perform human-like or superhuman behaviour to operate or maintain the desired system smoothly. For manufacturing, autonomous driving, traffic management, vehicle performance regulating, and fault-diagnosing purposes, various AI approaches and fundamental techniques are currently used to mimic the human brain’s working principle in the automotive sector, described as follows:

Machine learning is an algorithm that learns from the data without depending on rules-based programming. Currently, the ML technique is one of the most effective AI tools for resolving various issues in the automotive industry. By exploring the algorithm’s construction and learning mechanisms, ML can study data patterns to predict the most probable outcomes with high accuracy [56]. Additionally, it shares many similarities and overlaps with computational statistics. Based on the learning nature of the automotive field, it is classified into four categories [57], as depicted in Fig. 2; these are explained as follows.

Figure 2: Machine learning techniques for automotive applications

The supervised learning approach is an AI algorithm generally trained by the labelled input data to predict or provide a firm decision. This approach is primarily suitable for classification in the automotive field besides solving regression problems, and various algorithms are available to achieve the desired outcomes [57]. In this case, supervised learning includes techniques like support vector machines (SVM), K-nearest neighbour (KNN), decision trees (DT), random forest (RF), logistic regression, linear regression, and others. However, in the last decade, the supervised technique has been utilised in the automotive sector for various purposes, where the system is initially trained by feeding required information and later run using the testing data. For instance, Harold et al. [58] proposed a powertrain control framework for hybrid electric vehicles (EV) that uses the supervised learning technique to improve fuel economy, and they achieved a satisfactory outcome over dynamic environments. Furthermore, due to better performance in decision-making and classification, this technique is also implemented in the automotive industry to control manufactured vehicle quality by scrutinising the vehicular body’s panel surfaces [59]. Similarly, last few years, the demand for supervised learning techniques in the automotive sector has risen significantly for various purposes, i.e., estimation of moving vehicle’s road friction [60], improving quality of service for intelligent transport systems [61], performing roundabout manoeuvres for AVs [62], fault detection of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) [63], predictive maintenance and risk management [64,65], supply chain management [66], and so forth. However, supervised learning is highly dependent on large, high-quality labelled datasets, which are costly and time-consuming to obtain, particularly for the extensive edge cases seen in real-world driving environments. This reliance on labelled data creates a contradiction: while supervised learning delivers accurate results within a controlled scope, it lacks flexibility, and its performance in dynamic, real-time situations (e.g., autonomous driving) often necessitates additional support from semi-supervised or unsupervised learning for comprehensive adaptability.

In machine learning, the unsupervised learning approaches can be defined as the AI algorithm models or systems that are not supervised based on the labelled training dataset to draw affirmative inferences. This method is crucial in the automotive industry to uncover hidden data for specific purposes, and it currently makes use of a variety of well-liked algorithms, including hierarchical clustering, K-means, self-organising maps, and many others [67,68]. Moreover, this technique significantly improves in some cases compared to supervised learning techniques. For example, an unsupervised learning approach in the automobile manufacturing industry provided praiseworthy performances for detecting the fault and failure prediction of power transmission systems, pneumatic actuators, and valves [69]. Similarly, the K-means clustering algorithm was used by Shaeiri and coworkers [70] as an unsupervised learning approach for vehicular self-maintenance purposes and profiling driver behaviours. They found that the proposed system successfully assists the user. Besides these purposes, day by day, the implementation of this technique in the automotive field is increasing considerably, i.e., real-time automobile insurance fraud detection [70], CAN-based modern vehicle transmission systems [71], enhanced driver assistance systems [72], and so forth. However, unsupervised learning presents notable disadvantages, particularly the difficulty of validating results and the risk of identifying irrelevant patterns, as there is no labelled data for model guidance. This lack of interpretability can hinder safety-critical applications, where understanding the model’s rationale is essential. Contradictions arise in scenarios like autonomous driving, where accuracy and safety are paramount. However, unsupervised learning provides flexibility and speed; it often requires subsequent validation with supervised methods, raising concerns about reliability and the need for hybrid approaches to balance accuracy with adaptability.

It can be defined as the ML approach, where the system is trained by feeding a small amount of labelled data with a large quantity of unlabelled data as a mixture of data. In general, it helps to overcome some difficulties in supervised and unsupervised learning cases where managing a substantial amount of training data is difficult [73]. Semi-supervised learning outperformed supervised models in vehicle trajectory prediction by leveraging large amounts of unlabelled data, thus scaling up the training process and improving accuracy [74]. Additionally, these methods have shown high effectiveness in detecting various network attacks in automotive Ethernet, achieving impressive detection rates [75]. For example, Hoang and the research team [76] employed semi-supervised learning to detect various in-vehicle intrusion attacks, including known attacks like denial of service, fuzzy, and spoofing, as well as unknown attacks. Nevertheless, one major drawback is the difficulty in handling datasets with few labelled samples, as traditional broad learning systems struggle to effectively utilise the information between labelled and unlabelled data [77]. Furthermore, the increased interconnectivity in automotive Ethernet introduces new vulnerabilities. While semi-supervised learning can enhance detection, it is still susceptible to unknown attacks due to the developing nature of this research area [75].

Reinforcement learning is a promising ML technique in which the intelligent agent learns from experiences rather than a training dataset and is concerned with initialising the action in the potentially complex and uncertain environment to maximise reward or outcome by taking a sequence of suitable decisions. Particularly, in the RL paradigm of the automotive field, an autonomous agent interacts with its environment to perceive and learn how to improve its performance at a given activity through a series of trials [78]. In addition, its employment proliferation recently appeared and grew dramatically in this field to mitigate complex issues smartly. Moreover, Navarro et al. [79] found that for developing a simulated environment and control strategies of an AV, this approach is cost-effective and requires the lowest data solution than the traditional algorithm. Again, it has extreme significance for vehicle routing problem solutions, and Nazari’s research team revealed it, proposing an end-to-end framework for self-driven learning [80]. Recently, to get better outcomes in this sector, the RL approach enhanced deep reinforcement learning (DRL) by combining its architecture with ANNs, where software-defined agents enable learning best. As a result, it has performed praiseworthy in autonomous driving [78,81], UAV navigation [82,83], unmanned surface vehicles [84], and many others for environment recognition, decision-making, and controlling system advancement. However, the lack of standard tooling solutions for RL-based function development in the automotive industry remains challenging [85]. Furthermore, while RL can theoretically enhance driving policies, practical implementation requires reliable fallback mechanisms and high-fidelity simulators to ensure safety and effective policy transfer from simulations to real-world applications [86,87].

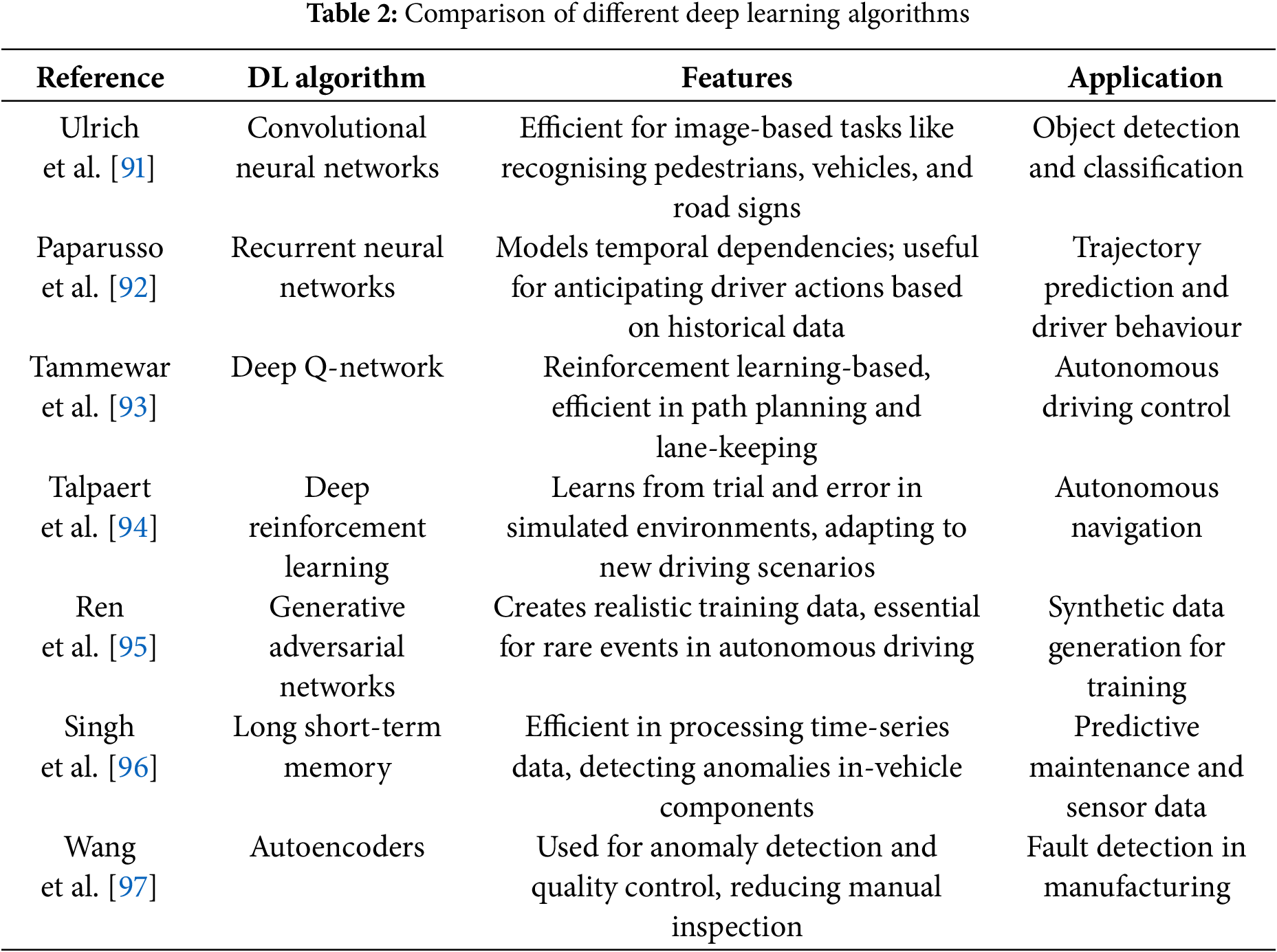

The deep learning technique in AI consists of ML algorithms that use multilayered ANNs to mimic human intelligence by learning and making the best decision, with the most layers acting as the hidden layer. Its effectiveness has been demonstrated outstandingly for any purpose in the automotive branch, and implementation is rising dramatically [88]. The significance of DL was realised by Chen’s research team [89] from Cardiff University, UK, for predictive vehicle maintenance based on maintenance history and geographical information system (GIS) data. It outperformed based on real-world information than other traditional approaches and anticipated that it would reduce the fleet management organisations’ maintenance-related burdens. Similarly, Naqvi et al. [90] achieved greater accuracy in mitigating accidental issues due to inconsistent driver behaviours. The results were much better than those obtained in previous research using a convolutional neural network (CNN) and DL technique with pupil centre corneal reflection-based method.

Again, for demand forecasting and inventory management of automobile spare parts, the DL approach (modified Adam optimiser with recurrent neural network (RNN)/long short-term memory (LSTM)) performed well and provided less error than available other methods [98]. Moreover, its footprints are also extensively sketched in remote sensing of UAVs for various purposes in urban, agricultural, and environmental contexts. Gated recurrent unit (GRU), Bi-GRU, Bi-LSTM, and DL approaches are prominently used for fault diagnosis and identification in this sector [99]. Table 2 presents how various DL algorithms enhance automotive applications like driver assistance systems and traffic management, improving safety and efficiency. However, these techniques demand significant computational resources and extensive training data to ensure reliability and safety in real-world scenarios. Therefore, contradictions arise in balancing the rapid advancements in DL with the automotive industry’s stringent safety and validation requirements, highlighting the need for ongoing research and development to address these challenges.

The heuristic technique is an approach for the specific problem that implements the practical method or numerous shortcut approaches and often gives satisfactory solutions more quickly than other classic methods [100]. In the automotive sector, day by day, its application is increasing satisfactorily due to its quick problem-solving features. For instance, decomposition strategies in vehicle routing heuristics can significantly enhance performance by breaking down significant problems into manageable subproblems, as demonstrated by the superior performance of route-based decomposition methods over path-based methods [101]. In addition, the heuristic method with improved multi-choice goal programming is used in the vehicle-related logistics system to design a green supply chain management system by adopting carbon regulation as greener practices [102]. Similarly, Pérez’s research team [103] found that the automotive industry could benefit from the logistic system by minimising transportation costs through minimum touring distance, loading-unloading operations, and proper decision-making using the heuristic algorithm. However, the primary disadvantage of heuristic methods is that they often rely on rule-of-thumb approaches that may not guarantee optimal solutions and can lack robustness across varying conditions, potentially leading to inconsistent performance. Furthermore, though they provide practical solutions for quick decision-making, their reliance on approximations and empirical rules may fall short in applications requiring high precision and predictability.

3.2.4 Metaheuristic Techniques

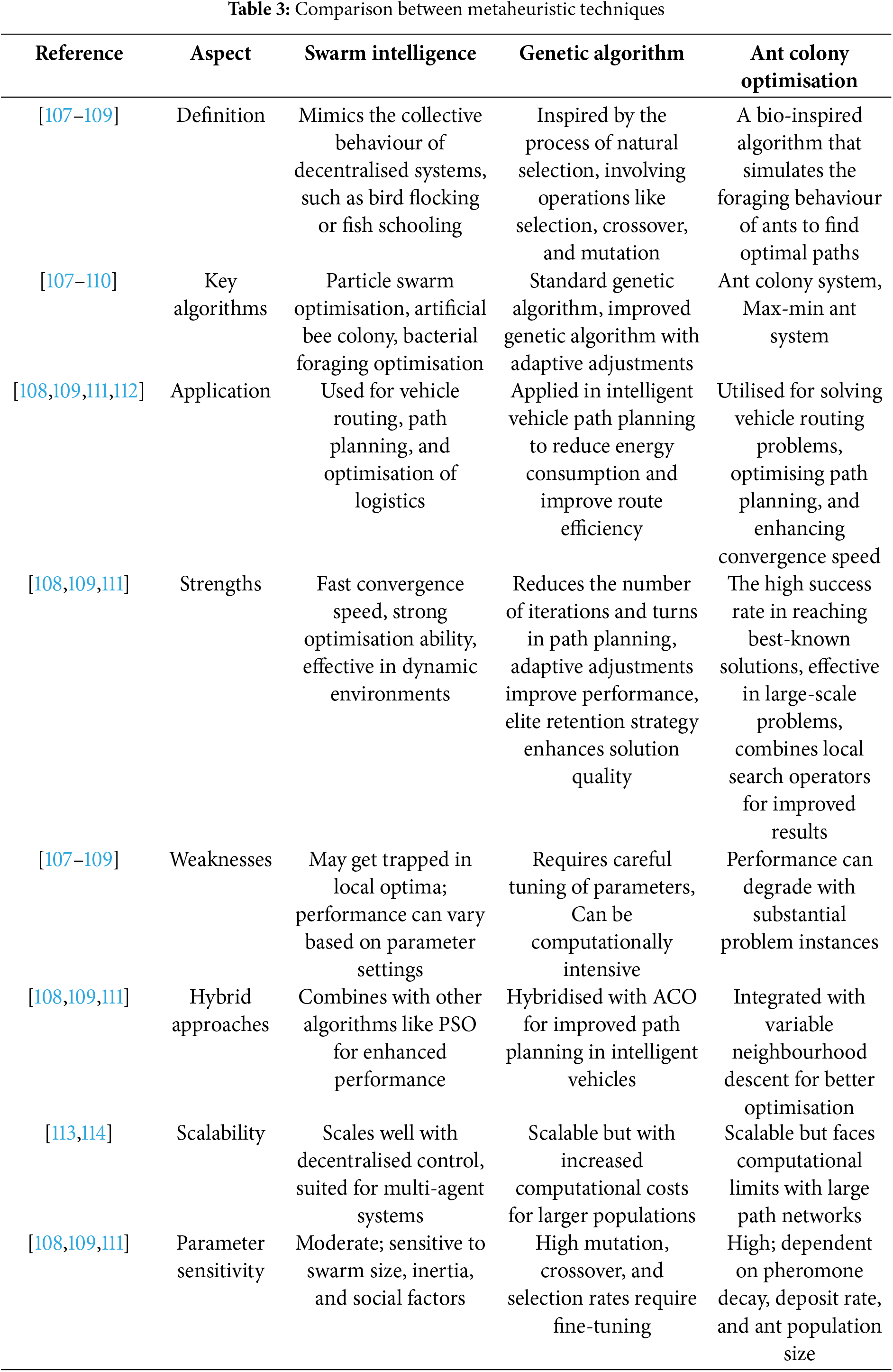

Metaheuristic approaches emerged as versatile problem-solving tools that operate independently of specific problems, employing innovative strategies based on heuristic principles to resolve various challenges. Here, the prefix meta indicates the high-level methodological nature [104]. These techniques, such as those developed for vehicle routing problems, provide robust solutions to complex combinatorial optimisation issues by iteratively exploring and exploiting the search space, often outperforming traditional performance and conceptual originality [105]. Nature-inspired meta-heuristics, in particular, have been successfully applied across various domains, including automotive logistics, due to their flexibility and ability to handle diverse problem sets [106]. Table 3 summarises some innovative approaches to these techniques used in the automotive sector to optimise a broad range of complex issues perfectly.

Apart from machine learning, statistical learning can be defined as mathematics intensive, which means formalised relationships among the variables in a mathematical equation. Also, it forms a hypothesis before building the model; besides, it depends on the smaller dataset with some attributes and operates under assumptions compared to ML (because ML requires a massive data set to learn algorithms and is not assumptions dependent) [39]. However, it could be categorised into three categories: natural language processing, gesture recognition, and speech recognition (Fig. 3). Firstly, NLP is the AI approach that may help the system or machine recognise, manipulate, and interpret human language efficiently. Its significance in the automotive field is massive in utilising structured and unstructured data for various cases, such as driving improvement, customer service enhancement, and resource management improvement [115]. Also, this technique could assist the driver at the time of the journey if the driver asks for any assistance regarding the vehicle owner’s manual, where it can convert the information of the manual into text [116]. Secondly, gesture recognition is the approach to establishing human-machine interaction using only body actions instead of voice. In the automotive field, gesture recognition is usually conducted through three stages, i.e., detection, tracking, and recognition. Tateno et al. [117] developed a gesture-based control system using an infrared sensor array installed in vehicles. The system recognises seven distinct hand movements to control the vehicle’s directional movement through a CNN-powered data processing mechanism. Finally, speech recognition involves understanding a person’s words through a computer and translating them into a machine-readable format. This AI feature facilitates driving vehicles without distraction to ensure a safe and comfortable journey in the vehicle. Its application for different purposes in automotive is also notable, and employment of this technique is escalating with changing times. For example, a DL-based speech recognition system was developed for Arabic drivers to reduce distraction and improve human-vehicle interaction [118]. The study achieved high speech recognition accuracy of over 94% for noise-free audio and over 91% for noisy audio using various acoustic models. However, implementing the above approaches in the automotive sector presents numerous challenges. NLP systems must handle context understanding, multilingual support, and integration with other systems. On the contrary, gesture recognition faces accuracy, real-time processing, and user variability issues. Furthermore, speech recognition systems must overcome noise interference and low signal-to-noise ratio conditions, with advanced speech enhancement techniques offering potential solutions.

Figure 3: Automotive applications of statistical learning approaches

Game-theoretic learning is an approach in the AI field where a player among a set of players as the individual agent can make the optimal decision (prediction) of each other sequentially for upcoming actions, and the outcome comes from these decisions [119]. So, it explains how the agents strategically might learn from the consequences of social interaction in the long run and adopt the behaviour. It has shown significant promise for self-driving vehicles in enhancing decision-making processes and improving safety and efficiency in complex traffic environments. Various studies have integrated game theory with deep reinforcement learning to model interactions between multiple vehicles, including human-driven ones, in diverse scenarios. For instance, one approach combines DRL with game-theoretic decision-making to enable AVs to navigate unsignalized intersections by modelling different driving behaviours and anticipating the reactions of other vehicles without explicit communication [120]. Another study formulates lane-changing decisions as games between pairs of vehicles, using neural learning to adjust payoff matrices and optimise behaviour [121]. Additionally, game-theoretic planners have been developed for competitive scenarios, such as autonomous racing, where vehicles employ strategies like blocking and overtaking to outperform others. These planners often outperform traditional model-predictive control methods by considering vehicle interactions [122]. Furthermore, multi-agent planning algorithms have been proposed to handle interactions with human drivers at intersections and roundabouts, assigning priorities based on observed driving styles to prevent collisions and deadlocks [123]. However, multi-agent interaction involves predicting and responding to the behaviours of numerous traffic participants, including other AVs, human-driven cars, and pedestrians. This complexity is compounded by the need for real-time decision-making, which requires efficient computational algorithms to ensure safety and optimal performance. The integration of game theory with DL and memory neural networks has also been explored to predict opponent behaviours and enhance path planning in dynamic environments [124]. However, robustness against unpredictable behaviours of human drivers and the dynamic nature of traffic environments also poses a significant hurdle, necessitating advanced models that can adapt to varying conditions and uncertainties.

Fuzzy logic is a reasoning method in AI that imitates human reasoning for decision-making by manipulating or representing uncertain information based on the degree of truth or a partial truth that could be all intermediate possibilities for any actual number between o to 1 [125]. Vehicle designers have leveraged fuzzy techniques in the automotive sector to enhance dynamic control analysis, providing a cost-effective solution for examining vehicle performance during driving modelling. One commonality of this method for application in different automotive aspects is its ability to handle uncertainty and subjectivity, which is crucial in applications ranging from failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) to demand forecasting and energy efficiency evaluation [126,127]. For instance, fuzzy logic enhances traditional FMEA by incorporating expert knowledge to more effectively analyse subjective failures [128], and it is also used to predict vehicle ranges in EVs by considering dynamic parameters [129]. Moreover, its applications extend to Industry 4.0 readiness assessments, demonstrating versatility across different analytical domains [130]. These applications highlight the flexibility of fuzzy logic but also underscore the differences in its implementation based on the problem being addressed. Contradictions arise in the perceived efficiency and accuracy of fuzzy logic models. For instance, while the Mamdani-type fuzzy logic model is praised for its high accuracy in evaluating vehicle energy efficiency [131], other studies suggest that integrating fuzzy logic with different techniques, such as neural networks or big data analytics, can yield more robust and reliable results [126,132]. This denial suggests that fuzzy logic is a powerful tool. Still, its effectiveness can be context-dependent, and combining it with other methodologies may enhance its utility in the automotive sector.

3.2.8 Hybrid Intelligent Systems

In the automotive sector, hybridisation systems combine multiple AI methodologies, such as machine learning, rule-based systems, and optimisation algorithms, to enhance decision-making and control systems, particularly in autonomous driving, predictive maintenance, and driver assistance systems. These approaches share an analogy in their objective to improve accuracy, adaptability, and robustness by compensating for individual limitations of each AI technique, such as integrating rule-based systems for interpretability with ML for adaptability. For instance, the use of hybrid human-AI in semi-autonomous driving systems aims to leverage human judgment alongside AI capabilities to improve system reliability and performance [133]. Similarly, the ML-multi-agent system framework combines ML models with rule-based agents from symbolic AI to address the limitations of ML-only approaches, thereby enhancing the driving score in fully autonomous vehicles [134]. Recently, Rahim et al. [135] developed a CNN-BiGRU-based hybrid decision model for vehicular engine health monitoring that combines CNN for feature extraction and BiGRU for handling sequential dependencies in time-series engine data. They achieved high decision accuracy (0.8897) with low decision loss, surpassing conventional models by integrating sensor data with structural and vulnerability assessment information for improved PdM. Furthermore, hybrid systems offer a promising approach to overcoming some of the current limitations faced by fully autonomous vehicles. By integrating hybrid electric vehicle technology with autonomous driving systems, several practical benefits can be realised.

Energy Efficiency and Management

Hybrid systems can significantly enhance the energy efficiency of AVs. For instance, the integration of intelligent driver assistance systems, such as adaptive cruise control (ACC) and energy management systems, can optimise energy consumption. These systems use advanced control strategies like model predictive control and neuro-fuzzy systems to maintain safe distances and manage acceleration, thereby reducing energy waste and improving fuel efficiency by up to 2.6% [136]. Additionally, hybrid powertrains allow AVs to achieve similar energy savings with smaller motors compared to those required by human drivers, thanks to more optimal torque requests and efficient engine operations [137].

Hybrid control models can improve the robustness and adaptability of AVs under various driving conditions. For example, combining model predictive and Stanley-based controllers can enhance vehicle control and path-following capabilities, ensuring better performance in diverse scenarios [138]. Moreover, hybrid ML-based control strategies can optimise driving performance and smoothness, addressing limitations in existing control systems [139].

Hybrid systems in AVs can also contribute to reducing environmental impact. By employing advanced fuzzy logic control for energy management, hybrid electric AVs can decrease fuel usage and extend battery life, leading to a reduced carbon footprint [140]. This aligns with the automotive industry’s goals of sustainability and reduced emissions.

Integration with Urban Traffic Systems

In urban environments, hybrid systems can facilitate the coexistence of autonomous and non-autonomous vehicles. For instance, creating exclusive lanes for AVs and allowing them to travel in platoons can reduce travel times and improve traffic flow, as demonstrated in simulations using real-world data [141]. This hybrid approach can ease the transition to fully autonomous urban mobility.

By enhancing energy efficiency, control, safety, and environmental sustainability, and by facilitating integration with existing traffic systems, hybrid systems can address many of the current limitations of AVs. However, the development and deployment of these hybrid systems face complexities related to algorithm portability and the standardisation of software development processes, which are crucial for mass production and industrial applications [142]. Subsequently, integrating AI into existing vehicle systems requires significant modifications and validation to ensure safety and compliance with regulatory standards, which can be resource-intensive and time-consuming [143].

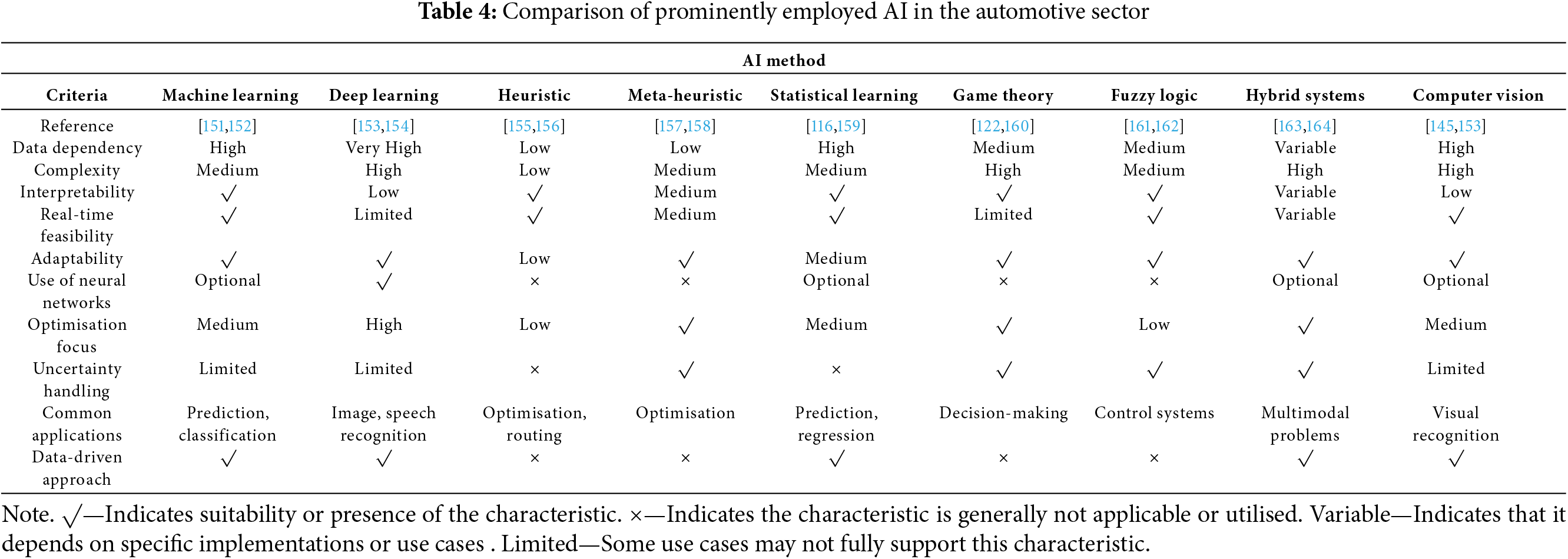

In AI, computer vision for vehicles empowers them to perceive everything in their surroundings or natural environment without human assistance. The application of computer vision techniques in the automotive sector has been explored extensively, revealing converging and diverging viewpoints among researchers. Several studies highlight the potential of computer vision for enhancing safety and efficiency in automotive applications. For instance, edge and ellipse detection, camera calibration, 3-D reconstruction, and stereo vision have been successfully applied to detect rims, estimate calibration angles, and reconstruct vehicle trajectories, demonstrating the versatility of these methods in solving complex vehicle problems [144]. Similarly, integrating this method with Industry 4.0 technologies, such as remote sensing data fusion and mapping tools, has improved collision avoidance and environment mapping [145]. However, there are notable differences in focus. At the same time, some researchers emphasise the role of computer vision in ADAS for safety purposes, highlighting the superiority of DL techniques over traditional methods [146]. Others concentrate on its application in manufacturing for quality control and defect detection [147,148]. While some studies advocate for the immediate integration of self-adjusting computer vision systems to achieve zero-defect manufacturing [147], others point out the slow-growing R&D infrastructure in certain regions, which could hinder such advancements [145]. Additionally, the use of computer vision for non-contact weigh-in-motion systems [149] and error detection in vehicle parts [150] further illustrates the diverse applications and ongoing research gaps in this field. However, Table 4 compares various criteria of the AI methods mentioned above.

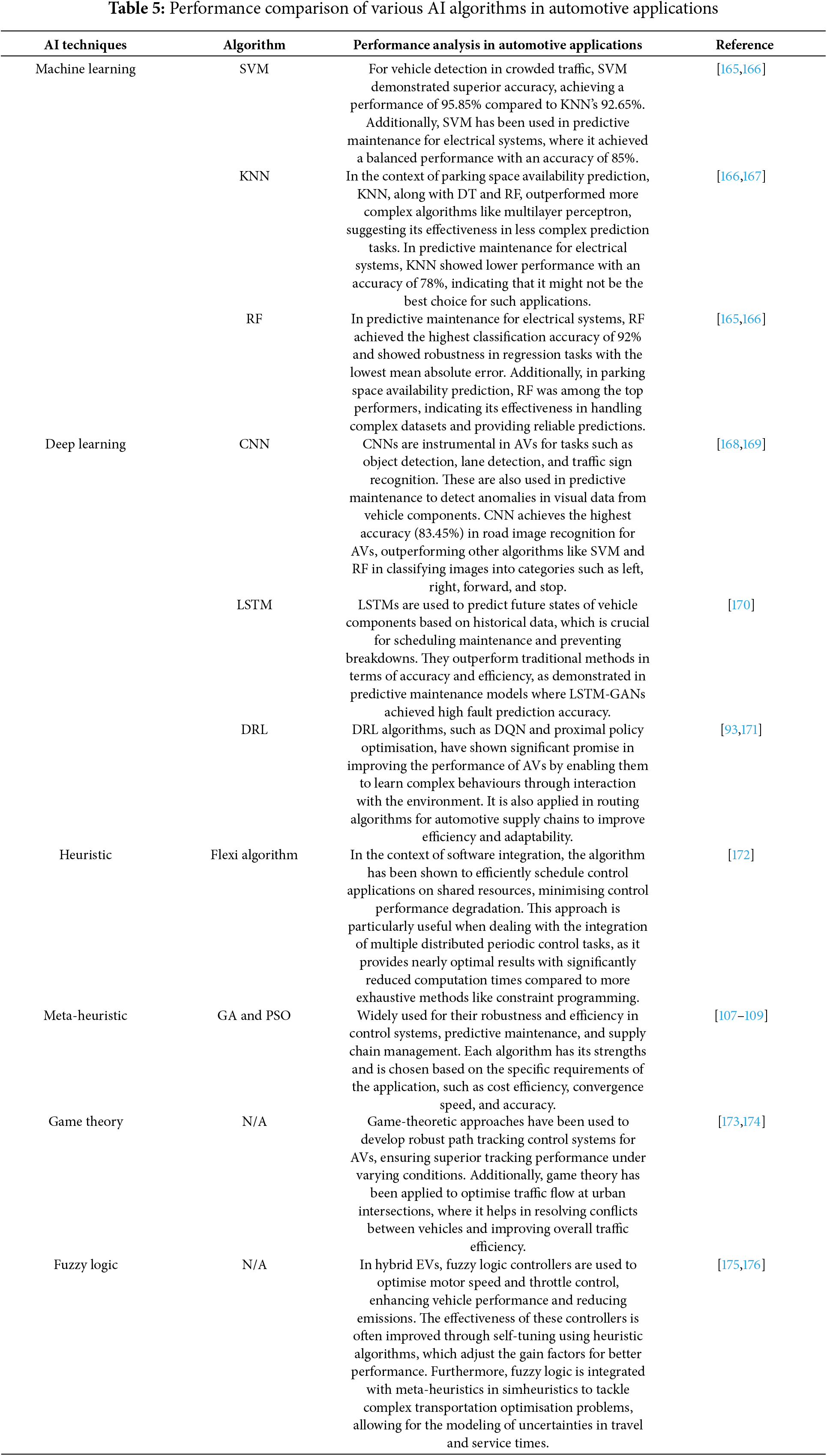

Various AI algorithms in the automotive sector have been critically evaluated and compared based on key performance metrics, as shown in Table 5.

3.3 Overview of AI’s Applications and Opportunities

Recently, AI’s application in the automotive sector has been increasing outstandingly to ensure intelligent services, computing, networking, and security purposes, exploiting the most efficient techniques. The prominent purposes of AI in this sector are described as follows.

3.3.1 Advanced Driver Assistance Systems

Advanced driver assistance systems are a recent automotive innovation that enhances safety and comfort by automatically detecting and responding to potential road hazards through environmental sensing and interpretation [177]. ADAS provides automobiles with a mix of sensor technologies and AI processing algorithms that perceive the environment surrounding the vehicle, process it, and then either present information to the driver or take action [178]. The state-of-the-art sensors used in this system for various functions are RADAR (radio detection and ranging) (long range, short or medium range), LiDAR (light detection and ranging), camera (monocular, stereo, and infrared), and ultrasonic sensors [179]. The integration of AI in ADAS has led to the development of sophisticated algorithms, which enable the system to adapt to different driving environments and user preferences [180,181]. To assure the highest degree of safety, reinforcement learning algorithms have recently been applied for many levels of task repetition. For example, Gonjalo et al. [182] created a prototype variable message sign reading system with the help of ML techniques to improve road safety, in which images were preprocessed and delivered to an optical character recognition model, and subsequently converted to announcements using IBM Watson Text to Speech. Moreover, Salve et al. [183] proposed a CNN model with two output layers that can provide an alert through an alarm when the driver is continuously predicted to be exhausted. The applications of ADAS consist of adaptive cruise control (ACC), collision avoidance (CA), and automatic parking, among many others [184], which are discussed as follows.

This critical ADAS component integrates onboard sensor data to maintain safe following distances and prevent forward collisions with preceding vehicles [185]. RADAR technology emits microwave sequences to estimate object distance and speed, while LiDAR provides high-resolution object detection by projecting beams and calculating distances in ACC-equipped vehicles [186]. AI techniques, particularly DL neural networks, have been employed to improve the predictive control of ACC systems. For instance, neural network predictive control has been utilised to mimic vehicle dynamics and optimise control actions, demonstrating improved performance in maintaining safe distances and adapting to dynamic driving conditions [187,188]. Moreover, personalised ACC systems, which adapt to individual driving styles using AI, have also been developed to enhance user comfort and safety by learning and adjusting to real-time driver feedback [189]. Furthermore, innovative methods for scene recognition and target tracking in complex traffic environments have been proposed, leveraging multi-sensor fusion and advanced filtering techniques to improve the robustness and accuracy of ACC systems [190]. According to an analysis, traffic congestion could be efficiently eliminated when 25% of highway vehicles are equipped with ACC [191].

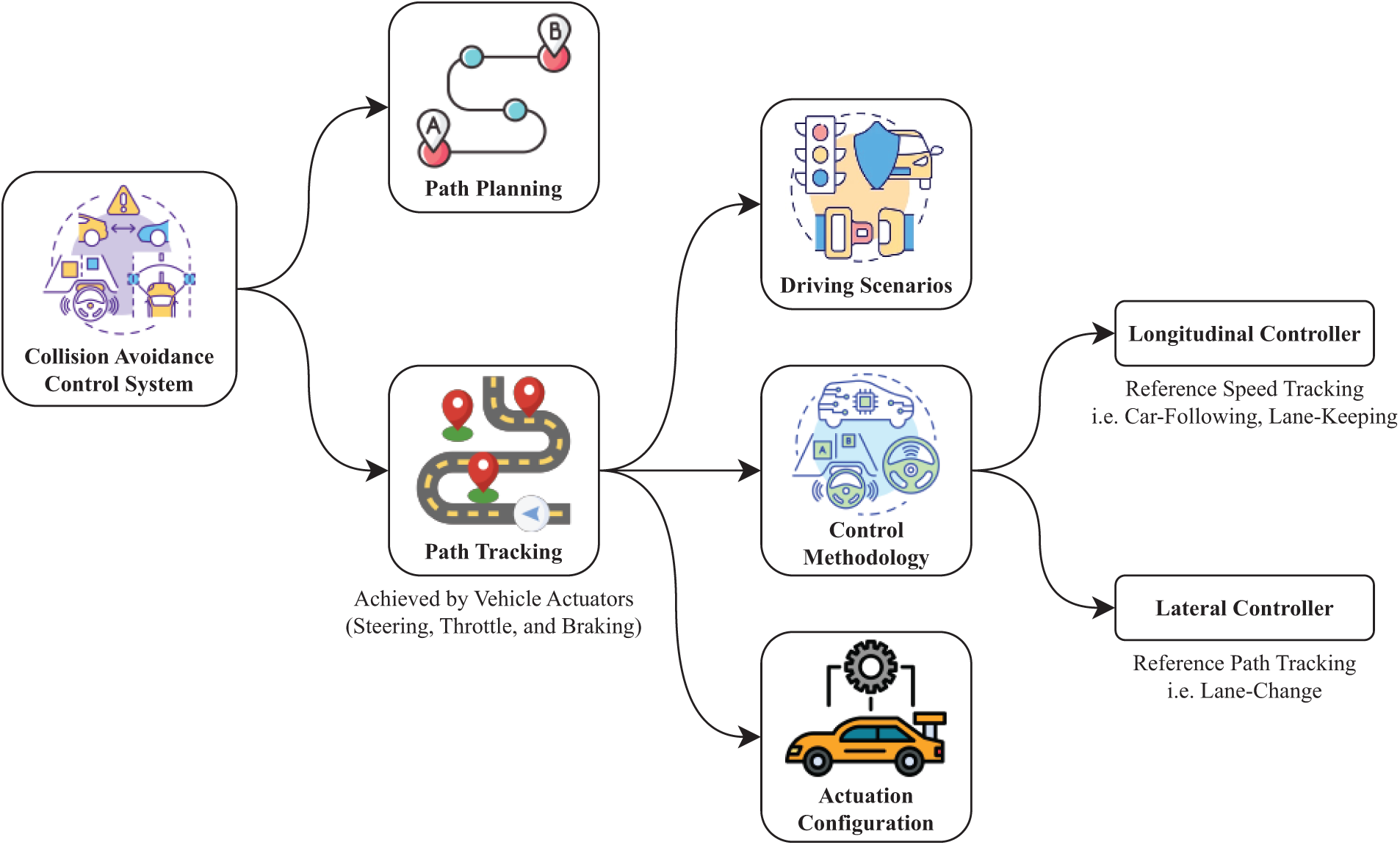

Collision avoidance, a sophisticated ADAS component in autonomous vehicles, prevents potential collisions by alerting drivers to environmental hazards [192]. It usually follows two strategies for risk assessment, i.e., path planning and path tracking strategies [191], and the process is briefly presented in Fig. 4. The path planning component designs a collision-free route by analysing current road conditions. In contrast, path tracking ensures the vehicle adheres to this route using feedback adjustments. The risk assessment is used to quantitatively analyse the objects’ risk level from where collisions can be predicted. After a proper risk assessment of imminent collision, the vehicle will replace the current route and follow the replanned route using a path-tracking strategy. It addresses various driving scenarios, such as lane-keeping and lane-changing, by configuring control parameters specific to each scenario. The system relies on vehicle actuators—steering, throttle, and braking—to execute manoeuvres and adapt in real time. Two controllers, longitudinal (for speed control in car-following) and lateral (for lateral movement in lane-changing) work together to maintain safe and stable vehicle behaviour. Yu et al. [193] developed spatial-temporal CA algorithms using ML to enhance collision prediction accuracy and optimise AV decision-making. Additionally, a CA model was proposed by Rill et al. [192] that used optical flow and monocular depth estimation based on DL techniques to estimate the ego vehicle’s speed depending on the lead vehicle’s distance. However, challenges like restricted fields of view and inaccurate range information generated from vision-based methods have been addressed by developing a multi-sensor approach that integrates LiDAR data for precise time-to-collision calculations [194].

Figure 4: Collision avoidance system using AI

Automatic parking systems represent a pinnacle of vehicle automation, seamlessly integrating real-time sensor data with sophisticated motion planning algorithms. By synthesising environmental inputs from an array of sensors, these systems can execute precise parallel, angled, or perpendicular parking manoeuvres autonomously, effectively removing the complexity and stress traditionally associated with challenging parking scenarios [191]. Ultrasonic sensors are used in these systems to store information about parking spaces when a vehicle exits its parking spot. Afterwards, based on a two-dimensional map, RADARs are employed to locate appropriate parking places [195]. Recently, numerous researchers have applied DRL to develop an automatic parking model to ensure more complex and efficient operations. For example, Zhang and coworkers [196] proposed that reinforcement learning-based end-to-end parking algorithms allow vehicles to learn optimal steering commands through continuous experience, thereby reducing path-tracking errors and improving parking accuracy. Additionally, the fusion of camera sensor data and RADAR enhances these systems’ perception and decision-making capabilities, enabling more reliable multi-target matching and scenario extraction [197]. Furthermore, Guo et al. [198] designed an automatic parking system using an improved DL algorithm, which resulted in 34.83% less time-consuming than manual parking.

3.3.2 Vehicle Health Monitoring Systems

AI-enabled vehicle health monitoring systems (VHMS) use sensor networks and diagnostic algorithms to monitor component conditions and detect abnormalities in modern vehicles. The system collects information from the engine body, fuel flow system, engine speed, etc., using connected sensors, Arduino, and the cloud [199]. Therefore, any abnormal behaviour from single or multiple vehicle components is reported instantly through VHMS so that safety precautions can be taken rapidly to avoid complete vehicle failure. Recent studies have emphasised the integration of AI technologies to enhance vehicle health management capabilities. For instance, Rahman et al. [200] have suggested a conceptual framework for a central VHMS based on multi-layer heterogeneous networks. They advocated an ML approach in this scenario to monitor individual vehicle health concerns, warn drivers, and create data for future necessary measures. Moreover, the use of DL for monitoring engine vulnerable components [201], signal integrity tracking, and fault detection [202] are highlighted as some of the significant advancements. Similarly, the application of AI for real-time diagnosis and prognosis in vehicular systems is underscored, with a focus on the powertrain and drivetrain components. However, there are notable differences in the approaches and technologies employed. Though some researchers advocate using unsupervised DL models to simplify data collection and labelling processes [202], others propose using dynamic Bayesian networks for fault detection and prognosis in AVs [203]. Additionally, using lightweight computational intelligence for IoT health monitoring in off-road vehicles, leveraging economic sensors and edge devices presents a cost-effective alternative to traditional methods [204]. Nevertheless, researchers contrast the dependence on cloud-based vs. edge-based solutions, with some studies emphasising the need for cloud computing to handle big data [202]. In contrast, others highlight the limitations of cloud dependence in rural areas and propose edge-device-enabled solutions [204]. These perspectives underscore the diverse methodologies and technological preferences in AI-based vehicle health monitoring, reflecting both the potential and the challenges of implementing such systems across different vehicle types and operational environments.

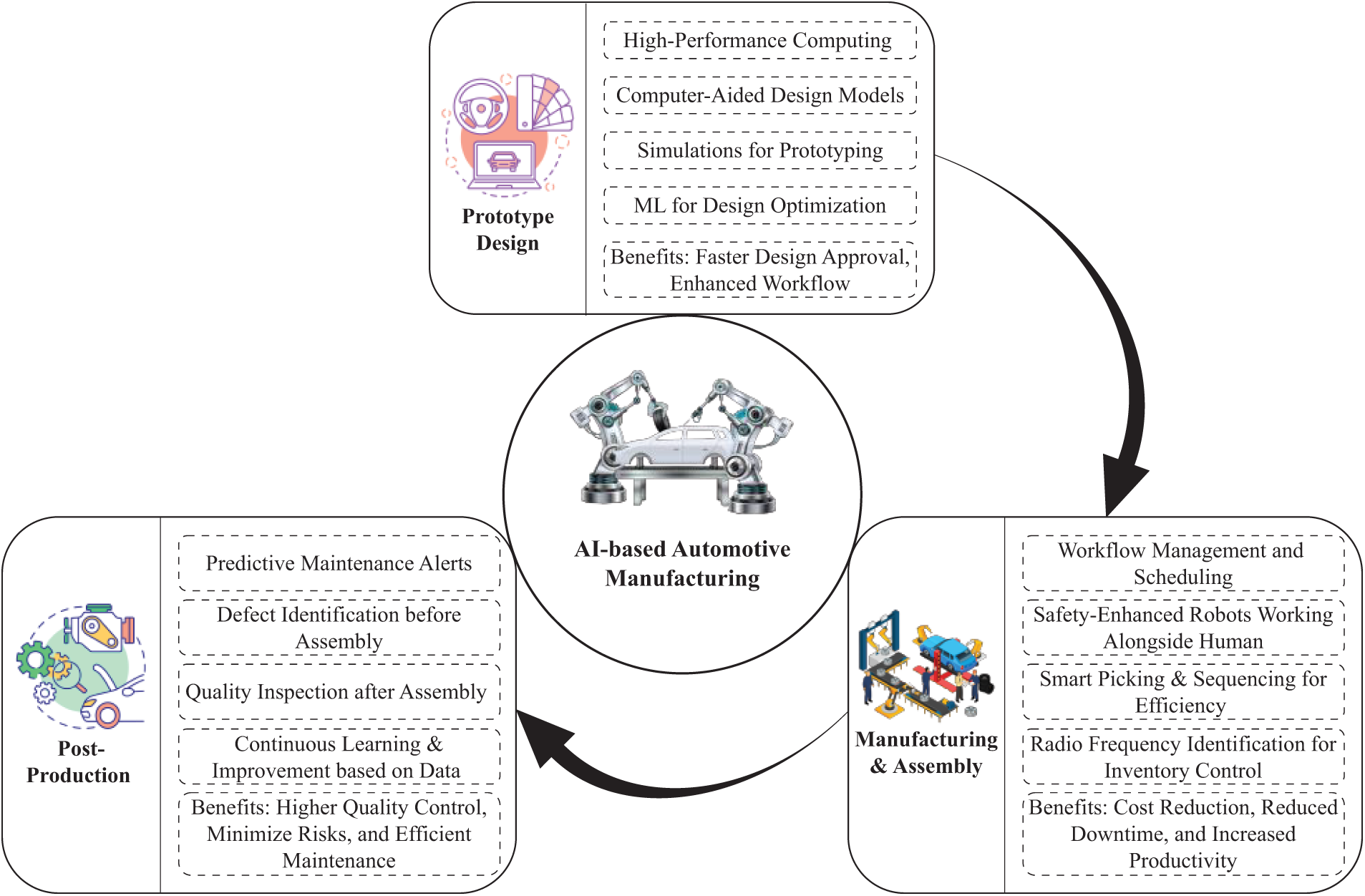

3.3.3 AI in Automotive Manufacturing

The integration of AI in automotive manufacturing spans across design and prototyping, manufacturing and assembly, and post-production systems, offering numerous advantages as illustrated in Fig. 5. For example, General Motors in the USA employed AI to create a prototype for one of their vehicles that evolved a new seat belt bracket that was 40% lighter and 20% stronger than its original design [205]. In addition, to improve the flexibility of manufacturing in the automotive metalworking industry, a low-load universal collaborative robot (cobot) system was proposed with innovative security solutions [206]. AI technologies have significantly enhanced design efficiency, reduced costs, and improved manufacturing quality, making the industry more competitive and sustainable [207]. For instance, using federated learning-AI in decision-making and smart contract policies effectively managed costs, energy, and other control functions in the manufacturing process [208]. Moreover, the automotive AI transformation has radically changed organisational infrastructure and management working methods for better performance, efficiency, and competitiveness. At the same time, leadership styles are also evolving in automotive industries, and AI methods are being used to provide more strategic and analytical solutions within the optimum time frame [209]. Workforce adaptation and ethical considerations are significant impediments, as the shift towards AI-driven processes necessitates new skills and raises concerns about job displacement [207]. Moreover, it is driving innovation and reshaping the industry’s future. There are difficulties in establishing AI technologies at the firm level, emphasising the need for organisational readiness and digital skills [210]. Contradictions also arise regarding the scope of AI’s impact. Some researchers focus on the benefits of AI in autonomous vehicle design and production logistics [211]. In contrast, others stress the unresolved issues in production planning and sequence control [212].

Figure 5: AI deployment in automotive manufacturing

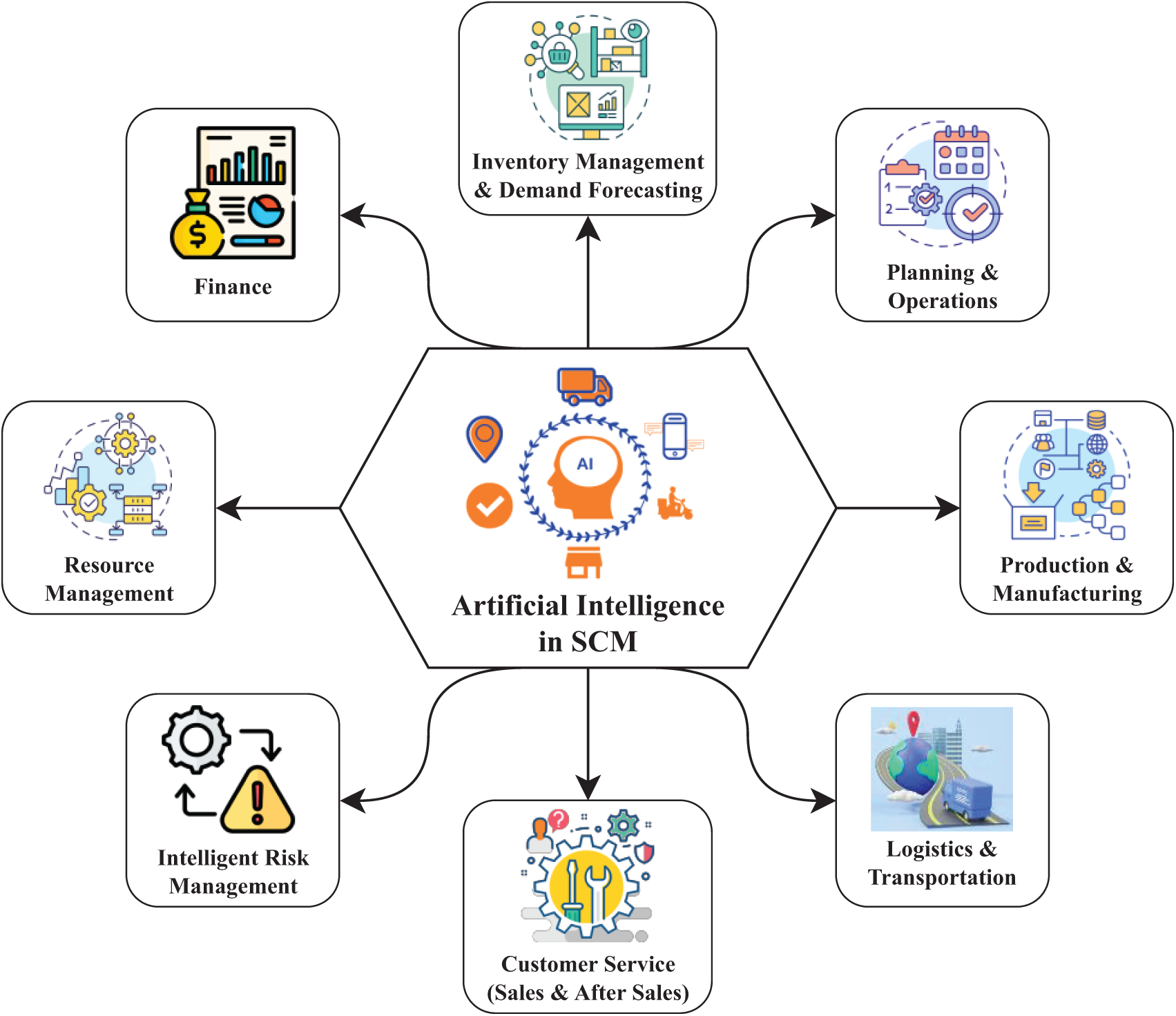

3.3.4 AI in Supply Chain Management

Supply chain management (SCM) is the process of controlling the movements of products and services, which covers all procedures that convert raw materials into finished commodities. Different AI technologies are currently being used in various subfields of automotive SCM for resource utilisation and information sharing among suppliers, manufacturers, and consumers to get the highest efficiency keeping time and money at an optimum level (Fig. 6). As an example, study by Arunmozhi et al. [213] found a 12.48% reduction in energy wastage and an 11.58% reduction in hidden financial transactions in the AV supply chain using the blockchain and AI-based approach. Their framework is expected to improve product traceability, transaction transparency, and sustainable economic growth in AV supply chains. Subsequently, AI-based SCM significantly influences raw material procurement, bridging the gap between raw material suppliers and automobile manufacturers [214]. AI and ML effectively maintain a proper and accurate inventory of automotive parts by analysing large real-time data sets and forecasting supply and demand efficiently to improve product availability and customer satisfaction [215]. AI can optimise inbound logistics in the automotive industry by assessing disruption risks and proposing countermeasures to ensure material availability [216]. AI techniques combined with IoT help track and monitor automotive parts to avoid any unprecedented damage (due to improper handling and by providing insights into materials based on temperature and humidity) and ensure timely arrival at sites [217]. Furthermore, in the production process, AI is able to identify any quality issues of the finished product at an early stage. For instance, Audi implemented a project to improve the testing process in products where ML automatically identified the finest cracks of sheet metal parts within seconds [217]. Meanwhile, Mercedes Benz and Renaults came to realise the benefits of AI in the supply chain as soon as they developed risk mitigation and contingency plans to reduce the probability of production or financial losses where large amounts of data were processed with the help of AI models [205].

Figure 6: Features of AI-driven automotive SCM

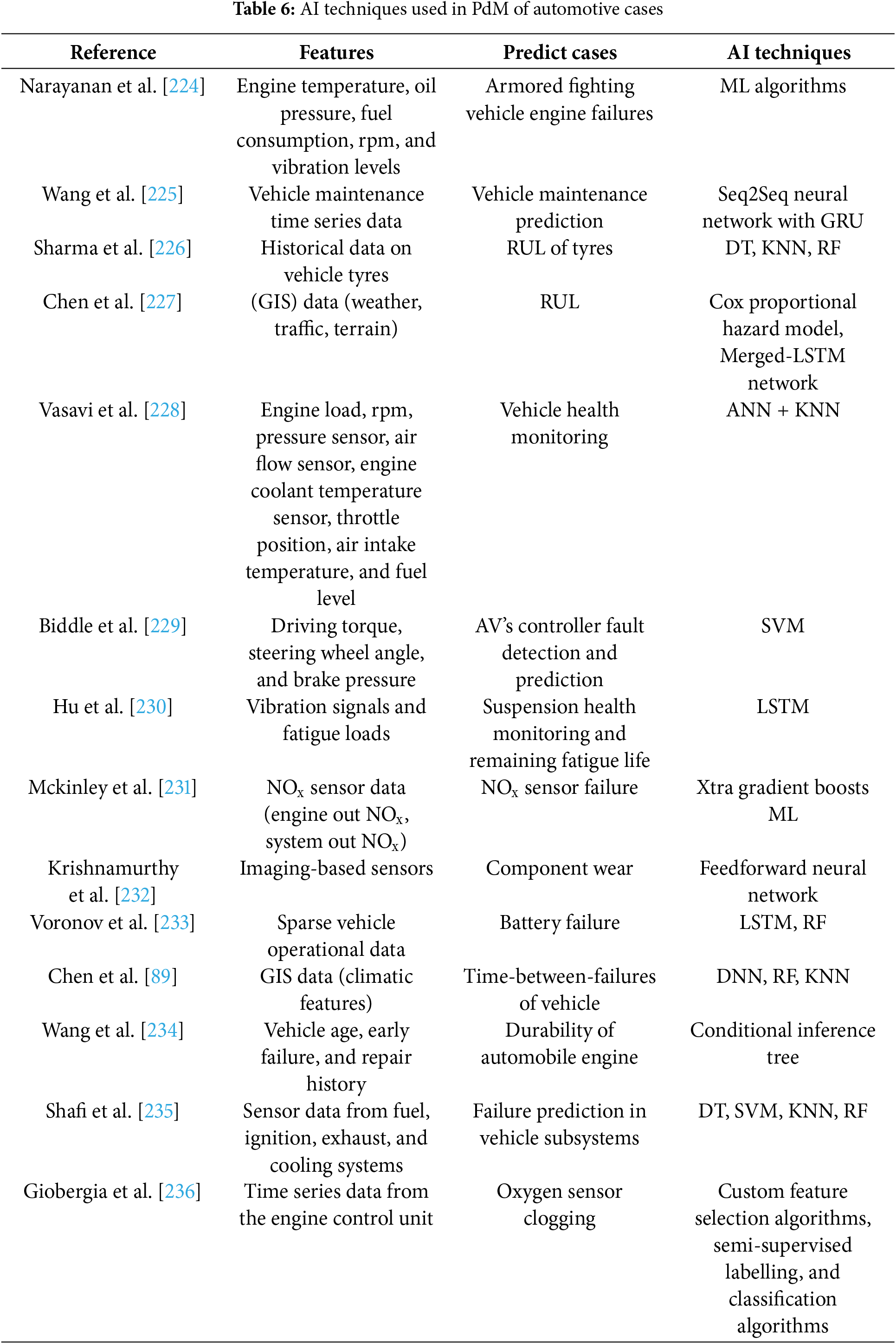

Predictive maintenance intends to predict the time frame of maintenance activities based on the system’s health condition (statistical PdM) and recorded data of the system (condition-based PdM) to avoid costly repair as well as ensure timely repair (before failure). Fault diagnostics and prognosis are important research areas for PdM involving feature extraction, selection, and fault classification. By leveraging advanced sensor technologies and big data analytics, AI techniques can predict potential failures and estimate the remaining useful life (RUL) of automotive components, allowing for timely and precise maintenance actions [218–220]. This proactive approach minimises unexpected breakdowns and extends the lifespan of vehicle parts, contributing to overall operational efficiency [221]. Table 6 shows that most existing research relies on supervised ML methods requiring labelled data. Therefore, combining multiple data sources can improve the accuracy of PdM models [222]. Modern vehicles equipped with sensors provide extensive data about their condition and performance, which can be analysed to avoid vehicle failures by constructing statistical and mathematical models using ML algorithms and executing maintenance activities resulting in models [218]. For instance, Aravind et al. [223] presented a model for AI-based PdM in AVs using physics models, advanced sensors, and reconfigurable devices, aiming to examine electronic components’ deterioration and the relationship between local failures and global system malfunctions. The research presents a proof-of-concept simulation that demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed physics models, data-driven learning strategies, and virtual prototype-aided dynamics learning control schemes in handling different transmission system dynamics and fault phenomena. However, the non-availability of real automotive datasets, usually considered highly confidential by companies, prevents a qualitative comparison of novel approaches with the state of the art. Furthermore, evaluating the validity of developed methods using real data is difficult, as real data is often unlabelled or only partially labelled, and annotating data is time-consuming and requires expert knowledge [218].

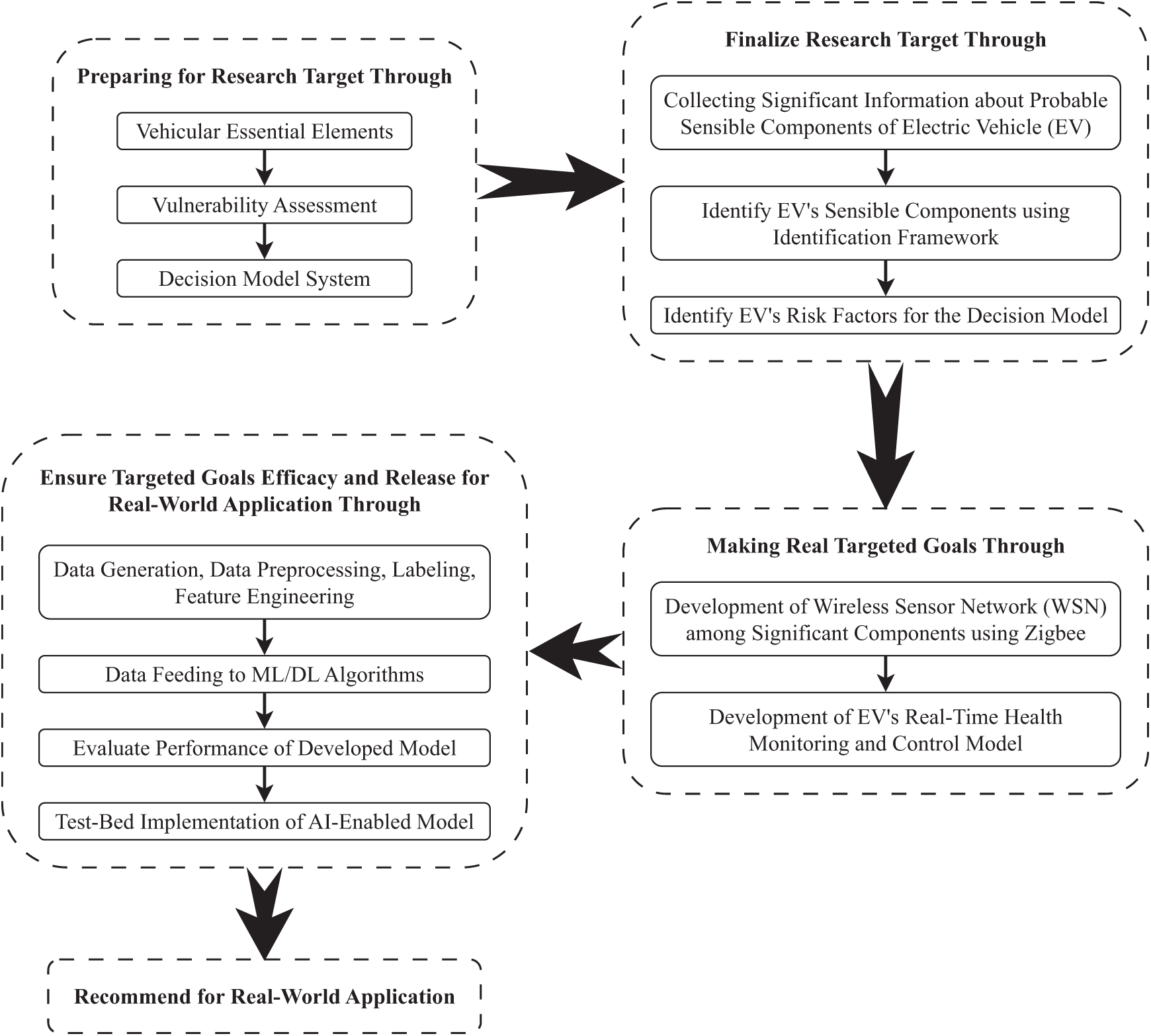

4 Conceptual Framework of AI-Based Electric Vehicle’s Real-Time Health Control Model

The significance of AI in the automotive sector in regulating the degradation of vehicles and their control systems’ valuable parts is growing because of the real-time monitoring of their health and performance. Until today, the available intelligent features in traditional vehicles successfully minimised maintenance expenses, improved durability, reduced unexpected downtime, unexpected accidents, and so forth [237]. However, conventional vehicles are not environmentally friendly due to using fossil fuels to drive them, the emission of excessive greenhouse gasses, and climate deterioration. As a result, the demand for electric vehicles is rising dramatically, and the market analyst predicted that the market will expand to $802.81 billion by 2027 [238]. Again, according to Reuters, vehicle manufacturers commit to ending fossil-fuel vehicles by 2040 with 100% zero-emission vehicles. Based on the discussed matters, it can be inferred that EV demand will explode quickly instead of fossil-fuel-driven vehicles because EV production costs will be cheaper and more flexible than fossil fuel vehicles by 2027, and the fossil fuel vehicles’ overall market could be downed [239,240].

The notable matter is that EVs have many essential components, i.e., complete structure, electric controller, electric motor, tyre, transmission system, and so on, which are greatly responsible for running the vehicle smoothly. Unexpected irregularities of these components may lead to devastating accidents, reduce vehicular longevity, increase operating expenses, waste valuable time, and many other issues may arise [241]. Also, sensible component irregularities may lead to unexpected downtime, irregular spare parts replacement, excessive maintenance expenses, excessive operating expenses, and replacement of expensive spare parts, hindering people’s interest in EVs. Recently, much research has been conducted on EVs as part of their health monitoring system to overcome the abovementioned issues. Still, these researches are confined to specific items of health monitoring systems like tyres [242], batteries, traction motors [243], charging faults [244], predicting the RUL of EVs [245], and so forth. Therefore, in the Industry 4.0 era, the smart and intelligent decision-providing model is a prerequisite to control the degradation of EV’s sensible component by measuring its real-time condition. However, till now, a robust, smart, intelligent, and secure AI-based EV’s real-time health control model system has not been developed using structural data and associated risk factors that could monitor, control, and notify as fast as possible by ensuring reliability and accuracy. Therefore, Fig. 7 presents an AI-based comprehensive model designed to monitor, assess, and manage the health of critical EV components in real time. The process begins with identifying essential components like the battery, motor, and transmission and then assessing their vulnerabilities and associated risk factors. A wireless sensor network is established to continuously gather real-time data from these components, focusing on key indicators like temperature, vibration, and electrical parameters. The collected data undergoes preprocessing and feature engineering to ensure its quality and relevance for predictive analytics. ML and DL algorithms then analyse this data to estimate each component’s RUL and health status, enabling accurate predictions of potential failures. After rigorous model performance evaluations in a controlled test-bed environment, the VHMS framework is implemented in real-world EVs applications, where it continuously monitors component health and provides timely alerts and maintenance recommendations. This smart, intelligent approach minimises unexpected downtime and maintenance costs and supports the Industry 4.0 goal of creating smart, sustainable, and efficient EVs.

Figure 7: Conceptual framework of AI-based health monitoring system for EVs

5 Challenges and Future Scopes of AI in Automotive Sector

As AI technologies evolve, they promise unprecedented advancements in autonomous driving, predictive maintenance, and intelligent transportation systems while presenting complex technological, ethical, and infrastructure challenges. However, successful integration requires addressing critical issues and overcoming many obstacles, as presented in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Overview of AI challenges and future opportunities in automotive

Integrating AI into existing automotive systems presents several practical challenges. One of the primary concerns is ensuring the safety and dependability of AI-based systems, especially in mission-critical applications like real-time embedded systems in vehicles [246]. The integration process must address ethical and legal considerations, data privacy, and liability issues, which are crucial for maintaining trust and compliance with regulations [247]. Additionally, the complexity of AI systems requires robust solutions to handle scalability, real-time data processing, and security vulnerabilities, which are essential for enhancing vehicular networks and communication protocols. The automotive industry also faces challenges related to data availability, quality, and system integration, alongside ethical and regulatory conundrums, particularly as vehicles become more autonomous [248]. Furthermore, the integration of AI in automotive design and manufacturing must consider the impact on employment and the need for international standards to ensure secure AI systems in vehicles [247]. However, following are the detailed practical challenges of introducing AI in automotive sector.

AI integration in AVs fundamentally depends on sophisticated sensor technologies, which serve as the critical sensory interface for perception and decision-making processes. The automotive sector faces substantial challenges in ensuring sensor reliability, performance, and effectiveness, directly impacting the safety and functionality of AI-driven automotive systems. Sensor calibration emerges as a crucial factor in autonomous system performance. Complex multi-sensor fusion techniques require precise alignment for accurate object detection and reliable vehicle operation [249]. In addition, sensor reliability represents another pivotal concern, particularly for IoT sensors in cyber-physical systems. Unreliable sensor data can fundamentally undermine AI applications, necessitating robust methodologies to enhance data quality and consistency [248]. Moreover, the intricate sensor infrastructure in modern vehicles demands sophisticated data management and high-speed networking capabilities to process the vast amount of generated data. This complexity introduces significant challenges across hardware and software domains, with additional complications arising from high energy consumption requirements and the need for rapid data processing [250]. After all, innovative AI applications for the automotive sector are often limited by the sensor technology available. The success of an entire AI model is strongly dependent on the quality of input sensor signals [27]. Hence, resolving these challenges is the first step towards the safe and effective deployment of AVs and other AI surfer automotive applications.

5.1.2 Complexity and Uncertainty

The development of AI systems, especially for autonomous and connected vehicles, relies heavily on the labour-intensive contributions of micro-workers who annotate and process vast amounts of data, highlighting a structural dependency on low-paid labour across global supply chains [251]. Additionally, the increasing complexity of vehicle digital architectures necessitates sophisticated AI models for predictive maintenance, which, while promising enhanced efficiency and cost reduction, also reveal emerging and declining research trends that underscore the dynamic and evolving nature of the field [218,221]. Adopting AI in automotive safety and cybersecurity further complicates the landscape. New attack vectors and sophisticated hacking tools pose significant risks, necessitating the development of explicable AI and robust security measures [252]. The automotive industry’s ongoing digital transformation, driven by AI, IoT, and ML integration, has reshaped business processes and relationships, underscoring the sector’s embrace of innovation and technological advancement. However, this digital overhaul also presents ethical considerations and challenges in workforce adaptation [253]. Thus, the complexity and uncertainty of AI in the automotive sector are characterised by a confluence of technological advancements, labour dynamics, cybersecurity threats, and ethical factors, all of which require careful navigation to harness AI’s full potential.

5.1.3 Complex Model Tuning Issues

Training complex AI models in the automotive industry presents many significant challenges of fine-tuning. The complex and time-variant nature of system parameters in this sector presents substantial challenges to properly defining essential features such as non-linear behaviours, time delays, and parameter drifts to develop effective control and modelling [254]. In addition, deploying AI models in automotive contexts necessitates advanced methodologies surrounding data collection, training, and model deployment. Acquiring high-quality, wide-ranging datasets and building generalisable model architectures robust to varied operating conditions make this process particularly arduous [17]. The integration of AI also increases the complexity of the overall tuning process in terms of machine learning (for example, hyperparameter optimisation). It introduces the need to move rapidly from cloud-based development toward edge-based implementation to achieve adequate model performance at the required reliability rates in real-world situations [255]. Furthermore, advanced feature engineering and anomaly detection methods are needed to support defining AI models for PdM and traffic flow prediction in cooperative and autonomous EVs due to the large amount of data produced by modern automotive systems [218,256]. Multi-objective tuning is more complex since it is dependent on micro-workers for labelling the data, and there is a requirement to continuously update the AI models to cater to the new data and scenes [251].

5.1.4 Cybersecurity and Functional Safety

Incorporating AI and ML in the automotive sector has dramatically increased the attack surface, posing substantial cybersecurity risks. Adopting these technologies promises enhanced user experiences and improved traffic management but also introduces security risks across various automotive systems, including electronic control units, infotainment, and communication networks [257]. The complexity of data and traffic behaviours in AV networks, controlled by protocols like CAN bus, makes them susceptible to various attacks such as spoofing, flooding, and replaying [258]. The increasing connectivity of vehicles exacerbates societal vulnerability to cyberattacks, necessitating robust cybersecurity validation processes and the development of new safety integrity levels [259]. Despite the advancements, the automotive industry faces significant challenges in knowledge sharing and collaboration among manufacturers and suppliers, which is crucial for addressing cybersecurity threats effectively [260]. Current research highlights the predominance of intrusion detection systems in automotive cybersecurity, yet many areas, such as biometric authentication and cryptographic methods, remain underexplored [261]. However, lightweight cryptographic protocols [262], hybrid cryptography engines [263], and hardware security modules [264] are being developed to secure vehicular communications and components. Meanwhile, biometric solutions, including noninvasive sensor authentication [265], and biometric fingerprinting and keystroke dynamics [261], offer promising applications for vehicle security. As standards like ISO/SAE 21434 emphasised, comprehensive cybersecurity testing is critical for identifying and mitigating vulnerabilities, although specific technical guidelines are still lacking [266].

The ethical challenges of AI in the automotive sector are multifaceted and complex, encompassing issues such as human agency, technical robustness, privacy, transparency, fairness, societal well-being, and accountability. AVs present significant ethical dilemmas, particularly in decision-making processes where machine ethics must navigate scenarios involving potential harm to humans [267,268]. The rapid adoption of AI technologies in automotive manufacturing and design has led to substantial improvements in efficiency and quality. Still, it also raises ethical concerns related to workforce displacement and the need for equitable adaptation strategies [269]. Moreover, deploying AVs necessitates robust data governance frameworks to protect user privacy and ensure transparency in AI decision-making processes [267,270]. Despite ongoing efforts by academia, policymakers, and industry stakeholders to address these ethical issues, a consistent and comprehensive solution remains elusive, highlighting the need for continued collaboration and innovation to develop ethical guidelines that can keep pace with technological advancements [268,270].

5.2.1 Autonomous Driving and Intelligent Vehicles

One critical focus is enhancing deep learning techniques to improve autonomous driving systems’ reliability and real-time performance, particularly in complex scenarios involving road, lane, vehicle, pedestrian, and traffic sign detection [271,272]. Additionally, integrating AI with other emerging technologies such as high-definition maps, big data, high-performance computing, augmented reality, virtual reality, and 5G communication will be essential for achieving full automation and improving the decision-making capabilities of AVs [273,274]. The concept of hybrid human AI also presents a promising avenue, combining human judgment with AI to overcome current limitations and enhance the safety and efficiency of semi-autonomous systems [133]. Furthermore, addressing the challenges of cybersecurity, vehicle-to-everything privacy, and risk mitigation technologies will be crucial for the safe deployment of intelligent vehicles [274]. Finally, the development of innovative AI algorithms and hardware architectures tailored for autonomous driving will be necessary to handle the increasing complexity and ensure the robustness of these systems [275].