Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

How Software Engineering Transforms Organizations: An Open and Qualitative Study on the Organizational Objectives and Motivations in Agile Transformations

Department of Informatic Systems, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, 28031, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Borja Bordel Sánchez. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81(2), 2935-2966. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.056990

Received 04 August 2024; Accepted 15 October 2024; Issue published 18 November 2024

Abstract

Agile Transformations are challenging processes for organizations that look to extend the benefits of Agile philosophy and methods beyond software engineering. Despite the impact of these transformations on organizations, they have not been extensively studied in academia. We conducted a study grounded in workshops and interviews with 99 participants from 30 organizations, including organizations undergoing transformations (“final organizations”) and companies supporting these processes (“consultants”). The study aims to understand the motivations, objectives, and factors driving and challenging these transformations. Over 700 responses were collected to the question and categorized into 32 objectives. The findings show that organizations primarily aim to achieve customer centricity and adaptability, both with 8% of the mentions. Other primary important objectives, with above 4% of mentions, include alignment of goals, lean delivery, sustainable processes, and a flatter, more team-based organizational structure. We also detect discrepancies in perspectives between the objectives identified by the two kinds of organizations and the existing agile literature and models. This misalignment highlights the need for practitioners to understand with the practical realities the organizations face.Keywords

Agility [1] was born in the discipline of software to improve the work of small teams that develop software [2] by applying ideas from the manufacturing industry [3]. Originally, Agile encompassed a broad spectrum of approaches to software development. These methods, such as Scrum, Extreme Programming (XP), or Dynamic Systems Development Method (DSDM), share a core set of principles, such as iterative development, customer collaboration, or acceptance of change [4].

Organizations soon realized that the benefits of Agile could be extended to the entire organization [5]. This extension is commonly known as Business Agility, Enterprise Agility, or Organizational Agility, and it is envisioned as an ideal state for organizations in which they can adapt in an agile and sustainable way to a rapidly changing environment [6], making it possible to thriving and not just surviving on a context of volatility and accelerated change [7]. Organizations developed the so-called Agile Transformations to reach this Business Agility state [8]. Agile Transformations are a “high priority for a rapidly increasing number of organizations” [9] and companies are investing in them to achieve Business Agility. However, these processes are complex, and companies lack reference roadmaps, guides, and even a common language to successfully achieve their goals. This is especially true because Agile Transformations are comprehensive processes that impact every aspect of the organization, including people, processes, strategy, structure, or technology [4,10]. These are complex and profound changes in organizations, which go far beyond its origin as a tool for software development.

Despite the great impact of these Agile Transformations, there is little academic knowledge about their development and impact, as will be shown later in the analysis of the available literature. This gap is filled by the work of industry practitioners, usually based on experiences limited to specific frameworks or individual companies [11]. On the other hand, a substantial corpus of “gray literature”, which is to say, non-academic material, has been produced primarily by practitioners. This comprises a plethora of journal articles, corporate websites, and a large number of books. This category of content, at least in theory, reflects the vision of practitioners based on their own experience. Consequently, it can serve as a valuable lens through which to comprehend the objectives that organizations set for themselves when embarking on an Agile Transformation.

One way to understand Agile Transformations is to examine what the organizations are trying to achieve, or, in other words, what characteristics the organizations expect to have after the transformation. To understand Agile Transformations, we must also consider the factors that facilitate or impede the process. In this way, by reducing the impact of blockers and increasing the impact of enablers, organizations should expect to achieve the objectives they have set as a result of the transformation. Unfortunately, as we have said, there are not many comprehensive studies on Agile Transformations and their impact. For this reason, the purpose of this paper is to help fill the gap in the literature on Agile Transformations. In this case, by examining the motivations, organizations have to launch these processes in the form of the objectives they define for their transformations.

When we study Agile Transformations, we discover that there are two types of organizations involved. Agile transformations involve two types of organizations: final organizations that develop the process internally and consultants who help other organizations implement it. In recent years, the number of consultants has grown significantly to meet the needs of final organizations. For this reason, the vision of both needs to be aligned for the transformation processes to be effective and successful, helping to translate software engineering concepts into the design and operation of organizations.

As stated above, Agile was born within the world of software development. Business Agility helps organizations overcome the barriers that prevent them from fully benefiting from Agile software development frameworks. Additionally, our experience, which aligns with that of numerous practitioners, indicates that the implementation of Agile within organizations typically commences in the IT or systems domains. However, we believe that the objectives of organizations have a greater scope and impact: software engineering has the potential to transform organizations.

Although the academic literature is very limited on this topic, the “gray literature” is very abundant, and we believe that gathering the experience of practitioners will provide a realistic insight into the vision of organizations involved in Agile Transformations. Our research aims to bridge the gap in the academic literature on Agile Transformations by focusing on the perspectives of organizations directly involved. Our objective is to address the current gap in the academic literature by conducting fieldwork with a variety of practitioners. The research objectives are the following:

• Developing an experimental study that makes it possible to know the impact of Agile Transformations.

• Understand the motivations of the organizations involved in these transformations and where they place the focus of change.

• Identify the factors that most facilitate or inhibit these transformations from the practitioner’s perspective.

Three Research Questions are derived from the above:

RQ1: Do Agile Transformations have a true impact on the organization as a whole (if so, what are the limitations) or are they primarily focused on improving aspects related to software development?

RQ2: Does the vision of practitioners in the “gray literature” reflect the transformation objectives of organizations?

RQ3: Is there a difference between the vision of companies and consultants?

The paper is structured as follows: first, an introduction (this section) presenting the problem and the paper; then Section 2 (“Related work”) reviews the available literature on Agile Transformations and the goals that companies set for them; Section 3 (“Methodology”) describes how the participants were selected and how the data used later in the study were collected; Section 4 (“Results”) contains the result of the analysis carried out based on the information obtained from the participants; Section 5 (“Conclusions and next steps”) summarizes the main findings of the study and the next steps to be taken in the study. Finally, an appendix contains the complete list of definitions of the characteristics of an agile organization distilled in our study.

Our first step was a literature review, a method that can help identify previous work to summarize existing knowledge on the topic and to identify gaps in current studies that can be covered with this paper. The review was based on a simplified version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. These guidelines are designed to ensure transparency and rigor in bibliometric research across disciplines, and they are widely recognized for their effectiveness. The simplification was essentially to use a shorter checklist of criteria in the review than the standard 27 items.

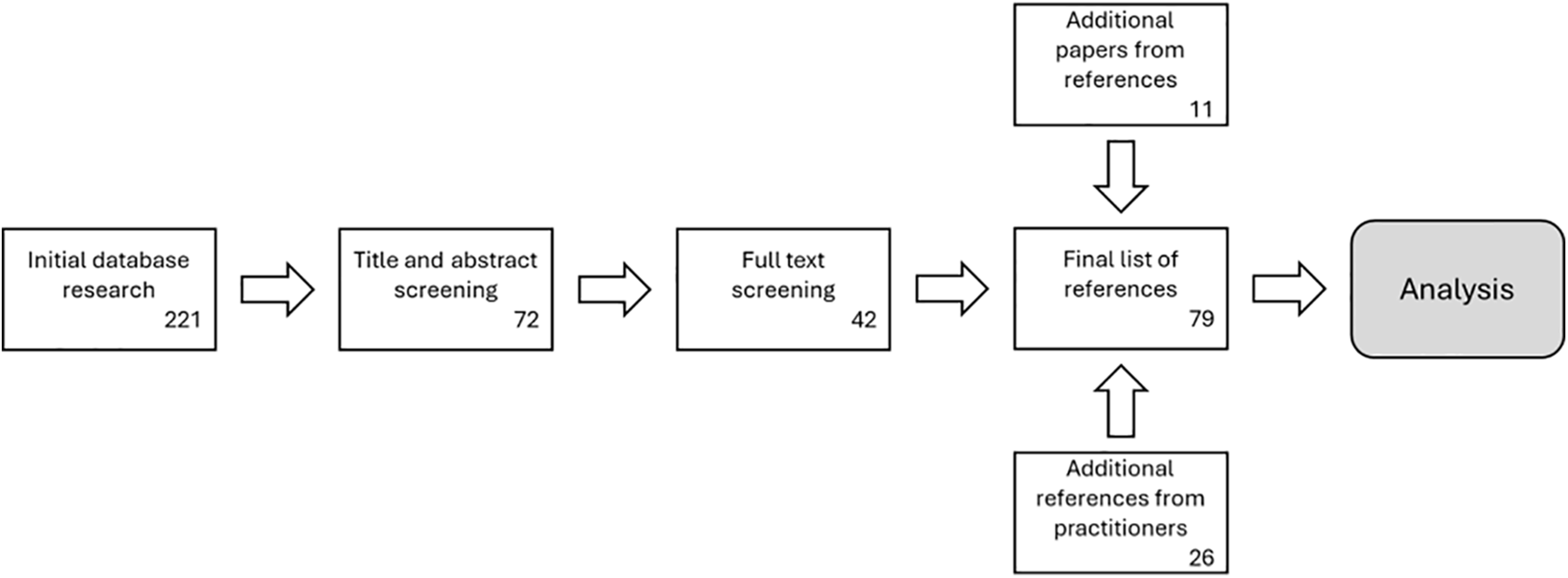

Fig. 1 shows the steps followed in this phase:

Figure 1: Process of analyzing related work

We initiated the search for related academic literature using Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The following terms were used as queries: “business agility”, “organizational agility”, “enterprise agility”, “agile transformation”, “adaptive organizations”, “agile”, “agility”, and “agile at scale”. We performed a keyword, title, and abstract search, looking for articles related to Business or Enterprise Agility and especially Agile Transformations. Since the total number of references identified was very high (on the order of tens of thousands), an adjustment of the search terms was made: for example, “business agility” is used in fields far removed from our study (such as economics or business management). Therefore, the initial list of terms used in the search was refined by eliminating overly general terms and including more precise terms such as “Business Agility Agile Transformation”. This resulted in a final list of 221 references.

After the title and abstract screening, 72 papers were selected. All papers not relevant to the topic were excluded. After full-text screening and reviewing the references of the selected papers, a total of 42 papers remained. From these papers, most of them are about transformations in a single organization [6,11,13], about the deployment of an Agile framework [14–16], specific aspects of transformations (like leadership [17], or the impact in Digital Transformations [18]) or literature reviews [8,19]. Few have covered the topic of Agile Transformation among multiple organizations, and none of them have a general open perspective. In addition to academic papers, we have incorporated several books and articles by practitioners (14 books and 12 articles and websites), in order to have a broader view of the issue, although peer-review papers are more relevant to our work. Table 1 summarizes this process.

The most common way to collect information is through surveys. Interviews and observations are also frequently mentioned. In the first two cases, the starting point is predefined questionnaires, which make it possible to work with large samples of hundreds or even thousands of responses, but limit the topics covered to those previously defined. Observation requires a lot of time and resources to carry out and focuses more on behaviors than on the vision or objectives of the participants.

The information offered by the materials analyzed in Agile Transformations focuses mainly on the factors that make them possible. However, there are also visions and definitions of Business Agility that can serve as a precedent for understanding the objectives of transforming organizations. For example, it is common to mention adaptability, or “an organization’s ability not only to sense, but to respond swiftly and flexibly to technical changes, new business opportunities, and unexpected environmental changes” [20]. It can also be the “ability to respond rapidly, proactively, and intentionally to an unexpected changing demand” [21], or the “ability to cope with rapid, relentless, and uncertain changes and thrive in a competitive environment of continually and unpredictably changing opportunities” [22].

In general, it is common to mention the ability to adapt in order to make the organization sustainable over time. Beyond adaptability, other objectives and benefits of Agile Transformation are mentioned, such as continuous learning and customer-driven and value-driven [23]; improvements in organizational performance with respect to business management [18]; continuous growth [24]; or generating competitive advantages [17]. As can be seen, all of them can be interpreted as objectives with an impact that goes beyond the technical areas related to software development, which is in line with our first hypothesis. Unfortunately, it is not possible to know what would be a complete list of objectives and benefits of Agile Transformation, and what position in importance each of them occupies for organizations.

A similar situation arises when we examine materials prepared by practitioners. For example, SAFe, a well-known and widely applied scaling framework, lists several benefits [25] derived from agile transformation, including engagement, faster time-to-market, increased productivity, and improved quality. However, this list is derived from the generalization of a series of customer stories, which, while interesting as individual accounts, are hardly generalizable or a source for a proper industry overview.

Another reference source in the industry is the “State of Agile Report”, the result of a survey that reached its 17th edition in 2024 [26]. In its “What Drives Agile Adoption” section, the most frequently mentioned answers are “Prioritize, deliver, and measure incremental customization and business value”, “Accelerate time to market”, and “Digital transformation”. Interestingly, when asked about the benefits observed in successful transformations, the list changes. The study revealed that the most commonly cited benefits of Agile adoption were increased collaboration, better alignment with business needs, and a more positive work environment. This study was based on a survey of more than 800 anonymous and volunteer participants and, like other similar studies, was based on the selection of a predefined list of responses. As a result, the veracity of the responses and their origin cannot be rigorously controlled. We will develop the content of this report in more detail below, compared to the findings of our work.

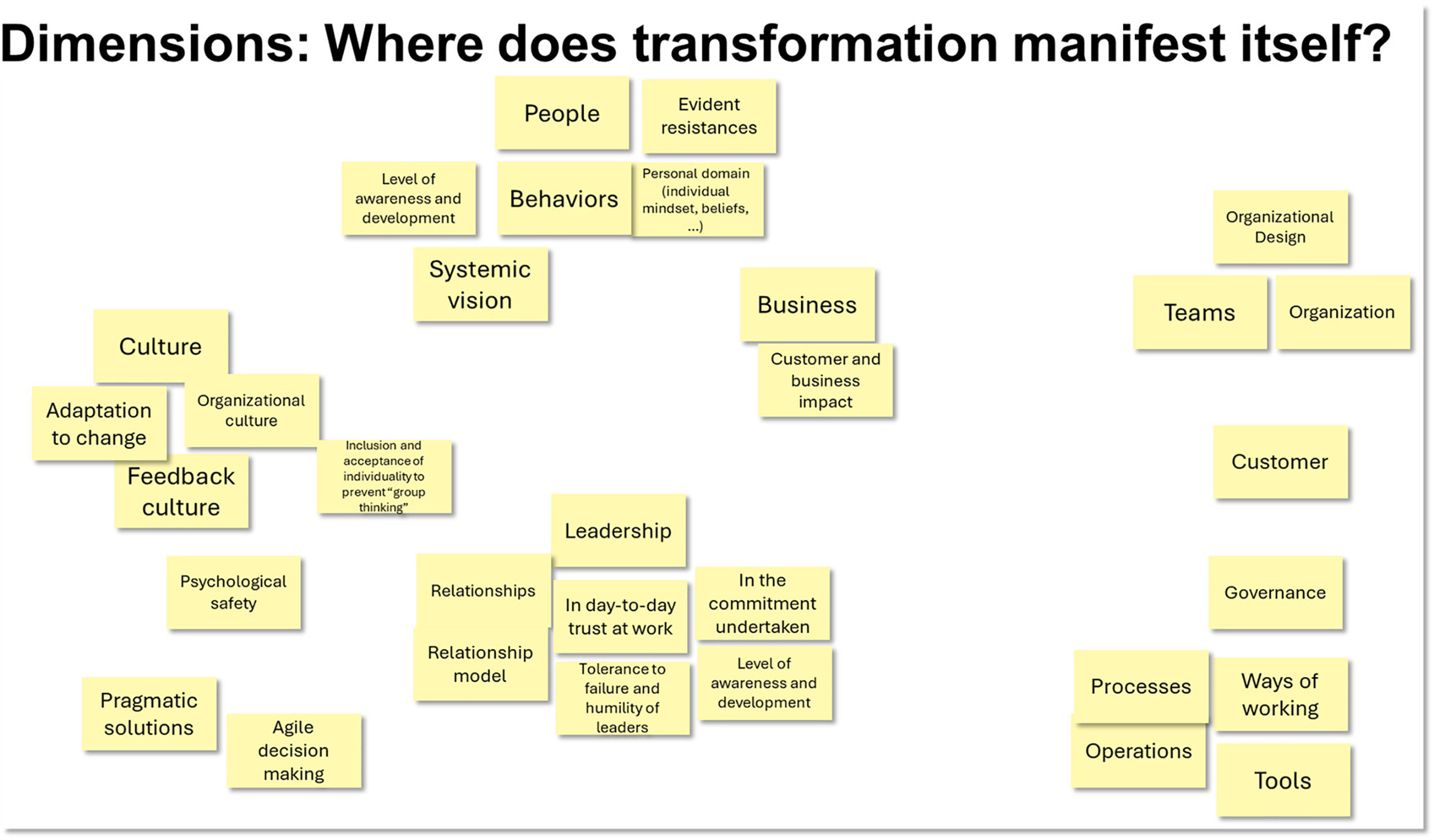

Finally, other interesting sources for our study include books in which authors describe their business agility models [5,27–30], articles [6,31,32], and specific websites of organizations that have developed their own models [33–37], all of which are part of the so-called “grey literature”. In the case of these sources, there are usually no lists of goals or characteristics as such, but they all have in common the enumeration of dimensions in their Business Agility models. These dimensions are aspects of the organization where the focus of the transformation should be placed so that the impact of the change can be seen. The number and nature of the dimensions vary widely (from 3 to 18), and their analysis is the subject of another paper by the authors, but we can list the most frequently mentioned dimensions, which we can translate as priority aspects to observe the impact of change.

Specifically, as part of this study, we thoroughly analyzed 15 models from different sources. Unfortunately, there is no reference model or total agreement among the models analyzed: this confirms the lack of a common reference framework for Agile Transformations. In addition, during the workshops and interviews, we came into contact with other models, generally specific to each organization. Since they are not published (and in many cases protected by confidentiality), we cannot refer to them, but we can confirm that the vision they offer is similar to that of the models of the authors of non-academic publications.

The most frequently mentioned are those related to leadership style, organizational structure (both in 13 and 15), and how processes are defined (12). These are followed by cultural issues, people management, process definition (11 models), strategy development and implementation (10), and finally, issues related to value definition and delivery (6), and technology (9). A common element in all of these models is the important role given to the customer, who is placed at the center of the organization’s activities (specific dimension in 7, center of the model in almost all).

In summary, the academic literature offers studies that are generally focused on specific frameworks or companies and are almost always based on structured surveys with predefined responses. Non-academic works generally lack data and evidence and also often rely on surveys. We believe that, for these reasons, our study represents a significant contribution to the existing literature by collecting the qualitative view, neither predefined nor conditioned, of a sufficiently representative set of industry agents.

As stated in the previous work section, surveys are a common methodology when working with multiple organizations. On the contrary, when studying a single organization, interviews are more frequently used, with observation sometimes utilized as a supplementary technique. In our study, we give participants as much autonomy as possible in order to obtain a more qualitative than quantitative perspective. Consequently, we employed workshops when there were multiple participants and interviews when only one individual represented the organization. This approach has enabled us to gather a greater volume of data, although at the cost of requiring a greater effort to analyze and synthesize the information.

A survey was conducted with 30 organizations to understand their vision. Although participation was voluntary, a diverse sample was obtained from organizations of different sizes and sectors. To find potential participants, the authors used several approaches: presentation and recruitment at specialized conferences (such as CAS or ‘Conferencia Agile Spain’, where several participants were identified after the presentation of papers); professional social networks, especially Linkedin, where articles publicize the study that allowed the recruitment of several participants; and their own agenda of contacts in organizations. All participants have received compensation for their cooperation in the form of reports with the preliminary conclusions of the study, especially personalized for them.

Finally, the participation of 30 organizations has been achieved represented by 99 people, with these characteristics:

• 16 of the organizations are companies carrying out transformation processes (the so-called “final organizations”) and another 14 are companies helping the former in these processes (“consultants”).

• The final organizations have more than 235,000 employees, although they range in size from 60 to more than 100,000. The transformation processes of the sum of these organizations have so far impacted more than 60,000 people.

• Consulting firms are comparatively smaller. Some freelancers are even included because they are well-known and respected people in the Spanish Agile community. In total, the 14 companies employ about 400 people.

• 99 people participated in workshops and interviews on behalf of the organizations: 68 men and 31 women.

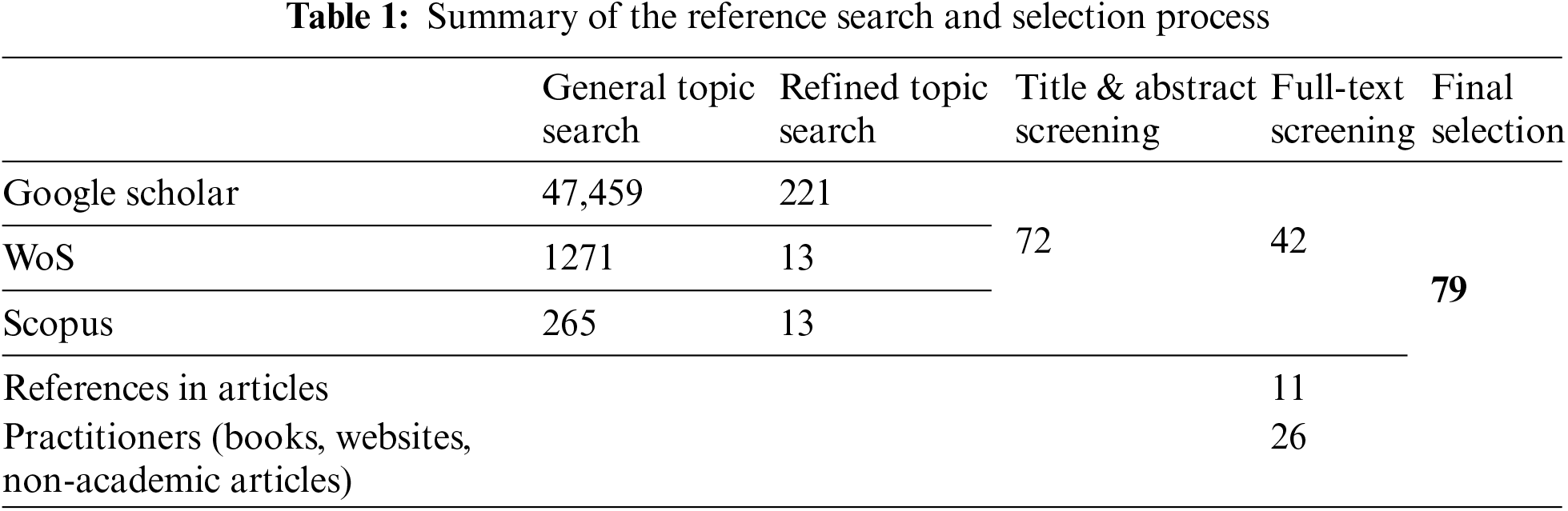

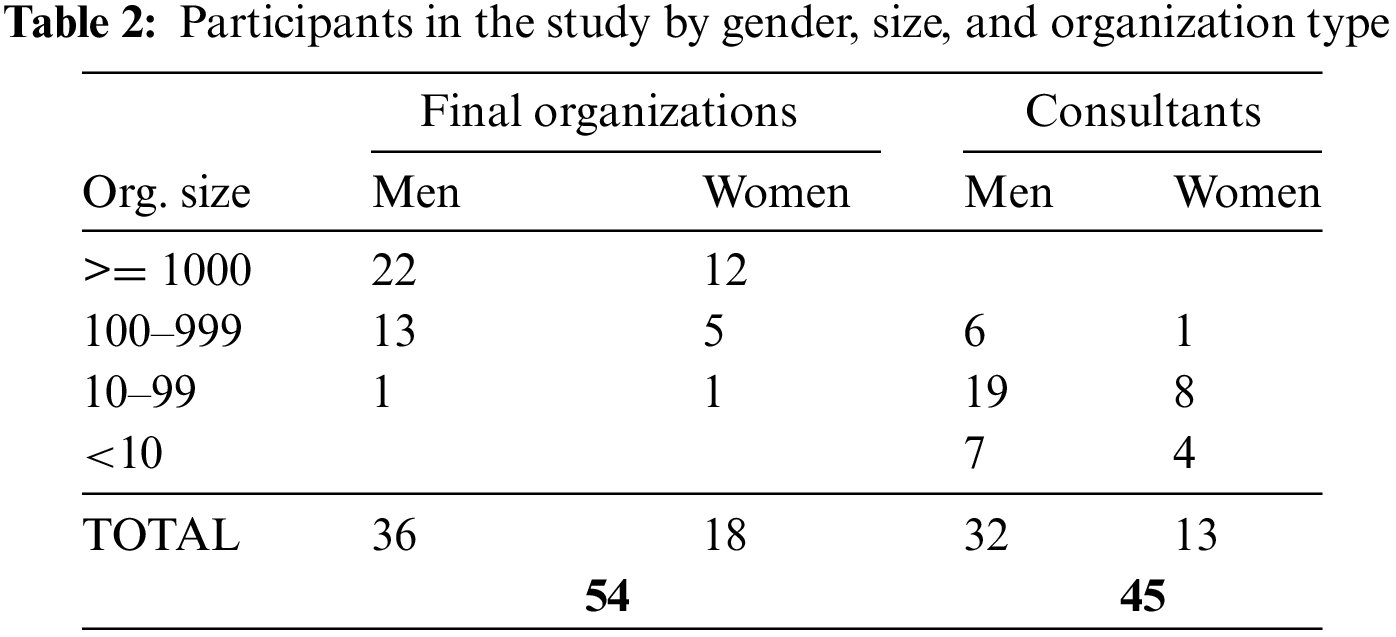

This information is summarized in the following tables. Table 2 shows the number of people who participated in the study, categorized by gender, size, and type of organization. Table 3 shows the number of organizations and their respective employees, classified by type and size of company. In addition, the number of individuals a by the transformation process at the time of the study is provided for the final organizations (those undergoing their own transformation). Additionally, the total number of individuals potentially affected is indicated. Please note that the total numbers have been rounded off, as the amounts provided were approximate and not exact.

The data collection process followed this scheme:

• Once the date, time, and attendees were confirmed, reference documentation was sent to provide context to the participants, as well as access to the virtual dashboard (Miro) used to collect the information.

• Data collection methods include semi-structured interviews (when only one person was in attendance), face-to-face workshops, and virtual workshops, which were the most common methods.

• The sessions lasted between 1.5 and 3 h, depending on the number of participants (up to 9 in the largest workshop). The virtual boards were available for participants to review and modify their answers, if necessary, after the sessions.

• All information was collected on a digital whiteboard (Miro), like the example in Fig. 2, regardless of whether it was an interview, a face-to-face workshop, or a remote workshop. In almost all sessions, the content of the whiteboard was entered directly by the participants, although in some cases the authors were responsible for transcribing the participants’ responses seeking maximum fidelity.

• Since it was clear from the first meetings that it would not be possible to record the sessions due to confidentiality issues (several NDAs were also signed), the boards were supplemented with notes taken by the facilitators during the sessions.

Figure 2: Examples of a board used to collect data (workshops and interviews were held originally in Spanish)

The sessions collected three types of information: what are the objectives of an Agile Transformation (or what would be the expected characteristics of an agile organization); where the focus of the transformation is placed; and what factors enhance or inhibit the transformation processes. In this paper, we focus only on the first point. The analysis of answers to the other questions is the basis for further work.

During the interviews and workshops, and in relation to the first point, the one analyzed in this paper, the process was as follows: the participants were asked the question “What are the objectives of an Agile Transformation?” (all sessions were held in Spanish). As on certain occasions, it was difficult for the participants to answer this question, it was complemented with “What are the characteristics of an agile organization?” on the understanding that this type of process seeks to achieve the state of Business Agility, which would make the organization exhibit the characteristics of an agile organization. The participants freely responded with no limit on the number of responses, which were recorded in the form of sticky notes on the virtual board (see Fig. 2). No limit was established because it was considered particularly interesting to obtain the greatest possible diversity in the responses. As a result, if the number of notes reached a certain amount (the order of tens, several dozens) a clustering of topics was done in agreement with the participants to create groups of similar or related concepts.

The next step was a vote by the participants to indicate the most relevant and important characteristics among those recorded and grouped on the panel. In this way, a selection could be made and transferred to another panel. At this point, the participants were asked to indicate the most appropriate metric for the selected characteristics. This led to reflection and a deeper understanding of their definition and meaning.

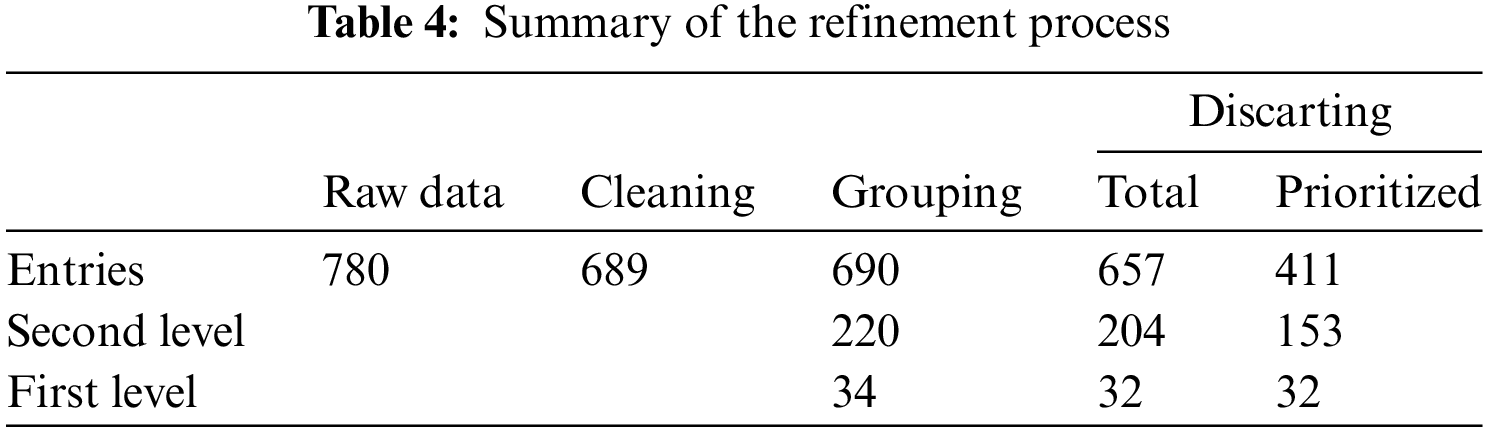

Once the 30 workshops and interviews were completed, we proceeded to analyze the data collected according to the following process (summary in Table 4):

• Extraction and standardization: The data was cataloged (type and identity of the source organization) and supplemented with additional information from the facilitators’ notes. After this process, there were 738 records.

• Cleaning: duplicate data that referred to questions outside of the study, or without context or explanation were eliminated. On the other hand, some data were split into multiple entries because participants had left multiple answers on the same note. The final result consisted of 690 entries.

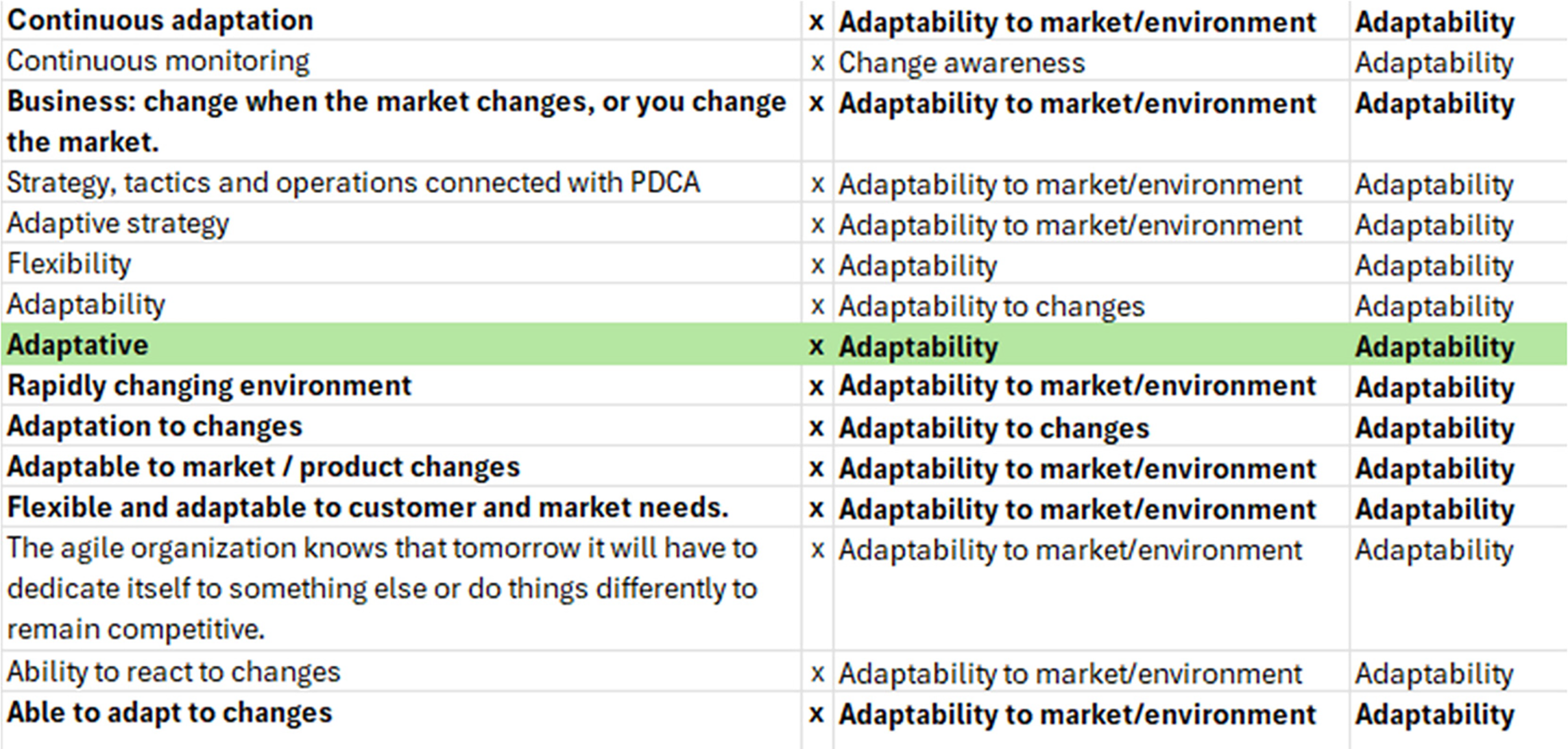

• Refinement: From then on, a process began to find related terms and create categories to group them together. In some cases, this was very simple, since certain terms were often repeated (“transparency”) or several terms expressed very similar ideas (“adaptability”, “adapt”, “adapting organization”), but in most cases, it was necessary to carry out successive refinement processes.

• Groupings: After three rounds of refinement, a total of 220 term groupings remained, still a very unwieldy number. These second-level groupings were simplified to a much more manageable 34 first-level groupings, which are the synthesized characteristics finally used. To make the information more manageable, a logical grouping of 10 dimensions developed by the authors was used, although the real characteristics are those we have called first-level characteristics.

For the analysis we were inspired by a Ground Theory or GT approach, which provides a systematic methodology for inductively developing a theory based on data analysis [38]. GT is particularly effective when there is no clear hypothesis or research problem at the outset.

Fig. 3 shows an example of refinement from raw data to the intermediate category, to one of the 34 topics (the raw data were originally in Spanish because it was the language of workshops and interviews, here we show a translation):

Figure 3: Example of refinement of data

To determine the truly important characteristics according to the criteria of the study participants, the items voted on and selected were separated from the others. Of the 690 items used in the process, 422 belong to the items voted on and selected by the participants.

Of the 34 groups of topics, two have been eliminated for the following reasons:

• What we have called ‘transformation outcomes’, refer to certain general characteristics of the organization, especially in relation to the context in which it operates. Although these are important for any organization, they cannot be said to be characteristics of agile organizations per se. It is a small percentage of the responses (2.44% of the total) and it has to do with the organization achieving better business results, improving its productivity and competitiveness, ensuring its continuity, becoming a benchmark in the market, and even the need for digital transformation.

• The second group relates to the transformation process itself, rather than the characteristics of the agile organization. The answers in this section relate to: avoiding purely cosmetic transformations, and that transformation processes are not projects in the sense that they don’t have a defined beginning and end (if the Agile Transformation is intended to make an organization more adaptable and responsive to change, it will be necessary to continue this process unless the environment becomes static and does not change, which is rarely the case).

After excluding these two categories, the total number of participant responses considered in the study is 657, organized into 32 characteristics or input groups. If we consider only those items that the study participants selected as relevant, the total number is 411. Fig. 4 shows the progressive refinement of data.

Figure 4: Refinement and selection process

In determining which features are most relevant and to what extent, we considered several alternatives:

• Count the mentions without prioritizing. That is, count the number of times that there are responses that can be assimilated to the different characteristics that appear in the first response (without prioritizing) of the participants.

• Prioritized mentions. As part of the exercise, participants were asked to select (directly in the case of an interview; by consensus among participants in workshops, or, more often, by voting) which characteristics were most important. This selection is a way of signaling the greater importance of a subset of characteristics.

• Raw number of mentions. That is, each mention is counted individually so that if a characteristic appears more than once in an organization’s response, each mention is counted separately.

• Count one mention per organization. In other words, if there are multiple responses from the same organization that fit, for example, the “safe space” characteristic, it is counted as a single mention. This avoids the distorting effect of multiple responses, which is more common in workshops with a larger number of participants than in interviews.

• Weighted value. This involves assigning a variable weight to each response based on the number of entries from each participating organization. The idea is to assign the same value to each participating organization and divide it by the number of responses to obtain a weight per response. An organization with 4 responses would have a weight of 0.25 each, whereas another organization with 50 responses would have a weight of 0.02 each. This is a way to reduce the imbalance that a high number of responses (more common in workshops with many participants) would introduce into the final result.

Finally, we decided to take only the prioritized responses, as they are the result of an evaluation and selection process by each organization. In addition to that, a weighting system was used to correct the difference between workshops and interviews with few participants, and therefore, fewer contributions, and workshops with many participants and many more contributions. In this way, the aim is to balance the vision of the different organizations and to avoid the fact that a higher participation in the workshops would give more relevance to their answers. See Fig. 5 for a summary of the process.

Figure 5: Refinement process of topics

4.1 Vision of Business Agility

Our RQ1 asked what organizations are trying to achieve by undertaking Agile Transformations, especially if they are trying to have a broader impact than just improving processes related to software development. The ordered list of synthesized characteristics is the answer to this question.

Table 5 shows all 32 groups of characteristics according to three classification criteria: sum of all mentions, only those marked as relevant by the participants, and weighted ranking, which is the criterion ultimately applied. It can be seen that although there are differences, they are not significantly large (see Appendix A of this document for a comprehensive definition of each of these characteristics). When considering only the top 10 most voted items in each list, there are 8 common characteristics in the overall list and 9 in the list of relevant items without weighting.

However, there are some notable deviations. For instance, ‘Learning organization’ drops from third to sixth place when we consider only the most relevant characteristics and falls to thirteenth in the weighted list. This is the most significant difference, as in the other cases there are usually no major deviations. Certain characteristics may be frequently mentioned in the literature and industry, but may not be the most relevant to organizations. This hypothesis has not been tested.

If we stay only with the most relevant weighted responses and look at the 10 most mentioned characteristics (which accounted for 59.6% of the responses), an agile organization can be defined within the lines of the following statement:

Above all, the organization should focus on the customer and be adaptable. A place where there is an alignment of goals and objectives, that delivers value in a lean way (efficient, no waste, with quality), and that generates a sustainable process. It functions as a living organism, is team-based, and is flat (or flatter than today’s). A value-oriented organization where decisions are made in a decentralized and fluid way.

If we add other characteristics to reach 80% of the participants’ responses (the first 16 entries in the list), they have an adaptive culture and an orientation towards communication and learning. It is an organization where people are motivated and special attention is paid to improving their employee experience. Finally, it is an organization with a culture of continuous improvement.

Of these, which are directly related to software engineering and which have a broader scope? The truth is that there are few that can be clearly attributed to the software world. Perhaps “lean delivery” or “team-based organization”, but both have more global components: “delivery” includes any type of product or service and covers all types of activities (ideation, support, marketing); and structuring the organization based on teams, which is the complement of “organization as a living organism”, covers any area of the organization, not just technical departments. On the contrary, in very prominent places in the list, there are global characteristics of an organization that affect its overall functioning and management. “Customer centricity” is a philosophy that is not limited to the construction of technological products (as can be seen in the definitions in Appendix A). “Adaptability”, “alignment”, “fluid, decentralized decision-making”, “communication”, or “learning organization” are all global characteristics that affect all areas and departments of the company.

As we can see, the impact that organizations expect from an Agile Transformation is global. Agile Transformation, although born in the domain of software engineering and able to overcome its limitations, implies the transformation of the entire organization. Therefore, we can conclude that the answer to our RQ1 is: Yes, Agile Transformations have a global impact on the entire organization, not just as a way to improve software development or technical or system areas.

4.2 Characteristics of Agile Organizations

Below is a simplified list of the 10 characteristics most frequently mentioned by participants in the study. The complete list of the 32 characteristics (transformation objectives) can be found in Appendix A:

• Adaptability. It is defined as the ability to detect and even anticipate changes in the context and environment of the organization and from there apply mechanisms to generate adaptations, if possible, quickly, to respond to these changes and to help improve the organization’s resilience.

• Alignment. This involves creating and sharing the same vision, aligning culture and strategy, and ensuring that the organization’s teams and individuals feel involved.

• Customer centricity. This characteristic involves putting the customers at the center of decisions, satisfying their needs, being in close proximity to them, generating feedback loops to better understand the impact of products and services, maintaining constant and direct contact, and understanding and listening to the ‘Voice of the Customer’.

• Flat organization. According to the participants, agile organizations are characterized by a flat hierarchy and a lack of silos of specialization.

• Fluent, decentralized decision-making. Decision-making must be fast and fluid in agile organizations according to the study participants.

• Lean delivery. This is the translation of Lean principles (flow, avoid waste, quality, voice of the customer) into the activities of the organization.

• Organization as a living organism. This is the opposite of a mechanical, hierarchical organization. That is, focus on plasticity, adaptability, and more permeable structure to foster communication and collaboration.

• Sustainable process. This implies that processes must be efficient, flexible, and cost-effective.

• Team-based organization. This is a distinctive characteristic of Agile since its inception: work based on small teams. The participants see this as a general characteristic that encompasses the whole organization.

• Value-oriented delivery. This characteristic involves identifying what is value for the organization and its users/customers, and focusing the organization on delivery this value. All the activities and efforts of the organization are oriented to this end.

Of the 32 characteristics, only 16 are sufficiently relevant to account for 80% of the mentions by the study participants, and the first 10 accounts for more than half of the mentions.

Looking only at the 16 characteristics most frequently mentioned, we see that several of them are cross-cutting and it is difficult to assign them to one of the 9 dimensions into which we have synthesized the 15 business agility models we reviewed in the analysis of the available literature: “Adaptability”, “Communication”. Additionally, “Customer centricity” is more an axis or focus than a real dimension of Business Agility for authors of models.

This list (and the complete and detailed one in Appendix A) helps us to answer RQ2. From the objectives of the Agile Transformations (or characteristics presented by the transformed organizations) that can be mapped to the dimensions of the analyzed models, we see that:

• The dimension most frequently mentioned by the authors of the models (leadership) is not included in the list of the 16 most valued by the participants in the study.

• The second most common dimension in the models (definition of processes, in 12 of the 15 analyzed) would correspond to the characteristics “Organization as a live organism”, “Flat organization”, and “Team-based organization”, which together account for 15.6% of the mentions by the participants in the study, here there is a coincidence.

• Delivery of value through products and services is mentioned in less than half (6 of 15) of models and can be represented by “Value-oriented delivery”, and “Lean delivery”). This accounts for 11.4% of the mentions by participants.

• Cultural aspects (related to “Adaptive culture”, “Culture of continuous improvement”, and “Learning organization”), account for 10.4% of the mentions.

• The remaining aspects mentioned by the survey participants and can be mapped to dimensions of the Business Agility models have a lesser impact:

People (“Motivated people”, “Employee Experience”), 6.4%

• Strategy (“Alignment”), 6.2%

• Processes (“Sustainable process”), 6.1%

• Governance (“Fluent, decentralized decision making”), 4.3%

In summary, the sum of the most relevant objectives for the organizations participating in the study that can be assimilated into the dimensions of the Business Agility models is 60% out of a possible 80%. This seems to indicate that the deviation between the models and the experience of the participating organizations is not very dramatic, although the absence of leadership and technology, which are very relevant for the models and hardly relevant for the organizations in the study, must be taken into account.

How does the list of 32 characteristics distilled from the participant in the study compare with other surveys from the industry? As mentioned above, one of the best-known reports in the industry is the “State of Agile”, which reached its 17th edition in 2024 [26]. This report is based on a survey in which, in the latest edition available (data from 2023) it is based on the responses of 788 participants from very diverse organizations: 31% from large companies, with more than 20,000 employees; 29% from less than 1000; and 20% from 1001 to 5000 and from 5001 to 20,000; almost half of them from North America, 26% from Europe, and the rest from other parts of the world. Although this study does not meet the conditions, methodology, and rigor of an academic paper, it is a good example of gray literature and is commonly used as a reference in the industry.

There are other practitioner studies but with less impact. For example, the “State of Agile culture” [39] has only 3 editions so far (the last in 2023), although very focused on Agile leadership. The complete “Scrum Team Survey” [40] is associated with an academic paper [14] although it focused only on teams applying the Scrum framework.

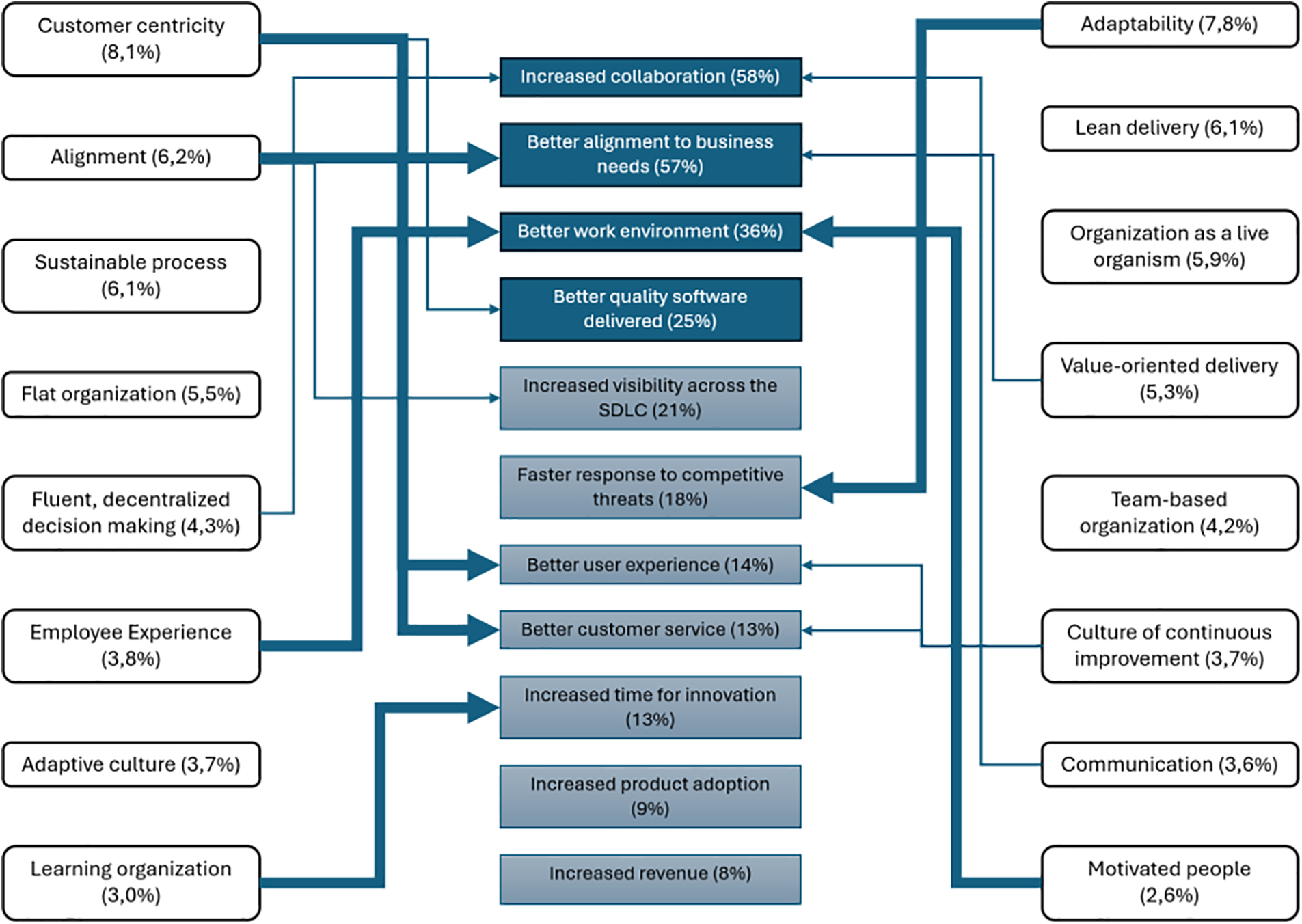

The “State of Agile” report includes two key sections on the drivers for adopting Agile and the outcomes achieved after adoption. Figs. 4 and 5 illustrate how they align with the objectives identified in our study. Fig. 6 shows, in the center, the answers to the question “What drives Agile adoption” in the “State of Agile” report with the percentage of responses according to that document. The 16 objectives most frequently mentioned by the participants in our study are shown on the right and left. As can be seen, there is only a partial alignment between the two visions. Some of the survey’s objectives address aspects that were not considered in our study (cost management, increasing revenue, or Digital Transformation). There is a relative affinity between the two in several cases, particularly in the areas of adaptability and organizational structure. However, there is a notable alignment between the primary motivation identified in the survey (“Prioritize, deliver, and measure incremental customer and business value”) and other key themes in our study, including Customer Centricity, Lean Delivery, and Value-Oriented Delivery.

Figure 6: Drivers of adoption in the State of Agile report, compared to the results of our study (the thicker line indicates a greater affinity between the elements of both works)

Fig. 7 provides a comparison of the results of our study (on the left and right sides) with the main benefits identified in the “State of Agile” survey. In this case, there is a greater degree of alignment. “Better alignment to business”, “Improvement of the work environment”, and “Faster response to competitive threats”, among others, align quite well with some of the objectives identified by the participants in our study, especially the two most mentioned: Adaptability and Customer centricity. As in the previous figure, the relationship between the most related elements has been highlighted with a thicker line. For instance, the concept of “Alignment” in our study is clearly aligned with the idea of “Better alignment to business needs” as outlined in the State of Agile report.

Figure 7: Benefits of adoption of Agile in the State of Agile report, compared to the results of our study (the thicker line indicates a greater affinity between the elements of both works)

We believe that the lower alignment in one case and the higher alignment in the other can be attributed to the way the questions were phrased and interpreted by the participants. In our study, we inquired about the objectives of organizations that undergo Agile Transformation. If participants had difficulty identifying these objectives, the question was reformulated to prompt them to describe the characteristics of an agile organization. This approach was taken with the understanding that it would help participants articulate the desired state of their organization. The “State of Agile” survey asks for objectives and results, but it is difficult to interpret in what sense the answers have been produced.

Finally, with regard to RQ2, we can conclude that the vision of the practitioners reflected in models and surveys does not fit perfectly the transformation objectives set out in the study. That does not mean that it is completely different. On the contrary, we have found commonalities in very important aspects: for example, the focus on customer needs (customer centricity), which has other consequences, such as the generation of learning through feedback, or the need to prioritize and pivot; we also see commonalities in the need for alignment, transparency, and communication, or in the changes in the organizational structure. Undoubtedly, explicit and implicit in all practitioners’ visions is the need to generate greater adaptability to the environment, which is in fact one of the key elements of some industry definitions of Business Agility: “… is a set of organizational capabilities, behaviors, and ways of working that give your organization the freedom, flexibility, and resilience to achieve its purpose. No matter what the future brings.” [33]

One possible reason for the misalignment could be the different nature of the data sets, but there may be others, such as the fact that the experiences of the practitioners are not as diverse, or that there is a large component of ideas and desires that do not match reality. For example, leadership receives a lot of attention in the form of books and nonacademic articles, which may have translated into giving it a relevance that it does not have in practice for organizations involved in Agile Transformations.

4.3 The Vision of the Characteristics of Agile Organizations according to the Type of Company

Is there a significant difference between the two types of participant organizations? This is the question stated in our RQ3. We will try to answer this question from the point of view of the relevance of the objectives for the two main types of organizations participating in our study, as well as the way they define these objectives. The former is more decisive, and the latter is a complement.

4.3.1 Differences in the Relevance of Objectives

Let us keep in mind that almost half of the participants in our study are organizations that are going through a transformation process (“final organizations”). The other half are companies that are helping others transform, which we can generally define as consultants. Table 6 shows the list that compares the two visions with the characteristics that account for 80% of the responses, ordered by the percentage of mentions:

There are some significant differences here. For example, “Lean Delivery”, second on the list for end users (8.2% of responses), is ranked 13th for consultants (2%). Another significant difference is the “Culture of continuous improvement” which ranks sixth in importance for consultants (5.8%) but 19th for final companies (2%). The biggest difference in terms of the percentage of mentions is for “Alignment”, which also has a big difference in the order in the list (first for consulting firms, 11th for enterprises), followed by “Lean Delivery” and “Customer Centricity” (first with 10% of mentions for enterprises, and 5th with 4.2% for consulting firms).

Fig. 8 shows the 16 more frequently mentioned objectives by the sum of participants. On the left side is the frequency of mentions by final organizations (those that develop transformations), while on the right side is the frequency of mentions by consultants. Objectives with a lower deviation (below 0.01 standard deviation between the value of the final organizations and the value of consultants) are highlighted in a square. In general, and looking at the dimensions, it can be observed that the final organizations give greater relative importance (in terms of the total weight of each dimension) to issues related to delivery and the structure of the organization. However, they are less relevant to technology. As for the consulting firms, the view is more balanced, giving more importance than the final companies to aspects related to people, strategy, and governance of the organization. Another possible way to analyze the results is according to the size of the final organizations, although we have only 4 medium companies out of a total of 16. Compared to the remaining companies, all of which are large, we can see a lower relevance of aspects related to the structure of the organization (“Flat organization”, “Team-based organization”) and a greater presence in the top positions of characteristics related to the delivery of value (“Customer Centricity”, for example, has twice the weight for medium-sized companies than for large ones). In any case, it does not seem to be a sufficiently significant sample to draw conclusions about the difference in size between companies.

Figure 8: Vision of the 16 more frequently mentioned objectives by final organizations and consultants (objectives with the lowest deviation are highlighted inside rectangles)

So, the answer to our RQ3 is that there are differences between the visions of the two types of organizations. These differences are not dramatic, but they are significant and should force companies that help others in their transformation processes to review their vision and understanding of their customers; otherwise, they may contribute to the failure of the transformations and not achieve the intended goals.

4.3.2 Differences in the Definition of Objectives

As a complement to the previous section, we will examine in more detail the similarities and differences between the conception of final organizations and consultants. As explained previously, the 32 identified objectives are the result of a process of analysis and synthesis. It should be noted that the study participants did not give them this name, nor did they choose from a predefined list; they freely proposed a list of objectives. For example, when the final organizations and consultants talk about “Customer-centricity”, “Communication”, or “Adaptability” do they mean the same thing?

To further define the transformation objectives, one of the information gathered during the study was how to measure the achievement of these objectives. In other words, it was not enough to state that “transparency”, for instance, is a desirable quality in the organization as a result of the transformation process, but participants were also asked to indicate how they would ensure that it had been achieved: what metrics or behaviors would demonstrate that this transparency had been achieved.

Looking at one of the objectives most frequently cited by the two types of participating organizations, “Adaptability”, the analysis of the metrics or evidence that would determine that this objective has been achieved can be summarized in Fig. 8 (elements arranged to facilitate legibility). This analysis is based on a smaller volume of data and with a greater dispersion than the other questions posed to the study participants. Nevertheless, it is possible to see that there is a degree of partial agreement, as in the case of the more general question of the priority given by each type of organization to the objectives of transformation. Fig. 9 illustrates, with a thicker line, the elements mentioned by final organizations and consultants that are the same or related.

Figure 9: Concept of “Adaptability” according to the two main types of organizations participating in the study (similar or very close items in the list of the two types of organizations are shown joined with a thicker line)

There is a clear correspondence in some elements. For example, those related to the work model or the measurement of the organization’s financial results as an indicator of its ability to adapt. In other cases, the relationship exists, but it is not that clear. For example, “lead time” is an indicator that is explicitly and frequently mentioned by consultants. The same type of indicator is embedded (but curiously not explicitly mentioned) in the “ability to react and respond” of final organizations.

It can be seen that there is a greater tendency for final organizations to assess adaptability in terms of innovation and financial performance, in addition to responsiveness. Consulting firms have more dispersed interests but seem to place more importance on the use of customer and process metrics (feedback and lead time), as well as the ability to prioritize and manage the portfolio.

4.3.3 Impact of Other Organizational Characteristics

Although the main way to differentiate organizations from each other was their relationship with Agile Transformations (by performing them or helping others perform them), there are other criteria for doing so. The size of the organizations has already been mentioned, but information was also collected on their age or how long the transformation process had been going on (the latter factor only for the final organizations). The main drawback is that the sample of organizations is not very large: of the 16 final organizations, 10 have more than 1000 employees and 6 fewer (and only 1 less than 100); as for the consulting firms, the majority (8 out of 14) are very small firms with less than 10 employees.

The age of the organizations is also very diverse: from less than 10 years to more than 150 years. Another possible criterion for ranking the responses is the time since the beginning of the transformation process, although this factor only applies to the last organizations. Of all these factors, the ones that provide a sufficient number of organizations for further analysis are the size and years since Agile was introduced into the organization. In the first case, we can distinguish between large organizations (more than 1000 employees) and all others. In the second, we could define processes as “recent” (since 2020) and long-standing (before that year, which is often mentioned in all conversations as a key milestone, being the year of the COVID-19 pandemic).

Table 7 shows the list of the 16 most mentioned objectives (weighted values) for final organizations with more and fewer than 1000 employees. In both cases, these 16 objectives account for just over 80% of the mentions. The objectives that appear in both lists have been highlighted.

When comparing the lists, the differences between the two types of organizations do not seem to be very pronounced, with some exceptions such as ‘Adaptive culture’ (7th in one case, 15th in the other). Even when looking at the weighted value, the biggest gap is in ‘Flat organization’ (7% of mentions in those with more than 1000 employees and 4% in the others). But if we look at the data statistically, there are significant overlaps and differences between large and small companies, and between large and small companies and consultants. If we take the statistical correlation as a measure, we see that the affinity between large organizations and consultants is much higher (correlation 0.654, where 1 is the highest possible value) than between companies of different sizes (correlation 0.543) and especially between organizations with fewer than 1000 employees and consultants (correlation 0.407).

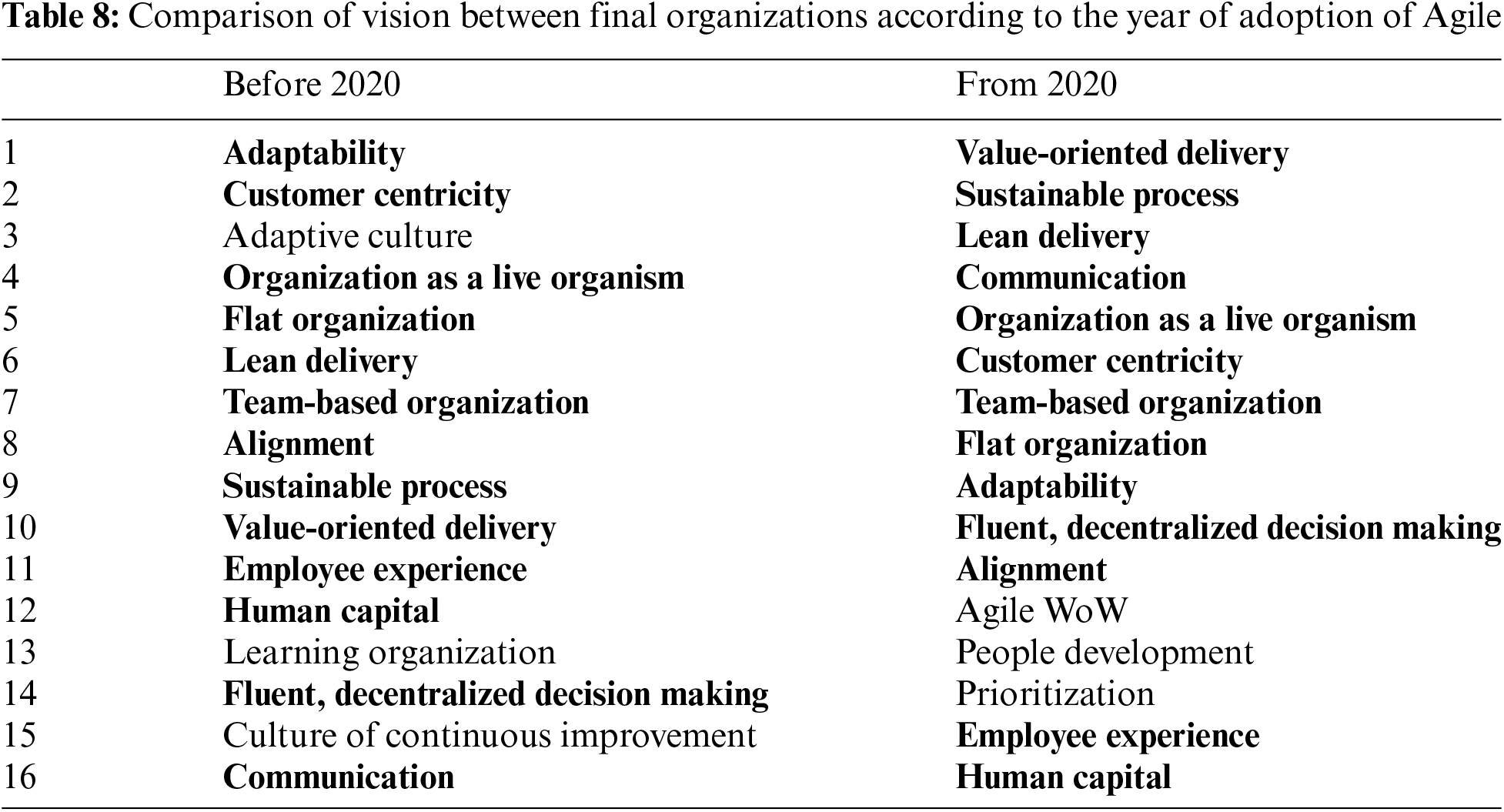

What happens if we look at the vision in terms of when Agile was introduced to the organization? As mentioned earlier, we used 2020 as a cut-off point because it is common for organizations to mention the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic as a milestone in terms of adopting Agile practices. The date of adoption of Agile in the organizations participating in the study ranges from 2009 to 2022, but if we separate those who started their transformation before 2020 and those who started from that year, we get two sets of 9 and 7 organizations, respectively. The list, ranked by the relevance of the objectives according to the weighted values, is shown in Table 8 (the entries appearing in the two lists have been highlighted).

The vision of the organizations that started their transformation earlier has a lower dispersion of objectives: the first 16 accounts for almost 90% of the weighted responses, while in the case of organizations that started later, it is 80%. It is also noticeable that “Adaptability” and “Customer Centricity” are not in the usual top positions in the other groups. In any case, there is a lot of overlap between the two lists (highlighted values). What does the statistical correlation tell us? There is more overlap between the view of companies that started their transformation before 2020 and consultancies (statistical correlation 0.64) than between the two types of companies by year of adoption (0.534) and between companies that started in 2020 and consultancies (0.502).

To facilitate the reading of these data, Table 9 summarizes the correlation coefficient between the different ways of grouping the organizations participating in the study. In any case, these data, while interesting, are based on a very small sample. Any further analysis should start by increasing the number of participating organizations to see if these differences and affinities are confirmed or, on the contrary, are just an effect of having a small data set (note that we are comparing sets of 10 and 6 organizations, respectively).

4.4 Limitations and Disadvantages

The study was carried out with 30 organizations from two countries: Spain, the vast majority, and Colombia. Obviously, a limitation of the study is the diversity of the study: there could have been more companies from other countries. In terms of sectors, there was considerable diversity (banking, insurance, telecommunications, commodities, services, manufacturing), with the exception of public administration. The size of the companies represented varied widely, from a few dozen to tens of thousands of employees. In the case of consulting firms (companies that help third parties in their transformation processes), we dealt mainly with small companies, even freelancers, rather than large consulting firms (with thousands of employees).

Most organizations that carried out their transformation processes recognized that the origin was the introduction of Agile frameworks in their own IT areas. The consultants who participated in the study agreed: that in their experience, Agile entered organizations as a way to improve IT, particularly in the area of software development, and then spread to other areas of the organization. In very rare cases, some organizations recognized that Agile adoption had occurred outside of IT. This pattern (which also coincides with the experience of the authors and most practitioners) only reinforces the idea that Business Agility is a way of transforming organizations from ideas born in the world of Software Engineering, although perhaps a larger sample might have shown different patterns.

A common question from the participants was whether we asked them for their (individual) vision or for the vision of the company. Given that not all the organizations had defined policies or visions on Business Agility, the criterion followed was that participants should provide their personal vision, assuming that, either by being part of the Transformation teams or by advising third parties, they faithfully reflected the reality of each organization. It has been very difficult to get more than a few hours (maximum 3) to conduct workshops and interviews. Although a lot of information has been collected, this time limitation has not allowed us to go as deep as we like.

The analysis of the information has been purely manual. Although an attempt was made to use Artificial Intelligence via publicly available LLMs, the results were not satisfactory. Therefore, there has been no choice but to develop the work manually, which is a more laborious and error-prone way, but with results that are more in line with the objectives of the study.

Finally, the result of this work has received very positive feedback from participants, but no systematic and complete validation of the result has been done yet with a sample of people from other organizations.

This study sheds light on the true vision of organizations seeking to take real advantage of Agile with a wider transformation that supports the effective introduction of Agile frameworks in their IT or Technical departments. The results show that the goals organizations are trying to achieve with these transformations go far beyond the improvements focused on how to develop software or improve their engineering departments. That is, in this case, a process born from the realm of Software Engineering has the potential to change the entire organization. Having a qualitative and open vision of the organizations involved, without preconditions, has allowed us to go deeper into their vision, overcoming the limitations that may be imposed by the use of predefined questionnaires. In this way, we have been able to determine what the fundamental characteristics of Business Agility are, as perceived by the organizations directly involved in the transformation processes to achieve this state.

In the literature, Business Agility is defined primarily as a form of flexible and rapid adaptation to the challenges that organizations face. In this article, we have shown that this vision is consistent with that of organizations while adding a few nuances. Organizations believe that achieving this state of Business Agility will mean that they will be able to focus on their customers (and users), gain in adaptability and alignment, be able to be value-driven, and deliver value in a Lean way, and thus define a sustainable process. These organizations will be flatter, less rigid, and more “organic”, based on teams, which will facilitate, among other things, fluid and decentralized decision-making. We have also been able to verify that there is no total coincidence between the vision of the organizations concerned and the non-academic literature (since the academic literature is less abundant). Of particular concern is the divergence between the vision of organizations undergoing transformation and those providing support, with the latter often lacking alignment with the former.

An obvious question after gaining this insight is, “How can this state of Business Agility be achieved?” The answer is Agile Transformations as we mentioned earlier and the organizations in the study are developing or helping others to develop. But for these transformations to be effective and help organizations reach this state of greater adaptability, we need a good understanding of where the focus of the transformation will be most effective and what can help overcome the obstacles. Therefore, the next step of this work is the analysis of other results obtained during workshops and interviews. We believe that the most useful are those related to Agile Transformations: identification of the most relevant aspects or dimensions to put the focus of the transformation and what factors help organizations to develop these transformations.

Organizations are looking for ways to be sustainable over time, which, as we have seen, implies developing the ability to adapt, focus on their customers (and users), align their efforts, or generate a sustainable process, among other characteristics. Achieving the state of Business Agility is one of the possible ways to achieve this state of adaptive organization. Understanding the mechanisms to reach this state will be of great help in helping all types of organizations overcome the challenges they face on a daily basis.

Finally, Agile represents another significant Software Engineering contribution, offering a valuable tool for driving global improvements in organizational performance. Agile was developed with the specific goal of improving software development in small teams. However, it has evolved to assist with the development of large projects and products and to become a philosophy and collection of techniques and frameworks whose impact extends well beyond IT. Our study has enabled us to confirm that organizations seeking to overcome the obstacles that prevent them from fully utilizing the potential of Agile are developing transformation processes that affect the entire company and all its areas.

Acknowledgement: The authors also gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions of the reviewers, which have improved the presentation.

Funding Statement: This work has received funding from the European Commission for the Ruralities Project (grant agreement no. 101060876).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Alonso Alvarez, Borja Bordel Sánchez; data collection: Alonso Alvarez; analysis and interpretation of results: Alonso Alvarez; draft manuscript preparation: Alonso Alvarez, Borja Bordel Sánchez. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. K. Beck et al., “Agile manifesto,” 2001. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://agilemanifesto.org/ [Google Scholar]

2. B. Boehm and T. Richard, “Management challenges to implementing agile processes in traditional development organizations,” IEEE Softw., vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 30–39. doi: 10.1109/MS.2005.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. H. Takeuchi and I. Nonaka, “The new new product development game,” Harvard Bus. Rev., pp. 137–146, Jan. 1986. [Google Scholar]

4. T. J. Gandomani, H. Zulzalil, A. Bakar, and M. Sultan, “Towards comprehensive and disciplined change management strategy in agile transformation process article in,” 2012. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262976245 [Google Scholar]

5. S. Mundra, Enterprise Agility: Being Agile in a Changing. Brimirham, UK: World Packt Publishing, 2018. [Google Scholar]

6. A. F. Sommer, “Agile Transformation at LEGO Group: Implementing Agile methods in multiple departments changed not only processes but also employees’ behavior and mindset,” Res. Technol. Manag., vol. 62, no. 5, pp. 20–29, Sep. 2019. doi: 10.1080/08956308.2019.1638486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. B. E. Baran and H. M. Woznyj, “Managing VUCA: The human dynamics of agility,” Organ. Dyn., vol. 50, no. 2, Apr. 2021, Art. no. 100787. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2020.100787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. K. Dikert, M. Paasivaara, and C. Lassenius, “Challenges and success factors for large-scale agile transformations: A systematic literature review,” J. Syst. Softw., vol. 119, no. 10, pp. 87–108, Sep. 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.06.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. D. Naslund and R. Kale, “Is agile the latest management fad? A review of success factors of agile transformations,” Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci., vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 489–504, Dec. 2020. doi: 10.1108/IJQSS-12-2019-0142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. D. Brosseau, S. Ebrahim, C. Handscomb, and S. Thaker, “The journey to an agile organization,” 2019. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://shorturl.at/efAM5 [Google Scholar]

11. M. Paasivaara, B. Behm, C. Lassenius, and M. Hallikainen, “Large-scale agile transformation at Ericsson: A case study,” Empir. Softw. Eng., vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 2550–2596, Oct. 2018. doi: 10.1007/s10664-017-9555-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. M. J. Page et al., “PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews,” BMJ, vol. 372, 2020, Art. no. n160. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. M. Laanti, O. Salo, and P. Abrahamsson, “Agile methods rapidly replacing traditional methods at Nokia: A survey of opinions on agile transformation,” Inf. Softw. Technol., vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 276–290, Mar. 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2010.11.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. C. Verwijs and D. Russo, “A theory of scrum team effectiveness,” ACM Trans. Softw. Eng., vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 1–51, 2023. doi: 10.1145/3571849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. M. Laanti and P. Kettunen, “SAFe adoptions in FinLand: A survey research,” in Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme Programming–Workshops, R. Hoda, Ed., Cham: Springer, 2019, vol. 364. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30126-2_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. M. Paasivaara, “Adopting SAFe to scale agile in a globally distributed organization,” in Proc. -2017 IEEE 12th Int. Conf. Global Softw. Eng. (ICGSE), Buenos Aires, Argentina, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Jul. 2017, pp. 36–40. doi: 10.1109/ICGSE.2017.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Y. Kaya, “Agile leadership from the perspective of dynamic capabilities and creating value,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 21, Oct. 2023, Art. no. 15253. doi: 10.3390/su152115253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. H. Zhang, H. Ding, and J. Xiao, “How organizational agility promotes digital transformation: An empirical study,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 14, Jul. 2023. doi: 10.3390/su151411304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. D. Dewantari, T. Raharjo, B. Hardian, A. Wahbi, and F. Alaydrus, “Challenges of agile adoption in banking industry: A systematic literature review,” in 2021 25th Int. Comput. Sci. Eng. Conf. (ICSEC), Chiang Rai, Thailand, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021, pp. 357–362. doi: 10.1109/ICSEC53205.2021.9684622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. R. Hekkala, M. -K. Stein, M. Rossi, and K. Smolander, “Challenges in transitioning to an agile way of working,” Agile Lean Discov. Dev., 2017. doi: 10.24251/HICSS.2017.000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. T. Javdani Gandomani, and M. Ziaei Nafchi, “An empirically-developed framework for Agile transition and adoption: A Grounded Theory approach,” J. Syst. Softw., vol. 107, pp. 204–219, Sep. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.06.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lu and K. (Ram) Ramamurthy, “Understanding the link between information technology capability and organizational agility: an empirical examination,” MIS Quart., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 931–954, 2011. doi: 10.2307/41409967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. S. Denning, “Successfully implementing radical management at Salesforce.com,” Strat. Leadership, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 4–10, Nov. 2011. doi: 10.1108/10878571111176574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. P. Paterek, “Agile transformation in project organization view project knowledge management in agile project teams view project,” 2017. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316813243 [Google Scholar]

25. Dean Leffingwell, “SAFe 6.0,” 2022. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scaledagileframework.com/safe/ [Google Scholar]

26. A. I. Digital, “The 17th state of agile report,” 2024. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://stateofagile.com/ [Google Scholar]

27. K. Harbott, The 6 Enablers of Business Agility: How to Thrive in an Uncertain World. Oakland, CA, USA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2021. [Google Scholar]

28. D. Rigby, S. Elk, and S. Berez, Doing Agile Right. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

29. J. Hesselberg, Unlocking Agility: An Insider’s Guide to Agile Enterprise Transformation. London, UK: Addison-Wesley Professional, 2018. [Google Scholar]

30. M. K. Spayd and M. Madore, Agile Transformation: Using the Integral Agile Transformation Framework to Think and Lead Differently. London, UK: Addison-Wesley Professional, 2020. [Google Scholar]

31. E. Leybourn, “Domains of agility,” 2016. The Agile Director. Accessed: Jul. 9, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://theagiledirector.com/article/2016/11/24/domains-of-agility/ [Google Scholar]

32. Scaled Agile Framework, “Business agility,” 2023. Jul. 2023. Accessed: Jul. 9, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://scaledagileframework.com/business-agility/ [Google Scholar]

33. A. Sidky, E. Leybourn, and L. Powers, “Domains of business agility,” The Business Agility Institute. 2023. Accessed: Jul. 9, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://businessagility.institute/domains/overview [Google Scholar]

34. Agile Business Consortium, “What is business agility?,” 2023. Accessed: Jul. 9, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.agilebusiness.org/business-agility.html [Google Scholar]

35. Agility Health, “Enterprise business agility strategy model,” 2023. Accessed: Oct. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://agilityhealthradar.com/enterprise-business-agility-model/ [Google Scholar]

36. W. Aghina et al., “The 5 trademarks of agile organizations,” McKinsey, Jan. 22, 2018. Accessed: Jul. 9, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-five-trademarks-of-agile-organizations#/ [Google Scholar]

37. PMI, “The Disciplined Agile® Enterprise (DAE),” 2024. Accessed: Jul. 9, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.pmi.org/disciplined-agile/process/dae [Google Scholar]

38. B. G. Glaser and A. L. Strauss, The Discovery of Grounded Theory. London, UK: Routledge, 1999. [Google Scholar]

39. Agile Business Consortium, “The 3rd state of agile culture report,” 2024. Accessed: Aug. 1, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.stateofagileculture.com/ [Google Scholar]

40. The Liberators, “The scrum team survey,” 2023. Accessed: Aug. 1, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scrumteamsurvey.org/ [Google Scholar]

41. R. Greenleaf, “The servant as leader,” in Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2007, pp. 79–85. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70818-6_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. B. Bogsnes, “Beyond budgeting,” in Implementing Beyond Budgeting. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2016, pp. 55–90. doi: 10.1002/9781119449577.ch2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. N. Modig, This is Lean: Resolving the Efficiency Paradox. Stockholm, Sweden: Rheologica Publishing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

44. E. Ries, The Lean Startup. New York, NY, USA: Best Business, 2011. [Google Scholar]

45. D. Pink, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. London, UK: Riverhead Books, 2009. [Google Scholar]

46. A. Edmondson, “Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams,” Admin. Sci. Quart., vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 350–383, Jun. 1999. doi: 10.2307/2666999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. S. Denning, The Age of Agile: How Smart Companies are Transforming the Way Work Gets Done. Washintong, DC, USA: Amacom, 2018. [Google Scholar]

48. D. Russo, “The agile success model: A mixed-methods study of a large-scale agile transformation,” Assoc. Comput. Mach., Jul. 1, 2021. doi: 10.1145/3464938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Appendix A. Characteristics of agile organizations.

Below is the complete list of 32 characteristics generated during the refinement process based on selected topics proposed by participants. These definitions are derived from the analysis of the data provided by the study participants. Each characteristic is marked as present or absent in the top 10 most mentioned ones:

• Adaptability (10 most important). The most frequently valued characteristic, and as well as one of the most frequently mentioned in the literature [24] as example of academic paper, and [10] from practitioners. It is the ability to detect and even anticipate changes in the context and environment of the organization, and from there to apply mechanisms to generate adaptations, if possible, quickly, to respond to these changes and help to improve the organization’s resilience. Adaptability refers, for almost all participants, to the capacity of the organization as a whole, not only to the adaptation of the technological product. In other words, Agile Transformation would thus have the capacity to improve the organization’s ability to adapt to change.

• Adaptive culture. This is a collection of characteristics that are not significant enough to be treated individually. Some of them could be included in other characteristics, such as feedback, commitment, or innovation. However, since they are discussed in the context of organizational culture, it is more appropriate to group them together in this category.

The term ‘Adaptive Culture’ encompasses the fundamental characteristics of an agile organization, including a focus on change, innovation, learning, and feedback. It also emphasizes ownership, empowerment, and teamwork, which are often referred to as ‘Agile culture’ by participants.

Cultural change is a frequently mentioned aspect among participants, although it is not among the most relevant objectives. On the other hand, in the 15 Business Agility models analyzed, it is one of the most important dimensions, mentioned in 11 of them.

• Adaptive leadership. Different characteristics have been grouped here that define a new way of defining and materializing leadership in an organization. What are the characteristics of this leadership style according to the participants? To begin with, it fits quite well with the Greenleaf servant leadership model [41]. It is a generative leadership that prioritizes the growth of people, which is exercised with authenticity, i.e., leading by example. Furthermore, this leadership style is accessible and participative, demonstrating awareness of the need to adapt and promoting change.

Leadership is one of the dimensions most often mentioned by non-academic authors when describing their Business Agility models (13 of 15 models mention Leadership as a dimension of change). However, for study participants, changing the leadership model turns out to be a very secondary objective.

• Adaptive strategy. Although there is an additional characteristic called ‘Adaptability’, we have focused on elements related to the organization’s strategy. The other concept, which is the most mentioned by participant organizations, includes more diverse and general aspects. Here, we discuss the ability to manage budgets that are less rigid and more adaptable [42], review strategies frequently, and implement shorter value-oriented initiatives. Additionally, the ability to pivot or discard activities is important.

This change in strategy is similar to that described by the various authors of non-academic materials. And strategy is one of the most frequently mentioned aspects (in fact, in 10 of the 15 models analyzed in depth). However, we can see that for the participants in the study, the evolution of the strategy is not one of their main objectives.

• Agile WoW. Agile transformations still have a strong component in adopting Agile frameworks, even when Business Agility goes beyond the scope of these frameworks. This characteristic defines the key aspects of the expected way of working in an agile company. It involves an iterative and incremental approach in short cycles, prioritizing work in small batches, conducting periodic retrospectives, and following what is commonly known as the ‘Agile WoW’ (way of working).