Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Shared Natural Neighbors Based-Hierarchical Clustering Algorithm for Discovering Arbitrary-Shaped Clusters

College of Computer and Information Science, Chongqing Normal University, Chongqing, 400030, China

* Corresponding Author: Ji Feng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Data Mining Techniques: Security, Intelligent Systems and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 80(2), 2031-2048. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.052114

Received 23 March 2024; Accepted 14 June 2024; Issue published 15 August 2024

Abstract

In clustering algorithms, the selection of neighbors significantly affects the quality of the final clustering results. While various neighbor relationships exist, such as K-nearest neighbors, natural neighbors, and shared neighbors, most neighbor relationships can only handle single structural relationships, and the identification accuracy is low for datasets with multiple structures. In life, people’s first instinct for complex things is to divide them into multiple parts to complete. Partitioning the dataset into more sub-graphs is a good idea approach to identifying complex structures. Taking inspiration from this, we propose a novel neighbor method: Shared Natural Neighbors (SNaN). To demonstrate the superiority of this neighbor method, we propose a shared natural neighbors-based hierarchical clustering algorithm for discovering arbitrary-shaped clusters (HC-SNaN). Our algorithm excels in identifying both spherical clusters and manifold clusters. Tested on synthetic datasets and real-world datasets, HC-SNaN demonstrates significant advantages over existing clustering algorithms, particularly when dealing with datasets containing arbitrary shapes.Keywords

Clustering is one of the most important methods of data mining [1]. Intuitively, it groups a set of data in a way that maximizes the similarity within a cluster and minimizes the similarity between different clusters [2]. In recent years, cluster analysis has been widely used in many aspects, such as image segmentation [3], business decision-making [4], data integration and other fields. Clustering methods are typically categorized based on their distinct characteristics, including partition-based clustering [5], density-based clustering [6], and hierarchical clustering [7], among others.

Partitioned clustering algorithms are a kind of high-efficiency clustering algorithms. It uses an iteratively updating strategy to optimize the data until reaches the optimal result. Among the representative ones is the K-means algorithm [8]. However, K-means is highly sensitive in the initial choice of cluster centers, and it has limitations in identifying non-spherical clusters. Therefore, researchers have proposed numerous improvement algorithms. For example, Tzortzis et al. proposed the MinMax K-means clustering algorithm [9], which uses the variance weights to weigh initial points, and enhances the quality of initial centers. To improve the performance of K-means in detecting arbitrary shape datasets, Cheng et al. proposed the K-means clustering with Natural Density Peaks algorithm (NDP-Kmeans) [10]. It uses the natural neighbor [11] to compute the density points

To effectively discover arbitrary-shaped clusters, density-based clustering algorithms are proposed [12]. DBSCAN [13] is one of the typical representative algorithms among them. It identifies dense regions as clusters and filters objects in the sparse region. It defines the density of points by setting the radius

Hierarchical clustering seeks to build a hierarchy of clusters [23]. Among them, Chameleon [24] is a representative algorithm in hierarchical clustering algorithms. It uses the K-nearest neighbor graph to express the distribution of datasets. Then, it partitions the nearest neighbor graph according to the hMetis algorithm [25]. Finally, based on the connectivity and compactness of sub-clusters, integrates clusters in a bottom-to-top manner. Although the Chameleon algorithm has good performance, the use environment of the hMetis algorithm is not easy to build, and it does not achieve ideal performance when processing arbitrary-shaped datasets. To improve the Chameleon algorithm’s performance in processing datasets with arbitrary structures, Zhang et al. [26] used the new natural neighbor graph to replace the K-nearest neighbor graphs. Liang et al. [27] employed the DPC algorithm framework to replace both the K-nearest neighbor graphs and the hMetis algorithm. Zhang et al. [28] used the mutual K-nearest neighbors to directly generate sub-clusters, which omits the process of partitioning the graph.

Datasets with complex structures generally refer to those that contain clusters with diverse shapes (including spherical, non-spherical, and manifold), sizes, and densities. Traditional clustering algorithms (e.g., DBSCAN, K-means) are not particularly effective when dealing with such datasets [29]. Natural neighbor is a parameter-free algorithm that adaptively constructs neighbor relationships. This neighbor relationship is very good for the recognition of manifold clusters, but it is not sensitive to datasets with complex structures. The shared neighbor method [30] takes into consideration the association between sample points rather than solely relying on simple distance metrics. This similarity metric better reflects the relationships between data points, particularly when handling non-spherical or variable density data. However, it is relatively sensitive to the choice of the K parameter.

To show that the proposed neighbor method can effectively identify datasets of any structure, we propose the HC-SNaN algorithm. Inspired by natural neighbors and shared neighbors, we propose a new neighbor method-shared natural neighbor method. This method skillfully utilizes the advantages of natural neighbors and shared neighbors, and more effectively reflects the true distribution of data points in complex structures. The algorithm first constructs a shared natural neighbor graph by using shared natural neighbors and then cuts sub-clusters into multiple cut sub-graphs. Next, we merge the fuzzy points with the cut sub-graphs to form initial sub-clusters. Among them, fuzzy points are points not connected in the sub-graph while cutting the sub-graphs. Finally, based on our proposed new merging strategy, the initial clusters are merged. To show the process of our algorithm more clearly, the flow chart of our proposed HC-SNaN algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flow chart of the proposed hierarchical clustering method HC-SNaN

The experimental results on synthetic datasets and real-world datasets show that our algorithm is more effective and efficient than existing methods when processing datasets with arbitrary shapes. Overall, the major contributions of this paper are:

1. We propose a new neighbor method. This method combines the characteristics of natural neighbors and shared neighbors, it shows excellent performance when dealing with variable-density and noise datasets.

2. We propose a new method to generate sub-clusters on shared natural neighbors. This method first uses the shared natural neighbor graph to divide the dataset into multiple sub-clusters. Then uses a new merging strategy to merge into pairs of sub-clusters. Thus, satisfactory clustering results can be obtained on multiple datasets.

3. Experimental results on synthetic and real-world datasets show that the HC-SNaN has more advantages in detecting arbitrary-shaped clusters than other excellent algorithms.

In Section 2, we review research related to natural neighbors and shared neighbors. Section 3 introduces the main principles and ideas of shared natural neighbors and describes the algorithm proposed in this paper in detail. Section 4 demonstrates the analysis of the synthetic experimental result datasets and the real-world datasets while evaluating the algorithm’s performance. Finally, in the concluding section, we summarize the main points of this paper and highlight possible future challenges.

In contrast, the natural neighbor method automatically adapts to the dataset is distribution, eliminating the need for manual K parameter selection. The effectiveness of natural neighbors has been demonstrated in various applications, including cluster analysis, instance approximation, and outlier detection [31–33]. The core idea of natural neighbors is primarily manifested in three key aspects: neighborhood, search algorithm, and the number of neighbors.

Definition 1 (Stable searching state). A stable search state can be reached if and only if the natural neighbor processes satisfy the following conditions:

The parameter

Definition 2 (Natural neighbor). In a naturally stable search algorithm, data points in the immediate neighborhood are considered natural neighbors of each other. Assuming that the search state stabilizes after the

The

A sample and its neighboring data points usually belong to the same cluster category, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the sample’s local density based on its neighboring information. Specifically, the shared region encompassing a sample and its neighbors provides rich local information, aiding in a more precise depiction of the sample’s distribution.

Incorrectly determining similarity can result in misclassifications. The shared region among samples plays a pivotal role in determining sample similarity and local density. Therefore, establishing sample similarity and local density based on the relationships between a sample and its neighbors is crucial for improving clustering accuracy.

Definition 3 (Shared neighbor). For any points

Eq. (4) defines the shared neighbor similarity between

For a sample

where

Identifying any dataset requires excellent recognition ability for complex datasets. In order to identify datasets with complex structures, it is a good way to divide complex structures into multiple simple structures. HC-SNaN algorithm inspired by this has three steps: the first step is to construct a neighborhood graph representing the structure of a dataset, and then partition the neighborhood graph into several sub-graphs and fuzzy points. The second step is to assign fuzzy points to sub-graphs according to rules. The third step is to merge sub-graphs and obtain the final clustering result. In this section, we will detail the details of the algorithm.

3.1 Shared Natural Neighbor SNaN and Shared Natural Neighbor Graph GSNaN

Shared natural neighbors have better adaptability for identifying complex datasets. In comparison to the K-nearest neighbor method, the natural neighbor method is more flexible and exhibits stronger robustness. This flexibility arises from the natural neighbor method’s ability to dynamically acquire neighbors based on the distribution pattern of the environment where the data points are situated. Consequently, it can more effectively adapt to datasets with varying densities and distributions, particularly suited for streaming datasets.

The shared neighbor method establishes similarity between data points based on their shared K -nearest neighbors. To ensure the validity of the similarity measure, shared neighbors require that the data points themselves share a common neighbor. This property allows shared neighbors to avoid combining a small number of relatively isolated points with high density, making it particularly sensitive to datasets with variable density.

Inspired by the advantages of the above two neighbor methods, we propose a new neighbor method-shared natural neighbor. This method is not influenced by neighbor parameters and effectively prevents over-aggregation among high-density points. It demonstrates flexibility in adapting to datasets with different density distributions, making it valuable for discovering clusters with arbitrary structures. Its specific implementation is shown in Eq. (6).

Definition 4 (Shared natural neighbor). For any two natural neighbor points

The quantity of shared natural neighbor for the pair

Fig. 2 illustrates the neighbor graphs of four types of neighbors on the variable-density dataset. After conducting ten experiments, we identified optimal results for both the K-nearest neighbor and shared neighbor graphs. As shown in Fig. 2a, regardless of the chosen K value, the K-nearest neighbor graph failed to express the dataset’s distribution. While the shared neighbor graph in Fig. 2b could discern the variable-density characteristics, it resulted in numerous sub-graphs that may affect the final clustering. In the variable-density dataset, the performance limit of natural neighbor so, it fails to identify the distribution characteristics of accurately of the dataset in Fig. 2c. In contrast, the shared natural neighbor graph in Fig. 2d precisely divided the dataset into two sub-graphs, effectively representing the dataset’s distribution, and without generating excess sub-graphs to affect the sequel clustering process.

Figure 2: Neighbor graphs of the variable-density dataset. (a) K-nearest neighbor (K = 3) (b) shared neighbor (K = 12) (c) natural neighbor (d) shared natural neighbor. Gray points are fuzzy points

3.2 Hierarchical Clustering Algorithm Based on Shared Natural Neighbor

The

Figure 3: Assignment steps of HC-SNaN algorithm (a) Cutting the neighbor graph (b) merge the fuzzy points (c) merge the sub-clusters (d) after allocating local outliers, the final clustering results

Definition 5 (Shared natural neighbor similarity). For any two natural neighbor points

Definition 6 (Sub-cluster core point). For natural neighbors

Definition 7 (Local density of natural neighbor). The local density of the natural neighbor is represented denoted as:

where

Definition 8 (Cluster crossover degree). For

Definition 9 (Shortest distance between sub-clusters). All distances between points in sub-clusters

where

Definition 10 (Natural neighbors shared between sub-clusters). The natural neighbors shared between sub-clusters are represented as:

where

In the segmentation stage of HC-SNaN, we first constructed the shared natural neighbor graph

Moving to the merging phase, we calculate the distance of fuzzy points from the sub-cluster core point, as well as the average distance. Next, we determine the clusters to which the natural neighbors of the fuzzy point are subordinate. Finally, the fuzzy point is assigned to the cluster closest to the core point of the sub-cluster, provided it is smaller than the average distance to the core points of other sub-clusters. Fuzzy points that cannot be assigned are designated as local outlier points. Detailed steps are described in Algorithm 2.

Upon completing the assignment of fuzzy points, an initial cluster is formed. Subsequently, we calculate the cluster crossover degree, the shortest distance between sub-clusters, and the natural neighbors shared between sub-clusters. The merging process continues until the desired number of clusters is achieved. Finally, we assign the

The main improvement of the HC-SNaN algorithm: it constructs sparse graphs based on the shared natural neighbor construction, which not only sparse the data but also improves the rarefaction of the algorithm to different datasets. In the merging phase, the algorithm considers the interconnection and compactness within the data. This operation can better capture the features inside the cluster, which is highly effective for processing datasets with different shape densities.

HC-SNaN mainly includes three steps: The first step is to divide the sub-graph. First, we search the natural neighbor

To illustrate the effectiveness of the HC-SNaN algorithm, we conducted experiments on synthetic datasets and real datasets. These datasets have different scales, different dimensions, and different flow structures. The information of these datasets is shown in Table 1.

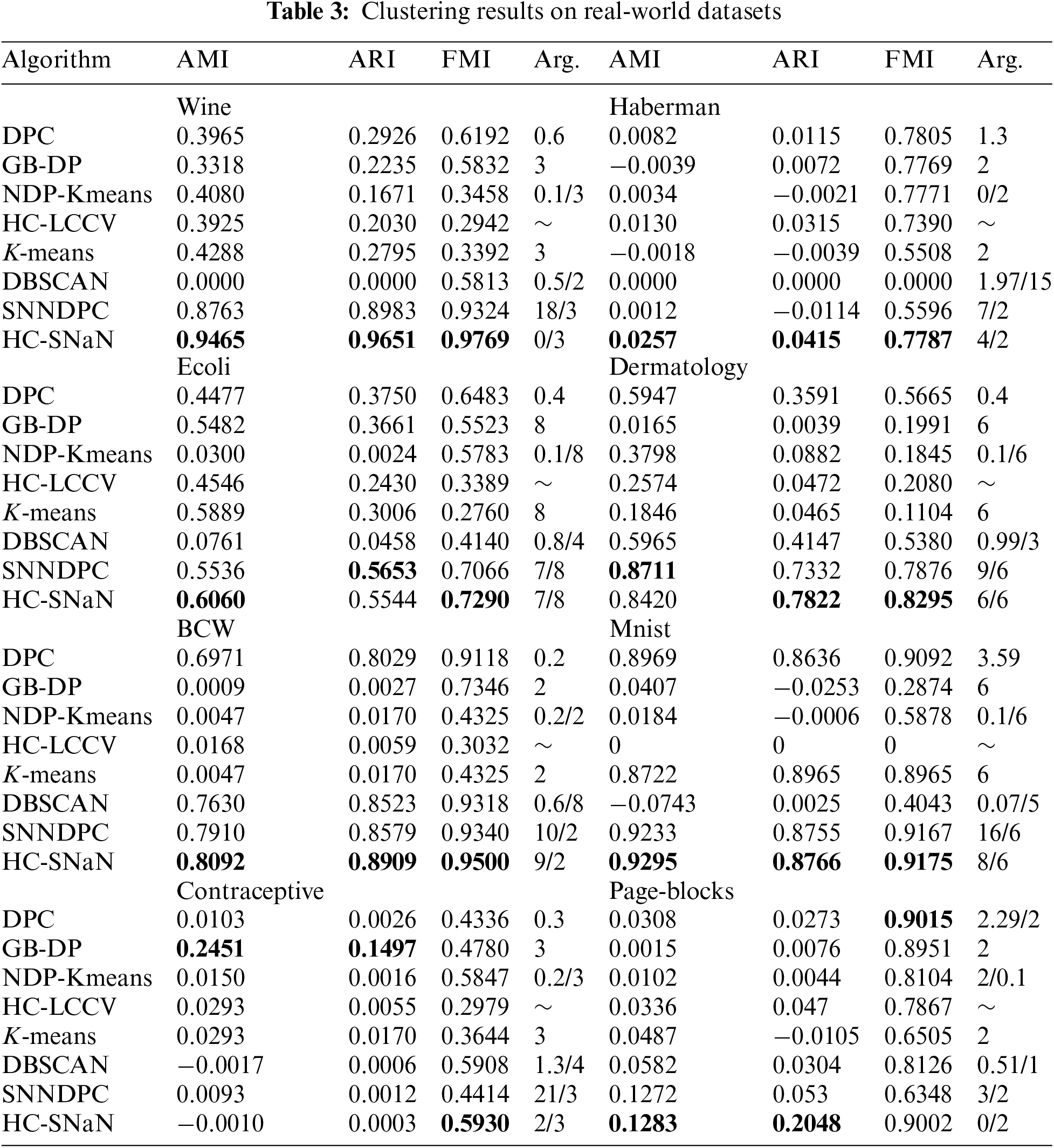

To further assess the superiority of our proposed HC-SNaN algorithm, this section will present a comparison of our algorithm with seven others. These include recent algorithms: GB-DP algorithm [18], SNNDPC algorithm [22], NDP-Kmeans algorithm [10], and HC-LCCV algorithm [34]. Classical algorithms: DBSCAN algorithm [13], K-means algorithm [8], and DPC algorithm [17]. In Tables 2 and 3, the use of boldface indicates the optimal results obtained in the algorithm experiments. The corresponding parameter for achieving the optimal result on the dataset is denoted as Arg.

For parameter settings, K-means and GB-DP algorithms only require specifying the number of clusters. However, due to K-means is instability, we conducted five experiments on each dataset to obtain optimal results. The SNNDPC algorithm requires setting the parameters K and the number of clusters. The NDP-Kmeans algorithm needs to set the proportion of noise points alpha and the number of clusters. HC-LCCV does not require any parameters. DBSCAN requires setting two parameters:

In the experiment, we used AMI [35], ARI [36], and FMI [37] to evaluate the performance of clustering algorithms. The experiments were conducted on a desktop computer with a Core i5 3.40 GHz processor, windows 11 operating system, and 16 GB RAM, running on PyCharm 2022.

4.2 Clustering on Synthetic Datasets

Firstly, we conducted experiments on eight synthetic datasets, including two three-dimensional datasets and one noise dataset. The first five datasets are common and complex. The detailed information on these datasets is listed in Table 1. Fig. 4 shows the clustering results of the HC-SNaN algorithm.

Figure 4: Clustering results of HC-SNaN on synthetic datasets (a–h)

For instance, as shown in Fig. 4a Pathbased dataset, three clusters are closely connected, yet HC-SNaN misallocated only one data point. However, in this dataset, besides the SNNDPC, the metrics of the other six algorithms indicate their failure to recognize even basic shapes. In the Jain dataset depicted in Fig. 4b, HC-SNaN perfectly identifies the dataset. Jain consists of two intertwined clusters shaped like new moons, representing a typical flow dataset with uneven densities. However, according to Table 1, the indicators of NDP-Kmeans are also 1, and SNNDPC’s metrics are all above ninety-seven. Nevertheless, the other five algorithms fail to recognize this dataset. In the Dadom dataset shown in Fig. 4d, HC-SNaN metrics are all 1. Dadom comprises complex manifold clusters. As shown in Table 1, except for HC-SNaN, the other seven algorithms cannot effectively recognize this dataset. In the Aggregation dataset depicted in Fig. 4e, HC-SNaN ranks first in all metrics, while SNNDPC, DPC, and NDP-Kmeans also achieve metrics exceeding ninety. The Chainlink dataset in Fig. 4h is a three-dimension dataset. Although the structure of this dataset seems simple, but significantly different densities between two clusters. HC-SNaN, HC-LCCV, and NDP-Kmeans all yield the best results, while the remaining five algorithms fail to successfully cluster the data.

NDP-Kmeans and GB-DP are algorithms introduced in 2023, whereas SNNDPC and HC-LCCV are relatively new algorithms released within the past five years. Therefore, in this section of results analysis, we selected these four algorithms and presented the clustering outcome graphs for some datasets.

Fig. 5 illustrates the clustering results of GB-DP, HC-LCCV, SNNDPC, and NDP-Kmeans on Compound, T2-4T and Atom datasets. The first line’s Compound dataset consists of six closely connected clusters merged at varying densities. Most algorithms are difficult to identify this dataset. As shown in Fig. 4c, HC-SNaN only misallocated one data point. However, none of these four algorithms could correctly identify this dataset. The second line’s T2-4T is a noise dataset. Ordinary algorithms struggle to recognize noise datasets without appropriate processing, especially when the dataset’s top features two ellipses and a stick-like cluster that are closely linked, easily mistaken for a single cluster. The second line of Fig. 5 reveals that these four algorithms all fail to recognize this noise dataset. The HC-SNaN algorithm obtains sub-graphs and fuzzy points by dividing the shared neighbor graph. In general, the number of natural neighbors shared between fuzzy points is small. In the noise dataset, noise points have fewer neighbors, so they are easily detected as fuzzy points. In Fig. 4f, our algorithm exhibits excellent performance on noise datasets. The third column of Fig. 5 features a three-dimension dataset Atom, which appears simple with just two clusters, but them blends at different densities. While SNNDPC and HC-LCCV both accurately identified this dataset, GB-DP and NDP-Kmeans showed poorer clustering performance.

Figure 5: Results on the synthesized datasets. The first column is the GB-DP result, the second column is the SNNDPC result, the third column is the NDP-Kmeans result, and the last column is the HC-LCCV result

4.3 Clustering on Real-World Datasets

To assess the viability of the HC-SNaN algorithm for high-dimensional data, we conducted comparative experiments with seven other clustering algorithms on eight real-world datasets sourced from the UCI Machine Learning Repository. These real-world datasets vary in scale and dimensions. The clustering results, presented in Table 3 showcase the comparative results of HC-SNaN alongside the other algorithms.

The HC-SNaN consistently outperforms the other algorithms on the Wine, haberman, BCW, and mnist datasets, where metrics like AMI, ARI, and FMI rank first, with some metrics significantly surpassing other algorithms. In the Ecoli datasets, HC-SNaN achieves optimal levels of AMI and FMI metrics, with ARI ranking second. For the Dermatology dataset, HC-SNaN attains the highest ARI and FMI metrics, surpassing the other six algorithms. In the Contraceptive dataset, HC-SNaN exhibits the best FMI performance. The Page-blocks dataset shows the metrics rank first with the AMI and ARI, but the FMI compared to the DPC algorithm witch slightly inferior.

Overall, experimental verification confirms that HC-SNaN outperforms the other seven algorithms on most real-world datasets. The results underscore the algorithm’s high clustering performance in discovering various shapes of clustering structures, particularly excelling in handling clustering tasks in dense regions.

In this paper, we introduce a novel neighbor method called shared natural neighbors (SNaN). The SNaN is derived by combining natural neighbors and shared neighbors, and then a graph

However, it is important to note that our algorithm for processing large-scale high-dimensional data may incur substantial time costs, which is an inherent limitation of hierarchical clustering. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the application of this algorithm to massive high-dimensional datasets.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their professional guidance, as well as the team members for their unwavering support.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJZD-M202300502, KJQN201800539).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhongshang Chen and Ji Feng; Manuscript: Zhongshang Chen; Analysis of results: Degang Yang and Fapeng Cai. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. S. Zheng and J. Zhao, “A new unsupervised data mining method based on the stacked autoencoder for chemical process fault diagnosis,” Comput. Chem. Eng., vol. 135, pp. 106755, Oct. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.compchemeng.2020.106755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. C. Fahy, S. Yang, and M. Gongora, “Ant colony stream clustering: A fast density clustering algorithm for dynamic data streams,” IEEE Trans. Cybern., vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 2215–2228, 2019. doi: 10.1109/TCYB.2018.2822552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. B. Szalontai, M. Debreczeny, K. Fintor, and C. Bagyinka, “SVD-clustering, a general image-analyzing method explained and demonstrated on model and Raman micro-spectroscopic maps,” Sci. Rep., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 4238, 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61206-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. S. Cai and J. Zhang, “Exploration of credit risk of P2P platform based on data mining technology,” J. Comput. Appl. Math., vol. 372, no. 1, pp. 112718, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.cam.2020.112718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. P. Tavallali, P. Tavallali, and M. Singhal, “K-means tree: An optimal clustering tree for unsupervised learning,” J. Supercomput., vol. 77, no. 5, pp. 5239–5266, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11227-020-03436-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. B. Bataineh and A. A. Alzahrani, “Fully automated density-based clustering method,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 1833–1851, 2023. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2023.039923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. H. Xie, S. Lu, and X. Tang, “TSI-based hierarchical clustering method and regular-hypersphere model for product quality detection,” Comput. Ind. Eng., vol. 177, no. 2, pp. 109094, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2023.109094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. J. MacQueen, “Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations,” Proc. Fifth Berkeley Symp. Math. Stat. Probab., vol. 1, pp. 281–297, 1967. [Google Scholar]

9. G. Tzortzis and A. Likas, “The MinMax k-means clustering algorithm,” Pattern Recognit., vol. 47, no. 7, pp. 2505–2516, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2014.01.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. D. Cheng, J. Huang, S. Zhang, S. Xia, G. Wang and J. Xie, “K-means clustering with natural density peaks for discovering arbitrary-shaped clusters,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., pp. 1–14, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3248064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Q. Zhu, J. Feng, and J. Huang, “Natural neighbor: A self-adaptive neighborhood method without parameter K,” Pattern Recognit. Lett., vol. 80, no. 1, pp. 30–36, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2016.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. A. Fahim, “Adaptive density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (ADBSCAN) for clusters of different densities,” Comput. Mater. Contin., vol. 75, no. 2, pp. 3695–3712, 2023. doi: 10.32604/cmc.2023.036820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. M. Ester, H. P. Kriegel, J. Sander, and X. Xu, “A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise,” in Proc. Second Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min., Portland, OR, USA, 1996, vol. 96, pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

14. Y. Chen et al., “Decentralized clustering by finding loose and distributed density cores,” Inf. Sci., vol. 433, no. 1, pp. 510–526, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2016.08.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. M. Daszykowski, B. Walczak, and D. L. Massart, “Looking for natural patterns in data: Part 1. Density-based approach,” Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst., vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 83–92, 2018. doi: 10.1016/S0169-7439(01)00111-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Y. A. Geng, Q. Li, R. Zheng, F. Zhuang, R. He and N. Xiong, “RECOME: A new density-based clustering algorithm using relative KNN kernel density,” Inf. Sci., vol. 436, no. 4, pp. 13–30, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2018.01.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. A. Rodriguez and A. Laio, “Clustering by fast search and find of density peaks,” Science, vol. 344, no. 6191, pp. 1492–1496, 2014. doi: 10.1126/science.1242072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. D. Cheng, Y. Li, S. Xia, G. Wang, J. Huang and S. Zhang, “A fast granular-ball-based density peaks clustering algorithm for large-scale data,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., pp. 1–14, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3300916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. S. Xia, Y. Liu, X. Ding, G. Wang, H. Yu and Y. Luo, “Granular ball computing classifiers for efficient, scalable and robust learning,” Inf. Sci., vol. 483, no. 5, pp. 136–152, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2019.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. S. Xia, S. Zheng, G. Wang, X. Gao, and B. Wang, “Granular ball sampling for noisy label classification or imbalanced classification,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 2144–2155, 2023. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3105984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. S. Xia, X. Dai, G. Wang, X. Gao, and E. Giem, “An efficient and adaptive granular-ball generation method in classification problem,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 5319–5331, 2024. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3203381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. R. Liu, H. Wang, and X. Yu, “Shared-nearest-neighbor-based clustering by fast search and find of density peaks,” Inf. Sci., vol. 450, no. 1, pp. 200–226, Oct. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2018.03.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Z. Chu et al., “An operation health status monitoring algorithm of special transformers based on BIRCH and Gaussian cloud methods,” Energy Rep., vol. 7, pp. 253–260, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2021.01.07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. G. Karypis, E. H. Han, and V. Kumar, “Chameleon: Hierarchical clustering using dynamic modeling,” Computer, vol. 32, no. 8, pp. 68–75, 1999. doi: 10.1109/2.781637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. G. Karypis, R. Aggarwal, V. Kumar, and S. Shekhar, “Multilevel hypergraph partitioning: Application in VLSI domain,” in Proc. 34th Annu. Design Autom. Conf., Anaheim, CA, USA, 1997, no. 4, pp. 526–529. doi: 10.1145/266021.266273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Y. Zhang, S. Ding, Y. Wang, and H. Hou, “Chameleon algorithm based on improved natural neighbor graph generating sub-clusters,” Appl. Intell., vol. 51, no. 11, pp. 8399–8415, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10489-021-02389-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Z. Liang and P. Chen, “An automatic clustering algorithm based on the density-peak framework and chameleon method,” Pattern Recognit. Lett., vol. 150, no. 1, pp. 40–48, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.patrec.2021.06.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Y. Zhang, S. Ding, L. Wang, Y. Wang, and L. Ding, “Chameleon algorithm based on mutual k-nearest neighbors,” Appl. Intell., vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 2031–2044, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10489-020-01926-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. E. H. Walters, “Publication of complex dataset,” Thorax, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 368, 2003. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.368-a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. J. R. A. Jarvis and E. A. Patrick, “Clustering using a similarity measure based on shared near neighbors,” IEEE Trans. Comput., vol. C-22, no. 11, pp. 1025–1034, 1973. doi: 10.1109/T-C.1973.223640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. D. Cheng, Q. Zhu, J. Huang, L. Yang, and Q. Wu, “Natural neighbor-based clustering algorithm with local representatives,” Knowl. Based Syst., vol. 123, no. 317, pp. 238–253, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2017.02.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. L. Yang, Q. Zhu, J. Huang, and D. Cheng, “Adaptive edited natural neighbor algorithm,” Neurocomputing, vol. 230, no. 1, pp. 427–433, Oct. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2016.12.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. J. Huang, Q. Zhu, L. Yang, D. Cheng, and Q. Wu, “A non-parameter outlier detection algorithm based on natural neighbor,” Knowl. Based Syst., vol. 92, no. 3–4, pp. 71–77, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2015.10.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. D. Cheng, Q. Zhu, J. Huang, Q. Wu, and L. Yang, “A novel cluster validity index based on local cores,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 985–999, 2019. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2018.2853710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. N. X. Vinh, J. Epps, and J. Bailey, “Information theoretic measures for clustering’s comparison: Is a correction for chance necessary,” in Proc. 26th Annu. Int. Conf. Machine Learning, Montreal, Qc, Canada, 2009, pp. 1073–1080. doi: 10.1145/1553374.1553511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. S. Zhang, H. S. Wong, and Y. Shen, “Generalized adjusted rand indices for cluster ensembles,” Pattern Recognit., vol. 45, no. 9, pp. 2214–2226, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2011.11.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. M. Meila, “Comparing clusterings—an information based distance,” J. Multivar. Anal., vol. 98, no. 5, pp. 873–895, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jmva.2006.11.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools