Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Hidden Hierarchy Based on Cipher-Text Attribute Encryption for IoT Data Privacy in Cloud

1 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Altinbas University, Istanbul, Turkey

2 Department of Computer Engineering, Altinbas University, Istanbul, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Zaid Abdulsalam Ibrahim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2023, 76(1), 939-956. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2023.035798

Received 04 September 2022; Accepted 17 April 2023; Issue published 08 June 2023

Abstract

Most research works nowadays deal with real-time Internet of Things (IoT) data. However, with exponential data volume increases, organizations need help storing such humongous amounts of IoT data in cloud storage systems. Moreover, such systems create security issues while efficiently using IoT and Cloud Computing technologies. Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption (CP-ABE) has the potential to make IoT data more secure and reliable in various cloud storage services. Cloud-assisted IoTs suffer from two privacy issues: access policies (public) and super polynomial decryption times (attributed mainly to complex access structures). We have developed a CP-ABE scheme in alignment with a Hidden Hierarchy Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption (HH-CP-ABE) access structure embedded within two policies, i.e., public policy and sensitive policy. In this proposed scheme, information is only revealed when the user’s information is satisfactory to the public policy. Furthermore, the proposed scheme applies to resource-constrained devices already contracted tasks to trusted servers (especially encryption/decryption/searching). Implementing the method and keywords search resulted in higher access policy privacy and increased security. The new scheme introduces superior storage in comparison to existing systems (CP-ABE, H-CP-ABE), while also decreasing storage costs in HH-CP-ABE. Furthermore, a reduction in time for key generation can also be noted. Moreover, the scheme proved secure, even in handling IoT data threats in the Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) case.Keywords

In recent times, modern technological tools have powerfully shaped people’s lifestyles. Not only do people use technology to meet their basic needs like transportation, education, health care, they now enjoy the great convenience that the internet of things (IoT) offers through innovative applications [1], such as intelligent homes and innovative education tools. However, resource-constrained devices cannot effectively handle large data sets for localized operations. Consequently, a server storing data on the cloud must be securely integrated into an IoT network, encouraging an IoT cloud to deliver valuable services such as storage, processing and computation. Individuals and organizations use cloud services to store and process massive data [2] efficiently. Such services help enterprises reduce the cost of equipment and IT management [3,4]. Generally, cloud providers host cloud services. However, on the cloud, the data and services are open to all, so there is a risk of data loss. Hence, the minimum mandatory requirement of an access-control policy ensures authorized users access data securely. In [5] the authors recommend that data transfer is handled through Attribute-based Encryption (ABE), which helps make access control scalable and fine-grained on the cipher text. Moreover, it reduces the risk of data leakage and protects data by encrypting the data hosted on the cloud. For example, in healthcare management, the cipher text is used to outsource patient data via cloud channels by the hospitals, while doctors decrypt the data when needed for patient treatment; such cases are handled by Key Policy Attribute-based Encryption (KP-ABE) and Ciphertext Policy Attribute-based Encryption (CP-ABE) [6,7]. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 deals with the literature review, while Section 3 describes the main concepts, Section 4 provides a description of CP-ABE having a hierarchical hidden access structure. Section 5 illustrates the application process, and Section 6 applies to the medical environment. The results and discussion are presented in Section 7. Section 8 presented the complexity of the access policy. Finally, the concluding Section 9, sums up the work.

Along with generating the private key and access policy, the CP-ABE is a powerful mechanism to protect user information. This scheme only allows for decryption when the user attributes satisfy the access structure [2–8]. The privacy issues in policy get exposed in a basic CP-ABE scheme [9,10]. However, CP-ABE can have applications in the education, health care, and industrial fields. Using data encryption access policies in medical applications can disclose personal information. In [11], authors developed the initial CP-ABE system as a standard model, utilizing the AND gate. In [12] they proposed a non-pairing CP-ABE technique to enable access to AND gates. According to [13], CP-ABE is a hidden policy with entirely hidden attributes in access policies while creating a hidden access policy using Linear Secret Sharing Schemes (LSSS). Katz et al. [14] have developed a hidden policy approach with an access policy concealed as ciphertext. This approach employs the LSSS access structure and the hidden vector encryption method to check the attribute locations in an access policy. Though these approaches restrict access to the attribute in its entirety in the access policy, they have drawbacks such as increased computational complexity and false positive [15], & [8–15]. As presented in [16–19], some researchers developed partially hidden policies in CP-ABE. There are two phases to specify the attribute in the proposed schemes: the attribute name, and attribute values, with a hidden attribute value. Although this solution preserves the policy’s privacy to a certain level, it does not resolve privacy concerns [20,21]. However, only the restricted access structures, described as AND gates on multi-valued characteristics with wildcards, are supported by these schemes [22], suggesting a completely secure CP-ABE method with partial-concealed access structures stated in Linear Secret Sharing Scheme as LSSS, exhibiting greater flexibility and expression over earlier works [19–26]. Anyone accessing the ciphertext can get the following information about the access policy only if the data owner employs a CP-ABE scheme to encrypt his medical record under this updated paradigm:

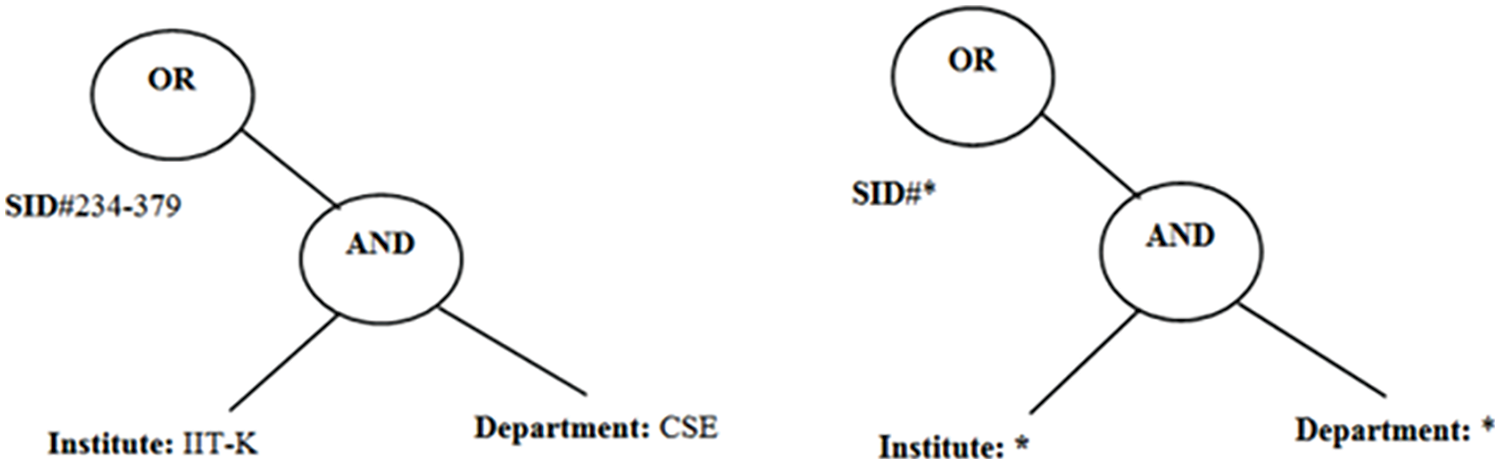

More significantly, sensitive attribute values, such as “234-379,” “AU,” and “SE,” do not appear in public. Fig. 1 shows a specimen with a partially hidden access structure.

Figure 1: Example of a student record with an access structure and sensitive access structure

Recent studies in [26] suggested a completely secure (as opposed to selectively safe) CP-ABE system using partially disguised access mechanisms. It should be noted, however, that their method enables only limited access structures, like [26–29]. The suggested technique is secure (CPA Attack), handling all access structures represented as Linear Secret Sharing Scheme (LSSS), with ciphertext sizes scaling in linear terms having access structure complications. Fig. 1 compares our CP-ABE system with previous CP-ABE methods based on disguised access structures. Another issue with previous CP-ABE systems [30–34] relates to the proportionate correlation between pairing frequency and exponentiation operations for ciphertext decryption and access policy complications, implying high user cost calculations [35]. This trait is appropriate for people who do not use smart mobile devices and decreases end-user computational overhead by performing cryptographic procedures when third-party service providers handle a significant computing burden [36].

This section describes the critical methods and concepts that support the Security mechanism, including Access Structure, Access Tree, and Bilinear Assumptions.

The set of entities to be denoted as

A, the access structure (a monotone set), including non-empty subsets of

The access structure represents the tree as

The threshold gate becomes the

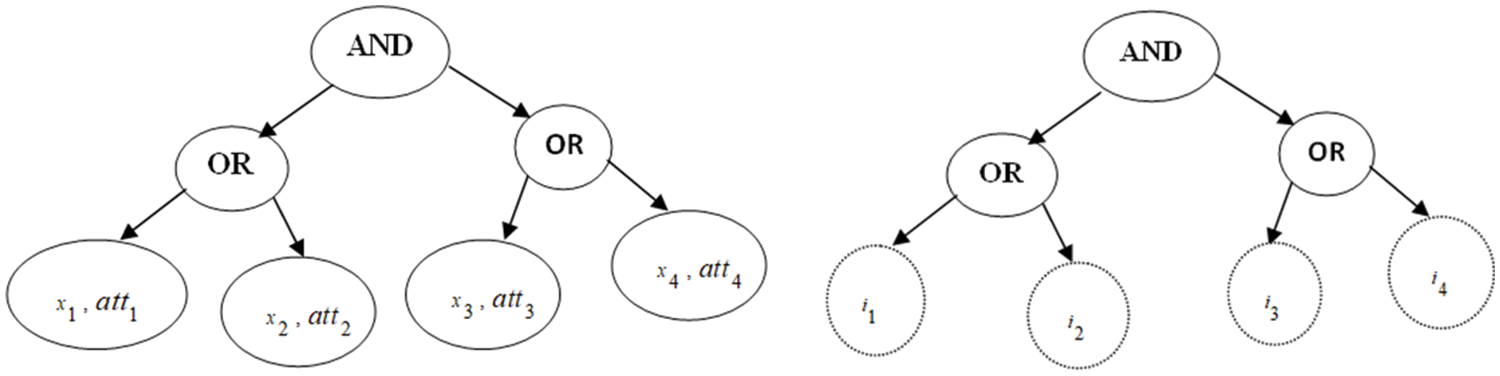

The attribute values, such as “234-379,” “AU,” and “SE,” are hidden and not exposed to anyone. A representation of the partially hidden policy is presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: (a) Access tree (b) access tree with hidden attribute

3.1.2 Access an Access Tree of HA (Hidden Attributes)

The given

3.2 Bilinear Map and Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) Assumption

Consider a set of multiplicative cyclic groups

3.2.2 Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) Assumption

The number of operations in both

Corresponding bilinear parameters

4 Proposed Methods Hidden Hierarchy Access Structure (HH-CP-ABE)

The proposed scheme contains system architecture, formal methods, and security models. The constructed model describes as follows:

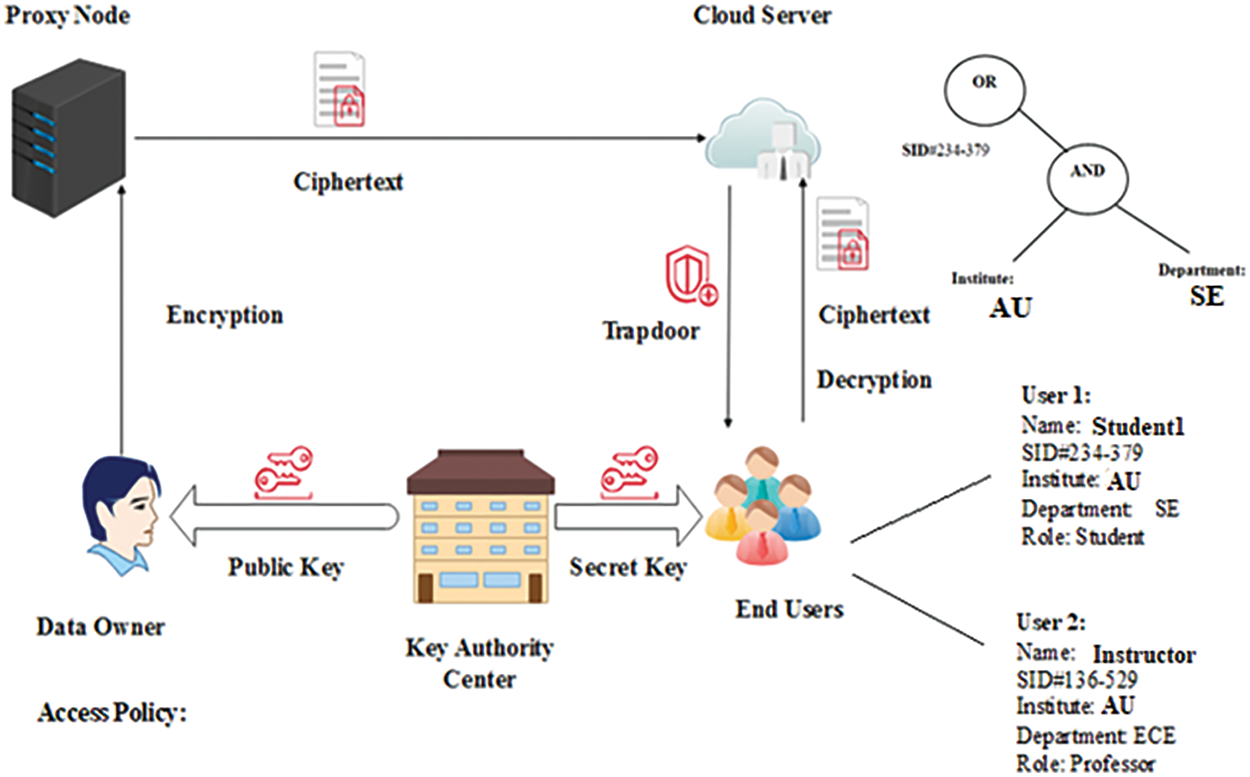

Fig. 3 illustrates the framework of the proposed system. The number of components in the structure includes (1) Key Authority Center (KAC), (2) Data Owner (DO), (3) Cloud Server (CS), (4) End User (EU), and (5) Proxy Node (PN).

Figure 3: Proposed system framework

• Trusted Key Authority Center (TKAC): The trusted authority generates public key besides the secret key.

• Data Owner (DO): An authorized owner who wishes to design the concerned access structure based on user attributes. Later, this is used to encrypt the desired ciphertext CT using proxy nodes.

• Cloud Server (CS): This campaign has a high capacity for computation and storage for extensive data processing. In addition, it allows the data owner and the end user to access such a massive capacity at the time of decryption.

• End User (EU): The trusted user initiates requests by submitting the trapdoor to the CS for ciphertext decryption.

• Proxy Node (PN): In this study, the computational overhead of encryption is outsourced from the DO to proxy nodes.

The proposed scheme uses four algorithms, as described below:

•

•

•

•

•

• Step1: The

• Step2: The condition

The suggested approach uses the security game between a Probabilistic Polynomial-Time (PPT) attacker and a challenger to achieve the desired plaintext security.

The proposed scheme accesses the Chosen Sensitive Policy Attack (CSPA) under the DBDH assumption by conducting a game (i.e., aPPT) between the adversary and the challenger.

5 Construction of Proposed Method: HH-CP-ABE

Let

•

The algorithm selects

•

•

• First,

From the above,

• Next,

• Next, PN generates

The

At final, DO

•

•

• Verification: The

• Case 1: From

• Case 2: The case in which

• Case 3:

Similarly, from

Therefore, by observing the results of the mentioned functions,

• Ciphertext Computation

•

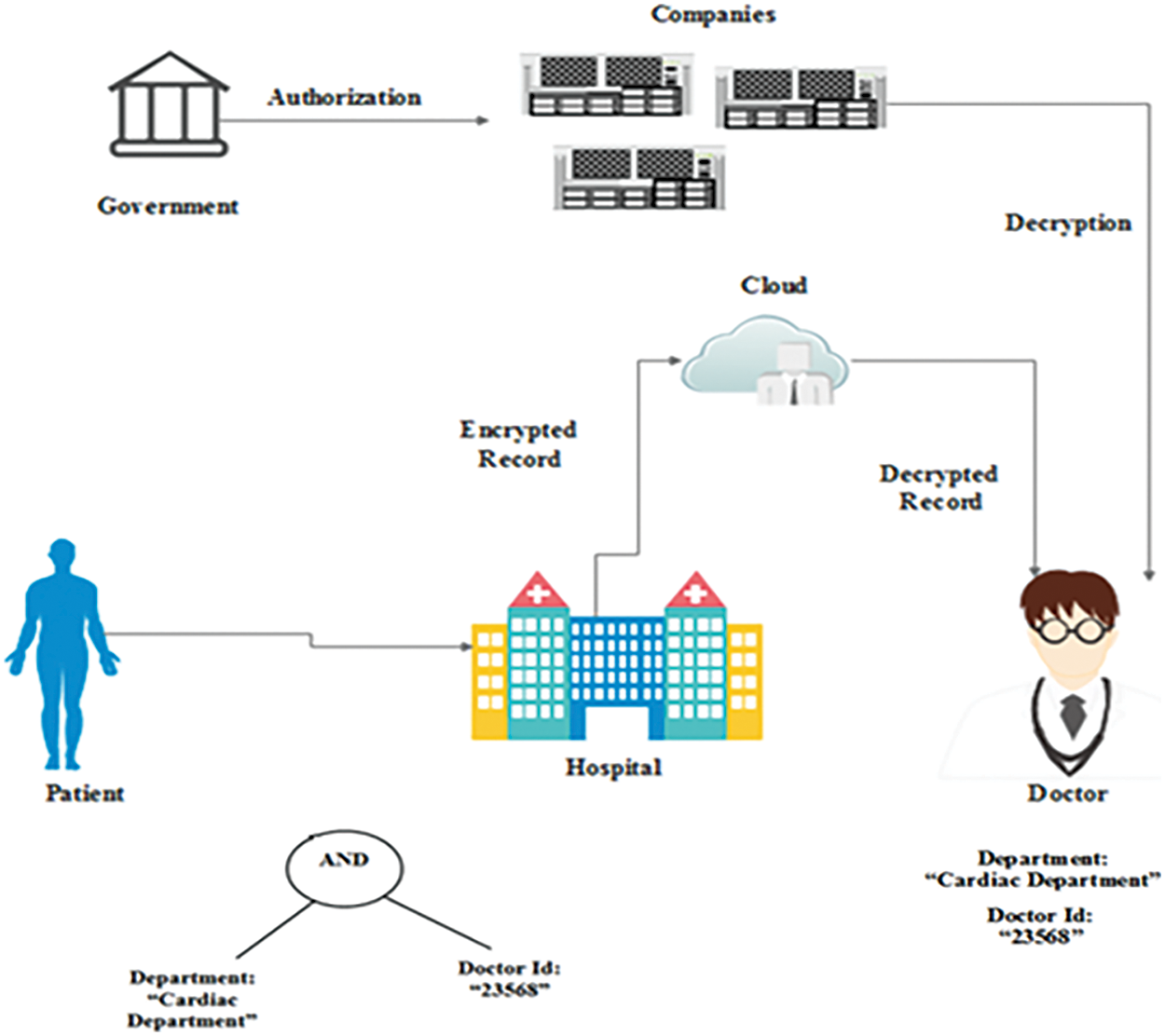

6 The IoT Embedded Medical Environment

The proposed system applies to the medical industry. The system is illustrated in Fig. 4, and the complete details are as follows:

Figure 4: Application in IoT embedded medical environment

The Trusted Key Authority Center (TKAC), the government, generates the public parameter Pk. The hospital is the data owner and maintains the patients’ records as PRec from IoT devices such as B-scan ultrasound machines, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) machines, and other instruments. Next, encryption is performed with the AS hidden access structure with the help of a trusted third party (a software company). Subsequently, the generated ciphertext CT is stored in the cloud server. Components that retain the access structure can prepare to access the data stored in the cloud.

A data user (clinician) accesses patient records from the cloud server by generating

The cloud server confirms the generated

Finally, the clinician performs decryption and receives the patient’s records.

The wrist of the dominant arm, the chest, and the ankle on the dominant side were covered by three wireless Colibri Inertial Measurement Units (IMU). Using the In.dat file format, the raw data could be accessed from sensors. Not a Number (NaN) was used to indicate missing values that resulted from issues with the hardware configurations (such as a loss of sensor connectivity). Each record in all subject data files includes the fields given below:

• Timestamp

• Activity ID

• Heart rate (bpm)

• IMU hand temperature (c)

• IMU hand 3D-acceleration (unit: ms−2, 13-bit resolution, 16 g scale)

• IMU hand 3D-acceleration (unit: ms−2, 6 g scale, 13-bit resolution)

• IMU hand 3D-gyroscope (unit: rad/s)

• IMU hand 3D-magnetometer (unit: T)

• IMU hand orientation

• IMU chest temperature (c)

• IMU chest 3D-acceleration (unit: ms−2, 13-bit resolution, 16 g scale)

• IMU chest 3D-acceleration (unit: ms−2, 6 g scale, 13-bit resolution)

• IMU chest 3D-gyroscope (unit: rad/s)

• IMU chest 3D-magnetometer (unit: T)

• IMU chest orientation

• IMU ankle temperature (c)

• IMU ankle 3D-acceleration (unit: ms−2, 13-bit resolution, 16 g scale)

• IMU ankle 3D-acceleration (unit: ms−2, 6 g scale, 13-bit resolution)

• IMU ankle 3D-gyroscope (unit: rad/s)

• IMU ankle 3D-magnetometer (unit: T)

• IMU ankle orientation

We have presented a framework for intelligent healthcare delivery that can be utilized to detect chronic diseases through remote monitoring, including cardiovascular disease, Tele-mammography, Teleophthalmology, asthma, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, dementia, blood pressure, and cognitive impairments.

In this work, features that may be used to measure an athlete’s activity status using IoT-based infrastructure that leverages linked sensors were partially extracted from the Physical Activity Monitoring Dataset (PAMAP2). The selected datasets have 3850505 entries in their vast repository [37] that reflect a total of 18 primary diverse physical activities.

Such planned activities include:

1. Lying down during idle time

2. Slouching on the sofa in comfort

3. Speaking in standing position

4. Pressing a few T-shirts

5. Vacuum Cleaning office spaces and shifting wares

6. Climbing five-storied buildings

7. Coming down five floors

8. Walking at a decent pace (4–6 km/h)

9. Nordic walking

10. Cycling on a real bike at a steady speed

11. Fast-paced Running

12. Basic Rope Jumping or alternate foot jump

13. Watching TV at home

14. Working on a computer in the office

15. Driving car crisscrossing office and home

16. Shelving Laundry

17. House Cleaning and dusting shelves

18. Kicking a soccer ball

Nine subjects—one female and eight males —with an average age of 27.22 years and a range of 3.31 years—performed the primary 18 tasks while wearing three sensors and a heart-rate monitor.

The proposed scheme implements the specifications: (1) A personal computer with a 3.4 GHz processor, (2) 8 GB RAM, and Ubuntu 16.04.

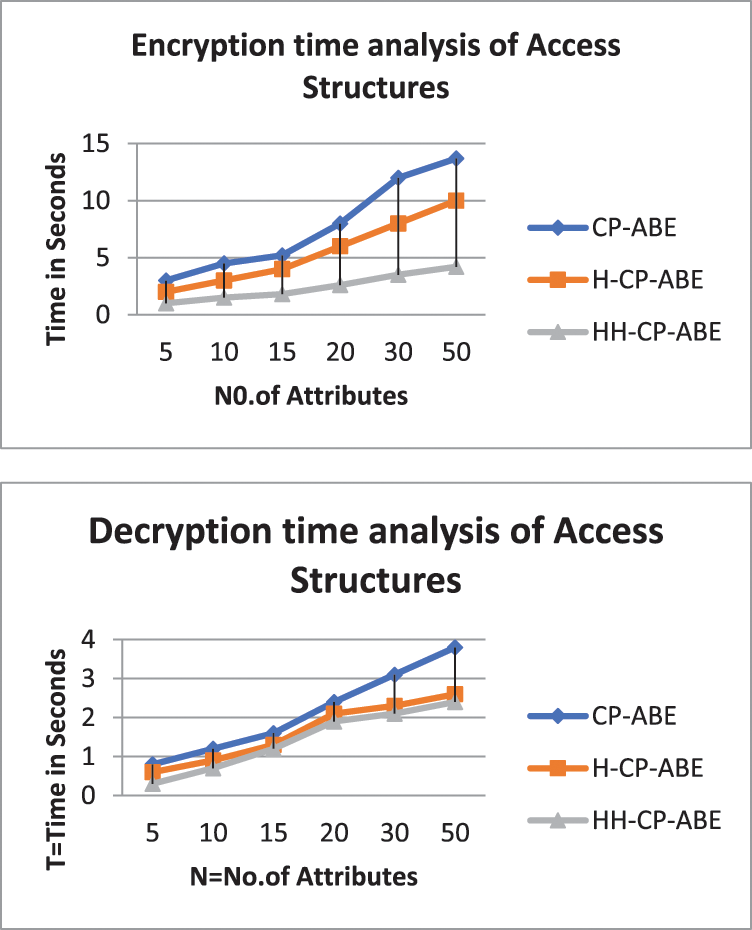

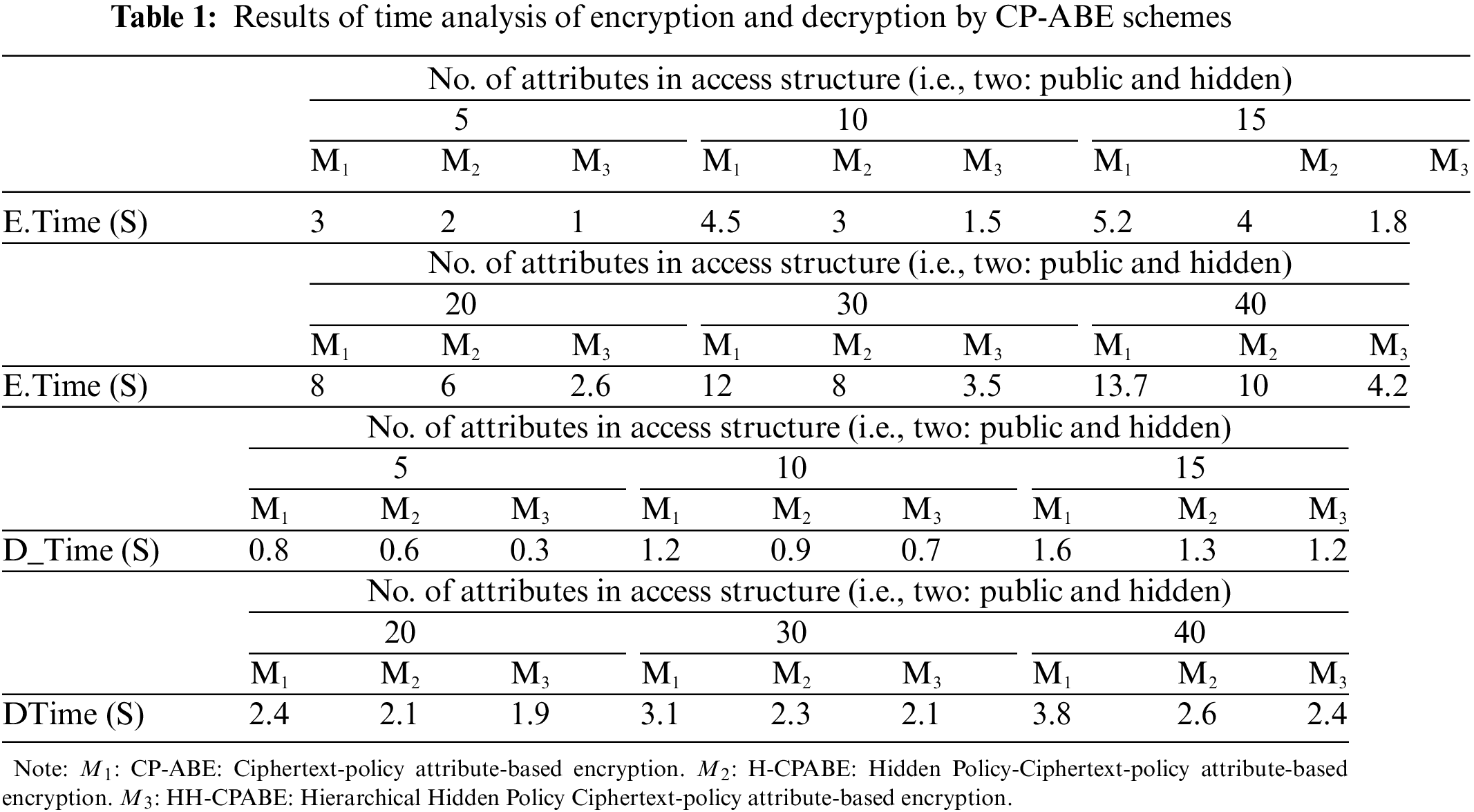

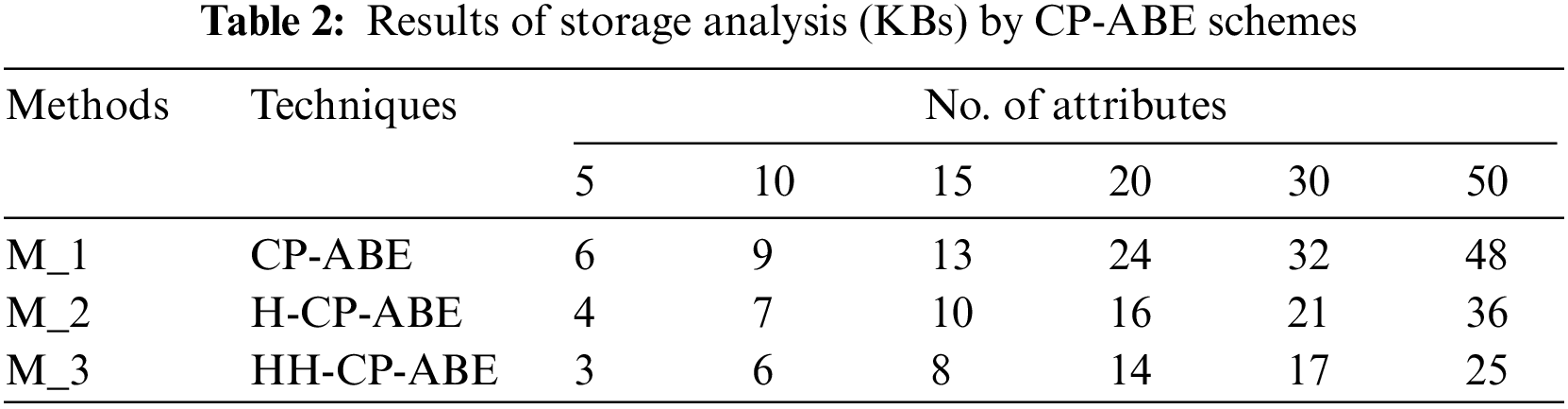

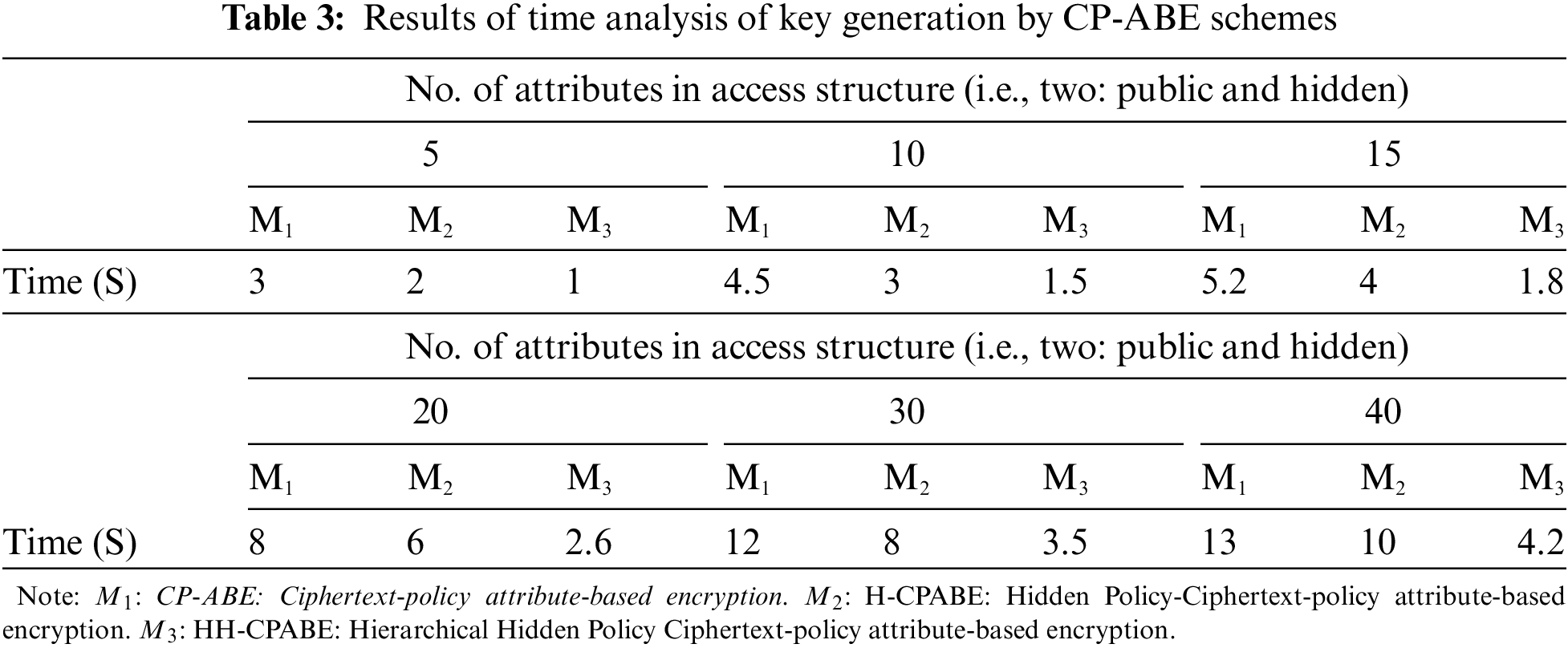

The complete results of the proposed system are clarified in Fig. 5 and Table 1. The total time required to complete encryption and decryption is shown in Fig. 5a. The storage costs related to the ciphertext for various attributes having Hidden Hierarchy (HH) data are shows in Fig. 5c. Moreover, the time and storage costs for different access structures with characteristics N = 30 are in Figs. 5b and 5d shown respectively.

Figure 5: Results analysis for CP-ABE schemes: (a) encryption time analysis of access structures (b) decryption time analysis of access structures (c) storage cost analysis of access structures (d) key generation time analysis of CP-ABE algorithms

Compared to other standard methods, the proposed scheme significantly improves the efficiency of encryption and decryption algorithms by reducing time. Moreover, it can be observed that the results show a significant linear relationship among the access structure attributes, as shown in Fig. 5a. The work in this scheme extends to several access structures, while the cost of encryption and decryption is low in HH-CP-ABE compared to the standard methods.

For example, in Fig. 5a, the cost of the encryption in HH-CP-ABE is 12 s compared to the previous systems (i.e., 8 and 3.5 s at N = 30). Similarly, at N = 50, the values are 13.7, 10, and 4.2 s. The increase in possible attributes in the respective access structures requires more time to perform the encryption times. Similarly, the decryption time reduction can be noticed in HH-CP-ABE compared to the existing systems; for example, in Fig. 5b the cost of decryption time in HH-CP-ABE is 3.1 s as contrasted to the current systems (2.3 and 2.1 s at N = 30). Also, at N = 50, the values are 3.8, 2.6, and 2.4 s.

Table 2 and Fig. 5c, show the proposed scheme has improved the storage cost efficiencies that decrease with two access structures, i.e., public and hidden. When this scheme is extended to several access structures, even adding more attributes, the storage capacity was significantly reduced by the HH-CP-ABE compared to the existing schemes. For example, in Fig. 5c, the storage cost in HH-CP-ABE is 17 KB compared to the existing systems (i.e., 21 and 32 KB at N = 30). Similarly, at N = 50, the values are 25, 36, and 48 KB. The increase in possible attributes in the respective access structures leads to better storage in the proposed scheme compared to the existing systems. Similarly, storage cost reduction can be noted in HH-CP-ABE as compared to the existing systems.

The study also focused on modifying an essential key generation time by different CP-ABE algorithms. From Table 3 and Fig. 5d the proposed HH-CP-ABE took less time to generate cipher text than all other standard techniques in all possible attributes.

The study also focused on modifying an essential key generation time by different CP-ABE algorithms. From Table 3 and Fig. 5d the proposed HH-CP-ABE took less time to generate cipher text than all other standard techniques in all possible attributes.

For example, in the case of the number of attributes at 30, the proposed method took only 3.5 s to generate the key. In contrast, the other two techniques run the same algorithm in 12 and 8 s. Similarly, when the number of attributes is 40, the proposed method took only 4.2 s to complete the key generation. In contrast, the existing methods ran 13 and 10 attributes, respectively, for key generation at the same time.

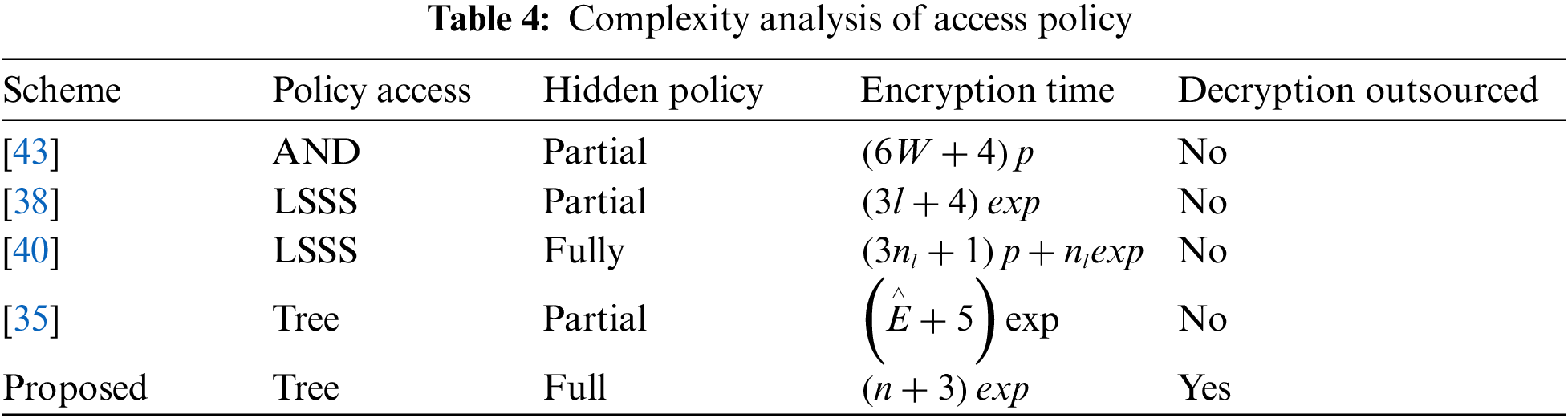

A comparative analysis of the computational tasks related to access policies between the suggested method and other standard methods is done in this section. Most existing schemes, however, are non-tree-based, such as AND-gate, OR-gate, and LSSS matrix access policies [38–43].

The proposed scheme depends on a tree-based access policy combining conjunctive and disjunctive typical forms. In other words, it refers to a tree in which every attribute holds two types of values, one public and another hidden. The corresponding access policy is defined as follows:

Further, all the non-tree-based schemes are seen producing Linear and Polynomial Cipher texts. It is also observed that these methods failed to perform decryption operations at outsourcing, thereby leading to higher computation. Also, it is observed that the proposed process takes a minimum amount of constant decryption time over the known schemes. Hence, our suggested approach best fits such resource-constrained devices, as shown in Table 4. Resource-constrained devices can completely outsource decryption tasks by adopting the proposed concept.

This work proposes a Hierarchy Hidden Policy Ciphertext-policy Attribute-Based Encryption (HH-CP-ABE) scheme having an essential key search function. It can handle access structures in a hierarchical or graded manner. The non-hierarchical structures are compatible with existing CP-ABE methods with partially hidden access structures. In addition, the proposed system is particularly suitable for resource-constrained devices, where some tasks (especially encryption/decryption/searching) typically outsource. The implementation of the work in this paper proves that it is possible to maintain the privacy of the access policy with a simple function like a keyword search. Moreover, the scheme also proves to be secure in handling IoT data threats in the presence of a Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH).

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to all those with whom we have enjoyed working on this and other related papers.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. F. Bonomi, R. Milito, J. Zhu and S. Addepalli, “Fog computing and its role in the internet of things,” in MCC. Association for Computing Machinery, Helsinki, Finland, pp. 13–16, 2012. [Google Scholar]

2. A. Sahai and B. Waters, “Fuzzy identity-based encryption,” in Springer EUROCRYPT. Conf. on Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Berlin, Heidelberg, German, pp. 457–473, 2005. [Google Scholar]

3. K. Lavanya, L. S. S. Reddy and B. Eswara, “Distributed based serial regression multiple imputation for high dimensional multivariate data in multicore environment of cloud,” International Journal of Ambient Computing and Intelligence, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 63–79, 2019. [Google Scholar]

4. G. V. Suresh and K. Lavanya, “An additive sparse logistic regularization method for cancer classification in microarray data,” The International Arab Journal of Information Technology, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 214–220, 2021. [Google Scholar]

5. V. Goyal, O. Pandey, A. Sahai and B. Waters, “Attribute-based encryption for fine-grained access control of encrypted data,” in CCS. Association for Computing Machinery, NY, USA, pp. 89–98, 2006. [Google Scholar]

6. S. Belguith, N. Kaaniche, A. Jemai, M. Laurent and R. Attia, “PAbAC: A privacy preserving attribute-based framework for fine grained access control in clouds,” in Security and Cryptography, Lisbon, Portugal, pp. 133–146, 2016. [Google Scholar]

7. Z. Cai, Z. He, X. Guan and Y. Li, “Collective data-sanitization for preventing sensitive information inference attacks in social networks,” Dependable and Secure Computing, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 577–590, 2018. [Google Scholar]

8. J. Bettencourt, A. Sahai and B. Waters, “Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption,” in IEEE S&P, Berkeley, CA, USA, pp. 321–334, 2007. [Google Scholar]

9. I. V. Božović, D. Socek, R. Steinwandt and V. I. Villányi, “Multiauthority attribute-based encryption with honest-but-curious central authority,” International Journal of Computer Mathematics, vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 268–283, 2012. [Google Scholar]

10. Z. Cai and X. Zheng, “A private and efficient mechanism for data uploading in smart cyber-physical systems,” Network Science and Engineering, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 766–775, 2020. [Google Scholar]

11. B. Waters, “Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption: An expressive, efficient, and provably secure realization,” Springer Public Key Cryptography, vol. 6571, pp. 53–70, 2011. [Google Scholar]

12. R. Xu, Y. Wang and B. Lang, “A tree-based CP-ABE scheme with hidden policy supporting secure data sharing in cloud computing,” in IEEE Int. Conf. on Advanced Cloud and Big Data, Nanjing, China, pp. 51–57, 2013. [Google Scholar]

13. T. Nishide, K. Yoneyama and K. Ohta, “Attribute-based encryption with partially hidden encryptor-specified access structures,” in Springer ACNS, New York, USA, pp. 111–129, 2008. [Google Scholar]

14. J. Katz, A. Sahai and B. Waters, “Predicate encryption supporting disjunctions, polynomial equations, and inner products,” in Springer EUROCRYPT Conf. on Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Istanbul, Turkey, pp. 146–162, 2008. [Google Scholar]

15. S. Yu, C. Wang, K. Ren and W. Lou, “Achieving secure, scalable, and fine-grained data access control in cloud computing,” in IEEE INFOCOM, San Diego, USA, pp. 534–542, 2010. [Google Scholar]

16. M. Green, S. Hohenberger and B. Waters, “Outsourcing the decryption of ABE ciphertexts,” in USENIX, San Francisco, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

17. B. Waters, “Functional encryption for regular languages,” in Springer CRYPTO Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Santa Barbara, USA, pp. 218–235, 2012. [Google Scholar]

18. A. B. Lewko and B. Waters, “Unbounded HIBE and attribute-based encryption,” in Springer EUROCRYPT Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Berlin, Heidelberg, German, pp. 547–567, 2011. [Google Scholar]

19. N. Attrapadung, “Dual system encryption via doubly selective security: Framework, fully secure functional encryption for regular languages, and more,” in Springer Annual Int. Conf. on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Berlin, Heidelberg, German, pp. 557–577, 2014. [Google Scholar]

20. C. Hu, N. Zhang, H. Li, X. Cheng and X. Liao, “Body area network security: A fuzzy attribute-based signcryption scheme,” Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 37–46, 2013. [Google Scholar]

21. M. Al-Qaraghuli, A. Saadaldeen and M. Ilyas, “Encrypted vehicular communication using wireless controller area network,” in Scientific Conf. of Electrical and Electronics Engineering Research, Basrah, Iraq, pp. 17–24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

22. A. R. Alabbas, L. A. Hassnawi, M. Ilyas, H. Pervaiz, Q. Abbasi et al., “Performance enhancement of safety message communication via designing dynamic power control mechanisms in vehicular ad hoc networks,” Computational Intelligence, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 1286–1308, 2020. [Google Scholar]

23. H. M. Marah, J. R. Khalil, A. Elarabi and M. Ilyas, “DMVPN network performance based on dynamic routing protocols and basic IPsec encryption,” in IEEE Int. Conf. on Electrical, Communication, and Computer Engineering, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, pp. 1–5, 2021. [Google Scholar]

24. H. Al-Khshali, M. Ilyas and O. Ucan, “Effect of PE file header features on accuracy,” in IEEE Symp. Series on Computational Intelligence, Canberra, Australia, pp. 1115–1120, 2020. [Google Scholar]

25. M. Al-Saadi and M. Ilyas, “Identity management approach in internet of things (IoT),” in 2020 IEEE Int. Symp. on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies, Istanbul, Turkey, pp. 1–6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

26. Y. Rouselakis and B. Waters, “Practical constructions and new proof methods for large universe attribute-based encryption,” in Proc. of the ACM SIGSAC Conf. on Computer & Communications Security, Berlin, Germen, pp. 463–474, 2013. [Google Scholar]

27. Q. Li, H. Zhu, Z. Ying and T. Zhang, “Traceable cipher text policy attribute-based encryption with verifiable outsourced decryption in eHealth cloud,” Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, vol. 2018, pp. 12, 2018. [Google Scholar]

28. H. Zhong, W. Zhu, Y. Xu and J. Cui, “Multi-authority attribute-based encryption access control scheme with policy hidden for cloud storage,” Soft Computing, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 243–251, 2018. [Google Scholar]

29. S. Belguith, N. Kaaniche, A. Jemai, M. Laurent and R. Attia, “PAbAC: A privacy preserving attribute-based framework for fine grained access control in clouds,” in 13th IEEE Int. Conf. on Security and Cryptography (Secrypt), Setubal, Portugal, pp. 133–146, 2016. [Google Scholar]

30. J. He and E. Dawson, “Multisecret-sharing scheme based on one-way function,” Electronics Letters, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 93–95, 1995. [Google Scholar]

31. L. Harn, “Multistage secret sharing based on one-way function,” Electronics Letters, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 262, 1995. [Google Scholar]

32. T. V. X. Phuong, G. Yang and W. Susilo, “Hidden ciphertext policy attribute-based encryption under standard assumptions,” Information Forensics and Security, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 35–45, 2016. [Google Scholar]

33. F. Han, J. Qin, H. Zhao and J. Hu, “A general transformation from KP-ABE to searchable encryption,” Future Generation Computer System, vol. 30, pp. 107–115, 2014. [Google Scholar]

34. S. Jalwa, V. Sharma, A. R. Siddiqi, I. Gupta and A. K. Singh, “Comprehensive and comparative analysis of different files using CP-ABE,” in Advances in Communication and Computational Technology. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering. Singapore: Springer, pp. 189–198, 2021. [Google Scholar]

35. F. Guo, W. Susilo, D. S. Wong and V. Varadharajan, “CP-ABE with constant-size keys for lightweight devices,” IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 763–771, 2014. [Google Scholar]

36. S. Gusmeroli, S. Piccione and D. Rotondi, “A capability-based security approach to manage access control in the internet of things,” Mathematical and Computer Modeling, vol. 58, no. 5–6, pp. 1189–1205, 2013. [Google Scholar]

37. A. Reiss and D. Stricker, “Introducing a new benchmarked dataset for activity monitoring,” in IEEE Int. Symp. on Wearable Computers, UK, Newcastle, pp. 108–109, 2012. [Google Scholar]

38. J. Lai, R. H. Deng and Y. Li, “Expressive CP-ABE with partially hidden access structures,” in Proc. of ACM Symp. on Information, Computer and Communications Security, NY, USA, pp. 18–19, 2012. [Google Scholar]

39. N. Helil and K. Rahman, “CP-ABE access control scheme for sensitive data set constraint with hidden access policy and constraint policy,” Security and Communication Networks, vol. 2017, no. 6, pp. 1–13, 2017. [Google Scholar]

40. K. Yang, Q. Han, H. Li, K. Zheng, Z. Su et al., “An efficient and fine-grained big data access control scheme with privacy preserving policy,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 563–571, 2017. [Google Scholar]

41. D. Boneh and B. Waters, “Conjunctive, subset, and range queries on encrypted data,” in Spring Theory of Cryptography Conf., Berlin, Heidelberg, German, pp. 535–554, 2007. [Google Scholar]

42. J. Lai, R. H. Deng and Y. Li, “Fully secure cipertext-policy hiding CP-ABE,” in ISPEC. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Berlin, Heidelberg, German, pp. 24–39, 2011. [Google Scholar]

43. F. Khan, L. Hui, Z. Liangxuuan and S. Jian, “An expressive hidden access policy CP-ABE,” in IEEE Second Int. Conf. on Data Science in Cyberspace (DSC), Shenzhen, China, pp. 178–186, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools