DOI:10.32604/cmc.2022.023639

| Computers, Materials & Continua DOI:10.32604/cmc.2022.023639 |  |

| Article |

Energy-Efficient Scheduling for a Cognitive IoT-Based Early Warning System

1Department of Electronics Engineering, Korea Polytechnic University, Siheung, 15073, Korea

2Mirpur University of Science and Technology, Mirpur, 10250, Pakistan

3Department of Electronics, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, 25120, Pakistan

4Sarhad University of Science and Information Technology, Peshawar, 25000, Pakistan

*Corresponding Author: Su Min Kim. Email: suminkim@kpu.ac.kr

Received: 15 September 2021; Accepted: 05 November 2021

Abstract: Flash floods are deemed the most fatal and disastrous natural hazards globally due to their prompt onset that requires a short prime time for emergency response. Cognitive Internet of things (CIoT) technologies including inherent characteristics of cognitive radio (CR) are potential candidates to develop a monitoring and early warning system (MEWS) that helps in efficiently utilizing the short response time to save lives during flash floods. However, most CIoT devices are battery-limited and thus, it reduces the lifetime of the MEWS. To tackle these problems, we propose a CIoT-based MEWS to slash the fatalities of flash floods. To extend the lifetime of the MEWS by conserving the limited battery energy of CIoT sensors, we formulate a resource assignment problem for maximizing energy efficiency. To solve the problem, at first, we devise a polynomial-time heuristic energy-efficient scheduler (EES-1). However, its performance can be unsatisfactory since it requires an exhaustive search to find local optimum values without consideration of the overall network energy efficiency. To enhance the energy efficiency of the proposed EES-1 scheme, we additionally formulate an optimization problem based on a maximum weight matching bipartite graph. Then, we additionally propose a Hungarian algorithm-based energy-efficient scheduler (EES-2), solvable in polynomial time. The simulation results show that the proposed EES-2 scheme achieves considerably high energy efficiency in the CIoT-based MEWS, leading to the extended lifetime of the MEWS without loss of throughput performance.

Keywords: Flash floods; internet of things; cognitive radio; early warning system; network lifetime; energy efficiency

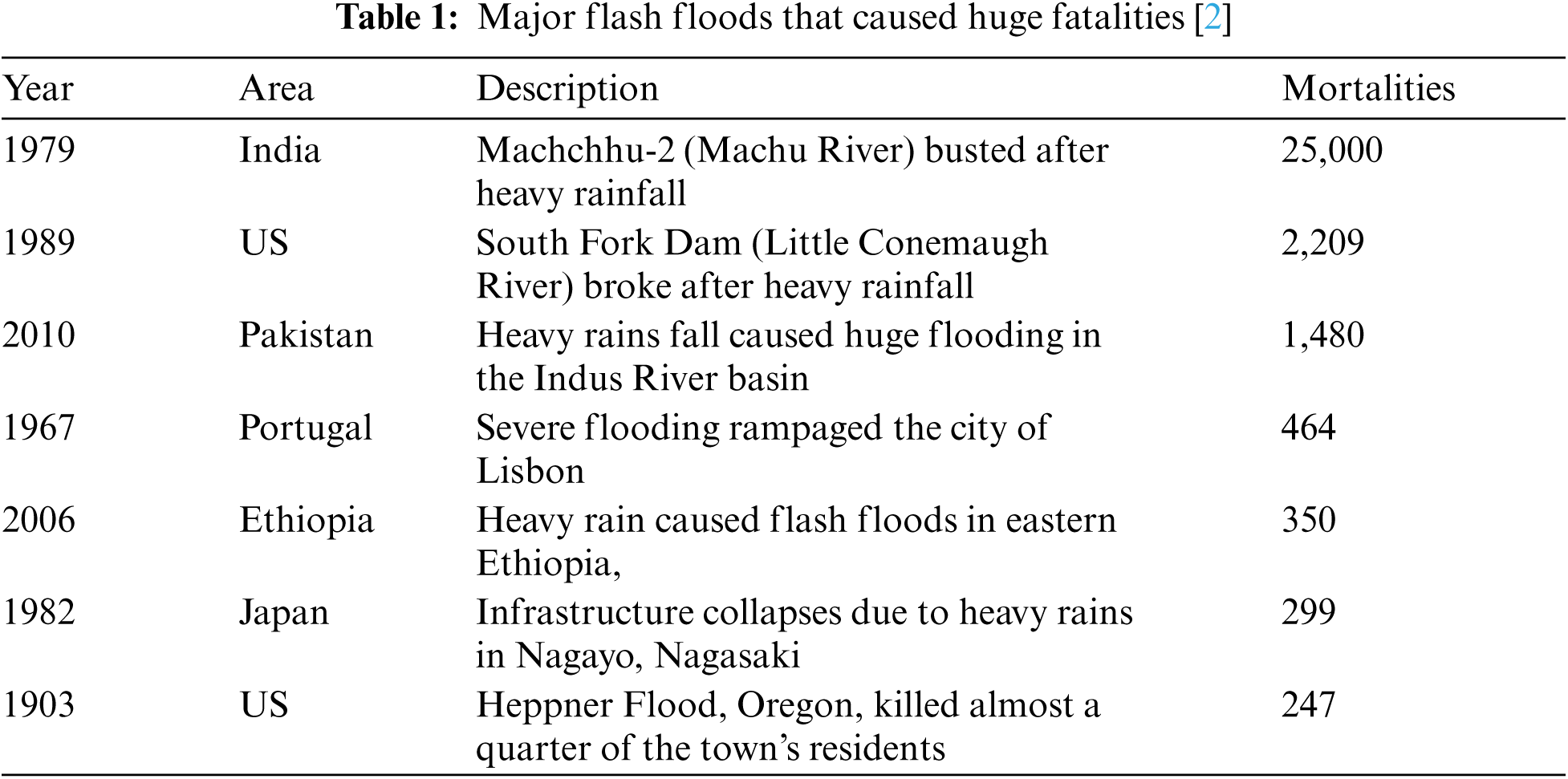

Global warming at alarming levels is stimulating a wide variety of factors that cause flash floods [1]. Flash floods are considered the most fatal types of floods due to their high mortality rate as shown in Tab. 1. Excessive rainfall, dam failure, or a sudden release of water held by glacier jam may result in a flash flood. Rapidly rising water can reach heights of 30 feet or more. Flash floods can roll rocks, tear out trees, obliterate structures and overpasses, and scrub out new water channels. Furthermore, flash flood-producing rains may incite catastrophic mudslides. Occasionally, the floating debris or ice accumulates at a natural or man-made barricade, resulting in the rise of water level upstream. On the abrupt release of the obstruction, the wreckage carried by an excessive volume of water triggers astringent damage to the life and property downstream. In such situations, there is a fleeting time to caution the populace about sudden floods.

The characteristics of cognitive radio (CR) and the Internet of things (IoT) can be exploited to achieve a short response time during flash floods. The IoT is a technological revolution that brings us into a new era of pervasive connectivity, computing, and communication. The evolved idea of IoT is to develop intelligent physical objects to sense, communicate, process, and act for concerted decisions, entailing a new paradigm named cognitive Internet of Things (CIoT) [3]. The IoT devices and networks are anticipated for reliability, quality, and time enduring availability. Connectivity is considered the most critical component in the realization of the concept of IoT. Wireless communication technologies emerge as a cost-effective solution to provide essential inter-connectivity among IoT devices and accessibility to remote users [4,5].

Radio spectrum scarcity has emerged as one of the major challenges due to the unprecedented growth of IoT devices [4,6,7]. The studies reveal that incorporation of the CR capability into IoT devices and networks substantially improves spectral efficiency by using dynamic spectrum access (DSA) and opportunistic transmission capabilities [3,4,6]. They also suggest that the benefits of IoT without cognitive functionalities such as CR and intelligence techniques are limited [4]. Moreover, the integration of CR into IoT can provide advanced information processing capabilities.

On the other hand, CR requires a powerful energy source to perform its functionalities. However, the current battery technologies cannot meet the higher power requirements related to the flow of data generated by CIoT devices, due to slower progress in battery technologies compared to semiconductor technologies [8]. Hence, efficient utilization of the CIoT network to develop an early warning system for flash floods becomes vital to save lives and reduce the devastating impacts of natural hazards [9]. Consequently, flash flood monitoring requires a CIoT network deployment over a wide range of geographical areas without frequent battery replacement. In addition, efficient utilization of battery energy for CIoT devices is crucial in network design. It can provide cost-effectiveness and extended network lifetime as well as reduced environmental concerns.

The international strategy for disaster reduction (ISDR) has laid down outlines to devise measures for minimizing the damages caused by floods and other disasters. These measures are classified as: 1) structural and 2) non-structural [10,11]. The structural measures include the engineering construction design of physical structures to reduce potential impacts of hazards such as protection, retention, and drainage systems involving huge time and economic resources [10]. On the other hand, the non-structural measures employ data or policies to reduce the risk [10–12]. These are further classified as passive and active measures.

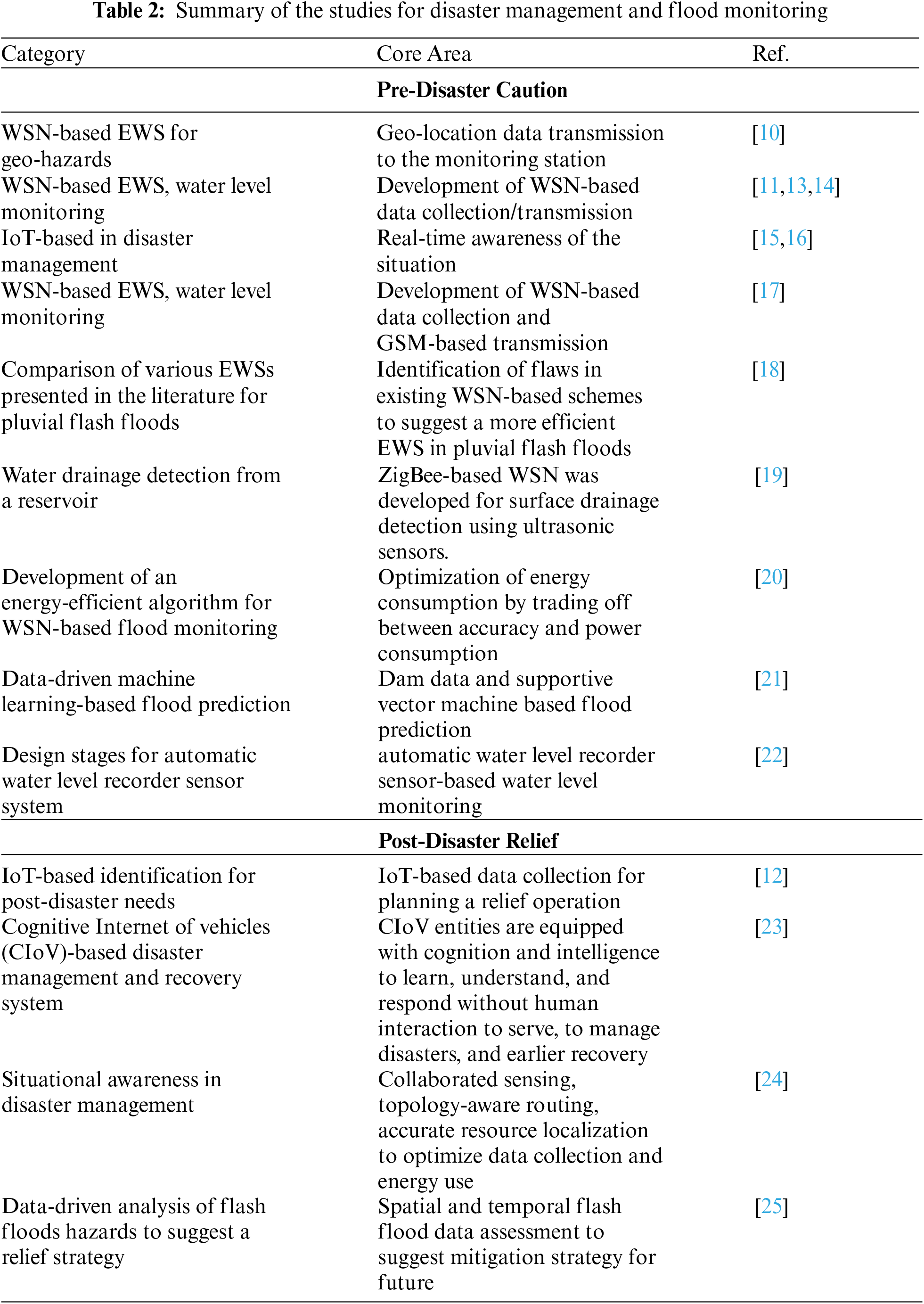

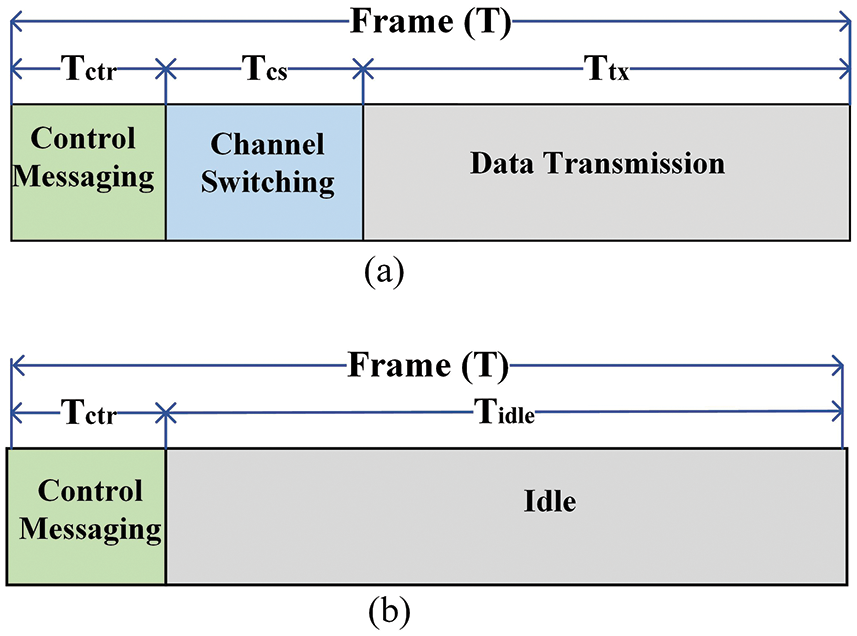

The active measures promote direct interactions with people such as training, early warning systems (EWSs) for people, and public information, among others. The passive measures involve policies, building codes and standards, and land use regulations. In this paper, we consider the non-structural passive measures for our proposed CIoT-based EWS. A summary of the non-structural studies related to IoT-enabled disaster management is listed in Tab. 2. However, these previous studies generally take into account legacy wireless sensor networks at an abstract level. Moreover, they do not aim to extend the network lifetime through efficient utilization of the limited battery energy.

The implementation of state-of-the-art technologies such as CR and IoT have been investigated to mitigate the vulnerabilities of flash floods [12–14,22]. The state-of-the-art CIoT networks are expected to operate multiple cognitive and intelligent functionalities to minimize the loss of lives and assets under disastrous situations and higher power requirements. However, since the CIoT networks involve several battery-limited devices, efficient energy utilization is required and it has three main objectives: 1) cost-effectiveness, 2) longer battery lifetime, and 3) environmental concerns.

The energy efficiency in resource allocation is well investigated in the literature. Kim et al. studied the scheduling for IoT devices to enter them into sleep and active modes to prolong the network lifetime while satisfying the report accuracy and timely-update requirements for environmental monitoring applications at higher network levels [26]. Sarangi et al. proposed several schemes to minimize the energy consumption between neighboring IoT nodes and servers at the network layer [27]. In [28], Bui et al. proposed a scheduling scheme for software updates of IoT devices to minimize total energy consumption while satisfying the deadline constraint for updating all the IoT devices. In [29], Afzal et al. presented a context-aware traffic scheduling algorithm to allocate resources to multi-hop IoT devices and reduce their total awake time by employing adaptive duty cycling at a higher network layer. Yu et al. [30] formulated an energy consumption minimization problem considering offloading, user association, and small base station sleeping for network-wide devices and components. Kaur et al. [31] proposed a deep-reinforcement-learning (DRL)-based intelligent routing scheme for a clustered divided IoT-enabled wireless sensor network (WSN) to reduce the network delay and increase network lifetime. However, the previous work mainly focuses on the energy consumption minimization at the network layer, e.g., routing. Most recently, In [32], Verma et al. investigated the energy efficiency of a clustered IoT-based WSN to save battery energy through scheduling the selection of a cluster head and controlling the sleep mode of IoT sensor devices.

1.2 Contribution and Organization

Contrary to the studies mentioned above, in this paper, we propose CIoT-based monitoring and early warning system (MEWS) to reduce the devastation of flash floods. The proposed system model considers the characteristics of CR to develop a clustered CIoT sensor network over a wide range of geographical areas. The network lifetime of the MEWS can be increased through a suitable selection of communication channels for reporting the data collected by the CIoT sensors. To save the limited battery energy of CIoT devices, we formulate an energy efficiency maximization problem based on nonlinear integer programming (NLP). To solve this problem, we propose two polynomial-time heuristic scheduling schemes.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the CIoT-based system model considered in this paper. The optimization problem formulation and the proposed heuristic scheduling algorithms are presented in Section 3. The performance of the proposed scheduling schemes is evaluated in terms of energy consumption, normalized energy efficiency, the average number of available reports, and network throughput in Section 4. Discussions and conclusions are presented in Section 5 with the intended future work.

Fig. 1 shows the bi-level MEWS. At Level-1, CIoT sensors are deployed in water channels and canyons to measure different flood-related parameters, such as water level, intensity, pressure, temperature, etc. The CIoT sensors report their observations as fixed-size packets to the smart base station (SBS) after getting the channel allocation map from SBS. At Level-2, the SBS forwards the collected data to the flood management system on a high-speed link. The flood management system employed at the disaster management center (DMC), analyzes the data to take preventive measures while a flash flood is detected. The SBS plays a role as the cluster gateway and is responsible for allocating sub-channels to the CIoT sensors.

Figure 1: CIoT-based flash flood monitoring and early warning system

We consider a clustered architecture serving

In this paper, spectrum sensing is not performed, assuming that the spectrum occupancy of primary users (PUs) is obtained by the SBS from a white space database which is fully synchronized with the PN [33]. Such database-based CR systems have attained notable attention due to their immense potential for transmuting CRs into functional networks [33,34]. The channel idle probability is denoted as

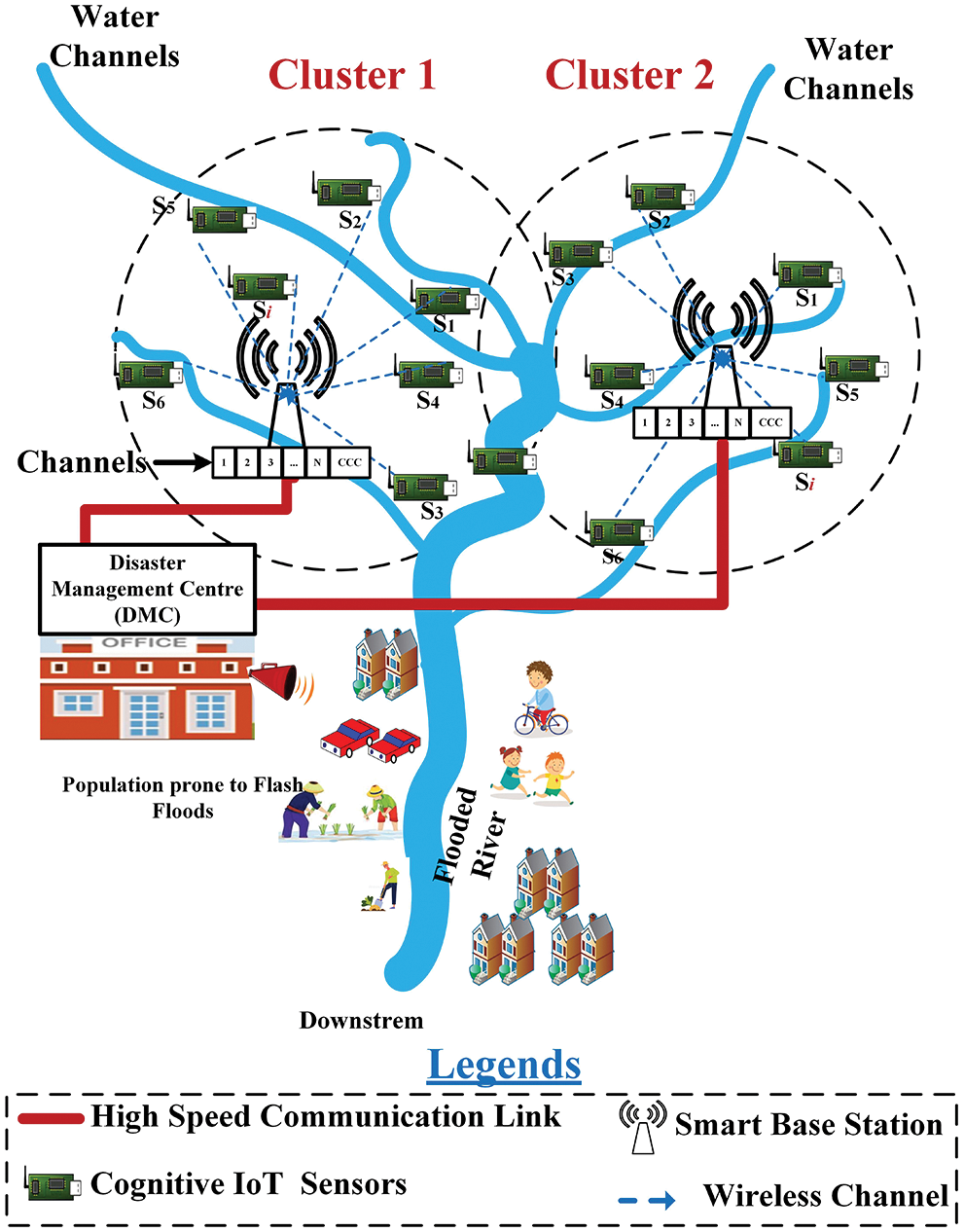

Figure 2: Frame structure of the proposed scheduling schemes: (a) frame structure of CIoT sensors when the sub-channels are allocated by the SBS, (b) frame structure of CIoT sensors when the sub-channels are not allocated by the SBS

The maximum number of bits that a single CIoT sensor can transmit in a frame over the channel depends on three factors: 1) bandwidth of the channel, W, 2) signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR), and 3) channel switching delay. The switching delay

where

where

where T,

where

2.1.1 Transmission Mode—Energy Consumption Modeling

Let

In this subsection, we derive the energy consumption of a CIoT sensor during different time durations in a single frame. At the beginning of the frame, each CIoT sensor sends its state to the SBS during the control messasing period, consuming the amount of energy

We assume that the CIoT sensors use maximum transmission power

where

Transmission energy consumption is proportional to the transmission time duration and the assigned transmission power

Accordingly, the energy consumption during data transmission for the i-th CIoT sensor on the j-th sub-channel can be calculated as follows:

The power consumed by the electric circuitry within the CIoT sensor in transmission mode, named circuit power, is defined as

Eventually, the total energy consumption for the i-th CIoT sensor on the j-th sub-channel in the transmission mode scenario is obtained by adding Eqs. (5), (6), (8), and (9) as follows:

2.2 Idle Mode--Energy Consumption Modeling

If no sub-channel is assigned to a CIoT sensor by the SBS in a frame, the corresponding CIoT sensor goes into the idle state after the control messaging time duration. Energy consumption for the idle CIoT sensor is the sum of the amount of energy consumed in control messaging and consumed during idle period. The length of the idle period is

Consequently, the total energy consumption for a single frame in a CIoT sensor network is derived by

In Eq. (12), the first term represents the energy consumptions by active CIoT sensors, while the second term denotes those by idle CIoT sensors in the network.

3 Problem Formulation and Proposed Scheduling Schemes

Energy efficiency can be defined as the throughput achieved per unit energy consumed in a given frame time duration, T, as bits per joule [38]. Dividing Eq. (4) by Eq. (12), we obtain the energy efficiency of a CIoT sensor network as follows:

Subsequently, we formulate an energy efficiency maximization problem as follows:

where

At the beginning of each frame, it is required that the SBS solves the problem and disseminates the assignment decision to all the CIoT sensors. Then, the CIoT sensors start to transmit the collected data over the assigned sub-channels. Since the SBS determines the channel assignment at the beginning of each frame, an efficient scheduling scheme is needed in the perspective of energy consumption and complexity. In this paper, the optimal solution can be found for only a small number of available idle sub-channels and CIoT sensors through exhaustive search. However, in general, since several CIoT sensors and available idle sub-channels exist in the CIoT network, a more efficient and tractable scheduling scheme is required. In the next subsections, we propose two energy-efficient scheduling schemes: energy-efficient scheduler-1 (EES-1) and energy-efficient scheduler-2 (EES-2).

3.1 Proposed Energy Efficient Scheduler-1

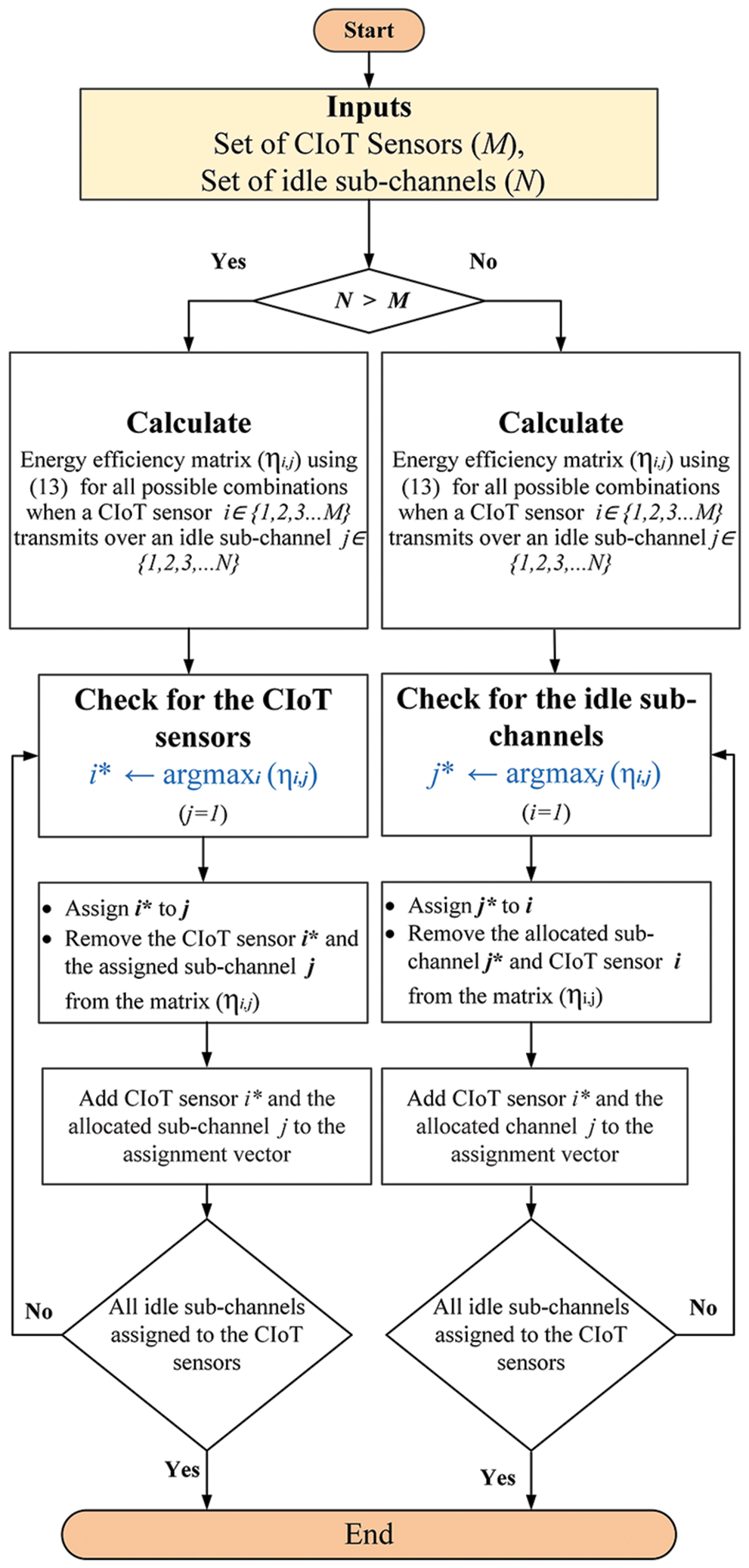

Fig. 3 shows the flowchart of the proposed EES-1 scheme. It greedily assigns an idle sub-channel to a CIoT sensor so that it maximizes the energy efficiency on the sub-channel. The energy efficiency matrix is calculated using Eq. (12). If the available number of idle sub-channels is larger than the number of CIoT sensors, the proposed EES-1 scheduler searches for the best CIoT sensor for a given sub-channel to maximize the energy efficiency value. Afterward, the CIoT sensor and the assigned sub-channel are removed from the search space in the energy efficiency matrix and placed in the assignment matrix. The loop continues until all the available idle sub-channels are assigned to the CIoT sensors. On the other hand, if the number of CIoT sensors is larger than the number of available idle sub-channels, the proposed EES-1 scheduler searches for the best sub-channel for a given CIoT sensor to maximize the energy efficiency. Afterward, the selected CIoT sensor and the assigned sub-channel are removed from the energy efficiency matrix and placed in the assignment matrix. The same procedure is iteratively performed until all the CIoT sensors are assigned to the idle sub-channels.

The proposed EES-1 scheme operates in polynomial time for a certain number of available idle sub-channels. More specifically, its complexity is given by the order of

Figure 3: Flowchart of the proposed EES-1 scheme

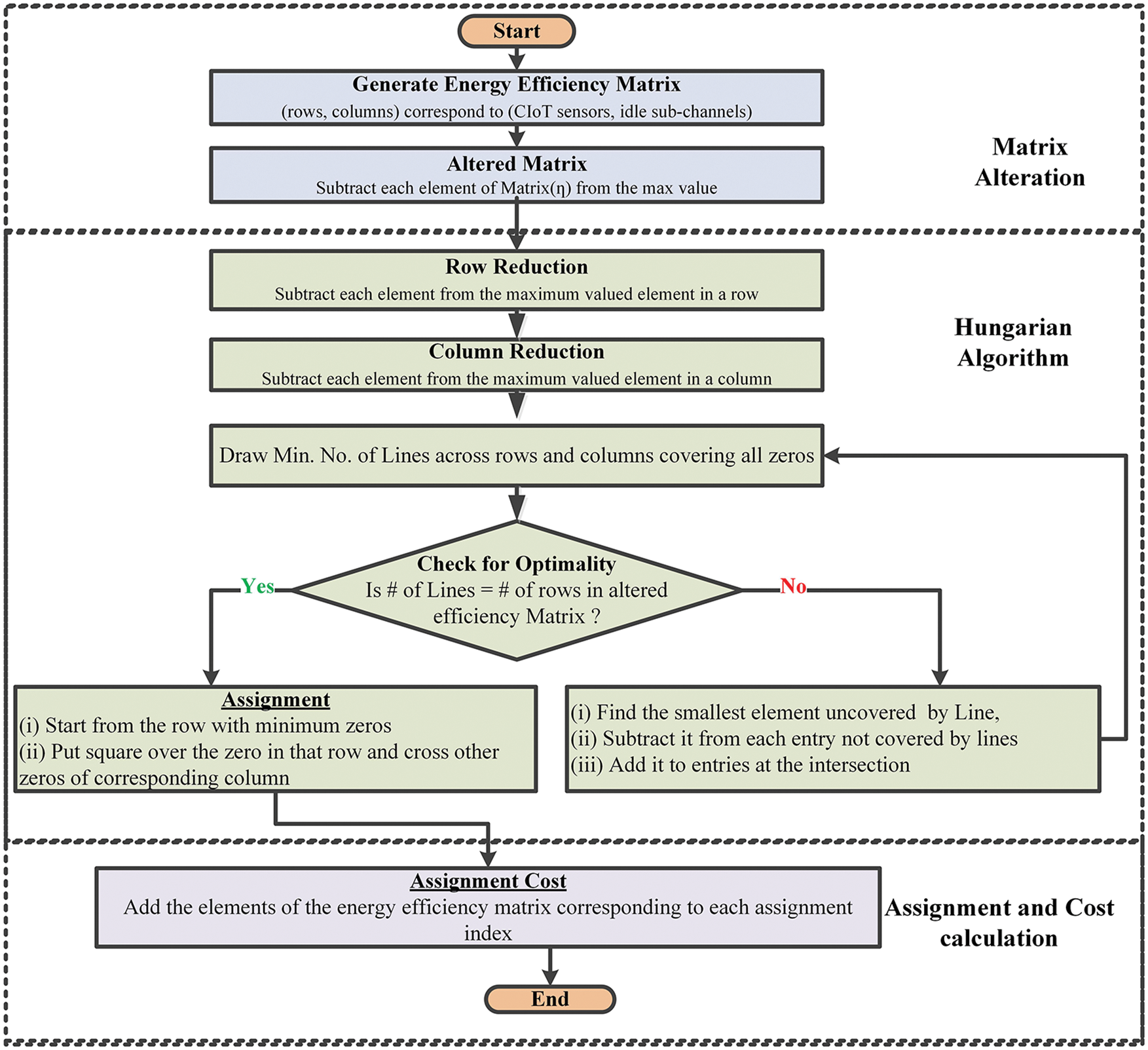

3.2 Proposed Energy Efficient Scheduler-2

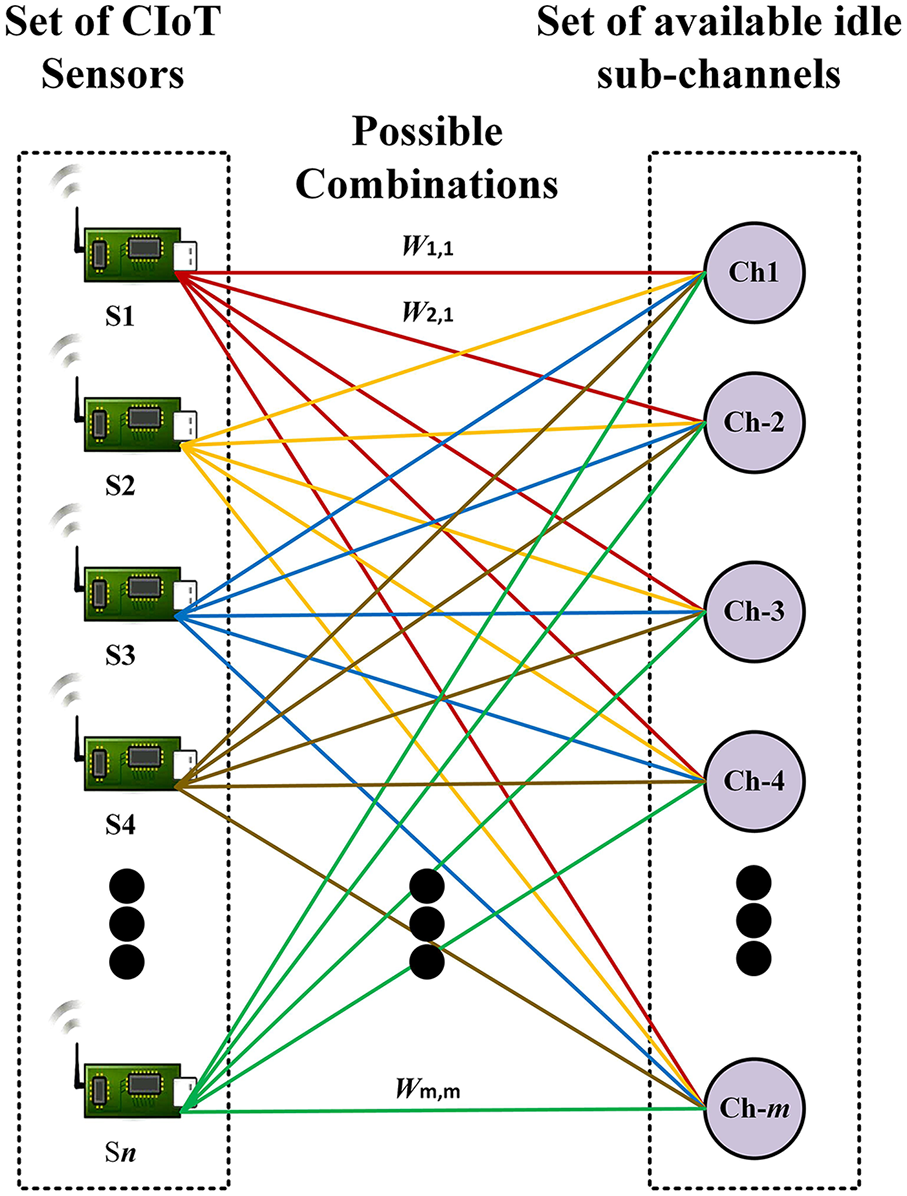

We model the channel assignment problem using a weighted bipartite graph by placing the CIoT sensors in a group of vertices,

Figure 4: Bipartite graph representation for the energy efficiency maximization problem

Figure 5: Flow chart of the proposed EES-2 scheme

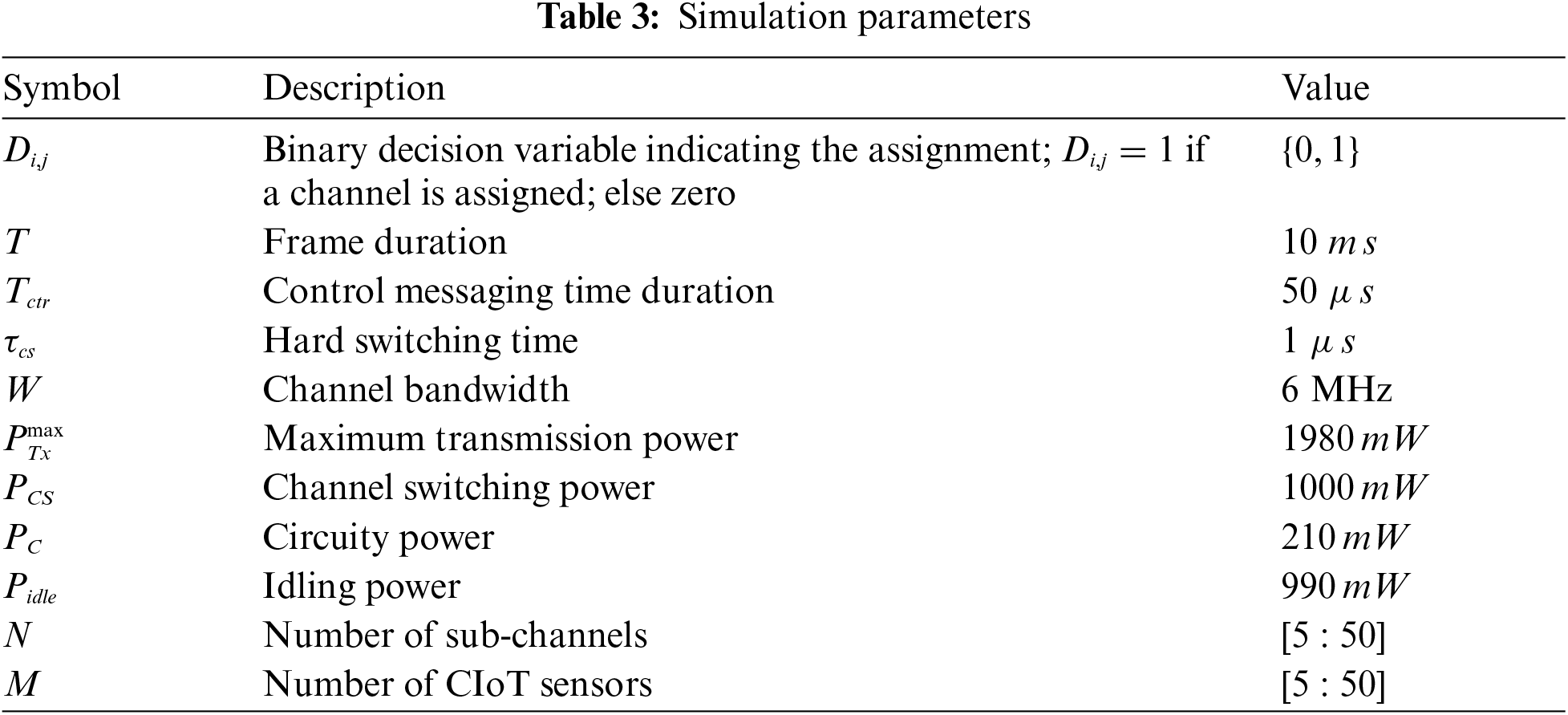

In this section, we evaluate the proposed EES-1 and EES-2 schemes through extensive simulations. As the basic performance metrics, we consider energy consumption, the average number of available reports, normalized energy efficiency, and network throughput. A random scheduler (RS), in which the idle sub-channels are randomly assigned to the CIoT sensors, is taken into account as a benchmark scheme. For simplification of the analysis, we consider a contiguous spectrum scenario with sub-channels, each of which has equally spaced bandwidth. We set the number of iterations to 30 and consider 300 frames for each iteration. In addition, each CIoT sensor transmits 200 bits of data per frame when a certain sub-channel is allocated to the CIoT sensor. It is assumed that the channel follows an independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) Gaussian distribution and the average SNR is set to 3.5 dB. The relationship among the power values is such that

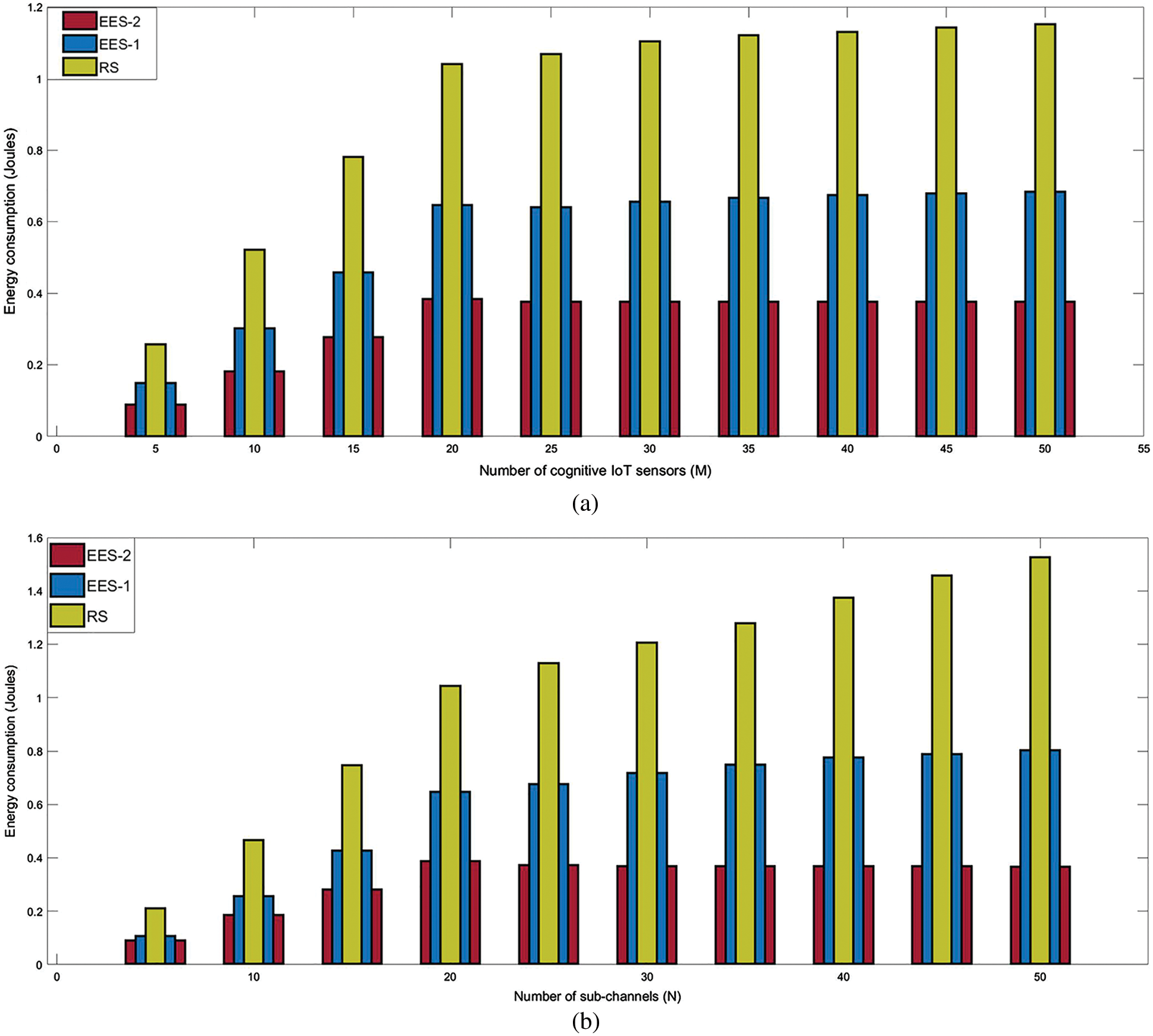

Fig. 6a shows the effect of the number of CIoT sensors on the energy consumption of the conventional and proposed scheduling schemes when the number of sub-channels is set to 20 (i.e.,

Figure 6: Energy consumption: (a) Effect of the number of CIoT sensors and (b) Effect of the number of sub-channels

Fig. 6b illustrates the effect of the number of sub-channels on the energy consumption when the number of CIoT sensors is set to (i.e., M = 20). In the figure, it is shown that the proposed EES-2 scheme achieves the lowest energy consumption. The proposed EES-2 scheme searches for the best assignment for all the CIoT sensors consuming less energy overall, while the proposed EES-1 scheme tries to allocate the best sub-channel to one of the CIoT sensors only satisfying the constraints, without considering the energy efficiency in the whole CIoT network. Since the RS scheme randomly chooses the CIoT sensors for the idle sub-channel without taking the energy efficiency into account, it consumes the most amount of energy, compared to the other proposed schemes.

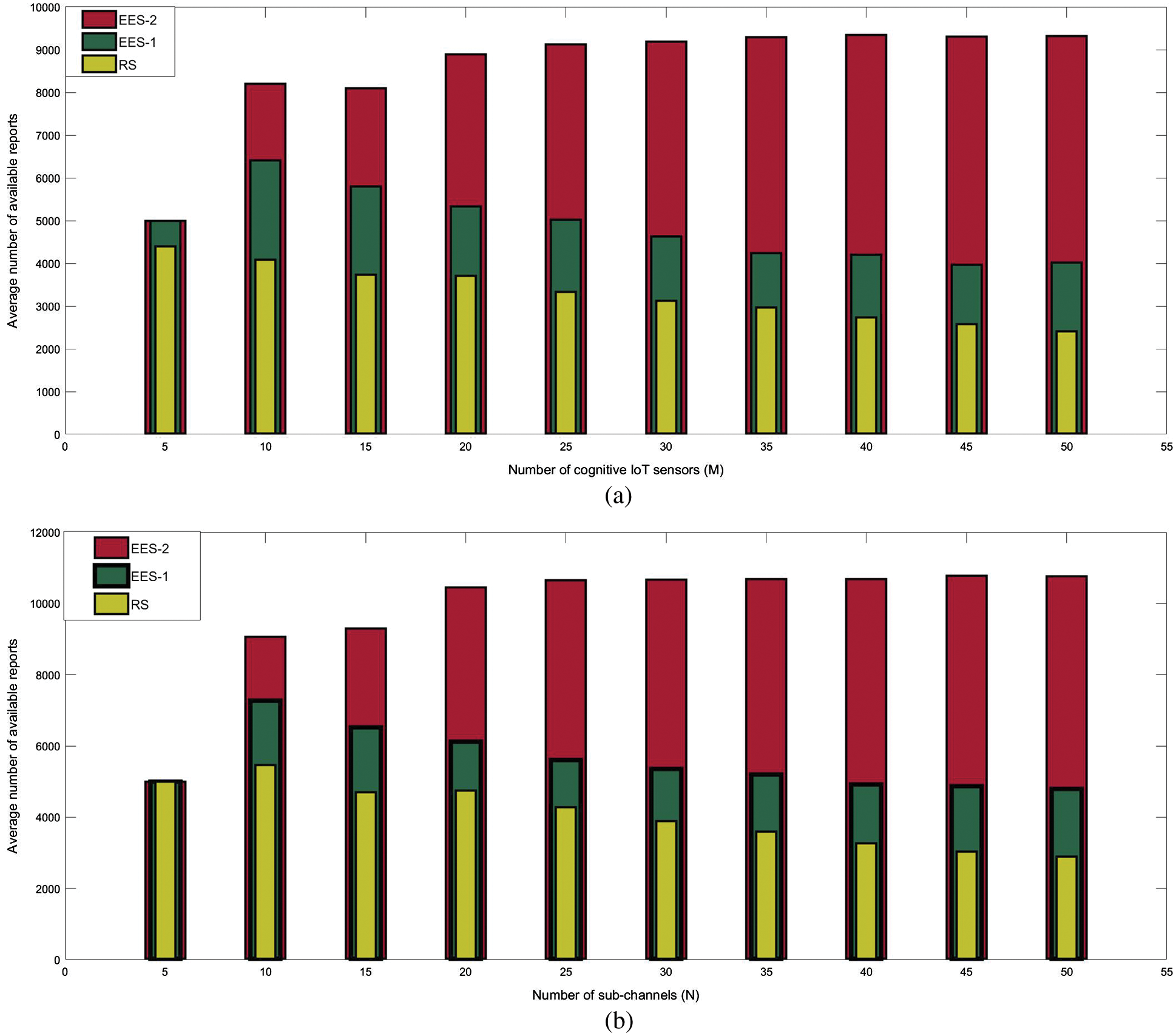

4.3 Average Number of Available Reports

The lifetime of a CIoT network can be defined as the average number of available reports in an assignment before the first depleted CIoT sensor in battery energy occurs in the network [40]. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed EES-1 and EES-2 schemes, we set the initial battery capacity of each CIoT sensor in the network to 15 mAh. The battery threshold level to decide the depletion of battery energy is set to 5 mAh and 10,000 consecutive frames are considered in the simulations.

Fig. 7 shows the average number of available reports for varying the number of CIoT sensors and the number of sub-channels. From Fig. 7a, it is clear that the proposed EES-2 scheme achieves a large average number of available reports before the first CIoT sensor reaches the battery threshold level. The average number of available increases with increasing the number of CIoT sensors. It is saturated to a certain level after a particular point since the fixed number of CIoT sensors only participate in data transmission effectively. On the other hand, the average number of available reports of the proposed EES-1 scheme rather decreases as the number of CIoT sensors increases. This is because in the proposed EES-1 scheme, due to being a greedy scheme, some of the CIoT sensors may transmit with higher energy on the assigned channel so that their batteries are more quickly depleted. Consequently, it consumes more energy in the assignments, resulting in a fast battery energy decay. Similarly, in Fig. 7b, it is shown that the proposed EES-2 scheme also outperforms the other schemes in terms of the average number of available reports. The average numbers of available reports of the conventional RS and proposed EES-1 schemes rather decrease as the number of sub-channels increases when it is larger than 10, while that of the proposed EES-2 scheme is increased and saturated to a certain level. Therefore, the proposed EES-2 scheme is the most efficient in the perspective of network lifetime.

Figure 7: Average number of available reports: (a) Effect of the number of CIoT sensors and (b) Effect of the number of sub-channels

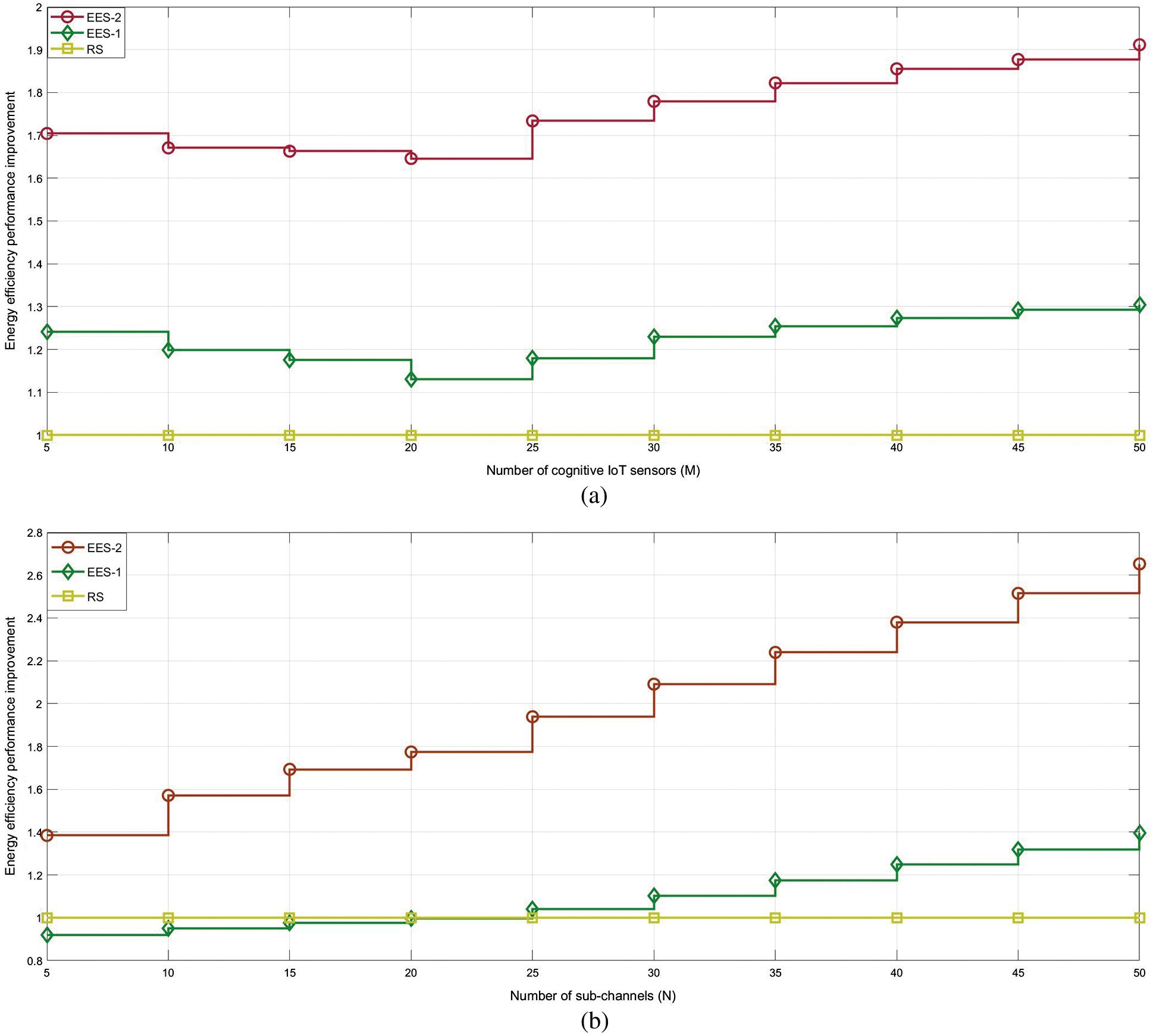

4.4 Normalised Energy Efficiency

In this subsection, we present the performance improvement in the normalized energy efficiency achieved by the proposed schemes over the conventional RS scheme. We consider the conventional RS scheme as a yardstick to show the relative effectiveness of the proposed schemes.

Fig. 8 shows the normalized energy efficiency for varying the number of CIoT sensors and the number of sub-channels. In Fig. 8a, when N = 20, as the number of CIoT sensors increases, the proposed EES-2 always outperforms the proposed EES-1 and the conventional RS schemes. Especially, it significantly improves the energy efficiency for a typical operation region, i.e.,

Figure 8: Normalized energy efficiency: (a) Effect of the number of CIoT sensors and (b) Effect of the number of sub-channels

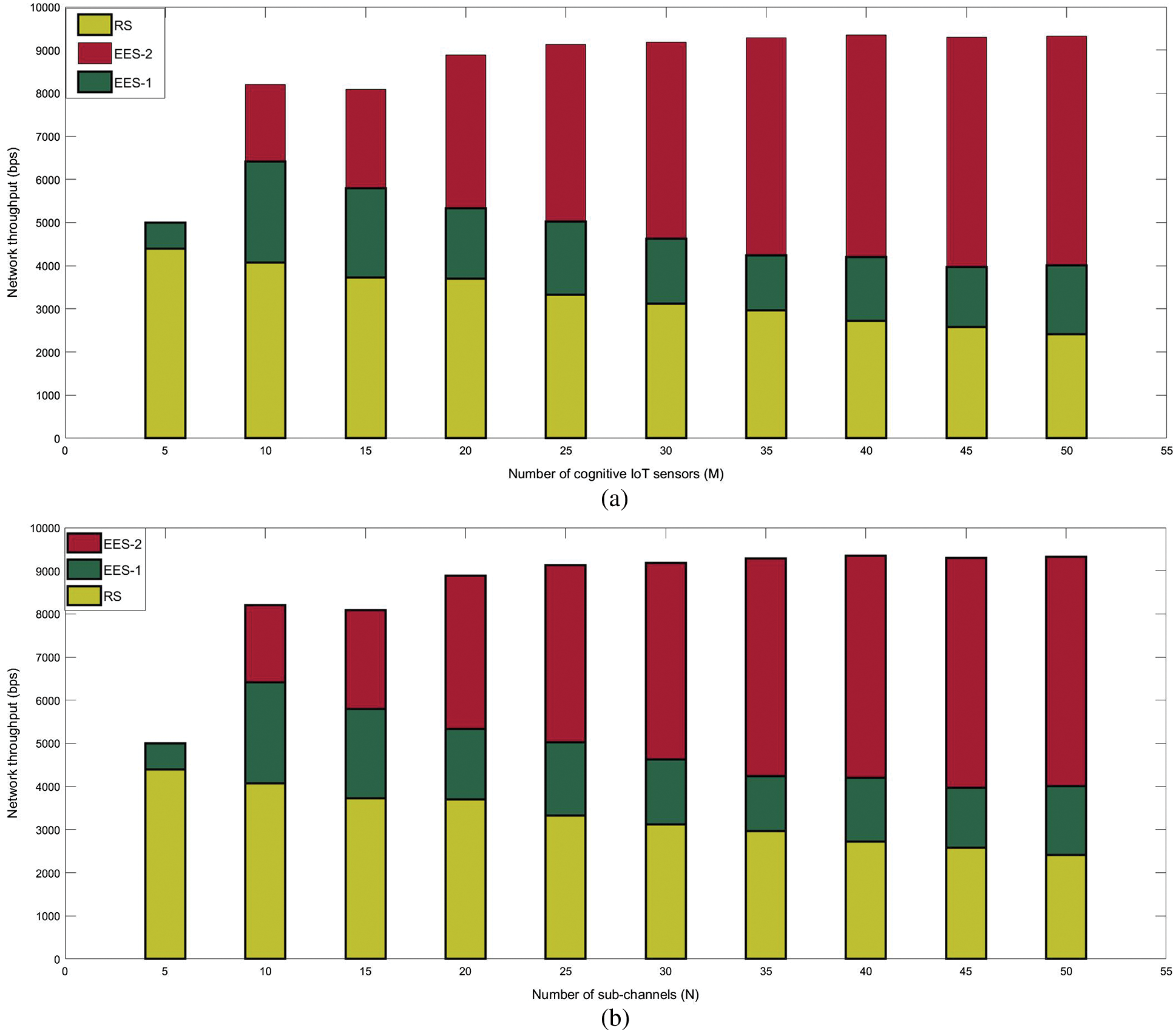

Fig. 9 shows the network throughput achieved by the proposed and conventional schemes for varying the number of CIoT sensors and the number of sub-channels. In Fig. 9a, the impact of the number of CIoT sensors on the network throughput in the network is illustrated when

Figure 9: Network throughput: (a) Effect of the number of CIoT sensors and (b) Effect of the number of sub-channels

In this work, we investigated a cognitive Internet of things (CIoT) network to develop a monitoring and early warning system (MEWS) to reduce the fatalities of flash floods. Considering the limited battery energy of CIoT sensors, we formulate an energy efficiency maximization problem. To solve the problem, we first propose a polynomial-time heuristic energy-efficient scheduler (EES-1) scheme. However, its performance can be unsatisfactory, since it provides local optimum values for some cases without considering the overall network energy efficiency. To enhance the energy efficiency of the proposed EES-1 scheme, we reformulate the optimization problem using a maximum weight matching bipartite graph. Additionally, we propose a Hungarian algorithm-based energy-efficient scheduler (EES-2) scheme. The proposed EES-2 scheme provides a significant performance improvement in terms of energy efficiency, compared to the proposed EES-1 and the conventional random scheduler (RS) scheme. As a result, the proposed EES-2 scheme, which achieves less energy consumption, can be applied for a MEWS system with battery-limited CIoT sensors under flash floods situations. More specifically, for a sufficiently large number of idle sub-channels, all CIoT sensors can acquire opportunities to transmit their collected sensing data, while a few CIoT sensors may not be able to transmit the data when the number of available idle sub-channels is less than the number of CIoT sensors. In the future, we plan to investigate a fairness issue in scheduling for more practical scenarios. Moreover, for an autonomous CIoT-based MEWS, we plan to integrate the reliability and a spectrum sensing capability in the objective function.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Korea, under the Information and Technology Research Center (ITRC) support program (IITP-2021–2018-0-01426) and in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2019R1F1A1059125).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. S. Doocy, A. Daniels, S. Murray and T. D. Kirsch, “The human impact of floods: A historical review of events 1980–2009 and systematic literature review,” PLoS Currents, vol. 5, pp. 1–15, 2013. [Google Scholar]

2. S. Seneviratne, N. Nicholls, D. Easterling, C. Goodess and S. Kanae, “Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment,” in Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation, 1st ed., pp. 109–230, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

3. A. Al-Fuqaha, M. Guizani, M. Mohammadi, M. Aledhari and M. Ayyash, “Internet of things: A survey on enabling technologies, protocols, and applications,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 17, pp. 2347–2376, 2015. [Google Scholar]

4. A. A. Khan, M. H. Rehmani and A. Rachedi, “When cognitive radio meets the internet of things,” 2016 in Int. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conf. (IWCMC), Paphos, Cyprus, IEEE, pp. 469–474, 2016. [Google Scholar]

5. T. Q. Duong and N. S. Vo, “Wireless communications and networks for 5G and beyond,” Mobile Networks and Applications-Springer, vol. 24, pp. 443–446, 2019. [Google Scholar]

6. S. Chatterjee, R. Mukherjee, S. Ghosh, D. Ghosh and A. Mukherjee, “Internet of things and cognitive radio—Issues and challenges,” in 2017 4th Int. Conf. on Opto-Electronics and Applied Optics (Optronix), Kolkata, India, IEEE, pp. 1–4, 2017. [Google Scholar]

7. T. L., Doumi, “Spectrum considerations for public safety in the United States,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 44, pp. 30–37, 2006. [Google Scholar]

8. G. Himayat, Y. Li and A. Swami, “Cross-layer optimization for energy-efficient wireless communications: A survey,” Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, vol. 9, pp. 529–542, 2009. [Google Scholar]

9. L. Atzori, A. Iera and G. Morabito, “The internet of things: A survey,” Computer Networks, vol. 15, no. 14, pp. 2787–2805, 2010. [Google Scholar]

10. R. K. Mehta, J. Nuamah, S. C. Peres and R. R. Murphy, “Field methods to quantify emergency responder fatigue: Lessons learned from UAS deployment at the 2018 kilauea volcano eruption,” IISE Transactions on Occupational Ergonomics and Human Factors, vol. 8, pp. 166–174, 2020. [Google Scholar]

11. T. Einfalt, F. Hatzfeld, A. Wagner, J. Seltmann and D. Castro, “URBAS: Forecasting and management of flash floods in urban areas,” Urban Water Journal, vol. 6, pp. 369–374, 2009. [Google Scholar]

12. R. P. K. Lam, L. P. Leung, S. Balsari, K. H. Hsiao and E. Newnham, “Urban disaster preparedness of Hong Kong residents: A territory-wide survey,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, vol. 23, pp. 62–69, 2021. [Google Scholar]

13. D. Chen, Z. Liu, L. Wang, M. Dou and J. Chen, “Natural disaster monitoring with wireless sensor networks: A case study of data-intensive applications upon low-cost scalable systems,” Mobile Networks and Applications, vol. 18, pp. 651–663, 2013. [Google Scholar]

14. J. Sunkpho and C. Ootamakorn, “Real-time flood monitoring and warning system,” Songklanakarin Journal of Science & Technology, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 227–235, 2011. [Google Scholar]

15. S. I. A. Shah, M. Fayed, M. Dhodhi and H. T. Mouftah, “Aqua-net: A flexible architectural framework for water management based on wireless sensor networks,” 2011 24th Canadian Conf. on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, IEEE, pp. 000481–000484, 2011. [Google Scholar]

16. T. Kim, D. Qiao and W. Choi, “Energy-efficient scheduling of internet of things devices for environmental monitoring applications,” in 2018 IEEE Int. Conf. on Communications (ICC), Kansas City, MO, USA, IEEE, pp. 1–7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

17. M. Thomas, S. Ummer, T. S. Vijayan, T. Vivek and A. S. Kumar, “Flood prediction and warning system using dam data monitoring,” International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1–5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

18. A. R. Asnaning and S. D. Putra, “Flood early warning system using cognitive artificial intelligence: The design of AWLR sensor,” in 2018 Int. Conf. on Information Technology Systems and Innovation (ICITSI), Bandung, Indonesia, IEEE, pp. 165–170, 2018. [Google Scholar]

19. A. Sinha, P. Kumar, N. P. Rana, R. Islam and Y. K. Dwivedi, “Impact of internet of things (IoT) in disaster management: A task-technology fit perspective,” Annals of Operations Research, vol. 283, pp. 759–794, 2019. [Google Scholar]

20. A. Arooj, M. S. Farooq, T. Umer and R. U. Shan, “Cognitive internet of vehicles and disaster management: A proposed architecture and future direction,” Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies, pp. e3625, 2019. [Google Scholar]

21. S. M. George, W. Zhou, H. Chenji, M. Won, Y. O. Lee et al., “Distressnet: A wireless ad hoc and sensor network architecture for situation management in disaster response,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 48, pp. 128–136, 2010. [Google Scholar]

22. A. Ahmadalipour and H. A. Moradkhani, “A data-driven analysis of flash flood hazard, fatalities, and damages, over the CONUS during,” Journal of Hydrology, vol. 578, pp. 1996–2017, 2019. [Google Scholar]

23. K. H. Chan, C. S. Cheang and W. W. Choi, “Zigbee wireless sensor network for surface drainage monitoring and flood prediction,” in Int. Symp. on Antennas and Propagation Conf. Proc., Kaohsiung, Taiwan, IEEE, pp. 391–392, 2014. [Google Scholar]

24. D. F. Larios, J. Barbancho, G. Rodríguez, J. L. Sevillano, F. J. Molina et al., “Energy efficient wireless sensor network communications based on computational intelligent data fusion for environmental monitoring,” IET Communications, vol. 6, pp. 2189–2197, 2012. [Google Scholar]

25. M. Acosta-Coll, F. Ballester-Merelo, M. Martinez-Peiró and D. la Hoz-Franco, “Real-time early warning system design for pluvial flash floods—A review,” Sensors, vol. 18, no. 7, pp. 2255–2281, 2018. [Google Scholar]

26. K. Sharma, D. Anand, M. Sabharwal, P. K. Tiwari, O. Cheikhrouhou et al.,, “A disaster management framework using internet of things-based interconnected devices,” Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2021, pp. 1–21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

27. S. R. Sarangi, S. Goel and B. Singh, “Energy-efficient scheduling in IoT networks,” in Proc. of the 33rd Annual ACM Symp. on Applied Computing, New York, NY, United States, pp. 733–740, 2018. [Google Scholar]

28. N. H. Bui, C. Pham, K. K. Nguyen and M. Cheriet, “Energy-efficient scheduling for networked IoT device software update,” in 15th Int. Conf. on Network and Service Management (CNSM), Halifax, NS, Canada, IEEE, pp. 1–5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

29. B. Afzal, S. A. Alvi, G. A. Shah and W. Mahmood, “Energy efficient context aware traffic scheduling for IoT applications,” Ad Hoc Networks, vol. 62, pp. 101–115, 2017. [Google Scholar]

30. B. Yu, L. Pu, Q. Xie and J. Xu, “Energy efficient scheduling for IoT applications with offloading, user association and BS sleeping in ultra dense networks,” in 16th Int. Symp. on Modeling and Optimization in Mobile, Ad Hoc, and Wireless Networks (WiOpt), Shanghai, China, IEEE, pp. 1–6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

31. G. Kaur, P. Chanak and M. Bhattacharya, “Energy efficient intelligent routing scheme for IoT-enabled WSNs,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 8, no. 14, pp. 11440–11449, 2021. [Google Scholar]

32. S. Verma, S. Kaur, D. B. Rawat, C. Xi, L. T. Alex et al., “Intelligent framework using iot-based wsns for wildfire detection,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 48185–48196, 2021. [Google Scholar]

33. R. Murty, R. Chandra, T. Moscibroda and P. Bahl, “Senseless: A database-driven white spaces network,” IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, vol. 11, pp. 189–203, 2011. [Google Scholar]

34. M. Caleffi and A. S. Cacciapuoti, “Database access strategy for TV white space cognitive radio networks,” in 2014 Eleventh Annual IEEE Int. Conf. on Sensing, Communication, and Networking Workshops (SECON Workshops), Singapore, pp. 34–38, 2014. [Google Scholar]

35. D. Gözüpek, S. Buhari and F. Alagöz, “A spectrum switching delay-aware scheduling algorithm for centralized cognitive radio networks,” IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, vol. 12, pp. 1270–1280, 2012. [Google Scholar]

36. S. Krishnamurthy, M. Thoppian, S. Venkatesan and R. Prakash, “Control channel based MAC-layer configuration, routing and situation awareness for cognitive radio networks,” in MILCOM 2005–2005 IEEE Military Communications Conference, Atlantic City, NJ, IEEE, pp. 455–460, 2005. [Google Scholar]

37. H. Ma, L. Zheng and X. Ma, “Spectrum aware routing for multi-hop cognitive radio networks with a single transceiver,” in 3rd Int. Conf. on Cognitive Radio Oriented Wireless Networks and Communications (CrownCom 2008), Singapore, IEEE, pp. 1–6, 2008. [Google Scholar]

38. V. Rodoplu and T. H. Meng, “Bits-per-joule capacity of energy-limited wireless networks,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 6, pp. 857–865, 2007. [Google Scholar]

39. C. H. Papadimitriou and K. Steiglitz, “Weighted matching,” in Combinatorial Optimization: Algorithms and Complexity,” 1st ed., Mineola, New York, USA: Dover Publications, pp. 247–269, 1998. [Google Scholar]

40. K. Hung, W. Lee, V. Li, K. Lui, P. Pong et al., “On wireless sensors communication for overhead transmission line monitoring in power delivery systems,” in First IEEE Int. Conf. on Smart Grid Communications, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, IEEE, pp. 309–314, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |