DOI:10.32604/cmc.2022.022444

| Computers, Materials & Continua DOI:10.32604/cmc.2022.022444 |  |

| Article |

Fleet Optimization of Smart Electric Motorcycle System Using Deep Reinforcement Learning

School of Telecommunication Engineering, Suranaree University of Technology, Nakhon Ratchasima, 30000, Thailand

*Corresponding Author: Peerapong Uthansakul. Email: uthansakul@sut.ac.th

Received: 06 August 2021; Accepted: 07 September 2021

Abstract: Smart electric motorcycle-sharing systems based on the digital platform are one of the public transportations that we use in daily lives when the sharing economy is considered. This transportation provides convenience for users with low-cost systems while it also promotes an environmental conservation. Normally, users rent the vehicle to travel from the origin station to another station near their destination with a one-way trip in which the demand of renting and returning at each station is different. This leads to unbalanced vehicle rental systems. To avoid the full or empty inventory, the electric motorcycle-sharing rebalancing with the fleet optimization is employed to deliver the user experience and increase rental opportunities. In this paper, the authors propose a fleet optimization to manage the appropriate number of vehicles in each station by considering the cost of moving tasks and the rental opportunity to increase business return. Although the increasing number of service stations results in a large action space, the proposed routing algorithm is able filter the size of the action space to enable computing tasks. In this paper, a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) creates the decision-making function to decide the appropriate action for fleet allocation from the last state of the number of vehicles at each station in the real environment at Suranaree University of Technology (SUT), Thailand. The obtained results indicate that the proposed concept can reduce the Operating Expenditure (OPEX).

Keywords: Electric motorcycle-sharing; sharing economy; reinforcement learning; OPEX

Public transportation systems provide various options such as trains, planes, buses, subways and so on, which are intended for the general public communications. The purposes of these public transports are to reduce traffic congestion and make it more comfortable for users [1]. The public transportations have fixed routes running at scheduled times. However, the transport systems are also limited in terms of time and inflexible route [2]. Thus, one of the best solutions to solve the problem of this public transport is the economic sharing model [3]. A vehicle-sharing system aims to provide a missing link in public transportation for short trips in an urban environment. Previously, a bike-sharing system was used to connect the long-haul transport systems to provide information to the passengers and tourists from the origin to another station near their destination [4]. Nevertheless, the rapid growth of the world's population has led to a sharp increase in the use of vehicles, causing air pollution and greenhouse gases, in which the transportation sector has become a big supporter [5]. Therefore, the vehicle sharing business in the future should consider the service based on eco-friendly egress. This type of business is beneficial not only for the environment but also for the economy [6].

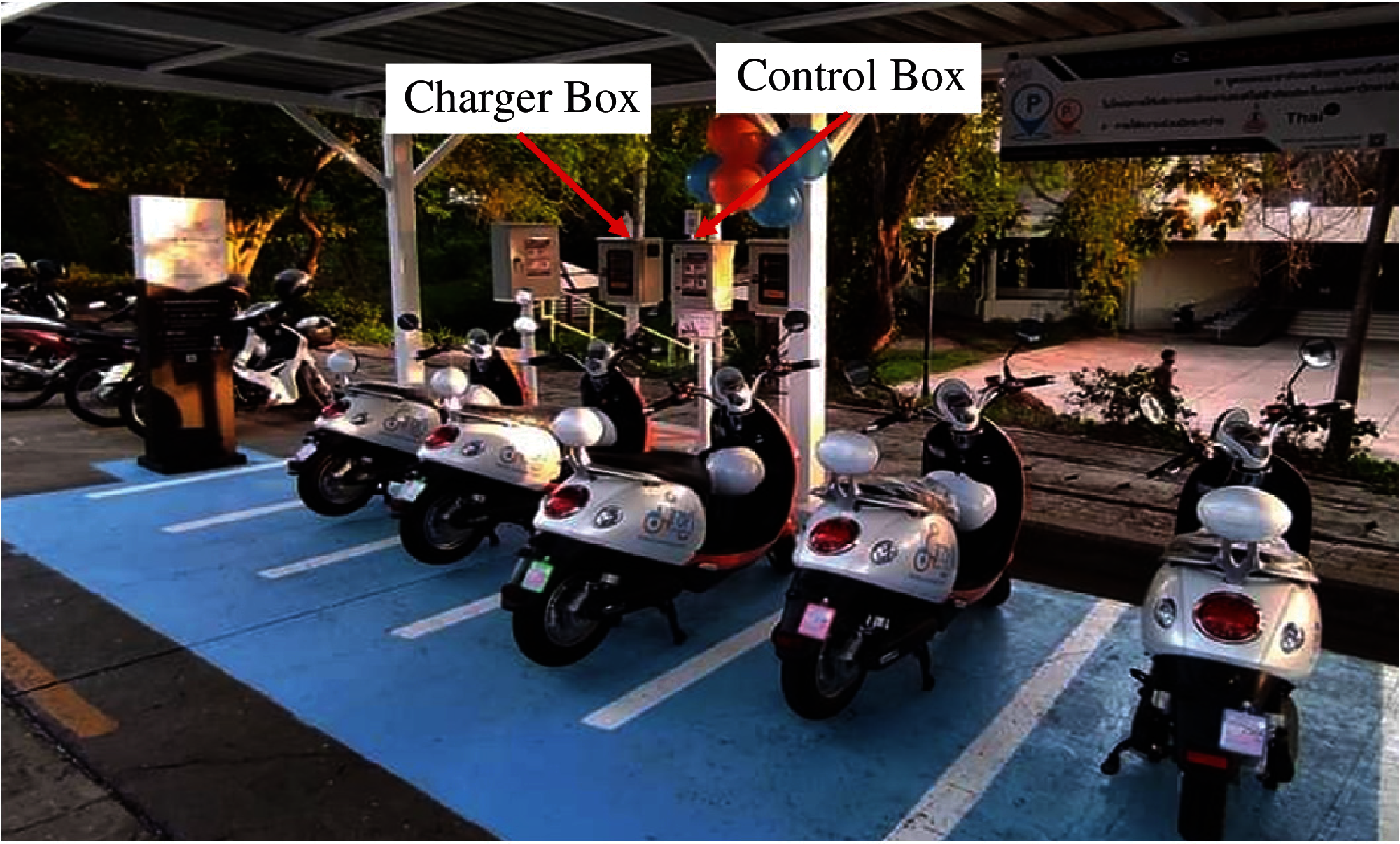

The smart electric motorcycle-sharing system is a short-haul transport system with electrical motorcycle stations located throughout various service areas. In this paper, the service area of interest is located at Suranaree University of Technology (SUT), Thailand. Each station includes electric motorcycles and docks to serve the users for rental and return, as shown in Fig. 1. Each dock has a charger to recharge the battery of an electric motorcycle while the vehicle is equipped with a digital platform to identify geographic coordinates and measure parameters. This public transportation system can access MoreSai (), which downloads online applications from iOS and Android platforms, as shown in Fig. 2. An electrical motorcycle station near the user's current location can be located from this mobile application. Users must have a driving license and make an online top-up to the system. The service charge computes from the earned credit by a rental vehicle and trip distance, which is affordable. Rentals take place at the origin station, and the return occurs at the station near the destination. This digital platform offers convenience, transport flexibility, cost savings for individuals and environmental conservation.

Figure 1: Smart electric motorcycle-sharing system at Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

Figure 2: Application for smart electric motorcycle-sharing system

The usage characteristic of an electric motorcycle is a one-way trip to travel from the origin station to another station near the destination with a short trip. One drawback of these systems is the unbalanced distribution of vehicles between rental and return demands of each station. This may lead to a high probability that there are no vehicles in the docks during rush hour. At the same time, the overall vehicle number of some stations may exceed the supported docks. Hence, the electric motorcycle sharing system must balance the vehicles to avoid the full or empty inventory using a fleet truck to allocate the vehicles in the service areas. The fleet allocation takes place when a need is required or at the end of the day. The volume of vehicle rentals affects business income, while the moving tasks for rebalancing electric motorcycles incur the Operating Expenditure (OPEX). A fleet management is an important issue to profit the business return. Hence, the fleet optimization can increase the probability of vehicle rentals and reduce the cost of vehicle allocation.

In this paper, the authors propose a fleet optimization to rebalance the appropriate number of electric motorcycles in each station by considering the cost of vehicle allocation and the rental opportunity to increase business returns. Moreover, Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) is applied to build the decision-making function to decide the action from the last system state. Besides, the proposed routing algorithm filters the size of action space to enable computing tasks and reduce computational complexity. In this case, the smart electric motorcycle-sharing system is executed as a service at SUT, Thailand. The contributions and novelties in this paper are summarized as follows:

1)The authors apply the DRL to build the decision-making function based on the state of the available vehicles in each station to decide the appropriate action for moving the tasks.

2)Fleet management is determined by rental opportunities in the next state and vehicle relocation costs to decide the action that delivers the highest business return.

3)The authors use the proposed routing algorithm to filter the size of the action space based on the datasets collected by the personnel team of the moving task to simplify the process.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The related work in fleet management is discussed in Section 2. The problem formulation is introduced in Section 3. The proposed algorithm and the DRL are described in Section 4. The simulation results and discussion are described in Section 5, and the conclusions are summarized in Section 6.

Fleet allocation is a classic problem as a Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) that combines the vehicles to the center and then delivers them to each station [7]. Currently, the sharing economy can operate in several regions in which each area consists of a group of service stations and vehicles. When the rental and return demands of each station is different, a vehicle unbalancing occurs. Therefore, this problem was usually carried out by hiring a fleet truck to rebalance the vehicles. Fleet allocation is separated into two topics: vehicle transport routing and pickup/delivery [8]. These issues are solved by a branch-and-cut algorithm [9]. This algorithm finds the most suitable method with the One-commodity Pickup-and-Delivery TSP (1-PDTSP) to allocate the vehicles. Besides, a fleet allocation for the bike-sharing system was developed to build the model for allocating bicycles [10]. In recent years, vehicle sharing systems have gained significant attention from researchers focusing on the benefits of bicycle sharing [11], safety issues [12], and the suitable environment for bicycle activities [13]. Moreover, the Geographic Information System (GIS) method was applied to analyze the travel requirements from spatial distribution to determine the location of the service station for vehicle sharing [14]. The Static Bike Rebalancing Problem (SBRP) was proposed to prioritize the minimum cost of moving tasks using a compact pickup truck [15]. However, the sharing economy still places a great emphasis on user experience. The static repositioning was presented to reduce the dissatisfaction of the general users in the specified period [16]. In the vehicle rebalancing with the heuristic method, a genetic algorithm is studied to find the optimal initial state of the optimal bicycle number in each station to meet the user needs [17]. The greedy approach was applied to find the shortest vehicle-moving distance to reduce operating costs [18].

However, these existing works achieved the purpose of shortest routing, initial state and the optimal number for pickup and delivery in each station. However, a few studies have looked at the optimal routing and the correct number in each station, considering the reduction of moving costs in order to increase rental opportunities. Therefore, the work direction should be focused on the optimal routing of moving tasks with pickup and delivery by increasing rental opportunities. Also, the Reinforcement Learning (RL) is used to build a decision-making function for the highest return in the business.

This paper proposes an initial concept for fleet optimization in different areas to solve the fleet problem. The areas with many service stations greatly affect the computational complexity for calculating the fleet truck routing. However, the proposed algorithm in this paper is used to consider the possible routes which is the action space for a fleet routing using the collected datasets from the personnel team of moving tasks. The filtered action space and the state of vehicle number in each station create the decision-making function using the DRL algorithm. The action space is a feasible route to transport vehicles for the fleet of electric motorcycles. The selection of actions is determined by the state of vehicle number in each station to calculate the most rental opportunities and the least cost of vehicle allocation.

From the existing works, the fleet management has not considered the rental opportunities and the cost of moving vehicles in complex situations. Most research focused on transport routing, pickup and delivery and balancing vehicles. Nevertheless, Jack's car rental managed two stations with the policy iteration algorithm for a car rental company in a simple situation [19]. The created policy function with RL considers the rental and return opportunities and the cost of moving tasks, which is a need concept for entrepreneurs. Meanwhile, this method is applied to build the policy function in scope with 4 stations, as shown in Fig. 3. The number of links is computed according to the number of stations divided by two and multiplied by the number of stations minus one. There are 6 links for delivery among stations. A fleet truck can contain 3 vehicles to pick up and deliver between the origin station and destination station. Each link is possible for pickup as 7 cases (L ∈ { −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3}). The possible action can be calculated by the number of pickup cases raised to the power of the number of links, which is equal to 117,648 members in this situation. However, the number of stations and pickup cases enormously affects the complexity of an algorithm. In the current situation, the sharing systems are not only built to serve 2 stations or 4 stations, as mentioned in previous works, but it also considers the user needs in a broader area. Thus, this method may not be the appropriate solution for complex situations with more than four stations.

Figure 3: Possible action for pickup and delivery with four stations

In this paper, the smart electric motorcycle-sharing system is executed as a service at SUT, Thailand, as shown in Fig. 4. These systems consist of 10 stations (S1 to S10 has 4, 4, 3, 4, 0, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3 vehicles, respectively.), 30 electric motorcycles and 1 fleet truck. These stations are built near essential areas such as education buildings, dormitories, parks, hospitals, bus terminals and service buildings. The electric motorcycles serve the users with driving licenses consisting of personnel, students, and individuals. Besides, the personnel team of moving tasks supports to rebalance the electric motorcycle with the fleet truck, containing 3 vehicles to pick up and deliver between the origin station and destination station in each link. In this situation, there are 45 links for delivery between both stations. Each link is possible for pickup as 7 cases, while the possible action is equal to 1.07E + 38 members, as shown in Fig. 5. With many stations, the decision-making function with the existing concept is challenging because computing task is complex and requires a high-performance machine to create the policy function.

Figure 4: Smart electric motorcycle-sharing system with ten stations at Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

Figure 5: Possible action for pickup and delivery based on smart electric motorcycle-sharing system at Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

Therefore, the authors improve the problem with two issues to optimize the fleet management with the concept of increasing rental opportunities and reducing the cost of moving tasks similar to Jack's car rental. Firstly, the number of possible actions is enormous, resulting in improbable computing tasks. Thus, the number of all actions must be decreased to be suitable for computing tasks. The dataset collected from the personnel team of moving tasks is used to filter the appropriate answer into the action space in each system state. Secondly, the DRL is used to build the decision-making function instead of the policy iteration algorithm. This method can support more complex stations. Thus, both issues can achieve the purpose to implement in the real environment of case study at SUT, Thailand.

4 Routing Algorithm and DRL Scheme

The routing algorithm and the DRL scheme filter the appropriate action and create the decision-making function to allocate the vehicles in the motorcycle-sharing system. To achieve the most rental opportunities and the least cost of moving tasks, the authors consider the decision-making function created by different sizes of action space. These processes are discussed as follows:

The number of rental vehicles is seen as the business income, and the cost of moving tasks is the Operating Expenditure (OPEX). The rental opportunities can be analyzed by the statistical data collected by the personnel team of the moving task. A station with high user demand is always allocated more vehicles. However, the one-way trip results in the vehicles being unbalanced by the rental and return demands of each station. To avoid the full or empty vehicles in each station, the fleet truck is appropriately used to allocate the vehicles in the service area. Thus, the moving tasks are important in these systems.

In the moving tasks, the fleet truck always starts departing from the central station to travel to other stations to move vehicles according to the command assessed by the personnel team. After completing the mission, it comes back to the central station. In the case study in this paper, as shown in Fig. 4, there are 10 stations consisting of central station (S1), and other stations (S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10) to provide the electric motorcycle services. At the same time, the fleet truck is at the central station to rebalance the vehicles at the end of the day or when the allocation is required. The fleet truck routing is defined as the round-trip route to operate the pickup and delivery of each station. The possible number of round-trip routes can be computed using (1), when N is the number of stations in the service area.

In this case, the number of stations is equal to 10, so the round-trip routes are equal to 986,409. When all actions are equal to 1.07E + 38 members, as shown in Fig. 5, it is the Universal set of action (U). All action spaces are impossible to take the action space into account due to the enormous amount. Therefore, the member of all actions is decreased to be suitable for computing tasks. The routing algorithm is created to filter the actions which are consistent for round-trip routes. In the moving tasks, the number of stations where the fleet truck stops for pickup and delivery is possible from 1 to 9. Afterwards, it returns to the central station. In this case, the number of overall stations, the number of stations where the truck stops and the number of pickup cases are equal to 10, 9 and 7, respectively. The actions corresponding to the round-trip route are equal to 3.9E + 10 members, as shown in Fig. 6. This operation is explained in Algorithm 1.

The personnel team of moving tasks makes a decision based on work experience, they have decided on the pickup and delivery of vehicles for each station at the end of the day. The datasets consist of the state information in which the action and the new state are collected into the database for analyzing the user demand, as shown in Fig. 7. Besides, the systems collect data on the number of rental and return vehicles of each station every day. Although the selected actions are significantly reduced, there are still many appropriate actions for computing tasks. In real environment, it is not possible for action space of 3.9E + 10. Thus, the authors consider the popular route from the datasets to filter the actions for creating the decision-making function. Fig. 8 shows the process of action selection with the collected datasets and the actions corresponding to the round-trip route. The collected datasets consist of system state, action and new state. The actions of datasets are analyzed to interpret as round-trip routes. Each route is prioritized based on the popularity of action decided by the personal team of moving tasks. These popular routes filter the actions sorted by popularity. In this paper, the scope of action is fixed as three cases consisting of Cases I, II and III, as shown in Fig. 8, for finding the appropriate answer using DRL algorithm. These cases are defined to compare the results from the different members of each action space appropriately. This scheme is discussed in the following subsection.

Figure 6: Selection of appropriate actions with the routing algorithm

4.2 Deep Reinforcement Leaning

Deep Q-Learning (DQN) is evolved by applying Artificial Neurol Network (ANN) for the large state and action spaces [20]. The ANN parameters are trained by gradient descent to minimize loss function. This algorithm focuses on interacting with the environment to obtain the maximum Q value for each state and action from moving the vehicles in this paper. The interaction between agent and environment are learned by system state, action and new state. Fig. 9 shows the DQN structure consisting of agent and environment. The environment is the electric motorcycle-sharing system. When the personnel team or agent chooses the action, the system state changes to the new state. After that, the reward is computed from the function between the income and cost of moving tasks. The working of DQN algorithm iteratively learn until the appropriate Q value to be a decision-making function for implementation is obtained. In the DQN algorithm, the number of input node and output node are equal to the number of stations and action members. In this paper, the state, action and reward function in the DRL process are discussed as follows:

The systems have 10 stations to serve the electric motorcycles at SUT area, Thailand. The numbers of the available vehicles in each station are defined as the system states (s) as shown in (2). These states are used to decide the action for moving vehicles. As a result, the systems become the new state (s′).

Figure 7: Dataset collection from moving tasks by fleet truck

In this case, this motorcycle-sharing system has one fleet truck for the moving tasks. It can carry 3 electric motorcycles to pick up and deliver between the origin station and destination station. The possibility for delivering each link, as shown in Fig. 5, is equal to 7 pickup cases (L ∈ {−3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3}), and there are 45 links connected between origin station and destination station. Thus, the decided action can define as per (3).

Figure 8: Action space filtered by the dataset collection

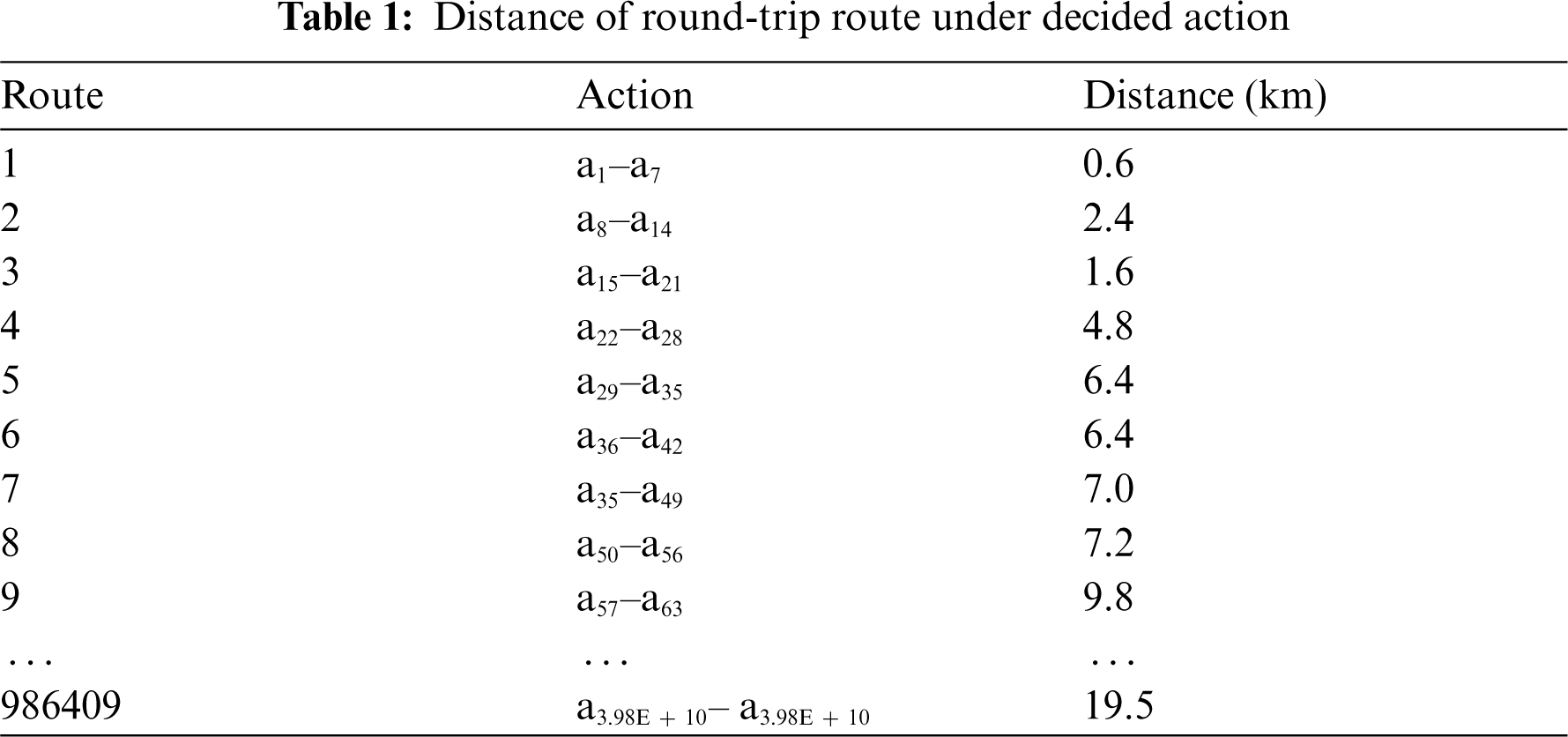

When the agent decides the action, this command will be sent to the personnel team to move the vehicles. The decided action (a) is considered to compute the cost of moving tasks (M), which depends on the distance of fleet truck. For example, the decided action is a63. In Fig. 6, the number of stations where the truck stops is 1 (S1> S10> S1). The fleet truck starts from the central station to pick up 1 motorcycle at S10, and then travels back to S1 to deliver. This route has a round trip distance of 9.8 kilometers, as shown in Fig. 10. Additionally, another action is compared with the round-trip route of fleet truck, as shown in Tab. 1. After that, the distance is multiplied by the coefficient of moving task (m). This cost is computed using (4).

In the result of reward (r) after fleet management, the income from rental vehicle minus the cost of moving tasks, as shown in (5). When

The Q-learning is the early progression of reinforcement learning with an off-policy Temporal-Difference (TD) control algorithm. It creates the action-value function from the experience with the exploration of the environment. The Q-learning function is defined as shown in (6), in which α is the learning rate and γ is the discount factor.

Figure 9: Deep Q-learning structure

However, the size of the Q-value table exponentially increases when the state space and action space are expanded. This results in large storage and high computation to converge the optimal policy. Thus, the application of Q-learning techniques in the ANN training process is a successful combination of deep learning in the DQN framework. This technique can indefinitely expand the states and the actions. The memory replay is applied by collecting the information from the experience, in which the information contains the datasets of state, action, reward and next state. Then, the mini-batch size chooses these datasets to train the ANN by considering new loss function for the DQN algorithm. The DRL operation is described in Algorithm 2. The loss function is written in (7), where θ is the weight.

Figure 10: Distance of fleet truck routing among smart electric stations at Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

In this section, the authors discuss the policy creation and the implementation. The DQN algorithm is used to create the decision-making function to decide the action from the system state. The proposed routing algorithm is used to filter the action space with suitable size. The created decision-making function is implemented in the real environment.

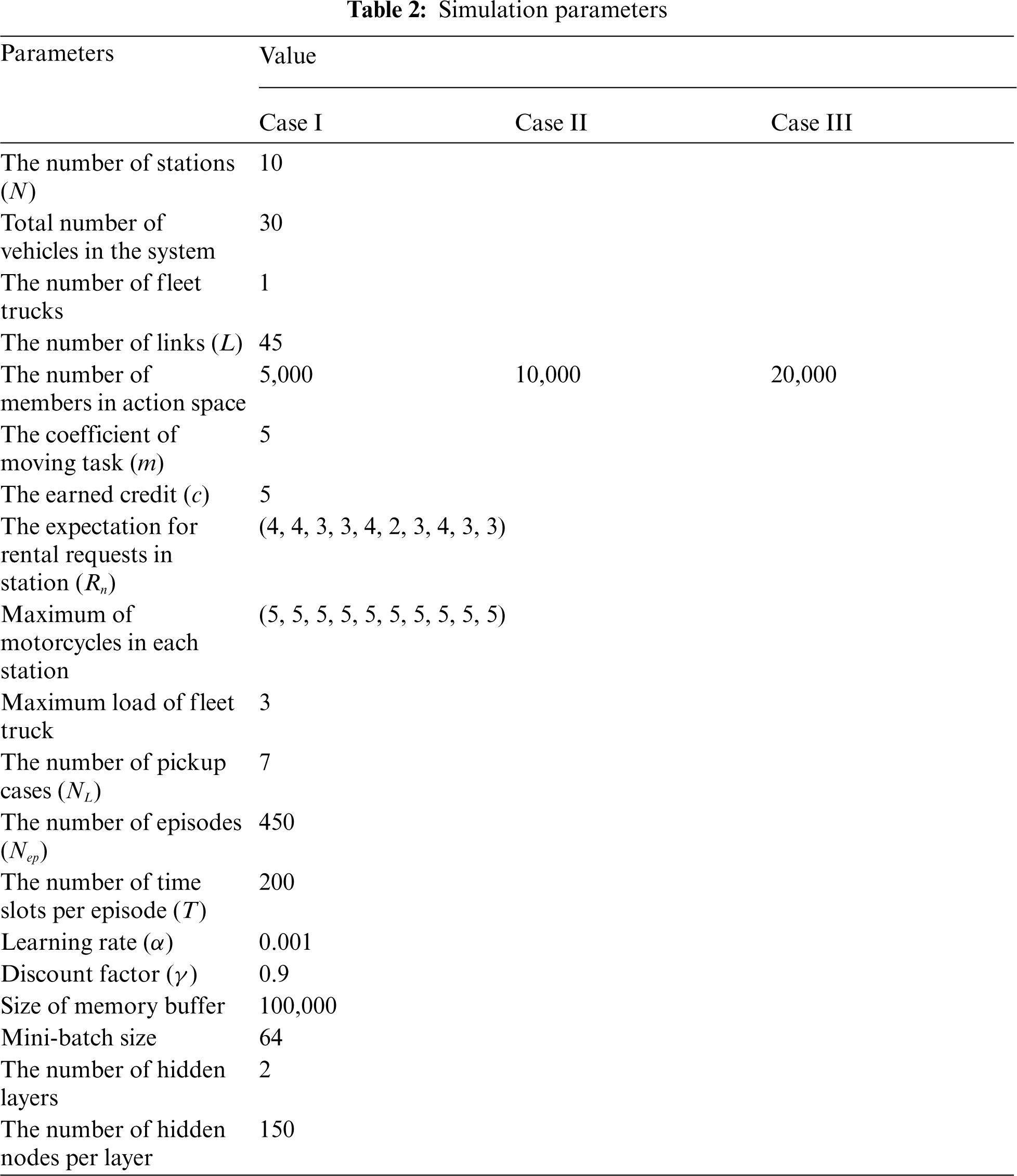

The authors create the decision-making function using the DRL algorithm for optimizing the fleet management. This algorithm learns the interaction between agent and environment to obtain the maximum Q value. The action space and the state space are set on interacting with the environment for considering the decision-making function. In this paper, the simulation parameters are defined, as shown Tab. 2. The case study at SUT, Thailand, consists of 10 stations, 30 electric motorcycles, which are located near essential areas. There are 45 links connected between origin and destination stations. The different number of vehicles depending on the user needs are allocated to each station. The maximum number of vehicles supported at each station is 5. The vehicle movement in each link can support up to 3 vehicles at a time with fleet trucks. The appropriate number of hidden layers is defined by the Trial-and-Error method, which is equal to 2 layers. However, the size of action space is considered with the different space consisting of 3 situations (Case I = 5,000 members, Case II = 10,000 members and Case III = 20,000 members). Besides, other parameters are configured to perform the DQN learning, as shown in Tab. 2.

Fig. 11 shows the loss of TD Error between target ANN and Q value. These graphs compare the error of the learning step in each case consisting of Cases I, II, III and Random, while Random is the traditional method of randomly selecting actions to create the action space without a routing algorithm with 20,000 members. The graph of Case I has the lowest TD error, while Case III has the highest TD error during the initial stage of the learning step. As the learning step increases, each case's TD error value volatilely decreases until the final stage. The creation of the decision-making function relies on parameter tuning within the DQN Algorithm using gradient descent to reduce the TD error as the learning step increases. The performance of the decision-making function depends on the reward of Q value, as shown in Fig. 12. The Q value of each case volatilely increases according to the episodes. The authors have found that Case II has the highest average reward at the end of the learning process, while Cases I and III have the most negligible Q value. However, the random case has the lowest value. This is because the action space is not considered with the proposed routing algorithm.

The created decision-making function decides the action from the system state to rebalance the vehicles in the systems. In the case study at the SUT area, the fleet allocation may occur at the end of the day. As seen in Fig. 13, the number of vehicles in each station is sent to the electric motorcycle-sharing system. This system state is entered into the decision-making function. In this decision, the algorithm considers the action with the maximum Q value. The personnel team of moving tasks allocates the vehicles according to the command of action. For example, L14 = −1 and L15 = −1 are interpreted as moving one motorcycle from S4 to S6 and moving one motorcycle from S5 to S6. The fleet truck starts from the central station to pick up 2 motorcycles at S4 and S5. Both motorcycles are delivered to S6. After completing the mission, the fleet truck returns to the central station. In this route, the number of stations where the truck stops are equal to 3 stations and the round-trip route is equal to 7.5 kilometers. Therefore, the new state can increase the rental opportunities. Also, the action is considered from the least cost of moving task to profit the economy sharing business. When focusing on the moving task of fleet truck, the proposed method provides less distance comparing to the conventional method, as shown in Fig. 14. Moreover, the decided action from the proposed method provides higher reward.

Figure 11: TD error between target value and Q-values

Figure 12: Average reward for varying episodes

Figure 13: Implementation of decision-making function to decide the moving tasks on smart electric motorcycle-sharing system at Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

In this paper, the authors create a concept to optimize fleet management based on the DRL. This concept aims to profit the economy sharing business. Although the DQN algorithm is created using the large state and action spaces, there is also a limitation to be used with enormous action spaces. This may make the existing machines stop working. Thus, the proposed routing algorithm filters the action space for optimal computing tasks. In the simulation results, the increasing episodes result in a higher Q-value accordingly, while the TD error decreases according to the increasing training steps. The decision-making function after the training process is implemented to decide the action for the moving tasks according to the system state to point out the benefits of this research to reduce the OPEX and increase rental opportunities.

The larger action space results in more learning steps in the simulation results to reduce the TD error in each case. The Q value is not significantly different between Cases II and III in the final episode. Although larger action spaces may provide higher Q value performance, it results in an increased computational complexity. On the other hand, the small action space is less complicated but may offer a low Q value. In this paper, the proposed routing algorithm filters the action space for supporting the computing task with the current machine. However, the policy iteration algorithm is a more accurate method but cannot be applied to complex solutions in the current situation. Besides, the existing works are merely a study from the perspective of pickup, delivery and rebalance to the initial state, without a careful consideration to maximize leasing opportunities and reduce the cost of moving tasks.

Figure 14: Distance route and reward competition between the proposed traditional methods for the moving tasks on smart electric motorcycle-sharing system at Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

Most vehicle-sharing systems usually consist of many service stations to accommodate the user needs in the sharing economy. These transportations provide convenience for renting a vehicle to the travel. In this case study, the smart electric motorcycle-sharing system is a one-way trip to travel from the origin station to another station. However, the user needs to rent and return the vehicle in each station is different. This leads to unbalanced system vehicles, resulting in the full or empty inventory. For profiting the economy sharing business, the proposed concept can achieve a method to decide the action for the moving tasks to the fleet optimization. The routing algorithm is used to filter the action space for a computing task, while the DRL algorithm is used to create the decision-making function with the large state and action space. The results have demonstrated a method for creating decision-making functions by selecting the appropriate size of action space. The created decision-making function is implemented in the smart electric motorcycle-sharing system at SUT, Thailand, to decide the action for the personnel team of moving tasks to increase the probability of vehicle rentals and reduce the cost of vehicle allocation. Besides, the proposed concept can be used to optimize the fleet management in other systems having more complicated problems.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by Suranaree University of Technology (SUT) and Thai Advance Innovation Co., Ltd. The authors would also like to thank the Smart Electric Motorcycle Service (MoreSai) team for their useful data and kind cooperation to experiment along with improving the quality of this paper.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by SUT Research and Development Funds and by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. E. Suryani, R. A. Hendrawan, P. F. EAdipraja, A. Wibisono and L. P. Dewi, “Modelling reliability of transportation systems to reduce traffic congestion,” Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1196, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

2. R. Nair and E. Miller-Hooks, “Fleet management for vehicle sharing operations,” Transportation Science, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 524–540, 2011. [Google Scholar]

3. S. Juliet, “Debating the sharing economy,” Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 7–22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

4. P. DeMaio, “Bike-sharing: History, impacts, models of provision, and future,” Journal of Public Transportation, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 41–56, 2009. [Google Scholar]

5. U.S. EPA, Transportation Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, USA, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions. [Google Scholar]

6. E. Fishman, “Bikeshare: A review of recent literature,” Transport Reviews, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 92–113, 2016. [Google Scholar]

7. G. Mosheiov, “The travelling salesman problem with pick-up and delivery,” European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 299–310, 1994. [Google Scholar]

8. J. Schuijbroek, R. C. Hampshire and W. J. Van Hoeve, “Inventory rebalancing and vehicle routing in bike sharing systems,” European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 257, no. 3, pp. 992–1004, 2017. [Google Scholar]

9. H. Hernández-Pérez and J. J. Salazar-González, “A branch-and-cut algorithm for a traveling salesman problem with pickup and delivery,” Discrete Applied Mathematics, vol. 145, no. 1, pp. 126–139, 2004. [Google Scholar]

10. C. C. Lu, “Robust multi-period fleet allocation models for bike-sharing systems,” Networks and Spatial Economics, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 61–82, 2016. [Google Scholar]

11. E. Fishman, S. Washington and N. Haworth, “Bike share: A synthesis of the literature,” Transport Reviews, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 148–165, 2013. [Google Scholar]

12. E. Martin, A. Cohen, J. L. Botha and S. Shaheen, “Bikesharing and bicycle safety,” in Transportation Institute Publications, UC, Oakland, California, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

13. Q. Chen and Y. Wang, “A cellular automata (CA) model for motorized vehicle flows influenced by bicycles along the roadside,” Journal of Advanced Transportation, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 949–966, 2016. [Google Scholar]

14. G. Palomares, J. Carlos, J. Gutiérrez and M. Latorre, “Optimizing the location of stations in bike-sharing programs: A GIS approach,” Applied Geography, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 235–246, 2012. [Google Scholar]

15. M. Benchimol, P. Benchimol, B. Chapert, A. D. L. Taille, F. Laroche et al., “Balancing the stations of a self service “bike hire” system,” RAIRO-Operations Research, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 37–61, 2011. [Google Scholar]

16. T. Raviv, M. Tzur and I. A. Forma, “Static repositioning in a bike-sharing system: Models and solution approaches,” EURO Journal on Transportation and Logistics, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 187–229, 2013. [Google Scholar]

17. J. Liu, Q. Li, M. Qu, W. Chen, J. Yang et al., “Station site optimization in bike sharing systems,” in Proc. 2015 IEEE Int. Conf. on Data Mining, AC, NJ, USA, pp. 883–888, 2015. [Google Scholar]

18. Y. Duan, J. Wu and H. Zheng, “A greedy approach for vehicle routing when rebalancing bike sharing systems,” in Proc. 2018 IEEE Global Communications Conf., AD, UAE, pp. 1–7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

19. R. S. Sutton and A. G. Barto, Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 2018. [Google Scholar]

20. M. Hessel, J. Modayil, H. Hasselt, T. Schaul, G. Ostrovski et al., “Rainbow: combining improvements in deep reinforcement learning,” in Proc. Thirty-Second AAAI Conf. on Artificial Intelligence, Ithaca, NY, USA, pp. 1–8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |