DOI:10.32604/cmc.2021.015563

| Computers, Materials & Continua DOI:10.32604/cmc.2021.015563 |  |

| Article |

Rotational Effect on the Propagation of Waves in a Magneto-Micropolar Thermoelastic Medium

1Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Sohag University, Sohag, Egypt

2Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, South Valley University, 83523, Egypt

3Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

4Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt

*Corresponding Author: A. M. Abd-Alla. Email: mohmrram@yahoo.com

Received: 28 November 2020; Accepted: 14 February 2021

Abstract: The present paper aims to explore how the magnetic field, ramp parameter, and rotation affect a generalized micropolar thermoelastic medium that is standardized isotropic within the half-space. By employing normal mode analysis and Lame’s potential theory, the authors could express analytically the components of displacement, stress, couple stress, and temperature field in the physical domain. They calculated such manners of expression numerically and plotted the matching graphs to highlight and make comparisons with theoretical findings. The highlights of the paper cover the impacts of various parameters on the rotating micropolar thermoelastic half-space. Nevertheless, the non-dimensional temperature is not affected by the rotation and the magnetic field. Specific attention is paid to studying the impact of the magnetic field, rotation, and ramp parameter of the distribution of temperature, displacement, stress, and couple stress. The study highlighted the significant impact of the rotation, magnetic field, and ramp parameter on the micropolar thermoelastic medium. In conclusion, graphical presentations were provided to evaluate the impacts of different parameters on the propagation of plane waves in thermoelastic media of different nature. The study may help the designers and engineers develop a structural control system in several applied fields.

Keywords: Magnetic field; micropolar; thermoelastic; rotation; ramp parameter; normal mode analysis

Nomenclature

| Stress tensor components | |

| mij: | Couple stress tensor components |

| Micro–rotation | |

| Lame’s constants | |

| Micropolar material constants | |

| Components of the displacement vector | |

| Linear thermal expansion coefficient | |

| Density of the medium | |

| e: | Cubical dilatation |

| K*: | Thermal conductivity |

| cE: | Specific heat at constant strain |

| Angular temperature | |

| T0: | The medium’s temperature in its material state supposed to be |

Because it is relevant in several applications, researchers have paid due attention to generalized thermoelasticity. Its theories include governing equations of the hyperbolic type and disclose the thermal signals’ finite speed. In a standardized thermoelastic isotropic half-space, Abd-Alla et al. [1] investigated how wave propagation is affected by a magnetic field. Abouelregal [2] discussed the improved fractional photo-thermoelastic system for a magnetic field- subjected rotating semiconductor half-space. Singh et al. [3] studied reflecting plane waves from a solid thermoelastic micropolar half-space with impedance boundary circumstances. Said [4] studied the propagation of waves in a two-temperature micropolar magnetothermoelastic medium for a three-phase-lag system. The authors of [5] explored the impact of rotation on a two-temperature micropolar standardized thermoelasticity utilizing a dual-phase lag system. Rupender [6] studied the impact of rotation on a micropolar magnetothermoelastic medium because of thermal and mechanical sources. Bayones et al. [7] investigated the impact of the magnetic field and rotation on free vibrations within a non-standardized spherical within an elastic medium. Bayones et al. [8] discussed the thermoelastic wave propagation within the half-space of an isotropic standardized material affected by initial stress and rotation. Kalkal et al. [9] investigated reflecting plane waves in a thermoelastic micropolar nonlocal medium affected by rotation. Lotfy [10] explored two-temperature standardized magneto-thermoelastic responses within an elastic medium under three models. Zakaria [11] discussed the effect of hall current on a standardized magneto-thermoelasticity micropolar solid under heating of the ramp kind. Ezzata et al. [12] studied the impacts of the fractional order of heat transfer and heat conduction on a substantially long hollow cylinder that conducts perfectly. Morse et al. [13] employed Helmholtz’s theorem. The authors of [14] investigated the transient magneto-thermoelasto-diffusive interactions of the rotating media with porous in the absence of the dissipation of energy influenced by thermal shock. Kumar et al. [15] studied the axisymmetric issue within a thermoelastic micropolar standardized half-space. The authors of [16] studied the free surface’s reflection of the thermoelastic rotating medium reinforced with fibers with the phase-lag and two temperatures. Deswal et al. [17] studied the law of fractional-order thermal conductivity within a two-temperature micropolar thermo-viscoelastic. Using radial ribs, the authors of [18] examined the improved rigidity of fused circular plates. The authors of [19] investigated the motion equation for a flexible element with one dimension utilized for the dynamical analysis of a multimedia structure.

The paper aims to study the thermoelastic interactions within an elastic standardized micropolar isotropic medium in the presence of rotation affected by a magnetic field. The authors could obtain accurate solutions of the measured factors using the Lame’s potential theory and the normal mode analysis. They could obtain and present in graphs the numerical findings of the distributions of stress, displacement, and temperature, for a crystal-like magnesium material.

2 Constitutive Relations and Field Equations

Constitutive relations and field equations are considered within a generalized micropolar magneto-thermoelastic medium in the presence of rotation as:

(i) The Constitutive Relations

(ii) Motion’s Stress Equation

(iii) Motion’s Couple Stress Equation

(iv) The Equation of Thermal Conductivity

For these equations, the authors use the summation convention and utilize the comma to signify material derivative.

Take into account an isotropic standardized micropolar generalized magneto-thermoelastic in the presence of rotation. The rectangular Cartesian coordinate scheme

in which

where

Combining Eqs. (3), (4) and Eqs. (5a), (7) provides

The following form expresses Eq. (5) of thermal conductivity given expression (5a)

Substituting (5a) into (1) and (2), we can express the arising stress as

where

These variables that are non-dimensional are employed to change the previous equations into non-dimensional structures

where

Eqs. (8)–(11) concerning previous the variables that are non-dimensional decline to (dropping the primes)

Utilizing Helmholtz decomposition [13] and providing the potential

Using Eq. (5a), the components of displacement u and w take the following form

where

Substituting Eq. (22) into Eqs. (17)–(20) gives us

where

For resolving the governing equations, the authors measured physically the decomposed variable concerning the normal modes in the following form:

in which

Using (27), Eqs. (23)–(25) and Eq. (20) are, as follows

in which

Eliminating

in which

in which

Eq. (27) is represented, as follows

in which

where

The solution of Eq. (28) is written as

in which

where

Take into account a magneto-thermoelastic micropolar solid having a half-space that rotates

5.1 Thermal Boundary Conditions

The authors apply a heat shock of the ramp kind to the isothermal boundary of the plane z = 0, as follows

in which

In this equation, t0 represents a ramp parameter that shows the time required for raising the heat.

5.2 Mechanical Boundary Conditions

The boundary plane z = 0 is free of traction. In terms of mathematics, the boundary conditions take the following form

Applying Eqs. (16)–(27) make the former boundary conditions represented, as follows

where

Utilizing the non-dimensional quantities identified in (16), expressing stress Eqs. (12)–(15) and displacement Eq. (22), as well as the relations (44)–(46) becomes:

in which

A four-equation non-homogeneous structure is yielded by the boundary conditions (47)–(50), supported by expressions (51)–(55) and (38) as follows

The expressions of Mn, (n = 1, 2, 3, 4) attained by resolving the structure (56), when replaced in Eq. (38) and Eqs. (51)–(55), give these expressions of field variables

in which

6 Numerical Results and Discussion

With an aim to highlight the theoretical findings of the previous sections, the authors provide some numerical findings using MATLAB. The material selected for this goal of magnesium crystal whose physical data resemble those provided in [17]:

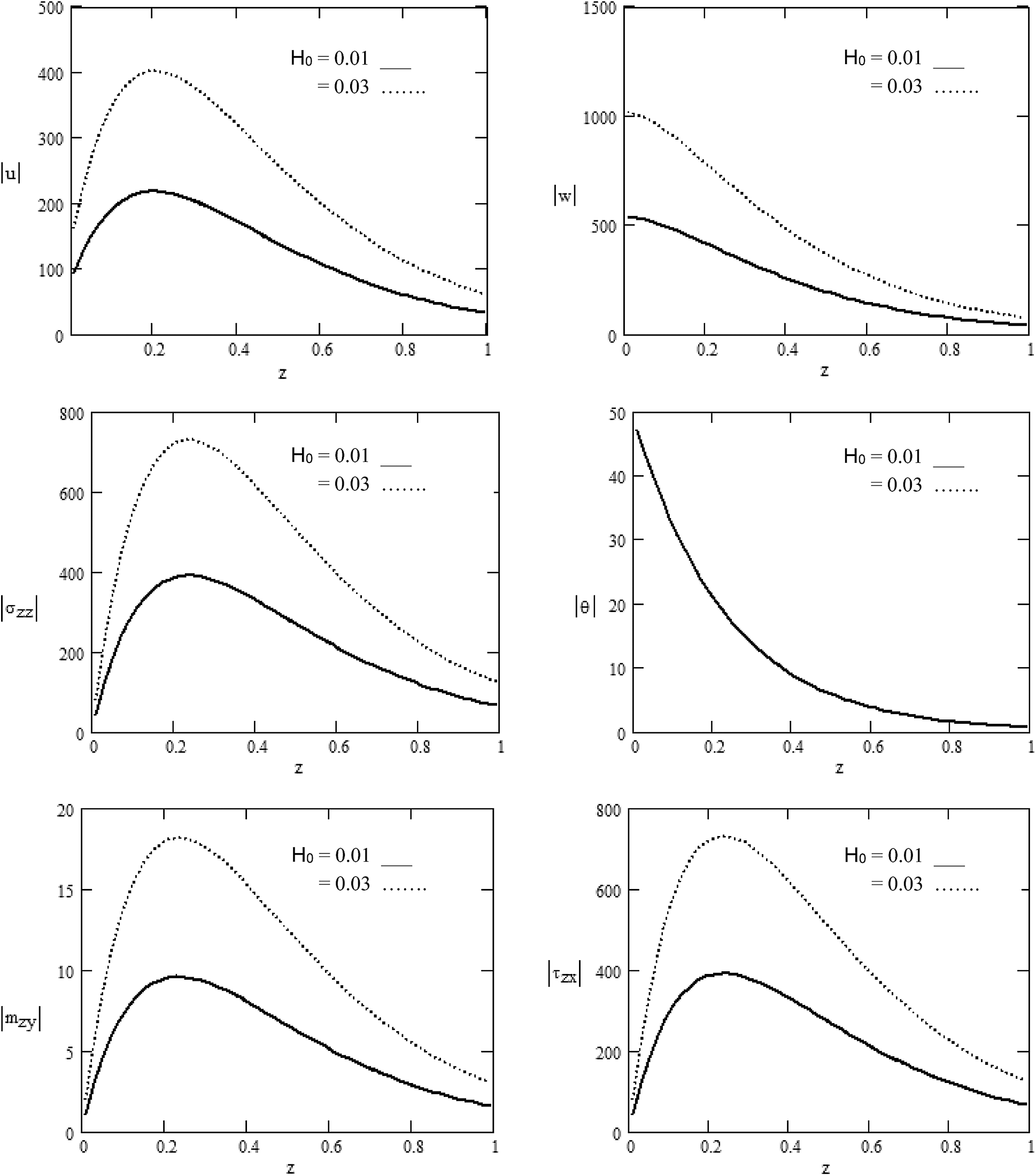

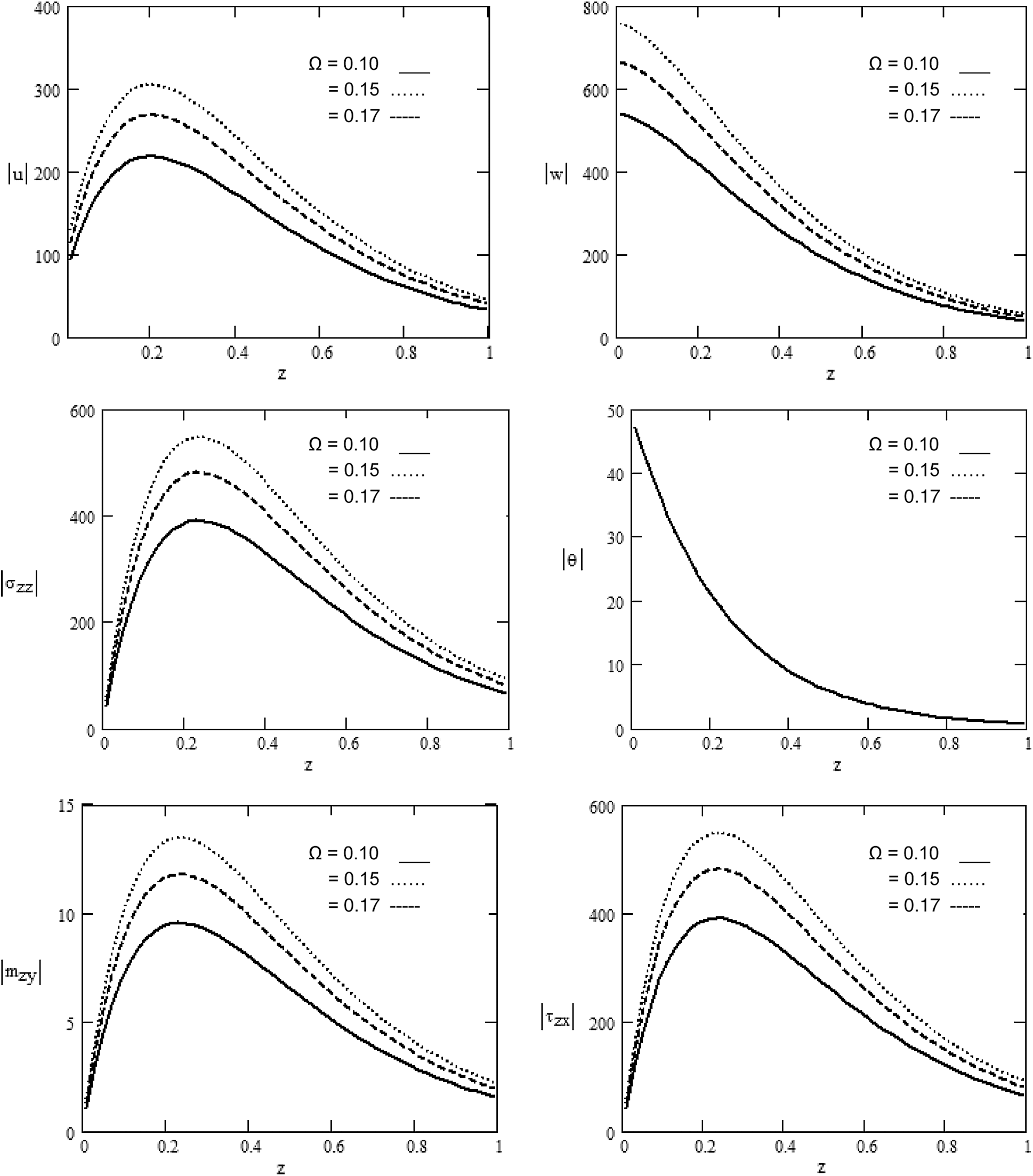

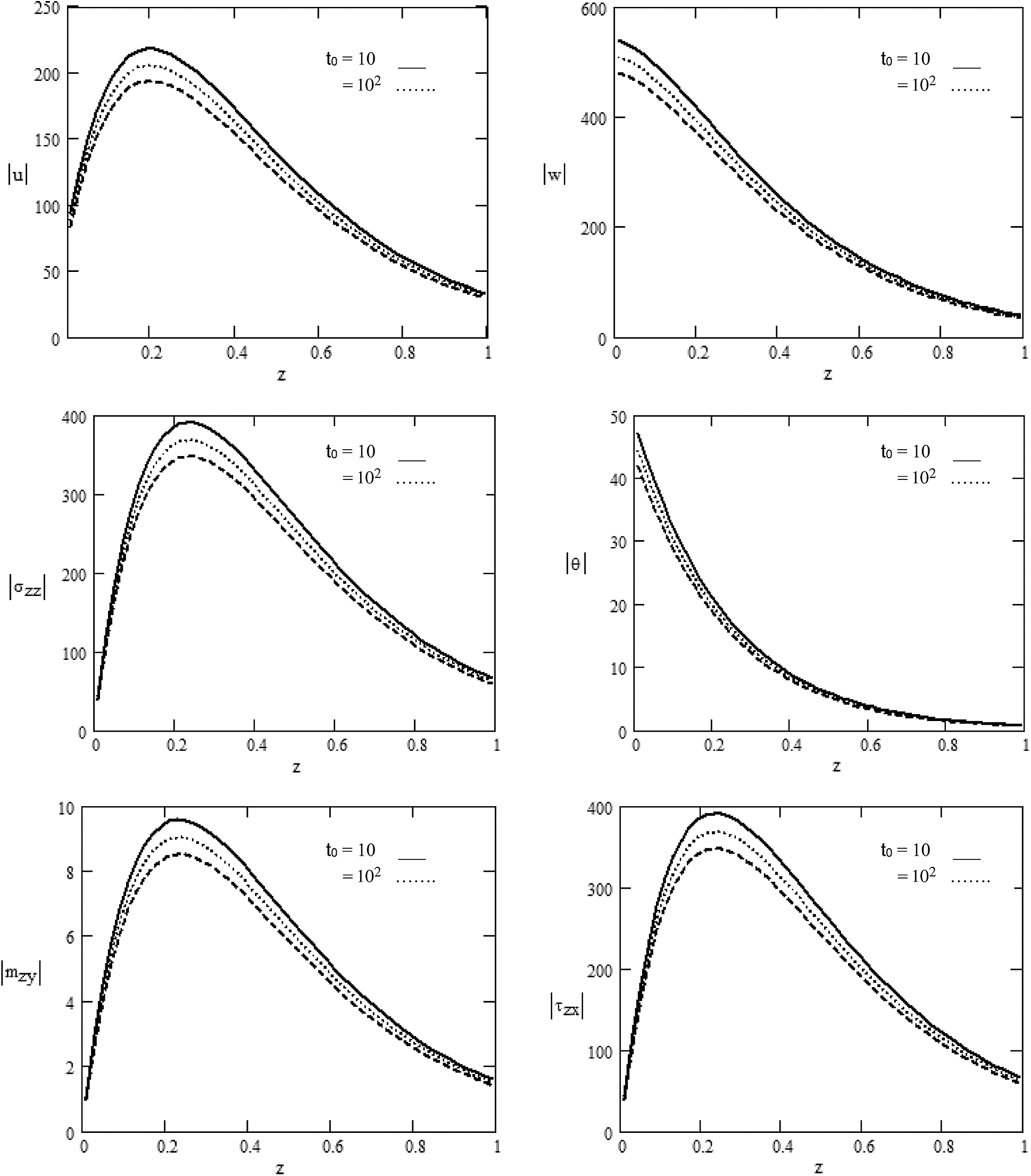

Taking into account the previous physical data, non-dimensional field variables are estimated, and the findings are presented graphically at various positions of z at t = 0.1 and x = 1.0. The motion range is

Figure 1: Various values of the magnitude of

Figure 2: Various values of the magnitude of

Figure 3: Various values of the magnitude of

Fig. 1: displays the various values of the components of displacement

Variations in displacement components

In Fig. 3, we have depicted displacement components

The study concludes that:

a) The magnetic field and rotation play an influential part in distributing the physical quantities whose amplitude varies (rise or decline) as the rotation and magnetic field increase. With the rotation and the magnetic field, the quantities to surge near or away from the application source point are restricted.

b) All physical quantities satisfy the boundary conditions.

c) The theoretical findings of the study can give stimulating information for seismologists, researchers, and experimental scientists who are interested in the field.

Funding Statement: The authors express their gratitude to the Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, Egypt for funding the present study under Science Up Grant No. (6459).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. A. M. Abd-Alla, S. M. Abo-Dahab, S. M. Ahmed and M. M. Rashid, “Effect of a magnetic field on the propagation of waves in a homogeneous Isotropic thermoelastic Half-Space,” Physical Mesomechanics, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 54–65, 2020. [Google Scholar]

2. A. E. Abouelregal, “Modified fractional photo-thermoelastic model for a rotating semiconductor half-space subjected to a magnetic field,” Silicon, vol. 12, pp. 2837–2850, 2020. [Google Scholar]

3. B. Singh, A. K. Yadav and D. Gupta, “Reflection of plane waves from a micropolar thermoelastic solid half-space with impedance boundary conditions,” Journal of Ocean Engineering and Science, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 122–131, 2019. [Google Scholar]

4. S. M. Said, “Wave propagation in a magneto-micropolar thermoelastic medium with two temperatures for three-phase-lag model,” Computer, Materials & Continua, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 1–24, 2016. [Google Scholar]

5. M. I. A. Othman, W. M. Hasona and E. M. Abd-Elaziz, “Effect of rotation on micropolar generalized thermoelasticity with two temperatures using a dual-phase lag model,” Canadian Journal of Physics, vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 85–98, 2014. [Google Scholar]

6. R. K. Rupender, “Effect of rotation in magneto-micropolar thermoelastic medium due to mechanical and thermal sources,” Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 1619–1633, 2009. [Google Scholar]

7. F. S. Bayones and A. M. Abd-Alla, “Effect of rotation and magnetic field on free vibrations in a spherical non-homogeneous embedded in an elastic medium,” Results in Physics, vol. 9, pp. 698–704, 2018. [Google Scholar]

8. F. S. Bayones, A. M. Abd-Alla, R. Alfatta and H. Al-Nefaie, “Propagation of a thermoelastic wave in a half-space of a homogeneous isotropic material Subjected to the effect of rotation and initial stress,” Computers, Materials & Continua, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 551–567, 2020. [Google Scholar]

9. K. K. Kalkal, D. Sheoran and S. Deswal, “Reflection of plane waves in a nonlocal micropolar thermoelastic medium under the effect of rotation,” Acta Mechanica, vol. 231, pp. 2849–2866, 2020. [Google Scholar]

10. K. Lotfy, “Two temperature generalized magneto-thermoelastic interactions in an elastic medium under three theories,” Applied Mathematics & Computation, vol. 227, pp. 871–888, 2014. [Google Scholar]

11. M. Zakaria, “Effect of hall current on generalized magneto-thermoelasticity micropolar solid subjected to ramp-type heating,” International Applied Mechanics, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 92–104, 2014. [Google Scholar]

12. M. A. Ezzata and A. A. El-Bary, “Effects of variable thermal conductivity and fractional order of heat transfer on a perfect conducting infinitely long hollow cylinder,” International Journal of Thermal Sciences, vol. 108, pp. 62–69, 2016. [Google Scholar]

13. P. Morse and H. Feshbach, Methods of Theoretical Physics. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill, pp. 132–150, 1953. [Google Scholar]

14. Q. Xiong and X. Tian, “Transient magneto-thermo-elasto-diffusive responses of rotating porous media without energy dissipation under thermal shock,” Mechanica, vol. 51, pp. 2435–2447, 2016. [Google Scholar]

15. R. Kumar and S. Deswal, “Axisymmetric problem in a micropolar generalized thermoelastic half-space,” International Journal of Applied Mechanical Engineering, vol. 12, pp. 413–429, 2007. [Google Scholar]

16. S. D. Suresh, K. S. Kapil and K. Kalkal, “Reflection at the free surface of fiber-reinforced thermoelastic rotating medium with two-temperature and phase-lag,” Applied Mathematical Modelling, vol. 65, pp. 106–119, 2019. [Google Scholar]

17. S. Deswal and K. K. Kalkal, “Fractional order heat conduction law in micropolar thermo-viscoelasticity with two temperatures,” International Journal of Heat & Mass Transfer, vol. 66, pp. 451–460, 2013. [Google Scholar]

18. C. Itu, A. Öchsner, S. Vlase and M. Marin, “Improved rigidity of composite circular plates through radial ribs,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications, vol. 233, no. 8, pp. 1585–1593, 2019. [Google Scholar]

19. S. Vlase, M. Marin, A. Öchsner and M. L. Scutaru, “Motion equation for a flexible one-dimensional element used in the dynamical analysis of a multibody system,” Continuum Mechanics & Thermodynamics, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 715–724, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |