DOI:10.32604/cmc.2021.012167

| Computers, Materials & Continua DOI:10.32604/cmc.2021.012167 |  |

| Article |

Coronavirus: A “Mild” Virus Turned Deadly Infection

1Department of Unmanned Vehicle Engineering, Sejong University, Seoul, 05006, Korea

2Department of Information Technology, Khwaja Fareed University of Engineering and Information Technology, Rahim Yar Khan, 64200, Pakistan

3School of Computer and Information Technology, Beaconhouse National University, Tarogil, Lahore, 53700, Pakistan

4Riphah School of Computing & Innovation, Faculty of Computing, Riphah International University, Lahore Campus, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

5Department of Computer Science, College of Computer Science and Information Technology, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, 31441, Saudi Arabia

6Faculty of Information Technology, University of Central Punjab, Lahore, 54782, Pakistan

7Directorate of IT, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur, 63100, Pakistan

*Corresponding Author: Muhammad Adnan Khan. Email: adnan.khan@riphah.edu.pk

Received: 30 August 2020; Accepted: 24 December 2020

Abstract: Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that can be transmitted from one person to another. Earlier strains have only been mild viruses, but the current form, known as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has become a deadly infection. The outbreak originated in Wuhan, China, and has since spread worldwide. The symptoms of COVID-19 include a dry cough, sore throat, fever, and nasal congestion. Antimicrobial drugs, pathogen–host interaction, and 2 weeks of isolation have been recommended for the treatment of the infection. Safe operating procedures, such as the use of face masks, hand sanitizer, handwashing with soap, and social distancing, are also suggested. Moreover, travel bans for cities, states, and countries have been put in place, along with lockdowns to control the outbreak. Travel restrictions, mask use, sanitizer or soap use, and avoidance of touching the face and nose have produced encouraging results, whereas the effectiveness of antibiotics has not been proved. The results of isolation for the recovery of infected people have also been promising. Travel bans and lockdowns have caused a slump in economies, and unemployment has risen sharply, resulting in an increase in mental health cases globally. To date, vaccines have been developed and are in use in certain countries, but following standard operating procedures remain critical. The countries following the guidelines can eradicate this virus. New Zealand was the first country to eliminate the virus from their territory.

Keywords: Coronavirus; severe acute respiratory syndrome; middle east respiratory syndrome; world health organization

Humans or animals can become ill owing to a large family of viruses, but coronaviruses are particularly deadly. Several coronaviruses can cause mild infections in humans that are related to respiration, such as the common cold, but they can also cause severe diseases, such as SARS and MERS. The most recent form of coronavirus, discovered after its outbreak in Wuhan, China in December 2019, causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), an infectious disease [1]. In the early stages of the disease, the symptoms of COVID-19 can be mild, but they can grow exponentially worse. In some cases, people may feel normal and exhibit no symptoms, although they may still have the disease, making it even more dangerous to others [1].

The symptoms of COVID-19 are a dry cough, runny nose, sore throat, diarrhea, fatigue, nasal congestion, fever, and aches and pains, but of these symptoms, dry cough, fatigue, and fever are the most common symptoms [2]. The recovery rate of COVID-19 is around 80%, and numerous patients recover without any form of special treatment [1]. The ratio of infected people who develop breathing difficulties and experience severe illness is about 1 out of 6. Those who become seriously ill typically have underlying medical issues, such as diabetes, heart problems, and high blood pressure [3].

The disease can be spread from one person to another because small droplets from the mouth or nose of an infected person who exhales or coughs may land on surfaces or people in the vicinity. Therefore, individuals can contract this disease by breathing in droplets exhaled by an individual with COVID-19. They can also contract this disease when they touch a contaminated surface and then touch their mouth, nose, or eyes. Considering the severe consequences of exhaling or coughing, it is advised that individuals stay at least 3 ft (1 m) away from an ill person [4].

The main route for the spread of COVID-19 is through respiratory droplets from the cough of an infected person; however, there is a smaller chance of contracting this disease from someone who is infected but is not showing any symptoms of COVID-19 [1]. Moreover, only mild symptoms are experienced by most infected people who are in the early stages of the disease, but there may still be a chance of contracting the disease from someone who feels relatively well [5].

The research based on coronaviruses (particularly the one that causes COVID-19) suggests that the virus can persist on surfaces for a few hours for up to several days, but the duration is uncertain. There are a few factors to consider, including the humidity or temperature of the environment and the type of surface. Using a simple disinfectant is advised to clean the surface and protect oneself and others by killing the virus [6].

Antibiotics work only on bacterial infections and do not work against viruses. Some guidelines to keep safe from this virus include the avoidance of touching the nose, mouth, or eyes, and washing the hands with an alcohol-based liquid or soap and water. Antibiotics should not be used for COVID-19 because no benefit exists from using them. They should only be used for the treatment of bacterial infections as directed by a physician. The usage of some traditional, Western, or home remedies may alleviate the symptoms of COVID-19, but no evidence indicates that any specific antiviral medicine or vaccine can treat or prevent COVID-19 [7]. The use of a face mask can reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19; masks are effective and still allow for communication with an infected person provided that adequate social distance is also maintained.

To diagnose COVID-19, a test must be administered through the upper respiratory tract, which incorporates the nasal cavity directly at the junction of the nose and throat. The tests are thought to be accurate because a high level of viral organisms gathers in the respiratory tract. The test lasts for a few seconds, and tests are sent to a laboratory for results. Infected people with mild symptoms are also advised to stay isolated for two weeks. These guidelines must be followed even if the patient has previously recovered from COVID-19, as a person can become infected more than once; hence, another wave of the deadly infection can occur [8].

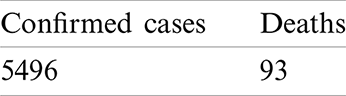

Tab. 1 contains data related to the effects of COVID-19 in Pakistan, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). It includes the number of confirmed cases (5496) and deaths (93) as of April 13, 2020 at 2:00 a.m. Central European Summer Time (CEST) [2].

Table 1: Effects of COVID-19 in Pakistan [2]

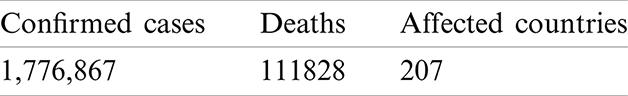

The information in Tab. 2 is related to the effects of COVID-19 globally (207 countries) according to the WHO, which includes the number of confirmed cases (1,776,867), deaths (111,828), and affected countries (207) as of April 13, 2020 at 2:00 a.m. CEST [2].

Table 2: Effect of COVID-19 on the world [2]

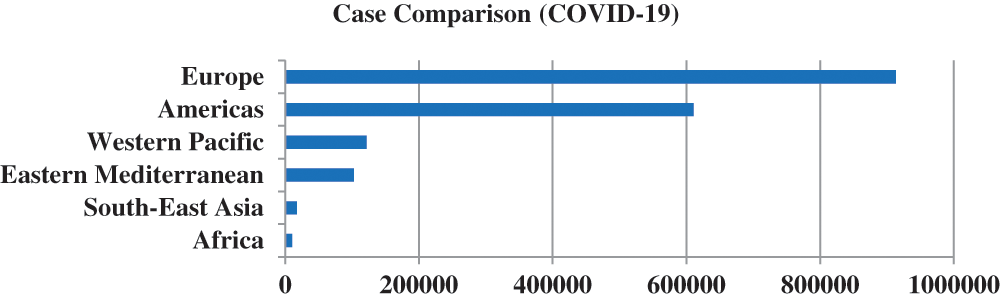

Fig. 1 presents the effects of COVID-19 on a geographical basis worldwide according to WHO, and includes a comparison of the confirmed cases in 6 geographical areas: Europe (913,349), the Americas (610,742), the Western Pacific (121,710), the Eastern Mediterranean (102,710), Southeast Asia (17,385), and Africa (10,259), as of April 13, 2020 at 2:00 a.m. CEST [2].

Figure 1: Geographical comparison of COVID-19 cases [2]

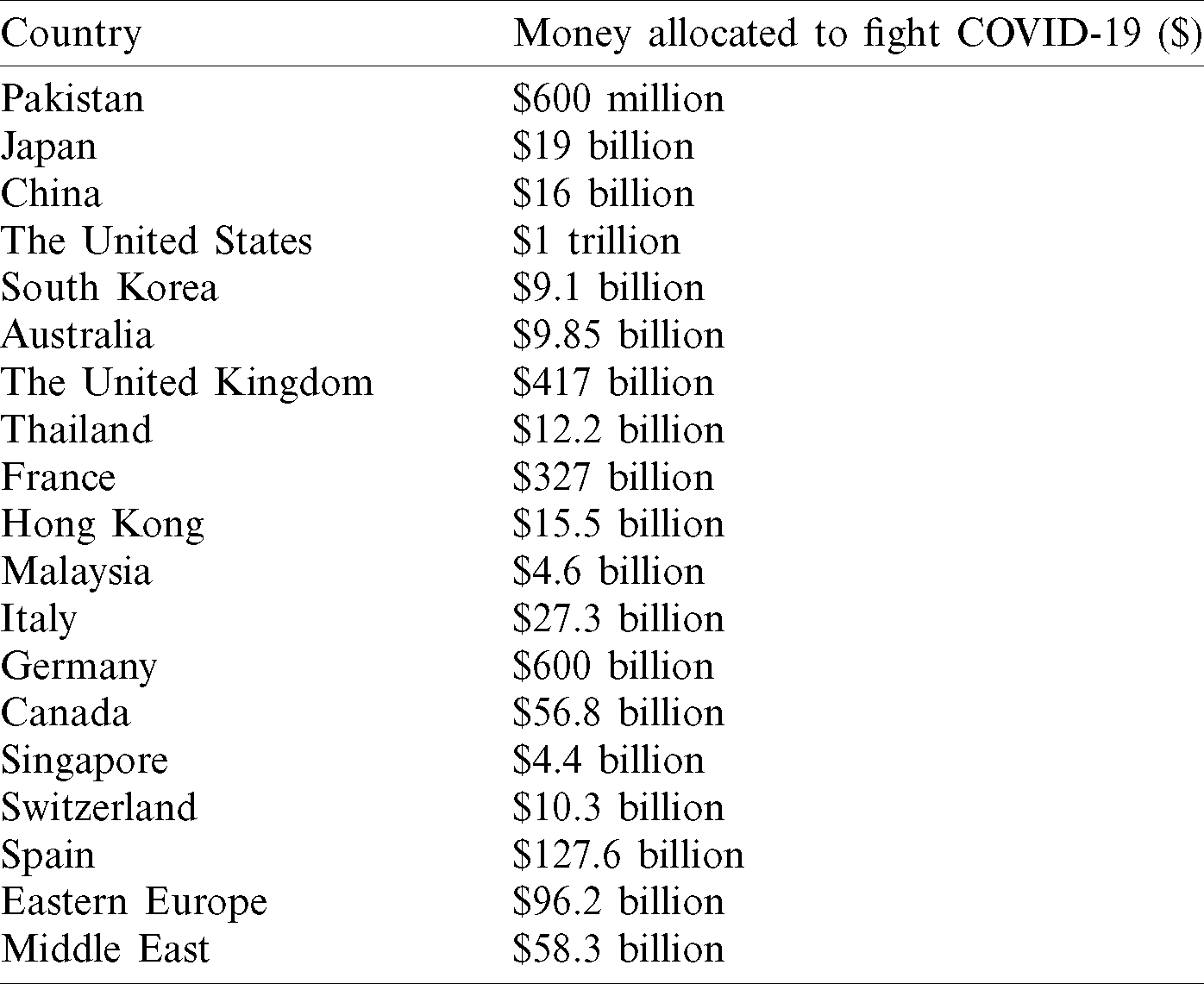

Tab. 3 contains information related to the amount of money that has been pledged by different countries to fight COVID-19. Pakistan has pledged $600 million, which includes about $15 million for labor workers and about $7.5 million for tax refunds to exports and industry. Another $7.5 million is for small and medium industries and the agricultural sector, and the rest of the money will be spent as required in other fields (especially medicine). Japan has pledged $19 billion, which includes loan support worth 1.1 trillion yen (Japanese currency). Moreover, people affected by the closing of schools and professionals in the medical field will obtain 430.8 billion yen in aid, and all companies that have been affected by COVID-19 will be able to obtain low-cost loans because 500 billion yen has been allocated for that purpose by the Japanese government. In addition, China has pledged $9.85 billion [3].

Table 3: Money pledged to fight COVID-19 by country [3]

The United States (U.S.) has pledged $1 trillion, which includes providing Americans with direct cash payments, financial stability for virus testing, access to free food for people in need, and paid sick leave. South Korea has pledged $9.1 billion, which includes providing help in terms of rent subsidies, leniency in taxation, and necessary support for households, businesses, and the medical profession. The Middle East has pledged $58.3 billion, which includes Bahrain ($11.4 billion), Egypt ($6.4 billion), Saudi Arabia ($13.3 billion), and the United Arab Emirates ($27.2 billion) [3].

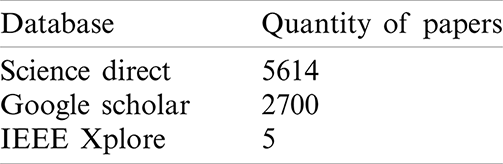

Tab. 4 presents the number of papers found in 3 different databases using the query coronavirus outbreak. These three databases are Science Direct (5614), Google Scholar (2700), and IEEE Xplore (5).

Table 4: Number of papers on the coronavirus outbreak in 3 databases

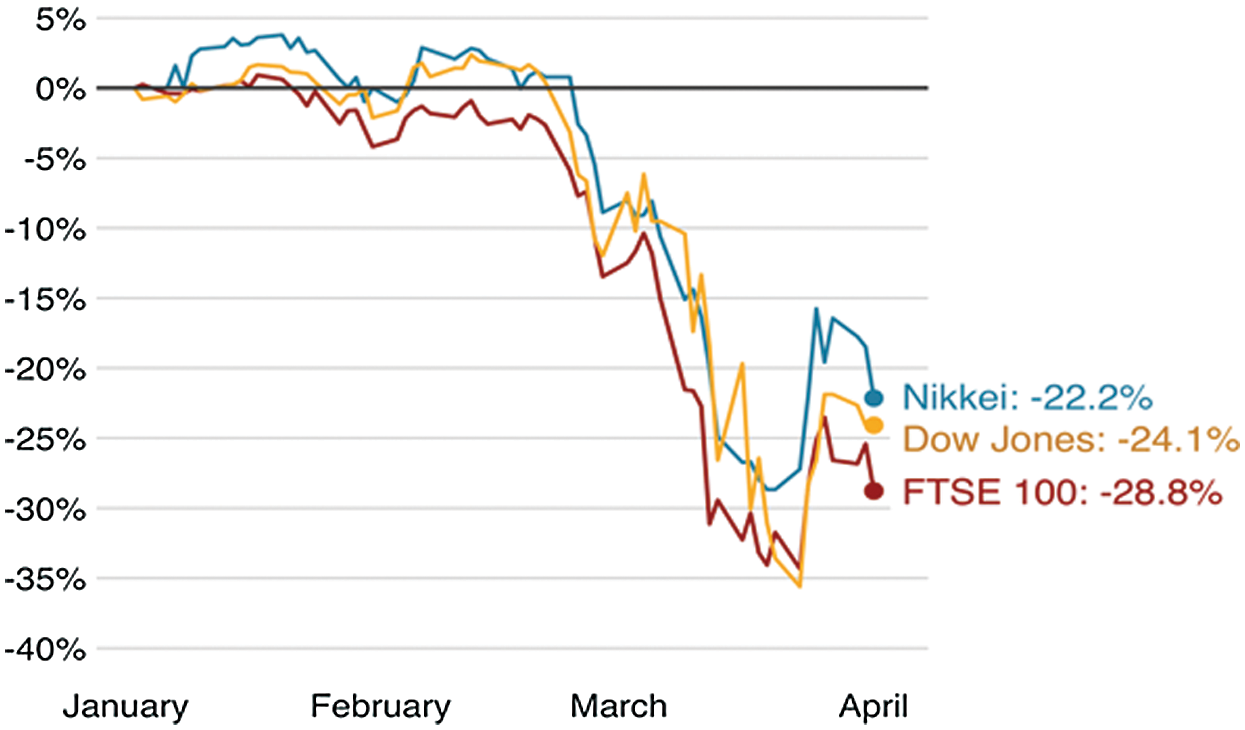

Fig. 2 presents the influence of COVID-19 on the stock exchange markets of Tokyo (Nikkei), the U.S. (Dow Jones), and London (FTSE) since the start of the outbreak. The statistics are from April 1, 2020, 9:00 am GMT according to Bloomberg. All these stock exchange markets were trending around 0% before the outbreak of COVID-19, but they suffered enormously as the markets fell to −22.2% for Nikkei, −24.1% for the Dow Jones, and −28.8% for FTSE. These trends highlight the enormous economic impact of the pandemic, which has presented a massive challenge globally [4].

Figure 2: Effect of COVID-19 on stock exchange markets [4]

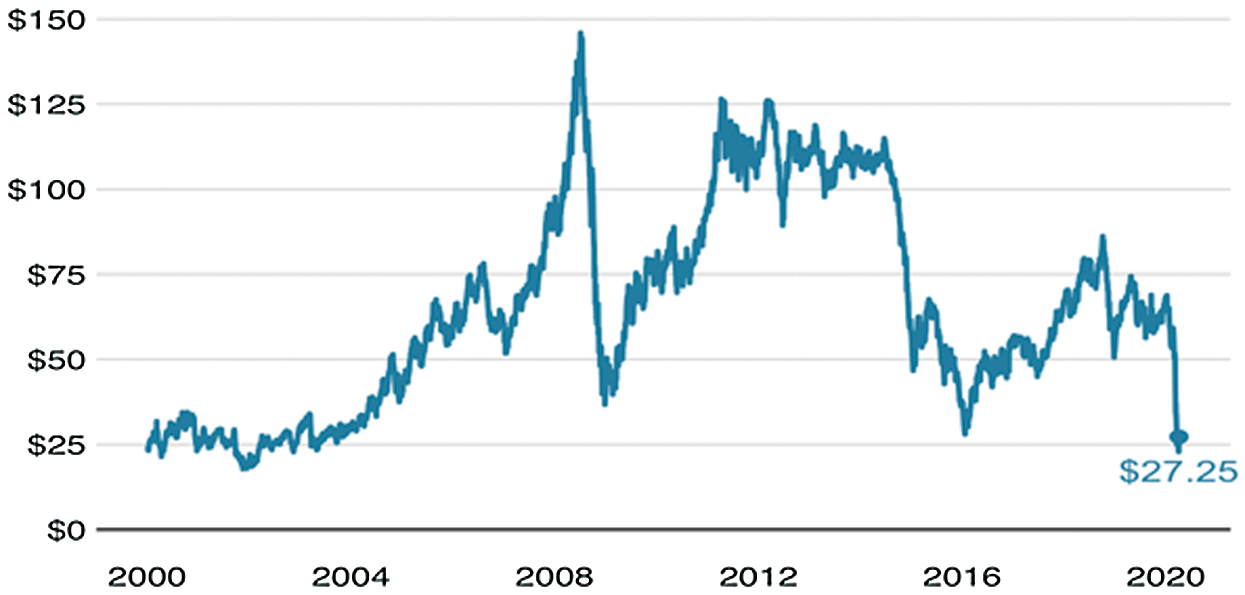

Fig. 3 presents the influences of COVID-19 on oil prices in the international market since the start of the outbreak in Wuhan, China. The statistics for oil prices are from April 2, 2020, 9:30 am GMT, according to Bloomberg. The oil price (Brent crude in U.S. dollars per barrel) dropped to its lowest since 2002 to 2003 and is still on a downward trajectory. The consequences of COVID-19 at the global level are evident in the current price of oil at $27.25 per barrel. It is expected that the price will keep decreasing. This crisis will hit the economy of several countries hard, so policymakers and world leaders must address it in the coming months. They should bring change in geopolitics, but for now, saving the U.S. oil industry is the primary objective of Washington [5].

Figure 3: Effect of COVID-19 on the price of oil in the international market [5]

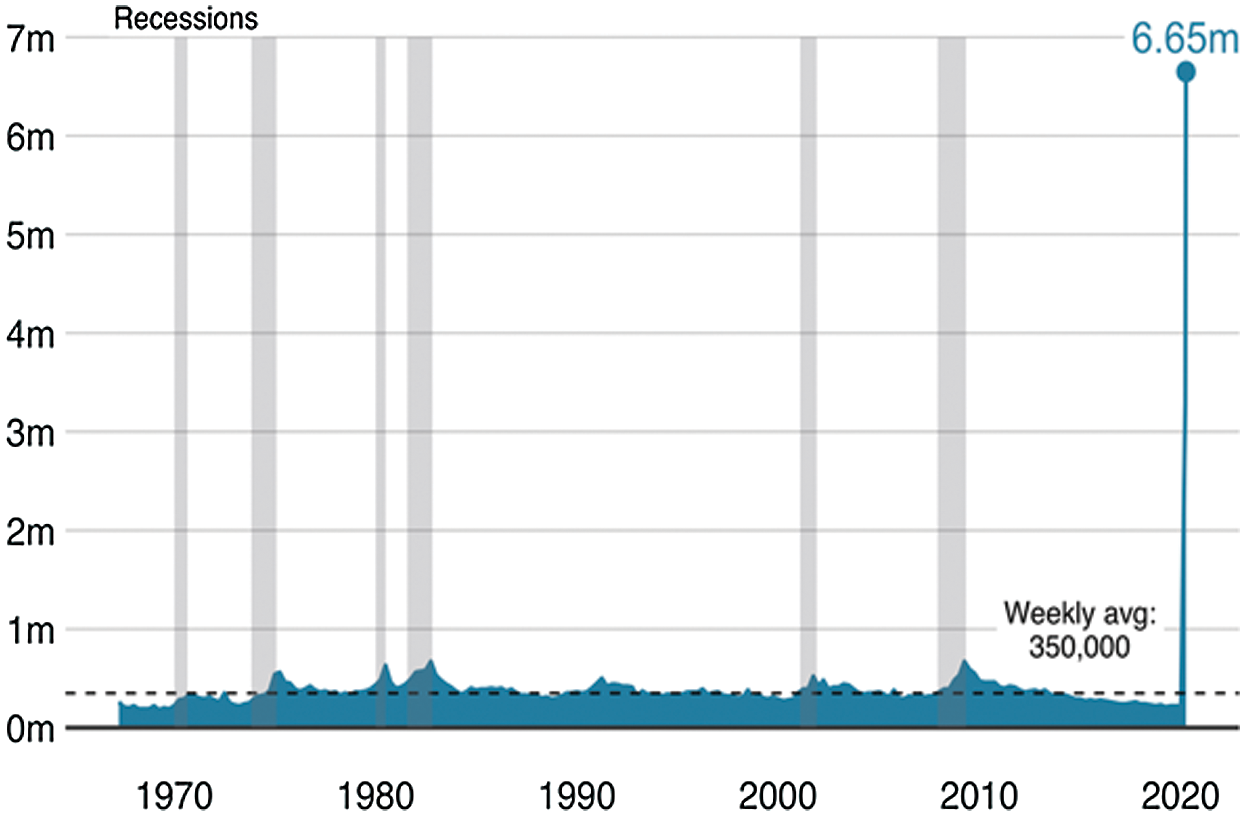

Fig. 4 presents the influence of COVID-19 on unemployment in the U.S. since the outbreak. Currently, more than 6 million Americans have lost their jobs, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. This is one of the worst job-loss rates in U.S. history and is expected to become the worst ever as the virus will not end soon [6].

Figure 4: Effect of COVID-19 on unemployment in the United States [6]

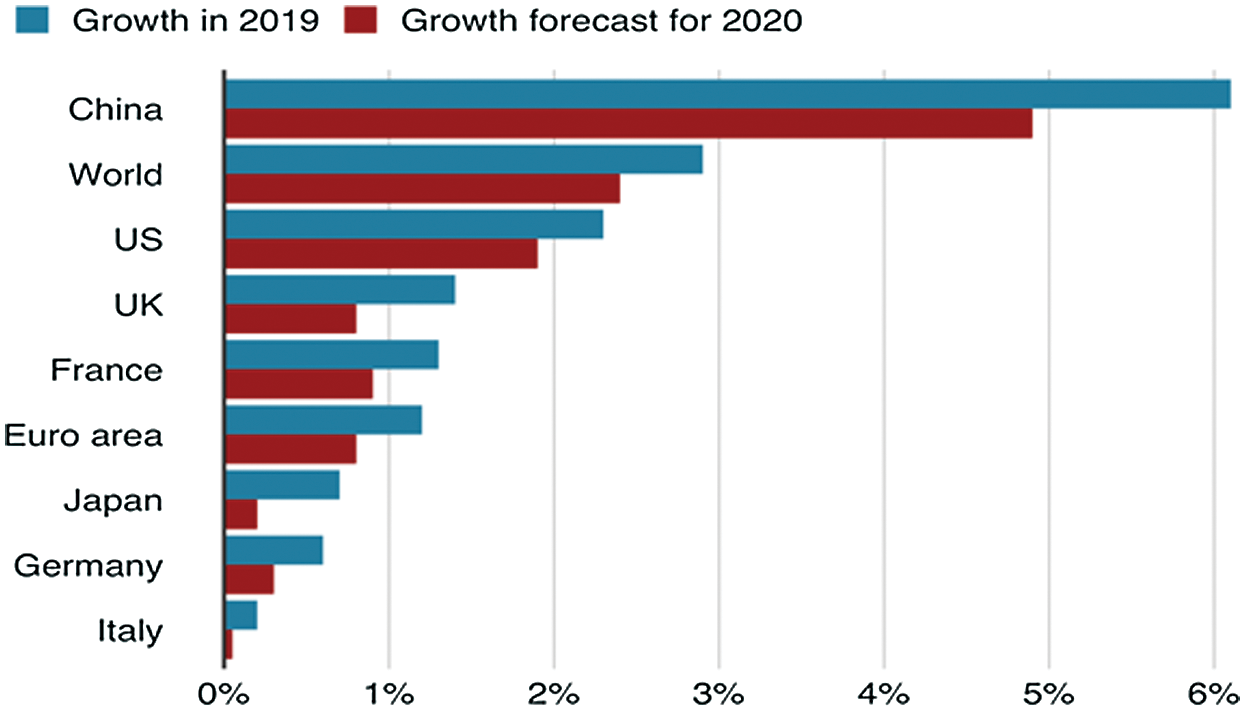

Fig. 5 illustrates the influence of COVID-19 on economic growth in terms of the gross domestic product (GDP) of different countries according to the growth forecast of the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development [7]. All countries are expected to decrease in growth in 2020 owing to the pandemic. China will likely suffer most from the virus, decreasing around 1.2% in its growth rate from the year 2019 to 2020. The U.S. will likely come in second, losing about 0.5% of its growth rate during the same period. The U.K. and France are projected to lose around 0.7% and 0.5% of their growth rate from the year 2019 to 2020, respectively. Japan, Germany, the European Union, and Italy are projected to lose 0.4%, 0.3%, 0.5%, and 0.5% of their growth rates, respectively. The world growth rate is projected to fall by around 0.5% from 2019 to 2020.

Figure 5: Forecast of the effect of COVID-19 on economic growth (GDP) by country [7]

The proposed research was based on various groups from different areas of the world, such as China, the U.S., and Europe, to better predict the spread of COVID-19 [8].

Medical professionals who treat COVID-19 patients have been infected and are experiencing mental health issues as they spend most of their time around patients with COVID-19 and work in areas where these patients are treated [9]. Even countries that have zero cases are on alert because there is no telling how fast this virus can spread. According to early estimates, the rate is estimated to be around 14%, but these initial estimates are imprecise [10]. Misinformation about the disease, which has been perpetuated mostly online, has created issues globally. In the first week of January 2020, more than 15 million posts were created on Twitter regarding the disease, with one conspiracy theory being that the Chinese created this deadly virus to advance economic or political goals [11].

Studies have revealed that the average age for COVID-19 patients is 49. The prevalent sex of patients is male (73%), and almost 50% of patients have underlying health issues, such as diabetes (20%), cardiovascular disease, or hypertension (15%) [12]. Overseas, the Chinese are experiencing racial discrimination owing to the false information that they created this deadly virus in the laboratory, and they are dealing with mental health issues as a result. Moreover, misinformation has negatively affected Chinese tourism, and people are starting to dislike the country, which has damaged their economy [13].

In addition, extensive time is required to conduct experiments and create a vaccine that can treat infected people so that the outbreak can be controlled and lives can be saved. More time is necessary for scientists to conduct the process rigorously, which is one of the main objectives for controlling the outbreak [14].

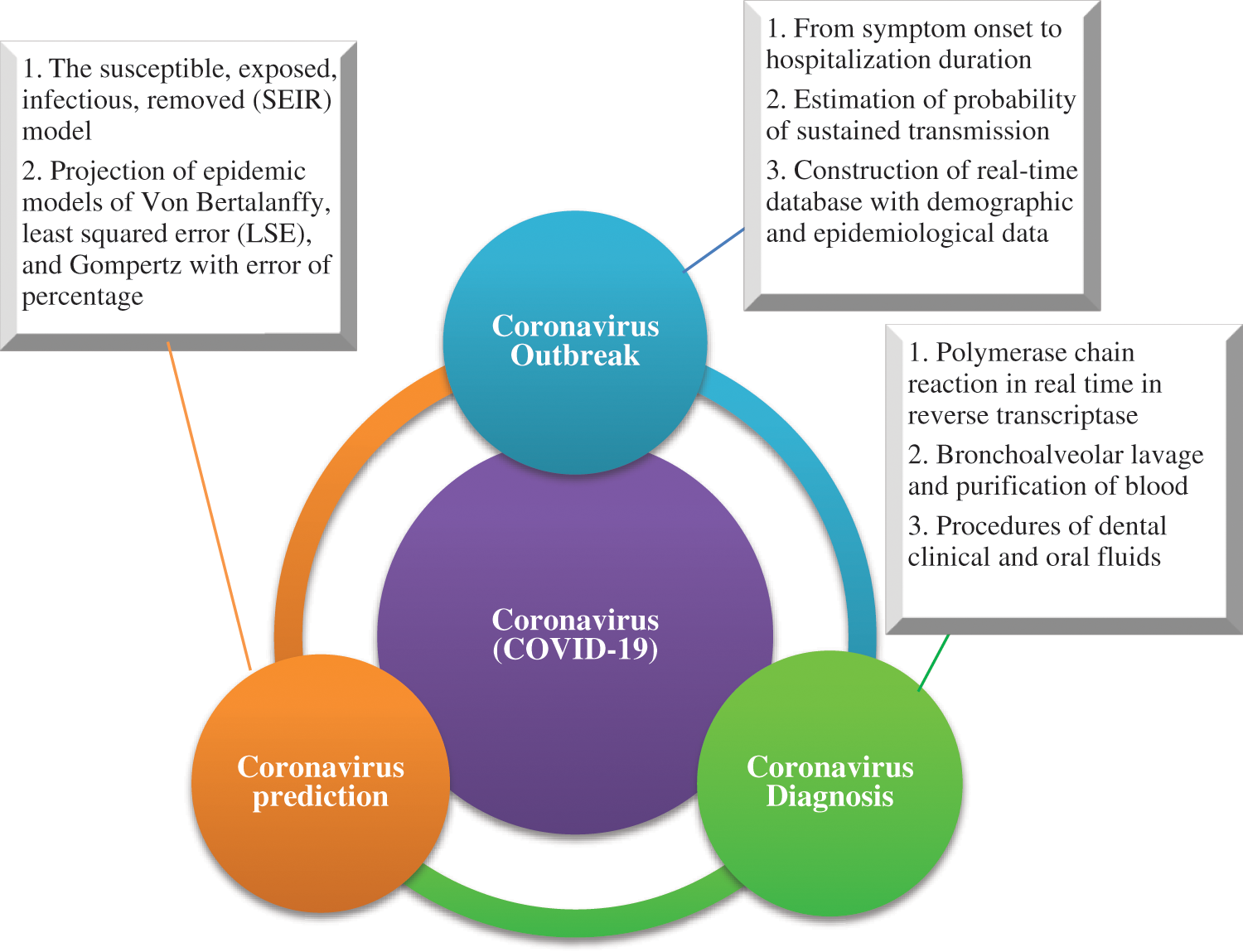

Fig. 6 presents the literature taxonomy of COVID-19. The 3 most significant parts of COVID-19 are the disease outbreak, its diagnosis, and its prediction. Moreover, COVID-19 outbreak literature includes information about how the virus started and how it is spreading globally, along with the reasons for its spread, so that it can be controlled through enforcing regulations. The diagnosis includes information about how the virus can be detected in a human being by examining the symptoms and how long they take to appear so that the severity of the condition can be determined in an infected person. Coronavirus prediction involves studying the virus and previous similar viruses to estimate how it will behave in the future. Various economic, social, and health challenges are faced and will continue to be faced by people worldwide owing to COVID-19.

Figure 6: Literature taxonomy of COVID-19

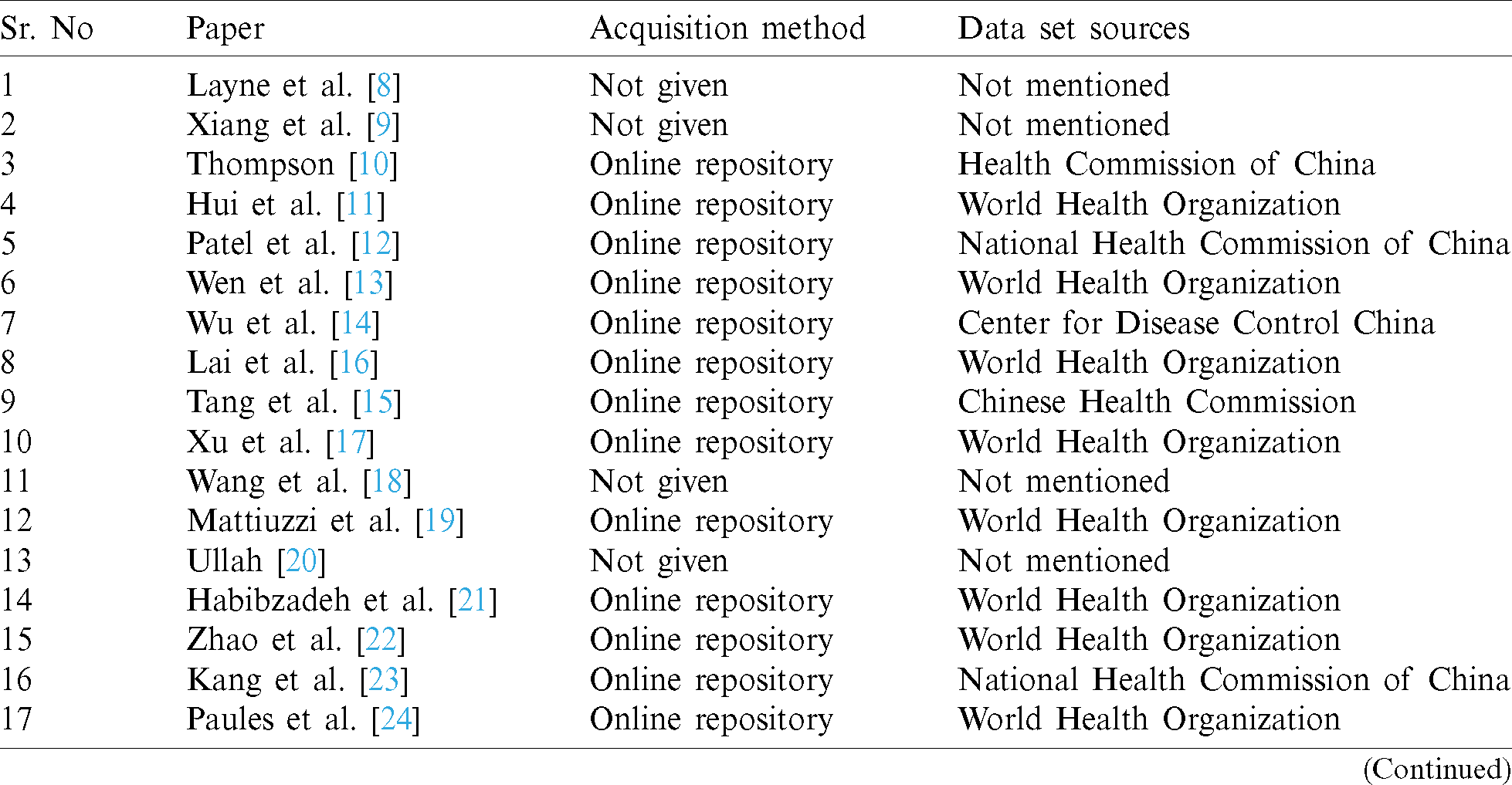

The authors of 26 papers related to the COVID-19 outbreak are listed in Tab. 5 along with the sources of the data set. If no source was provided, the table uses the term not mentioned. The data set was taken from the Chinese Health Commission [15].

Table 5: Dataset sources and their acquisition methods

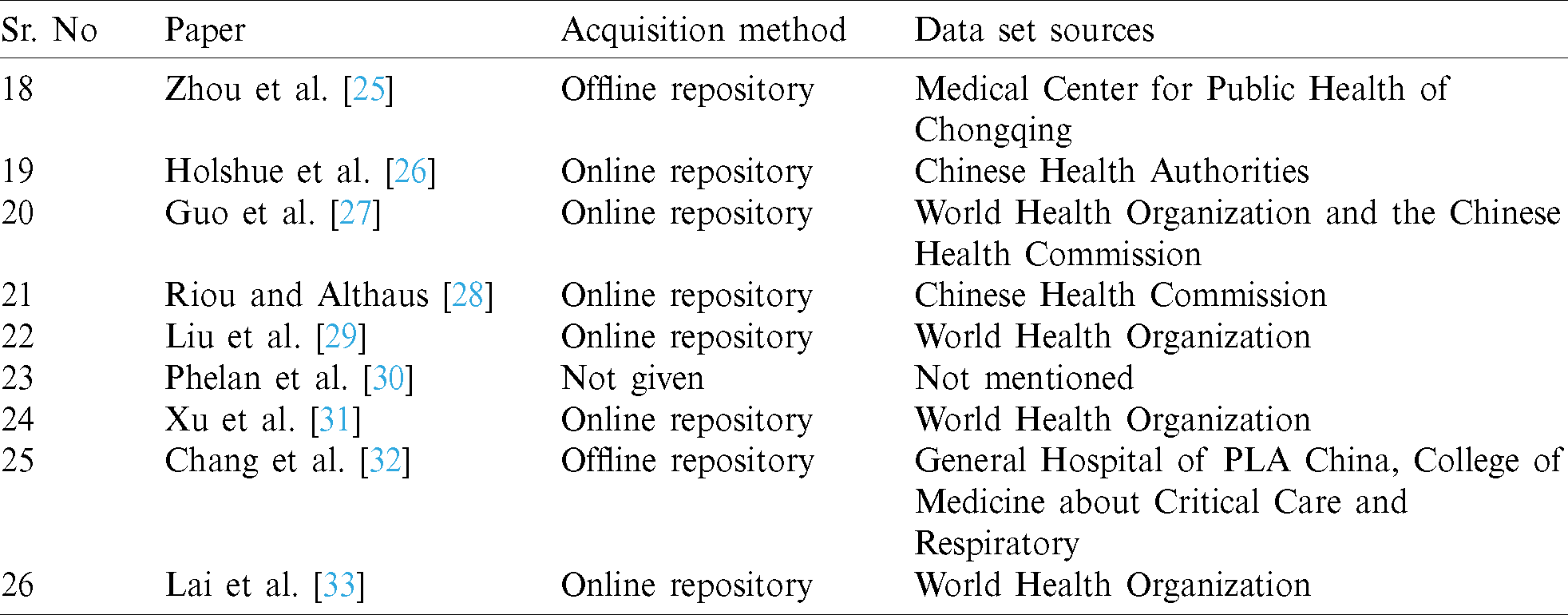

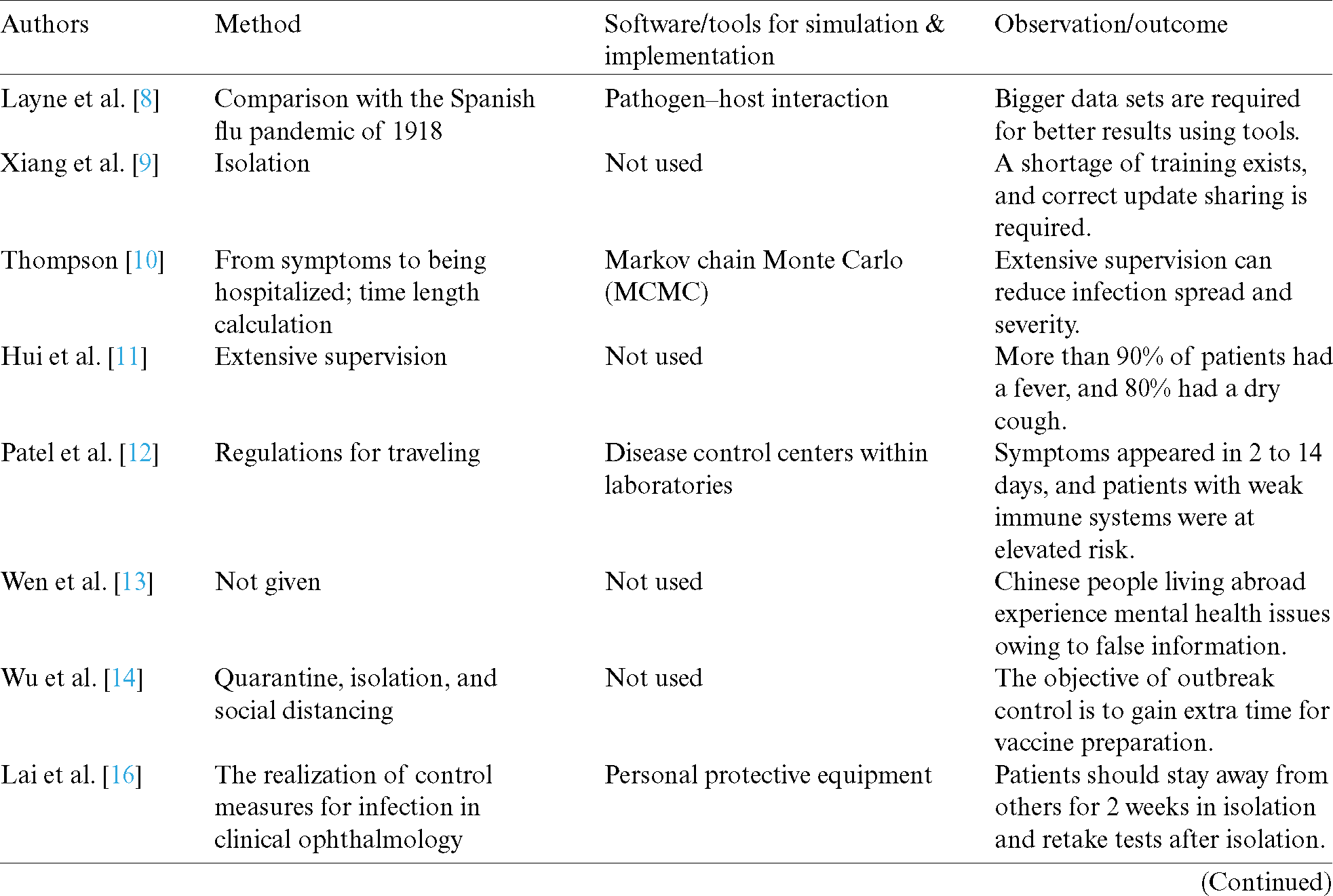

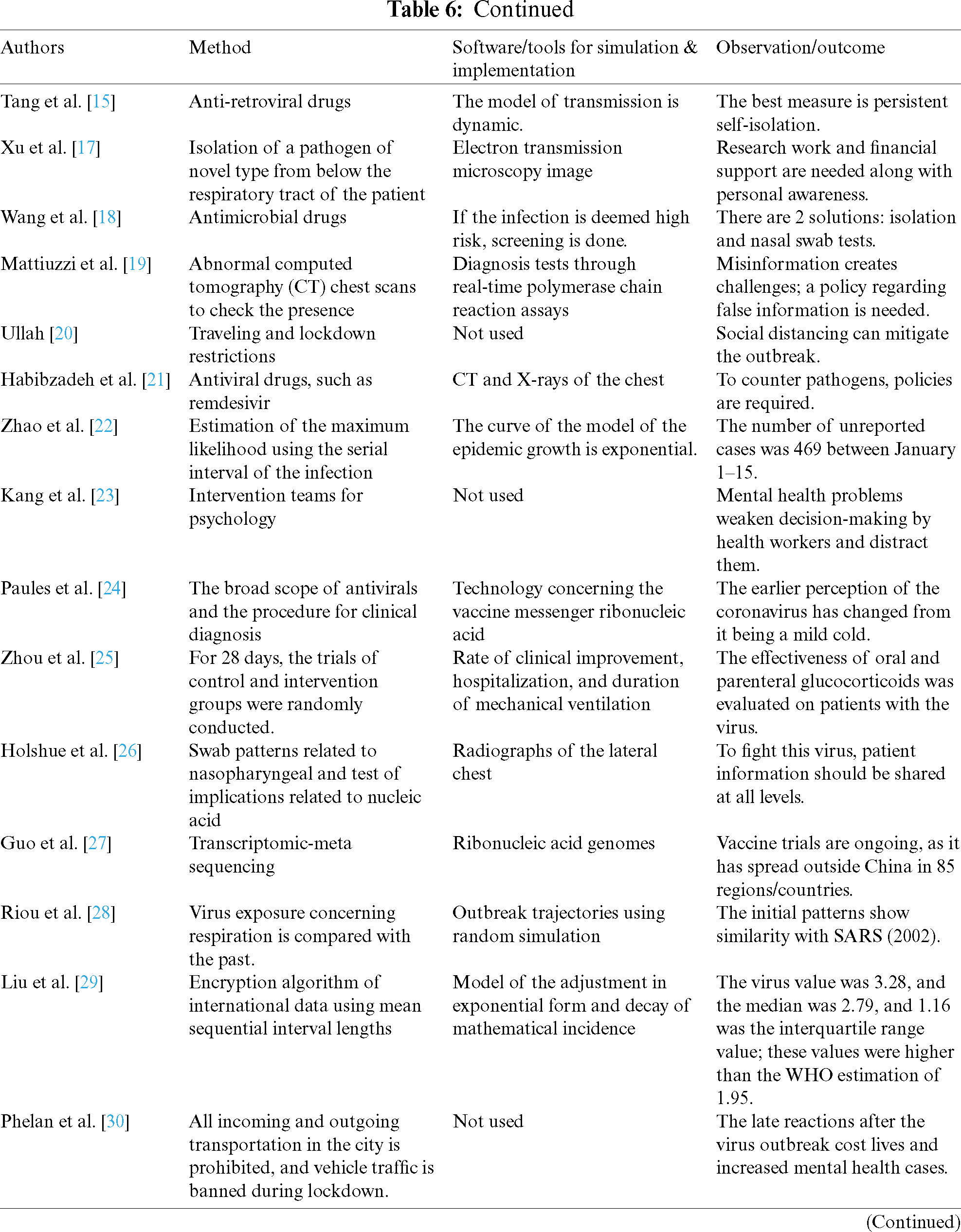

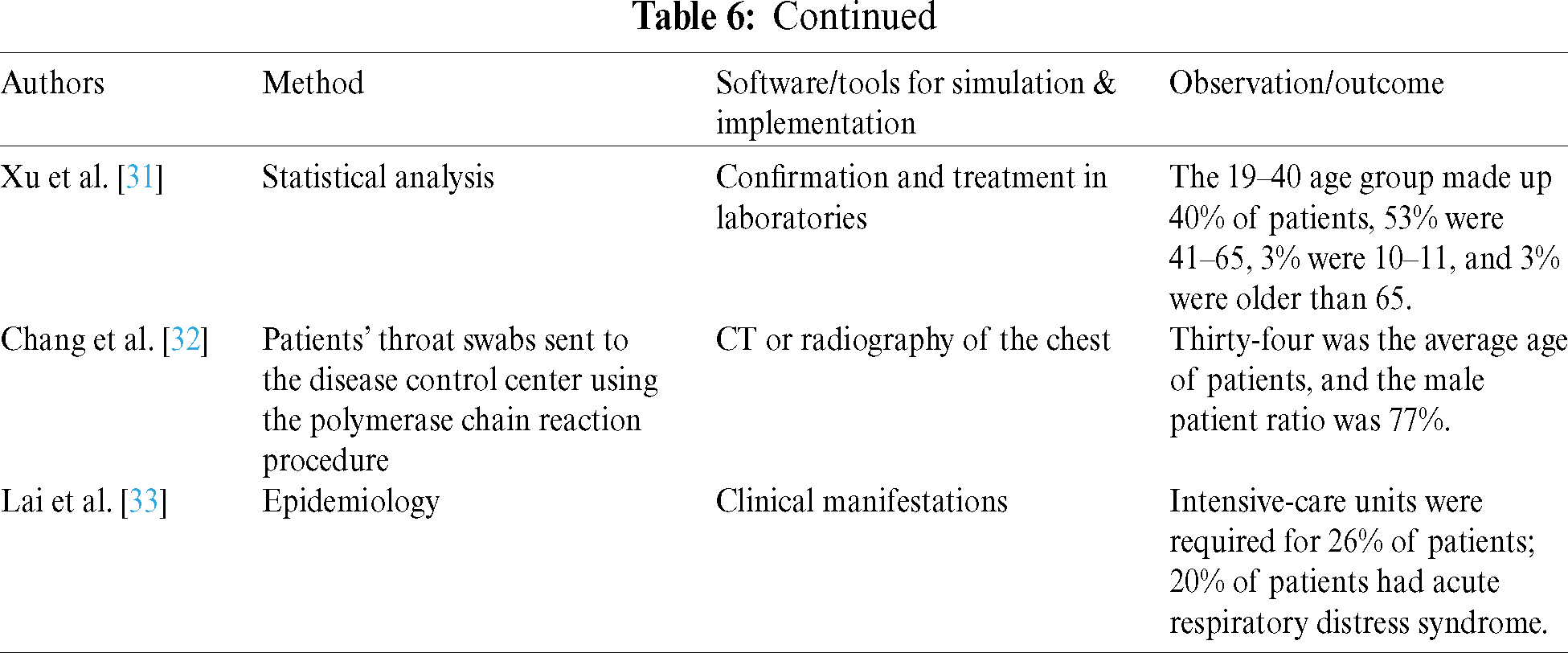

The authors of 26 papers related to the COVID-19 outbreak are presented in Tab. 6 along with methods to control the outbreak and the tools or software used to implement the strategies. The outcomes or observations in the papers are also given [28].

Table 6: Overview of papers related to the COVID-19 outbreak

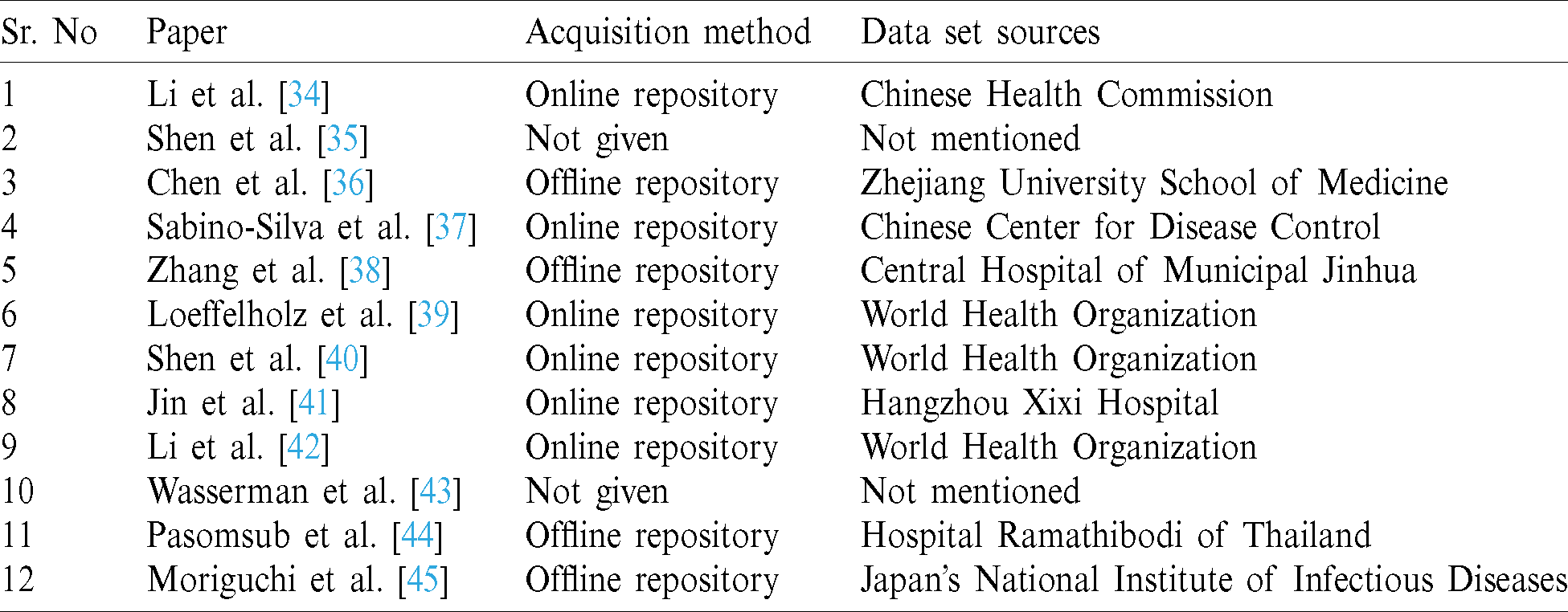

The authors of 12 papers related to COVID-19 diagnosis are presented in Tab. 7 along with the sources of the data set. If no source was given in the paper, the table uses the term not mentioned. The data set was taken from the Chinese Health Commission [34].

Table 7: Dataset sources and acquisition methods

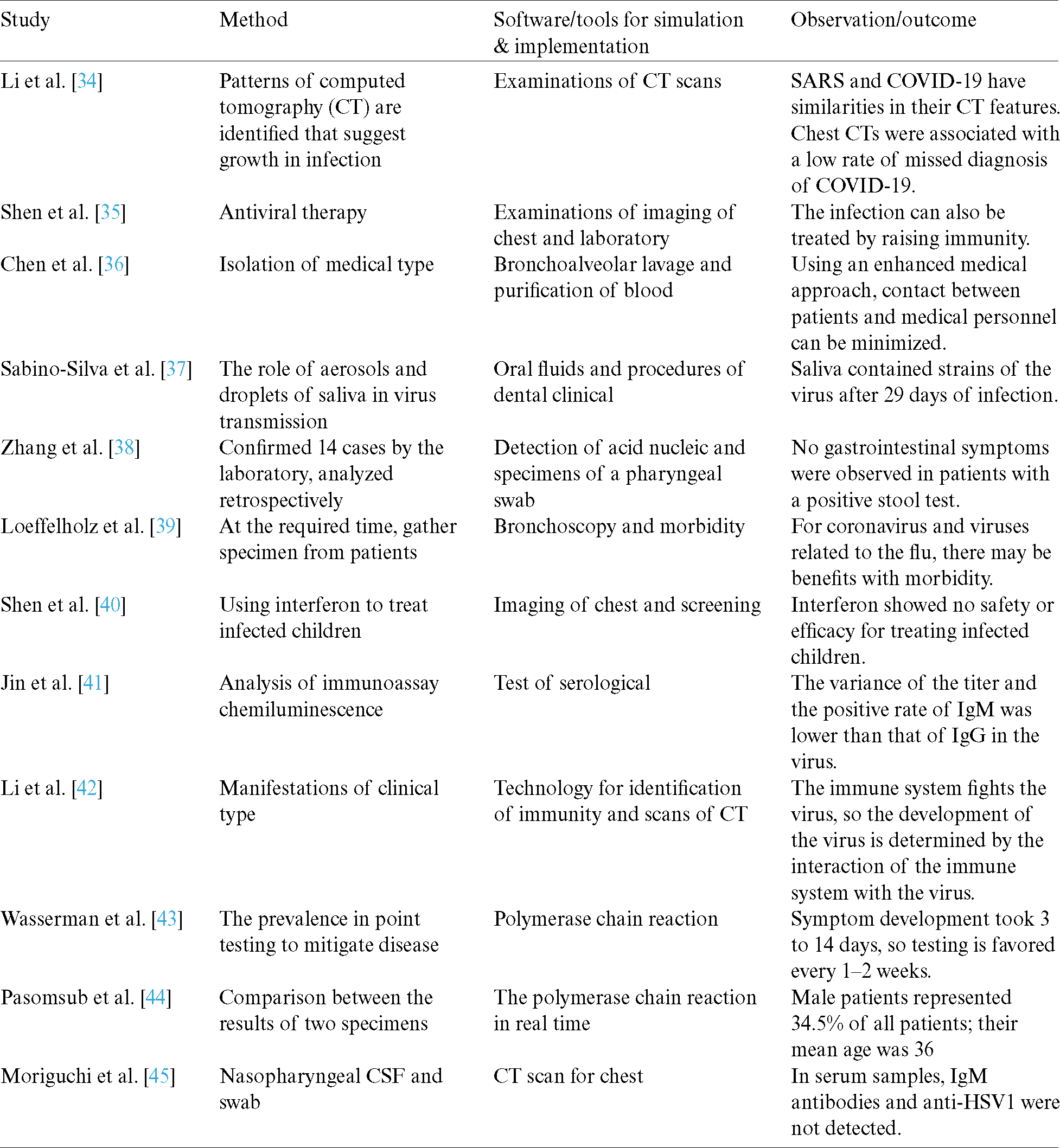

The authors of 12 papers related to COVID-19 diagnosis are presented in Tab. 8 along with methods to control the outbreak of the pandemic and the tools or software used to implement the methods. Further, the outcomes or observations of the papers are provided. The method for comparison between the results of the two specimens is used along with the implementation of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in real-time. As reported, 34.5% of patients were male, and their mean age was 36 [44].

Table 8: Overview of papers related to COVID-19 diagnosis

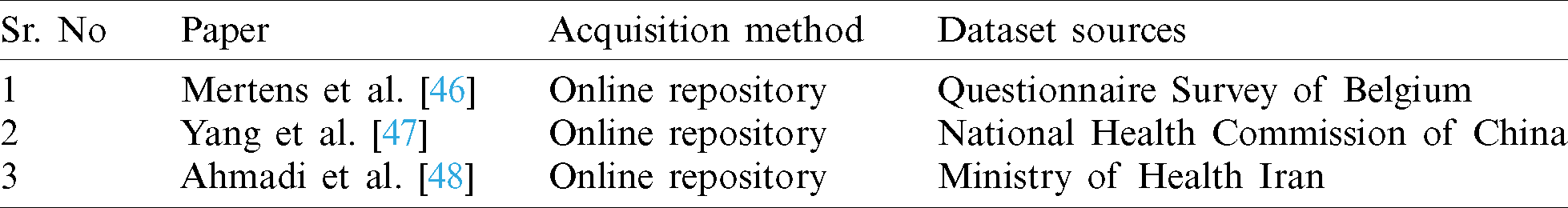

The authors of 3 papers on COVID-19 prediction are presented in Tab. 9 along with the sources of the data set. If no source was given in the specific paper, the table uses the term not mentioned. The data set was taken from a questionnaire survey of Belgium [46].

Table 9: Dataset sources and acquisition methods

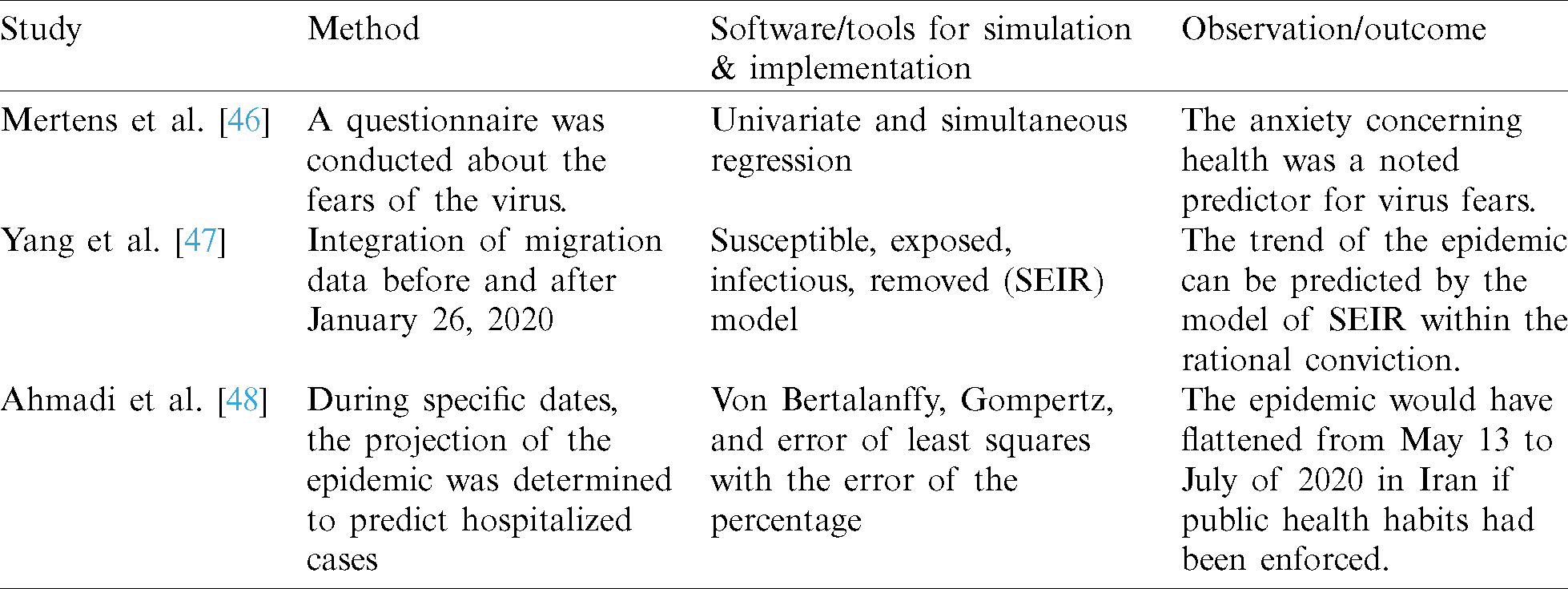

The authors of 3 papers on COVID-19 prediction documents are presented in Tab. 10 along with methods to control the outbreak and the tools or software used to implement strategies. Moreover, the outcomes or observations of the papers are provided. The integration method of the migration data before and after January 26, 2020 was used with the implementation of the susceptible, exposed, infectious, and removed (SEIR) model because it reports that the trend can be predicted using the SEIR model with rational conviction [47].

Table 10: Overview of papers related to COVID-19 prediction

COVID-19 has proved to be a deadly infection that has not only cost lives, but also damaged the economy by forcing businesses into bankruptcy. This has resulted in millions of people becoming unemployed. Mental health cases have also risen, causing an increase in suicides. Countries have taken out loans, and the International Monetary Fund has delayed payments of installments to allocate most of the resources for the fight against the pandemic. To date, vaccines have been developed and are in use in certain countries, but following standard operating procedures remain critical. The countries following the guidelines can eradicate this virus. New Zealand was the first country to eliminate the virus from their territory. The predictions regarding the virus are that it can take up to or more than one year to eradicate it from the world. On the positive side, during this pandemic, several countries have sent medical professionals and equipment to those who are in need. If the world comes together as community, it can fight this deadly virus.

Acknowledgement: We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: Authors received no specific funding for the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. . https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses. [Google Scholar]

2. . https://who.sprinklr.com/. [Google Scholar]

3. . https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-05/here-s-all-the-cash-asian-nations-have-pledged-for-virus-relief. [Google Scholar]

4. . https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/stocks. [Google Scholar]

5. . https://www.bloomberg.com/markets/commodities. [Google Scholar]

6. . https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. . https://data.oecd.org/gdp/real-gdp-forecast.htm. [Google Scholar]

8. S. P. Layne, J. M. Hyman, D. M. Morens and J. K. Taubenberger. (2020). “New coronavirus outbreak: Framing questions for pandemic prevention,” Science Translation Medicine, vol. 12, no. 534, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

9. Y. T. Xiang, Y. Yang, W. Li, L. Zhang, Q. Zhang et al. (2020). , “Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed,” Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 228–229. [Google Scholar]

10. R. N. Thompson. (2020). “Novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China, 2020: Intense surveillance is vital for preventing sustained transmission in new locations,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 498–504. [Google Scholar]

11. D. S. Hui, I. Azhar, E. Madani, T. A. Ntoumi, F. Kock et al. (2020). , “The continuing 2019-NCOV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health–-the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan,” China International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 91, pp. 264–266. [Google Scholar]

12. A. Patel and D. B. Jernigan. (2019). “Initial public health response and interim clinical guidance for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak-United States,” Journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 889–895. [Google Scholar]

13. J. Wen, J. Aston, X. Liu and T. Ying. (2020). “Effects of misleading media coverage on public health crisis: A case of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China,” An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

14. Z. Wu and J. M. M. Googan. (2020). “Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the chinese center for disease control and prevention,” Journal of American Medical Association, vol. 323, no. 13, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

15. B. Tang, N. L. Bragazzi, Q. Li, S. Tang, Y. Xiao et al. (2020). , “An updated estimation of the risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus,” Infectious Disease Modelling, vol. 5, pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar]

16. T. H. Lai, E. W. Tang, S. K. Chau, K. S. Fung and K. K. Li. (2020). “Stepping up infection control measures in ophthalmology during the novel coronavirus outbreak: An experience from Hong Kong,” Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, vol. 258, no. 3, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

17. J. Xu, Y. Chen, H. Chen and B. Cao. (2020). “Novel coronavirus outbreak: A quiz or final exam?,” Frontiers of Medicine, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 225–228. [Google Scholar]

18. J. Wang, H. Qi, L. Bao, F. Li and Y. Shi. (2020). “A contingency plan for the management of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in neonatal intensive care units,” Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 258–259. [Google Scholar]

19. C. Mattiuzzi and G. Lippi. (2020). “Which lessons shall we learn from the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak?,” Annals of Translational Medicine, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar]

20. E. Ullah. (2020). “The novel coronavirus outbreak: A challenge beyond borders,” Pakistan Journal of Surgery and Medicine, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

21. P. Habibzadeh and E. K. Stoneman. (2020). “The novel coronavirus: A bird’s eye view,” International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

22. S. Zhao, S. S. Musa, Q. Lin, J. Ran, G. Yang et al. (2020). , “Estimating the unreported number of novel coronavirus cases in China in the first half of January 2020: A data–driven modelling analysis of the early outbreak,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 388–396. [Google Scholar]

23. L. Kang, Y. Li, S. Hu, M. Chen, C. Yang et al. (2020). , “The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus,” Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

24. C. I. Paules, H. D. Marston and A. S. Fauci. (2020). “Coronavirus infections–-more than just the common cold,” Journal of American Medical Association, vol. 323, no. 8, pp. 707–708. [Google Scholar]

25. Y. H. Zhou, Y. Y. Qin, Y. Q. Lu, F. Sun, S. Yang et al. (2020). , “Effectiveness of glucocorticoid therapy in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia: Protocol of a randomized controlled trial,” Chinese Medical Journal, vol. 10, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

26. M. L. Holshue, C. D. Bolt, S. Lindquist, K. H. Lofy, J. Wiesman et al. (2020). , “First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 382, no. 10, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

27. Y. R. Guo, Q. D. Cao, Z. S. Hong, Y. Y. Tan, S. D. Chen et al. (2020). , “The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak-an update on the status,” Military Medical Research, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

28. J. Riou and C. L. Althaus, “Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus, December 2019 to January 2020,” Europe’s Journal on Infectious Disease Surveillance, Epidemiology, Prevention and Control, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 2000058–2000067, 2020. [Google Scholar]

29. Y. Liu, A. A. Gayle, A. W. Smith and J. Rocklöv. (2020). “The reproductive number of covid-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus,” Journal of Travel Medicine, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

30. A. L. Phelan, R. Katz and L. O. Gostin. (2020). “The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: Challenges for global health governance,” Journal of American Medical Association, vol. 323, no. 8, pp. 709–710. [Google Scholar]

31. X. W. Xu, X. X. Wu, X. G. Jiang, K. J. Xu, L. J. Ying et al. (2020). , “Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus outside of Wuhan, China: Retrospective case series,” British Medical Journal, vol. 10, pp. 368–378. [Google Scholar]

32. D. Chang, M. Lin, L. Wei, L. Xie, G. Zhu et al. (2020). , “Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China,” Journal of American Medical Association, vol. 323, no. 11, pp. 1092–1093. [Google Scholar]

33. C. C. Lai, T. P. Shih, W. C. Ko, H. J. Tang and P. R. Hsueh. (2020). “Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) and corona virus disease-2019 (COVID-19The epidemic and the challenges,” International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 105924–105938. [Google Scholar]

34. Y. Li and L. Xia. (2020). “Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19Role of chest ct in diagnosis and management,” American Journal of Roentgenology, vol. 214, no. 6, pp. 1280–1286. [Google Scholar]

35. K. Shen, Y. Yang, T. Wang, D. Zhao and Y. Jiang. (2020). “Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children: Experts’ consensus statement,” World Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 7, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

36. Z. M. Chen, J. F. Fu, Q. Shu, Y. H. Chen, C. Z. Hua et al. (2020). , “Diagnosis and treatment recommendations for pediatric respiratory infection caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus,” World Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 7, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

37. R. S. Silva, A. C. G. Jardim and W. L. Siqueira. (2020). “Coronavirus COVID-19 impacts to dentistry and potential salivary diagnosis,” Clinical Oral Investigations, vol. 24, no. 10221, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

38. J. C. Zhang, S. B. Wang and Y. D. Xue. (2020). “Fecal specimen diagnosis 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia,” Journal of Medical Virology, vol. 92, no. 6, pp. 680–682. [Google Scholar]

39. M. J. Loeffelholz and Y. W. Tang. (2020). “Laboratory diagnosis of emerging human coronavirus infections-the state of the art,” Emerging Microbes and Infections, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 747–756. [Google Scholar]

40. K. L. Shen and Y. H. Yang. (2020). “Diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children: A pressing issue,” World Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 7, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

41. Y. Jin, M. Wang, Z. Zuo, C. Fan, F. Ye et al. (2020). , “Diagnostic value and dynamic variance of serum antibody in coronavirus disease 2019,” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 94, pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

42. X. Li, M. Geng, Y. Peng, L. Meng and S. Lu. (2020). “Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19,” Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 102–108. [Google Scholar]

43. M. Wasserman, J. G. Ouslander, A. Lam, A. G. Wolk, J. E. Morley et al. (2020). , “Diagnostic testing for SARS-coronavirus-2 in the nursing facility: Recommendations of a Delphi panel of long-term care clinicians,” Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, vol. 24, no. 20, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

44. E. Pasomsub, S. P. Watcharananan, K. Boonyawat, P. Janchompoo, G. Wongtabtim et al. (2020). , “Saliva sample as a non-invasive specimen for the diagnosis of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19A cross-sectional study,” Clinical Microbiology and Infection, vol. 2020, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

45. T. Moriguchi, N. Harii, J. Goto, D. Harada, H. Sugawara et al. (2020). , “A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2,” International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 94, pp. 55–58. [Google Scholar]

46. G. Mertens, L. Gerritsen, E. Salemink and I. Engelhard. (2020). “Fear of the coronavirus (COVID-19Predictors in an online study conducted in March 2020,” Journal of Anxiety, vol. 20, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

47. Z. Yang, Z. Zeng, K. Wang, S. S. Wong, W. Liang et al. (2020). , “Modified SEIR and AI prediction of the epidemics trend of COVID-19 in China under public health interventions,” Journal of Thoracic Disease, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 165–172. [Google Scholar]

48. A. Ahmadi, Y. Fadai, M. Shirani and F. Rahmani. (2020). “Modeling and forecasting trend of COVID-19 epidemic in Iran until May 13, 2020,” Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 183–195. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |