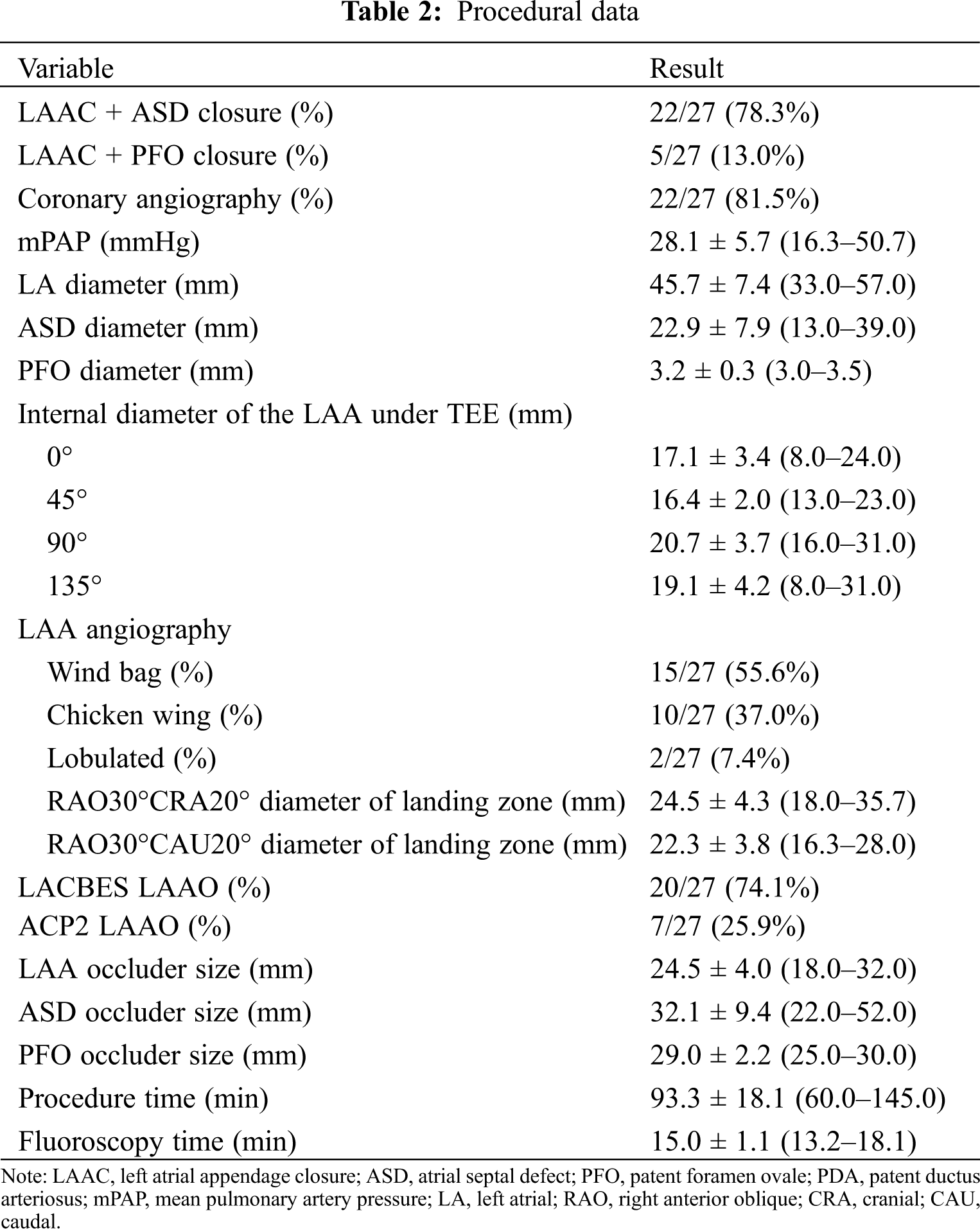

| Congenital Heart Disease |  |

DOI: 10.32604/CHD.2022.017225

ARTICLE

Simultaneous Transcatheter Closure of the Left Atrial Appendage and Congenital Interatrial Communication Closure

Department of Congenital Heart Disease, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China

*Corresponding Authors: Qiguang Wang. Email: wqg1993@163.com; Xianyang Zhu. Email: xyangz2011@163.com

Received: 25 May 2021; Accepted: 12 June 2021

Abstract: Background: Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) with simultaneous interventional occlusion therapy for congenital interatrial communication has become a new focus of patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Little is known about the results of mid-and long-term results. Objective: The aim of this study was to evaluate the mid-and long-term safety and effectiveness of simultaneous transcatheter closure of the left atrial appendage (LAA) and congenital interatrial communication closure in atrial fibrillation (AF) patients. Methods: From Jan 2016 to June 2017, 27 patients with AF were treated with simultaneous transcatheter closure of the LAA and atrial septal defect (ASD, n = 22), patent foramen ovale (PFO, n = 5). Results: The perioperative closure success rate was 96.3%, except for cardiac tamponade occurred in one ASD patient. During the median 37.6-month follow-up period, no cases of cerebrovascular or peripheral vascular embolism, bleeding, infective endocarditis or thrombosis along the occluders were observed. Of the 21 patients with NYHA Class III, nineteen had significant improvements to NYHA Classes I or II, and 81.5% of patients were free from major or minor adverse events during mid-and long-term follow-up. Conclusions: Simultaneous closure of the LAA and congenital interatrial communication closure is a viable option for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who are at risk of stroke or systemic embolism, and it is effective and yields excellent mid-and long-term results.

Keywords: Left atrial appendage; atrial fibrillation; interatrial communication; cardiac catheterization

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is commonly associated with congenital interatrial communication [1]. With the development of interventional and surgical techniques, different therapeutic strategies have been applied for the simultaneous treatment of congenital interatrial communication and atrial fibrillation [2,3]. In the past, most of the patients with ASD/PFOs and atrial fibrillation were only treated for cardiovascular defects. However, ASD/PFOs patients with atrial fibrillation need to take anticoagulants for life. The use of antiarrhythmic drugs and oral anticoagulants has a low control rate and a high risk of bleeding [4]. Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) with simultaneous interventional occlusion therapy for ASD/PFOs has become a new focus of patient care [5,6]. In this study, the mid-and long-term follow-up of the feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of simultaneous percutaneous left atrial appendage closure (PLAAC) and closure device for patients with congenital interatrial communication and atrial fibrillation investigated.

There were 29 patients enrolled in this retrospective study. The clinical criteria for the patients undergoing percutaneous left atrial appendage closure were as follows: (1) persistent atrial fibrillation; (2) age ≥ 18 years old; (3) CHA2DS2VASc score ≥ 2; (4) HAS-BLED score > 3; (5) endured long-term administration of clopidogrel and aspirin; (6) contraindication or intolerance to the administration of warfarin; (7) candidate for transcatheter closure for congenital interatrial communication.

Before the intervention, each patient provided written informed consent. The ethics committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Area Command approved this study, and it was conducted in accordance with all relevant Chinese laws.

Philips iE 3 Ultrasound Diagnostic Instrument, X7-2t Transesophageal Ultrasound Probe (Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands) were used. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was performed in 29 patients 1 week before the operation. The morphology of the left atrial appendage was observed at 0°, 45°, 90° and 135°. The exclusion criteria for TEE examination were as follows: (1) left atrium or other intracardiac wall-attached thromboses; (2) the diameter of the opening was greater than the maximum available depth of the left atrial appendage; (3) the left ventricular function was significantly reduced; (4) the atrial septum was significantly abnormal, there were valve lesions of more than a moderate degree, or other complex congenital heart diseases. PLAAC was placed under the TEE guidance. According to the exclusion criteria, 2 patients were excluded because of left atrial appendage thrombosis and poor cardiac function, respectively.

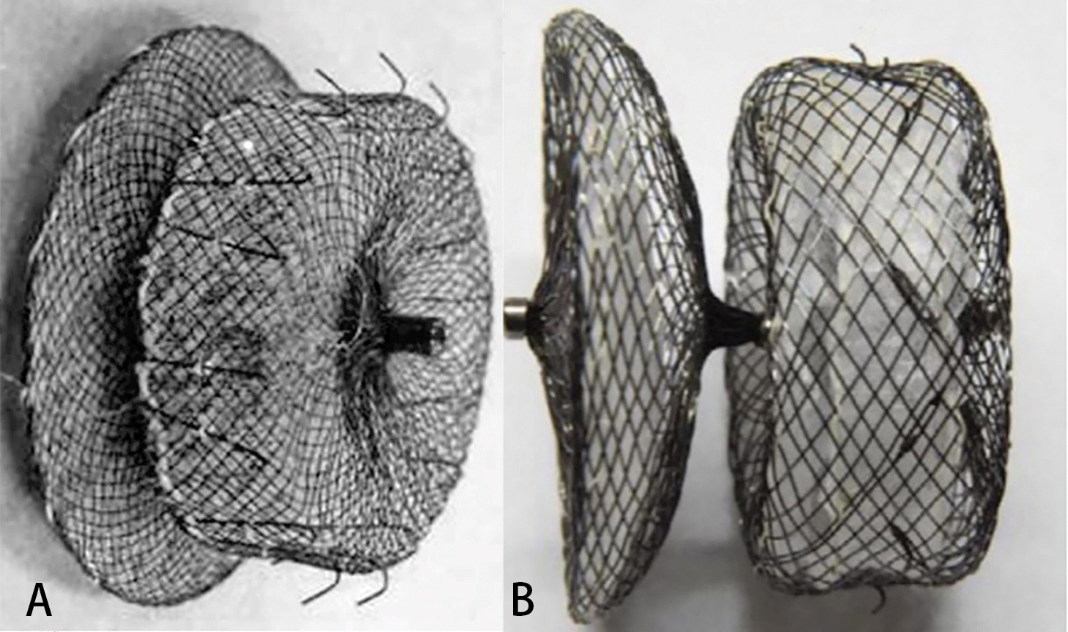

The ACP2 left atrial appendage occluder (Fig. 1A) is the second generation of Amplatzer Cardiac Plug occluder (Abbott, Minneapolis, MS, USA) [7]. The framework is made of self-expanding nickel-titanium alloy wire. The distal columnar structure designed with barbs, and the proximal disc is connected by the central waist. Compared with the first generation, the ACP2 occluder has a wider distal column, longer waist and the disk diameter of the occluder increased with waist diameter from 18 to 32 mm.

The LACBES occluder (Fig. 1B) is a novel LAA occluder that has just been approved for clinical application in China (LACBES®, Push Medical, Shanghai, China) [8]. This occluder is made with nitinol wire mesh and mainly consists of 2 parts, an anchor cylinder, and a sealing disc, which are filled with a polyester fiber membrane. The anchor cylinder ends at the landing zone and deeply anchors to the LAA as a supporting structure for the whole occluder, with the sealing disc sealing the LAA orifice. The sealing disc is curved inward and is 6 mm larger than the anchor cylinder in diameter. The device is available with anchor cylinder sizes from 16 to 34 mm (2-mm size increments) and requires 9- to 14-French sheaths.

Figure 1: LAA occluders. (A) The ACP2 left atrial appendage occluder; (B) The LACBES left atrial appendage occluder

The procedure was performed under general anesthesia. Patients who were aged 50 years or older underwent routine coronary angiography. The pressure of the pulmonary artery and right ventricle was measured through the femoral vein by an end-hole catheter. Thereafter, a 0.035 inch × 260 cm stiff guidewire was inserted through the atrial septal communication (ASD or PFO). Along the guidewire, the delivery sheath (Push Medical, Shanghai, China) was transferred into the left atrium, and then the 6F pigtail catheter was sent into the sheath, landing in the LAA. LAA angiography was performed under the right anterior oblique 30°+ head 20° and the right anterior oblique 30° and the foot 20°. The contrast was injected through the sheath to depict the anatomy and the size of the LAA. The ACP2 or LACBES occluder was deployed, and a stable position was confirmed angiographically and by a tug test. Then, the device was released, and the sheath was slightly retracted but was kept in the left atrium—A properly sized Amplatzer PFO (St. Jude Medical, Plymouth, MN) or ASD (SHSMA, Lepu Medical, Beijing, China) occluder was introduced and deployed to the PFO or ASD using the delivery sheath. The sizing of the PFO and ASD occluder was chosen based on TEE assessment. After confirming a safe position of the septal occluder by contrast injections and a wiggle test, the occluder was released.

2.4 Peri-Procedure Management and Follow-Up

Intravenous injection of heparin was used to maintain an active coagulation time (ACT) of 250–300 s, 1.5 g/12 h of the antibiotic cefuroxime sodium was used as an intravenous prophylactic during the operation and on the first day after the operation, and 3–5 mg/kg oral aspirin combined with 75 mg/day clopidogrel were used after the operation for 6 months. The aspirin and clopidogrel dosages were adjusted according to age and weight.

Procedural success was defined as properly seated devices in the LAA and the PFO or ASD using TEE or TTE per-procedure. Patients were discharged on the third postoperative day. A 30-d, 90-d postprocedural transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and 180-d TEE were performed to confirm proper seating of the devices and to look for thrombi or residual leaks. Residual leaks were classified according to a flow jet >3 mm at the time of postprocedural TTE or TEE. At the same time, a neurology consultation was performed to document potential new cerebrovascular events. Long-term follow-up was performed by telephone interview and review of patient charts in case of an event.

The endpoints were severe complications in the peri-procedural period and major adverse events during the whole follow-up period. Severe adverse events were defined as deaths, stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), other embolism events, device thrombosis or dislocation, major bleeding requiring invasive treatment or blood transfusion and cardiovascular surgery to avoid permanent defects in the body structure or function.

Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Discrete variables are expressed as frequencies or percentages. Those were compared using the unpaired t-test. The statistical software SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for data analysis. A probability of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

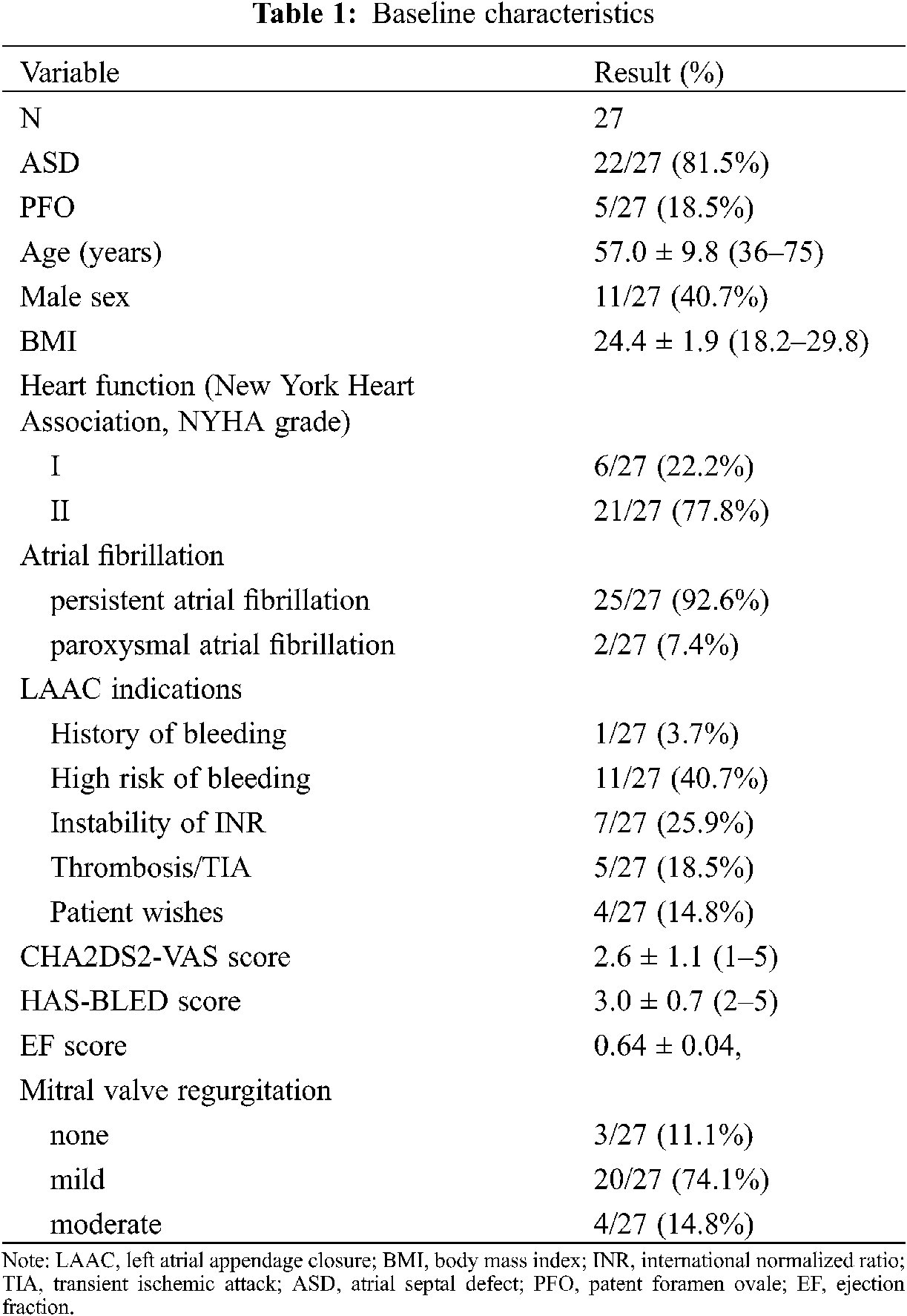

From January 2016 to June 2017, including 11 male and 16 female adult patients ranging from 36 to 75 years of age with congenital interatrial communication and atrial fibrillation underwent simultaneous transcatheter left atrial appendage and interatrial communication closure (Table 1). The average body mass index (BMI) was 24.49 ± 2.47. Simultaneous transcatheter LAA and congenital defect closures were performed in 27 patients who had interatrial communication and persistent AF: 22 ASDs and 5 PFOs. The mean CHA2DS2VASc score was 2.6 ± 1.1, and the HAS-BLED score was 3.0 ± 0.7.

The observed cardiovascular comorbidities were arterial hypertension in 9 patients (33.3%), diabetes mellitus in 3 (11.1%), hyperlipidemia in 7 (25.9%), and a history of prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) in 5 (18.5%).

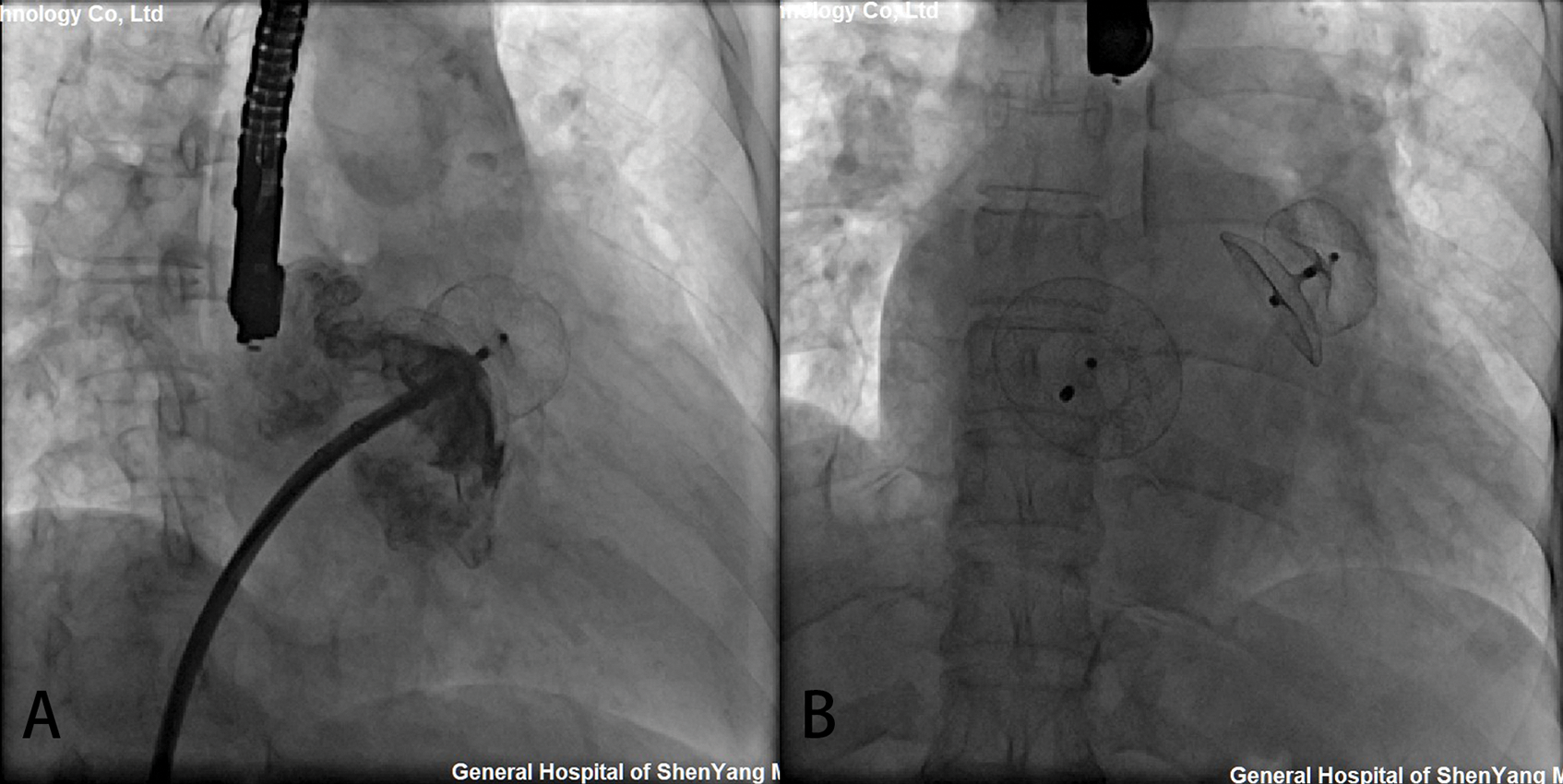

Simultaneous LAA and congenital defect devices were successfully implanted in all the patients (Table 2). The compression rate of the LAA occluder was 4.5%–19.3%. LAAC using 7 ACP2 left atrial appendage occluders and 20 LACBES occluders were successfully performed through the interatrial communication, followed by simultaneously transcatheter interatrial communication closure (Fig. 2). LAAC was successfully performed in 25 patients after only one attempt except for two attempts in two cases using LACBES occluders; after release in the landing area, the LAA occluder was slightly pulled and displaced. The occluder was successfully retreated. After changing the proper size of the LAA occluder, the occluder was stable without displacement. No complications, such as pericardial bleeding, were found after the repeat operation. In one case, a 46 mm domestic ASD occluder with a 1 cm hole was manually implanted after PLAAC as high mean pulmonary artery pressure. Another 26 ASD/PFO patients experienced successful closure of interatrial communication after PLAAC. There was no significant difference in fluoroscopy time between the ACP2 or LACBES occluders groups (15.2 ± 0.1 vs. 15.0 ± 1.2 min, P = 0.749). Of the 23 patients who underwent coronary angiography, 20 patients had normal results except for coronary artery disease in 3 patients, and no further intervention was required.

Figure 2: Simultaneous transcatheter LAA and CHD closures. (A) The delivery sheaths were successfully transported to the LAA via atrial septal communication. After LAAC, the position and residual shunting of the LAA occluder was evaluated by contrast medium and TEE; (B) The shape and position of the occluders were observed by fluoroscopy after simultaneous LAAC and ASD occlusion

The perioperative successful rate of simultaneous PLAAC and congenital defect closure device was 96.3%. One patient developed cardiac tamponade 30 hours after closure. A large amount of pericardial effusion was found by TTE. Pericardiocentesis was performed to drain the effusion. On a postoperative day 5, open-heart surgery was performed for ongoing bleeding. Both LAA and ASD occluders were removed, and ASD was repaired. The ruptured left atrium and the left upper pulmonary vein were repaired. This patient was discharged on the ninth day after surgery. The remaining 26 patients had no residual shunting. Minor adverse events included fever in 2 patients and palpitation in 1 patient, and all these patients recovered with symptomatic treatment. No complications, such as pneumoembolism, pericardial effusion, thrombosis, or hemorrhage, occurred.

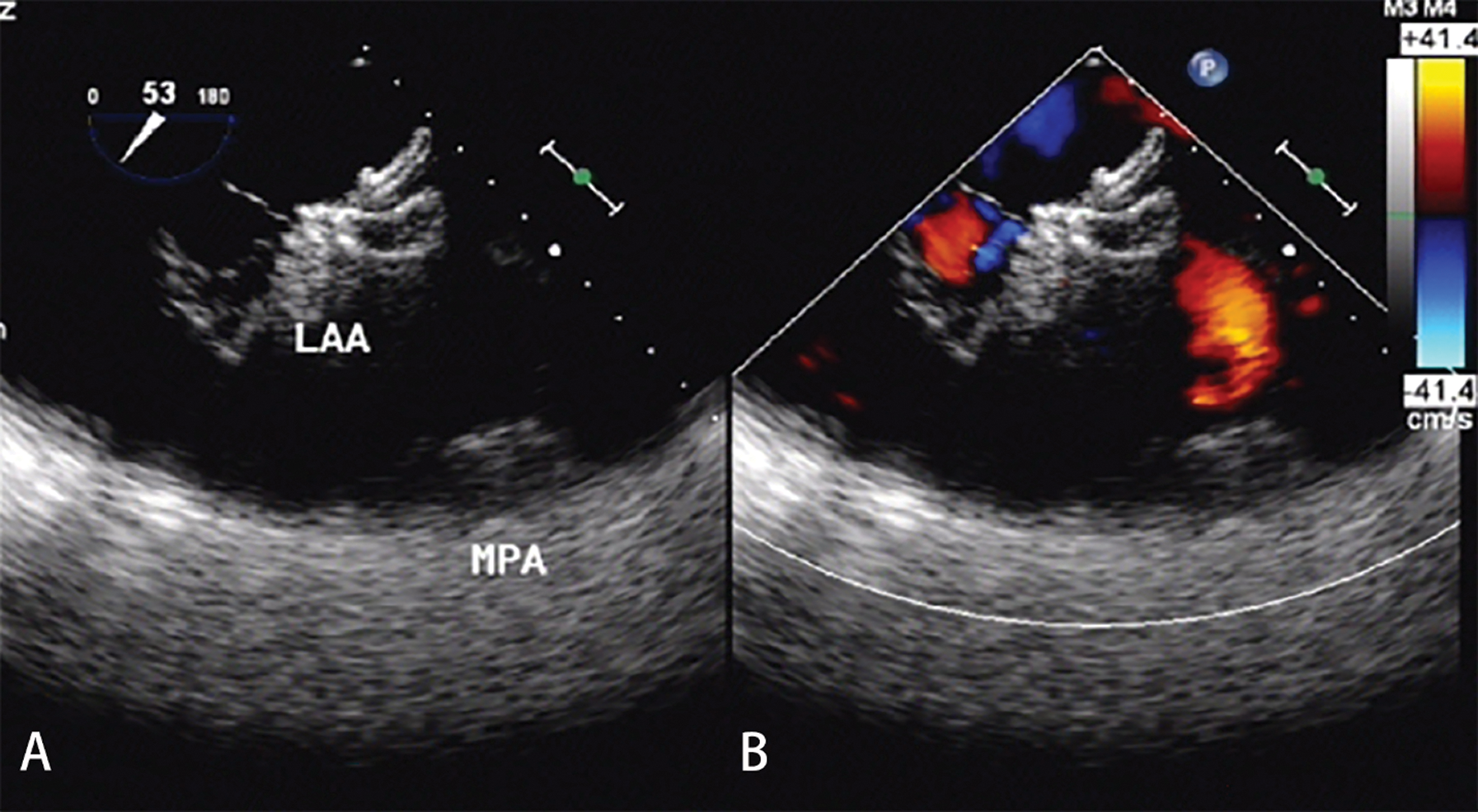

Clinical follow-up was completed at a median follow-up time of 37.6 months. No device-related deaths were observed during the whole follow-up period. No new-onset mitral valve regurgitation more severe than moderate degree was noted. One patient complained of palpitation 34 days after the procedure at a clinic visit and recovered from symptomatic treatment. Neither cerebrovascular/peripheral vascular embolic events nor hemorrhage occurred during a mean follow-up of 38.4 ± 3.9 months. Twenty-six patients (96.3%) completed 30 days and 90 days of follow-up by TTE and 180 days of follow-up by TEE. The results demonstrated the proper positioning of both devices in all patients. There was no thrombosis or residual leakage into the LAA occluders (Fig. 3). There were no significant changes in ejection fraction score after closure (F = 0.82, P = 0.52). Of the 21 patients with NYHA Class III, 19 had significant improvements to NYHA Classes I or II. One ASD patient was re-hospitalized for deterioration of heart failure 140 days after closure. The other high mean pulmonary artery pressure patient with hole ASD occluder had no significant improvement in cardiac function at follow-up every year. No infective endocarditis was observed during the follow-up period. 81.5% of patients were free from major or minor adverse events during mid-and long-term follow-up.

Figure 3: TEE examination after 180 days of follow-up. (A) There was no thrombosis with good shape and a fixed position of the LAA occluder. (B) There was no residual leakage into the LAA occluder

Previous studies have shown that AF is the most common complication of congenital interatrial communication, especially in elderly patients with atrial septal defects [9,10]. Long-term volume overload due to atrial septal defects can lead to atrial enlargement, an increased pressure and stretching force of the atrial wall, interstitial fibrosis of the atrial wall, and reconstruction of the atrial anatomy, which leads to the occurrence of atrial electrical anatomical reconstruction and AF [11,12]. The annual incidence rate of thromboembolic stroke is approximately 1.9%–18.2%, which is 5.6 times that of normal people. The hemodynamic status of AF and extensive trabecular structure in LAA are important factors for thrombosis [13]. In our study, all patients did not tolerate warfarin or new anticoagulant therapy. For patients with congenital interatrial communication who are not suited for oral anticoagulants, LAA occlusion is an alternative to prevent stroke.

Atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) is often associated with interatrial communication, which increases the risk of thromboembolism. ASA combined with ASD is relatively rare, and the proportion of PFO can be as high as 60%. Patients with PFO seldom had atrial fibrillation in the early stage because the hemodynamic changes are not obvious. The study showed that the positive rate of PFO in patients with atrial fibrillation detected by transesophageal echocardiography was 18.7%, while the positive rate of PFO confirmed by catheter pulmonary vein isolation was 57.3% [14]. It is speculated that the positive rate of PFO in patients with atrial fibrillation may be underestimated. Therefore, simultaneous closure of the LAA and PFO will minimize the risk of thromboembolism.

Simultaneous transcatheter LAA and congenital interatrial communication closure are rarely reported in the literature. Versaci et al. [15] reported one PFO patient with AF who had a history of transient ischemia and could not tolerate anticoagulant drugs. LAAC and PFO occlusion was performed simultaneously, suggesting this approach was safe and feasible. Koermendy et al. [16] reviewed 51 PFO patients with AF who underwent simultaneous transcatheter LAA and PFO closure via interatrial communication. The technical success rate was high, and complications related to atrial septal puncture could be effectively avoided. Gafoor et al. [17] reviewed the clinical experience of simultaneous LAA occlusion in ASD/PFO patients with AF. No serious complications were found except for one case of puncture site bleeding. Yu et al. [18] found that the proportion of male patients and the incidence of preoperative embolization in the group first receiving LAAC followed by ASD/PFO occlusion were higher than those in the group with single LAAC. In this study, 27 patients with ASD/PFO who were suitable for transcatheter interatrial communication closure by preoperative evaluation successfully underwent transcatheter closure of the LAA through interatrial communication. The results support the feasibility of this approach. The results of a study on LAAC utilizing existing interatrial communication showed good safety and long-term success. Simultaneous transcatheter interatrial communication closure achieved additional benefits without increasing the risks. Compared with patients who underwent trans-atrial septal puncture, the patients who utilized interatrial communication had shorter operation times and effectively avoided potential complications [19]. It is important to note that the delivery sheath might be difficult to anchor, resulting in potential repeated operations for large ASDs.

The major procedural complications include pericardial tamponade, device embolization, major bleeding, stroke, transient ischemic attack, cardiac dysfunction, etc., in which pericardial tamponade is most frequent. In this study, 1 case of serious adverse events occurred, including 1 patient who suffered from pericardial tamponade due to LA and left superior pulmonary vein rupture. Likely the abrasion effect of the upper left sealing disc of the LAA occluder against the LAA root might lead to delayed cardiac tamponade. We do not have other patients developing pericardial effusion. Koermendy et al. [16] reported two pericardial tamponade cases for several unsuccessful attempts with different sizes of LAA occluders and recrossing interatrial communication with the delivery sheath, which resulted in atrial wall injury. However, in our study, the patient was found to have delayed cardiac tamponade 30 h after the procedure, likely caused by the abrasive effect of LAA occluder disks. ASDs are associated with a high incidence of AF, and they likely lead to a large fibrotic fragile left atrium with characteristic abnormal hemodynamic changes, which further increases the potential damage to the left atrium or LAA wall caused by the direct incision effect from the rim of the disc of the LAA occluder. Some adverse events were related to the deterioration of cardiac function caused by long-term hemodynamic abnormalities from interatrial communication. Therefore, the change in cardiac function in patients with congenital interatrial communication might require careful preoperative management.

The new domestic LAA occluder used in this study has a similar 2-disc appearance to the ACP2 occluder, which has been utilized in the clinic. However, the anchor cylinder and sealing disc of the LACBES occluder are designed and made independently, and they have different nitinol wire hardnesses. Micro-barbs in the anchor cylinder are sculpturally integrated, which renders the occluder retrieved and redeployed completely and repeatedly without influencing its structure. In this study, two LACBES LAA occluders could be completely retrieved in the delivery sheath and then repositioned and rereleased, which facilitated the LAAC procedure. No thrombosis was found by TTE or TEE during the mid-and long-term follow-up, which showed that anti-thrombus treatment with aspirin and/or clopidogrel could prevent thrombosis after LAAC.

Although simultaneous transcatheter LAA and congenital interatrial communication closure treatment was safe, the current clinical reports are limited and lack large clinical research data support. However, in view of the high incidence of atrial fibrillation in congenital interatrial communication patients, even after interatrial communication occlusion, there is still a high incidence of atrial fibrillation, which requires anticoagulation treatment for life. Simultaneous transcatheter LAA and congenital interatrial communication closure treatment can not only avoid the difficulty of LAAC in the future but also minimize the risk of stroke and bleeding after interatrial communication occlusion, so the patients can benefit for life.

The present study had several limitations. First and foremost, as was the case during our previous study, and in accordance with a consensus reached by Chinese experts, we followed the strict LAAC inclusion/exclusion criteria. Second, because this was a retrospective study, we evaluated only the results of ASD/PFO in AF adult patients. Third, occluder selection depended on the experience of the operators, and we lacked a controlled cohort study design with large sample sizes for testing several types of LAA occluders. Fourth, patients were enrolled from only our center and therefore may not be representative of the general population. Finally, the number of patients included in the study was relatively small, and a prolonged follow-up period was not adopted for all patients.

Simultaneous closure of LAA and congenital interatrial communication closure is a viable option for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who are at risk of stroke. This approach is effective and yields excellent mid-and long-term results.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870367) and Doctoral Start-up Foundation of Liaoning Province of China (2019-BS-266).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1. Kirsh, J. A., Walsh, E. P., Triedman, J. K. (2002). Prevalence of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation and intra-atrial reentrant tachycardia among patients with congenital heart disease. American Journal of Cardiology, 90(3), 338–340. [Google Scholar]

2. Kamioka, M., Yoshihisa, A., Hijioka, N., Nodera, M., Yamada, S. et al. (2019). The efficacy of combination of transcatheter atrial septal defects closure and radiofrequency catheter ablation for the prevention of atrial fibrillation recurrence through bi-atrial reverse remodeling. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology, 59(2), 365–372. [Google Scholar]

3. Nakagawa, K., Akagi, T., Nagase, S., Takaya, Y., Kijima, Y. et al. (2019). Efficacy of catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with atrial septal defect: A comparison with transcatheter closure alone. European Journal of Pacing, Arrhythmias and Cardiac Electrophysiology, 21(11), 1663–1669. [Google Scholar]

4. Khairy, P., van Hare, G. F., Balaji, S., Berul, C. I., Cecchin, F. et al. (2014). PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the recognition and management of arrhythmias in adult congenital heart disease: Developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology (ACCthe American Heart Association (AHAthe European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRAthe Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRSand the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ISACHD). Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 30(10), e1–e63. [Google Scholar]

5. Reddy, V. Y., Doshi, S. K., Sievert, H., Buchbinder, M., Neuzil, P. et al. (2013). Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure for stroke prophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation: 2.3-year follow-up of the PROTECT AF (Watchman left atrial appendage system for embolic protection in patients with atrial fibrillation) Trial. Circulation, 127(6), 720–729. [Google Scholar]

6. Holmes, D. R. Jr., Kar, S., Price, M. J., Whisenant, B., Sievert, H. et al. (2014). Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman left atrial appendage closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: The PREVAIL trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 64(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

7. Freixa, X., Chan, J. L., Tzikas, A., Garceau, P., Basmadjian, A. et al. (2013). The Amplatzer Cardiac Plug 2 for left atrial appendage occlusion: Novel features and first-in-man experience. EuroIntervention, 8(9), 1094–1098. [Google Scholar]

8. Tang, X., Zhang, Z., Wang, F., Bai, Y., Xu, X. et al. (2017). Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure with LACBES((R)) occluder—A preclinical feasibility study. Circulation Journal, 82(1), 87–92. [Google Scholar]

9. Tutarel, O., Kempny, A., Alonso-Gonzalez, R., Jabbour, R., Li, W. et al. (2014). Congenital heart disease beyond the age of 60: Emergence of a new population with high resource utilization, high morbidity, and high mortality. European Heart Journal, 35(11), 725–732. [Google Scholar]

10. Oster, M., Bhatt, A. B., Zaragoza-Macias, E., Dendukuri, N., Marelli, A. (2019). Interventional therapy versus medical therapy for secundum atrial septal defect: A systematic review (Part 2) for the 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 73(12), 1579–1595. [Google Scholar]

11. Udholm, S., Nyboe, C., Redington, A., Nielsen-Kudsk, J. E., Nielsen, J. C. et al. (2019). Hidden burden of arrhythmias in patients with small atrial septal defects: A nationwide study. Open Heart, 6(1), e001056. [Google Scholar]

12. Vitarelli, A., Mangieri, E., Gaudio, C., Tanzilli, G., Miraldi, F. et al. (2018). Right atrial function by speckle tracking echocardiography in atrial septal defect: Prediction of atrial fibrillation. Clinical Cardiology, 41(10), 1341–1347. [Google Scholar]

13. Blackshear, J. L., Odell, J. A. (1996). Appendage obliteration to reduce stroke in cardiac surgical patients with atrial fibrillation. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 61(2), 755–759. [Google Scholar]

14. Daher, G., Hassanieh, I., Malhotra, N., Mohammed, K., Switzer, M. P. et al. (2020). Patent foramen ovale prevalence in atrial fibrillation patients and its clinical significance: A single center experience. International Journal of Cardiology, 300, 165–167. [Google Scholar]

15. Versaci, F., Sacca, S., Mugnolo, A., Pacchioni, A., Reimers, B. (2012). Simultaneous patent foramen ovale and left atrial appendage closure. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine (Hagerstown), 13(10), 663–664. [Google Scholar]

16. Koermendy, D., Nietlispach, F., Shakir, S., Gloekler, S., Wenaweser, P. et al. (2014). Amplatzer left atrial appendage occlusion through a patent foramen ovale. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions, 84(7), 1190–1196. [Google Scholar]

17. Gafoor, S., Franke, J., Boehm, P., Lam, S., Bertog, S. et al. (2014). Leaving no hole unclosed: Left atrial appendage occlusion in patients having closure of patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect. Journal of Interventional Cardiology, 27(4), 414–422. [Google Scholar]

18. Yu, J., Liu, X., Zhou, J., Xue, X., Muenzel, M. et al. (2019). Long-term safety and efficacy of combined percutaneous LAA and PFO/ASD closure: A single-center experience (LAAC combined PFO/ASD closure). Expert Review of Medical Devices, 16(5), 429–435. [Google Scholar]

19. Kleinecke, C., Fuerholz, M., Buffle, E., de Marchi, S.,Schnupp, S. et al. (2020). Transseptal puncture versus patent foramen ovale or atrial septal defect access for left atrial appendage closure. EuroIntervention, 16(2), e173–e180. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |