Open Access

Open Access

COMMENTARY

Biological processes involved in mechanical force transmission in connective tissue: Linking bridges for new therapeutic applications in the rehabilitative field

1 UOC Neuroriabilitazione ad Alta Intensità, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, 00168, Italy

2 Department of Geriatrics and Orthopedics, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, 00168, Italy

* Corresponding Author: STEFANO BONOMI. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2024.058418

Received 12 September 2024; Accepted 09 December 2024; Issue published 24 January 2025

Abstract

Connective tissue is a dynamic structure that reacts to environmental cues to maintain homeostasis, including mechanical properties. Mechanical load influences extracellular matrix (ECM)—cell interactions and modulates cellular behavior. Mechano-regulation processes involve matrix modification and cell activation to preserve tissue function. The ECM remodeling is crucial for force transmission. Cytoskeleton components are involved in force sensing and transmission, affecting cellular adhesion, motility, and gene expression. Proper mechanical loading helps to maintain tissue health, while imbalances may lead to pathological processes. Active and passive movement, including manual mobilization, improves connective tissue elasticity, promotes ECM-cell homeostasis, and reduces fibrosis. In rehabilitation, understanding mechanical-regulation processes is necessary for ameliorating and developing treatments aimed at preserving tissue elasticity and preventing fibrosis. In this commentary, we aim to globally describe the biological processes involved in mechanical force transmission in connective tissue as support for translational studies and clinical applications in the rehabilitation field.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Abbreviations

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| GPCRs | G protein-coupled receptors |

| GAGs | Glycosaminoglycans |

| PGs | Proteoglycans |

| MAPK | Mitogen-associated protein kinases |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositol-3-kinase |

| ROCK | Rho-associated protein kinase |

| CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

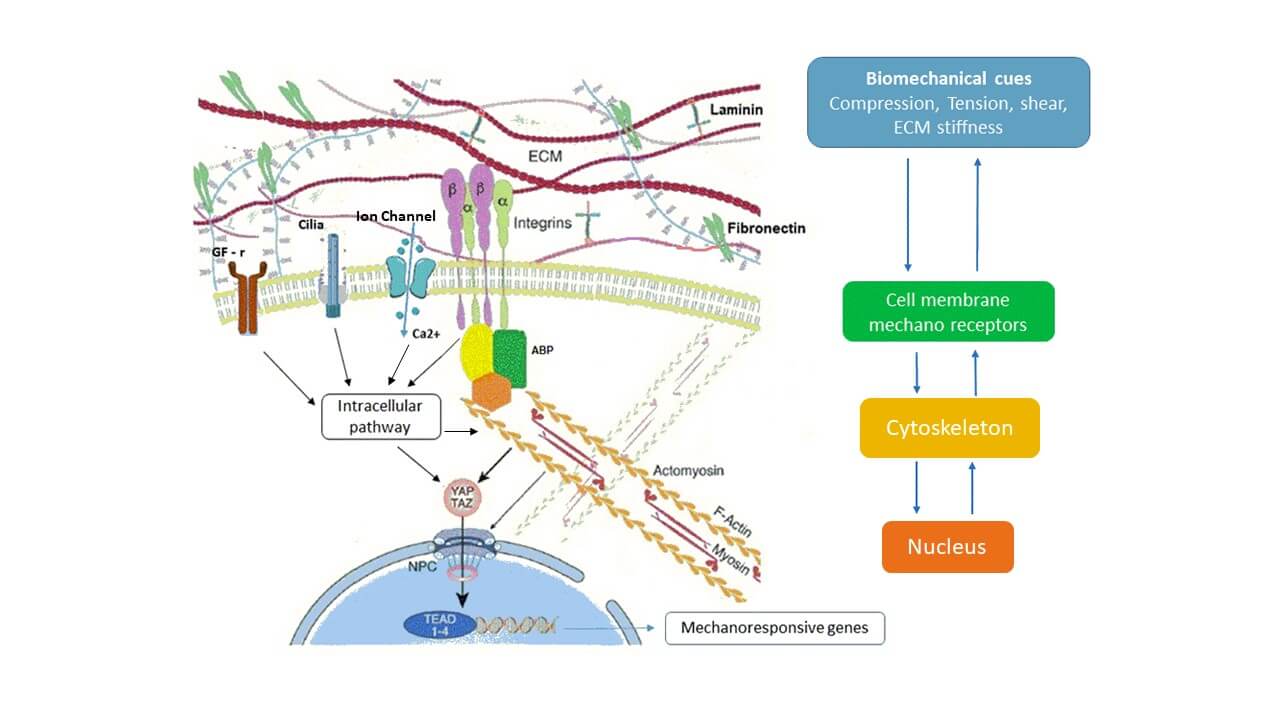

Connective tissue is a complex, dynamic structure that constantly responds to environmental factors to maintain homeostasis, including the integrity of mechanical properties. A complex biological pathway transduces signals from the biomechanical environment to the cell and links biomechanical cues to cell behavior. Signal transduction involves ECM, the cytoplasmic membrane, the cytoskeleton, and the nucleus and eventually affects nuclear chromatin at a genetic and epigenetic level. Mechanoreceptors on cell membrane: integrin proteins, ion channels, primary cilia, growth factor receptors (e.g., for transforming growth factor beta, TGF-β), G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), transduces information from ECM to cytoskeleton [1]. The mechano-regulation process includes matrix modification (deposition, rearrangement, removal) and cell activation, it acts to maintain overall shape and function [2]. Pathologies that lead to prolonged immobilization produce ECM modification and fibroblast activation, increase tissue stiffness and fibrosis, and affect musculoskeletal function [3]. Recent studies show that active and passive movement, including manual mobilization, improves connective tissue elasticity and promotes ECM–cell homeostasis by reducing fibrosis [3,4]. In this paper, we aim to describe mechanical force transmission processes in connective tissue as a bridge for therapeutic applications in the rehabilitation field.

Soft connective tissue is composed of ECM and cells (mainly fibroblasts). ECM consists of fibrillar collagens, elastic fibers, glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and proteoglycans (PGs) surrounded by interstitial fluid [5]. Proteoglycans consist of a protein body with different types of glycosaminoglycans covalently linked; they play an important role in mechanical force transmission [5]. Fibronectin and laminins are crucial components of the ECM that contribute significantly to cell-matrix interactions and overall tissue architecture [6]. In response to chemical and mechanical cues, cells adapt shape, dynamics, and adhesion to ECM [7]. Focal adhesion sites (FAs) are clusters of integrin transmembrane that associate the ECM with the actin cytoskeleton through actin-binding proteins. To adapt cell-matrix interaction, FAs sense and respond to variations in force transmission along the actomyosin-ABP-integrin-ECM pathway [8].

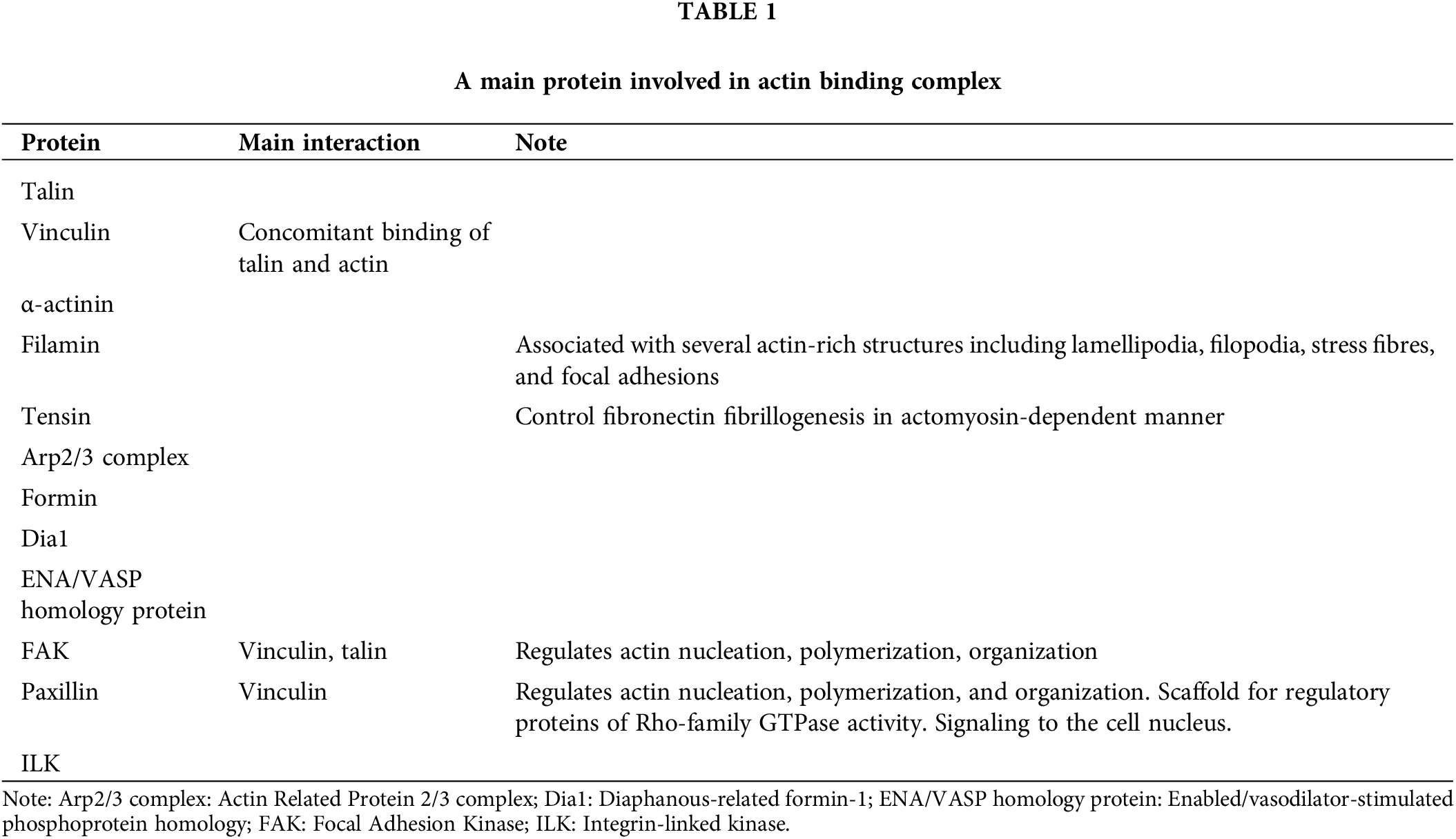

ABP is the linking bridge between actin cytoskeleton and integrin (Table 1). They are grouped into domains with complementary functions: linkage, regulation, and signaling organized into three main horizontal layers between the plasma membrane and actin filaments. Some proteins show a spatial overlap and could modify their position during different phases of the mechanotransduction process [7,9].

Cytoskeletons consist of a tridimensional filamentous structure and crosslinking proteins, that provide mechanical support and regulate cell motility, shape, and tension. It is physiologically under tension, in balance with ECM stiffness. Cell mechanical properties depend on the dynamics, geometry, and polarity of the cytoskeleton composed of actin fibres, microtubules, and intermediate filaments. Single actin filament is long about 9–15 microns and flexible. Bundled actin filaments are stiffer, withstand higher compression, and transmit forces throughout the cell [9]. Cytoskeleton contractility is ensured by actin sliding on the motor protein myosin II, held together by crosslinking proteins (e.g., α-actinin, fascin, filamin) in complex structures called stress fibres [7]. Myosin II is involved in cytoskeleton contractility, elongation of the actin fibres, and the regulation of the ABP-integrin complex [7,9]. Cytoskeleton could transmit forces to the nucleus through biochemical and physical connections inducing changes in gene expression [8].

Mechanotransduction refers to bidirectional ECM-cells exchange of physical forces (in connective tissue usually range 1–10 nN). Mechanical forces result from geometrical and mechanical strains, related to cell position and polarity within the 3D tissue architecture of ECM. Extracellular mechanical forces, typically compression or shear, modify the interaction between ECM and the cytoskeletal tension system. Cells convert this physical stimulus into intracellular biochemical signals [2].

The most important cell mechanoreceptors are integrin proteins that cooperate with other mechanoreceptors: mechanosensitive ion channels (e.g., Ca2+), primary cilia, growth factor receptors (e.g., for TGF-β), GPCRs to interact with cytoskeletal response [1]. Once transmitted over the cell membrane, mechanical force activates multiple interrelated signaling pathways including calcium-dependent targets, nitric oxide signaling, mitogen-associated protein kinases (MAPK), RhoGTPases, and phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) [1].

Integrins connect ECM with the actin cytoskeleton through the Focal Adhesions complex and ABP protein. Mechanical forces modify the size, strength, composition, and signals generated by FAs. As a response, the cell increases actin contractility and restructures its entire cytoskeleton in a process requiring Rho-GTPases, myosin activity, and Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) [10].

Mechanical forces influence ECM conformational changes, promoting spatio-temporal displacement of soluble and matrix-bound effector molecules and growth factors, such as TGF-β. Also, integrins contribute to the activation and release of TGF-β from its reservoir in the extracellular latent complex [1].

Primary cilia are microtubule-based organelles that project from the cell surface. They work as mechanosensory organelles that respond to compression or fluid shear [11].

Mechanical stimuli, including fluid shear stress, stretch, compression, and cell swelling modify the membrane potential and the expression and activity of membrane mechanosensitive ion channel [12]. This process includes Ca2+ influx, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, and extra–intracellular cation exchange [12]. The interaction of mechanosensitive ion channels with integrin, cytoskeletal, and signaling complexes is vital for physiological mechanically induced cell responses [12,13].

On the other side intracellular forces, generated by actomyosin contraction or retrograde translocation of polymerizing actin cytoskeleton filaments, affect ECM. This process is regulated by a “molecular clutch” mechanism, which controls the retrograde movement of actin, directing force to the substratum. ABPs modulate this process [7,9]. Cells sense substrate stiffness and activate a feedback loop, to restructure the cytoskeleton, which involves actomyosin contractility, actomyosin remodeling, and changes in gene expression through nuclear signaling [10].

The Hippo pathway, with its two main downstream effectors YAP and TAZ, represents an important connection between biomechanical cues, cytoskeleton, and cell behavior. Changes in the actin cytoskeleton, disruption of cell polarity, and ECM stiffness modulate the Hippo pathway effectors YAP/TAZ [10]. This signaling cascade influences YAP/TAZ cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling and binding to the transcription factor TEAD, thus promoting the transcription of mechanoresponsive genes [10]. Actin cytoskeletons also affect the mechanics and shape of the nucleus by causing nuclear deformation [10]. Among its transcriptional targets are connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and TGF-β, both of which play important roles in fibrosis development, as well as transglutaminase-2, a molecule involved in ECM deposition, turnover, and crosslinking [1]. YAP/TAZ is involved in cell growth regulation, proliferation, and differentiation. It is also studied in biological processes related to an epigenetic switch to allow the cells to adapt to nutrient deprivation, escape immune control, and promote cell pathological diffusion [10].

In response to mechanical deformation, connective tissue exhibits a viscoelastic response, with a characteristic stress relaxation behavior. Time-dependent and strain-dependent ECM mechanical responses affect cell-matrix mechanotransduction [8]. Stress relaxation tests reveal that connective tissue is released to deform over timescales from tens to hundreds of seconds. ECM structure, composed of collagen fibre networks, interspersed with highly hydrated, flexible polysaccharides and other large molecules, is the key regulator of tissue mechanics and viscoelasticity.

Force dissipation and restoration in ECM depend on different factors. Most collagen network crosslinks are non-covalent and arise from numerous weak bonds with dissociation rates fast enough to allow stresses to relax. Weak bonds restore following matrix deformation and stabilize the tissue state, leading to plastic deformations. Weak crosslinks co-exist with more stable covalent crosslinks, which diminish the mechanical plasticity of the matrix overall. Elastin fibers also promote elastic recovery. Protein unfolding is another mechanism of energy dissipation. Poroelastic effects also contribute to ECM mechanical behaviors. Dissipation due to poroelasticity occurs under tension or compression and results from volume changes due to water flow into or out of the network. Variations in ECM composition, density, and conformation modify matrix water flow under mechanical load, resulting in different viscoelastic responses. Shear deformations modify shape but not volume, and dissipation due to water movement within the matrix is lower [8].

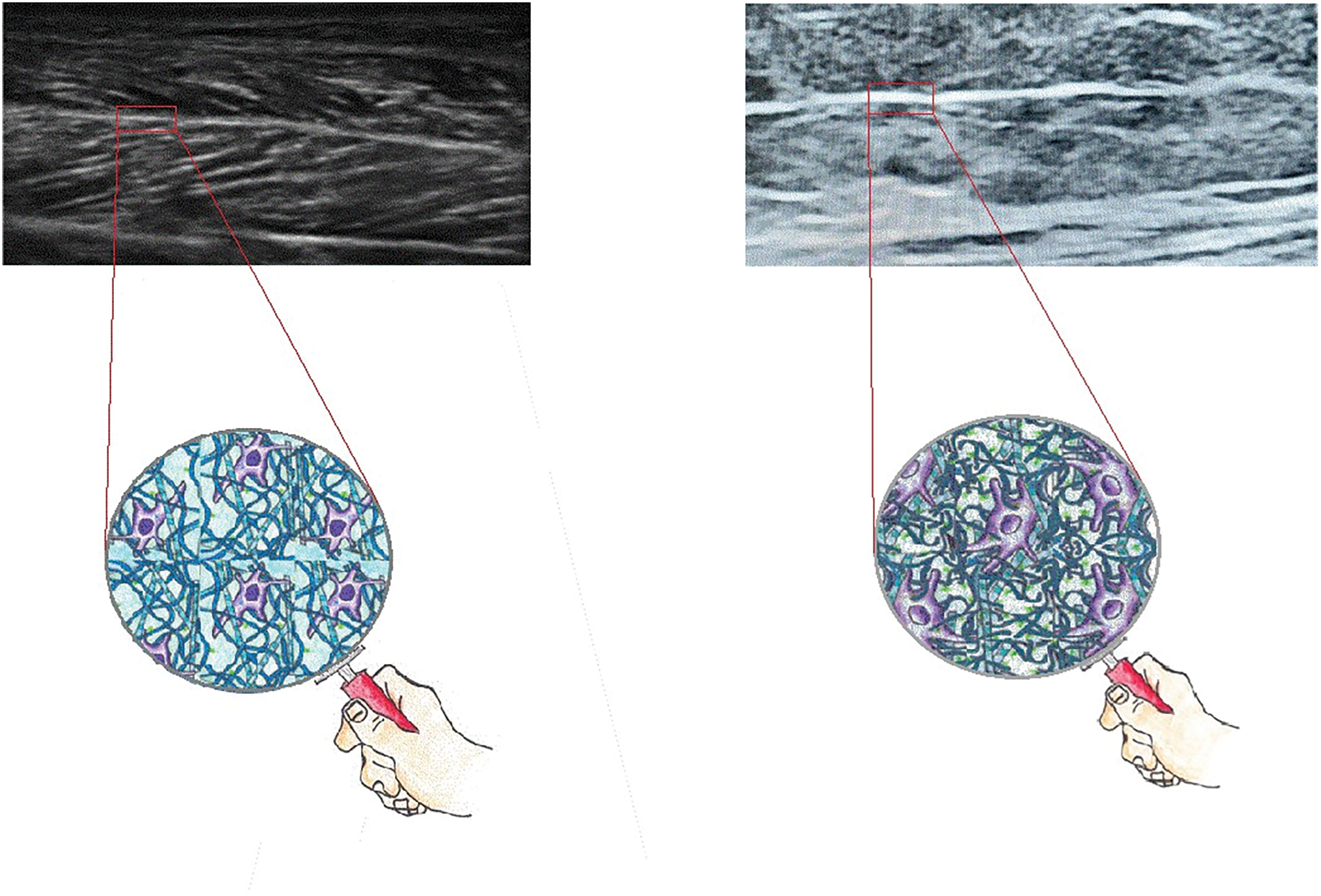

Changes in connective tissue viscoelasticity have been observed in pathologies that lead to prolonged immobilization. Immobilization induces ECM modifications: increase of collagen fibres with network disorganization [3], alteration of glycosaminoglycan composition and function [14], especially increase in hyaluronic acid density and viscosity (see Fig. 1). Furthermore, immobilization leads to fibroblast activation and transformation into myofibroblast with increased collagen production, fibronectin and inflammatory cytokines [15]. Overall, these changes affect the ECM-cell mechanotransduction process and can lead to fibrosis.

Figure 1: Ultrasound image of a portion of medial gemellus muscle, longitudinal section. Left: muscle of a healthy subject. Right: muscle of a plegic leg of a patient 3 months after neurological injuries. High fibrotic muscle (a marked increase of white area): increase, disorganization, and densification of collagen tissue, remodeling of ECM matrix. In the picture the ECM structure. Left: physiologic organization. Right: increased density and viscosity of hyaluronic acid, increased production and disorganization of collagen fiber, increased fibroblast activity.

Increased mechanical loading or matrix stiffness potentially leads to homeostatic regulation or fibrotic conditions. During homeostatic response ECM strain induces a new cell balance, maintaining tissue integrity and function [6]. The pathological response is characterized by: increased cell contractility and formation of actin stress fibers; suppression of collagen-degrading proteases, which prevents matrix degradation; upregulated collagen genes expression, driving excessive collagen deposition; increased sensitivity to TGF-β, which further promotes collagen synthesis [13]. Furthermore, mechanical overloading stimulates the expression of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) and MAPK, which induces the expression of pro-inflammatory and catabolic mediators. This includes nitric oxide, ECM-proteolytic enzymes such as metalloproteinase, aggrecanases, reactive oxygen species, pro-inflammatory mediators such as Interleukin-1 (IL-1) and Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), prostaglandin PGE2. Together these biomolecules trigger inflammatory pathways in a positive feedback loop that increases catabolic activities, finally leading to fibrosis [1]. On the other hand, a physiological mechanical load promotes a shift from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory response, for example promoting the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4 [3].

Implication for Rehabilitation

The application of mechanical forces in rehabilitation is a widely studied field. It ranges from physical therapies, such as shock wave therapies; to improving wound healing therapies such as microdeformational wound therapy; conservative or surgical scar treatments, and many others [11].

In rehabilitation, different strategies have been proposed to reduce connective tissue stiffness and improve muscular skeletal function: active and induced movement, stretching, manual mobilization, botulinum toxin injections, injection of hyaluronic acid, and also surgical procedures.

Connective tissue modifies viscoelastic behavior in response to applied mechanical forces more rapidly than other tissues [14]. Recent studies have demonstrated that active and passive movement promote ECM–cell homeostasis and enhance connective tissue elasticity, thereby mitigating the progression of fibrosis [3,4]. Continuous passive movement and stretching, within the pain-free range, improve connective tissue elasticity and reduce inflammation [16]. Cyclic mechanical loading, such as continuous passive movement, decreases TGF-β production and myofibroblast transformation, limiting fibrosis [17]. This highlights the importance of gentle movement and stretching to manage connective tissue stiffness and reduce fibrosis, especially after prolonged immobilization. Some studies shed light on the possibility that gentle manual mobilization could modify connective tissue mechanical properties: mobility, density, viscosity, and reduce connective tissue stiffness [14,18]. Different biological mechanisms have been proposed to support these effects: reversal of the aggregation of the hyaluronic acid fragments, restoring normal gliding between connective tissue layers, realignment of collagen fibres, and restoring the balance between ECM synthesis and degradation [3,14]. In addition, we hypothesized that gentle manual mobilization could improve ECM–cell balance also involving the mechanotransduction process, and contribute to preventing the fibrosis process.

Although this is a highly promising field, challenging questions emerge in terms of specificity, selectivity, and timeliness. Thresholds to mechanical stimuli may change in different cells and tissues so application should be defined in a tissue-specific manner. Therefore type, amplitude, duration, and frequency should be dosed correctly. In other words, therapeutic applications should be chosen and dosage appropriately in a specific rehabilitation program in tune with the patient’s needs.

In this paper, we highlight the significance of physiological mechanical load in maintaining connective tissue health and preventing tissue fibrosis. Knowledge about ECM-cell interaction processes is vital for translational studies and addressing non-invasive treatments in the rehabilitative field, aimed at maintaining tissue elasticity and preventing fibrosis progression.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge contributions to the content of this paper: (1) Dr. Alessia Scaglione (Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Rome) for her contribution in creating the graphical part of the present commentary. (2) Dr. Monica Filisetti for their valuable and faithful support in our endeavor.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Augusto Fusco, Stefano Bonomi, and Luca Padua; methodology, Augusto Fusco, and Stefano Bonomi; formal analysis, Augusto Fusco, and Stefano Bonomi; writing—original draft preparation, Augusto Fusco, and Stefano Bonomi; writing—review and editing, Augusto Fusco, Stefano Bonomi, and Luca Padua; supervision, Luca Padua. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Duscher D, Maan ZN, Wong VW, Rennert RC, Januszyk M, Rodrigues M, et al. Mechanotransduction and fibrosis. J Biomech. 2014;47(9):1997–2005. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.03.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Dieterle MP, Husari A, Rolauffs B, Steinberg T, Tomakidi P. Integrins, cadherins and channels in cartilage mechanotransduction: perspectives for future regeneration strategies. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2021;23:e14. doi:10.1017/erm.2021.16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Mavropalias G, Boppart M, Usher KM, Grounds MD, Nosaka K, Blazevich AJ. Exercise builds the scaffold of life: muscle extracellular matrix biomarker responses to physical activity, inactivity, and aging. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2023;98(2):481–519. doi:10.1111/brv.12916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Koller T. Mechanosensitive aspects of cell biology in manual scar therapy for deep dermal defects. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2055. doi:10.3390/ijms21062055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Gialeli C, Karamanos NK. Extracellular matrix structure. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;97:4–27. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Humphrey JD, Dufresne ER, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(12):802–12. doi:10.1038/nrm3896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Li Mow Chee F, Byron A. Network analysis of integrin adhesion complexes. In: The integrin interactome. New York, NY, USA: Humana; 2020. p. 149–79. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0962-0_10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chaudhuri O, Cooper-White J, Janmey PA, Mooney DJ, Shenoy VB. Effects of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity on cellular behaviour. Nature. 2020;584(7822):535–46. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2612-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Jégou A, Romet-Lemonne G. Mechanically tuning actin filaments to modulate the action of actin-binding proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2021;68:72–80. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2020.09.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Piccolo S, Panciera T, Contessotto P, Cordenonsi M. YAP/TAZ as master regulators in cancer: modulation, function and therapeutic approaches. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(1):9–26. doi:10.1038/s43018-022-00473-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Huang C, Holfeld J, Schaden W, Orgill D, Ogawa R. Mechanotherapy: revisiting physical therapy and recruiting mechanobiology for a new era in medicine. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19(9):555–64. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2013.05.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang K, Wang L, Liu Z, Geng B, Teng Y, Liu X, et al. Mechanosensory and mechanotransductive processes mediated by ion channels in articular chondrocytes: potential therapeutic targets for osteoarthritis. Channels. 2021;15(1):339–59. doi:10.1080/19336950.2021.1903184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Adapala RK, Katari V, Teegala LR, Thodeti S, Paruchuri S, Thodeti CK. TRPV4 mechanotransduction in fibrosis. Cells. 2021;10(11):3053. doi:10.3390/cells10113053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Stecco A, Bonaldi L, Fontanella CG, Stecco C, Pirri C. The effect of mechanical stress on hyaluronan fragments’ inflammatory cascade: clinical implications. Life. 2023;13(12):2277. doi:10.3390/life13122277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Usher KM, Zhu S, Mavropalias G, Carrino JA, Zhao J, Xu J. Pathological mechanisms and therapeutic outlooks for arthrofibrosis. Bone Res. 2019;7:9. doi:10.1038/s41413-019-0047-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Berrueta L, Muskaj I, Olenich S, Butler T, Badger GJ, Colas RA, et al. Stretching impacts inflammation resolution in connective tissue. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231(7):1621–7. doi:10.1002/jcp.25263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Ferretti M, Srinivasan A, Deschner J, Gassner R, Baliko F, Piesco N, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of continuous passive motion on meniscal fibrocartilage. J Orthop Res. 2005;23(5):1165–71. doi:10.1016/j.orthres.2005.01.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Burk C, Perry J, Lis S, Dischiavi S, Bleakley C. Can myofascial interventions have a remote effect on ROM? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sport Rehabil. 2019;29(5):650–6. doi:10.1123/jsr.2019-0074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools