Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Apatinib reduces liver cancer cell multidrug resistance by modulating NF-κB signaling pathway

1 Department of Gastroenterology, The Central Hospital of Wuhan, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, 430022, China

2 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Pingshan Hospital, Southern Medical University (Pingshan District People’s Hospital of Shenzhen), Shenzhen, 518118, China

* Corresponding Author: SHUCAI YANG. Email:

BIOCELL 2024, 48(9), 1331-1341. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2024.052625

Received 09 April 2024; Accepted 05 June 2024; Issue published 04 September 2024

Abstract

Objectives: This investigation aimed to elucidate the inhibitory impact of apatinib on the multidrug resistance of liver cancer both in vivo and in vitro. Methods: To establish a Hep3B/5-Fu resistant cell line, 5-Fu concentrations were gradually increased in the culture media. Hep3B/5-Fu cells drug resistance and its alleviation by apatinib were confirmed via flow cytometry and Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK8) test. Further, Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) siRNA was transfected into Hep3B/5-Fu cells to assess alterations in the expression of multidrug resistance (MDR)-related genes and proteins. Nude mice were injected with Hep3B/5-Fu cells to establish subcutaneous xenograft tumors and then categorized into 8 treatment groups. The treatments included oxaliplatin, 5-Fu, and apatinib. In the tumor tissues, the expression of MDR-related genes was elucidated via qRT-PCR, immunohistochemistry, and Western blot analyses. Results: The apatinib-treated mice indicated slower tumor growth with smaller size compared to the control group. Both the in vivo and in vitro investigations revealed that the apatinib-treated groups had reduced expression of MDR genes GST-pi, LRP, MDR1, and p-p65. Conclusions: Apatinib effectively suppresses MDR in human hepatic cancer cells by modulating the expression of genes related to MDR, potentially by suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway.Keywords

Primary liver cancer, specifically hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the 5th most frequent malignancy and 3rd major cause of cancer-linked mortality worldwide. Recent statistics show a distressing increase in incidence, with over 700,000 new cases diagnosed annually [1–4]. Despite advancements in treatment options such as surgery, chemotherapy, radiofrequency ablation, and liver transplantation, liver cancer continues to exhibit high recurrence rates and mortality [5–8]. Particularly, chemotherapy, a crucial element of combination therapy, is compromised by multidrug resistance (MDR), a persistent challenge that severely limits treatment efficacy [9]. Previous studies have identified the main mechanism behind MDR as the increased activity of transporter proteins, including P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which are stimulated by the ABCB1 (MDR1) gene and effectively reduce the intracellular concentration of chemotherapeutic agents, leading to resistance [10,11]. Furthermore, the MDR-associated protein (MRP), topoisomerase IIα (Topo IIα), glutathione-S-transferase pi (GST-pi), and lung resistance protein (LRP/MVP) are also key contributors to multidrug resistance in chemotherapy [12–14].

Given the limitations of existing therapies to counteract MDR, this study introduces apatinib (YN968D1), a novel antiangiogenic agent and a selective suppressor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2). Apatinib has demonstrated significant effectiveness and tolerability in treating advanced gastric and liver cancers, suggesting the potential to also impact MDR mechanisms. The innovation of this research lies in its focus on examining apatinib’s ability to modulate the expression and function of key MDR proteins in liver cancer cells, potentially offering a new therapeutic avenue to enhance chemotherapeutic efficacy and improve outcomes in patients [15–17].

This investigation aimed to elucidate the impact of apatinib on multidrug resistance in liver cancer. We intend to establish a multidrug-resistant cell line and a subcutaneous xenograft model of liver cancer to examine how apatinib affects the expression of essential MDR genes, including LRP, MRP2, GST-pi, MDR1, and Topo IIα. This research will provide additional theoretical support for the clinical use of apatinib in treating liver cancer.

Hengrui Medicine Company (Jiangsu, China) provided Apatinib (IUPAC name: N-[4-(1-cyanocyclopentyl) phenyl]-2-(pyridin-4-ylmethylamino) pyridine-3-carboxamide; methanesulfonic acid) mesylate tablets (AITAN®; 425 mg/tablet). For in vitro cell experiments, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 100%; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) was employed as a solvent to prepare a 4 mmol/L solution. In the in vivo experiment, DMSO was utilized to dissolve the tablet to 200 g/L dilution (containing less than 0.1% (v/v) DMSO). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, 11965126, Grand Island, NY, USA), 5-Fluorouracil (5-Fu) was provided by the Kingyork Company (Tianjin, China). Oxaliplatin was purchased from Sanofi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China) Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was acquired from the HyClone (SH30071.03HI, Logan, UT, USA). The BCA kit was purchased from Thermo Scientific (23225, Waltham, MA, USA). The RNA isolation and PCR reagents, TRIzol (15596026) and Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (4368577), respectively, were provided by Thermo Scientific. Google Biotechnology Ltd. (Wuhan, China) synthesized the PCR primers. P-gp antibody (sc-55510) was bought from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-MRP2 (24893-1-AP), anti-p-p65 (82335-1-RR), anti-p65 (80979-1-RR), anti-LRP (16478-1-AP), anti-p-IKB (82349-1-RR), anti-IKB (10268-1-AP), anti-GST-pi (15902-1-AP), and anti-Topo IIα (20233-1-AP) antibodies were purchased from the ProteinTech Group (Chicago, IL, USA).

Human hepatic cancer cell lineage (Hep3B) was provided by the China Center for Type Culture Collection in Wuhan, China, and propagated at 37°C in DMEM media augmented with FBS (10%) and penicillin-streptomycin (1%; Thermo Scientific, 15140122, Waltham, MA, USA) in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. The media was refreshed every 2–3 days, and upon 80%–90% confluency, the cells were passaged at a 1:4 split ratio.

In vitro analysis of apatinib’s effect on multidrug resistance

Establishment of a multidrug-resistant liver cancer cell line

To construct a Hep3B/5-Fu resistant cell subline, 5-Fu concentration was gradually increased in the culture media. Initially, Hep3B cells were grown in a media comprising 500 μg/L of 5-Fu and the medium was refreshed every 3 days. Upon reaching the logarithmic growth phase, the 5-Fu concentration in the cells was doubled with each medium change; this process was repeated continuously. After six months, the Hep3B/5-Fu cells were propagated in a media comprising 20,000 μg/L of 5-Fu to preserve their drug resistance. One week before the experiments, the cells were transferred to DMEM lacking 5-Fu to prepare for subsequent tests. The cells were passaged every 3 to 4 days at a 1:2 split ratio.

Analysis of the drug sensitivity of Hep3B/5-Fu cells by CCK8

The log-phase Hep3B and Hep3B/5-Fu cells (5 × 103/well) were trypsinized and grown in 96-well plates. After overnight incubation, the media was refreshed with fresh DMEM, and three types of chemotherapy drugs were added. Each drug was serially diluted to achieve six different drug concentrations, with the maximum concentration of each drug as follows: epirubicin (Thermo Scientific, T14A061, Waltham, MA, USA) (6.0 mg/L), 5-Fu (80.0 mg/L), and oxaliplatin (2.0 mg/L). Each concentration was tested in triplicate wells. Additionally, three untreated control wells and three cell-free wells were established. After 48 h of incubation, the drug-containing media was replaced with fresh media, and the cells were cultured for an additional 24 h. According to the CCK8 kit’s instructions (APExBIO, K1018, Houston, TX, USA), serum-free medium (80 μL) and CCK8 reagent (6 μL) were added per well, and after 1 h, the absorbance at a wavelength of 492 nm was assessed via a microplate reader (MULTISKAN FC, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A modified method was employed to calculate the 50% inhibition rate (IC50) of various chemotherapeutic drugs in both Hep3B/5-Fu and Hep3B cells, as well as the drug resistance index ((RI) = IC50 (Hep3B/5-Fu)/IC50 (Hep3B)).

Analysis of Hep3B/5-Fu cell resistance reversal by CCK8

The experimental groups were categorized as follows: the blank control group (DMEM); Apatinib groups (apatinib at concentrations of 10, 20, and 40 μmol/L); 5-Fu groups (5-Fu at a concentration of 1/2 IC50); and Apatinib and 5-Fu combination groups (5-Fu (1/2 IC50) + apatinib (10, 20, and 40 μmol/L)). Each group was replicated three times. The cellular morphology was examined via a microscope (Ti-S, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, USA), and the OD values were determined using the CCK8 assay. The rate of growth inhibition was assessed with the following formula: Cell growth inhibition rate (%) = (ODcontrol group − ODexperimental group)/ODcontrol group × 100%. The reverse index was calculated as (inhibition rate5-Fu+apatinib)/(inhibition rate5-Fu) ×100%.

Hep3B/5-Fu apoptotic rate was assessed via flow cytometry

The experimental groups were organized as follows: control group; 5-Fu groups (5-Fu at a concentration of 1/2 IC50); Apatinib groups at concentrations of 10 and 20 μmol/L; and combination groups of apatinib and 5-Fu (5-Fu (1/2 IC50) + apatinib (10 and 20 μmol/L)). Cells were harvested and rinsed with PBS twice. Apoptosis was assessed with the help of an Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit (BioLegend, 640914, San Diego, CA, USA), per the manufacturer’s protocol. Apoptosis levels were elucidated by flow cytometry (BD, FACSLyric, Franklin Lakes, Bergen, NJ, USA). The apoptotic cell percentage was calculated via FlowJo VX10 (Tree Star, Inc.) software. The experiments were conducted in triplicate.

One day before transfection, logarithmic growth phase cells were seeded. Hep3B/5-Fu cells were plated in a 6-well plate at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well, using a DMEM culture medium without antibiotics. The cell confluence was aimed to be between 60% and 70% at the time of transfection. The experimental groups were organized as follows: a blank control group, a negative control group, and an NF-κB p65 siRNA group (Thermo Scientific, s11915, Waltham, MA, USA). The experiments were conducted in triplicate. qRT-PCR and western blot analyses were used to verify the efficacy of the NF-κB siRNA transfection and to assess changes in the expression of MDR-related genes and proteins.

Analysis of the changes in MDR and NF-κB pathway-related protein expression in Hep3B/5-Fu treated with apatinib

Western blotting was employed to assess changes in the level of MDR and NF-κB pathway-related proteins in Hep3B/5-Fu cells treated with apatinib following NF-κB siRNA transfection. The experiment was structured into three groups, treated with 0, 20, and 40 μmol/L of apatinib. Total proteins were extracted after 48 h. The alterations in the expression of MDR and NF-κB pathway-linked proteins were then analyzed. This set of experiments was conducted in triplicate.

In vivo analysis of apatinib’s effect on multidrug resistance

Establishment of nude mice human tumor xenograft model

Forty-eight BALB/c nude mice, evenly split between females and males, aged 4–6 weeks and weighing 16–23 g, were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. All procedures of mouse experiments were approved (No. [2018] S323) by the Animal Care Committee at Huazhong University of Science and Technology. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The multidrug-resistant liver cancer cell line Hep3B/5-Fu (3 × 106) was added in 200 μL of PBS for subcutaneous inoculation into the mice. Following tumor formation, the maximum (A) and minimum (B) diameters were elucidated with a Vernier caliper. For tumor volume assessment, the following formula was employed: V(mm3) = AB2/2 [18]. After one week, once 100 mm3 tumor size was achieved, the mice were randomly categorized into 8 groups of six each: Control, Apatinib monotherapy (50 mg/kg/day) (19), 5-Fu monotherapy (20 mg/kg, 2 times/week), Oxaliplatin monotherapy (6 mg/kg, 2 times/week), 5-Fu + Oxaliplatin, Apatinib + 5-Fu, Apatinib + Oxaliplatin and Apatinib + 5-Fu + Oxaliplatin.

Mice were euthanized 24 h after the last drug administration. Tumors were excised and measured; some were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for Western blot and qRT-PCR analyses, while others were fixed in 100 g/L formaldehyde for immunohistochemical staining.

Analysis of MDR-related gene expression in tumor tissues by qRT-PCR and Western blot

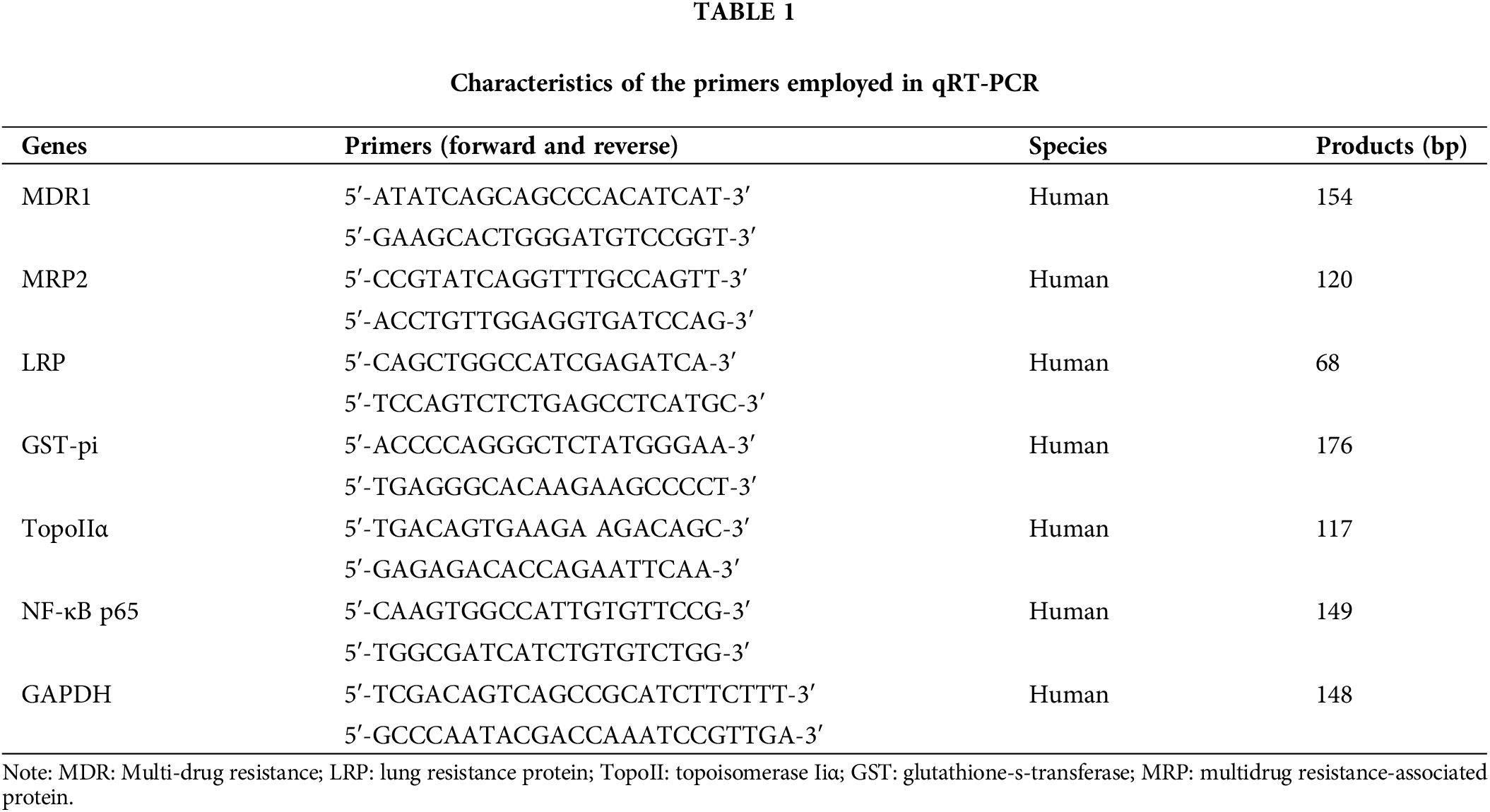

The levels of MDR-linked genes were assessed in the xenografted tumor tissues of the control, apatinib, 5-Fu, and apatinib + 5-Fu groups. qRT-PCR: Total RNA was extracted from xenografted tumor tissues using the Trizol reagent (15596018, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (RR036A, Takara, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) in a 20 μL reaction volume. Amplification and quantification were performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, 4334973, Waltham, MA, USA) on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Each reaction mixture (20 μL total volume) contained 10 μL of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 0.5 μL of each primer (10 μM), 2 μL of cDNA, and 7 μL of nuclease-free water. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Melting curve analysis was performed to verify the specificity of the PCR products. The relative expression levels of genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, with GAPDH as the reference gene [19]. The specific PCR primers used are listed in Table 1.

Western blot: Proteins were extracted from homogenized tumor tissues using RIPA buffer (R0278, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein concentration was determined by the Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit (1-1KT, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) membranes (03010040001, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST (Thermo Scientific, 28360, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies against MDR1, MRP2, LRP, GST-pi, TopoIIα, NF-κB p65, and GAPDH (1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. GAPDH served as the loading control. Protein bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (GE Healthcare, RPN2132, Chicago, IL, USA).

These experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and accuracy.

Analysis of multidrug resistance gene expression by immunohistochemistry

The excised tumor tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 to 48 h to preserve the tissues adequately. After fixation, tissues were dehydrated in an ascending series of ethanol, cleared in xylene, and then embedded in paraffin wax. The paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 4 micrometers using a microtome (Shenyang Hengsong Technology Co., Ltd., HS-S7220-B, Shenyang, Liaoning, China). Sections were stained using Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE). Hematoxylin was used at a concentration of 1% for nuclear staining, and Eosin was used at a concentration of 0.5% for cytoplasmic staining. Streptavidin peroxidase (SP) method was used for immunohistochemical staining. Tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies (1:200 dilution, MRP2 (GeneTex, GTX130181, Irvine, CA, USA), P-gp (KA&M BIO, ANT(B)0337, Shanghai, China), GST-pi (Novatein Biosciences, Woburn, MA, USA), LRP (ProSci, PSI-15-516, Poway, CA, USA), Topo IIα (KA&M BIO, ANT(B)0092, Shanghai, China)) followed by an HRP-conjugated streptavidin-biotin complex (used at a dilution recommended by the kit, Thermo Scientific, E40970, Waltham, MA, USA). The expression levels of MRP2, P-gp, GST-pi, LRP, and Topo IIα were evaluated using a semiquantitative scoring system as outlined in reference [20]. This approach ensures a structured assessment of protein expression across the samples.

Data are depicted as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was employed for statistical analyses. Inter-group comparisons were conducted via the independent sample t-test. For multiple group comparisons, analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test was utilized. p-value of <0.05 was set as the statistical significance threshold. N = 3 for repeated times for each assay.

Apatinib inhibits MDR-related gene expression in vitro

Hep3B/5-Fu cell line overexpression of MDR genes

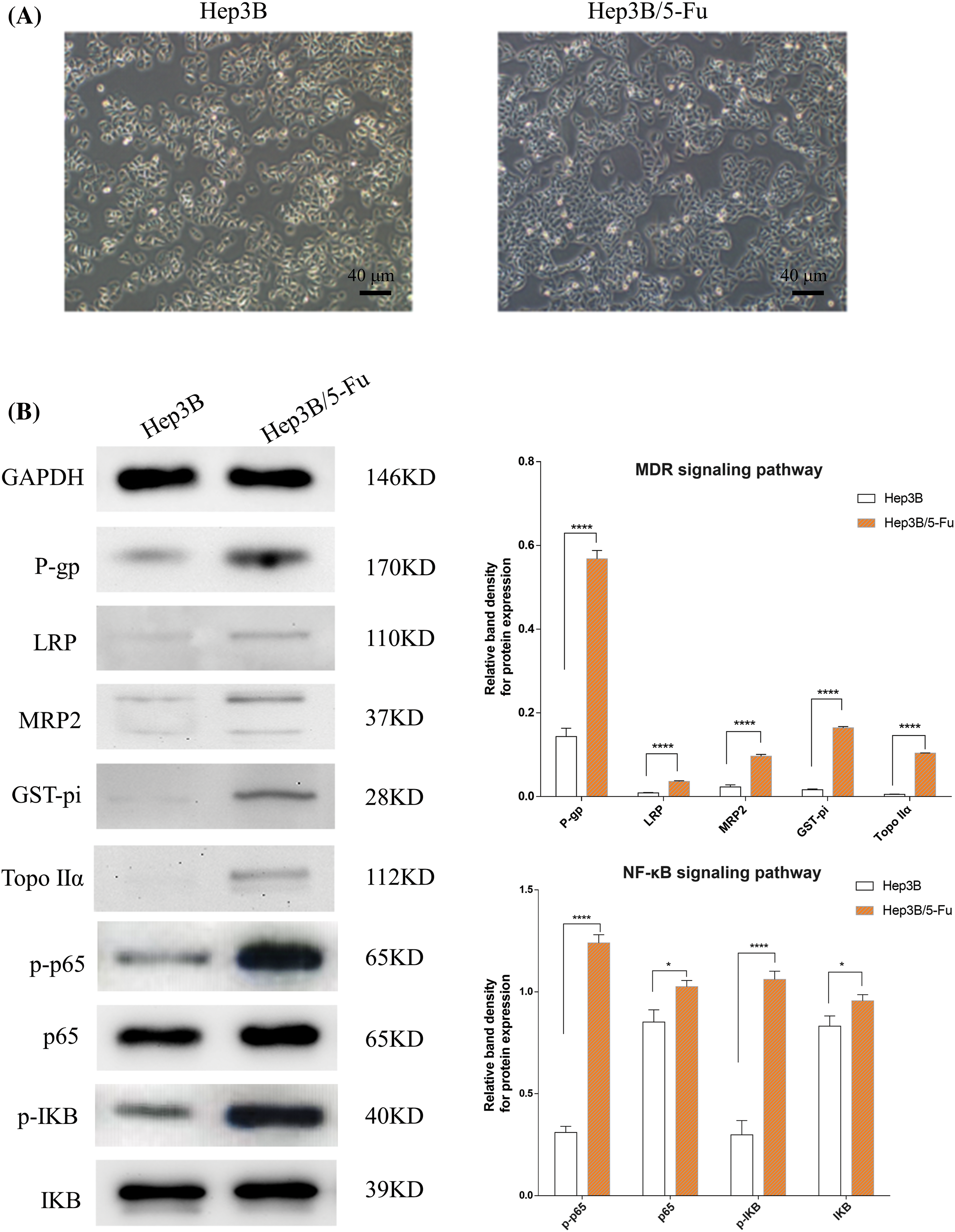

To evaluate the impact of apatinib on MDR in liver cancer, we first established an MDR liver cancer cell line. After six months of culture, Hep3B cells were successfully maintained in a medium containing 20,000 μg/L 5-Fu. The morphological changes in the Hep3B/5-Fu cells were observed under an optical microscope (Fig. 1A). Compared to the parental Hep3B cells, the drug-resistant Hep3B/5-Fu cells exhibited reduced cell adhesion and a more elongated, fusiform shape with the formation of pseudopodia. Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B) revealed significant increases in the levels of MDR-related proteins P-gp, LRP, MRP2, GST-pi, and Topo IIα (p < 0.05) in the Hep3B/5-Fu cells compared to Hep3B. This suggests that prolonged exposure to chemotherapeutic agents leads to the overexpression of MDR-related proteins and the development of drug resistance. Furthermore, p-p65 and p-IKB expression was markedly up-regulated in the Hep3B/5-Fu cells compared to Hep3B cells (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1B), indicating an enhanced activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in the multidrug-resistant cell line.

Figure 1: The morphological changes of the drug-resistant cell line Hep3B/5-Fu and the expression changes of MDR and NF-κB signaling pathway-linked proteins (n = 3). (A) The morphological alterations of the Hep3B/5-Fu cells were assessed via an optical microscope (scale bar: 40 μm) (B) Western blotting detected the levels of MDR and NF-κB signaling pathway-linked protein expression in the Hep3B and Hep3B/5-Fu cell lines. GAPDH was utilized as a loading control (*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001).

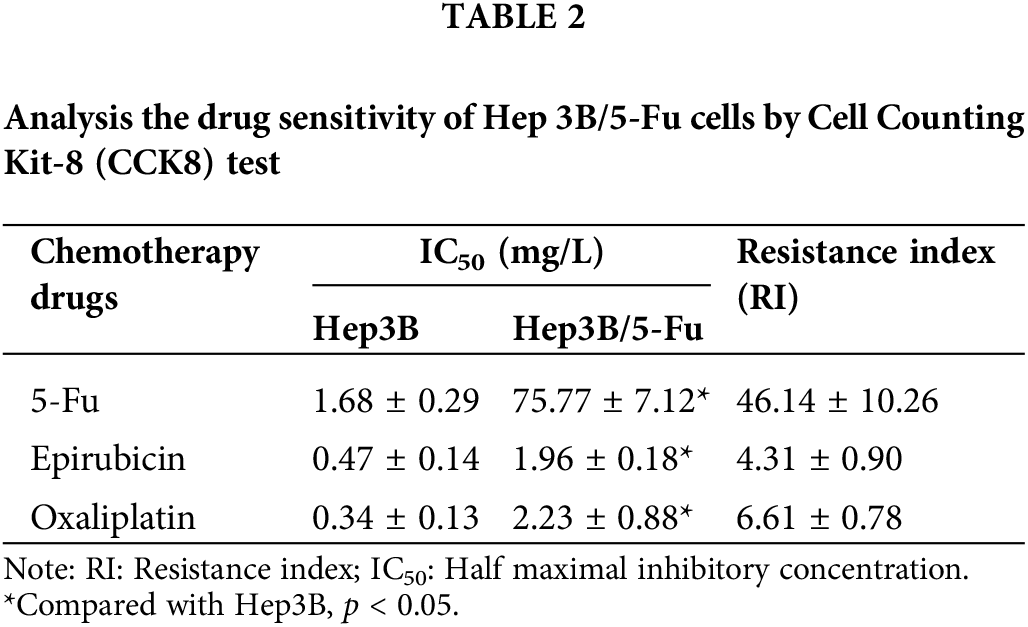

Significantly reduced drug sensitivity of Hep3B/5-Fu cells

To further confirm the MDR characteristics of Hep3B/5-Fu cells, a drug sensitivity test was performed. As detailed in Table 2, Hep3B/5-Fu cells demonstrated varying degrees of resistance to different chemotherapeutic agents compared to the parent Hep3B cells. Notably, Hep3B/5-Fu cells exhibited substantial resistance to 5-Fu, with a drug resistance index of 46.14 ± 10.26. The resistance indexes for epirubicin and oxaliplatin were 4.31 ± 0.90 and 6.61 ± 0.78, respectively. These findings confirm the successful establishment of the MDR liver cancer cell line Hep3B/5-Fu.

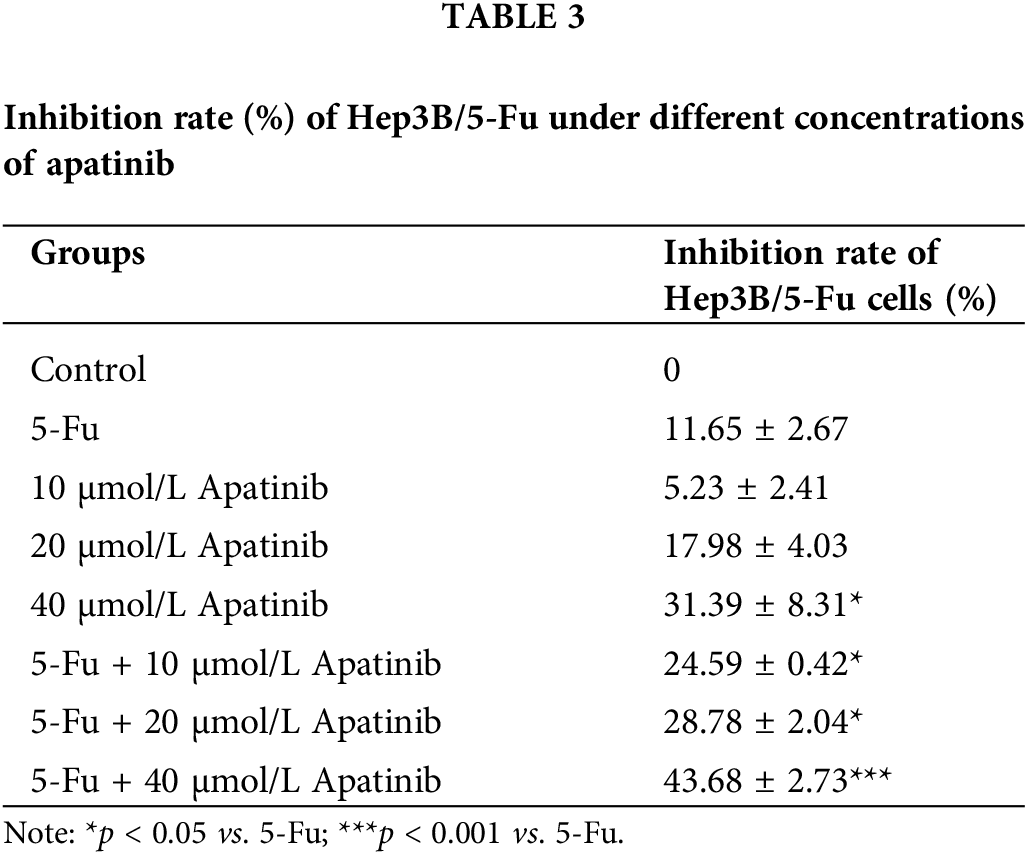

Apatinib reverses drug resistance of Hep3B/5-Fu cells

The inhibition rate of Hep3B/5-Fu cells in 40 μmol/L apatinib alone was (31.39 ± 8.31)%, which was significantly higher than that of the 5-Fu group ((11.65 ± 2.67)%, p < 0.05). When apatinib was combined with 5-Fu, there was a notable increase in efficacy even at a lower concentration of 10 μmol/L, with an inhibition rate of 24.59 ± 0.42%. This rate further increased with higher concentrations of apatinib, reaching (43.68 ± 2.73)% at 40 μmol/L apatinib combined with 5-Fu. The reversal index ranged from 2.19 to 3.86 and increased with the apatinib concentration. The inhibition rate of apatinib combined with 5-Fu was significantly higher than that of 5-Fu (p < 0.05) (Table 3). These findings demonstrate that apatinib can effectively reverse the drug resistance in Hep3B/5-Fu cells.

Apatinib promotes apoptosis of Hep3B/5-Fu cells

Apatinib at a concentration of 10 μmol/L enhanced apoptosis in Hep3B/5-Fu cells, with the apoptotic rate increasing as the concentration of apatinib increased. The apoptotic rate of the combination of apatinib and 5-Fu was significantly higher than that of the Apatinib or 5-Fu monotherapy (p < 0.05). Such as the combination of apatinib (20 μmol/L) and 5-Fu resulted in an apoptotic rate of 52.12 ± 3.23%, which was significantly higher than the rates observed in the apatinib alone (20 μmol/L) group at 28.89 ± 1.98% (p < 0.001), and the 5-Fu group at 19.10 ± 1.29% (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Statistical t-test validated that the differences were significant (p < 0.01). This indicates a synergistic effect of apatinib and 5-Fu in promoting Hep3B/5-Fu cell apoptosis.

Figure 2: The apoptosis rate of Hep3B/5-Fu cells was detected by flow cytometry (n = 3). ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Transfected NF-κB siRNA in Hep3B/5-Fu downregulates the expression of P-gp and LRP

The results of real-time PCR are depicted in Fig. 3A. In comparison with the blank control and negative control groups, the NF-κB siRNA group showed markedly reduced expression levels of p65. Therefore, successful transfection of NF-κB siRNA was verified. Among the assessed MDR-related genes, MDR1 and LRP showed downregulated mRNA expression in the NF-κB siRNA group (p < 0.01). The difference in MRP2, GST-pi, and Topo IIα expression among the three groups was not statistically significant (p ≥ 0.05). Western blot analysis, depicted in Fig. 3B, also demonstrated that NF-κB siRNA transfection in Hep3B/5-Fu cells led to the downregulation of P-gp and LRP at the protein level, further validating the PCR results.

Figure 3: Apatinib downregulates the levels of MDR-linked genes and NF-κB signaling pathway constituents (n = 3). (A, B) The NF-κB siRNA transfected Hep3B/5-Fu cells had downregulated P-gp and LRP levels, as evidenced by qRT-PCR and Western blot. (C) A Western blot was carried out to elucidate the alterations in the expression of MDR and NF-κB signaling pathway-linked proteins following apatinib treatment in NF-κB siRNA transfected Hep3B/5-Fu cells. GAPDH served as the loading control throughout. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Apatinib downregulates the levels of MDR-related proteins and NF-κB signaling pathway constituents

Western blotting in Fig. 3C revealed substantial reductions in the expression of the MDR-related proteins LRP, MDR1, and GST-pi in the apatinib-treated cohort than the control cohort (p < 0.01). Among these, P-gp exhibited the most pronounced decrease, especially at higher concentrations of apatinib (40 μmol/L). Additionally, there was a noticeable decrease in phosphorylated IκBα (p-IκBα) and p65 (p-p65) levels in the apatinib-treated cohort than the control cohort (p < 0.05). However, the expression differences for MRP2, Topo IIα, total p65, and IκBα between the control and apatinib-treated groups were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The ratios of phosphorylated to total p65 (p-p65/p65) and IκBα (p-IκBα/IκBα) were significantly lower in the apatinib-treated groups (p < 0.01), indicating a significant inhibition of NF-κB pathway activation by apatinib.

Apatinib inhibits MDR-related gene expression in vivo

Apatinib suppressed the growth of subcutaneous xenograft tumors in nude mice

Prior to drug administration, the tumor volumes were recorded for the control group and the seven treatment groups, with values of 155.43 ± 46.79 mm³, 152.49 ± 66.80 mm³, 149.72 ± 27.78 mm³, 168.50 ± 32.89 mm³, 162.37 ± 44.54 mm³, 173.49 ± 38.05 mm³, 151.24 ± 32.43 mm³, and 179.94 ± 35.92 mm³, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed among these initial measurements (p ≥ 0.05). However, as the drug administration period progressed, divergences in tumor volumes among the eight groups became more pronounced, with measurements taken 24 h after the final drug administration.

During the treatment period, tumor volumes were assessed and documented every three days. The resulting tumor growth curves, as illustrated in Fig. 4A, demonstrated that the groups receiving combined treatment (apatinib plus chemotherapy) exhibited significantly lower tumor growth rates compared to those receiving chemotherapy alone (p < 0.05). Notably, the group treated with the triple-drug combination of Apatinib, 5-Fu, and Oxaliplatin showed the slowest growth rate and the smallest tumor volumes.

Figure 4: Apatinib inhibits the growth of subcutaneous xenograft tumors (n = 3). (A) Tumor growth curves of BALB/c-nu mice. (B) Sizes of stripped tumor tissues of the eight different treatment groups after the last drug administration. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The nude mice were euthanized at the end of the treatment schedule, and the tumors were harvested for measurement. The tumor volume in the Apatinib + 5-Fu + Oxaliplatin group was substantially smaller than in all other groups, corroborating the trends observed in the tumor growth curves (Fig. 4B). This suggests a superior efficacy of this combination therapy in reducing tumor growth.

Apatinib downregulates the levels of MDR-linked genes in tumor tissues

Real-time PCR results depicted in Fig. 5A show that, compared with the control and apatinib-treated groups, the 5-Fu group exhibited markedly increased MDR-related gene expression, including MDR1, LRP, MRP2, and GST-pi (p < 0.05). In contrast, the combination treatment group (apatinib + 5-Fu) demonstrated significantly reduced expression levels of these genes when compared to the 5-Fu group alone. The expression of Topo IIα did not show significant differences among the four groups (p > 0.05). To validate these changes at the protein level, Western blot analysis was conducted. The results, shown in Fig. 5B, are consistent with the real-time PCR data, indicating that apatinib effectively suppressed the expression of P-gp, LRP, MRP2, and GST-pi proteins (p < 0.05).

Figure 5: Apatinib downregulates the expression levels of MDR-related genes in tumor tissues (n = 3). (A, B) The expression levels of the MDR1/P-gp, MRP2, LRP, GST-pi, and Topo IIα analyzed by real-time PCR and Western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) Immunohistochemical analyses of MDR1/P-gp, MRP2, LRP, GST-pi, and Topo IIα in xenografts of nude mice. Original magnification, ×200 (scale bar, 50 μm). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

Further confirmation came from immunohistochemistry analysis, with results presented in Fig. 5C. These results demonstrate that the combined treatment of apatinib and 5-Fu significantly downregulated the expression of P-gp, MRP2, LRP, and GST-pi compared to 5-Fu alone, corroborating the findings from both the Western blot and real-time PCR analyses. This comprehensive approach confirms the modulation of drug resistance genes by apatinib in combination with 5-Fu, highlighting its potential to enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy by overcoming drug resistance.

Liver resection (LR) remains the most effective treatment for liver cancer, although studies indicate that 80% of patients experience relapse within five years post-surgery. Furthermore, many patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage with metastases, precluding them from surgical options [21,22]. For these individuals, chemotherapy emerges as a critical treatment modality [23,24]; however, liver cancer’s inherent resistance to many cytotoxic drugs, driven by the expression of drug-resistance genes, poses significant challenges [25].

Angiogenesis is a crucial factor in tumor growth and metastasis, and targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway has proven to be a viable anticancer strategy [26]. Apatinib, a new tumor-targeting drug, is mainly used for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer patients who develop cancer or metastases after standard chemotherapy. Apatinib has a broad-spectrum antitumor effect on solid tumors, including gastric cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, breast cancer, and liver cancer [27]. In addition, the results of a prospective clinical trial showed that apatinib is effective in treating intermediate/advanced liver cancer patients [28]. Therefore, as a specific inhibitor of VEGFR-2, apatinib exerts an inhibitory effect on liver cancer growth, but its effects on MDR need to be further elucidated.

5-FU is a cornerstone drug in the treatment of various cancers, including colorectal, stomach, pancreatic, and breast cancers [29]. Its widespread use makes it a critical focus for understanding and overcoming resistance mechanisms in cancer therapy. 5-FU has well-documented resistance mechanisms, such as alterations in metabolic enzymes, enhanced DNA repair, and evasion of drug-induced apoptosis [30]. Focusing on 5-FU can provide a clear framework to study these mechanisms, which might be applicable to other drugs as well. By understanding the resistance to 5-FU, researchers can develop strategies that might be applicable to other chemotherapeutic agents. This could include the development of combination therapies, the use of molecular markers to predict resistance, or novel drug delivery systems to overcome resistance. In this study, we established the multidrug-resistant liver cancer cell line Hep3B/5-Fu, and developed nude mouse models with subcutaneous liver cancer xenograft tumors to explore apatinib’s potential to reverse chemotherapy resistance both in vitro and in vivo. At the cellular level, we examined the effects of apatinib on cell proliferation and apoptosis using the CCK8 assay and flow cytometry.

P-gp is the expression product of MDR1 that belongs to the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily and is expressed in many tissues in vivo [31]. With the use of MDR drugs, the expression of P-gp increases gradually [32]. Some studies suggest that the sensitivity of patients to chemotherapeutic drugs is inversely proportional to the expression of P-gp [33]. The overexpression of LRP and GST-pi can help cells excrete cytotoxic drugs, and lead to multi-drug resistance [34,35]. To further elucidate the effect of apatinib on the expression of MDR genes, we performed real-time PCR, immunohistochemistry, and Western blot analysis of nude mouse models of subcutaneous liver cancer xenograft tumors. The results showed that both at the mRNA and protein levels, apatinib downregulated the expression of MDR1, LRP, and GST-pi, although its inhibitory effect on MDR1 expression was the most obvious.

It has been reported that apatinib reverses the MDR of tumor cells by inhibiting the efflux function of the ATP-binding cassette transporter protein. This was illustrated by no significant change in the expression of the MDR1 gene at either mRNA or protein levels after treatment of various solid tumor cell lines (KBv200, MCF-7/adr, and S1-M1-80) with apatinib [36]. Our results were contradictory to this previous report and showed that apatinib significantly downregulated the expression of MDR1 (P-gp) in liver cancer cells, which presents an important breakthrough for the research of apatinib on reversing multidrug resistance.

We know that the VEGF/VEGFR-2 signaling pathway is important for the regulation of tumor angiogenesis and presents at the target of many small molecule antitumor drugs to date [37]. It has been reported that in the human epidermoid carcinoma cell line Hep-2, which is resistant to paclitaxel, the MDR1 and VEGF genes have a synergistic effect on multidrug resistance and the invasion process. This synergistic relationship between MDR1 and VEGF is mediated by the increase in VEGFR-2 expression [38]. In addition, it has been suggested that VEGF secreted by tumor cells can upregulate MDR1 expression by activating VEGFR-2 and protein kinase B (AKT), which may be an important mechanism of the development of drug resistance of tumor endothelial cells (TECs) in the tumor microenvironment [39]. Furthermore, this mechanism may be important for apatinib, a VEGFR-2-targeted inhibitor, to remarkably reduce the expression of P-gp. This also confirms our findings that apatinib has great potential to reverse MDR.

In this study, we also found that NF-κB signaling pathway activation in tumor cells is associated with MDR, a phenomenon that has been confirmed in colon cancer and breast cancer [40–42]. Inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway reverses MDR in tumor cells [42]. In this study, we found that apatinib inhibits the activity of the NF-κB signaling pathway. These observations indicate that apatinib inhibits the MDR of liver cancer cells by decreasing MDR-related gene expression via suppression of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

In conclusion, apatinib demonstrates a significant antitumor effect and possesses the capability to reverse the multidrug resistance of liver cancer to chemotherapy. This may be achieved through inhibition of the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Based on the results of this study, we recommend combining apatinib with standard chemotherapeutic drugs for liver cancer patients to prolong survival and achieve a better antitumor effect. This study still has limitations as it primarily focuses on a few genes related to multidrug resistance, potentially overlooking other important resistance mechanisms. Future research needs to further validate the results of this study through more extensive models and clinical trials.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82272986 to SY), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2023A1515010230 to SY), the Science and Technology Foundation of Shenzhen (No. JCYJ20220531094805012 to SY), the Scientific Research Project of Shenzhen Pingshan District Health System (202060 to SY).

Author Contributions: Study design and concept: Xiaoxiao He and Shucai Yang. Data acquisition: Xiaoxiao He, Xueqing Zhou, Jinpeng Zhang and Mingfei Zhang. Data analysis and interpretation: Danhong Zeng and Heng Zhang. Manuscript preparation: Xiaoxiao He and Xueqing Zhou. Manuscript review: Shucai Yang. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All procedures of mouse experiments were approved (No. [2018] S323) by the Animal Care Committee at Huazhong University of Science and Technology. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Akaoka M, Haruki K, Taniai T, Yanagaki M, Igarashi Y, Furukawa K, et al. Clinical significance of cachexia index in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection. Surg Oncol. 2022;45:101881. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2022.101881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Foerster F, Gairing SJ, Ilyas SI, Galle PR. Emerging immunotherapy for HCC: a guide for hepatologists. Hepatology. 2022;75(6):1604–26. doi:10.1002/hep.32447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Xie E, Yeo YH, Scheiner B, Zhang Y, Hiraoka A, Tantai X, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for child-pugh class B advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(10):1423–31. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.3284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wang Y, Sun M, Zhang T, Feng Y, Luo X, Xie M, et al. Role of chemokines in the hepatocellular carcinoma microenvironment and their translational value in immunotherapy. Oncol Transl Med. 2022;8(1):1–17. doi:10.1007/s10330-022-0556-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Santucci C, Carioli G, Bertuccio P, Malvezzi M, Pastorino U, Boffetta P, et al. Progress in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival: a global overview. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2020;29(5):367–81. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kulik L, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(2):477–91 e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Dimitroulis D, Damaskos C, Valsami S, Davakis S, Garmpis N, Spartalis E, et al. From diagnosis to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemic problem for both developed and developing world. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(29):5282–94. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i29.5282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Huang S, Wang G. Xiaoaiping injection affects the invasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by controlling AFP expression. Oncol Transl Med. 2023;9(1):35–42. doi:10.1007/s10330-022-0616-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Gosalia AJ, Martin P, Jones PD. Advances and future directions in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;13(7):398–410. [Google Scholar]

10. Cirqueira CS, Felipe-Silva AS, Wakamatsu A, Marins LV, Rocha EC, de Mello ES, et al. Immunohistochemical assessment of the expression of biliary transportation proteins MRP2 and MRP3 in hepatocellular carcinoma and in cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2019;25(4):1363–71. doi:10.1007/s12253-018-0386-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen CJ, Chin JE, Ueda K, Clark DP, Pastan I, Gottesman MM, et al. Internal duplication and homology with bacterial transport proteins in the mdr1 (P-glycoprotein) gene from multidrug-resistant human cells. Cell. 1986;47(3):381–9. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(86)90595-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dallavalle S, Dobricic V, Lazzarato L, Gazzano E, Machuqueiro M, Pajeva I, et al. Improvement of conventional anti-cancer drugs as new tools against multidrug resistant tumors. Drug Resist Updat. 2020;50:100682. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2020.100682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li S, Li B, Wang J, Zhang D, Liu Z, Zhang Z, et al. Identification of sensitivity predictors of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for the areatment of adenocarcinoma of gastroesophageal junction. Oncol Res. 2017;25(1):93–7. doi:10.3727/096504016X14719078133564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang J, Zhang J, Zhang L, Zhao L, Fan S, Yang Z, et al. GST-pi and TopoIIalpha and intrinsic resistance in human lung cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2011;26(5):1081–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Fathi Maroufi N, Rashidi MR, Vahedian V, Akbarzadeh M, Fattahi A, Nouri M. Therapeutic potentials of apatinib in cancer treatment: possible mechanisms and clinical relevance. Life Sci. 2020;241:117106. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2019.117106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Xiong J, Wu C, Bai Y, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1448–54. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Xu J, Shen J, Gu S, Zhang Y, Wu L, Wu J, et al. Camrelizumab in combination with apatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (RESCUEa nonrandomized, open-label, phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(4):1003–11. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Yang SL, Liu LP, Niu L, Sun YF, Yang XR, Fan J, et al. Downregulation and pro-apoptotic effect of hypoxia-inducible factor 2 alpha in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(23):34571–81. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.v7i23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. He X, Huang Z, Liu P, Li Q, Wang M, Qiu M, et al. Apatinib inhibits the invasion and metastasis of liver cancer cells by downregulating MMP-related proteins via regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:3126182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

20. Guo Z, Zhang X, Zhu H, Zhong N, Luo X, Zhang Y, et al. TELO2 induced progression of colorectal cancer by binding with RICTOR through mTORC2. Oncol Rep. 2021;45(2):523–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

21. Dai XM, Huang T, Yang SL, Zheng XM, Chen GG, Zhang T. Peritumoral EpCAM is an independent prognostic marker after curative resection of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Dis Markers. 2017;2017:8495326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. doi:10.3322/caac.v71.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhou H, Song T. Conversion therapy and maintenance therapy for primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci Trends. 2021;15(3):155–60. doi:10.5582/bst.2021.01091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Connell LC, Kemeny NE. Intraarterial chemotherapy for liver metastases. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2021;30(1):143–58. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2020.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Huang A, Yang XR, Chung WY, Dennison AR, Zhou J. Targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):146. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-00264-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Albiges L, McGregor BA, Heng DYC, Procopio G, de Velasco G, Taguieva-Pioger N, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy in patients with renal cell carcinoma pretreated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2024;122:102652. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2023.102652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhao D, Hou H, Zhang X. Progress in the treatment of solid tumors with apatinib: a systematic review. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:4137–47. doi:10.2147/OTT. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang H. Apatinib for molecular targeted therapy in tumor. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:6075–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

29. Gmeiner WH, Okechukwu CC. Review of 5-FU resistance mechanisms in colorectal cancer: clinical significance of attenuated on-target effects. Cancer Drug Resist. 2023;6(2):257–72. doi:10.20517/cdr. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Blondy S, David V, Verdier M, Mathonnet M, Perraud A, Christou N. 5-Fluorouracil resistance mechanisms in colorectal cancer: from classical pathways to promising processes. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(9):3142–54. doi:10.1111/cas.v111.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Szatmari P, Ducza E. Changes in expression and function of placental and intestinal P-gp and BCRP transporters during pregnancy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(17):13089. doi:10.3390/ijms241713089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Dong J, Yuan L, Hu C, Cheng X, Qin JJ. Strategies to overcome cancer multidrug resistance (MDR) through targeting P-glycoprotein (ABCB1an updated review. Pharmacol Ther. 2023;249:108488. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Isshiki K, Nakao A, Ito M, Hamaguchi M, Takagi H. P-glycoprotein expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1993;52(1):21–5. doi:10.1002/jso.v52:1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao J, Zhang H, Lei T, Liu J, Zhang S, Wu N, et al. Drug resistance gene expression and chemotherapy sensitivity detection in Chinese women with different molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2020;17(4):1014–25. doi:10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2020.0157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Xue F, Xu Y, Song Y, Zhang W, Li R, Zhu X. The effects of sevoflurane on the progression and cisplatinum sensitivity of cervical cancer cells. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:3919–28. doi:10.2147/DDDT. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mi YJ, Liang YJ, Huang HB, Zhao HY, Wu CP, Wang F, et al. Apatinib (YN968D1) reverses multidrug resistance by inhibiting the efflux function of multiple ATP-binding cassette transporters. Cancer Res. 2010;70(20):7981–91. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Hassan A, Badr M, Abdelhamid D, Hassan HA, Abourehab MAS, Abuo-Rahma GEA. Design, synthesis, in vitro antiproliferative evaluation and in silico studies of new VEGFR-2 inhibitors based on 4-piperazinylquinolin-2(1H)-one scaffold. Bioorg Chem. 2022;120:105631. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2022.105631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li L, Jiang AC, Dong P, Wang H, Xu W, Xu C. MDR1/P-gp and VEGF synergistically enhance the invasion of Hep-2 cells with multidrug resistance induced by taxol. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(5):1421–8. doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0395-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Akiyama K, Ohga N, Hida Y, Kawamoto T, Sadamoto Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Tumor endothelial cells acquire drug resistance by MDR1 up-regulation via VEGF signaling in tumor microenvironment. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(3):1283–93. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wu D, Tian S, Zhu W. Modulating multidrug resistance to drug-based antitumor therapies through NF-κB signaling pathway: mechanisms and perspectives. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2023;27(6):503–15. doi:10.1080/14728222.2023.2225767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Feng H, Dong Y, Chen K, You Z, Weng J, Liang P, et al. Sphingomyelin synthase 2 promotes the stemness of breast cancer cells via modulating NF-κB signaling pathway. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150(2):46. doi:10.1007/s00432-023-05589-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang Z, Sun X, Feng Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang Y, et al. Dihydromyricetin reverses MRP2-induced multidrug resistance by preventing NF-κB-Nrf2 signaling in colorectal cancer cell. Phytomedicine. 2021;82:153414. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools