DOI:10.32604/biocell.2022.019591

| BIOCELL DOI:10.32604/biocell.2022.019591 |  |

| Viewpoint |

Production of mesenchymal stem cell derived-secretome as cell-free regenerative therapy and immunomodulation: A biomanufacturing perspective

1Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas 'Aisyiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, 55292, Indonesia

2Department of Bioengineering and Department of Chemical Systems Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, 1138654, Japan

3Department of Physiology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, Warmadewa University, Bali, 80239, Indonesia

*Address correspondence to: Fuad Gandhi Torizal, t_gandhi@unisayogya.ac.id

Received: 30 September 2021; Accepted: 08 December 2021

Abstract: The potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in regenerative medicine has been largely known due to their capability to induce tissue regeneration in vivo with minimum inflammation during implantation. This adult stem cell type exhibit unique features of tissue repair mechanism and immune modulation mediated by their secreted factors, called secretome. Recently, the utilization of secretome as a therapeutic agent provided new insight into cell-free therapy. Nevertheless, a sufficient amount of secretome is necessary to realize their applications for translational medicine which required a proper biomanufacturing process. Several factors related to their production need to be considered to produce a clinical-grade secretome as a biological therapeutic agent. This viewpoint highlights the current challenges and considerations during the biomanufacturing process of MSCs secretome.

Keywords: Secretome; MSCs; Culture system

Abbreviation

| MSCs: | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| CM: | Conditioned medium |

| FBS: | Fetal bovine serum |

| LPS: | Lipopolysaccharides |

| IFNs: | Interferons |

| IL-1β: | Interleukin 1 beta |

| IL-6: | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-7: | Interleukin 7 |

| IL-8: | Interleukin 8 |

| IL-11: | Interleukin 11 |

| IL-12: | Interleukin 12 |

| HGF: | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| TNF-α: | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| TGFβ1: | Transforming growth factor-beta 1 |

| VEGF: | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| BDNF: | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| IGF-1: | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| bFGF: | Basic fibroblast growth factor |

| EGF: | Epidermal growth factor |

| GM-CSF: | granulocyte/monocyte growth factor |

| M-CSF: | Macrophage colony stimulating factor |

| PGE2: | Prostalglandin E2 |

| miR-21: | microRNA-21 |

| miR-210: | microRNA-210 |

| IDO: | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| CXCL5: | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 5 |

The capability of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to differentiate into multiple lineages with less immune rejection makes them become a good candidate for cell-based regenerative therapy. Aside from their applications in cell-based therapy, the study of MSCs secretome as a cell-free therapeutic agent was increased significantly. This secreted compound were natively produced by MSCs to maintain their homeostasis and homing mechanism in vivo. Based on their original function, several studies revealed that the secretome-contained-conditioned media shows therapeutic effects such as immunomodulation and improving tissue regeneration through a similar mechanism with their native function in vivo (Ahangar et al., 2020). Compared to cell-based therapy, the secretome exhibits less immunogenicity because of the absence of immunogenic surface proteins that are expressed in living cells, which much advantageous for translational medicine (Vizoso et al., 2017).

Currently, the importance of regenerative medicine and immunomodulation has even become greater. Since a new variant of coronavirus, entitled severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was identified in late 2019, World Health Organization (WHO) denominated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a global pandemic infection. This disease makes the lower respiratory tract more prone to infection, which results in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome (Anft et al., 2020). Hence, the MSCs secretome introduces a possible cell-free regenerative approach for tissue regeneration and immunomodulation which is urgently needed in this COVID-19 pandemic era.

Composition of MSCs secretome and its therapeutic potential

Secretome consisted of a complex mixture of bioactive compounds that were originally secreted by the cells into the extracellular environment, which are, composed of many factors such as peptides, proteins (including growth factors/cytokines or enzymes), nucleic acid, lipids, metabolites, or extracellular matrix. These biomolecules can be secreted as a free soluble form or contained inside the extracellular vesicle (Beer et al., 2017). The detailed composition of each component was previously described by Tsuji et al. (2018).

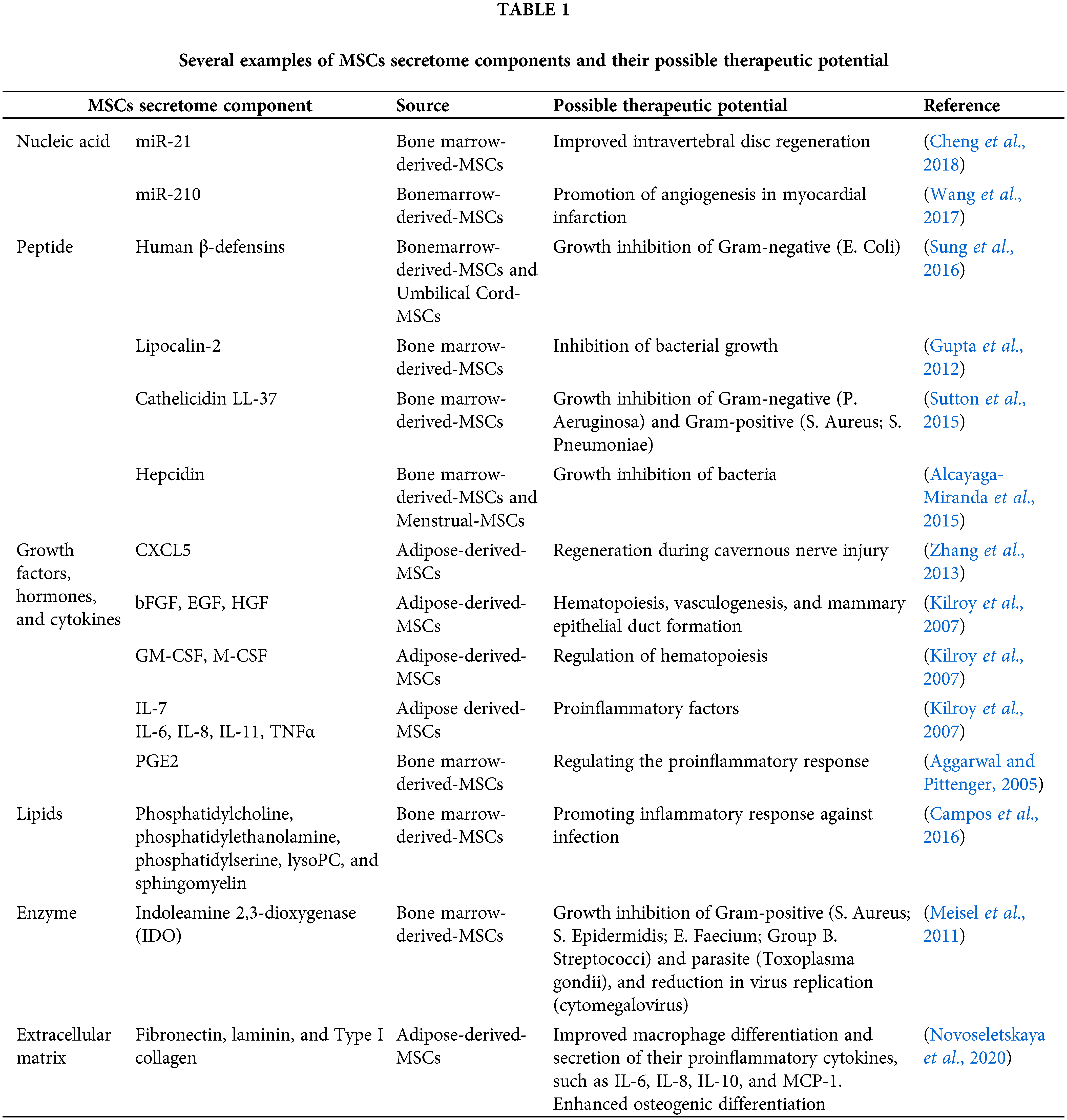

To the best of our knowledge, most of the current studies are concentrated on nucleic acid, peptide, growth factors/hormone/cytokine, enzymes, extracellular matrix, and Lipid components (Table 1). These compounds have been known to contribute to some therapeutic potential, which can be produced by in vitro MSCs culture for possible translational medicine. To date, some trials was performed to assess their effectiveness toward clinical treatment, for example, skin regeneration (Kim et al., 2020) or wound healing (Gugerell et al., 2021; Simader et al., 2017). Recently, a large number of clinical trials for secretome based-immunomodulation and regenerative therapy for COVID19 also has been reported (Chouw et al., 2021). Since the secretome consisted of multiple bioactive components, further in vivo comparison study between administration of manually formulated known bioactive components and MSCs derived-secretome complex. This information may provide additional insight into secretome efficacy in a disease-specific application.

The importance of optimum secretome biomanufacturing process

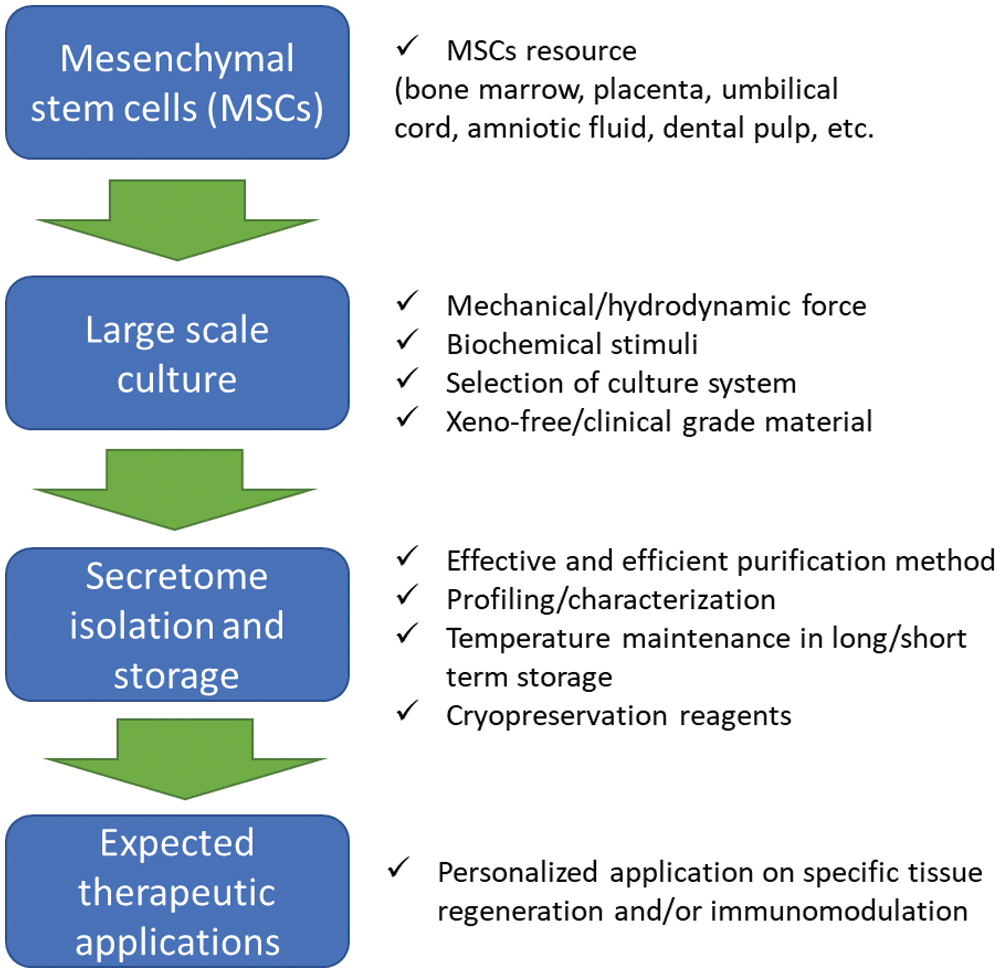

To realize their translational application, an adequate amount and a proper quality of secretome need to be produced for several therapeutic applications through biomanufacturing procedure which needs to be optimized for secretome production (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the MSCs secretome which was produced in vitro consisted of a similar cocktail that regulates various mechanisms as a response to a certain condition in the native tissue environment. Since this condition can be partially mimicked by the culture system, the culture conditions can be modified based on the desired therapeutic effect. A recent proteomic- and bioinformatic- study by Wangler et al. (2021) revealed that the exposure of healthy, traumatic, or degenerative-conditioned medium may stimulate the MSCs to secrete a similar protein complex which contributed to their response in each specific condition in vivo.

Figure 1: Several factors need to be considered to improve secretome production from MSCs.

The secretome variability among different MSCs sources and individual

MSC can be isolated from a wide range of sources including bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, liver, and dental tissues. Although there is a general similarity in composition among MSCs secretome from various resources, the secretome profile and quantity can be varied among the tissue-specific sources, depending on the donor`s physiological condition and their niche of surrounding tissue (Billing et al., 2016). This variability may contribute to their therapeutic effect in clinical applications. Therefore, secretome profiling of donor condition- and tissue-specific MSCs are essentially required to be further evaluated to obtain the general profile of secretome components that potentially play a specific role in tissue regeneration and immunomodulation. For example, a study revealed that there is a different concentration of proangiogenic factors among MSCs secretome derived from different sources, such as human adipose tissue, bone marrow, and umbilical cord Wharton’s jelly (Kehl et al., 2019). Another study showed that the MSCs derived from various patient conditions secreted different amounts of anti-inflammatory factors (Gray et al., 2016).

Selection of culture system for secretome production

Another consideration related to large-scale biomanufacturing needs to be carefully considered in the selection of the culture system. For this purpose, the three-dimensional (3D) suspension culture system is much preferred over conventional monolayer (2D) culture. This system may eliminate the necessity of growth surface which may be limiting the scalability. Additionally, the 3D tissue-like formation can provide better cell-cell interaction which resulted in a significantly higher secretome production (Kim et al., 2020; Miranda et al., 2019).

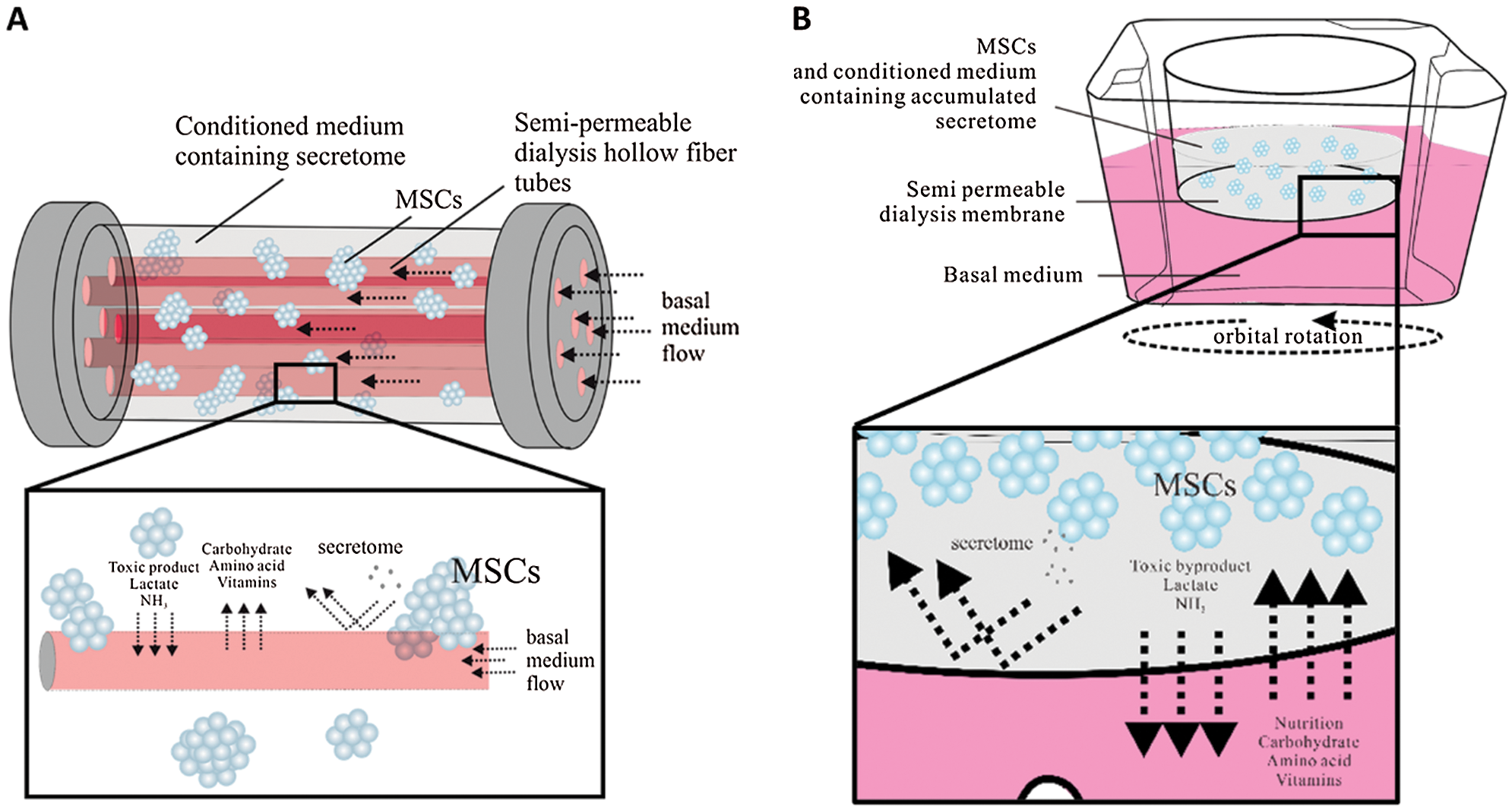

Several culture systems was commonly applied to scale up the MSCs, such as Spinner flask, stirred tank bioreactor, vertical wheel bioreactor, or roller bottle. Each culture system exhibits different designs and operations that may impact the released secretome profile (Hassan et al., 2020). One of the potential biomanufacturing approaches to improving the quality and cost-effectiveness is by using dialysis culture technologies, such as hollow fiber (Barckhausen et al., 2016) or simple dialysis culture by modified culture insert with 4–12 kDa molecular weight cutoff dialysis membrane on the bottom side (Torizal et al., 2021). This culture system enables the localization and accumulation of high molecular weight secretome components, such as the one that enveloped by extracellular vesicle or as complex soluble proteins while continuously refining the small molecule nutrition in the basal media by continuous removal of waste metabolic byproducts, such as lactate and NH3 (Fig. 2), and supplying the nutrition from the culture medium (Torizal et al., 2021). In addition, this system also enables a cost-effective high-density culture that not only saves the exogenous synthetic growth factors usage but also accumulated and concentrates the secretome in a certain compartment, making it easier to isolate and characterize (Barckhausen et al., 2016; Torizal et al., 2021).

Figure 2: Suggested dialysis-based-culture system for MSCs secretome production: (A) Hollow fiber bioreactor and (B) simple dialysis culture system.

Effects of the hydrodynamic condition of culture systems on the release of regenerative- and immunomodulatory factors

The spheroid suspension culture enables a higher density culture which significantly enhanced cell production per volume unit than the monolayer culture. Their tissue-like-three-dimensional structure provides more physiologically relevant conditions which support a better production of their regenerative- and immunomodulation cytokine (Cesarz and Tamama, 2016).

To improve the oxygenation and proper mixing of the medium, a dynamic scalable culture system such as a spinner flask can be employed to proliferate the MSCs to produce a larger amount of secretome. Although the excess hydrodynamic stress can induce cell death, the proper amount of these hydrodynamic stimuli has been known to improve the release of specific cytokine composition related to their differentiation, tissue regeneration, and immunomodulation.

The previous study was revealed that the exposure of hydrodynamic force from MSCs spheroid expanded in suspension using bioreactor was significantly enhanced the production of BDNF, VEGF, and IGF-1, which is an important component to induce regeneration in various tissue (Marques et al., 2018).

Generating expected secretome composition by biochemical stimulation

Naturally, MSCs produce cytokine factors that modulate inflammation and regeneration as the response to certain stimuli that occurred in the tissue. In in vitro conditions, the profile of secretome components may be adjusted by mimicking this in vivo condition (Merino-González et al., 2016). Several studies have shown that expanded MSCs in in vivo like-hypoxic conditions can significantly enhance the proliferation and production of autocrine factors (Paquet et al., 2015; Teixeira et al., 2015). The low oxygen concentration caused by ischemic-like conditions through the addition of H2O2 has been known as an induction method to increase the secretion of proangiogenic factors that can be useful during tissue regeneration, such as HGF and VEGF (Bai et al., 2018). Another example is the addition of immunogenic substances such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) that may induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, IFNs, IL-12, and TNF-α altogether with regeneration factor HGF and VEGF (Lee et al., 2015; Ti et al., 2015); while the inclusion of IFN-γ and TNF-α in culture media has shown to increase the release of cytokines complex that regulate anti-inflammatory factors and bone regeneration (Lu et al., 2017; Sivanathan et al., 2014).

The necessity of xeno-free materials for clinical-grade secretome production

Since the MSCs secretome would be applied for human therapy, the usage of animal-derived (xenogeneic) material needs to be avoided. For example, the fetal bovine serum (FBS) may contain non-human allergenic proteins or unknown transmittable pathogenic substances (Panchalingam et al., 2015; Versteegen, 2016). In addition, this serum also consisted of variability in composition which may result in a heterogeneity of batch to batch secretome composition (Pachler et al., 2017).

The development of serum-free media may provide a solution for this problem. Recently, some xeno-free and GMP (good manufacturing practice)-grade media such as human platelet lysates (HPL) and serum-free media/xeno-free FDA-approved culture medium (SFM/XF) was generally showed similar performance of secretome components compared to FBS-based medium (Guiotto et al., 2020; Oikonomopoulos et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the HPL based-medium formulation showed a lower production of immunosuppressive-related cytokine compared to the FBS-based medium which possibly correlated with a complex pathway inhibition induced by the HPL supplementation component that still needs to be investigated (Oikonomopoulos et al., 2015).

MSCs secretome isolation method and storage

The usage of high-abundance serum protein such as Albumin from supplemented FBS was often mask the lower-abundance secretome, both in free form and in extracellular vesicles. Therefore, this component needs to be separated from the conditioned medium (CM) (Stastna and van Eyk, 2012). Centrifugation is the current common method to recover the secretome from the serum protein enriched-medium. However, the centrifugal force resulted from the centrifugation may disrupt the secretome, resulting in low recovery and decreased bioactivity (He et al., 2014; Helwa et al., 2017). Several technologies have been developed to improve the isolation with high purity, such as antibody- or chromatography-based isolation to separate the secretome from the serum protein used in MSCs culture, but these methods require a high-cost operation. High throughput and cost-effective isolation methods need to be developed in the future (Li et al., 2017). Alternatively, the serum free-media as previously described can be used to address this problem.

In general, the isolated secretome can be stored at –20°C–80°C for up to 6 to 7 months (Zhou et al., 2006). Increasing temperatures, such as more than 4°C or 37°C may slowly degrade cytokine or extracellular vesicle as well as its containing components (Yu et al., 2014). The freeze-thaw cycle also needs to be minimized to preserve the structure and function of the secretome components. In order to reduce the degradation and preserve the proteins component, the aid by protease inhibitor is strongly suggested (Zhou et al., 2006).

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

MSCs secretome holds a therapeutic potential to improve tissue regeneration and modulates the immune response in vivo. However, several challenges need to be addressed to ensure the efficacy of their translational applications. First, the accurate secretome characterization based on the MSCs' source and culture condition needs to be analyzed to obtain their general profile. Based on the profiling pattern, the specific resource can be selected to obtain the expected secretome composition. Secondly, further study needs to be performed to explore possible adjustment of the culture environment or induction that may direct the release of a specific composition of the secretome. The specific induction can be tailored to produce a secretome composition that can be specifically targeted for personalized regenerative- of disease-specific therapeutic effect; and finally, the improvement and standardized methods for secretome biomanufacturing, including large-scale culture systems, isolation, and storage is necessary to realize a safe, potent clinical grade cell-free therapy.

Authors’ Contribution: FGT, FFAK, and AK contributed to manuscript writing, revision, and approved submission.

Funding Statement: This study is supported by Universitas Aisyiyah Yogyakarta as a part of the Collaborative Biotechnology Research Advancement Project 2021.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF (2005). Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood 105: 1815–1822. DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ahangar P, Mills SJ, Cowin AJ (2020). Mesenchymal stem cell secretome as an emerging cell-free alternative for improving wound repair. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21: 1–15. DOI 10.3390/ijms21197038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Alcayaga-Miranda F, Cuenca J, Martin A, Contreras L, Figueroa FE et al. (2015). Combination therapy of menstrual derived mesenchymal stem cells and antibiotics ameliorates survival in sepsis. Stem Cell Research and Therapy 6: 1–13. DOI 10.1186/s13287-015-0192-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Anft M, Paniskaki K, Blazquez-Navarro A, Doevelaar A, Seibert FS et al. (2020). COVID-19-Induced ARDS is associated with decreased frequency of activated memory/effector T cells expressing CD11a++. Molecular Therapy 28: 2691–2702. DOI 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bai Y, Han YD, Yan XL, Ren J, Zeng Q et al. (2018). Adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes stimulated by hydrogen peroxide enhanced skin flap recovery in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 500: 310–317. DOI 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Barckhausen C, Rice B, Baila S, Sensebé L, Schrezenmeier H et al. 2016. NGMP-compliant expansion of clinical-grade human mesenchymal stromal/stem cells using a closed hollow fiber bioreactor. In: Gnecchi M (ed.Methods in Molecular Biology, pp. 389–412. Springer New York. [Google Scholar]

Beer L, Mildner M, Ankersmit HJ (2017). Cell secretome based drug substances in regenerative medicine: When regulatory affairs meet basic science. Annals of Translational Medicine 5: 5–7. DOI 10.21037/atm.2017.03.50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Billing AM, Ben Hamidane H, Dib SS, Cotton RJ, Bhagwat AM et al. (2016). Comprehensive transcriptomic and proteomic characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells reveals source specific cellular markers. Scientific Reports 6: 1–15. DOI 10.1038/srep21507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Campos AM, Maciel E, Moreira ASP, Sousa B, Melo T et al. (2016). Lipidomics of mesenchymal stromal cells: Understanding the adaptation of phospholipid profile in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines. Journal of Cellular Physiology 231: 1024–1032. DOI 10.1002/jcp.25191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cesarz Z, Tamama K (2016). Spheroid culture of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells International. London. UK. DOI 10.1155/2016/9176357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cheng X, Zhang G, Zhang L, Hu Y, Zhang K et al. (2018). Mesenchymal stem cells deliver exogenous miR-21 via exosomes to inhibit nucleus pulposus cell apoptosis and reduce intervertebral disc degeneration. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 22: 261–276. DOI 10.1111/jcmm.13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chouw A, Milanda T, Sartika CR, Kirana MN, Halim D et al. (2021). Potency of mesenchymal stem cell and its secretome in treating COVID-19. Regenerative Engineering and Translational Medicine 395: 565. DOI 10.1007/s40883-021-00202-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gray A, Schloss RS, Yarmush M (2016). Donor variability among anti-inflammatory pre-activated mesenchymal stromal cells. Technology 4: 201–215. DOI 10.1142/S2339547816500084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gugerell A, Gouya-Lechner G, Hofbauer H, Laggner M, Trautinger F et al. (2021). Safety and clinical efficacy of the secretome of stressed peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with diabetic foot ulcer—study protocol of the randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter, international phase II clinical trial MARSYA. Trials 22: 1–11. DOI 10.1186/s13063-020-04948-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guiotto M, Raffoul W, Hart AM, Riehle MO, di Summa PG (2020). Human platelet lysate to substitute fetal bovine serum in hMSC expansion for translational applications: A systematic review. Journal of Translational Medicine 18: 1–14. DOI 10.1186/s12967-020-02489-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gupta N, Krasnodembskaya A, Kapetanaki M, Mouded M, Tan X et al. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells enhance survival and bacterial clearance in murine Escherichia coli pneumonia. Thorax 67: 533–539. DOI 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hassan MNF Bin, Yazid MD, Yunus MHM, Chowdhury SR, Lokanathan Y et al. (2020). Large-scale expansion of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells International 2020: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

He M, Crow J, Roth M, Zeng Y, Godwin AK (2014). Integrated immunoisolation and protein analysis of circulating exosomes using microfluidic technology. Lab on a Chip 14: 3773–3780. DOI 10.1039/C4LC00662C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Helwa I, Cai J, Drewry MD, Zimmerman A, Dinkins MB et al. (2017). A comparative study of serum exosome isolation using differential ultracentrifugation and three commercial reagents. PLoS One 12: 1–22. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0170628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kehl D, Generali M, Mallone A, Heller M, Uldry AC et al. (2019). Proteomic analysis of human mesenchymal stromal cell secretomes: A systematic comparison of the angiogenic potential. npj Regenerative Medicine 4: 824. DOI 10.1038/s41536-019-0070-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kilroy GE, Foster SJ, Wu X, Ruiz J, Sherwood S et al. (2007). Cytokine profile of human adipose-derived stem cells: Expression of angiogenic, hematopoietic, and pro-inflammatory factors. Journal of Cellular Physiology 212: 702–709. DOI 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim KH, Kim YS, Lee S, An S (2020). The effect of three-dimensional cultured adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium and the antiaging effect of cosmetic products containing the medium. Biomedical Dermatology 4: 1–12. DOI 10.1186/s41702-019-0053-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee SCK, Jeong HJ, Lee SCK, Kim SJ (2015). Lipopolysaccharide preconditioning of adipose-derived stem cells improves liver-regenerating activity of the secretome. Stem Cell Research and Therapy 6: 1–11. DOI 10.1186/s13287-015-0072-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li P, Kaslan M, Lee SH, Yao J, Gao Z (2017). Progress in exosome isolation techniques. Theranostics 7: 789–804. DOI 10.7150/thno.18133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu Z, Chen Y, Dunstan C, Roohani-Esfahani S, Zreiqat H (2017). Priming adipose stem cells with tumor necrosis factor-alpha preconditioning potentiates their exosome efficacy for bone regeneration. Tissue Engineering Part A 23: 1212–1220. DOI 10.1089/ten.tea.2016.0548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marques CR, Marote A, Mendes-Pinheiro B, Teixeira FG, Salgado AJ (2018). Cell secretome based approaches in Parkinson’s disease regenerative medicine. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 18: 1235–1245. [Google Scholar]

Meisel R, Brockers S, Heseler K, Degistirici O, Bülle H et al. (2011). Human but not murine multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial effector function mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Leukemia 25: 648–654. DOI 10.1038/leu.2010.310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Merino-González C, Zuñiga FA, Escudero C, Ormazabal V, Reyes C et al. (2016). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote angiogenesis: Potencial clinical application. Frontiers in Physiology 7: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

Miranda JP, Camões SP, Gaspar MM, Rodrigues JS, Carvalheiro M et al. (2019). The secretome derived from 3D-cultured umbilical cord tissue MSCS counteracts manifestations typifying rheumatoid arthritis. Frontiers in Immunology 10: 1–14. DOI 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Novoseletskaya E, Grigorieva O, Nimiritsky P, Basalova N, Eremichev R et al. (2020). Mesenchymal stromal cell-produced components of extracellular matrix potentiate multipotent stem cell response to differentiation stimuli. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 8: 1–25. DOI 10.3389/fcell.2020.555378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Oikonomopoulos A, Van Deen WK, Manansala AR, Lacey PN, Tomakili TA et al. (2015). Optimization of human mesenchymal stem cell manufacturing: The effects of animal/xeno-free media. Scientific Reports 5: 1–11. DOI 10.1038/srep16570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pachler K, Lener T, Streif D, Dunai ZA, Desgeorges A et al. (2017). A good manufacturing practice-grade standard protocol for exclusively human mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Cytotherapy 19: 458–472. DOI 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Panchalingam KM, Jung S, Rosenberg L, Behie LA (2015). Bioprocessing strategies for the large-scale production of human mesenchymal stem cells: A review Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells-An update. Stem Cell Research and Therapy 6: 1–10. DOI 10.1186/s13287-015-0228-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Paquet J, Deschepper M, Moya A, Logeart-Avramoglou D, Boisson-Vidal C et al. (2015). Oxygen tension regulates human mesenchymal stem cell paracrine functions. STEM CELLS Translational Medicine 4: 809–821. DOI 10.5966/sctm.2014-0180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Simader E, Traxler D, Kasiri MM, Hofbauer H, Wolzt M et al. (2017). Safety and tolerability of topically administered autologous, apoptotic PBMC secretome (APOSEC) in dermal wounds: A randomized Phase 1 trial (MARSYAS I). Scientific Reports 7: 1–8. DOI 10.1038/s41598-017-06223-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sivanathan KN, Gronthos S, Rojas-Canales D, Thierry B, Coates PT (2014). Interferon-gamma modification of mesenchymal stem cells: Implications of autologous and allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapy in allotransplantation. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports 10: 351–375. DOI 10.1007/s12015-014-9495-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stastna M, van Eyk JE (2012). Investigating the secretome lessons about the cells that comprise the heart. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics 5: 8–18. [Google Scholar]

Sung DK, Chang YS, Sung SI, Yoo HS, Ahn SY et al. (2016). Antibacterial effect of mesenchymal stem cells against Escherichia coli is mediated by secretion of beta- defensin- 2 via toll- like receptor 4 signalling. Cellular Microbiology 18: 424–436. DOI 10.1111/cmi.12522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sutton MT, Fletcher D, Ghosh SK, Weinberg A, Van Heeckeren, R, Kaur S, Sadeghi Z, Hijaz A, Reese J, Lazarus HM, et al. (2015). Antimicrobial properties of mesenchymal stem cells: Therapeutic potential for cystic fibrosis infection, and treatment. Stem Cells International. DOI 10.1155/2016/5303048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Teixeira FG, Panchalingam KM, Anjo SI, Manadas B, Pereira R et al. (2015). Do hypoxia/normoxia culturing conditions change the neuroregulatory profile of Wharton Jelly mesenchymal stem cell secretome? Stem Cell Research and Therapy 6: 1–14. DOI 10.1186/s13287-015-0124-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ti D, Hao H, Tong C, Liu J, Dong L et al. (2015). LPS-preconditioned mesenchymal stromal cells modify macrophage polarization for resolution of chronic inflammation via exosome-shuttled let-7b. Journal of Translational Medicine 13: 1–14. DOI 10.1186/s12967-015-0642-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Torizal FG, Choi H, Shinohara M, Sakai Y (2021). Efficient high-density hiPSCs expansion in simple dialysis device. In: Methods in Molecular Biology. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Torizal FG, Lau QY, Ibuki M, Kawai Y, Horikawa M et al. (2021). A miniature dialysis-culture device allows high-density human-induced pluripotent stem cells expansion from growth factor accumulation. Communications Biology 4: 1–13. DOI 10.1038/s42003-021-02848-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tsuji K, Kitamura S, Wada J (2018). Secretomes from mesenchymal stem cells against acute kidney injury: Possible heterogeneity. Stem Cells International. London, UK. DOI 10.1155/2018/8693137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Versteegen R (2016). Serum: What, When, and Where? Bioprossesing 15: 18–21. DOI 10.12665/J151.Versteegen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Vizoso FJ, Eiro N, Cid S, Schneider J, Perez-Fernandez R (2017). Mesenchymal stem cell secretome: Toward cell-free therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18: 1852. DOI 10.3390/ijms18091852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang N, Chen C, Yang D, Liao Q, Luo H et al. (2017). Mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles, via miR-210, improve infarcted cardiac function by promotion of angiogenesis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Basis of Disease 1863: 2085–2092. DOI 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.02.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wangler S, Kamali A, Wapp C, Wuertz-Kozak K, Häckel S et al. (2021). Uncovering the secretome of mesenchymal stromal cells exposed to healthy, traumatic, and degenerative intervertebral discs: A proteomic analysis. Stem Cell Research and Therapy 12: 1–17. DOI 10.1186/s13287-020-02062-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yu B, Zhang X, Li X (2014). Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 15: 4142–4157. DOI 10.3390/ijms15034142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang H, Yang R, Wang Z, Lin G, Lue tom F et al. (2013). Adipose tissue-derived stem cells secrete CXCL5 cytokine with neurotrophic effects on cavernous nerve regeneration. Journal of Sexual Medicine 83: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

Zhou H, Yuen PST, Pisitkun T, Gonzales PA, Yasuda H et al. (2006). Collection, storage, preservation, and normalization of human urinary exosomes for biomarker discovery. Kidney International 69: 1471–1476. DOI 10.1038/sj.ki.5000273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |