DOI:10.32604/biocell.2022.018254

| BIOCELL DOI:10.32604/biocell.2022.018254 |  |

| Article |

Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of aluminum-activated malate transporter genes (ALMTs) in Gossypium hirsutum L.

1College of Biotechnology and Food Engineering, Anyang Institute of Technology, Anyang, China

2State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology, Institute of Cotton Research, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Anyang, China

3Engineering Research Centre of Cotton, Ministry of Education/College of Agriculture, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China

*Address correspondence to: Youlu Yuan, yylCRI@126.com

#These authors have contributed equally to this work

Received: 10 June 2021; Accepted: 16 August 2021

Abstract: Aluminum-activated malate transporters (ALMT) are widely involved in plant growth and metabolic processes, including adaptation to acid soils, guard cell regulation, anion homeostasis, and seed development. Although ALMT genes have been identified in Arabidopsis, wheat, barley, and Lotus japonicus, little is known about its presence in Gossypium hirsutum L. In this study, ALMT gene recognition in diploid and tetraploid cotton were done using bioinformatics analysis that examined correlation between homology and evolution. Differentially regulated ALMT genetic profile in G. hirsutum was examined, using RNA sequencing and qRT-PCR, during six fiber developmental time-points, namely 5 d, 7 d, 10 d, 15 d, 20 d, and 25 d. We detected 36 ALMT genes in G. hirsutum, which were subsequently annotated and divided into seven sub-categories. Among these ALMT genes, 34 had uneven distribution across 14/26 chromosomes. Conserved domains and gene structure analysis indicated that ALMT genes were highly conserved and composed of exons and introns. The GhALMT gene expression profile at different DPA (days post anthesis) in different varieties of G. hirsutum is indicative of a crucial role of ALMT genes in fiber development in G. hirsutum. This study provides basis for advancements in the cloning and functional enhancements of ALMT genes in enhancing fiber development and augmenting high quality crop production.

Keywords: Gossypium hirsutum; Aluminum-activated malate transporters (ALMT); Genome wide analysis; Fiber development; Expression pattern

The plant genome has frequent repetitions of the aluminum-activated malate transporters (ALMT) genes, which is essential for transporting organic acids (OAs) across membranes (Zhang et al., 2014). OAs regulate plant metabolism and modulate adaptational (Sharma et al., 2016) activities like stomatal motion (Meyer et al., 2010a; Meyer et al., 2010b; Sasaki et al., 2010), aluminum tolerance, pH modulation, and stress response (Sharma et al., 2016). In the last few decades, multiple reports have suggested that the release of OAs (particularly, malic acid) can modulate plant tolerance to metal, while its improvs nutritional stress, ion transport, and cell turgor pressure (Meyer et al., 2010b; Sasaki et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). Therefore, delineating the underlying mechanism of ALMTs action can provide us with tools to improve plant response to biotic and abiotic stressors.

Evolutionary analysis of ALMTs in bacteria (Takanashi et al., 2016), Arabidopsis (Kovermann et al., 2007), rice (Oryza sativa) (Liu et al., 2017), apple (Ma et al., 2018), and Chinese white pear (Xu et al., 2018) demonstrated that plants ALMTs have distinctive function, for example aluminum tolerance, and fruit acidity in plants. They have also been correlated with resistance response, ion transport, and opening and closing of the stomatal guard cells.

Based on a study on Arabidopsis thaliana, the ALMT family has 14 members, divided into three subgroups, according to their functions. The most representative family member is AtALMT1, which belongs to the first subgroup and is located in the root cell membrane. AtALMT9 represents member of the second subgroup and is primarily expressed in mesophyll cells. AtALMT12 belongs to the third subcategory and is primarily expressed in the plasma membrane and the intima of guard cells. Its function is related to the closure of guard cell type anion channels and stomata (Meyer et al., 2010b; Sasaki et al., 2010).

ALMTs were reported to function as anion channel proteins (Zhang et al., 2014). In particular, the activity and expression profile of the AtALMT12 gene was shown to have significant influence on the anion efflux. In stomatal guard cells, under drought stress, the gene was shown to accelerate guard cell cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, and vacuole anion discharge. A massive exudation of anions altered cell membrane polarity, activated K+ channel proteins, and resulted in the release of K+ out of cells, causing reduction in cell turgor pressure, closure of the stomata and minimization of moisture loss.

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) is a highly profitable crop and the largest source of natural fiber for the global textile industry. The demand for enhanced fiber quality is increasing with the rapid growth of modern textile industries. Till now, little is known about the role of the ALMT gene family in upland cotton. Here, we screened the entire genome of the upland cotton ALMT gene family and predicted gene structure, chromosome distribution, cellular localization, and expression pattern. This work will offer new insight into the development of genetically enhanced stress-resistant cotton fiber.

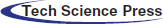

Recognition of ALMT genes in the G. hirsutum genome

We detected 36 ALMT genes in the G. hirsutum genome (Table 1). Using physiochemical analysis, we also identified ALMT genes features, like amino acid sequence lengths, isoelectric point (pI), molecular weight (MW), genomic location, subcellular localizations (Table 1). Utilizing CELLO v.2.5 and WoLF PSORT servers, we analyzed cellular localizations of ALMT proteins. Based on our analysis, 16 ALMT proteins were estimated to be cytoplasmic, 10 outer membranal, and the remaining were inner membranal (Table 1).

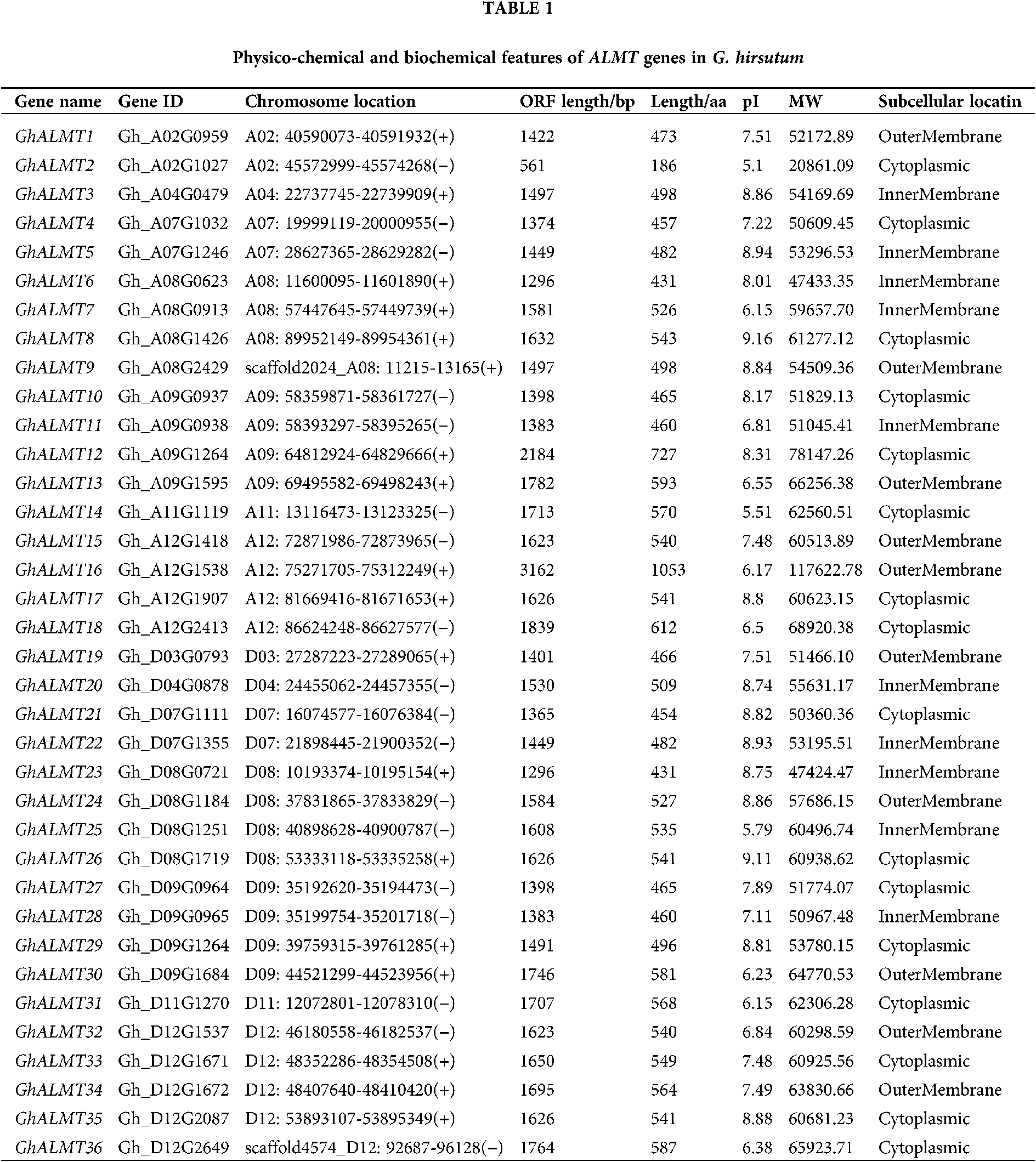

Phylogenetic analysis of ALMTs in G. hirsutum

To elucidate the ALMTs-mediated phylogenetic interactions between G. hirsutum and other plants, we aligned the recognized ALMT protein sequences to generate an unrooted phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1).

Based on the amino acid sequence homology, the 36 recognized ALMT members can be classified into five distinct clades. Clade A included GhALMT3, 4, 10, 11, 12, 20, 21, 27, 28, and 29. Clade B included GhALMT1, 5, 9, 19, 22, and 24. Clade C included GhALMT8, 17, 26, and 35. Clade D included GhALMT6, 14, 23, and 31. Clade E included GhALMT13, 18, 30, and 36. Clade F included GhALMT15, 16, 32, 33, and 34. Lastly, Clade G included GhALMT2, 7, and 25.

Figure 1: ALMT genes phylogenetic tree, created using genomes of several plant species, with 7 sub-categories (A, B, C, D, E, F and G), depending on high bootstrap values.

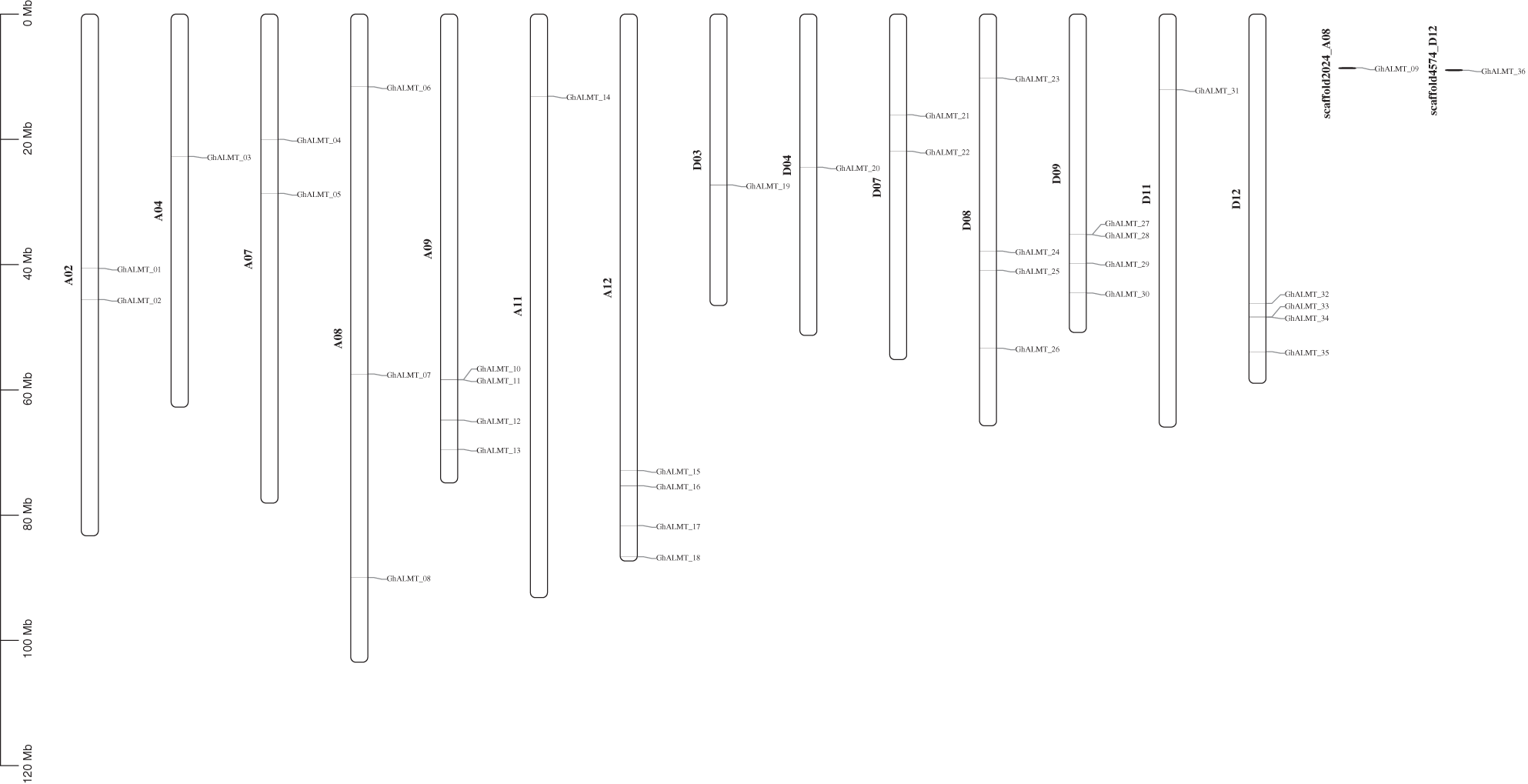

Gene positioning and syntenic analysis

We first identified GhALMT gene positioning within chromosomes, then generated gene maps of relevant chromosomes (Fig. 2). Based on our analysis, 14/26 chromosomes contained GhALMT genes. Among them, five chromosomes, namely, A4, A11, D3, D4, and D11, carried one GhALMT gene. three chromosomes, namely A2, A7, and D7, contained two copies of the GhALMT gene. chromosomes of A8 contained three copies of the GhALMT gene. five chromosomes, namely, A9, A12, D8, D9 and D12 contained four copies of the GhALMT gene.

Figure 2: Physical map of ALMT genes in G. hirsutum. GhALMT genes were plotted onto 14 chromosomes of G. hirsutum. The scale represents mega bases (Mb). Chromosome numbers are identified below each chromosome. The numbers to the right represent GhALMT gene positioning, and names of respective genes are provided on the left.

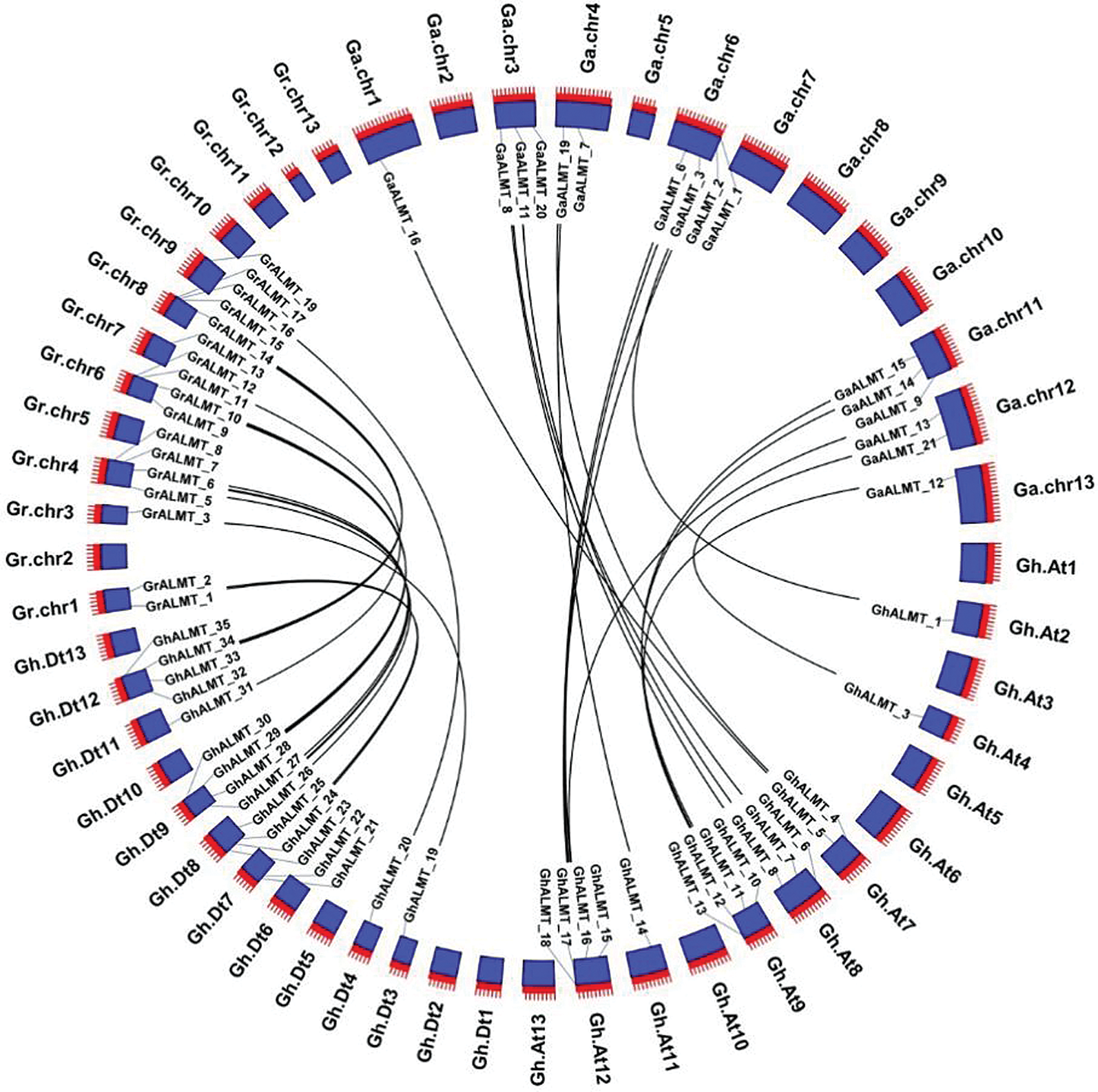

Comparison of ALMT gene family members, among the cotton genomes of G. raimondii, G. arboretum, and G. hirsutum were done with BlastP. Gene sequence homology was identified with MCScanX (Kumar et al., 2018) and visualized with CirCos (Krzywinski et al., 2009). We discovered 16 ALMT homologous pairs in G. arboreum and G. hirsutum. In the G. hirsutum species, the homologous genes could be found in A01 (one pair), A03 (three pairs), A04 (two pairs), A06 (four pairs), A11 (three pairs), A12 (two pairs), and A13 (one pair). Additionally, 17 ALMT homologous pairs were identified between G. raimondii and G. hirsutum. In G. hirsutum, these genes were in location D01 (two pairs), D03 (one pair), D04 (four pairs), D06 (four pairs), D07 (one pair), D08 (four pairs), and D09 (one pair). The collinear interactions among G. raimondii, G. arboretum, and G. hirsutum are illustrated in (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Evaluation of syntenic interactions among ALMT genes belonging to G. hirsutum, G. raimondii, and G. arboretum.

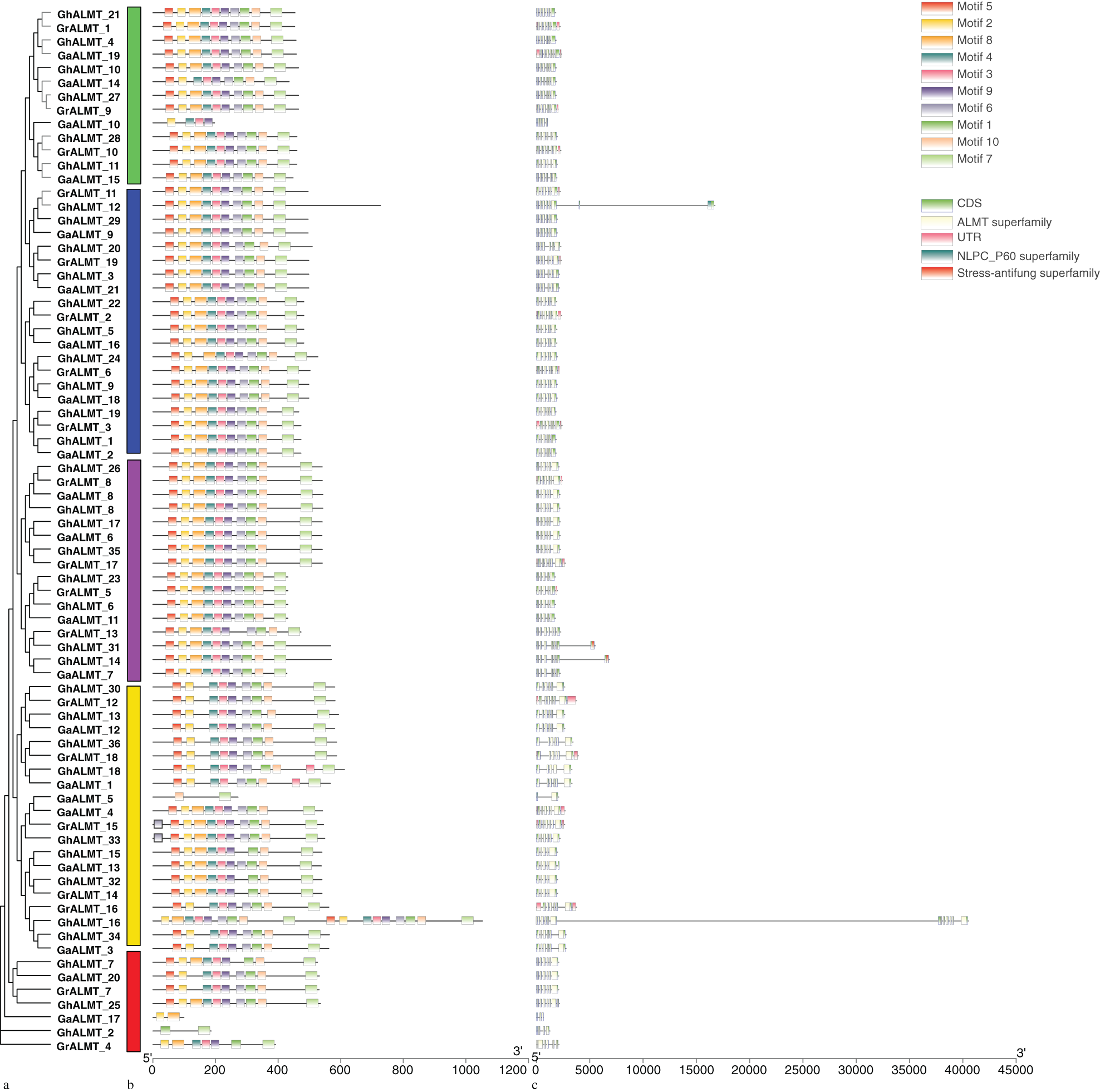

Conserved patterns, genetic structures, and clustering analysis of ALMTs in G. hirsutum

In order to delineate pattern compositions and phylogenetic interactions of GhALMTs, we constructed an unrooted phylogenetic tree, with 10 conserved patterns, recognized by MEME. GhALMTs were clustered into five major clades. The same subfamily was observed with common patterns.

Structural analysis of the GhALMT genes was conducted with the GSDS server. The CDS lengths and intron quantity of GhALMT genes remained within 561 to 3162 bp and 3 to 11, respectively (Fig. 4). GhALMT16 had the most introns, whereas GhALMT2 only had 3 introns. GhALMT14, GhALMT25, and GhALMT31 possessed 6 introns; GhALMT6, GhALMT15, GhALMT18, GhALMT23, GhALMT24, and GhALMT32 possessed 4 introns. The remainder of the 24 GhALMT genes possessed 5 introns each.

Figure 4: Phylogenetic tree, genetic structure, and conserved pattern analyses of aluminum-activated malate transporters (ALMT) in Gossypium hirsutum. (a) Phylogenetic tree of G. hirsutum ALMTs generated with MEGA 6.0 using the maximum likelihood formula. (b) The conserved motifs of GhALMT gene family are shown on the middle of the figure. Different motif types are indicated with a specific color. (c) Exon–intron structures of GhALMT genes.

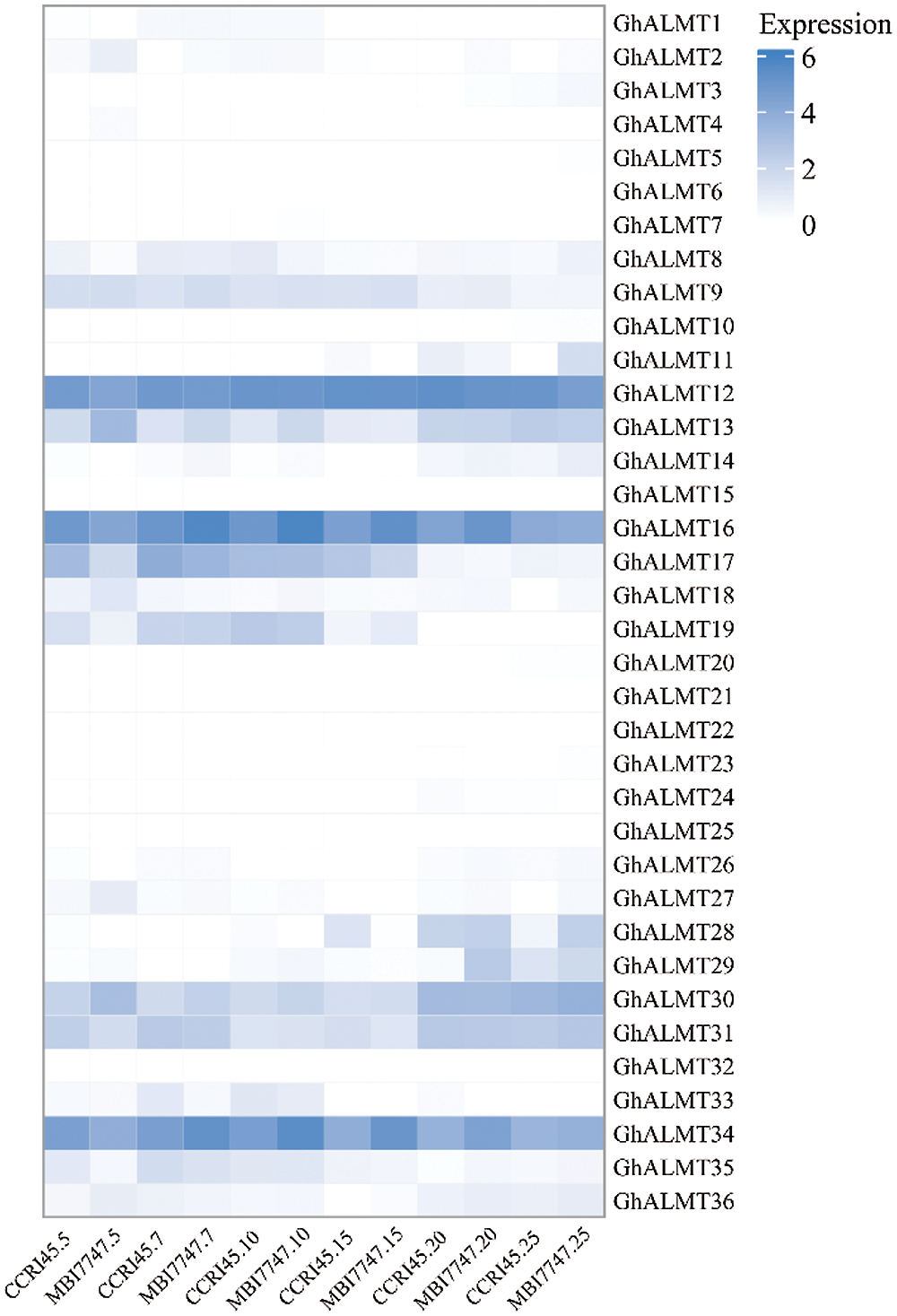

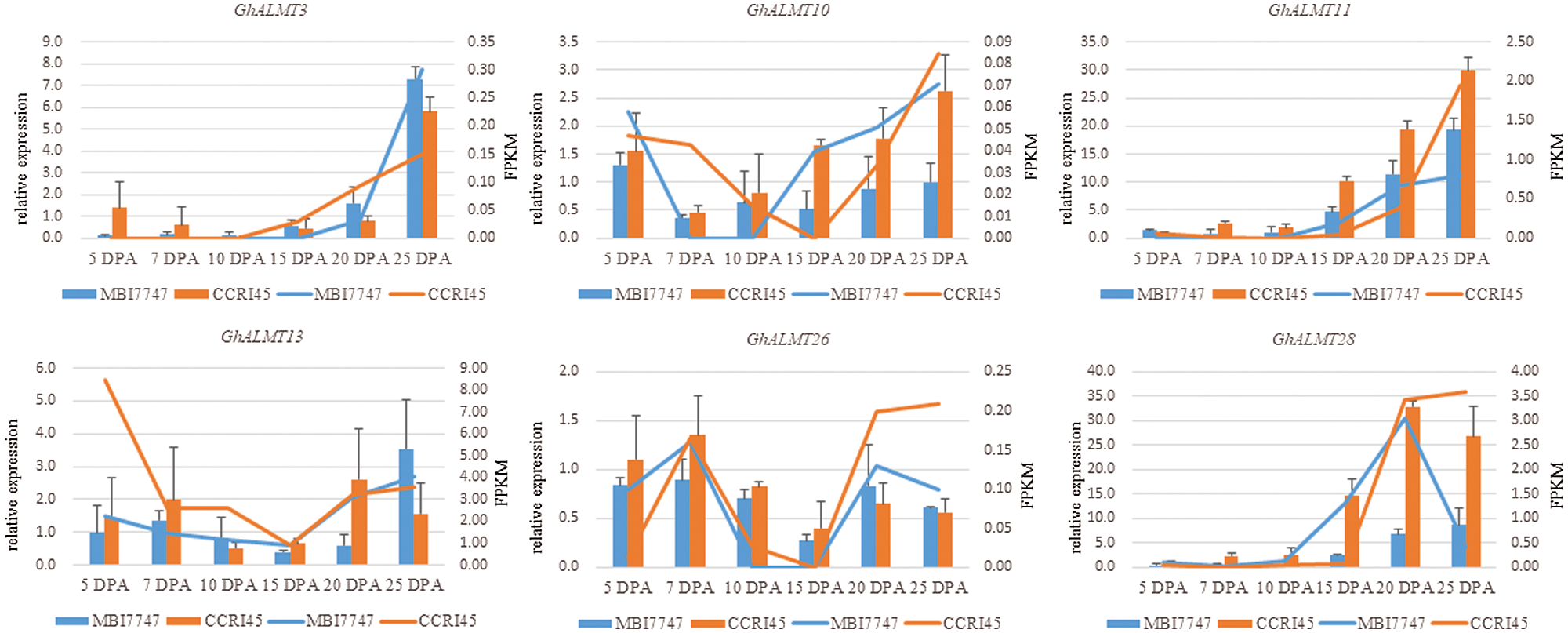

Expression profiles of ALMTs in G. hirsutum during different periods of fiber development

To examine the expression profiles of the ALMT gene family in G. hirsutum during fiber development, we analyzed the expression profiles of 36 genes within 7 developmental time-points, namely, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, and 25 d, from the transcriptome information we received from the laboratory (Fig. 5). Using heatmap, we showed various ALMT family genes exhibited the same expression profile.

Figure 5: Relative levels of cotton ALMT genes from the fiber transcriptome information generated in the laboratory. The robust multi-array average (RMA)-normalized, average log2 signal values of upland cotton ALMTs in fiber developmental phases (described on top of the heat map) were employed to generate the heat map. The hierarchical clustering conclusions were obtained from Pearson correlation analysis and are presented at the top left corner of the heat map.

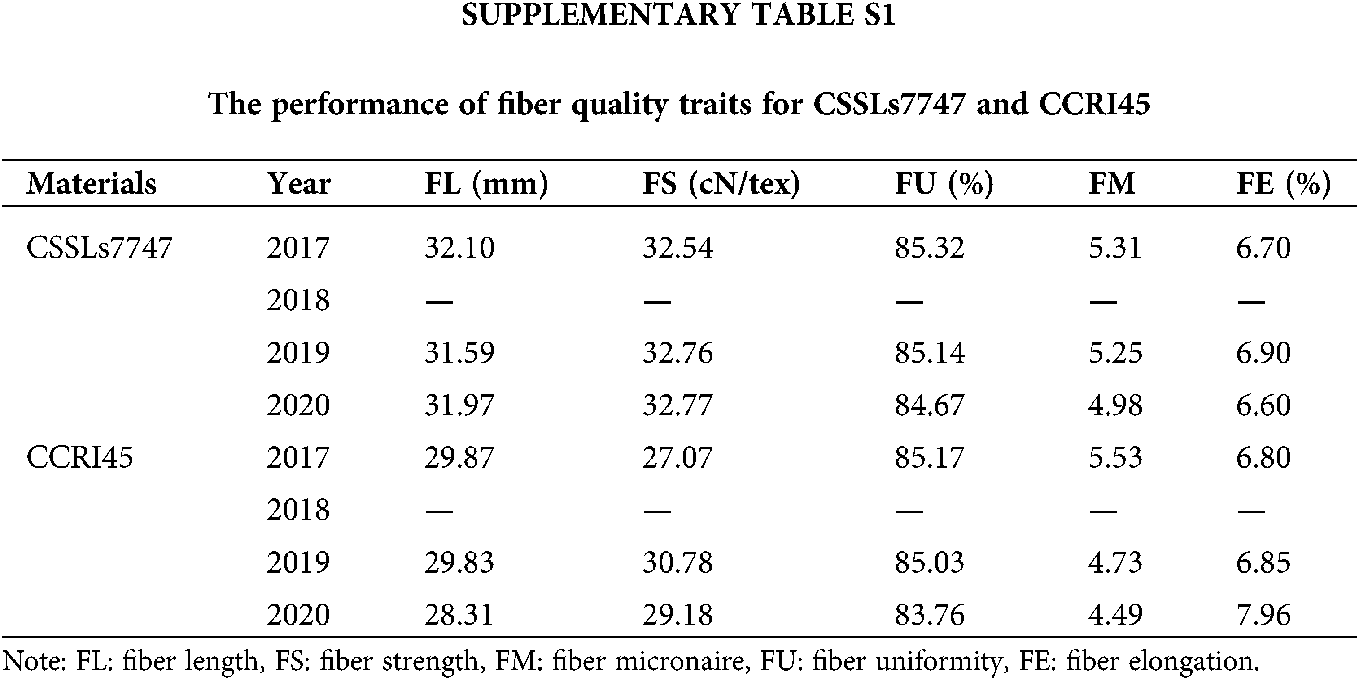

Furthermore, we random-validated the expression profile divergence of ALMT genes among the two G. hirsutum species, using qRT-PCR. Our conclusions from RNA-seq analysis were in accordance with our qRT-PCR data (Fig. 6), suggesting reliability and accuracy of both forms of analysis. The expression of selected ALMT genes in CSSLs7747 with good fiber quality was lower than CCRI45 with poor fiber quality, indicating fiber developmental regulation by GhALMTs genes. The performance of fiber quality traits for CSSLs7747 and CCRI45 are presented in Suppl. Table S1. The low expression and poor activity of ALMT in CSSLs7747 likely leads to a slower rate of ion outflow and a higher cell bound pressure than CCRI45. Thus, results in a higher elongation rate of CSSLs7747 fibrocytes, compared to CCRI45. Based on this evidence, we confirmed the reliability and accuracy of these procedures, and highlighted the potential roles of GhALMTs genes in fiber production.

Figure 6: RNA-seq data confirmation using qRT-PCR. Relative transcript levels of each gene compared to the gene of CCRI45’s 5 DPA fiber.

Emerging reports on the functional properties of plant ALMTs suggest an essential involvement of this gene in plant growth, development, regulation of metal tolerance, ion transport, and cell turgor pressure. Hence ALMTs participates in interaction with the environment alongside xenobiotics detoxification, biosynthesis, storage, and secondary metabolites transport. Despite extensive analysis of multigene families of multiple plant genomes, little is known about the function of ALMTs in G. hirsutum. The ALMTs gene family has been recognized and studies in many plant species, namely, nodules of lotus japonicas (Takanashi et al., 2016), Arabidopsis (Kovermann et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2016), rice (Liu et al., 2017), and fruit species such as apples (Ma et al., 2018), Chinese white pear (Xu et al., 2018), and vegetables tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (Sasaki et al., 2016).

A recent publication, involving sequencing and optical mapping of the cotton genome, facilitated the identification of the GhALMT gene family. Hence, we established 36 ALMTs in the upland cotton, which is similar to the quantity found in Arabidopsis, rice, flax, and various fruit species.

A phylogenetic tree provides a framework for the comparison of characteristics of multiple genetic family members (Jung et al., 2008). In this present study, G. raimondii (19), G. arboreum (21), Arabidopsis (14), Glycine max (52), Oryza sativa (12), Populus (29), and Therobroma cacao (15), Eucalyptus robusta Smith (20) were chosen for phylogenetic analysis. The genes of these species are all homologous and use these genes to better cluster similar genes in G. hirsutum (Xiao et al., 2019). Here, 36 ALMT genes in G. hirsutum were grouped into 7 sub-categories, according to their phylogenetic properties. Similarly, in apples, the ALMT gene family was also sub-divided into 7 sub-categories (Ma et al., 2018). However, in Chinese white pear (Xu et al., 2018), the ALMT gene family classification found 10 sub-categories, with 3 major classes. This classification disparity may have resulted from the usage of different gene identification techniques. To further delineate the ALMTs evolution within the phylogenetic group, we examined the positions, patterns, structure, and expression profile of these genes. We also performed intron mapping, based on the 36 upland cotton ALMTs. To this end, we performed expression analysis of the ALMT using transcriptome sequencing data and RT-qPCR. The transcriptome experimental materials in the early stage of the experiment were as follows CCRI45 and CSSLs7747, to match transcriptome data from different period of the fiber, wo choose the CCRI45 and CSSLs7747 variety for qRT-PCR analysis. In addition, CSSLs7747 has better fiber quality than CCRI45. So, we can use transcriptome and qRT-PCR results to determine whether these genes are related to the fiber quality of cotton.

Being part of the anion channel in Arabidopsis thaliana, AtALMT12 expression profile and activity greatly influences anion efflux. Under drought stress, AtALMT12, in the stomatal guard cells, can accelerate anion discharge from the cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, and fluid cells. A massive outflow of anions can cause the cell membrane to lose polarity, thereby activating the outward K+ channel, and result in a mass exodus of K+ ions from the cell, leading to reduced cell turgor pressure, closure of stomata, and minimization of water loss (Zhang et al., 2014).

Multiple evidence also suggest that the development and elongation of fibers also have close association with cell turgor pressure. Prior studies found that the anion discharge from the cytoplasm can be induced, under special environmental conditions, this induction can facilitate polarity decrease within the membrane and vacuole, this activate the outward K+ channel, and, resulting in allow the discharge of a large amount of cations from cells, This is subsequently followed by reduced cell turgor and decreased speed of cell elongation (Gokani et al., 1998; Meinert and Delmer, 1977; Qin and Zhu, 2011). Aluminum-activated malate transporter (GbALMT16) genes whose expression was detected in the tonoplast of Hai7124 fibers, which had a longer period of expression than the homologous genes in TM-1. These transporters pump more K+ and malate into the vacuole. And a relatively extended time period could be impact on the accumulation of more K+ and malate, thereby leading to production of longer fibers in ELS cotton (Hu et al., 2019).

Shortly following initiation of fiber differentiation, vacuoles form and eventually fill plant cells (Ruan et al., 2001). During the elongation period, soluble sugar, malic acid, and potassium salt gradually enrich the vacuoles, thereby generating osmotic pressure within the vacuoles. This osmotic pressure facilitates the gradual elongation of the fiber cells (Basra and Malik, 1984). Fiber elongation can be divided into two stages: nonpolar elongation and polar elongation. The fiber cell spreads out in all directions during the nonpolar elongation stage (0 DPA–10 DPA). However, during the polar elongation phase (10 DPA–15 DPA), K+ and malic acid within vacuoles are transported against the concentration gradient to the vacuole thereby increasing intracellular K+ and malic acid concentration in the vacuole. As mentioned previously, this generates osmotic pressure which elongates the fiber cells (Wilkins et al., 1994). Alternately, under conditions when the concentration of K+ and malate are lowered, the growth rate of fiber decreases gradually. During this time, the H+-ATPase system provides energy for the active transport, and the plasmodesmata remains closed, thereby rapidly increasing osmotic potential and turgor in the fiber cells to allow for the rapid elongation of fiber cells (Ruan et al., 2001). Given this evidence, we can conclude that the GhALMT gene family is essential to the cotton fiber elongation process.

Here, we established 36 ALMTs genes in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and grouped them into seven sub-categories, according to their high bootstrap values. Next, we extensively analyzed the ALMTs gene profile in cotton (G. hirsutum), especially focusing on domains, gene structure, chromosome distribution, and collinearity. Moreover, we also explored the ALMTs evolutionary interaction in G. hirsutum, G. raimondii, G. arboreum, Therobroma cacao, Arabidopsis, and other plants species. We conducted qRT-PCR validation showing that GhALMT10, 11, and 28 are markedly upregulated during fiber development, suggesting a strong role in the process. Our research will provide novel insight into the role of ALMTs in cotton production.

Recognition of ALMT genes in G. hirsutum and generation of phylogenetic tree

To recognize the ALMT gene family members within the plant species G. hirsutum, G. raimondii, G. arboreum, Theobroma cacao, Arabidopsis and so on, ALMT sequences were retrieved from the cotton database (https://www.cottongen.org/), the TAIR database (http://www.arabidopsis.org) or the Ensembl Plants database (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html) and subjected to a BLASTP search against the G. hirsutum genome database available at https://www.cottongen.org/species/Gossypium_hirsutum/nbi-AD1_genome_v1.1 (Zhang et al., 2015). The ALMT protein domain was examined with the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/). The ALMT domains were further verified with the Pfam accession number pfam11744 and the sequences were aligned with the MAFFT sequence alignment software (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/mafft/), using default criteria settings. The results of this analysis were then retrieved with the Gblock (http://molevol.cmima.csic.es/castresana/Gblocks_server.html) and it identified the conservative areas. Next, we adjusted the criteria to allow for smaller final regions, strict flank sites and a vacancy in the final area. Finally, to generate the phylogenetic tree, the conserved ALMT sequences were imported to PhyML 3.0 (http://phylogeny.lirmm.fr/, LIRMM laboratory (CNRS-LIRMM)) (Xiao et al., 2019). The probability ration was done with the SH-like formula and the LG model was employed for the substitution model. The constructed phylogenetic tree is available for viewing by MEGA7.0 and iTOL V4 (http://itol.embl.de/).

Evaluation of the exon/intron pattern, cellular localization, and chromosomal location of ALMT genes in G. hirsutum

The GFF annotation file of G. hirsutum was retrieved with the gene structure display server (GSDS) program (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) (Guo et al., 2007) to obtain the exon/intron pattern of the ALMT genes.

GhALMTs conserved motifs were identified with the help of MEME (http://meme-suite.org/) (Bailey et al., 2009), using criteria listed below: a pattern width of 6–50 amino acids and a maximum of 10 patterns. The recognized patterns were then annotated with InterProScan (Quevillon et al., 2005).

The WoLF PSORT: Protein Subcellular Localization Prediction (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) was used to predict ALMT proteins cellular localization.

The G. hirsutum genome annotation results provided the chromosomal distribution of ALMT genes, which were plotted with MapInspect software (Ren et al., 2017).

ALMT family gene expression was assessed with RNA-sequencing. Raw CCRI45 RNA-sequencing data and fiber transcriptome information from superb fiber quality CSSLs (CSSLs7747) were retrieved from the laboratory, covering six developmental time-points, namely 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, and 25 days (d) (Lu et al., 2017). And the RNA-seq data download form SRA: PRJNA506494. The retrieved data was normalized to reveal the relative levels of ALMT family genes. This was next subjected to hierarchical clustering with Genesis 1.7.7 (Pertea et al., 2016; Sturn et al., 2002).

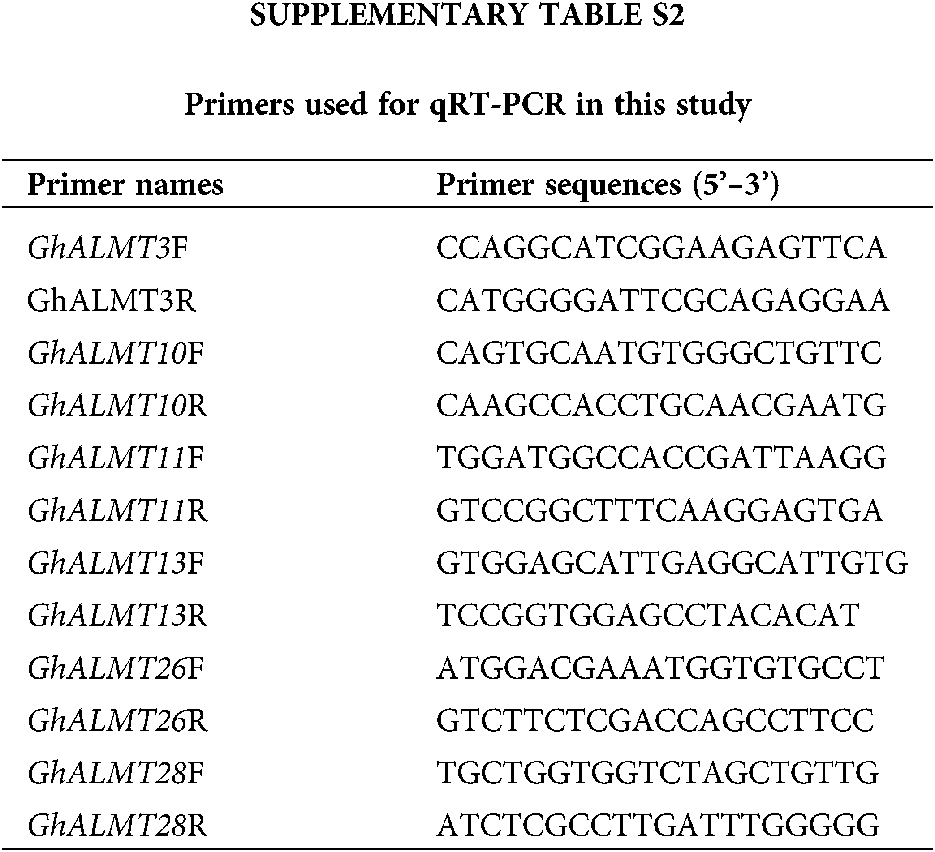

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

G. hirsutum (cv CCRI45) and CSSLs7747 were grown on farms regulated by the Institute of Cotton Research of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (ICR-CAAS) in Anyang, China. Fibers were collected from six developmental time-points post-anthesis (5DPA), namely 7DPA, 10DPA, 15DPA, 20DPA, 25DPA and three biological repeats for qRT-PCR, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and maintained at −80°C until further analysis.

Total RNA isolation was performed with FastPure Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Polysaccharides & Polyphenolics–rich) (RC401, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Two percent gel electrophoresis and Nanodrop2000 nucleic acid analyzer were used for assessment of RNA quality. cDNA synthesis was done with the HiScript III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper) (R312, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The qRT-PCR procedure followed the operational guidelines outlined in the Cham Q Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix kit (Q711, Vazyme, Nanjing, China), which is a part of the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). To detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs), primers were synthesized using Primer-BLAST (NCBI database). Primers used in this study are summarized in Suppl. Table S2. Endogenous β-actin, with sequence of F: 5’-ATCCTCCGTCTTGACCTTG-3’ and R: 5’-TGTCCGTCAGGCAACTCAT-3’, was used for normalization of gene expression (Li et al., 2017). qRT-PCR was performed with 20 μL of cDNA and under the following conditions: 1 cycle of 94°C for 30 s; 40 cycles of 94°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 34 s, and 1 cycle of 60°C for 60 s. Each experiment was repeated three times. Finally, the relative gene levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt formula (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Acknowledgement: The authors appreciate Pengyun Chen’s cacography with the phylogenetic and synthetic analyses.

Author Contribution: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Youlu Yuan. Author, Yuzhen Shi. Author; data collection: Ruili Chen. Author, Xianghui Xiao. Author; analysis and interpretation of results: Renhai Peng. Author, Pengtao Li. Author, Juwu Gong. Author; draft manuscript preparation: Quanwei Lu. Author; Renhai Peng. Author. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1804103, 31101188), Sponsored by State Key Laboratory of Cotton Biology Open Fund (CB2020A10).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE et al. (2009). MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Research 37: W202–W208. [Google Scholar]

Basra AS, Malik C (1984). Development of the cotton fiber. International Review of Cytology 89: 65–113. [Google Scholar]

Gokani S, Kumar R, Thaker V (1998). Potential role of abscisic acid in cotton fiber and ovule development. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 17: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

Guo AY, Zhu QH, Chen X, Luo JC (2007). GSDS: A gene structure display server. Hereditas 29: 1023–1026. [Google Scholar]

Hu Y, Chen J, Fang L, Zhang Z, Ma W et al. (2019). Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nature Genetics 51: 739–748. [Google Scholar]

Jung K-H, An G, Ronald PC (2008). Towards a better bowl of rice: Assigning function to tens of thousands of rice genes. Nature Reviews Genetics 9: 91–101. [Google Scholar]

Kovermann P, Meyer S, Hörtensteiner S, Picco C, Scholz-Starke J et al. (2007). The Arabidopsis vacuolar malate channel is a member of the ALMT family. Plant Journal 52: 1169–1180. [Google Scholar]

Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R et al. (2009). Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Research 19: 1639–1645. [Google Scholar]

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K (2018). MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35: 1547. [Google Scholar]

Li PT, Wang M, Lu QW, Ge Q, Liu AY et al. (2017). Comparative transcriptome analysis of cotton fiber development of Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and Chromosome Segment Substitution Lines from G. hirsutum × G. barbadense. BMC Genomics 18: 705. [Google Scholar]

Liu J, Zhou M, Delhaize E, Ryan PR (2017). Altered expression of a malate-permeable anion channel, OsALMT4, disrupts mineral nutrition. Plant Physiology 175: 1745–1759. [Google Scholar]

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408. [Google Scholar]

Lu Q, Shi Y, Xiao X, Li P, Gong J et al. (2017). Transcriptome analysis suggests that chromosome introgression fragments from sea island cotton (Gossypium barbadense) increase fiber strength in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). G3: -Genes, Genomes, Genetics 7: 3469–3479. [Google Scholar]

Ma B, Yuan Y, Gao M, Qi T, Li M et al. (2018). Genome-wide identification, molecular evolution, and expression divergence of aluminum-activated malate transporters in apples. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19: 2807. [Google Scholar]

Meinert MC, Delmer DP (1977). Changes in biochemical composition of the cell wall of the cotton fiber during development. Plant Physiology 59: 1088–1097. [Google Scholar]

Meyer S, de Angeli A, Fernie AR, Martinoia E (2010a). Intra- and extra-cellular excretion of carboxylates. Trends in Plant Science 15: 40–47. [Google Scholar]

Meyer S, Mumm P, Imes D, Endler A, Weder B et al. (2010b). AtALMT12 represents an R-type anion channel required for stomatal movement in Arabidopsis guard cells. Plant Journal 63: 1054–1062. [Google Scholar]

Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL (2016). Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nature Protocols 11: 1650–1667. [Google Scholar]

Qin YM, Zhu YX (2011). How cotton fibers elongate: A tale of linear cell-growth mode. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 14: 106–111. [Google Scholar]

Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N et al. (2005). InterProScan: Protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Research 33: W116–W120. [Google Scholar]

Ren Z, Yu D, Yang Z, Li C, Qanmber G et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification of the MIKC-type MADS-box gene family in Gossypium hirsutum L. unravels their roles in flowering. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 384. [Google Scholar]

Ruan YL, Llewellyn DJ, Furbank RT (2001). The control of single-celled cotton fiber elongation by developmentally reversible gating of plasmodesmata and coordinated expression of sucrose and K+ transporters and expansin. Plant Cell 13: 47–60. [Google Scholar]

Sasaki T, Mori IC, Furuichi T, Munemasa S, Toyooka K et al. (2010). Closing plant stomata requires a homolog of an aluminum-activated malate transporter. Plant and Cell Physiology 51: 354–365. [Google Scholar]

Sasaki T, Tsuchiya Y, Ariyoshi M, Nakano R, Ushijima K et al. (2016). Two members of the aluminum-activated malate transporter family, SlALMT4 and SlALMT5, are expressed during fruit development, and the overexpression of SlALMT5 alters organic acid contents in seeds in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Plant and Cell Physiology 57: 2367–2379. [Google Scholar]

Sharma T, Dreyer I, Kochian L, Piñeros MA (2016). The ALMT family of organic acid transporters in plants and their involvement in detoxification and nutrient security. Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 1488. [Google Scholar]

Sturn A, Quackenbush J, Trajanoski Z (2002). Genesis: Cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics 18: 207–208. [Google Scholar]

Takanashi K, Sasaki T, Kan T, Saida Y, Sugiyama A et al. (2016). A dicarboxylate transporter, LjALMT4, mainly expressed in nodules of Lotus japonicus. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 29: 584–592. [Google Scholar]

Wilkins T, Wan CY, Lu CC (1994). Ancient origin of the vacuolar H+-ATPase 69-kilodalton catalytic subunit superfamily. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 89: 514–524. [Google Scholar]

Xu LL, Xiao X, Zhang MY, Zhang SL (2018). Genome-wide analysis of aluminum-activated malate transporter family genes in six rosaceae species, and expression analysis and functional characterization on malate accumulation in Chinese white pear. Plant Science 274: 451–465. [Google Scholar]

Xiao X, Lu Q, Liu R, Gong J, Gong W et al. (2019). Genome-wide characterization of the UDP-glycosyltransferase gene family in upland cotton. 3 Biotech 9: 453. [Google Scholar]

Zhang T, Chen S, Harmon AC (2014). Protein phosphorylation in stomatal movement. Plant Signaling & Behavior 9: e972845. [Google Scholar]

Zhang T, Hu Y, Jiang W, Fang L, Guan X et al. (2015). Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nature Biotechnology 33: 531–537. [Google Scholar]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |