DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.016121

| BIOCELL DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.016121 |  |

| Article |

RNA-sequencing indicates high hemocyanin expression as a key strategy for cold adaptation in the Antarctic amphipod Eusirus cf. giganteus clade g3

1Department of Life Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, 34127, Italy

2Department of Biology, University of Padova, Padova, 35131, Italy

*Address correspondence to: Marco Gerdol, mgerdol@units.it

#These authors contributed equally to this work

Received: 08 February 2021; Accepted: 11 March 2021

Abstract: We here report the de novo transcriptome assembly and functional annotation of Eusirus cf. giganteus clade g3, providing the first database of expressed sequences from this giant Antarctic amphipod. RNA-sequencing, carried out on the whole body of a single juvenile individual likely undergoing molting, revealed the dominant expression of hemocyanins. The mRNAs encoding these oxygen-binding proteins cumulatively accounted for about 40% of the total transcriptional effort, highlighting the key biological importance of high hemocyanin production in this Antarctic amphipod species. We speculate that this observation may mirror a strategy previously described in Antarctic cephalopods, which compensates for the decreased ability to release oxygen to peripheral tissues at sub-zero temperatures by massively increasing total blood hemocyanin content compared with temperate species. These preliminary results will undoubtedly require confirmation through proteomic and biochemical analyses aimed at characterizing the oxygen-binding properties of E. cf. giganteus clade g3 hemocyanins and at investigating whether other Antarctic arthropod species exploit similar adaptations to cope with the challenges posed by the extreme conditions of the polar environment.

Keywords: Antarctica; Cold adaptation; Hemocyanin; Amphipod; Transcriptome

Crustaceans are the most species-rich group of metazoans in Antarctic benthic communities (Arntz et al., 1994) and amphipods largely contribute to this biodiversity, with over 800 different species described to date (de Broyer and Jazdzewski, 1993; 1996). Moreover, several Antarctic crustacean species are believed to comprise complexes of cryptic or species that still remain to be formally described (Brandão et al., 2010; Held and Wägele, 2005; Loerz et al., 2009; Raupach and Wägele, 2006). Thanks to the high oxygen availability of Antarctic waters, amphipods occupy all available microhabitats of the Southern Hemisphere and can therefore be considered among the most successful colonizers of these marine environments (Levin and Gage, 1998). Even though Antarctic amphipods most certainly occupy a key position in polar trophic chains (Dauby et al., 2001; 2002), studies focused on these widespread metazoans are still relatively scarce, and molecular or genetic data are nearly entirely missing for several relevant genera commonly found in polar waters.

Amphipods belonging to the genus Eusirus (Krøyer, 1845), and part of the suborder Amphilochidea, superfamily Eusiroidea, have been long known to have a broad circum-Antarctic distribution. According to the Register of Antarctic Marine Species, eight different species belonging to the Eusirus genus have been described to date in the Antarctic continent: Eusirus antarcticus Thomson, 1880, Eusirus bouvieri Chevreux, 1911, Eusirus giganteus Andres, Lörz & Brandt, 2002, Eusirus laevis Walker, 1903, Eusirus laticarpus Chevreux, 1906, Eusirus microps Walker, 1906, Eusirus perdentatus Chevreux, 1912 and Eusirus propeperdentatus Andres, 1979. E. perdentatus, the most widespread and the largest among these species, shows typical features of Antarctic gigantism, with adult individuals reaching and often exceeding the size of 70 mm (Chapelle, 2002). However, the marginal morphological differences between E. perdentatus and the congeneric E. giganteus, first described in 1972, have been the source of taxonomical uncertainties over the years (Andres et al., 2002), until 2012, when molecular approaches were applied for the first time to study Antarctic giant amphipod populations. The results provided by these studies have challenged previously accepted taxonomy, strongly hinting at the presence of multiple cryptic species with limited gene flow among each other. In particular, the authors found that E. perdentatus harbored two previously undetected cryptic species and E. giganteus at least three, defined as clade g1, g2 and g3, some of which occur in sympatry (Baird et al., 2011).

Therefore, although specimens collected in several different locations across all Antarctica have been previously classified as belonging to E. giganteus (Gutt, 2008; OBIS, 2020; Verheye et al., 2016), it is likely that these represent multiple cryptic species. Hence, all data collected for this organism should be referred to E. cf. giganteus.

Despite the prevalence of Eusiridae in Antarctic high latitude waters, molecular data are nearly not existing for this taxon, with a total of 220 nucleotide sequences deposited in GenBank (as of March 9th, 2021). At the same time, studies on Eusirus spp. remain very limited, and, to the best of our knowledge, the molecular and genetic bases of its adaptation to cold have not been explored in detail. This aspect may be of particular interest due to the possible threats giant amphipod species could face due to climate change along with the progressive decline of ocean oxygen availability expected to occur in the next few decades (Spicer and Morley, 2019).

With this work, we tried to fill this knowledge gap, providing a reference annotated transcriptome assembly for E. cf. giganteus clade g3 (the first resource of this kind in the infraorder Amphilochida), which may serve as a reference for future studies and could provide a useful resource to investigate molecular strategies of cold adaptation in Antarctic amphipods. Due to the difficult sampling of these organisms in the Antarctic environment and the current lack of transcriptome data from adult individuals, the gene expression data here reported should be taken with caution. Similarly, the collection of expressed sequences obtained in this study should be considered as a preliminary overview of the transcriptomic landscape of the species, with a focus on biologically relevant transcripts in the juvenile life stages.

Sample collection and RNA-sequencing

A single E. giganteus specimen was collected as bycatch during the sampling campaign of the intended target species, the amphipod Pseudorchomene plebs (Hurley, 1965). Sampling occurred close to the Italian Mario Zucchelli Antarctic Base (Ross Sea 74° 38’ 402” S, 164° 39’ 281” E), in November 2017, within the frame of the activities of the Italian XXXIII PNRA expedition. The specimen was a juvenile, approximately 15.8 mm long (from the tip of the head to the base of the telson along the dorsal side), of undetermined sex.

The animal was transferred to the facilities of the base, in a tank with oxygenated running seawater at the same temperature recorded in the natural external environment (−1.9°C). After one week of acclimatization to the recovery from the stress of sampling, the specimen was sacrificed by immersion in RNAlater (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and immediately stored at −80°C.

Following its transportation to the laboratories of the University of Trieste, the specimen was moved into Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and homogenized. RNA extraction was carried out following the manufacturer’s instructions, yielding material of sufficient quality and quantity to prepare an mRNA-seq library with the Lexogen SENSE mRNA-seq library prep kit v2 (Lexogen, Wien, Austria), as evaluated by the use of an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). Briefly, following a poly(A) selection step used to remove non-polyadenylated RNAs, the sequencing library was prepared with the proprietary strand displacement stop/ligation technology developed by Lexogen.

RNA-sequencing was performed at the Genomics and Epigenomics Platform of the Area Science Park (Trieste, Italy), on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 instrument, with a 2 × 150 bp paired-end strategy.

The sample collection complied with the regulations provided by the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research concerning activities and environmental protection in Antarctica and with the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the 137 Antarctic Treaty, Annex II, Art. 3. All the activities on animals performed during the Italian Antarctic Expedition were under the control of a PNRA Ethics Referent, which acts on behalf of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In particular, the required data for the project PNRA16_00099 are as follows. Name of the ethics committee or institutional review board: Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Name of PNRA Ethics Referent: Dr. Carla Ubaldi, ENEA Antarctica, Technical Unit (UTA).

Sequencing data processing, de novo transcriptome assembly and annotation

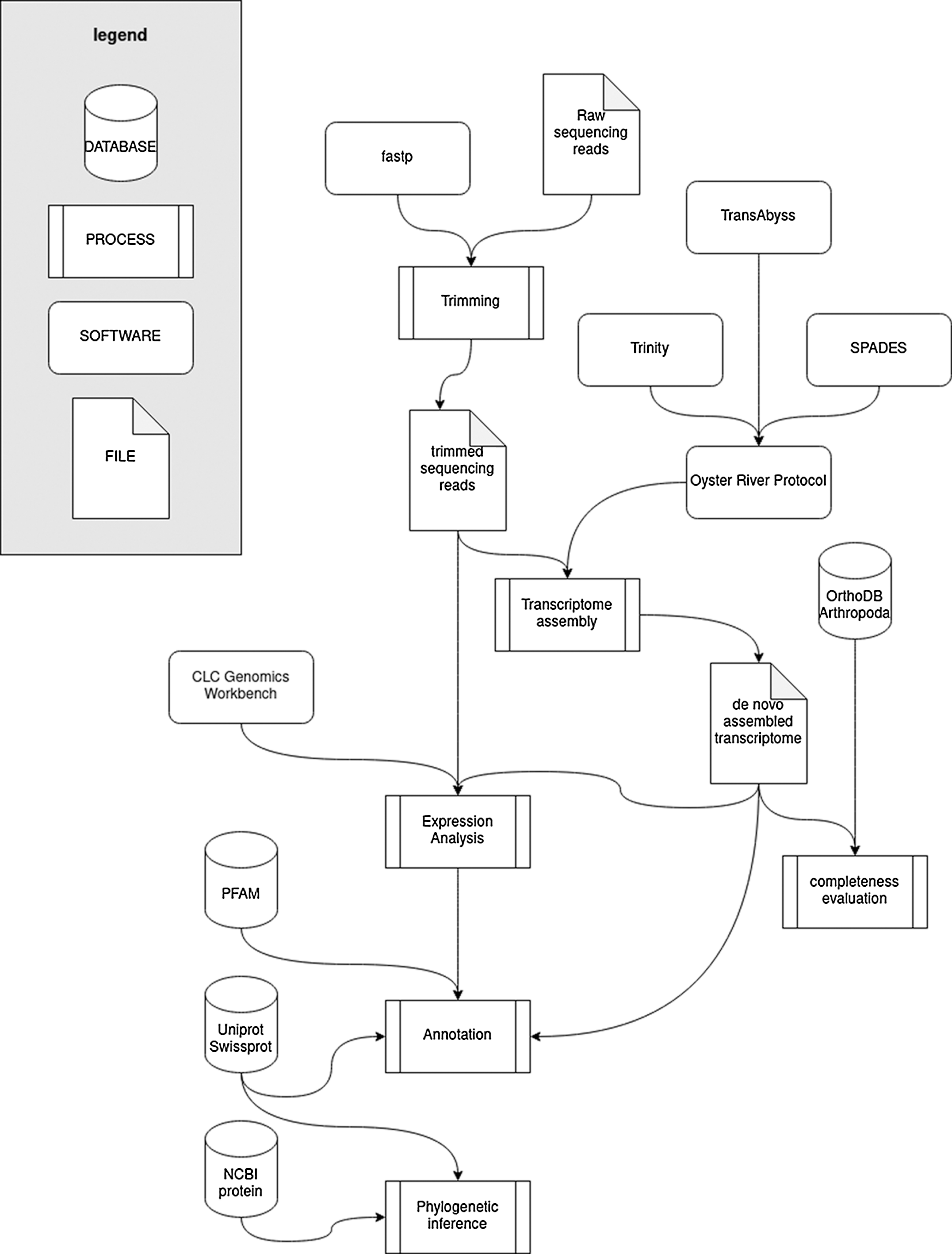

Raw reads were subjected to base-calling and sequencing quality trimming according to the output of FastQC v. 0.11.9 (Andrews, 2010) with fastp v. 0.20.0 (Chen et al., 2018). Trimmed reads were used as an input for a de novo transcriptome assembly using the Oyster River Protocol (ORP) v.2.3.1 (MacManes, 2018), a tool that generates a unique, non-redundant assembly by joining the outputs of Trinity (Grabherr et al., 2011), SPAdes (Bankevich et al., 2012) and TransABySS (Robertson et al., 2010). The k-mer setting used for the different assembly algorithms were as follows: with kmer sizes for the four assemblies of 25 (Trinity), 32, 55 (SPAdes), and 75 (TransABySS). The minimum contig length was set to 200 nucleotides. Poorly expressed contigs, which may either derive from exogenous contamination (e.g., gut content) or from transcripts with little biological relevance were excluded from the assembly using the TPM FILT = 1 parameter.

The completeness of the transcriptome was evaluated with an analysis carried out with BUSCO v.4.1.4 (Simão et al., 2015), using default settings, against the OrthoDB v.10 database (Kriventseva et al., 2019), checking the presence of a set of highly conserved single-copy orthologs shared by all arthropods.

The transcriptome was functionally annotated with AnnotaM (https://gitlab.com/54mu/annotaM), associating each contig to Gene Ontology terms (Ashburner et al., 2000) and Pfam conserved protein domains (Punta et al., 2012). Annotation was based on BLASTx matches against the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (e-value threshold = 1 × 10−5), which were used to extract GO terms, and HMMer v.3.1b2 (Finn et al., 2011) matches of the proteins inferred by computational prediction (using TransDecoder v.5.5.0, https://github.com/TransDecoder/) from the assembled contigs against the Pfam-A 34.0 database with default settings.

Gene expression levels were calculated as Transcript Per Million (TPM) (Wagner et al., 2012), based on read mapping using the CLC Genomics Workbench v.20 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) RNA-seq mapping tool, with stringent parameters (length fraction = 0.75, similarity fraction = 0.98).

A schematic workflow of the bioinformatics approach outlined above is reported in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic workflow of the bioinformatics strategy used to obtain and analyze the de novo transcriptome assembly.

Hemocyanin sequence characterization and phylogenetic analysis

We recovered a single Hc-encoding contig bearing a complete Open Reading Frame thanks to the inspection of the preliminary assemblies produced by ORP. This was virtually translated into an amino acid sequence with the Expasy translate tool (Gasteiger et al., 2003), and the presence of the six histidine residues expected to be involved in copper binding in arthropod Hcs was evaluated based on the literature data (Burmester, 1999).

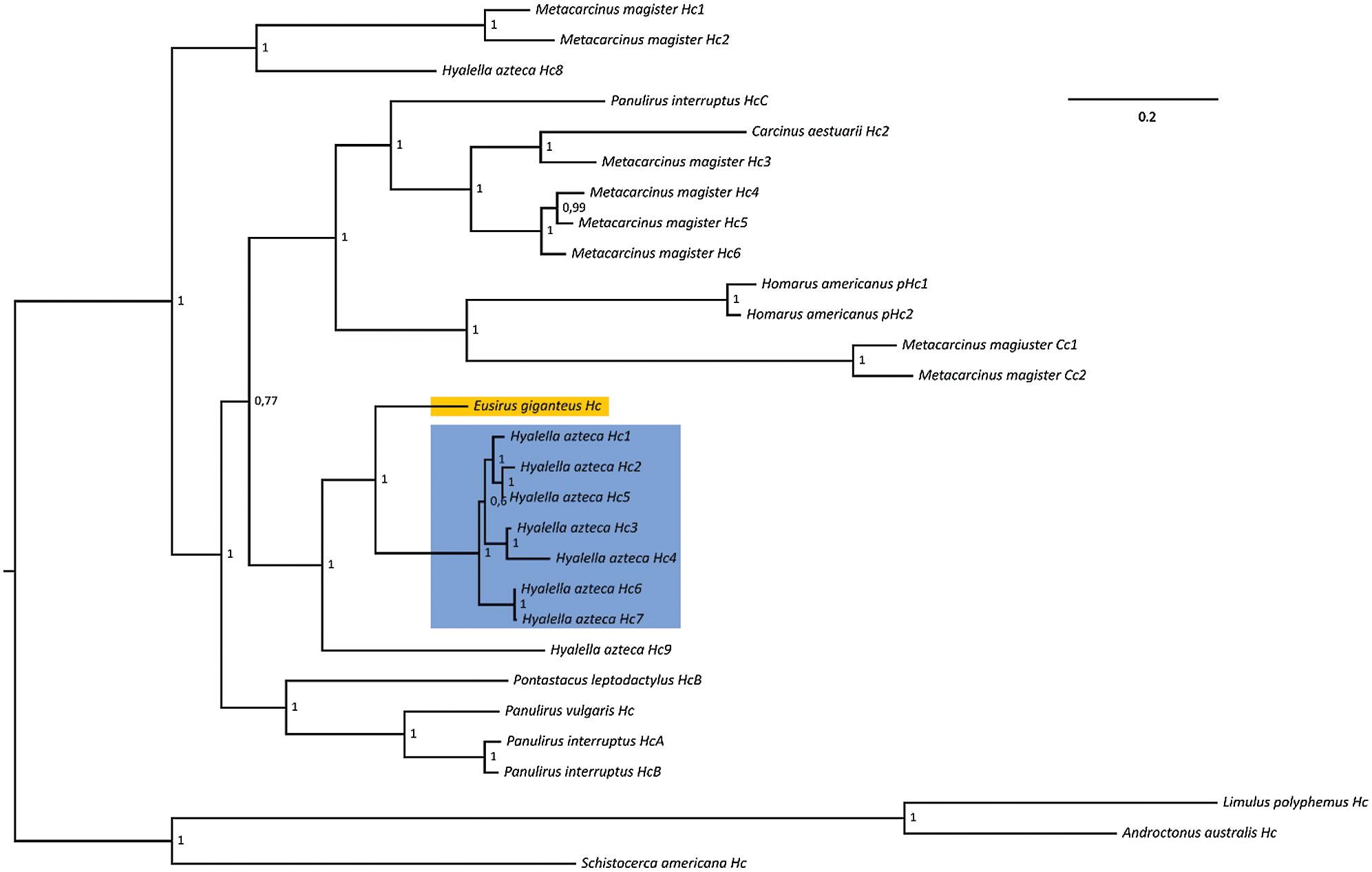

The sequences of C. magistrus Hc and cryptocyanins (Terwilliger et al., 2006), as well as other phylogenetically informative crustacean sequences from UniProtKB and nr were also included in the creation of a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) with MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). Namely, P. vulgaris Hc (P80888.2), P. interruptus Hc chain A (P04254.2), B (P10787.1) and C (P80096.1), Homarus americanus pseudocyanin-1 (Q6KF82.1) and -2 (Q6KF81.1), Carcinus aestuarii Hc subunit 2 (P84293.1) and Pontastacus leptodactylus Hc chain B (P83180.1) were used, along with the Hc sequences obtained from the genome of the amphipod H. azteca (Poynton et al., 2018). The Hc sequenced from Limulus polyphemus (P04253.2), Schistocerca americana (AAC16760.1) and Androctonus australis (P80476.1) were used as outgroups for tree rooting purposes.

The MSA was processed with Gblocks (Talavera and Castresana, 2007) to remove phylogenetically non-informative positions. The resulting file was analyzed with Modeltest-ng (Darriba et al., 2020) to assess the best-fitting model of molecular evolution, which was identified as the Le and Gascuel model, with a gamma-distributed rate of variation across sites and a fixed (empirical) prior on state frequencies (LG+G+F) (Le and Gascuel, 2008). The model choice was based on the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (Cavanaugh, 1997).

Phylogenetic inference analysis was carried out with MrBayes v. 3.2.7a (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001), with two MCMC analyses run in parallel for 200,000 generations, until all estimated parameters of the model reached an ESS >= 200, as estimated with Tracer v.1.7 (Rambaut et al., 2018).

The aforementioned presence of multiple Eusirus spp. cryptic species in Antarctica, whose recognition is not possible by morphological examination, implies the need to use genetic markers for proper taxonomical identification. The general external morphology of an adult Eusirus cf. giganteus individual, sampled in the same geographical location where the juvenile specimen used for RNA-sequencing was collected (see the Materials and Methods section), is exemplified in Fig. 2. Although molecular data available for this genus are very scarce, the screening of the transcriptomes for previously studied molecular markers allowed us to unequivocally place the specimen target of this study within the clade g3 of Eusirus cf. giganteus identified by Baird and colleagues (Baird et al., 2011). Indeed, the sequences of cytochrome oxidase 1 (JN001762.1), cytochrome B (JN001729.1), and the Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 (JN001807.1) perfectly matched, without gaps and mismatches, those reported in this study. Clade g3 has been previously linked with primary distribution in the Ross Sea along with another E. cf. giganteus clade (i.e., clade g2) and two E. cf. perdentatus clades (i.e., p1 and p3), which is consistent with the placement of the Mario Zucchelli Antarctic Base.

Figure 2: External morphology of an adult Eusirus cf. giganteus individual, collected close to the Italian Mario Zucchelli Antarctic Base (Ross Sea 74° 38’ 402” S, 164° 39’ 281” E), in November 2017.

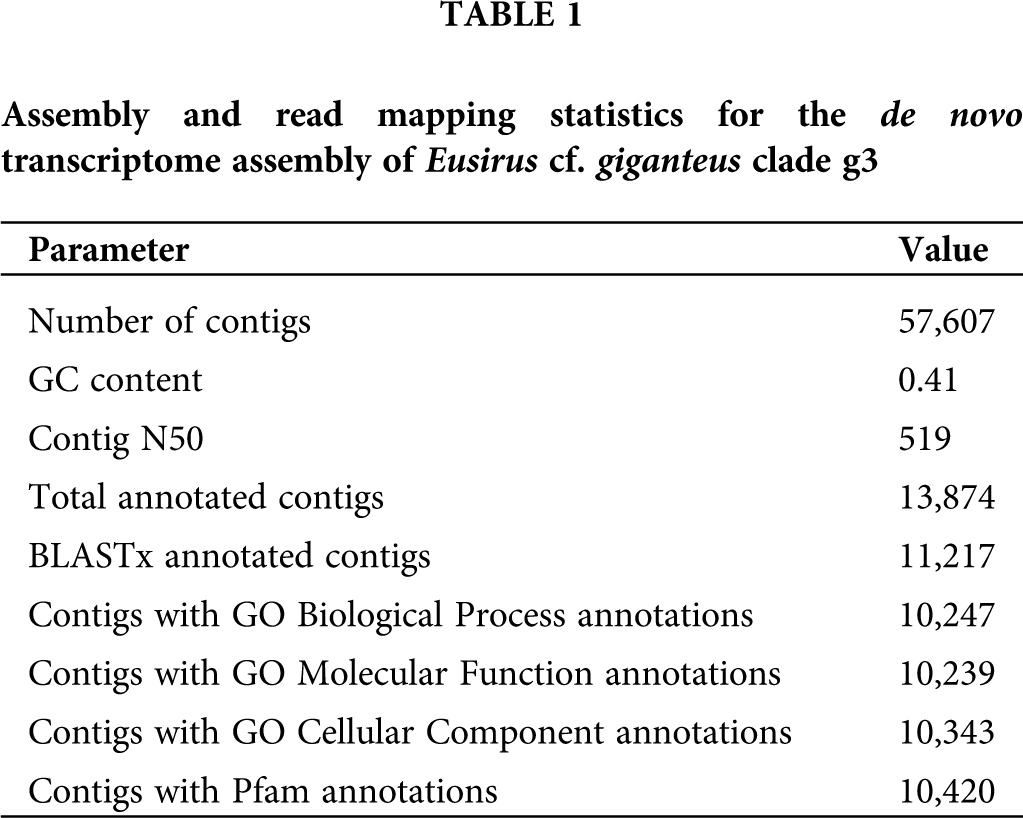

Transcriptome assembly and annotation

The de novo transcriptome assembly, generated starting from a total of 101,310,170 trimmed paired-end Illumina reads, comprised 57,607 contigs, 4,369 of which exceeded 1 kb in length (Tab. 1). 11,217 contigs (19.47%) were annotated based on significant BLASTx matches in UniProtKB, leading to the association of 10,247, 10,239 and 10,343 contigs with Gene Ontology Biological Process, Molecular Function and Cell Component terms, respectively. Moreover, 10,420 contigs (18.09% of the total) were associated with one or more Pfam conserved domains. The observed mapping rate was 78.26%. The complete list of annotated contigs, along with associated functional annotations and gene expression levels, are listed in Suppl. Tab. S1.

The challenges posed by the collection of biological samples in the Antarctic environment, unfortunately, prevented the possibility to retrieve additional juvenile individuals from the same species in the Antarctic expedition that took place in November 2017, as all the other similarly sized sampled arthropod specimens were determined to belong to the Pseudorchomene (Schellenberg, 1926) genus. The lack of biological replicates in this study undoubtedly calls for extreme caution in the interpretation of the gene expression data, and further analyses carried out on a larger number of samples will be necessary to confirm, in the future, the results outlined in the following sections.

Nevertheless, this transcriptome assembly, the first resource of this kind available for Eusirus spp., will most certainly represent a useful tool to pave the way for genetic and molecular studies in this species complex in the years to come.

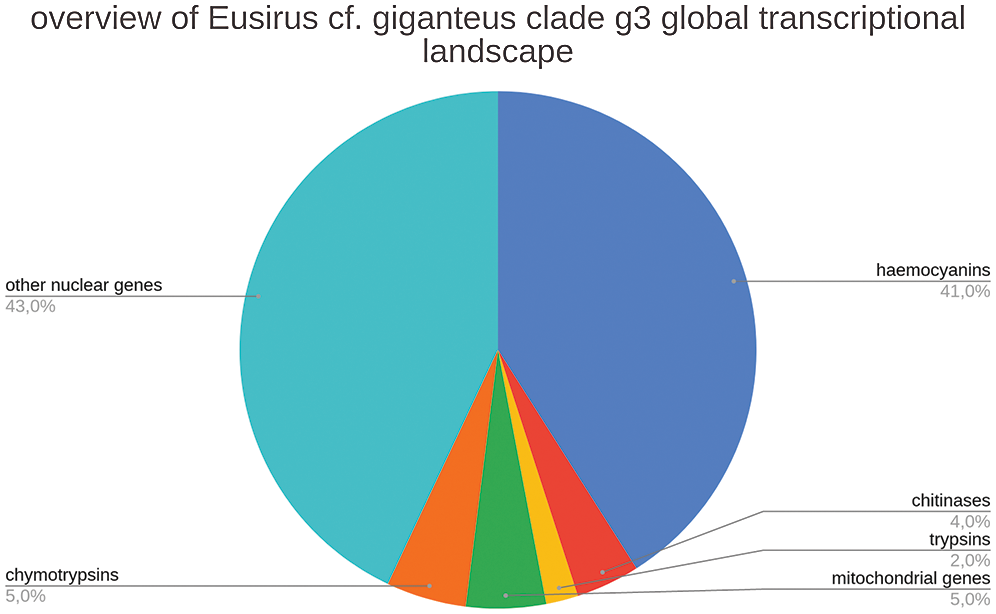

High expression of hemocyanins

The E. cf. giganteus clade g3 transcriptome displayed an unusual skewed distribution of read mapping, with nearly 30 million reads being captured by a relatively high number of fragmented contigs sharing the same functional annotation as hemocyanins. Cumulatively, these contigs accounted for 411,000 Transcripts Per Million (TPM), indicating that an extraordinarily high transcriptional effort (i.e., over 40% of the total) was employed in the synthesis of mRNAs encoding these oxygen-transporting proteins (Fig. 3).

Several of the other contigs achieving TPM values >10,000 and expressed at levels higher than housekeeping genes such as ribosomal structural proteins and components of the mRNA transcription machinery, shared close homology with trypsins, chymotrypsins, chitinases or brachyurins (Fig. 3). All these proteins play a fundamental role in the molting process in crustaceans (Gao et al., 2017; van Wormhoudt et al., 1995), and this is consistent with the developmental stage of the sample individual. Indeed, juvenile amphipods would be expected to undergo frequent molting with relatively short intermolt periods (Chang and Mykles, 2011). Overall, these molting-related enzymes achieved a cumulative expression level of ~110,000 TPMs. Mitochondrial RNAs accounted for an additional ~50,000 TPMs, implying that less than 45% of the global transcriptional effort in E. cf. giganteus clade g3 was put in the synthesis of other nuclear mRNAs.

In line with such an unbalanced transcript representation, the de novo assembly process led to a collection of expressed transcripts characterized by a low level of completeness. This may be also in part ascribable to the fact that just a limited set of the genes expected to be expressed in adult individuals are transcribed at biologically relevant levels in amphipod juvenile individuals, where several tissues may not be fully developed yet. The impact of the extreme levels of expression of hemocyanins on the quality of the transcriptome assembly was clearly evidenced by the presence of just 29.6% complete arthropod BUSCOs, accompanied by a high number of fragmented (22.0%) and missing (48.4%) orthologs. The duplication rate, on the other hand, was rather low, standing at just 2.5%. These results highlight that the E. cf. giganteus clade g3 transcriptome assembly obtained in this study should be considered as a collection of the transcripts expressed at biologically relevant levels in the juvenile stages, but not as a comprehensive catalog of all mRNAs encoded by the genome of this species.

Figure 3: Overview of the transcriptional landscape of E. cf. giganteus clade g3, with details about the relative contribution to global transcription of contigs encoding hemocyanins, trypsins, chymotripsins, and chitinases. The relative contribution of non-nuclear (i.e., mitochondrial) genes is shown in a separate category.

Characterization of a highly expressed full-length hemocyanin sequence

Although 280 contigs could be linked with hemocyanins based on BLAST annotation, the vast majority of them were small fragments, measuring just a few hundred nucleotides, whereas the complete length of the coding sequence of arthropod hemocyanins was expected to be ~2 kb long, with a complete Open Reading Frame of ~700 codons.

The de novo sequencing strategy we applied, which combined three different transcriptome assembly algorithms (Trinity, SPAdes, and TransABySS), allowed us to explore in-depth the outputs of every single process, with the aim to recover the most likely full-length mRNA precursors. Significant fragmentation of hemocyanin mRNAs was evidenced in all assembly methods, which could be indicative of the presence of several nearly identical paralogous genes in this species. However, we recovered a single contig which included a complete Open Reading Frame of 673 codons. This sequence, capturing ~27.5 million reads, reached an expression level equal to ~118,550 TPMs, thereby accounting for over 10% of the global transcriptional effort of E. cf. giganteus clade g3.

This hemocyanin sequence found the best BLASTx match with the Hc A and B chains from the decapods Panulirus interruptus and Panulirus vulgaris, among those deposited in UniProtKB (64% pairwise sequence identity) (Bak and Beintema, 1987; Jekel et al., 1996; 1988), and with the Hc subunit 1 from Gammarus roeseli among those deposited in nr (82% pairwise sequence identity) (Hagner-Holler et al., 2005).

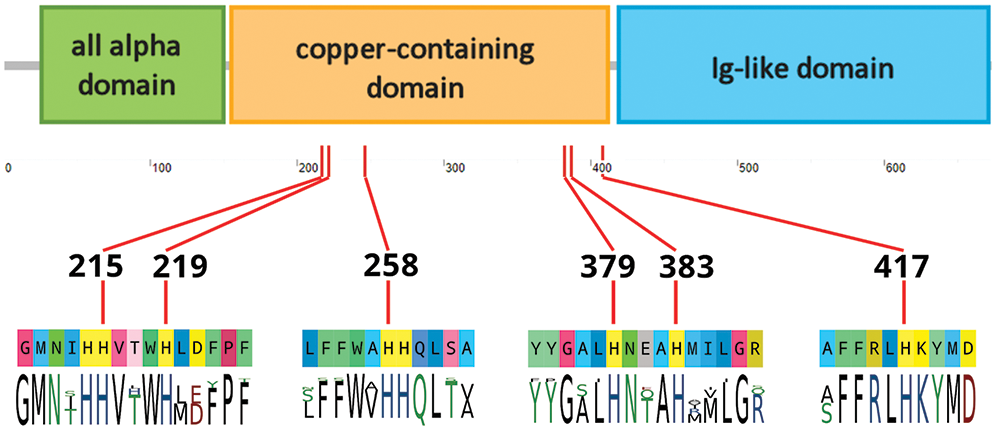

The E. cf. giganteus clade g3 Hc displayed the three expected canonical domains found in arthropod hemocyanins, i.e., the all N-terminal all alpha domain (PF03722), the central copper-containing domain (PF00372), and the C-terminal Ig-like domain (PF03723). Moreover, the copper-containing domain presented all the six highly conserved histidine residues involved in copper binding, confirming its identification as a bona fide Hc (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Schematic overview of the domain organization of Eusirus cf. giganteus clade g3 hemocyanin. A detail of the six histidine residues expected to be involved in copper binding is provided (His215, His219, His258, His379, His383, His417), along with the consensus sequence of the neighboring residues in crustacean hemocyanin sequences deposited in UniProtKB.

Hemocyanins, found only in Arthropoda and Mollusca, are only second in abundance to hemoglobins as molecules capable of temporarily binding oxygen in organs devoted to gaseous exchange, transporting it to peripheral tissues, and releasing it to these locations due to lower partial pressure (Redmond, 1955). In polar regions, and in particular, in the Southern Ocean, where seawater temperature is constantly below zero, the increased solubility of oxygen potentially offers the opportunity for astounding adaptations that involve the circulatory system and oxygen-carrying molecules, such as in the case of icefish (Beers et al., 2010). However, this increased oxygen solubility may paradoxically result in a lower bioavailability due to the difficulties linked with its release in tissues.

The few studies carried out so far on hemocyanins in Antarctica have revealed that some invertebrates developed interesting molecular strategies to overcome this issue. For example, the Antarctic octopus Pareledone charcoti compensates a lower Hc oxygen-binding affinity with a higher hemocyanin content in hemolymph compared with species living in temperate waters (Oellermann et al., 2015). Although no proteomic data are available for E. cg. giganteus clade g3 to evaluate the actual relative abundance of hemocyanins in the hemolymph, we here provide evidence suggesting that a similar strategy might have been employed by this Antarctic amphipod.

We show that hemocyanin-encoding mRNAs cumulatively accounted for nearly 40% of the total transcriptional effort of the juvenile individual subjected to RNA-sequencing, suggesting that Hcs are by far the most abundant plasma proteins in this species. Transcriptome data strongly suggest that multiple highly similar hemocyanin mRNAs are simultaneously expressed, which would point towards the existence of several co-regulated paralogous Hc gene copies. This would be in line with the organization of Hc genes found in other amphipods, such as Hyalella azteca, which harbors 9 Hc genes, seven of which display very high pairwise sequence homology (Poynton et al., 2018). Likewise, high sequence similarity between different crustacean hemocyanin chains has also been previously shown in P. interruptus, where Hc A and B chains share 96% primary sequence identity (Jekel et al., 1988).

In the absence of genomic data, this remains as a working hypothesis which would, however, provide a reasonable explanation for the extremely high levels of expression of E. cf. giganteus clade g3 Hcs and for the observed severe fragmentation of Hc-coding contigs. Indeed, the low pairwise sequence divergence among paralogous gene copies might have hampered the possibility to obtain a full-length assembly for the other isoforms.

The single complete Hc mRNA sequence we retrieved, which presumably represents the most highly expressed isoform, encodes a full-length protein with all the expected structural features of functional hemocyanins, i.e., the presence of the three characterizing all alpha, copper-containing, and Ig-like domains, as well as of the six conserved residues involved in copper binding (Fig. 3). Bayesian phylogeny placed this sequence with high confidence within known members of the crustacean hemocyanin superfamily and close to a cluster of seven highly similar paralogous genes from the amphipod Hyalella azteca. At the same time, the E. cf. giganteus clade g3 sequence only showed distant homology with non-respiratory crustacean cryptocyanins and pseudohemocyanins, which lack two of the histidine residues in the aforementioned array (Burmester, 1999; Terwilliger et al., 1999) (Fig. 5).

Altogether, these observations suggest that E. cf. giganteus clade g3, and possibly other Antarctic amphipods, may have evolved a strategy similar to that of cephalopods, maximizing the expression of oxygen-carrying molecules to overcome the decreased ability to unload oxygen in peripheral tissues at sub-zero temperatures. It remains to be determined whether this increased expression is linked with a decreased oxygen-binding affinity, as in cephalopods. Curiously, our findings are in stark contrast with those reported for other Antarctic crustaceans, such as Glyptonotus antarcticus (Whiteley et al., 1997), for which very low hemocyanin oxygen-binding capacities and low circulating protein levels have been reported. Further transcriptomic, proteomic, and biochemical studies targeting other Antarctic crustacean species may shed some light on this issue.

The preliminary indications deriving from this study have also important implications concerning the proposed relationship between oxygen availability and gigantism in Antarctic waters, which has been the subject of intense debate over the past few years (Spicer and Morley, 2019). Indeed, three alternative hypotheses have been proposed to explain the relationship between body size and oxygen bioavailability: (i) the “oxygen limitation hypothesis”, according to which gigantism is allowed by the combination between a higher availability of oxygen in freezing waters and the lowest metabolic rates observed in cold-adapted organisms (Chapelle and Peck, 1999); (ii) the “respiratory advantage hypothesis”, which is based on the idea that, in spite of a larger solubility, bioavailability in Antarctic waters is lower, due to a decreased diffusion coefficient, leading organisms with scarce respiratory control to develop gigantism (Verberk and Atkinson, 2013); (iii) the “symmorphosis hypothesis”, which postulates that Antarctic organisms have developed evolutionary adaptations to optimize oxygen supply, regardless of their body size (Woods et al., 2009).

In light of the imminent climate changes, whose effects are already visible in some areas of Antarctica, these alternative interpretations have profound effects on the predicted fate of giant amphipods. Indeed, these animals might be either among the first or among the latest organisms to face serious threats, depending on whether the oxygen limitation or the respiratory advantage hypotheses are correct (Spicer and Morley, 2019).

The exceptionally high expression of hemocyanins in E. cf. giganteus clade g3 seems to be in contrast with the hypothesis proposed by Chapelle and Peck. In this case, it clearly mirrors the strategy used by cephalopods to overcome the limited ability to unload oxygen in peripheral tissues at low temperatures, which would be consistent with the premises of the “respiratory advantage hypothesis”. However, it is noteworthy that, according to the latter hypothesis, gigantism would only be expected to occur in species lacking efficient respiratory pigments or with scarce respiratory control. Moreover, it remains to be established whether our observations also apply to adult individuals, which are considerably larger than the juvenile specimen analyzed in this study. Therefore, we cannot exclude that the high hemocyanin expression we described may fade to lower levels in adult individuals of larger size.

Clearly, the collection of additional physiological, biochemical and molecular data from Eusirus spp. and other giant Antarctic crustaceans that do not rely on high hemocyanin expression as a strategy for cold adaptation (such as G. antarcticus) would be needed to clarify the intricate relationships that exist between oxygen bioavailability, oxygen-carrying molecules and body size in these animals.

Figure 5: Bayesian phylogeny of crustacean hemocyanins. The placement of Eusirus giganteus hemocyanin is highlighted with an orange background. The cluster of paralogous hemocyanin genes from the amphipod Hyalella azteca is highlighted with a blue background. Posterior probability values are shown close to each node. Hc: hemocyanin; Cc: cryptocyanin; pHc: pseudohemocyanin.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Simone Canese and Erica Carlig for providing the specimen analyzed in this work.

Abbreviations: Hc: Hemocyanin, LG: Le and Gascuel model, MSA: Multiple Sequence Alignment, ORP: Oyster River Protocol, TPM: Transcript Per Million.

Availability of Data and Materials: Raw sequence data were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with the accession ID SRR13341529, under the BioProject PRJNA689112. The assembled contigs were deposited in the Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly database under the accession ID GIYD00000000.

Supplementary Material: The supplementary material is available online at DOI: 10.32604/biocell.2021.016121.

Author Contribution: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: M. Gerdol, P. G. Giulianini, P. Edomi; data collection: P. G. Giulianini, G. Santovito; analysis and interpretation of results: S. Greco, E. D’Agostino, A. S. Gaetano, F. Capanni, G. Furlanis, C. Manfrin; draft manuscript preparation: S. Greco, E. D’Agostino, M. Gerdol. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: The animal sample collection conducted in this study comply with Italy’s Ministry of Education, University and Research regulations concerning activities and environmental protection in Antarctica and with the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the 137 Antarctic Treaty, Annex II, Art 3. All the activities on animals performed during the Italian Antarctic Expedition were under the control of a PNRA Ethics Referent, which acts on behalf of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Italian Program of Antarctic Research (Grant No. PNRA16_00099).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Andres HG, Lörz AN, Brandt A (2002). A common but undescribed huge species of Eusirus from Antarctica (Crustacea, Amphipoda, Eusiridae). Mitteilungen aus dem Hamburgischen zoologische Museum und Institut 99: 109–126. [Google Scholar]

Andrews S (2010). FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Babraham Bioinformatics. https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/. [Google Scholar]

Arntz WE, Brey T, Gallardo VA (1994). Antarctic zoobenthos. In: Ansell AD, Gibson RN, Barnes M (eds.Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, pp. 241–304. UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H (2000). Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Gene Ontology Consortium. Nature Genetics 25: 25–29. DOI 10.1038/75556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baird HP, Miller KJ, Stark JS (2011). Evidence of hidden biodiversity, ongoing speciation and diverse patterns of genetic structure in giant Antarctic amphipods. Molecular Ecology 20: 3439–3454. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05173.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bak HJ, Beintema JJ (1987). Panulirus interruptus hemocyanin. The elucidation of the complete amino acid sequence of subunit a. European Journal of Biochemistry 169: 333–339. DOI 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13616.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M (2012). SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology 19: 455–477. DOI 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beers JM, Borley KA, Sidell BD (2010). Relationship among circulating hemoglobin, nitric oxide synthase activities and angiogenic poise in red- and white-blooded Antarctic notothenioid fishes. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 156: 422–429. DOI 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.03.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brandão SN, Sauer J, Schön I (2010). Circumantarctic distribution in Southern Ocean benthos? A genetic test using the genus Macroscapha (Crustacea, Ostracoda) as a model. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55: 1055–1069. DOI 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Burmester T (1999). Identification, molecular cloning, and phylogenetic analysis of a non-respiratory pseudo-hemocyanin of Homarus americanus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 274: 13217–13222. DOI 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cavanaugh JE (1997). Unifying the derivations for the Akaike and corrected Akaike information criteria. Statistics & Probability Letters 33: 201–208. DOI 10.1016/S0167-7152(96)00128-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chang ES, Mykles DL (2011). Regulation of crustacean molting: A review and our perspectives. General and Comparative Endocrinology 172: 323–330. DOI 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chapelle G (2002). Antarctic and Baikal amphipods: A key for understanding polar gigantism (Ph.D. Thesis). Unviersite Catholique de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

Chapelle G, Peck LS (1999). Polar gigantism dictated by oxygen availability. Nature 399: 114–115. DOI 10.1038/20099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J (2018). fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34: i884–i890. DOI 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Darriba D, Posada D, Kozlov AM, Stamatakis A, Morel B, Flouri T (2020). ModelTest-NG: A new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Molecular Biology and Evolution 37: 291–294. DOI 10.1093/molbev/msz189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dauby P, Scailteur Y, Chapelle G, De Broyer C (2002). Potential impact of the main benthic amphipods on the eastern Weddell Sea shelf ecosystem (Antarctica). In: Arntz WE, Clarke A (eds.Ecological Studies in the Antarctic Sea ice Zone: Results of Easiz Midterm Symposium, pp. 45–50. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Dauby P, Scailteur Y, De Broyer C (2001). Trophic diversity within the eastern Weddell Sea amphipod community. Hydrobiologia 443: 69–86. DOI 10.1023/A:1017596120422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

de Broyer C, Jazdzewski K (1996). Biodiversity of the Southern Ocean: towards a new synthesis for the Amphipoda (Crustacea). Bolletino del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona 20: 547–568. [Google Scholar]

de Broyer C, Jazdzewski K (1993). Contribution to the marine biodiversity inventory. A checklist of the Amphipoda (Crustacea) of the Southern Ocean. Documents de Travail de l’Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique 73: 1–174. [Google Scholar]

Edgar RC (2004). MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792–1797. DOI 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR (2011). HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Research 39: W29–W37. DOI 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gao Y, Wei J, Yuan J, Zhang X, Li F, Xiang J (2017). Transcriptome analysis on the exoskeleton formation in early developmetal stages and reconstruction scenario in growth-moulting in Litopenaeus vannamei. Scientific Reports 7: 1079. DOI 10.1038/s41598-017-01220-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gasteiger E, Gattiker A, Hoogland C, Ivanyi I, Appel RD, Bairoch A (2003). ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Research 31: 3784–3788. DOI 10.1093/nar/gkg563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology 29: 644–652. DOI 10.1038/nbt.1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gutt J, (2008). The expedition ANTARKTIS-XXIII/8 of the research vessel “Polarstern” in 2006/2007. Berichte zur Polar-und Meeresforschung (Reports on Polar and Marine Research): 569. [Google Scholar]

Hagner-Holler S, Kusche K, Hembach A, Burmester T (2005). Biochemical and molecular characterisation of hemocyanin from the amphipod Gammarus roeseli: Complex pattern of hemocyanin subunit evolution in Crustacea. Journal of Comparative Physiology B 175: 445–452. DOI 10.1007/s00360-005-0012-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Held C, Wägele JW (2005). Cryptic speciation in the giant Antarctic isopod Glyptonotus antarcticus (Isopoda, Valvifera, Chaetiliidae). Scientia Marina 69: 175–181. DOI 10.3989/scimar.2005.69s2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2001). MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17: 754–755. DOI 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hurley D, (1965). A common but hitherto underscribed species of Orchomenella (Crustacea Amphipoda-family Lysianassidae) from Ross Sea. Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand-Zoology 6: 107–113. [Google Scholar]

Jekel PA, Bak HJ, Soeter NM, Vereijken JM, Beintema JJ (1988). Panulirus interruptus hemocyanin. The amino acid sequence of subunit b and anomalous behaviour of subunits a and b on polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of SDS. European Journal of Biochemistry 178: 403–412. DOI 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14464.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jekel PA, Neuteboom B, Beintema JJ (1996). Primary structure of hemocyanin from Palinurus vulgaris. Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology Part B: Biochemistry & Molecular Biology 115: 243–246. DOI 10.1016/0305-0491(96)00119-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kriventseva EV, Kuznetsov D, Tegenfeldt F, Manni M, Dias R (2019). OrthoDB v10: Sampling the diversity of animal, plant, fungal, protist, bacterial and viral genomes for evolutionary and functional annotations of orthologs. Nucleic Acids Research 47: D807–D811. DOI 10.1093/nar/gky1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Le SQ, Gascuel O (2008). An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Molecular Biology and Evolution 25: 1307–1320. DOI 10.1093/molbev/msn067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Levin LA, Gage JD (1998). Relationships between oxygen, organic matter and the diversity of bathyal macrofauna. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 45: 129–163. DOI 10.1016/S0967-0645(97)00085-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Loerz A, Maas E, Linse K, Coleman CO (2009). Do circum-Antarctic species exist in peracarid Amphipoda? A case study in the genus Epimeria Costa, 1851 (Crustacea, Peracarida, Epimeriidae). ZooKeys 18: 91–128. DOI 10.3897/zookeys.18.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

MacManes MD (2018). The Oyster River Protocol: A multi-assembler and kmer approach for de novo transcriptome assembly. PeerJ 6: e5428. DOI 10.7717/peerj.5428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

OBIS (2020). Eusirus giganteus Andres. Lörz & Brandt, 2002, https://portal.obis.org/taxon/237660. [Google Scholar]

Oellermann M, Lieb B, Pörtner HO, Semmens JM, Mark FC (2015). Blue blood on ice: Modulated blood oxygen transport facilitates cold compensation and eurythermy in an Antarctic octopod. Frontiers in Zoology 12: 1925. DOI 10.1186/s12983-015-0097-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Poynton HC, Hasenbein S, Benoit JB, Sepulveda MS, Poelchau MF (2018). The toxicogenome of Hyalella azteca: A model for sediment ecotoxicology and evolutionary toxicology. Environmental Science & Technology 52: 6009–6022. DOI 10.1021/acs.est.8b00837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J (2011). The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Research 40: D290–D301. DOI 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Xie D, Baele G, Suchard MA (2018). Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biology 67: 901–904. DOI 10.1093/sysbio/syy032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Raupach MJ, Wägele JW (2006). Distinguishing cryptic species in Antarctic Asellota (Crustacea: Isopoda)-a preliminary study of mitochondrial DNA in Acanthaspidia drygalskii. Antarctic Science 18: 191–198. DOI 10.1017/S0954102006000228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Redmond JR (1955). The respiratory function of hemocyanin in crustacea. Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology 46: 209–247. DOI 10.1002/jcp.1030460204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Robertson G, Schein J, Chiu R, Corbett R, Field M (2010). De novo assembly and analysis of RNA-seq data. Nature Methods 7: 909–912. DOI 10.1038/nmeth.1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schellenberg A, (1926). Amphipoda 3: Die Gammariden der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition. Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition auf dem Dampfer “Valdivia” 1898–1899, vol. 23, pp. 19–243. [Google Scholar]

Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015). BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31: 3210–3212. DOI 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Spicer JI, Morley SA (2019). Will giant polar amphipods be first to fare badly in an oxygen-poor ocean? Testing hypotheses linking oxygen to body size. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374: 20190034. DOI 10.1098/rstb.2019.0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Talavera G, Castresana J (2007). Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Systematic Biology 56: 564–577. DOI 10.1080/10635150701472164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Terwilliger NB, Dangott L, Ryan M (1999). Cryptocyanin, a crustacean molting protein: Evolutionary link with arthropod hemocyanins and insect hexamerins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96: 2013–2018. DOI 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Terwilliger NB, Ryan M, Phillips MR (2006). Crustacean hemocyanin gene family and microarray studies of expression change during eco-physiological stress. Integrative and Comparative Biology 46: 991–999. DOI 10.1093/icb/icl012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

van Wormhoudt A, Sellos D, Donval A, Plaire-Goux S, Le Moullac G (1995). Chymotrypsin gene expression during the intermolt cycle in the shrimp Penaeus vannamei (Crustacea; Decapoda). Experientia 51: 159–163. DOI 10.1007/BF01929362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Verberk WCEP, Atkinson D (2013). Why polar gigantism and Palaeozoic gigantism are not equivalent: effects of oxygen and temperature on the body size of ectotherms. Functional Ecology 27: 1275–1285. DOI 10.1111/1365-2435.12152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Verheye ML, Martin P, Backeljau T, D’Acoz CD (2016). DNA analyses reveal abundant homoplasy in taxonomically important morphological characters of Eusiroidea (Crustacea, Amphipoda). Zoologica Scripta 45: 300–321. DOI 10.1111/zsc.12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wagner GP, Kin K, Lynch VJ (2012). Measurement of mRNA abundance using RNA-seq data: RPKM measure is inconsistent among samples. Theory in Biosciences 131: 281–285. DOI 10.1007/s12064-012-0162-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Whiteley NM, Taylor EW, Clarke A, Haj AJE (1997). Haemolymph oxygen transport and acid-base status in Glyptonotus antarcticus Eights. Polar Biology 18: 10–15. DOI 10.1007/s003000050153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Woods HA, Moran AL, Arango CP, Mullen L, Shields C (2009). Oxygen hypothesis of polar gigantism not supported by performance of Antarctic pycnogonids in hypoxia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 276: 1069–1075. DOI 10.1098/rspb.2008.1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |