DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.014338

www.techscience.com/journal/biocell

| Biocell DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.014338 |  www.techscience.com/journal/biocell |

| Article |

Visualization of integrin molecules by fluorescence imaging and techniques

1Department of Immunology, School of Medicine, UConn Health, Farmington, 06030, USA

2Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, 92093, USA

3Cardiovascular Institute of Zhengzhou University, Department of Cardiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450051, China

*Address correspondence to: Zhichao Fan, zfan@uchc.edu

Received: 18 September 2020; Accepted: 22 November 2020

Abstract: Integrin molecules are transmembrane αβ heterodimers involved in cell adhesion, trafficking, and signaling. Upon activation, integrins undergo dynamic conformational changes that regulate their affinity to ligands. The physiological functions and activation mechanisms of integrins have been heavily discussed in previous studies and reviews, but the fluorescence imaging techniques –which are powerful tools for biological studies– have not. Here we review the fluorescence labeling methods, imaging techniques, as well as Förster resonance energy transfer assays used to study integrin expression, localization, activation, and functions.

Keywords: Integrins; Fluorescence imaging; Fluorescence labeling; Live-cell imaging; Super-resolution imaging; Intravital imaging; FRET

Integrins are a family of adhesion receptors that are abundantly expressed in all cell types of metazoans except for erythrocytes. Their integral roles in mediating cell–cell and cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions make integrins indispensable for the existence of multicellular organisms. Interactions between integrins and their ligands trigger profound changes of the cytoskeleton and signaling apparatus during biological processes, such as adhesion (Evans et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2016; Stubb et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020a; Valencia-Gallardo et al., 2019), migration (Bernadskaya et al., 2019; Martens et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2014), proliferation (Clark et al., 2020; Erusappan et al., 2019), differentiation (Martins Cavaco et al., 2018; Schumacher et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2019), inflammation (Arnaout, 2016; Sun et al., 2020b), tumor invasion (Bui et al., 2019; Haeger et al., 2020), and metastasis (Fuentes et al., 2020; Howe et al., 2020; Osmani et al., 2019). Fine-tuned integrin signaling is crucial for cellular homeostasis, and abnormal integrin activities give rise to many pathological conditions, including autoimmune diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. Extensive efforts have been made to discover and develop molecules targeting integrins as potential means of therapy (Ley et al., 2016). Several integrin-targeting antibodies and synthetic compounds are approved for treating inflammatory diseases or are under investigation in clinical trials. Fluorescent imaging techniques provide a powerful tool for better understanding integrin structures and conformational changes (by Förster resonance energy transfer, conformational reporting antibody, and super-resolution imaging), and integrin-ligand interactions to develop more effective therapies for a vast array of diseases.

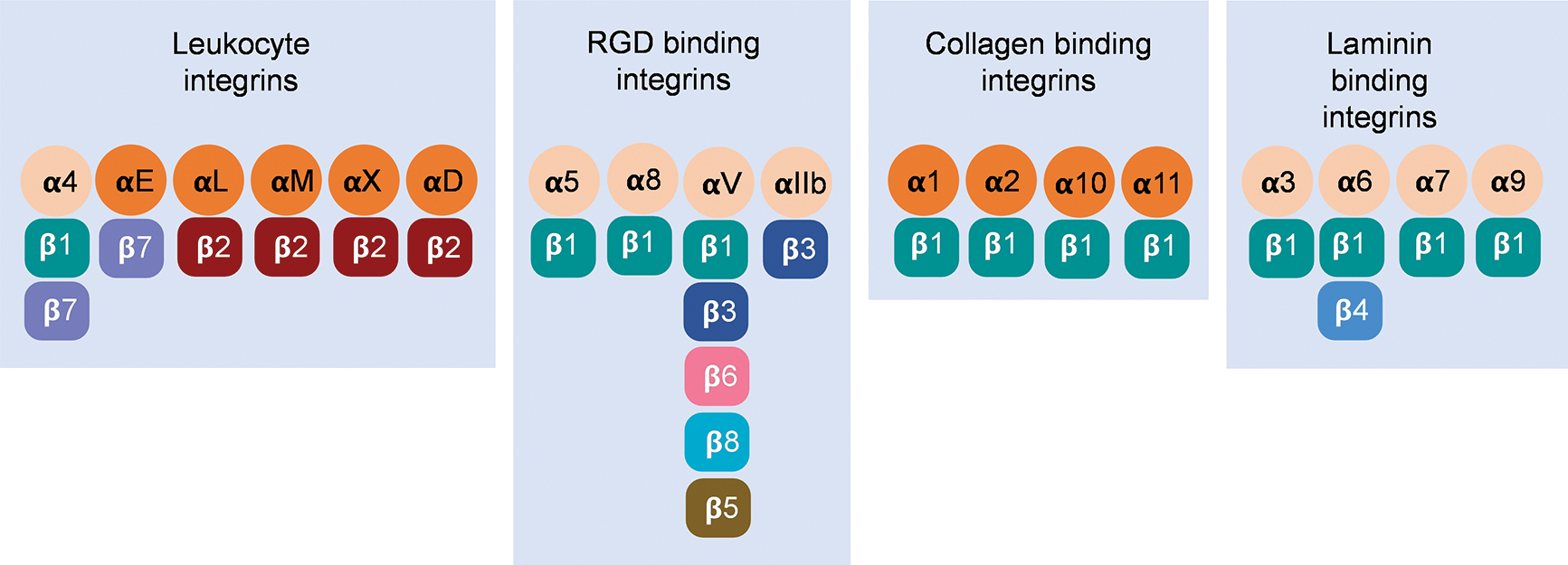

Integrins are heterodimers consisting of noncovalently associated α (120–180 kDa) and β (90–110 kDa) subunits (Hynes, 1992). In the vertebrates, 18 α subunits and 8 β subunits form 24 αβ pairs (Barczyk et al., 2010; Hynes, 2002) (Fig. 1). Integrin families are separated into four major categories: those with specificity for intercellular adhesion molecules and inflammatory ligands (leukocyte integrins, α4, αE, αL, αM, αX, and αD), Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motifs (αIIb, αV, α5, and α8), collagens (α1, α2, α10, and α11), and laminins (α3, α6, and α7) (Campbell and Humphries, 2011; Humphries et al., 2006; Tolomelli et al., 2017). Both α and β subunits are type I transmembrane glycoproteins containing a relatively large extracellular domain (ectodomain), a single transmembrane domain, and a short cytoplasmic tail (Arnaout, 2016; Campbell and Humphries, 2011; Fan and Ley, 2015; Luo et al., 2007).

The ectodomain is an asymmetric structure with a “head” carrying two “legs” (~16 nm long). The head consists of a predicted seven-bladed β-propeller domain (~60 amino acids each) of an α subunit (Xiao et al., 2004; Xiong et al., 2001) (nine of eighteen α subunits also contain an additional ~200 amino acids αA/αI domain) (Larson et al., 1989) and a ~250 amino acid βA/βI-like domain inserted in a hybrid domain of β subunit. The αA/αI domain and βA/βI-like domain are homologous to small ligand-binding von Willebrand Factor type A (vWFA) domain (Arnaout, 2002; Arnaout et al., 2007). The βA/βI-like domain contains two additional segments: one forms the interface with the β-propeller, and the other is a specificity-determining loop (SDL) mediating the ligand-binding (Luo et al., 2007). As structures of αVβ3 and αIIbβ3 showed, the α subunit leg domain is composed of an immunoglobulin-like “thigh” domain, a genu loop, and two similar β-sandwich domains named calf-1 and calf-2. The β subunit leg is formed by a plexin-semaphorin-integrin (PSI) domain, a hybrid domain (Bork et al., 1999), four tandem epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains, and a β-tail domain (βTD) (Bode et al., 1988; Janowski et al., 2001). The knee of the α subunit (α genu) lies at the junction between the thigh and calf-1 domains, and the knee of the β-subunit (β genu) is within the PSI and EGF1-2 region (Takagi and Springer, 2002). In integrins containing an αA/αI domain, ligand binding is mediated by this domain. As for integrins lacking the αA/αI domain, binding sites of ligands localize in the interface between β subunit β-I domain and α subunit β-propeller domain. Transmembrane domains of both α and β subunits are single α-helixes. NMR studies of αIIbβ3 show that the transmembrane domain of β3 is longer than αIIb and tilted with a ~25° angle to ensure the formation of inner and outer membrane clasp (IMC and OMC), which are important for proper integrin activity (Ginsberg, 2014; Kim et al., 2011; Lau et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2018).

Figure 1: Twenty-four αβ pairs of vertebrate integrins constituted by 18 α subunits and 8 β subunits have been classified into four separate groups.

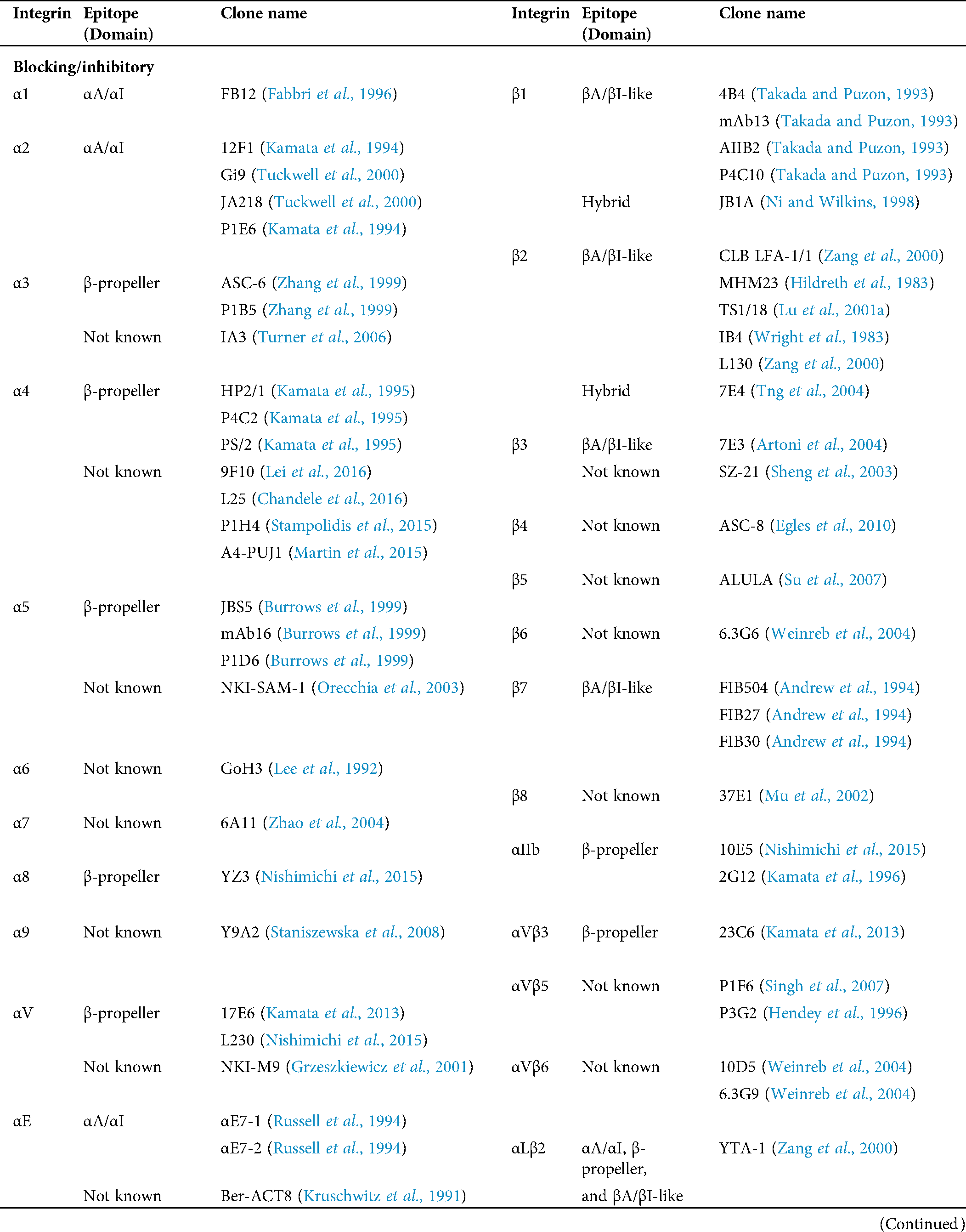

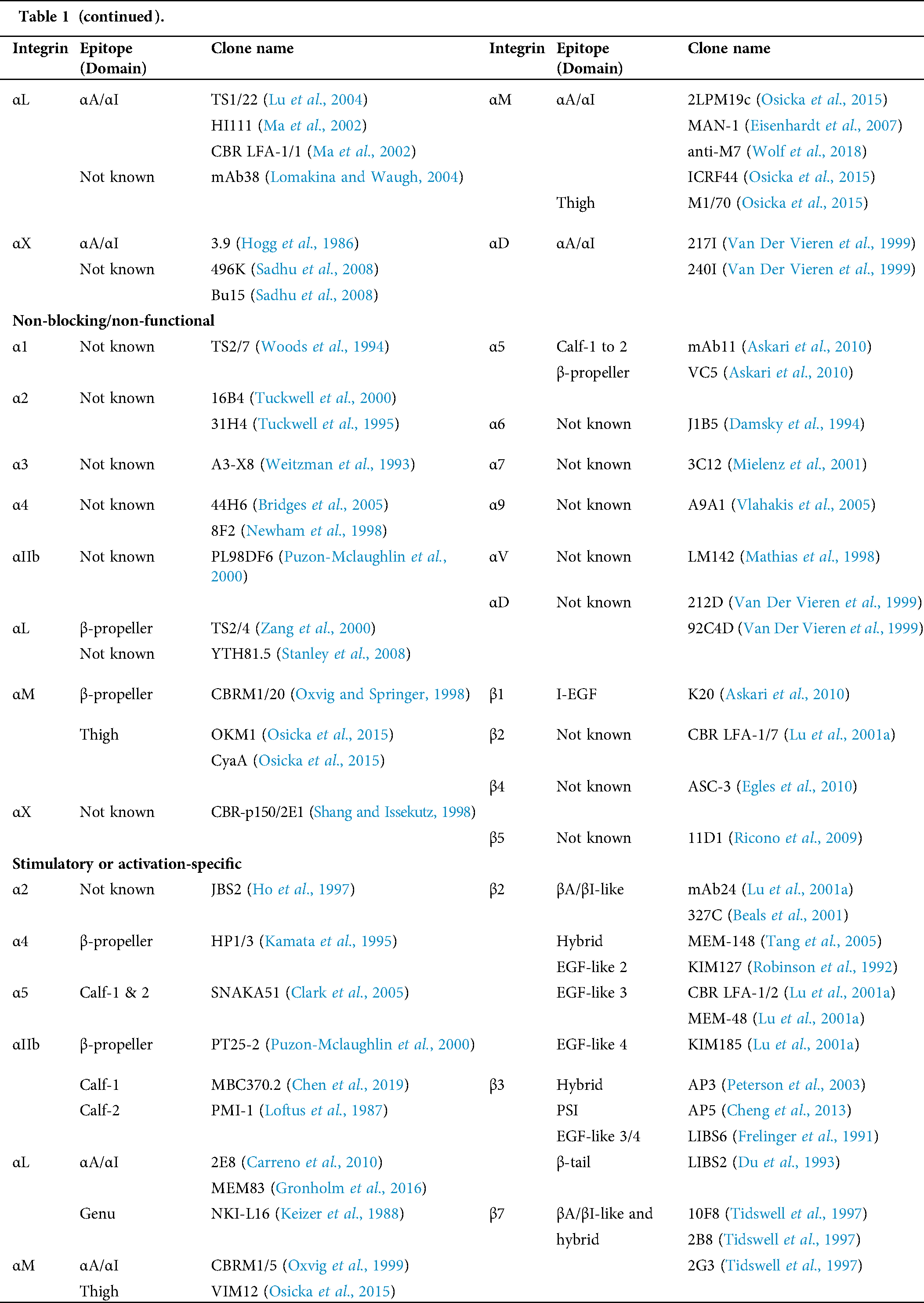

Table 1: Human integrin-targeting monoclonal antibodies

Many techniques have been applied to distinguish two major models of conformational changes influencing integrin affinity, namely “switchblade” (Luo et al., 2007) and “deadbolt” (Arnaout et al., 2005). Although height change is a conspicuous readout, no consistent conclusions have been drawn owing to the plasticity of integrin structure. Most studies of ectodomains favor the switchblade model: extension (E+) of the integrin is the prerequisite for rearrangement of the ligand-binding site, leading to high affinity (H+). Three major conformations with different ligand binding affinities provide evidence for this model: inactive bent ectodomain with low-affinity headpiece (E−H−), primed extended ectodomain with low-affinity headpiece (E+H−) with low affinity, and fully activated extended ectodomain with high-affinity headpiece (E+H+) (Chen et al., 2010; Springer and Dustin, 2012; Takagi et al., 2002). However, crystallography results showed that the conformations of bent ectodomain with open headpiece (E−H+) found in αvβ3 and αXβ2 (Sen et al., 2013) had the capacity to bind its ligand. In primary human neutrophils, the “switchblade” transition (E−H− to E+H− to E+H+) was observed. And an alternative transition from E−H− to E−H+ to E+H+ was also observed (Fan et al., 2016). E−H+ β2 integrins bind intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAMs) in cis (Fan et al., 2016) and form a face-to-face orientation (Fan et al., 2019), inhibiting leukocyte adhesion and aggregation (Fan et al., 2016). E−H+ αMβ2 integrins were shown binding FcγRIIA in cis to limit antibody-mediated neutrophil recruitment (Saggu et al., 2018). These findings suggest an alternative allosteric pathway other than the “switchblade” model.

Integrin labeling in fluorescence imaging

Immunofluorescent staining is the most commonly used method for integrin labeling, and antibody selection is extremely important for studying integrins. Monoclonal antibodies targeting different epitopes of specific integrin α and β subunits have been developed (Tab. 1). Some of these have been discussed in a previous review (Byron et al., 2009). Briefly, most of these clones target human integrins and can be classified into three categories: Blocking/inhibitory, non-blocking/non-functional, and stimulatory/activation specific. Blocking antibodies can be used in integrin loss-of-function assays, such as adhesion and phagocytosis, or testing integrin expression when there is no ligand binding, such as flow cytometry. Non-blocking antibodies do not interfere with the biological functions of integrins. Thus, they are useful in live-cell fluorescence imaging to monitor the expression, localization, and clustering of integrins when interacting with ligands (Ezratty et al., 2009; Garmy-Susini et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2009; Jamerson et al., 2012; Shao et al., 2019; Tchaicha et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2019). Among integrin antibodies, a unique kind of integrin antibody recognizes epitopes only expressed when integrins are activated or inactivated. Some of them further stabilize certain conformation(s) by steric effect resulting in enhancement or attenuation of ligand binding. Immunofluorescent imaging using antibodies with different effects on integrin activation can help illuminate novel biological functions.

Integrin antibodies that recognize activated epitopes have been applied to understanding β2 integrins-leukocyte-specific integrins that are critical for leukocyte recruitment and functions. Monoclonal antibody KIM127 (Robinson et al., 1992) recognizes the cysteine-rich repeat residues in the stalk region of integrin β2 subunits (Lu et al., 2001a). Monoclonal antibody mAb24 (Dransfield and Hogg, 1989) recognizes Glu173 and Glu175 within the CPNKEKEC sequence (residues 169–176) of the β2 I domain (Kamata et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2001b). These epitopes are shielded by the stalk region, and the αA/αI domain or the β-propeller of integrin α subunit are exposed and recognized by KIM127 and mAb24 upon integrin activation. KIM127 binding indicates integrin extension (E+), and mAb24 binding indicates rearrangement in the ligand-binding site leading to high-affinity (H+) (Kuwano et al., 2010; Lefort et al., 2012; Sorio et al., 2016). Owing to noninterference with each other (Fan et al., 2016), KIM127 and mAb24 were used to label different conformational states of β2 integrin on live human neutrophils (Fan et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2020a; Wen et al., 2020b), which enables to distinguish E+H−, E−H+, and E+H+ β2 integrins in live cells and. These studies demonstrated that other than the canonical switchblade model (E−H− to E+H− to E+H+), an alternative integrin activation pathway (E−H− to E−H+ to E+H+) exists on primary human neutrophils. Monoclonal antibody 327C has been mapped to the upstream C-terminal region between amino acids 23 and 411 of the β2 integrin and also reports β2 integrin H+ (Zhang et al., 2008). 327C has been used to monitor β2 integrin activation during neutrophil migration (Green et al., 2006) and T cell spreading (Feigelson et al., 2010) using epifluorescence imaging, and neutrophil-platelet interaction using confocal microscopy (Evangelista et al., 2007).

Antibodies for activated integrins have also been used to study β1 integrins, which are expressed on various cells, such as leukocytes (Rullo et al., 2012; Werr et al., 1998), endothelial cells (Xanthis et al., 2019), epithelial cells (Spiess et al., 2018), and fibroblasts (Samarelli et al., 2020), and they are critical for several cell functions, such as adhesion and migration. Monoclonal antibody 9EG7 binds to the upper portion of the lower β-leg, which is approximately within the I-EGF2 domain, and reports β1 integrin extension (Lenter et al., 1993; Su et al., 2016) similar to KIM127 binding in β2 integrin. Antibody 12G10 binds to the βI domain of high-affinity β1 integrin (Su et al., 2016), which is similar to mAb24 binding in β2 integrin. Using 9EG7, 12G10, and a pan-β1 integrin antibody AIIB2, distinct nanoclusters of active and inactive β1 integrins have been identified in focal adhesions (FAs) (Spiess et al., 2018). Antibody TS2/16 binds an epitope similar to what 12G10 binds, where it activates and appears to stabilize an H+ βI domain conformation without requiring extension or hybrid domain swing-out (Van De Wiel-Van Kemenade et al., 1992). Antibodies HUTS-4, HUTS-7, and HUTS-21 recognize overlapping epitopes located in the hybrid domains of the β1 subunit. Their expressions parallel the ligand-binding activity of β1 integrins induced by various extracellular and intracellular stimuli (Luque et al., 1996; Su et al., 2016).

Antibodies recognizing and binding to the inactive conformation or that inhibit function are also used for integrin labeling. mAb13 recognizes an epitope within the βI domain of β1 integrin and is dramatically attenuated in the ligand-occupied form of α5β1. The binding of mAb13 to ligand-occupied α5β1 induces a conformational change in the integrin, resulting in the displacement of the ligand (Mould et al., 1996). Antibody SG/19 has been reported to inhibit the function of the β1 integrin on the cell surface. SG/19 recognizes the wild-type β1 subunit that exists in a conformational equilibrium between the high and low-affinity states but binds poorly to a mutant β1 integrin that is locked in a high-affinity state. SG/19 binds Thr82 located at the outer face of the boundary between the I-like and hybrid domains of the β1 subunit. SG/19 attenuates the ligand-binding function by restricting the conformational shift to the high-affinity state involving the swing-out of the hybrid domain without directly interfering with ligand docking (Luo et al., 2004). Monoclonal antibody SNAKA51 binds to the calf-1/calf-2 domains of the α5 subunit when the α5β1 integrin is active (Su et al., 2016). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated SNAKA51 facilitates the detection of a conformation that promotes fibrillar adhesion formation. Gated stimulated emission depletion (g-STED) confocal microscopy analyses of PPFIA1 (protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type F polypeptide interacting protein α1) and SNAKA51 activating α5β1 integrin in endothelial cells indicates that PPFIA1 localizes close to both focal and fibrillar adhesions (Mana et al., 2016).

β3 integrins are also widely expressed, and antibodies have been developed to study their functions. Vitronectin receptor integrin αVβ3 is expressed on leukocytes (Antonov et al., 2011), endothelial cells (Liao et al., 2017), and platelets (Bagi et al., 2019), etc. Active and inactive conformations of αVβ3 integrins can be detected by antibodies anti-αVβ3 clone LM609 and clone CBL544, respectively (Drake et al., 1995). WOW-1 is a ligand-mimic Fab fragment that reports αVβ3 integrin activation (Pampori et al., 1999). It has been used in detecting αVβ3 integrin activation on endothelial cells during shear sensing (Tzima et al., 2001) and migration (Lu et al., 2006) using fluorescence imaging. αIIbβ3 integrins are also known as glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and expressed on platelets (Adair et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2019; Ting et al., 2019). Antibody MBC370.2 binds to the calf-1 domain of the αIIb chain and reports the E+ of αIIbβ3 integrins (Zhang et al., 2013). PAC-1 is a ligand-mimic antibody and binds to both the β-propeller and βA/βI-like domains of H+ αIIbβ3 integrins (Kashiwagi et al., 1997). AP5 recognizes an epitope in the β3 PSI domain and reports hybrid domain swing-out (Cheng et al., 2013). By using these three antibodies, it has been demonstrated that biomechanical platelet aggregation is mediated by E+ but not H+ of αIIbβ3 integrins (Chen et al., 2019).

Integrin α4β7 is a lymphocyte homing receptor that mediates both rolling and firm adhesion of lymphocytes on vascular endothelium, two of the critical steps in lymphocyte migration and tissue-specific homing (Berlin et al., 1993; Iwata et al., 2004). Integrin α4β7 is the target of the most successful integrin drug vedolizumab, which is a human-derived blocking antibody and has recently proven useful in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (Fedyk et al., 2012; Ley et al., 2016; Sands et al., 2019; Zingone et al., 2020). An activation-specific antibody J19 for integrin α4β7 has been developed (Qi et al., 2012). This antibody does not block the mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 (MAdCAM-1) binding site. Its binding site has been mapped to Ser-331, Ala-332, and Ala-333 of the β7 A/I-like domain and a seven-residue segment from 184 to 190 of the α4 β-propeller domain.

Since the molecular cloning of green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria (Chalfie et al., 1994; Prasher et al., 1992; Ward et al., 1980), a wide spectrum of fluorescent proteins have provided excellent opportunities to monitor integrin localization and dynamics in living cells and tissues.

To study the separation of integrin α and β “legs” during activation, the monomeric cyan fluorescent protein (mCFP) and monomeric yellow fluorescent protein (mYFP) were fused to the C-termini of the α and β cytoplasmic domains of αVβ3, respectively (Kim et al., 2003). The “leg” separation was demonstrated by the decrease of Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) from mCFP to mYFP. A similar strategy has been applied to study αMβ2 integrin activation as well (Lefort et al., 2009). To extend this idea in studying integrin activation in mouse disease models, knock-in (KI) mice with αM-mYFP (Lim et al., 2015), αL-mYFP (Capece et al., 2017), or β2-mCFP (Hyun et al., 2012) were generated, in which the fluorescent proteins were inserted into the C terminus of each integrin. Intravital imaging was then performed to visualize αM-mYFP+ leukocytes (Lim et al., 2015) or β2-mCFP leukocytes (Hyun et al., 2012) within inflamed or infected tissues. The αL-mYFP KI mice helped reveal an intracellular pool of integrin αLβ2 involved in CD8+ T cell activation and differentiation (Capece et al., 2017). In combined KI mice, activation of αLβ2 and αMβ2 was observed during neutrophil transendothelial migration by intravital microscopy (IVM) (Hyun et al., 2019).

In another study, GFP was inserted into the β3-β4 loop of blade 4 of the αL integrin β-propeller domain with no appreciable influence on integrin function and conformational regulation (Nordenfelt et al., 2017). The orientation of GFP can be measured by emission anisotropy microscopy (Ghosh et al., 2012; Nordenfelt et al., 2017; Ojha et al., 2020). Thus, they found that the direction of actin flow dictates integrin αLβ2 orientation during leukocyte migration (Nordenfelt et al., 2017). The role of α5 integrins in cell adhesion and migration was investigated by introducing the eukaryotic expression vectors pEGFP-N3, pECFP-N1, and pEYFP-N1 inserted with the integrin α5 cDNA and a 10-13 amino acid linker into CHO K1 and CHO B2 (α5-deficient) cells (Laukaitis et al., 2001). They found that α5 integrins stabilized cell adhesion and formed visible complexes after the arrival of α-actinin and paxillin. Integrin β4-YFP fusion proteins were introduced into HaCat cells as a marker of hemidesmosome protein complexes (HPCs). Meanwhile, CFP-tagged α-actinin was used as a marker of focal contacts (FCs). Tight co-regulation of HPCs and FCs was detected in keratinocytes undergoing migration during wound healing (Ozawa et al., 2010). Wild type or mutated mouse integrin β3-EGFP fusion protein was used to investigate the mechanisms and dynamics of the clustering and incorporation of activated αVβ3 integrins into FAs in living cells. Formation of the ternary complex consisting of activated integrins, immobilized ligands, talin, and PI(4,5)P2 was found to contribute to integrin clustering (Cluzel et al., 2005). Fluoppi is a technology providing an easy way to visualize protein-protein interactions (PPIs) with a high signal-to-background ratio (Koyano et al., 2014; Yamano et al., 2015). It employs an oligomeric assembly helper tag (Ash-tag) and a tetrameric fluorescent protein tag (FP-tag) to create detectable fluorescent foci when there are interactions between two proteins fused to the tags. This technique has been used to prove the interaction of integrin β1 and Procollagen-Lysine, 2-Oxoglutarate 5-Dioxygenase 2 (PLOD2) in cell migration (Ueki et al., 2020).

In another study, an extracellular site of integrin β1 was reported suitable for inserting different tags, including GFP and PH-sensitive pHluorin (Huet-Calderwood et al., 2017). pHluorin is a GFP variant that displays a bimodal excitation spectrum with peaks at 395 and 475 nm and an emission maximum at 509 nm. Upon acidification, pHluorin excitation at 395 nm decreases with a corresponding increase in the excitation at 475 nm (Mahon, 2011). In this study, pHluorin tagged integrin β1 was used to monitor the exocytosis of β1 integrins in live cells. Since similar extracellular fluorescence protein insertion was performed in β2 integrins (Bonasio et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2018; Nordenfelt et al., 2017), it is feasible to use pHluorin in study β2 integrin functions, such as degranulation and phagocytosis.

Other methods for fluorescently tagging integrins

HaloTag is a 34 kDa engineered, catalytically inactive derivative of a bacterial hydrolase. It can be fused to a protein of interest and covalently bound by synthetic HaloTag ligands with high specificity. A covalent bond can form rapidly under physiological conditions and is essentially irreversible. HaloTag allows adaptation of the targeted protein to different experimental requirements without altering the genetic construct (Los et al., 2008; Los and Wood, 2007). For example, Atto655 was used to generate the HaloTag655 ligand, which is suitable for labeling live cells by expressing a β1-integrin-HaloTag fusion protein. The resulting living cells are suitable for STED microscopy, and intracellular distribution of the β1-integrin such as filopodia and endocytic vesicles were studied in unprecedented detail (Schroder et al., 2009). Halo and SNAP tags were also inserted into the β1 integrin extracellular domain in the study mentioned above (Huet-Calderwood et al., 2017). Similar to HaloTag, SNAP (Keppler et al., 2003) is also a self-labeling protein tag that can covalently bind to synthetic fluorescence dyes. Sequential fluorescence dye labeling of Halo-tagged integrin β1 can distinguish surface and internal β1 integrins in cells (Huet-Calderwood et al., 2017).

Many integrins bind to ECM molecules through an RGD motif. RGD peptide was found to bind to resting integrins and induce integrin activation. Compared to linear peptides, suitable optimized cyclic RGD (cRGD) peptides interact with integrins in a more selective manner and with higher affinity (Weide et al., 2007). Changing a three-dimensional structure or modifying the amino acid sequences flanking the RGD motif can enhance its ligand selectivity (Schaffner and Dard, 2003). Within this area, integrin αVβ3 was studied most extensively for its role in tumor growth, progression, and angiogenesis. It was considered an interesting biological target for therapeutic cancer drugs and a diagnostic molecular imaging probe (Ye and Chen, 2011). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated dimeric cRGD peptides (FITC-RGD2, FITC-3P-RGD2, and FITC-GalactoRGD2) were used as fluorescent probes for in vitro assays of integrin αvβ3/αvβ5 expression in tumor tissues (Zheng et al., 2014). Quantum dots (QDs) are fluorescent nanocrystals that absorb a wide-range spectrum (400–650 nm) of light and emit a narrow symmetric spectrum of bright fluorescence. These allow the QD signal to be clearly distinguished from the cellular autofluorescence background (Alivisatos et al., 2005; Gao et al., 2005; Michalet et al., 2005; Pinaud et al., 2006). cRGD peptides and a biotin-streptavidin linkage are used to specifically couple individual QDs to αVβ3 integrins on living osteoblast cells. The positions of individual QDs were tracked with nanometer precision, and localized diffusive behavior was observed (Lieleg et al., 2007). Near-infrared (650–900 nm) fluorescence imaging has provided an effective solution for improving the imaging depth along with sensitivity and specificity by minimizing the autofluorescence of some endogenous absorbers (Shah and Weissleder, 2005; Tung, 2004). Cyanine analogs, such as Cy5, Cy5.5, were used to label cyclic RGD analogs for in vivo optical imaging of integrin αVβ3 positive tumors with high contrast in mice (Jin et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2004).

The C-terminal region of the fibrinogen γ subunit contains γC peptide uniquely binding to activated or primed αIIbβ3 integrin at the interface between α and β subunits (Hantgan et al., 2006; Springer et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2016). Therefore, it may serve as the prototype for the design of a probe targeting activated αIIbβ3 integrin. Gold nanoclusters are a newly developed class of fluorescent particles. The gold nanocluster Au18 conjugated with γC peptide peptides were used to detect αIIbβ3 in HEL with an excitation wavelength of 514 nm and an emission wavelength of 650 nm (Zhao et al., 2016). Due to the specific binding between the Leu-Asp-Val (LDV) peptide and integrin α4β1, fluorophore-conjugated LDV is commonly used to monitor changes of α4β1 integrin conformation or affinity in live cells (Chigaev et al., 2001; Chigaev et al., 2011b). LDV-FITC can be used as a FRET donor to reveal conformational changes of α4β1 under different biological conditions (Chigaev et al., 2003b; Chigaev et al., 2004; Njus et al., 2009).

Soluble ligands ICAM-1 (Lefort et al., 2012; Margraf et al., 2020), vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM-1) (Sun et al., 2014), and MadCAM-1 (Sun et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2014) were used to detect the activation of β2, β1, and β7 integrins. In the classic article imaging the immunological synapse (Grakoui et al., 1999), Cy5-labeled ICAM-1 were anchored to the bilayer in a manner that allows their free diffusion in the supported bilayer to monitor the dynamic changes of integrin αLβ2 activation and distribution during the formation of the immunological synapse. A similar approach became a canonical method to study integrins in immunological synapses (Kaizuka et al., 2007; Kondo et al., 2017; Somersalo et al., 2004) and was also used to track active integrin αLβ2 in leukocyte migration (Smith et al., 2005).

Fluorophore-conjugated integrin allosteric antagonists and agonists are also widely used to label certain integrins. BIRT 377 and XVA-143 are integrin αLβ2-specific allosteric antagonists that belong to two distinct classes. The BIRT 377 binding site is located within the I domain of the αL integrin subunit. The XVA-143 site is located between the αL β-propeller and the β2 subunit I–like domain (Shimaoka and Springer, 2003). BIRT- and XVA-FITC were used to study conformational changes of integrin αLβ2 (Chigaev et al., 2015). A ligand-mimic small molecular probe has been developed to measure integrin αLβ2 activation (Chigaev et al., 2011a).

Live-cell imaging of integrins

Live-cell imaging has been abundantly used in biological studies, including some for integrins. This method has given rise to tremendous progress in documenting dynamic cellular processes, such as cell adhesion (Fan et al., 2016; Morikis et al., 2017; Morikis et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020a; Sun et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2020b; Yago et al., 2015; Yago et al., 2018), migration (Kostelnik et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2018; Nordenfelt et al., 2017; Panicker et al., 2020; Ramadass et al., 2019; Tweedy et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020), cell-cell interactions (Hanna et al., 2019; Kretschmer et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2015a; Lin et al., 2015b; Omsland et al., 2018; Zucchetti et al., 2019), endocytosis/phagocytosis (Chu et al., 2020; Freeman et al., 2020; Levin-Konigsberg et al., 2019; Ostrowski et al., 2019; Walpole et al., 2020), exocytosis/degranulation (Cohen et al., 2015; Thiam et al., 2020), and cytoskeleton rearrangement (Balint et al., 2013; Ostrowski et al., 2019; Walpole et al., 2020), in real-time and down to the single molecular level (Balint et al., 2013; Katz et al., 2017; Katz et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2018; Mylvaganam et al., 2020). Fluorescent probes and proteins have been ubiquitously utilized in live-cell imaging, allowing observation of dynamics and function of cellular structures and macromolecules, such as integrins, over time and in-depth.

In epifluorescence microscopy, which is the most commonly used wide-field microscopy, all the emission light around the focal plane captured by the objective, which depends on its numerical aperture, is sent to the detector leading to high light-collecting efficiency. The use of the pinhole in confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) decreases the background signal from out-of-focus light and increases the signal-to-background ratio. However, CLSM is limited by phototoxicity/photobleaching. This is mainly due to that most confocal microscopes have detectors with low quantum efficiency, such as photomultiplier tubes (PMT), in comparison to epifluorescence microscopes, such as charge-coupled device (CCD) or complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) cameras. Thus, to acquire images of similar brightness, CLSM needs higher power of the excitation light than epifluorescence microscopy. On the other hand, most CLSM setting has a limited imaging speed due to its scanner. For example, most CLSM has a laser dwell time of ≥1 µs per pixel (Straub et al., 2020), which means that it will take more than 0.25 seconds to acquire a 512 × 512 image (≤4 frames per second). In comparison, most cameras in epifluorescence microscopes allow an imaging speed of ≥20 frames per second (1280 × 1024 pixels). The low speed of CLSM can be overcome by using a high-cost resonant scanner, which allows a speed of 30 fps for 512 × 512 images. Thus, if the specimen is a monolayer, epifluorescence microscopy might be a good choice (Stephens and Allan, 2003; Waters, 2007).

Epifluorescence microscopy has been used to monitor β2 integrin activation during leukocyte rolling on selectins (Kuwano et al., 2010). In the study developing the integrin αL-mYFP mice, an intracellular pool of αL integrins was discovered in CD8+ T cells using epifluorescence microscopy (Capece et al., 2017). In the study of the integrin αM-mYFP mice, epifluorescence images showed that αM integrins enriched in the lamellipodia during neutrophil migration (Lim et al., 2015). Epifluorescence-based live-cell fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM)-FRET has been used to demonstrate the cis interaction between sialylated FcγRIIA and the αI-domain of integrin αMβ2 (Saggu et al., 2018). In another study, epifluorescence imaging of platelet integrin αIIbβ3 showed that biomechanical platelet aggregation in disturbed flow is mediated by E+H− αIIbβ3 integrins (Chen et al., 2019).

For thicker (e.g., 20–100 µm) live-cell specimens, CLSM was used for imaging integrins (Fan et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2015a; Lock et al., 2018; Sahgal et al., 2019; Schymeinsky et al., 2009). For example, the distribution of integrin αLβ2 during immunological synapse formation was visualized using CLSM (Lin et al., 2015a). Imaging by CLSM, Integrin αVβ5 was found to forms novel talin- and vinculin-negative reticular adhesion structures, which may be required for mediating attachment during mitosis (Lock et al., 2018). CLSM was also used to investigate the recycling of active β1 integrins regulated by GGA2 and RAB13 (Sahgal et al., 2019). CLSM imaging of β2 integrins illustrated the role of mAbp1 in regulating β2 integrin-mediated phagocytosis and adhesion (Schymeinsky et al., 2009). CLSM helped to show the distribution of active β2 integrins during lymphocyte migration, and roles of talin, ZAP-70, rap2, and SHARPIN during lymphocyte migration (Evans et al., 2011; Pouwels et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2005; Stanley et al., 2008; Stanley et al., 2012)

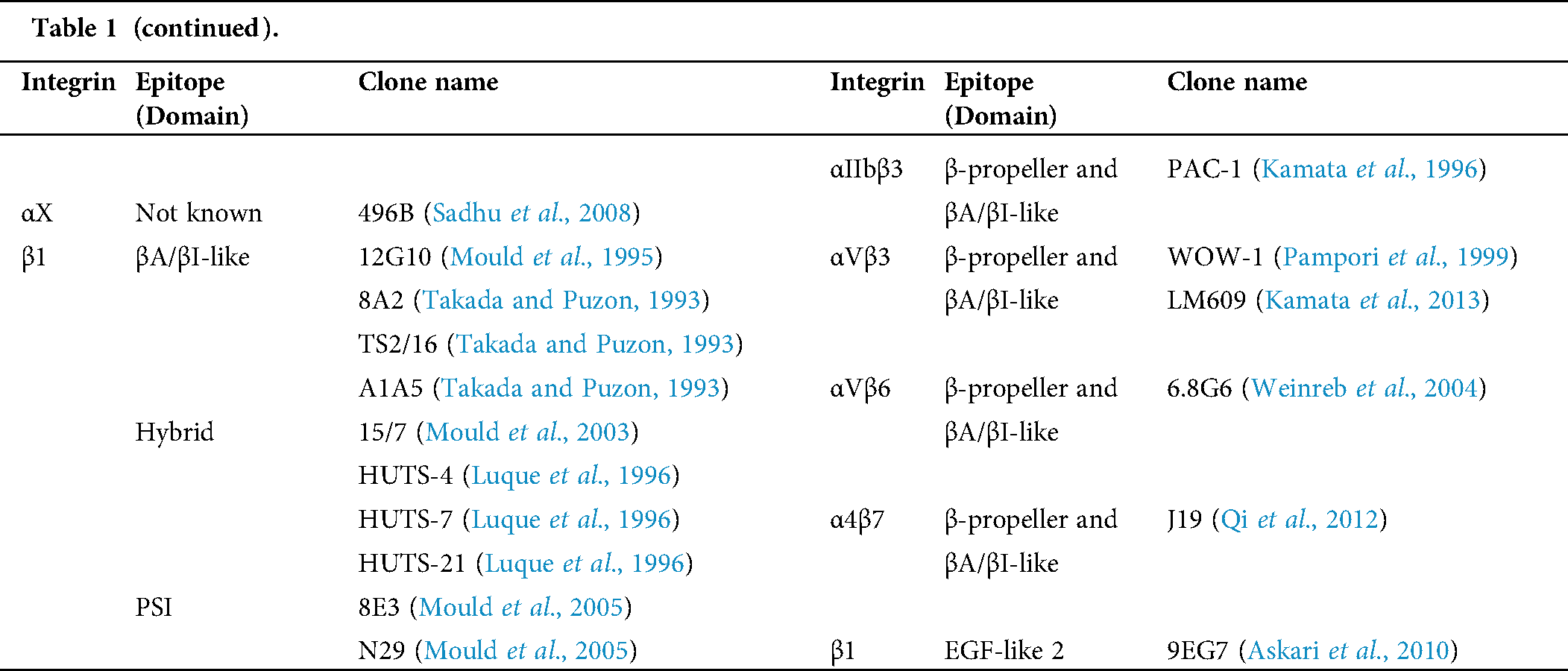

Figure 2: Schematics of qDF (quantitative dynamic footprinting) microscopy.

However, the slower imaging speed and higher phototoxicity limit its usage for live-cell imaging. There are some implementations that significantly increase imaging speed and reduce phototoxicity under the condition of CLSM. Such implementations include slit scanning and pinhole multiplexing methods, including spinning disk confocal microscopy (SDCM) (Graf et al., 2005; Maddox et al., 2003). In addition to the fundamental disk containing thousands of pinholes in a spiral, there is a second collector disk with a matching pattern of microlenses focusing excitation light with up to 70% efficiency onto the imaging pinholes. In combination with an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (CCD) detector, SDCM turns to be an ideal solution for fast live-cell confocal imaging of thicker specimens (Wang et al., 2005). Using SDCM, it was found that ADP-ribosylation factor 6 directs the traffic of α9 and β1 integrins on dorsal root ganglion neurons (Eva et al., 2012). The dynamic changes of β5 integrins were visualized by SDCM during mitosis, which suggested that a selective role for integrin β5 in mitotic cell attachment (Lock et al., 2018). In another study, it was found that phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate binder Rasa3 was translocated to integrin αIIbβ3 and involved in the integrin outside-in signaling on platelets during α-thrombin stimulation (Battram et al., 2017).

Another high-resolution live-cell imaging technique is total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. In TIRF microscopy, a laser incident beam illuminating the boundary between two media of different refractive indices (usually the coverslip and the specimen) experiences total internal reflection. The totally internally reflected laser beam generates the evanescent wave, which excites fluorophores that are in the vicinity of the coverslip-specimen interface (~100–200 nm), resulting in a very high signal-to-background image with a ~100 nm optical section compared to ~700 nm of confocal or wide-field (Axelrod, 1981, 2001; Hocde et al., 2009). The high signal-to-background is at the cost of penetration. TIRF can only reveal structures close to the coverslip surface, such as membrane proteins and FAs. As a family of membrane proteins, integrin molecules are highly suitable for analysis with TIRF microscopy. Almost all integrin molecules have been monitored by TIRF microscopy. By using TIRF, it has been shown that FA disassembly during cell migration requires endocytosis of β1 integrins, which is regulated by clathrin (Chao and Kunz, 2009). TIRF imaging also showed that mechanical stimuli disassemble β1 integrin clusters and enhance endocytosis of integrins expressed on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Kiyoshima et al., 2011). H+ β2 integrins reported by monoclonal antibody 327C have been imaged by TIRF microscopy during neutrophil arrest and demonstrated that H+ β2 integrin-ICAM-1 binding initiates calcium influx (Dixit et al., 2011), and kindlin-3 is responsible for β2 integrin H+ (Dixit et al., 2012). H+ β2 integrins can also be reported by mAb24 (Dransfield and Hogg, 1989; Kamata et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2001b), as mentioned before. By using TIRF microscopy, the H+ β2 integrins were found polarized to the lead-edge during T cell migration (Hornung et al., 2020). It has also been demonstrated that β2 integrins form podosomes of dendritic cells imaged by TIRF microscopy (Gawden-Bone et al., 2014). In another study, a Rap1-GTP-interacting adapter molecule (RIAM)/lamellipodin-talin-integrin (β3) complex that guides cell migration was discovered by using TIRF microscopy (Lagarrigue et al., 2015). The transport of β3 to FA has been imaged by TIRF microscopy and was found to be regulated by an AAK1L- and EHD3-dependent rapid-recycling pathway (Waxmonsky and Conner, 2013). The PDK1-mediated endocytosis of β3 integrin during FA disassembly has also been monitored by TIRF microscopy (Di Blasio et al., 2015).

As an update to TIRF microscopy, quantitative dynamic footprinting (qDF) microscopy was developed in 2010 (Sundd et al., 2010), based on the calculation of the evanescent wave intensity and the fluorescence signals of the cell membrane. In the development of qDF microscopy, a two-step calibration procedure involved: (1) The distance of the closest approach of a stationary neutrophil with the coverslip was measured using variable angle TIRF microscopy and was designated Δ0 (Suppl. Fig. 3 in Sundd et al. (2010)); and (2) The z-distance (Δ) of any region in the neutrophil footprint is calculated by fluorescence intensity using the following equation, Δ = Δ0 + λ/4π × (n12 × sin2 θ − n22)−1/2 × ln (IFmax(θ)/IF(θ)). Fig. 2 described the Δ0 and Δ (Two examples Δ1 and Δ2 are shown). In this equation, λ is the wavelength of the emission light, and n1 and n2 are the refractive indexes of the two medium types, such as glass coverslip and cell, respectively. qDF microscopy was used to reveal neutrophil rolling under high shear stress (Sundd et al., 2010; Sundd and Ley, 2013) and was used in monitoring the dynamics of β2 integrin activation during human neutrophil arrest (Fan et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2016). By combining qDF with conformational reporting antibodies KIM127 (Lu et al., 2001a; Robinson et al., 1992) and mAb24 (Dransfield and Hogg, 1989; Kamata et al., 2002; Lu et al., 2001b), the canonical switchblade model of β2 integrin activation (Luo et al., 2007) was confirmed (Fan et al., 2016). Meanwhile, an unexpected E−H+ conformation of β2 integrins was observed, which suggested an alternative pathway of β2 integrin activation that E−H− integrins can acquire high-affinity first (E−H+) and then extended (E+H+). The E−H+ β2 integrins can bind ICAM ligands expressed on the same neutrophil in cis and inhibit integrin activation and neutrophil adhesion (Fan et al., 2016).

Super-resolution imaging of integrins

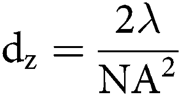

The spatial resolution of microscopic techniques is limited by Abbe’s law, according to which the highest achievable lateral and axial resolution (dx,y and dz), or diffraction limits, can be:

in which λ is the wavelength of the excitation beam, and NA is the numerical aperture of the microscope objective.  , with n being the refractive index of the medium and α being the half-cone angle of the focused light produced by the objective (Abbe, 1881; Hon, 1882). For example, in a conventional microscope, when a specimen is excited by blue-green light whose wavelength is about 488–550 nm, and an oil immersion objective with NA = 1.40 is used, lateral and axial resolution can be ∼200 nm and ∼500 nm, respectively (Thompson et al., 2002). Abbe’s law holds only true for wide-field microscopes.

, with n being the refractive index of the medium and α being the half-cone angle of the focused light produced by the objective (Abbe, 1881; Hon, 1882). For example, in a conventional microscope, when a specimen is excited by blue-green light whose wavelength is about 488–550 nm, and an oil immersion objective with NA = 1.40 is used, lateral and axial resolution can be ∼200 nm and ∼500 nm, respectively (Thompson et al., 2002). Abbe’s law holds only true for wide-field microscopes.

Table 2: Claimed resolution of super-resolution microscopy used in integrin imaging

Several super-resolution techniques circumvent the limits of diffraction and increase both lateral and axial resolution. One approach beyond the limit of diffraction is to sharpen the point-spread function of the microscope by spatially patterned excitation, including STED (Hell and Wichmann, 1994; Klar et al., 2000), reversible saturable optically linear fluorescence transitions (RESOLFT) (Hell, 2003, 2007, 2009; Hofmann et al., 2005), structured-illumination microscopy (SIM) (Gustafsson, 2000), and saturated structured-illumination microscopy (SSIM) (Gustafsson, 2005). Another is a pointillist approach that requires localization of individual fluorescent molecules (single-molecule localization microscopy, SMLM), such as stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) (Rust et al., 2006), photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) (Betzig et al., 2006), fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy (fPALM) (Hess et al., 2006), points accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography (PAINT) (Sharonov and Hochstrasser, 2006), ground-state depletion (GSD) microscopy (Folling et al., 2008). Expansion microscopy (ExM) expands the sample using a polymer system. Positions of labeled molecules were measured by using conventional microscopes. Based on the factor of expansion, the localization of these molecules in the unexpanded cells can be calculated back to achieve nanoscale resolution (Chen et al., 2015). Several super-resolution microscopy techniques have been summarized before (Galbraith and Galbraith, 2011; Pujals et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2020a), but some will be described here in more detail (Tab. 2).

Super-resolution imaging techniques have been used to study integrin molecules in recent years. Interferometric photoactivation and localization microscopy (iPALM) was used to visualize the three-dimensional structure of FAs, which includes the integrin αV and paxillin-enriched integrin signaling layer, the talin and vinculin-enriched force transduction layer, and zyxin and vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein-enriched actin regulatory layer (Kanchanawong et al., 2010). SIM was used to illustrate the linear β1 integrin distribution in FAs (Hu et al., 2015). Using a new super-resolution imaging technique with a similar principle to PALM, signal molecular tracking of β1 and β3 integrin molecules was performed, and they were found entering and exiting from FAs and repeatedly exhibiting temporary immobilizations (Tsunoyama et al., 2018). Using both STED and STORM microscopy, both active and inactive β1 integrins were visualized in FAs and were found segregating into distinct nanoclusters (Spiess et al., 2018). STED was also used in testing the colocalization of active α5β1 integrins and PPFIA1 to demonstrate the role of PPFIA1 in active α5β1 integrin recycling. In another study, both active β1 and β5 integrins were found separately located in FAs (Stubb et al., 2019) by Airyscan confocal microscopy, a super-resolution technique with similar resolution compared to SIM (Huff, 2015). Airyscan confocal microscopy utilized a 32-channel gallium arsenide phosphide photomultiplier tube (GaAsP-PMT) area detector that collects a pinhole-plane image at every scan position. Each detector element functions as a single, very small pinhole. Knowledge about the beam path and the spatial distribution of each detector channel enables very light-efficient imaging with improved resolution and signal-to-noise ratio. αV and β5 integrins in FAs were also imaged by iPALM in this study. Airyscan confocal microscopy was also used to identify the colocalization of GGA2, RAB13, and active β1-integrins to demonstrate the role of GGA2 and RAB13 in β1-integrin recycling (Sahgal et al., 2019), and image the localization of α11 and β1 integrins on mammary gland stromal fibroblast spreading on collagen (Lerche et al., 2020). GSD microscopy was used to visualize the LPS-induced colocalization of chloride intracellular channel protein 4 (CLIC4) and β1 integrins, demonstrating the role of CLIC4 in cell adhesion and β1 integrin trafficking (Argenzio et al., 2014). By using iPALM, the extension of αLβ2 integrins was monitored by the axial movement of the αLβ2 headpiece towards the coating substrate during Jurkat T cell migration (Moore et al., 2018). Using Fab fragments of mAb24 and KIM127, the distribution of E−H+, E+H−, and E+H+ β2 integrins on neutrophil footprint during arrest was visualized by STORM (Fan et al., 2019). Combined with molecular modeling, the SuperSTORM technique was developed (Fan et al., 2020), and the orientation of E−H+, E+H−, and E+H+ β2 integrins were indicated. This work enabled visualizing integrin molecules at the single molecular level and was the first to show the orientation of different conformation integrins. An unexpected face-to-face orientation of E−H+ β2 integrins is held by cis interaction with ICAM dimers (Fan et al., 2019). Airyscan confocal microscopy was used in imaging β2 integrin activation on neutrophils interacting with HUVECs (Fan et al., 2019). Our work (Fan et al., 2019) and a previous one (Moore et al., 2018) mentioned above were both focusing on the conformational changes of β2 integrins. Using iPALM, Moore et al. (2018) were able to show the E+ of β2 integrins by measuring the distance of β2 integrin headpiece to the substrate. In our work, we measured not only the E+ but also the H+ of β2 integrins. We can report all three active β2 integrin conformations (E−H+, E+H−, and E+H+). The pitfall of our work is that we assessed fixed samples, and iPALM can assess live cells. STED was used to show the colocalization of integrin αLβ2 and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) on neutrophils during cytokine midkine-induced neutrophil recruitment. (Weckbach et al., 2019). PALM was used to identify integrin β3 nanoclusters within FAs (Deschout et al., 2016; Deschout et al., 2017) and discover the role of integrin β3 nanoclusters in bridging thin matrix fibers and forming cell-matrix adhesions (Changede et al., 2019).

Intravital imaging of integrins

Whereas cellular behavior is different between in vitro and in vivo settings, biological processes are the sum of individual cellular behaviors shaped by many environmental factors. Endless efforts have been made to image cells residing in live animals at microscopic resolution, giving rise to intravital microscopy (IVM), an ever-developing field. In its infancy, blood flow within microvessels and circulating leukocytes targeting to inflamed tissue have been seen through bright field transillumination (Kunkel et al., 2000; Ley et al., 1993; Pittet and Weissleder, 2011; Ramadass et al., 2019). With the advent of fluorescence microscopy, genetically encoded fluorescent proteins (Cappenberg et al., 2019; Deppermann et al., 2020; Girbl et al., 2018; Honda et al., 2020; Hsu et al., 2019; Lammermann et al., 2013; Lefort et al., 2012; Marcovecchio et al., 2020; Matlung et al., 2018; McArdle et al., 2019; Owen-Woods et al., 2020; Powell et al., 2018; Schleicher et al., 2000; Uderhardt et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2020b; Wolf et al., 2018) and fluorescent dyes staining cells ex vivo before adoptive transfer or injected directly into the animal to enable visualization of endogenous structures are now available (Arokiasamy et al., 2019; Bousso and Robey, 2004; Deppermann et al., 2020; Girbl et al., 2018; Honda et al., 2020; Marcovecchio et al., 2020; Marki et al., 2018; Owen-Woods et al., 2020; Rapp et al., 2019; Schoen et al., 2019; Uderhardt et al., 2019; Vats et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2020b; Wolf et al., 2018). Detection of responses of individual cells within their natural environment over extended periods of time and space thus has become possible.

Epifluorescence microscopy can be used as IVM for studying integrins. One study showed that after 24 h of cecal ligation puncture, β1 integrins were found in the neutrophil extracellular traps in the liver and helped to sequester circulating tumor cells (Najmeh et al., 2017). In another study, RGD–Quantum Dot was used to report integrin activation on tumor vessel endothelium (Smith et al., 2008). Confocal microscopes can also be used for IVM. Spinning disk confocal IVM was used to visualize β3 integrins expressed on vascular endothelial cells, which tethers and interacts with Borrelia burgdorferi in circulation during infection (Kumar et al., 2015). Integrin α2 has been used as a marker for platelet aggregates in the spinning disk confocal intravital imaging of hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury (Van Golen et al., 2015). Multiphoton laser scanning microscopy is another popular method for IVM. Its conception is based on the principle that a fluorophore can not only be excited by one high-energy photon but also two simultaneous low-energy near-infrared photons with longer wavelengths of around 700 to 1,000 nm (Göppert-Mayer, 2009; Kawakami et al., 1999). Two-photon excitation needs a very high local photon density, which is reached at the focal plane. Thus, only fluorophores in the focal plane can be excited in two-photon microscopy. Fluorophores outside the focal plane are highly unlikely to be excited, making a high signal-to-background ratio. In confocal microscopy, fluorophores outside the focal plane will also be exited. In comparison, two-photon microscopy will have less photobleaching of fluorophores outside the focal plane, resulting in the lowest phototoxicity possible (Squirrell et al., 1999; Svoboda and Block, 1994). Great improvement of penetration depths (200–300 μm or even 1000 μm) and longer recording periods can be achieved by this technology (Benninger and Piston, 2013; Hickman et al., 2009; Kobat et al., 2011; Theer et al., 2003). Thus, multiphoton microscopy is a great choice of intravital imaging.

As mentioned before, integrin β2-mCFP mice were developed (Hyun et al., 2012), and these mice helped discover a β2 integrin-enriched uropod elongation during leukocyte extravasation using multiphoton IVM. Integrin αM-mYFP mice were developed (Lim et al., 2015) as well. In this study, the migration of αM+ leukocytes in the cremaster or trachea during fMLP stimulation or influenza infection was imaged by multiphoton IVM, respectively. In the follow-up study using αM-mYFP/β2-mCFP and αL-mYFP/β2-mCFP mice (Hyun et al., 2019), the activation of integrin αMβ2 and αLβ2 were reported by FRET in vivo for the first time using multiphoton IVM. It was found that αLβ2 is more important than αMβ2 in neutrophil transendothelial migration.

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) of integrins

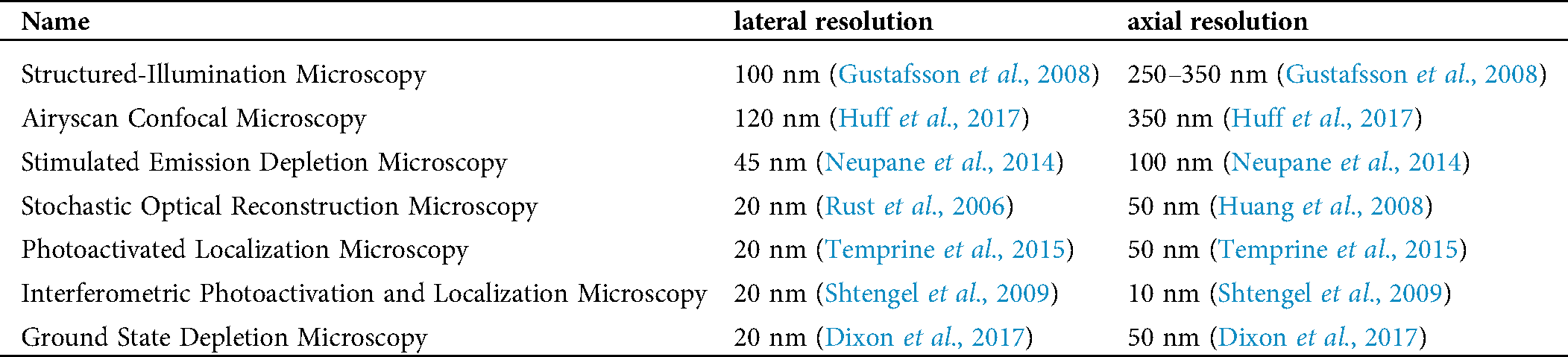

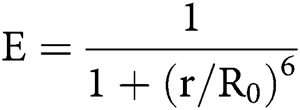

Since there are large conformational changes during integrin activation, techniques sensitive to distance changes like FRET become useful tools in studying integrins. FRET used as a ‘‘molecular ruler’’ ushered in the quantification of intermolecular interactions (Johnson, 2005; Stryer and Haugland, 1967). The concept of FRET was originally proposed by Teodor Förster in 1948. FRET is a phenomenon of quantum mechanics involving two matched fluorophores when the emission spectrum of the donor fluorophore overlaps with the excitation spectrum of the acceptor fluorophore. When the two fluorophores are in close physical juxtaposition (≤10 nm), the excitation of the donor results in emitted photons, which are quenched by and transfer the energy to the acceptor, resulting in the emission of acceptor fluorescence (Huebsch and Mooney, 2007; Periasamy, 2001). The efficiency of energy transfer is inversely related to the 6th power of the inter-molecular distance:

E is the efficiency, r is the intermolecular distance, and R0, known as Förster constant, is the value of r when this pair of donor and acceptor achieve 50% FRET efficiency. R0 depends on the overlap integral of the donor emission spectrum with the acceptor absorption spectrum and their mutual molecular orientation as expressed by the following equation:

in which  is Avogadro’s number;

is Avogadro’s number;  is the fluorescence quantum yield of the donor in the absence of acceptor;

is the fluorescence quantum yield of the donor in the absence of acceptor;  . is the dipole orientation factor;

. is the dipole orientation factor;  is the refractive index of the medium; and

is the refractive index of the medium; and  .is the spectral overlap integral of the donor-acceptor pair (Wang and Chien, 2007). Therefore, the range over which FRET can be observed is very narrow; only intra- and inter-molecular distances within ~2–10 nm can be detected (Huebsch and Mooney, 2007; Periasamy, 2001). The FRET efficiency can be altered by any change of the orientation or distance between the two fluorophores (Tsien, 1998).

.is the spectral overlap integral of the donor-acceptor pair (Wang and Chien, 2007). Therefore, the range over which FRET can be observed is very narrow; only intra- and inter-molecular distances within ~2–10 nm can be detected (Huebsch and Mooney, 2007; Periasamy, 2001). The FRET efficiency can be altered by any change of the orientation or distance between the two fluorophores (Tsien, 1998).

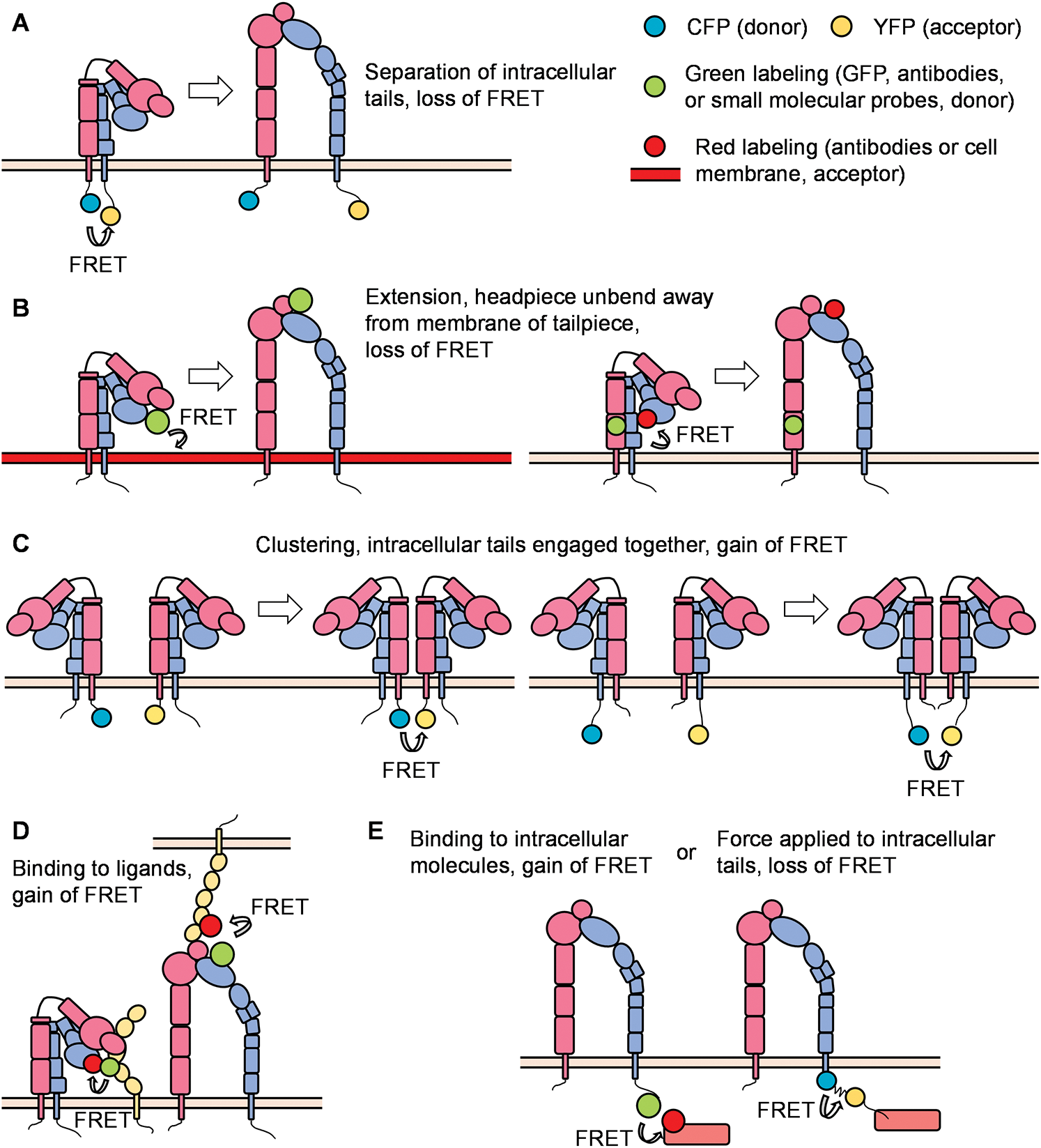

Figure 3: Principles of FRET (Förster resonance energy transfer) in integrin studies.

To obtain a FRET signal for studying the interaction of two proteins, they must be fluorescently labeled. One approach is to label the antibodies or antagonist/agonist binding to the two proteins with proper fluorophores. Fluorophore-conjugated antagonist/agonist can be synthesized, while labeling kits facilitating covalent binding (usually using amide bonds) of many different fluorescent molecules to antibodies are commercially available (Fan et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2016; Masi et al., 2010; Wen et al., 2020b). Another approach is introducing genes of two fluorescent proteins (FPs) to the donor/acceptor pair of proteins, respectively. Owing to their excellent extinction coefficients, quantum yield, and photostability, cyan fluorescence protein (CFP) and yellow fluorescence protein (YFP) are the most commonly used pair for FRET (Giepmans et al., 2006; Tsien, 1998). Green fluorescence protein (GFP) and red fluorescence protein (RFP) can also be utilized as a pair of fluorophores for FRET (Bajar et al., 2016; Lam et al., 2012). Genetic manipulation is conducted to gain recombinant fused genes, and the 1:1 ratio of donor/adaptor protein to CFP/YFP greatly simplifies the calculations of FRET efficiency and the quantification of protein interactions. One drawback of fusion proteins is the possibility to exhibit altered biological function or molecular structure. Thus, careful characterization before FRET is recommended (Masi et al., 2010; McArdle et al., 2016).

Measurements of (1) signal intensity and (2) fluorescence lifetimes are two major ways to determine FRET efficiency. Regarding the signal intensity method, the comparable changes between the intensification of the acceptor’s emission and synchronous decrease in donor’s emission facilitate the detection of FRET by splitting the emission from the two fluorophores. The split lights are then filtered through a specific filter set and collected separately. The downsides of this method are: (1) The excitation light of acceptor may excite the donor owing to the possible overlap of their excitation spectrum, (2) The leak of donor emission to the detecting channel of the acceptor, and (3) The faster photobleaching of the donor compared with that of the acceptor (Masi et al., 2010). The fluorescence lifetime is an intrinsic property of fluorophores. It is the characteristic time that a fluorophore stays in the excited state before the emission of the fluorescence photon. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) uses pulsed excitation lasers to acquire quantitative information through measurements of fluorescence lifetimes (Lakowicz et al., 1992; Le Marois and Suhling, 2017). Based on the fact that fluorescence lifetime decreases proportionally with the efficiency of FRET, FLIM-FRET serves as a precise way to determine FRET efficiency (Suhling et al., 2015). Although spectral overlap must always be taken into consideration in both methods, FLIM can rule out the influence of local fluorophore concentration or fluorescence intensity leading to the defects in signal intensity measurement (Lakowicz and Masters, 2008). There are additional strategies to measure FRET efficiency. “Donor de-quenching” (or “Acceptor photo-bleach”) method photo-bleaches the acceptor; thus, the increase of fluorescence in the “de-quenched” donor is proportional to FRET efficiency. FRET efficiency can be determined by measurement of donor fluorescence intensity before and after photobleaching of the acceptor. This method is an endpoint measurement making it incompatible with dynamic monitoring (Carman, 2012; Periasamy, 2001; Wang and Chien, 2007).

With the help of the improvement in microscopic techniques and labeling with fluorophores, great advantages have been made regarding integrin conformation and signaling. FRET can be used to identify the spatial movement of integrin cytoplasmic tails (Fig. 3A). In a classical study, leukocytes were stably transfected with FRET donor and acceptor pair mCFP and mYFP at the C-termini of the integrin αL and β2 subunits, respectively. In the resting state, high FRET efficiency was measured, indicating that the c-termini of the αL and β2 subunits were close to each other. Upon the triggering of the integrin inside-out signaling (chemokine SDF-1 and its receptor CXCR4) or outside-in signaling (ICAM-1 in the presence of Mn2+), the FRET efficiency was significantly reduced, indicating a spatial separation of αL and β2 cytoplasmic tails. Bidirectional integrin signaling is accomplished by coupling extracellular conformational changes to the separation of the cytoplasmic domains (Kim et al., 2003). A similar strategy has been applied to study αMβ2 integrin activation (αM-mCFP, β2-mYFP) as well (Fu et al., 2006; Lefort et al., 2009). The first dual-fluorescent protein KI mice – αLβ2 FRET (αL-YFP/ β2-CFP) mice and αMβ2 FRET (αL-YFP/ β2-CFP) mice – have been successfully constructed. By using two-photon intravital ratiometric analysis of (CFP/YFP) in neutrophils from these mice, determination of differential regulation of integrin αLβ2 and αMβ2 during neutrophil extravasation became realized (Hyun et al., 2019).

FRET can also be used to identify conformational changes in the integrin ectodomain domains. One method is to label the integrin headpiece and cell membrane/integrin tailpiece with FRET donor and acceptor, respectively, to measure the extension/unbending of integrins (Fig. 3B). In some studies, the LDV-FITC probe binding to the α4-integrin headgroup and octadecyl rhodamine B incorporated into the plasma membrane were used as the donor/acceptor pair for FRET assays. Several publications have proved the feasibility of detecting the extension of integrin α4β1 (Chigaev et al., 2003a; Chigaev et al., 2008; Sambrano et al., 2018). Integrin αIIbβ3 at the surface of blood platelets plays a primary role in hemostasis. FRET using fluorescently labeled Fab fragments of monoclonal antibodies targeting the βA/I-like domain of β3 subunit (donor, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated P97 Fab) and the calf-2 domain of αIIb subunit (acceptor, Cy3-M3 Fab or Cy3-M10 Fab) can determine the distance between these two domains at rest (about 6 nm) or activation (about 17 nm) states. Researchers found that activated αIIbβ3 in living platelets exhibits a conformation less extended than proposed by the switchblade model (Coutinho et al., 2007). In another study, a FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibody against integrin αM headpiece and octadecyl rhodamine B incorporated into the plasma membrane were used as the donor/acceptor pair for FRET assays to measure the extension of integrin αMβ2 (Lefort et al., 2009). Two distinct allosteric antagonists (BIRT 377 and XVA-143) targeting the αLI domain and β2 subunit I–like domain were used as donors. FRET conducted on live cells using a real-time flow cytometry approach was used to measure the distance between these two donors and a novel lipid acceptor PKH 26. Researchers found that triggering of the pathway used for T-cell activation (phorbol ester and thapsigargin) induced rapid extension of the integrin αLβ2 (Chigaev et al., 2015).

Instead of attaching donor and acceptor respectively to α and β subunits, studying integrin micro-clustering requires attachment of both the donor and acceptor to either the α or β subunit within one heterodimeric integrin (Fig. 3C). In this case, integrin micro-clustering will lead to FRET. In a study focused on Drosophila αPS2CβPS integrin, mVenus and mCherry were fused to cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of integrin β subunits. Mutations in α subunit cytoplastic domain (GFFNR to GFANA) or β subunit (V409D), which showed higher affinity for ligands, showed ~2-3-fold higher FRET values compared to that of wild type (Smith et al., 2007). In another study, K562 cells were transiently transfected with αL-mCFP, αL-mYFP, and wild-type β2, generating approximately equal amounts of αL-mCFP/2 and αL-mYFP/2 cells. The binding of ICAM-1 oligomers resulted in significant micro-clustering. In contrast, monomeric ICAM-1 did not induce integrin αLβ2 clustering (Kim et al., 2004). Using the same methodology, researchers found the disruption of the αLβ2 transmembrane domain by mutation of a key interface residue Thr-686 in the β2 transmembrane domain promoted binding of αLβ2 with ICAMs and facilitated αL microcluster formation (Vararattanavech et al., 2009).

FRET can also be used to assess interactions of the integrin headpiece with its ligands (Fig. 3D) and integrin cytoplasmic domains with the cytoskeleton and various signaling molecules (Fig. 3E) during integrin inside-out and outside-in signaling. In our previous study, we used FRET to detect the in-cis interaction of E−H+ β2 integrins and ICAM-1 (Fan et al., 2016). HA58-FITC, which binds ICAM-1 domain 1 and blocks its interaction with integrin αLβ2, but not integrin αMβ2, was used as the FRET donor. Antibody mAb24-DyLight 550 binding β2 integrin H+ headpiece was used as the acceptor. When integrin αMβ2 bound ICAM-1 in cis, the two antibodies were close enough to have FRET. When this interaction was blocked by mAb R6.5, which binds to integrin αMβ2-binding domain 3 of ICAM-1, or replacing the acceptor by KIM127- DyLight 550 (binding to the knees of E+ β2 integrins), FRET did not occur. These results indicate that E-H+ integrin αMβ2 binds ICAM-1 in cis (Fan et al., 2016). In another study, antibodies against FcγRIIA (Alexa Fluor 488) and integrin αMβ2 (Alexa Fluor 568) were used as donor and acceptor, respectively, to demonstrate the cis interaction of integrin αMβ2 and FcγRIIA by FLIM-FRET (Saggu et al., 2018). High-throughput dynamic three-color single molecule-FRET tracking was conceived. Orthogonal labeling of RGD and PHSRN motifs within fibronectin serve as FRET donor (Alexa Fluor 555) and acceptor (Alexa Fluor 594) at residues 1381 and 1500, respectively. FRET signatures are distinctive for the folded and unfolded state. The extracellular domain of αvβ3 was labeled with Alexa Fluor 647. By monitoring the intensity of all three dyes, the impact of fibronectin conformation and dynamics on αvβ3 integrin-binding can be determined. A more stable fibronectin-αvβ3 complex was observed when fibronectin exhibited a more folded conformation (Kastantin et al., 2017). Interaction of PKCα with β1 integrin was detected by FLIM-FRET performed in MCF7 cells, in which GFP-PKCα fusion protein was used as the donor, and integrin β1 antibody conjugated with Cy3.5 was used as the acceptor (Ng et al., 1999). Using FLIM-FRET, GFP-conjugated β1 integrin of mouse embryonic fibroblasts was found to interact with mRFP conjugates of the talin rod domain and α-actinin but not the talin head domain or paxillin (Parsons et al., 2008). Schwartz and colleagues have constructed a FRET-based tension sensor methodology, which consists of monomeric teal fluorescent protein (mTFP1) and monomeric Venus (mVenus) joined by a 40 amino-acid elastic linker (Faulon Marruecos et al., 2016). The elastic linker can elongate upon tensile force in the range of 0–6 pN. Incorporation of this reporter into the β2 subunit of integrin αLβ2 enabled researchers to find that actin polymerization and extracellular ligand-binding are in a positive feedback loop (Nordenfelt et al., 2016). FRET was used to assess the association of β1-integrin and ErbB2, which is an important integrator of transmembrane signaling by the EGFR family, on tumor cells. (Mocanu et al., 2005).

Overall, optical imaging of integrin molecules helps us understand the regulation of integrin expression, localization, clustering, conformational changes, and functions. Although there are various antibodies targeting integrin to visualize integrins with different conformations, most of these antibodies are specific for human integrin molecules. This limits the use of these antibodies for studying integrins in physiologically-relevant in vivo systems, such as mouse disease models, as well as in loss-of-function assays of integrin regulators because it is impossible to do genetic editing in humans. It has been reported that introducing human β2 integrins restores the infectious deficiency in β2 integrin knockout mice (Wilson et al., 1993). Thus, replacing the mouse integrin gene with human integrin cDNA might be a way to expand the use of existing integrin antibodies.

As we discussed, super-resolution microscopy is a powerful tool for studying integrins. However, their uses in integrin studies are mostly restricted to phenomenon reports and morphology studies. Thus, finding a way to dig into the molecular details of integrin regulation and function using super-resolution microscopy needs more attention. For example, super-resolution imaging can better assess the clustering of integrin molecules. Assessing the localization of important integrin modulators, such as talin, kindlin, RIAM, etc., by super-resolution microscopy will help understand their roles in regulating integrin activation.

FRET is a powerful tool to study dynamic changes in integrin conformation, but most FRET assays of integrins are restricted in cell lines. Only two integrin FRET mouse strains (αLβ2 and αMβ2) were developed. Thus, the development of more integrin FRET mouse strains is needed to visualize integrin conformation changes in vivo. Those mice could also be used in studying molecular mechanisms of integrin regulation and functions or in different disease models.

Although many techniques were developed to visualize integrin molecules as we reviewed above, whether the fluorescence labeling affects integrin function needs to be demonstrated in the specific studies, especially for activating specific integrin antibodies and fluorescent protein tags. For example, KIM127 was reported to stimulate leukocyte aggregation (Robinson et al., 1992), and mAb24 may lock the H+ conformation of β2 integrins (Smith et al., 2005). Thus, when using them in imaging, whether they affect the specific function interested in your study becomes critical. When we use them in studying integrin activation during neutrophil rolling and arrest, we tested that they do not affect ligand binding of β2 integrins and neutrophil arrest (Fan et al., 2016). This is the same case for fluorescent protein tags. In the iPALM study of β2 integrin (Moore et al., 2018), a mEos3.2 tag was inserted in the β-propeller domain of the αL-subunit of integrin αLβ2. They measure the axial movement of the mEos3.2 tag to report E+ of integrin αLβ2. They have tested that the fluorescence protein insertion in this site does not affect cell adhesion and ICAM-1 binding (Bonasio et al., 2007). In another study, a CFP-YFP tension sensor was inserted into the β2 integrin cytoplasmic tail to measure the force bearing of β2 integrins during cell migration using FRET (Nordenfelt et al., 2016). They have demonstrated that the insertion they used does not affect cell migration compared to cells transfected with wild-type β2 integrins.

Acknowledgement: We acknowledge Dr. Christopher “Kit” Bonin and Dr. Geneva Hargis from UConn Health School of Medicine for their help in the scientific writing and editing of this manuscript.

Author Contribution: Review conception and design: Z.F; Manuscript draft: C.C.; Manuscript revision and editing: Z.F., H.S., L.H.; Figure and table preparation: Z.F., C.C.; All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, USA (NIH, R01HL145454), and a startup fund from UConn Health.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbe HE. (1881). VII.-On the estimation of aperture in the microscope. Journal of the Royal Microscopical Society 1: 388–423. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1881.tb05909.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Adair BD, Alonso JL, Van Agthoven J, Hayes V, Ahn HS, Yu IS, Lin SW, Xiong JP, Poncz M, Arnaout MA. (2020). Structure-guided design of pure orthosteric inhibitors of αIIbβ3 that prevent thrombosis but preserve hemostasis. Nature Communications 11: 398. DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-13928-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Alivisatos AP, Gu W, Larabell C. (2005). Quantum dots as cellular probes. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 7: 55–76. DOI 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Andrew DP, Berlin C, Honda S, Yoshino T, Hamann A, Holzmann B, Kilshaw PJ, Butcher EC. (1994). Distinct but overlapping epitopes are involved in α 4 β 7-mediated adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, mucosal addressin-1, fibronectin, and lymphocyte aggregation. Journal of Immunology 153: 3847–3861. [Google Scholar]

Antonov AS, Antonova GN, Munn DH, Mivechi N, Lucas R, Catravas JD, Verin AD. (2011). αVβ3 integrin regulates macrophage inflammatory responses via PI3 kinase/Akt-dependent NF-κB activation. Journal of Cellular Physiology 226: 469–476. DOI 10.1002/jcp.22356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Argenzio E, Margadant C, Leyton-Puig D, Janssen H, Jalink K, Sonnenberg A, Moolenaar WH. (2014). CLIC4 regulates cell adhesion and β1 integrin trafficking. Journal of Cell Science 127: 5189–5203. DOI 10.1242/jcs.150623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arnaout MA. (2002). Integrin structure: New twists and turns in dynamic cell adhesion. Immunological Reviews 186: 125–140. DOI 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2002.18612.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arnaout MA. (2016). Biology and structure of leukocyte β 2 integrins and their role in inflammation. F1000Research 5: F1000 Faculty Rev-2433. [Google Scholar]

Arnaout MA, Goodman SL, Xiong JP. (2007). Structure and mechanics of integrin-based cell adhesion. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 19: 495–507. DOI 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arnaout MA, Mahalingam B, Xiong JP. (2005). Integrin structure, allostery, and bidirectional signaling. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 21: 381–410. DOI 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arokiasamy S, King R, Boulaghrasse H, Poston RN, Nourshargh S, Wang W, Voisin MB. (2019). Heparanase-dependent remodeling of initial lymphatic glycocalyx regulates tissue-fluid drainage during acute inflammation in vivo. Frontiers in Immunology 10: 2316. DOI 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Artoni A, Li J, Mitchell B, Ruan J, Takagi J, Springer TA, French DL, Coller BS. (2004). Integrin β3 regions controlling binding of murine mAb 7E3: Implications for the mechanism of integrin αIIbβ3 activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101: 13114–13120. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0404201101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Askari JA, Tynan CJ, Webb SE, Martin-Fernandez ML, Ballestrem C, Humphries MJ. (2010). Focal adhesions are sites of integrin extension. Journal of Cell Biology 188: 891–903. DOI 10.1083/jcb.200907174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Axelrod D. (1981). Cell-substrate contacts illuminated by total internal reflection fluorescence. Journal of Cell Biology 89: 141–145. DOI 10.1083/jcb.89.1.141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Axelrod D. (2001). Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy in cell biology. Traffic 2: 764–774. DOI 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.21104.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bagi Z, Couch Y, Broskova Z, Perez-Balderas F, Yeo T, Davis S, Fischer R, Sibson NR, Davis BG, Anthony DC. (2019). Extracellular vesicle integrins act as a nexus for platelet adhesion in cerebral microvessels. Scientific Reports 9: 15847. DOI 10.1038/s41598-019-52127-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bajar BT, Wang ES, Lam AJ, Kim BB, Jacobs CL, Howe ES, Davidson MW, Lin MZ, Chu J. (2016). Improving brightness and photostability of green and red fluorescent proteins for live cell imaging and FRET reporting. Scientific Reports 6: 20889. DOI 10.1038/srep20889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Balint S, Verdeny Vilanova I, Sandoval Alvarez A, Lakadamyali M. (2013). Correlative live-cell and superresolution microscopy reveals cargo transport dynamics at microtubule intersections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 3375–3380. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1219206110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Barczyk M, Carracedo S, Gullberg D. (2010). Integrins. Cell and Tissue Research 339: 269–280. DOI 10.1007/s00441-009-0834-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Battram AM, Durrant TN, Agbani EO, Heesom KJ, Paul DS, Piatt R, Poole AW, Cullen PJ, Bergmeier W, Moore SF, Hers I. (2017). The Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3) binder Rasa3 regulates Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-dependent Integrin αIIbβ3 Outside-in Signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry 292: 1691–1704. DOI 10.1074/jbc.M116.746867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beals CR, Edwards AC, Gottschalk RJ, Kuijpers TW, Staunton DE. (2001). CD18 activation epitopes induced by leukocyte activation. Journal of Immunology 167: 6113–6122. DOI 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Benninger RK, Piston DW. (2013). Two-photon excitation microscopy for the study of living cells and tissues. Current Protocols in Cell Biology 59: 4–11. DOI 10.1002/0471143030.cb0411s59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Berlin C, Berg EL, Briskin MJ, Andrew DP, Kilshaw PJ, Holzmann B, Weissman IL, Hamann A, Butcher EC. (1993). α4β7 integrin mediates lymphocyte binding to the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM-1. Cell 74: 185–195. DOI 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90305-A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bernadskaya YY, Brahmbhatt S, Gline SE, Wang W, Christiaen L. (2019). Discoidin-domain receptor coordinates cell-matrix adhesion and collective polarity in migratory cardiopharyngeal progenitors. Nature Communications 10: 57. DOI 10.1038/s41467-018-07976-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Betzig E, Patterson GH, Sougrat R, Lindwasser OW, Olenych S, Bonifacino JS, Davidson MW, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hess HF. (2006). Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science 313: 1642–1645. DOI 10.1126/science.1127344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bode W, Engh R, Musil D, Thiele U, Huber R, Karshikov A, Brzin J, Kos J, Turk V. (1988). The 2.0 A X-ray crystal structure of chicken egg white cystatin and its possible mode of interaction with cysteine proteinases. EMBO Journal 7: 2593–2599. DOI 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03109.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bonasio R, Carman CV, Kim E, Sage PT, Love KR, Mempel TR, Springer TA, Von Andrian UH. (2007). Specific and covalent labeling of a membrane protein with organic fluorochromes and quantum dots. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104: 14753–14758. DOI 10.1073/pnas.0705201104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bork P, Doerks T, Springer TA, Snel B. (1999). Domains in plexins: Links to integrins and transcription factors. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 24: 261–263. DOI 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01416-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bousso P, Robey EA. (2004). Dynamic behavior of T cells and thymocytes in lymphoid organs as revealed by two-photon microscopy. Immunity 21: 349–355. DOI 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bridges LC, Sheppard D, Bowditch RD. (2005). ADAM disintegrin-like domain recognition by the lymphocyte integrins α4β1 and α4β7. Biochemical Journal 387: 101–108. DOI 10.1042/BJ20041444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bui T, Rennhack J, Mok S, Ling C, Perez M, Roccamo J, Andrechek ER, Moraes C, Muller WJ. (2019). Functional redundancy between β1 and β3 integrin in activating the IR/Akt/mTORC1 signaling axis to promote ErbB2-driven breast cancer. Cell Reports 29: 589–602.e6. DOI 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.09.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Burrows L, Clark K, Mould AP, Humphries MJ. (1999). Fine mapping of inhibitory anti-α5 monoclonal antibody epitopes that differentially affect integrin-ligand binding. Biochemical Journal 344: 527–533. [Google Scholar]

Byron A, Humphries JD, Askari JA, Craig SE, Mould AP, Humphries MJ. (2009). Anti-integrin monoclonal antibodies. Journal of Cell Science 122: 4009–4011. DOI 10.1242/jcs.056770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Campbell ID, Humphries MJ. (2011). Integrin structure, activation, and interactions. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 3: a004994. DOI 10.1101/cshperspect.a004994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Capece T, Walling BL, Lim K, Kim KD, Bae S, Chung HL, Topham DJ, Kim M. (2017). A novel intracellular pool of LFA-1 is critical for asymmetric CD8+ T cell activation and differentiation. Journal of Cell Biology 216: 3817–3829. DOI 10.1083/jcb.201609072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cappenberg A, Margraf A, Thomas K, Bardel B, Mccreedy DA, Van Marck V, Mellmann A, Lowell CA, Zarbock A. (2019). L-selectin shedding affects bacterial clearance in the lung: A new regulatory pathway for integrin outside-in signaling. Blood 134: 1445–1457. DOI 10.1182/blood.2019000685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Carman CV. (2012). Overview: Imaging in the study of integrins. Methods in Molecular Biology 757: 159–189. [Google Scholar]

Carreno R, Brown WS, Li D, Hernandez JA, Wang Y, Kim TK, Craft JWJr., Komanduri KV, Radvanyi LG, Hwu P, Molldrem JJ, Legge GB, Mcintyre BW, Ma Q. (2010). 2E8 binds to the high affinity I-domain in a metal ion-dependent manner: A second generation monoclonal antibody selectively targeting activated LFA-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285: 32860–32868. DOI 10.1074/jbc.M110.111591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Martins Cavaco AC, Rezaei M, Caliandro MF, Lima AM, Stehling M, Dhayat SA, Haier J, Brakebusch C, Eble JA. (2018). The interaction between laminin-332 and α3β1 integrin determines differentiation and maintenance of CAFs, and supports invasion of pancreatic duct adenocarcinoma cells. Cancers 11: 14. DOI 10.3390/cancers11010014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Clark AY, Martin KE, Garcia JR, Johnson CT, Theriault HS, Han WM, Zhou DW, Botchwey EA, Garcia AJ. (2020). Integrin-specific hydrogels modulate transplanted human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell survival, engraftment, and reparative activities. Nature Communications 11: 114. DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-14000-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]