2021 45(1): 199-215

DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.012353

www.techscience.com/journal/biocell

| BIOCELL 2021 45(1): 199-215 DOI:10.32604/biocell.2021.012353 |  www.techscience.com/journal/biocell |

Rapid delivery of Cas9 gene into the tomato cv. ‘Heinz 1706’ through an optimized Agrobacterium-mediated transformation procedure

1Department of Horticulture, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, 41566, Korea

2Center for Genome Engineering, Institute for Basic Science, Daejeon, 34047, Korea

3School of Water, Energy, and Environment, Cranfield University, Cranfield, MK43 0AL, UK

4Institute of Agricultural Science and Technology, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, 41566, Korea

*Address correspondence to: Jeung-Sul Han, peterpan@knu.ac.kr

Received: 27 June 2020; Accepted: 24 August 2020

#These authors contributed equally to this work

Abstract: Solanum lycopersicum ‘Heinz 1706’ is a pioneer model cultivar for tomato research, whose whole genome sequence valuable for genomics studies is available. Nevertheless, a genetic transformation procedure for this cultivar has not yet been reported. Meanwhile, various genome editing technologies such as transfection of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) ribonucleoprotein complexes into cells are in the limelight. Utilizing the Cas9-expressing genotype possessing a reference genome can simplify the verification of an off-target effect, resolve the economic cost of Cas9 endonuclease preparation, and avoid the complex assembly process together with single-guide RNA (sgRNA) in the transfection approach. Thus, this study was designed to generate Cas9-expressing ‘Heinz 1706’ lines by establishing an Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT) procedure. Here, we report a rapid and reproducible transformation procedure for ‘Heinz 1706’ by fine-tuning various factors: A. tumefaciens strain, pre-culture and co-culture durations, a proper combination of phytohormones at each step, supplementation of acetosyringone, and shooting/rooting method. Particularly, through eluding subculture and simultaneously inducing shoot elongation and rooting from leaf cluster, we achieved a short duration of three months for recovering the transgenic plants expressing Cas9. The presence of the Cas9 gene and its stable expression were confirmed by PCR and qRT-PCR analyses, and the Cas9 gene integrated into the T0 plant genome was stably transmitted to T1 progeny. Therefore, we anticipate that our procedure appears to ease the conventional ATMT in ‘Heinz 1706’, and the created Cas9-expressing ‘Heinz 1706’ lines are ultimately useful in gene editing via unilateral transfection of sgRNA into the protoplasts.

Keywords: Transgenic plant; Phytohormone; Acetosyringone; Gene editing

The Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT) was firstly applied in tobacco plants (Herrera-Estrella et al., 1983). Since then, the ATMT technique has been used most efficiently in the field of plant genetic engineering (Ellul et al., 2003; Firsov et al., 2020; Van Eck et al., 2019). Recently, the ATMT technique is also successfully applied to deliver clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) expressing cassette to precisely edit a gene of interest in several crops, including tomato, accelerating functional genomics studies as well as genetic engineering in tomato (Chen et al., 2019; Veillet et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020). However, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing can often lead to unintended mutation (off-target editing) at non-specific homologous and/or mismatch tolerant sites, which may mask the true phenotype of the edited plants (Cardi et al., 2017; Lee and Kim, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). As a result, it demands to conduct the genome-wide sequencing of the gene-edited plant, and then the result has to be compared with the whole genome sequence of the wild type counterpart to ascertain an off-target effect. In this aspect, the unveiled whole genome sequence information of a given cultivar is critical to increasing the detection efficiency of off-target editing in addition to the effectiveness of candidate single guide RNA (sgRNA). The ‘Heinz 1706’ used in this study is a pioneer model cultivar, whose whole genome was firstly sequenced in tomato and frequently referenced in various studies (Aoki et al., 2013; Cambiaso et al., 2020; Rezzonico et al., 2017; The Tomato sequencing Consortium, 2012; Tranchida-Lombardo et al., 2018). Thus, the informative genomic background of ‘Heinz 1706’ helps to ease the detection of a possible off-target edit in the mutants.

The transfection of preassembled CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex into cells is an alternative to reduce the frequency of off-target editing, which is caused by the consecutive expression of the foreign genes in the edited plant genome. Woo et al. (2015) mentioned that the transfected RNP complex is rapidly degraded after cleaving the target site, which might reduce the frequency of mosaicism and off-target effects. However, the preparation of RNP is time-consuming and expensive (Anders and Jinek, 2014). Therefore, creating Cas9-expressing ‘Heinz 1706’ lines will have some advantages in the transfection of either sgRNA alone or the plasmid vector unilaterally expressing sgRNA. In short, applying the Cas9-expressing lines in transfection helps to resolve the cost to prepare a purified Cas9, shortens the steps of the RNP complex assembly process, and simplifies the structure of the plasmid vector by recombining sgRNA-expression cassette alone.

The success of ATMT is often influenced by several factors in different stages: (1) during the introduction of a T-DNA into a plant cell and its integration into the plant genome, and (2) in the course of selection and regeneration of transformants (Altpeter et al., 2016; Basso et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2015). Some crucial features affecting the aforementioned stages of ATMT include phytohormones concentration and combination, presence and absence of acetosyringone in co-culture media, durations of pre- and co-culturing, A. tumefaciens strain, plant tissue type, and plant genotype (Chetty et al., 2013; Fuentes et al., 2008, Guo et al., 2012; Nonaka et al., 2019; Stavridou et al., 2019). The other persistent challenge in ATMT of tomato is the frequent occurrence of ploidy alterations in regenerated transformants (Bednarek and Orlowska, 2020; Touchell et al., 2020; Ultzen et al., 1995), which might be caused by long culture period coupled with improper use of phytohormones for cell proliferation and differentiation (Niedz and Evens, 2016; Ochatt et al., 2011). Changes in ploidy level affect the genetic fidelity and phenotypes of the regenerated transformants, which means that a newly established/revised ATMT method needs to be assured of the ploidy normality of transformants.

Previous reports have shown that considerable efforts were made to optimize the ATMT procedures for the model tomato cultivars: ‘Moneymaker’ (Frary and Earle, 1996; Ho-Plágaro et al., 2018; Shah et al., 2015), ‘Micro-Tom’ (Chetty et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2012; Nonaka et al., 2019), ‘Rio Grande’ (Shah et al., 2015), and ‘M82’ (Gupta and Van Eck, 2016; Van Eck et al., 2019). However, we could not find any available report so far regarding the ATMT using the model cultivar ‘Heinz 1706’. Although various ATMT procedures for tomato cultivars have been documented, the procedure for a given cultivar may not necessarily work for other genotypes (Stavridou et al., 2019). Therefore, it is imperative to establish a working procedure for ‘Heinz 1706’ to achieve a successful transformation.

Here, we report a rapid and reproducible ATMT procedure for tomato ‘Heinz 1706’ by optimizing various factors, and the development of Cas9-expressing ‘Heinz 1706’ lines that will be used for future studies on gene editing through sgRNA transfection into their protoplasts.

Plant materials and in vitro culture conditions

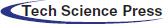

The tomato ‘Heinz 1706’ (accession No. LA4345) was provided from the CM Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center (TGRC) in the University of California, Davis, while the seeds of ‘Moneymaker’ and ‘Rubion’ were introduced from the Kansas State University. The seeds were surface sterilized by submerging in 70% (v/v) ethanol for 60 s, washing in sterile distilled water three times, immersing in the 12.5% (v/v) YUHANROX (commercial bleach containing 4% sodium hypochlorite; Yuhan-Clorox, Hwaseong, Gyeonggi, Korea) diluted with 0.2% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) with stirring at 200 rpm for 45 min, and lastly cleaning in sterile distilled water five times. The surface-sterilized seeds were sown on the seed germination medium (Tab. 1) and placed in a dark growth room for 3 days (d). The germinating seeds were exposed to a 16-h photoperiod for 6 d to develop the seedlings with fully expanded cotyledons. The cotyledonary explants were prepared by removing one-third of the distal parts from the detached cotyledons. The core components of the media and solutions used during Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (ATMT) processes are summarized in Tab. 1. The pH of the media and solutions was adjusted to 5.7 prior to autoclaving at 121°C for 30 min. Unless otherwise mentioned, the growth room was conditioned at 25 ± 2°C, 60 ± 5% relative humidity (RH), and a 16-h light rendered by fluorescent lights (100 μmol m−2 s−1).

Table 1: The components of the optimized media and solutions used during Agrobacterium-mediated transformation trials

1Murashige and Skoog (1962); 2Constituents of vitamins (100 mg/L myo-inositol, 0.5 mg/L nicotinic acid, 0.5 mg/L pyridoxine HCl, and 0.1 mg/L thiamine HCl)

Plasmid vector construction, bacterial strain, ATMT, and studied factors

The Cas9-containing vector pHAtC (GenBank accession number KU213971.1, Kim et al., 2016) was transformed into A. tumefaciens strains LB4404 and GV3101 using the freeze-thaw method (Holsters et al., 1978). The expression of Cas9, including the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) and human influenza hemagglutinin (HA)-tag, was regulated by the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. The pHAtC vector has the hygromycin resistance gene (Hyg-R), conferring resistance to the antibiotics hygromycin B, at the LB-flanking region of the T-DNA, and its expression is controlled by the nopaline synthase promoter (NOS) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of T-DNA of binary vector pHAtC used in the study. LB, left border; Ter, terminator sequence; Hyg-R, hygromycin resistance gene; NOS, nopaline synthase promoter; 35S, Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter; Cas9, Cas9 endonuclease gene; NLS, SV40 nuclear localization signal sequence; HA, influenza hemagglutinin epitope tag; RB, right border.

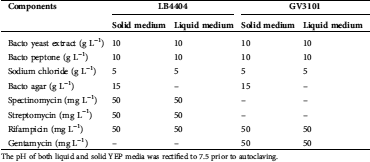

Solid and liquid yeast extract peptone (YEP) media were made to prepare bacterial inoculums (Supplementary Tab. 1). The two A. tumefaciens strains harboring the vector pHAtC were first cultured by streaking on the solid YEP medium and kept in the dark at 28°C for 19 h. Then the isolated colonies of each A. tumefaciens strain were picked up and inoculated in 50 mL of liquid YEP medium. The cultures were incubated in a shaker at 200 rpm and 28°C for 9 h up to OD600 = 0.8 to 1.0. The bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifuging with 4000×g at 4°C for 7 min, followed by washing in the inoculum solution (Tab. 1). The re-pelleted bacteria were diluted in 50 mL of inoculum solution and incubated in a shaker (200 rpm, 28°C) in darkness for 1 h. These bacterial suspensions were used to infect the explants for assaying the various factors affecting ATMT.

The cotyledonary explants were infected independently with the A. tumefaciens strains (LB4404 and GV3101) according to the previous report (Park et al., 2003) to choose the physiologically compatible strain with ‘Heinz 1706’. To ascertain the influence of pre-culture and co-culture durations on transformation, the explants were pre-cultured for 1 or 2 d on the pre-culture medium (Tab. 1) before infected by the bacteria. All the pre-cultured explants were placed into the bacterial inoculums and stirred at 200 rpm for 20 min. Then the infected explants were blotted dry on sterilized filter paper and co-cultured in the dark for 2, 3, or 4 d. The co-culture media were supplemented with various amounts of acetosyringone [3’,5’-dimethoxy-4’-hydroxy acetophenone (Sigma-Aldrich, Co.); 50, 100, or 200 µM] to investigate its contribution to the efficiency of transformation.

The co-cultured explants were washed twice with the washing solution (Tab. 1), blotted dry, transplanted to the leaf cluster induction medium (Tab. 1), and kept in the growth room. The regenerated leaf clusters were cut and transferred to the shoot elongation/rooting (SER) media with different concentrations of IBA (Sigma-Aldrich, Co.) (0 to 4 mg/L) and trans-zeatin (Sigma-Aldrich, Co.) (0–0.2 mg/L).

Acclimatization of regenerated plantlets, generation of T1 plants, and heritability estimation

Elongated plantlets with roots (putative T0 plantlets) were thoroughly washed with tap water, transferred to the plastic pots filled with clean commercial compost, put into a translucent plastic container, and then placed in a growth chamber conditioned at 25°C, 60% RH, and a 16-h light for a week. The acclimatized plantlets were transplanted into a 4-L plastic pot containing commercial compost, then placed in a greenhouse at day/night temperatures of 23/18 ± 5°C and 60 ± 5% RH. For estimating the heritability of the Cas9 gene, randomly selected three PCR-positive T0 plants with normal ploidy were allowed to self-pollinate. Matured T1 seeds were collected from the fruits of each T0 plant, which were used to develop T1 seedlings for determining the transmission of the Cas9 gene from T0 plants.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis

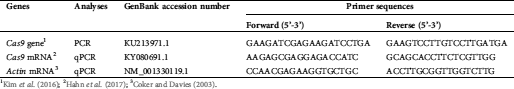

Genomic DNA was isolated from the newly emerging leaves using Solg™ Genomic DNA Prep Kit (SolGenet Co, Ltd., Daejeon, South Chungcheong, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The fragment (502 bp) of the Cas9 gene in genomic DNA was amplified with the primer set (Kim et al., 2016; Supplementary Tab. 2). The PCR was performed in a 50-μL reaction mixture containing 0.1 μg genomic DNA, 10 μM each of forward and reverse primers, and 25 μL of 2X PCRBIO Taq Mix Red (PCR Biosystems Inc., Wayne, Pennsylvania, USA). Amplification consisted of 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 63°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 15 s in the Super Cycler™ SC-200 (Kyratec life sciences, Mansfield, Queensland, Australia). The PCR product was electrophoresed in 1% agarose (LonsaSeakem®LE agarose; Rockland, Maine, USA) gel and stained with ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, Co.). The amplicons were visualized and photographed on an ultraviolet trans-illuminator equipped with a molecular imaging system (Kodak Image Station 4000 MM Pro; Carestream Health, Inc., New Haven, Connecticut, USA).

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was first extracted from the newly emerging leaves of PCR-positive plant using RNeasy® Mini Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) to examine the transcription of the Cas9 gene in the transformants. The RNA sample was then treated with DNase I (RNase-Free DNase Set; QIAGEN GmbH) once more to remove any contaminated genomic DNA. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 100 ng of purified RNA using SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). The real-time qPCR was performed in a 20-μL reaction mixture containing 1 μL of the synthesized cDNA, 0.8 μM each of forward and reverse primers for Cas9 and Actin mRNAs (Coker and Davies, 2003; Hahn et al., 2017; Supplementary Tab. 2), and 10 μL of 2X qPCRBIO SyGreen Blue Mix (PCR Biosystems Inc.) using Roter-Gene Q real-time PCR cycler (QIAGEN GmbH). The assay was run in triplicates by using the reaction mixture without cDNA as a negative control and Actin as an internal control. Reaction consisted of 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 65°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 10 s. The expression fold change was estimated by using the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCt) method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008).

The ploidy of putative transgenic plantlets was determined using a ploidy analyzer (PAII; Partech, Münster, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) in comparison with the wild type seedling. Each young leaf was chopped with a razor blade in 0.5 mL of nuclei extraction buffer (Sysmex Partech GmbH, Am Flugplatz, Görlitz, Germany). The suspension was filtered through a 30-μm nylon mesh (Sysmex Partech GmbH), which was supported by a 1.6-mL tube, and kept at room temperature for 1 min. Then, 2 mL of the staining buffer (Sysmex Partech GmbH) was added to the filtrate and incubated for about 30 s. Lastly, the ploidy of the sample was measured after inserting the tube at the probe of the ploidy analyzer.

Overall, seven separate experiments were conducted to establish the ATMT procedure for ‘Heinz 1706’. Unless otherwise noted, the experiments were replicated at least three times, and more than 100 explants were assayed each time. The percentage of transformation was calculated by counting the number of PCR-positive plantlets and divided by the total number of co-cultured explants. The collected data were subjected to ANOVA using SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cray, North Carolina, USA). Similarly, comparisons of significant means were conducted by Student’s t-test (t-test), Chi-square (χ2) test, Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT), or the least significant difference (LSD) test at p < 0.05. Mean ± standard error (SE) was used to present the data.

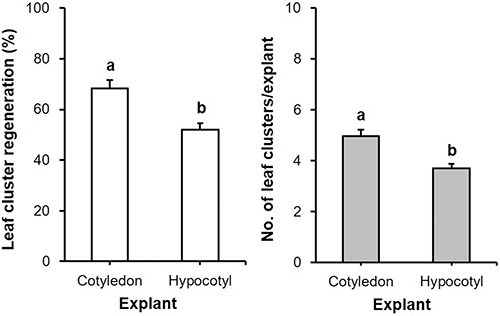

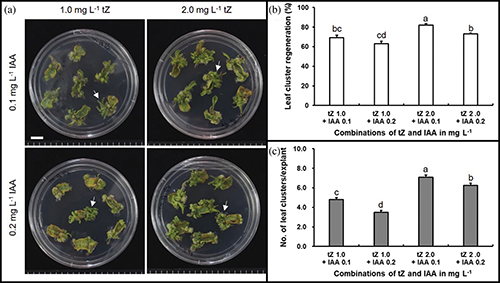

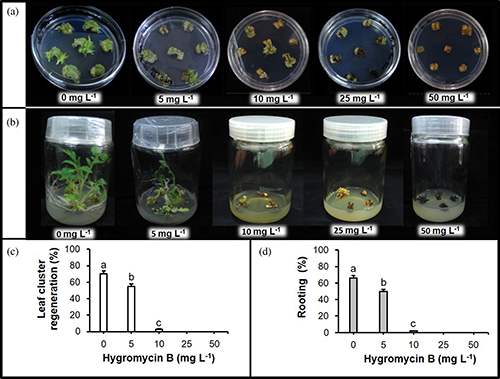

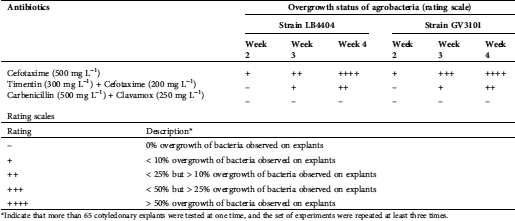

Selection of suitable explant type, hormone combination, and concentration of selectable agent

Prior to Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT) of ‘Heinz 1706’, the suitable explant type and phytohormone combination for leaf cluster induction in addition to the lethal dose of hygromycin B for later transformant-selection were screened. These preliminary studies showed that the cotyledonary explants were superior for leaf cluster induction to hypocotyl explants (Supplementary Fig. 1), which pushed through with cotyledon as the explant source for the following experiments. The results also indicated that the phytohormone combination of 2 mg/L trans-zeatin and 0.1 mg/L indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) was effective for leaf cluster induction from cotyledonary explants (Supplementary Fig. 2), and an addition of 10 mg/L hygromycin B was appropriate to select putative transgenic plantlets (Supplementary Fig. 3). Furthermore, the bacteria, which completed their role, was eliminated through the combined application of 500 mg/L carbenicillin (Sigma-Aldrich, Co.) and 250 mg/L Clavamox® (GlaxoSmithKline, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA) (Supplementary Tab. 3). Consequently, cotyledonary explants, together with the mentioned combination of phytohormones and concentration of antibiotics, were used for further ATMT studies.

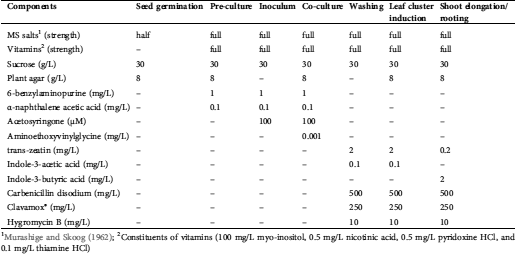

ATMT efficiency in ‘Heinz 1706’ was dependent on A. tumefaciens strain

To identify the more virulent strain of A. tumefaciens to ‘Heinz 1706’, a total of 1677 (1362 for strain LB4404 and 315 for strain GV3101) 1-d pre-cultured cotyledonary explants were co-cultured with the strains. Based on PCR results, four transformants were obtained only from the explants infected by GV3101. However, no transformants were recovered from LB4404 treatment (Fig. 2a and 2b). Furthermore, the results of the qRT-PCR analyses confirmed that the Cas9 transgenes were stably expressed in the T0 transgenic plants (Fig. 2c). Thus, strain GV3101 was chosen for examining other factors affecting ATMT.

Figure 2: Suitability assessment of A. tumefaciens strain for the transformation of tomato ‘Heinz 1706’ and expression analysis of the Cas9 gene. (a) Effect of strains on plantlet regeneration and transformation efficiency, Bars indicate SE, Values with different letters are statistically different (p < 0.05, by t-test); (b) Detection of Cas9 gene in the transgenic plantlets generated using the bacterial strain GV3101 by PCR analysis, * Indicate positive plantlets; (c) The transcription level of Cas9 gene in transgenic T0 plants using the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCt) method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008), Data represent the mean of five biological and three technical replicates, Bars indicate SE, *** indicate a significant difference between the wild type and T0 plants (p < 0.001, by LSD test).

ATMT efficiency in ‘Heinz 1706’ was influenced by pre-culture and co-culture durations

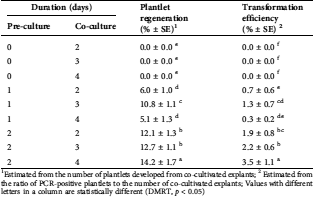

The findings of this study demonstrated that pre-culture and co-culture durations were other important factors affecting transformation efficiency (Tab. 2). All the non-pre-cultured explants were finally necrotized without regenerative response regardless of co-culture duration, while the pre-cultured explants for 1 or 2 d successfully generated the plantlets with different regeneration and transformation frequencies (Tab. 2). Among the combinations of pre-culture and co-culture durations, significantly higher (p < 0.001) number of transformants (three to four) were obtained from the explants treated for 2 d pre-culture followed by 4 d co-culture (Tab. 2).

Table 2: Impacts of pre-culture and co-culture durations on transformation efficiency

1Estimated from the number of plantlets developed from co-cultivated explants; 2 Estimated from the ratio of PCR-positive plantlets to the number of co-cultivated explants; Values with different letters in a column are statistically different (DMRT, p < 0.05)

Addition of acetosyringone enhanced the efficiency of ATMT in ‘Heinz 1706’

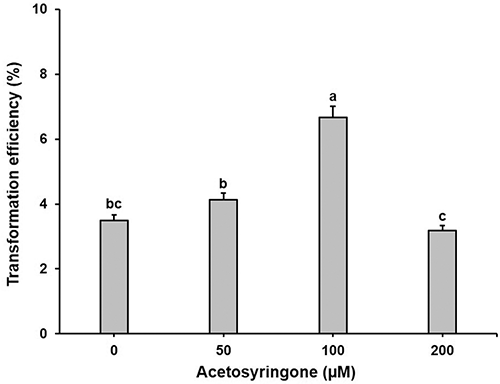

Various amounts of acetosyringone were supplemented to the co-culture medium to examine their contribution to transformation efficiency. The result showed that the addition of acetosyringone in the co-culture medium significantly influenced (p < 0.001) the production of transgenic plantlets (Fig. 3). About a two-fold rise in transformation efficiency (6.7%: Seven transformants) was obtained with the addition of 100 μM acetosyringone when compared to the acetosyringone-free medium. However, it appeared that the addition of 200 μM acetosyringone has an adverse effect on the transformation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Effect of acetosyringone on transformation efficiency in tomato ‘Heinz 1706’. Bars denote SE, Values with different letters are statistically different (p < 0.05, by LSD test).

Rapid recovery of transgenic plantlets is possible through avoiding repeated subculture

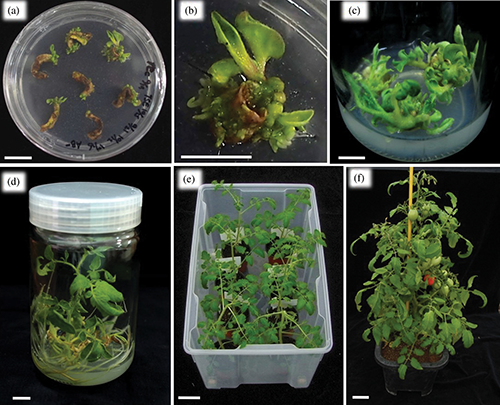

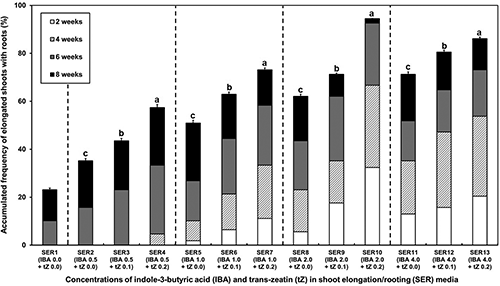

On the leaf cluster induction medium, the leaf clusters were directly differentiated mainly from the basal cut-edges of the cotyledonary explants within three to four weeks (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, instead of shoot elongation, the leaf clusters became necrotic and replaced with new leaf clusters from the explants whenever subcultured on the fresh leaf cluster induction medium. Consequently, the firstly emerged leaf clusters were excised (Fig. 4b) and cultured on the shoot elongation/rooting (SER) media with different combinations of indole-3-butyric acid (IBA, Sigma-Aldrich, Co.) and trans-zeatin (Sigma-Aldrich, Co.) concentrations (Fig. 5). This combined addition of phytohormones to the SER media dramatically facilitated the elongation of shoots (Fig. 4c) and the subsequent development of plantlets with roots (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4: In vitro organogenesis and ex vitro growth stages of transgenic tomato ‘Heinz 1706’. (a) Regenerated hygromycin-resistant leaf clusters after four weeks culturing on the leaf cluster induction medium; (b) A magnified view of a 4-week-old leaf cluster; (c) Well elongated shoots on the shoot elongation/rooting (SER) medium; (d) A vigorously rooted plantlet on the SER medium; Scale bars in (a–d) = 1 cm; (e) Soil-acclimatized putative transgenic plantlets; (f) An adult transgenic plant at fruiting stage in a greenhouse; Scale bars in (e–f) = 5 cm.

Figure 5: Time-series comparison of various combinations of IBA (mg/L) and trans-zeatin (mg/L) added to the shoot elongation/rooting (SER) medium on transgenic plantlet development from leaf cluster explants of tomato ‘Heinz 1706’. Values with different letters in the domain with the same concentration of IBA are statistically different (by DMRT, p < 0.05).

A significant variation ranging from 23.2% to 91.7% (p < 0.01) in shoot elongation/rooting frequency was observed among the different SER media (Fig. 5). Compared with the frequencies in other SER media that reached a maximum at eight weeks of culture, the maximum frequency in SER10 medium was accomplished at six weeks of culture (Fig. 5). This result indicates that the SER10 medium containing 0.2 mg/L trans-zeatin and 2 mg/L IBA can reduce the duration for plantlet regeneration by two weeks. In addition, the SER10 medium was effective to recover a higher number of plantlets (Fig. 5). Meanwhile, some elongated shoots without roots and non-responsive leaf clusters were sub-cultured one more time on the respective fresh SER media, which also let them develop plantlets with different durations and frequencies. The acclimatized plantlets (Fig. 4e) exhibited a normal growth, flowering, and fruiting in a greenhouse (Fig. 4f).

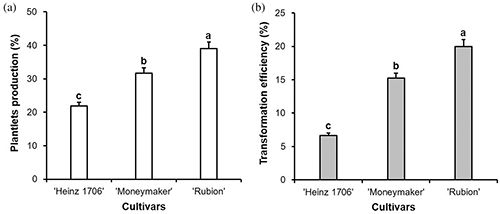

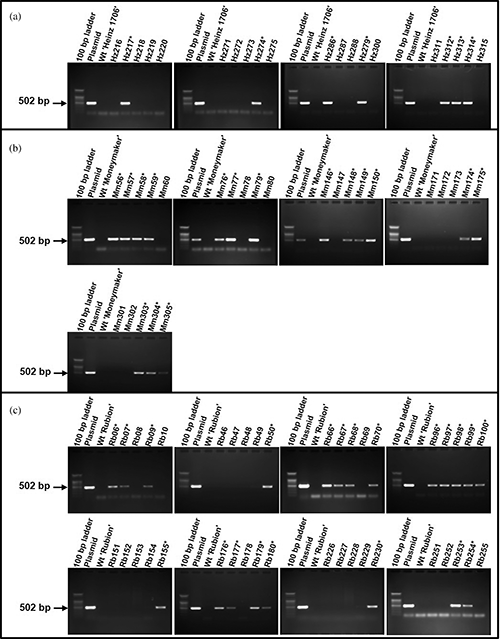

The optimized ATMT procedure for ‘Heinz 1706’ can be adaptable to other cultivars

We applied the optimized ATMT procedure against cultivars ‘Moneymaker’ and ‘Rubion’ to evaluate its adaptability (Fig. 6). The PCR analyses of the regenerants showed high frequencies of transformation in the cultivars [15.2% (sixteen transformants) in ‘Moneymaker’ and 20.0% (twenty-one transformants) in ‘Rubion’] (Supplementary Fig. 4; Fig. 7), indicating the applicability of the current procedure to other tomato cultivars.

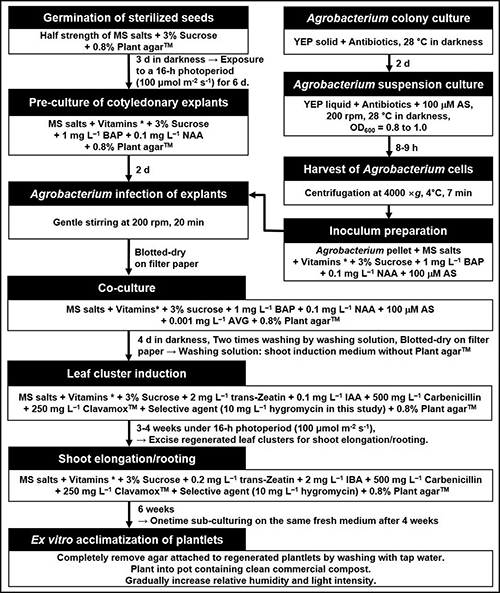

Figure 6: A flowchart of the optimized Agrobacteium tumefaciens-mediated transformation procedure for tomato ‘Heinz 1706’. IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; IBA, indole-3-butyric acid; BAP, 6-benzyl-aminopurine; NAA, α-naphthalene acetic acid; AVG, aminoethoxyvinylglycine; AS, acetosyringone; * vitamins: 100 mg/L myo-inositol, 0.5 mg/L nicotinic acid, 0.5 mg/L pyridoxine HCl, and 0.1 mg/L thiamine HCl.

Figure 7: Plantlets production (a) and transformation efficiencies (b) of three tomato cultivars when applying the ATMT procedure optimized for ‘Heinz 1706’ in this study. Bars denote SE. Values with different letters are statistically different (p < 0.05, by LSD test).

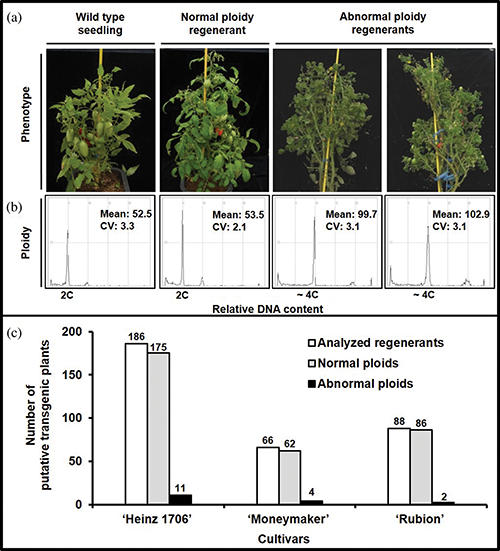

Flow cytometric analysis revealed a low frequency of ploidy changes in regenerants

To check the frequency of ploidy changes in the regenerants derived through the present optimized procedure, all the regenerated plantlets were analyzed and compared with their respective ex-vitro developed seedlings. The peaks of relative DNA contents measured by flow cytometry indicated that only 5% of the regenerants showed an altered ploidy level (Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, the minor somaclonal variation observed in the regenerants further strengthened the effectiveness and reproducibility of our ATMT procedure.

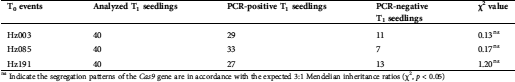

The Cas9 genes were stably transmitted to the next generation

Successful transmission of a foreign gene to the next generation is vital for maintaining the transgenic lines. In this regard, forty T1 seedlings were developed from each T0 plant and analyzed by PCR amplification. The PCR results revealed that the Cas9 genes of T0 plants were typically transmitted to T1 generation with 3:1 ratio (Tab. 3).

Table 3: Segregation pattern of the Cas9 gene in T1 progenies of ‘Heinz 1706’ as detected by PCR

ns Indicate the segregation patterns of the Cas9 gene are in accordance with the expected 3:1 Mendelian inheritance ratios (χ2, p < 0.05)

Previous studies have described that the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT) system is one of the widely employed genetic modification tools to support plant molecular studies and crop improvements (Arshad et al., 2014; Hayut et al., 2017; Lacroix and Citovsky, 2019; Nonaka et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2015). Nevertheless, an effective ATMT procedure optimized for one specific cultivar may not necessarily ensure a similar efficacy in other cultivars (Prihatna et al., 2019; Stavridou et al., 2019). Even in our initial attempt of the transformation study, the broad-spectrum tomato ATMT procedure of Park et al. (2003) gave rise to the extremely low frequency of transformation (0 to 1.3%) in cultivar ‘Heinz 1706’ (Fig. 2a), which is at least 18.7% lower than their average 20% transformant recovery rate. This result indicates that the optimization of factors affecting ATMT is imperative for achieving higher transformation efficiency in the recalcitrant ‘Heinz 1706’.

The influences of various A. tumefaciens strains on the transformation of tomato ‘Micro-Tom’ have been described by Chetty et al. (2013) and Nonaka et al. (2019), who demonstrated the differential transformation efficiencies ranging from 15% to 72%, illustrating that the transformation efficiency is A. tumefaciens strain-dependent. On the contrary, Sharma et al. (2009) showed tomato cultivar-dependent transformation efficiencies (22% for ‘Arka Vika’ to 41% for ‘Sioux’) using the same A. tumefaciens strain AGL1. These examples implicate the significance of physiological compatibility between host and bacterial genotypes for successful ATMT in tomato. Indeed, the extremeness of ATMT efficiency depending on A. tumefaciens strain that ranged between 0% for LBA4404 (Fig. 2a) and 6.7% for GV3101 (Figs. 3 and 7) was observed in our study using ‘Heinz 1706’. Thus, it is possible to suggest that ‘Heinz 1706’ might be more compatible with GV3101 than LBA4404.

Various studies have indicated the necessity of using a feeder layer during pre- and co-cultures in tomato ATMT (Fillatti et al., 1987; Gupta and Van Eck, 2016; Rai et al., 2012). However, it is not easy to approach the method due to its complexity. Thus, we employed the pre- and co-culture media of Park et al. (2003) with the modifications in the culture duration and acetosyringone concentration. Several researchers have described that the pre- and co-culture durations are crucial factors to increase the efficiency of transformation in tomato (Park et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2009; Stavridou et al., 2019), and they showed that 1-d pre-culture/3-d co-culture, 2-d pre-culture/3-d co-culture, and 1-d pre-culture/2-d co-culture was optimum, respectively. However, their observations were different from the findings of our study, in which a 2-d pre-culture/4-d co-culture was the best combination to obtain the highest efficiency of ATMT in ‘Heinz 1706’ (Tab. 2). Thus, our study illustrated that the longer pre-culture/co-culture duration (2/4 d) might be favorable to the bacteria to perform a series of T-DNA transfer process into the recalcitrant ‘Heinz 1706’ cells.

It is eminent that the supplementation of exogenous acetosyringone is effective in stimulating A. tumefaciens attachment on the explant cells and encouraging the bacterial vir genes expression (Nonaka et al., 2008; Stachel et al., 1986; Wu et al., 2006). Our study proved that the addition of 100 μM acetosyringone in the co-culture medium was optimum to improve the transformation efficiency in ‘Heinz 1706’ (Fig. 3). Even though the concentrations of acetosyringone up to 500 µM have been applied to increase the success of transformation in tomato (Fuentes et al., 2008; Khuong et al., 2013; Nonaka et al., 2019; Raj et al., 2005; Stavridou et al., 2019), the addition of 200 μM acetosyringone adversely affected the transformation efficiency in our study (Fig. 3). The response variation in the efficiency of transformation by the supplementation of acetosyringone is evident owing to the difference in co-culture duration, the competence of the tissue, plant species, and explant type (Shrawat et al., 2007), which might have a differential effect on the secretion of endogenous phenolic compounds.

Reduction in transformation duration and steps have been described as another important factor in assessing the utility of the ATMT procedure (Cruz-Mendívil et al., 2011; Gupta and Van Eck, 2016; Park et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2020). The whole ATMT in our procedure only required about three months, starting from seed sowing to attaining acclimated transgenic plantlets (Fig. 6). In contrast, longer durations between four months (Cruz-Mendívil et al., 2011; Van Eck et al., 2019) and ten months (Ellul et al., 2003) were reported. The short transformation cycling period shown in our study is achieved through amalgamating the independent shoot elongation and rooting activities in a single step, avoiding the frequent subculture in each step, and optimizing phytohormonal condition (0.2 mg/L trans-zeatin and 2 mg/L IBA) in the shoot elongation/rooting (SER) medium.

Interestingly, our rapid procedure resulted in fewer regenerants with abnormal ploidy (5%, Supplementary Fig. 5c) compared to the previously reported high frequencies (from 24.5 to 80 %) (Den Bulk et al., 1990; Ellul et al., 2003; Fillatti et al., 1987; Ling et al., 1998). The low frequency of ploidy changes shown in this study might be associated with the less frequent subculture and the shorter culture duration. In agreement with the findings of our study, Bidabadi and Jain (2020) and Sun et al. (2013) suggested that rapid regeneration of a plantlet by shortening the in vitro culture period is important to reduce the rate of somaclonal variations in regenerants. Likewise, the elevated occurrence of ploidy changes during long in vitro culture was also reported (Niedz and Evens, 2016; Ochatt et al., 2011). Therefore, we strongly recommend the ploidy measurement of transformants before drawing conclusive remarks on the role of a transgene in tomato ATMT.

The qRT-PCR analysis revealed that our ATMT procedure was successful to create Cas9-expressing ‘Heinz 1706’ lines (Fig. 2c). The lines would hold a merit in the case of protoplast-transfection of the in vitro transcribed single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) or plasmid vectors expressing sgRNAs for targeted gene editing (Ali et al., 2015; Svitashev et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2015). In CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing, unexpected mutations at a non-specific site (off-target effects) frequently occur (Cardi et al., 2017; Lee and Kim, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018), which requires the genome-wide sequencing on the edited plants. Thus, the ‘Heinz 1706’ with an unveiled whole-genome sequence is very useful to simplify the detection of off-target edits. On this account, the Cas9-expressing ‘Heinz 1706’ lines, which were created in this study, can be an important plant material for detecting the off-target edits.

In this study, a rapid and reproducible Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (ATMT) procedure was established for the recalcitrant tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Heinz 1706) for the first time by optimizing the factors relevant to ATMT. All the studied factors were found to be basic for enhancing transformation efficiency, while the amalgamation of the shoot elongation and rooting steps distinctly leads to a rapid recovery of transgenic plants. The rapid ATMT procedure also has a merit for obtaining experimental results earlier and reducing the frequency of ploidy changes in the transgenic plants. Therefore, we expect that our procedure enriches the ATMT technique for the effective transfer of various desirable genes and contributes to advance the emerging CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing studies in tomato. Besides, the Cas9-expressing ‘Heinz 1706’ lines obtained in this study might be valuable for genome editing studies such as sgRNA transfection and off-target detection.

Acknowledgement: Authors are thankful to Md. Mazharul Islam for helping us in ploidy analysis.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. Data on preliminary tests are also provided in separate files as supplementary materials (Supplementary Tables and Figures). Thus, the readers can freely access all the published data with proper acknowledgment and citation. Besides, all the raw data sets generated or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding Statement: The author(s) received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Ali Z, Abulfaraj A, Idris A, Ali S, Tashkandi M, Mahfouz MM. (2015). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated viral interference in plants. Genome Biology 16: 267. DOI 10.1186/s13059-015-0799-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Altpeter F, Springer NM, Bartley LE, Blechl AE, Brutnell TP, Citovsky V, Conrad LJ, Gelvin SB, Jackson DP, Kausch AP, Lemaux PG, Medford JI, Orozco-Cárdenas ML, Tricoli DM, van Eck J, Voytas DF, Walbot V, Wang K, Zhang ZJ, Stewart CN. (2016). Advancing crop transformation in the era of genome editing. Plant Cell 28: 1510–1520. DOI 10.1105/tpc.16.00196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Anders C, Jinek M. (2014). In vitro enzymology of Cas9. Methods in Enzymology 546: 1–20. DOI 10.1016/B978-0-12-801185-0.00001-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Aoki K, Ogata Y, Igarashi K, Yano K, Nagasaki H, Kaminuma E, Toyoda A. (2013). Functional genomics of tomato in a post-genome-sequencing phase. Breeding Science 63: 14–20. DOI 10.1270/jsbbs.63.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arshad W, Haq I, Waheed MT, Mysore KS, Mirza B. (2014). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tomato with rolB gene results in enhancement of fruit quality and foliar resistance against fungal pathogens. PLoS One 9: e96979. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0096979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Basso MF, Arraes FBM, Grossi-de-Sa M, Moreira VJV, Alves-Ferreira M, Grossi-de-Sa MF. (2020). Insights into genetic and molecular elements for transgenic crop development. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 280. DOI 10.3389/fpls.2020.00509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bednarek PT, Orlowska R. (2020). Plant tissue culture environment as a switch-key of (epi)genetic changes. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 140: 245–257. DOI 10.1007/s11240-019-01724-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bidabadi SS, Jain SM. (2020). Cellular, molecular, and physiological aspects of in vitro plant regeneration. Plants 9: 702. DOI 10.3390/plants9060702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cambiaso V, Rodríguez GR, Francis DM. (2020). Propagation fidelity and kinship of tomato varieties ‘UC 82’ and ‘M82’ revealed by analysis of sequence variation. Agronomy 10: 538. DOI 10.3390/agronomy10040538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cardi T, D’Agostino N, Tripodi P. (2017). Genetic transformation and genomic resources for next-generation precise genome engineering in vegetable crops. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 136. DOI 10.3389/fpls.2017.00241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen K, Wang Y, Zhang R, Zhang H, Gao C. (2019). CRISPR/Cas genome editing and precision plant breeding in agriculture. Annual Review of Plant Biology 70: 667–697. DOI 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chetty VJ, Ceballos N, Garcia D, Narvaez-Vasquez J, Lopez W, Orozco-Cardenas ML. (2013). Evaluation of four Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains for the genetic transformation of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivar micro-tom. Plant Cell Reports 32: 239–247. DOI 10.1007/s00299-012-1358-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Coker JS, Davies E. (2003). Selection of candidate housekeeping controls in tomato plants using EST data. BioTechniques 35: 740–748. DOI 10.2144/03354st04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cruz-Mendívil A, Rivera-López J, Germán-Báez L J, López-Meyer M, Hernández-Verdugo S, López-Valenzuela JA, Reyes-Moreno C, Valdez-Ortiz A. (2011). A simple and efficient protocol for plant regeneration and genetic transformation of tomato cv. micro-tom from leaf explants. HortScience 46: 1655–1660. DOI 10.21273/HORTSCI.46.12.1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

van den Bulk RW, Löffler HJM, Lindhout WH, Koornneef M. (1990). Somaclonal variation in tomato: effect of explant source and a comparison with chemical mutagenesis. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 80: 817–825. DOI 10.1007/BF00224199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ellul P, Garcia-Sogo B, Pineda B, Ríos G, Roig LA, Moreno V. (2003). The ploidy level of transgenic plants in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tomato cotyledons (Lycopersicon esculentum L. Mill.) is genotype and procedure dependent. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 106: 231–238. DOI 10.1007/s00122-002-0928-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fillatti JJ, Kiser J, Rose R, Comai L. (1987). Efficient transfer of a glyphosate tolerance gene into tomato using a binary Agrobacterium tumefaciens vector. Nature Biotechnology 5: 726–730. DOI 10.1038/nbt0787-726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Firsov A, Mitiouchkina T, Shaloiko L, Pushin A, Vainstein A, Dolgov S. (2020). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of chrysanthemum with artemisinin biosynthesis pathway genes. Plants 9: 537. DOI 10.3390/plants9040537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Frary A, Earle ED. (1996). An examination of factors affecting the efficiency of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tomato. Plant Cell Reports 16: 235–240. DOI 10.1007/BF01890875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fuentes AD, Ramos PL, Sánchez Y, Callard D, Ferreira A, Tiel K, Cobas K, Rodríguez R, Borroto C, Doreste V, Pujol M. (2008). A transformation procedure for recalcitrant tomato by addressing transgenic plant-recovery limiting factors. Biotechnology Journal 3: 1088–1093. DOI 10.1002/biot.200700187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guo M, Zhang YL, Meng ZJ, Jiang J. (2012). Optimization of factors affecting Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Micro-Tom tomatoes. Genetics and Molecular Research 11: 661–671. DOI 10.4238/2012.March.16.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gupta S, Van Eck J. (2016). Modification of plant regeneration medium decreases the time for recovery of Solanum lycopersicum cultivar M82 stable transgenic lines. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 127: 417–423. DOI 10.1007/s11240-016-1063-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hahn F, Mantegazza O, Greiner A, Hegemann P, Eisenhut M, Weber AP. (2017). An efficient visual screen for CRISPR/Cas9 activity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Frontiers in Plant Science 08: 1473. DOI 10.3389/fpls.2017.00039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayut SF, Bessudo CM, Levy VA. (2017). Targeted recombination between homologous chromosomes for precise breeding in tomato. Nature Communications 8: 794. DOI 10.1038/ncomms15605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Herrera-Estrella L, De Block M, Messens E, Hernalsteens JP, Van Montagu M, Schell J. (1983). Chimeric genes as dominant selectable markers in plant cells. EMBO Journal 2: 987–995. DOI 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01532.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Holsters M, de Waele D, Depicker A, Messens E, van Montagu M, Schell J. (1978). Transfection and transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Molecular and General Genetics 163: 181–187. DOI 10.1007/BF00267408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ho-Plágaro T, Huertas R, Tamayo-Navarrete MI, Ocampo JA, García-Garrido JM. (2018). An improved method for Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation of tomato suitable for the study of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Plant Methods 14: 534. DOI 10.1186/s13007-018-0304-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hwang HH, Yu M, Lai EM. (2017). Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation: biology and applications. Arabidopsis Book 15: e0186. DOI 10.1199/tab.0186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Khuong TTH, Crété P, Robaglia C, Caffarri S. (2013). Optimisation of tomato Micro-tom regeneration and selection on glufosine/Basta and dependency of gene silencing on transgene copy number. Plant Cell Reports 32: 1441–1454. DOI 10.1007/s00299-013-1456-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim H, Kim ST, Ryu J, Choi MK, Kweon J, Kang BC, Ahn HM, Bae S, Kim J, Kim JS, Kim SG. (2016). A simple, flexible and high-throughput cloning system for plant genome editing via CRISPR-Cas system. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 58: 705–712. DOI 10.1111/jipb.12474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lacroix B, Citovsky V. (2019). Pathways of DNA transfer to plants from Agrobacterium tumefaciens and related bacterial species. Annual Review of Phytopathology 57: 231–251. DOI 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee H, Kim JS. (2018). Unexpected CRISPR on-target effects. Nature Biotechnology 36: 703–704. DOI 10.1038/nbt.4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ling HQ, Kriseleit D, Ganal MW. (1998). Effect of ticarcillin/potassium clavulanate on callus growth and shoot regeneration in Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Plant Cell Reports 17: 843–847. DOI 10.1007/s002990050495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Murashige T, Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 15: 473–497. DOI 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Niedz RP, Evens TJ. (2016). Design of experiments (DOE)-history, concepts, and relevance to in vitro culture. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology–Plant 52: 547–562. DOI 10.1007/s11627-016-9786-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nonaka S, Someya T, Kadota Y, Nakamura K, Ezura H. (2019). Super-Agrobacterium ver. 4: Improving the transformation frequencies and genetic engineering possibilities for crop plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 10: 1378. DOI 10.3389/fpls.2019.01204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nonaka S, Yuhashi K, Takada K, Sugaware M, Minamisawa K, Ezura H. (2008). Ethylene production in plants during transformation suppresses vir gene expression in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. New Phytologist 178: 647–656. DOI 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02400.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ochatt SJ, Patat-Ochatt EM, Moessner A. (2011). Ploidy level determination within the context of in vitro breeding. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 104: 329–341. DOI 10.1007/s11240-011-9918-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Park S, Lee E, Heo J, Kim DH, Chun HY, Kim MC, Bang WY, Lee YK, Park SJ. (2020). Rapid generation of transgenic and gene-edited Solanum nigrum plants using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Plant Biotechnology Reports 14: 497–504. DOI 10.1007/s11816-020-00616-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Park SH, Morris JL, Park JE, Hirschi KD, Smith RH. (2003). Efficient and genotype-independent Agrobacterium-mediated tomato transformation. Journal of Plant Physiology 160: 1253–1257. DOI 10.1078/0176-1617-01103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Prihatna C, Chen R, Barbetti MJ, Barker SJ. (2019). Optimisation of regeneration parameters improves transformation efficiency of recalcitrant tomato. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 137: 473–483. DOI 10.1007/s11240-019-01583-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rai GK, Rai NP, Kumar S, Yadav A, Rathaur S, Singh M. (2012). Effects of explant age, germination medium, pre-culture parameters, inoculation medium, pH, washing medium, and selection regime on Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tomato. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology–Plant 48: 565–578. DOI 10.1007/s11627-012-9442-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Raj K, Singh R, Pandey S, Singh B. (2005). Agrobacterium-mediated tomato transformation and regeneration of transgenic lines expressing tomato leaf curl virus coat protein gene for resistance against TLCV infection. Current Science 88: 1674–1679. [Google Scholar]

Rezzonico F, Rupp O, Fahrentrapp J. (2017). Pathogen recognition in compatible plant-microbe interactions. Scientific Reports 170: 6383. DOI 10.1038/s41598-017-04792-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nature Protocols 3: 1101–1108. DOI 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shah SH, Ali S, Jan SA, Din AU, Ali GM. (2015). Piercing and incubation method of in planta transformation producing stable transgenic plants by over expressing DREB1A gene in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Mill.). Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 120: 1139–1157. DOI 10.1007/s11240-014-0670-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sharma MK, Solanke AU, Jani D, Singh Y, Sharma AK. (2009). A simple and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated procedure for transformation of tomato. Journal of Biosciences 34: 423–433. DOI 10.1007/s12038-009-0049-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shrawat AK, Becker D, Lörz H. (2007). Agrobacterium tumefaciens mediated genetic transformation of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Plant Science 172: 281–290. DOI 10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stachel SE, Nester EW, Zambryski P. (1986). A plant cell factor induces Agrobacterium tumefaciens vir gene expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 83: 379–383. DOI 10.1073/pnas.83.2.379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stavridou E, Tzioutziou NA, Madesis P, Labrou NE, Nianiou-Obeidat I. (2019). Effect of different factors on regeneration and transformation efficiency of tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum) hybrids. Czech Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding 55: 120–127. DOI 10.17221/61/2018-CJGPB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun L, Yang H, Chen M, Ma D, Lin C. (2013). RNA-seq reveals dynamic changes of gene expression in key stages of intestine regeneration in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. PLoS One 8: e69441. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0069441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun S, Kang XP, Xing XJ, Xu XY, Cheng J, Zheng SW, Xing GM. (2015). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L. cv. Hezuo 908) with improved efficiency. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 29: 861–868. DOI 10.1080/13102818.2015.1056753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Svitashev S, Schwartz C, Lenderts B, Young JK, Cigan AM. (2016). Genome editing in maize directed by CRISPR–Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nature Communications 7: 5034. DOI 10.1038/ncomms13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

The Tomato sequencing Consortium. (2012). The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit tomato. Nature 485: 635–641. DOI 10.1038/nature11119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Touchell DH, Palmer IE, Ranney TG. (2020). In vitro ploidy manipulation for crop improvement. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 1977. DOI 10.3389/fpls.2020.00722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tranchida-Lombardo V, Cigliano RA, Anzar I, Landi S, Palombieri S, Colantuono C, Bostan H, Termolino P, Aversano R, Batelli G, Cammareri M, Carputo D, Chiusano ML, Conicella C, Consiglio F, Di Agonstino M, De Palma M, Di Matteo A, Grandillo S, Sanseverino W, Tucci M, Grillo S. (2018). Whole-genome re-sequencing of two Italian tomato landraces reveals sequence variations in genes associated with stress tolerance, fruit quality and long shelf-life traits. DNA Research 25: 149–160. DOI 10.1093/dnares/dsx045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ultzen T, Gielen J, Venema F, Westerbroek A, De Haan P, Tan M, Schram A, Van Grinsven M, Golbach R. (1995). Resistance to tomato spotted wilt virus in transgenic tomato hybrids. Euphytica 85: 159–168. DOI 10.1007/BF00023944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Eck J, Keen P, Tjahjadi M. (2019). Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of tomato. Methods in Molecular Biology 1864: 225–234. DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-8778-8_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Veillet F, Perrot L, Chauvin L, Kermarrec MP, Guyon-Debast A, Chauvin JE, Nogué F, Mazier M. (2019). Transgene-free genome editing in tomato and potato plants using Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of a CRISPR/Cas9 cytidine base editor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20: 402. DOI 10.3390/ijms20020402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang T, Zhang H, Zhu H. (2019). CRISPR technology is revolutionizing the improvement of tomato and other fruit crops. Horticulture Research 6: 61. DOI 10.1038/s41438-019-0159-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Woo JW, Kim J, Kwon SI, Corvalán C, Cho SW, Kim H, Kim SG, Kim ST, Choe S, Kim JS. (2015). DNA-free genome editing in plants with preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Nature Biotechnology 33: 1162–1164. DOI 10.1038/nbt.3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu Y, Chen Y, Liang X, Wang X. (2006). An experimental assessment of the factors influencing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in tomato. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology 53: 252–256. DOI 10.1134/S1021443706020166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xu S, Lai E, Zhao L, Cai Y, Ogutu C, Cherono S, Han Y, Zheng B. (2020). Development of a fast and efficient root transgenic system for functional genomics and genetic engineering in peach. Scientific Reports 10: 487. DOI 10.1038/s41598-020-59626-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yin K, Han T, Liu G, Chen T, Wang Y, Yu AYL, Liu Y. (2015). A geminivirus-based guide RNA delivery system for CRISPR/Cas9 mediated plant genome editing. Scientific Reports 5: 321. DOI 10.1038/srep14926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang N, Roberts HM, Van Eck J, Martin GB. (2020). Generation and molecular characterization of CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations in 63 immunity-associated genes in tomato reveals specificity and a range of gene modifications. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 1473. DOI 10.3389/fpls.2020.00010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang Q, Xing HL, Wang ZP, Zhang HY, Yang F, Wang XC, Chen QJ. (2018). Potential high-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR/Cas9 in Arabidopsis and its prevention. Plant Molecular Biology 96: 445–456. DOI 10.1007/s11103-018-0709-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhao C, Lang Z, Zhu JK. (2015). Cold responsive gene transcription becomes more complex. Trends in Plant Science 20: 466–468. DOI 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Supplementary Figure 1: Comparison of cotyledon and hypocotyl explants on leaf cluster induction in tomato ‘Heinz 1706’ on four weeks. Bars denote SE, Bars with different letters are statistically different by the Student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

Supplementary Figure 2: Effects of phytohormones on leaf cluster regeneration from cotyledonary explants in tomato ‘Heinz 1706’ on four weeks. (a) Regenerated leaf clusters from explants on the media supplemented with different combinations of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and trans-zeatin (tZ), Arrows indicate leaf clusters, Scales bars indicate 1 cm; (b and c) Statistics of leaf cluster induction. Bars indicate SE (n = 105), and bars with different letters are statistically different by the LSD test (p < 0.05).

Supplementary Figure 3: Lethal effects of hygromycin B in tomato ‘Heinz 1706’ after four weeks. (a) On leaf cluster regeneration from cotyledonary explants; (b) On shoot elongation and rooting from leaf clusters; (c and d) Statistics of hygromycin B on organogenesis. Data delineate the average of three replicates, and Bars denote SE, and bars with different letters are statistically different by the LSD test (p < 0.05).

Supplementary Figure 4: Detection of the Cas9 gene in transgenic plantlets by PCR analysis. (a) ‘Heinz 1706’; (b) ‘Moneymaker’; (c) ‘Rubion’. * Indicate transgenic plantlets.

Supplementary Figure 5: Summary of changes in ploidy level of the regenerants in three tomato cultivars. The phenotype of regenerants (a) and each ploidy level (b); (c) The number of plants with normal and abnormal ploids.

Supplementary Table 1: Components of solid and liquid yeast extract peptone (YEP) media used to culture A. tumefaciens strains LB4404 and GV3101 harboring vector pHAtC

The pH of both liquid and solid YEP media was rectified to 7.5 prior to autoclaving.

Supplementary Table 2: Lists of primer sets used for PCR and qPCR analyses in this study

1Kim et al. (2016); 2Hahn et al. (2017); 3Coker and Davies (2003).

Supplementary Table 3: Assessment of different antibiotics for eliminating the agrobacteria completed their role

*Indicate that more than 65 cotyledonary explants were tested at one time, and the set of experiments were repeated at least three times.

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |