Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Perspectives and Challenges of Family Members in Providing Mental Support to Cancer Patients: A Qualitative Study in Beijing, China

1 Department of Social Sciences, Universiti Selangor, Batang Berjuntai, 45600, Selangor

2 Beijing Youth Research Association, Beijing, 100044, China

3 Sinounited Investment Group Corporation Limited Postdoctoral Programme, Beijing, 102611, China

* Corresponding Author: Lan Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Multidisciplinary Clinical Health Psychology for Cancer Experience

Psychologie clinique multidisciplinaire de la santé pour l'expérience du cancer)

Psycho-Oncologie 2024, 18(4), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.32604/po.2024.057004

Received 05 August 2024; Accepted 06 September 2024; Issue published 04 December 2024

Abstract

This study explores the perspectives and challenges faced by family members providing mental support to cancer patients in Beijing, China. The primary objective is to understand the emotional and practical roles family members undertake and the difficulties they encounter. Utilizing a qualitative research design, data were collected through semi-structured interviews with family caregivers of cancer patients. Thematic analysis revealed several key themes: the dual burden of emotional support and caregiving responsibilities, the impact on daily life and personal well-being, the role and effectiveness of external support systems, perceptions of medical staff support, and the common challenges and conflicts faced in caregiving. The findings highlight the critical need for comprehensive support systems that address both the emotional and practical needs of family caregivers. Recommendations for enhancing family-centered support programs in oncology settings are discussed.Keywords

Cancer remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, imposing a substantial burden on individuals, families, and healthcare systems. In 2020 alone, approximately 19.3 million new cancer cases were reported globally, with nearly 10 million deaths, underscoring the scale of this public health challenge. China, in particular, faces a significant portion of this burden, with the nation accounting for around 24% of new cancer cases and 30% of cancer-related deaths globally. Beijing, as a major urban center, mirrors these national trends and represents a critical focal point for understanding the complex dynamics of cancer care. Family caregivers are central to this care continuum, especially in the context of oncology, where they play a vital role in supporting patients through their treatment journeys, managing medical appointments, and providing both emotional and psychological support.

Family caregiving in oncology settings is fraught with numerous challenges, including the physical demands of care, emotional strain, and the psychological impact on caregivers. The situation is particularly intense in China, where traditional cultural values such as filial piety (孝 “xiao”) and spousal loyalty impose additional expectations on individuals. These cultural norms often compel caregivers to undertake extensive caregiving responsibilities with minimal external support, leading to significant stress, anxiety, and burnout. Caregivers in this context are not only managing the practical aspects of care but are also navigating the emotional and societal pressures that come with fulfilling these culturally prescribed roles. Despite their crucial role in the care process, there is a stark lack of adequate support systems tailored to their specific needs, which has significant implications for both the caregivers’ well-being and the quality of care provided to cancer patients.

While the challenges faced by caregivers have been extensively studied in Western contexts, there is a notable gap in the literature when it comes to understanding the experiences of caregivers in Eastern cultures, particularly in China. Most existing studies focus on caregiving in the Western world, where social support systems and cultural expectations differ markedly from those in China. There is a scarcity of research that delves into the unique pressures faced by caregivers in urban centers like Beijing, where the interplay of rapid modernization, changing family dynamics, and traditional cultural expectations creates a distinct caregiving environment. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to comprehensively examine the caregiving experience in this specific cultural and urban context, addressing the critical gap in understanding how Chinese caregivers cope with these multifaceted demands.

This study aims to explore the perspectives and challenges faced by family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing, providing insights that are currently underrepresented in the global discourse on caregiving. By focusing on the unique cultural and societal factors that influence caregiving in this region, the research seeks to inform the development of culturally sensitive support programs and policies. These interventions are crucial for improving the well-being of caregivers and, by extension, the quality of care provided to cancer patients. Through this study, we hope to contribute valuable knowledge that will enhance the support systems available to these caregivers, ultimately leading to better health outcomes for both patients and their families.

The following sections delve into various aspects of cancer care, highlighting the burdens and challenges faced by patients and their families. By examining the impact of cancer on both patients and caregivers, the literature review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted nature of cancer care and the critical need for integrated support systems.

The Mental Health in Cancer Care section, which underscores the importance of mental health support for cancer patients and their caregivers, detailing how psychological distress can affect treatment outcomes and quality of life.

In the Family Caregivers’ Roles section, the review highlights the essential roles that family caregivers play in supporting cancer patients, along with the substantial emotional, social, and physical challenges they face. Finally, the Gaps in Research section identifies the limitations of current studies, particularly the lack of research focused on the unique cultural and social context of caregiving in Beijing. By addressing these gaps, the study aims to contribute valuable insights that can inform the development of targeted interventions and support mechanisms.

Each of these sections is supported by recent literature, providing a robust foundation for understanding the complexities of cancer care and the critical need for comprehensive, culturally relevant support systems for caregivers and patients alike.

The importance of mental health support in cancer care is well-documented in the literature. Psychological distress is prevalent among cancer patients, with high rates of depression, anxiety, and stress reported across various studies. Effective mental health support has been shown to improve not only the psychological well-being of patients but also their physical health outcomes. A comprehensive review by Mehnert et al. found that integrating [1] mental health services into cancer care can lead to better adherence to treatment protocols, reduced symptom burden, and improved overall quality of life. Despite these benefits, mental health support services are often underutilized and insufficiently integrated into oncology care [1].

Recent studies further emphasize the significance of mental health in cancer care. For instance, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors report higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to their peers without cancer, leading to increased utilization of psychotherapy and mental health medications [2]. Prostate cancer survivors also face a heightened risk of mental health disorders, with depression significantly increasing mortality risk [3]. Psychological distress among cancer survivors is linked to poorer quality of care, highlighting the need for better communication and respect from healthcare providers [4].

Caregivers of cancer patients also experience considerable mental and financial stress, particularly those from low-income households. This stress impacts treatment adherence and quality of life for both patients and caregivers [5]. Furthermore, computational models have shown promise in accurately diagnosing depression and anxiety in women undergoing treatment for ovarian cancer, suggesting potential for advanced diagnostic tools in mental health care [6].

In Australia, cancer survivors face challenges in accessing and managing services for their mental and physical health needs, underscoring the importance of allied health care services like physiotherapy and psychology [7]. Perceived injustice in cancer care can exacerbate psychological distress, emphasizing the need for satisfaction with care to mitigate these effects [8].

Family caregivers are pivotal in the cancer care continuum, providing essential emotional and practical support to patients. The roles and challenges faced by family caregivers have been explored in various studies. Given et al. highlighted that caregivers often experience high levels of psychological distress, comparable to or even exceeding that of the patients they care for. The dual burden of providing care while managing their own emotional and physical health can lead to significant caregiver strain and burnout. Furthermore, caregivers frequently report feeling unprepared for their roles, lacking the necessary resources and support to effectively manage their responsibilities [9].

Recent research continues to underscore the critical roles and substantial challenges faced by family caregivers. Emotional and practical support for family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer is essential, as they experience considerable psychological distress and caregiver strain [10]. Caregiver burden is multifaceted, encompassing emotional, social, and physical stressors, which can lead to significant strain [11]. Caregivers often face high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, further complicating their ability to provide effective care [12].

The impact of caregiving on the mental health and quality of life of caregivers is profound. For instance, listening to self-chosen music has been shown to improve the quality of life and satisfaction with care among family caregivers of terminal cancer patients [13]. Similarly, caregivers of adolescents and young adults with cancer experience high distress and diminished quality of life, particularly in partners [14]. Interventions such as pictorial education handouts can enhance self-efficacy in caregivers, improving their ability to manage care tasks effectively [1].

Comparison with current literature

The caregiving experience for cancer patients in Eastern cultures, particularly in China, presents distinct challenges and dynamics compared to Western contexts. While global literature on caregiving highlights universal themes such as stress, emotional burden, and the need for support systems, significant differences emerge when considering cultural values, societal expectations, and healthcare infrastructures.

In Western societies, caregiving often involves a broader support network that includes professional caregivers and community services. The cultural emphasis on individualism and autonomy in these societies allows for a more distributed caregiving model, where responsibilities are shared among family members and external support systems. Studies from Western countries frequently emphasize the availability and utilization of formal support services, such as counseling, respite care, and financial aid programs [9,11].

In contrast, the caregiving responsibility in China, heavily influenced by Confucian values like filial piety (孝 “xiao”) and spousal loyalty, falls primarily on immediate family members, often the spouse. These cultural norms create a scenario where caregiving is not merely a duty but a moral obligation, deeply intertwined with the caregiver’s identity and social expectations. This cultural difference significantly impacts the mental and physical burden on caregivers, who may feel compelled to undertake these roles without external help, driven by the fear of social judgment and the desire to fulfill their perceived duties [15].

Western healthcare systems typically offer a more structured and supportive environment for caregivers. The presence of multidisciplinary teams, including psychologists, social workers, and patient advocates, is common in Western oncology settings. These systems are designed to provide holistic care that addresses not just the physical needs of the patient but also the psychological and social aspects of both the patient and their family caregivers [16]. Conversely, the healthcare system in China, particularly in urban centers like Beijing, is still evolving in its provision of comprehensive support to caregivers. While medical care is advanced, the integration of psychological and social support services is less developed. Caregivers often report a lack of communication and empathy from medical staff, further exacerbating their stress and sense of isolation. The reliance on traditional family structures for support places additional strain on caregivers, who may not have access to the same level of external resources as their Western counterparts [17].

In Western contexts, there is also broader acceptance of seeking external help, such as counseling and support groups. The stigma surrounding mental health is gradually decreasing, allowing caregivers to access necessary resources without fear of judgment. Moreover, the role of professional caregivers and community support is more established, providing caregivers with opportunities to share their burdens [18]. In China, however, caregivers may be more reluctant to seek help due to cultural stigmas associated with mental health and the expectation to endure hardships quietly (吃苦 “chī kǔ”). This cultural attitude often leads caregivers to handle their responsibilities independently, resulting in higher levels of burnout and psychological distress. The lack of formal support networks exacerbates these issues, highlighting a critical gap in the healthcare system’s ability to support caregivers effectively [19].

While there is substantial research on the roles and challenges of family caregivers in oncology, there are notable gaps, particularly in the context of Beijing. Much of the existing literature is based on studies conducted in Western countries, which may not fully capture the cultural and social nuances of caregiving in China. Additionally, there is a scarcity of focused research on the specific mental support needs of family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing. Addressing these gaps is crucial for developing culturally relevant support systems that can effectively assist caregivers in this unique context [11].

Recent studies have highlighted the need for culturally tailored interventions to support family caregivers in non-Western contexts. For instance, caregivers in Uganda reported significant psychological distress and caregiving strain, exacerbated by health system tensions and a lack of support [10]. This underscores the importance of understanding the unique challenges faced by caregivers in different cultural settings.

Furthermore, research focusing on the mental health of family caregivers in palliative contexts has revealed that these caregivers experience multidimensional burdens, including emotional, social, and economic stressors. However, the specific needs and support mechanisms for caregivers in Beijing remain underexplored.

Addressing these research gaps is critical for developing effective support systems. For example, integrating psychoeducational interventions and mental health assessments at the point-of-care can significantly benefit caregivers [12]. Additionally, innovative approaches such as mobile health applications have shown promise in enhancing the quality of life for caregivers.

By identifying and addressing these research gaps, this study aims to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the support needs of family caregivers in Beijing, ultimately enhancing the quality of care for both caregivers and cancer patients.

In conducting this study, particular attention was given to ensuring the diversity and representativeness of the sample population. The research team employed purposive sampling techniques to select participants who were actively engaged in the caregiving of family members diagnosed with cancer. This approach was chosen to capture a broad spectrum of experiences, taking into account varying degrees of caregiving intensity, socioeconomic backgrounds, and access to healthcare resources. The recruitment process involved close collaboration with local healthcare providers and community organizations in Beijing, which facilitated the identification of eligible participants who met the study’s inclusion criteria. This methodological rigor was essential in obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by family caregivers across different contexts within the urban environment of Beijing.

This study was meticulously designed and conducted following well-established guidelines to ensure rigor, transparency, and methodological integrity in qualitative research. To guide our reporting process, we adhered to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR), as synthesized by O’Brien et al. [20], which offers a comprehensive framework that ensures all relevant aspects of the study are thoroughly documented. This framework was instrumental in structuring our study, from the initial design through to the final reporting, allowing us to clearly articulate the research process and findings. In analyzing the qualitative data, we employed the step-by-step process of thematic analysis as described by Naeem et al. [21]. This approach involved systematically coding and identifying key themes from the interview data, which enabled us to develop a conceptual model that accurately reflects the experiences and challenges faced by the family caregivers involved in this study. The thematic analysis process was critical not only for maintaining the integrity of the data but also for allowing an in-depth exploration of the underlying patterns and themes that emerged from the caregivers’ narratives. Furthermore, we followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ), a 32-item checklist developed by Tong et al. [22], which is widely used for interviews and focus groups in qualitative research. The COREQ checklist ensured that all critical elements of the study design, data collection, and analysis were meticulously followed, providing a structured approach that contributed to the robustness and reliability of our findings. By integrating these guidelines—SRQR, thematic analysis, and COREQ—into the design and execution of our study, we ensured that the research was conducted with the highest standards of qualitative research. This rigorous approach not only bolstered the credibility of our findings but also ensured that our study makes a meaningful contribution to the field, offering valuable insights that are both methodologically sound and contextually relevant.

This study is set in Beijing, the capital of China, a city that is emblematic of the country’s rapid urbanization and modernization. Beijing, as a major urban center, presents a unique blend of traditional Chinese cultural values and modern societal pressures, making it an ideal setting to explore the intersection of these influences on family caregiving. The city’s healthcare infrastructure is among the most advanced in the country, attracting patients from across the nation for specialized cancer treatment. However, this concentration of advanced healthcare services also highlights the significant emotional, physical, and financial burdens placed on local families who are tasked with caring for their loved ones undergoing cancer treatment.

In Beijing, the caregiving experience is shaped not only by the demands of the healthcare system but also by the socio-economic dynamics of living in a rapidly developing metropolis. The study examines how these urban pressures, combined with traditional expectations of family responsibility, create a distinct caregiving environment. This setting allows the research to delve deeply into how urbanization and modernization are altering family structures and caregiving roles, particularly as extended families become less common and nuclear families more prevalent. By focusing on Beijing, the study captures the experiences of caregivers in a city that reflects both the ancient cultural roots and the contemporary changes that are reshaping caregiving in China.

This study employs a qualitative research design, utilizing thematic analysis to explore the perspectives and challenges faced by family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing. Qualitative research is particularly well-suited for this inquiry as it allows for an in-depth understanding of personal experiences and social contexts, providing rich, detailed insights into the caregivers’ roles and difficulties. Thematic analysis has been effectively used in similar studies to identify key themes related to caregiver experiences and challenges [23].

The participants in this study were family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing. A total of 15 families were selected through purposive sampling, a technique used to identify and recruit participants who have specific characteristics relevant to the research questions.

Let n represent the number of participants:

Inclusion criteria included being a primary caregiver for a family member diagnosed with cancer and residing in Beijing. A diverse group of caregivers was selected to capture a broad range of experiences and perspectives. Similar studies have shown the importance of including diverse participants to understand the varying dynamics and challenges faced by caregivers.

This study is grounded in the Stress and Coping Theory developed by Lazarus and Folkman [24]. This theory is particularly relevant for exploring the experiences of family caregivers, as it provides a framework for understanding how individuals perceive and respond to stressful situations. According to the Stress and Coping Theory, caregivers assess the demands placed upon them (primary appraisal) and their resources to cope with these demands (secondary appraisal). The interaction between these appraisals influences their coping strategies, which can be problem-focused (aimed at managing the problem) or emotion-focused (aimed at regulating emotional responses).

Applying this theory to the study allows us to explore how caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing navigate their roles and responsibilities, the challenges they face, and the support systems they rely on. By analyzing the caregivers’ experiences through this theoretical lens, we gain a deeper understanding of their coping mechanisms and the factors that contribute to their well-being or distress.

This theoretical framework supports the use of thematic analysis in this qualitative study, as it helps to identify the key themes related to caregivers’ stressors, coping strategies, and outcomes. It also provides a structured approach to interpreting the data, ensuring that the findings are not only descriptive but also explanatory, linking the caregivers’ experiences to broader psychological theories.

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, which offer a balance between guided questions and the flexibility to explore topics in more depth as they arise during the conversation. This method allows participants to express their thoughts and experiences in their own words, providing valuable qualitative data. Each interview was conducted in a private setting to ensure confidentiality and comfort for the participants.

Let t represent the time in minutes for each interview, with t ranging from 60 to 90 min:

The total time spent on interviews T can be calculated as:

where:

• T is the total time spent on interviews.

• n is the number of participants.

• tmin is the minimum time of each interview.

• tmax is the maximum time of each interview.

The total time spent on interviews was calculated using the formula

The interviews were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent for accurate transcription and analysis. Semi-structured interviews are a common and effective method for collecting detailed qualitative data in similar studies [6].

The data collected from the interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis, a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within qualitative data.

Thematic analysis was selected as the primary method for data analysis in this study due to its flexibility and ability to identify, analyze, and report patterns within qualitative data. This approach is particularly well-suited for exploring complex, subjective experiences, such as those of family caregivers in Beijing, as it allows for a deep and nuanced understanding of their challenges and perspectives. Thematic analysis also facilitates the organization and interpretation of data in a way that can capture the richness and diversity of participants’ narratives, making it an ideal choice for a study focused on the emotional and practical roles of caregivers. This method’s emphasis on themes and patterns aligns with the study’s objective to uncover commonalities and differences in caregivers’ experiences, which are crucial for developing culturally sensitive support programs. The process involved several steps:

1. Familiarization with the Data: Transcribing the interviews, reading and re-reading the transcripts, and noting initial ideas.

2. Generating Initial Codes: Systematically coding interesting features of the data across the entire dataset and collating data relevant to each code.

Let C represent the total number of initial codes generated:

where ci is the number of codes from each interview.

3. Searching for Themes: Collating codes into potential themes and gathering all data relevant to each potential theme.

4. Reviewing Themes: Checking if the themes work in relation to the coded extracts and the entire dataset, generating a thematic map of the analysis.

5. Defining and Naming Themes: Ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme and the overall story the analysis tells, generating clear definitions and names for each theme.

6. Producing the Report: Selecting vivid, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, relating the analysis back to the research questions and literature, and producing a scholarly report of the analysis.

This systematic approach ensures a thorough and rigorous analysis of the data, uncovering key themes and patterns in the experiences of family caregivers. Thematic analysis has been widely used in qualitative research to provide detailed and nuanced insights into complex social phenomena.

This study was conducted within the framework of an anti-cancer organization, focusing on the psychological perspectives and challenges faced by family members who provide support to cancer patients. As the research did not involve medical interventions, clinical procedures, or sensitive patient data, formal ethical approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Research Ethics Committee was not required.

However, the research adhered to established ethical principles in the field of psychology. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Participants were fully informed about the purpose of the research, the nature of their participation, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence. Confidentiality was strictly maintained, with all data being anonymized to protect the identity of the participants.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines provided by the hosting organization, which align with standard practices in psychological research. These guidelines ensured that the dignity, privacy, and autonomy of the participants were respected throughout the research process.

The results of this study reveal a complex landscape of roles and responsibilities undertaken by family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing. These caregivers perform various tasks, including providing emotional support, managing household duties, and offering financial assistance. The impact of these responsibilities on caregivers’ well-being is significant, with many reporting physical fatigue and psychological stress.

Support systems for caregivers vary widely, with some relying on family and spiritual practices, while others lack external support. The perceptions of medical staff support are mixed, indicating a need for better communication and empathy from healthcare providers. Additionally, caregivers face numerous challenges, including navigating healthcare systems, financial burdens, and societal stigma.

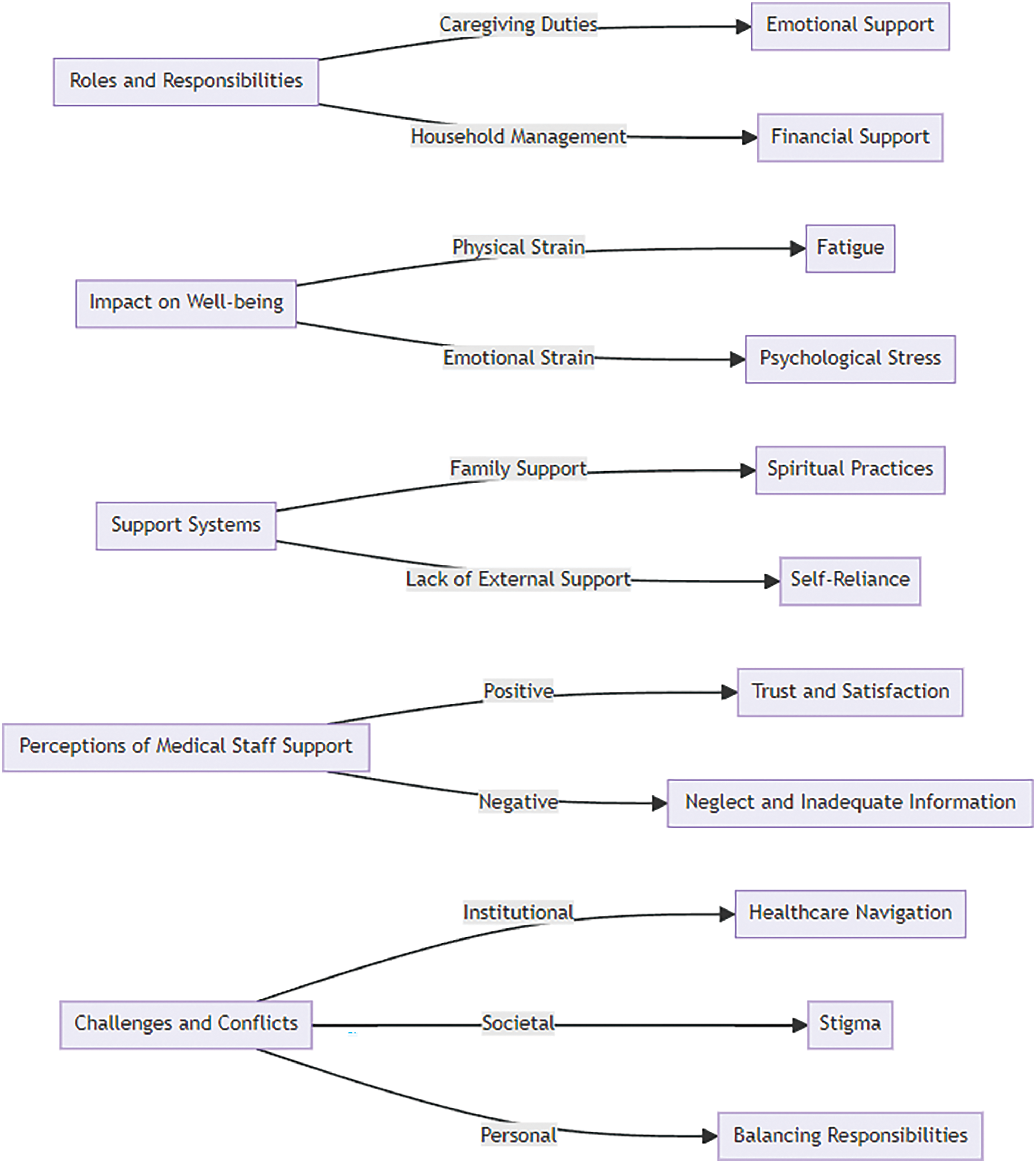

The Fig. 1 provides a visual summary of the key themes and findings from the study, offering a comprehensive overview of the diverse experiences and significant challenges faced by family caregivers. This summary highlights the critical areas where support systems need improvement to better assist caregivers in their vital roles.

Figure 1: Key themes and findings in family caregiving for cancer patients.

This Fig. 1 presents a hierarchical diagram summarizing the key themes and findings from the study. It visually organizes the primary roles and responsibilities undertaken by family caregivers, the impact of caregiving on their well-being, the support systems available to them, their perceptions of medical staff support, and the challenges and conflicts they face. This diagram provides a concise overview of the multifaceted experiences of family caregivers, highlighting the complexity and diversity of their roles and the significant challenges they encounter.

Participant demographics and support systems

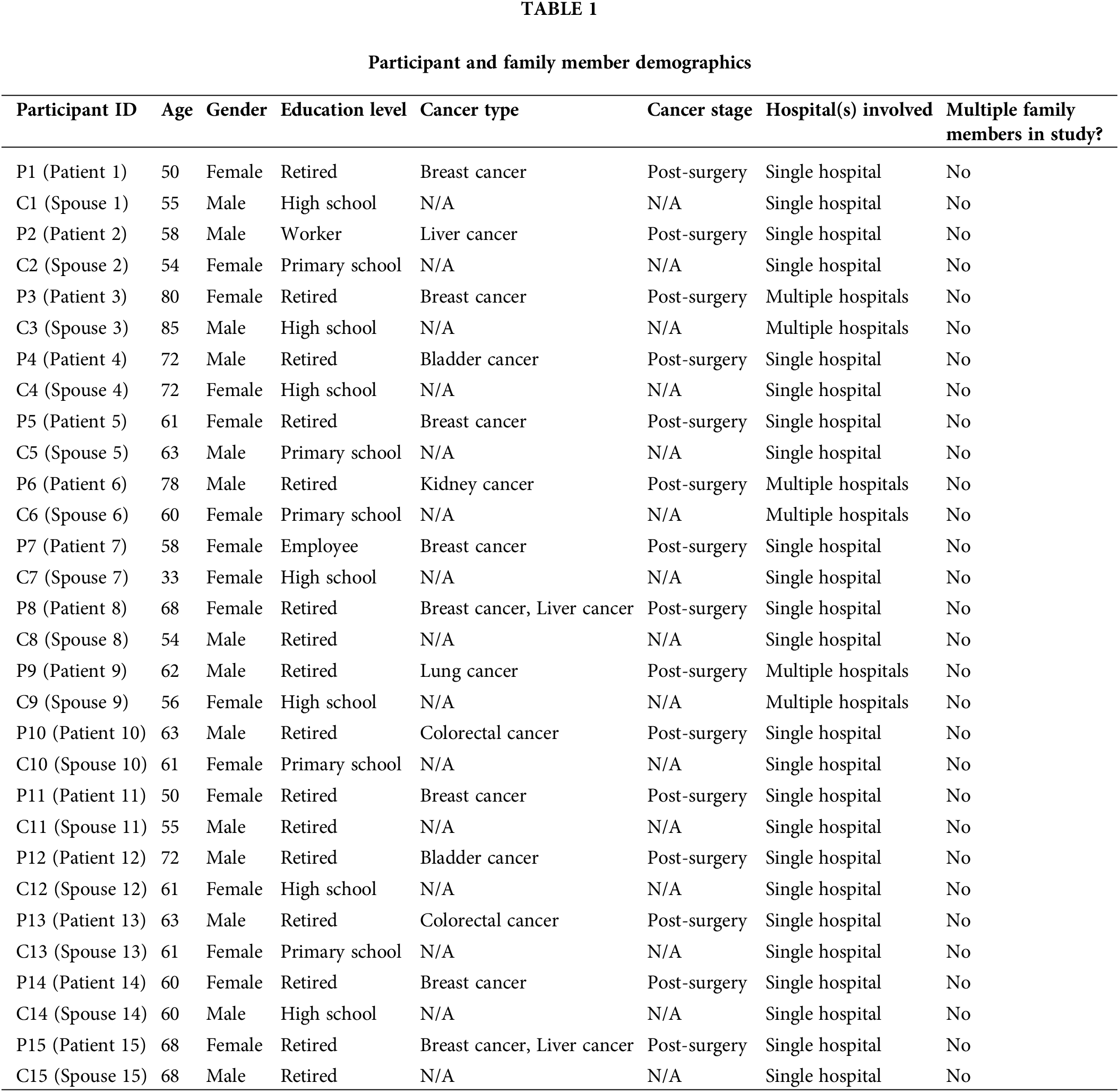

Table 1 provides an overview of the demographic characteristics of the study participants and their family members.

This Table 1 accurately reflects the demographics of all 13 participants and their corresponding family members. The emotional burden experienced by caregivers is influenced not only by the nature and stage of the patient’s cancer but also by the number of caregivers involved. In our study, each cancer patient was primarily cared for by a single family member, typically their spouse. This aligns with traditional cultural expectations in Beijing, where the duty of care is often perceived as the responsibility of the spouse. However, the involvement of multiple caregivers could potentially distribute the emotional and physical load, reducing the individual burden experienced by a single caregiver.

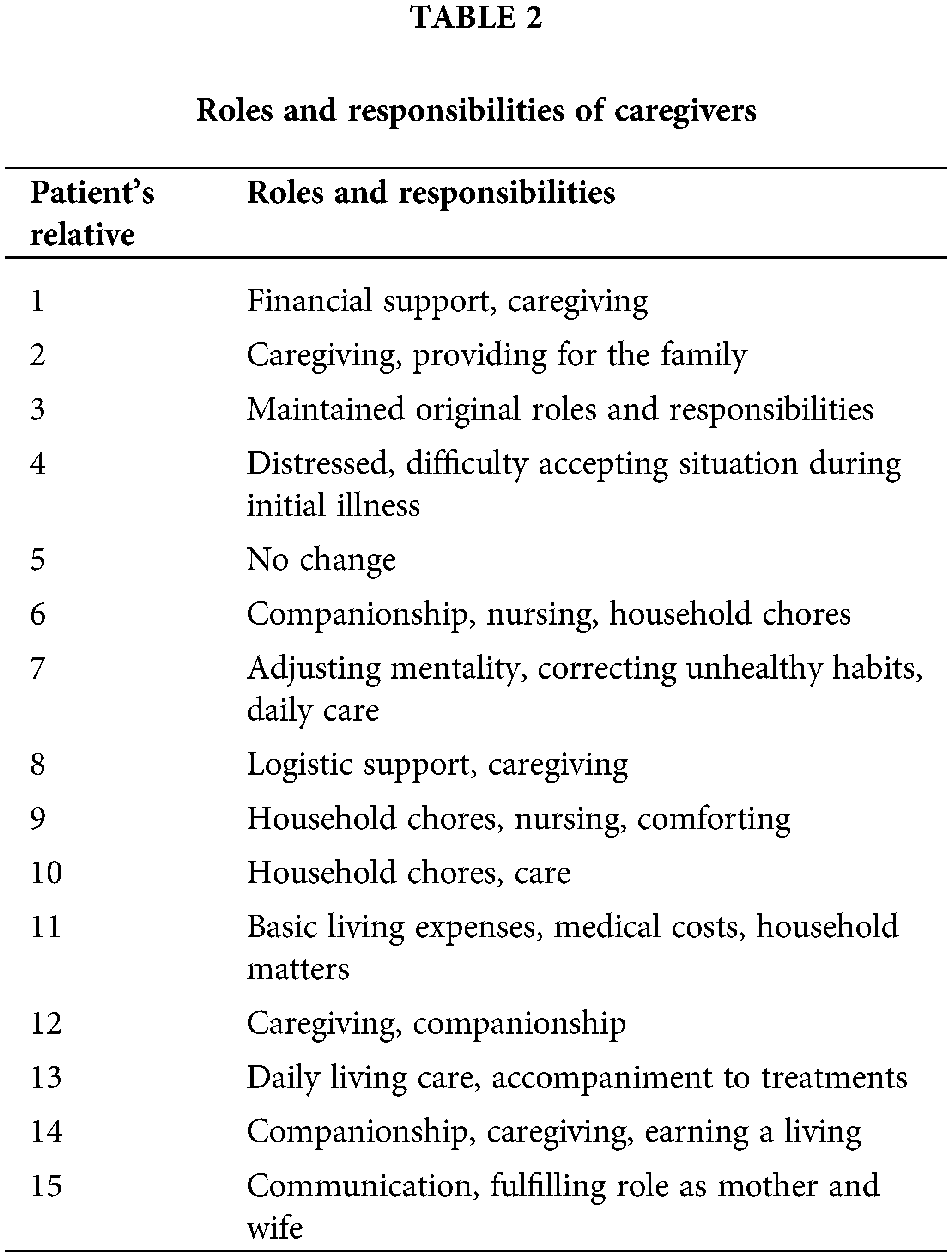

Roles and responsibilities undertaken by caregivers

This table reflects the diverse backgrounds of the participants, with most caregivers being the spouse of the cancer patient, aligning with traditional caregiving roles in Beijing.

Family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing take on a variety of roles and responsibilities. These roles often include financial support, providing direct care, maintaining household duties, and offering emotional support. Some caregivers reported their primary role as providing financial support and caregiving, while others mentioned continuing with their usual responsibilities without significant change. For instance, one caregiver noted, “Responsible for financial support and caregiving,” while another mentioned, “Companionship nursing household chores” (Patient 6’s Relative). This diversity in roles highlights the multifaceted nature of caregiving, which can range from logistical support to intimate acts of companionship and comfort.

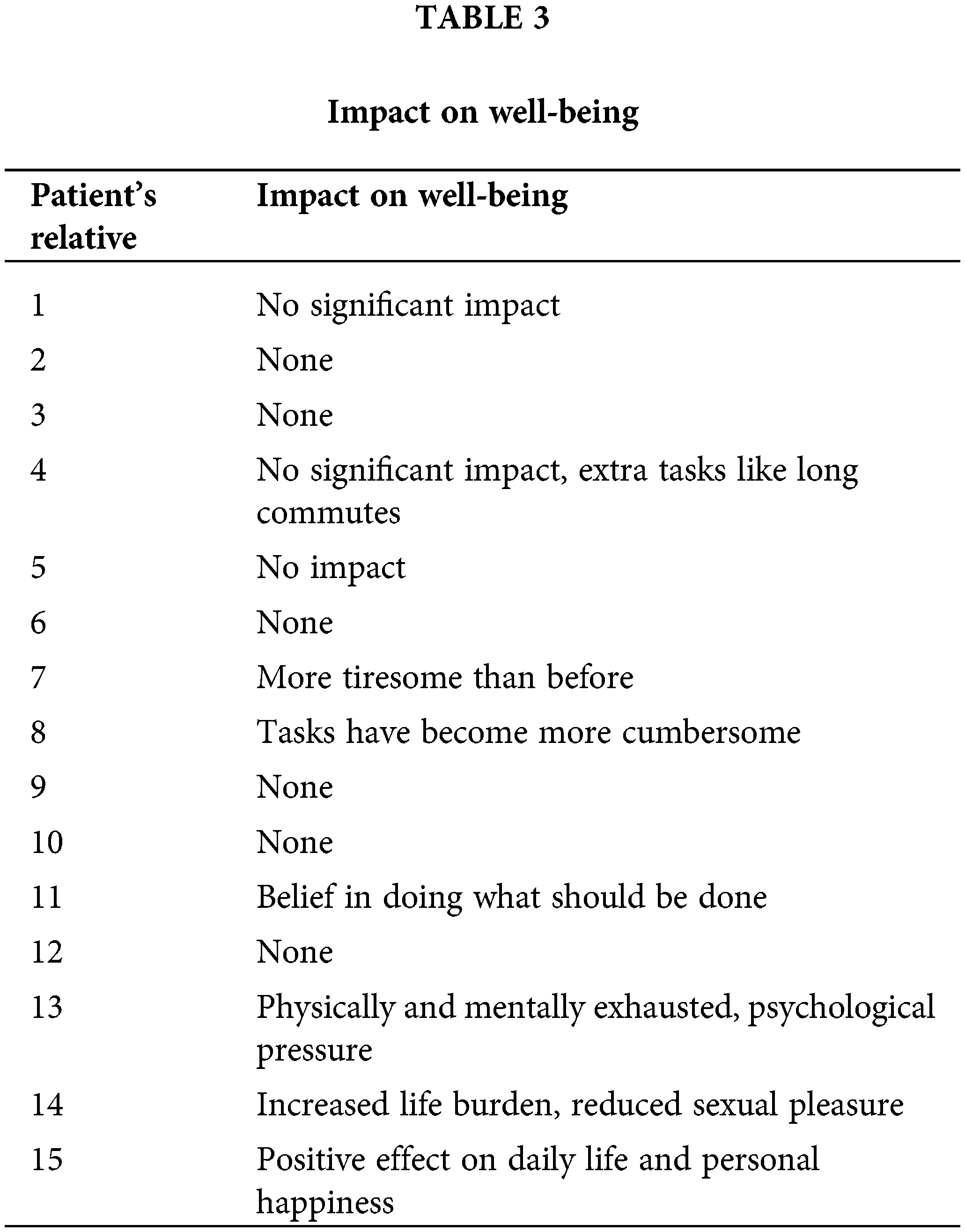

Impact on daily life and personal well-being

This table reflects the diverse backgrounds of the participants, with most caregivers being the spouse of the cancer patient, aligning with traditional caregiving roles in Beijing.

The Tables 1 and 2’s data indicate that while some caregivers reported minimal impact, others experienced significant physical and emotional strain, underscoring the varied experiences among caregivers.

The impact of caregiving on daily life and personal well-being varies among caregivers. While some reported no significant impact, others experienced increased fatigue, psychological pressure, and changes in personal life. For example, in Table 3, patient 13’s relative stated, “Physically and mentally exhausted with great psychological pressure.” Some caregivers found the tasks more cumbersome, indicating a strain on their daily routines and personal health.

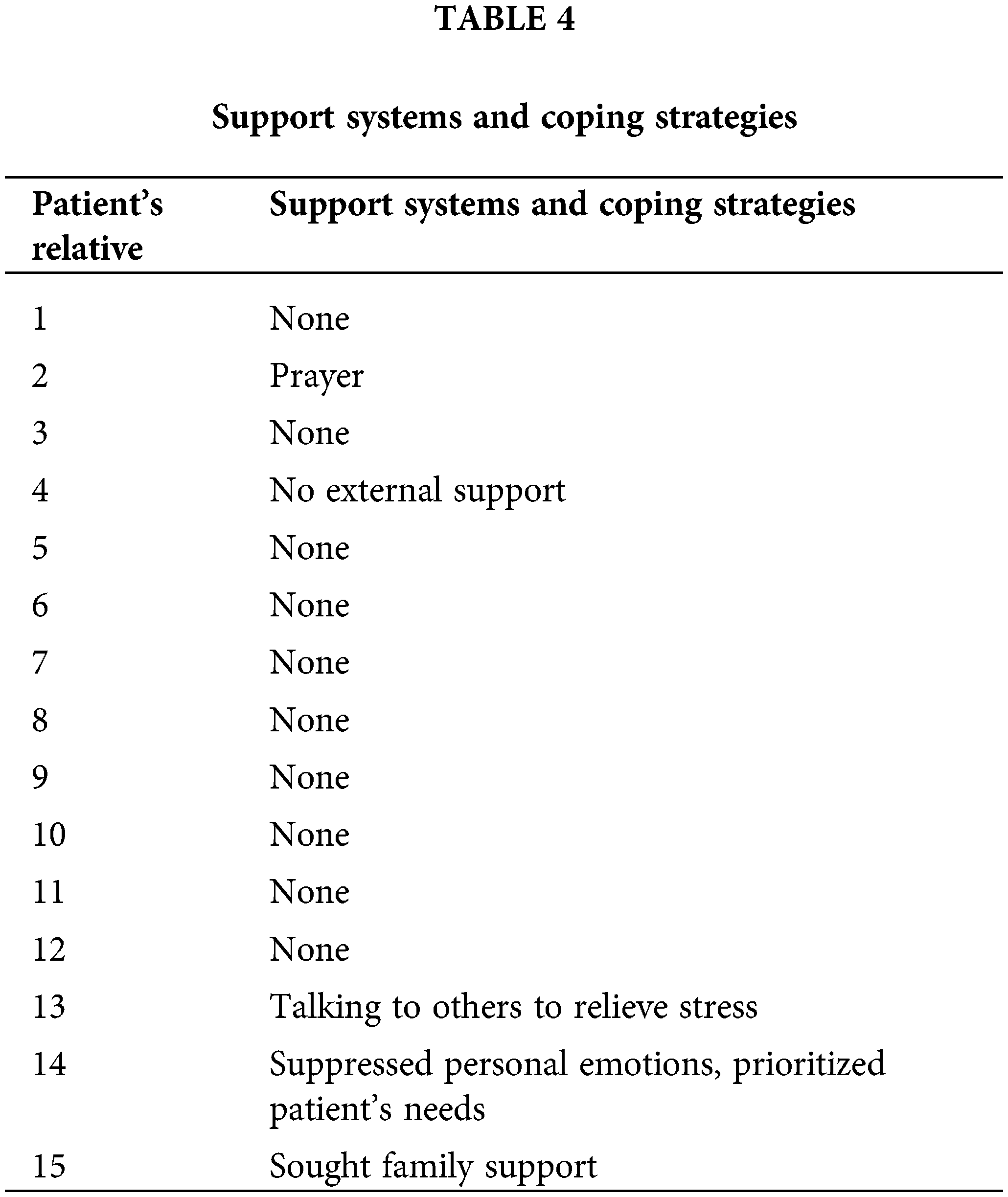

Table 4 details the support systems and coping strategies employed by caregivers.

The table illustrates that many caregivers lack external support, relying heavily on personal resilience and informal networks. Support systems for caregivers vary widely. While some caregivers received substantial support from family and friends, others relied on their own resilience. Spiritual practices such as prayer, talking to others to relieve psychological stress, and seeking family support were some of the strategies employed. Notably, many caregivers did not seek external support, reflecting either a lack of available resources or a preference for handling the responsibilities independently.

Perceptions of medical staff support

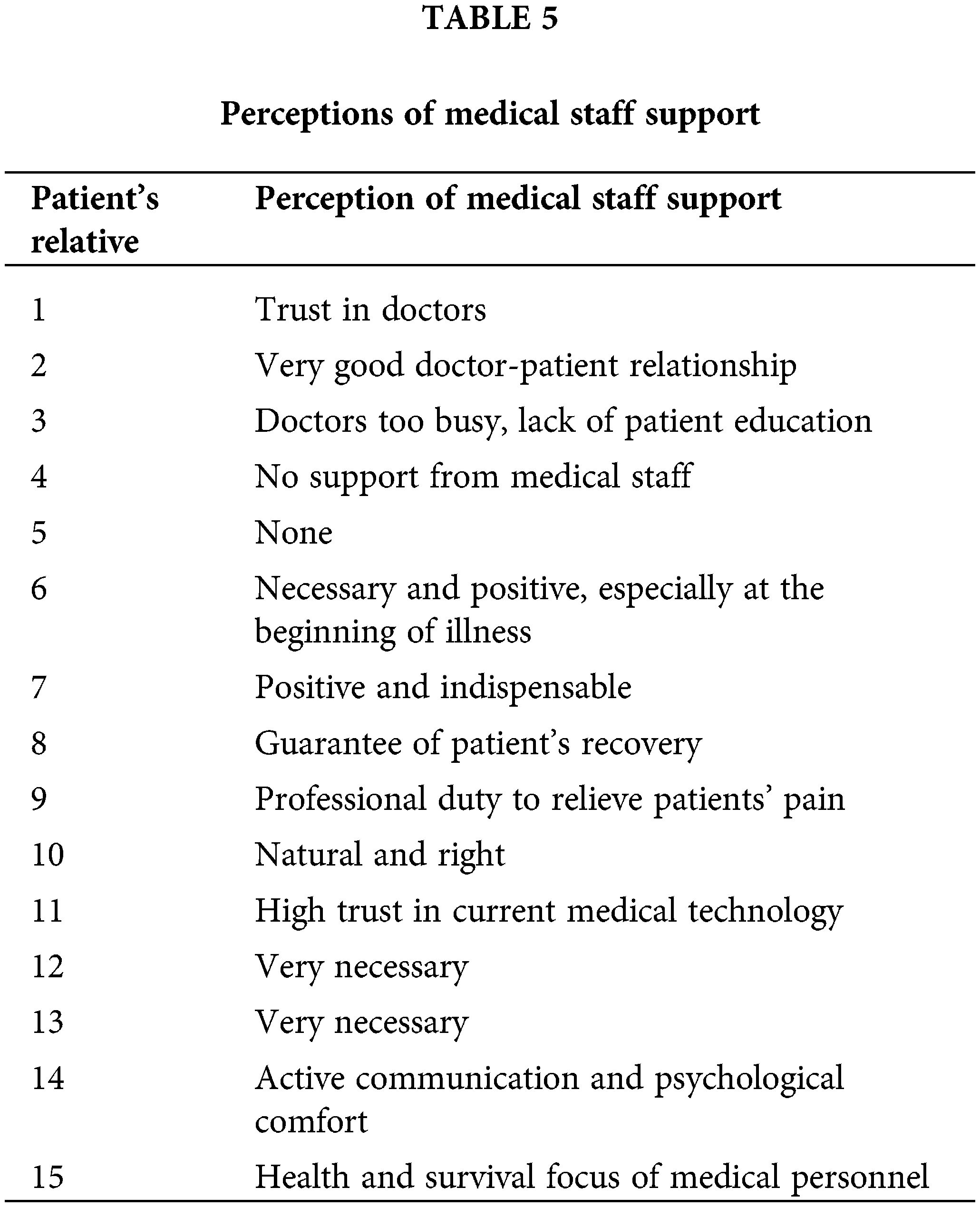

Table 5 captures the caregivers’ perceptions of the support received from medical staff.

Caregivers’ perceptions varied, with some expressing satisfaction and others highlighting the need for better communication and support from healthcare providers. Caregivers’ perceptions of support from medical staff ranged from highly positive to critical. Some caregivers expressed trust and satisfaction with the support provided by medical staff, highlighting effective communication and collaboration. Others felt neglected or inadequately informed, indicating a need for improved empathy and engagement from healthcare providers. Positive interactions with medical staff were often associated with reduced stress and better coping among caregivers.

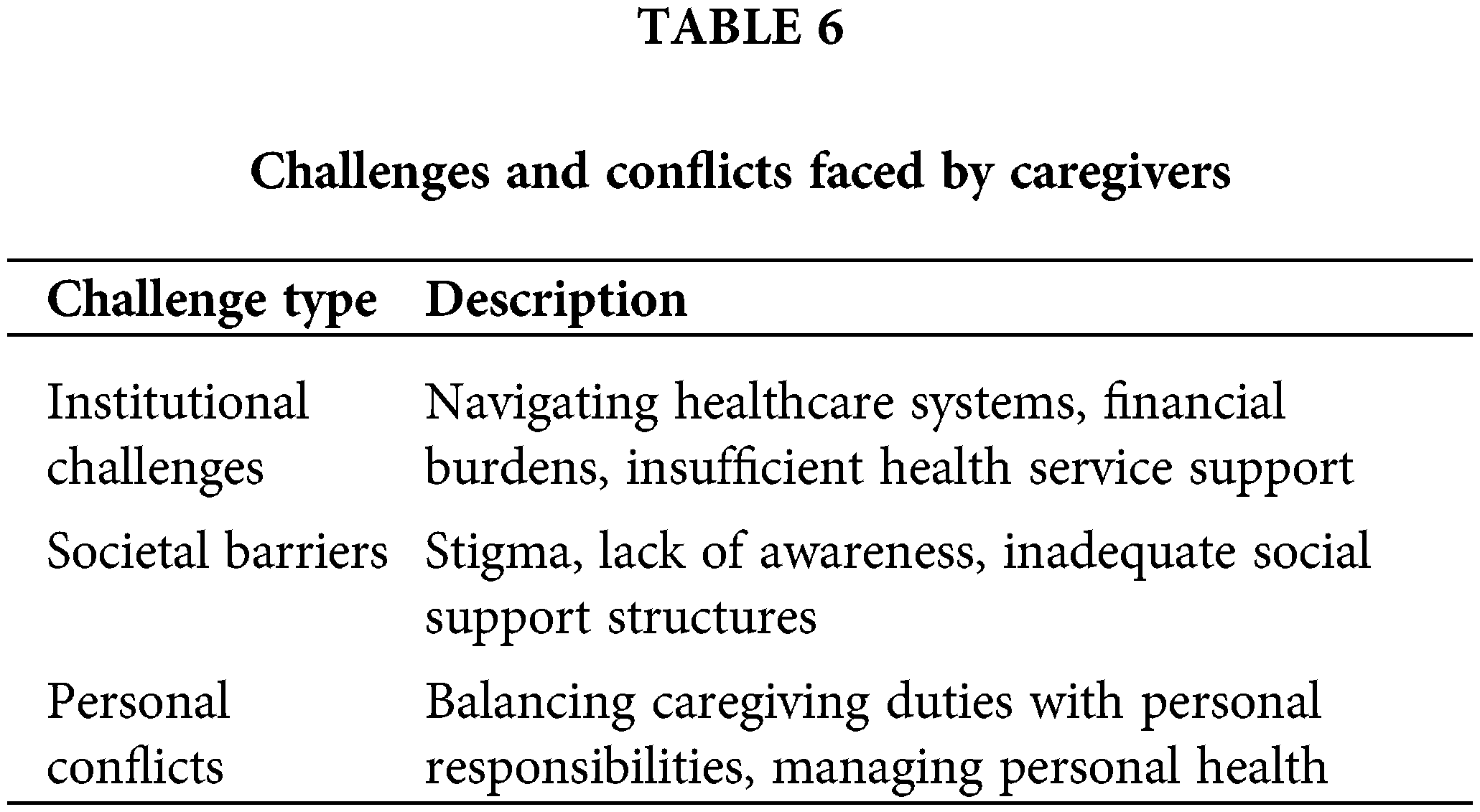

Table 6 outlines the challenges and conflicts encountered by caregivers during the caregiving process.

These challenges, ranging from institutional barriers to personal conflicts, reflect the complexity of the caregiving experience in Beijing.

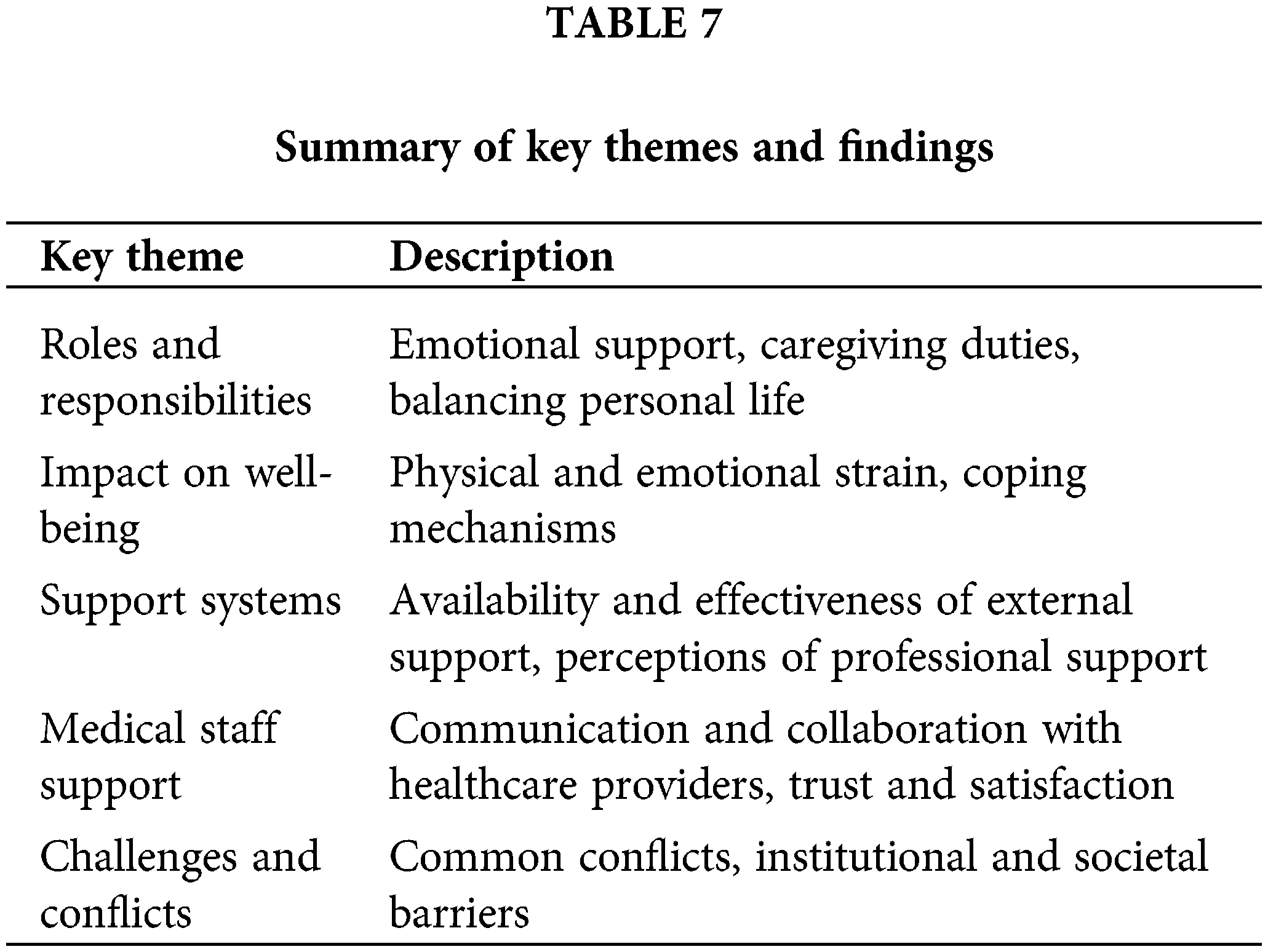

Table 7 summarizes the key themes and findings from the study.

This summary provides a comprehensive overview of the critical areas where caregivers face challenges, emphasizing the need for improved support systems.

Caregivers face several challenges and conflicts, both institutional and societal. These include navigating complex healthcare systems, financial burdens, and societal stigma. The caregivers often prioritize the patient’s needs over their own, leading to emotional and physical strain. The institutional challenges highlight the need for more comprehensive support systems that address these multifaceted issues.

These tables and illustrations provide a comprehensive overview of the key findings, highlighting the diverse experiences and challenges faced by family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing. The results emphasize the need for improved support systems, better communication from medical staff, and greater societal awareness to alleviate the burden on caregivers.

This study provides critical insights into the multifaceted challenges faced by family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing, highlighting the intersection of cultural expectations, healthcare dynamics, and personal resilience. The findings underscore the profound emotional and physical toll that caregiving exerts on individuals, particularly within a cultural framework that emphasizes family loyalty and self-sacrifice. Additionally, the variability in available support systems, both formal and informal, suggests a significant gap in the provision of comprehensive caregiver assistance. These results not only illuminate the lived experiences of caregivers but also point to the need for tailored interventions that consider the unique sociocultural context of caregiving in China. By addressing these gaps, there is an opportunity to enhance caregiver well-being and, by extension, improve patient care outcomes.

The findings of this study reveal a multifaceted experience for family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing, shaped by deep-rooted cultural values and societal expectations. In Chinese culture, marriage is not only a union of two individuals but also a lifelong commitment that extends to caring for one’s spouse through illness and hardship. This concept is deeply embedded in the cultural expectation of mutual support within a marriage, known as “夫妻之道” (fūqī zhī dào), which emphasizes the duty of care, loyalty, and support between husband and wife.

This cultural expectation places a significant burden on spouses, who often take on the role of primary caregiver when their partner is diagnosed with a serious illness like cancer. The study’s findings, where most caregivers are spouses, reflect this traditional view of marriage responsibilities. These caregivers not only provide physical care but also bear the emotional and financial responsibilities associated with long-term illness. This aligns with existing literature that highlights the significant burden borne by caregivers in oncology settings [7,9], but in the context of Chinese culture, this burden is further intensified by societal expectations and the moral obligations tied to marriage.

Interestingly, the study also found that fewer children were acting as primary caregivers for their parents than might be expected, given the traditional value of filial piety (孝 “xiao”). Filial piety is a cornerstone of Chinese culture, emphasizing the responsibility of children to care for their aging parents. The lower-than-expected involvement of children in caregiving roles may reflect the changing dynamics within modern Chinese families, where younger generations might be more focused on their careers or may live far from their parents due to urbanization and migration trends. This shift suggests a potential weakening of traditional caregiving roles, which could have significant implications for elder care in China.

The variability in support systems and the reliance on personal resilience among caregivers also reflect the broader cultural tendency to endure hardships quietly, often referred to as “吃苦” (chī kǔ), or enduring suffering. Many caregivers may feel compelled to manage their roles without seeking external help, driven by a sense of duty and the desire to protect their spouse’s dignity. This stoic approach can lead to significant emotional and physical tolls, echoing findings from Mehnert et al. [25], who emphasized the importance of accessible support systems. The mixed perceptions of medical staff support highlight a critical gap in the provision of culturally sensitive care. While there is a high regard for medical professionals in Chinese culture, caregivers expect more empathetic communication and holistic care that addresses the emotional as well as the physical needs of both the patient and the caregiver [1].

The results of this study reveal a complex landscape of roles and responsibilities undertaken by family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing. These caregivers perform various tasks, including providing emotional support, managing household duties, and offering financial assistance. As summarized in Table 2, the roles of caregivers ranged from logistical support to intimate acts of companionship and comfort. For example, one caregiver noted being “responsible for financial support and caregiving,” while another mentioned “companionship, nursing, and household chores.”

The impact of these responsibilities on caregivers’ well-being is significant, with many reporting physical fatigue and psychological stress. As shown in Table 3, while some caregivers reported no significant impact, others experienced increased fatigue, psychological pressure, and changes in their personal lives. For instance, one caregiver described feeling “physically and mentally exhausted, with great psychological pressure.”

Support systems for caregivers varied widely, with some relying on family and spiritual practices while others lacked external support. Table 4 outlines the support systems and coping strategies employed by caregivers, such as prayer or talking to others to relieve psychological stress. Notably, many caregivers did not seek external support, which reflects either a lack of available resources or a preference for handling responsibilities independently.

Caregivers’ perceptions of medical staff support were mixed, indicating a need for better communication and empathy from healthcare providers. Table 5 presents caregivers’ perceptions, ranging from high trust in doctors to feelings of neglect due to the busy schedules of healthcare professionals.

Additionally, caregivers faced numerous challenges, including navigating healthcare systems, financial burdens, and societal stigma. Table 6 details the challenges and conflicts faced by caregivers, highlighting the institutional and personal barriers that exacerbate the caregiving burden.

These tables and the corresponding descriptions in the text provide a comprehensive overview of the diverse experiences and significant challenges faced by family caregivers, emphasizing the need for improved support systems and better communication from medical staff to alleviate the burden on caregivers.

The findings of this study reveal the complex and multifaceted roles that family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing undertake, including emotional support, financial management, and daily care responsibilities. The significant physical and emotional toll on caregivers, as demonstrated by the increased reports of fatigue and psychological stress, aligns with existing literature on caregiver burden in oncology settings. Studies such as those by Given et al. [26] similarly highlight the high levels of stress and anxiety experienced by caregivers. However, the unique cultural context in Beijing, where traditional values such as filial piety and spousal loyalty are deeply ingrained, exacerbates these burdens. The strong sense of duty and responsibility, often accompanied by minimal external support, places additional pressure on caregivers, distinguishing their experience from those in Western contexts.

Comparison with current literature

This study’s results contribute to the broader discourse on caregiving in oncology by highlighting the cultural nuances that influence the caregiving experience in China. Unlike Western studies that often report a more distributed caregiving model among family members or reliance on external support systems, our findings underscore the predominance of spousal caregiving in Beijing, driven by cultural expectations. For instance, the study by Li et al. [27] discusses how the shift from extended to nuclear families in China is altering traditional caregiving roles, but our research shows that the primary responsibility still heavily falls on spouses. Furthermore, while Western literature frequently emphasizes the availability of formal support services, this study reveals a significant gap in such services in Beijing, with many caregivers relying solely on their personal resilience and informal support networks.

The implications of these findings for healthcare practice and policy in China are significant, particularly in the context of traditional marriage responsibilities and the evolving role of children in caregiving. Firstly, there is a clear need for culturally sensitive support systems that recognize the unique challenges faced by caregivers within the context of marriage. Healthcare providers should be trained to understand the cultural dynamics that influence caregiving roles, particularly the pressures on spouses to fulfill their duties without complaint. This training should include an emphasis on empathetic communication and the importance of providing emotional support to caregivers, who may be reluctant to express their needs due to cultural norms.

The finding that fewer children are taking on caregiving roles than expected suggests a need to re-evaluate how elder care is approached in China. As traditional family structures evolve, there may be a growing need for formal caregiving services and support systems that can step in where familial support is lacking. This could involve the development of government or community-based elder care programs that provide both financial and practical assistance to families.

Policies should also focus on reducing the financial burden on families, especially given the traditional expectation that a spouse will bear the majority of caregiving responsibilities. The Chinese healthcare system could benefit from more comprehensive insurance schemes or government-subsidized programs that alleviate the financial strain on low-income families. Furthermore, public health initiatives should promote awareness of available support resources, encouraging caregivers to utilize these services without fear of stigma or cultural judgment.

Additionally, there is a need to develop caregiver support programs that are tailored to the Chinese context, incorporating traditional Chinese practices such as tai chi or acupuncture as complementary therapies for stress relief. These programs could also include community-based support groups that provide a safe space for caregivers to share their experiences and receive guidance, reducing the isolation often felt in caregiving roles. Specifically, these programs should address the unique burdens placed on spouses, helping them navigate the dual pressures of caregiving and maintaining a marital relationship, as well as supporting children who may be distant or unable to fulfill traditional roles.

This study has several limitations. The sample size was relatively small, and all participants were from Beijing, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or cultural groups within China. The study relied on self-reported data, which can introduce bias, as participants might underreport or overreport their experiences due to cultural expectations or recall bias. Furthermore, the study focused primarily on the perspectives of family caregivers, without incorporating the views of healthcare providers or the patients themselves, which could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the caregiving experience in a Chinese context.

Future research should aim to address these limitations by including a larger and more diverse sample that encompasses caregivers from various regions and cultural backgrounds within China. Longitudinal studies would provide valuable insights into how caregiving roles and experiences evolve over time, especially as societal and family structures continue to change. Additionally, future studies should incorporate the perspectives of healthcare providers and patients to create a more holistic understanding of the caregiving process.

Moreover, there is a need to explore the effectiveness of culturally tailored interventions designed to support caregivers in Beijing. These could include psychological counseling that integrates traditional Chinese medicine principles, financial assistance programs specifically targeting low-income families, and educational initiatives that equip caregivers with the skills and knowledge they need to manage their responsibilities effectively. Finally, public health policies should focus on developing formal support systems that are culturally sensitive and accessible, helping to alleviate the significant burden on family caregivers in Beijing and similar settings.

This study provides valuable insights into the roles, responsibilities, and challenges faced by family caregivers of cancer patients in Beijing. Key findings reveal that caregivers undertake a wide range of duties, including financial support, direct care, and household management, often at the expense of their own physical and emotional well-being. The impact on caregivers’ daily lives is significant, with many reporting fatigue, psychological stress, and a lack of external support. Perceptions of medical staff support were mixed, highlighting the need for improved communication and empathy from healthcare providers. The study also identified various challenges and conflicts, both institutional and societal, that exacerbate the burden on caregivers.

To improve family-centered support programs, several recommendations emerge from the study:

1. Enhance Psychological Support: Integrate psychological counseling and mental health services into oncology care settings to provide caregivers with professional support tailored to their emotional needs.

2. Financial Assistance Programs: Develop policies to subsidize medical costs and provide financial aid to alleviate the economic burden on families.

3. Caregiver Education: Implement training programs for caregivers to equip them with the necessary skills and knowledge to manage their responsibilities effectively.

4. Strengthen Communication: Train healthcare providers to improve their communication skills, ensuring they can offer compassionate and clear guidance to caregivers.

5. Promote Awareness: Increase awareness and accessibility of existing support resources, encouraging caregivers to seek and utilize available help.

6. Support Networks: Establish support groups and community resources that offer practical and emotional assistance to caregivers.

Addressing the needs of family caregivers is essential for the overall well-being of cancer patients. By focusing on both the emotional and practical challenges faced by caregivers, healthcare systems can create a more supportive environment that enhances the quality of care for patients and reduces the burden on their families. Recognizing and addressing these needs through comprehensive support programs and policies is crucial for fostering resilience and well-being among family caregivers, ultimately leading to better outcomes for all involved in the cancer care continuum.

Acknowledgement: We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to all the family caregivers who participated in this study and shared their experiences. Your insights and honesty have been invaluable to our research. We also thank the healthcare institutions in Beijing for their support in facilitating this study. Additionally, we are grateful to our colleagues and advisors for their guidance and feedback throughout the research process.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, data analysis, and writing the original draft: Wei Wang. Supervision, validation, and critical review of the manuscript, data analysis, and overseeing the writing, review, and editing process: Lan Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang T, Zhao Y. The role of psychological interventions in cancer care: a review. Cancer Med. 2020;9(2):589–600. [Google Scholar]

2. Baclig NV, Comulada WS, Ganz PA. Mental health and care utilization in survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;7(6):pkad098. [Google Scholar]

3. Hu S, Chang C, Snyder J, Deshmukh V, Newman M, Date A, et al. Mental health outcomes in a population-based cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2023;116(3):445–54. [Google Scholar]

4. Abdelhadi O. The impact of psychological distress on quality of care and access to mental health services in cancer survivors. Front Health Serv. 2023;2:1111677. doi:10.3389/frhs.2023.1111677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Bradley CJ, Kitchen S, Owsley KM. Working low income and cancer caregiving: financial and mental health impacts. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(16):2939–48. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.02537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kodipalli A, Devi S. Analysis of fuzzy-based intelligent health care application system for the diagnosis of mental health in women with ovarian cancer using computational models. Intell Deci Technol. 2023;17(2):235–48. doi:10.3233/IDT-228006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Given B, Given CW, Sherwood P. Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(2):145–55. doi:10.1016/j.suponc.2011.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lynch J, D’Alton P, Gaynor K. Evaluating the role of perceived injustice in mental health outcomes in cervical cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(8):6119–30. [Google Scholar]

9. Kim Y, Baker F, Spillers RL, Wellisch DK. Psychological adjustment of cancer caregivers with multiple roles. Psycho-Oncol. 2006;15(9):795–804. doi:10.1002/pon.1013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Najjuka SM, Iradukunda A, Kaggwa MM, Sebbowa AN, Mirembe J, Ndyamuhaki K, et al. The caring experiences of family caregivers for patients with advanced cancer in Uganda: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2023;18(10):e0293109. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0293109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA: A Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–39. doi:10.3322/caac.20081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Suresh M, Risbud R, Patel MI, Lorenz KA, Schapira L, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Clinic-based assessment and support for family caregivers of patients with cancer: results of a feasibility study. Cancer Rep. 2023;6(5):e0047. [Google Scholar]

13. Valero-Cantero I, Casals C, Espinar-Toledo M, Barón-López FJ, García-Agua Soler N, Vázquez-Sánchez MA. Effects of music on the quality of life of family caregivers of terminal cancer patients: a randomised controlled trial. Healthc. 2023;11(14):1985. doi:10.3390/healthcare11141985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Neves M, Bártolo A, Prins J, Sales C, Monteiro S. Taking care of an adolescent and young adult cancer survivor: a systematic review of the impact of cancer on family caregivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(8):5488. doi:10.3390/ijerph20085488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Li Q, Loke AY. A literature review on the mutual impact of the spousal caregiver-cancer patients dyads: ‘Communication’, ‘Reciprocal Influence’, and ‘Caregiver-Patient Interactions’. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(3):247–58. [Google Scholar]

16. Yates P. Family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: the impact of caregiving on their mental and emotional health, and quality of life. Palliat Med. 2015;29(5):412–9. [Google Scholar]

17. Tang ST, Li CY, Liao YC. Factors associated with depressive distress among Taiwanese family caregivers of cancer patients at the end of life. Palliat Med. 2007;21(3):249–57. doi:10.1177/0269216307077334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Gaugler JE, Hanna N, Linder J, Given CW, Tolbert V, Kataria R, et al. Cancer caregiving and subjective stress: a multi-site, multi-dimensional analysis. Psycho-Oncol. 2005;14(9):771–85. doi:10.1002/pon.916. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontol. 1980;20(6):649–55. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014 Sep;89(9):1245–51. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Naeem M, Ozuem W, Howell K, Ranfagni S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2023;22:1–12. doi:10.1177/16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQa 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Dec;19(6):349–57. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Hussin NAM, Sabri NSM. A qualitative exploration of the dynamics of guilt experience in family cancer caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31:4815–26. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Biggs A, Brough P, Drummond S. Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. In: The handbook of stress and health: a guide to research and practice. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley; 2017. p. 349–64. doi:10.1002/9781118993811.ch21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mehnert A, Hartung T, Friedrich M, Vehling S, Brähler E, Härter M, et al. Burden, gender, and treatment of mental health problems in cancer patients: results from the 2018 German cancer survey. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(30):162. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.36.30_SUPPL.162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Given B, Given C. The burden of cancer caregivers. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2019. doi:10.1093/MED/9780190868567.003.0002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chen C. Dependent independence: reframing aging and caregiving after China’s one-child policy. Gerontol. 2019;59(Supplement_1):3104. doi:10.1093/geroni/igz038.3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools