Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Oncosexology in côte d’Ivoire: Attitudes and Practices of Physicians Involved in the Management of Breast and Prostate Cancer

1 Department of Medicine and Medical Specialties, UFR Medical Sciences, Félix Houphouët Boigny University, Yamoussoukro, 01 BP V166 Abidjan 01, Côte d’Ivoire

2 Service De Cancerologie Du Chu De Treichville, Treichville, 01 BP V03 Abidjan 01, Côte d’Ivoire

* Corresponding Author: Kouamé Konan Yvon Kouassi. Email:

Psycho-Oncologie 2024, 18(4), 359-365. https://doi.org/10.32604/po.2024.049816

Received 19 January 2024; Accepted 26 August 2024; Issue published 04 December 2024

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the attitudes and practices of oncosexology in the management of breast and prostate cancer in Côte d’Ivoire. Methods: A cross-sectional, multicenter, descriptive and analytical survey carried out over 02 months from 1 November to 31 December 2022, among doctors involved in the management of breast and prostate cancer in Côte d’Ivoire. Results: 78 physicians on 114 participated in the study, with a participation rate of 79.5%. Only one doctor discussed the sexual risks associated with cancer with all his patients and 7.7% of doctors said they never broached questions of sexuality with their patients. The approach to sexuality was strongly associated with occupation (p = 0.002). A request for onco-sexological care was initiated by the patient and the partner respectively in 3.8% and 25.6% of cases. Only 5.1% of physicians claimed to have received training in oncosexuality. In 92.3% of cases, doctors would like to have training on this topic. Conclusion: On the questions relating to sexuality, Physicians are not addressing sexuality with their patients diagnosed with breast or prostate cancer. The lack of training in this area appears to be the main reason for this lack of communication and onco-sexological care.Keywords

Cancer is a major public health problem worldwide, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. In Côte d’Ivoire in 2020, the most common cancers in men and women were prostate cancer (4041 cases) and breast cancer (3869 cases) [1]. These cancers most often occur in young patients at the time of genital activity [2]. Over the past few years, major advances have been made in cancer treatment, resulting in higher survival and cure rates. Nowadays, patients are living longer and longer with cancer that has been treated, monitored, or cured [3]. Multimodal treatments, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies, have intensified, generating considerable physical and psychological stress for patients. Most of these treatments, introduced over the last twenty years, are likely to cause acute, chronic, or delayed toxicity, and sometimes sequelae [4]. These cancers, and even their treatment, can cause considerable physical and psychological stress, impacting on quality of life in general and sexual quality of life in particular [4].

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the United States has estimated that sexual health problems induced by cancer treatment vary from 40% to 100% depending on the type of cancer [5]. Not all cancers affect sexuality in the same way. Certain cancers, such as breast and prostate cancer, can call into question feelings of virility, reduce sexual interest, and modify or even suppress sexuality [6].

The relationships between the efficacy of oncology treatments and their toxicity are complex, making it essential to integrate quality of life as an essential component in cancer management [4]. The impact of cancer on sexual quality of life is referred to as oncosexuality, and oncosexology is the medical specialty that deals with it [7]. Oncosexology, a new training and care option in oncology, aims to reconcile carcinological and quality of life objectives. Indeed, sexual health is part of oncology care just as sex life is part of well-being for many subjects/couples [8]. However, despite the high frequency of sexual health problems, particularly healthcare professionals [5,9] rarely address these in oncology visits. The degree to which oncosexology is considered varies from one oncology healthcare professional to another. Indeed, some studies aimed at assessing the levels of communication between healthcare professionals and patients about their sexual problems; show that these were rarely mentioned [10]. On the other hand, other authors such as Almont refer to the frequent use of oncosexology by healthcare professionals [11]. To date, in Côte d’Ivoire, no study has been conducted among healthcare professionals to assess their practice of oncosexology.

The aim of our study was therefore to evaluate the attitudes and practices of oncosexology by doctors involved in the management of breast and prostate cancers in Côte d’Ivoire.

This multicenter descriptive and analytical cross-sectional survey was conducted for 2 months, from 1 November to 31 December 2022. The study was conducted in public and private hospitals in the two main cities of Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan and Bouaké.

Medical staff involved in the management of breast and prostate cancers and meeting the following represented the study population.

Inclusion criteria: being a doctor involved in the management of breast and prostate cancers and registered on the virtual exchange platform of the uro-oncological and gynecological-mammary tumor boards of the Treichville University Hospital in Abidjan. This is a virtual exchange platform bringing together different specialists from Abidjan and Bouaké to discuss oncology cases.

Radiologists, pathologists, and doctors who refused to take part in the survey were not included in the study.

The development of the questionnaire took place in 4 successive stages: the creation of a paper version of the questionnaire which was modified twice by certain members of the team; the submission of the first version of the questionnaire to the head of the department; a pre-test carried out with 5 doctors to assess the understanding and relevance of the survey and finally the creation of an electronic version of the latest version of the questionnaire.

Based on a closed questionnaire created on “google Forms”, a link to fill in the questionnaire was generated and sent to doctors via two channels: a virtual messaging platform for the Treichville University Hospital’s oncology tumor boards and via email to various doctors. This was a self-administered questionnaire in electronic format. The link was available for 2 months (November and December 2022) on the Treichville University Hospital tumor board platform. Follow-up messages were sent twice to optimize participation (at one month and two days before the end of the inclusion period). Each participant could complete the questionnaire only once. To avoid missing data, each question required a response for the questionnaire to be validated. The data collected noted, the socio-professional characteristics of doctors (age, gender, profession, place of practice, number of years of practice, sector of activity), their attitudes and clinical practices concerning sexual dysfunctions (sexual disorders investigated, participation in management), and inter-professional relations in the context of onco-sexology (professionals involved and their role).

All the data were analyzed using Epi info 7.2.5 software. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 test or Fisher test. The significance threshold for observed differences was set at 5%.

The design and implementation of our study considered the ethical and legal requirements for medical research involving human subjects’ confidentiality (anonymity), informed consent, information, storage, and destruction of data. The study was approved by the Service De Cancerologie Du Chu De Treichville Ethics Committee Verbal consent was obtained from each doctor.

The gynecological-mammary and urological tumor board platform comprises 114 doctors, 98 of whom met our inclusion criteria. During our study period, 78 doctors completed the questionnaire, representing a 79.5% participation rate.

Socio-demographic and professional characteristics

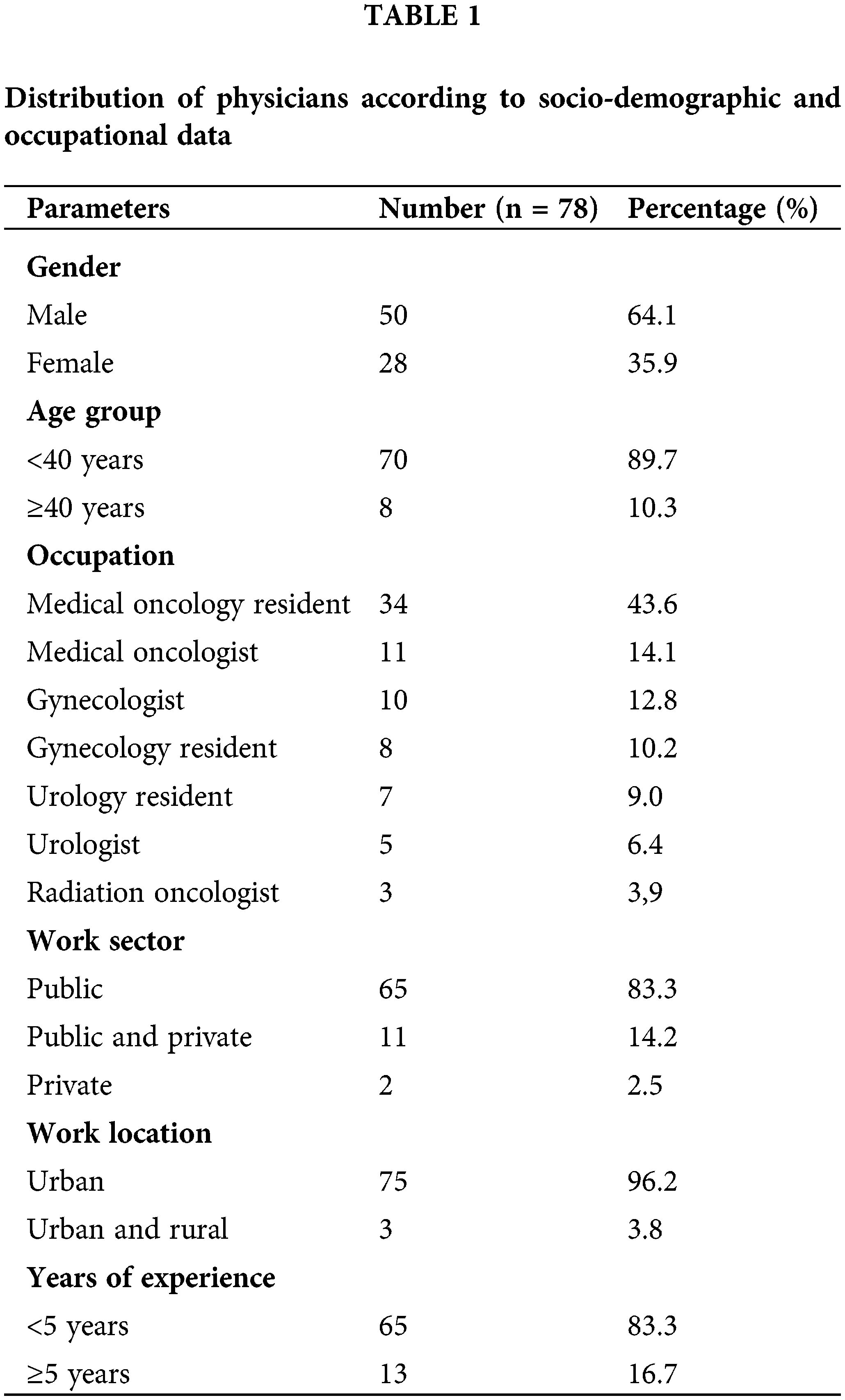

The majority of doctors were male (64.1%); those specializing in medical oncology were the most represented (43.6%), followed by medical oncologists (14.1%) and gynecologists (12.8%); most doctors worked in the public sector (83.3%), of which 83.3% had less than five years of clinical experience (Table 1).

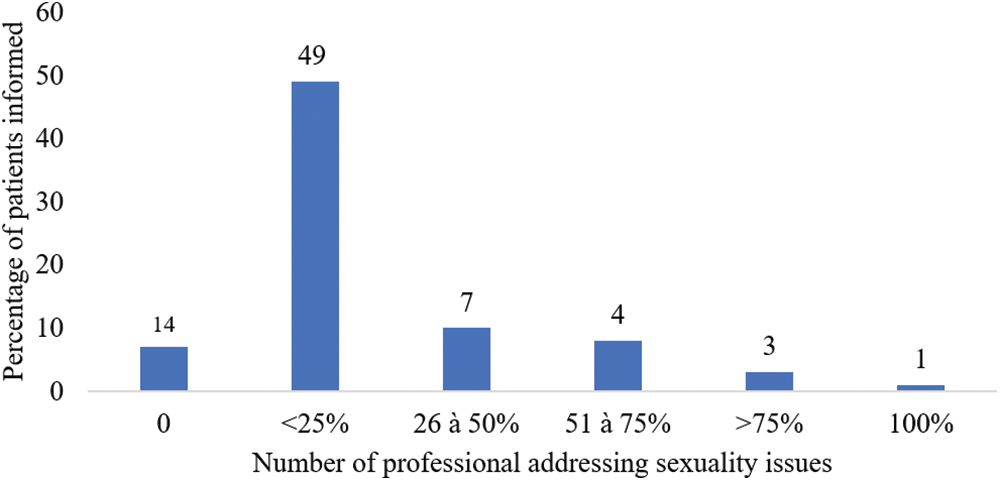

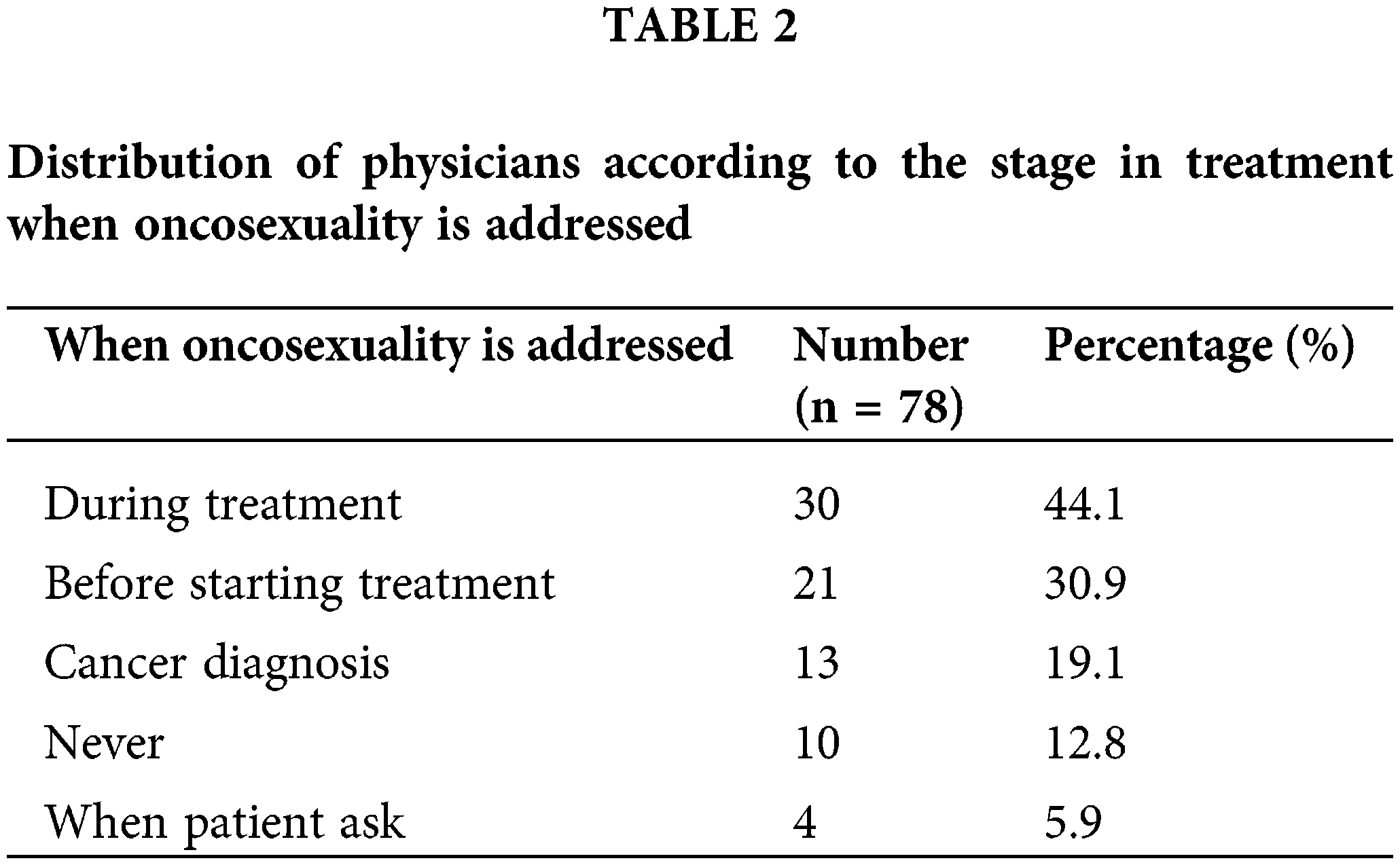

More than half of the medical professionals questioned (71.8%) considered that they consulted more than one patient per week with a treatment potentially harmful to their sexuality. In our study population, 7.7% of doctors said that they never discussed sexual issues with their patients: Only one doctor (1.3%) discussed the sexual risks associated with cancer with all his patients (Fig. 1); in 44.1% of cases, sexuality was discussed during treatment; in 30.9% of cases before treatment, and in 19.1% of cases during the initial consultation; in 5.9% of cases, sexuality was discussed at the patient’s request (Table 2).

Figure 1: Distribution of physicians according to how sexuality is addressed.

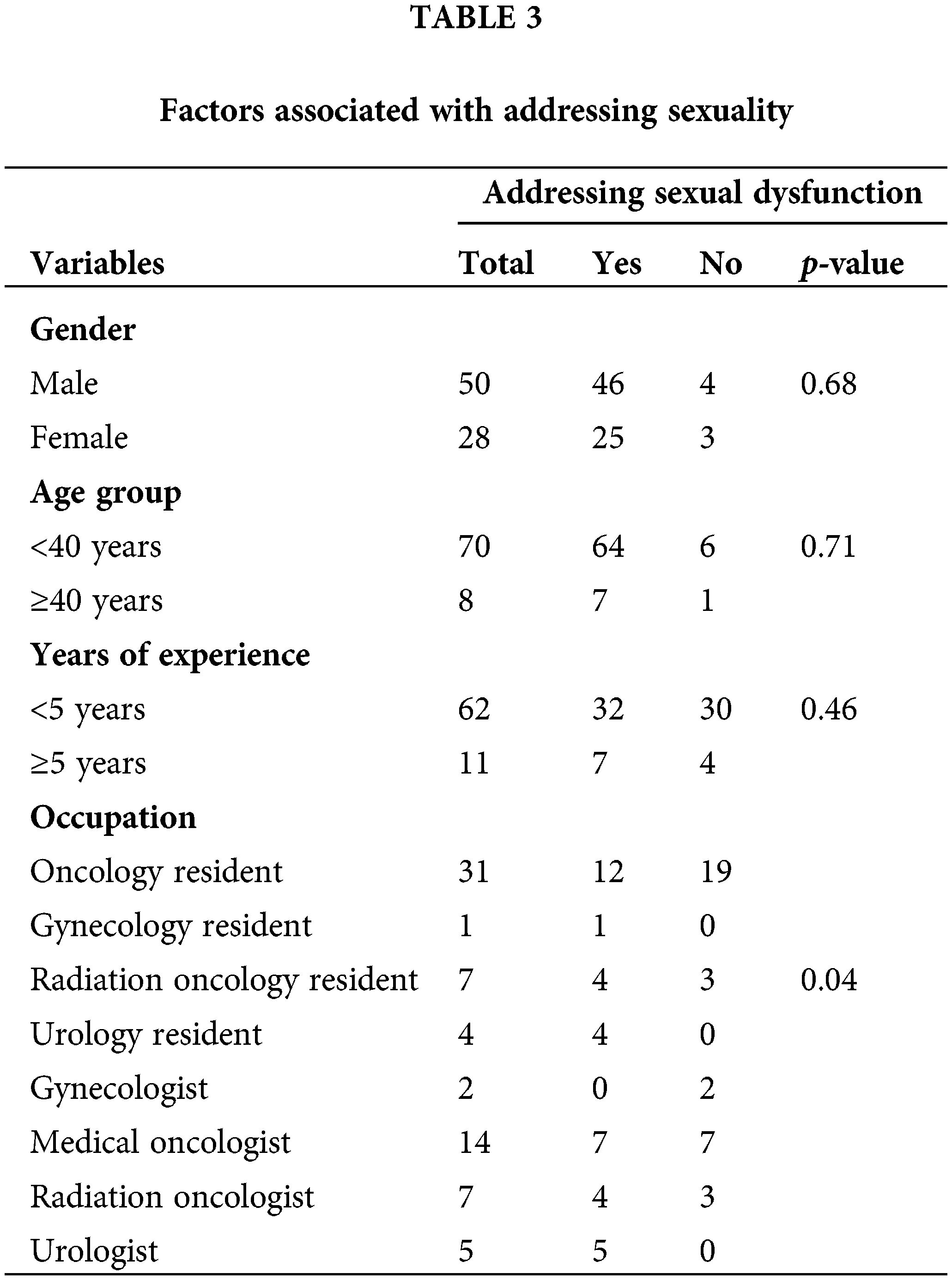

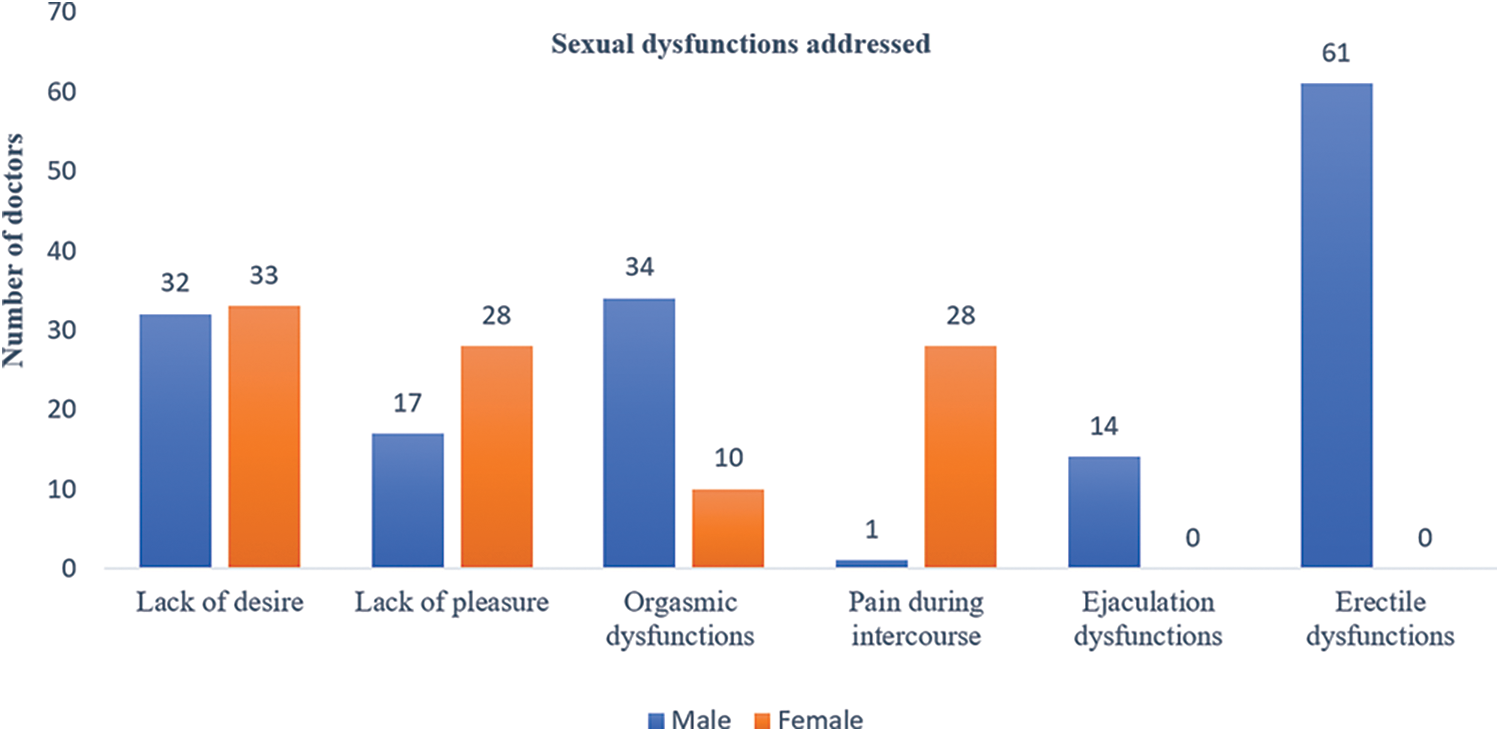

Addressing sexuality was associated with medical specialty (p = 0.04) and not with age, gender, or number of years in practice (Table 3). In men, the sexual problems most frequently sought by the doctors surveyed during consultations were erectile dysfunction and lack of desire. In women, it was mainly desiring disorders and dyspareunia (Fig. 2). More than half of the professionals questioned (56.4%) felt that their clinical schedule was not an obstacle to discussing sexuality after cancer.

Figure 2: Distribution of physicians according to the type of sexual dysfunction being addressed.

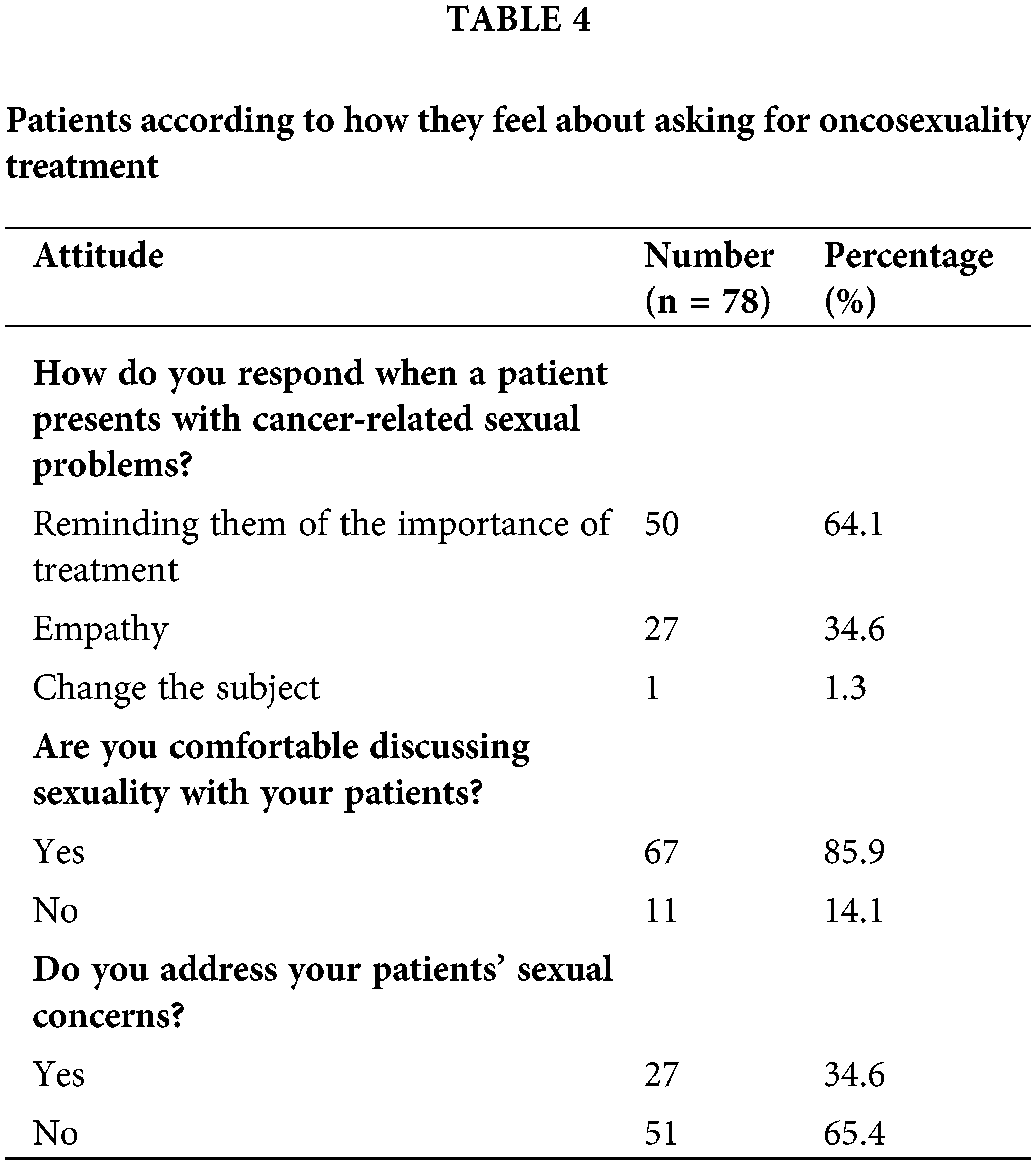

When asked about their attitude to a request for sexological management from their patients, 64.1% of doctors replied that they emphasized the importance of the treatment and the prognosis. In 34.6% of cases, they showed empathy, and in 1.3% of cases changed the subject (Table 4). In 5.9% of cases, sexuality was discussed at the patient’s request. In 25.6% of cases, the partners-initiated treatment. Less than half the medical professionals said they were involved in managing the sexual problems of patients and their partners. In 14.1% of cases, doctors felt uncomfortable discussing sexuality with their patients. However, 94.9% of which felt that all patients undergoing treatment affecting their sexuality should have access to sexological rehabilitation support care.

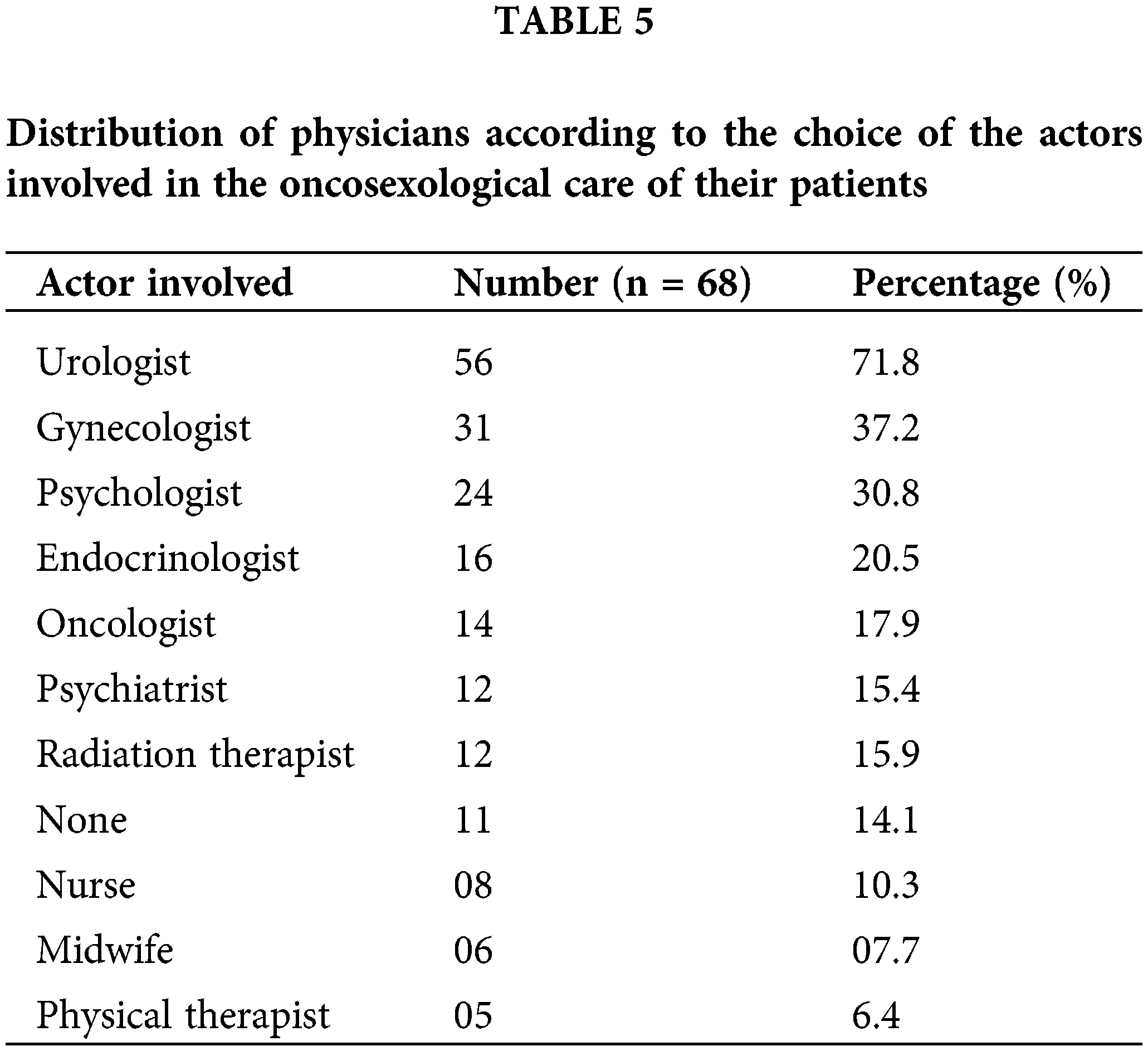

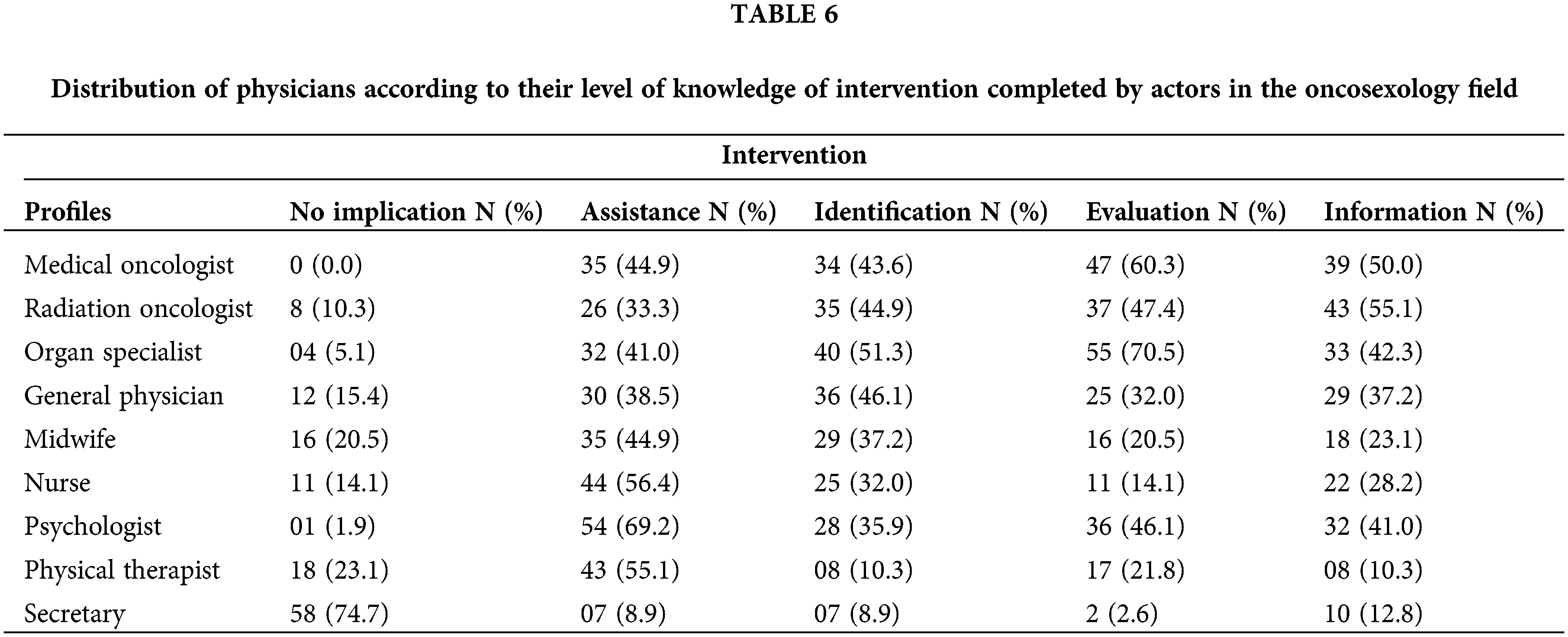

Doctors taking part in the study were in contact with urologists (64.1%), gynecologists (37.2%), psychologists (30.8%), and medical oncologists (17.9%) for the management of sexual dysfunctions (Table 5). More than two-thirds of respondents (82%) said cancer patients had difficulty finding suitable sexological support care. However, they were aware of the level of intervention of each oncosexology player (Table 6).

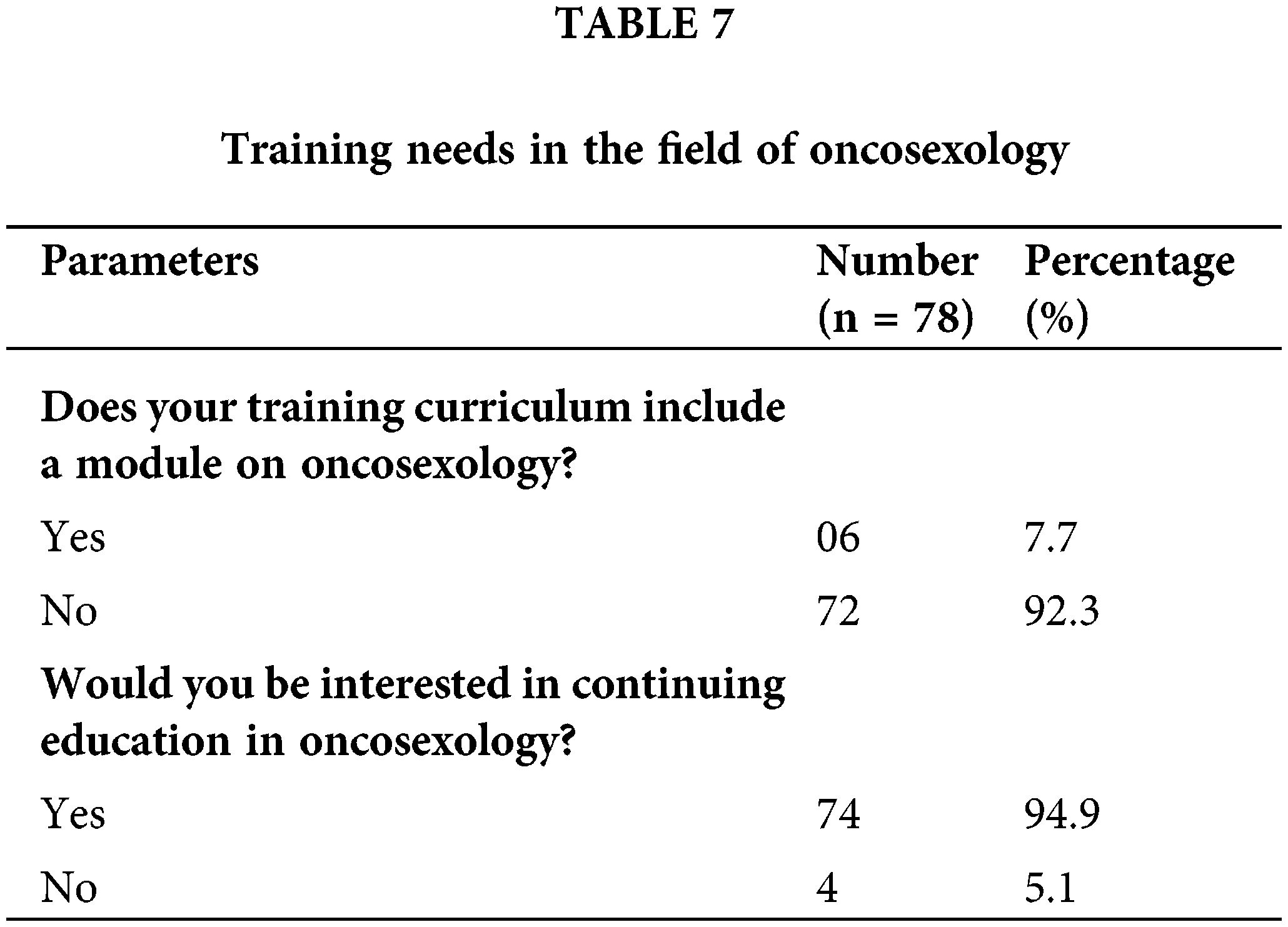

Only 5.1% of doctors claimed to have received training in oncosexology. In 92.3% of cases, doctors showed interest in training in this area (Table 7).

This cross-sectional survey identified the level of knowledge, attitudes and practices of oncosexology among physicians in the management of breast and prostate cancers in Côte d’Ivoire.

Sociodemographic and professional characteristics

The participation rate in our study was 79.5%. Our result is higher than that of Langlade, who found a participation rate of 43.6% [12] in his study on the approach to sexuality at the French Assisted Reproduction Centers. This difference could be because we had a reminder system in place.

Doctors specializing in medical oncology were the most represented (43.6%). For the last ten years, the University of Felix Houphouët-Boigny in Abidjan has been one of the few universities in the French-speaking countries of sub-Saharan Africa to offer a specialization in oncology. This specialty brings together doctors from French-speaking Africa. To date, it has trained about thirty doctors. They are involved in the treatment of cancer patients from the very first year of their training. The fact that our population is predominantly male could be linked to the low level of education among women in sub-Saharan Africa. According to UNESCO, inequalities between the sexes in schooling will still be pronounced in countries south of the Sahara in the year 2020 [13].

Only one doctor always discussed sexuality with all his patients in our study population. Our results are similar to those of Kotronoulas and Letourneau, who found that questions related to the provision of sexual health care were rarely asked [14,15]. In contrast, Langlade and Almont had sexuality discussions with all patients in 56% and 66.7% of cases, respectively [14,16]. The fact that their studies were conducted among physicians who were already aware of oncosexology may explain this difference. Healthcare professionals communicate more with patients when they are aware of this topic [11,14].

Dealing with sexuality was associated with the medical specialty. Organ specialists (urologists and gynecologists) and radiation oncologists were more likely to discuss sexuality with their patients. These physicians are most likely to treat breast cancer and prostate cancer at a localized stage, where the treatment is essentially locoregional. These locoregional treatments have a direct impact on sexuality, which systematically requires a discussion on the topic [11].

In response to a question about their attitude to a patient’s request for sexological treatment, 64.1% of physicians emphasized the importance of the treatment and its prognosis [16]. In 34.6% of cases, they showed empathy. However, there are several obstacles to talking about sexuality: First, there is a significant lack of awareness and training among healthcare professionals; second, patients have difficulty discussing this intimate issue [17]. Cultural factors may have a significant impact on the way sexuality is discussed, as suggested by some of the data collected in the international literature to date [17].

In our study, the majority of physicians (35.6%) who discussed the topic did so during treatment. In our context, cancer is usually diagnosed at a late stage [4]. This may explain why sexuality-related problems tend to be overlooked, even by the patient [14,18]. In 5.1% of cases, the patient asked to be treated. This lack of questioning by patients does not necessarily mean acceptance. Cancer has an impact not only on the patient but also on the partner. For this reason, each partner must be informed early on about possible effects on the couple’s sexual health and available solutions [11].

Physicians reported that their patients had difficulty finding appropriate oncosexological care in 82% of cases. This corroborates the results of Almont, who noted that 83.3% of physicians had problems finding appropriate care related to oncosexuality [19]. Training specialists in oncosexuality could remedy this.

Training in the field of oncosexology

This need for training exists. In 94.9% of cases, an oncosexology course was not taught in their residency program. 92.3% of the physicians surveyed were interested in training in oncosexology. This high demand for training was also found by Almont et al. [11]. In his study, 75.8% of physicians expressed a need for training in oncosexology. Training in oncology would improve patient management, with a positive impact on quality of life [20].

Our study has certain limitations that need to be clarified; although our sample was representative, it was also small and heterogeneous (different levels of education, unequal distribution between the sexes). As with all online surveys, the lack of contact with the interviewer could have led to misunderstandings of some questions. This could have resulted in information bias. Nevertheless, our results give rise to the following comments.

At the end of our study, on the consideration of oncosexuality in the treatment of breast and prostate cancer in Côte d’Ivoire, we found that physicians rarely addressed questions related to sexuality. The specialization field of the medical professionals in question influenced this approach to sexuality. The main reason for this lack of communication and onco-sexological management seems to be the lack of training in this field. Hence the need for the implementation of information and training policies for health professionals responsible for the treatment of breast and prostate cancer. Also, a longitudinal study should be undertaken to observe changes in oncosexology practices over time after the training interventions, as well as the impact of cultural factors.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Kouamé Konan Yvon Kouassi designed the study; Fleur Audrey Sessegnon, Marie Sandrine Koffi, Akissi Marie Barbara Yvonne Nogbou and Petiori Gningayou Laurence épouse Kamara Touré collected the data; N’guessan Manlan Prosper Mebiala and Yenahaban Lazare Toure prepared the tables and figures; Bitti Adde Odo and Ouowene Prisca Marina Sougue wrote the manuscript; Moctar Toure, Asmaho Akissi Danielle Andree Traore-Kouassi, Sherif Traore revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed in this work are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The design and implementation of our study considered the ethical and legal requirements for medical research involving human subjects’ confidentiality (anonymity), informed consent, information, storage, and destruction of data. The study was approved by the Service De Cancerologie Du Chu De Treichville Ethics Committee Verbal consent was obtained from each doctor.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. PNLCa Cote d’Ivoire. Profil épidémiologique du cancer en Côte d’Ivoire; 2020. Disponible sur : https://www.pnlca.org/copy-of-cancer-en-cote-d-voire. [Accessed 2023]. [Google Scholar]

3. Nuytten M, Faugeras L, D’Hondt L. Cancer et sexualité. Louvain Med. 2018;137(7):486–91. [Google Scholar]

4. Cella DF. Le concept de qualité de vie : les soins palliatifs et la qualité de vie. Recherche en soins infirmiers. 2007;88(1):25–31. [Google Scholar]

5. McLeod DL, Hamilton J. Parler de la sexualité dans le contexte du cancer : qui le fait en premier ? Can Oncol Nurs J. 2013;23(3):202–7. doi:10.5737/1181912x233202207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wisard M. Cancer et sexualité masculine. Rev Med Suisse. 2008 déc 3;182(44):2618–23. [Google Scholar]

7. Quinn GP, Gonçalves V, Sehovic I, Bowman ML, Reed DR. Quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;17:19–51. [Google Scholar]

8. Bondil P, Habold D, Damiano T, Champsavoir P. Le parcours personnalisé de soins en oncosexologie : une nouvelle offre de soins au service des soignés et des soignants. Bulletin du Cancer. 2012 avr 1;99(4):499–507. [Google Scholar]

9. Santos DB, Vieira EM. Scripts de la sexualité dans le contexte du cancer du sein. Sexologies. 2015;24(2):51–5. doi:10.1016/j.sexol.2013.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Stacy TL, Hanna S, Judith P, Shirley RB. Communication about sexuality and intimacy in couples affected by lung cancer and their clinical-care providers. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):179–85. doi:10.1002/pon.1787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Almont T, Farsi F, Krakowski I, El Osta R, Bondil P, Huyghe E. Sexual health in cancer: the results of a survey exploring practices, attitudes, knowledge, communication, and professional interactions in oncology healthcare providers. Support Care Cancer. 2018 Aug;27(3):887–94. doi:10.1007/s00520-018-4376-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Langlade P, Martin C, Robin G, Catteau-Jonard S. Abord de la sexualité et des dysfonctions sexuelles par les médecins de la reproduction en France. Sexologies. 2020;29(3):115–20. doi:10.1016/j.sexol.2020.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ayanore MA, Pavlova M, Groot W. Unmet reproductive health needs among women in some West African countries: a systematic review of outcome measures and determinants. Reprod Health. 2015;13(5):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12978-015-0104-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kotronoulas G, Papadopoulou C, Patiraki E. Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding provision of sexual health care in patients with cancer: critical review of the evidence. Support Care Cancer. 2009 May;17(5):479–501. doi:10.1007/s00520-008-0563-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Letourneau JM, Ebbel EE, Katz PP, Katz A, Ai WZ, Chien AJ, et al. Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer. 2012 Mar;118(6):1710–7. doi:10.1002/cncr.26459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Rittenberg CN, Johnson JL, Kuncio GM. An oral history of MASCC, its origin and development from MASCC’s beginnings to 2009. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(6):775–84. doi:10.1007/s00520-010-0830-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lapôtre-Ledoux B, Remontet L, Uhry Z, Dantony E, Grosclaude P, Molinié F, et al. Incidence des principaux cancers en france métropolitaine en 2023 et tendances depuis 1990. Bull épidémio Hebdo. 2023;12–13:188–204. [Google Scholar]

18. Almont T, Delannes M, Ducassou A, Corman A, Bondil P, Moyal E, et al. Sexual quality of life and needs for sexual care of cancer patients admitted for radiotherapy: a 3-month cross-sectional study. J Sex Med. 2017;14(4):566–76. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.02.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Albaugh JA, Sufrin N, Lapin BR, Petkewicz J, Tenfelde S. Life after prostate cancer treatment: a mixed methods study of the experiences of men with sexual dysfunction and their partners. BMC Urol. 2017;17(1):45. doi:10.1186/s12894-017-0231-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Krouwel EM, Nicolai MP, van der Wielen GJ, Putter H, Krol AD, Pelger RC, et al. Sexual concerns after (pelvic) radiotherapy: is there any role for the radiation oncologist? J Sex Med. 2015;12(9):1927–39. doi:10.1111/jsm.12969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools