Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Level of Psychosocial Skills of Nurses Caring for Cancer Patients and Affecting Factors: Results of a Multicenter Study

1 Department of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal University, Bolu, 14030, Türkiye

2 Department of Psychiatric Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Istanbul Bilgi University, İstanbul, 34440, Türkiye

3 Department of Psychiatric Nursing, Zübeyde Hanım Faculty of Health Sciences, Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University, Niğde, 51200, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Perihan Güner. Email:

Psycho-Oncologie 2024, 18(3), 223-231. https://doi.org/10.32604/po.2023.045294

Received 23 August 2023; Accepted 25 December 2023; Issue published 12 September 2024

Abstract

Caring for cancer patients requires both technical and psychosocial nursing skills. The aim of this study was to determine the psychosocial care skill levels of nurses and affecting factors. This multicenter, cross-sectional study was conducted with 1,189 nurses providing direct care to adult cancer patients in 32 hospitals in 12 geographical regions of Turkey. A questionnaire, the Psychosocial Skills Form, and the Professional Quality of Life Scale were used to collect the data. Nurses’ psychosocial skill level was in the range of 2.72 ± 0.98 and 2.47 ± 0.89 out of four points. Communication skills such as empathic response, active listening, and the ability to provide information were found to be at a higher level than skills such as the activation of social support systems, therapeutic touch, and development of coping methods. Approximately 40% of nurses had received psychosocial care training, and 87% were interested in receiving additional psychosocial training. Gender, educational status, previous training in psychosocial care, and work experience with cancer patients were shown to affect psychosocial skill levels. There was a positive relationship between the level of psychosocial skills and the level of compassion satisfaction, and a negative relationship between the level of psychosocial skills and the level of burnout and compassion fatigue (p < 0.05). Nurses perceive themselves as having a medium to high level of psychosocial skills yet desire additional training. The results of this study may contribute to the development of training programs according to the needs of nurses who care for cancer patients.Keywords

Psychological distress [1,2] and unmet needs in psychosocial support, emotional support, and information [3,4] are common in cancer patients. Psychosocial symptoms and unmet needs are associated with lower quality of life and decreased general well-being [5], leading to a vicious circle. Therefore, there is a gap between the needs of patients and their families and the care they receive, pointing to the importance of integrating psychosocial care into the routine care of cancer patients.

Psychosocial care is a part of holistic care that responds to individuals’ psychological and social needs [6]. It aims to help patients and their families endure the challenges of cancer and its treatment [7]. The domain of psychosocial care includes understanding and treating the social, psychological, emotional, spiritual, quality of life, and functional aspects of cancer and is applied across the cancer trajectory from prevention through bereavement [8]. In a qualitative study with cancer patients, hospital workers, and primary health professionals, Daem et al. (2019) concluded that nurses play an important role in promoting psychosocial care [7]. Providing such care is embedded in the standards of practice for oncology nurses [9]. According to nursing regulations published in Turkey, psychosocial care is within the scope of the duties and authority of nurses [10]. However, studies have shown that nurses have difficulties in eliciting patients’ concerns and providing mental and emotional support to patients and their families [11,12]. The literature has consistently determined that nurses provide practical care rather than emotional attention [13,14]. Ultimately, nurses assume the role of providing psychosocial care to cancer patients and their families, but they must have the relevant knowledge and skills to fulfill this role [15]. Providing psychosocial care may be challenging if the psychosocial skills of nurses are not adequate.

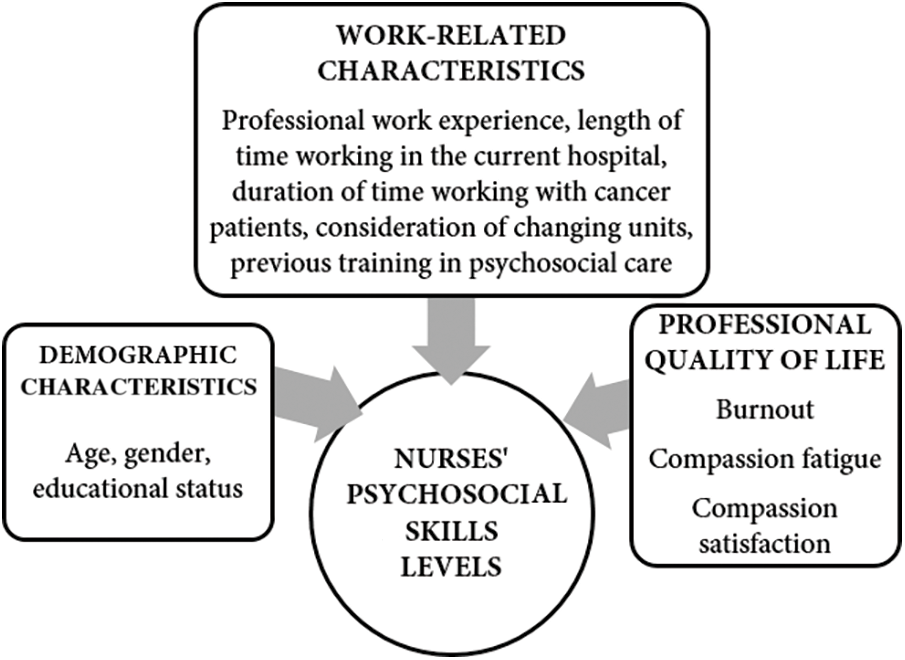

Psychosocial skills basically include offering therapeutic communication, providing information, delivering emotional support, encouraging participation in decisions, developing adaptive coping methods, screening for distress levels, and discerning when to refer to psycho-oncology/psychosocial oncology discipline [6,15,16]. The literature has long focused on communication skills, the basis of psychosocial care [11,14,17], but studies on other psychosocial nursing skill levels and affecting factors are limited. A recent study examined the perceived skill level of nurses in meeting psychosocial needs and the effect of certain variables (nurses’ gender, age, education level, specialty certification, number of oncology conferences attended, type of unit, number of years of experience in nursing or number of years on current unit, and personal experience with a close friend or relative having cancer), determining that the perceived skill scores of nurses who had a baccalaureate education, specialization certificate, and experience working in oncology, hematology, or bone marrow transplant units were higher than others. A significant positive correlation was found between perceived skill levels, years of oncology experience, and number of oncology conferences attended [18]. The aim of the current study was to determine the psychosocial care skill levels of nurses and affecting factors (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Hypothetical model of factors affecting psychosocial skills.

This study is a part of a larger Turkish project termed “Determining the Psychosocial Care-Related Needs of Oncology Nurses’’ and focused on nurses’ psychosocial caregiving skills and professional quality of life. It is a cross-sectional, nationwide survey study.

This study’s participants consisted of 1,189 registered nurses providing direct care to cancer patients in 32 hospitals located in 12 geographical regions in Turkey. Stratified sampling was used in the selection of hospitals, and convenience sampling was used in the selection of participants.

In line with Turkey’s harmonization process with the European Union, and in accordance with the Law no. 2002/4720, Turkey is divided into 12 geographical regions (Istanbul, West Marmara, Aegean, East Marmara, West Anatolia, Mediterranean, Central Anatolia, West Black Sea, East Black Sea, Northeast Anatolia, Middle East Anatolia, and Southeast Anatolia) according to the Statistical Regional Units Classification [19]. The list of university, state, and private hospitals in each region was compiled, and 32 hospitals containing the highest number of patients and nurses were selected. The study was carried out in 12 universities, 11 state, and 9 private hospitals, as there were no private hospitals in three regions and no state hospitals in one region. After contacting the nursing managers of the hospitals via telephone, it was determined that the total number of nurses working in outpatient and inpatient oncology clinics was 1,389. Calculating according to the 3% error and 99% confidence levels determined that the necessary sample size was 793. Only registered nurses providing direct care to inpatient and outpatient adult cancer patients, regardless of length of employment, were included in the study. Nurses working in fields such as education and management, who were on leave at the time of the study, and/or from whom no written informed consent was obtained were excluded from the study.

Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Koç University (Protocol number: 2016.162 IRB 3.092), and written permission from the participating institutions and written informed consent of the participants were obtained. Ethics committee and institutional permissions were obtained before the study was conducted. One nurse per hospital was assigned and trained as a study coordinator. The coordinator nurse (having previous research experience and sufficient communication skills, who could spare time for data collection, etc.) was selected by recommendation of each hospital’s nursing manager. These coordinators were trained in the inclusion-exclusion criteria of the study, informed consent, questions in the questionnaire, etc., by the project manager. Surveys were delivered to the coordinating nurse of each hospital by cargo, and eligible nurses received information about the study in face-to-face orientation meetings during each shift, delivered by the coordinating nurse. Each participant received a paper copy of the survey and voluntarily submitted an informed consent form along with the self-completed questionnaires during their shift. In an attempt to increase the response rate, participants were sent follow-up reminders every two weeks. The questionnaires, referenced anonymously, were returned to a closed box and collected by the coordinating nurse, who then sent the collected survey results to the responsible researcher by cargo. Coordinators were paid for their services, and data collection was carried out between April–August 2017.

The questionnaire, Psychosocial Skills Form, and Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL) were used to collect the data.

Demographic, professional, and other variables: The questionnaire form included questions concerning the demographic (four questions: age, gender, education, and marital status) and professional characteristics (six questions: professional work experience, type of hospital, specific unit, duration of time working in the current hospital, duration of time working with cancer patients, and type of work) of participants. The questionnaire included four questions: “Would you change your unit if you had the opportunity?”, “Have you ever received any training in psychosocial care?”, “Did you find the training you attended to be sufficient?”, and “Are you interested in receiving additional psychosocial care training?”.

Psychosocial Skills Form: This form was created based on the literature [14,16–18,20] and the experiences of the authors. The authors had an average of 18 years of psychosocial oncology experience in counseling and psychoeducation for cancer patients, consultancy, and training (courses, certificates, etc.) for nurses working in oncology. The Psychosocial Skills Form consisted of 15 items concerning the following skills: actively listening, responding with empathy, asking open-ended questions, using non-verbal communication, encouraging the expression of concerns and emotions, encouraging the expression of thoughts and perceptions, facilitating the identification of functional/alternative ideas, providing information, offering the opportunity to ask questions, ensuring participation in decisions about one’s own health, identifying and improving existing coping methods, identifying and mobilizing social support systems, using therapeutic touch, distinguishing between normal and pathological responses, and identifying and referring at-risk patients. Answers were recorded on a 4-score Likert scale. Nurses were asked to identify their competency levels regarding the listed items by choosing one of the following options: “1-Not adequate,” “2-Slightly adequate,” “3-Quite adequate,” and “4-Completely adequate.” In the present study, Cronbach’s Alpha value of the Psychosocial Skills Form was found to be 0.939.

Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL): ProQOL (Revision IV) was developed by Stamm [21], and its reliability and validity study in Turkey was carried out by Yeşil et al. [22]. It contains a total of 30 items and 3 subscales and uses a five-point Likert-type scale. Compassion satisfaction, the first subscale, refers to feelings of satisfaction and pleasure as a consequence of helping someone else in an area associated with him/herself or his/her profession; high scores obtained from this subscale indicate that the helper’s feeling of satisfaction is high. Burnout, the second subscale, measures the feeling of burnout associated with hopelessness and difficulty in coping with work problems; high scores obtained from this subscale indicate that the level of burnout is high. Compassion fatigue, the third subscale, measures manifestations of encountering stressful events; high scores from this scale indicate that the level of compassion fatigue is high. In Turkey, Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.848 for the scale, 0.819 for the compassion satisfaction subscale, 0.622 for the burnout subscale, and 0.835 for the compassion fatigue subscale [22]. In the present study, the overall Cronbach’s alpha value was found to be 0.792, while Cronbach’s alpha value of the compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue subscales were found to be 0.911, 0.727, and 0.874, respectively.

SPSS for Windows (version 24 software) (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) program was used for data analysis. For descriptive statistics, numbers, percentages, means, standard deviations (SD), or minimum and maximum scores were used according to the data type. The Skewness and Kurtosis values for the Psychosocial Skills Form and ProQOL subscales varied between −0.01 and 0.68, indicating that all data or scores were normally distributed [23]. Student’s t-test and Pearson correlation test were used to examine the factors affecting the level of each skill. The alpha level for significance in all analyses was determined to be p < 0.05.

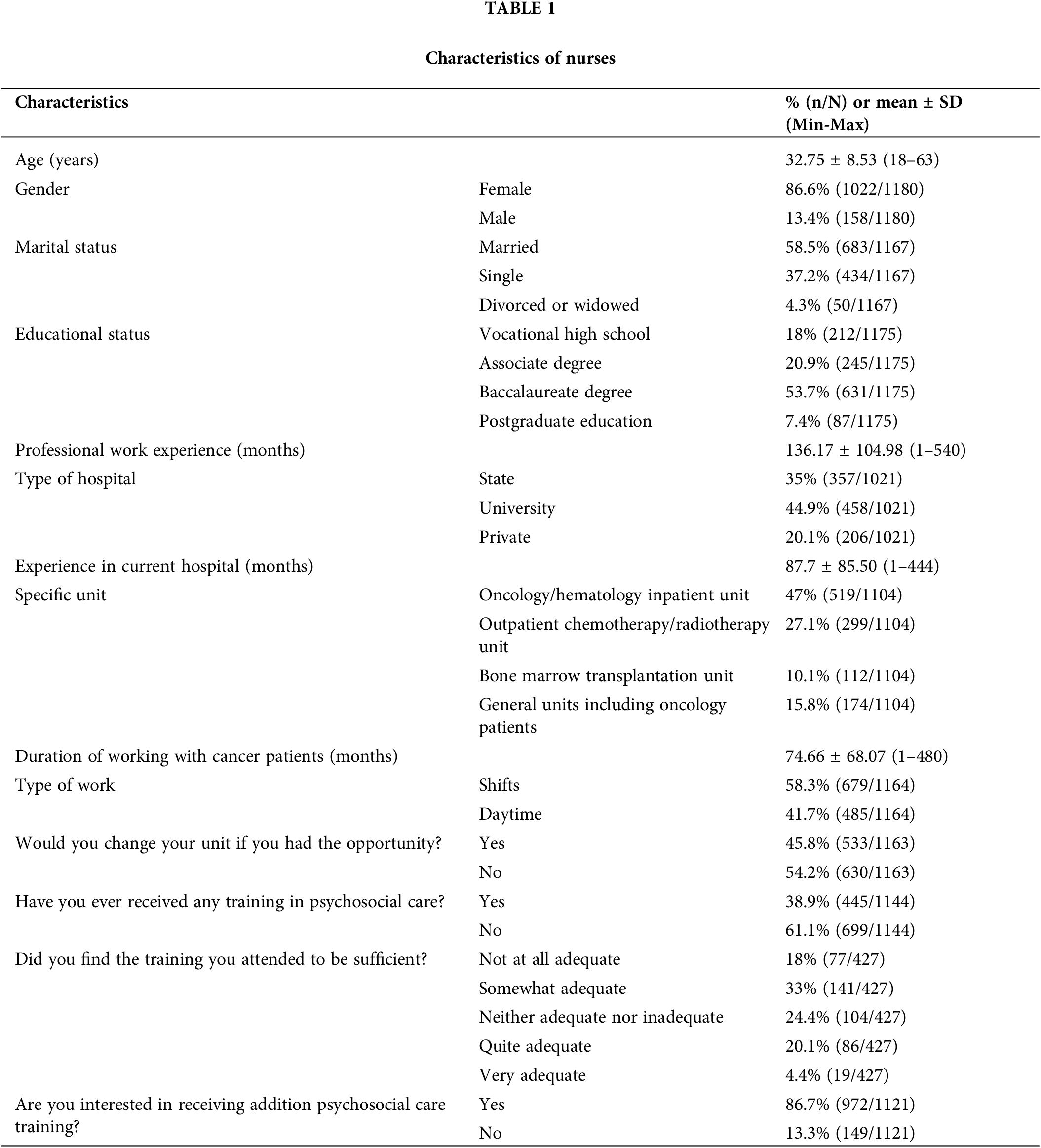

Of the entire population (N = 1389), 1,189 nurses participated in the study, equivalent to a response of 85.6%. Most of the participants were women, married, and held a baccalaureate degree. Participants had been working as a nurse for an average of 11.35 years and had been caring for cancer patients for an average of 6.22 years (Table 1).

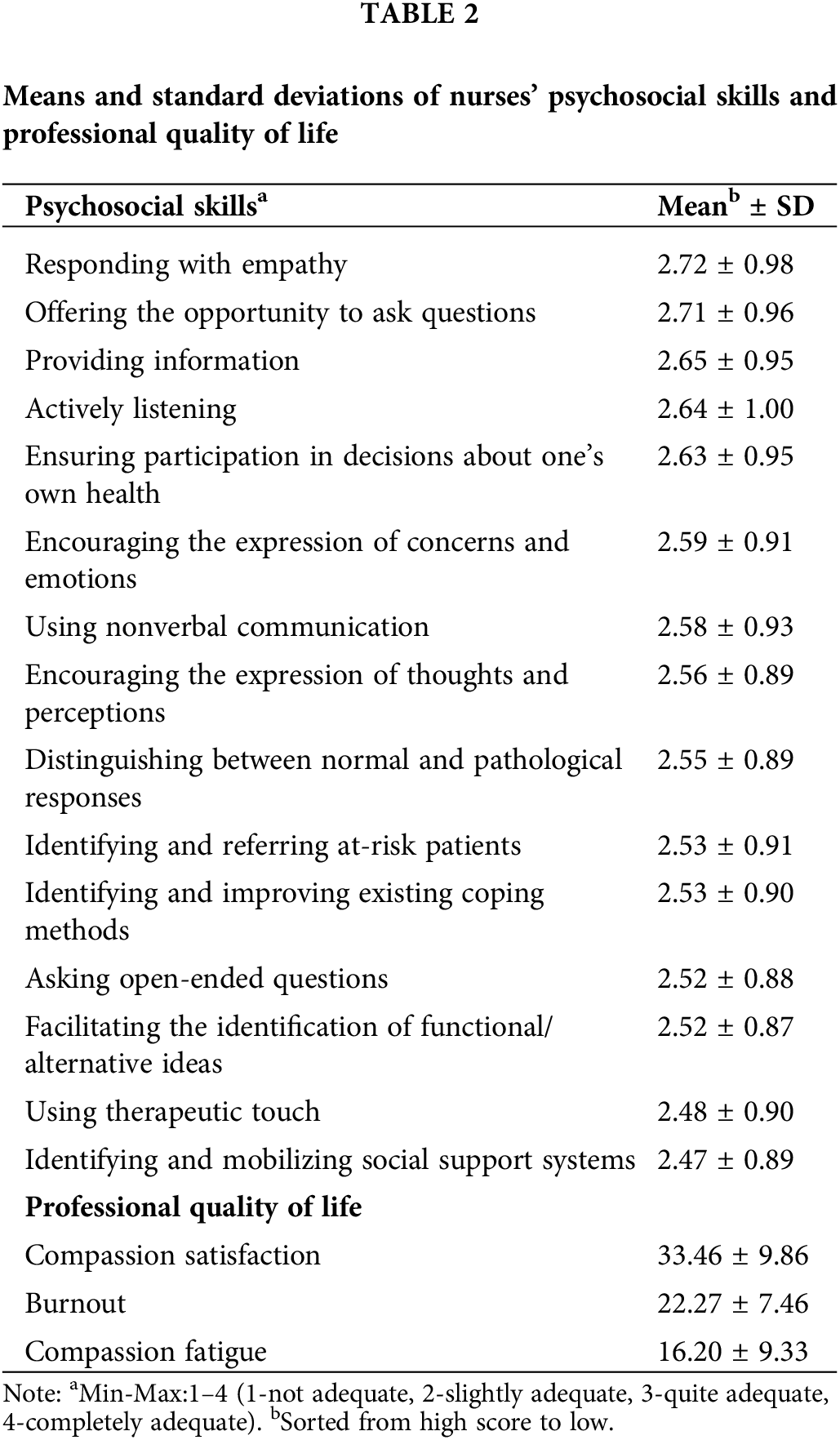

It was found that nurses evaluated their levels of psychosocial skills between 2.72 ± 0.98 and 2.47 ± 0.89. It was determined that the level of empathy skills was the highest and the level of the ability to mobilize social support was the lowest. The averages of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue were 33.46 ± 9.86, 22.27 ± 7.46, and 16.20 ± 9.33, respectively (Table 2).

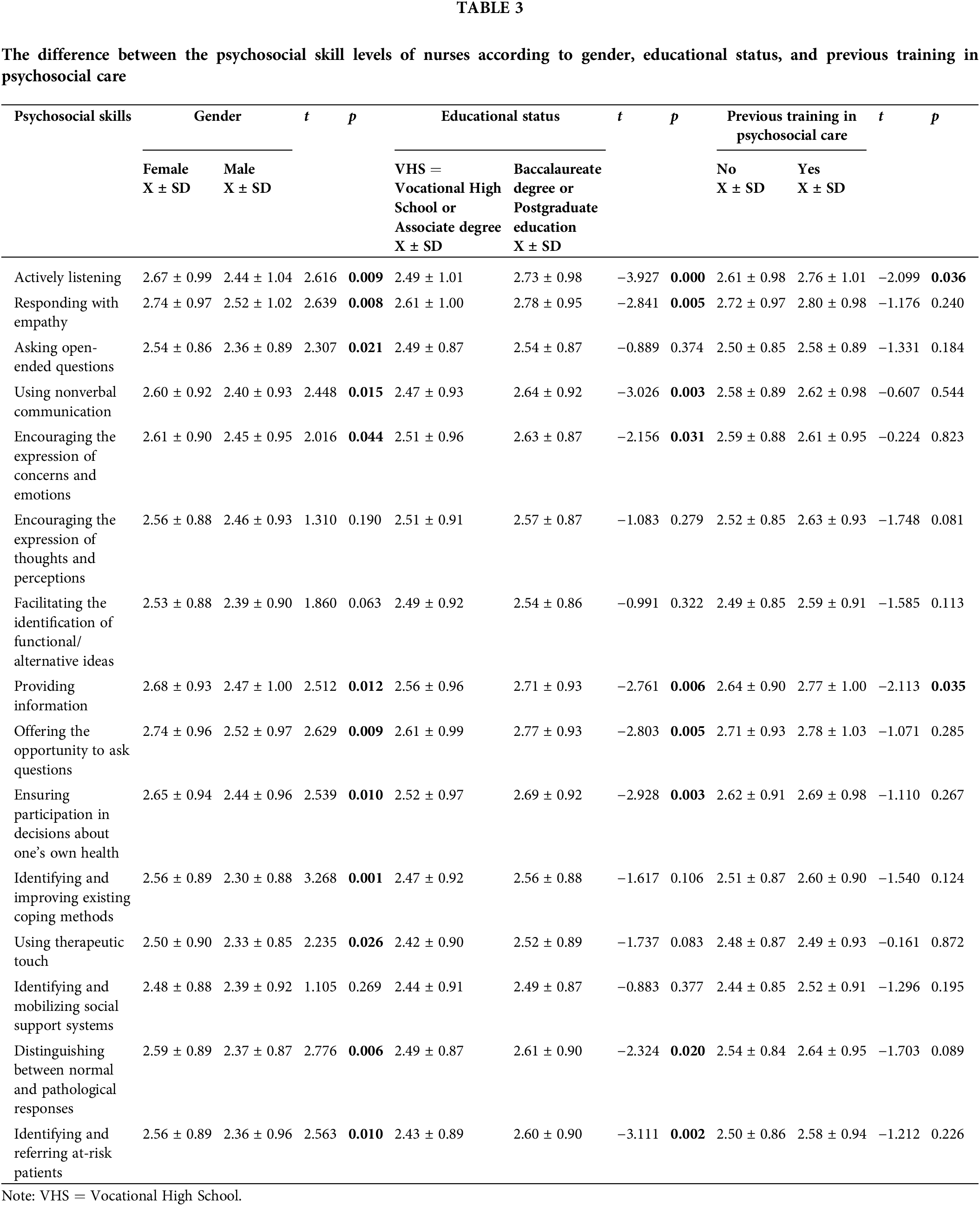

Psychosocial skills levels varied according to gender and educational status. It was found that female nurses had higher mean scores in 12 out of 15 skills when compared to male nurses, and the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). It was also determined that nurses with a baccalaureate degree and a postgraduate education had higher mean scores in nine skills than nurses with a vocational high school education and associate’s degree (p < 0.05). Those who received psychosocial care training had a higher mean score in only two skills when compared with those who did not (p < 0.05) (Table 3). There was no difference between the skill scores of those who wanted to change the unit in which they worked and those who did not (p > 0.05).

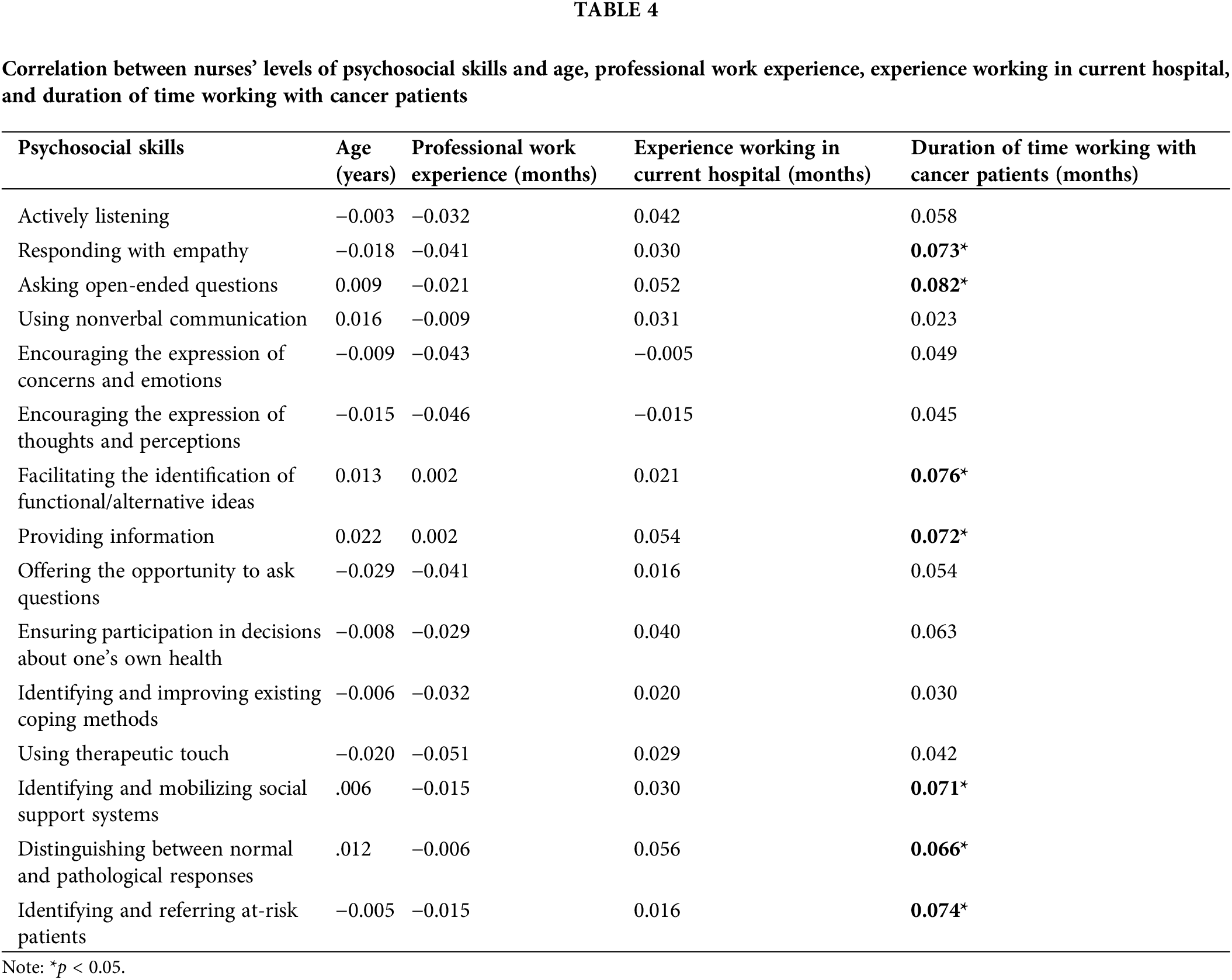

No statistically significant correlation was found between nurses’ psychosocial skill levels, age, professional work experience, and time working in the current hospital (p > 0.05). A weak positive (r = 0.07 and r = −0.08) correlation was found between the duration of time working with cancer patients and the level of seven skills (p < 0.05) (Table 4).

A weak positive (r = 0.15 to r = 0.21) correlation was found between compassion satisfaction and all psychosocial skills (p < 0.01). A weak negative correlation (r = −0.06 to r = −0.10) was found between burnout and 10 psychosocial skills (p < 0.05). A weak negative correlation (r = −0.07) was found between compassion fatigue and one psychosocial skill (p < 0.05) (Table 5).

The current study established that nurses who care for cancer patients evaluated themselves at moderate and high levels of psychosocial skills. In a study conducted in previous years, it was found to be at a moderate level [18]. This result may be due to several factors. Given the prevalence of unmet needs of cancer patients and their families [3,4], nurses’ current skills may be insufficient to meet the psychosocial needs of patients and their families. Another factor is that although nurses’ psychosocial skills may be sufficient, they may not be able to apply them due to other obstacles. Various studies on barriers to psychosocial care may confirm this interpretation [24,25]. Another possibility is that nurses may perceive their psychosocial skill levels to be higher than they actually are. As a matter of fact, as the current study and other studies have shown, nurses need additional training in order to provide psychosocial care [13,18,26,27].

Among the psychosocial skills, communication is the backbone of the relationship between health professionals and patients and their families [27]. One study found that oncology inpatient ward nurses’ confidence levels in communicating empathetically with their patients was 4.12 ± 0.64 out of five points [28]. Another well-studied issue concerning cancer patients is information delivery. It has been reported that nurses are a reliable source of information, with the delivery of such information being an important part of nurses’ role in clinical practice [29]. Such results support our study’s finding that most of the nurses had higher skill levels in showing empathy, allowing the patient/family the opportunity to ask questions, give information, and actively listen when compared to other skills. In Turkey, importance is given to the development of these skills in pre- and post-graduate nurse training. Therefore, this result is to be expected. However, it is also understood that nurses need to develop the skill of asking open-ended questions, one of the therapeutic communication techniques.

This study found that two of the skills that nurses should develop most are the activation of social support systems and therapeutic touch. In support of this finding, one study found that physicians and nurses working in oncology were able to identify but not meet patients’ supportive needs, including the mobilization of social resources [30]. Since the positive effect of social support on the cancer process has been well documented [31], it should be emphasized that nurses’ responsibility is to mobilize such support by empowering people (such as spouses or friends) who can support the patient. Considering that therapeutic touch is also beneficial, inexpensive [32], and can be improved with education [33], these skills are recommended to be a crucial part of psychosocial care training. Cultural factors may play a role in both skills. The active role of the patients’ families in the diagnosis, treatment, and care process in Turkey may have decreased nurses’ use of these skills.

This study revealed that nurses who are female, have a bachelor’s degree or higher, and have participated in psychosocial care training have higher communication and informational skills. The level of these skills improved as the length of care for cancer.

Patients increased, but surprisingly, they were not related to years of experience as a nurse. Similarly, another study reported a significant gender difference in communication skills in favor of female students [34]. Therefore, it may be important to consider the necessity of gender-specific training programs. In addition, field-specific training programs and nurse certification may be beneficial. In their study with hospice nurses, Clayton et al. found that nurses’ perceptions of their own effectiveness of communication were not related to their time working as a nurse [26]. In the current study, the ability to mobilize social support was improved only by increased experience of working with cancer patients. In addition, the skill of therapeutic touch was at a higher level in female nurses when compared to male nurses.

Our study found that there was a significant positive correlation between all nursing psychosocial skills and compassion satisfaction. Since compassion satisfaction involves the pleasure of helping others and the positive aspect of care [35], it is conceptually significant that the level of nurses’ psychosocial skills increases and contributes to increased satisfaction when providing psychosocial care to patients. Another study also found that empathic concern predicted compassion satisfaction, thereby contributing to nurses’ sense of meaning and achievement in their work [36]. A negative correlation between all psychosocial skills and compassion fatigue would be expected, as nurses’ proficiency in psychosocial skills would make it easier to manage the emotional burden of oncology patients. However, our study revealed a negative correlation only between compassion fatigue and eliciting questions from patients and their families. A study conducted with hematology nurses reported that no relationship was found between nursing competencies and compassion fatigue [37]. Our study, however, found that there was a significant negative correlation between nurses’ nine psychosocial skills and burnout. This may be due to the fact that nurses who experienced higher levels of burnout may have perceived their level of psychosocial skills to be lower. Other studies have supported that empathetic abilities are significantly reduced in professionals who experience burnout [36,38]. However, the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow for causal directions, and the inverse relationship may also be true. Chen et al. found that better nursing competence in communication/coordination and specialized clinical practice predicted less burnout [37], and a previous study reported that self-efficacy in communication skills prevents the occurrence of emotional exhaustion [39]. Our study showed that in addition to communication skills, skills such as helping patients develop coping methods and functional/alternative ideas also reduced burnout, perhaps indicating that nurses can use psychosocial care skills not only for the benefit of their patients but also for themselves.

The lack of consensus on psychosocial skills and the lack of standard measurement tools to evaluate competencies in these skills is an important limitation. Another limitation is that the data obtained by this study are based upon the reports of participants. Participants may have overestimated or underestimated their competence in psychosocial care skills. Hence, we recommend that new studies use objective measurement tools in addition to participant self-reports to confirm reliability and consistency of the findings. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow causality inferences between nurses’ psychosocial care skill levels and the factors investigated. Therefore, future studies on alternative ways to measure oncology nursing psychosocial skills, as well as observational studies aimed at evaluating such skills, are recommended. In addition, considering the barriers to psychosocial care, it may be useful to investigate other variables not examined in this study.

According to the findings of this study, which was conducted with a large sample, the psychosocial skills of nurses who care for cancer patients were at a medium or high level, however nurses desired additional training. In particular, there is a need for increased proficiency in skills such as activating social support systems for patients, using therapeutic touch, facilitating the development of alternative ideas, and supporting coping methods. Our study showed that nurses perceive themselves to be competent in communication skills such as empathy and active listening, but the method of asking open-ended questions needs to be further developed. In addition to psychosocial care training that will meet the needs of nurses, the experience of caring for cancer patients can also increase nurses’ skill levels. It was observed that special attention should be paid to increasing the level of the psychosocial skills of male nurses. Increasing nurses’ professional quality of life can positively affect their psychosocial skills and improving such skills can also increase nurses’ compassion satisfaction and reduce burnout levels.

Acknowledgement: The authors also would like to thank to all participant nurses and unit managers for their support during conduction of this study.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Vehbi Koç Foundation Nursing Fund, in Istanbul, Turkey (Grant Number 2016.2-2).

Author Contributions: Concept–P.G., N.Y.; Design–P.G., N.Y., F.İ.; Supervision–P.G., N.Y.; Resources–N.Y., F.İ.; Materials–P.G., N.Y., F.İ.; Data Collection and/or Processing–P.G., F.İ., N.Y.; Analysis and/or Interpretation–N.Y., P.G.; Literature Search–N.Y., F.İ.; Writing Manuscript–N.Y.; Critical Review–P.G., F.İ., N.Y.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used in the study can be accessed through the responsible author.

Ethics Approval: The study was initiated after approval from Koç University’s Ethics Committee (Protocol number: 2016.162 IRB 3.092) and after written permission from participating institutions and informed consent of participants were obtained.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mehnert A, Hartung TJ, Friedrich M, Vehling S, Brähler E, Härter M, et al. One in two cancer patients is significantly distressed: prevalence and indicators of distress. Psychooncol. 2018;27(1):75–82. doi:10.1002/pon.4464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yong ASJ, Cheong MWL, Hamzah E, Teoh SL. A qualitative study of lived experiences and needs of advanced cancer patients in Malaysia: gaps and steps forward. Qual Life Res. 2023;32(8):2391–402. doi:10.1007/s11136-023-03401-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Hart NH, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Yee J, Smith TJ, Koczwara B, et al. Unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a systematic scoping review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;176(9):103728. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2022.103728. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Tan JY. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):96. doi:10.1186/s12904-018-0346-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Cochrane A, Woods S, Dunne S, Gallagher P. Unmet supportive care needs associated with quality of life for people with lung cancer: a systematic review of the evidence 2007–2020. Eur J Cancer Care. 2022;31(1):e13525. doi:10.1111/ecc.13525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kocaman Yıldırım N. Oncology nurse in psychosocial care. In: Can G, editor. Oncology nursing. Istanbul: Nobel Medical Bookstores; 2019. p. 1043–56. [Google Scholar]

7. Daem M, Verbrugghe M, Schrauwen W, Leroux S, van Hecke A, Grypdonck M. How interdisciplinary teamwork contributes to psychosocial cancer support. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(3):E11–20. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Turnbull Macdonald GC, Baldassarre F, Brown P, Hatton-Bauer J, Li M, Green E, et al. Psychosocial care for cancer: a framework to guide practice, and actionable recommendations for Ontario. Curr Oncol. 2012;19(4):209–16. doi:10.3747/co.19.981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Oncology Nursing Society. In: Lubejko BG, Wilson BJ, editors. ONS scope and standards of practice. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society; 2019. [Google Scholar]

10. Regulation Amending the Nursing Regulation. Official gazette date of publication 19.04.2011 and no: 27910. 2011. Available from: http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2011/04/20110419-5.htm [Accessed 2018]. [Google Scholar]

11. Wittenberg E, Reb A, Kanter E. Communicating with patients and families around difficult topics in cancer care using the COMFORT communication curriculum. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34(3):264–73. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2018.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Haavisto E, Soikkeli-Jalonen A, Tonteri M, Hupli M. Nurses’ required end-of-life care competence in health centres inpatient ward—a qualitative descriptive study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;35(2):577–85. doi:10.1111/scs.12874. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Güner P, Hiçdurmaz D, Kocaman Yıldırım N, İnci F. Psychosocial care from the perspective of nurses working in oncology: a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;34(1):68–75. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2018.03.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Tay LH, Hegney DG, DNurs EA. A systematic review on the factors affecting effective communication between registered nurses and oncology adult patients in an inpatient setting. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2010;8(22):869–916. doi:10.11124/jbisrir-2010-149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Uwayezu MG, Nikuze B, Maree JE, Buswell L, Fitch MI. Competencies for nurses regarding psychosocial care of patients with cancer in Africa: an imperative for action. JCO Glob Oncol. 2022;8(8):e2100240. doi:10.1200/GO.21.00240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Tunmore R. The consultation liaison nurse. Nursing. 1990;4(3):31–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Moore PM, Rivera S, Bravo-Soto GA, Olivares C, Lawrie TA. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7(7):CD003751. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Frost MH, Brueggen C, Mangan M. Intervening with the psychosocial needs of patients and families: perceived importance and skill level. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20(5):350–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

19. Taş B. Adaptation process to The European Union for Turkey’s new region concept: The nomenclature of territorial units for statistics (NUTS). J Soc Sci. 2006;8(2):186–98. [Google Scholar]

20. National Cancer Action Team, National Cancer Programme. The manual for cancer services: psychological support measures, version 1.0. London: National Cancer Programme; 2011. [Google Scholar]

21. Stamm BH. The ProQOL manual. Sidran Press. Available from: http://compassionfatigue.org/pages/ProQOLManualOct05.pdf [Accessed 2005]. [Google Scholar]

22. Yeşil A, Ergün Ü, Amasyalı C, Er F, Olgun NN, Aker AT. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the professional quality of life scale. Arch Neuropsychiatr. 2010;47:111–7. [Google Scholar]

23. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2013. [Google Scholar]

24. Chen CS, Chan SW, Chan MF, Yap SF, Wang W, Kowitlawakul Y. Nurses’ perceptions of psychosocial care and barriers to its provision: a qualitative study. J Nurs Res. 2017;25(6):411–8. doi:10.1097/JNR.0000000000000185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Chan EA, Tsang PL, Ching SSY, Wong FY, Lam W. Nurses’ perspectives on their communication with patients in busy oncology wards: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0224178. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Clayton MF, Iacob E, Reblin M, Ellington L. Hospice nurse identification of comfortable and difficult discussion topics: associations among self-perceived communication effectiveness, nursing stress, life events, and burnout. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(10):1793–1801. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Solera-Gómez S, Benedito-Monleón A, LLinares-Insa LI, Sancho-Cantus D, Navarro-Illana E. Educational needs in oncology nursing: a scoping review. Healthcare. 2022;10(12):2494. doi:10.3390/healthcare10122494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Banerjee SC, Manna R, Coyle N, Shen MJ, Pehrson C, Zaider T, et al. Oncology nurses’ communication challenges with patients and families: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;16(1):193–201. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2015.07.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Tariman JD, Szubski KL. The evolving role of the nurse during the cancer treatment decision-making process: a literature review. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(5):548–56. doi:10.1188/15.CJON.548-556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Hong J, Song Y, Liu J, Wang W, Wang W. Perception and fulfillment of cancer patients’ nursing professional social support needs: from the health care personnel point of view. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):1049–58. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-2062-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Bottaro R, Craparo G, Faraci P. What is the direction of the association between social support and coping in cancer patients? a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2023;28(6):524–40. doi:10.1177/13591053221131180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Tabatabaee A, Tafreshi MZ, Rassouli M, Aledavood SA, AlaviMajd H, Farahmand SK. Effect of therapeutic touch in patients with cancer: a literature review. Med Arch. 2016;70(2):142–7. doi:10.5455/medarh.2016.70.142-147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Vanaki Z, Matourypour P, Gholami R, Zare Z, Mehrzad V, Dehghan M. Therapeutic touch for nausea in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: composing a treatment. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;22:64–8. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Graf J, Smolka R, Simoes E, Zipfel S, Junne F, Holderried F, et al. Communication skills of medical students during the OSCE: gender-specific differences in a longitudinal trend study. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):75. doi:10.1186/s12909-017-0913-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Algamdi M. Prevalence of oncology nurses’ compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Open. 2022;9(1):44–56. doi:10.1002/nop2.1070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J. The role of psychological factors in oncology nurses’ burnout and compassion fatigue symptoms. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;28(3):114–21. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2017.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Chen F, Leng Y, Li J, Zheng Y. Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in haematology cancer nurses: a cross-sectional survey. Nurs Open. 2022;9(4):2159–70. doi:10.1002/nop2.1226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Brazeau CM, Schroeder R, Rovi S, Boyd L. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med. 2010;85(10):S33–6. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4c47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Emold C, Schneider N, Meller I, Yagil Y. Communication skills, working environment and burnout among oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(4):358–63. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2010.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools