Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Value Attributed to the Therapist’s Directiveness and Support in the Psychotherapeutic Process

1 Department of Psychology, University of Cádiz, Puerto Real, 11519, Spain

2 Institute for Social and Sustainable Development (INDESS), University of Cádiz, Jerez de la Frontera, 11406, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Serafín Cruces-Montes. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health Promotion and Psychosocial Support in Vulnerable Populations: Challenges, Strategies and Interventions)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(2), 125-136. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.059526

Received 10 October 2024; Accepted 24 January 2025; Issue published 03 March 2025

Abstract

Background: Research on therapeutic processes has explored the elements that enhance psychotherapy’s effectiveness, particularly the role of common factors across various models. The therapist’s use of directiveness and support, as common variables, is crucial for effective treatment. Effective therapists adapt their level of directiveness and support according to the treatment phase, the issue being addressed, and the patient’s characteristics. This study examines the importance therapists attribute to directiveness and support, as well as its relationship with theoretical orientation, access to research publications, and stance on the similar effectiveness of different psychotherapeutic models. It aims to determine whether therapists’ attributions regarding this variable are in line with the importance it is given in process research. Methods: Responses from 69 psychotherapists to the Psychotherapeutic Effectiveness Attribution Questionnaire (PEAQ-12), which assesses the importance therapists place on key psychotherapeutic process variables, including the directiveness and support provided, were analyzed. Theoretical orientations, ages, and experience levels were considered. Non-parametric tests, contingency tables, χ2 tests, t-tests, and ANOVAs were used to assess the variation in responses. Results: Common factors were often identified as key contributors to therapeutic healing, though these differences were not statistically significant (χ2 (2, N = 67) = 3.701, p = 0.157). For the “directiveness and support from the therapist” variable, significant differences were observed: Cognitive-behavioral therapists valued directiveness and support more than psychodynamic therapists (t (20) = −3.569, p = 0.002; Cohen’s d = 1.18). Therapists who view cognitive-behavioral therapies as most effective also rated this variable higher (t (38) = 3.816, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.21). Those regularly accessing specialized psychotherapy research publications valued this variable less than those who do so occasionally (t (64) = −2.693, p = 0.009; Cohen’s d = 0.65). Therapists who support the similar effectiveness of different models tend to favor common factors, including directiveness and support (χ2 (2, N = 66) = 12.522, p = 0.002). Conclusions: Therapists express doubts about the factors influencing psychotherapy’s effectiveness, reflecting the ongoing debate. They align their views on the importance of directiveness and support with their theoretical orientation and positioning on the similar effectiveness of psychotherapies. The importance of analyzing therapists’ attributions about the factors responsible for therapeutic change is emphasized, which will impact clinical practice. Advocacy for therapist flexibility and adaptation of therapy to the patient’s needs, including the level of directiveness and support provided, has been shown to be essential for effective psychotherapy.Keywords

Therapeutic process research has been responsible for analyzing, over the past few decades, those elements that make psychotherapy effective. In this regard, traditionally, the greatest responsibility for therapeutic healing was attributed to the specific variables of psychotherapies [1], although later numerous studies claimed such responsibility for common factors [2,3]. From this standpoint, the predominant value of common variables is emphasized in providing effectiveness to psychological treatments, justifying that such shared elements are responsible for the similar effectiveness of different psychotherapeutic models [4,5]. Consequently, common variables associated with the patient (such as expectations of recovery and trust in the therapist), the therapist (including demonstrated empathy and listening abilities), and the therapeutic interaction (like the strength of the therapeutic alliance) would account for a significant portion of the change observed in therapy [6–10]. Although there seems to be a greater emphasis on common factors and variables than on specific ones in explaining the therapeutic change process, the debate on the active components in psychotherapy remains open today [11–14], still requiring a greater amount of quality research to establish it [15].

Focusing on common therapist-specific variables, an essential element to consider is therapist directiveness and support, defined as the degree to which instructions, information, specific help, and task structuring and delimitation are provided [16]. Support is understood as social support [17], as it is established within the dynamics of the interaction between therapist and patient. Traditionally, “directiveness” and “support” from the therapist have been jointly examined in studies of the therapeutic process [18,19], due to their combined action in that process. In fact, in the Psychotherapy Process Inventory conducted by Baer et al. [20], directiveness and support constitute a single factor composed of 8 items that reflect the level of guided activity by the therapist and the concern and support for the patient during the course of treatment. Such an association between both variables has been used in more recent studies [21–23].

The therapist’s ability to direct the psychotherapeutic process towards the patient’s improvement and the degree of support the therapist offers to the patient during psychotherapy have been considered attributes of an effective therapist [24]. Characteristics that may influence adherence to treatment, the intention to seek professional help, and even the effectiveness of psychotherapy [25]. Various studies on directiveness and support, as documented by Bergin et al. [26], indicate a predominance of positive associations between this variable and favorable results when it is applied moderately. For beneficial outcomes, an effective therapist must adjust their level of directiveness and support according to the treatment phase, the nature of the issue discussed in the consultation, and the patient’s personality traits [16,27,28], establishing flexibility as a crucial quality of a proficient therapist [29].

The present study aims to analyze the importance therapists place on the therapist’s directiveness and support as a variable in the therapeutic change process. We consider it necessary to analyze the importance therapists attribute to this variable, as it has been shown to not only be a relevant element in psychotherapy but also to contribute to improving treatment effectiveness. Likewise, patients exhibit preferences for specific characteristics of the therapist and certain forms of treatment, making it essential to examine their preferences regarding the directiveness and support they receive during therapy [30,31]. In this regard, studies such as those conducted by Cooper et al. [32,33] have concluded that patients tend to prefer directiveness over non-directiveness. Furthermore, agreement between patients and their therapists on the helpful aspects of psychotherapy has been associated with reductions in symptoms and interpersonal problems [34]. Given the evidence supporting that agreement with patients’ preferences is crucial, it becomes particularly relevant to understand the importance therapists place on the directiveness and support they provide, aiming for a positive psychotherapeutic outcome.

In this way, we will focus on the importance that therapists attach to the directiveness and support they provide in developing their treatments. We will also explore whether certain conditions of the therapist are related to their attributions. These aspects include the therapist’s theoretical perspective, how often they consult academic articles on psychotherapy research, and their position on the similarity in effectiveness of different psychotherapeutic models.

Based on the main objective of this study, which is to analyze therapists’ attributions regarding the common type variable “directiveness and support” provided, the following hypotheses are established:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The psychotherapists will attribute the highest responsibility for the therapeutic change process to common variables over specific variables (technique and therapeutic approach used).

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Therapists who frequently consult specialized research publications in psychotherapy tend to attribute significantly more importance to the directiveness and support variable compared to those who refer to these publications sporadically.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The theoretical orientation of psychotherapists will impact the importance they place on directiveness and support provided in their treatments.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Therapists who advocate for the comparable effectiveness of different therapeutic models will significantly value common variables, including therapist directiveness and support, more than specific variables.

The target study population included 134 practicing clinical psychologists registered in the directory of the Official College of Psychologists of Western Andalusia. The questionnaire was sent through this institution to those interested in participating in the study. Finally, a total of 69 subjects completed the questionnaire. These therapists differed in their theoretical orientations, age and levels of experience. Recommendations from the literature were followed to ensure the validity of the analyses for small samples [35,36].

Along with the questionnaire, they were sent an informative letter guaranteeing the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. The study adhered to the Helsinki Declaration [37] and the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, dated December 5, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights, in line with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and the Council, dated 27 April 2016. The Bioethics Committee of the University of Cádiz stated that no potential ethical risks were identified in the present study (report of 6th July 2023).

Among the psychotherapists surveyed, 35 were male and 34 were female, accounting for 50.7% and 49.3% of the group, respectively. The mean age of the participants was 41.46 years, with a standard deviation of 6.41. In terms of educational attainment, 52.2% held a university degree, while 47.8% possessed a postgraduate or doctoral degree. Regarding their experience as psychotherapists, most of the subjects studied said they had experience of more than nine years (78.3%), followed by those with experience of between 6 and 9 years (14.5%), between 0 and 3 years (4.3%) and, lastly, those with experience of between 3 and 6 years, representing only 2.9% of the respondents.

With respect to theoretical orientation, cognitive-behavioral was the most common, making up 44.9% of the total surveyed population. This was followed by psychodynamic orientation at 26.1%, eclectic orientation at 15.9%, and humanistic-systemic orientation at 10.1%.

An ad hoc self-administered questionnaire was developed to collect the necessary data for the study. The questionnaire can be distinguished into two thematic blocks:

The Psychotherapeutic Effectiveness Attribution Questionnaire (PEAQ-12) [38]. The items of this scale refer to the main psychotherapeutic variables considered relevant in the therapeutic change process, divided into four main dimensions: Enhancers of the therapeutic alliance, Therapy-specific variables, Facilitators of patient participation in therapy and Common therapist variables (a dimension that would include, among others, the therapist’s directiveness and support variable). Therapists had to rate each item from 1 to 5, where 1 indicated “does not influence the patient’s improvement” and 5 meant “greatly influences”. The items included: 1) Therapeutic approach; 2) Techniques or procedures; 3) Patient’s expectation of healing; 4) Patient’s involvement; 5) Patient’s credibility and faith in the psychotherapist; 6) Psychotherapist’s empathy; 7) Psychotherapist’s directiveness and support; 8) Psychotherapist’s perception of the patient’s involvement; 9) Psychotherapist’s ability to influence the patient; 10) Degree of understanding, acceptance, and encouragement shown by the psychotherapist; 11) Psychotherapist’s experience; 12) Establishment of a therapeutic alliance. The alpha coefficient for the 12 items stood at α = 0.727, based on 63 valid cases. This coefficient indicates internal consistency that is more than satisfactory for that number of items [39].

Demographic characteristics and therapist’s characteristics. In this section, information was collected on aspects such as therapists’ experience, theoretical orientation, level of access to publications on psychotherapy research, position on common and specific factors in psychotherapy, belief in the similarity in effectiveness of different psychotherapies, consideration of the most important common factor for healing and preference for the most effective psychotherapeutic model.

In the first approach, frequencies and basic descriptive statistics were obtained, in addition to carrying out non-parametric tests (goodness-of-fit tests such as the Chi-square test for a sample and the binomial test). Contingency tables and χ2 tests were conducted on selected variables to explore the presence of relationships between them. Additionally, t-tests, one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) (including Tukey’s post-hoc and planned comparisons) and Welch’s F-test and Brown-Forsythe’s test were utilized to investigate potential significant differences in the evaluation of psychotherapeutic variables, with mean contrasts performed for both independent and related samples. Cohen’s d value was also calculated to determine the effect size (Very small = 0.00–0.19, Small = 0.20–0.49, Medium = 0.50–0.79, Large = >0.80).

Data analysis was conducted using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. Outcomes with a p-value below 0.05 were considered significant.

In the initial analysis, the perspectives of psychotherapists in the study were examined concerning the factors they deemed most crucial for a patient’s healing during psychotherapy. Common factors were more frequently identified as the primary contributors to therapeutic healing, accounting for 39.1% of responses. The second-highest percentage, 36.2%, attributed healing to the combined influence of both specific and common factors, whereas specific factors alone were considered least influential, noted by 21.7% of respondents. However, the differences in the choice of factors regarded as responsible for healing did not reach statistical significance (χ2 (2, N = 67) = 3.701, p = 0.157). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the preferences for common factors over specific factors among therapists (p = 0.090).

Significantly more participants disagreed that the effectiveness of psychotherapies is similar (73.9% vs. 23.2%) (p < 0.001). Among psychotherapists who disagree with such similarity, the percentage who select their own modality as the most effective is significantly greater than the proportion favoring another modality (p < 0.001).

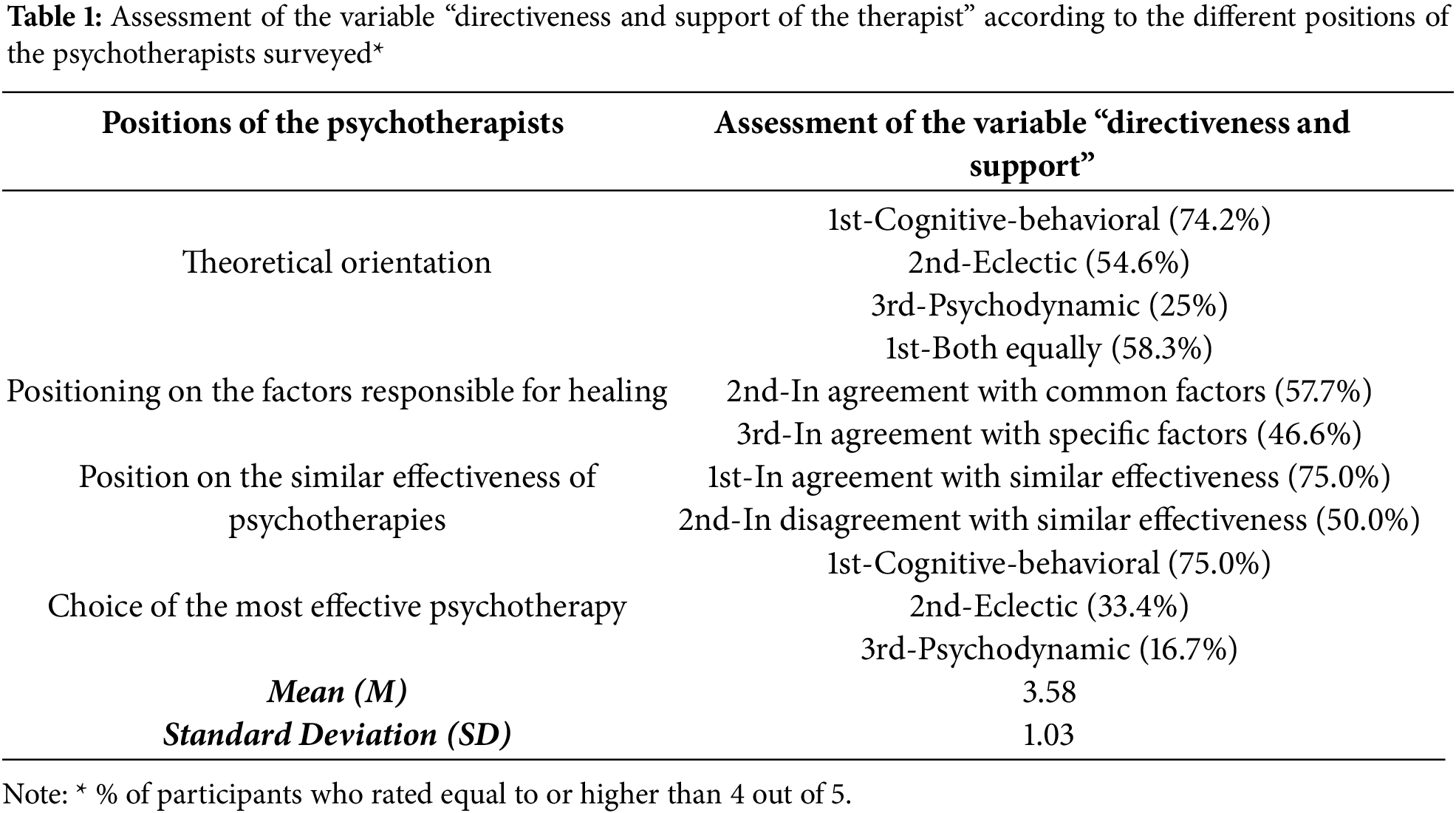

As for the analysis of the variable “directiveness and support of the therapist”, the mean rating of this variable is 3.58. 36.2% of the psychotherapists surveyed rated this variable as a 4. Other descriptive results are summarized in Table 1.

The significant differences found in assessing the variable “directiveness and support of the therapist” are presented following.

Using a one-way ANOVA, we determined that the null hypothesis of equal variances could be rejected, F (3, 61) = 3.11, p = 0.033. The significance levels obtained in the Welch F-tests, F (3, 18.94) = 4.4, p = 0.016, and Brown-Forsythe, F (3, 36.39) = 4.99, p = 0.005, indicate that the populations of therapists of the different theoretical orientations do not similarly value this variable.

It is interesting to specify where the detected differences are to be found. When comparing the mean of psychodynamic therapists (M = 2.81, SD = 1.22) with that of cognitive-behavioral therapists (M = 4.00, SD = 0.73), a significant difference appears in favor of the latter (t (20) = −3.569, p = 0.002). The effect size, as measured by Cohen’s d, was d = 1.18, indicating a large effect.

4.2 Access to Specialist Publications

Those who regularly access specialized publications on psychotherapy research place significantly less importance on this variable compared to those who access such publications occasionally or without a set frequency (t (64) = −2.693, p = 0.009), the respective means being M = 3.34, SD = 1.10 and M = 3.96, SD = 0.77). The Cohen’s effect size was d = 0.65, indicating a medium effect.

4.3 Choice of the Most Effective Psychotherapy

Therapists who indicate cognitive-behavioral therapies (M = 4.00, SD = 0.81) as the most effective significantly value directiveness and support more than those in favor of the psychodynamic type (M = 2.75, SD = 1.21) (t (38) = 3.816, p < 0.001). The effect size was d = 1.21, indicating a large effect.

4.4 Position on the Similarity in Effectiveness of Psychotherapies

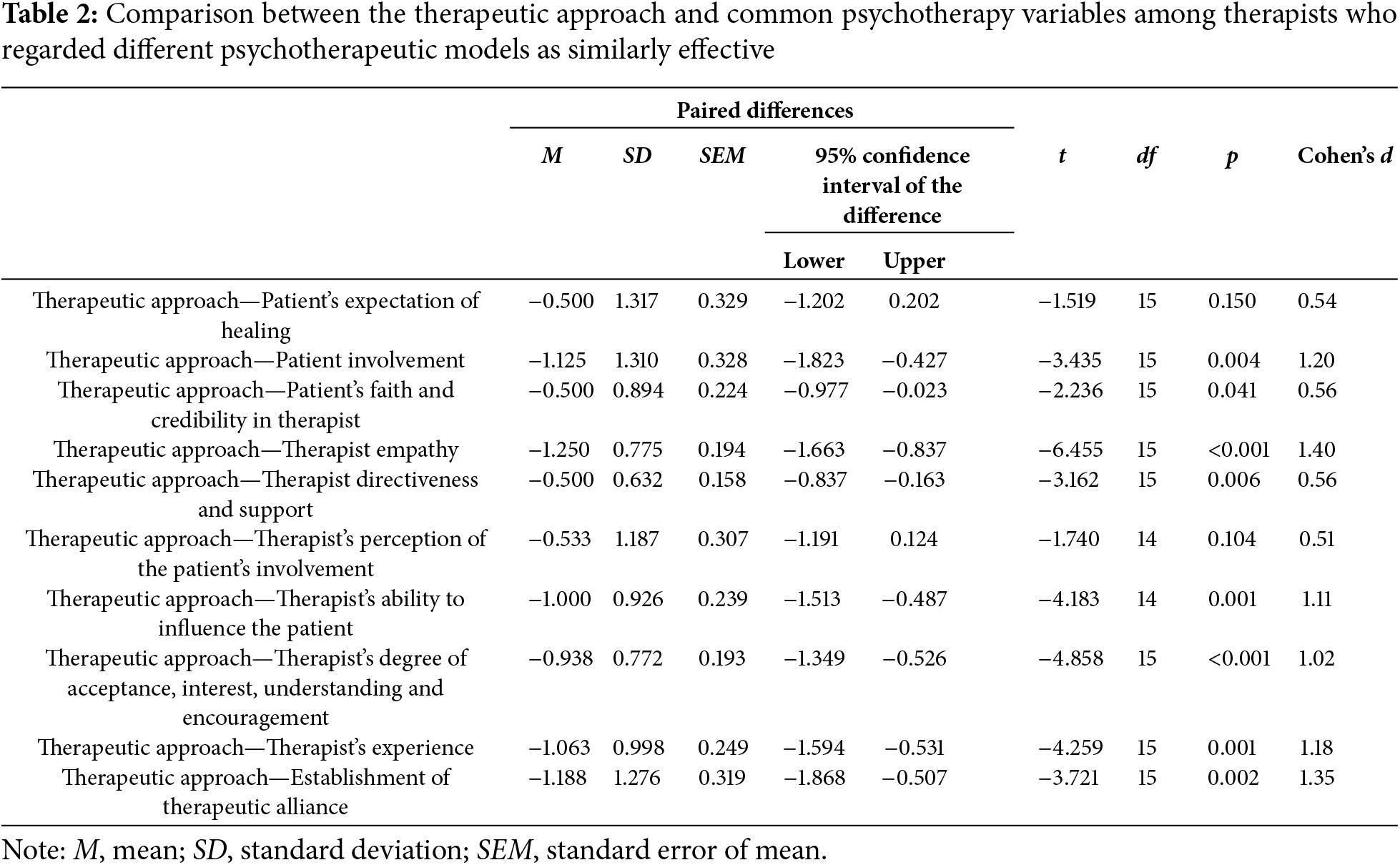

Attending to therapists who are in favor of similar effectiveness of different psychotherapies, we find that a firm positioning is manifested in favor of common factors over those of a specific type (p < 0.001). Specifically, 75% of these therapists consider common factors to be the primary contributors to the effectiveness of psychotherapy (χ2 (2, N = 66) = 12.522, p = 0.002). A more exhaustive analysis leads us to analyse the evaluations that these psychotherapists make of the variables presented in the survey. Consequently, among the ten comparisons made between the specific variable “therapeutic approach” (M = 3.25, SD = 0.93) and each of the common variables (Table 2), significant differences were found in eight instances, consistently favoring the common variables, including the “directiveness and support of the therapist” (t (15) = −3.162, p = 0.006).

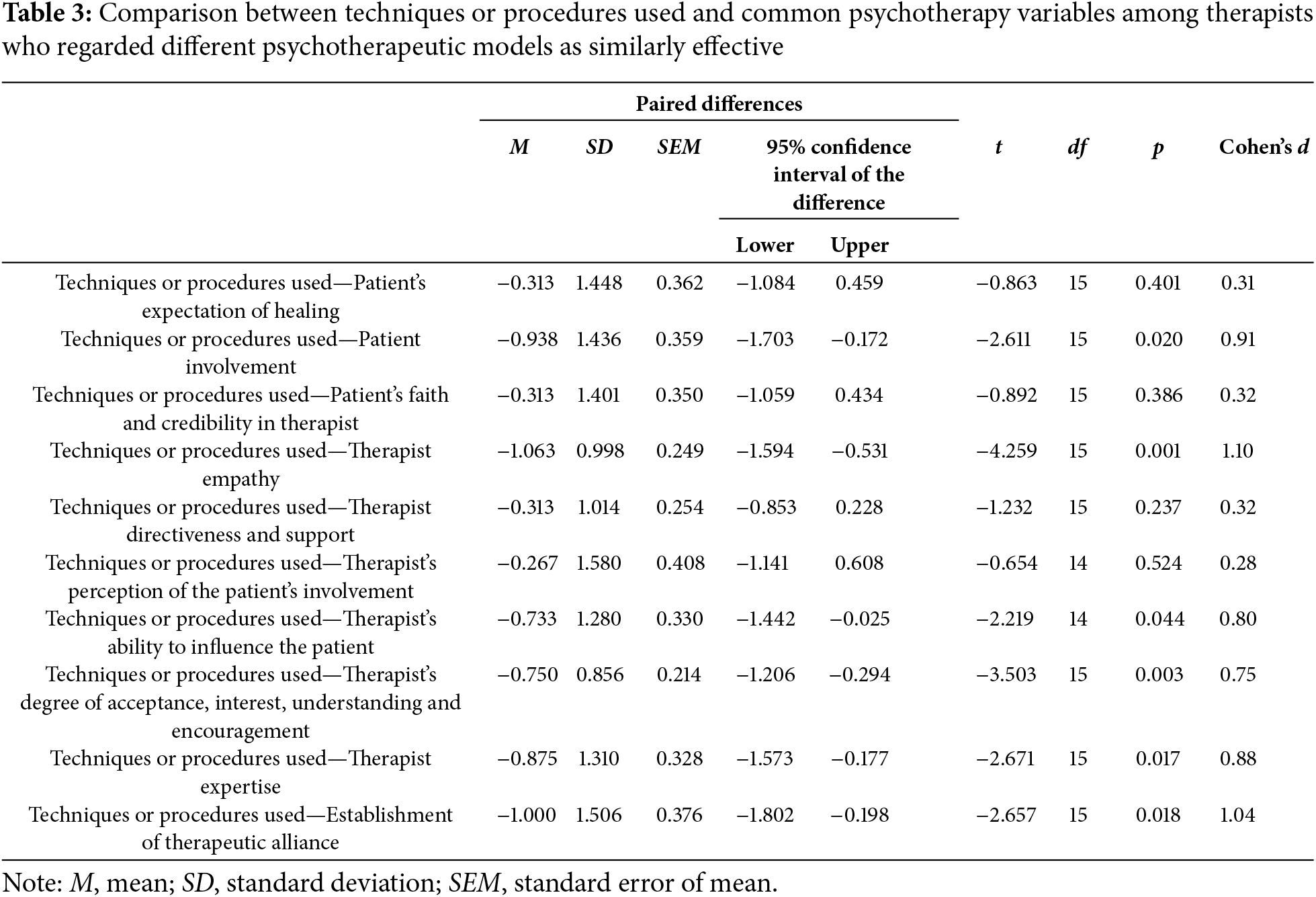

Comparisons involving the other specific variable, “techniques and procedures employed” (M = 3.44, SD = 1.09) and the ten common variables examined in the study (Table 3) also show a significant number of significant differences in favor of the common variables (six in total).

Fourteen significant differences were found out of twenty comparisons, all favoring common variables, including therapist directiveness and support. In contrast, in the group of therapists opposed to the similarity in effectiveness of the different psychotherapeutic models, only eight significant differences were found when making the same comparisons, and only three were in favor of common variables.

The present study has focused on the analysis of therapists’ attributions regarding the relevance of the common variable “directiveness and support”. Other studies have similarly analyzed the importance attributed to common variables such as the therapist’s emotional traits or the therapeutic alliance [22,40]. While attributions have been a central topic in psychology for decades [41], we consider their application to the variables responsible for therapeutic change to represent a novel line of research.

Common variables, among which we can include therapist directiveness and support, have been shown to be crucial for the success of psychotherapy [42,43]. However, their superiority over specific ingredients continues to be debated today [15].

Despite the importance of these shared elements, the current study indicates that common-type variables are not highly regarded by the therapists surveyed, or at least not distinctly more than the specific-type variables. Contrary to what we posited in our first hypothesis, they do not attribute a differential value to the common components over the specific ones. Our data indicate that therapists continue to hold some uncertainties regarding the factors that contribute to the effectiveness of the therapies they provide. However, a possible explanation for this result might be that it reflects the unresolved state regarding the issue of specific vs. common factors, which in turn would also explain the therapists’ indecision when positioning themselves on the factors responsible for therapeutic change.

A more detailed analysis of the valuation of the directiveness and support variable based on the different characteristics of therapists shows that those who regularly access specialized publications on psychotherapy research place significantly less value on this variable than those who access them occasionally. As mentioned, numerous studies within process research highlight the primacy of common factors over specific ones in the effectiveness of psychotherapy [10]. Since “directiveness and support” is primarily considered a common variable, present to varying degrees in different psychotherapeutic modalities, one would expect that therapists who frequently access such specialized publications would value this variable more than those who access them infrequently. Again, this result may indicate that psychotherapists are aware of the uncertain state of the debate over specific vs. common factors.

Cognitive-behavioral therapists prioritize the directiveness and support given to the patient within the context of psychotherapy more than psychodynamic therapists do, consistent with the findings of other studies [30,33]. Congruently, therapists who regard cognitive-behavioral psychotherapies as the most effective place significantly more value on this variable than those who favor psychodynamic approaches. These findings align with the principles of cognitive-behavioral therapies, where the therapist takes a more directive role in the intervention, in contrast to psychoanalytic therapies, where the therapist avoids giving advice or adopting a directive approach [30].

On the other hand, therapists who support the notion of similar effectiveness across different psychotherapeutic models tend to favor common factors over specific ones and rate the various common variables, including the therapist’s directiveness and support, significantly higher than the specific variables. This perspective is not observed in therapists who disagree with the idea of similar effectiveness among psychotherapies. The assumption that acknowledging the similar effectiveness of various psychotherapeutic models leads to an appreciation of the fundamental value of the common elements shared by these models is reinforced. This rationale is grounded in the concept that the similar effectiveness of psychotherapies is attributed to these shared characteristics rather than the aspects that distinguish them, a principle extensively documented in research on psychotherapeutic processes [4,44,45].

Regarding the limitations of the current study, it is worth noting the sample size, which makes it a preliminary exploratory study. Although guidelines from the literature were adhered to in order to ensure the validity of the analyses for small sample sizes [35,36], it would be necessary, in order to confirm the results, to replicate the research with larger samples of psychotherapists from various theoretical orientations. Similarly, given its preliminary nature, various aspects could influence the attributions analyzed, such as the type of pathology being treated, the structure, and number of sessions. Moreover, other therapist characteristics such as flexibility, personal style of the therapist, or therapeutic skills must be studied [46]. Similarly, it is necessary to examine the influence of other variables involved in therapy, such as treatment engagement, the therapist’s regard for clients, and the therapist’s expectation of the patient’s improvement, which would support the generalization of the results.

Although, as mentioned, a study with a larger population of therapists from a greater number of psychotherapeutic approaches is necessary to confirm the findings, a clear stance cannot be inferred from therapists regarding specific or common factors as the primary drivers of therapeutic change. Similarly, therapists who frequently consult psychotherapy research publications do not place greater value on directiveness and support compared to those who consult them occasionally, resulting in the rejection of our second hypothesis. However, regarding the importance given to directiveness and support, when considering characteristics such as theoretical orientation and stance on the similar effectiveness of psychotherapies, our therapists behave as expected, leading to the acceptance of our third and fourth hypotheses. Thus, in terms of theoretical orientation, those with a cognitive-behavioral approach place more importance on directiveness and support provided to the patient than psychodynamic therapists do, which seems consistent with the assumptions of their theoretical orientation. Moreover, regarding therapists’ perspectives on the comparable effectiveness of different psychotherapeutic models, our findings align. It is only therapists who support the idea of similar effectiveness across psychotherapies who attribute common factors, including directiveness and support, as the primary drivers of therapeutic change.

We consider the study of psychotherapeutic attributions an emerging line of research of interest, as it provides relevant information on potential discrepancies between findings from psychotherapeutic process research and therapists’ subjective perceptions regarding the contribution of various variables involved in the therapeutic change process, which would impact the clinical practice they perform. While the issue of the factors responsible for therapeutic change is not settled, if the discrepancies found were very evident, they would require action proposals such as improving the channels for transmitting the results of therapeutic process research and promoting an integrative vision aimed at a pragmatic combination of perspectives and therapeutic techniques. Similarly, we advocate for therapist flexibility and for adapting therapy, as much as possible, to the needs, characteristics, and reactance of the patient [47–49]. In particular, this applies to the level of directiveness and support provided, as it is a crucial aspect for ensuring the successful progress of psychotherapy [50]. However, such adaptation must be approached with caution, weighing the potential risks of excessive accommodation to the patient’s preferences [30].

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The contribution of each author is detailed below: Antonio Romero-Moreno: Principal investigator, study conception and design and theoretical approach; Lorenzo Rodríguez-Riesco: Methodology and analysis of data and results; Isaac Lavi: Discussion and research support; Serafín Cruces-Montes: Draft manuscript preparation and research supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval was not required. The Bioethics Committee of the University of Cádiz, in its report dated 6 July 2023, stated that no potential ethical risks were identified in the present study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. At all times the authors have adhered to the universal ethical principles that govern the conduct of research in psychology, including safeguarding confidentiality and obtaining informed consent from the participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2013 (Seventh revision, 64th Meeting, Fortaleza) and the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights in accordance with the Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 27 April 2016.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Norcross JC, Goldfried MR. Handbook of psychotherapy integration. 3rd ed. New York, NY, USA: Oxford Academic; 2019. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/9780190690465.001.0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Alldredge CT, Burlingame GM, Yang C, Rosendahl J. Alliance in group therapy: a meta-analysis. Group Dyn Theory Res Pract. 2021;25(1):13–28. doi:10.1037/gdn0000135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Finsrud I, Nissen-Lie HA, Vrabel K, Høstmælingen A, Wampold BE, Ulvenes PG. It’s the therapist and the treatment: the structure of common therapeutic relationship factors. Psychother Res. 2022;32(2):139–50. doi:10.1080/10503307.2021.1916640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wachtel PL, Siegel JP, Baer JC. The scope of psychotherapy integration: introduction to a special issue. Clin Soc Work J. 2020;48(3):231–35. doi:10.1007/s10615-020-00771-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, Stich E, Benson K, Ahn H. A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: empirically, “all must have prizes”. Psychol Bull. 1997;122(3):203–15. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.122.3.203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cuijpers P, Driessen E, Hollon SD, van Oppen P, Barth J, Andersson G. The efficacy of non-directive supportive therapy for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(4):280–91. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Karson M, Fox J. Common skills that underlie the common factors of successful psychotherapy. Am J Psychother. 2010;64(3):269–81. doi:10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2010.64.3.269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Safran JD, Muran JC. Negotiating the therapeutic alliance: a relational treatment guide. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

9. Samstag L, Muran JC, Safran JD. Defining and identifying alliance ruptures. In: Charman D, editor. Core processes in brief psychodynamic psychotherapy: advancing effective practice. Hillsdale, MI, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. p. 187–214. [Google Scholar]

10. Wampold BE. What should we practice? A contextual model for how psychotherapy works. In: Rousmaniere TG, Goodyear RK, Miller SD, Wampold BE, editors. The cycle of excellence: using deliberate practice to improve supervision and training. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley; 2017. p. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

11. Emmelkamp PM, David D, Beckers T, Muris P, Cuijpers P, Lutz W, et al. Advancing psychotherapy and evidence-based psychological interventions. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(S1):58–91. doi:10.1002/mpr.1411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hofmann SG, Barlow DH. Evidence-based psychological interventions and the common factors approach: the beginnings of a rapprochement? Psychotherapy. 2014;51(4):510–13. doi:10.1037/a0037045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Mulder R, Murray G, Rucklidge J. Common versus specific factors in psychotherapy: opening the black box. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(12):953–62. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30100-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Tolin DF, McKay D, Forman EM, Klonsky ED, Thombs BD. Empirically supported treatment: recommendations for a new model. Clin Psychol-Sci Pract. 2015;22(4):317–38. doi:10.1037/h0101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cuijpers P, Reijnders M, Huibers MJ. The role of common factors in psychotherapy outcomes. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019;15(1):207–31. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Bados A, García E. Habilidades terapéuticas. Barcelona, Spain: Universitat de Barcelona; 2011 (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

17. Lakey B, Cohen S. Social support theory and measurement. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: a guide for health and social scientists. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

18. Lafferty P, Beutler LE, Crago M. Differences between more and less effective psychotheapists: a study of select therapist variables. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(1):76–80. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.57.1.76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Kaluzeviciute-Moreton G, Lloyd C. ‘Meeting the client where they are rather than where I’m At’: a qualitative survey exploring CBT and psychodynamic therapist perceptions of psychotherapy integration. Brit J Psychother. 2024;40(2):150–74. doi:10.1111/bjp.12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Baer PE, Dunbar PW, Hamilton JE, Beutler LE. Therapists’ perceptions of the psychotherapeutic process: development of a psychotherapy process inventory. Psychol Rep. 1980;46(2):563–70. doi:10.2466/pr0.1980.46.2.563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Bachler E, Aas B, Bachler H, Viol K, Schöller HJ, Nickel M, et al. Long-term effects of home-based family therapy for non-responding adolescents with psychiatric disorders. A 3-year follow-up. Front Psychol. 2020;11:475525. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.475525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Romero-Moreno A, Paramio A, Cruces-Montes S, Zayas A, Guil R. Attributed contribution of therapist’s emotional variables to psychotherapeutic effectiveness: a preliminary study. Front Psychol. 2021;12:644805. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Thal SB, Wieberneit M, Sharbanee JM, Skeffington PM, Bruno R, Wenge T, et al. Dosing and therapeutic conduct in administration sessions in substance-assisted psychotherapy: a systematized review. J Humanist Psychol. doi:10.1177/00221678231168516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Navarro A, Schindler L, Silva F. Evaluación de la conducta del psicoterapeuta: preferencias del cliente. Eval Psicol. 1987;3:101–23 (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

25. Beutler L. Have all won and must all have prizes? Revisting luborsky et al.’s veredict. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:226–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Bergin AE, Garfield SL. Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

27. Karmo M, Beutler L, Harwood T. Interactions between psychotherapy procedures and patient attributes that predict alcohol treatment effectiveness: a preliminary report. Addict Behav. 2002;27(5):779–97. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00209-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Keijsers G, Schaap C, Hoodgduin C. The impact of interpersonal patient and therapist behavior on outcome in cognitive-behavior therapy. Behav Modificat. 2000;24(2):264–97. doi:10.1177/0145445500242006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Collard J. Use of self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) exercises for competency-based training and assessment in CBT. Cogn Beh Therap. 2024;17(1):1–13. doi:10.1017/S1754470X23000375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Heinze PE, Weck F, Hahn D, Kühne F. Differences in psychotherapy preferences between psychotherapy trainees and laypeople. Psychother Res. 2022;33(3):374–86. doi:10.1080/10503307.2022.2098076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Swift JK, Callahan JL, Cooper M, Parkin SR. The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(11):1924–37. doi:10.1002/jclp.22680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Cooper M, Norcross JC, Raymond-Barker B, Hogan TP. Psychotherapy preferences of laypersons and mental health professionals: whose therapy is it? Psychotherapy. 2019;56(2):205–16. doi:10.1037/pst0000226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Cooper M, van Rijn B, Chryssafidou E, Stiles WB. Activity preferences in psychotherapy: what do patients want and how does this relate to outcomes and alliance? Couns Psychol Q. 2021;35(3):503–26. doi:10.1080/09515070.2021.1877620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chui H, Palma B, Jackson JL, Hill CE. Therapist-client agreement on helpful and wished-for experiences in psychotherapy: associations with outcome. J Couns Psychol. 2020;67(3):349–60. doi:10.1037/cou0000393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. De Winter JC. Using the Student’s t-test with extremely small sample sizes. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2013;18(10):1–12. doi:10.7275/e4r6-dj05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Shingala MC, Rajyaguru A. Comparison of post hoc tests for unequal variance. Int J Eng Sci Technol. 2015;2(5):22–33. [Google Scholar]

37. World Medical Association. World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–4. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Romero-Moreno A, Paramio A, Cruces-Montes SJ, Zayas A, Gómez-Carmona D, Merchán-Clavellino A. Development and validation of the Psychotherapeutic Effectiveness Attribution Questionnaire (PEAQ-12) in a Spanish population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):1–15. doi:10.3390/ijerph181910372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. New York, NY, USA: Sage; 2024. [Google Scholar]

40. Romero-Moreno AF, Paramio A, Cruces-Montes SJ, Guil-Bozal R. Attributions about the role of the therapeutic alliance in the effectiveness of psychotherapy. In: Martos A, Simón MM, Gázquez JJ, Molina P, Sisto M, editors. Investigación y desarrollo de recursos de intervención en contextos clínicos y de la salud. Madrid, Spain: Dikynson; 2023. p. 49–61 (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

41. Malle BF, Korman J. Attribution theory. In: Dunn DS, editor. Oxford bibliographies in psychology. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

42. Hoffart A, Borge FM, Sexton H, Clark DM. The role of common factors in residential cognitive and interpersonal therapy for social phobia: a process-outcome study. Psychother Res. 2009;19(1):54–67. doi:10.1080/10503300802369343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wampold BE. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiat. 2015;14(3):270–7. doi:10.1002/wps.20238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lambert MJ, Ogles BM. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In: Bergin AE, Garfield SL, Lambert MJ, editors. Handbook of psychotherapy and behaviour change. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley; 2004. p. 139–93. [Google Scholar]

45. Nahum D, Alfonso CA, Sönmez E. Common factors in psychotherapy. In: Javed A, Fountoulakis K, editors. Advances in psychiatry. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 471–81. [Google Scholar]

46. Alfonsson S, Fagernäs S, Beckman M, Lundgren T. Psychotherapist factors that patients perceive are associated with treatment failure. Psychotherapy. 2024;61(3):241–9. doi:10.1037/pst0000527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Bennett SD, Shafran R. Adaptation, personalization and capacity in mental health treatments: a balancing act? Curr Opin Psychiat. 2023;36(1):28–33. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Gimeno-Peón A. Trabajando con las preferencias del consultante en psicoterapia: consideraciones clínicas y éticas. Papel Psicol. 2023;44(3):125–31 (In Spanish). doi:10.5555/ScF8aU8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Gismero-González E. El cliente: el verdadero agente del cambio en psicoterapia: implicaciones para los psicoterapeutas. Misc Comillas. 2021;79(154):337–53 (In Spanish). doi:10.14422/mis.v79.i154.y2021.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Beutler LE, Edwards C, Someah K. Adapting psychotherapy to patient reactance level: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(11):1952–63. doi:10.1002/jclp.22682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools