Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Post-COVID-19 Challenges for Full-Time Employees in China: Job Insecurity, Workplace Anxiety and Work-Life Conflict

1 Business School, Ningbo University, Ningbo, 315211, China

2 International Business School, Hainan University, Haikou, 570228, China

* Corresponding Author: Xianyi Long. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring anxiety, stress, depression, addictions, executive functions, mental health, and other psychological and socio-emotional variables: psychological well-being and suicide prevention perspectives)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(9), 719-730. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.053705

Received 08 May 2024; Accepted 13 August 2024; Issue published 20 September 2024

Abstract

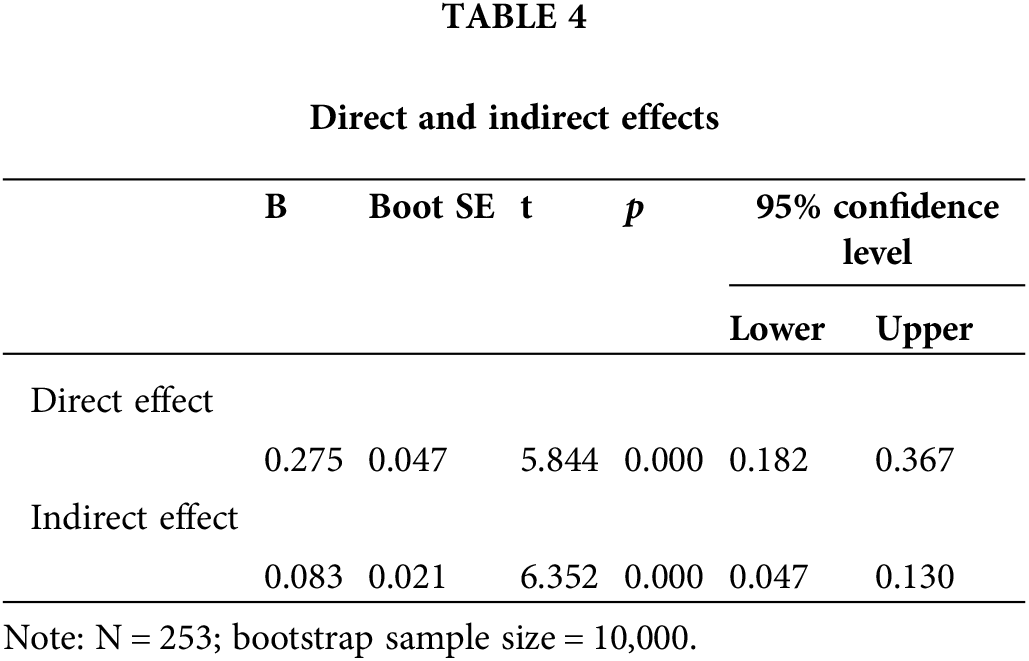

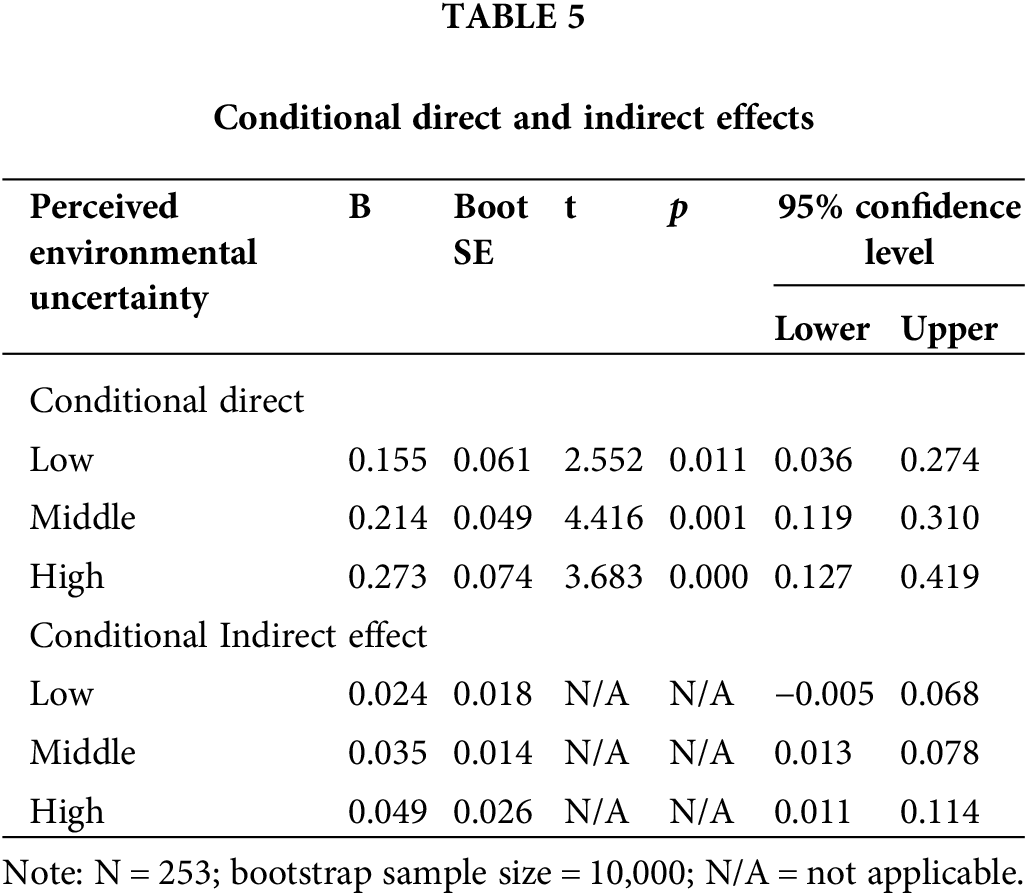

Background: Though the COVID-19 pandemic recedes, and our society gradually returns to normal, Chinese people’s work and lifestyles are still influenced by the “pandemic aftermath”. In the post-pandemic era, employees may feel uncertainty at work due to the changed organizational operations and management and perceive the external environment to be more dynamic. Both these perceptions may increase employees’ negative emotions and contribute to conflicts between work and life. Drawing from the ego depletion theory, this study aimed to examine the impact of job insecurity during the post-pandemic era on employees’ work-life conflicts, and the mediating effect of workplace anxiety in this relationship. Besides, this study also considered the uncertainty of the external macro environment as a boundary condition on the direct and indirect relationship between job insecurity and work-life conflicts. Methods: A two-wave questionnaire survey was conducted from October to December 2023 to collect data. MBA students and graduates from business school with full-time jobs are invited to report their perception of job insecurity, work anxiety, perceived environment uncertainty, and work-life conflict. This resulted in 253 valid responses. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS, Amos, and PROCESS. Results: The results showed that: (1) Employees’ job insecurity would directly intensify the work-life conflict (B = 0.275, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.182, 0.367]). (2) Employees’ workplace anxiety mediates the relationship between job insecurity and work-life conflict (B = 0.083, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.047, 0.130]). (3) The mediating effect of workplace anxiety between job insecurity and work-life conflict exists when perceived environmental uncertainty is high (B = 0.049, 95% CI [0.011, 0.114]), while vanishes when perceived environmental uncertainty is low (B = 0.024, 95% CI [−0.005, 0.068]). Conclusion: Job insecurity combined with perceived environmental uncertainty in the post-pandemic era fuels employees’ workplace anxiety and work-life conflicts. Post-pandemic trauma lingers, necessitating urgent attention and response.Keywords

As the world emerges from the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is evident that profound changes have occurred [1]. There is no doubt that the global outbreak of COVID-19 over the past three years has threatened human life and health, and caused significant changes in our work and life [2]. However, have the lingering effects of the COVID-19 been completely eradicated in the post-pandemic era? Our study aims to answer this question by exploring the challenges faced by full-time employees in their work and nonwork lives within organizational contexts.

It is evident that the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic persists despite the apparent end of acute crisis conditions. Firstly, notwithstanding the notable decline in the virulence of the COVID-19 virus, the unpredictable emergence of mutated strains remains a significant concern, leaving open the possibility of future outbreaks and the hovering specter of potential harm. Secondly, the risks associated with COVID-19 reinfection and long-term sequelae are substantial. According to authoritative medical research, even though the most acute symptoms manifest during the initial year of infection, individuals continue to face health risks for a prolonged period post-infection [3]. Furthermore, recurrent infection cases are prevalent and anticipated to persist for a considerable duration. Moreover, long COVID-19 encompasses a spectrum of complications beyond respiratory symptoms, including olfactory dysfunction, alopecia, and ejaculatory difficulties, which significantly compromise individuals’ bodily functions and pose a prolonged threat to their well-being and daily functioning [4].

The pandemic has irrevocably altered our lives and work. Many of these changes are unlikely to revert with the termination of the current pandemic wave, presenting unresolved challenges for employees across various industries in the post-COVID-19 era. Our research underscores that, despite the normalization of the pandemic, the societal risks and uncertainties it has engendered have profoundly escalated the sense of insecurity. Individuals are uncertain regarding their susceptibility to infection, the timing of potential infection, and the potential long-term sequelae, thereby posing challenges to their future expectations [5].

China, being the first nation to be struck by the COVID-19 pandemic, has experienced significant harm to its citizens’ lives and safety. In response, the Chinese government has implemented stringent control measures, including extensive home quarantine, which has drastically altered work and life during the pandemic. Compared to other countries, China’s policies for epidemic prevention and control have been more rigorous, extensive, and enduring, potentially leading to a profound impact on Chinese society. We believe this offers a unique context for our study, which explores the lingering effects of the pandemic on work and life within organizational settings in the post-pandemic era, following China’s reopening in December 2022.

We investigate the dual pressure imposed on full-time employees’ work and life by both organizational and environmental unsettling factors in the post-pandemic era. The central concern of this study lies in how organizational factor such as job insecurity is transmitted to employees’ non-work domains and how the volatility of the external environment catalyzes this process. Our study offers three key insights. Firstly, previous studies have confirmed that the COVID-19 is a crisis that causing enormous uncertainties [5]. Our research reveals that despite the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, the uncertainty it brought about remains pervasive, continuously challenging employees’ work and life. Organizations must take proactive steps to support their staff, minimizing the negative impact of this lingering uncertainty. Secondly, we delve into the emotion mechanisms through which job insecurity contributes to work-life imbalance among employees in the post-pandemic context. Severe job insecurity often results in persistent anxiety, causing employees to overextend themselves at work, thereby hampering their ability to fulfill personal roles in the nonwork domains, leading to work-life conflicts. Previous research has confirmed that uncertainty has both positive and negative effects on employees’ work outcomes during the pandemic period [6]. Our research confirms its negative impact on non-work areas in the post-pandemic era. Finally, we utilize the ego depletion theory to elucidate how anxiety transfers between work and life. Negative emotions at work deplete individuals’ psychological resources, blurring life boundaries and extending work-related anxiety into daily routines. While previous research has addressed the spillover of negative work factors, our study focuses on employees’ work emotions to explain how can work factors in the post-pandemic era spill over to life areas. This underscores the crucial role of emotion, a factor that, despite its significance, has often been overlooked in prior research.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Work and life form an inextricable union in people’s daily existence, serving as the fundamental pillars for sustaining individual survival and actualizing the essence of life. They constitute the core of our life’s endeavors, necessitating significant investments of resources, both psychological and physical. To ensure the smooth functioning of these twin domains, individuals must periodically exercise self-control. However, according to the theory of ego depletion, self-control is a finite resource, and engaging in tasks that demand it depletes this resource, diminishing one’s capacity for subsequent self-regulatory tasks [7].

Numerous articles have highlighted the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on organizations and employees. The pandemic has disrupted business operations including organizational processes, operational methods, work arrangements, and staffing plans to a great extent [8]. To cope with these disruptions, enterprises have undergone numerous operational adjustments. As the ultimate bearers and executors of organizational change, employees are under great risks and pressures. The stress and anxiety experienced by ordinary employees in the epidemic environment have been documented in previous studies [9]. With the need to maintain social distancing due to the pandemic, remote working arrangements have been adopted widely [10], offering greater flexibility for employees to adjust to their personal circumstances. However, this has also led to the blurring of boundaries between work and personal life. Studies have shown that remote working can create role conflicts for employees, as they may need to balance their responsibilities as both a good employee and a good parent [11]. Moreover, the pandemic has brought unpredictable changes to the nature of work, causing employees to feel out of control and reducing their job satisfaction [12]. More than that, the COVID-19 pandemic has had wide-ranging impacts on careers, which is a negatively valanced shock for most people [13].

Amidst a global pandemic of this scale, individuals are enduring profound physical and mental distress stemming from health hazards and the pervasive uncertainty [3,11]. In terms of health, individuals grapple with the inability to predict their infection status, struggle to effectively manage symptoms if infected, and cannot fully prevent the lingering effects of treatment. Additionally, in the societal sphere, the ever-evolving policies enacted by governments for epidemic control demand significant energy from individuals to remain vigilant and compliant. Specifically, within organizational settings, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced immense uncertainty to the workplace, notably diminishing employees’ sense of job security and thereby weakening their organizational identity. This, in turn, significantly and adversely impacts their work outcomes, including work effort, organizational citizenship behavior, and overall performance [6].

The aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic has brought many uncertainties, such as rising unemployment, altered working conditions, and heightened job stressors [14], posing a significant threat to employees’ job security. In the post-pandemic, employees may encounter even more challenging work environments, necessitating greater time and expertise to adapt to workplace changes, manage work pressure, to maintain a normal pace of life and work. The self-control resources can be restored, for example, through sufficient rest, good sleep, positive emotional experiences, etc., to fill an individual’s psychological resources and improve their self-control ability [15]. However, the sequelae of COVID-19 makes people suffer from respiratory trauma, and the quality of sleep and rest is unsatisfactory. Excessive dedication of control resources at work ultimately leads to the depletion of limited resources, hindering their restoration and subsequently compromising self-control capabilities [16]. According to the ego depletion theory, a decrease in self-control ability not only affects subsequent self-control tasks, but also affects individual emotions and behaviors, such as making individuals more prone to fatigue, anxiety, and emotional depression [17]. Many scholars have focused their research on the relationship between resource consumption and job performance, discussing the effects of depletion of self-control resources in the previous period on work behavior and attitudes in the next period [16]. Our research attempts to expand this theoretical framework, applying the ego depletion theory to analyze the dual challenges that employees face in their work and life during the post pandemic period.

Job insecurity and work-life conflict

Job insecurity means a perceived threat to the continuity and stability of employment as it is currently experienced [18]. There are many factors that can cause job insecurity, including periods of economic recession, ever-changing technologies, shifting governmental policies regarding work and labor relations, and restructuring, acquisitions, mergers, and downsizing of organizations [19]. Job insecurity has emerged as a heated research topic during the pandemic. Many scholars have affirmed that COVID-19 has led to a significant rise in employees’ job insecurity and decrease of their subsequent work outcomes [6], eventually resulting in the failure of organizational effectiveness. In the post-pandemic era, the severe ramifications of COVID-19 have stimulated organizations to utilize digital technologies and modify work processes and organizational structures, all presents challenges to employees [20]. As a consequence, job insecurity perception is enhanced and poses a threat to people’s work-related resources, such as financial security, social embeddedness, social status, and identity [14].

The research examining the ramifications of job insecurity has predominantly focused on its detrimental effects on job performance and individual subjective well-being. Job insecurity has been identified as a hazard to public health [21], a potential catalyst for health disparities [22], and a pivotal phenomenon that both fuels and stems from organizational decline [23]. Notably, empirical data has correlated job insecurity with numerous adverse organizational outcomes, encompassing compromised mental, physical, and work-related well-being; unfavorable job attitudes; diminished performance, creativity, and adaptability; as well as heightened turnover intentions and departures [18,24]. This study aims to delve deeper and scrutinize the profound implications of job insecurity, extending beyond the confines of the workplace.

Work-life conflict is an extension of work-family conflict and reflects the reality that the work role may interfere with individuals’ other personal life roles [25]. Work-Family Conflict is defined as a specific form of inter-role conflict in which the demands, pressures, or expectations of one’s work role interfere with one’s ability to satisfy the demands of their family member role [26]. Besides the family role, role theory proposes that individuals hold multiple roles in their lives such as friends and students [27]. Each role has its accompanying demands or expectations, and maintaining a role involves continually committing personal resources to fulfill the role behaviours. As such, work-life conflict may arise due to resource competing.

In the post-pandemic era, organizations are compelled to adapt to external pressures, leading to shifts in once-stable work environments and employment, thus significantly heightening employees’ job insecurity [28]. Facing this imminent threat, employees must deploy heightened self-control resources to ensure work continuity [24]. Consequently, the coexistence of job insecurity and regular work performance demands consumes employees’ essential resources and causes significant damage to their psyche [9], which leads to difficulties in the fulfilment of subsequent mandates.

In short, job insecurity necessitates employees to devote additional resources to fulfilling their occupational responsibilities, yet the finite of these resources impedes the smooth execution of their other life roles and giving rise to conflicts between their work and personal lives. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Employees’ job insecurity is positively related to work-life conflict.

Anxiety refers to an affective state characterized by feelings of worry, tension, apprehension, and nervousness accompanied by physiological arousal [29]. Workplace anxiety is a stimulus-bound type of anxiety, it is related to and occurring in the workplace or when thinking of the workplace [30]. Usually, anxiety is elicited in response to an unknown and ambiguous threat, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [31]. Research has found that fear and worry about contracting a new coronavirus can seriously trigger health anxiety, which in turn interferes with work and life [32], resulting in a number of negative impacts.

Due to the global deterioration of economic conditions as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, people might feel insecure about their jobs and future job prospects [32]. When employees perceive job insecurity, they believe that there are potential factors threatening their job stability and causing them to lose the jobs [21,24]. This perception of insecurity triggers employees’ worry and fear, which greatly elevate their job anxiety. According to ego depletion theory, job insecurity requires employees to exert more resources for self-control [33]. While self-control resources can be repaired through rest and recreation, anxiety keeps employees in a high-pressure work situation where they must mobilize as much self-control as possible to cope these negative feelings and emotions [33]. As a result, self-control resources are in a constant state of depletion and are difficult to restore and replenish.

The consuming of self-control resources may have destructive effect on employees’ work-life balance. Achieving work-life balance requires high-level engagement with work-related roles, which can consequently generate many positive affects through the successful transfer of positive skills, values, and emotions from work-related roles to other roles in non-work domains [26]. It is clear that job insecurity and job anxiety directly undermine the positive experience of the work role. Job anxiety can immerse employees in work stress that is difficult to get rid of and magnify problems at work. Such prevalent and persistent distress in the population can go a long way to negatively affect the work performance and job satisfaction [32]. The accumulation of anxiety causes employees to devote too much of their personal resources to work, neglecting other life roles, and ultimately creating a work-life imbalance [34].

Therefore, we propose the hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Employees’ workplace anxiety mediates the relationship between job insecurity and work-life conflict.

Perceived environmental uncertainty as moderator

Due to the unpredictable impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on our society, uncertainty has emerged as a defining characteristic in the post-pandemic era [35]. The perceived environmental uncertainty is a perceptual phenomenon, where individuals interpret the fluctuations in the environment surrounding the organization’s operations as unpredictable [36]. Despite the temporary lull in the COVID-19 pandemic, the persistent uncertainty risk continues to pervade organizations [37]. The proliferation of variant strains, lingering health concerns, and the challenges of evolving work practices such as remote working and digital offices have all escalated employees’ anxiety about the unpredictable nature of the future environment. Globally, our world is undergoing profound transformations due to trade tensions, localized conflicts, regional wars, and numerous other factors. The future’s course remains enigmatic for all humanity. Perceived environmental uncertainty implies a lack of comprehension regarding how the various components of the environment might be evolving [38]. For employees, their perception of this uncertainty is inevitably a significant factor influencing their work and life.

When they perceive the organizational environment, or a particular component of that environment, to be unpredictable, that means the employees are experiencing “state” uncertainty [38], representing their inability to forecast the probabilities of particular events or changes. When the perceived uncertainty in the external environment surges, employees anticipate it will introduce risks to the organization’s operational stability. This necessitates business organizations to be poised for change and proactive in adapting to the intricate landscape of uncertainty, which might undermine the employees’ work support systems and curtail the resources they rely on in the workplace [39].

As a result, the unpredictable nature of the environment compounds job insecurity among employees, posing the potential for increased job changes. In the post-pandemic era, coupled with the overall economic downturn, employees grapple with the anxiety and stress of potential job loss [9]. They must devote additional time and energy to work roles, while the external environment’s turmoil and disorder further distract them, leading to a significant depletion of psychological resources [30]. Work consumes a significant portion of employees’ self-control resources, leaving them with fewer resources to fulfill their roles outside the workplace, thus creating a conflict between their work and personal lives.

Hypothesis 3a: Employee’s perceived environmental uncertainty positively moderates the relationship between job insecurity and work-life conflict.

Employees’ perceived environmental uncertainty significantly amplifies job anxiety’s mediating role in the relationship in question. Previous studies show that it has positive impact on job anxiety, insecurity, and work-family imbalance [40]. High uncertainty triggers negative emotions and job anxiety among those uncertain about future work changes [39], spilling over into non-work lives, causing work-life conflicts [41]. It also intensifies job insecurity, leading to more time, energy, and resources devoted to securing employment, disrupting work-family balance [42].

Hypothesis 3b: Employee’s perceived environmental uncertainty moderates the mediating role of workplace anxiety.

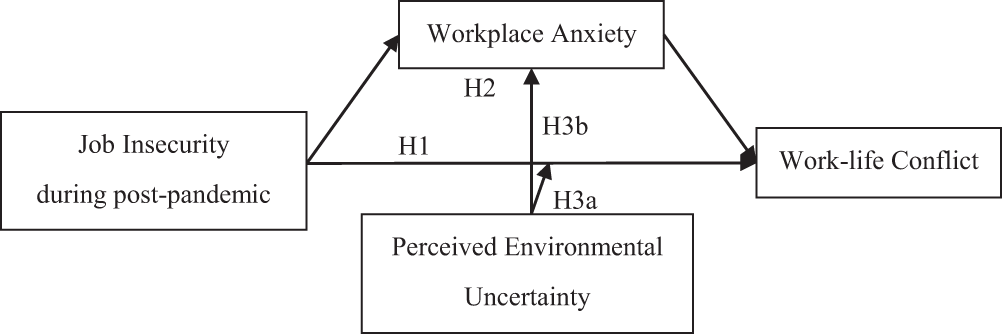

Based on the above argument, we propose a theoretical model for this study, see Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Theoretical model.

Our study used a two-wave questionnaire survey method to collect data, and participants were adults with full-time jobs. During October to December 2023, the researchers contacted MBA students and graduates from business schools to distribute questionnaires, mainly in the form of electronic questionnaires through online distribution channels (such as WeChat, QQ, email, etc.), in order to expand the scope and quantity of questionnaire collection as much as possible. This was a convenience sample selected due to easy availability. Each survey contained a simple question as an attention check (“Please choose ‘neutral’ for the following question: What would you choose?”) to filter out careless respondents. The study was approved by Institute of Psychology Ethics Committee at the Psychology Department of Ningbo University. All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

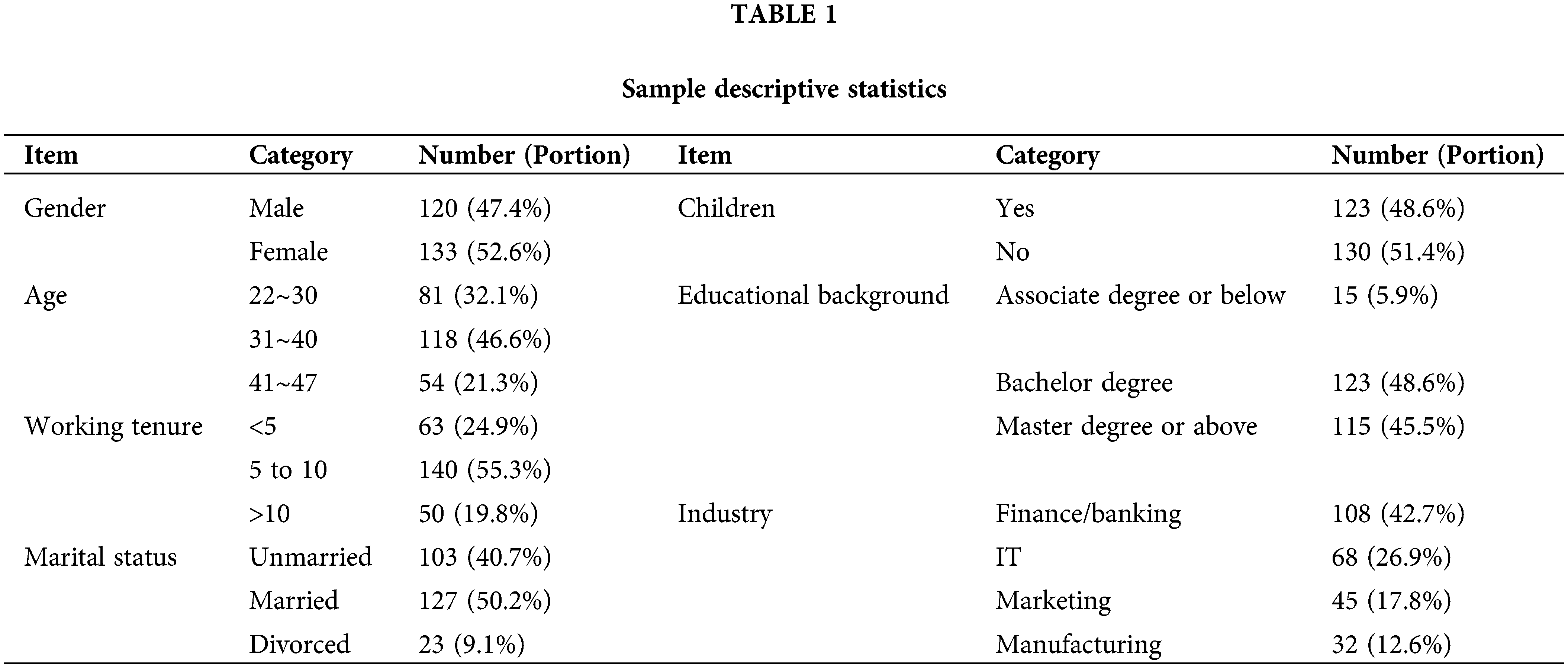

Participants were informed that the purpose of the survey was to investigate the impact of job insecurity on the work-life conflict of full-time employees in the post-pandemic context. The survey was administered with a time lag of one month, in two waves, to minimize potential common method bias. In the first wave (T1), participants reported on job insecurity and workplace anxiety and provided their demographic information. 500 questionnaires were distributed, and 401 questionnaires were returned, with a return rate of 80.2%. One month later (T2), questionnaires were distributed to the same group of participants to measure perceived uncertainty and work-life conflict. A total of 401 questionnaires were distributed, and 309 questionnaires were returned, with a return rate of 77.1%. We excluded questionnaires with the same responses for all items, those showing logical inconsistencies within their answers, and those that failed to correctly respond to the attention check questions in the questionnaire. This resulted in 253 valid responses from employees. The detailed information on the samples is shown in Table 1.

Job insecurity during post-pandemic is measured by a five-item “Job Insecurity Scale” originally developed by Mauno et al. [43], which is adopted in the recent studies by Peltokorpi et al. [44], Zhang et al. [45], and He et al. [46]. The scale was designed to reflect how employees feel about their job. Such as “Your job is likely to change in the future.” All items are self-evaluated by employees on a Likert 5-point scale (“1” to “5” range from “very disagree” to “very agree”). The measure demonstrated good internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.90), in this study (Appendix A).

Workplace anxiety is measured by a three-item sub-scale from “Workplace Well-being Scale” originally developed by Warr [47], which is adopted in the recent studies by Welsh et al. [48–50]. Respondents were instructed as follows: “Thinking of the past few weeks, how much of the time has your job made you feel each of the following?”. The items are tense, uneasy, and worried. All items are self-evaluated by employees on a Likert 5-point scale (“1” to “5” range from “almost never” to “almost always”). The measure demonstrated good internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.91), in this study (Appendix A).

Work-life conflict is measured using the five-item “Work-family Conflict Scale” adopted from Netemeyer et al. [51], because their Work-Family Conflict Scale may not adequately measure the work-life conflict experienced by individuals who do not live within a family structure that involves a spouse or children [52], recent studies of Zhou et al. [53], Bernuzzi et al. [54] have made slightly changes to the original items. This is a 5-item questionnaire that assesses how participants’ work impacts their time away from work. The response categories for each item ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (absolutely). The measure demonstrated good internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.92), in this study (Appendix A).

Perceived environmental uncertainty scale

Perceived Environmental Uncertainty is measured by the four-item “Perceived Environmental Uncertainty Scale” originally developed by Waldman et al. [55], which is adopted in the recent studies by Kim et al. [56], Cowden et al. [57], and Lian et al. [6]. Respondents were instructed as follows: “How would you characterize the external environment within which your corporation functions? In rating your environment, where relevant, please consider not only the economic but also the social, political, and technological aspects of the environment.” The response categories for each item ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (absolutely). The measure demonstrated good internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.86), in this study (Appendix A).

Job insecurity, as the independent variable, arises from employees’ subjective feelings about their work, and demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and educational background can influence their perceptions and judgments. Work-life conflict, as the dependent variable, is closely linked to employees’ non-work roles. For instance, a married woman with children in the workplace must balance multiple roles as a wife and mother, leading to greater urgency in resource needs and an increased likelihood of work-life conflicts. Earlier research has shown that parental status and gender are important aspects in the context of the work-life interface [58]. To more effectively illustrate the relationships among the research variables, integrating other relevant research achievements, our study chose age, gender, education background, marital status and parental status as control variables. Age is measured in years, and participant aging from 22 to 30 is coded as one, from 31 to 40 is coded as two, and from 41 to 47 is coded as three; gender is a dummy variable with male coded as one and zero otherwise; education background is measured with association degree or below as one, bachelor degree as two, and master degree or above as three; marital status is a variable with unmarried coded as one, married coded as two, and divorced as three; and parental status is a dummy variable with children coded as one, and zero otherwise. Two age dummies, two education background dummies, and two marital status dummies are included along with gender and parental status dummy to control for these influences.

To test the hypotheses of main effect, mediating effect, and moderating effect, we adopted the PROCESS macro (Version 4.0) in SPSS20.0 developed by Andrew F. Hayes, https://www.processmacro.org/index.html (accessed on 12 October 2021). Prior to the model estimation, all variables were mean centered to reduce the multicollinearity concern [59]. To examine the indirect effect between job insecurity and work-life conflict via workplace anxiety, PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 4) was used. Then, to test H3a (moderation) and H3b (moderated mediation) simultaneously, we utilized the PROCESS syntax in SPSS (Model 59). This choice enables an analysis of the conditional indirect effects of job insecurity on work-life conflict through workplace anxiety. In this analysis, we choose perceived environmental uncertainty values at 1 SD above mean, the mean, and 1 SD below the mean, along with an inferential test at those values and a bootstrap CI. The conditional direct effects of job insecurity on work-life conflict were also estimated for various values of perceived environmental uncertainty, along with standard errors and p-values. A threshold p-value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

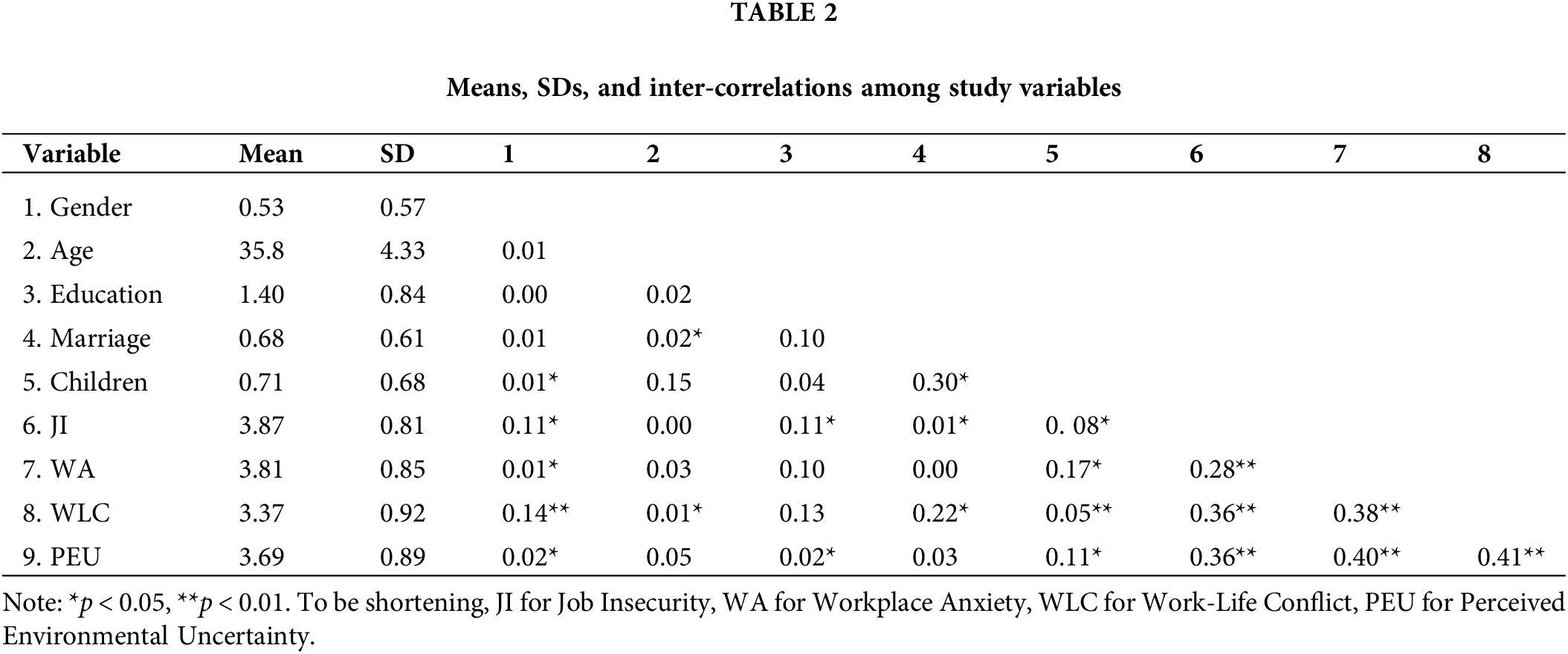

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations. Intercorrelation analysis provided us with preliminary evidence of the relationship between variables and provided support for subsequent tests. Bivariate correlations among interested variables revealed that job insecurity was positively correlated with work-life conflict (β = 0.36, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

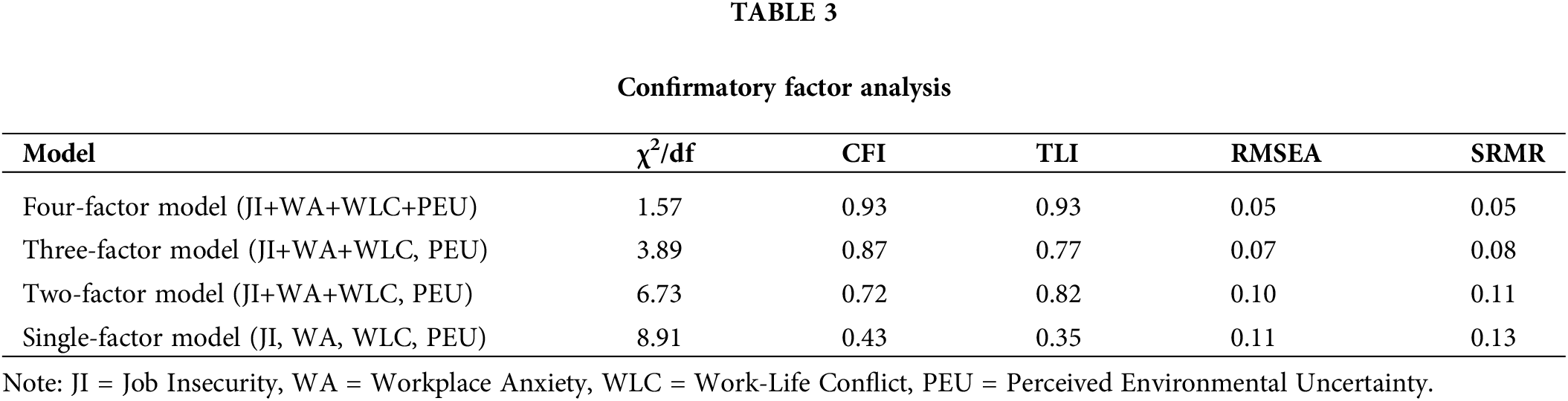

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the discriminant validity of key variables. The hypothesized four-factor model provided a better fit to the data (χ2/df = 1.57, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.05) than other factor models (see Table 3). This finding confirms that our four key variables were empirically distinct.

The results of the direct and indirect effects are presented in Table 4. In accordance with Hypothesis 1, job insecurity positively related to work-life conflict (B = 0.275, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.182, 0.367]) did not include zero. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Hypothesis 2 predicted workplace anxiety mediated the relationship of job insecurity and work-life conflict, as seen in Table 4, indirect effect (B = 0.083, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.047, 0.130]) did not include zero. Hypothesis 2 got supported.

Table 5 presents the conditional direct and indirect effects. Hypothesis 3a predicted that perceived environmental uncertainty moderated the relationship between job insecurity and work-life conflict. While the perceived environmental uncertainty is low, the direct effect (B = 0.155, p < 0.050, 95% CI [0.036, 0.247]) did not include zero. While the perceived environmental uncertainty is high, the direct effect (B = 0.273, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.127, 0.419]) did not include zero as well. The results indicated that no matter whether the perceived environmental uncertainty was low or high, the direct effect of job insecurity and work-life conflict was significant. Thus, Hypothesis 3a was not get supported.

Hypothesis 3b predicted the moderated mediation of perceived environmental uncertainty on workplace anxiety. While the perceived environmental uncertainty is low, the indirect effect (B = 0.024, 95% CI [−0.005, 0.068]) included zero. While the perceived environmental uncertainty is high, the indirect effect (B = 0.049, 95% CI [0.011, 0.114]) did not include zero. Thus, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

After systematic data analysis, the hypotheses in this study have been largely validated. Firstly, this study confirms that employees’ job insecurity leads to work-life conflict [60], extending studies focusing on the squeezing of work roles on life roles. The lasting technological and socioeconomic ramifications of COVID-19 lead to complex and changeable internal and external environments of organizations [1], causing employees’ stress, anxiety, worry, and insecurity in work to spill over into non-work time, ultimately resulting in more severe and widespread conflicts.

Secondly, as an explanatory framework, the ego depletion theory illustrates the mediating effect of work anxiety and the moderating effect of environmental uncertainty. When encountering impacts on job insecurity and uncertainty perception, people always try to maintain this crisis at a manageable level, hence requiring substantial energy and resources to coordinate, stabilize, and resolve the perceived anxiety and loss of control [8]. This depletes a large amount of self-control resources, leading to negative emotional states of anxiety and sadness, making it difficult to effectively recover from the depletion, and depriving employees of good self-control abilities during non-work time. In the long run, if employees cannot rest and recover in their lives, this will continue to impact their work, forming an irredeemable vicious cycle.

Finally, this study found that the mediating effect of work anxiety is moderated by environmental uncertainty. However, the moderating role of environmental uncertainty on the relationship between job insecurity and work-life conflict is not significant, meaning that regardless of the level of environmental uncertainty, job insecurity always significantly exacerbates work-life conflict. The reasons for this may include the following points: (1) Perceived environmental uncertainty directly influences employees’ job insecurity. External factors such as organizational changes, economic instability, market adjustments, and increasing competition, as well as internal factors such as management uncertainty and career development uncertainty within the organization, all lead to employees’ perception of environmental uncertainty. Therefore, the relationship between perceived environmental uncertainty and job insecurity may resemble interaction rather than moderation. (2) Environmental uncertainty is not always negative [6]. Research has indicated that environmental uncertainty can bring new opportunities, and the effects it generates depend on how people perceive uncertainty and take actions to deal with it [61]. Amidst changes in market environment and technological factors, new business demands and entrepreneurial opportunities may be fostered, contributing to the stimulation and cultivation of organizational dynamic capabilities [62], thereby realizing more possibilities in the future.

The theoretical contribution of this study primarily lies in exploring the work stress and emotional drain experienced by ordinary employees in the post-pandemic era. Firstly, employees’ job insecurity can lead to work-life conflicts in the post-pandemic time. The COVID-19 pandemic has emerged as a global health crisis, enveloping employees in profound uncertainty [6], severely impacting their physical and mental well-being [31]. The pandemic’s conclusion has failed to bring complete tranquility to employees, with perceptions of job uncertainty continuing to deplete their scarce mental resources [11], infringing upon their personal domains and sparking intense work-life conflicts [32]. In the post-pandemic era, the boundaries between work and non-work continue to blur, with the implementation of pandemic-era management strategies now becoming the new norm [1]. Our research further substantiates that the aftermath of COVID-19 may extend beyond mere health concerns, as the dual challenges faced in employees’ professional and personal lives represent a collective predicament for society, organizations, and individuals.

Secondly, workplace anxiety mediates the relationship between job insecurity and work-life conflicts. Job insecurity stands as a prominent work stressor [14], significantly impacts employees’ performance [63], leading to a decline in job satisfaction, grievances towards the organization, and reducing organizational identification [6]. Also, it triggers negative work-related emotional experiences [19], leaving individuals constantly anxious and preoccupied with work-related worries, further depleting their limited self-control resources. Excessive depletion of psychological resources in maintaining normal work and emotional management leads to difficulties for employees to recover from exhaustion during non-work hours, and work roles suppress the proper fulfillment of life roles. Our study expands the explanatory context of ego depletion theory.

Lastly, in terms of the mainstream influence of work on non-work time, work-family balance (conflict) has been a common research theme [26]. However, in the current social context, a large number of employees are not in family structures, and examining only the conflict between work and family roles excludes a more diverse research population [64]. This study selects work-life conflict as a research variable outside of the family, thereby confirming, in a more general sample, that job insecurity occupies and squeezes life resources through work anxiety. Under the shadow of the prolonged impact of COVID-19, there is an increasing risk of conflict between people’s lives and work.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the perception of job insecurity by employees was commonly derived from organizational restructuring, layoffs, and other actions brought about by changes in the external economic situation. However, on top of that, anxiety and worry about health and safety continue to trouble people. Although most people have now unmasked and society seems to have returned to the pre-pandemic state, employees have transitioned from long-term remote work back to the workplace, while the impact of the pandemic is far from over.

Firstly, the impact of the epidemic is beyond doubt, and there are many crises and risks threatening the development of organizational entities [32]. Change is an important measure to address challenges. In the process of necessary organizational change, it is of importance to keep full communicate with employees, explain the purpose and plan of the change, inspire employees’ confidence and enthusiasm, seek their understanding and support, and make employees recognize that organizational changes are for the well-being of all employees, enhancing their sense of security and stability.

Secondly, to foster an optimal recovery environment, swift and targeted measures must be implemented [65]. Organizational support is pivotal in relieving employee anxiety and tension, redirecting their focus and resources towards addressing uncertainties, empowering employees to overcome job insecurity and achieve positive outcomes. Furthermore, a supportive work system is essential for fostering belonging and identification among employees. It bolsters trust and motivation, encouraging them to confront post-pandemic job insecurity challenges head-on. When employees perceive organizational care, they are empowered to navigate challenges, illuminating the organization’s future path [66].

Finally, organizations need to pay attention to the emotional state of employees. Positive emotions are an important asset, and corporate organizations should actively provide psychological counseling to employees and help them manage their emotions. By constructing a scientific and reasonable workflow and arranging work content, an efficient work atmosphere is formed, allowing work tasks to be resolved during working hours, and thereby ensuring a good work-life balance. This is not only beneficial for the health and well-being of employees, but also an important source for the sustainable development of organizational human resources.

The primary limitations of our study are as follows:

Firstly, China was selected as the research context because it experienced massive changes during the pandemic. The control measures during this period drastically altered the social order, and the prolonged home confinement significantly shaped the typical post-pandemic context. However, not every country has experienced such strict measure like China. As a result, the perception of job security and environmental uncertainty varies across counties in the post-pandemic era. Findings from this study should not be directly generalized to other countries. Future studies could include samples from both China and other countries to explore the aftereffects of the pandemic on a broader scale.

Secondly, our study relied heavily on convenient sampling, with participants primarily being MBA students and business school graduates. As a result, most of our participants are predominantly employed in the finance/banking, IT and marketing sector. Significant variances in organizational settings and working conditions may exist across industries. Consequently, there are limitations in our conclusions to be generalized to different industries. Future research could gather samples from a broader spectrum of industries to validate and extend our findings.

Lastly, we employed questionnaire survey method to gather participants’ subjective views on work and personal life. Future studies might utilize more objective data collection methods. The persistent health issues associated with COVID-19 make objective and effective monitoring crucial for understanding the long-term effects of the pandemic’s aftermath.

The end of the COVID-19 epidemic does not signify the vanish of risks, and employees are still struggled with the repercussions of the post-epidemic era in both their work and personal lives. This study employs the theory of ego depletion to understand the dual challenges faced by employees in the post-epidemic era within the Chinese context. Our research indicates that in countries, like China, severely impacted by the pandemic and implementing stringent control measures, the aftereffects of the epidemic are particularly pronounced, leaving employees with a persistent sense of job insecurity, which can significantly contribute to the rise of workplace anxiety and ultimately increase of work-life conflicts. The unpredictable external environment effectively exacerbates employees’ insecurity and anxiety at work, leading to an escalation of work-family conflict. The trauma experienced by individuals in the post-pandemic era continues to persist, making the resolution and response to this a topic deserving of thorough attention.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank all the data providers, editors, and reviewers for their assistance.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Tianfei Yang and Xianyi Long: conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation. Tianfei Yang: methodology. Tianfei Yang: data curation. Tianfei Yang: software and formal analysis. Tianfei Yang: supervision and project administration. Tianfei Yang and Xianyi Long: writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by Institute of Psychology Ethics Committee at the Psychology Department of Ningbo University. All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yao X, Xu Z, Škare M, Wang X. Aftermath on COVID-19 technological and socioeconomic changes: a meta-analytic review. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2024;202:123322. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen YN, Crant JM, Wang N, Kou Y, Qin Y, Yu J, et al. When there is a will there is a way: the role of proactive personality in combating COVID-19. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(2):199–213. doi:10.1037/apl0000865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Postacute sequelae of COVID-19 at 2 years. Nat Med. 2023;29:2347–57. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02521-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Thompson RC, Simons NW, Wilkins L, Cheng E, Del Valle DM, Hoffman GE, et al. Molecular states during acute COVID-19 reveal distinct etiologies of long-term sequelae. Nat Med. 2023;29:236–46. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-02107-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Levine L, Kay A, Shapiro E. The anxiety of not knowing: diagnosis uncertainty about COVID-19. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:30678–85. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-02783-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Lian H, Li JK, Du C, Wu W, Xia Y, Lee C. Disaster or opportunity? How COVID-19-associated changes in environmental uncertainty and job insecurity relate to organizational identification and performance. J Appl Psychol. 2022;107(5):693–706. doi:10.1037/apl0001011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Clinton ME, Hewett R, Conway N, Poulter D. Lost control driving home: a dual-pathway model of self-control work demands and commuter driving. J Manag. 2022;48(4):821–50. [Google Scholar]

8. Carnevale JB, Hatak I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: implications for human resource management. J Bus Res. 2020;116:183–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Khudaykulov A, Zheng C, Obrenovic B, Godinic D, Alsharif HZH, Jakhongirov I. The fear of COVID-19 and job insecurity impact on depression and anxiety: an empirical study in China in the COVID-19 pandemic aftermath. Curr Psychol. 2024;43:8471–84. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-02883-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Huai M, Du D, Chen M, Liang J. Divided when crisis comes: how perceived self-partner disagreements over COVID-19 prevention measures relate to employee work outcomes at home. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:8666–79. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02464-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kumar P, Kumar N, Aggarwal P, Yeap JAL. Working in lockdown: the relationship between COVID-19 induced work stressors, job performance, distress, and life satisfaction. Curr Psychol. 2021;40:6308–23. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01567-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Liu X, Han C, Xia Y, Liu X. Different concerns, different choices: how does COVID-19-induced work uncertainty influence employees’ impression management? Curr Psychol. 2024;43:12508–21. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-05261-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Akkermans J, Richardson J, Kraimer M. The COVID-19 crisis as a career shock: implications for careers and vocational behavior. J Vocat Behav. 2020;119:103434. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. El Khawli E, Keller AC, Agostini M, Gützkow B, Kreienkamp J, Leander NP, et al. The rise and fall of job insecurity during a pandemic: the role of habitual coping. J Vocat Behav. 2022;139:1–13. [Google Scholar]

15. Bindl UK, Parker SK, Sonnentag S, Stride CB. Managing your feelings at work, for a reason: the role of individual motives in affect regulation for performance-related outcomes at work. J Organ Behav. 2022;43(7):1251–70. doi:10.1002/job.v43.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wehrt W, Casper A, Sonnentag S. Beyond depletion: daily self-control motivation as an explanation of self-control failure at work. J Organ Behav. 2020;41:931–47. doi:10.1002/job.v41.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sayre GM, Grandey AA, Chi NW. From cheery to “cheers”? Regulating emotions at work and alcohol consumption after work. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(6):597–618. doi:10.1037/apl0000452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jung HS, Jung YS, Yoon HH. COVID-19: the effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;92:102703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

19. Jiang L, Lavaysse ML. Cognitive and affective job insecurity: a meta-analysis. J Manage. 2018;44(6):2307–42. [Google Scholar]

20. Saura JR, Ribeiro-Soriano D, Zegarra Saldaa P. Exploring the challenges of remote work on twitter users’ sentiments: from digital technology development to a post-pandemic era. J Bus Res. 2022;142:242–54. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Griep Y, Lukic A, Kraak JM, Bohle SA, Jiang L, Elst TV, et al. The chicken or the egg: the reciprocal relationship between job insecurity and mental health complaints. J Bus Res. 2021;126(1):170–86. [Google Scholar]

22. Alcover C-M, Salgado S, Nazar G, Ramírez-Vielma R, González-Suhr C. Job insecurity, financial threat, and mental health in the COVID-19 context: the moderating role of the support network. SAGE Open. 2022;12(3). doi:10.1177/21582440221121048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Shin Y, Hur WM. When do job-insecure employees keep performing well? The buffering roles of help and prosocial motivation in the relationship between job insecurity, work engagement, and job performance. J Bus Psychol. 2021;36:659–78. doi:10.1007/s10869-020-09694-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Aguiar-Quintana T, Nguyen TH, Araujo-Cabrera Y, Sanabria-Díaz JM. Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. Int J Hosp Manag. 2021;94:102868. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Jayasingam S, Lee ST, Mohd Zain KN. Demystifying the life domain in work-life balance: a Malaysian perspective. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:1–12. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01403-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Iqbal J, Shagirbasha S, Madhan KP. Service with a sense of belonging: navigating work-family conflict and emotional irritation in the service efforts of health professionals. Int J Confl Manag. 2023;34(4):838–61. doi:10.1108/IJCMA-03-2023-0038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kaltiainen J, Hakanen JJ. Why increase in telework may have affected employee well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic? the role of work and non-work life domains. Curr Psychol. 2024;43:12169–87. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-04250-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Osman MK, Raheleh H, Tuna K, Constanţa E, Hamed R. The effects of job insecurity, emotional exhaustion, and met expectations on hotel employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: test of a serial mediation model. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023;25(2):287–307. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2022.025706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Cheng BH, McCarthy JM. Understanding the dark and bright sides of anxiety: a theory of workplace anxiety. J Appl Psychol. 2018;103:537–60. doi:10.1037/apl0000266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Guo L, Du J, Zhang J. How supervisor perceived overqualification influences exploitative leadership: the mediating role of job anxiety and the moderating role of psychological entitlement. Leadersh Org Dev J. 2024;45(6):976–91. doi:10.1108/LODJ-06-2023-0292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Arena AF, Collins D, Mackinnon A, Mobbs S, Lavender I, Harvey SB, et al. Job loss due to COVID-19: a longitudinal study of mental health, protective and risk factors. Psychol Rep. 2024. doi:10.1177/00332941241248601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Trougakos JP, Chawla N, McCarthy JM. Working in a pandemic: exploring the impact of COVID-19 health anxiety on work, family, and health outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105(11):1234–45. doi:10.1037/apl0000739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Lin W, Shao Y, Li G, Guo Y, Zhan X. The psychological implications of COVID-19 on employee job insecurity and its consequences: the mitigating role of organization adaptive practices. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(3):317–29. doi:10.1037/apl0000896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Guo Y, Wang S, Rofcanin Y, Las Heras M. A meta-analytic review of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSBs): work-family related antecedents, outcomes, and a theory-driven comparison of two mediating mechanisms. J Vocat Behav. 2024;151:103988. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2024.103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Yoon S, McClean ST, Chawla N, Kim JK, Koopman J, Rosen CC, et al. Working through an “infodemic”: the impact of COVID-19 news consumption on employee uncertainty and work behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2021;106(4):501–17. doi:10.1037/apl0000913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Afshar Jahanshahi A, Brem A. Entrepreneurs in post-sanctions Iran: innovation or imitation under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty? Asia Pac J Manag. 2020;37:531–51. doi:10.1007/s10490-018-9618-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Peerayuth C, Tipnuch P. The effectiveness of supervisor support in lessening perceived uncertainties and emotional exhaustion of university employees during the COVID-19 crisis: the constraining role of organizational intransigence. J Gen Psychol. 2021;148(4):431–50. doi:10.1080/00221309.2020.1795613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Milliken FJ. Three types of perceived uncertainty about the environment: state, effect, and response uncertainty. Acad Manage Rev. 1987;12:133–43. doi:10.2307/257999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ma C, Zhang W, Da S, Zhang H, Zhang X. Impact of environmental uncertainty on depression and anxiety among Chinese workers: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2024;17:1867–80. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S455891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Pustovit S, Miao C, Qian S. Fear and work performance: a meta-analysis and future research directions. Hum Resour Manage Rev. 2024;34(3):101018. [Google Scholar]

41. Reiche BS, Dimitrova M, Westman M, Chen S, Wurtz O, Lazarova MB, et al. Expatriate work role engagement and the work-family interface: a conditional crossover and spillover perspective. Hum Relat. 2021;76:452–82. [Google Scholar]

42. Kacmar KM, Andrews MC, Valle M, Tillman CJ, Clifton C. The interactive effects of role overload and resilience on family-work enrichment and associated outcomes. J Soc Psychol. 2020;160:688–701. doi:10.1080/00224545.2020.1735985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Mauno S, Leskinen E, Kinnunen U. Multi-wave, multi-variable models of job insecurity: applying different scales in studying the stability of job insecurity. J Organ Behav. 2001;22:919–37. doi:10.1002/job.v22:8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Peltokorpi V, Allen DG. Job embeddedness and voluntary turnover in the face of job insecurity. J Organ Behav. 2024;45(3):416–33. doi:10.1002/job.v45.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang L, Li J, Wang L, Mao M, Zhang R. How does the usage of robots in hotels affect employees’ turnover intention? A double-edged sword study. J Hosp Tour Manag. 2023;57:74–83. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.09.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. He C, Teng R, Song J. Linking employees’ challenge-hindrance appraisals toward AI to service performance: the influences of job crafting, job insecurity and AI knowledge. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2024;36(3):975–94. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-07-2022-0848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Warr P. The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. J Occup Psychol. 1990;63:193–210. doi:10.1111/joop.1990.63.issue-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Welsh DT, Outlaw R, Newton DW, Baer MD. The social aftershocks of voice: an investigation of employees’ affective and interpersonal reactions after speaking up. Acad Manage J. 2022;65(6):2034–57. doi:10.5465/amj.2019.1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhao H, Liu W. Managerial coaching and subordinates’ workplace well-being: a moderated mediation study. Hum Resour Manag J. 2020;30(2):293–311. doi:10.1111/hrmj.v30.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kloutsiniotis PV, Mihail DM, Mylonas N, Pateli A. Transformational leadership, HRM practices and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of personal stress, anxiety, and workplace loneliness. Int J Hosp Manag. 2022;102:1–14. [Google Scholar]

51. Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, Mcmurrian R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol. 1996;81(4):400–10. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Shields BL, Chen CP. Does delayed gratification come at the cost of work-life conflict and burnout? Curr Psychol. 2024;43(2):1952–64. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-04246-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Zhou Q, Li H, Li B. Employee posts on personal social media: the mediation role of work-life conflict on employee engagement. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(36):32338–54. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-04218-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Bernuzzi C, O’shea D, Setti I, Sommovigo V. Mind your language! How and when victims of email incivility from colleagues experience work-life conflict and emotional exhaustion. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(19):17267–81. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-05689-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Waldman DA, Ramirez GG, House RJ. Does Leadership Matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Acad Manag J. 2001;44(1):134–43. doi:10.2307/3069341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Kim T, Wang X, Schuh SC, Liu Z. Effects of organizational innovative climate within organizations: the roles of Managers’ proactive goal regulation and external environments. Res Policy. 2024;53(5):104993. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2024.104993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Cowden BJ, Karami M, Tang J, Ye W, Adomako S. The spectrum of perceived uncertainty and entrepreneurial orientation: impacts on effectuation. J Small Bus Manag. 2022;62:381–414. [Google Scholar]

58. Karkoulian S, Srour J, Sinan T. A gender perspective on work-life balance, perceived stress, and locus of control. J Bus Res. 2016;69(11):4918–23. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. New York: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

60. Lu L, Cooper CL, Kao SF, Zhou Y. Work insecurity and work-family conflict: the moderating role of work centrality. J Organ Behav. 2017;38(5):735–53. [Google Scholar]

61. Franczak J, Pidduck RJ, Lanivich SE, Tang J. Immersed in Coleman’s bathtub: multilevel dynamics driving new venture survival in emerging markets. Manag Decis. 2023;61(7):1857–87. doi:10.1108/MD-03-2022-0308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Singh R, Charan P, Chattopadhyay M. Effect of relational capability on dynamic capability: exploring the role of competitive intensity and environmental uncertainty. J Manag Organ. 2022;8(3):659–80. [Google Scholar]

63. Brough P, Kelling A. Job insecurity and the changing workplace: recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. J Occup Health Psychol. 2017;22(3):382–95. [Google Scholar]

64. Li A, Shaffer JA, Wang Z, Huang JL. Work-family conflict, perceived control, and health, family, and wealth: a 20-year study. J Vocat Behav. 2021;127(9):103562–19. [Google Scholar]

65. Hu X, Yan H, Casey T, Wu CH. Creating a safe haven during the crisis: how organizations can achieve deep compliance with COVID-19 safety measures in the hospitality industry. Int J Hosp Manag. 2021;92:102662. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Ma Q, Chen MH, Tang N, Yan J. The double-edged sword of job insecurity: when and why job insecurity promotes versus inhibits supervisor-rated performance. J Vocat Behav. 2022;140:103823. [Google Scholar]

Appendix A. Items on the Scales

Job Insecurity

All items are self-evaluated by employees on a Likert 5-point scale (“1” to “5” range from “very disagree” to “very agree”).

1. Your job is insecure.

2. Your job is likely to change in the future.

3. Your job is not permanent.

4. You are worried about the possibility of being fired.

5. The thought of getting fired really scares you.

Workplace Anxiety

All items are self-evaluated by employees on a Likert 5-point scale (“1” to “5” range from “almost never” to “almost always”).

Thinking of the past few weeks, how much of the time has your job made you feel each of the following?

1. Tense.

2. Uneasy.

3. Worried.

Work-Life Conflict

All items are self-evaluated by employees on a Likert 5-point scale (“1” to “5” range from “not at all” to “absolutely”).

1. The demands of my work interfere with my life away from work.

2. The amount of time my job takes up makes it difficult to fulfill life responsibilities.

3. Things I want to do off work do not get done because of the demands my job puts on me.

4. My job produces strain that makes it difficult to fulfill non-work duties.

5. Due to work-related duties, I have to make changes to my plans for off-work activities.

Perceived Environmental Uncertainty

All items are self-evaluated by employees on a Likert 5-point scale (“1” to “5” range from “not at all” to “absolutely”).

How would you characterize the external environment within which your corporation functions? In rating your environment, where relevant, please consider not only the economic but also the social, political, and technological aspects of the environment.

1. Very dynamic, changing rapidly in technical, economic, and cultural dimensions.

2. Very risky, one false step can mean the firm’s undoing.

3. Very rapidly expanding through the expansion of old markets and the emergence of new ones.

4. Very stressful, exacting, hostile, hard to keep afloat.

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools