Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Is Peer Victimization Associated with Higher Online Trolling among Adolescents? The Mediation of Hostile Attribution Bias and the Moderation of Trait Mindfulness

1 School of Psychology, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu, 610066, China

2 Center of Adolescent Growth Services, Sichuan Dazhu Middle School, Dazhou, 635100, China

3 Center of Mental Health Education, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, 510470, China

4 Sichuan Key Laboratory of Psychology and Behavior of Discipline Inspection and Supervision, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu, 610066, China

* Corresponding Author: Fang Li. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(8), 623-632. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.053926

Received 15 May 2024; Accepted 15 July 2024; Issue published 30 August 2024

Abstract

Background: In recent years, online trolling has garnered significant attention due to its detrimental effects on mental health and social well-being. The current study examined the influence of peer victimization on adolescent online trolling behavior, proposing that hostile attribution bias mediated this relationship and that trait mindfulness moderated both the direct and indirect effects. Methods: A total of 833 Chinese adolescents completed the measurements of peer victimization, hostile attribution bias, trait mindfulness, and online trolling. Moderated mediation analysis was performed to examine the relationships between these variables. Results: After controlling for gender and residential address, the study found a significant positive correlation between peer victimization and online trolling, with hostile attribution bias serving as a mediator. In addition, trait mindfulness moderated the direct relationship between peer victimization and online trolling. Specifically, the effect of peer victimization on online trolling was attenuated when adolescents had high levels of trait mindfulness. The results of the study emphasized the joint role of peer and personal factors in adolescents’ online trolling behavior and provide certain strategies for intervening in adolescents’ online trolling behavior. Conclusion: The results of the study suggest that strategies focusing on peer support and mindfulness training can have a positive impact on reducing online trolling behavior, promoting adolescents’ mental health, and their long-term development.Keywords

As social media has become an indispensable part of daily life for adolescents [1], it has also brought about a series of crises, particularly in the facilitation of cyber-aggressive behaviors [2,3]. As a typical behavior of cyber-attack, online trolling is usually manifested in posting provocative and inflammatory content or replies on social platforms to anger and disrupt others and derive pleasure from it [4,5]. It is a complex behavior with multiple motivations, forms and consequences [6]. Both online trolling and cyberbullying are considered part of cyber-aggressive behaviors [7] and share similar aggressive characteristics. However, Online trolling focuses on meaninglessly destroying the online environment [8], which is different from the targeted harm of cyberbullying. Despite extensive research on adolescent cyberbullying and other forms of cyber-aggression [9], systematic studies on adolescent online trolling remain relatively scarce. In recent years, online trolling has been increasingly attracting the attention of researchers within the field of psychiatry. Research indicated that online trolling had profound negative impacts on the mental health of victims, including anxiety and depression [5,10], and was associated with an increase in suicidal ideation and self-harming behaviors [11,12]. Taking into account that adolescents are navigating a pivotal phase in their physiological and psychological growth [13] and are in the midst of developing their cognitive faculties, emotional control, and social abilities [14], they are more sensitive to the potential harms of online trolling. Furthermore, adolescents are typically less supervised by their parents than children, and they often lack an understanding of the connection between their actions and their consequences [15]. This lack of understanding makes them more susceptible to becoming trolls [16]. Given that adolescents may be both victims and perpetrators of online trolling, it is particularly important to explore and understand the common predictors and intervention strategies for online trolling, which will not only help protect them from the negative effects of online trolling and maintain their current mental health, but also have far-reaching significance for promoting their long-term social and emotional development.

Preliminary studies have explored how individual traits such as psychopathy, self-esteem, and empathy affect online trolling behavior [15,17,18]. However, research into the role of peer influence on adolescent online trolling behavior remains limited. Peer relationships, crucial microsystem social environmental factors, significantly influence adolescent psychological development [19]. Acknowledging the significance of peer relationships during adolescence, this study uniquely focused on the impact of peer victimization on adolescent online trolling behavior. A survey of over 8000 adolescents from Hunan Province in China showed that approximately 13.7% had experienced peer victimization [20]. Studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between peer victimization experiences and adolescent cyberbullying behavior [21,22]. The anonymity of online spaces can lead victims of peer victimization to become perpetrators in cyberspace, using it to vent emotions and relieve stress [23]. Compared with previous research, this study delves into the impact of peer victimization on adolescent online trolling behavior from the perspective of peer relationships, analyzing how both peer and individual factors contribute to online trolling. We utilized the I3 model, suggesting that aggressive behavior arises from a complex interplay among three key factors: Instigation, Impellance, and Inhibition [24]. Overall, this study developed a moderated mediation framework, identifying peer victimization as the instigator, hostile attribution bias as the impeller, and trait mindfulness as the inhibitor, to analyze the mediating impact of hostile attribution bias on the relationship between peer victimization and online trolling, while also examining the moderating role of trait mindfulness.

Peer victimization and online trolling

Peer victimization encompasses various forms of harm, such as physical, verbal, and relational aggression [25], leading to significant harm and psychological distress for individuals. General Strain Theory (GST) posits that when individuals are unable to cope effectively with stress, they may externalize it in the form of aggressive behavior [26]. Harmful or negative stimuli experienced by an individual, such as peer victimization, are one of the important sources of stress leading to such strain [27]. Evidence indicated that individuals who were bullied offline were more likely to engage in cyberbullying [21]. A longitudinal study conducted in South Korea further confirmed the moderately significant association between peer victimization and cyberbullying behavior [23]. Moreover, Kowalski et al. [22] discovered that adolescents with experiences of peer victimization were more likely to become cyberbullies. Compared with cyberbullying, online trolling is more likely to involve more people in unnecessary arguments and pain due to its lower implementation cost and higher concealment. Consequently, adolescents who had suffered peer victimization may have been more likely to vent their stress by engaging in online trolling within the anonymous online space.

Hostile attribution bias as a mediator

Hostile attribution bias denotes a cognitive predisposition where individuals tend to interpret others’ actions as hostile, particularly in ambiguous or unpredictable situations [28]. According to the stress-coping theory [29], cognitive appraisal is the mediator between external stressors and externalized behavior. Peer victimization has been identified as a significant source of stress for adolescents [27]. Additionally, hostile attribution bias represents the cognitive evaluation of external cues. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the potential mediating influence of hostile attribution bias in the relationship between peer victimization among adolescents and their engagement in online trolling.

Social information processing theory posits that individuals interpret newly received information based on their past experiences, which in turn shapes their subsequent behavior [30]. Specifically, if an individual interprets ambiguous situations as hostile, this perception can lead to aggressive behavior. Guerra et al. [31] found in their study that an increase in hostile attribution bias plays a crucial role in the development of aggressive behavior. Empirical and longitudinal studies have revealed a positive correlation between elevated levels of hostile attribution bias and various forms of aggression [32–34]. Additionally, several studies have reported a significant positive relationship between the presence of hostile attribution bias and cyberbullying behavior [35,36]. Thus, we speculated that there may be a positive correlation between hostile attribution bias and online trolling. The results of a longitudinal study indicated that experiences of peer victimization can lead adolescents to construct distrustful schemas, which then influence them to interpret ambiguous situations with hostility [37]. The most recent evidence indicated a large positive correlation between peer victimization and hostile attribution bias [38], and that hostile attribution bias mediates the relationship between peer victimization and externalizing behavior [20,38].

Trait mindfulness as a moderator

Trait mindfulness is the capacity of an individual to maintain consciousness and concentration on the current experience [39]. According to the mindfulness stress buffering hypothesis [40], trait mindfulness can mitigate the perception of stressful events like peer victimization, thereby diminishing aggressive thoughts and behaviors. Specifically, mindfulness guides individuals to observe their feelings with a nonjudgmental attitude, objectively assess stress, and buffer the impact of peer victimization on hostile attribution cognition. Additionally, mindfulness fosters self-awareness, enabling individuals to recognize their responses to stress and consciously opt for more constructive coping strategies, potentially reducing the propensity for engaging in online trolling following experiences of peer victimization. The buffering effect of trait mindfulness on the impact of peer victimization on cyber-aggressive behavior and hostile attribution bias has also been empirically tested. van der Schans et al. [41] found that the decentering component of mindfulness can reduce individuals’ immersion in others’ negative behaviors, subsequently lowering hostile attributions. Adolescents with high levels of trait mindfulness tend to adopt better coping strategies when facing stressful events, which can help reduce aggressive behavior to a certain extent [42]. Therefore, we speculate that the link between experiences of peer victimization and online trolling behavior, as well as between experiences of peer victimization and hostile attribution bias may be weaker in adolescents with higher levels of trait mindfulness.

Moreover, previous research has demonstrated that even with high levels of hostile cognition, monitoring and regulating negative emotions before taking action (part of the function of mindfulness) can help reduce aggressive behavior [43,44]. Therefore, we speculate that the link between hostile attribution bias and online trolling will be weaker in adolescents with high levels of trait mindfulness.

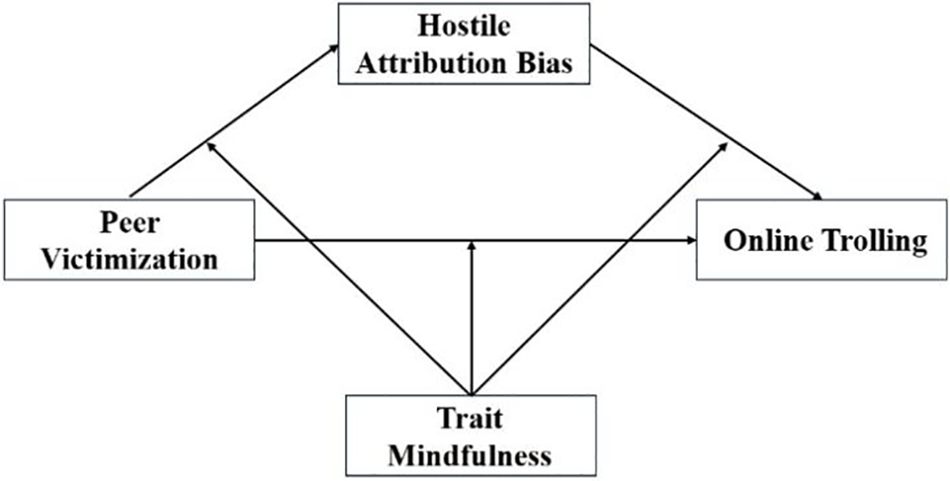

The current study extended the boundaries of the existing literature by focusing on peer relationships, a microsystemic factor in adolescent development, to explore the potential relationship between peer victimization and online trolling behavior. Additionally, we innovatively integrated peer factors with individual factors to examine how they jointly shaped online trolling behavior. By incorporating the I3 model, the current study employed a moderated mediation model (Fig. 1) that included instigator factors (peer victimization), impeller factors (hostile attribution bias), and inhibitor factors (trait mindfulness). In addition, previous research results have shown that men exhibit a higher propensity for online trolling compared to women [17,45]. Meanwhile, different residential addresses have also shown significant differences in the incidence of peer victimization and cyberbullying [46,47]. Therefore, in the current study, gender and residence were used as control variables. Specifically, we proposed three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Adolescent peer victimization is significantly positively correlated with online trolling.

Hypothesis 2: Hostile attribution bias serves as a mediator between peer victimization and online trolling. Specifically, peer victimization is positively associated with online trolling via hostile attribution bias.

Hypothesis 3: Trait mindfulness moderates both the direct and indirect paths of peer victimization and online trolling. Specifically, high levels of trait mindfulness diminish the impact of peer victimization on online trolling. Additionally, when trait mindfulness is high, the effect of peer victimization on hostile attribution bias and the effect of hostile attribution bias on online trolling are weakened.

Figure 1: Hypothesized conceptual model.

Participants included students from three schools in Sichuan Province, China. This study was derived from a large survey conducted from December 2023 to January 2024 [48]. Initially, the study sample consisted of 844 students. Before data analysis, we excluded participants who did not fully answer basic demographic questions or who did not complete more than 20% of the scales on any of the study variables (n = 11) [49]. We used the expectation-maximization algorithm (EM) to handle missing values [50]. The final valid sample included 833 students (394 girls and 439 boys, Mage = 14.56, SD = 1.34). Out of the total participants, 664 (79.7%) were urban residents, and 169 (20.3%) were from rural areas.

The data from this study were collected through paper questionnaires, administered in class groups. Teachers who had received psychological professional training randomly selected several classes for questionnaire distribution. Before the questionnaires were completed, teachers detailed to the students the precautions for filling out the questionnaires and emphasized the anonymity, confidentiality, and the right to freely withdraw from the study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan Normal University. All study procedures were followed by the ethical standards of the Sichuan Normal University (IRB number: SCNU-231204). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

The Multidimensional Peer Victimization Scale (MPVS) [51] was used in this study to assess participants’ level of peer victimization. The scale contains 16 items divided into 4 dimensions: physical victimization, social manipulation, verbal victimization, and attacks on property. Participants rated their experiences of peer victimization on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (often), with higher total scores reflecting more frequent victimization. The Cronbach’s α for the dimensions in the current study was 0.833, 0.859, 0.809, 0.804. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.919.

The Word Sentence Association Paradigm for Hostility (WSAP-Hostility) [52] was used in the current study to assess participants’ level of hostile attribution bias. Participants evaluated the similarity between 16 contextually ambiguous sentences and a hostility-related adjective using a 6-point scale (1 = not at all similar, 6 = completely similar). The mean score for each participant was used for the assessment, with higher scores indicating higher levels of hostile attribution bias in the individual. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.918.

The Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), developed by Brown et al. [39] and revised by Chen et al. [53] was used in the current study to assess participants’ levels of trait mindfulness. The scale contains 15 items on a 6-point scale (1 = almost always, 6 = almost never) to assess the level of agreement with the items. The total score for each participant was used for the assessment, with higher scores indicating higher levels of trait mindfulness in the individual. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.916.

The Global Assessment of Internet Trolling Scale (GAIT-Revised) short form, as revised by Sest et al. [17], was used in the current study to assess an individual’s propensity to engage in online trolling behavior. The Chinese version of the scale was revised by Li et al. [48]. The scale comprises 8 items rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with each participant’s total score reflecting the extent of their online trolling behavior, higher scores suggesting greater engagement. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.731.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 26.0 software. Harman’s single-factor test was employed to examine common method bias, and if the variance of the first common factor was below 50% [54], it was considered that common method bias did not cause serious interference in this study. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed in the preliminary analysis, and Pearson analysis was used for correlation analysis. All variables were standardized before conducting mediation and moderation effect analyses. A structural equation model was established using AMOS software to test for mediation and moderation effects. In the process of constructing the mediation and moderation models, hostile attribution bias, online trolling and trait mindfulness, due to their unidimensional nature, were set as manifest variables. In contrast, peer victimization was set as a latent variable, with its four dimensions serving as four indicators. p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference.

The results from Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first factor accounted for 22.25% of the variance, which is less than 50%, suggesting that common method bias did not affect the validity of the results in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

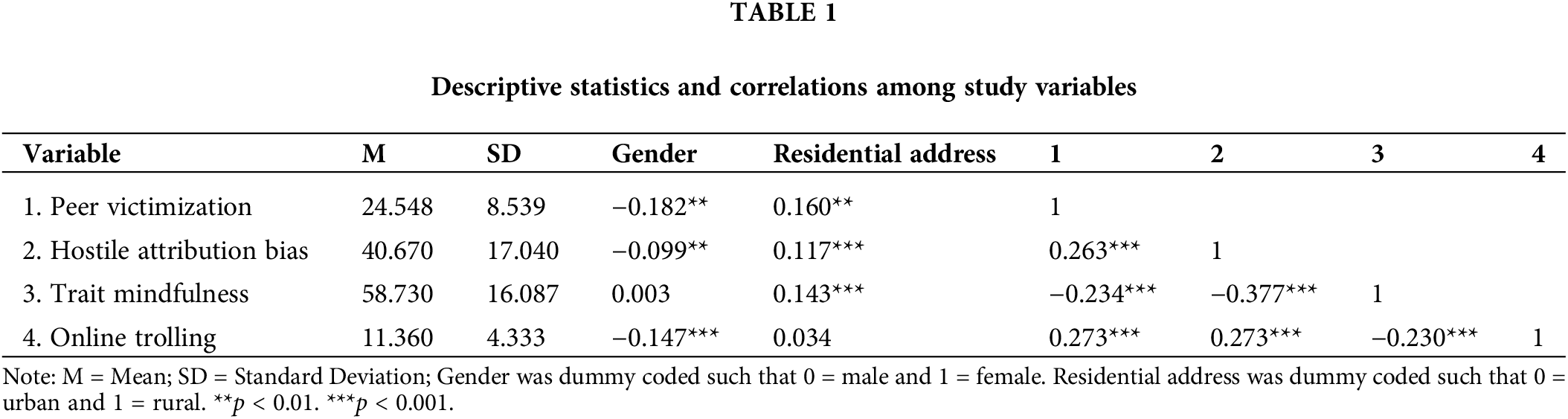

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients. The results showed that peer victimization and online trolling were significantly positively correlated (r = 0.273, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1. In addition, online trolling was positively correlated with each of the four dimensions of peer victimization: physical victimization (r = 0.186, p < 0.001), social manipulation (r = 0.236, p < 0.001), verbal victimization (r = 0.253, p < 0.001), and attacks on property (r = 0.238, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the correlation between each dimension and online trolling, so we subsequently analyzed peer victimization as one dimension. Hostile attribution bias was positively correlated with peer victimization and online trolling (r = 0.263, p < 0.001; r = 0.273, p < 0.001), but negatively correlated with trait mindfulness (r = −0.377, p < 0.001). Trait mindfulness was negatively correlated with online trolling and peer victimization (r = −0.230, p < 0.001; r = −0.234, p < 0.001). Additionally, gender and residential address were significantly correlated with the principal research variables (Table 1). Therefore, in subsequent analyses, gender and residential address were considered as covariates.

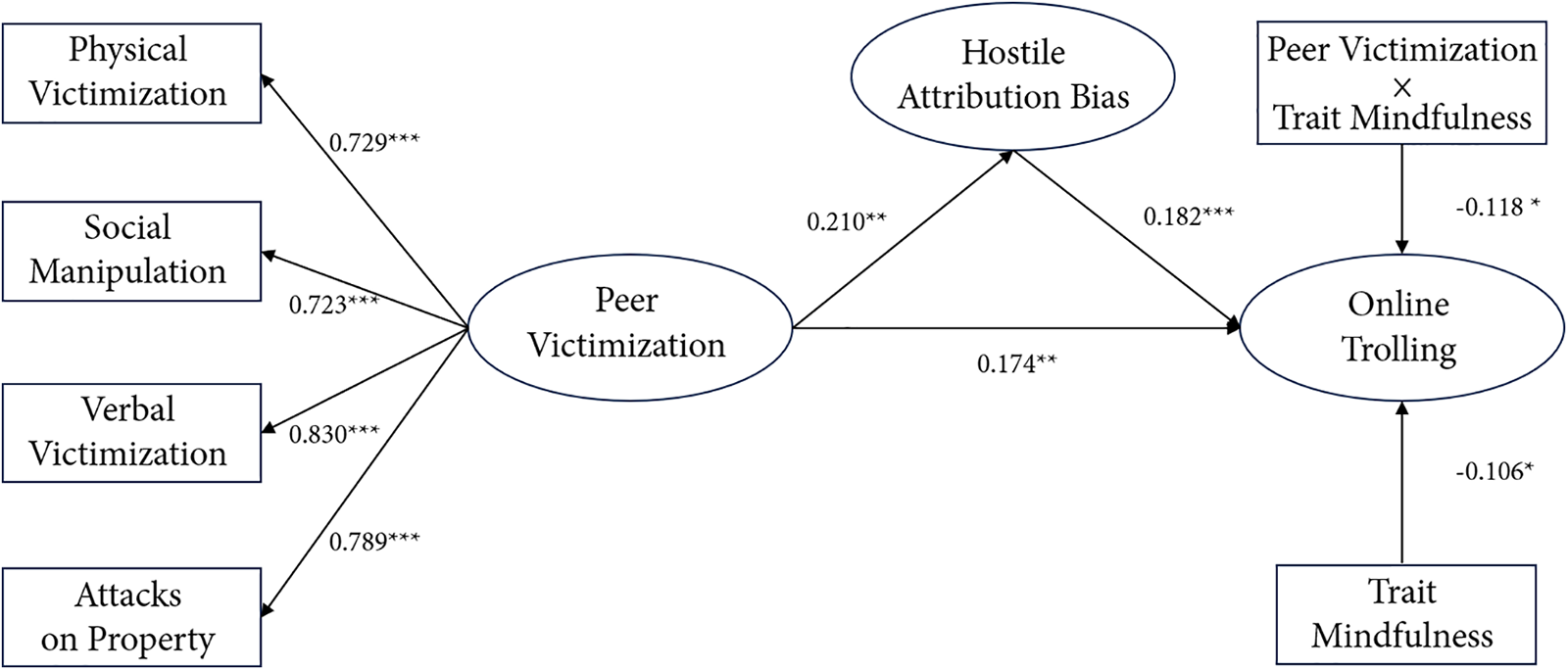

Mediation analyses were conducted with peer victimization as the independent variable, online trolling as the dependent variable, and hostile attribution bias as the mediator in the structural equation model. The outcomes indicated that the model was well-fitted, with χ2/df = 4.961, GFI = 0.977, IFI = 0.963, NFI = 0.954, CFI = 0.963, and RMSEA = 0.069. Specifically, the direct effect of peer victimization on online trolling was found to be significant (c′ = 0.207, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.112,0.306]); peer victimization had a significant predictive effect on hostile attribution bias (a = 0.314, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.233,0.398]); hostile attribution bias had a significant predictive effect on online trolling (b = 0.215, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.137,0.292]). The mediation effect value of hostile attribution bias was 0.068 (95% CI [0.040,0.103]). Since all confidence intervals did not include zero, this indicates that hostile attribution bias played a partial mediating role between peer victimization and online trolling. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

In line with the hypotheses of the current study, a latent variable structural equation model was constructed using AMOS 26.0 (see Fig. 2), and the model was tested using the moderated mediation analysis method proposed in related research [55]. The outcomes indicated that the model was well-fitted, with χ2/df = 4.511, CFI = 0.946, GFI = 0.970, IFI = 0.947, and RMSEA = 0.065.

Figure 2: Research model for structure equation model. Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

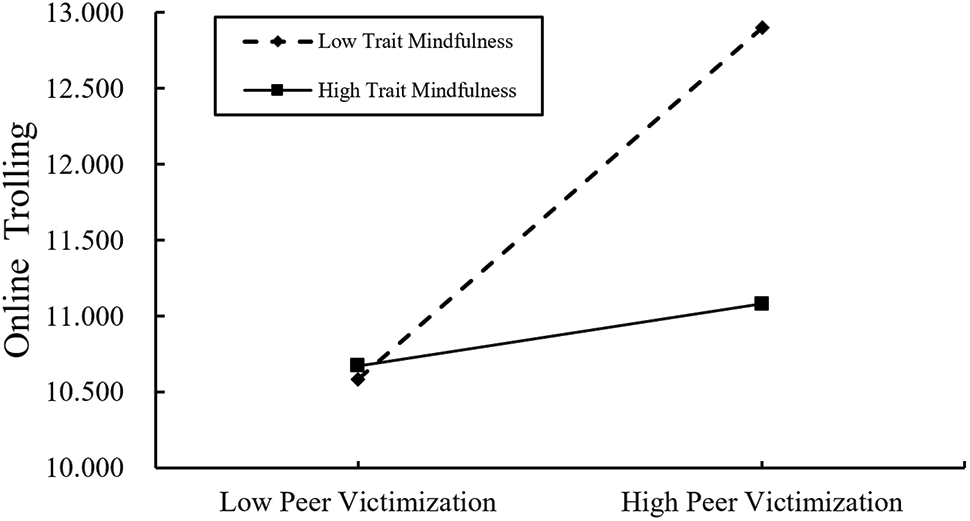

The results indicated that the interaction term between peer victimization and trait mindfulness significantly negatively predicted online trolling (β = −0.118, p = 0.015; 95% CI [−0.222, −0.022]), suggesting that trait mindfulness moderated the direct relationship between peer victimization and online trolling. The results of the simple slope analysis (see Fig. 3) showed that for adolescents with low levels of trait mindfulness, peer victimization positively predicted online trolling (bsimple = 0.136, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.094, 0.177]), while for adolescents with high levels of trait mindfulness, peer victimization had no significant predictive effect on online trolling (bsimple = 0.024, p = 0.312, 95% CI [−0.022, 0.070]). Thus, trait mindfulness attenuated the predictive effect of peer victimization on online trolling. However, the interaction term between peer victimization and trait mindfulness was not significant in predicting hostile attribution bias (β = −0.002, p = 0.840; 95% CI [−0.007, 0.006]). This suggested that trait mindfulness did not moderate the relationship between peer victimization and hostile attribution bias. In addition, the interaction term between hostile attribution bias and trait mindfulness was not significant in predicting online trolling (β = 0.001, p = 0.224; 95% CI [−0.001, 0.002]), indicating that trait mindfulness did not moderate the relationship between hostile attribution bias and online trolling. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was only partially supported.

Figure 3: Interaction between peer victimization and trait mindfulness on online trolling.

The purpose of this study was to analyze the relationship between peer victimization and online trolling behavior among Chinese adolescents, as well as the underlying psychological mechanisms. Results revealed a positive correlation between adolescents’ experiences of peer victimization and their engagement in online trolling behavior, with hostile attribution bias serving as a substantial mediating factor. Furthermore, trait mindfulness was found to have a significant moderating effect on the direct relationship between peer victimization and online trolling. Also, our study found that gender was significantly negatively correlated with peer victimization, hostile attribution bias, and online trolling, which is consistent with previous research results [17,45]. However, unlike previous research results [46,47], no significant association was found between residential address and online trolling behavior. The reason may be that due to the popularity of the Internet, residents in different regions can access online content with similar convenience and participate in online discussions with a lower threshold.

The relation between peer victimization and online trolling

Aligned with our proposed hypothesis, the findings from our research demonstrated a significant positive association between the degree of peer victimization experienced by adolescents and the occurrence of their online trolling behaviors. Based on this association, we speculated that faced with the psychological trauma and stress caused by peer victimization, adolescents may lack effective coping and relief strategies and thus tend to seek emotional catharsis through online trolling behavior. In accordance with the General Strain Theory, our findings verify the significant positive association between the experience of peer victimization and online trolling among adolescents [26]. The frustration-aggression hypothesis further explains this correlation [56]. Peer victimization, as a typical interpersonal frustration experience, not only easily causes individuals to have a strong sense of frustration and threat, but also may stimulate an aggressive behavior pattern as a coping mechanism. Our results also support the results of previous studies that peer victimization experience may be an important antecedent factor of cyber-aggressive behavior [57]. Adolescents who have experienced peer victimization often avoid direct confrontation for fear of more intense retaliation, but in the absence of appropriate avenues for venting stress, they may be inclined to engage in aggressive acts through the anonymous online environment. Furthermore, compared to other forms of cyber aggression, online trolling is less costly in terms of time investment and potential punishment [58,59], making it more attractive to adolescents with limited time on electronic devices. Therefore, online trolling may become a preferred pattern of cyber-aggressive behavior among adolescents who have been subjected to peer victimization.

The mediating effect of hostile attribution bias

The findings indicated that hostile attribution bias mediated the relationship between adolescent peer victimization experiences and online trolling, supporting Hypothesis 2. Based on this result, we speculated that increased experiences of peer victimization among adolescents would be associated with increased levels of online trolling through hostile attribution bias. This result further validates the General Strain Theory [29]. This aligns with prior research findings, which show that experiences of peer victimization are linked to the development of hostile attribution bias in individuals. Furthermore, when hostile attributional bias is high, it is associated with increased aggressive behavior [60]. A possible interpretation is that the experience of peer victimization could lead to changes in the psychological structure of adolescents, making them more inclined to interpret others’ actions with hostile attribution [61]. This hostile cognition might form the psychological basis for online trolling behavior. Additionally, adolescents who have experienced peer victimization may become more sensitive, tending to amplify perceived threats and hurtful evaluations online or in their environment, potentially associating with an increase in aggressive behaviors. Furthermore, hostile attribution bias can trigger angry rumination, depleting the cognitive resources needed to inhibit aggressive behavior [62]. In the anonymous online environment, adolescents who have experienced peer victimization may redirect their anger and hostility towards the online world as a means of venting, seeking psychological compensation, and thus are increasingly inclined to participate in online trolling behavior, which requires lower costs in terms of time and effort [63].

The moderating effect of trait mindfulness

The analysis results of this study confirmed that trait mindfulness moderated the direct link between peer victimization and online trolling behavior, which is consistent with the mindfulness stress buffering hypothesis [39]. The results indicated that trait mindfulness, as a psychological protective factor, can effectively mitigate the online trolling behavior that adolescents may exhibit as a result of experiences with peer victimization, in line with previous research findings [42,64]. Specifically, adolescents with higher levels of trait mindfulness are able to process external stimuli more objectively and consciously disengage from automatic behavioral response patterns [65]. This ability makes them more inclined to choose constructive coping strategies, thereby reducing the negative impact brought about by peer victimization [42] and decreasing the likelihood of engaging in online trolling behavior. It is worth noting that the interaction between trait mindfulness and peer victimization had a modest effect size in predicting online trolling behavior. This result is close to the effect size of trait mindfulness on reducing aggressive behavior in previous studies [42,44,65,66], indicating that trait mindfulness may play a role in alleviating online trolling caused by peer victimization, but its influence may also be affected by other variables.

However, the study’s findings did not reveal that trait mindfulness could significantly alleviate the link between peer victimization and hostile attribution bias. This may be due to the hostile attribution cognition formed by adolescents after experiencing peer victimization, which may to some extent be a self-protective adaptive mechanism [38]. Under this self-protective cognitive mechanism, the cognitive intervention provided by trait mindfulness may face certain limitations, as adolescents might be more inclined to maintain their existing hostile attribution biases as a defensive response to ambiguous social cues. Our results showed that trait mindfulness doesn’t moderate the link between hostile attribution bias and online trolling, possibly because this connection is too strong for trait mindfulness to influence. In addition, the core of trait mindfulness is to pay attention to the current experience in a non-critical attitude, which may strengthen the recognition of this cognitive pattern when individuals have already formed a hostile attribution bias.

This study acknowledges several limitations that require further exploration. First, the study sample was exclusively from schools in Sichuan Province, China, which may hinder the generalization of the findings to other regions. Second, the data in the current study were based entirely on self-reports, and due to the particular nature of the research variables, there may be a social desirability bias that could lead to biased reporting by adolescents. In addition, hostile cognition does not always directly lead to an increase in aggressive behavior. On the contrary, aggression may cause individuals to view the outside world with hostility, and negative feedback from the outside world may further consolidate this hostile cognition. Therefore, future research should consider using more rigorous experimental designs or longitudinal research methods to more fully reveal the causal link between hostile cognition and aggressive behavior. Finally, the study found that the buffering effect of trait mindfulness between peer victimization and hostile attribution bias was limited, suggesting that there may be other moderating variables that were not accounted for. For example, an empirical study by Shu et al. [67] indicated that self-perspective may weaken the association between peer victimization and aggressive cognition, suggesting that future research should consider including other potential moderating factors, such as self-perspective, to more comprehensively understand the psychological mechanisms and behavioral patterns of adolescents.

Despite certain limitations of the current study, the findings provide different perspectives for understanding and addressing adolescent online misbehavior and offer suggestions for coping strategies. Firstly, online misbehavior is closely related to the peer victimization experienced by adolescents and its impact on cognitive structure and mental health. Previous research has emphasized the severe mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, that can result from prolonged experiences of peer victimization [68]. This indicates that the dangerous consequences of peer victimization are not only a social issue but also a clinical concern that requires attention from psychiatry. Similarly, the relationship between online trolling behavior and psychiatry should not be overlooked, as trolling can lead to or exacerbate mental health problems. Therefore, schools and parents should strengthen positive interventions in adolescent peer relationships by fostering a supportive and inclusive school environment [69] to reduce the occurrence of school bullying and other forms of peer victimization. Secondly, the results of this study revealed the potential role of trait mindfulness in mitigating the relationship between peer victimization and online trolling behavior. Thus, it is recommended that trait mindfulness intervention measures be incorporated into school educational programs to reduce online trolling among adolescents. In summary, the current study not only enhances the understanding of the factors influencing adolescent online trolling behavior but also provides a scientific basis for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. Future research can further explore and verify the implementation effects of these recommendations based on the current study, to promote the comprehensive healthy development of adolescents.

Findings from this study have detailed the link between adolescent peer victimization experiences and online trolling. Utilizing a moderated mediation model, the research confirmed that peer victimization significantly predicted online trolling, with hostile attribution bias serving as a mediator. This indicated that adolescents who were subjected to peer victimization were more inclined to interpret ambiguous social signals as hostile, thereby predisposing them to engage in online trolling behavior. Furthermore, the study identified trait mindfulness as a key moderator with a protective role, potentially diminishing the incidence of online trolling. This implies that interventions fostering trait mindfulness could provide a buffering effect against the negative repercussions of peer victimization.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to all the participants for their involvement in our study.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Sichuan Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Foundation Project (General Project) titled ‘Research on the Influence Mechanism and Intervention of Mindfulness on Online Trolling among Adolescents’ (Grant Number: SCJJ23ND227).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Fang Li, Yuedong Qiu and Biyun Wu; data collection: Jie Zhou; analysis and interpretation of results: Yuedong Qiu, Qi Sun, Ni Jiang and Wenyu Zeng; draft manuscript preparation: Yuedong Qiu, Fang Li, Qi Sun, Jie Zhou, Ni Jiang, Wenyu Zeng and Biyun Wu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data is available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan Normal University. All study procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Sichuan Normal University (IRB number: SCNU-231204). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Odgers C. Smartphones are bad for some teens, not all. Nature. 2018;554(7693):432–4. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-02109-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Park MA, Golden KJ, Vizcaino-Vickers S, Jidong DE, Raj S. Sociocultural values, attitudes and risk factors associated with adolescent cyberbullying in East Asia: a systematic review. Cyberpsychology. 2021;15(1):1–19. doi:10.5817/CP2021-1-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Peterson J, Densley J. Cyber violence: what do we know and where do we go from here? Aggress Violent Behav. 2017;34:193–200. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Buckels EE, Jones DN, Paulhus DL. Behavioral confirmation of everyday sadism. Psychol Sci. 2013;24(11):2201–9. doi:10.1177/0956797613490749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. March E, Steele G. High esteem and hurting others online: trait sadism moderates the relationship between self-esteem and internet trolling. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2020;23(7):441–6. doi:10.1089/cyber.2019.0652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Cook C, Schaafsma J, Antheunis M. Under the bridge: an in-depth examination of online trolling in the gaming context. New Media Soc. 2018;20(9):3323–40. doi:10.1177/1461444817748578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. March E, Marrington J. A qualitative analysis of internet trolling. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2019;22(3):192–7. doi:10.1089/cyber.2018.0210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Buckels EE, Trapnell PD, Paulhus DL. Trolls just want to have fun. Pers Individ Dif. 2014;67:97–102. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhu C, Huang S, Evans R, Zhang W. Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: a comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Front Public Health. 2021;9:634909. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.634909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Thacker S, Griffiths MD. An exploratory study of trolling in online video gaming. Int J Cyber Behav Psychol Learn. 2012;2(4):17–33. doi:10.4018/IJCBPL. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(3):206–21. doi:10.1080/13811118.2010.494133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Bauman S, Toomey RB, Walker JL. Associations among bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide in high school students. J Adolesc. 2013;36:341–50. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Viner R, Christies D. ABC of adolescence: adolescent development. Br Med J. 2005;330(7486):301–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7486.301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Dahl RE. Adolescent brain development: a period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021(1):1–22. doi:10.1196/annals.1308.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Marrington JZ, March E, Murray S, Jeffries C, Machin T, March S. An exploration of trolling behaviours in Australian adolescents: an online survey. PLoS One. 2023;18(4):e0284378. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0284378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Griffiths MD. Adolescent trolling in online environments: a brief overview. Educ Health. 2014;32(3):85–7. [Google Scholar]

17. Sest N, March E. Constructing the cyber-troll: psychopathy, sadism, and empathy. Pers Individ Dif. 2017;119:69–72. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Türk Kurtça T, Demirci I. Psychopathy, impulsivity, and internet trolling: role of aggressive humour. Behav Inf Technol. 2023;42(15):2560–71. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2022.2133635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rivers AS, Russon J, Winston-Lindeboom P, Ruan-Iu L, Diamond G. Family and peer relationships in a residential youth sample: exploring unique, non-linear, and interactive associations with depressive symptoms and suicide risk. J Youth Adolesc. 2022;51(6):1062–73. doi:10.1007/s10964-021-01524-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Liu XQ, Yang MS, Peng C, Xie QH, Liu QW, Wu F. Anxiety emotion and depressive mood of middle school students with different roles in school bullying. Chin Ment Health J. 2021;35(6):475–81. [Google Scholar]

21. Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Online aggressor/targets, aggressors, and targets: a comparison of associated youth characteristics. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(7):1308–16. doi:10.1111/jcpp.2004.45.issue-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, Lattanner MR. Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(4):1073–137. doi:10.1037/a0035618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Jang H, Song J, Kim R. Does the offline bully-victimization influence cyberbullying behavior among youths? Application of general strain theory. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;31:85–93. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Finkel EJ. The I3 model: metatheory, theory, and evidence. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2014;49:1–104. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800052-6.00001-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hawker DS, Boulton MJ. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(4):441–55. doi:10.1111/jcpp.2000.41.issue-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Agnew R. Foundation for a general theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:47–87. doi:10.1111/crim.1992.30.issue-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Taylor KA, Sullivan TN, Kliewer W. A longitudinal path analysis of peer victimization, threat appraisals to the self, and aggression, anxiety, and depression among urban African American adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(2):178–89. doi:10.1007/s10964-012-9821-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Dodge KA. Translational science in action: hostile attributional style and the development of aggressive behavior problems. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(3):791–814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

29. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

30. Zhu W, Chen Y, Xia LX. Childhood maltreatment and aggression: the mediating roles of hostile attribution bias and anger rumination. Pers Individ Dif. 2020;162:110007. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Guerra NG, Huesmann LR. A cognitive-ecological model of aggression. Une Theorie Cognitivo-Ecologique Du Comportement Agressif. 2004;17(2):177–203. [Google Scholar]

32. Godleski SA, Ostrov JM. Relational aggression and hostile attribution biases: testing multiple statistical methods and models. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(4):447–58. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9391-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Quan F, Yang R, Zhu W, Wang Y, Gong X, Chen Y, et al. The relationship between hostile attribution bias and aggression and the mediating effect of anger rumination. Pers Individ Dif. 2019;139:228–34. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Martinelli A, Ackermann K, Bernhard A, Freitag CM, Schwenck C. Hostile attribution bias and aggression in children and adolescents: a systematic literature review on the influence of aggression subtype and gender. Aggress Violent Behav. 2018;39:25–32. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2018.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wei H, Liu M. Loving your parents and treating others well: the effect of filial piety on cyberbullying perpetration and its functional mechanism among Chinese graduate students. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(11–12):NP8670–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Yoo G, Park JH. Influence of hostile attribution bias on cyberbullying perpetration in middle school students and the multiple additive moderating effect of justice sensitivity. Korean J Child Stud. 2019;40(4):79–93. doi:10.5723/kjcs.2019.40.4.79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Li X, Chen L, Pan B, Zhang W. A cross-lagged analysis of associations between peer victimization and hostile attribution Bias. In: The 23rd National Psychology Academic Conference; 2021 Oct 29–31; Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China. [Google Scholar]

38. Zhao XY, Zheng SJ. The effect of peer victimization on adolescents’ revenge: the roles of hostility attribution bias and rumination tendency. Front Psychol. 2024;14:1255880. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Creswell JD, Lindsay EK. How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23:401–7. doi:10.1177/0963721414547415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. van der Schans KL, Karremans JC, Holland RW. Mindful social inferences: decentering decreases hostile attributions. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2019;50(5):1073–87. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhou J, Wang R, Bi T, Gong X. Peer victimization and aggressive behaviors among adolescents: a moderated mediation model of cognitive impulsivity and dispositional mindfulness. Curr Psychol. 2024;43:17406–15. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-05700-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Orobio de Castro B, Bosch JD, Veerman JW, Koops W. The effects of emotion regulation, attribution, and delay prompts on aggressive boys’ social problem solving. Cognit Ther Res. 2003;27:153–66. doi:10.1023/A:1023557125265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Liang LH, Brown DJ, Ferris DL, Hanig S, Lian H, Keeping LM. The dimensions and mechanisms of mindfulness in regulating aggressive behaviors. J Appl Psychol. 2018;103(3):281. doi:10.1037/apl0000283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Liu M, Wu B, Li F, Wang X, Geng F. Does mindfulness reduce trolling? The relationship between trait mindfulness and online trolling: the mediating role of anger rumination and the moderating role of online disinhibition. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Ómez P, Harris SK, Barreiro C, Isorna M, Rial A. Profiles of Internet use and parental involvement, and rates of online risks and problematic Internet use among Spanish adolescents. Comput Human Behav. 2017;75:826–33. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Cabrera MC, Larrañaga E, Yubero S. Bullying/cyberbullying in secondary education: a comparison between secondary schools in rural and urban contexts. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2022;39:1–15. doi:10.1007/s10560-022-00882-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Li F, Tang X, Ge X, Yu MN, Wang SQ, Wu BY. Is mindfulness associated with lower online trolling among adolescents? Mediating effects of self-esteem and depression and moderating effect of dark personality traits. J Psychol Afr. 2024;34(3). [Google Scholar]

49. You X, Yang J, Qin C, Liu H. Missing data analysis in cognitive diagnostic models: random forest threshold imputation method. Acta Psychol Sin. 2023;55(7):1192–206. [Google Scholar]

50. Song Z, Guo L, Zheng T. Comparison of missing data handling methods in cognitive diagnosis: zero replacement, multiple imputation and maximum likelihood estimation. Acta Psychol Sin. 2022;54(4):426–44. [Google Scholar]

51. Mynard H, Joseph S. Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggress Behav. 2000;26(2):169–78. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1098-2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Dillon KH, Allan NP, Cougle JR, Fincham FD. Measuring hostile interpretation bias: the WSAP-Hostility scale. Assessment. 2016;23(6):707–19. doi:10.1177/1073191115599052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Chen SY, Cui H, Zhou RL, Jia YY. Revision of mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Chin J Clin Psychol. 2012;20(2):148–51 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

54. Kock F, Berbekova A, Assaf AG. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: detection, prevention and control. Tour Manag. 2021;86:104330. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wen Z, Ye B. Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: competitors or backups? Acta Psychol Sin. 2014;46(5):714–26. [Google Scholar]

56. Dollard J, Doob L, Miller N, Mowrer O, Sears R. Frustration and aggression. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1939. [Google Scholar]

57. Zhang MC, Wang LX, Dou K, Liang Y. Why victimized by peer promotes cyberbullying in college students? Testing a moderated mediation model in a three-wave longitudinal study. Curr Psychol. 2021;42:7114–24. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02047-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Barlett CP. Anonymously hurting others online: the effect of anonymity on cyberbullying frequency. Psychol Pop Media Cult. 2015;4(2):70–9. doi:10.1037/a0034335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Wright MF. The relationship between young adults’ beliefs about anonymity and subsequent cyber aggression. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16(12):858–62. doi:10.1089/cyber.2013.0009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. DeWall CN, Twenge JM, Gitter SA, Baumeister RF. It’s the thought that counts: the role of hostile cognition in shaping aggressive responses to social exclusion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;96(1):45. doi:10.1037/a0013196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Yao Z, Enright R. Developmental cascades of hostile attribution bias, aggressive behavior, and peer victimization in preadolescence. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2022;31(1):102–20. doi:10.1080/10926771.2021.1960455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Wilkowski BM, Robinson MD. The cognitive basis of trait anger and reactive aggression: an integrative analysis. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2008;12(1):3–21. doi:10.1177/1088868307309874. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Fang X, Zhang K, Chen J, Chen M, Wang Y, Zhong J. The effects of covert narcissism on chinese college students cyberbullying: the mediation of hostile attribution bias and the moderation of self-control. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:2353–66. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S416902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Gillions A, Cheang R, Duarte R. The effect of mindfulness practice on aggression and violence levels in adults: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019;48:104–15. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2019.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Gu H, Fang L, Yang C. Peer victimization and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: the mediating role of alienation and moderating role of mindfulness. J Interpers Viol. 2023;38(3–4):3864–82. [Google Scholar]

66. Zhou ZK, Liu QQ, Niu GF, Sun XJ, Fan CY. Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: a moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Pers Individ Dif. 2017;104:137–42. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Shu Y, Luo Z. Peer victimization and reactive aggression in junior high-school students: a moderated mediation model of retaliatory normative beliefs and self-perspective. Aggress Behav. 2021;47(5):583–92. doi:10.1002/ab.v47.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Quinlan EB, Barker ED, Luo Q, Banaschewski T, Bokde AL, Bromberg U, et al. Peer victimization and its impact on adolescent brain development and psychopathology. Mol Psychiat. 2020;25(11):3066–76. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0297-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Esposito C, Bacchini D, Affuso G. Adolescent non-suicidal selfinjury and its relationships with school bullying and peer rejection. Psychiat Res. 2019;274:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools