Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Relationship between Overparenting and Adolescent Anxiety: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Avoidance

1 Educational Development Research Center of Southern Xinjiang, Kashi University, Kashi, 844008, China

2 School of Educational Science, Kashi University, Kashi, 844008, China

* Corresponding Authors: Peng Yu. Email: ; Yixin Hu. Email:

# Dawei Wang and Ranran Wang share co-first author

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(8), 643-650. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.052885

Received 18 April 2024; Accepted 08 July 2024; Issue published 30 August 2024

Abstract

Background: Adolescent anxiety has a significant impact on physical and mental health, and overparenting is recognized as one of the major factors affecting adolescent anxiety. The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety, while also examining the mediating role of cognitive avoidance. Methods: Data were collected through a cross-sectional survey with 1931 valid responses using the Overparenting Scale, the Cognitive Avoidance Scale, and the Anxiety Self-Rating Scale. A structural equation modelling approach was used to test the mediating role of cognitive avoidance between overparenting and adolescent anxiety and to reveal the underlying mechanisms. The significance of the mediating effect was assessed based on maximum likelihood estimation. Differences in the mediating role of cognitive avoidance in the male and female samples were comparatively analyzed in the mediation effect analysis. Results: The study’s findings reveal a significant positive correlation between overparenting and adolescent anxiety (p < 0.01), between overparenting and cognitive avoidance (p < 0.01), and between cognitive avoidance and adolescent anxiety (p < 0.01). Cognitive avoidance mediated the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety. Overparenting can not only directly predict adolescent anxiety but also indirectly predict it through the mediating role of cognitive avoidance. Conclusion: This study validates the direct effect of overparenting on adolescent anxiety and reveals the mechanism of cognitive avoidance as a mediator.Keywords

Anxiety generally refers to the physical, emotional, and behavioral responses characterized by tension, unease, worry, and other negative reactions of individuals towards potentially threatening situations [1]. It is an important issue affecting the physical and mental health of adolescents, as long-term negative emotions can impact all aspects of their lives, such as reducing level of physical activity and affecting sleep quality. At the same time, it also affects the quality of life and sense of well-being [2], such as social communication ability and academic performance decline [3]. Adolescence is a unique and formative time where physical, emotional and social changes can make adolescents vulnerable to mental health problems [4]. According to the Chinese Youth Development Report, approximately 30 million children and adolescents under the age of 17 in China are troubled by various emotional disorders and behavioral problems [5]. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the causes of adolescent anxiety actively to improve and prevent adolescent anxiety.

Among the factors influencing adolescent anxiety, family factors have received considerable attention from numerous researchers [6]. Overparenting refers to a non-adaptive parenting style in which parents excessively involve themselves in their children’s lives by providing excessive unnecessary assistance, excessive advice, and risk aversion [7]. Overparenting has been called “helicopter parenting” and depicts parents hovering over their children like helicopters, ready to swoop in and solve a host of problems at will [8]. The core feature of overparenting is “excessiveness,” as parents excessively involve themselves in their children’s lives and have too much control over their children [9,10], e.g., constantly monitoring their children’s whereabouts and speaking on behalf of their children to teachers, etc. Previous studies have shown that overparenting parents often act to fulfill their own needs rather than the needs of their children, which is often associated with negative outcomes [11]. For example, a substantial body of research has found that overparenting is associated with poorer psychological adjustment in children, leading to anxiety, distress, and narcissism [12–15].

Approach and avoidance are two fundamental aspects of individual motivation that will guide individual behavior. Approach-oriented motivation tends to lead individuals toward positive directions, while avoidance-oriented motivation directs behavior toward negative directions and is associated with adverse health outcomes, considered maladaptive [16]. Cognitive avoidance refers to the avoidance-type strategies individuals employ to evade negative emotions induced by intrusive thoughts [17] and is a significant concept in cognitive-behavioral model. Cognitive avoidance can be explained from two perspectives: one is an effortful strategy to suppress unnecessary thoughts, and the other is an automatic process to avoid threatening mental images [18]. Previous research has identified cognitive avoidance as a significant cognitive factor that influences the mental health of adolescents, and cognitive avoidance is one of the factors that contribute to many psychological disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder [19]. The cognitive-avoidance model suggests that suppression is the cause of the problem. When adolescents receive excessive control from their parents, they suppress unwanted thoughts, emotions, or feelings, and when suppression fails, they habitually seek more suppression methods, leading to cognitive avoidance and subsequently contributing to adolescent anxiety.

The relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety

Family factors play a significant role in adolescent anxiety. According to Ecological Systems Theory (EST), family serves as the microsystem of adolescent development and parenting styles have a direct impact on adolescent anxiety [20]. Family systems theory suggests that the family should cater for the changing needs of its members, especially parental involvement. The family is the most basic social unit, and parenting styles may have a great impact on the mental behaviour of children and adolescents, as well as in adulthood [21]. It has been shown that overparenting is a predictor of adolescent emotion regulation problems [22], which can further trigger emotional disorders. One study also suggests that overparenting affects children’s anxiety levels [23].

Attachment theory suggests that early child and adolescent development and parent-child relationships shape their perceptions and expectations of interpersonal relationships, influencing the development of individuals in terms of their behavioural styles, social cognition, etc., and helping to explain individual dispositions and dispositions in the development of interpersonal relationships [24]. Attachment theory can explain the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety, adolescents form parent-child attachment through long-term interaction with their parents [25], and parent-child attachment can also have a significant impact on adolescent psychological adaptation [9]. According to attachment theory, children need a secure base to explore the external world [26]. However, parental overparenting may hinder children’s gradual development of independence, leading to anxious attachment characterized by immaturity, anxiety, and depression [27]. Indeed, evidence suggests that higher levels of overparenting are associated with higher levels of adolescent depression and anxiety [28,29].

Furthermore, according to Self-Determination Theory, individuals have an intrinsic motivation to achieve growth and integration, which entails a spontaneous inclination to explore the environment and engage in activities that satisfy intrinsic needs; hindrances to this process are detrimental to adolescent well-being [30,31]. Parental overparenting may convey a message to children that the world is dangerous, exacerbating children’s fear of the external environment, limiting the realization of children’s potential, and affecting the development of children’s confidence and skills in coping with challenges [32]. Adolescence is a crucial period for self-integration. However, overparenting can interfere with children’s inner world, increasing their vulnerability [33], making them more dependent on their parents, increasing the risk of maladaptation, and making them prone to emotional disturbances such as anxiety and depression [34]. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 of this study posits that overparenting will positively predict adolescent anxiety.

The mediating role of cognitive avoidance

Cognitive avoidance refers to strategies individuals use to prevent experiencing negative emotions caused by intrusive thoughts [17,35], such as thought suppression, attentional shifting, and thought substitution, which can also be understood as control over intrusive thoughts [36].

The relationship between overparenting and cognitive avoidance

The developmental theory of anxiety emphasizes the significant impact of parental control [32]. Specifically, this type of control is detrimental to children’s development of competence and sense of control, instead reinforcing their avoidance attitudes towards challenges [37]. The model of interactions between environmental systems and personal systems indicates that social resources influence the choice and utilization of coping strategies under specific stress conditions [38]. Overparenting may be accompanied by criticism, lack of warmth and support [39], leading to a reduction in social resources available to adolescents, thereby increasing their reliance on coping skills of problem avoidance and social withdrawal [40]. One study suggests that overparenting is associated with greater anxiety and stress [41]. Under high pressure, individuals from less supportive families tend to adopt avoidance coping strategies [42]. Additionally, overparenting fosters the development of dependency in adolescents and reduces their opportunities for autonomy and decision-making. Consequently, they may develop a cognitive avoidance style as a way to cope with the demands and expectations imposed by their parents [43].

At the same time, attachment theory suggests that overparenting may lead adolescents to develop a tendency towards insecure attachment, to develop an interpretation bias, to perceive the world as threatening, to interpret ambiguous stimuli as potentially hostile, and to potentially display more avoidant tendencies [44]. Overparenting may to some extent precipitate negative life events, and Beck’s cognitive theory states that once negative life events activate certain information processing schemas, the individual distorts the information, overestimates the magnitude and severity of the threat, underestimates the extent of coping resources, and overuses compensatory self-protective strategies such as cognitive, affective, or physical avoidance [45].

The relationship between cognitive avoidance and anxiety

Cognitive avoidance is considered a risk factor for the development and maintenance of anxiety, representing a core mechanism in the severity and perpetuation of anxiety [46–48]. Avoidant coping is a variant of emotion-focused coping, relying on emotion-centered coping strategies and is associated with depression and anxiety [49,50]. Cognitive avoidance can lead to persistent worry [51], leaving the individual vulnerable to the full spectrum of anxiety symptoms [52]. Contemporary behavioral theories emphasize the role of avoidance in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety [53]. Cognitive avoidance can be conceptualized as automatic (unconscious) or strategic (intentional) avoidance behavior, with strategic cognitive avoidance being highly characteristic of anxiety disorders, and cognitive avoidance is related to attentional bias, and the motivation for cognitive avoidance itself can lead to attentional bias [54]. Therefore, employing certain cognitive avoidance strategies may lead to a “rebound effect” [55], and attempts to suppress thoughts may result in an increase in the occurrence of target thoughts following the suppression attempt for a period of time [56]. Thought suppression exhibits paradoxical effects [57]. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 of this study posits that cognitive avoidance mediates the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety.

Although cognitive avoidance has been widely utilized to explain the development and maintenance of anxiety, research on the mediating mechanisms between overparenting and anxiety remains relatively limited, lacking a thorough understanding of underlying psychological processes. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety and the mediating role of cognitive avoidance between the two.

A total of 2000 students from Grade 7 to Grade 12 in Shandong Province, China were selected (942 males, accounting for 47.10%) from November to December 2022. The mean age was 15.50 ± 1.41 years, with 21.80% being only children. After the screening, 1931 valid questionnaires were obtained. 69 submitted questionnaires were discarded because of high levels of missing data or because their answers were fictitious or inconsistent. The questionnaire recovery rate was 96.55%. Specifically, Grade 7 students accounted for 0.98%, Grade 8 students accounted for 12.53%, Grade 9 students accounted for 12.69%, Grade 10 students accounted for 10.98%, Grade 11 students accounted for 35.75%, and Grade 12 students accounted for 1.56%.

Prior to the commencement of the study, verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants. Specifically, inclusion criteria included aged 12–18 years, fluency in Chinese, normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing. In the second step, participants were excluded from the study based on the following criteria: (a) had a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–5 confirmed mental disorders diagnosis, such as major depression disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, (b) showed acute psychotic symptoms and (c) took psychotropic medications. These exclusion criteria were selected because they indicated the need for a higher level of care. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Kashi University (IRB number: KSNU2022008). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Overparenting: The Overparenting Scale developed by Leung et al. was used to measure overparenting [58], which includes excessive parental involvement and supervision in all aspects of daily life, learning, and emotions. The scale consists of 44 items (e.g., “I grew up under my parents’ close supervision”). The scale employed a 6-point Likert scoring system ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher levels of overparenting. The Cronbach’s α of this scale in this study was 0.976, indicating excellent scale reliability.

Cognitive Avoidance: The Cognitive Avoidance Questionnaire (CAQ) was utilized in this study [36]. The questionnaire consists of five dimensions: thought suppression (e.g., There are things I try not to think about), thought substitution (e.g., Thinking about the past so that I don’t think about things that make me feel insecure about the future), attentional shifting (e.g., I always do something to take my mind off my thoughts), stimulus avoidance (e.g., I avoid behaviors that remind me of things I don’t want to think about), and imagery visualization (e.g., When I have images in my mind that bother me, I mentally say things to myself to replace those images). The Cronbach’s α of this scale in this study was 0.979, indicating good reliability.

Adolescent Anxiety: The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) developed by Wang et al. was employed to assess adolescent anxiety [59]. The scale consists of 20 items (e.g., I feel more nervous and anxious than usual (anxiety); I feel scared for no reason (fear)). The scale employs a 4-point Likert scoring system: 1 = None or very little time, 4 = Most or all of the time. Items 5, 9, 13, 17, and 19 are reverse-scored. The total score is multiplied by 1.25 to convert to standard scores for assessing anxiety levels. Although primarily designed for adults, it is sometimes used for adolescents aged 13–18 [60]. The Cronbach’s α of this scale in this study was 0.888, indicating good scale reliability.

The collected 1931 valid questionnaires were coded and entered into the database. Based on the datasets of all valid samples included in this study, we computed descriptive analyses and correlation n between all variables. In this study, Pearson correlation analysis is used to analyze the correlation between variables, and mediation analysis is used to analyze the mediation role. In this study, the correlation of the three variables is analyzed first, and then the mediation effect is further analyzed. SPSS 25.0 and Mplus 7.0 were used in this study, p < 0.05 means that the data difference is significant.

Due to the subjective nature of the questionnaire measurements obtained through participants’ self-reports, there might be common method bias. Therefore, this study employed Harman’s single-factor test to conduct an unrotated principal component analysis of all items in the administered questionnaires. Nine factors were generated, accounting for 70.47% of the variance, with the first factor explaining 38.08% of the variance, this was below the judgment criterion of 40%, indicating the absence of severe common method bias in this study.

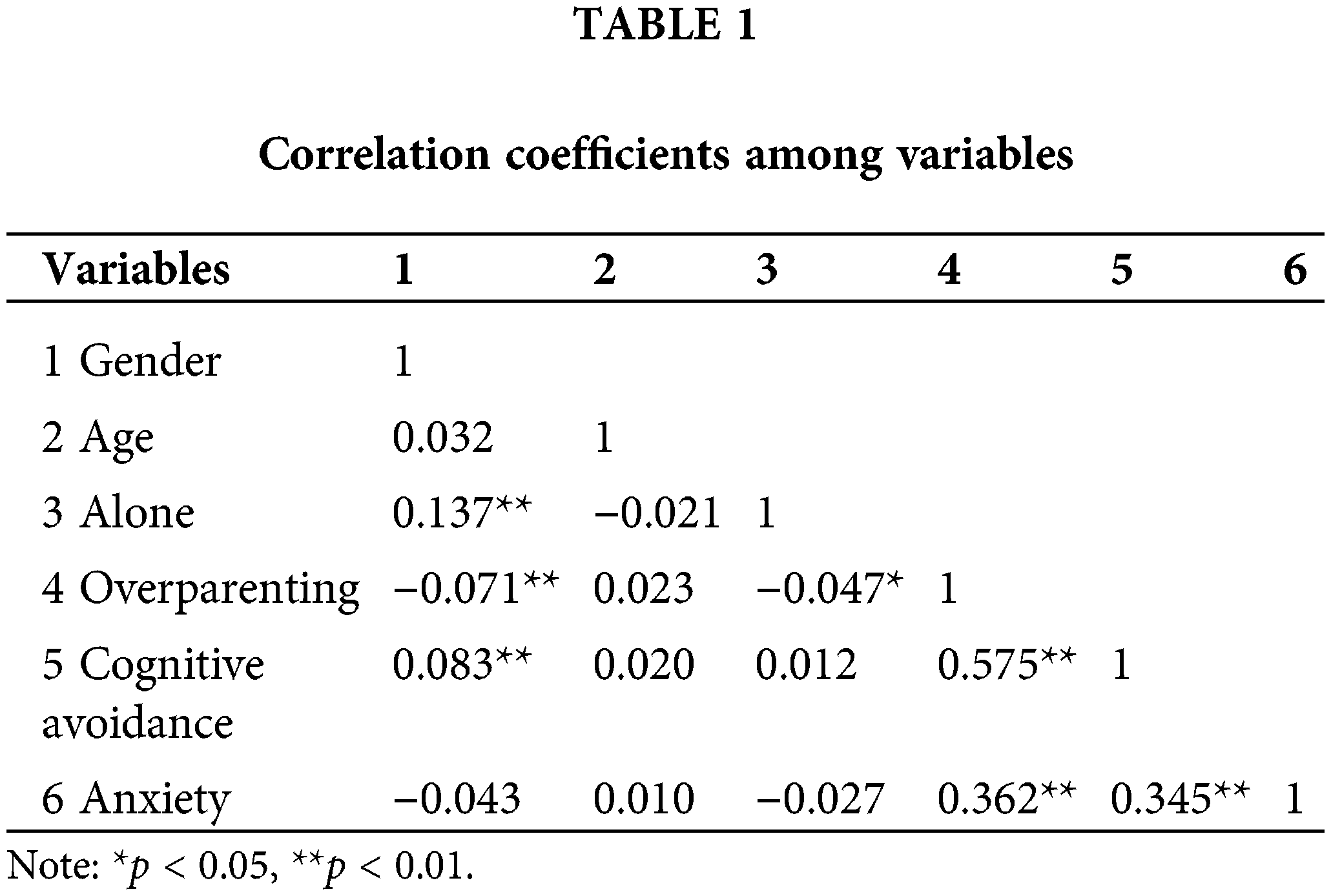

Results of the correlation analysis found that overparenting was significantly positively correlated with cognitive avoidance (p < 0.01) and anxiety (p < 0.01). Cognitive avoidance was also significantly positively correlated with anxiety (p < 0.01). Gender was significantly correlated with overparenting (p < 0.01), cognitive avoidance (p < 0.01), and anxiety (p < 0.01). However, age did not show significant correlations with any of the variables (p > 0.05). Therefore, to mitigate the influence of gender, gender will be treated as a control variable in subsequent studies (See Table 1).

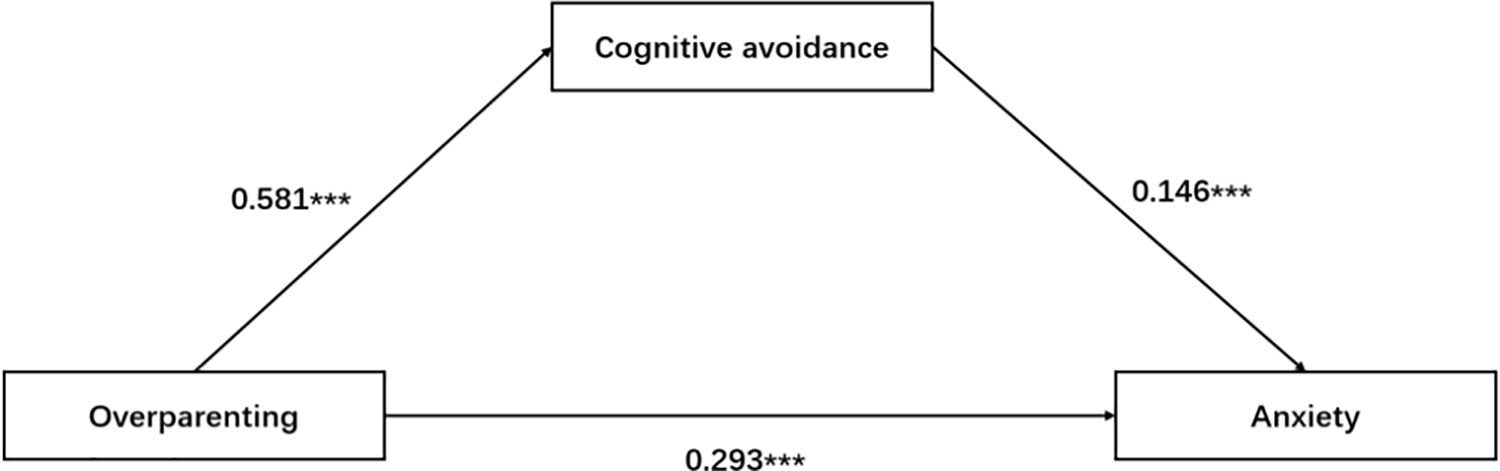

To control for demographic variables, after controlling for gender, structural equation modeling was employed to examine the mediating role of cognitive avoidance in the relationship between overparenting and anxiety. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate the mediation effect and conduct the mediation model test. Prior to data analysis, centering was conducted for all continuous variables. After controlling for gender, the direct effect of overparenting on anxiety was significant (bsimple = 0.293, p < 0.001), and the mediation effect of cognitive avoidance was 0.085 with a 95% confidence interval of [0.091, 0.144], accounting for 22.49% of the total effect, indicating that cognitive avoidance mediated the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety (See Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Mediation model. Note: ***p < 0.001.

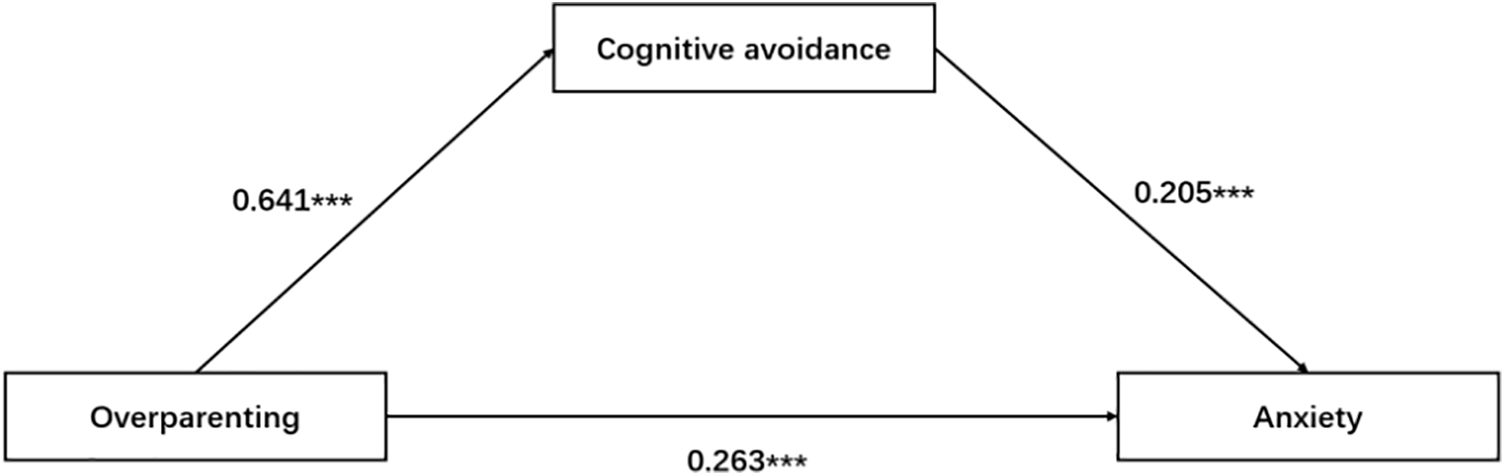

For male, the direct effect of overparenting on anxiety was significant (bsimple = 0.293, p < 0.001), and the mediation effect of cognitive avoidance was 0.131 with a 95% confidence interval of [0.132, 0.272], accounting for 33.25% of the total effect, indicating that cognitive avoidance mediated the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety (See Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Mediation model for male. Note: ***p < 0.001.

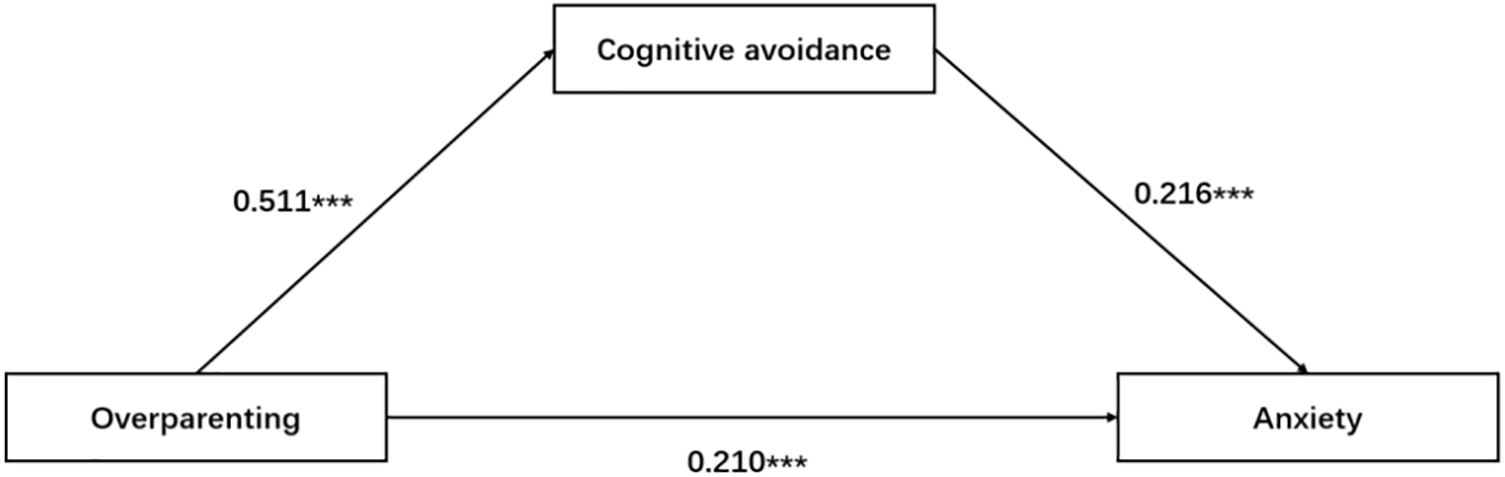

For female, the direct effect of overparenting on anxiety was significant (bsimple = 0.210, p < 0.001), and the mediation effect of cognitive avoidance was 0.111 with a 95% confidence interval of [0.152, 0.281], accounting for 34.58% of the total effect, indicating that cognitive avoidance mediated the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety (See Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Mediation model for female. Note: ***p < 0.001.

This study explored the relationship between parental overparenting and adolescent anxiety. The results showed a significant positive correlation between overparenting and anxiety, supporting Hypothesis 1. The findings of our research also provided supplementary evidence for Self-Determination Theory, indicating that parental overparenting undermines the satisfaction of children’s basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness [61]. Failure to meet these three needs may lead to psychological health problems or maladjustment [62], with anxiety being identified as one of the manifestations of maladjustment. Additionally, consistent with existing research, parents who engage in overparenting adopt behaviors that hinder adolescents’ autonomy development [63], leading to more frequent conflicts in parent-child relationships, which are associated with higher levels of anxiety. At the same time, the study reaffirmed that overparenting increases adolescents’ anxiety levels. Adolescents seek more autonomy and independence during the individuation process [64]. However, Parents engaged in overparenting fail to grant autonomy to their adolescent children and interfere with their daily lives and life direction [65]. For gender-specific analysis, our research found that cognitive avoidance and anxiety were more likely to be affected by overparenting in males than in females. This may be because men’s own cognitive processing is less sensitive than women’s, so it is more difficult to withstand the control of overbreeding, which leads to increased anxiety levels.

This study also explored the relationship between parental overparenting, cognitive avoidance, and adolescent anxiety. The results showed that there was a significant positive correlation between overparenting and cognitive avoidance and a significant positive correlation between cognitive avoidance and adolescent anxiety, indicating that cognitive avoidance mediates the relationship between parental overparenting and adolescent anxiety, supporting Hypothesis 2. The findings provide evidence support for the mechanism of cognitive avoidance, which was demonstrated as one of the coping styles that linked overparenting and anxiety in the present study. One of the mechanisms that support the role of coping as a mediator between negative life events and the effects of such events on mental and physical health [66]. Adolescents perceive parental overparenting as a stressor from the family environment, experiencing frustration of basic psychological needs, which leads to negative emotions and incorrect cognition [67], resulting in the adoption of irrational regulation strategies such as cognitive avoidance, which in turn increases the likelihood of developing anxiety symptoms. Results of related studies have found that poor parenting styles significantly predict adolescent psychological problems, and cognitive avoidance is a common psychological vulnerability factor [53], serving as a mediator between distressing experiences and psychological problems [68]. Cognitive avoidance is one of the non-adaptive strategies commonly used by individuals as an emotion regulation strategy [69], and if used over a long period of time, individuals will develop a complete set of avoidance strategies, which are not only ineffective, but also increase individual’s connection with the avoided objects, leading to psychological problems [70]. These findings corroborate with the results of the present study and fully illustrate the important mediating role of experiential avoidance between parental overparenting and adolescent anxiety.

Firstly, educators should encourage students to make decisions and face challenges on their own, establish positive teacher-student communication and emotional support; provide students with appropriate challenges to promote their autonomy and personal growth, teach them effective coping strategies, and cultivate their emotion regulation skills; and help them to reduce their reliance on cognitive avoidance and improve their ability to cope with stress and emotional distress, so as to promote their all-round development. Secondly, parents should relax their control and over-concern, encourage their children to make their own decisions and face challenges, and establish positive family communication and emotional support; develop their self-confidence and problem-solving skills, and teach them effective coping strategies; and at the same time, pay attention to their own mental health. Reducing stress, seeking balance, and leading healthy lifestyles can help to cope with anxiety, and can have a positive impact on the health and well-being of adolescents. In addition, professional psychological counselling, family counselling or relevant support agencies can provide appropriate guidance and assistance. Thirdly, psychological counselling services should focus on the identification and adjustment of adolescents’ cognitive avoidance strategies, teach them more effective coping strategies, and help them establish healthy emotion regulation mechanisms. This will help reduce the level of anxiety among adolescents and improve their quality of life. Lastly, schools and communities can organise relevant parent education and mental health education activities to raise parents’ awareness of the psychological characteristics of adolescents and help them better cope with the relevant problems.

Research limitations and future directions

Firstly, this study utilized self-report measures to assess all variables, which may be influenced by social desirability bias and other factors. For instance, although prior related research has found high reliability of self-report measures in assessing subjective experiences of overparenting [61], future research should consider simultaneous data collection from different sources, such as parental self-report and parental mutual ratings. Secondly, this study did not separately measure paternal and maternal overparenting, and fathers and mothers play different roles in children’s upbringing, which may have different effects on adolescent cognitive avoidance and anxiety. Future research should independently investigate paternal and maternal dimensions, providing more precise information for interventions. Thirdly, the participants in this study were limited to a specific region, and convenience sampling may lead to sampling errors. Therefore, caution is needed when generalizing the results of this study to adolescents in other regions. To further explore the impact of parental overparenting on adolescent anxiety, future research should collect data from children in various regions. Fourth, this study assessed anxiety symptoms, not clinical anxiety disorders. However, the sample may have included adolescents with anxiety or other psychiatric disorders, which may have biased the results, and diagnostic tools such as MINI-Kid or KSADS should be used to rule out psychiatric disorders in future studies.

This study examined the relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety and analysed the role of cognitive avoidance as a mediator. The results of the study showed that there was a significant positive relationship between overparenting and adolescent anxiety, validating the research hypothesis. More importantly, we found that cognitive avoidance played a significant mediating role between overparenting and adolescent anxiety, a finding that provides a new perspective for understanding the formation mechanism of adolescent anxiety and practical guidance for preventing and intervening in adolescent anxiety. However, future research still needs to further explore the differential manifestations of overparenting and cognitive avoidance in different cultures and groups in order to enrich and improve the existing theoretical models and practical intervention strategies.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by funding of Educational Development Research Center of Southern Xinjiang.

Author Contributions: Dawei Wang: design study, supervision, write and revise the manuscript; Ranran Wang: data collection, formal analysis and write the manuscript; Peng Yu: supervision, formal analysis and write the manuscript; Xiangyin Meng: supervision, formal analysis and revise the manuscript; Yixin Hu: design study, supervision, write and revise the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Kashi University (IRB number: KSNU2022008). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12:371–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Dickson SJ, Oar EL, Kangas M, Johnco CJ, Lavell CH, Seaton AH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of impairment and quality of life in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2024;27:342–56. doi:10.1007/s10567-024-00484-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zhu WL. Sleep quality and its influencing factors in adolescents with anxiety disorder. J Aerospace Med. 2023;34(2):224–7. [Google Scholar]

4. Li S, Liu Y, Li R, Xiao W, Ou J, Tao F, et al. Association between green space and multiple ambient air pollutants with depressive and anxiety symptoms among Chinese adolescents: the role of physical activity. Environ Int. 2024;189:108796. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2024.108796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Wang L, Wu XY, Xiao ZB, He Y. Research progress of exercise improving depression and anxiety in children and adolescents based on review. Fujian Sports Sci Technol. 2023;42(2):18–24+29 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

6. Slobodin O, Shorer M, Friedman Zeltzer G, Fennig S. Interactions between parenting styles, child anxiety, and oppositionality in selective mutismn. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiat. 2024. doi:10.1007/s00787-024-02484-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yaffe Y, Grinshtain Y, Harpaz G. Overparenting in parents of elementary school children: The direct association with positive parent-child relationship and the indirect associations with parental self-efficacy and psychological well-being. J Child Fam Stud. 2024;33(3):863–76. [Google Scholar]

8. Cline FW, Fay J. Parenting with love and logic: teaching children responsibility. Colorado Springs, CO, USA: Pinon Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

9. Jiao J, Segrin C. Overparenting and emerging adults’ insecure attachment with parents and romantic partners. Emerg Adulthood. 2022;10(3):725–30. [Google Scholar]

10. Jiao J. I came through you and belong not to you: Overparenting, attachment, autonomy, and mental health at emerging adulthood (Dissertation). The University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA; 2022. [Google Scholar]

11. Peterson GW, Hann D. Socializing children and parents in families. In: Sussman M, Steinmetz SK, Peterson G, editors. Handbook of marriage and the family. 2nd ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1999. p. 327–70. [Google Scholar]

12. Segrin C, Jiao J, Wang J. Indirect effects of overparenting and family communication patterns on mental health of emerging adults in China and the United States. J Adult Dev. 2022;29(3):205–17. [Google Scholar]

13. Zhang Q, Ji W. Overparenting and offspring depression, anxiety, and internalizing symptoms: a meta-analysis. Dev Psychopathol. 2023. doi:10.1017/S095457942300055X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jiao C, Cui M, Fincham FD. Overparenting, loneliness, and social anxiety in emerging adulthood: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Emerg Adulthood. 2024;12(1):55–65. [Google Scholar]

15. Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Cui M, Calabrese JR. Advancing understanding of overparenting and child adjustment: mechanisms, methodology, context, and development. J Soc Pers Relat. 2024;41(2):361–71. [Google Scholar]

16. Sagui-Henson SJ. Cognitive avoidance. In: Vock M, editor. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 1–3. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_302141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dugas MJ, Koerner N. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: current status and future directions. J Cogn Psychother. 2005;19(1):61. [Google Scholar]

18. Borkovec TD, Inz J. The nature of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: a predominance of thought activity. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28(2):153–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

19. Wegner DM, Zanakos SJ. Chronic thought suppression. J Pers. 1994;62(4):615–40. [Google Scholar]

20. Ebrahimi L, Amiri M, Mohamadlou M, Rezapur R. Attachment styles, parenting styles, and depression. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2017;15:1064–8. [Google Scholar]

21. Yang Y, Qi YJ, Chen X, Zhang ZX, Zhou YM, Zheng Y. A survey on the influence of parenting style and life events on emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. Chin J Psychiat. 2021;54(5):374–80 (In Chinese). doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn113661-20210201-00070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Adenzato M, Imperatori C, Ardito RB, Valenti EM, Della Marca G, D’Ari S, et al. Activating attachment memories affects default mode network in a non-clinical sample with perceived dysfunctional parenting: an EEG functional connectivity study. Behav Brain Res. 2019;372:112059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Zhang JY. The impact of over-parenting on the psychological development of children and adolescents. Adv Soc Sci. 2023;12(5):2526–32. doi:10.12677/ass.2023.125342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu HS. Theories on parent-child relation of rural left-behind families: Thoughts, comments, and applications. Tribune Soc Sci. 2021;4:158–68 (In Chinese). doi:10.14185/j.cnki.issn1008-2026.2021.04.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ma CQ, Huebner ES. Attachment relationships and adolescents’ life satisfaction: some relationships matter more to girls than boys. Psychol Sch. 2008;45(2):177–90. [Google Scholar]

26. Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds: i. Aetiology and psychopathology in the light of attachment theory. Br J Psychiat. 1977;130(3):201–10. doi:10.1192/bjp.130.3.201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Oshino S, Suzuki A, Ishii G, Otani K. Influences of parental rearing on the personality traits of healthy Japanese. Compr Psychiat. 2007;48(5):465–9. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.04.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Rousseau S, Scharf M. “I will guide you” The indirect link between overparenting and young adults’ adjustment. Psychiat Res. 2015;228(3):826–34. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Leung JTY. Too much of a good thing: perceived overparenting and wellbeing of Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Indic Res. 2020;13(5):1791–809. [Google Scholar]

30. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inquir. 2000;11(4):227–68. [Google Scholar]

31. Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M. A theoretical upgrade of the concept of parental psychological control: proposing new insights on the basis of self-determination theory. Dev Rev. 2010;30(1):74–99. [Google Scholar]

32. Creswell C, Murray L, Stacey J, Cooper P. Parenting and child anxiety. In: Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley; 2011. p. 299–322. [Google Scholar]

33. Gao J, Xi XR, Xiang SY, Hu SL. The effect of parental overprotection on the vulnerability of young children: the mediating role of anxiety. Chinese J Spec Educ. 2019;9:77–84 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

34. Gugliandolo MC, Costa S, Kuss DJ, Cuzzocrea F, Verrastro V. Technological addiction in adolescents: the interplay between parenting and psychological basic needs. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020;18:1389–402. [Google Scholar]

35. Behar E, DiMarco ID, Hekler EB, Mohlman J, Staples AM. Current theoretical models of generalized anxiety disorder (GADconceptual review and treatment implications. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(8):1011–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Jiao KY, Zhu YW, Fan WC, Zhou NN, Wang JP. Reliability and validity of cognitive avoidance questionnaire in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2017;25(6):1017–21 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

37. Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychol Bull. 1998;124:3–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

38. Moos RH, Holahan CJ. Dispositional and contextual perspectives on coping: toward an integrative framework. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59(12):1387–403. doi:10.1002/jclp.10229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Gerlsma C, Emmelkamp PMG, Arrindell WA. Anxiety, depression, and perception of early parenting: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 1990;10:251–77. [Google Scholar]

40. Haines J, Williams CL. Coping and problem solving of self-mutilators. J Clin Psychol. 1997;53:177–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

41. Segrin C, Woszidlo A, Givertz M, Montgomery N. Parent and child traits associated with overparenting. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2013;32(6):569–95. [Google Scholar]

42. Holahan CJ, Moos RH. Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:946–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

43. Grolnick WS, Raftery-Helmer JN, Flamm ES, Marbell KN, Cardemil EV. Parental provision of academic structure and the transition to middle school. J Res Adolesc. 2015;25(4):668–84. [Google Scholar]

44. Kirsch SJ, Cassidy J. Preschoolers’ attention to and memory for attachment-relevant information. Child Dev. 1997;68:1143–53. [Google Scholar]

45. Beck AT, Clark DA. An information processing model of anxiety: automatic and strategic processes. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:49–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

46. Schäfer JÖ, Naumman E, Holmes EA, Tuschen-Caffier B, Samson AC. Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: a meta-analytic review. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:261–76. doi:10.1007/s10964-016-0585-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Struijs SY, Lamers F, Rinck M, Roelofs K, Spinhoven P, Penninx BWJ. The predictive value of approach and avoidance tendencies on the onset and course of depression and anxiety disorders. Depression Anxiety. 2018;35:551–9. doi:10.1002/da.22760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Vanderveren E, Debeer E, Craeynest M, Hermans D, Raes F. Psychometric properties of the Dutch cognitive avoidance questionnaire. Psychol Belg. 2020;60(1):184–97. doi:10.5334/pb.522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Use of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations in a clinically depressed sample: factor structure, personality correlates, and prediction of distress. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59:423–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

50. Ben-Zur H. Coping styles and affect. Int J Stress Manag. 2009;16(2):87. [Google Scholar]

51. Xiao H, Shen Y, Zhang W, Lin R. Applicability of the cognitive model of generalized anxiety disorder to adolescents’ sleep quality: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2023;23(4):100406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

52. Koerner N, McEvoy P, Tallon K. Cognitive-behavioral models of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) toward a synthesis. In: Gerlach AL, Gloster AT, editors. Generalized anxiety disorder and worrying: a comprehensive handbook for clinicians and researchers. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley; 2020. p. 117–50. doi: 10.1002/9781119189909.ch7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(6):1152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

54. Lavy EH, van den Hout MA. Cognitive avoidance and attentional bias: causal relationships. Cogn Ther Res. 1994;18:179–91. [Google Scholar]

55. Olatunji BO, Moretz MW, Zlomke KR. Linking cognitive avoidance and GAD symptoms: the mediating role of fear of emotion. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(5):435–41. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Merckelbach H, Muris P, Van den Hout M, De Jong P. Rebound effects of thought suppression: instruction-dependent? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1991;19(3):225–38. doi:10.1017/S0141347300013264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Burke M, Mathews A. Autobiographical memory and clinical anxiety. Cogn Emot. 1992;6(1):23–35. doi:10.1080/02699939208411056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Leung JTY, Shek DTL. Validation of the perceived chinese overparenting scale in emerging adults in Hong Kong. J Child Fam Stud. 2017;27(1):103–17. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0880-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Wang ZY, Chi YF. Self-rating anxiety scale (SAS). Shanghai Arch Psychiat. 1984;2:73–4 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

60. Sun J, Dunne MP. An exploratory study of the applicability of the Zung’s self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) among Chinese adolescents. Psychol Rep. 2001;88(1):117–24. [Google Scholar]

61. Lin S, Yu C, Chen J, Sheng J, Hu Y, Zhong L. The association between parental psychological control, deviant peer affiliation, and internet gaming disorder among Chinese adolescents: a two-year longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

62. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

63. Xa YJ, Kong FC. The connotation, influence and aftereffect of helicopter parenting. J Psychol Sci. 2021;3:612. [Google Scholar]

64. Grotevant HD, Cooper CR. Individuation in family relationships: a perspective on individual differences in the development of identity and role-taking skill in adolescence. Hum Dev. 1986;29(2):82–100. [Google Scholar]

65. Givertz M, Segrin C. The association between overinvolved parenting and young adults’ self-efficacy, psychological entitlement, and family communication. Commun Res. 2014;41(8):1111–36. [Google Scholar]

66. Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Wells KB. Personal and psychosocial risk factors for physical and mental health outcomes and course of depression among depressed patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(3):345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

67. El-Sheikh M, Tu KM, Erath SA, Buckhalt JA. Family stress and adolescents’ cognitive functioning: sleep as a protective factor. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28(6):887–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

68. Romero-Moreno R, Losada A, Márquez-González M, Mausbach BT. Stressors and anxiety in dementia caregiving: multiple mediation analysis of rumination, experiential avoidance, and leisure. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(11):1835–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

69. Sahib A, Chen J, Cárdenas D, Calear AL. Intolerance of uncertainty and emotion regulation: a meta-analytic and systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2023;101:102270. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Cioffi D, Holloway J. Delayed costs of suppressed pain. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;64(2):274–82. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools