Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Influence of Vulnerable Narcissism on Social Anxiety among Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Self-Concept Clarity and Self-Esteem

1 Key Laboratory of Behavioral and Mental Health of Gansu Province, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

2 School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yuetan Wang. Email: ; Xiaobin Ding. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Social Stress, Adversity, and Mental Health in Transitional China)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(6), 429-438. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.050445

Received 06 February 2024; Accepted 24 April 2024; Issue published 28 June 2024

Abstract

Social anxiety (SA) is a prevalent mental health issue among adolescents, and vulnerable narcissism (VN) can exacerbate this condition. This study aims to investigate the impact of vulnerable narcissism on social anxiety in adolescents, specifically focusing on the mediating effects of self-concept clarity (SCC) and self-esteem (SE) in the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety. Through cluster sampling, a questionnaire survey was conducted among 982 students from three secondary schools in two provinces. The data was analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM). The results revealed that there was a significant negative correlation between vulnerable narcissism and both self-concept clarity and self-esteem, while there was a significant positive correlation between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety. Additionally, self-concept clarity showed a significant positive correlation with self-esteem but had a negative correlation with social anxiety. Both self-concept clarity and self-esteem played an intermediary role in the chain linking vulnerable narcissism to social anxiety. This study confirms the mediating role of both self-concept clarity and self-esteem in explaining how vulnerable narcissism influences social anxiety, providing valuable insights into its underlying mechanism.Keywords

Social anxiety (SA) is a common mental health problem among adolescents. During this period, adolescents’ cognition, brain and social attitudes will change, leading to the tendency of self-doubt and negative emotional interference, and being sensitive to others’ criticism or negative reactions, accompanied by emotional instability and inner vulnerability [1], which makes social anxiety most likely to occur during this period [2]. Moreover, it can have an impact on individuals’ education, interpersonal functioning, and personal life [3,4], and when it becomes severe, it can evolve into social anxiety disorder-one of the most common chronic psychological disorders [5–7]. The hallmark feature of this disorder is significant and persistent fear of humiliation or scrutiny by others, often leading to psychological distress and social or relational problems [8]. This poses significant challenges for families, schools, and society in terms of addressing academic achievement among adolescents [9], peer relationships [10,11], as well as physical and mental well-being [12]; furthermore, social anxiety disorder may persist into adulthood [13], impacting sustainable development in adolescents.

In the trend of exploring social anxiety personality traits, narcissism, especially vulnerable narcissism (VN) sensitive to potential injury, has received widespread attention from scholars [14]. Vulnerable narcissism is a prevalent phenomenon in the fields of personality and social psychology, characterized by heightened sensitivity to external evaluations, increased susceptibility to depression, anxiety, shyness, and poor mental health-all of which are significant risk factors for developing social anxiety [15,16]. Vulnerable narcissists often display traits such as self-pity, hypersensitivity, emotional volatility, and excessive focus on external evaluations, which can give rise to challenges in interpersonal relationships. They possess both egocentric tendencies and a susceptibility to criticism and rejection, potentially leading to fragile self-esteem (SE) and emotional instability [17]. Although vulnerable narcissists desire positive attention and affirmation, this is a form of false grandiosity. They are usually inwardly shy and tend to avoid any risks that may lead to failure [17], resulting in feelings of inferiority, depression, anxiety, and lower levels of mental health [18], making them prone to deviant behaviors. Therefore, their behavior becomes more complex and influenced by external factors. Vulnerable narcissism represents pathological psychological distress and fragile self-esteem [16], thus closely relating to negative psychological phenomena. vulnerable narcissism is a more clinical construct of narcissism [19] because it has both internal and interpersonal malicious associations, such as sensitivity to criticism, shame, depression, incompetence, anxiety, defensiveness, social avoidance behavior, hostility, revengeful thoughts; interpersonal stressors; low self-esteem; and poor well-being [20,21]. Vulnerable narcissism is characterized by self-pity, self-blame, negative self-perception, hypersensitivity, and emotional instability. Vulnerable narcissists tend to develop defensive and avoidant relationships in response to criticism or relationship frustration as a means of protecting their fragile self-esteem, which can lead to chronic anxiety [22].

Cognitive theories emphasize the importance of self-focus in maintaining social anxiety [13], and vulnerable narcissists are individuals with high self-focus who provide an effective window for understanding adolescent social anxiety issues. Furthermore, self-concept development spans throughout one’s life, but the adolescence stage is particularly sensitive and focused on self-concept. Vulnerable narcissists are prone to difficulties in forming or identifying with their self-concepts, and negative aspects of the self-concept further increase an individual’s risk for social anxiety [23,24]. Vulnerable narcissists are extremely sensitive to evaluation. Due to their fragile self-esteem and oversensitivity, they will take a way to avoid evaluation, thus losing the opportunity to clarify their self-concept, leading to a chaotic and unclear self-concept experience [25]. Self-esteem is an important dimension within the self-concept [26], and Self-Esteem Threat Management Theory suggests that individuals with low-self-esteem often doubt their abilities limiting the effectiveness of their regulatory mechanisms preventing effective alleviation of anxious emotions within social situations [27]. In addition, vulnerable narcissists are generally more sensitive, vulnerable to traumatic events in life, highly sensitive to their own negative emotions, unable to produce correct and objective self-evaluation, and therefore report lower self-esteem [17]. Therefore, it holds significant meaning for exploring how vulnerable narcissism influences the black box behind social anxiety among adolescents.

Previous Research and Hypothesis Development

The correlation between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety has been confirmed by several studies [14,22,24,28], all of which have found a positive relationship. Individuals with vulnerable narcissism often experience anxiety in their social interactions. Research conducted by Oh et al. [28] suggests that the personality traits of vulnerable narcissists, such as grandiose fantasies and a sense of entitlement, have maladaptive effects that predict social anxiety. They also exhibit characteristics of sensitivity and vulnerability, which are associated with various maladjustments and pathologies that can lead to social anxiety. Bae et al. [29] argue that adolescents with higher levels of vulnerable narcissism tend to avoid interpersonal relationships due to their desire for approval from others and fear of negative evaluations, which leads them to encounter more difficulties in interpersonal relationships and results in social anxiety [30]. Vulnerable narcissists often engage in avoidance strategies due to their sensitivity, leading to a higher tendency for distorted self-perception and difficulties in forming or identifying a coherent self-concept compared to overt narcissists [23,24]. This is because vulnerable narcissists struggle with integrating consistent information about themselves [31]. Additionally, ambiguous self-concept is closely related to adolescent maladaptive behaviors and problematic Internet use [25].

Previous studies have shown that self-concept clarity (SCC) is negatively correlated with social anxiety [32], while individuals with social anxiety tend to absorb negative information about themselves [33,34], which may lead to self-doubt in individuals. Self-concept clarity is also closely related to these negative information [35]. The theory of positive emotion expansion and construction believes that negative emotions will reduce individuals’ instantaneous thinking and sequential activities, hindering the construction of individual resources [36]. Self-esteem is an important psychological resource in the construction of individual positive emotions. Individuals with a vague self-concept will experience strong negative emotions [37], and negative emotions are an important factor in the level of self-esteem [38].

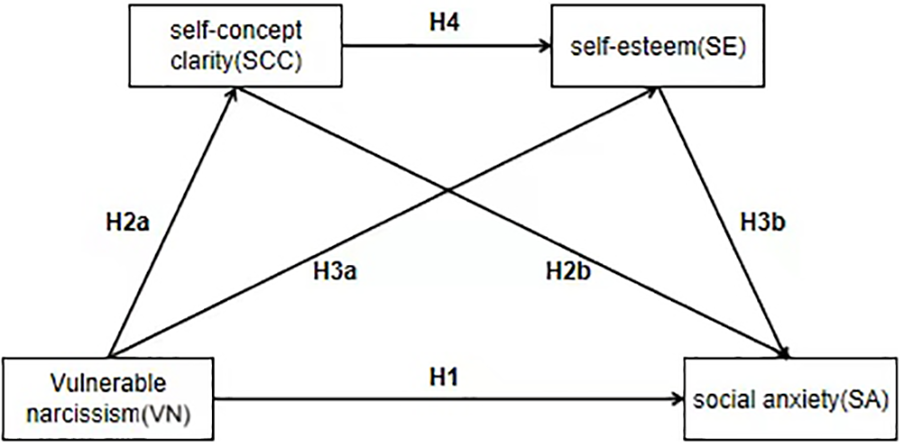

Given this, it is crucial to comprehend the potential mediating role of clarity of self-concept and self-esteem in the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety among adolescents for effectively addressing the escalating social anxiety behaviors in this age group. The primary objective of the current study is to explore both direct and indirect connections between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety among adolescents through chain mediation estimation. The theoretical hypotheses presented in Fig. 1 serve as a guiding framework for this research.

Figure 1: Mediation model diagram.

Due to the current media climate and prevailing culture of consumerism, narcissistic themes have gradually permeated contemporary teenagers [14]. Growing up in such an environment, adolescents are more susceptible to developing narcissistic tendencies when they fail to obtain evaluations and praise from others [39]. The grandiosity exhibited by vulnerable narcissists is deceptive, often leading them to adopt avoidance behaviors when confronted with potential failures [17], thereby negatively impacting their social mindset and skill development.

Secondly, hidden narcissists are highly egocentric, highly sensitive to their own negative emotions, and have a fragile self-esteem, and cannot reasonably integrate information consistent with themselves [31]. In addition, adolescents with hidden narcissistic tendencies have a negative impact on school life adaptation [29] and Internet use [25] due to their low self-concept clarity. In addition, among people with lower self-concept, self-concept clarity is negatively correlated with social anxiety [32,40,41], self-esteem will also have low performance [38]. There is a strong and significant positive correlation between narcissism and self-esteem [42]. Individuals with high levels of vulnerable narcissism have interpersonal problems due to low self-esteem. Although individuals with high levels of privilege and self-admiration, implicit narcissists have a heavy sense of inferiority, cannot objectively understand themselves, and are more passive when interacting with others. Experiencing more interpersonal distress is more likely to trigger social anxiety [37,38].

In summary, the following hypotheses are proposed in this study (Suppose the model diagram is shown in Fig. 1):

Hypothesis 1 (H1). vulnerable narcissism is positively associated with social anxiety.

Hypothesis 2 (H2a-H2b). The impact of vulnerable narcissism on social anxiety is mediated by self-concept clarity.

Hypothesis 3 (H3a-H3b). Self-esteem mediates the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety.

Hypothesis 4 (H2a-H4-H3b). Self-concept clarity and self-esteem act as sequential mediators in the link between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety.

The cluster sampling method was employed in this study to ensure the representativeness of the samples by preserving the structure and characteristics of the entire population, thereby facilitating the acquisition of more precise and reliable research findings [43]. A questionnaire survey was conducted in three public high schools across two provinces in China, excluding students with mental illness or major incidents within the past three months. A total of 1060 questionnaires were distributed during the study. If a participant’s responses matched or exceeded 80% similarity across all questions, if data was missing, or if answers were irrelevant, their questionnaires were deemed invalid. Ultimately, 78 invalid questionnaires were excluded from analysis while 982 valid questionnaires remained for inclusion in this study, resulting in an effective recovery rate of 92.64%. The questionnaire comprised five sections encompassing demographic information such as gender and only child status; place of residence; living arrangements with parents; monthly household income; and four scales.

The implicit narcissistic personality inventory

The present study employed the Narcissistic Personality Inventory developed by Zheng et al. [44], which comprises 15 items rated on a 5-point. These questions included statements such as ‘People often let me down’ and ‘I have good taste in aesthetics’. The inventory encompasses three dimensions: vulnerability, entitlement, and admiration. In this study, the overall Cronbach’s α coefficient for the scale was found to be 0.91, with individual Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.90, 0.87, and 0.75 for vulnerability, entitlement, and admiration, respectively, indicating high reliability of the subscales. Confirmatory factor analysis conducted using AMOS 24.0 yielded favorable results with χ2/df = 1.66, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.991, IFI = 0.993, GFI = 0.982; suggesting strong structural validity of the instrument utilized in this research endeavor.

The self-concept clarity scale

The self-concept clarity scale, originally developed by revised by Niu et al. [45], was employed in this study. The questionnaire comprised 12 items, each scored on a 5-point Likert scale. With the exception of items 6 and 11, all other items were reverse-scored. These questions included things like ‘My views of myself often conflict with each other’ and ‘I spend a lot of time thinking about what kind of person I am’. The internal consistency reliability of this scale, as measured by Cronbach’s α coefficient, was found to be high at 0.94 in this study. Confirmatory factor analysis results indicated good structural validity with χ2/df = 1.12, RMSEA = 0.01, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.999, IFI = 0.999, and GFI = 0.990.

The revised Chinese version of Rosenberg self-esteem scale [46] was selected. The questionnaire consisted of 10 items and adopted a 4-point scoring method. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.92. These questions included ‘I feel I have many good qualities’ and ‘I feel I have few things to be proud of’. Results from confirmatory factor analysis indicated favorable structural validity, as evidenced by χ2/df = 1.38, RMSEA = 0.02, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.997, IFI = 0.998, GFI = 0.990.

Social anxiety scale for adolescents

The Chinese version of the social anxiety scale used in this study [47], encompassing three dimensions: fear of negative evaluation, avoidance and distress in unfamiliar situations, and avoidance and distress in general situations (hereinafter referred to as unfamiliar situation avoidance distress and general situation avoidance distress). These included questions such as ‘I feel like people are talking about me behind my back’ and ‘I’m always worried about what other people think of me’. In this study, the scale demonstrated high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.85. Additionally, the subscale for negative evaluation of fear exhibited excellent reliability with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.88. The unfamiliar situation avoidance distress and general situation avoidance distress subscales also displayed good internal consistency with coefficients of 0.85 and 0.77, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the structural validity of the scale, yielding satisfactory fit indices: χ2/df = 3.41, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.973, TLI = 0.966, IFI = 0.973, GFI = 0.960.

In this study, SPSS 26.0 was employed for data analysis and processing. The primary statistical analysis methods encompassed descriptive statistics, independent samples t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Pearson correlation analysis, and AMOS 24.0 for chain mediation testing.

Due to the questionnaire method employed for data collection in this study, there is a possibility of common methodology bias. Hence, prior to data analysis, the Harman single factor test was conducted to assess and mitigate any potential common method bias.

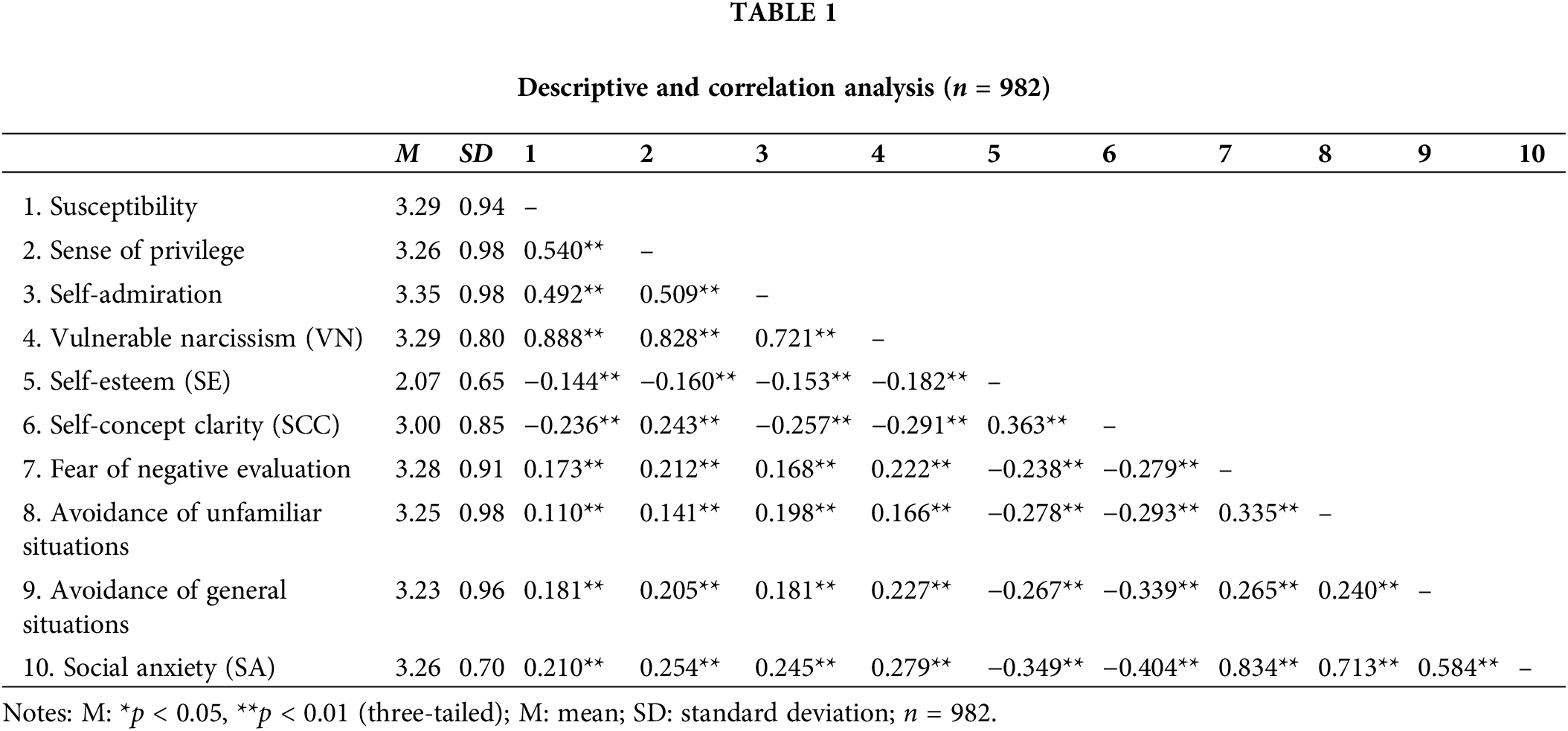

Correlation and descriptive test

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analysis results for vulnerable narcissism and its three dimensions (susceptibility, sense of entitlement, self-admiration), as well as self-esteem, self-concept clarity, and social anxiety along with its three dimensions (fear of negative evaluation, avoidance of unfamiliar situations, and avoidance of general situations). The findings indicate significant positive correlations between vulnerable narcissism (r = 0.279, p < 0.01) and its three dimensions (susceptibility: r = 0.210, p < 0.01; sense of entitlement: r = 0.254, p < 0.01; self-admiration: r = 0.245, p < 0.01) with social anxiety. Additionally, vulnerable narcissism exhibits significant positive associations with the three dimensions of social anxiety (fear of negative evaluation: r = 0.222, p < 0.01; avoidance of unfamiliar situations: r = 0.166, p < 0.01; avoidance of general situations: r = 0.227, p < 0.01). Furthermore, vulnerable narcissism demonstrates a significant negative correlation with both self-esteem (r = −0.182, p < 0.01) and self-concept clarity (r = −0.291, p < 0.01). Moreover, self-concept clarity is significantly positively correlated with self-esteem (r = 0.363, p < 0.01). The specific correlation coefficients are presented in Table 1.

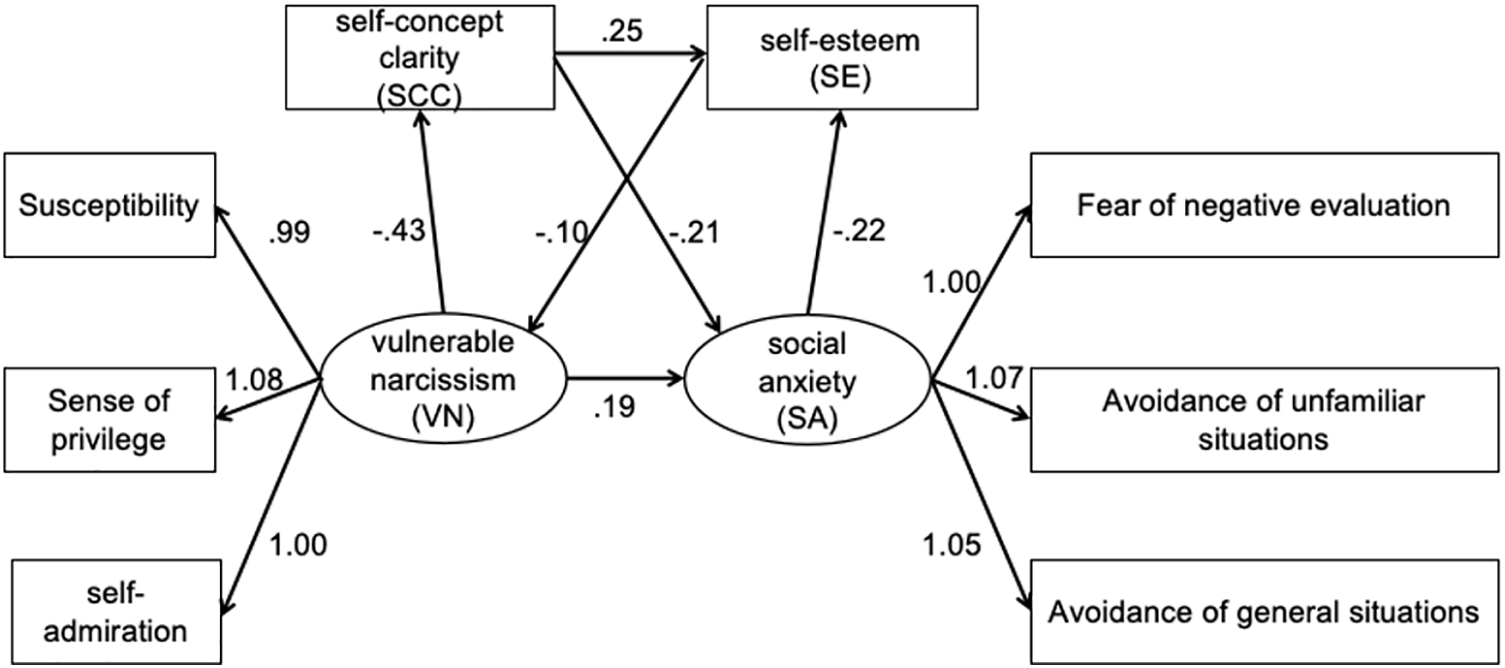

To test the hypothesis, we constructed a structural equation model with vulnerable narcissism as the independent variable, social anxiety as the dependent variable, and self-esteem and self-concept clarity as the mediating variables. The results indicate a good fit between the data and the model, with fitting indexes of χ2/df = 1.932, RMSEA = 0.031, SRMR = 0.022, CFI = 0.990, TLI = 0.982 (all falling within the recommended range). The final model is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Mediation effect model of self-esteem, self-concept clarity, vulnerable narcissism, social anxiety. n = 982.

The information depicted in the figure indicates that, firstly, there is a significant direct relationship between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety (r = 0.19, p < 0.01). The model analysis in Fig. 1 illustrates the three dimensions of implicit narcissism and social anxiety.

Secondly, vulnerable narcissism significantly and negatively predicts self-concept clarity (r = −0.43, p < 0.01), which in turn significantly and negatively predicts social anxiety (r = −0.21, p < 0.01). This suggests that self-concept clarity acts as a mediating factor in the association between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety.

Finally, it is observed that self-concept clarity positively predicts adolescents’ self-esteem (r = 0.25, p < 0.01). When considering the previous analysis collectively, it can be tentatively concluded that both self-concept clarity and self-esteem play sequential mediating roles in linking adolescent vulnerable narcissism to social anxiety through four distinct pathways.

Path 1: vulnerable narcissism (VN) → social anxiety (SA);

Path 2: vulnerable narcissism (VN) → self-concept clarity (SCC) → social anxiety (SA);

Path 3: vulnerable narcissism (VN) → self-esteem (SE) → social anxiety (SA);

Path 4: vulnerable narcissism (VN) → self-concept clarity (SCC) → self-esteem (SE) →social anxiety (SA).

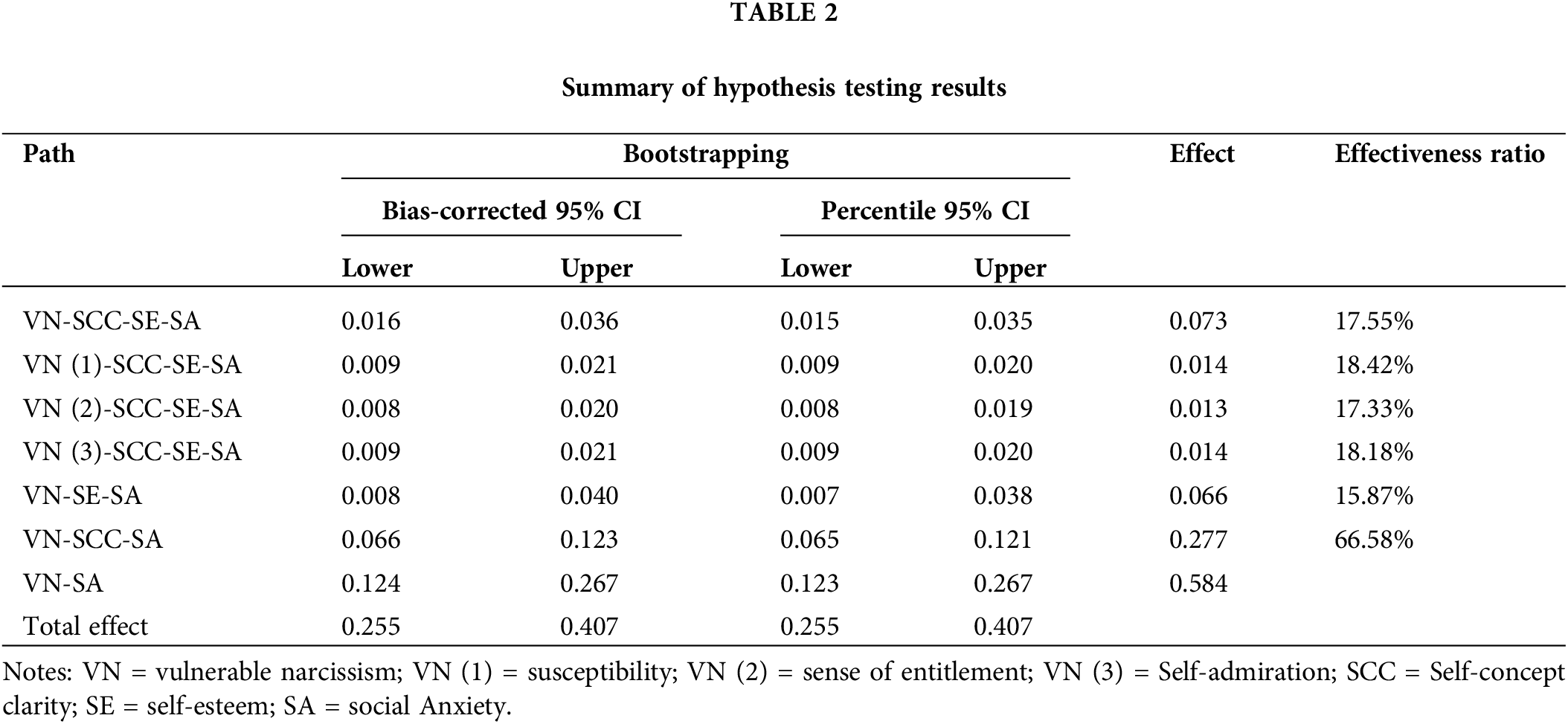

The significance of the mediating effect was further examined through non-parametric percentile bootstrap analysis, which involved testing the mediating effect with 5000 samples at a 95% confidence level. As presented in Table 2, Path 1 exhibited a direct effect of 0.584 (95% CI: 0.123, 0.267) and Z = −5.323, indicating a significant relationship between vulnerable narcissism (VN) and social anxiety (SA), thus confirming Hypothesis 1.

Additionally, Path 2 demonstrated a mediating effect of 0.277 (95% CI: 0.065, 0.121), accounting for approximately 66.58% of the total indirect effect with Z = 6.501, suggesting a significant chain mediation effect mediated by self-concept clarity (SCC) between vulnerable narcissism (VN) and social anxiety (SA), thereby validating Hypothesis 2.

The indirect effect of Path 3 is 0.066, accounting for 15.87% of the total indirect effect, with a confidence interval (95% CI) of (0.007, 0.038), Z = 3.000. This finding suggests that self-esteem (SE) significantly mediates the relationship between vulnerable narcissism (VN) and social anxiety (SA), providing support for Hypothesis 3.

Furthermore, the indirect effect of Path 4 is 0.073, accounting for 17.55% of the total indirect effect, with a 95% CI of (0.015, 0.035), Z = 4.800. This indicates that both self-concept clarity (SCC) and self-esteem (SE) sequentially mediate the association between adolescent vulnerable narcissism (VN) and social anxiety (SA), thereby confirming Hypothesis 4. The three dimensions of vulnerable narcissism (VN) are susceptibility, sense of entitlement, and self-admiration; the indirect effect of susceptibility is 0.014, accounting for 18.42% of the total indirect effect, with 95% CI of [0.009, 0.020]; the indirect effect of sense of entitlement is 0.013, accounting for 17.33% of the total indirect effect, with 95% CI of [0.008, 0.018]; the indirect effect of self-admiration is 0.014, accounting for 18.18% of the total indirect effect, with 95% CI of [0.009, 0.020]; this shows that self-concept clarity (SCC) and self-esteem (SE) play a mediating role in the association between the three dimensions of adolescent vulnerable narcissism (VN) and social anxiety (SA) in turn (see Table 2). The dimensional analysis once again shows the validity of Hypothesis 4.

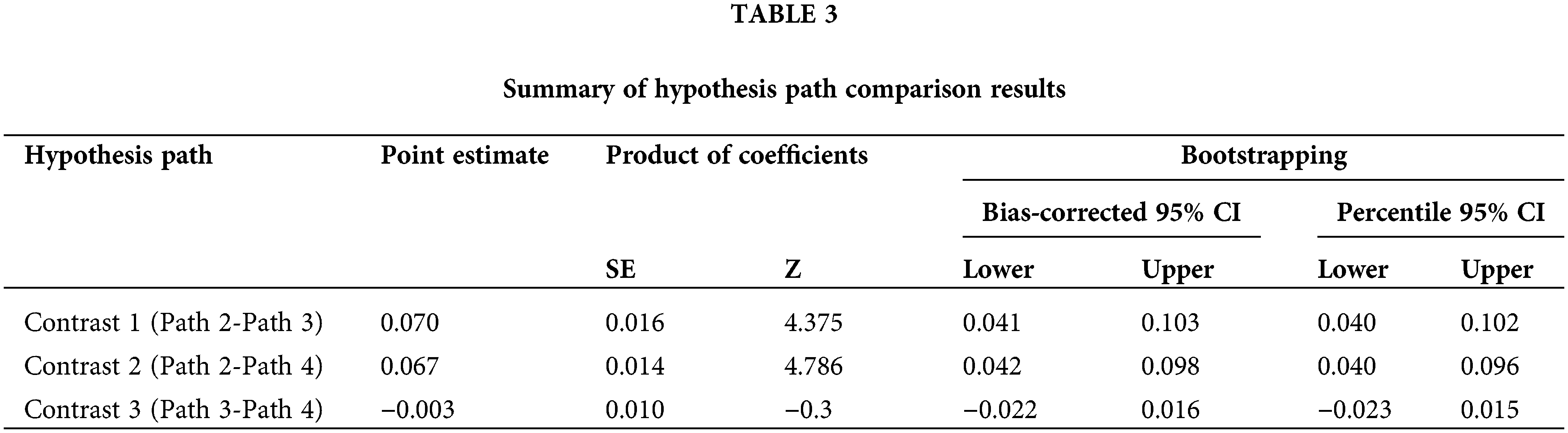

To further investigate the disparities between these pathways, we employed the deviation-corrected percentile Bootstrap test (5000 samples). The outcomes are presented in Table 3. Initially, a significant distinction was observed between Path 2 and Path 3, with Path 2 exhibiting significantly superior performance compared to Path 3 (95% CI = [0.040, 0.102], Z = 4.375). Additionally, there was a notable difference between Path 2 and Path 4, with Path 2 demonstrating significantly better results than Path 4 (95% CI = [0.040, 0.096], Z = 4.786). Simultaneously, no substantial discrepancy was found between Path 3 and Path 4 (95% CI = [−0.023, −0.015], Z = −0.3). In conclusion, among the three mediating effect Paths examined herein, the independent mediating effect of clear self-concept emerges as the most prominent.

Interpretation of the findings

Based on the underlying mechanism of how vulnerable narcissism in adolescents impacts social anxiety, this study aims to gain a deeper understanding of how vulnerable narcissism and its internal dimensions (vulnerability, entitlement, self-admiration) influence social anxiety. The findings indicate a significant positive correlation between adolescents’ vulnerable narcissism and its dimensions with social anxiety and its dimensions. Self-concept clarity plays a mediating role between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety. Additionally, self-esteem also acts as a mediator between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety. Furthermore, there is evidence of a sequential mediating effect of self-concept clarity and self-esteem between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety.

Firstly, the descriptive statistics reveal that the mean score for vulnerable narcissism is 3.29, indicating a moderate level. This suggests that adolescents generally exhibit an inflated sense of their own uniqueness and perceive themselves as superior, while also displaying a moderate preoccupation with self-centered fantasies. The average score for self-concept clarity is 3.00, falling within the moderate range, suggesting that adolescents’ self-perceptions are still in the process of integration and development. It is worth noting that self-concept clarity often has implications for adolescent learning and daily life [37], making it a matter of concern for educators. The mean score for self-esteem is 2.07, falling within the moderate range. This indicates that overall levels of self-esteem among participants are steadily developing as adolescents undergo rapid physical and psychological growth and gradually enhance their cognitive evaluations of themselves. The mean score for social anxiety is 3.26, also falling within the moderate range. This suggests that although there may be individual differences due to genetic factors, contemporary adolescents generally grow up in supportive family environments with understanding peers. They possess a high level of identity formation and strong learning abilities while establishing some degree of confidence; all these factors contribute to reducing levels of social anxiety.

Secondly, this study has revealed that vulnerable narcissism is a positive predictor of social anxiety among adolescents. This implies that individuals with traits of vulnerable narcissism, characterized by sensitivity to evaluation and vulnerability, experience heightened levels of anxiety in social interactions, which is consistent with previous research [14]. Those who tend towards vulnerable narcissism struggle to maintain their exaggerated defense mechanisms due to increased self-crisis awareness [48]. When their inflated self-image is challenged by the fragility and sensitivity of interpersonal relationships, they worry about negative evaluations of their behavior or emotions and experience high levels of internalized negative emotions. To protect themselves from such threats, they exhibit avoidance behaviors related to evaluative situations leading to an increase in social anxiety.

Furthermore, there exists a significant negative correlation between vulnerable narcissism and clarity of self-concept. This finding supports previous studies conducted abroad [22,31]. Vulnerable narcissists have a confused sense of self-concept which makes them sensitive to evaluative conditions and prone to negative emotions. As a result, they avoid evaluative situations and miss out on opportunities for forming coherent clear and stable self-concepts. Consequently, their self-concept becomes muddled resulting in inaccurate information about themselves being received. This increases the likelihood of experiencing difficulties in forming a well-defined self-concept.

Meanwhile, there exists a significant inverse correlation between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem among adolescents, which is consistent with the content of DSM-5. According to DSM-5, individuals exhibiting vulnerable narcissistic tendencies may have a fragile self-esteem, thereby supporting previous research findings [49]. While individuals with vulnerable narcissism may experience concerns regarding how they are perceived by others, unlike overt narcissists who employ self-protective mechanisms to uphold high levels of self-worth, those with vulnerable narcissism tend to safeguard themselves through avoidance strategies. Their enduring hypersensitivity and disappointment stemming from unfulfilled expectations contribute to an overall diminished evaluation of themselves and lower levels of self-esteem. Thus, it can be observed that vulnerable narcissism serves as a defensive mechanism aimed at compensating for low or fragile self-esteem.

Consistent with numerous prior research findings in this study are the negative associations between self-esteem and social anxiety [48]. In other words, adolescents possessing elevated levels of self-esteem demonstrate greater confidence and proactivity in social situations. They exhibit more positive psychological traits that render them more appealing to others and elicit better feedback from them. This further reinforces their confidence within a positive cycle of social mindset. Conversely, low levels of self-esteem yield the opposite effect. Therefore, enhancing levels of self-esteem is crucial for mitigating social anxiety among adolescents and fostering healthy interpersonal relationships.

Thirdly, the findings suggest that the clarity of one’s self-concept serves as a mediator between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety. The implicit narcissists, despite their highly self-centered characteristics, face a disadvantage in developing a self-concept due to their lack of a clear understanding of themselves and an exaggerated perception of external threats. Consequently, this hinders their ability to establish a coherent self-identity and leads them to seek avoidance or experience anxiety within interpersonal relationships. Therefore, when dealing with adolescents who exhibit strong inclinations towards vulnerable narcissism while also experiencing social anxiety, it is crucial to initially assess the level of clarity and integration in their understanding of themselves. As they mature, their self-concept gradually becomes more refined and incorporates conflicting information into a meaningful whole [50,51]. Henceforth, during the process of growth—particularly throughout the critical period of adolescence—it becomes imperative to provide appropriate support through counseling or therapy for these individuals.

Meanwhile, this study validates the hypothesis that self-esteem serves as a mediating factor between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety. This suggests that individuals with a propensity for vulnerable narcissism, stemming from their prolonged hypersensitivity and disappointment resulting from unfulfilled expectations, encounter a decline in self-awareness and evaluation. Consequently, they face challenges in effectively navigating social situations and subsequently develop symptoms of social anxiety. Therefore, to effectively mitigate social anxiety, indirect approaches should be prioritized. For instance, if a high school student exhibit pronounced tendencies towards vulnerable narcissism alongside social anxiety, particular attention should be directed towards enhancing their self-evaluation. From the perspective of cognitive psychology, low self-esteem is regarded as maladaptive cognition while high self-esteem signifies relatively more functional cognitive patterns [52]. This implies that future research could explore the implementation of cognitive therapies aimed at ameliorating levels of self-esteem as an intervention for alleviating social anxiety among individuals with vulnerable narcissistic traits.

Finally, the study revealed that self-concept clarity and self-esteem serve as mediators in the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety. The findings of this study support the hypothesized model. These results suggest that individuals with higher levels of vulnerable narcissism experience heightened social anxiety due to their ambiguous self-concept and diminished overall self-evaluation. In other words, individuals with a propensity for vulnerable narcissism struggle to comprehend and define themselves, leading to reduced levels of self-awareness and increased interpersonal anxiety. Vulnerable narcissism, also known as maladaptive narcissism, not only contributes to social anxiety but also gives rise to various emotional and behavioral challenges. It is important to note that intervening in vulnerable narcissism, which is a personality trait resistant to change, poses difficulties in achieving immediate transformations through short-term therapeutic interventions.

Therefore, in order to mitigate social anxiety, indirect approaches can be considered. Self-concept clarity and self-esteem are facets of overall self-perception that can be relatively easily modified through intervention. Social anxiety is a prominent emotional characteristic during adolescence and effective interventions can be achieved through psychological therapy or counseling [53–55].

The present study examines the influence mechanism of self-concept clarity and self-esteem on implicit narcissism and social anxiety, thereby enhancing the theoretical foundation of social anxiety. It is noteworthy that self-esteem and self-concept clarity are intricately linked to the developmental characteristics of adolescents, providing a more comprehensive explanation for adolescent social anxiety in real-life contexts. Adolescence is a pivotal period for the development and formation of personality. By examining the correlation between vulnerable narcissism and social anxiety among adolescents, we can analyze behavioral patterns and mitigate factors contributing to social anxiety. Strengthening education on self-esteem and fostering clarity of self-concept in teenagers can effectively reduce manifestations of social anxiety, while also emphasizing the significance of mental health education within educational institutions and among parents. Furthermore, investigating the efficacy of group counseling interventions can offer valuable insights into addressing and treating social anxiety.

Limitations and future research

This study also has certain limitations. Future research could obtain more precise data from actual clinical groups and re-validate the findings by including adolescent clinical groups from different regions and age levels as subjects, thereby enhancing the potential for generalization. Furthermore, the limited scope of research content hinders a comprehensive exploration and analysis of the intricate relationship between implicit narcissism and social anxiety, particularly in terms of dynamic observations on self-esteem levels and self-concept clarity. To delve deeper into this subject matter, future studies could incorporate longitudinal investigations and intervention programs.

In summary, the vulnerable narcissism of adolescents can not only directly contribute to social anxiety but also indirectly affect it through the separate mediating roles of self-concept clarity and self-esteem. To improve teenagers’ social skills and promote their overall well-being, it is crucial for families, schools, and society to recognize the importance of interpersonal abilities. Efforts should be made to boost self-esteem, foster a healthy self-image, and encourage self-acceptance. Educators and parents should assist adolescents with implicit narcissistic tendencies in cultivating a well-defined self-concept and self-identity, as these are crucial factors that can contribute to the mitigation of social anxiety within interpersonal relationships.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank all the participants who participated in the study and all the research team members who supported the completion of the study.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31960181, 32360213 and 82260364).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, W.Y. and D.X.; methodology, W.Y. and Y.X.; formal analysis, Y.X. and L.L.; data curation, L.L. and W.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Y. and L.X.; writing—review and editing, D.X. and L.X.; funding acquisition, D.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University (IRB No. 20221022). All participants in the study signed informed consent forms.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Caouette JD, Guyer AE. Gaining insight into adolescent vulnerability for social anxiety from developmental cognitive neuroscience. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2014;8:65–76. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2013.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Krygsman A, Vaillancourt T. Elevated social anxiety symptoms across childhood and adolescence predict adult mental disorders and cannabis use. Compr Psychiat. 2022;115:05–152302. [Google Scholar]

3. Fernández RS, Pedreira ME, Boccia MM, Kaczer L. Commentary: forgetting the best when predicting the worst preliminary observations on neural circuit function in adolescent social anxiety. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1088–90. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Masters M, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Farrell LJ, Modecki KL. Coping and emotion regulation in response to social stress tasks among young adolescents with and without social anxiety. Appl Dev Sci. 2023;27(1):18–33. doi:10.1080/10888691.2021.1990060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Pechorro P, Ayala-Nunes L, Nunes C, Marôco J, Gonçalves RA. The social anxiety scale for adolescents: measurement invariance and psychometric properties among a school sample of Portuguese youths. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016;47(6):975–84. doi:10.1007/s10578-016-0627-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Pontillo M, Guerrera S, Santonastaso O, Tata MC, Averna R, Vicari S, et al. An overview of recent findings on social anxiety disorder in adolescents and young adults at clinical high risk for psychosis. Brain Sci. 2017;7(10):1–9. [Google Scholar]

7. Stolz T, Schulz A, Krieger T, Vincent A, Urech A, Moser C, et al. A mobile app for social anxiety disorder: a three-arm randomized controlled trial comparing mobile and pc-based guided self-help interventions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86(6):493–504. doi:10.1037/ccp0000301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Coelho VA, Romão AM. The relation between social anxiety, social withdrawal and (cyber) bullying roles: a multilevel analysis. Comput Human Behav. 2018;86:218–26. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Prieto JM, Sánchez JS, Cordón JT, Álvarez-Kurogi L, González- García H, López RC. Social anxiety and academic performance during COVID-19 in schoolchildren. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280194-e0280194. [Google Scholar]

10. Weymouth BB, Buehler C. Early adolescents’ relationships with parents, teachers, and peers and increases in social anxiety symptoms. J Fam Psychol. 2018;32(4):496–506. doi:10.1037/fam0000396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. de Vente W, Majdandi M, Bögels SM. Intergenerational transmission of social anxiety in childhood through fear of negative child evaluation and parenting. Cognit Ther Res. 2022;46(6):1113–25. doi:10.1007/s10608-022-10320-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pilkionienė I, Širvinskienė G, Žemaitienė N, Jonynienė J. Social anxiety in 15-19 year adolescents in association with their subjective evaluation of mental and physical health. Children. 2021;8(9):737–7. doi:10.3390/children8090737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Leigh E, Clark DM. Understanding social anxiety disorder in adolescents and improving treatment outcomes: applying the cognitive model of clark and wells. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2018;21(3):388–414. doi:10.1007/s10567-018-0258-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Mun YJ, Choi ES. Influence of adolescents’ covert narcissism on their social networking service addiction tendency: examining the mediating effect of social anxiety and quality of peer relationships. Korean J Youth Stud. 2020;27(7):77–108. doi:10.21509/KJYS.2020.07.27.7.77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dickinson KA, Pincus AL. Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and volnerable narcissism. J Pers Disord. 2003;17(3):188–207. doi:10.1521/pedi.17.3.188.22146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Miller JD, Lynam DR, Hyatt CS, Campbell WK. Controversies in narcissism. Educ Res Q, Annu Rev Clini Psychol. 2017;13(1):291–315. [Google Scholar]

17. Rose P. The happy and unhappy faces of narcissism. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;33(3):379–92. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00162-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rohmann E, Hanke S, Bierhoff H. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in relation to life satisfaction, self-esteem, and self-construal. J Individ Differ. 2019;40(4):194–203. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Cain NM, Pincus AL, Ansell EB. Narcissism at the crossroads: phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(4):638–56. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Brown AA, Freis SD, Carroll PJ, Arkin RM. Perceived agency mediates the link between the narcissistic subtypes and self-esteem. Pers Individ Dif. 2016;90:124–9. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gu X, Hyun M. The associations of covert narcissism, self-compassion, and shame focused coping strategies with depression. Soc Behav Pers. 2021;49(6):1–15. doi:10.2224/sbp.10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Choi IS, Choi HN. The influences of covert narcissism on social anxiety: the mediating effects of internalized shame and social self-efficacy. Korean J Counsel. 2013;14(5):2799–2815. doi:10.15703/kjc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Brookes J. The effect of overt and covert narcissism on self-esteem and self-efficacy beyond self-esteem. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;85:172–5. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Son EG, Kwon HS. The relationship between covert narcissism and social anxiety of university students: the mediating effect of self-concept clarity. Youth Facil Environ. 2014;12(4):153–61. [Google Scholar]

25. No GE, Lee SY. The relations between covert narcissism and internet overuse: mediating effects of self-concept clarity and social anxiety. Korean J School Psychol. 2016;13(1):205–25. doi:10.16983/kjsp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Iwahori M, Oshiyama C, Matsuzaki H. A quasi-experimental controlled study of a school-based mental health programme to improve the self-esteem of primary school children. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022;9(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

27. Pan Z, Zhang D, Hu T, Pan Y. The relationship between psychological Suzhi and social anxiety among Chinese adolescents: the mediating role of self-esteem and sense of security. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12(50). [Google Scholar]

28. Oh HY, Park K. The mediation effects of shame between covert narcissism and social anxiety. Korean J Youth Stud. 2017;24(1):335–54. doi:10.21509/KJYS.2017.01.24.1.335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bae YR, Sung SY. The relationship between covert narcissism and school life adaptation in adolescents: the mediating effects of social anxiety and academic self-efficacy. J Korea Contents Assoc. 2019;19(3):89–99. [Google Scholar]

30. Choi MK, Kim JN. Moderating effect of adolescent resilience on the relationship between narcissistic tendency and interpersonal problems. Korean J Health Psychol. 2010;15(4):747–63. doi:10.17315/kjhp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Jung CS. The influence of adolescent narcissism on interpersonal relationships: focusing on the mediating effect of self-concept clarity. J Korea Academia-Indust Coop Soc. 2020;21(7):564–76. [Google Scholar]

32. Wu X, Wei DT, Zhang M, Qiu J, Zhao YF. Self-concept clarity is predicted by amygdala: evidence from a VBM study. Chin Sci Bull. 2017;62(13):1377–85. doi:10.1360/N972016-01003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Moscovitch DA. What is the core fear in social phobia? A new model to facilitate individualized case conceptualization and treatment. Cogn Behav Pract. 2008;16(2):123–34. [Google Scholar]

34. Wilson JK, Rapee RM. Self-concept certainty in social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):113–36. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Campbell WK, Sedikides C. Self-threat magnifies the self-serving bias: a meta- analytic integration. Rev Gen Psychol. 1999;3(1):23–43. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.3.1.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):218–26. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Ellison WD, Gillespie ME, Trahan AC. Individual differences and stability of dynamics among self-concept clarity, impatience, and negative affect. Self Identity. 2020;19(3):324–45. doi:10.1080/15298868.2019.1580217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kong F, Lan N, Zhang H. How does social anxiety affect mobile phone dependence in adolescents? The mediating role of self-concept clarity and self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2021;41:8070–7. [Google Scholar]

39. Park JY, Kim JE, Keum C. Effects of covert narcissism on social anxiety: the mediating effects of self concept clarity and rejection sensitivity. J Asia Pac Couns. 2022;12(1):97–115. doi:10.18401/2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kusec A, Tallon K, Koerner N. Intolerance of uncertainty, causal uncertainty, causal importance, self-concept clarity and their relations to generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2016;45(4):307–23. doi:10.1080/16506073.2016.1171391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Richman SB, Pond RS, Dewall CN, Kumashiro M, Slotter EB, Luchies LB. An unclear self leads to poor mental health: self- concept confusion mediates the association of loneliness with depression. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2016;35(7):525–50. doi:10.1521/jscp.2016.35.7.525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Whatley MA, Wasieleski DT, Breneiser JE, Wood MM. Understanding academic entitlement: gender classification, self-esteem, and covert narcissism. Educ Res Q. 2019;42(3):49–71. [Google Scholar]

43. Lohr SL. Sampling: Design and analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

44. Zheng Y, Huang L. Overt and covert narcissism: a psychological exploration of narcissistic personality. J Psychol Sci. 2005;28(5):1259–62. [Google Scholar]

45. Niu GF, Sun XJ, Zhou ZK, Tian Y, Liu QQ, Lian SL. The effect of adolescents’ social networking site use on self-concept clarity: the mediating role of social comparison. J Psychol Sci. 2016;39(1):97–102. [Google Scholar]

46. Wang MC, Cai BG, Wu Y, Dai XY. The factor structure of chinese Rosenberg’ self-esteem scale affected by item statement method. Psychol Explor. 2010;30(3):63–8. [Google Scholar]

47. Ranta K, Junttila N, Laakkonen E, Uhmavaara A, Greca AML, Päivi MN. Social anxiety scale for adolescents (SAS-Ameasuring social anxiety among finish adolescents. Child Psychiatry & Hum Dev. 2012;43(4):574–91. doi:10.1007/s10578-012-0285-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Ran G, Zhang Q, Huang H. Behavioral inhibition system and self-esteem as mediators between shyness and social anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:568–73. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Heasuk Y, Jongun K. Analysis of the Structural relationships among cognitive flexibility, self-esteem, overt narcissism, covert narcissism and psychological well-being of general high school students. Korean Assoc Learn-Cent Curric Instr. 2019;19(7):161–84. doi:10.22251/jlcci. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Steinberg L. Adolescence. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010. [Google Scholar]

51. Xiang GC, Li QQ, Li XB, Chen H. Development of self-concept clarity from ages 11 to 24: latent growth models of Chinese adolescents. Self Identity. 2023;22(1):42–57. doi:10.1080/15298868.2022.2041478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hiller TS, Steffens MC, Ritter V, Stangier U. On the context dependency of implicit self-esteem in social anxiety disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiat. 2017;57(5):118–25. [Google Scholar]

53. Alden LE, Buhr K, Robichaud M, Trew JL, Plasencia ML. Treatment of social approach processes in adults with social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2018;86(6):505–17. [Google Scholar]

54. Hofmann SG. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: a comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cogn Behav Ther. 2007;36(4):193–209. doi:10.1080/16506070701421313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Rodebaugh TL, Tonge NA, Piccirillo ML. Does centrality in a cross-sectional network suggest intervention targets for social anxiety disorder? J Clin Psychol. 2018;86(10):831–44. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools