Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mediating Effect of Mindfulness, Self-Esteem and Psychological Resilience in the Relation between Childhood Maltreatment and Life Satisfaction

1 Beijing Huijia Private School, Beijing, 102299, China

2 Department of Psychology, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410081, China

3 School of Education, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, 411100, China

* Corresponding Author: He Zhong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Father/Mother Absence and Moral Emotion)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(6), 481-489. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.049408

Received 01 January 2024; Accepted 10 May 2024; Issue published 28 June 2024

Abstract

Childhood maltreatment, as a typical early adverse environment, is known to have a negative impact on one’s life satisfaction. Mindfulness, on the other hand, may serve as a protective factor. This study explored the mediating role of mindfulness and its related variables–positive thoughts, psychological resilience and self-esteem. In order to testify the mechanism, we administered Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) to a non-clinical sample of Chinese university students (N = 1021). The results indicated that positive thoughts did not mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction, but self-esteem (β = −0.194, 95% CI = [−0.090, −0.040]) and psychological resilience (β = −0.063, 95% CI = [−0.059, −0.020]) mediated the relationship, as well as the “mindfulness-self-esteem” (β = −0.061, 95% CI = [−0.287, −0.126]) and “mindfulness-psychological resilience” (β = −0.035, 95% CI = [−0.115, −0.034]). The results of this study were helpful to understand the relationship between childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction and provided a theoretical basis for the development of mindfulness intervention programs from the perspective of positive psychology.Keywords

Childhood maltreatment imposes psychological and physical harm on children through mental abuse or physical violence [1], which could profoundly impact the overall well-being of children in the long-term. Among its many negative consequences, childhood maltreatment significantly diminishes one’s life satisfaction [2,3], which includes an overall perception of life quality [4]. Despite the irreversible nature of childhood maltreatment, its adverse effects can be addressed by understanding the intervening mechanisms. Previous research suggests mindfulness was a key predictor of life satisfaction [5], while study also indicates childhood maltreatment can diminish individual mindfulness level [6]. Moreover, existing research lacks applications and practicality. Therefore, using the pain paradox and life-course frameworks, this study explores mindfulness as the critical intervention mechanism to understand the relationship between life satisfaction and childhood maltreatment. Additionally, it investigates the buffering effects of psychological resilience and self-esteem, which are two vital psychological resources related to life satisfaction. By shedding light on these dynamics, this research aims to inform the development of mindfulness-based intervention programs tailored to improve individual life satisfaction of the childhood maltreatment survivors, thereby fostering better psychological and physical health outcomes.

The relationship between childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction

Mindfulness, as a hot topic in positive psychology research, has received widespread attention from researchers recently [7,8]. The father of positive psychology, Seligman, also mentioned that mindfulness is one of the three major factors contributing to human happiness [9]. Defined as a positive and malleable psychological characteristic, mindfulness is understood as an awareness and acceptance internally and externally [10,11]. Moreover, when individuals are in a state of mindfulness, they adopt a non-judgmental attitude, focusing on whatever is happening in the present moment, whether it is psychological or physiological [12], they will less worry about future or past. Numerous studies have found that mindfulness, as a positive trait, contributes to factors beneficial for both mental and physical health, such as self-efficacy [13,14] and perceived social support [15]. Additionally, many studies have shown that mindfulness inhibits factors that can damage mental or physical health, such as depression [16], substance abuse [17], and anxiety [18]. Furthermore, although mindfulness is considered a psychological trait, many studies suggest that it is not static, such as mindfulness training can enhance levels of mindfulness, thereby increasing individual happiness [19,20], for example, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) derived from meditation practices [12]. Importantly, as mindfulness-based therapeutic approaches become more prevalent, they are increasingly being incorporated into traditional medicine and psychology [21]. Thus, from the scope of positive psychology and the protective role of mindfulness, this study aims to explore whether mindfulness can serve as an intervention mechanism in affecting the relation between early childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction.

Under the framework of the pain paradox, mindfulness may serve as a mediator between childhood mistreat and individual life satisfaction [22]. According to this theory, individuals who have undergone childhood maltreatment tend to adopt dissociative behaviors that can reduce tension to avoid pain, which is precisely the opposite of mindfulness. Moreover, these may become persistent and maintained through processes of conditioning (including negative reinforcement) in one’s coping strategies [23]. These avoidant responses to stress and adversity may impede the psychological processing of trauma-related effects, thus imparing the life satisfaction of the survivors [24]. This is because childhood maltreatment, as one of the factors negatively affecting individual mental and physical health, often leads victims to dwell on past painful experiences [25,26], rather than focusing on the present. Additionally, parental abusive behaviors can lead to the formation of various biases [27]. All of these factors may contribute to a decrease in positive thinking. Individuals lacking positive thinking tend to engage in habitual negative thoughts and cognitions [28], thereby perceiving lower levels of life satisfaction [29]. These factors may all contribute to a decrease in mindfulness levels. Therefore, we postulate childhood maltreatment may impact life satisfaction through its influence on mindfulness.

The mediating role of psychological resilience and self-esteem

According to the life course framework, Pearlin et al. elucidated how the influence of stress factors unfolds over time [30]. Stress and abuse experiences during childhood may lead to depletion of self-related resources, which persists and spreads throughout a person’s life. Based on this model, research found that childhood maltreatment can damage self-related resources such as self-esteem and psychological resilience, indirectly influencing various outcomes in adulthood [31,32]. Self-esteem refers to one’s perception of self-worth [33]. Psychological resilience defines as one’s capability to cope with life stress or trauma [34]. These two self-related concepts may be directly influenced by childhood maltreatment. Individuals who have experienced childhood maltreatment often internalize the way caregivers treated them and hold negative views about themselves, thus affirming the negative messages received from caregivers, leading to decreased levels of psychological resilience and self-esteem [35]. Impaired self-related resources become secondary stressors, with their adverse effects extending from childhood into adulthood and continuously affecting life satisfaction [36,37]. Moreover, the core factor of this study—mindfulness—is closely associated with these two variables [38–40]. Studies found that mindfulness can influence life satisfaction through its impact on self-esteem [41] or through its effect on psychological resilience [42]. Therefore, the “mindfulness-self-esteem” and “mindfulness-psychological resilience” pathways may serve as two mediating mechanisms between the two variables.

Previous research suggested a higher prevalence of childhood maltreatment exists among females than males. Females are more likely to experience maltreatment during childhood compared to males [43,44]. Moreover, the influence of an early adverse environment on one is significantly different between females and males. For instance, Godinet et al. found that the impact of childhood maltreatment on problem behaviors is more severe in males [45]. Gallo et al. demonstrated that childhood maltreatment has a greater impact on females related to depression and anxiety [46]. Additionally, Doom et al. suggested that the physiological effects of childhood maltreatment on different genders are different [47]. Therefore, based on this evidence, we posit that there may be gender differences in various pathways of early maltreatment in individuals.

The purpose of this study is to explore the mediating role of mindfulness and the chain mediating role of mindfulness, psychological resilience and self-esteem between childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction from the scope of positive psychology. Based on these, the following three hypotheses are proposed: (1) Mindfulness serves as a significant mediator in this relationship; (2) Psychological resilience plays a significant mediating role in this relationship; (3) Self-esteem plays a significant mediating role in this relationship; (4) “Mindfulness-self-esteem” is chain mediating paths; (5) “Mindfulness-psychological resilience” is chain mediating paths; (6) Gender differences may exist in various pathways in this relationship.

The participants in this study were recruited from two universities in Hunan Province and two universities in Guangdong Province, China. After processing all the collected data (invalid or unfinished questionnaires were eliminated), 1021 complete data of participants were used in this research (315 from males, 706 from females). The mean age was 19.04 years (SD = 1.52), ranging from 17 to 26. Participants completed all questionnaires as required in a classroom or in a quiet environment. Each participant signed the informed consent form before the examination and received the participant fee as compensation at the end. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University (IRB number: 051).

Childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ)

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire was compiled by Bernstein et al. [48]. This questionnaire consists of 28 items (including 3 validity items). The 25 clinical items respectively describe five dimensions (abuse & emotional neglect, abuse and sexual abuse& physical neglect). Items such as, “I have to wear unsanitary clothes”, are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (5 = Always, 1 = Never). A higher final score shows the greater harm the individual received. In the present study, we adopted the Chinese local version [49]. Considering the cultural sensitivity of China, we deleted the dimensions of sexual abuse and kept the other 23 questions (including 3 validity items). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.827 in this study. The adjusted version of this questionnaire has both high reliability and validity [50].

The satisfaction with life scale (SWLS)

The Satisfaction with Life Scale was compiled by Diener et al. [51]. It consists of five items. Items such as, “In most days my life is consistent to my ideal”, are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (7 = Strongly agree, 1 = Strongly disagree). A higher final score indicated a higher life satisfaction. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.841 in this study. This scale has both high reliability and validity [52].

Mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS)

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale was compiled by Brown et al. [10]. It consists of 15 items. Items such as, “I might be experiencing some emotions and not be conscious of my emotion until later”, are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = Almost never, 6 = Almost always). A higher scale score shows a higher level of mindfulness. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.749 in this study. The scale has both high reliability and validity [53].

Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC)

Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale was compiled by Campbell-Sills et al. [54]. It consists of 10 items. Items such as, “I am able to adapt to change”, are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 6 = Strongly agree). A higher scale score shows a higher psychological resilience. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.879 in this study. The scale has both high reliability and validity [55].

Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES)

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was compiled by Rosenberg [56]. It consists of 10 items. Items such as, “I feel that I have many good qualities” and “Overall I am content with myself”, are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 4 = Strongly agree). The final score of the scale is based on the reverse coding of related items. A higher coded score represents a higher level of self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.882. The scale has both high reliability and validity [57].

To examine the mediating effects, structural equation model was used by Amos 26.0 program. We started with descriptive statistics to examine the correlation between variables. Later, we studied the measurement model to determine whether each latent variable under this model could be representative enough. If the measurement model fits well, we will build the structural model by using the chi-square statistic, standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR ≤ 0.080), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.080), and comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.900). Because those indicators can test the fitting degree of model [58], which means the better the fitting degree of the model is, the better fitness of this model by its indicators. Additionally, we will use bootstrap to examine whether the mediating effects were significant. Finally, a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to testify the stability of the model.

Data were all self-reported in this study, introducing the possibility of Common Method Bias (CMB). Necessary precautions were taken during the data collection process, such as explaining to our participants that the collected data would solely be used for scientific purposes and ensuring the anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents. To enhance the rigor of the study, we examined the method bias in the administered questionnaires, we carried out Harman’s single factor test after the completion of data collection [59]. Data results indicated that the number of factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 was 4, and the cumulative variance explained by these factors was 33.31%, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. This suggests no significant common method bias in the research data; therefore, our data is representative.

Descriptive statistics and measurement model

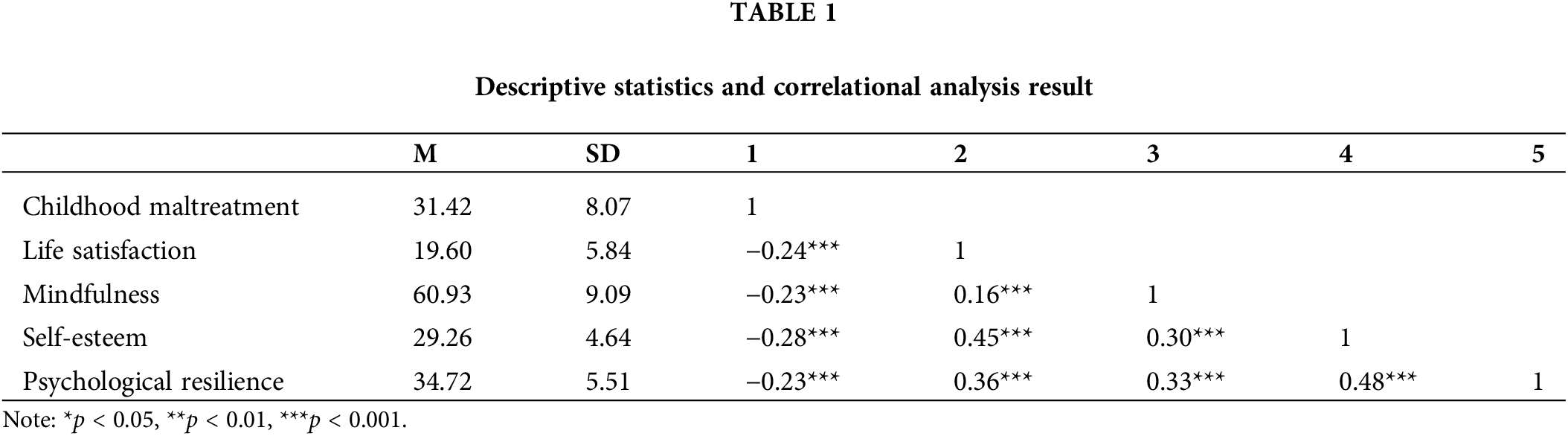

Five latent variables (e.g., childhood maltreatment, life satisfaction, mindfulness, psychological resilience, and self-esteem) and 14 observed variables were included and investigated in the measurement model. The results indicated both a good representativeness and fitness of this tool: χ2/df = 3.442, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.049; SRMR = 0.040; CFI = 0.975. All the factors that account for the indicators regarding the latent variables were significant, showing that all the latent variables were well-represented in their indicators. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for each latent variable. The variables below were significantly correlated (p < 0.001).

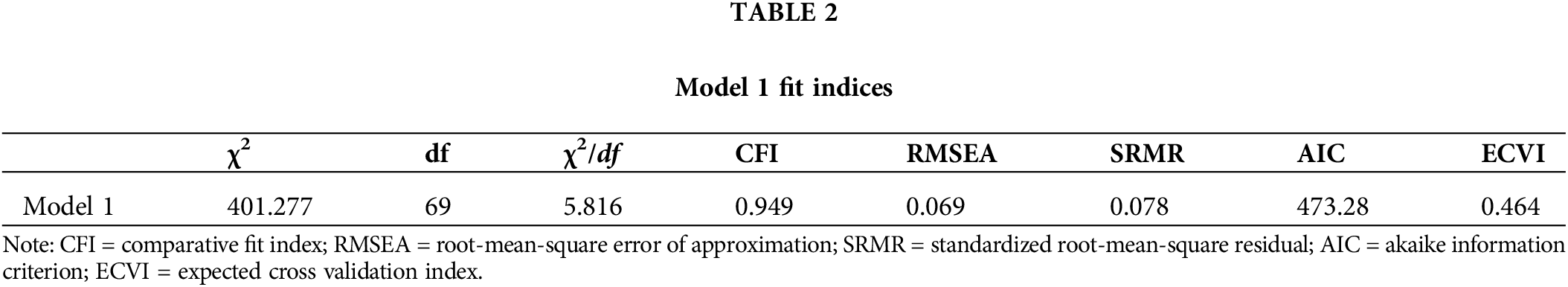

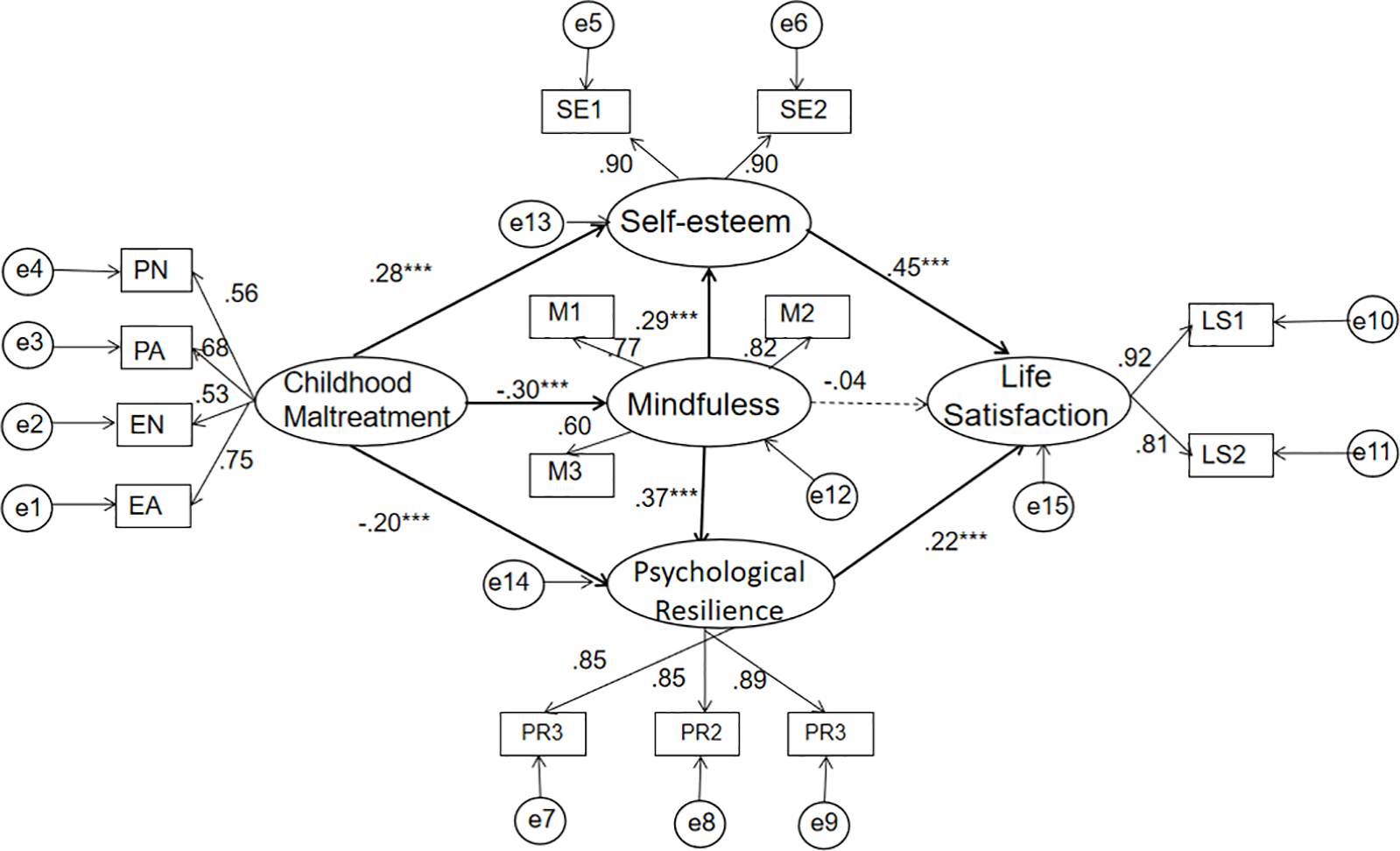

With the absence of mediating variables, childhood maltreatment significantly affects life satisfaction in a negative way (β = −0.172, p < 0.001). A structural model (Model 1) containing three mediators (mindfulness, self-esteem, psychological resilience) and two chain mediating paths (mindfulness-self-esteem, mindfulness-psychological resilience) was build. The results showed that Model 1 fitted: [χ2/df = 5.816, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.069; SRMR = 0.078; CFI = 0.949]. Therefore, Model 1 was selected as the structural model (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The chain mediation model.

Note: PN, PA, EN and EA are the four items of childhood maltreatment. M1, M2 and M3 are mindfulness parcels. LS1 and LS2 are Life satisfaction parcels. PR1, PR2 and PR3 are psychological resilience parcels. SE1 and SE2 are Self-esteem parcels. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

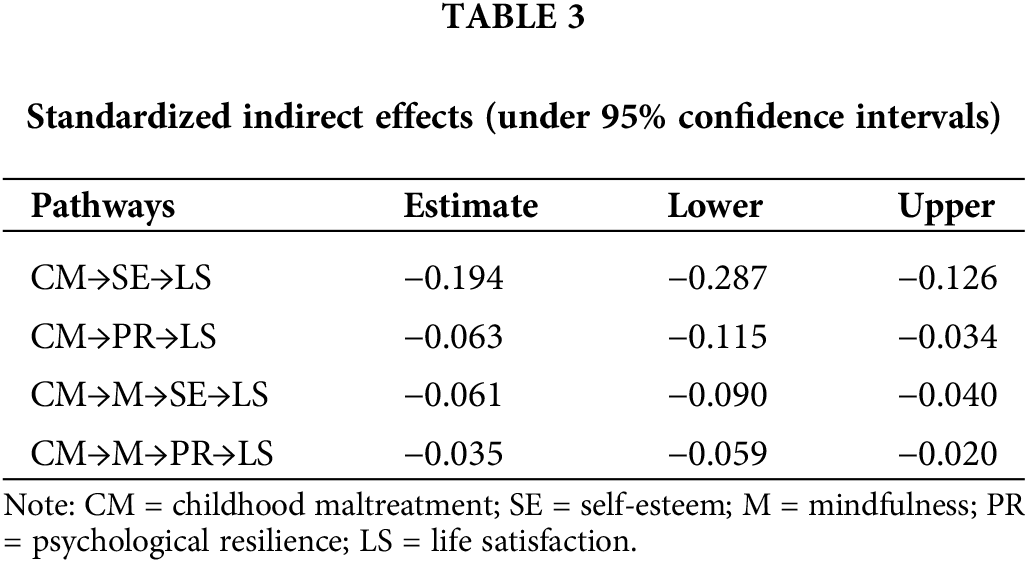

In order to test the significance of each mediation effect in the model, we used 2000 Bootstrap samples that were randomly extracted from the original data set (N = 1021). As predicted, the data results indicated that in the relation between childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction, the chain mediating paths of “mindfulness-self-esteem” (95% CI = [−0.090, −0.040]) and “mindfulness-psychological resilience” (95% CI = [−0.059, −0.020]) were significant. In addition, self-esteem (95% CI = [−0.287, −0.126]) and psychological resilience (95% CI = [−0.115, −0.034]) both played significant but independent mediating roles in this relationship (See Table 3).

In order to make our research results more stable, a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on Model 1. Firstly, we examined whether gender differences existed among the five latent variables. The results suggested no significant differences exist in mindfulness (t(1021) = 0.002, p = 0.998), self-esteem (t(1021) = 0.623, p = 0.973) and life satisfaction (t(1021) = −0.034, p = 0.534). However, the result found significant differences in psychological resilience (t(1021) = 2.896, p < 0.01) and childhood maltreatment (t(1021) = 2.271, p < 0.05). The scores of both men were higher than the scores of women.

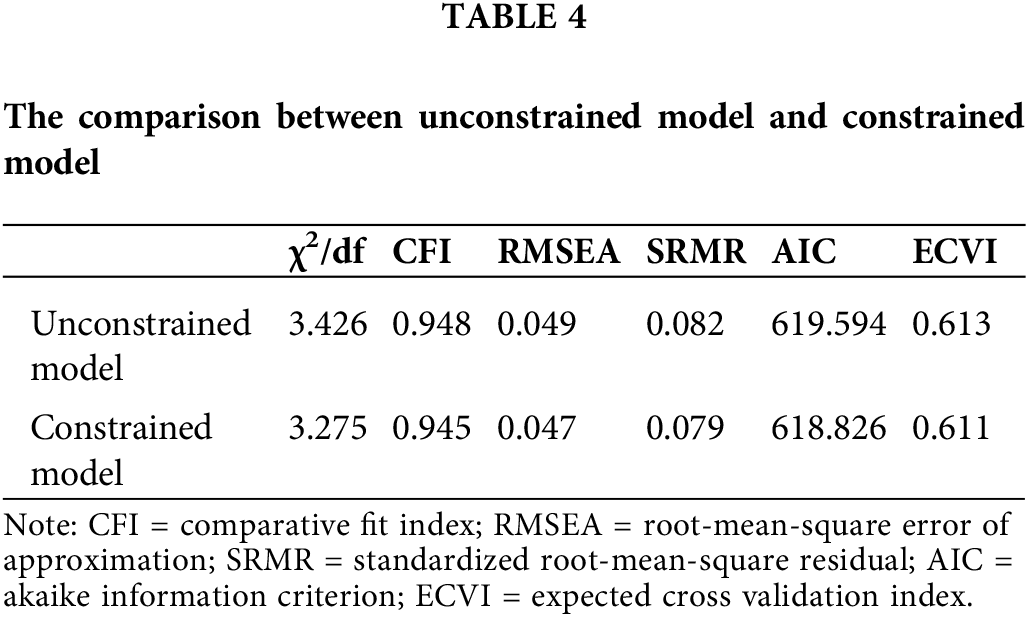

Regarding gender differences, we established two models according to the research of Byrne [60]. One is the Unconstrained model, and the other is the constrained model. The results suggested no significant difference between these two models (χ2(9,1021) = 16.317, p = 0.061). Meanwhile, both models’ fitting indexes have reached the fitness standard (See Table 4). In addition, regarding χ2 was easily affected by the sample size, Critical Ratios of Differences (CRD) was used to make the results more accurate to further examine the cross-gender stability of the model. The decision rule indicates that there is a significant difference between the two parameters because the absolute value of CRD exceeds 1.96 [61]. Therefore, the results suggested a huge gap across different genders in (CRDPR→LS = 3.775). Additionally, the direct impact of psychological resilience on life satisfaction was very weak in the male sample.

This study marks the first exploration from a positive psychology perspective on the mediating role of mindfulness in the relationship between early maltreatment and life satisfaction. It also examined the mediating roles of self-esteem and psychological resilience among the two variables. It overall suggests that childhood maltreatment directly affects life satisfaction through self-esteem or psychological resilience but does not directly impact life satisfaction through mindfulness. Remarkably, the results also indicate that the “mindfulness-self-esteem” and “mindfulness-psychological resilience” pathways play sequential mediating roles in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction.

As indicated by hypotheses (2) and (3), the results suggest that childhood maltreatment may influence life satisfaction through its impact on psychological resilience, a finding indirectly supported by previous research [62,63]. However, our multi-group confirmatory factor analysis revealed significant gender gaps in the relations. Additionally, females tend to exhibit higher levels of psychological resilience, implying that psychological resilience may have a greater impact on life satisfaction for females. This could be attributed to females potentially experiencing more emotional distress [64], making them more susceptible to decreased life satisfaction if their psychological resilience is low. Furthermore, it also suggests that males may derive more positive benefits from self-esteem rather than psychological resilience. However, concrete conclusions require further investigation. Additionally, childhood maltreatment may also affect life satisfaction through its influence on self-esteem, which is also supported by previous research [38].

Interestingly, the results indicate that mindfulness cannot directly alleviate the adverse impact of childhood maltreatment on life satisfaction, suggesting the invalidity of our hypothesis (1). Structural equation modeling results demonstrate a significant direct effect of childhood maltreatment on mindfulness, yet mindfulness does not significantly influence life satisfaction. We speculate that this could be because while mindfulness promotes present moment awareness, it may not directly enhance life satisfaction. Since life satisfaction involves an overall assessment of life, it is influenced by various factors. Thus, individuals not only need to overcome past influences but also require the ability and confidence to cope with current or future adversities, which mindfulness itself may not directly provide. Furthermore, mindfulness is not just a skill to cope with negative emotions but also a lifestyle and attitude. Its impact on life satisfaction may require time and long-term practice. Given that this study is cross-sectional, it may not capture the long-term effects of mindfulness. Therefore, in this study, mindfulness cannot directly influence individual life satisfaction. Additionally, these results contradict some previous studies. For instance, Bajaj et al. investigated the mediating role of psychological resilience between mindfulness and life satisfaction using the same tools as this study and found a significant direct impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction [39]. Similarly, Pepping et al. also found similar results [41]. Based on the findings of previous studies and our study, further research can be done to explore whether mindfulness can directly influence life satisfaction.

Furthermore, despite mindfulness not directly alleviating the harmful impact of childhood maltreatment, the results from Model 1 indicate that mindfulness still has a significant indirect protective effect. The findings suggest that the “mindfulness-self-esteem” and “mindfulness-psychological resilience” pathways serve as two consecutive mediating mechanisms between childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction. This may be because high levels of mindfulness can prevent individuals from dwelling on past adverse experiences [65,66], such as childhood maltreatment, indirectly promoting the development of survivors’ psychological resilience. Individuals with higher psychological resilience demonstrate better adaptability when facing current life setbacks [67,68], thereby enhancing their life satisfaction. Similarly, individuals who are more mindful about present are less likely to ruminate on past failures or negative experiences, making them more likely to indirectly maintain healthy levels of self-esteem. People with strong self-esteem demonstrate greater resilience when dealing with negative events in life [69], thereby also increasing their life satisfaction.

In conclusion, this study examined the impact of childhood maltreatment on life satisfaction and further investigated the mediating mechanisms of mindfulness, self-esteem, and psychological resilience. The research not only expands upon previous studies in related fields but also provides theoretical support for the use of mindfulness interventions to mitigate the negative impact of childhood maltreatment. Additionally, it suggests potential directions for future empirical research on mindfulness. The findings indicate that while mindfulness may not directly alleviate the negative impact of childhood maltreatment on life satisfaction, it can indirectly mitigate this impact through psychological resilience and self-esteem. Therefore, we believe that mindfulness will play a crucial role in clinical interventions for childhood maltreatment in the future. Future work and practice can investigate the practical effectiveness of mindfulness training in reducing the detrimental impact of childhood adverse experience.

This study the mediating role of mindfulness and explores the relations between childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction. However, there are still some limitations. Firstly, the data in this study were self-reported, which can be affected by social desirability bias or expectancy effect. It can affect the data accuracy. Future research could employ more objective methods or methods triangulation for holistic data collection. Secondly, the study utilized a cross-sectional design, allowing for preliminary inferences about the relationships between variables. However, to draw more definitive conclusions, longitudinal or experimental designs are needed. Thirdly, the participants in this study were all college students from China. Therefore, future research should expand to include participants from diverse cultural backgrounds and nationalities. Fourthly, there was a higher proportion of female participants in this study. Male and other gender minorities need to be investigated in order to increase population validity. Efforts will be made in future research to improve gender ratio and seek a more balanced sample distribution.

This study reveals the harmful effect of childhood maltreatment on individuals’ life satisfaction and its underlying mechanisms, deepen our understanding of the relationship between early adverse environments and child development. From an academic perspective, this study also extends the life course framework theory by demonstrating how childhood maltreatment affects life satisfaction through psychological resilience or self-esteem. Furthermore, this study further enhances our understanding of how early adverse environments affect individual life satisfaction through self-related resources. This research contributes to deepening our comprehension regarding the relations between early adverse environments and mental health, thereby facilitating further exploration in the field of child abuse and providing valuable insights into how early adverse environments could impact individual mental health.

Practically, this study provides valuable perspectives for exploring and intervening in the negative effects of early adversity. Mindfulness training can be utilized to enhance individuals’ psychological resilience and self-esteem, thereby mitigating to some extent the adverse impact of childhood mistreats and positively influencing individual mental health. This study offers practical recommendations for improving individual mental health in the development field.

Childhood maltreatment can influence individuals’ levels of mindfulness but cannot directly impact their life satisfaction through mindfulness. Meanwhile, childhood maltreatment can further influence individuals’ life satisfaction through psychological resilience and self-esteem. Further analysis suggests that childhood maltreatment can also affect individuals’ life satisfaction through the chain mediation of “mindfulness-self-esteem” and “mindfulness-psychological resilience.”

Acknowledgement: We thank all participants in this study for their cooperation and effort, all the members of our research group for data collection.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Project of National Education Scientific Planning Projects of China, DBA180316.

Author Contributions: He Zhong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. Yaping Zhou: Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. Chenwei, Liu: Data Collection, Conceptualization, Writing-Review & Editing. Yingtao Cao: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University (IRB number: 051). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Greengard J. The battered-child syndrome. Am J Nurs. 1964;64(6):98–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Arslan G. Psychological maltreatment, forgiveness, mindfulness, and internet addiction among young adults: a study of mediation effect. Comput Human Behav. 2017a;72(1):57–66. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. LaBrenz CA, Dell PJ, Fong R, Liu V. Happily ever after? Life satisfaction after childhood exposure to violence. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(13–14):NP6747–66. doi:10.1177/0886260518820706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Pavot W, Diene E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5(2):164–72. [Google Scholar]

5. Cheung RY, Lau ENS. Is mindfulness linked to life satisfaction? Testing savoring positive experiences and gratitude as mediators. Front Psychol. 2021;12:591103. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.591103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Joss D, Khan A, Lazar SW, Teicher MH. A pilot study on amygdala volumetric changes among young adults with childhood maltreatment histories after a mindfulness intervention. Behav Brain Res. 2021;399:113023. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2020.113023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Belschner L, Lin SY, Yamin DF, Best JR, Edalati K, McDermid J, et al. Mindfulness-based skills training group for parents of obsessive-compulsive disorder-affected children: a caregiver-focused intervention. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39(2011):101098. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Birtwell K, Dubrow-Marshall L, Dubrow-Marshall R, Duerden T, Dunn A. A mixed methods evaluation of a mindfulness-based stress reduction course for people with Parkinson’s disease. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2017;29(12):220–8. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.10.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Seligman ME. Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. Atrial Books; 2004. [Google Scholar]

10. Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol Inq. 2007;18(4):211–37. doi:10.1080/10478400701598298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 1992;4(1):33–47. doi:10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Sharma PK, Kumra R. Relationship between mindfulness, depression, anxiety and stress: mediating role of self-efficacy. Pers Individ Diff. 2022;186(9):111363. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2021.111363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Moniz-Lewis DI, Stein ER, Bowen S, Witkiewitz K. Self-efficacy as a potential mechanism of behavior change in mindfulness-based relapse prevention. Mindfulness. 2022;13(9):2175–85. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02428-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wilson JM, Weiss A, Shook NJ. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and savoring: factors that explain the relation between perceived social support and well-being. Pers Individ Diff. 2020;152(5):109568. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Johannsen M, Nissen ER, Lundorff M, O’Toole MS. Mediators of acceptance and mindfulness-based therapies for anxiety and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;94(4–5):102156. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Ramadas E, Lima MPD, Caetano T, Lopes J, Dixe MDA. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based relapse prevention in individuals with substance use disorders: a systematic review. Behav Sci. 2021;11(10):133. doi:10.3390/bs11100133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Papenfuss I, Lommen MJ, Grillon C, Balderston NL, Ostafin BD. Responding to uncertain threat: a potential mediator for the effect of mindfulness on anxiety. J Anxiety Disord. 2021;77(4–5):102332. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Aikens KA, Astin J, Pelletier KR, Levanovich K, Baase CM, Park YY, et al. Mindfulness goes to work. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(7):721–31. doi:10.1097/jom.0000000000000209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Buckner JD, Lewis EM, Abarno CN, Heimberg RG. Mindfulness training for clinically elevated social anxiety: the impact on peak drinking. Addict Behav. 2020;104:106282. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Moore A, Malinowski P. Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Conscious Cogn. 2009;18(1):176–86. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Myers IJ, Berliner L, Briere J, Hendrix CT, Reid T, Jenny C. Treating adult survivors of severe childhood maltreatment and neglect: Further development of an integrative model. In: Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, Hendrix CT, Reid T, Jenny C, editors. The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

23. Briere J. Pain and suffering: a synthesis of Buddhist and Western approaches to trauma. 2015. Available from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2015-10559-001. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

24. Morissette Harvey F, Paradis A, Daspe MÈ., Dion J, Godbout N. Childhood trauma and relationship satisfaction among parents: a dyadic perspective on the role of mindfulness and experiential avoidance. Mindfulness. 2023;15:310–26. doi:10.1007/512671-023-02262-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. McLafferty M, O’Neill S, Armour C, Murphy S, Ferry F, Bunting B. The impact of childhood adversities on the development of Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the Northern Ireland population. Eur J Trauma Dissoc. 2019;3(2):135–41. doi:10.1016/j.ejtd.2018.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mirhashem R, Allen HC, Adams ZW, van Stolk-Cooke K, Legrand A, Price M. The intervening role of urgency on the association between childhood maltreatment, PTSD, and substance-related problems. Addict Behav. 2017;69(3):98–103. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Davis JS, Fani N, Ressler K, Jovanovic T, Tone EB, Bradley B. Attachment anxiety moderates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and attention bias for emotion in adults. Psychiatry Res. 2014;217(1–2):79–85. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Verplanken B, Friborg O, Wang CE, Trafimow D, Woolf K. Mental habits: metacognitive reflection on negative self-thinking. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(3):526. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kong F, Wang X, Zhao J. Dispositional mindfulness and life satisfaction: the role of core self-evaluations. Pers Individ Diff. 2014;56(3):165–9. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC. Stress, health, and the life course: some conceptual perspectives. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(2):205–19. doi:10.1177/002214650504600206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. He N, Xiang Y. Child maltreatment and nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: the mediating effect of psychological resilience and loneliness. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2022;133(1):106335. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang H, Wang W, Liu S, Feng Y, Wei Q. A meta-analytic review of the impact of child maltreatment on self-esteem: 1981 to 2021. Trauma, Violence, Abuse. 2023;24(5):3398–411. doi:10.1177/15248380221129587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Leary MR, Baumeister RF. The nature and function of self-esteem: sociometer theory. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2000;32:1–62. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(00)80003-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543–62. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ju S, Lee Y. Developmental trajectories and longitudinal mediation effects of self-esteem, peer attachment, child maltreatment and depression on early adolescents. Child Abuse Neglect. 2018;76(5):353–63. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zheng W, Huang Y, Fu Y. Mediating effects of psychological resilience on life satisfaction among older adults: a cross-sectional study in China. Health Soc Care Commun. 2020;28(4):1323–32. doi:10.1111/hsc.12965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Greger HK, Myhre AK, Klöckner CA, Jozefiak T. Childhood maltreatment, psychopathology and well-being: the mediator role of global self-esteem, attachment difficulties and substance use. Child Abuse Neglect. 2017;70(1):122–33. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bajaj B, Robins RW, Pande N. Mediating role of self-esteem on the relationship between mindfulness, anxiety, and depression. Pers Individ Diff. 2016;96(1):127–31. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Dong X, Xiang Y, Zhao J, Li Q, Zhao J, Zhang W. How mindfulness affects benign and malicious envy from the perspective of the mindfulness reperceiving model. Scand J Psychol. 2019. doi:10.1111/sjop.12596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Randal C, Pratt D, Bucci S. Mindfulness and self-esteem: a systematic review. Mindfulness. 2015;6(6):1366–78. doi:10.1007/s12671-015-0407-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Pepping CA, O’Donovan A, Davis PJ. The positive effects of mindfulness on self-esteem. J Posit Psychol. 2013;8(5):376–86. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.807353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Bajaj B, Pande N. Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Pers Individ Diff. 2016;93(7):63–7. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Moody G, Cannings-John R, Hood K, Kemp A, Robling M. Establishing the international prevalence of self-reported child maltreatment: a systematic review by maltreatment type and gender. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1164. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6044-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Knaul FM, Bustreo F, Horton R. Countering the pandemic of gender-based violence and maltreatment of young people: the lancet commission. Lancet. 2020;395(10218):98–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33136-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Godinet MT, Li F, Berg T. Early childhood maltreatment and trajectories of behavioral problems: exploring gender and racial differences. Child Abuse Neglect. 2014;38(3):544–56. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gallo EAG, Munhoz TN, de Mola CL, Murray J. Gender differences in the effects of childhood maltreatment on adult depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Neglect. 2018;79(3):107–14. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Doom JR, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Dackis MN. Child maltreatment and gender interactions as predictors of differential neuroendocrine profiles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(8):1442–54. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.12.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogged D, Handelsman L. Validity of the childhood trauma questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):340–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

49. Zhao X, Zhang Y, Li L, Zhou Y. Evaluation on reliability and validity of Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2005;9(20):105–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

50. Xiang Y, Cao Y, Dong X. Childhood maltreatment and moral sensitivity: an interpretation based on schema theory. Pers Individ Diff. 2020;160(3):109924. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.109924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–5. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Song G, Kong F, Jin W. Mediating effects of core self-evaluations on the relationship between social support and life satisfaction. Soc Indic Res. 2012;114(3):1161–9. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0195-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Bao X, Xue S, Kong F. Dispositional mindfulness and perceived stress: the role of emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Diff. 2015;78:48–52. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISCvalidation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–28. doi:10.1002/jts.20271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Kong F, Wang X, Hu S, Liu J. Neural correlates of psychological resilience and their relation to life satisfaction in a sample of healthy young adults. Neuroimage. 2015;123:165–72. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.08.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

57. Kong F, You X. Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Soc Indic Res. 2011;110(1):271–9. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int J Test. 2001;1(1):55–86. doi:10.1207/s15327574ijt0101_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Zhou H, Long L. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;(6):942–50. [Google Scholar]

60. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. London: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

61. Arbuckle JL. AMOS 5.0 update to the AMOS user’s guide. Chicago IL: Smallwaters; 2003. [Google Scholar]

62. Abolghasemi A, Varaniyab ST. Resilience and perceived stress: predictors of life satisfaction in the students of success and failure. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5(3):748–52. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Arslan G. Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: the mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse Neglect. 2016;52(1):200–9. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.09.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Saddique A, Chong SC, Almas A, Anser M, Munir S. Impact of perceived social support, resilience, and subjective well-being on psychological distress among university students: does gender make a difference. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2021;11(1):528–42. doi:10.6007/IJARBSS/V11-I2/8331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Rehman AU, You X, Wang Z, Kong F. The link between mindfulness and psychological well-being among university students: the mediating role of social connectedness and self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(14):11772–81. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02428-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Caltabiano G, Martin G. Mindless suffering: the relationship between mindfulness and non-suicidal self-injury. Mindfulness. 2016;8(3):788–96. doi:10.1007/s12671-016-0657-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience. Eur Psychol. 2013;18(1):12–23. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Wallace KA. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(4):730–49. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Li J, Chen YP, Zhang J, Lv MM, Välimäki M, Li YF, et al. The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem between life events and coping styles among rural left-behind adolescents in China: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiat. 2020;11:560556. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.560556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools