Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Social Phobia among College Students: The Mediating Effect of Fear of Negative Evaluation and the Moderating Effect of Perfectionism

1 School of Modern Logistics, Qingdao Harbor Vocational and Technical College, Qingdao, 266404, China

2 Institute of Education, Xiamen University, Xiamen, 361005, China

3 Shandong Social Science Education Base, Yantai Nanshan University, Longkou, 265706, China

4 School of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, 266555, China

5 Tan Kah Kee College, Xiamen University, Zhangzhou, 363105, China

* Corresponding Author: Hui Wang. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(6), 491-498. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.048917

Received 21 December 2023; Accepted 18 April 2024; Issue published 28 June 2024

Abstract

Objectives: To explore the relationship between college students’ self-esteem (SE) and their social phobia (SP), as well as the mediating role of fear of negative evaluation (FNE) and the moderating effect of perfectionism. Methods: A convenience sampling survey was carried out for 1020 college students from Shandong Province of China, utilizing measures of college students’ self-esteem, fear of negative evaluation, perfectionism, and social phobia. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS PROCESS macro. Results: (1) college students’ self-esteem significantly and negatively predicts their social phobia (β = −0.31, t = −10.10, p < 0.001); (2) fear of negative evaluation partially mediates the relation between self-esteem and social phobia among college students, with the mediating effect accounting for 48.97% of the total effect (TE); (3) the mediating role of fear of negative evaluation is moderated by perfectionism (β = 0.18, t = 7.75, p < 0.001), where higher levels of perfectionism strengthen the mediating effect of fear of negative evaluation. Conclusions: Perfectionism moderates the mediating effect that fear of negative evaluation plays, establishing a moderated mediating model.Keywords

Social phobia (SP), frequently considered as social anxiety disorder, is featured with a substantially enduring fear that arises in certain social contexts where the individual might encounter new people or be under the observation of others [1]. There was an overlap between social anxiety and social phobia, which were not fundamentally different but rather a continuum of social evaluation concerns, ranging from mild to extreme degrees. Along this continuum, shyness occupied a lower end, social anxiety was in the middle, social phobia stood at a higher end, and avoidant personality disorder was at the extreme end [2]. Individuals’ increased levels of social anxiety led to social phobia. Social phobia significantly affected an individual’s psychological and physiological functioning [3]. Studies have shown that people suffering from social phobia display increased anxiety levels [4], depression rates [5], substance abuse [6], as well as notable limitations in socialization [7] and career development issues [8].

Social phobia had a higher prevalence within populations, particularly among college students, where this phenomenon became more prominent. Most individuals had experienced varying degrees of social anxiety at some stage in life, though some may not have reached the level of social phobia but still encountered elevated levels of social anxiety. Studies reported that over 13% of individuals, at some point in their lives, met the diagnostic criteria for social phobia [9]. The onset of social phobia typically occurred during adolescence or early adulthood [10–12], and college students fell within this age range, making them a high-risk group for social phobia. Social phobia could impede college students’ social interactions, significantly impacting their relationships, learning, and employment. In extreme cases, it could hinder their subjective sense of well-being [13,14]. Therefore, exploring the influencing factors and the mechanisms behind the development of social phobia in college students is an essential concern for researchers. Relevant studies hold significant importance in preventing and intervening in college students’ social phobia.

College students’ self-esteem (SE) and social phobia (SP)

Significant research attention has been given to identifying risk factors linked to social phobia, revealing that self-esteem serves as a protective element against social phobia among college students [15–18]. Self-esteem is generally represented as a kind of comprehensive emotional judgment and experience of individuals, reflecting in the attitudes and evaluations they hold about themselves [19]. From a psychodynamic perspective, the core of social phobia lies in the fear of others harming one’s self-esteem, leading individuals to employ various methods to protect it. For instance, avoiding public speaking or eye contact serves as a means of safeguarding and defense of self-esteem [20,21]. When individuals possess higher self-esteem, their self-evaluations are more positive, and they exhibit a more favorable self-attitude, being less concerned about potential harm to their self-esteem by others [22]. Conversely, people with lower SE have lower self-evaluations, likely to employ various methods to protect their SE, leading to manifestations such as fear of public speaking, characteristic of SP. Previous surveys suggested students with lower SE experienced a greater prevalence of social phobia compared with their counterparts with higher self-esteem [23]. Additionally, during the treatment of social phobia, lower self-esteem might have reduced the likelihood of treatment success [24]. Therefore, we propose hypothesis 1: college students’ self-esteem negatively predicts their social phobia.

About the mediating effect of fear of negative evaluation (FNE)

How does college students’ self-esteem predict their social phobia? The Cognitive Behavioral Model of Social Anxiety Disorder (SADCBM) pointed out that SP stems from individuals’ assessments of their intention of negative evaluation in social situations [25]. Those with SP anticipated negative evaluations from others [26], and these anticipated negative evaluations further trigger anxiety, leading to the formation of SP [2]. Therefore, fear of negative evaluation (FNE) exerts some pivotal effect on individuals’ emergence of SP. FNE denotes the fearful expectation or anticipation individuals have towards the possibility of receiving unfavorable judgments from others in social contexts [27]. Studies have also revealed that individuals exhibiting more FNE seem like experiencing more intense social anxiety [28], and the higher level of social anxiety tended to transition into SP. Consequently, FNE produced a positive relationship with the prevalence of social phobia among college students [29].

Meanwhile, self-esteem could predict fear of negative evaluation. SE encompasses individuals’ perceptions and judgments regarding their capabilities and values [30]. Self-determination theory [31,32] suggests that SE represents a continuum from true SE to contingent SE. True SE was the more constant personal characteristic that was not reliant on meeting external standards or the validation of others. It is less concerned with or affected by negative evaluations from others. On the other hand, contingent self-esteem depended on meeting imposed or external standards. Individuals with contingent self-esteem focus on seeking and maintaining positive self-definitions, are more concerned about negative evaluations from others and often rely on positive achievements to validate their positive emotions about themselves [33,34]. Related research has identified self-esteem as a crucial predictive element for individuals’ fear of negative evaluation [35]. Therefore, we propose hypothesis 2: college students’ FNE mediates between their SE and SP.

About the moderating effect that perfectionism plays

Perfectionism may have moderated the predictive impact that college students’ FNE had on SP. Perfectionism refers to one’s personality trait characterized by striving for high standards in tasks and tendencies toward self-criticism [36]. This personality trait of perfectionism was closely linked to the psychological well-being of college students [37–39]. Perfectionists are unsatisfied unless they meet their standards, and imperfect outcomes or evaluations not recognized by others could cause excessive stress, leading to various psychological issues such as symptoms of anxiety [40]. Moreover, based on the SADCBM theory, individuals’ FNE not only directly led to SP but also interacted with excessive self-focus, exacerbating SP [2]. Perfectionists often hold excessively high demands for their performance, achievements, and external evaluations, frequently fixating on their flaws or errors and striving relentlessly for perfection [41], indicating excessive self-focus. Therefore, we propose hypothesis 3: perfectionism intensifies the impact that FNE plays on SP. In particular, the predictive power that FNE shows on SP is stronger for college students full of more perfectionism compared to those with less perfectionism.

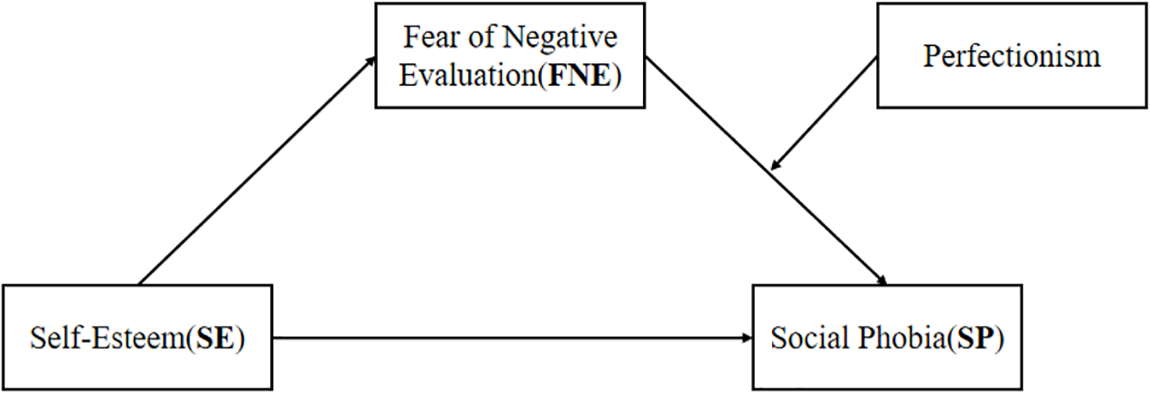

To conclude, although earlier research established a direct connection between social phobia and self-esteem in college students, there has been minimal investigation into the mechanisms that underlie this relationship. Building upon the SADCBM theory, a moderated mediating hypothesis model is constructed based on a review and analysis of existing literature to investigate three main questions: (1) whether SE negatively predicts SP among college students; (2) whether FNE mediates the relationship between college students’ SE and SP; and (3) whether perfectionism moderates this mediating model. These research hypotheses are illustrated in Fig. 1. This model enhances our awareness of some direct relation between college students’ SE and SP, not only elucidating how SE reduces SP but also exploring when this influence may be amplified or attenuated. Thus, it explains the mechanisms behind college students’ SP and provides theoretical support for enhancing SE and reducing SP in this population.

Figure 1: A moderated mediation model.

In this study, a cross-sectional survey was designed not only to explore the relationship between college students’ SE and SP, but also to reveal the mediating effect that FNE plays, and perfectionism’s moderating effect on this relationship. A convenient sampling survey was employed to gather data from 1300 university attendees across four institutions in Shandong Province, China, through a questionnaire distributed in October 2023. To verify the sincerity of the participants in filling out the questionnaire, it included random questions to detect dishonesty, compelling the participants to choose specific responses to weed out untruthful data (for instance, “For this item, please select ‘disagree’”). Following the removal of 80 questionnaires due to non-serious responses, incomplete information, or outlier data, a total of 1020 responses were deemed valid. Among these valid responses, participants’ ages was from 17 to 23 years (Mean = 19.20, SD = 1.03), with 568 female and 452 male students participating.

Rosenberg’s Self-esteem Scale (SES) [42] was adopted in the form of Chinese version, which has the good reliability and validity in measuring self-esteem levels in the Chinese population [43]. There are 10 items in the form of a four-point Likert scale shown as the score from “1 = completely disagree” to “4 = completely agree”, and the average score is calculated after the reverse score of four items. A greater total score stands for college students’ higher level of SE. The confirmatory factor analysis results about this scale were: χ2/df = 13.79, TLI = 0.93, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.11, indicating that the validity of the scale is acceptable, and its Cronbach’s α was up to 0.82.

Fear of negative evaluation scale (FNES)

The study used Leary’s short-form Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale [44] to measure college students’ FNE. The scale was made up of 12 items, among which 8 items were positively stated and 4 items were negatively stated. Studies have shown that since the negative words in the four negative items may confuse the respondents and cause errors [45,27], the use of eight positive items can also achieve effective measurement. Therefore, all items on the scale are positive. The scale utilizes a 5-point scoring way, with “1” indicating “not like me at all” and “5” indicating “completely like me”. Compute the mean score across all items; a higher score indicates the participant’s increased level of apprehension about FNE. The confirmatory factor analysis results about this scale were: χ2/df = 15.57, TLI = 0.96, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.11, indicating that the validity of the scale is acceptable, and its Cronbach’s α was up to 0.96.

The Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale used in this study was developed by Chinese scholars Wang and Dai based on a sample of Chinese college students [46]. The scale comprises two subscales: High Standards of Perfectionism and Adaptive Perfectionism, totaling 29 items scored by a five-point Likert scale with “1 = strong disagreement” to “5 = strong agreement”. The higher scores tend to indicate participants’ stronger intention toward perfectionism. The Adaptive subscale comprises two dimensions: emotional and cognitive-behavioral; higher scores indicate more prominent maladaptive manifestations caused by the pursuit of perfectionism. The higher average scores signify participants’ higher levels of perfectionism. The confirmatory factor analysis results about this scale were: χ2/df = 11.18, TLI = 0.90, CFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.10, indicating that the validity of the scale is acceptable, and its Cronbach’s α was up to 0.92.

Fergus’s brief social phobia scale, revised based on a sample of Chinese university students [47], consists of 6 items in the form of a five-point Likert scale that is denoted as the range from “1 = disagree strongly” to “5 = agree strongly”. The higher average score indicates higher levels of participants’ social phobia. The confirmatory factor analysis results about this scale were: χ2/df = 6.93, TLI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.07, indicating that the scale has good validity, and its Cronbach’s α was up to 0.95.

IBM SPSS 26.0 was utilized in the description, reliability, correlation, and regression analysis. A regression-based path approach was employed, utilizing the PROCESS macro to examine conditional indirect relationships [48]. In this study, we employed models 4 and 14 from the PROCESS macro. A moderated mediation model was tested using a conditional process model with bootstrap procedure techniques. In all effect analyses, we computed the 95% confidence intervals by using five thousand bootstrap resamples. p values at least less than 0.05 are regarded as the basic standard of being statistically significant.

In this research involving human participants, adherence to the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments was ensured. This study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of Qingdao Harbor Vocational and Technical College, Qingdao, China (IRB number: 20230323). Prior to data gathering, all participants signed the informed consent in this study. They were informed of their choice and decision to discontinue participation at any point, and the privacy of their responses was guaranteed. After each participant completed the questionnaire, we provided a small token of appreciation as a thank-you for their efforts.

Description and correlation analysis

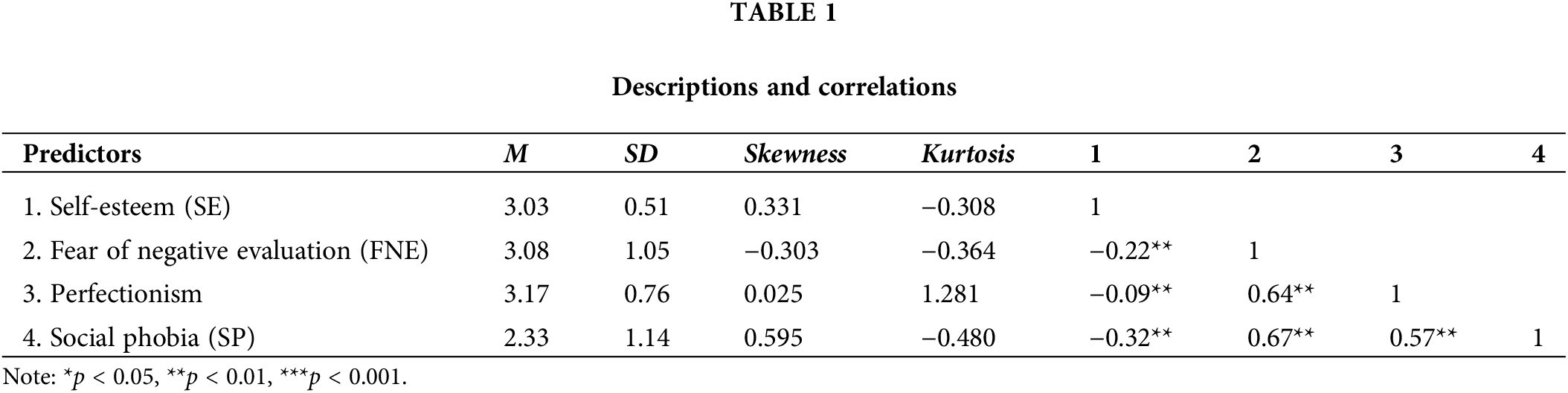

In terms of statistics shown in Table 1, correlation analyses have shown SE was negatively related with FNE (r = −0.22, p < 0.01), perfectionism (r = −0.09, p < 0.01) and SP (r = −0.32, p < 0.01). FNE was positively related with perfectionism (r = 0.64, p < 0.01) and SP (r = 0.67, p < 0.01). In addition, perfectionism was positively related with SP (r = 0.57, p < 0.01). Additionally, the skewness and kurtosis values for each variable suggest adherence to a normal distribution in the data.

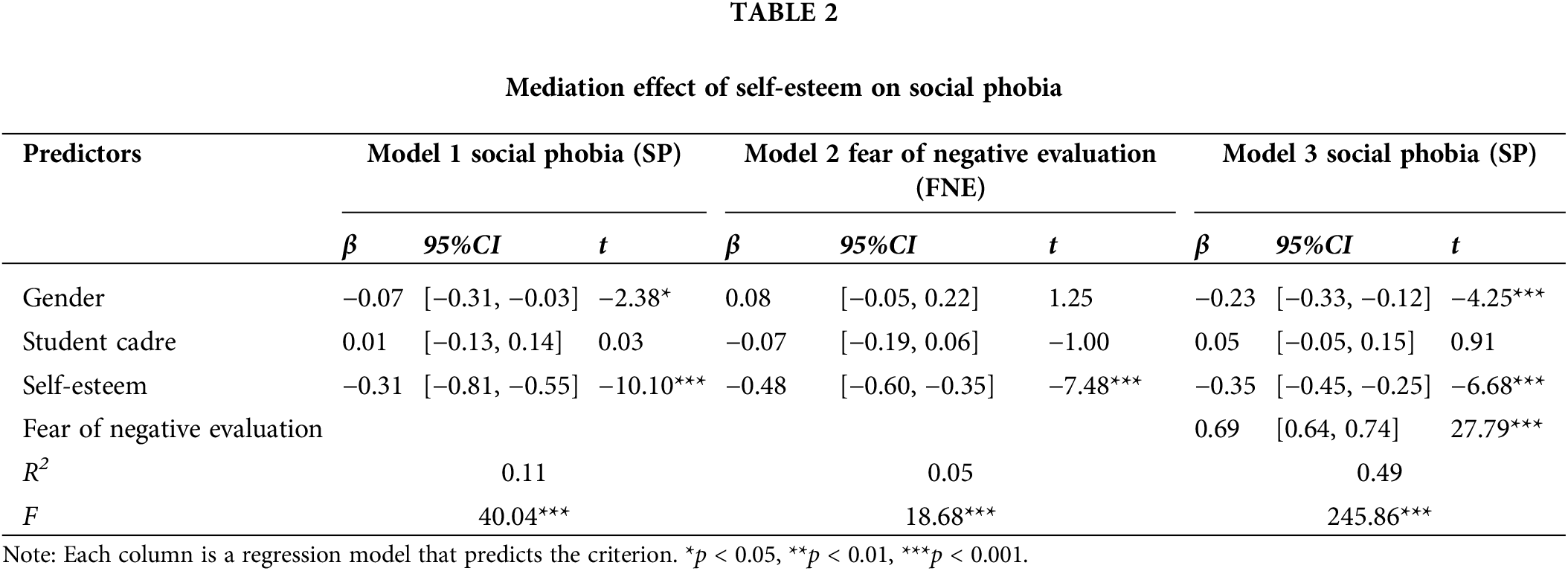

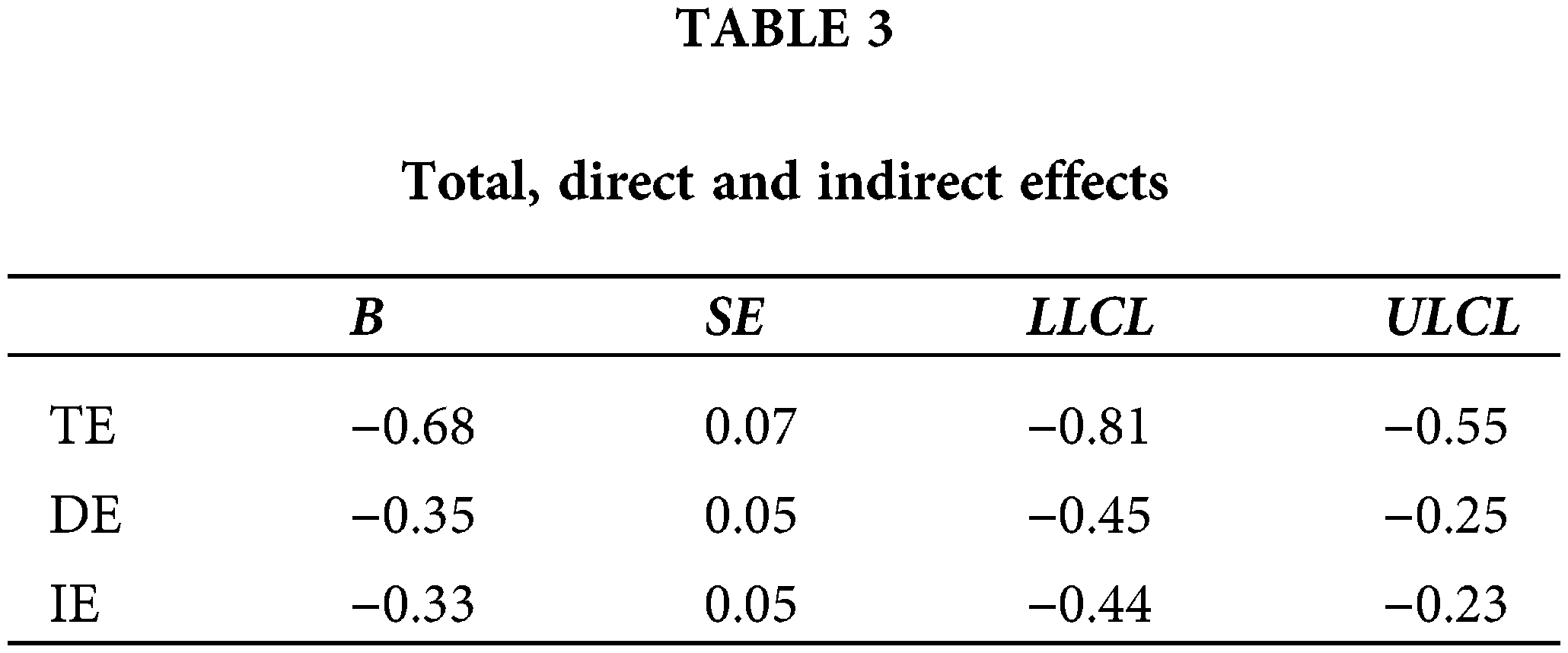

Initially, on the basis of controlling for variables such as gender and student cadre experience, a regression analysis by using SPSS software was to explore the direct effect (DE) of college students’ self-esteem on social phobia. Subsequently, Model 4 (a mediation model) from the SPSS macro process developed by Hayes [48] was established to probe the mediation role that FNE played in the relationship between SE and SP.

Table 2 showed that SE posed a significantly and negatively predictive power on SP (β = −0.31, t = −10.10, p < 0.001). While FNE, as the mediating variable, was introduced, the negatively predictive power of SE on SP was still significant (β = −0.35, t = −6.68, p < 0.001), while the negatively predictive power of SE on FNE was significant (β = −0.48, t = −7.48, p < 0.001). FNE significantly and positively predicted SP (β = 0.69, t = 27.79, p < 0.001). There is the absence of zeros in 95% confidence interval between the upper limit and the lower limit, as outlined in Table 3, regarding the direct effect of SE on SP and the indirect effect (IE) of FNE, which signifies that self-esteem not only has a direct predictive power over SP but also significantly forecasts SP by means of the mediation impact of FNE. This result also verified the existence of mediation effect of FNE, which accounted for 48.97% of the total effect (TE).

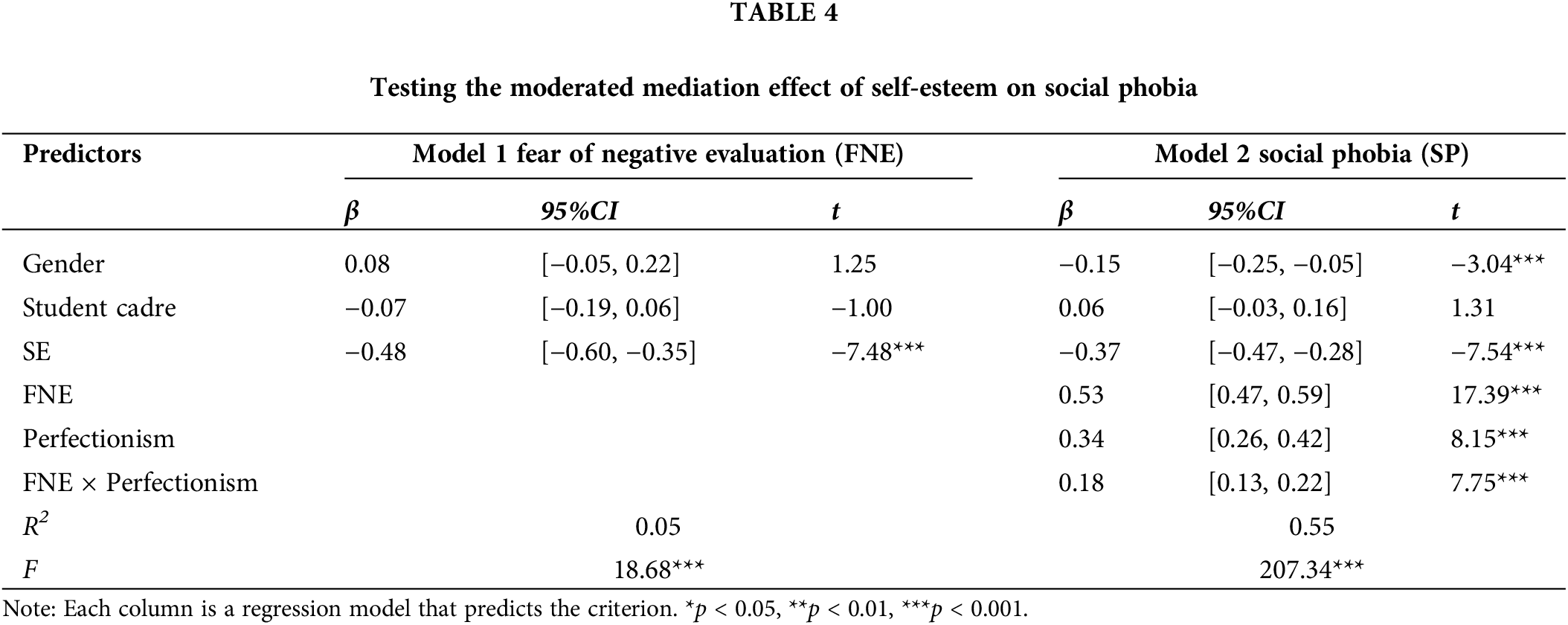

For checking the moderating role of perfectionism, Model 14 from the SPSS macro process was utilized, focusing on the moderation of the latter part of the mediation model in this research. The findings are presented in Table 4. After the control of gender and experience as student cadre variables, perfectionism was put into the mediating model. The interaction between perfectionism and FNE was significantly predictive of social phobia (β = 0.18, t = 7.75, p < 0.001), revealing that perfectionism moderates the predictive effect of self-esteem on social phobia.

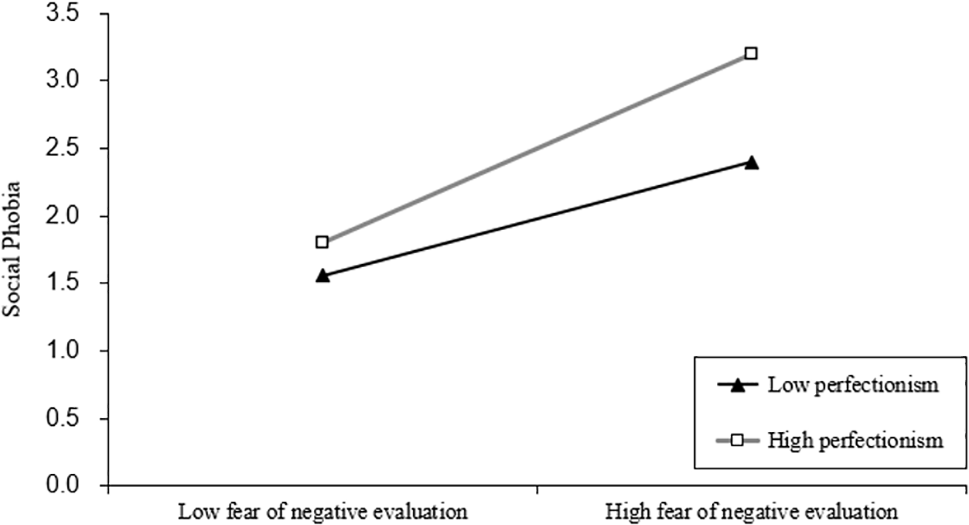

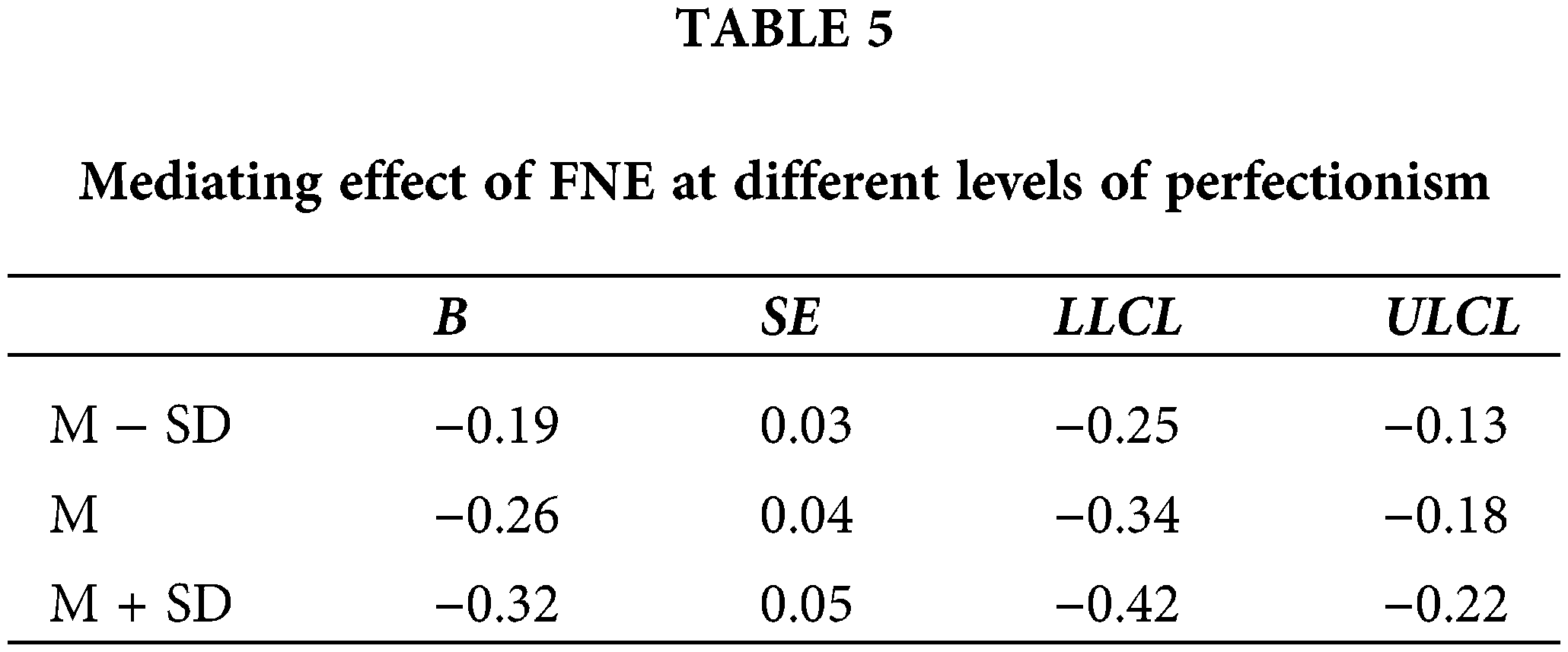

We carried out simple slope analyses to illustrate whether there are the significantly interactive effects of college students’ perfectionism. In Fig. 2, FNE positively predicted SP (β = 0.40, t = 11.55, p < 0.001) for participants with low perfectionism (M − SD), while for participants with high perfectionism (M + SD), FNE strongly and positively predicted SP (β = 0.67, t = 18.62, p < 0.001), indicating that FNE has somewhat stronger effect on SP with the increasing level of individuals’ perfectionism. Further analysis of the moderating effect of perfectionism on the mediating role of FNE revealed that for high-perfectionism participants (M + SD), the mediation effect of FNE was at the higher level (Table 5).

Figure 2: Moderating effect of perfectionism on the relationship between self-esteem (SE) and social phobia (SP).

For the sake of college students’ good personal relationships and mental health development, this study explored the mediating role of college students’ fear of negative evaluation between self-esteem and social phobia, as well as the moderating effect of perfectionism within this relationship. Building upon prior important findings, this research gives a more outlook of the internal mechanisms by means of which self-esteem influences social phobia in college students. The findings offer theoretical support for specific intervention measures aimed at reducing social phobia among college students.

The research findings indicate that college students’ SE makes a direct negative predictive effect on their social phobia, with the DE accounting for 48.97% of the TE, confirming hypothesis 1. This outcome aligns with existing research on the relationship between SE and SP [15–18], suggesting that college students with lower SE are more likely to suffer from SP. The Fear Management Theory can explain this result [49]. According to the Anxiety-buffer Hypothesis of Fear Management Theory, SE acts as an “anxiety buffer,” with stronger SE resulting in reduced susceptibility to anxiety and less likelihood of behavior associated with anxiety. Conversely, weakened SE leads to increased susceptibility to anxiety, prompting individuals to worry about revealing inner fears, thereby triggering various defense mechanisms and compensatory behaviors to enhance self-worth [50]. SP represents higher levels of social apprehension and is influenced by lower SE. Therefore, college students’ SE exerts the direct negative predictive effect on their SP.

It is discovered that college students’ FNE partially mediates the relation between their SE and SP. In other words, the effect of SE on SP operates through two pathways: one directly predicting SP and the other through the mediating role of FNE. Several explanations might underlie this finding. According to the sociometer theory of SE, SE serves like a subjective measuring instrument of an individual’s relationships with society and significant others, reflecting the status of their interpersonal relationships. It functions as a gauge of interpersonal relations, prompting individuals to maintain a certain level of acceptance by others. In preserving SE, individuals adopt strategies to maintain positive self-evaluations, such as avoiding situations that might lead to negative evaluations to prevent damage to their SE. Individuals with low SE might hold negative self-appraisals, feeling inferior to others, which might lead to concerns about rejection or disapproval in social situations [51], thus generating FNE. Individuals experiencing FNE tend to exhibit SP during interactions, evaluating potential threats in social environments and avoiding these perceived threats [25], resulting in SP. In essence, individuals with low SE tend to make negative self-assessments in social evaluation situations and FNE from others. This cognitive style is considered a core factor triggering SP [52,53]. Therefore, college student’ FNE functions as a mediator in the connection between their SE and SP.

The moderating effect of perfectionism

This finding was that the prediction effect of college students’ FNE on SP is moderated by perfectionism. As for college students with perfectionism at the higher level, their FNE shows a stronger impact on SP and a more mediating role. For one thing, this aligns with the above-mentioned SADCBM theory, suggesting that FNE not only can directly cause SP but also interacts with the excessive self-focus of perfectionism, exacerbating SP [2]. Perfectionists tend to set higher standards for themselves [36]. In social settings, if a perfectionist worries about falling short of their expectations or fear negative evaluations from others, this fear might lead to avoidance of social situations or manifest as increased anxiety and fear. They become more concerned about others’ perceptions, and more sensitive to negative evaluations, potentially intensifying their concerns about social relationships and consequently triggering SP. For another thing, college students’ personality traits about perfectionism may be related to this finding. The pursuit of superiority or perfection is an innate internal drive-in people, reflecting the inherent need to overcome shortcomings [54]. However, high levels of perfectionism inherently contain certain negative aspects [55]. As people aim for elevated standards, the risk of failing rises, providing more instances of receiving negative feedback, which in turn cultivates a fearful sense of being negatively evaluated. This effectively strengthens the effect of college students’ FNE and intensifies its effect on SP. Therefore, perfectionism might exacerbate the effect that college students’ FNE plays on social phobia, increasing their preoccupation with potential negative evaluations in social situations and subsequently intensifying the severity of SP.

Research Limitations and Implications

Actually, some shortages exist in this study. First, initially, scholars believed that perfectionism was a single-dimensional construct [56]. However, as research progressed, scholars proposed both two-dimensional and multi-dimensional views of perfectionism [57,58]. Presently, this study only utilized a two-dimensional scale of perfectionism, examining its moderating effect from a single-dimensional perspective, resulting in incomplete findings. In the future, we should make a relatively comprehensive analysis about multidimensional perspectives of perfectionism in the formation mechanism of SP among college students. Second, the cross-sectional approach used does not confirm causality among SE, FNE, perfectionism, and SP. In the future survey, longitudinal methods are supposed to clarify the pathways in our theoretical framework. Third, this study’s reliance on self-reported data may compromise its validity. To address this, subsequent research should include data from a variety of evaluators, thereby diminishing the impact of subjective biases.

Self-esteem not only directly influences social phobia in college students but also affects it by way of the mediating role of FNE. The impact of college students’ FNE on SP is moderated by perfectionism, meaning that its effect is more pronounced among groups of students with higher levels of perfectionism. Simultaneously, perfectionism moderates the mediating role of FNE in SE and SP, indicating that the higher level of perfectionism, the stronger the mediating role of FNE.

Acknowledgement: We feel so grateful to those who actively helped and cooperated with the researchers to collect data.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Key Special Project of the Shandong Provincial Federation of Social Sciences on Humanities and Social Sciences “Risk Assessment and Prevention Mechanisms of ‘Social Phobias’ Phenomenon among College Students from the Perspective of Healthy China” (No. 2023-zkzd-030), and Special Task Project of Humanities and Social Science Research of the Ministry of Education in 2023 (Research on University Counselors) (No. 23JDSZ3080).

Author Contributions: Lv Shuai: Methodology, writing-original draft preparation, editing & data collecting and analysis; Zhaojun Chen: writing-review and editing; Wang Hui: Conceptualization & writing-review; Mao Jian: Data collecting; Hai Yujuan: editing; Wu Peibo: Data analysis. All authors agreed on the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data sets utilized or analyzed in this study can be obtained from the first author upon a reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of Qingdao Harbor Vocational and Technical College, Qingdao, China (IRB number: 20230323). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Association Psychological Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: Association Psychological Association; 1994. p. 980. [Google Scholar]

2. Emmelkamp PM, Meyerbröker K. Personality disorders. London: Psychology Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

3. Jefferies P, Ungar M. Social anxiety in young people: a prevalence study in seven countries. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239133. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Salehi E, Mehrabi M, Fatehi F, Salehi A. Virtual reality therapy for social phobia: a scoping review. In: Medical Informatics in Europe Conference (MIE); 2020; Amsterdam, Netherlands, IOS Press. p. 713–7. [Google Scholar]

5. Penninx BW, Eikelenboom M, Giltay EJ, van Hemert AM, Beekman AT. Cohort profile of the longitudinal Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) on etiology, course and consequences of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 2021;287:69–77. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Nawi AM, Ismail R, Ibrahim F, Hassan MR, Shafurdin NS. Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11906-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Goodman FR, Rum R, Silva G, Kashdan TB. Are people with social anxiety disorder happier alone? J Anxiety Disord. 2021;84:102474. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chagas MHN, Nardi AE, Manfro GG, Hetem LAB, Crippa JAS. Guidelines of the Brazilian medical association for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of social phobia disorder. Braz J Psychiat. 2010;32:444–52. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462010005000029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. McEnery C, Lim MH, Tremain H, Knowles A, Alvarez-Jimenez M. Prevalence rate of social anxiety disorder in individuals with a psychotic disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:25–33. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Pontillo M, Tata MC, Averna R, Demaria F, Gargiullo P, Guerrera S, et al. Peer victimization and onset of social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. Brain Sci. 2019;9(6):132. doi:10.3390/brainsci9060132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Rapee RM, Oar EL, Johnco CJ, Forbes MK, Fardouly J, Magson NR, et al. Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: a review and conceptual model. Behav Res Ther. 2019;123:103501. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2019.103501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Danneel S, Nelemans S, Spithoven A, Bastin M, Bijttebier P, Colpin H, et al. Internalizing problems in adolescence: linking loneliness, social anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms over time. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47:1691–705. doi:10.1007/s10802-019-00539-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Pera A. The psychology of addictive smartphone behavior in young adults: problematic use, social anxiety, and depressive stress. Front Psychiat. 2020;11:573473. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.573473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kim SS, Liu M, Qiao A, Miller LC. “I Want to Be Alone, but I Don’t Want to Be Lonely”: uncertainty management regarding social situations among college students with social phobia disorder. Health Commun. 2022;37(13):1650–60. doi:10.1080/10410236.2021.1912890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang Y, Li S, Yu G. The relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety: a meta-analysis with Chinese students. Adv Psychol Sci. 2019;27(6):1005. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2019.01005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gurung UN, Sampath H, Soohinda G, Dutta S. Self-esteem as a protective factor against adolescent psychopathology in the face of stressful life events. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2019;15(2):34–54. doi:10.1177/0973134220190203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lin Y, Fan Z. The relationship between rejection sensitivity and social anxiety among Chinese college students: the mediating roles of loneliness and self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(15):12439–48. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-02443-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pietrabissa G, Gullo S, Aimé A, Mellor D, McCabe M, Alcaraz-Ibánez M, et al. Measuring perfectionism, impulsivity, self-esteem and social anxiety: cross-national study in emerging adults from eight countries. Body Image. 2020;35:265–78. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.09.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

20. Beck AT, Emery G. Anxiety disorders and phobias: acognitive perspective. J Pers Assess. 1985;67:588–97. [Google Scholar]

21. Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press; 1995. p. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

22. Barbeau K, Guertin C, Boileau K, Pelletier L. The effects of self-compassion and self-esteem writing interventions on women’s valuation of weight management goals, body appreciation, and eating behaviors. Psychol Women Q. 2022;46(1):82–98. doi:10.1177/03616843211013465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Emmanuel A, Oyedele EA, Gimba SM, Gaji LD, Terdi KD. Does self-esteem influence social phobia among undergraduate nursing students in Nigeria? Int J Med Health Res. 2015;2(1):28–33. [Google Scholar]

24. Hoyer J, Wiltink J, Hiller W, Miller R, Leibing E. Baseline patient characteristics predicting outcome and attrition in cognitive therapy for social phobia: results from a large multicentre trial. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2016;23(1):35–46. doi:10.1002/cpp.1936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Heimberg RG, Brozovich FA, Rapee RM. A cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety disorder: update and extension. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, editors. Social anxiety: Clinical, developmental, and social perspectives. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Academic Press; 2010. p. 395–422. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-375096-9.00015-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Leary MR, Kowalski RM, Campbell CD. Self-presentational concerns and social phobia: the role of generalized impression expectancies. J Res Pers. 1988;22(3):308–21. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(88)90032-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Weeks JW, Heimberg RG, Fresco DM, Hart TA, Liebowitz MR. Empirical validation and psychometric evaluation of the brief fear of negative evaluation scale in patients with social phobia disorder. Psychol Assess. 2005;17(2):179. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.17.2.179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Villarosa-Hurlocker MC, Whitley RB, Capron DW, Madson MB. Thinking while drinking: fear of negative evaluation predicts drinking behaviors of students with social anxiety. Addict Behav. 2018;78:160–5. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Iqbal A, Ajmal A. Fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety in young adults. Peshawar J Psychol Behav Sci (PJPBS). 2018;4(1):45–53. doi:10.32879/picp.2018.4.1.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

31. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Human autonomy. In: Kernis MH, editor. Efficacy, Agency, and Self-Esteem. New York: Springer US; 1995. p. 31–49. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1280-0_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11(4):227–68. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Blom V. Contingent self-esteem, stressors and burnout in working women and men. Work. 2012;43(2):123–31. doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-1366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Marčič R, Grum DK. Gender differences in self-concept and self-esteem components. Stud Psychol. 2011;53(4):373–84. [Google Scholar]

35. Khanam SJ, Moghal F. Self esteem as a predictor of fear of negative evaluation and social phobia. Pak J Psychol. 2012;43(1):101–10. [Google Scholar]

36. Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognit Ther Res. 1990;14:449–68. doi:10.1007/BF01172967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Fernández-García O, Gil-Llario MD, Castro-Calvo J, Morell-Mengual V, Ballester-Arnal R, Estruch-García V. Academic perfectionism, psychological well-being, and suicidal ideation in college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20(1):85. doi:10.3390/ijerph20010085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kamushadze T, Martskvishvili K, Mestvirishvili M, Odilavadze M. Does perfectionism lead to well-being? The role of flow and personality traits. Europe’s J Psychol. 2021;17(2):43–57. doi:10.5964/ejop.1987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Geranmayepour S, Besharat MA. Perfectionism and mental health. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:643–7. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Diedrich A, Voderholzer U. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: a current review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:1–10. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0547-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(3):456–470. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang X, Wang X, Ma H. Manual of mental health rating scale. Beijing, China: China Mental Health Journal; 1999. [Google Scholar]

43. Lo MT, Chen SK, O’Connell AA. Psychometric properties and convergent validity of the chinese version of the rosenberg self-esteem scale. J Appl Meas. 2018;19(4):413–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

44. Leary MR. A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1983;9(3):371–6. doi:10.1177/0146167283093007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Rodebaugh TL, Woods CM, Thissen DM, Heimberg RG, Rapee RM. More information from fewer questions: the factor structure and item properties of the original and brief fear of negative evaluation scale. Psychol Assess. 2004;16(2):169. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Dai X, Zhang J, Cheng Z, Wang M. Manual of common psychological assessment scales. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2015. [Google Scholar]

47. Sun H, Yang X, Hu Y, Ren L, Zhou Y, Liu J. Preliminary examination of the reliability and validity of the brief fergus social phobia and social phobia scale. Chinese J Clin Psychol. 2021;3:534–8. [Google Scholar]

48. Hayes AF. Methodology in the Social Sciences. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

49. Leary MR, Tangney JP. Handbook of self and identity. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

50. Pyszczynski T, Greenberg J, Solomon S, Arndt J, Schimel J. Why do people need self-esteem? A theoretical and empirical review. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):435. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Kocovski NL, Endler NS. Social anxiety, self-regulation, and fear of negative evaluation. Eur J Pers. 2000;14(4):347–58. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0984(200007/08)14:4<347::AID-PER381>3.0.CO;2-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Bautista CL, Hope DA. Fear of negative evaluation, social phobia and response to positive and negative online social cues. Cognit Ther Res. 2015;39:658–68. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.05.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Weeks JW, Heimberg RG, Rodebaugh TL. The fear of positive evaluation scale: assessing a proposed cognitive component of social anxiety. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(1):44–55. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.08.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Adler F. The value concept in sociology. Am J Sociol. 1956;62(3):272–9. [Google Scholar]

55. Bergman AJ, Nyland JE, Burns LR. Correlates with perfectionism and the utility of a dual process model. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43(2):389–99. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Burns DD. The perfectionist’s script for self-defeat. Psychol Today. 1980;14(6):34–52. [Google Scholar]

57. Baker D. Developing a theory of psychopathological perfectionism within a cognitive behavioural framework. Derby: University of Derby; 2021. [Google Scholar]

58. Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Dimensions of perfectionism in unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(1):98. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.1.98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools