Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Association between Meeting 24-Hour Movement Guidelines and Psychological Features of Chinese Emerging Adults

1 Physical Education Unit, School of Humanities and Social Science, Chinese University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen, Shenzhen, 518172, China

2 Physical Activity and Health Promotion Laboratory, Chinese University of Hong Kong–Shenzhen, Shenzhen, 518172, China

3 Body-Brain-Mind Laboratory, School of Psychology, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, 518060, China

4 School of Physical Education, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, 518060, China

5 Chinese Traditional Regimen Exercise Intervention Research Center, Beijing Sport University, Beijing, 100084, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaolei Liu. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(5), 399-406. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.048925

Received 21 December 2023; Accepted 04 March 2024; Issue published 30 May 2024

Abstract

Background: Emerging adulthood is a pivotal life stage, presenting significant psychological and social changes, such as decreased sociability, depression, and other mental health problems. Previous studies have associated these changes with an unhealthy lifestyle. The 24-h movement guidelines for healthy lifestyles have been developed to promote appropriate health behaviors and improve individual wellness. However, the relationship between adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and different characteristics of Chinese emerging adults is yet to be explored. This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the association between adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and four characteristics (self-exploration, instability, possibilities, and responsibility) of Chinese emerging adults. Methods: Overall, 1,510 Chinese emerging adults aged 18–29 years were included in this study. Each participant completed a self-administered questionnaire that included questions on adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines (physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep) and the inventory of dimensions of emerging adulthood. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was employed to investigate the associations between adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and each of the four characteristics. Results: The proportion of participants who adhered to the 24-h movement guidelines was 31.72%. Multiple regression analysis revealed a significantly negative relationship between adhering to more guidelines and instability (β = −0.51, p < 0.001). A statistically significant association was observed between instability and meeting only sedentary behavior (β = −1.27, 95% confidence interval [CI]: [−2.32, −0.24], p = 0.02), sedentary behavior + sleep (β = −1.30, 95% CI: [−2.24, −0.35], p < 0.01), and physical activity + sedentary behavior (β = −1.08, 95% CI: [1.94, −0.21], p = 0.02) guidelines. Further, positive and significant associations were observed between possibilities and meeting the guidelines for only physical activity (β = 0.70, 95% CI: [0.14, 1.27), p = 0.01), only sleep (β = 0.61, 95% CI: [0.01, 1.21], p = 0.04), physical activity + sedentary behavior (β = 0.56, 95% CI: [0.04, 1.07), p = 0.01), and physical activity + sleep (β = 0.76, 95% CI: [0.23, 1.27], p = 0.01). Conclusions: These findings suggest that adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines was associated with instability in Chinese emerging adults. Future studies are warranted to verify our findings to highlight the importance of maintaining a heath lifestyle to promote health in emerging adulthood.Keywords

Emerging adulthood is a special, multifaceted, and dynamic period of development that spans from late adolescence to the initial stages of adulthood [1,2]. Emerging adults navigate a landscape characterized by heightened autonomy, an array of diverse opportunities, and a simultaneous grappling with uncertainties and responsibilities [3]. During the developmental process of emerging adulthood, individuals experience diverse changes in the physical, psychological, behavioral, employment, and romantic relationship domains [4,5]. This new life period often presents challenges, such as decreased sociability, psychological distress, and anxiety disorders, that can detrimentally affect mental health [6]. An epidemiological review found that more than 40% of individuals aged 18–29 years experienced at least one psychiatric disorder in a 12-month period. This prevalence, especially for mood and anxiety disorders, is significantly higher than that in other age groups [7]. Similarly, another study reported that approximately 30% of emerging adults had depressive symptoms, of which 13.2% had major depressive episodes [8]. Such psychopathological issues during emerging adulthood hinder adaptation and a successful transition to adulthood.

A previous study suggested that the elevated prevalence of mental problems implies a correlation between the features of emerging adulthood and an increased susceptibility to mental disorders [9]. Based on the American cultural context, Arnett et al. [6] proposed five distinct characteristics of emerging adulthood including identity explorations, instability, self-focus, feeling in-between, and optimism/possibilities. However, cultural nuances have led to the development of different dimensions. The inventory of dimensions of emerging adulthood-Chinese version (IDEA-C) was developed previously and consists of four features including self-exploration, instability, possibilities, and responsibility [2]. Self-exploration is an important aspect of emerging adulthood, as individuals seek to understand themselves and their place in the world. With explorations and experience of internal struggles to establish their identity, emerging adults may exhibit significant challenges that influence their psychophysiological well-being [10]. For example, in coping with identity exploration, emerging adults often report increased tendencies toward ruminative exploration and depressive symptoms [11], alongside decreased experiences of fun, satisfaction, and excitement [12]. Instability refers to the uncertainty and changes that occur during this period, such as changes in relationships, education, and employment. All these uncertain life circumstances may create challenges and instability, subsequently leading to the development of several unstable mental problems (e.g., depression and stress) [10]. Possibilities refer to the opportunities and potential, such as exploring new interests and experiences, that arise during emerging adulthood. Despite facing difficulties, challenges, and contradictions, the majority of emerging adults maintain an unwavering belief in the promising prospects of their future [13], leading to increased self-esteem and decreased levels of social anxiety levels [14]. Responsibility refers to the development of personal and social responsibilities, such as self-care and social contribution [2,6]. Accepting responsibility is associated with perceived emotional well-being and life satisfaction in emerging adults [15]. Therefore, positively improving the characteristics of these adults is very important to promote their physical and mental health.

Early adulthood serves as a crucial transition, significantly influencing the establishment and adoption of health-promoting behaviors and features of emerging adulthood that persist throughout an individual’s life [16]. Previous studies have highlighted independent associations between regular physical activity (PA), sedentary behavior, sleep patterns, and psychological health [17–21]. For example, a prospective study on emerging adults shows that engaging in daily PA can significantly improve an individual’s satisfaction with life [22] and reduce depressive symptoms [23]. Reduced sedentary time or sufficient sleep in emerging adults has been linked to decreased anxiety and depression levels [24,25]. To encourage healthy lifestyles in the whole population, the Chinese government developed the 24-h movement guidelines that advocate for daily PA, balanced sedentary behavior, and adequate sleep [26]. Although several studies have investigated how adherence to these guidelines impacts physical and psychological health outcomes in children and adolescents [27–30], a knowledge gap regarding these associations among emerging adults in China still exists. Therefore, the present study aimed to understand the relationship between adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and four distinct psychological features—self-exploration, instability, possibilities, and responsibility—among Chinese emerging adults.

This study employed a cross-sectional online design. The participants were conveniently sampled and recruited through advertisements and social media. The voluntarily completed an internet-based survey on the Questionnaire Star Platform from August to September 2022. Each participant’s IP address could only be used once to fill out the questionnaire. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age between 18 and 29 years; (2) absence of major physical or psychological illnesses; and (3) completion of a self-administered questionnaire that included questions on adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines (PA, sedentary behavior, and sleep) and the IDEA-C. The exclusion criteria were: age under 18 years or over 29 years; individuals with a history of drug addiction; incomplete data. A total of 1510 Chinese emerging adults aged 18–29 years provided complete responses. All participants signed a written informed consent form before enrollment in the study. Ethics approval was obtained from the Shenzhen Univesity Human Research Ethics Board (No. PN-2021-048). All participants provided written informed consent.

The Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form was utilized to evaluate self-reported PA levels and sedentary behavior during the past 7 days [31]. Metabolic equivalents (METs) were used to classify the PA level. The METs for each PA level were consistent with previous studies, such as light PA (walking) = 3.3 METs, moderate PA = 4.0 METs, and vigorous PA = 8.0 METs. The total PA amount for each participant was calculated by summing up: walking minutes × walking days × 3.3 METs + moderate PA minutes × moderate PA days × 4.0 METs + vigorous PA minutes × vigorous PA days × 8.0 METs per week. The time spent engaging in moderate and vigorous PA was employed to calculate the moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) level. Sedentary behavior was measured using the question: “In the past 7 days, how much time did you spend sitting on a week day?” Responses to sitting for less than 8 h a day indicated that the adults adhered to the sedentary behavior guideline. Sleep duration was measured using the following single question from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: “In the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you have at night?” Responses ranging from 7 to 9 h/day indicated compliance with the sleep duration guideline.

The degree of identification with emerging adulthood features was assessed using the IDEA-C [2]. The IDEA-C has been shown to be effective in measuring the psychological characteristics of Chinese emerging adults. Compared with the original version of the IDEA developed by Reifman et al., which comprised 20 items with five features. The items in IDEA-C are narrowed down to four features (self-exploration, instability, possibilities, and responsibility). The responses to the IDEA-C items were designed on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 4 = “totally agree”. Higher scores in each subscale indicated greater agreement with the feature.

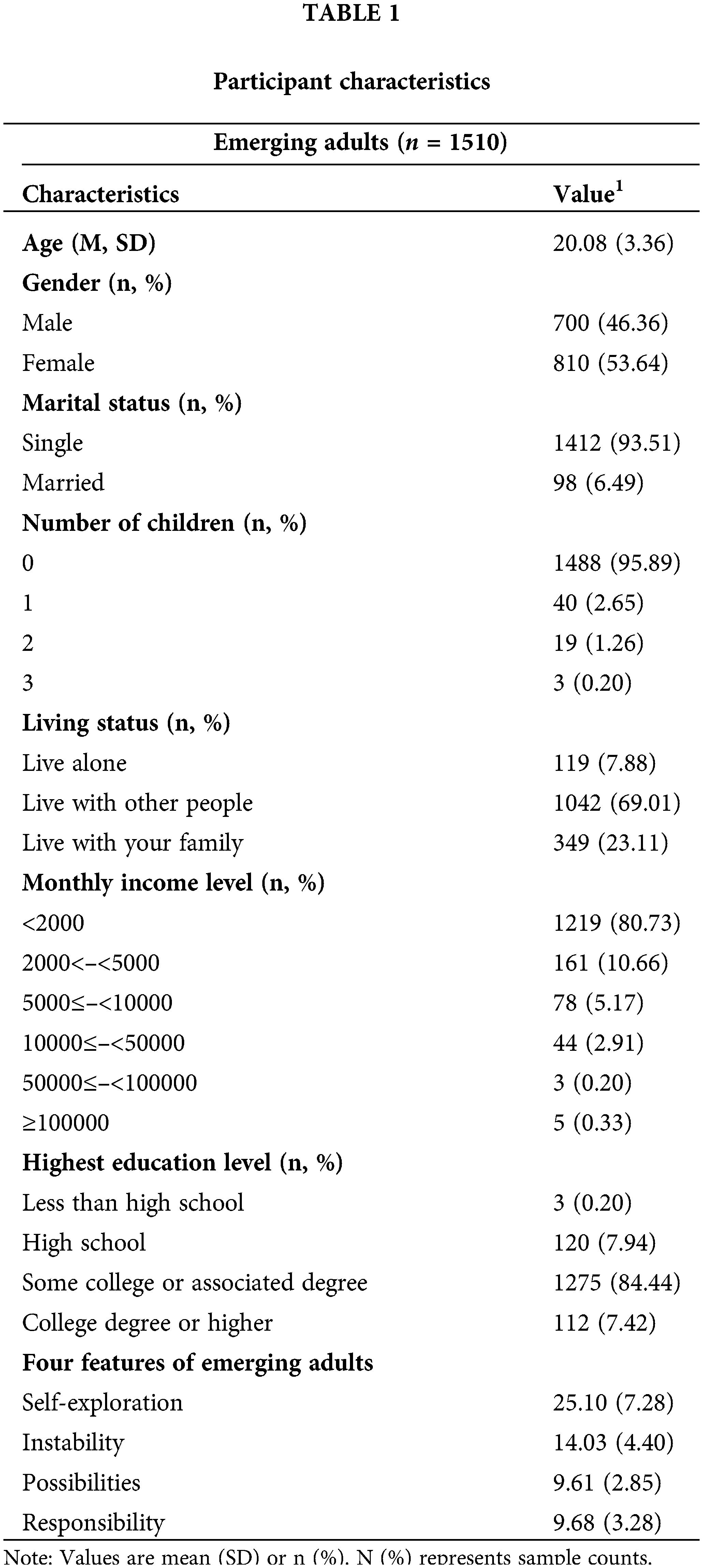

Participants’ demographics encompassing age, gender (men and women), ethnicity (Han and minorities), education level (no schooling, primary school, second school, high school, undergraduate/college, and postgraduate or higher), living situation (living alone, living with classmates, sharing a house with others, living with parents or partner, etc.), and body mass index (BMI). Detailed demographic data is shown in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all the variables. Continuous variables are described using means and standard deviations, and categorical variables are described using unweighted sample counts and percentages. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to estimate odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in the association between adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and the four features (self-exploration, instability, possibilities, and responsibility). Separate analyses were performed for all three components of the 24-h movement guidelines and specific combinations (PA, sleep, sedentary behavior, sedentary behavior + sleep, sedentary behavior + PA, sleep + PA, and PA + sedentary behavior + sleep) as independent variables in the models. Socio-demographic data (age, gender, marital status, number of children, living, income level, and highest education level of emerging adults) were included as potential confounders. Data analysis was conducted using Stata 15.0, and the statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Data on 1,510 Chinese emerging adults aged 18–29 years were included in this study. The mean age of the participants was 20.08 ± 3.36 years, and the majority were single (93.51%). Approximately 96% reported having no children. Of the participants, 69.01% lived with others, 23.11% lived with their family and 7.88% lived alone. The majority (80.73%) reported an income of less than ¥2000, while only a small proportion earned ¥2000–¥5000 (10.66%). Only a negligible percentage of emerging adults (0.20%) responded that they had not completed high school (see Table 1).

Adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines

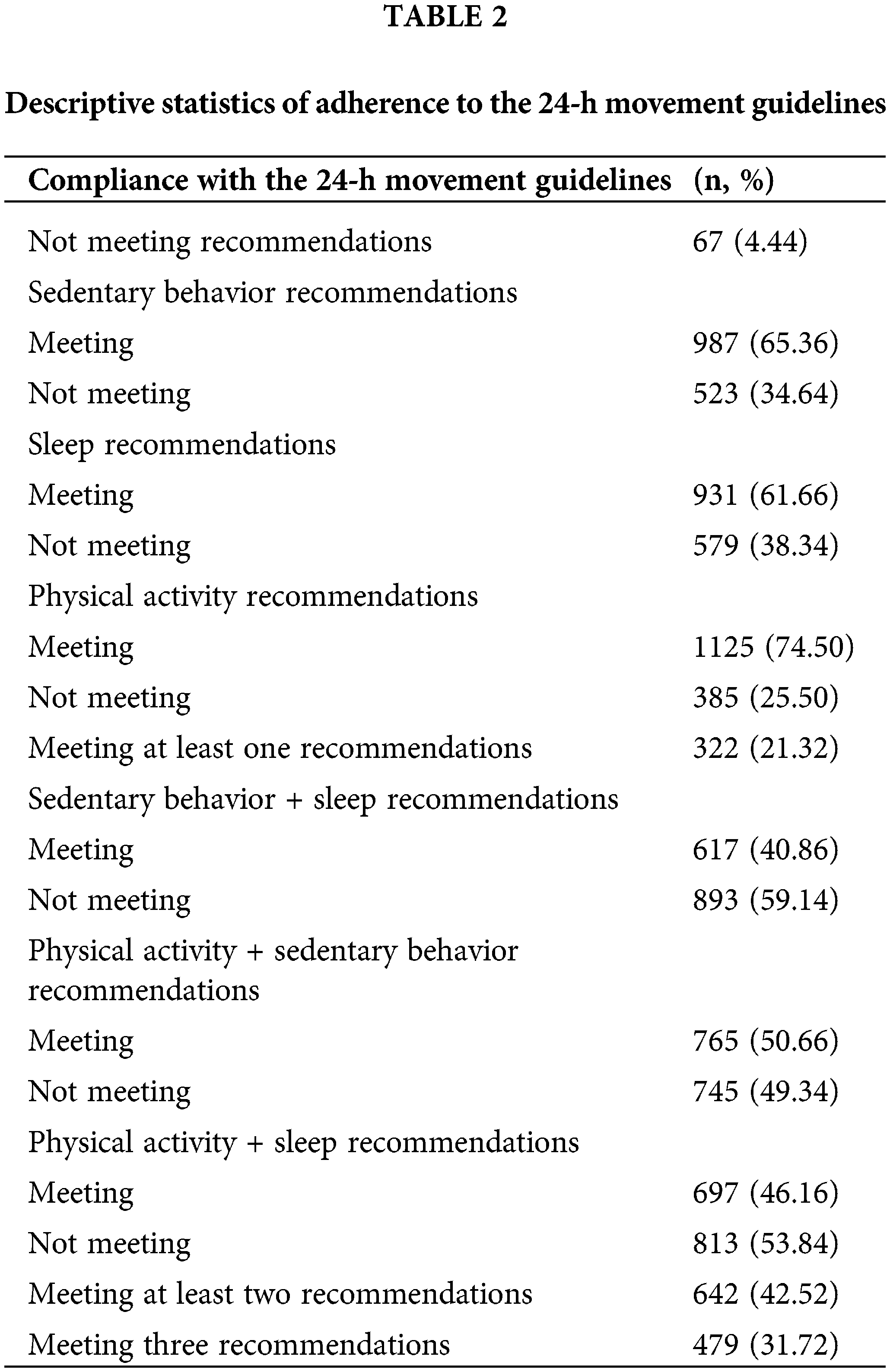

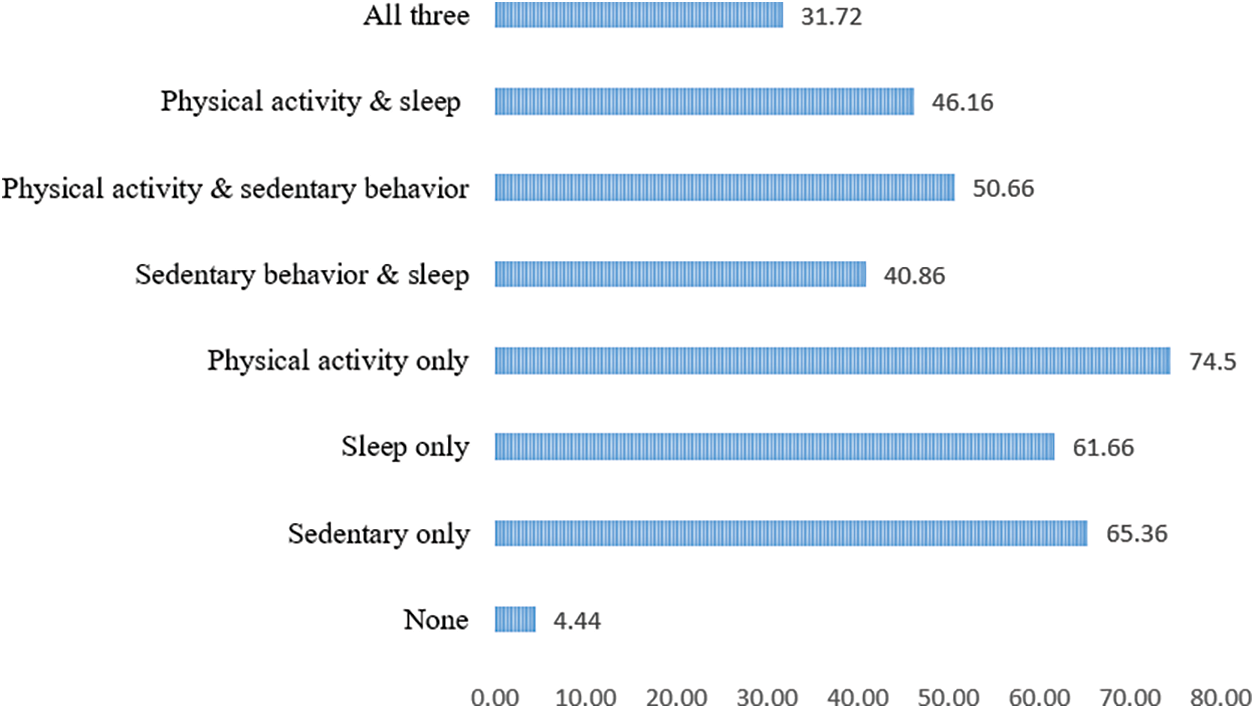

Table 2 and Fig. 1 present the estimated percentages of adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines among Chinese emerging adults. In total, 65.36% (n = 987) of the participants met the sedentary behavior recommendation, 61.66% (n = 931) met the sleep duration recommendation, and 74.50% (n = 1,125) met the PA recommendation. A third of the participants (n = 479, 31.72%) adhered to all three guidelines, while a small proportion (n = 67, 4.44%) did not adhere to any of the guidelines. Among those who followed two of the three recommendations (n = 642, 42.52%), most complied with the sedentary behavior and PA recommendations.

Figure 1: Proportion of emerging adults meeting different combinations of movement behavior recommendations. Data are presented as percentages. N = 1510.

Associations between meeting the 24-h movement guidelines and the four features

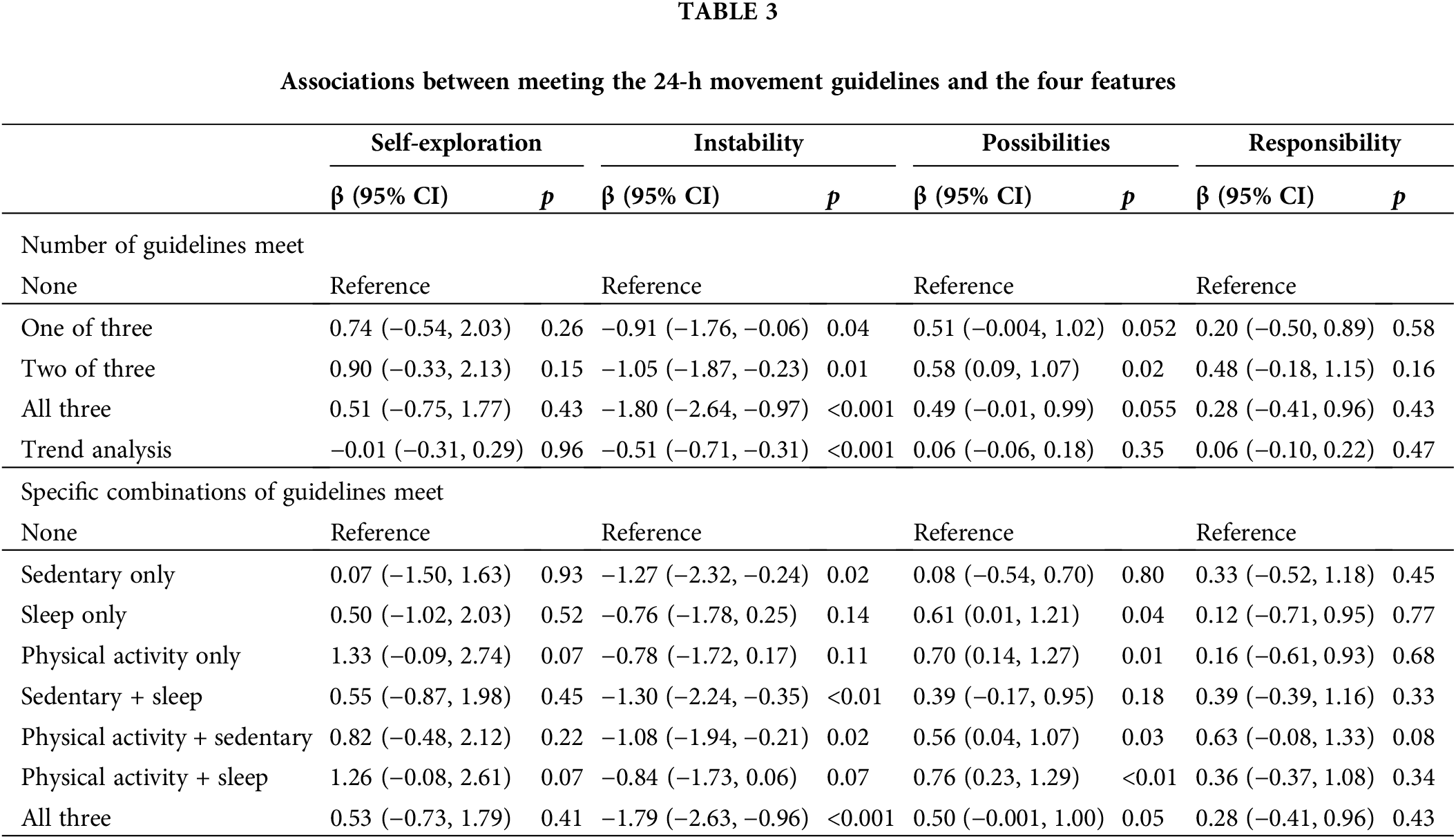

The associations between meeting the 24-h movement guidelines and the four features of emerging adulthood are presented in Table 3. The multiple regression analysis results revealed a significant negative relationship between meeting more guidelines and instability (β = −0.51, 95% CI [−0.71, −0.31], p < 0.001). Meeting one or more guidelines compared with meeting no guideline was significantly associated with lower levels of instability (β = −0.91, 95% CI [−1.76, −0.06], p = 0.04; β = −1.05, 95% CI [−1.87, −0.23], p < 0.01; β = −1.80, 95% CI [−2.64, −0.97], p < 0.001). Additionally, meeting the sedentary behavior (β = −1.27, 95% CI [−2.32, −0.24], p = 0.02; p < 0.01), sedentary behavior + sleep (β = −1.30, 95% CI [(−2.24, −0.35], p < 0.01), PA + sedentary behavior (β = −1.08, 95% CI [−1.94, −0.21], p = 0.02), or PA + sedentary + sleep (β = −1.79, 95% CI [−2.63 − 0.96], p < 0.001) guidelines compared with meeting no guidelinehad negative and significant associations with instability.

Regarding possibilities, no significant association was observed with the number of guidelines met (β = 0.06, p = 0.35). However, the results revealed a positive and significant association with meeting only the PA (β = 0.70, 95% CI [0.14,1.27], p = 0.01), only the sleep (β = 0.61, 95% CI [0.01,1.21], p = 0.04), PA + sedentary behavior (β = 0.56, 95% CI [0.04,1.07], p = 0.01), and PA + sleep (β = 0.76, 95% CI [0.23,1.27], p = 0.01) guidelines. Additionally, meeting all the three guidelines compared with meeting no guideline was marginally associated with a higher level of possibilities (β = 0.50, 95% CI [−0.001, 1.00], p = 0.05).

Regarding self-exploration and responsibility, multiple regression analysis results revealed no significant associations with the number of guidelines met.

This cross-sectional study aimed to examine the associations between meeting the 24-h movement guidelines and four features of emerging adulthood (self-exploration, instability, possibilities, and responsibility) in Chinese emerging adults. The findings generally showed that one-third of emerging adults adhered to all the three 24-h movement guidelines, and positive links were observed between meeting one or more of the 24-h movement guidelines and some of the features of emerging adults. Specifically, meeting all three 24-h movement guidelines was significantly associated with instability in Chinese emerging adulthood. Meeting only the sedentary behavior, sedentary behavior + sleep, or PA + sedentary behavior guidelines compared with meeting no guideline exhibited negative and significant associations with instability. Meeting the guidelines for only PA, only sleep, PA + sedentary behavior, or PA + sleep compared with meeting no guideline exhibited positive and significant associations with possibilities.

The findings of the present study showed that 31.72% of Chinese emerging adults adhered to the 24-h movement guidelines. Our finding is consistent with a previous study reporting that 27% of Chinese college students met the 24-h movement guidelines [32]. The prevalence of meeting the 24-h movement guidelines in our study was also higher than that of college students in the United States (22.1%) [33] and Canada (10.9%) [28]. These variations may be attributed to the different periods of data collection and sample characteristics. For example, Frederick et al. [33] recruited a sample aged 18–25 years compared with 18–29 years in our study. Moreover, Frederick et al.’s study employed aerobic and resistance training as criteria to assess compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines among students. Given the limited adherence to strength exercises (twice a week) [33], the proportion of individuals meeting the 24-h movement guidelines may have been less, which could account for the disparities observed in the findings.

An adulthood is structured as enduring commitments in romantic relationships, living conditions, friendships, and employment, whereas emerging adulthood is characterized by substantial instability as most young adults are yet to establish a stable foundation, navigating through a series of romantic relationships, living conditions, friendship, and frequent changes in jobs before making long-term decisions [6]. For example, friends are considered pivotal in the social lives of emerging adults, serving as trusted confidants, valuable advisors, and active sports partners [5]. In our study, most of the participants were college students who often received instrumental support from their friends, such as facilitating relocations or providing academic assistance in life. Previous studies have reported a negative association between instability (e.g., social support from friends) and PA engagement [34], adequate sleep time [35], and limited sedentary behavior [36] among college students. Consistent with the aforementioned results, we found that the increased number of the 24-h movement guidelines met by the study participants was significantly associated with a lower level of instability in Chinese emerging adults. Specifically, the finding suggests that meeting all the three movement guidelines compared with meeting none of the recommendations was significantly associated with reduced instability. The underlying mechanism may be that the 24-h movement behaviors have biological effects on cortisol secretion and the autonomic nervous system [37]. These biological systems are closely associated with instability. In particular, the stress experienced by emerging adults due to pressure from increasing social competition can induce the release of cortisol, a hormone that plays a critical role in the body’s stress response. When stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, cortisol is released into the bloodstream. This hormone then interacts with receptors in various tissues, including the central nervous system and triggers instability (e.g., depression) [37]. Engaging in regular PA has been associated with a reduction in cortisol levels, attributed to the body’s adaptation to stressors [37]. A previous study has indicated that sleep disruption can induce the release of cortisol in adults. Adequate sleep is crucial for maintaining a healthy cortisol rhythm, and PA has been linked to improved sleep patterns [38]. Therefore, meeting the 24-h movement guidelines appears to offer potential benefits in mitigating instability in emerging adults.

Regarding possibilities, although emerging adulthood is often a period of confusion and complex emotions, most emerging adults are hopeful and optimistic about their future [39]. Previous research has suggested a positive relationship between possibilities/optimism and participation in PA among adults [19]. As an extension of previous results, our study findings suggested that meeting PA or sleep, or PA + sleep guidelines was significantly associated with greater possibilities in emerging adults. For example, Kavussanu et al. found that individuals who were engaged in a higher amount of PA had greater optimism [40]. Hernandez et al. suggested that adequate sleep was significantly associated with higher levels of optimism [41]. These findings imply that meeting PA and sleep guidelines are the most important components for identifying possibilities or maintaining optimism [42,43]. Among people with negative emotions, PA can also promote optimism over time [44]. The possibility that PA and adequate sleep might produce significant positive effects on self-efficacy, which is positively associated with possibilities/optimism, is high. In contrast, individuals with possibilities/optimism are more likely to participate in health-promoting activities (e.g., PA) to combat stress and enhance immune response [42,45]. However, a marginal association was observed between meeting the 24-h movement guidelines and possibilities. Future studies are needed to further understand these findings.

The present study contributes to our understanding of the nuanced associations between adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and specific features of Chinese emerging adults. The results underscore the importance of considering various combinations of movement behaviors in relation to psychological features, providing valuable insights for public health interventions targeting this population. Although the present study depicts the novel and significant association between the 24-h movement guidelines and specific features of emerging adulthood, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cause-and-effect between the 24-h movement guidelines and specific features of emerging adulthood could not be established due to the cross-sectional design used in this study. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and specific features of emerging adulthood. Second, the data were collected using self-reported questionnaires during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, which may affect the accuracy of the results. Future research should use electronic devices (e.g., accelerometers) as a fundamental objective measure of movement behaviors to improve the accuracy of the data. Third, the study population primarily comprised Chinese individuals, which poses challenges in generalizing the present findings to other populations. Furthermore, due to a lack of prior published studies on adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and specific features in emerging adulthood, direct comparisons with other research findings were difficult.

The present study is the first study to explore the association between adherence to the 24-h movement guidelines and specific features of Chinese emerging adults. We found that Chinese emerging adults who adhered to more components of the 24-h movement guidelines had significantly lower levels of instability. However, future studies are warranted to verify our findings to highlight the importance of maintaining a healthy lifestyle in promoting the health of emerging adults.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to all participants to participated in this study.

Funding Statement: This study is supported by the Research on Youth Physical Behavior and Mental Health Problems-Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (2022SB0022).

Author Contributions: Y.Z., J.K., X.L.L.—Conceptualization; methodology; formal analysis; J.K. and X.L. collected data, Y.Z., J.K., X.L., M.Z., and X.L.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data for the present study is avaiable from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Ethics approval was obtianed from the Shenzhen Univesity Human Research Ethics Board (No. PN-2021-048), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no financial or other relationship relevant to the present article.

References

1. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–80. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kuang J, Zhong J, Yang P, Bai X, Liang Y, Cheval B, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the inventory of dimensions of emerging adulthood (IDEA) in China. Int J Clin Heal Psychol. 2023;23:100331. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100331 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bishop AS, Walker SC, Herting JR, Hill KG. Neighborhoods and health during the transition to adulthood: a scoping review. Heal Place. 2020;63:102336. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102336 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MM. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:274–81. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Simone AC, Hamza CA. Examining the disclosure of nonsuicidal self-injury to informal and formal sources: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2020;82:101907. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101907 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Arnett JJ, Žukauskiene R, Sugimura K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:569–76. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Kessler RC, Wang PS. The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:115–29. doi:10.1146/publhealth.2008.29.issue-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:391–400. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wood D, Crapnell T, Lau L, Bennett A, Lotstein D, Ferris M, et al. Emerging adulthood as a critical stage in the life course. Handb Life Course Heal Dev. 2017. 123–43. [Google Scholar]

10. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: the winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

11. Raemen L, Claes L, Verschueren M, van Oudenhove L, Vandekerkhof S, Triangle I, et al. Personal identity, somatic symptoms, and symptom-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors: exploring associations and mechanisms in adolescents and emerging adults. Self Identity. 2023;22:155–80. doi:10.1080/15298868.2022.2063371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hill JM, Lalji M, van Rossum G, van der Geest VR, Blokland AAJ. Experiencing emerging adulthood in the Netherlands. J Youth Stud. 2015;18:1035–56. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1020934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Arnett JJ, Schwab JR. The clark university poll of emerging adults: thriving, struggling, and hopeful. USA: Clark University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

14. Lanctot J, Poulin F. Emerging adulthood features and adjustment: a person-centered approach. Emerg Adulthood. 2018;6:91–103. doi:10.1177/2167696817706024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chatterjee S, Kim J, Chung S. Emerging adulthood milestones, perceived capability, and psychological well-being while transitioning to adulthood: evidence from a national study. Financ Plan Rev. 2021;4:1–17. [Google Scholar]

16. Frech A. Pathways to adulthood and changes in health-promoting behaviors. Adv Life Course Res. 2014;19:40–9. doi:10.1016/j.alcr.2013.12.002 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Chen J, Wang Z, Herold F, Taylor A, Kuang J, Wang T, et al. Relationships between features of emerging adulthood, situated decisions toward physical activity, and physical activity among college students: the moderating role of exercise-intensity tolerance. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023;25:1209–17. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.030539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bu H, He A, Gong N, Huang L, Liang K, Kastelic K, et al. Optimal movement behaviors: correlates and associations with anxiety symptoms among Chinese university students. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:2052. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12116-6 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mulenga G. The relationship between hope optimism physical activity and involuntary absenteeism. In: Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the Southern African Institute of Management Scientists, 2016; pp. 105–18. [Google Scholar]

20. Burns RD, Bai Y, Brusseau TA, Burns RD. Physical activity and sports participation associates with cognitive functioning and academic progression: an analysis using the physical activity and sports participation associates with cognitive functioning and academic progression: an analysis using the combined 2017–2018 National Survey of Children’s Health. Natl Surv Child He Artic J Phys Act Heal. 2020;17(12):1197–204. [Google Scholar]

21. Yang X, Leung AW, Jago R, Yu SC, Zhao WH. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors among Chinese children: recent trends and correlates. Biomed Environ Sci. 2021;34:425–38 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Maher JP, Doerksen SE, Elavsky S, Hyde AL, Pincus AL, Ram N, et al. A daily analysis of physical activity and satisfaction with life in emerging adults. Heal Psychol. 2013;32:647–56. doi:10.1037/a0030129 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. McPhie ML, Rawana JS. The effect of physical activity on depression in adolescence and emerging adulthood: a growth-curve analysis. J Adolesc. 2015;40:83–92. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.01.008 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Peltz JS, Rogge RD, Pugach CP, Strang K. Bidirectional associations between sleep and anxiety symptoms in emerging adults in a residential college setting. Emerg Adulthood. 2017;5:204–15. doi:10.1177/2167696816674551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Edwards MK, Loprinzi PD. Experimentally increasing sedentary behavior results in increased anxiety in an active young adult population. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:166–73. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.045 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chen S, Ma J, Hong J, Chen C, Yang Y, Yang Z, et al. A public health milestone: China publishes new physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines. J Act Sedentary Sleep Behav. 2022;1:1–6. [Google Scholar]

27. Pan N, Lin LZ, Nassis GP, Wang X, Ou XX, Cai L, et al. Adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines in children with mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders: data from the 2016–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Sport Heal Sci. 2023;12:304–11. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2022.12.003 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Brown DMY, Hill RM, Wolf JK. Cross-sectional associations between 24-h movement guideline adherence and suicidal thoughts among Canadian post-secondary students. Ment Health Phys Act. 2022;23:1755–2966. [Google Scholar]

29. Zhao M, Zhang Y, Herold F, Chen J, Hou M, Zhang Z, et al. Associations between meeting 24-hour movement guidelines and myopia among school-aged children: a cross-sectional study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2023;53:101792. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2023.101792 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Taylor A, Kong C, Zhang Z, Herold F, Ludyga S, Healy S, et al. Associations of meeting 24-h movement behavior guidelines with cognitive difficulty and social relationships in children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactive disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2023;17:1–17. [Google Scholar]

31. Macfarlane DJ, Lee CCY, Ho EYK, Chan KL, Chan DTS. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days). J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10:45–51. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.003 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liang K, de Lucena Martins CM, Chen ST, Clark CCT, Duncan MJ, Bu H, et al. Sleep as a priority: 24-hour movement guidelines and mental health of Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthc. 2021;9:1166. doi:10.3390/healthcare9091166 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Frederick GM, Wilson OWA, Peterson KT. Associations between meeting 24-hour movement guidelines and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among college students: differences by gender, race, and sexual orientation. Int J Kinesiol High Educ. 2023;7:309–21. doi:10.1080/24711616.2023.2172489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Scarapicchia TMF, Sabiston CM, Pila E, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Faulkner G. A longitudinal investigation of a multidimensional model of social support and physical activity over the first year of university. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2017;31:11–20. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.03.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Jin Y, Ding Z, Fei Y, Jin W, Liu H, Chen Z, et al. Social relationships play a role in sleep status in Chinese undergraduate students. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:631–8. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.029 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zou L, Wang T, Herold F, Ludyga S, Liu W, Zhang Y, et al. Associations between sedentary behavior and negative emotions in adolescents during home confinement: mediating role of social support and sleep quality. Int J Clin Heal Psychol. 2023;23:100337. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100337 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Silva DAS, Duncan MJ, Kuzik N, Tremblay MS. Associations between anxiety disorders and depression symptoms are related to 24-hour movement behaviors among Brazilian adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2023;339:280–92. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.004 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Vargas I, Lopez-Duran N. Dissecting the impact of sleep and stress on the cortisol awakening response in young adults. Psychoneuroendocrino. 2014;40:10–6. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.10.009 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Gonzales RG. Learning to be illegal: undocumented youth and shifting legal contexts in the transition to adulthood. Am Sociol Rev. 2011;76:602–19. doi:10.1177/0003122411411901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kavussanu M, McAuley E. Exercise and optimism: are highly active individuals more optimistic? J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2016;17:246–58. [Google Scholar]

41. Hernandez R, Vu THT, Kershaw KN, Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD, Carnethon M, et al. The association of optimism with sleep duration and quality: findings from the coronary artery risk and development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Behav Med. 2020;46:100–11. doi:10.1080/08964289.2019.1575179 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Fortier MS, Morgan TL. How optimism and physical activity interplay to promote happiness. Curr Psychol. 2022;41:8559–67. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-01294-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lau EYY, Harry Hui C, Cheung SF, Lam J. Bidirectional relationship between sleep and optimism with depressive mood as a mediator: a longitudinal study of Chinese working adults. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79:428–34. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.09.010 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Pavey TG, Burton NW, Brown WJ. Prospective relationships between physical activity and optimism in young and mid-aged women. J Phys Act Heal. 2015;12:915–23. doi:10.1123/jpah.2014-0070 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Segerstrom SC. Individual differences, immunity, and cancer: lessons from personality psychology. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:92–7. doi:10.1016/S0889-1591(02)00072-7 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools