Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Validity, Reliability, and Measurement Invariance of the Thai Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale and Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale

1 Institute of Allied Health Sciences, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, 701401, Taiwan

2 College of Sports Science and Technology, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, 73170, Thailand

3 Department of Forensic Science, Royal Police Cadet Academy, Nakhon Pathom, 73110, Thailand

4 School of Computing, Engineering, and Digital Technology, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, UK

5 Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Padjadjaran, West Java, 45363, Indonesia

6 Division of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, 60115, Indonesia

7 Faculty of Education, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, 50200, Thailand

8 Faculty of Education, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, 40002, Thailand

9 International Gaming Research Unit, Psychology Department, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, NG1 4FQ, UK

10 Division of Colorectal Surgery, E-DA Hospital, Kaohsiung, 82445, Taiwan

11 College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, 701401, Taiwan

12 Biostatistics Consulting Center, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, 701401, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Usanut Sangtongdee. Email: ; Yi-Kai Kao. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(4), 293-302. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.047023

Received 22 October 2023; Accepted 05 February 2024; Issue published 04 May 2024

Abstract

Background: In recent years, there has been increased research interest in both smartphone addiction and social media addiction as well as the development of psychometric instruments to assess these constructs. However, there is a lack of psychometric evaluation for instruments assessing smartphone addiction and social media addiction in Thailand. The present study evaluated the psychometric properties and gender measurement invariance of the Thai version of the Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS) and Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS). Method: A total of 801 Thai university students participated in an online survey from January 2022 to July 2022 which included demographic information, SABAS, BSMAS, and the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS9-SF). Results: Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) found that both the SABAS and BSMAS had a one-factor structure. Findings demonstrated adequate psychometric properties of both instruments and also supported measurement invariance across genders. Moreover, scores on the SABAS and BSMAS were correlated with scores on the IGDS9-SF. Conclusion: The results indicated that the SABAS and BSMAS are useful psychometric instruments for assessing the risk of smartphone addiction and social media addiction among Thai young adults.Keywords

Smartphones are a new generation of mobile phones, containing many communication applications (e.g., social media) constantly connected to the internet, making many aspects of people’s lives more convenient and social [1–4]. However, evidence indicates that smartphone use can be potentially addictive and/or the applications on them [5,6]. Additionally, prolonged screen time and the internet are associated with physical and psychological problems, low sleep quality, and interrupting individuals’ daily lives [7,8].

Over the past decade, the number of smartphone owners is likely to continue to rise, particularly in Asia [9]. Thailand (where the present study was carried out) is currently 16th globally and 3rd in Southeast Asia for time spent on smartphones with an average of 2.48 h spent a day on social media in 2021 [10]. An online Thai survey reported that there was a 3.4% increase in social media use (up to 81.2%) of the total population in 2022, from 2021 to 2022 (approximately 1.9 million more individuals) [11]. Given Thailand’s relatively high rates of smartphone and social media use [9–12], there is good reason to examine problematic (and potentially addictive) use. Currently, there is only one validated Thai instrument that assesses problematic social media use (Thai Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale [Thai-BFAS]), as well as instruments that assess social media engagement (i.e., Thai-Social Media Engagement Scale [T-SMES]), and problematic internet use more generally (i.e., Thai Internet Addiction Test [Thai-IAT]) [12–14], but none of these assess all types of problematic social media use or assess problematic smartphone use. Therefore, it is important to validate instruments assessing the risk of smartphone addiction and social media addiction (SMA) in general (rather than a specific platform). Moreover, the evidence of online-related addictions in Thailand could be extended with greater choice in available validated instruments.

The Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS) and Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) are commonly used instruments worldwide with established evidence of their psychometric properties [15–17]. The SABAS assesses the risk of smartphone application addiction [18]. The BSMAS assesses the risk of SMA [19,20]. The items of both the SABAS and BSMAS correspond to the six components of addiction (i.e., preoccupation, conflict, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal) proposed by Griffiths [21,22]. Previous studies have indicated that the SABAS and BSMAS have robust reliability and validity, and that both instruments assess the risk of smartphone addiction or SMA [17–19,23,24].

Empirical evidence has shown that the SABAS and BSMAS have equivalence between genders based on measurement invariance tests in a number of languages such as Italian, Chinese, Persian, and Romanian [25–29]. The psychological literature has indicated that gender differences are an important factor in the development of internet-related addictions [30]. For example, males are more likely to have problematic online gaming while females are more likely to have problematic social media use [20]. Research carried out in the Asia-Pacific region has found that online gaming provides competitive elements that make males more vulnerable because they prefer competition over cooperation in gaming contexts [30]. In addition, males are inclined to use online gaming as a coping mechanism for emotional regulation (e.g., stress) [30]. In contrast, females are more inclined to use social media for communication and social interaction [30,31]. Therefore, confirming measurement equivalence of the SABAS and BSMAS by gender is important. It is also important to investigate the factor structures of the SABAS and BSMAS and to assess whether the factor structures are invariant across genders.

The present study is the first study in Thailand to provide preliminary evidence regarding the validation of both the Thai SABAS and BSMAS which assess the severity of smartphone addiction and SMA, respectively. Although both SABAS and BSMAS have been validated in different cultures and languages [25–29], evidence concerning the psychometric properties of Thai SABAS and BSMAS is important. Moreover, there has been an increase in smartphone and social media use in Thailand in recent years (e.g., a 3.4% increase in social media use) [11]. Therefore, Thai individuals may not view the overuse of smartphones and social media as a serious problem. In this regard, validating both the Thai SABAS and BSMAS is important because Thai researchers need to be confident that both instruments can accurately assess SMA and smartphone addiction. In addition, the validation of both scales will provide psychometrically robust instruments for researchers to assess smartphone addiction and SMA in Thailand. The present study is also the first in Thailand to investigate gender differences in smartphone addiction, SMA, and internet gaming disorder (IGD) among young adults using psychometrically validated instruments. Subsequently, the present study’s findings provide novel data and contribute to the literature regarding the understanding of gender comparisons across specific online addictions (i.e., smartphone addiction, SMA, and IGD). Moreover, gender comparisons may highlight different health issues for healthcare providers and help in developing more effective gender-based interventions in tackling smartphone addiction, SMA and IGD.

Based on the previous evidence, it was hypothesized that among Thai university students (i) both the Thai BSMAS and SABAS would have satisfactory validity and reliability (H1), (ii) measurement invariance would be supported across gender (H2), (iii) SMA would be significantly associated with smartphone addiction and IGD (H3), and (iv) there would be significant differences between Thai females and males relating to smartphone addiction, SMA and IGD (H4).

Using convenience sampling, a total of 801 Thai university students (including undergraduates and postgraduates aged ≥18 years) were recruited to participate in an online survey from January 2022 to July 2022. The recruitment was conducted using online social media including Facebook and the university website where participants could access the survey via a QR code to log onto Google Forms. The information on the study’s purpose and requirements was clearly stated on the first page of the online survey. All respondents were required to provide electronic informed consent and those who provided their informed consent could answer the survey questions. The study was approved by the Mahidol University Central Institutional Review Board (MU-MOU COA 2022/006.2001).

Translation procedure for smartphone application-based addiction scale and bergen social media addiction scale

The English versions of the SABAS and BSMAS were translated into the Thai language using a standardized procedure [32]. Forward translations were performed by two bilingual lecturers in sports science and a psychologist who had experience in psychometric scale translations into the Thai language and was fluent in both Thai and English. The two forward translations were done independently and integrated into one forward translation with the agreement of both translators. The backward translations were then carried out by another two linguists who were fluent in both Thai and English. All translated versions of the SABAS and BSMAS were reviewed by a panel including three experts (i.e., a psychologist, a psychiatrist, and a public health expert) to develop the final Thai version of the SABAS and BSMAS.

Participants were asked to provide their age, gender, weight, height, any medical condition(s) or disease(s) they had, course level of study (undergraduate/postgraduate), and marital status. Moreover, participants were asked to estimate the amount of hours spent on social media use (social media frequency [Social-F]), and gaming (gaming frequency [Gaming-F]) over the past week.

Smartphone Application-Based Addiction Scale (SABAS)

The SABAS was used to assess the risk of addiction to smartphone application use [18]. The SABAS comprises six items using a six-point Likert response scale ranging between 1 (“Strongly disagree”) and 6 (“Strongly agree”). An example item is “My smartphone is the most important thing in my life.” The total scores are summed, and higher scores indicate a greater risk of addiction to smartphone application use. One study proposed a cutoff of 21 out of 36 as being at risk of smartphone addiction [33]. The internal consistency of the SABAS has been evaluated in different languages and has been reported to be good. For example: α = 0.84 for the English version, α = 0.79 for the Chinese version, and α = 0.86 for the Persian version [15,18,34].

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS)

The BSMAS was used to assess the risk of SMA over the past year [20]. The BSMAS comprises six items using a five-point Likert response scale ranging between 1 (“Very rarely”) and 5 (“Very often”). An example item is “You spend a lot of time thinking about social media or planning how to use it.” The total scores are summed, and higher scores indicate a greater risk of SMA. One study proposed a cutoff of 19 out of 30 as being at risk of SMA [15]. The internal consistency of the BSMAS has been evaluated in different languages and has been reported to be very good. For example: α = 0.88 for the English version, α = 0.82 for the Chinese version, and α = 0.86 for the Persian version [15,20,27].

Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS9-SF)

The IGDS9-SF was used to assess IGD over the past year [35]. The IGDS9-SF comprises nine items and uses a 5-point Likert response scale ranging between 1 (“Never”) and 5 (“Very often”). An example item is “Do you feel preoccupied with your gaming behavior?”. The total scores are summed, and higher scores indicate a greater risk of IGD. The original developers proposed a cutoff of 36 out of 45 as being at risk of IGD [35]. The internal consistency of the IGDS9-SF has been evaluated in different languages and has been reported to be very good. For example: α = 0.87 for English, α = 0.94 for Chinese, α = 0.90 for Persian [4,35,36].

All data were analyzed using Jeffrey’s Amazing Statistics Program (JASP) version 0.16.3 [37]. Descriptive statistics were performed to analyze the participants’ characteristics and mean scores of the SABAS, BSMAS, and IGDS9-SF. Independent t-tests were performed to analyze the difference in SABAS, BSMAS, and IGDS9-SF scores between males and females. Moreover, p-values < 0.01 were used to indicate statistical significance.

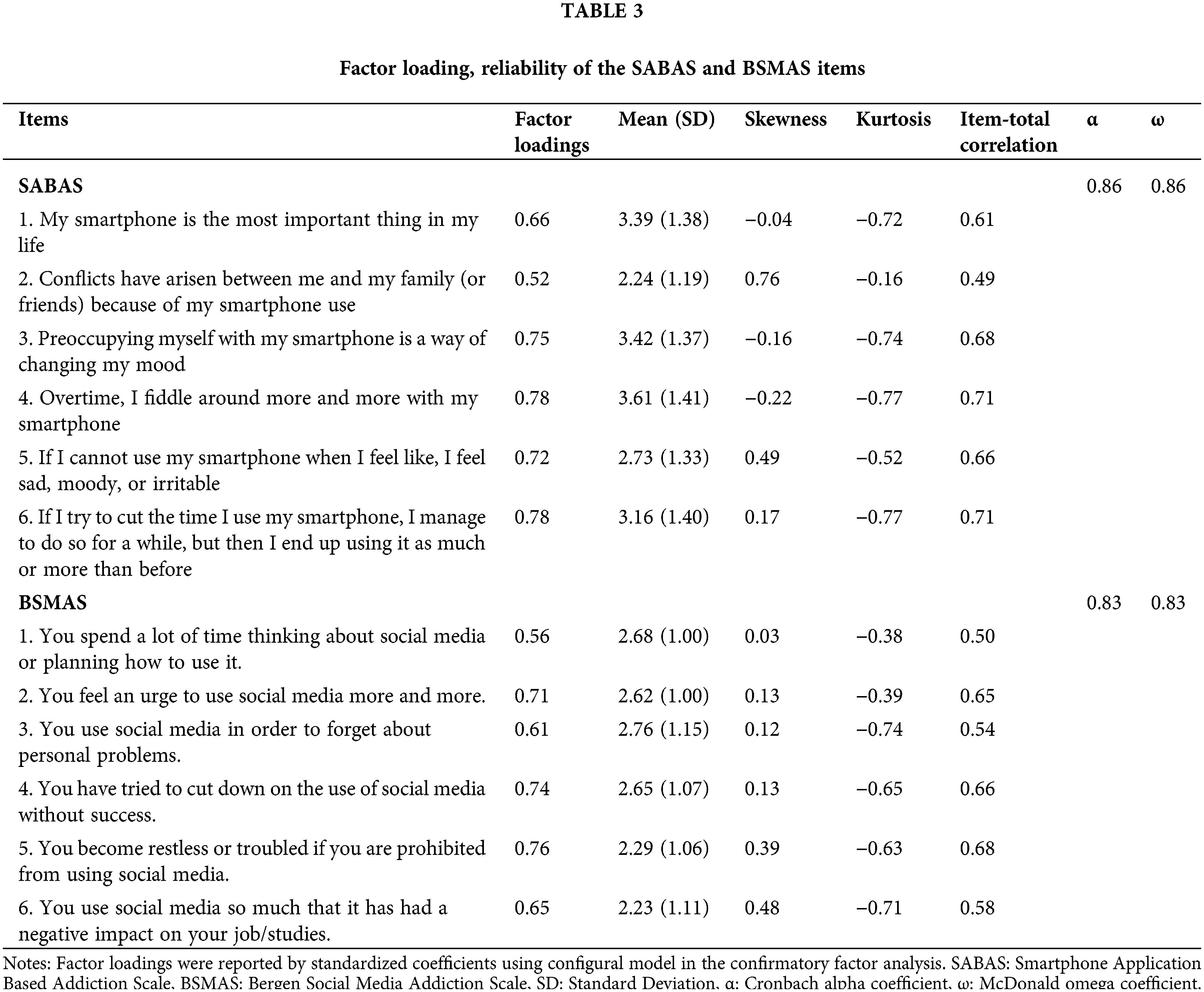

According to previous studies [18,20], both the SABAS and BSMAS have been shown to have a unidimensional structure. In addition, both instruments (SABAS and BSMAS) were developed based on the components model of addiction, which proposes a unidimensional structure [22]. Therefore, based on the prior evidence and the theoretical framework, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out to examine their factor structures. Before performing CFA, item distributions of the SABAS and BSMAS items were checked, and they were normally distributed. Both skewness (SABAS ranging between −0.22 and 0.49; BSMAS ranging between 0.03 and 0.48) and kurtosis had a small value (SABAS ranging between −0.77 and −0.16; BSMAS ranging between −0.74 and −0.38). All SABAS and BSMAS items were examined using factor loadings obtained from CFA and the corrected item-total correlation. The Likert-type response in the instruments was managed by the diagonally weighted least square (DWLS) estimator [38,39]. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω were used to explain the internal consistency and the values are 0.7 or above that indicate being satisfactory [40,41].

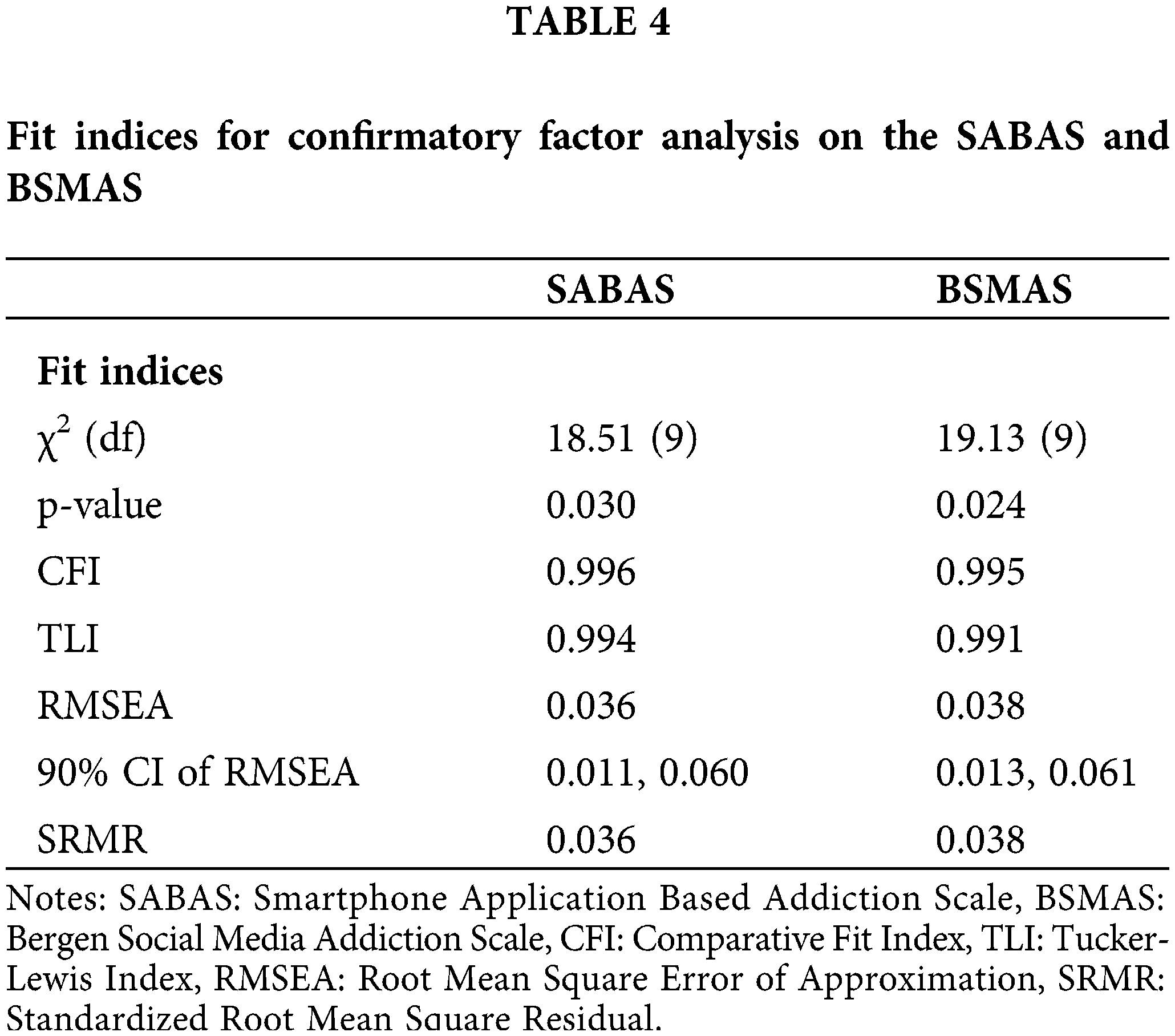

For fit indices, including a nonsignificant χ2 test, a comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.9, a Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > 0.9, a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, and a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) < 0.08 were performed to examine the tested factor structures in the SABAS and BSMAS [42,43]. Factor loadings were obtained from CFA and the values were higher than 0.4 [44].

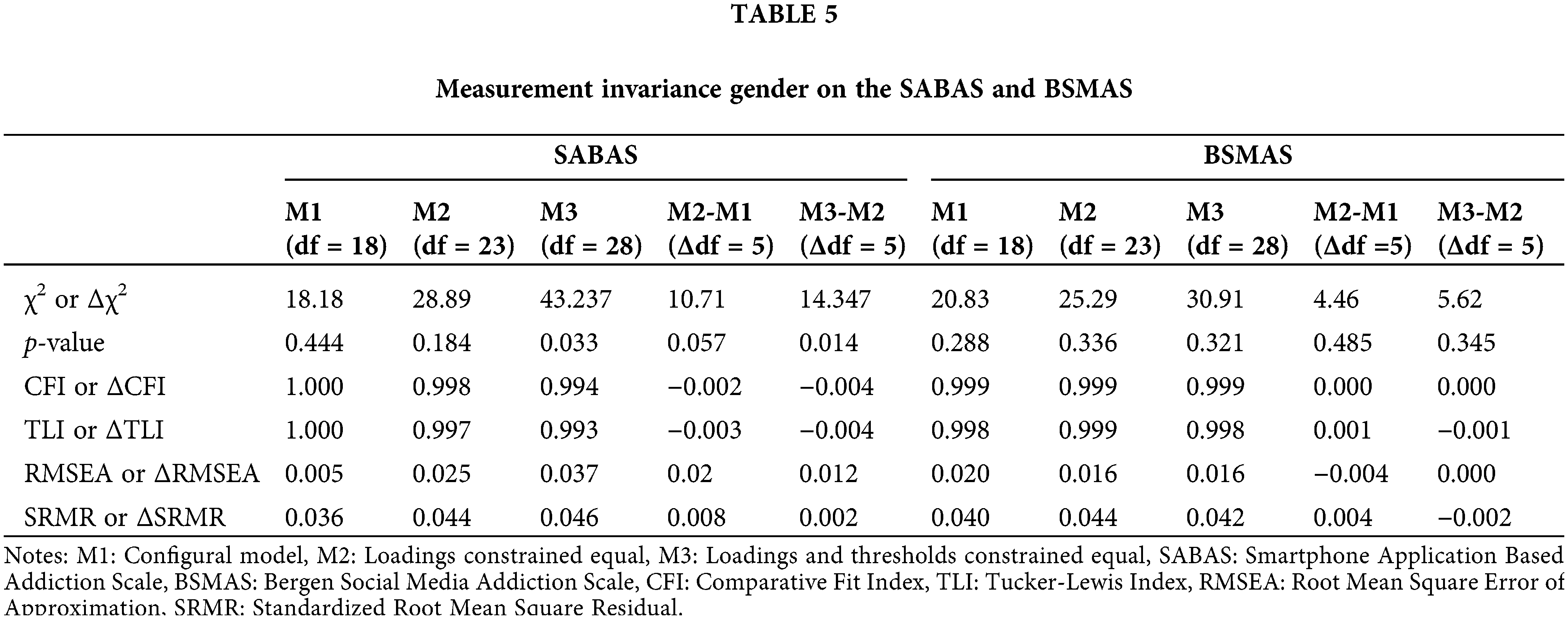

To examine measurement invariance across genders, three nested models (i.e., configural model, metric invariance model, and scalar invariance model) were investigated, using a multigroup CFA (MGCFA) with JASP. Configural invariance tests investigate if the total model fits are similar across groups. Metric invariance tests investigate if factor loadings are equal across groups. The scalar invariance test investigates if factor loadings and item thresholds are constrained equally across groups. Invariance across gender groups is suggested by a non-significant χ2 difference test, and trivial changes in model fit, including all values of ∆CFI > −0.01, ∆RMSEA < 0.02, ∆SRMR < 0.01 between each nested model [15,45]. However, the present study did not use the results of χ2 difference test because a significant difference may be due to the large sample size. Lastly, Pearson’s correlation was used for the correlation analysis. The IGDS9-SF and other important variables (i.e., social media use frequency and gaming frequency) were used for criterion validity analysis of the SABAS and BSMAS. Additionally, p-values < 0.01 were used to indicate statistical significance.

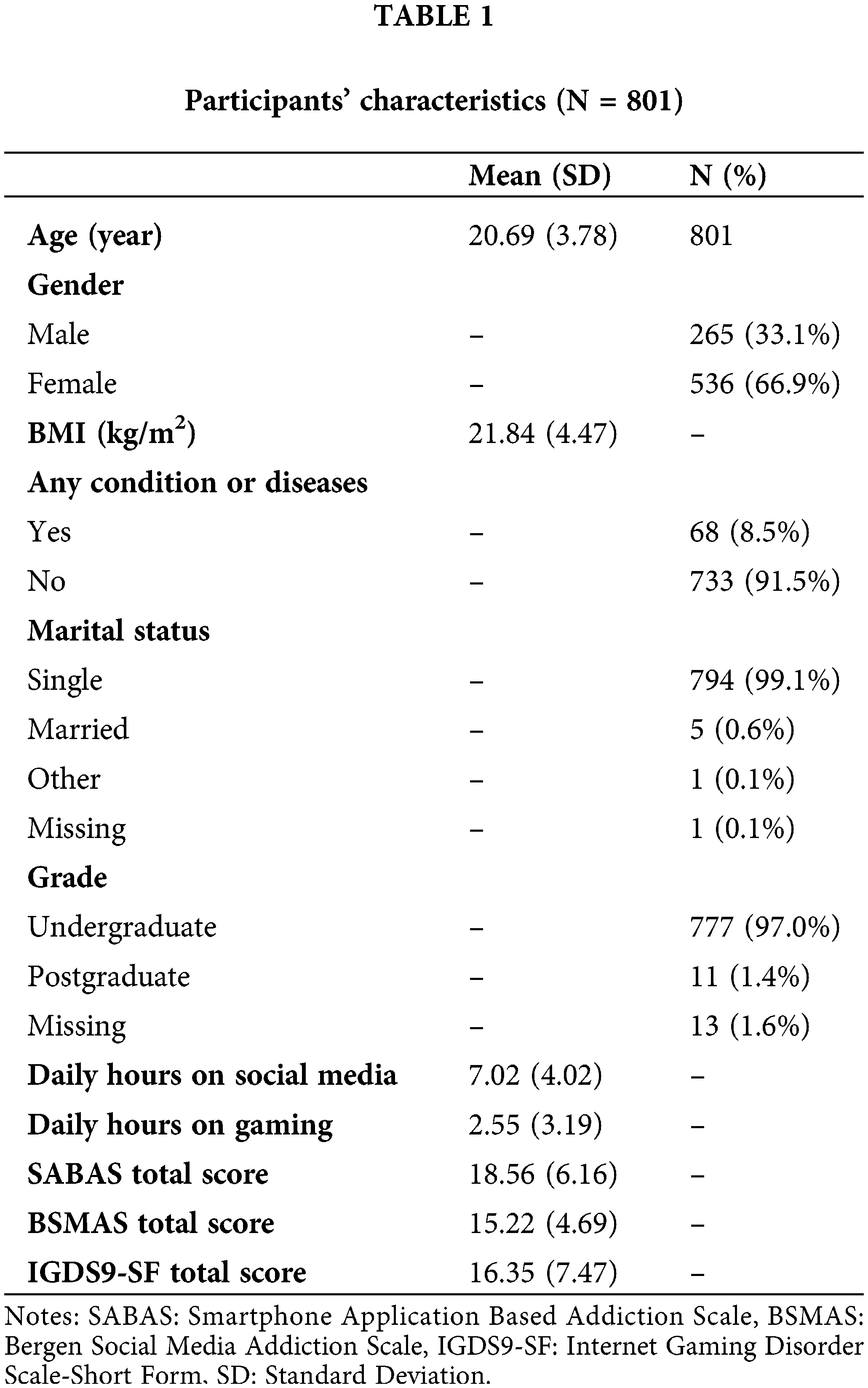

Table 1 shows the participants’ characteristics (n = 801) comprising 536 females (66.9%) and 265 males (33.1%). The participants’ mean age was 20.69 years (SD = 3.78). The mean body mass index of participants was 21.84 kg/m2 (SD = 4.47). Most of the participants reported being in good health (91.5%). They spent an average of 7.02 h a day using social media and 2.55 h a day gaming. Using the cut-offs recommended by the previous studies [15,33,35], the mean scores of the SABAS, BSMAS, and IGDS9-SD were lower than the cut-off points for being at risk of addiction to these behaviors. However, 302 participants were classed as being at risk of smartphone addiction (37.7%), 170 participants were classed as being at risk of SMA (21.2%), and 17 participants were classed as being at risk of IGD (2.1%).

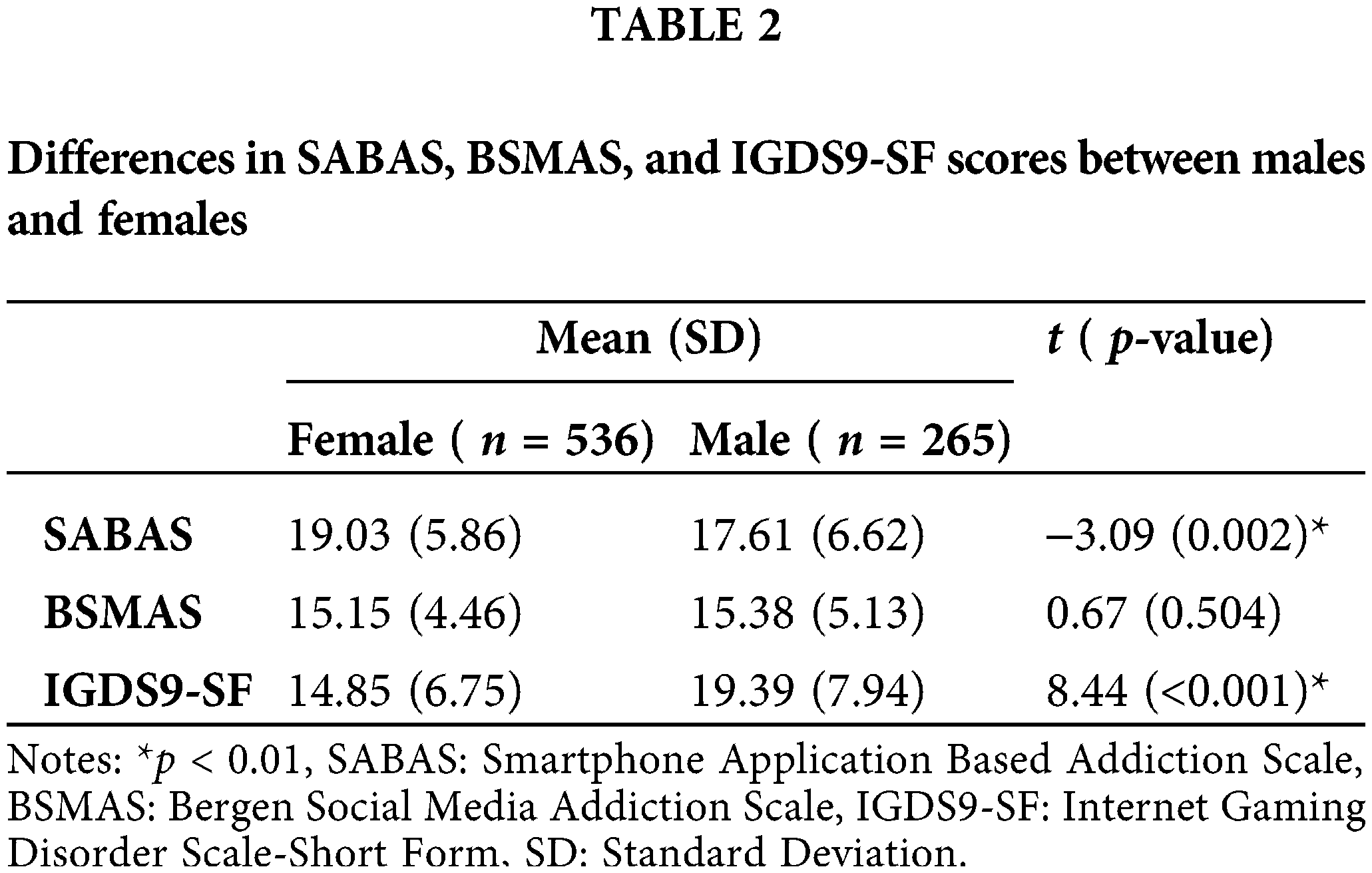

Table 2 shows that females had significantly higher scores than males on the SABAS (19.03 ± 5.86 vs. 17.61 ± 6.62, p = 0.002). Males had significantly higher scores than females on the IGDS9-SF (19.39 ± 7.94 vs. 14.85 ± 6.75, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between males and females in BSMAS scores (15.15 ± 4.46 vs. 15.38 ± 5.13).

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics and reliability coefficients for the SABAS and BSMAS items. Acceptable psychometric properties for both SABAS and BSMAS items were found in the CFA with a confirmed unidimensional structure for both scales. In addition, the results of Table 3 indicated that all six items of the SABAS and BSMAS presented good factor loadings in the CFA (SABAS = 0.52–0.78; BSMAS = 0.56–0.76) with satisfactory item-total correlations (SABAS = 0.49–0.71; BSMAS = 0.50–0.68). More specifically, Table 4 shows good fit indices for SABAS and BSMAS in the CFA results. For the SABAS: CFI = 0.996; TLI = 0.994; RMSEA = 0.036; and SRMR = 0.036. For the BSMAS; CFI = 0.995; TLI = 0.991; RMSEA = 0.038; and SRMR = 0.038. Moreover, internal consistencies of both the SABAS and BSMAS were very good (Cronbach’s α = 0.86 and McDonald’s ω = 0.86 for SABAS; Cronbach’s α = 0.83 and McDonald’s ω = 0.83 for BSMAS).

Table 5 shows the invariance of the SABAS, and BSMAS across gender groups. The indicators of model fit presented satisfactory measurement invariance. For the SABAS, the measurement invariance was supported, with all data fit indices (∆CFI, ∆RMSEA, ∆SRMR) being acceptable between each model except for a significant χ2 difference (comparing M3 and M2 models). Moreover, the BSMAS had its measurement invariance supported, with non-significant χ2 difference and all data fit indices (∆CFI, ∆RMSEA, ∆SRMR) being satisfactory.

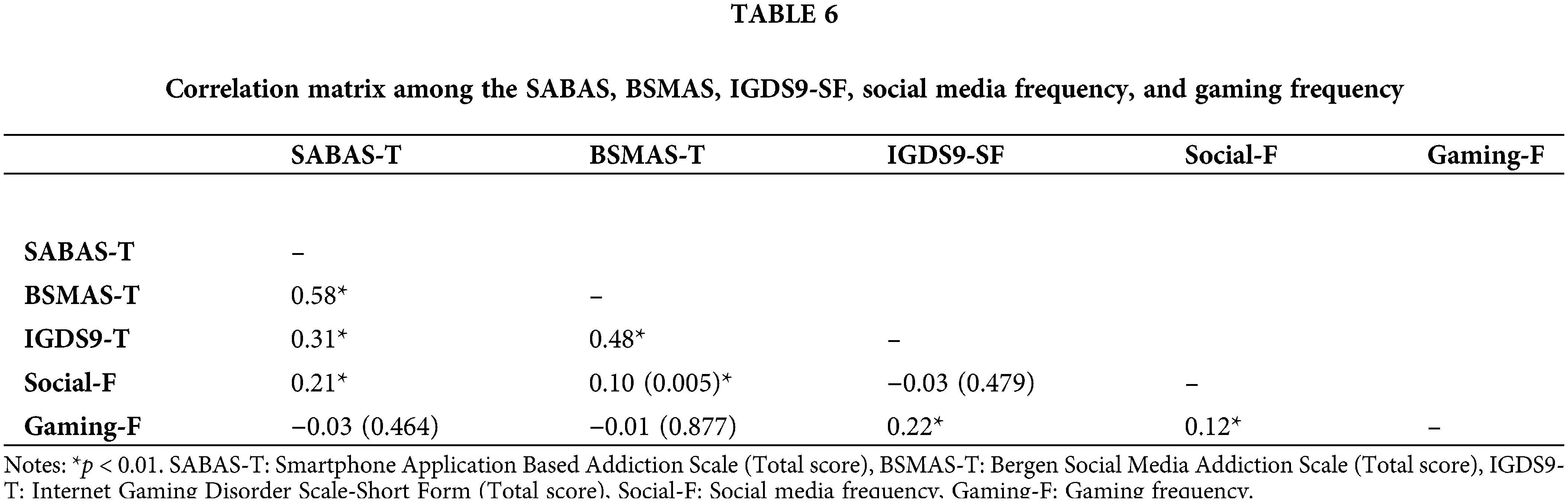

Table 6 shows the correlation matrix regarding scores on the SABAS, BSMAS, and IGDS9-SF, as well as social media use frequency and gaming frequency. SABAS scores were significantly correlated with BSMAS scores (r = 0.58; p < 0.001), IGDS9-SF scores (r = 0.31; p < 0.001) and social media frequency (r = 0.21; p < 0.001). BSMAS scores were significantly correlated with IGDS9-SF scores (r = 0.48; p < 0.001), and social media use frequency (r = 0.10; p = 0.005). IGDS9-SF scores were significantly correlated with gaming frequency (r = 0.22; p < 0.001). Moreover, social media use frequency was significantly correlated with gaming frequency (r = 0.12; p < 0.001).

The results of the present study are in line with the three hypotheses. First, both Thai versions of SABAS and BSMAS presented satisfactory validity and reliability (H1). Second, their measurement invariance was supported across gender (H2). Third, SMA was significantly associated with smartphone addiction and IGD (H3). Finally, significant differences were found between females and males in regard to smartphone addiction and IGD (H4) whereas there were no significant gender differences in SMA. Therefore, the findings indicated that the Thai version of SABAS and BSMAS appear to be valid, reliable, and gender-invariant scales to examine the risk of developing smartphone addiction and SMA among Thai young adults. Additionally, the present study had similar findings to those of other studies confirming that the SABAS and BSMAS had a one-factor structure together with significant correlations with the IGDS9-SF [15,29]. The results suggest that individuals in different countries (including those in Thailand) appear to have equivalent interpretations of SABAS and BSMAS items. Therefore, it is concluded that SABAS and BSMAS are psychometrically robust instruments across different populations. Moreover, Thai males and females tended to have different levels of smartphone addiction and IGD but similar levels of SMA.

Consistent with the findings from previous studies [15,18,27,29], both the SABAS and BSMAS had very good internal consistencies and one-factor structures. More specifically, the present findings demonstrated that both the SABAS and BSMAS had a unidimensional structure and showed very good psychometric properties which were comparable with the original version (α = 0.86 for SABAS; α = 0.88 for BSMAS). In addition, the internal consistency of the Thai BSMAS was found to be comparable with the previous versions of the BSMAS, BFAS and the Thai BFAS (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) [13,18–20]. Given the good psychometric properties found in the present study, the Thai versions of the SABAS and BSMAS could be additional options for healthcare providers assessing SMA and smartphone addiction in addition to the currently existing Thai-BFAS, T-SMES, and Thai-TAI [12–14].

Additionally, the present study is one of the few that has compared smartphone addiction, SMA, and IGD simultaneously among Thai young adults. Consistent with the previous findings outside of the Thai population, results indicated that females had higher levels of smartphone addiction than males [46–48]. A previous review indicated that the purposes underlying the time spent using smartphones were different between females and males [48]. More specifically, it has been reported that females are more likely to use smartphones as tools to maintain intense social relationships (i.e., phone calls, texting, and social networking) and spend greater time on each of these smartphone-related applications whereas males use smartphones less for maintaining relationships and more for such activities as accessing news feeds [48,49]. Because spending time socially interacting is usually more time-intensive than activities such as reading social media news feeds, females are thus more likely than males to be addicted to smartphone use. Furthermore, the results indicated that males had higher levels of IGD than females which concurs with prior studies, almost all have shown that gaming disorder is more highly prevalent among males [46–48]. The literature has indicated that online gaming can be a coping mechanism to escape from unpleasant situations and helps improve individuals’ self-esteem, decreases stress, alleviates poor mood, and enhances social contact [47,50]. In addition, the family has the most important role in Asian culture from childhood to adulthood (which is especially important given the study was carried out among Thai students) [51].

A previous Taiwanese study indicated that Asian parents protect and constrain their daughters’ leisure activities more than their sons (e.g., daughters should not stay outside overnight). Therefore, Asian females are likely to be constrained from spending time on gaming compared to Asian males [47]. Similarly, Thai females are likely to experience greater day-to-day supervision from their parents which results in lower levels of IGD compared to males. However, further study is needed to address the causal relationship between IGD and gender differences among Thai individuals. The present study also found no differences between males and females in terms of SMA, which does not concur with previous findings [52]. A meta-analysis reported that females were more inclined to spend greater amounts of time on social media than males because females enjoy social interactions more than males [52]. However, another review reported that the relationship between gender and SMA is complex because of moderating effects from confounding variables (e.g., psychological distress and cultural variables) [53]. Therefore, it is possible that Thai males and females have similar levels of SMA. However, future studies are needed for corroboration.

In line with previous studies [24,26,27,34], the present study’s findings indicated the factorial structures of the SABAS and BSMAS were similar across genders. This means that when using the SABAS and BSMAS to assess addictions to smartphones and social media, gender will not be a factor influencing the respondents’ interpretations of individual items. However, as previously suggested, further studies should confirm the present findings in other age-related and cross-cultural contexts to verify the validity and reliability of the SABAS and BSMAS [24,34].

The results here provide further support for the notion made in previous studies that scores on the SABAS and BSMAS have strong and positive associations with IGDS9-SF scores [15,16,24,34]. A recent study indicated that SMA and IGD were both associated with psychological distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress) [26]. Nevertheless, some studies have argued that types of specific internet addiction (i.e., SMA, smartphone addiction, IGD) are different from each other [15,54]. In other words, there are fundamental differences between types of internet addiction, and the SABAS, BSMAS, and IGDS9-SF assess different types of internet addictions [15,55]. Moreover, the literature has suggested that further studies should examine overlapping and important components of specific internet addiction which could prevent the different potential risks of internet-related addictions [6].

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the participants consisted of Thai university students, therefore the findings are difficult to generalize to more diverse cultural demographics, age groups (e.g., children, adults), and populations other than university students. Second, the present study was a cross-sectional design and had weak evidence concerning any causal relationships among the studied variables. Third, the participants were recruited using a self-selected convenience sampling method, and the results may be biased due to memory recall and/or social desirability. Moreover, the risk of SMA, smartphone addiction, and IGD were identified through self-report instruments. Therefore, single-rater bias may exist, and future studies are encouraged (where possible) to use clinical diagnosis to replace self-reported psychological distress to avoid this type of bias. Fourth, the present study had more female participants (66.9%) than male participants (33.1%). Therefore, the imbalanced gender distribution may limit the generalizability of the findings. Fifth, the present study used the addiction risk cut-off points of SABAS, BSMAS and IGDS9-SF recommended in previous studies not on Thai populations [15,33,35]. However, these cut-offs were developed in other populations and may not directly equate to Thai university students. Therefore, the severity estimations of the SMA, smartphone addiction, and IGD for the present sample might not be accurate. Future studies are needed to determine an accurate cut-off of these instruments in screening for the risk of smartphone addiction, SMA and IGD for the Thai population. Finally, the present study collected data using online surveys. Such data may not be of the highest quality due to the aforementioned limitations. However, the data quality appears to be acceptable given the results of psychometric properties of SABAS and BSMAS concur with the findings of previous studies [15,18,27,29]. Nevertheless, future studies need to consider using control check questions to further ensure data quality.

In the present study, the Thai SABAS and BSMAS had very good psychometric properties and can be used to assess internet-related addictions (i.e., smartphone addiction and SMA) among Thai university students. Moreover, the measurement invariance of the SABAS and BSMAS across gender was supported. Therefore, the SABAS and BSMAS can be additional tools for Thai healthcare providers and researchers to use to assess smartphone addiction and SMA. However, the present findings were obtained using a university student sample. Therefore, it is recommended that the psychometric properties of the Thai SABAS and BSMAS be evaluated using more diverse population groups.

Acknowledgement: We sincerely thank all the teaching faculty and research assistants who helped in the present study. We also thank all the participants for their involvement in the present study.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 110-2410-H-006-115), the Higher Education Sprout Project, Ministry of Education to the Headquarters of University Advancement at National Cheng Kung University (NCKU), the 2021 Southeast and South Asia and Taiwan Universities Joint Research Scheme (NCKU 31), and the E-Da Hospital (EDAHC111004).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Kamolthip Ruckwongpatr, Chirawat Paratthakonkun, Usanut Sangtongdee, Yi-Kai Kao, Chung-Ying Lin; data collection: Kamolthip Ruckwongpatr, Chirawat Paratthakonkun, Chung-Ying Lin; analysis and interpretation of results: Kamolthip Ruckwongpatr, Chirawat Paratthakonkun, Chung-Ying Lin; draft manuscript preparation: Kamolthip Ruckwongpatr, Chung-Ying Lin; editing and critical review: Mark D. Griffiths; paper review: all authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Approval: The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects in Mahidol University Central Institutional Review Board (MU-MOU COA 2022/006.2001). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Soyer F, Tolukan E, Dugenci A. Investigation of the relationship between leisure satisfaction and smartphone addiction of university students. Asian J Educ. 2019;5(1):229–35. doi:10.20448/journal.522.2019.51.229.235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fook CY, Narasuman S, Abdul Aziz N, Tau Han C. Smartphone usage among university students. Asian J Univ Educ. 2021;7(1):282–91. [Google Scholar]

3. Shaahmadi Z, Jouybari TA, Lotfi B, Aghaei A, Gheshlagh RG. The validity and reliability of Persian version of smartphone addiction questionnaire in Iran. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2021;16(1):69. doi:10.1186/s13011-021-00407-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Hawi NS, Samaha M. The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2017;35(5):576–86. doi:10.1177/0894439316660340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kwon M, Kim DJ, Cho H, Yang S. The smartphone addiction scale: development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83558. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Social networking sites and addiction: ten lessons learned. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):311. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Chen IH, Pakpour AH, Leung H, Potenza MN, Su JA, Lin CY, et al. Comparing generalized and specific problematic smartphone/internet use: longitudinal relationships between smartphone application-based addiction and social media addiction and psychological distress. J Behav Addict. 2020;9(2):410–9. doi:10.1556/2006.2020.00023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Tangmunkongvorakul A, Musumari PM, Tsubohara Y, Ayood P, Srithanaviboonchai K, Techasrivichien T, et al. Factors associated with smartphone addiction: a comparative study between Japanese and Thai high school students. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0238459. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Degenhard J. Forecast of the number of smartphone users in Asia from 2013 to 2028. Available from: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1146878/smartphone-users-in-asia. [Accessed 2021]. [Google Scholar]

10. Digital Marketing Institute. Social media: what countries use it most & what are they using? Available from: https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/blog/social-media-what-countries-use-it-most-and-what-are-they-using. [Accessed 2021]. [Google Scholar]

11. Kemp S. Digital 2022: Thailand. Available from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-thailand. [Accessed 2022]. [Google Scholar]

12. Wisessathorn M, Pramepluem N, Kaewwongsa S. Factor structure and interpretation on the Thai-social media engagement scale (T-SMES). Heliyon. 2022;8(7):e09985. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Phanasathit M, Manwong M, Hanprathet N, Khumsri J, Yingyeun R. Validation of the Thai version of Bergen Facebook addiction scale (Thai-BFAS). J Med Assoc Thai. 2015;98(Suppl. 2):S108–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Neelapaijit A, Pinyopornpanish M, Simcharoen S, Kuntawong P, Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T. Psychometric properties of a Thai version internet addiction test. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):69. doi:10.1186/s13104-018-3187-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Leung H, Pakpour AH, Strong C, Lin YC, Tsai MC, Griffiths MD, et al. Measurement invariance across young adults from Hong Kong and Taiwan among three internet-related addiction scales: Bergen social media addiction scale (BSMASsmartphone application-based addiction scale (SABASand internet gaming disorder scale-short form (IGDS-SF9) (Study Part A). Addict Behav. 2020;101(2):105969. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Chen IH, Strong C, Lin YC, Tsai MC, Leung H, Lin CY, et al. Time invariance of three ultra-brief internet-related instruments: smartphone application-based addiction scale (SABASBergen social media addiction scale (BSMASand the nine-item internet gaming disorder scale-short form (IGDS-SF9) (Study Part B). Addict Behav. 2020;101(2):105960. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Tung SEH, Gan WY, Chen JS, Ruckwongpatr K, Pramukti I, Nadhiroh SR, et al. Internet-related instruments (Bergen social media addiction scale, smartphone application-based addiction scale, internet gaming disorder scale-short form, and nomophobia questionnaire) and their associations with distress among Malaysian university students. Healthcare. 2022;10(8):1448. doi:10.3390/healthcare10081448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Csibi S, Griffiths MD, Cook B, Demetrovics Z, Szabo A. The psychometric properties of the smartphone application-based addiction scale (SABAS). Int J Ment Health Addict. 2018;16(2):393–403. doi:10.1007/s11469-017-9787-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Andreassen CS, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, et al. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(2):252–62. doi:10.1037/adb0000160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501–17. doi:10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Griffiths MD. Internet addiction—time to be taken seriously? Addict Res. 2000;8(5):413–8. doi:10.3109/16066350009005587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Griffiths MD. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use. 2005;10(4):191–7. doi:10.1080/14659890500114359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cerniglia L, Griffiths MD, Cimino S, De Palo V, Monacis L, Sinatra M, et al. A latent profile approach for the study of internet gaming disorder, social media addiction, and psychopathology in a normative sample of adolescents. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:651–9. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S211873. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Monacis L, de Palo V, Griffiths MD, Sinatra M. Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen social media addiction scale. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(2):178–86. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Chen IH, Ahorsu DK, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Lin CY, Chen CY. Psychometric properties of three simplified Chinese online-related addictive behavior instruments among mainland Chinese primary school students. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:875. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Yue H, Zhang X, Cheng X, Liu B, Bao H. Measurement invariance of the Bergen social media addiction scale across genders. Front Psychol. 2022;13:879259. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lin CY, Broström A, Nilsen P, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. Psychometric validation of the Persian Bergen social media addiction scale using classic test theory and Rasch models. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(4):620–9. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Stănculescu E. The Bergen social media addiction scale validity in a Romanian sample using item response theory and network analysis. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;21(4):1–18. doi:10.1007/s11469-021-00732-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Yam CW, Pakpour AH, Griffiths MD, Yau WY, Lo CM, Ng JMT, et al. Psychometric testing of three Chinese online-related addictive behavior instruments among Hong Kong university students. Psychiatr Q. 2019;90(1):117–28. doi:10.1007/s11126-018-9610-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Tang CS, Koh YW, Gan Y. Addiction to internet use, online gaming, and online social networking among young adults in China, Singapore, and the United States. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2017;29(8):673–82. doi:10.1177/1010539517739558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Su W, Han X, Yu H, Wu Y, Potenza MN. Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;113(1):106480. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3186–91. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Mamun MA, Rayhan I, Akter K, Griffiths MD. Prevalence and predisposing factors of suicidal ideation among the university students in Bangladesh: a single-site survey. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2020;20(4):1–14. doi:10.1007/s11469-020-00403-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lin CY, Imani V, Broström A, Nilsen P, Fung XC, Griffiths MD, et al. Smartphone application-based addiction among Iranian adolescents: a psychometric study. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019;17(4):765–80. doi:10.1007/s11469-018-0026-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Pontes HM, Griffiths MD. Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;45(2):137–43. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wu TY, Lin CY, Årestedt K, Griffiths MD, Broström A, Pakpour AH. Psychometric validation of the Persian nine-item internet gaming disorder scale-short form: does gender and hours spent online gaming affect the interpretations of item descriptions? J Behav Addict. 2017;6(2):256–63. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. JASP Team. JASP version 0.16.3. Available from: https://jasp-stats.org. [Accessed 2022]. [Google Scholar]

38. Wu TH, Chang CC, Chen CY, Wang JD, Lin CY. Further psychometric evaluation of the self-stigma scale-short: measurement invariance across mental illness and gender. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117592. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Nestler S. A Monte Carlo study comparing PIV, ULS and DWLS in the estimation of dichotomous confirmatory factor analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2013;66(1):127–43. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8317.2012.02044.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 2nd. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

41. Kalkbrenner MT. Alpha, omega, and H i nternal consistency reliability estimates: reviewing these options and when to use them, counseling outcome research and evaluation. Couns Outcome Res Eval. 2023;14(1):77–88. doi:10.1080/21501378.2021.1940118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. McDonald RP, Ho MHR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):64–81. doi:10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Hair JF, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis. 8th. India: Cengage; 2018. [Google Scholar]

45. Lin CY, Imani V, Cheung P, Pakpour AH. Psychometric testing on two weight stigma instruments in Iran: weight self-stigma questionnaire and weight bias internalized scale. Eat Weight Disord. 2020;25(4):889–901. doi:10.1007/s40519-019-00699-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chiu SI, Hong FY, Chiu SL. An analysis on the correlation and gender difference between college students’ internet addiction and mobile phone addiction in Taiwan. ISRN Addict. 2013;2013(5):360607. doi:10.1155/2013/360607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CC, Chen SH, Yen CF. Gender differences and related factors affecting online gaming addiction among Taiwanese adolescents. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(4):273–7. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000158373.85150.57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. De-Sola Gutiérrez J, de Fonseca FR, Rubio G. Cell-phone addiction: a review. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7(6):175. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Roberts JA, Yaya LH, Manolis C. The invisible addiction: cell-phone activities and addiction among male and female college students. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(4):254–65. doi:10.1556/JBA.3.2014.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wang CW, Chan CL, Mak KK, Ho SY, Wong PW, Ho RT. Prevalence and correlates of video and internet gaming addiction among Hong Kong adolescents: a pilot study. Sci World J. 2014;2014(6):874648. doi:10.1155/2014/874648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Yadegarfard M, Meinhold-Bergmann ME, Ho R. Family rejection, social isolation, and loneliness as predictors of negative health outcomes (depression, suicidal ideation, and sexual risk behavior) among Thai male-to-female transgender adolescents. J LGBT Youth. 2014;11(4):347–63. doi:10.1080/19361653.2014.910483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Tifferet S. Gender differences in social support on social network sites: a meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2020;23(4):199–209. doi:10.1089/cyber.2019.0516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Baloğlu M, Şahin R, Arpaci I. A review of recent research in problematic internet use: gender and cultural differences. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020;36:124–9. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.05.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Pontes HM, Griffiths MD. Internet addiction disorder and internet gaming disorder are not the same. J Addict Res Ther. 2014;5(4):e124. doi:10.4172/2155-6105.1000e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wong HY, Mo HY, Potenza MN, Chan MNM, Lau WM, Chui TK, et al. Relationships between severity of internet gaming disorder, severity of problematic social media use, sleep quality and psychological distress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):1879. doi:10.3390/ijerph17061879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools