Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Emergence of Loving Pedagogy in the L2 Affective Domain: How Affective Pedagogy Accounts for Chinese EFL Teachers’ Professional Success and Job Satisfaction?

1 School of Marxism, Changshu Institute of Technology, Suzhou, 215500, China

2 School of Foreign Languages, Changshu Institute of Technology, Suzhou, 215500, China

* Corresponding Author: Xinpeng Wang. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(3), 239-250. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029611

Received 28 February 2023; Accepted 01 June 2023; Issue published 08 April 2024

Abstract

The success of teachers in professional environments has a desirable influence on their mental condition. Simply said, teachers’ professional success plays a crucial role in improving their mental health. Due to the invaluable role of professional success in teachers’ mental health, personal and professional variables helping teachers succeed in their profession need to be uncovered. While the role of teachers’ personal qualities has been well researched, the function of professional variables has remained unknown. To address the existing gap, the current investigation measured the role of two professional variables, namely job satisfaction and loving pedagogy, in Chinese EFL teachers’ professional success. To do this, three validated scales were provided to 1591 Chinese EFL teachers. Participants’ answers to the questionnaires were analyzed using the Spearman correlation test and structural equation modeling. The data analysis demonstrated a strong, positive link between the variables. Moreover, loving pedagogy was found to be the positive, strong predictor of Chinese EFL teachers’ job satisfaction and professional success. The findings of the current inquiry may help educational administrators enhance their instructors’ professional success, which in turn promotes their mental and psychological conditions at work.Keywords

Regarding the background of loving pedagogy, in his book Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions (2001), Nussbaum [1] argued against the narrow conception of knowledge by proposing that “emotions always involve thought of an object continued with the thought of the object’s salience or importance; in that sense, they always involve appraisal and evaluation” [1]. As she maintained, recognizing the contribution of emotions to choices in life is realized when they are brought back in pedagogy. She further explained that “emotions look at the world from the subject’s viewpoint, mapping events onto the subject’s sense of personal importance or value” [1]. Concerning the origin of loving pedagogy, it is mainly rooted in the difference between technical knowledge and practical knowledge [2]. Technical knowledge is limited to the transfer of technical information from teachers to their students. On the other hand, practical knowledge involves the complex interplay of emotion and cognition in the interaction between students and their teachers. The practical knowledge is intertwined with the concept of affective pedagogy with an emphasis on emotions and the outcomes of learning. In this type of pedagogy, the interaction between teachers and their students is pivoted on dramatic friendship. Dramatic friendship implies the wholehearted relation, sympathy, faithfulness, delight, and the development of mutual interest between individuals in their interactions. As noted by Oakeshott [2], dramatic friendship should not be mixed with utilitarian friendship, in which the interaction between individuals might be shaped based on a calculation of their uses and benefits for each other. What shapes dramatic friendship is the quality of Agape or selfless love based on which individuals welcome the capacity to build altruistic, liberating, deep, and open love. Thus, agape denotes that in their practice of affective pedagogy, teachers should raise their self-awareness, self-confidence, and self-lessness in manners enabling them to get involved in healthy and intimate relationships with their students. This deep and personal interplay of teachers and students guarantees the outcomes of learning as it is both intellectual and emotional. It is worth noting that due to the technological advances in the past decades, many contemporary schools have drawn their attention to the application of technological affordances in their language teaching. However, technological devices cannot replace dramatic friendship in teacher-student interactions because it might lead to dehumanized pedagogy and loveless teaching. As a result, intellectual orientation might be separated from the emotional one in second or foreign pedagogy. Intellectual pedagogy seems to assume that intellect should be viewed as a cold-blooded affair where emotions are sterilized.

Thus, it can be understood that affective pedagogy does not aim to cultivate an atmosphere of obedience in the class but to enhance a nurturing environment in which language learners engage responsibly in their language learning process. In this environment, language learners develop their capacities to interact sympathetically. Loving pedagogy embraces the emotional experiences of all language learners including their complexities in terms of the interplay of emotional and cognitive sides in teacher-learner classroom interactions. That is, loving pedagogy implies that without the cultivation of these emotional experiences, the outcomes of learning will be faced with emotional constipation and intellectual truncation. This is quite consistent with Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, based on which the experience of positive emotions Sets the stage for broadening mental capacities, attentional scope, and cognitive development. It seems that the emergence of loving pedagogy in the L2 affective domain of SLA, it can account for the professional success and job satisfaction of language teachers [3]. What is missing in the literature on language teachers’ professional success is the orientation of their pedagogy in their profession. Recent research on L2 effective variables have indicated that emotions in language classes are contagious and are transferred from language teachers to their students [4,5]. Therefore, adopting a loving pedagogy in the classroom can let us reconsider the accounts for language teachers’ success via the incorporation of loving pedagogy in this construct. Put another way, the professional success and satisfaction of language teachers should be doubted once their learners’ emotions are not cared for or cultivated. Thus, having introduced the concept of loving pedagogy in the L2 affective domain, this study aims to discuss how language teachers’ professional success and satisfaction can be accounted for by this construct.

Affective pedagogy from the perspective of language teachers’ professional success

The success or effectiveness of teachers can drastically influence the adequacy of educational environments [6]. Because of this, teachers’ professional success has always been of high importance to educational authorities. Teacher professional success, also called teacher occupational success, deals with “the degree to which teachers meet the instructional objectives set by themselves or educational administrators” [7]. In the language education realm, teacher professional success has to do with how effectively language teachers instruct the language learning materials. According to the American Association of School Administrators (AASA), successful teachers are skilled at presenting academic subjects, managing the learning environment, and establishing intimate relationships with pupils [8]. For Derakhshan et al. [9], successful teachers are those who can engage learners in classroom activities, support them in the learning process, and lead them towards academic success. In this regard, Zhao et al. [10] also articulated that a successful teacher is one who can favorably influence his/her learners’ achievement.

As put forward by Wossenie [11] and Wang et al. [12], teachers who function effectively in educational environments can substantially influence their students’ academic outcomes. That is, the higher the teacher effectiveness, the greater the students’ learning outcomes. In the same vein, Pishghadam et al. [13] also linked teacher success to students’ desired outcomes by referring to the impressive effect of teachers’ professional performance on students’ class attendance. As they noted, students normally have a strong belief in successful teachers, which inspires them to attend their classes regularly. Given that teacher professional success plays a pivotal role in promoting students’ outcomes [11,13], factors helping teachers to function effectively at work need to be identified. To respond to this need, a remarkable number of investigations have focused on the implications of personal variables for teachers’ professional success [14–24]. According to Pishghadam et al. [25], “students who attend class regularly have a much greater chance of making high grades than do students who skip lots of classes”. Yet, the consequences of professional variables have received scant research attention. Simply said, the role of profession-related factors in teachers’ professional success has been disregarded. To address this lacuna, the present research seeks to evaluate the function of two profession-related factors, namely job satisfaction and loving pedagogy, in Chinese EFL teachers’ professional success.

As a profession-related variable, job satisfaction pertains to a desirable emotional condition caused by an individual’s appraisal of his/her occupation and occupational experience [26,27]. Job satisfaction in the teaching career deals with the degree to which an individual teacher positively perceives the teaching career and its working conditions [28,29]. Building upon the key tenets of positive psychology (PP), MacIntyre et al. [30] articulated that job satisfaction as an important indicator of teacher wellbeing promotes their professional growth, flourishment, and success. In this regard, Huang et al. [31] also maintained that job satisfaction can enormously influence teachers’ professional performance. To them, teachers who are enthusiastic about their profession and satisfied with their working environment function more effectively in instructional-learning contexts. It is because being happy and content with the working conditions inspires teachers to stay and succeed in their profession [32,33].

Besides, loving pedagogy refers to “the care, sensitivity, and empathy that teachers have toward their students’ needs, learning experiences, and development” [34]. As Yin et al. [35] pinpointed, love is an indivisible part of education that can be represented through a respectful learning atmosphere, intimate and mutual relationships, and caring behaviors. While the notion of love may appear straightforward, it is a desirable feeling that can affect all facets of education, including teaching effectiveness [36–38]. According to Wang et al. [37], language teachers who educate their learners through love are more likely to succeed in the teaching profession. It is because loving pedagogy helps teachers to involve their students in learning activities [39,40]. Määttä et al. [41] also emphasized the value of love in education by stating that positive emotions like love, care, and empathy are of great help in promoting teachers’ professional success. To them, the love, care, and empathy teachers demonstrate while teaching enable them to efficiently influence learners’ academic outcomes.

Notwithstanding the significance of loving pedagogy and job satisfaction in teachers’ professional success [30,37,41,42], the role of these two profession-related factors in English language teachers’ success has not been widely studied [43,44]. Furthermore, no original study has assessed the function of these constructs at the same time. The current study seeks to minimize the gaps by evaluating the role of loving pedagogy and job satisfaction in predicting Chinese EFL teachers’ professional success.

Job satisfaction has been broadly defined by Evans [45] as “the state of mind determined by the extent to which the individual perceives his/her job-related needs being met”. This concept was further characterized by Schultz et al. [46] as an individual’s psychological and emotional disposition toward his or her career. With respect to these definitions, teachers’ job satisfaction pertains to their affective reactions to the teaching career and their professional role [47,48]. As Malinen et al. [49] pinpointed, job satisfaction is subjective to a variety of internal and external factors that are called “work content factors” and “work context factors”, respectively. They stated that one’s job satisfaction is determined by the inherent features of the profession (work content factors) and the workplace conditions (work context factors). Accordingly, besides the nature of the teaching profession, teachers’ job satisfaction may be influenced by some contextual factors, including class size, classroom facilities, and colleagues’ behaviors [50].

To date, some researchers have evaluated the role of job satisfaction in educational environments by investigating its potential effects on teacher commitment [51], teacher cooperation [52], teacher professional performance [53], and teacher success [43]. For example, Rezaee et al. [43] assessed the impact of job satisfaction on English teachers’ professional success. To do this, 440 English teachers were asked to answer two valid surveys. The assessment of teachers’ responses uncovered that job satisfaction can favorably affect teachers’ professional success. In a similar study, Olsen et al. [52] explored the role of job satisfaction in teacher cooperation. Put simply, they examined whether teachers’ job satisfaction is influential in their cooperation. To accomplish this, two pre-designed surveys were distributed among a sample of school teachers. The results showed that job satisfaction serves a positive, significant role in improving teacher cooperation. By the same token, Baluyos et al. [53] analyzed the role of job satisfaction in teachers’ professional performance at schools. In doing so, through stratified random sampling, 313 school teachers were selected to take part in data collection process. Then, two pre-designed surveys were distributed among respondents in order to collect their viewpoints. The data analysis indicated that job satisfaction can play an important role in improving teachers’ professional performance. Additionally, in a recent study, Bashir et al. [51] tested the role of job satisfaction in raising teachers’ organizational commitment. To this end, two valid surveys were given to 396 teachers. The analysis outcomes unraveled the significant function of job satisfaction in enhancing teachers’ organizational commitment.

The term “loving pedagogy” or “pedagogy of love” refers to “teachers’ empathy, care, value, and respect for students’ inner states, needs, feelings, and different personality types” [37]. To implement a loving pedagogy in instructional-learning environments, teachers need to be sensitive about their students’ needs, preferences, and interests [54]. Additionally, they are required to be proficient in employing interpersonal communication skills to offer a lovely learning atmosphere [55,56]. As put forward by Wilkinson et al. [57], loving pedagogy empowers teachers to decrease the amount of anxiety, stress, and apprehension among students. The absence of negative feelings like apprehension and stress allows students to do well in the learning environment [58–60].

Previous research into loving pedagogy revealed that educating students through love can bring about various favorable outcomes for both students [34,61] and teachers [62,63]. For instance, Zhao et al. [34] evaluated the implications of loving pedagogy for EFL learners’ academic engagement. The results demonstrated that loving pedagogy positively contributes to EFL learners’ engagement. In another inquiry, Barcelos [62] studied the role of loving pedagogy in teachers’ professional identity. Put it another way, he examined the extent to which loving pedagogy helps teachers develop their professional identity. The findings indicated that loving pedagogy was of great help in developing teachers’ professional identity. Likewise, Grimmer [63] assessed the impact of loving pedagogy on teachers’ professional performance. The outcomes revealed that a loving teacher may outperform in instructional-learning contexts.

The notion of professional success has to do with how efficiently an individual fulfills his or her professional tasks [64]. Accordingly, teacher professional success means how successfully teachers play their teaching role in educational contexts [65]. While its definition may appear simple, teacher professional success is a multifaceted construct that encompasses several dimensions [20,66,67]. For Coombe [67], teachers’ professional success is a complex construct with multiple facets like “professional knowledge”, “with-it-ness”, “instructional effectiveness”, “street smarts”, and “good communication skills”. She believes that a successful language teacher is one who possesses all the features. According to Coombe [67], professional knowledge as an important aspect of teachers’ success deals with their knowledge and information about the course content, curriculum, instructional techniques, and educational purposes. Another essential facet of teacher success is with-it-ness, which is concerned with teachers’ ability to manage the classroom atmosphere and involve pupils in learning activities. Instructional effectiveness as another key dimension has to do with “knowing the content area and being able to deliver effective lessons matters” [67]. Street smarts also refers to being aware of what is happening in classroom contexts. Finally, good communication skills pertain to teachers’ capability to effectively communicate with pupils, educational authorities, and colleagues.

Teacher professional success, without a shadow of a doubt, has an enormous impact on learners’ academic outcomes [68], classroom engagement [69], and their willingness to attend classes [25]. According to previous research, learners who view their teachers as successful tend to attend classes and participate in academic activities. Owing to the value of teachers’ professional success, factors supporting teachers to succeed in their profession need to be recognized. To address this necessity, many researchers have evaluated the role of personal qualities, including autonomy, self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, and creativity in teachers’ professional success [16,17,70–72]. Nevertheless, the role of professional variables like job satisfaction and loving pedagogy in teacher success has remained unclear. To minimize the gap, the present research intends to identify the role of job satisfaction and loving pedagogy in Chinese EFL teachers’ professional success. To accomplish this, the following questions were formulated:

I. Are there any correlations between Chinese EFL teachers’ job satisfaction, loving pedagogy, and their professional success?

II. How much variances in Chinese EFL teachers’ professional success and job satisfaction can be predicted by loving pedagogy?

A large sample of 1591 Chinese EFL teachers with different academic degrees (i.e., BA, MA, Ph.D.) was recruited using maximum variation sampling. Maximum variation sampling is a subset of purposeful sampling strategies that is beneficial for assessing range in large national or regional programs [73]. The sample was selected from five various provinces of China, namely Jiangsu (N = 1217), Henan (N = 231), Anhui (N = 94), Shandong (N = 31), and Shanghai (N = 18). It comprised 1378 females (87%) and 213 males (13%), varying in age from 27 to 55 years old. The participants have been teaching English in different educational settings, including elementary school, secondary school, high school, vocational high school, and colleges. Their teaching experience varied from 5 to 30 years old. In order to respect research ethics, all participants were assured that their personal information would be treated confidentially.

Teacher job satisfaction scale (TJSS)

The “Teacher Job Satisfaction Scale (TJSS)”, developed by Bolin [74], was used to assess Chinese EFL teachers’ satisfaction at work. The TJSS uses a 5-point Likert scale, varying in answers from 1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”. It is made up of five key components, including “self-fulfillment” (items 1–7), “work intensity” (items 8–12), “salary income” (items 13–17), “leadership relations” (items 18–22), and “collegial relations” (items 23–26). The TJSS includes but is not limited to the following items: item (7) “Being a teacher fulfills my ideal”, item (15) “I am satisfied with subsidies and service bonus”, and item (20) “School leaders care for me”. The TJSS’s reliability was measured to be 0.89 in this research. Using Cronbach Alpha coefficient, the researchers measured the reliability index of every component. The indexes of reliability for the components were 0.73, 0.71, 0.79, 0.81, & 0.85, respectively.

Dispositions towards loving pedagogy scale (DLPS)

Chinese EFL teachers’ dispositions towards loving pedagogy were evaluated using “Dispositions towards Loving Pedagogy Scale (DLPS)” [35]. The DLPS includes 29 items, rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 5 “Strongly agree” to 1 “Strongly disagree”. It is comprised of six different facets, including “acceptance of diversity and classroom community” (items 1–9), “intimacy” (items 10–15), “bonding and sacrifice” (items 16–22), “empathy” (items 23–25), “forgiveness” (items 26, 27), and “kindness” (items 28, 29). Some instances of DLPS’s items are as follows: item (9) “I make a point of engaging in kind acts towards my students in the context of my teaching every hour”, item (10) “It is OK for a student to hug me occasionally if they want”, and item (14) “I encourage students to ask for and provide forgiveness”. In this research, a reliability index of 0.95 was found for this scale. The reliability index for the six facets were 0.69, 0.70, 0.75, 0.68, 0.76, and 0.72, respectively.

Characteristics of successful language teachers questionnaire (CSLTQ)

To assess teachers’ effectiveness in Chinese EFL classes, “Characteristics of Successful Language Teachers Questionnaire (CSLTQ)” [75] was employed. The CSLTQ is a self-report scale with eight major factors, namely “familiarity with foreign language and culture”, “teaching accountability”, “teaching booster”, “learning booster”, “interpersonal relationships”, “physical and emotional acceptance”, “availability”, and “attention to all”. The CSLTQ encompasses 46 items to which teachers answer on a 5-point Likert scale. The reliability coefficient of CSLTQ for this research was 0.98. The reliability index for the eight factors were 0.73, 0.65, 0.74, 0.81, 0.90, 0.76, 0.84, and 0.89, respectively.

Using SEM analysis, the construct validity and reliability of the instruments were also evaluated. To do this, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were all considered [76]. Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability are used to assess reliability (CR). It is advised that values between 0.60 and 0.70 are suggestive of acceptable values in exploratory research; however, because CR is a less conservative statistic, values greater than 0.70 are required to demonstrate adequate internal reliability. The average variance retrieved is used to determine convergent validity (AVE). A value of 0.50 or greater for AVE is commonly used to support convergent validity. In contrast, discriminant validity is established by assessing the hetero-trait-mono-trait ratio (HTMT). The recommended cut-off value of 0.90 is utilized to demonstrate the latent variable’s discriminant validity.

To start the data gathering process, the consent form was virtually administered to 1800 Chinese EFL teachers. Among them, 1591 teachers agreed to take part in this research. Then, all the aforementioned scales (i.e., TJSS, DLPS, and CSLTQ) were sent to participants using WeChat application. To gather accurate and reliable answers, participants were told how to respond to the questionnaires.

First, using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, the normality of data distribution was tested. Then, to inspect the association between job satisfaction, loving pedagogy, and teacher professional success, the gathered responses were subjected to a series of correlational analyses. Moreover, through structural equation modeling (SEM), the power of job satisfaction and loving pedagogy in predicting Chinese EFL teachers’ professional success was assessed.

Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Shapiro-Wilk, and Spearman tests

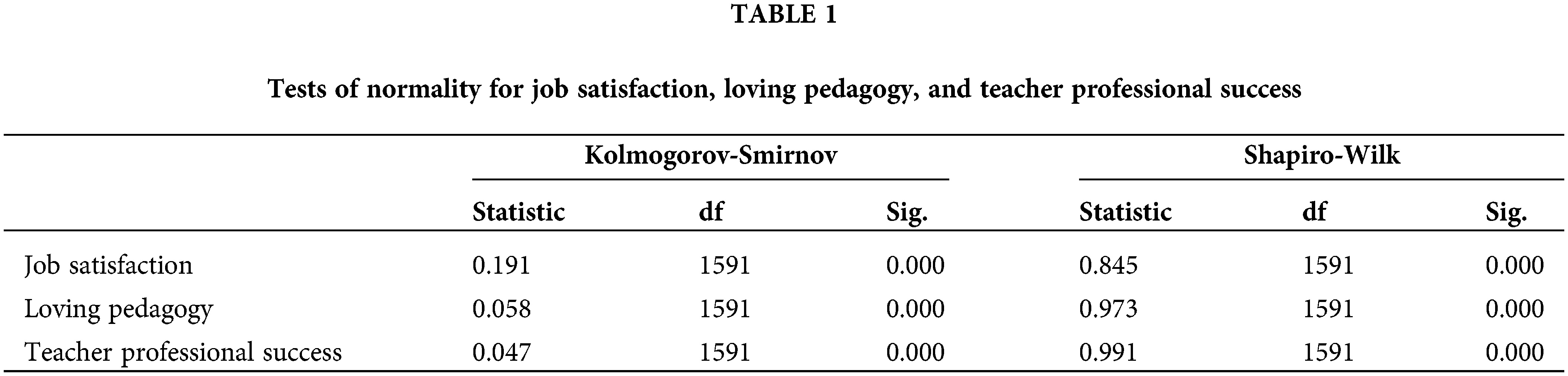

Initially, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were implemented to evaluate the normality of the collected data. The results of normality tests are demonstrated below (Table 1).

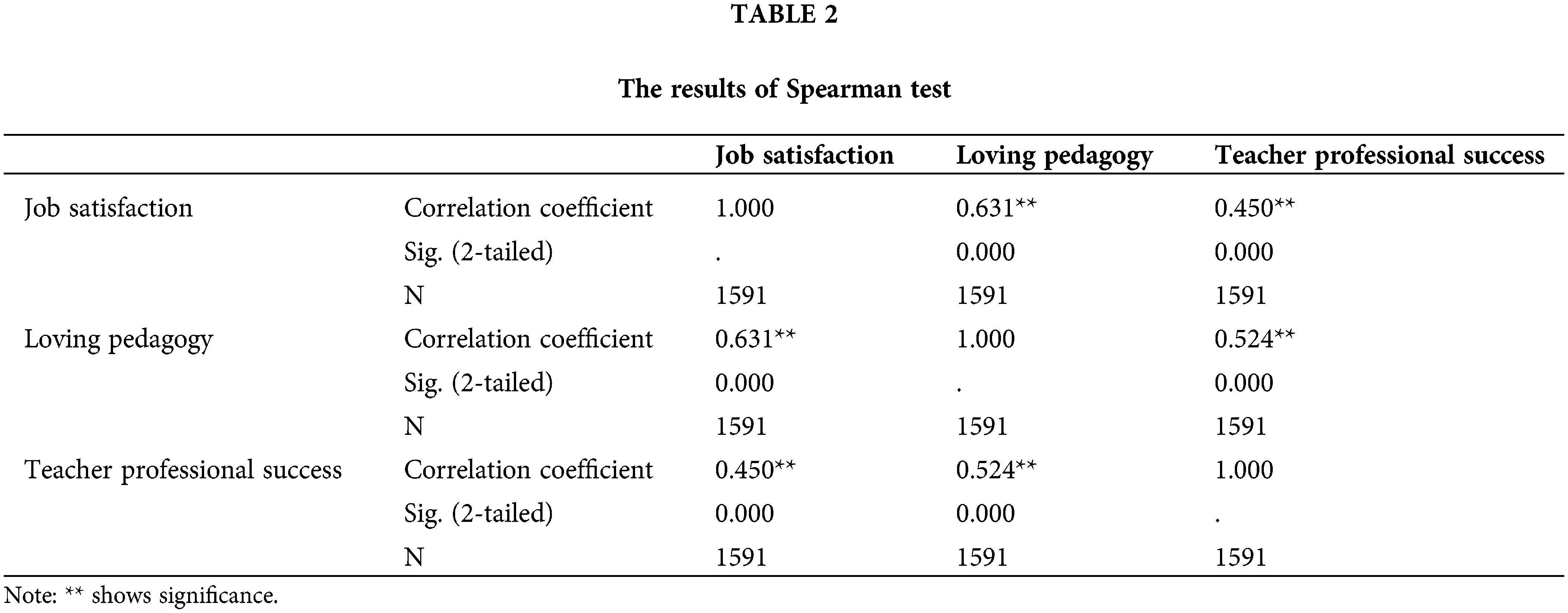

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests revealed that the gathered data was abnormal for all three variables (p = 0.000). Hence, Spearman Rho correlation as a nonparametric test was performed to measure the relationships between job satisfaction, loving pedagogy, and teacher professional success. The results of this nonparametric test are depicted in Table 2.

The Spearman Rho test uncovered a favorable, direct association between job satisfaction and teachers’ professional success (r = 0.450, n = 1591, p = 0.000, α = 0.01). Similarly, a remarkable and positive association was discovered between loving pedagogy and teachers’ professional success (r = 0.524, n = 1591, p = 0.000, α = 0.01). Likewise, job satisfaction was found to be closely related to loving pedagogy (r = 0.631, n = 1591, p = 0.000, α = 0.01).

Assessing the structural model

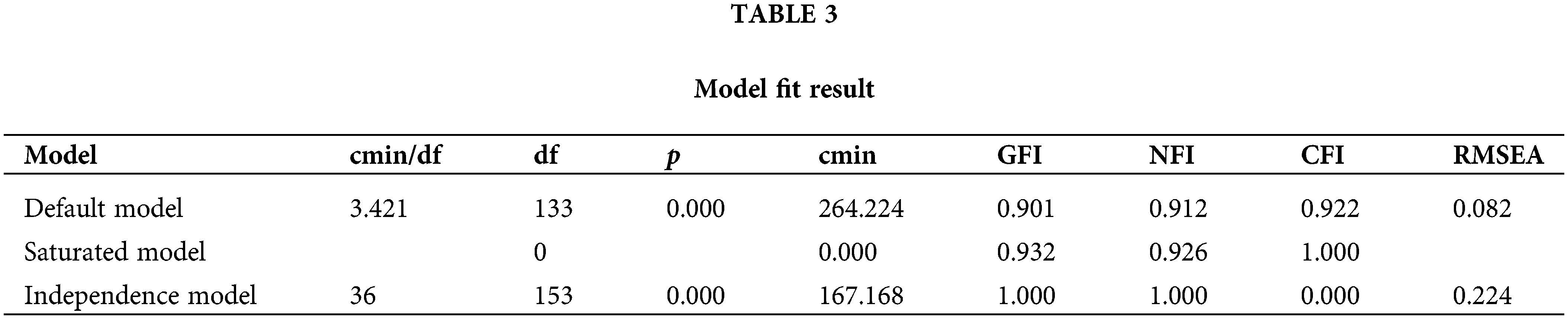

In Table 3, the result indicated that five determiners are ratio of cmin-df, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The model fit indices are all within specifications. Therefore, cmin/df is 3.421 (spec. ≤ 3.0), GFI = 0.901 (spec. > 0.9), NFI = 0.912 (spec. > 0.9), CFI = 0.922 (spec. > 0.9), and RMSEA = 0.0822 (spec. < 0.080).

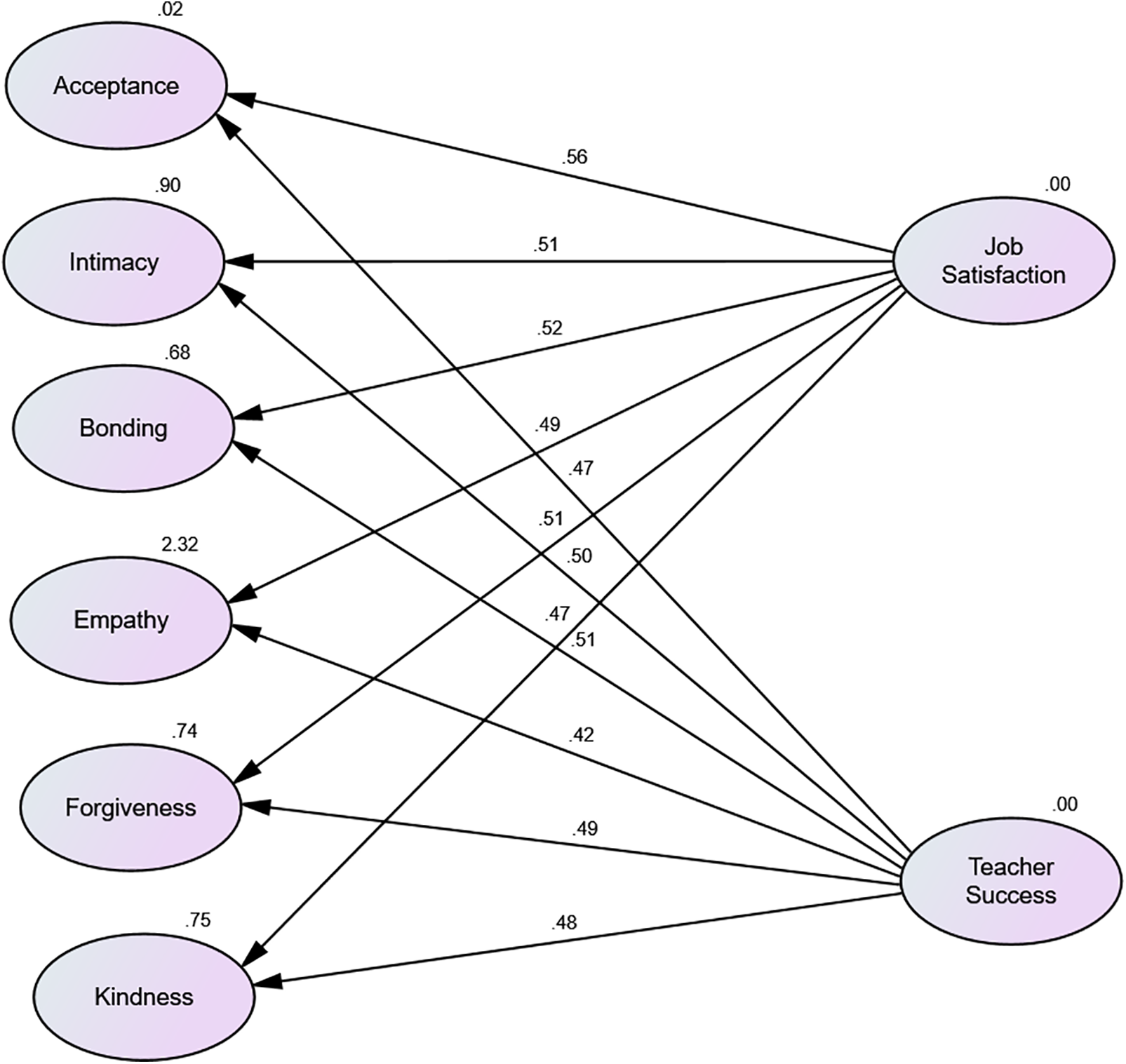

The structural model result in Fig. 1 shows the achieved stable model fit estimation. The indicators of fit: cmin/df = 3.421 (cmin = 3.421, df = 133); GFI = 0.901 (spec. > 0.9), NFI = 0.912 (spec. > 0.9), CFI = 0.922 (spec. > 0.9), and RMSEA = 0.082 (spec. < 0.080). In sum, Fig. 1 empirically shows that loving pedagogy has a highly significant influence on Chinese EFL teachers’ job satisfaction. This figure also shows that loving pedagogy has a highly significant influence on teachers’ professional success. These indices suggested that the structural model provided a good fit to the data at hand and yielded a corroborating value for the good model fit.

Figure 1: Standardized coefficients of the structural model. Note: All paths were significant but for the simplicity of the figure the standardized coefficient values among sub-component of loving pedagogy were omitted.

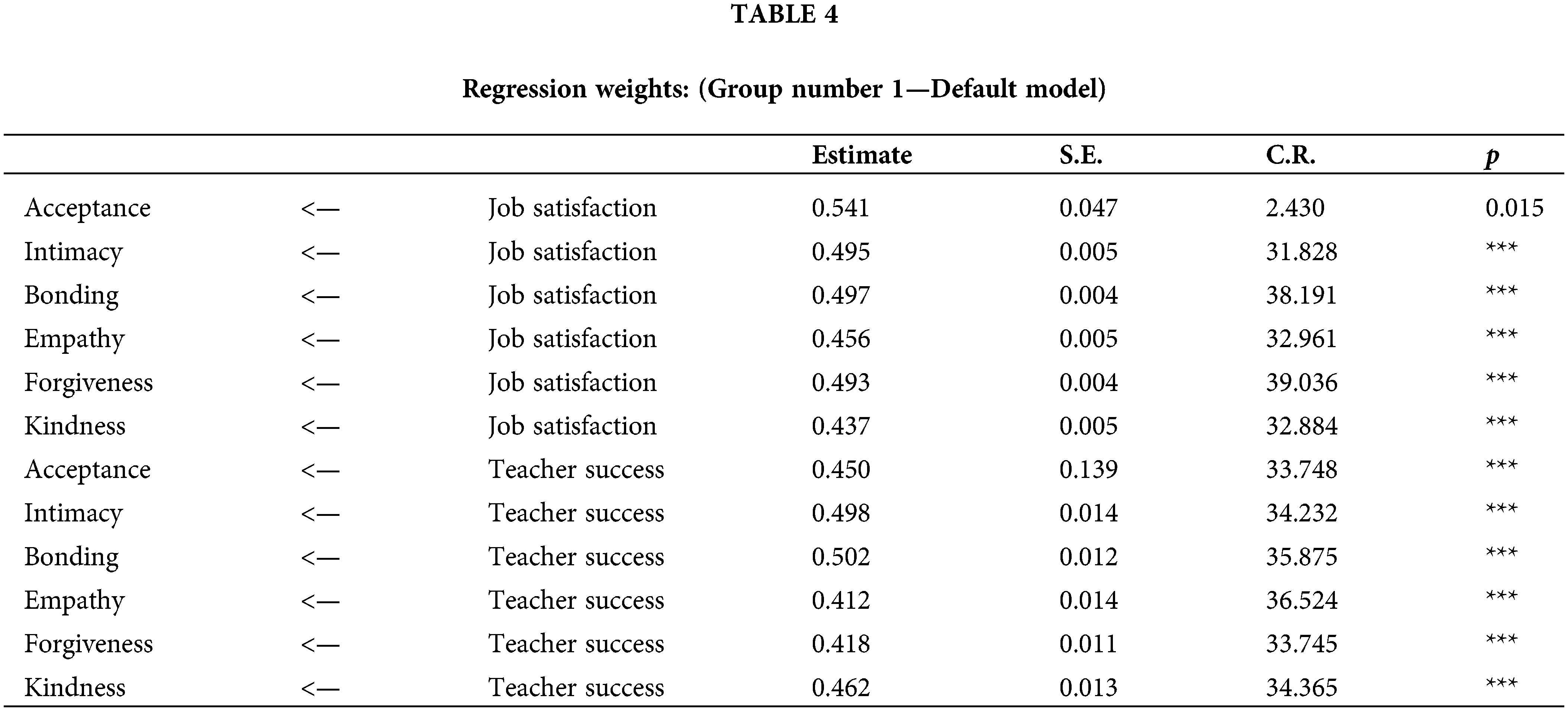

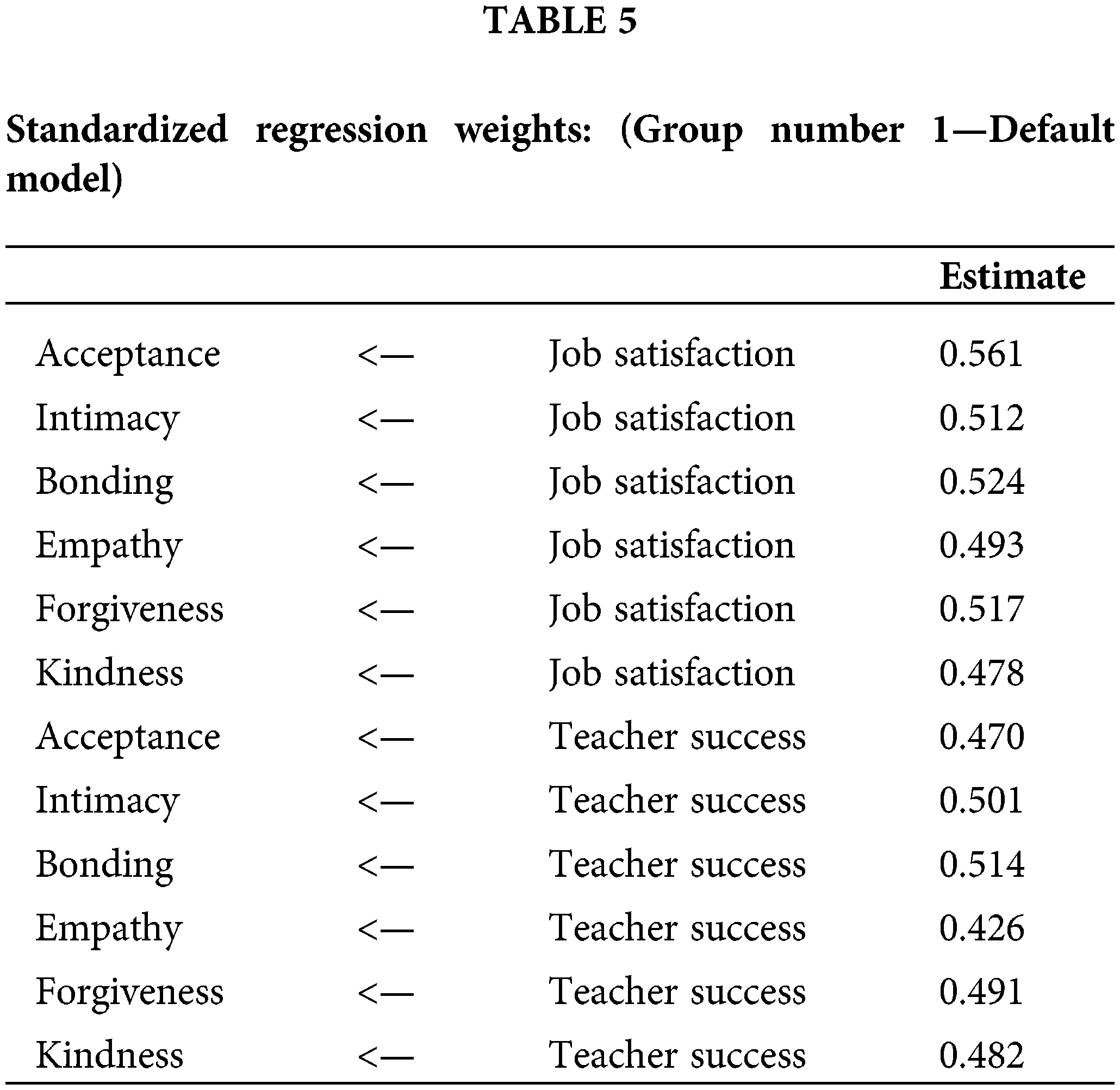

The results of Tables 4 and 5 represent that the null hypothesis is rejected. It means that loving pedagogy predicts teachers’ job satisfaction and professional success. The values indicate that 56 percent of changes in teachers’ job satisfaction can be predicted by their teachers’ acceptance; 51 percent of changes in teachers’ job satisfaction can be predicted by their teachers’ intimacy. Acceptance, intimacy, bonding, and forgiveness predict more than 50 percent of changes in teachers’ job satisfaction. In addition, intimacy and bonding predicted more than 50 percent of changes in teachers’ professional success.

The present research was an attempt to measure the associations between job satisfaction, loving pedagogy, and professional success. This inquiry also set out to probe the role of loving pedagogy in Chinese EFL teachers’ job satisfaction and professional success. Put differently, this inquiry aimed to determine whether loving pedagogy help Chinese EFL teachers job satisfaction and succeed in their profession.

As to the first purpose of this research, the correlational analyses illuminated a strong, positive relationship, first, between job satisfaction and professional success, and second, between loving pedagogy and professional success. Furthermore, a close connection was discovered between job satisfaction and loving pedagogy. The outcome of this research concerning the strong relationship between job satisfaction and professional success is in line with that of Rezaee et al. [43], who reported a close, direct link between job satisfaction and Iranian teachers’ success. This result also supports Baluyos et al.’s [53] outcomes, which indicated that job satisfaction is tied to teachers’ occupational success. Besides, the result of this investigation regarding the favorable link between loving pedagogy and professional success corroborates the findings of Grimmer [63], who found a remarkable association between loving pedagogy and teachers’ perceived success.

As to the second goal of the current research, the regression analysis uncovered that loving pedagogy can desirably predict Chinese EFL teachers’ job satisfaction and professional success. The positive role of job satisfaction in Chinese EFL teachers’ professional success accords with the core tenets of positive psychology. According to positive psychology, being happy and satisfied with working conditions encourages teachers to give their all to their career, which results in their professional success [30]. That is, the higher the job satisfaction, the greater the likelihood of teachers’ professional success. This result also matches the idea of Huang et al. [31], who asserted that job satisfaction as a stimulating factor inspires teachers to function more effectively in educational settings. Furthermore, the pivotal role of loving pedagogy in the professional success of Chinese EFL teachers may be because instructors who educate learners through love are able to draw their attention [34], which is critical for their professional success. This result lends support to Wang et al.’s [37] assertion regarding the importance of loving pedagogy in language education contexts. To them, teachers can effectively fulfill their learners’ academic needs and expectations using a loving pedagogy. This outcome further supports what Wilkinson et al. [57] have maintained concerning the value of loving pedagogy. They stated that implementing loving pedagogy in classroom contexts enables teachers to outperform at work. It is because incorporating love, empathy, and care into education keeps teachers and students away from anxiety, apprehension, boredom, and stress [59]. It is worth mentioning that the aforementioned feelings, namely anxiety, apprehension, boredom, and stress, endanger teachers’ professional success [60].

The findings of the SEM analysis indicated the all the six components of loving pedagogy significantly accounted for L2 teachers’ job satisfaction and success. This means that the contribution of the construct of loving pedagogy to these two outcomes should be reflected and discussed in terms of these components. First off, acceptance of diversity is the main component explaining much of the variance of teacher success and job satisfaction. Given the heterogenous nature of a classroom community, it is postulated that teachers in their practice of affective pedagogy welcome this heterogeneity. This is quite consistent with the concept of dramatic friendship embedded in affective pedagogy, in which teachers are supposed to sympathize with all the learners in the community of the classroom. More specifically, when it comes to an L2 classroom, regardless of the possible differences in learners’ proficiency level, individual differences are prevalent in the class in terms of mood, personality, motivation, emotion, and willingness to communicate, to name but a few. Any negligence of these differences on the part of language teachers might lead to divergent attitudes and a lack of mutual teacher-student interest where their expectations can hardly be shared. Consequently, a sense of delight reflecting the emergence of dramatic friendship in the class might not appear and; thus, the teachers’ professional success might be jeopardized.

Second, the empathy and the intimacy sides of loving pedagogy can strengthen the faithfulness learners need to build trust with their language teachers in the environment of the classroom. Therefore, it is not surprising to see teachers’ success and satisfaction to be guaranteed by language teachers’ sense of empathy and intimacy. Besides, this sense of empathy enables language teachers to raise their learners’ sense of selflessness via emotional scaffolding. Moreover, kindness and forgiveness are what the satisfaction of teaching profession in the L2 domain highly depends on. The process of language learning is replete with many situations of making mistakes and corrective feedback. For instance, having made a grammatical mistake, a language learner might feel embarrassed or unwilling to communicate in the L2. Teacher’s kindness and forgiveness are the qualities which builds the dramatic bond leaners need to continue their process of learning with more desire and willingness, which denotes how the affective pedagogy of language teachers can set the stage for their learners’ psychological needs of language learning. Finally, as one of the most altruistic sides of loving pedagogy, bonding and sacrifice contributes to language teachers’ satisfaction and professional success. It seems that all the other components of loving pedagogy direct this quality of affective pedagogy into its climax in which language teachers devote themselves wholeheartedly to their learners. This devotion, as the findings indicated, has a bidirectional relationship with language teachers’ job satisfaction and professional success. This means that when almost all the learning needs of language learners are met out the bonding and sacrifice of their teachers, their teachers regard themselves highly successful and satisfied.

The results of this investigation are subject to several limitations. The first limitation lies in the fact that the current research was conducted in China as an EFL country. Given that the outcomes of this inquiry might not be applicable to “English as a second language (ESL)” countries, researchers are advised to perform a similar investigation in an ESL country. Another limitation of this research that could have influenced the accuracy of the findings was that only close-ended scales were utilized to collect the needed data. To increase the accuracy of findings, future research studies need to employ some other data-gathering instruments like open-ended scales, structured interviews, semi-structured interviews, and observation checklists. The third limitation of this research was the ignorance of contextual factors. Thus, it would be interesting to evaluate the mediating role of contextual factors like teaching experience and academic major in the associations between job satisfaction, loving pedagogy, and teacher professional success. As for the fourth limitation of this inquiry, the imbalanced distribution of participants in terms of gender and regions might also be tackled in the future researches. Additionally, regarding the design of the study, a pure quantitative method was employed to delve into the role of loving pedagogy and job satisfaction in teachers’ professional success. The following investigations are advised to study the function of these constructs using a qualitative method. Finally, given that job satisfaction is a dynamic construct that may vary over time, longitudinal studies identifying any probable changes in teachers’ job satisfaction levels are highly recommended.

This investigation was performed to assess the associations between job satisfaction, loving pedagogy, and teacher professional success, as well as the function of loving pedagogy in Chinese EFL teachers’ job satisfaction and professional success. The data analysis indicated that loving pedagogy are closely related to teacher job satisfaction and professional success. The results also revealed that loving pedagogy can noticeably predict Chinese EFL teachers’ job satisfaction and professional success. Taken together, loving pedagogy as a profession-related factor was found to be of great help in improving teachers’ effectiveness in Chinese EFL classes. This investigation has gone some way towards enhancing teachers’ understanding of the value of love in educational environments. Regarding the importance of loving pedagogy in professional success, EFL teachers need to educate their learners through love to become successful in their profession. As the definition of loving pedagogy suggests [37], teachers are required to care about students’ preferences, respect their opinions, and fulfill their academic needs. Furthermore, as collegial relations can promote teachers’ job satisfaction [73], teachers need to establish close, intimate relationships with their colleagues. Additionally, this research has some valuable implications for educational managers as well. Given that professional success is of high importance for teachers’ mental health [77,78] and well-being [79,80], educational managers are advised to help teachers improve their professional success. As the results of the current paper revealed, teachers’ professional success largely depends on their job satisfaction. Thus, to promote teachers’ professional success, educational managers should increase their job satisfaction. To do this, they are required to use a transformational leadership style while interacting with their teachers [81]. They also need to provide teachers with a pleasant working environment by equipping them with efficient instructional aids [81]. Finally, as the research on loving pedagogy in L2 affective domain in its fledgling state, it needs further exploration so that its nomological and contributing factors can be identified. Thus, both nomothetic and idiographic approaches can contribute to deeper understanding of the construct [82]. The nomothetic approach can be used to expand the nomological network of the construct in terms of its association with other related constructs. On the other hand, the idiographic approach enables researchers to explore the dynamics of the construct in a given situated context.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful for the insightful comments suggested by the editor and the anonymous reviewers.

Funding Statement: This study was sponsored by the Research Project of Jiangsu Social Science Fund Project, entitled “Research on Irrational Expression of Crisis Discourse” (Grant No. 21YYD001), and Basic Foreign Language Education Research Project of Changshu Institute of Technology, entitled “A Study on the Regulation Mechanism of Professional Happiness of Foreign Language Teachers in Primary and Secondary Schools from the Perspective of Positive Psychology” (Grant No. 2022cslgwgy008).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: XW; data collection: YL; analysis and interpretation of results: XW; draft manuscript preparation: XW and YL. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Approval: The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Academic and Ethics Committee of Changshu Institute of Technology (Ethical approval number: CIT-AE 2022032103). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Nussbaum MC. Upheavals of thought: the intelligence of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

2. Oakeshott M. On human conduct. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

3. Fan J, Wang Y. English as a foreign language teachers’ professional success in the Chinese context: the effects of well-being and emotion regulation. Front Psychol. 2022;13:259. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.952503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Moskowitz S, Dewaele JM. Is teacher happiness contagious? A study of the link between perceptions of language teacher happiness and student attitudes. Innov Lang Learn Teach. 2021;15(2):117–30. doi:10.1080/17501229.2019.1707205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Talebzadeh N, Elahi SM, Khajavy GH. Dynamics and mechanisms of foreign language enjoyment contagion. Innov Lang Learn Teach. 2020;14(5):399–420. doi:10.1080/17501229.2019.1614184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Coombe C. Quality education begins with teachers: what are the qualities that make a TESOL teacher great? In: Agudo JDM, editor. Quality in TESOL and teacher education. Abingdon: Routledge; 2019. p. 173–84. [Google Scholar]

7. Hung CM, Oi AK, Chee PK, Man CL. Defining the meaning of teacher success in Hong Kong. In: Handbook of teacher education. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007. p. 415–32. [Google Scholar]

8. Nayernia A, Taghizadeh M, Farsani MA. EFL teachers’ credibility, nonverbal immediacy, and perceived success: a structural equation modelling approach. Cogent Educ. 2020;7(1):1774099. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2020.1774099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Derakhshan A, Coombe C, Zhaleh K, Tabatabaeian M. Examining the roles of continuing professional development needs and views of research in English language teachers’ success. TESL-EJ. 2020;24(3). http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume24/ej95/ej95a2/. [Google Scholar]

10. Zhao J, Joshi R, Dixon LQ, Huang L. Chinese EFL teachers’ knowledge of basic language constructs and their self-perceived teaching abilities. Ann Dyslexia. 2016;66(1):127–46. doi:10.1007/s11881-015-0110-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wossenie G. EFL teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, pedagogical success and students’ English achievement: a study on public preparatory schools in Bahir Dar Town, Ethiopia. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2014;3(2):221–8. doi:10.4314/star.v3i2.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Y, Derakhshan A. Enhancing Chinese and Iranian EFL students’ willingness to attend classes: the role of teacher confirmation and caring. Porta Linguarum. 2023;39(1):165–92. doi:10.30827/portalin.vi39.23625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Pishghadam R, Derakhshan A, Zhaleh K, Al-Obaydi LH. Students’ willingness to attend EFL classes with respect to teachers’ credibility, stroke, and success: a cross-cultural study of Iranian and Iraqi students’ perceptions. Curr Psychol. 2021;42:1–15. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01738-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bardach L, Klassen RM, Perry NE. Teachers’ psychological characteristics: do they matter for teacher effectiveness, teachers’ well-being, retention, and interpersonal relations? An integrative review. Educ Psychol Rev. 2022;34(1):259–300. doi:10.1007/s10648-021-09614-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bing H, Sadjadi B, Afzali M, Fathi J. Self-efficacy and emotion regulation as predictors of teacher burnout among English as a foreign language teachers: a structural equation modeling approach. Front Psychol. 2022;13:522. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.900417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Chen J. Efficacious and positive teachers achieve more: examining the relationship between teacher efficacy, emotions, and their practicum performance. Asia-Pac Educ Res. 2019;28(4):327–37. doi:10.1007/s40299-018-0427-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Derakhshan A, Coombe C, Arabmofrad A, Taghizadeh M. Investigating the effects of English language teachers’ professional identity and autonomy in their success. Issues Lang Teach. 2020;9(1):1–28. doi:10.22054/ILT.2020.52263.496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Greenier V, Derakhshan A, Fathi J. Emotion regulation and psychological well-being in teacher work engagement: a case of British and Iranian English language teachers. System. 2021;97(2):102446. doi:10.1016/j.system.2020.102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Klassen RM, Tze VM. Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: a meta-analysis. Educ Res Rev. 2014;12(4):59–76. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pishghadam R, Derakhshan A, Jajarmi H, Tabatabaee S, Shayesteh S. Examining the role of teachers’ stroking behaviors in EFL learners’ active/passive motivation and teacher success. Front Psychol. 2021;12:25. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.707314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Reeves TD, Hamilton V, Onder Y. Which teacher induction practices work? Linking forms of induction to teacher practices, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction. Teach Teach Educ. 2022;109(3):103546. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wu Y, Lian K, Hong P, Liu S, Lin RM, Lian R. Teachers’ emotional intelligence and self-efficacy: mediating role of teaching performance. Soc Behav Pers. 2019;47(3):1–10. doi:10.2224/sbp.8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xia J, Wang M, Zhang S. School culture and teacher job satisfaction in early childhood education in China: the mediating role of teaching autonomy. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2022;24:101–11. doi:10.1007/s12564-021-09734-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sun X, Fathi J, Shirbagi N, Mohammaddokht F. A structural model of teacher self-efficacy, emotion regulation, and psychological well-being among English teachers. Front Psychol. 2022;13:904151. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.904151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Pishghadam R, Derakhshan A, Zhaleh K. The interplay of teacher success, credibility, and stroke with respect to EFL students’ willingness to attend classes. Pol Psychol Bull. 2019;50(4):284–92. doi:10.24425/ppb.2019.131001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liao SS, Hu DC, Chung YC, Chen LW. LMX and employee satisfaction: mediating effect of psychological capital. Leadership Org Dev J. 2017;38(3):433–49. doi:10.1108/LODJ-12-2015-0275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhu Y. A review of job satisfaction. Asian Soc Sci. 2013;9(1):293–98. doi:10.5539/ass.v9n1p293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li M, Wang Z. Emotional labour strategies as mediators of the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction in Chinese teachers. Int J Psychol. 2016;51(3):177–84. doi:10.1002/ijop.12114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S. Job satisfaction, stress and coping strategies in the teaching profession—What do teachers say? Int Educ Stud. 2015;8(3):181–92. doi:10.5539/ies.v8n3p181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. MacIntyre PD, Gregersen T, Mercer S. Positive psychology in SLA. Bristol: Multilingual Matters; 2016. doi:10.21832/9781783095360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Huang S, Huang Y, Chang W, Chang L, Kao P. Exploring the effects of teacher job satisfaction on teaching effectiveness. Int J Mod Educ Forum. 2013;2(1):17–30. [Google Scholar]

32. Casely-Hayford J, Björklund C, Bergström G, Lindqvist P, Kwak L. What makes teachers stay? A cross-sectional exploration of the individual and contextual factors associated with teacher retention in Sweden. Teach Teach Educ. 2022;113:103664. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2022.103664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang F. Towards the impact of job satisfaction and collective efficacy on EFL teachers’ professional commitment. Front Psychol. 2022;13:82. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.938125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zhao S, Li M. Reflection on loving pedagogy and students’ engagement in EFL/ESL classrooms. Front Psychol. 2021;12:757697. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.757697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yin LC, Loreman T, Abd Majid R, Alias A. The dispositions towards loving pedagogy (DTLP) scale: instrument development and demographic analysis. Teach Teach Educ. 2019;86(2):102884. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Clingan J. A pedagogy of love. J Sustain Educ. 2015;9(2):2151–7452. [Google Scholar]

37. Wang Y, Derakhshan A, Pan Z. Positioning an agenda on a loving pedagogy in SLA: conceptualization, practice, and research. Front Psychol. 2022;13:894190. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.894190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wang Y, Derakhshan A, Zhang LJ. Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: the past, current status and future directions. Front Psychol. 2021;12:731721. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Cousins SB. Practitioners’ constructions of love in early childhood education and care. Int J Early Years Educ. 2017;25(1):16–29. doi:10.1080/09669760.2016.1263939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Liu F. The role of EFL teachers’ praise and love in preventing students’ hopelessness. Front Psychol. 2021;12:597. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Määttä K, Uusiautti S. Pedagogical love and good teacherhood. In: Many faces of love. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers; 2013. p. 93–101. [Google Scholar]

42. Derakhshan A, Greenier V, Fathi J. Exploring the interplay between a loving pedagogy, creativity, and work engagement among EFL/ESL teachers: A multinational study. Curr Psychol. 2022;1–20. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03371-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Rezaee A, Khoshsima H, Zare-Bahtash E, Sarani A. A mixed method study of the relationship between EFL teachers’ job satisfaction and job performance in Iran. Int J Instr. 2018;11(4):577–92. [Google Scholar]

44. Wolomasi AK, Asaloei SI, Werang BR. Job satisfaction and performance of elementary school teachers. Int J Eval Res Educ. 2019;8(4):575–80. doi:10.11591/ijere.v8i4.20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Evans L. Professionals: re-examining the leadership dimension delving deeper into morale, job satisfaction and motivation among education. Educ Manag Adm Lead. 2001;29(1):291–306. doi:10.1177/0263211X010293004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Schultz DP, Schultz SE. Psychology and work today. New York, NY: Prentice Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

47. Jiang Y, Li P, Wang J, Li H. Relationships between kindergarten teachers’ empowerment, job satisfaction, and organizational climate: a Chinese model. J Res Child Educ. 2019;33(2):257–70. doi:10.1080/02568543.2019.1577773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S. Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teach Teach Educ. 2011;27(1):1029–38. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Malinen OP, Savolainen H. The effect of perceived school climate and teacher efficacy in behavior management on job satisfaction and burnout: a longitudinal study. Teach Teach Educ. 2016;60(1):144–52. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Lopes J, Oliveira C. Teacher and school determinants of teacher job satisfaction: a multilevel analysis. Sch Eff Sch Improv. 2020;31(4):641–59. doi:10.1080/09243453.2020.1764593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Bashir B, Gani A. Testing the effects of job satisfaction on organizational commitment. J Manag Dev. 2020;39(4):525–42. doi:10.1108/JMD-07-2018-0210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Olsen AA, Huang FL. Teacher job satisfaction by principal support and teacher cooperation: results from the schools and staffing survey. Educ Policy Anal Arch. 2019;27(11):n11. doi:10.14507/epaa.27.4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Baluyos GR, Rivera HL, Baluyos EL. Teachers’ job satisfaction and work performance. Open J Soc Sci. 2019;7(8):206–22. doi:10.4236/jss.2019.78015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Loreman T. Love as pedagogy. Rotterdam, Netherland: Sense; 2011. [Google Scholar]

55. Derakhshan A. Positive psychology in second and foreign language education. ELT J. 2022;76(2):304–6. doi:10.1093/elt/ccac002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Xie F, Derakhshan A. A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context. Front Psychol. 2021;12:1–10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Wilkinson J, Kaukko M. Educational leading as pedagogical love: the case for refugee education. Int J Leadersh Educ. 2020;23(1):70–85. doi:10.1080/13603124.2019.1629492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Cakici D. The correlation among EFL learners’ test anxiety, foreign language anxiety, and language achievement. Engl Lang Teach. 2016;9(8):190–203. doi:10.5539/elt.v9n8p190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Dewaele JM, MacIntyre PD. Foreign language enjoyment and foreign language classroom anxiety: the right and left feet of the language learner. In: MacIntyre PD, Gregersen T, Mercer S, editors. Positive psychology in SLA. Bristol: Multilingual Matters; 2016. p. 215–36. doi:10.21832/9781783095360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Jin Y, Dewaele JM, MacIntyre PD. Reducing anxiety in the foreign language classroom: a positive psychology approach. System. 2021;101(1):102604. doi:10.1016/j.system.2021.102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Liu Y, Li X, Chen L, Qu Z. Perceived positive teacher-student relationship as a protective factor for Chinese left-behind children’s emotional and behavioural adjustment. Int J Psychol. 2015;50(5):354–62. doi:10.1002/ijop.12112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Barcelos AMF. Revolutionary love and peace in the construction of an English teacher’s professional identity. In: Oxford R, Olivero M, Harrison M, Gregersen T, editors. Peacebuilding in language education. Bristol: Multilingual Matters; 2020. p. 96–109. doi:10.21832/9781788929806-011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Grimmer T. Developing a loving pedagogy in the early years: how love fits with professional practice. London: Routledge; 2021. [Google Scholar]

64. Furnham A, Hyde G, Trickey G. The values of work success. Pers Indiv Differ. 2013;55(5):485–9. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Tajeddin Z, Alemi M. Effective language teachers as persons: exploring pre-service and in-service teachers’ beliefs. TESL-EJ. 2019;22(4):n4. [Google Scholar]

66. Bremner N. What makes an effective English language teacher? The life histories of 13 Mexican university students. Engl Lang Teach. 2020;13(1):163–79. doi:10.5539/elt.v13n1p163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Coombe C. 10 characteristics of highly effective EF/SL teachers. Soci Pakistan Engl Lang Teach: Quarterly J. 2014;28(4):2–11. http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:jamk-issn-2343-0281-14. [Google Scholar]

68. Gershenson S. Linking teacher quality, student attendance, and student achievement. Educ Financ Policy. 2016;11(2):125–49. doi:10.1162/EDFP_a_00180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Franklin H, Harrington I. A review into effective classroom management and strategies for student engagement: teacher and student roles in today’s classrooms. J Educ Train Stud. 2019;7(12):1–12. doi:10.11114/jets.v7i12.4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Martin LE, Mulvihill TM. Voices in education: teacher self-efficacy in education. Teach Educ. 2019;54(3):195–205. doi:10.1080/08878730.2019.1615030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Pishghadam R, Nejad TG, Shayesteh S. Creativity and its relationship with teacher success. Braz Engl Lang Teach J. 2012;3(2):204–16. [Google Scholar]

72. Sezgin F, Erdogan O. Academic optimism, hope and zest for work as predictors of teacher self-efficacy and perceived success. Educ Sci: Theory Pract. 2015;15(1):7–19. doi:10.12738/estp.2015.1.2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Ary D, Jacobs LC, Irvine CKS. Introduction to research in education. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2018. [Google Scholar]

74. Bolin F. A study of teacher job satisfaction and factors that influence it. Chin Educ Soc. 2007;40(5):47–64. doi:10.2753/CED1061-1932400506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Sadeghi K, Babai H. Becoming an effective EFL teacher: living up to the expectations of L2 learners and teachers of English. Saarbrücken, Germany: VDM Verlag; 2009. [Google Scholar]

76. Hair J, Risher J, Sarstedt M, Ringle C. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev. 2019;31(1):2–24. doi:10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Glazzard J, Rose A. The impact of teacher well-being and mental health on pupil progress in primary schools. J Public Ment Health. 2020;19(4):349–57. doi:10.1108/JPMH-02-2019-0023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Shoshani A, Steinmetz S. Positive psychology at school: a school-based intervention to promote adolescents’ mental health and well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2014;15:1289–311. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9476-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Jennings PA. Early childhood teachers’ well-being, mindfulness, and self-compassion in relation to classroom quality and attitudes towards challenging students. Mindfulness. 2015;6(4):732–43. doi:10.1007/s12671-014-0312-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Rae T, Cowell N, Field L. Supporting teachers’ well-being in the context of schools for children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. Emot Behav Diffic. 2017;22(3):200–18. doi:10.1080/13632752.2017.1331969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Sudibjo N, Manihuruk AM. How do happiness at work and perceived organizational support affect teachers’ mental health through job satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic? Psychol Rese Behav Manag. 2022;15:939–51. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S361881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Derakhshan A, Wang YL, Wang YX, Ortega-Martín JL. Towards innovative research approaches to investigating the role of emotional variables in promoting language teachers’ and learners’ mental health. Int J Ment Health Pr. 2023;25(7):823–32. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools