Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Relationship between Father-Love Absence and Loneliness: Based on the Perspective of the Social Functionalist Theory and the Social Needs Theory

1 Moral Culture Research Center of Hunan Normal University, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410081, China

2 Research Center for Mental Health Education of Hunan Province, Changsha, 410081, China

3 Beijing Huijia Private School, Beijing, 102200, China

4 Tao Xingzhi Research Institute, Nanjing Xiao Zhuang University, Nanjing, 211171, China

5 Cognition and Human Behavior Key Laboratory of Hunan Province, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410081, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaojun Li. Email: ; Yanhui Xiang. Email:

# Yaping Zhou and He Zhong contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Psychological Therapy in Education Contexts: Focusing on Teachers’ and Students’ Mental Health based on Cognitive, Emotional, Social, and Behavioral Factors)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(2), 139-148. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.046598

Received 08 October 2023; Accepted 25 December 2023; Issue published 08 March 2024

Abstract

Fathers play an important role in adolescents’ development, which is significant for their development and influences their mental health, including feeling of loneliness. However, the effects and mechanisms of father-love absence on individual loneliness are not clear. Based on the social functionalist theory and the social needs theory, this study examines the influence of individual father-love absence on loneliness and its underlying mechanisms. A questionnaire survey was administered to 319 junior high school students and 1,476 high school students. The results showed that adolescents with father-love absence had higher levels of loneliness, and that father-love absence affected loneliness levels through mediating pathways of individual gratitude, peer relationships, and gratitude to peer relationships. This study not only confirms the negative effects of father-love absence on adolescents’ loneliness, but also explains the mediate roles of individual gratitude and peer relationships. It enriches the theoretical system related to family education and has important theoretical and practical implications for further interventions on adolescents’ mental health from the perspective of fatherless parenting.Keywords

Following traditional family role divisions, mothers are primarily responsible for Child-rearing and caregiving [1]. Given the fact that the widespread phenomenon of father-love absence in numerous families, which identifies as the father in the family may not be physically absent but is emotionally absent [2]. Father-love absence is defined as the absence of cognitive, emotional, volitional, and behavioral aspects that influences between the father and the individual during childhood [3]. In contrast to prior research about father absence, the concept of father-love absence in the current study is primarily focused on the father’s psychological absence during an individual’s childhood. Unlike father absence, father-love absence is potential, and can significantly influence an individual’s mental health [4]. Because father-love absence means that adolescents psychologically grow up in an incomplete family structure, experience a disharmonious family atmosphere, and believe that they do not obtain complete love from parents. It can predispose them to feelings of loneliness [5]. Consequently, father-love absence may be an important factor influencing an individual’s loneliness. However, as of the present, the influence of father-love absence on adolescent loneliness and the underlying mechanisms involved remain unclear. Hence, in the current study we address this gap using the social functionalist theory and the social needs theory to explore the association between father-love absence and loneliness, with gratitude and peer relationships serving as mediators. Providing a relevant foundation for mitigating loneliness among adolescents experiencing father-love absence.

The relationship between father-love absence and loneliness

Loneliness refers to an individual’s subjective sense of isolation resulting from unmet interpersonal relationship needs, whether in terms of quality or quantity [6]. Loneliness has various adverse effects on individuals, including accelerated aging [7,8] and increased mortality [9] in terms of physical health. It also has predictive negative effects on mental health, such as personality disorders [10] and mental disorders [11]. A recent report on global adolescent, loneliness reveals a significant surge among adolescents worldwide since 2010, rendering it a severe global concern [12]. Consequently, it is crucial to investigate the origins of loneliness. Many factors contributing to loneliness can be traced back to early life environments [13]. Father’s love, as important interactions in an individual’s early environment, plays a crucial role because father-love absence can result in the deficiency of essential emotional bonds between father and children. Moreover, it may impede the establishment of intimate relationships, hinder the development of fundamental trust. Thus, it is hard for individual to develop the comprehension of intricate emotions, perceptions, and social behaviors as individuals mature. Consequently, individuals experiencing father-love absence have a higher propensity to experience loneliness [14,15].

The association between father-love absence and loneliness is also supported by the social needs theory. The social needs theory is an important theory focusing on the mechanisms of loneliness generation, regarding that loneliness can emerge when adolescents are dissatisfied with their social needs or experience a lack of interpersonal relationships [16]. It is essentially a subjective experience of one’s own social circumstances [17]. Weiss found that individuals possess six inherent social needs, including the needs for attachment, social integration, and nurturing [18]. These needs can only be satisfied within particular social relationship contexts, and the absence of such needs’ fulfillment or the absence of specific social relationships can lead to the emergence of loneliness among the individual. In the early environment of an individual, the father, being a significant relationship [19], plays a crucial role in individual’s growth. Father-love absence results in the individual’s inability to meet attachment and nurturing needs, leading to the development and increase of loneliness. As a result, this study proposes H1: father-love absence positively predicts adolescents’ loneliness.

The mediating role of gratitude

Gratitude, as an emotion or personality trait, recognizes good deeds and affective experience of appreciation and pleasure that develops when an individual is favored [20]. It includes a complex array of subjective feelings, including curiosity, appreciation, and appreciation of life [21]. As a positive emotion trait, gratitude directs an individual’s attention towards the positive and valuable attributes of others, resulting in a more favorable memory bias [22]. Consequently, it contributes to the establishment and sustenance of relationships while fostering greater closeness with others [23]. Thus, gratitude diminishes the likelihood of an individual experiencing loneliness [24]. Furthermore, fathers play a crucial role in shaping the development of adolescents’ gratitude [25] because fathers offer direct guidance to adolescents regarding gratitude [26]. Simultaneously, fathers’ perceptions of emotional experiences, including gratitude, have an indirect yet significant influence on children’s development of gratitude [27,28]. Therefore, father-love absence may negatively predict individual levels of gratitude. Accordingly, we propose H2: father-love absence influences adolescents to develop loneliness through the mediating effect of gratitude.

The mediating role of peer relationships

Peer relationships encompass interpersonal connections formed and cultivated through shared activities and mutual support during interactions among individuals of the same age and similar levels of psychological development [29]. Peer relationships, functioning as microsystems influencing individual development, have a direct and profound influence on an individual’s loneliness [30]. This subjective experience of lacking peer relationships can evoke feelings of loneliness in individuals. As individuals enter adolescence, their focus on seeking intimacy and emotional support gradually shifts from parents to peers [31], and peer relationships become increasingly vital [32]. Consequently, adolescents with inadequate peer relationships face challenges in attaining social satisfaction and positive emotions from their peers, potentially resulting in loneliness. Similarly, the evidence with regard to the lower the quality of peer relationships, the greater the loneliness experienced by adolescents [33,34]. Regarding the relationship between father-love absence and peer relationships, adolescents experiencing father-love absence often exhibit a diminished sense of security in their interpersonal interactions. So, they face challenges in forming positive relationships with others [35]. In summary, this study proposes H3: father-love absence leads to loneliness through the mediating influence of peer relationships.

The chain mediation of gratitude to peer relationship

Gratitude is a positive emotion that contributes to the establishment of interpersonal relationships, which reduces an individual’s sense of isolation, diminishes the feelings of insecurity and instability [36]. Consequently, it can enhance an individual’s interaction with the external environment, fostering more positive peer social relationships [37–39]. On the other hand, gratitude also aids in repairing interpersonal relationships; individuals who exhibit gratitude can develop more positive perceptions of their partners, display a greater willingness to sustain long term relationship with others [40], and cultivate closer connections among their peers [41]. Therefore, individuals with high levels of gratitude enjoy more harmonious peer relationships.

According to social functionalist theory, emotions are formed in dynamic social interactions that are influenced by relationships [42]. At the same time, emotions can affect individual’s connections with others [43]. Keltner et al. further extended this theory, finding that emotions can also affect one’s interpersonal relationships [44]. Interactions with fathers, as an important interpersonal relationship for individuals, affect the individual’s emotion of gratitude. The emotion of gratitude affects one’s peer relationships. Conversely, connections and interactions with peers may further lead to the individual’s loneliness. Therefore, individuals with father-love absence may present less gratitude emotions, have weaker peer relationships, and possess more loneliness. Building on this premise, we advance H4: father-love absence influences adolescences’ loneliness through the chain mediation involving gratitude to peer relationships.

Prior research has demonstrated significant gender disparities in the consequences of father-love absence on mental health among adolescents. For instance, Sears et al. reported in their study that father-love absence was a stronger effect of aggressive behaviors in males [45]. McLanahan et al. indicated in their research that father-love absence had a more pronounced impact on the emotional and mental health development of males [46]. Hetherington et al. suggested in their study that women with father-love absence are less likely to form intimate relationships compared to men, which may result in heightened feelings of loneliness [47]. Therefore, building upon these previous findings and aligning with the preceding hypotheses, we introduce H5: Gender differences may exist in the mechanisms through which father-love absence affects loneliness between gratitude and peer relationships.

The purpose of the current study is to investigate the impact of father-love absence on adolescents’ loneliness, with a focus on the mediating roles played by gratitude and peer relationships. While some prior research has assessed the influence of early adverse environments on the mental health of adolescents [48–50], much of the existing literature has focused primarily on the effects of childhood maltreatment on adolescent loneliness. However, how father-love absence specifically affects feelings of loneliness in children and the underlying mechanisms has not been directly explored in previous research. At the same time, owing to the traditional division of family roles in China, the role and status of the father within the Chinese family have been consistently due to the distinctiveness of gender role. Resulting in a father-child relationship that diverges from those in other cultures. Chinese society confronts various challenges, including the high prevalence of parental divorce and the shift from the traditional extended family model to the nuclear family model. This could potentially contribute to an increasing absence of father in the Chinese society. Therefore, we recruited participants from China. In summary, utilizing the social functionalist theory, the social needs theory, and a review of relevant literature, this study aims to assess the link between father-love absence and feelings of loneliness.

In this study, questionnaire was administered to 2,148 students from a junior high school and a senior high school in Hunan Province, China. Some participants were excluded from the analyses, because neither those complete all the questionnaires, nor they filled out questionnaires indiscriminately. Thus, a total of 1,795 valid samples were collected, and the questionnaire completion rate was 83.56%. Among them, 319 students in the third year of junior high school, 568 were senior one school students, 462 were senior two school students, and 446 were senior three school students. The sample consisted of 774 males with a mean age of 16.23 ± 1.32 and 1021 females with a mean age of 16.33 ± 1.17. All participants were free from any mental health condition. They all provided handwritten informed consent prior to completing the questionnaire. All subjects signed an informed consent form before participating in the formal study. At the same time, we obtained full consent from teachers and parents before distributing the research questionnaire to the students. Detailed instructions were given to fill out the questionnaire. The study was approved and consented by the ethics approval of the authors’ institution.

The Father-Love Absence Scale (FLAS), developed by Xiang et al. [3], was used to assess the extent of father-love absence in adolescents. The scale is based on the Chinese cultural context and contains four subscales of emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and volitional deficits with a total of 18 items (e.g., “My father rarely considers things from my perspective”). Each item is scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (“completely inconsistent”) to 5 (“completely consistent”), with higher scores indicating a greater degree of father love deficit. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.901, and for the subscales, it was 0.878, 0.896, 0.827, and 0.866, respectively.

The Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6), developed by McCullough et al. [20] and adapted by Wei et al. [51], was used in this study, which contains a total of 6 items. The scale has been demonstrated to be suitable for the Chinese adolescent population and exhibits good reliability and validity [20]. Example of a question: I have many people and things in my life for which I am grateful. The questionnaire was scored on a 7-point scale, with 1 indicating total disagreement and 7 indicating total agreement; the third question was reverse scored. Higher scores on the questionnaire indicate greater gratitude. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this questionnaire was 0.706.

In this study, six items from the School Adjustment Scale developed by Cui [52] were used for peer relations, such as “My classmates are not friendly to me”. The scale has been demonstrated to be suitable for the Chinese adolescent population and exhibits good reliability and validity [53]. The scale is scored on a 5-point scale, with 1 being a complete discrepancy and 5 being a perfect match. Six questions are scored inversely, with higher scores indicating better peer relationships. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this questionnaire was 0.908.

The Loneliness Scale (UCLA Loneliness Scale, ULS-8) developed by Hays and Dimatteo [54] and adapted by Wu et al. [55] was used to assess individual loneliness in this study. The scale has been demonstrated to be suitable for the Chinese adolescent population and exhibits good reliability and validity [56]. The scale consists of eight items (e.g., if I were not there, others would be better off) and is scored on a 3-point scale ranging from ‘no’ to ‘yes’. The higher the scale score, the more lonely the individual. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.878.

First, a common method deviation analysis was performed on the data by Harman’s one-way test using validated factor analysis incorporating all variables into the same latent variable. The results revealed a very poor model fit index [

The constructed measurement models were then tested using AMOS 24.0 to examine how well the indicators predicted the underlying variables. The scale assessing father-love absence were split into four factors. The scale assessing gratitude were split into two factors. The question assessing peer relationships were split into three factors. The scale assessing loneliness were split into three factors. According to the suggestion by Hu et al. [57] and Kenny [58] for the model fit index,

Descriptive statistical analysis

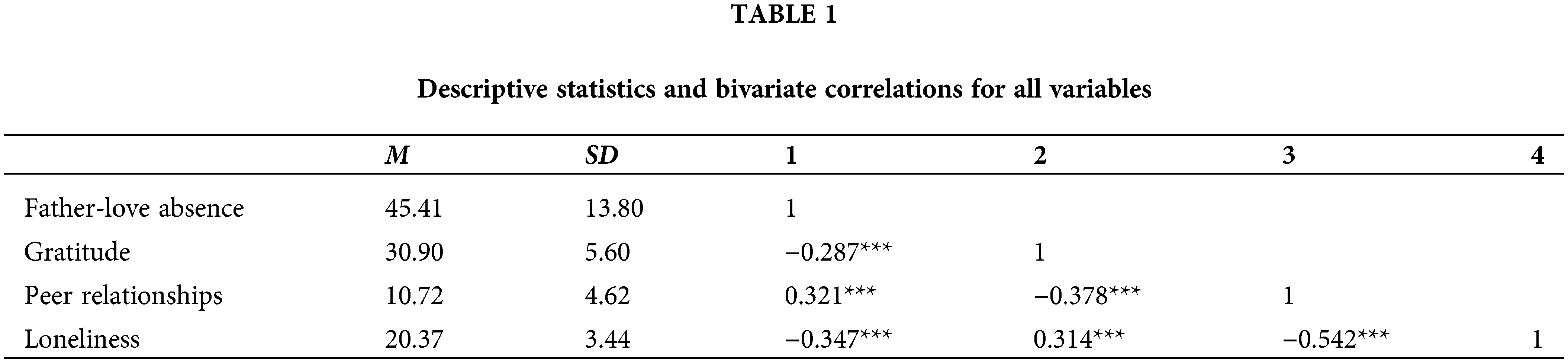

Descriptive statistics were utilized to illustrate the correlation among the variables. Table 1 displays the mean, standard deviation, and correlations among father-love absence, gratitude, peer relationships, and loneliness. Significant correlations exist between these variables. These findings offer preliminary support for the hypothesis.

The potential variables in the measurement model included father-love absence, gratitude, peer relationships, and loneliness. The results indicated that the data fit the measurement model well [

Structural model reasonableness assessment

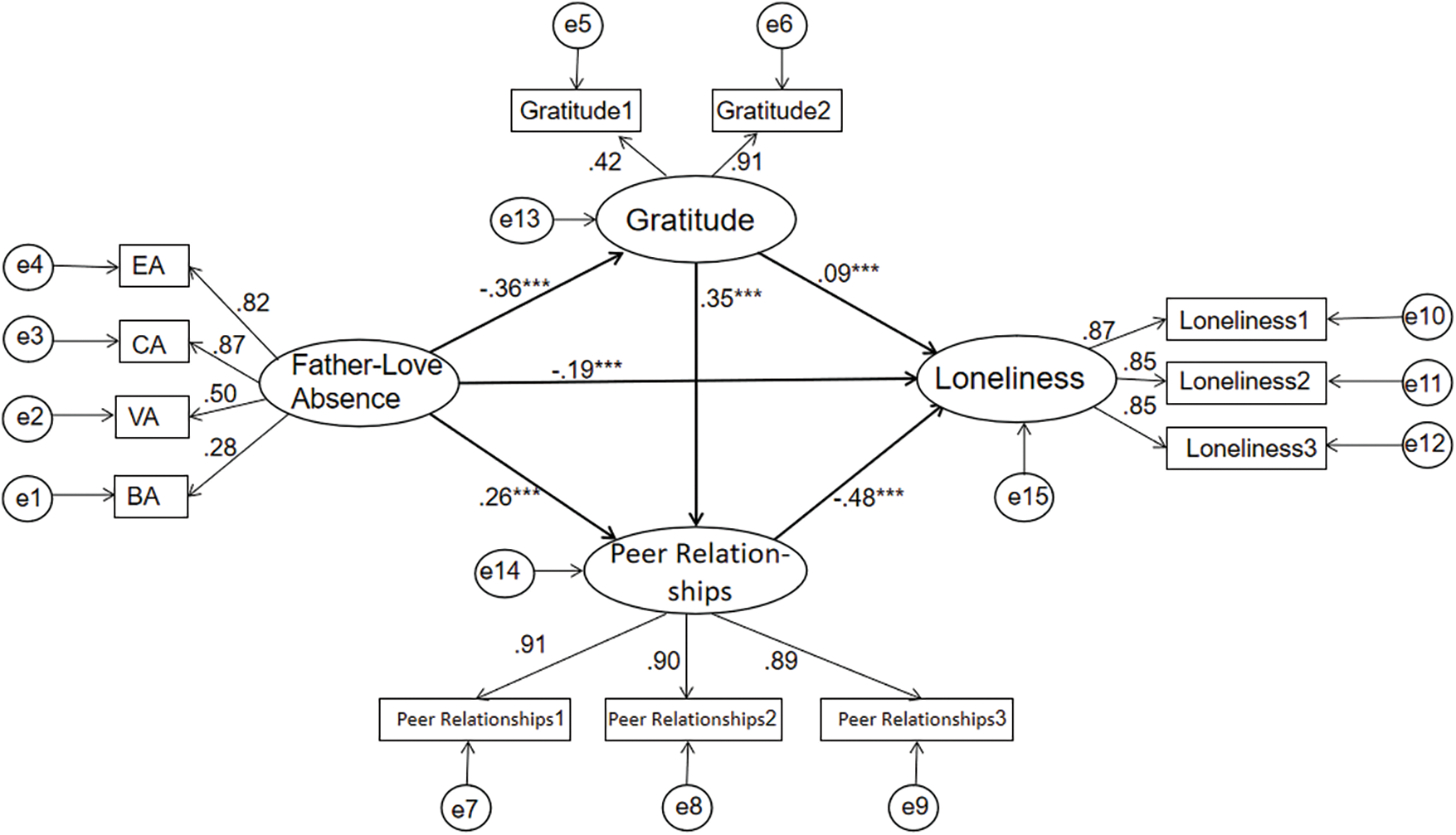

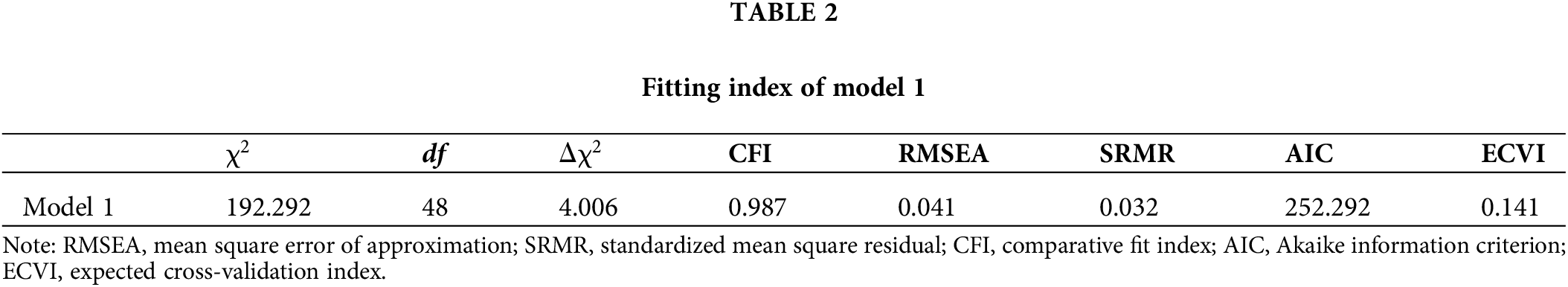

Without the mediating variables gratitude and peer relationships, father-love absence significantly predicts loneliness. Model 1 was then developed in which father-love absence directly predicts loneliness and also indirectly predicts loneliness through gratitude to peer relationships (see Fig. 1). The results showed a good fit of model 1 [

Figure 1: The chain mediation model 1. Note: The chain mediation model 1 examining the mediating effect of Father-Love Absence and Loneliness. Factor loading are standardized EA, CA, VA, and BA of Father-Love Absence. Gratitude 1 and Gratitude 2 of Gratitude. Peer Relationships 1, Peer Relationships 2, and Peer Relationships 3 of Peer Relationships. Loneliness 1, Loneliness 2, and Loneliness 3 of Loneliness. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Significance tests for mediating variables

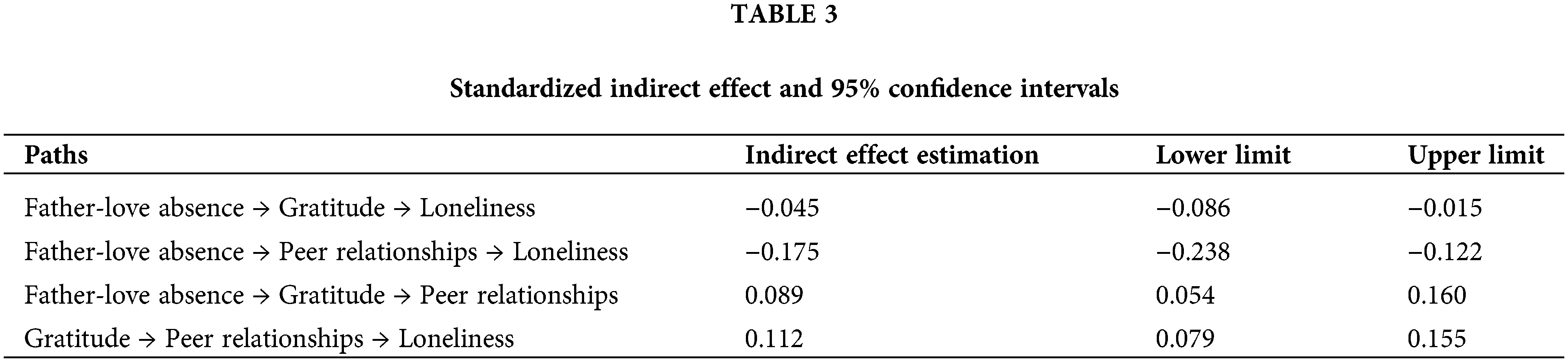

Also, the bootstrap method was used to test the stability of the model mediation effect by randomly sampling 2000 bootstrap samples generated from the original data set (N = 1795). The results showed that gratitude [−0.086, −0.015] and peer relationships [−0.238, −0.122] mediated significantly between father-love absence and loneliness at 95% confidence intervals. Gratitude [0.054, 0.160] played a significant role between father-love absence affecting peer relationships, and peer relationships [0.079, 0.155] between gratitude affecting loneliness (see Table 3).

Stability analysis of the model across gender

To test the stability of the structural model, the model was further analyzed for stability across gender. First, the five latent variables were tested for the presence of gender differences. The results showed that there were no significant gender differences in father-love absence [t(1795) = 0.846, p > 0.05], gratitude [t(1795) = −1.146, p > 0.05], and loneliness [t(1795) = 1.103, p > 0.05]. In contrast, there were significant gender differences in peer relationships [t(1795) = 2.084, p < 0.05] and the male peer relationship scores were higher than the female peer relationship scores.

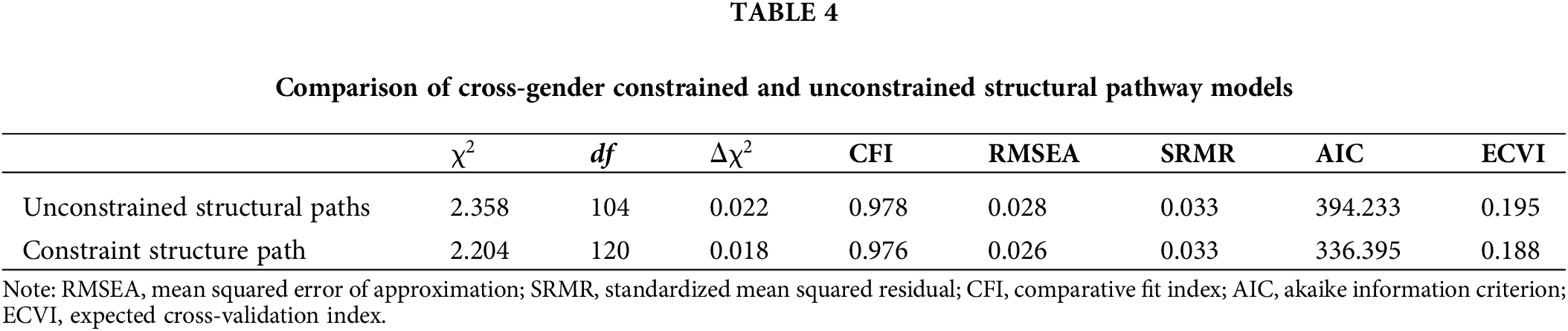

Based on the gender differences found, further multi-cluster analysis was used to examine the stability of the models. Based on the Byrne’s [59] study, two models were developed in this study, one allowing free estimation of pathways across gender (unconstrained structural pathways) and the other allowing significantly equal path coefficients for both genders (constrained structural pathways), while holding the underlying parameter factor loadings, error variances, and structural covariances constant. The results showed a significant difference between the two models [

Based on the social functionalist theory and the social needs theory, this study explored the mechanisms of gratitude and peer relationships in the relationship between father-love absence and loneliness. It was found that adolescents with father-love absence experienced more loneliness. In addition, adolescents experiencing father-love absence also indirectly affect loneliness through the mediating roles of gratitude, peer relationships and the chain of gratitude to peer relationships. The results of the study validate the idea that father-love absence causes loneliness and provide an in-depth discussion of the specific intermediary mechanisms between the factors, which provides a broader theoretical reference for curbing the generation of loneliness in adolescents with father-love absence.

Firstly, the results suggest that father-love absence positively predicts loneliness, meaning that adolescents with father-love absence perceive more loneliness, thereby confirming H1. This occurs because father-love absence not only reduces adolescents’ access to objective social support [61,62], but also causes adolescents to feel abandoned, thereby impacts perceived subjective social support [63]. When adolescents lack sufficient social support, they tend to develop feelings of isolation [46,64]. Furthermore, fathers interact with their children in a more authoritative and serious manner than mothers, thus fathers play an irreplaceable role in children’s emotional development [65]. Consequently, adolescents who experience father-love absence tend to have more emotional problems, including the negative feeling of loneliness [66]. The findings align with the social needs theory, suggesting that individuals experiencing father-love absence have unmet emotional needs, leading to increased loneliness. This perspective can also be illuminated through the lens of psychodynamic theory, which suggests that father-love absence adolescents with early attachment deficits are more likely to feel lonely. Because they tend to distrust others and try to maintain emotional distance to preserve their independence [67]. Therefore, adolescents with father-love absence have higher levels of loneliness.

Second, mediation analyses tested H2 that gratitude plays a significant mediating role in the effect of father-love absence on loneliness. adolescents with father-love absence tend to feel less loved, cared for, and supported [68,69], while gratitude is often cultivated in positive interpersonal experiences [70] and developed by being loved and supported [71,72]. Therefore, adolescents with father-love absence are less likely to be grateful [73]. When adolescents are grateful to others, they are more motivated to care for others and engage in more reciprocal pro-social behaviors [74], which is an important way to alleviate feelings of loneliness [75]. In addition to changing behavior, gratitude increases adolescents’ positive perceptions of and satisfaction with their relationships [39], leading to more good relationships and less loneliness. Therefore, adolescents with high gratitude traits experience less loneliness [24]. Therefore, father-love absence reduces adolescents’ loneliness through gratitude.

The results tested H3, that peer relationships play a significant mediating role in the effect of father-love absence on loneliness. Father-love absence, as a typical early adverse environment, can cause adolescents to experience great stress [62,76], and stress can undermine adolescents’ sense of security [77]. Adolescents who do not feel secure enough usually lack social skills [78] and are less likely to have good peer relationships. Meanwhile, adolescents with father-love absence lack direct guidance from their fathers on how to handle interpersonal relationships [79] and social learning experiences on how to get along with peers [80] possess limited adolescents weaker in interpersonal skills and poorer in peer relationships. Therefore, father-love absence may lead to increased loneliness due to poorer peer relationships.

Additionally, the results of the cross-gender stability analyses reveal gender differences in the influence of father-love absence on adolescents’ peer relationships, H5 was partially tested. Father-love absence can have a more profound impact on peer relationships for females than for males. For females, the father is often the first person of the opposite sex they encounter from birth, and the father’s attitudes toward his daughter as she matures can influence her attitudes toward others and her peer relationships [81]. Previous research has also shown that females tend to exhibit higher levels of dependence on and affection toward their fathers, seeking a sense of security from their father’s love more than from any other person [82]. As a result, females with father-love absence often experience heightened insecurity compared with males, which can hinder their ability to form close relationships with others [47] and lead to poorer peer relationships. The findings also reveal that the poorer the peer relationships adolescents have, the more likely they could feel lonely [83]. This is because peer relationships are an integral part of socialization [84], and adolescents with poor peer relationships who often avoid problems in interpersonal interactions or use inappropriate relationship handling [85] are prone to social problems. Social problems can cause adolescents to feel unable to form good intimate relationships with others, thus experience higher levels of loneliness [86]. There are also empirical studies that support that peer relationships negatively predict loneliness [87]. Therefore, father-love absence can have a more profound impact on peer relationships for females than for males.

In addition, father-love absence also affects loneliness through the chain mediated pathway of “gratitude to peer relationships”, confirming hypothesis H4. Furthermore, this supports the social functionalist theory, suggesting that adolescents experiencing father-love absence, who do not have their relational needs fulfilled, tend to exhibit lower levels of gratitude. Expressing gratitude towards one another is deemed a vital behavior for sustaining peer relationships [71]. This is because grateful adolescents tend to notice positive behaviors of others, are more likely to value their peers more, and are willing to engage in more relationship maintenance behaviors [37]. At the same time, expressing gratitude builds personal interpersonal relationships by being kind and considerate, which are actually meaningful in maintaining relationship [88]. Therefore, grateful adolescents have better peer relationships. Furthermore, interactions and relationships with peers can significantly impact an individual’s experience of loneliness [89]. Thus, father-love absence also affects loneliness through the continuous mediation of gratitude to peer relationships.

The current study investigated the impact of father-love absence on adolescents’ loneliness and extended this inquiry by examining the mechanisms through which gratitude, peer relationships and gratitude to peer relationships mediate this association. However, the findings in this study have limitations and we suggest directions for future study to supplement the limitations. First, all of the data in this study were self-reported, so there may be social biases such as social desirability effects. Future studies could reveal causal associations between variables through the experimental design. Secondly, this study adopted a cross-sectional design, allowing preliminary insights into variable relationships, but establishing definitive relationships necessitates verification through longitudinal study or experimental research designs. Third, it is important to note that the participants in this study were exclusively students from mainland China. Therefore, future research should consider including subjects from diverse cultural backgrounds.

This study examines the effects of father-love absence on adolescent loneliness and its underlying mechanisms. The results reveal the detrimental effects of father-love absence on adolescent development, expanding the knowledge about the relationship between fathers and child development. From the perspective of academic research, the findings expand upon the social functionalist theory, indicating that individuals experiencing father-love absence influence the development of gratitude, their peer relationships, and increase adolescent loneliness. Concurrently, these results extend the social needs theory, positing that adolescents experiencing father-love absence struggle to fulfill their emotional requirements, rendering them more susceptible to loneliness. Furthermore, while previous studies have indicated that a father’s physical absence impacts the emotional development of individuals, resulting in the development of adverse mental health [90], this current study extends this understanding by highlighting that a father’s love absence also has implications for the emotional well-being of individuals. The study expands the understanding of the complex relationship between family relationships and adolescent mental health, with a particular emphasis on the critical role of fathers in the development of adolescent mental health. It contributes to further research in the field of family psychology and provides a strong basis for understanding how family relationships affect individual mental health.

From the perspective of practice, the results of the study provide a valuable foundation for investigating and addressing the adverse consequences of early adversity. The findings suggest that mitigating the impact of father-love absence on adolescent loneliness by fostering individual gratitude and enhancing the quality of peer relationships. It significantly promotes mental health under educational and societal contexts. This research extends practical recommendations for mental health practitioners to the fields of family and education for the enhancement of adolescent mental health.

In conclusion, this study not only enriches our comprehension of the association between family dynamics and adolescent mental health, but also provides us a compelling rationale for research and practice, with important theoretical and practical implications on promote teenagers’ mental health and well-being.

The present study demonstrates the association between father-love absence and loneliness, as well as the mediating roles of gratitude, peer relationships, and gratitude to peer relationships. By doing so, this research extends the current knowledge regarding the relationship between father-love absence and loneliness and thereby extends the social functionalist theory and the social needs theory. It places significant importance on father’s love from the perspective of adolescent mental health. And the findings could give some insights on early childhood intervention for loneliness, and help educators and mental health practitioners to understand the source of loneliness among the teenagers, therefore to promote the awareness of fathers’ love among the family structure in the society to ensure the wellbeings of teenagers from the scope of love.

Acknowledgement: We thank the General Program of the National Social Science Fund of China for providing grant on our research, all study participants for their cooperation and support, all members of the research group for data collection.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the General Program of the National Socail Science Fund of China (23BSH144).

Author Contributions: Yaping Zhou: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. He Zhong: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. Xiaojun Li: Data Collection, Conceptualization, Writing-Review & Editing. Yanhui Xiang: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing-Review & Editing.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data will be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Hunan Normal University (IRB number: 051). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gao F, Li X. From one to three: China’s motherhood dilemma and obstacle to gender equality. Women. 2021;1(4):252–66. doi:10.3390/women1040022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Trivedi S, Bose K. Fatherhood and roles of father in children’s upbringing in Botswana: fathers’ perspectives. J Fam Stud. 2020;26(4):550–63. doi:10.1080/13229400.2018.1439399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xiang Y, Zhou Y. Development and validation of the father-love absence scale for adolescents. Behav Sci. 2023;13(5):435. doi:10.3390/bs13050435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Culpin I, Heuvelman H, Rai D, Pearson RM, Joinson C, Heron J, et al. Father absence and trajectories of offspring mental health across adolescence and young adulthood: findings from a UK-birth cohort. J Affect Disorders. 2022;314(3):150–9. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.07.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Rokach A. The psychological journey to and from loneliness: development, causes, and effects of social and emotional isolation. New York: Academic Press; 2019. doi:10.1016/C2017-0-03510-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Qualter P, Vanhalst J, Harris R, van Roekel E, Lodder G, Bangee M, et al. Loneliness across the life span. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):250–64. doi:10.1177/1745691615568999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Aging and loneliness: downhill quickly? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16(4):187–91. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00501.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Qi X, Belsky D, Yang Y, Ng T, Wu B. Joint trajectories of social isolation and loneliness and their effects on accelerated biological aging. Innov Aging. 2022;6(Supplement_1):179. doi:10.1093/geroni/igac059.718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shiovitz-Ezra S, Ayalon L. Situational versus chronic loneliness as risk factors for all-cause mortality. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):455–62. doi:10.1017/S1041610209991426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mushtaq R, Shoib S, Shah T, Mushtaq S. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2014;8(9):WE01. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Quadt L, Esposito G, Critchley HD, Garfinkel SN. Brain-body interactions underlying the association of loneliness with mental and physical health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;116(9):283–300. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.06.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Twenge JM, Haidt J, Blake AB, McAllister C, Lemon H, Le Roy A. Worldwide increases in adolescent loneliness. J Adolescence. 2021;93(1):257–69. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Segrin C, Nevarez N, Arroyo A, Harwood J. Family of origin environment and adolescent bullying predict young adult loneliness. In: Loneliness updated. London: Routledge; 2013. p. 138–153. [Google Scholar]

14. Reichmann FF. Loneliness. Psychiatr. 1959;22(1):1–15. doi:10.1080/00332747.1959.11023153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sullivan HS. An introduction to theories of personality. Vermont: Psychology Press; 2014. p. 137–56. [Google Scholar]

16. Terrell-Deutsch B. The conceptualization and measurement of childhood loneliness. Loneliness Childhood Adolesc. 1999:11–33. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511551888.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Asher SR, Hymel S, Renshaw PD. Loneliness in children. Child Dev. 1984;55(4):1456. doi:10.2307/1130015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Weiss RS. Reflections on the present state of loneliness research. J Soc Behav Pers. 1987;2(2):1. [Google Scholar]

19. Krampe EM. When is the father really there? A conceptual reformulation of father presence. J Fam Issues. 2009;30(7):875–97. doi:10.1177/0192513X08331008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Emmons RA, Shelton CM. Gratitude and the science of positive psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002;18:459–71. [Google Scholar]

22. Algoe SB, Zhaoyang R. Positive psychology in context: effects of expressing gratitude in ongoing relationships depend on perceptions of enactor responsiveness. J Posit Psychol. 2016;11(4):399–415. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1117131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. O’Connell BH, O’Shea D, Gallagher S. Examining psychosocial pathways underlying gratitude interventions: a randomized controlled trial. J Happiness Stud. 2018;19(8):2421–44. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9931-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Adam JT. How the company of others and being alone affect feelings of loneliness and gratitude: an experience sampling study (Bachelor’s Thesis). University of Twente: Netherlands; 2020. [Google Scholar]

25. Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc Dev. 2007;16(2):361–88. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychol Inq. 1998;9(4):241–73. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Castro VL, Halberstadt AG, Lozada FT, Craig AB. Parents’ emotion-related beliefs, behaviours, and skills predict children’s recognition of emotion. Infant Child Dev. 2015;24(1):1–22. doi:10.1002/icd.1868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Stelter RL, Halberstadt AG. The interplay between parental beliefs about children’s emotions and parental stress impacts children’s attachment security. Infant Child Dev. 2011;20(3):272–87. doi:10.1002/icd.693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Coplan RJ, Gavinski-Molina MH, Lagace-Seguin DG, Wichmann C. When girls versus boys play alone: nonsocial play and adjustment in kindergarten. Dev Psychol. 2001;37(4):464–74. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Cassidy J, Asher SR. Loneliness and peer relations in young children. Child Dev. 2010;63(2):350–65. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01632.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Dijkstra JK, Veenstra R. Encyclopedia of adolescence. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. 2011;2:255–9. [Google Scholar]

32. Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Bowker JC. Children in peer groups. Handb Child Psychol Dev Sci. 2015;4:175–222. doi:10.1002/9781118963418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Schwartz-Mette RA, Shankman J, Dueweke AR, Borowski S, Rose AJ. Relations of friendship experiences with depressive symptoms and loneliness in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2020;146(8):664–700. doi:10.1037/bul0000239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang Y, Xie Q, Li Y, Zhu J. The relationship between attachment avoidance and preschool children’s loneliness: the mediating role of peer rejection and moderating role of teacher-child relationship. J Psychol Sci. 2021;44(3):598–604. doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20210312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chen H, Zhang H, Yin J, Cheng X, Wang M. Father’s rearing attitude and its prediction for 4~7-year-old children’s behavioral problems and school adjustment. J Psychol Sci. 2004;(5):1041–5. doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2004.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dittrich SM. Understanding the association between gratitude and loneliness in daily life: an experience sampling study (Master’s Thesis). University of Twente: Netherlands; 2021. [Google Scholar]

37. Leong JL, Chen SX, Fung HH, Bond MH, Siu NY, Zhu JY. Is gratitude always beneficial to interpersonal relationships? The interplay of grateful disposition, grateful mood, and grateful expression among married couples. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2020;46(1):64–78. doi:10.1177/0146167219842868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Caleon IS, Ilham NQB, Ong CL, Tan JPL. Cascading effects of gratitude: a sequential mediation analysis of gratitude, interpersonal relationships, school resilience and school well-being. Asia Pac Educ Res. 2019;28(4):303–12. doi:10.1007/s40299-019-00440-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Algoe SB, Gable SL, Maisel NC. It’s the little things: everyday gratitude as a booster shot for romantic relationships. Pers Relationship. 2010;17(2):217–33. doi:10.1111/(ISSN)1475-6811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kubacka KE, Finkenauer C, Rusbult CE, Keijsers L. Maintaining close relationships: gratitude as a motivator and a detector of maintenance behavior. Pers Soc Psychol B. 2011;37(10):1362–75. doi:10.1177/0146167211412196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang P, Ye L, Fu F, Zhang LG. The influence of gratitude on the meaning of life: the mediating effect of family function and peer relationship. Front Psychol. 2021;12:680795. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Clark MS, Hirsch JL, Monin JK. Love conceptualized as mutual communal responsiveness. The new psychology of love. 2019;84–114. doi:10.1017/9781108658225.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Keltner D, Sauter D, Tracy JL, Wetchler E, Cowen AS. How emotions, relationships, and culture constitute each other: advances in social functionalist theory. Cogn Emot. 2022;36(3):388–401. doi:10.1080/02699931.2022.2047009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Sears RR, Pintler MH, Sears PS. Effect of father separation on preschool children’s doll play aggression. Child Dev. 1946;17(4):219–43. doi:10.2307/3181738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. McLanahan S, Tach L, Schneider D. The causal effects of father absence. Annu Rev Sociol. 2013;39(1):399–427. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Hetherington EM, Cox M, Cox R. Divorced fathers. Fam Coord. 1976;25(4):417–28. doi:10.2307/582856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Khan M, Renk K. Mothers’ adverse childhood experiences, depressive symptoms, parenting, and attachment as predictors of young children’s problems. J Child Custody. 2019;16(3):268–90. doi:10.1080/15379418.2019.1575318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Esteves K, Gray SA, Theall KP, Drury SS. Impact of physical abuse on internalizing behavior across generations. J Child Fam Stud. 2017;26(10):2753–61. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0780-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R. Family-strengthening approaches for the prevention of youth problem behaviors. Am Psychol. 2003;58(6–7):457. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Wei C, Wu H, Kong X, Wang H. Revision of gratitude questionnaire-6 in Chinese adolescent and its validity and reliability Chinese. J School Health. 2011;(10):1201–2. doi:10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2011.10.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Cui N. A study on the relationship of school adaptation and self-conception among junior school students (Bachelor’s Thesis). Southwest University: China; 2008. [Google Scholar]

53. Hou J. A synthesis of the definition and measurement of school adaptation. J Cap Normal Univ (Soc Sci Ed). 2012;(5):99–104. [Google Scholar]

54. Hays RD, DiMatteo MR. A short-form measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess. 1987;51(1):69–81. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5101_6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Wu CH, Yao G. Psychometric analysis of the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8) in Taiwanese undergraduate students. Pers Indiv Differ. 2008;44(8):1762–71. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Xu S, Qiu D, Hahne J, Zhao M, Hu M. Psychometric properties of the short-form UCLA loneliness scale (ULS-8) among Chinese adolescents. Med. 2018;97(38):e12373. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55 615. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Kenny DA. Measuring model fit. Davidakenny.net. 2012;1985:1–10. [Google Scholar]

59. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int J Test. 2001;1(1):55–86. doi:10.1207/S15327574IJT0101_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Arbuckle JL. AMOS 5.0 update to the AMOS user’s guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters; 2003. [Google Scholar]

61. Foster EM, Kalil A. Living arrangements and children’s development in low-income white, black, and latino families. Child Dev. 2007;78(6):1657–74. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01091.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Hout M. Social and economic returns to college education in the United States. Annu Rev Sociol. 2012;38(1):379–400. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Zhang X, Dong S. The relationships between social support and loneliness: a meta-analysis and review. Acta Psychol. 2022;227(7):103616. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Amodia-Bidakowska A, Laverty C, Ramchandani PG. Father-child play: a systematic review of its frequency, characteristics and potential impact on children’s development. Dev Rev. 2020;57(6):100924. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2020.100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Rokach A. The psychological journey to and from loneliness: development, causes, and effects of social and emotional isolation. New York: Academic Press; 2019. doi:10.1016/C2017-0-03510-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Xie X, Duan H, Gu C. Older adults’ attachment affects their satisfaction with life: the mediating effect of loneliness. J Psychol Sci. 2014;(6):1421–5. doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2014.06.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Buck R. The gratitude of exchange and the gratitude of caring: a developmental-interactionist perspective of moral emotion. Psychol Gratitude. 2004; 100–22. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195150100.003.0006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Mcadams DP, Bauer JJ. Gratitude in modern life: its manifestations and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

69. Algoe SB. Find, remind, and bind: the functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2012;6(6):455–69. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Li S. A mechanism for gratitude development in a child. Early Child Dev Care. 2016;186(3):466–79. doi:10.1080/03004430.2015.1043911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Kong F, Ding K, Zhao J. The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, social support and life satisfaction among undergraduate students. J Happiness Stud. 2015;16(2):477–89. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9519-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Lin CC. The influence of parenting on gratitude during emerging adulthood: the mediating effect of time perspective. Curr Psychol. 2021; 1–11. doi:10.1007/s12144-020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Bartlett MY, Condon P, Cruz J, Baumann J, Desteno D. Gratitude: prompting behaviours that build relationships. Cogn Emot. 2012;26(1):2–13. doi:10.1080/02699931.2011.561297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Chen W, Li X, Huebner ES, Tian L. Parent-child cohesion, loneliness, and prosocial behavior: longitudinal relations in children. J Soc Pers Relat. 2022;39(9):2939–63. doi:10.1177/02654075221091178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Ni S, Yang R, Zhang Y, Dong R. Effect of gratitude on loneliness of Chinese college students: social support as a mediator. Soc Behav Pers. 2015;43(4):559–66. doi:10.2224/sbp.2015.43.4.559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Flouri E, Buchanan A. The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. J Adolesc. 2003;26(1):63–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00116-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Ye B, Hu J, Im H, Liu M, Wang X, Yang Q. Perceived stress and insomnia under the period of COVID-19: the mediating role of sense of security and the moderating role of family cohesion. 2020. doi:10.31234/osf.io/6q78h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Hong S, Hardi F, Maguire-Jack K. The moderating role of neighborhood social cohesion on the relationship between early mother-child attachment security and adolescent social skills: brief report. J Soc Pers Relat. 2023;40(1):277–87. doi:10.1177/02654075221118096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. McDowell DJ, Parke RD. Parental correlates of children’s peer relations: an empirical test of a tripartite model. Dev Psychol. 2009;45(1):224. doi:10.1037/a0014305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Leidy MS, Schofield TJ, Parke RD. Fathers’ contributions to children’s social development. In: Handbook of father involvement: multidisciplinary perspectives. New York; 1979. p. 151–67. [Google Scholar]

81. Cavanagh SE, Huston AC. Family instability and children’s early problem behavior. Soc Forces. 2006;85(1):551–81. doi:10.1353/sof.2006.0120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Bussey K, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychol Rev. 1999;106(4):676. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, et al. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(9):939–91. doi:10.1037/bul0000110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Mead GH. Mind, self & society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

85. Chang CH, Ferris DL, Johnson RE, Rosen CC, Tan JA. Core self-evaluations: a review and evaluation of the literature. J Manage. 2012;38(1):81–128. doi:10.1177/0149206311419661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Dell NA, Pelham M, Murphy AM. Loneliness and depressive symptoms in middle aged and older adults experiencing serious mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2019;42(2):113–20. doi:10.1037/prj0000347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Heinrich LM, Gullone E. The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(6):695–718. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Lambert NM, Fincham FD. Expressing gratitude to a partner leads to more relationship maintenance behavior. Emotion. 2011;11(1):52–60. doi:10.1037/a0021557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Uruk AC, Demir A. The role of peers and families in predicting the loneliness level of adolescents. J Psychol. 2003;137(2):179–93. doi:10.1080/00223980309600607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Sigle-Rushton W, McLanahan S. Father absence and child well-being: a critical review. Future Fam. 2004;116:120–1. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools