Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Self-Compassion Moderates the Effect of Contingent Self-Esteem on Well-Being: Evidence from Cross-Sectional Survey and Experiment

1 Mental Health Education and Counseling Center, Shanghai University of International Business and Economics, Shanghai, 201620, China

2 School of Communication Engineering, Hangzhou Dianzi University, Hangzhou, 310018, China

3 School of Languages, Shanghai University of International Business and Economics, Shanghai, 201620, China

4 School of Computer Science and Information Technology, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, 130117, China

5 Library, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, 130024, China

* Corresponding Author: Haoran Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health and Social Development)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(2), 117-126. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.045819

Received 08 September 2023; Accepted 13 December 2023; Issue published 08 March 2024

Abstract

Contingent self-esteem captures the fragile nature of self-esteem and is often regarded as suboptimal to psychological functioning. Self-compassion is another important self-related concept assumed to promote mental health and well-being. However, research on the relation of self-compassion to contingent self-esteem is lacking. Two studies were conducted to explore the role of self-compassion, either as a personal characteristic or an induced mindset, in influencing the effects of contingent self-esteem on well-being. Study 1 recruited 256 Chinese college students (30.4% male, mean age = 21.72 years) who filled out measures of contingent self-esteem, self-compassion, and well-being. The results found that self-compassion moderated the effect of contingent self-esteem on well-being. In Study 2, a sample of 90 Chinese college students (34% male, mean age = 18.39 years) were randomly assigned to either a control or self-compassion group. They completed baseline trait measures of contingent self-esteem, self-compassion, and self-esteem. Then, they were led to have a 12-min break (control group) or listen to a 12-min self-compassion audio (self-compassion group), followed by a social stress task and outcome measures. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of the brief self-compassion training and its moderating role in influencing the effects of contingent self-esteem on negative affects after the social stress task. This research provides implications that to equip with a self-compassionate mindset could lower the risk of the impairment of well-being associated with elements of contingent self-esteem, which involves a fragile sense of self-worth. It may also provide insights into the development of an “optimal self-esteem” and the improvement of well-being.Keywords

Contingent self-esteem and well-being

Self-esteem is fragile, given its contingent character [1–4]. Contingent self-esteem [1,3] postulates a rather stable individual difference in the general tendency of one’s self-worth to be influenced by the success or failure of daily events, capturing the fragile nature of self-esteem. If an individual’s self-worth fluctuates greatly due to success or failure, he or she has a high contingent self-esteem. The current work adopted an inter-individual perspective of contingent self-esteem and viewed contingent self-esteem as denoting the tendency for one’s self-worth to be influenced by one’s general feelings of success or failure [1,5]. Contingent self-esteem captures the extent to which one’s self-worth depends on meeting certain standards or expectations. Deci and Ryan proposed contingency of self-esteem as opposed to true self in the framework of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [1]. True self-esteem refers to feelings of self-worth that are well-anchored and secure, such that they do not depend on the attainment of particular outcomes and would predict self-determined behaviors, optimal functioning, and well-being [6], whereas contingent self-esteem is developed on the basis that to gain self-worth, one is required to match or satisfy external standards.

Contingent self-esteem reflects the fragile nature of self-esteem, and the desire or expectancy to feel self-worthy requires continual validation to meet the standards of contingencies and can be costly [7]. Contingent self-esteem connotes self-judgment and social comparison [1,8], which backfires and is associated with psychological vulnerability and fluctuated self-attitude [9]. Such exertion functions at a cost and exhausts the self [10]. Contingent self-esteem is often associated with maladaptive coping and psychological vulnerability, encountering threats against the self [5]. For people with high contingent self-esteem, their psychological functioning may be influenced greatly by negative events or threats, thereby being vulnerable to experiencing negative emotions [3].

Given that contingent self-esteem involved depending self-worthiness on external factors, one of the frequent criticisms of contingent self-esteem was that it could make individual’s sense of life meaning and happiness susceptible to things outside of their own control and lead to their vulnerability being enabled to find contentment and peace within themselves. For that reason, if one can cultivate an inner quality that anchors ego, even in the face of external harshness, one can still maintain an inner balance and emotional equanimity to deal with the hardship. Identifying such factors is important, as it could shed light on how to maintain self-worth in response to self-esteem threats and promote well-being.

Compassion tuned towards the self, known as self-compassion denotes offering warmth and understanding to self in situations of suffering, inadequacy, or failure rather than being cold, indifferent, or critical of self [8]. Self-compassion was proposed as an adaptive attitude towards the self and consisted of three components: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness [8]. Some [11] regarded self-compassion as the ability to soothe distress with a non-critical attitude towards the self. Evidence has reported that self-compassion was linked to greater positive psychological outcomes (e.g., optimism, happiness), less depressive symptoms, and anxiety [12].

Self-compassion and self-esteem both involve a positive attitude or evaluation towards the self and both have been shown to relate to greater well-being, but the underlying mechanism as well as their long-term effects may be different [13,14]. Self-esteem is subject to a contingency. Self-compassion is distinguished from self-esteem in the process of how to pursue a positive self-regard, to obtain positive self-evaluation in order to have self-esteem, the process is often based on the validation of contingencies of self-worth, as summarized by Neff [15] to explain why self-compassion brings benefits without pitfalls compared with self-esteem. Self-compassion is developed on the basis of accepting both the strengths and weaknesses of the self, one has no need to validate or justify his or her self-worth because it is always there even facing failures. One study [16] compared the reactions to positive/negative events of people with high and low self-compassion and people with high and low self-esteem. The results found self-compassionate individuals had more attenuated and consistent reaction towards both positive and negative events while high self-esteem individuals had stronger and different reactions towards positive and negative events. For individuals with high self-esteem, they resisted accurately recognizing their shortcomings and behaved in a defensive manner to maintain or protect their self-worth, whereas self-compassionate individuals compassionately acknowledged and embraced their problems and shortcomings, recognizing both positive and negative events as an experience shared by everyone, thus allowing them to avoid being self-deprecating and self-enhancing to protect self-esteem. Indeed researchers found that when compared to trait levels of self-esteem, self-compassion was associated with more non-contingent and stable feelings of self-worth over time [13]. Therefore, self-compassion played an important role in self-esteem stability and was regarded as “optimal self-esteem” by researchers [13].

Self-compassion is rooted in sympathy extended toward the self when an individual is faced with a mistake or failure. Some suggested self-compassion could be a useful self-regulation strategy for handling stressful life events [17] or represent a positive cognitive bias when encountering difficulties [18]. Clinical psychologists tried to design and conduct interventions to promote self-compassion to reveal the protective role of self-compassion [11,19]. Growing effort has been devoted to implementing self-compassion interventions to promote mental health, and considerate evidence has validated the benefits of inducing a self-compassionate mindset [20–22].

The moderating role of self-compassion in relation to contingent self-esteem

In terms of the relation of self-compassion to contingent self-esteem, as discussed before, self-compassion entails less contingent self-worth [15], and self-compassionate individuals have a more balanced reaction to suffering or stressful events with a non-evaluative attitude [23,24]. A study [13] showed that contingent self-esteem and self-compassion were inversely related. A study among women found that self-compassion moderated the negative relationship between appearance-contingent self-worth and body appreciation [25]. The willingness to embrace failure, a quality possessed by self-compassion, may foster successful self-regulation even for people with highly contingent self-esteem [26].

Compassion is concerned with alleviating suffering, and self-compassion is concerned with offering care and warmth to the pain of one’s own. Based on accepting one’s strengths and weaknesses, self-compassion allows one to recognize failures as opportunities to acknowledge personal weakness and learn or improve, thus promoting self-regulation with less defensiveness and reduced emotional reactions [8,27]. Therefore, self-compassion would be a protective factor against the costs of contingent self-esteem.

Self-compassion enables one to acknowledge painful feelings as part of humanity, embrace those feelings, and be kind to oneself in the face of negative events or suffering [8]. Individuals with high contingent self-esteem may be critical of themselves with negative thoughts or emotions and experience diminished self-esteem if they do not meet standards set by themselves or others. Self-compassion can come in to attenuate those negative thoughts or feelings. When experiencing suffering and painful feelings due to emotionally distressing life events or personal inadequacy, a compassionate stance toward self with kindness, connectedness, and equanimity appears to help attenuate this sense of shame and other negative emotions [11,13]. Combining mindful thought with self-compassion frees one from emotional pain and mental rumination, contributing to the development of fearless generosity, inclusion, and sustained loving-kindness [28]. One study [18] revealed that self-compassion was negatively correlated with maladaptive coping strategies and positively with adaptive coping strategies, such as reinterpretation and acceptance following a failure among students. With a more adaptive way to approach these negative feelings, individuals are more likely to provide themselves with greater stability of self-worth and attain an internal sense of self-respect [29]. Consequently, we expected that self-compassion could buffer the negative effects of contingent self-esteem on well-being, especially when encountering difficult situations, for example, in the face of negative or threatening daily events.

Previous researchers suggested several ways to attenuate the costs of contingent self-esteem. For example, one can develop authentic relationships or change contingencies from external to internal [9]. Given that previous evidence appears to indicate a moderating role of self-compassion in relation to contingent self-esteem and the empirical research is lacking, in the following two studies, we investigated whether trait self-compassion (Study 1) or induced self-compassion in an experimental setting (Study 2), would interact with contingent self-esteem to influence well-being.

The current research would provide both cross-sectional and experimental evidence on whether self-compassion could be the alternative to shifting away from self-focused, self-centered goals of maintaining and protecting self-esteem to goals that connect to the self compassionately. It may also add knowledge to the modification of the contingencies associated with self-esteem and the development of “optimal self-esteem”.

In line with previous arguments, a compassionate self-entails the belief that one is worthy of acceptance. Self-compassionate individuals acknowledged their problems and shortcomings without judgment, and they recognized that both positive and negative events as experienced by everyone, they are less likely to struggle to validate their self-worth in the face of negative life events [8]. Therefore, even for individuals with high contingent self-esteem, i.e., whose self-worth is highly likely to be influenced by outer standards, self-compassion can equip them with a nonjudgmental attitude and open mind, thus protecting them from the costs of contingent self-esteem. In contrast, for high contingent individuals who are also not holding an accepting and compassionate attitude toward the self, or in other words, who are also with low self-compassion, it is likely that they would be more vulnerable to negative events and to feel greater threat to their self-worth, thus resulting in diminished well-being. Study 1 was guided by the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis: Self-compassion would moderate the effects of contingent self-esteem on well-being.

After obtaining ethics approval, 256 Chinese undergraduates (30.4% male) were recruited for this study, their average age was 21.72 years (SD = 4.73). Upon informed consent, they completed a set of self-reported questionnaires and demographic information. After completion of the questionnaire package, debriefing was provided to the participants.

The questionnaires consist of three scales and were administered in Chinese. Except for scales used in previous studies among Chinese people and proved reliable and valid, the other scales were translated into Chinese following the back-translation procedures [30], and some ambiguous words were discussed before administration. At the baseline, participants completed the measurements of contingent self-esteem and self-compassion.

Contingent Self-Esteem (CSE) Scale—originally developed by Paradise and Kernis [31] has been validated in later studies [6,32] involves 15 items that measure the degree to which a person’s sense of self-worth is dependent upon meeting expectations, matching standards, or achieving specific outcomes or evaluations. Example items include “My overall feelings about myself are heavily influenced by how much other people like and accept me” and “Even in the face of failure, my feelings of self-worth remain unaffected” (reverse coded). After rescaling the reversed items, a higher score indicates greater contingent self-esteem. In the present study, the internal consistency was 0.84.

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) [33] is a 26-item measure of self-compassion. The SCS consists of six subscales to assess self-compassion’s three components: self-kindness vs. self-judgment, common humanity vs. isolation, and mindfulness vs. over-identification. Responses are rated on a 6-point scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (6) strongly agree. To yield a total score, the scores on three negative dimensions are reversed coded and then obtain an average score of all the items. A higher score indicates a higher level of self-compassion.

The self-compassion scale has been validated in Chinese samples, demonstrating adequate reliability and validity [34]. In the present study, the internal consistency was 0.86.

Mental health continuum-short form

The short form of Mental Health Continuum measuring positive mental health (MHC-SF) [35] was used to tap into well-being. It consists of 14 items measuring the extent to which one had experienced a feeling of well-being in the previous month on three dimensions: emotional well-being, social well-being, and psychological well-being. Example item is “during the past month, how often did you feel Satisfied with life”. A higher score indicates greater level of well-being. In the present study, the internal consistency was 0.92.

SPSS 26.0 was used to perform the descriptive and preliminary analysis. To confirm the hypothesis, Andrew Hayes’s PROCESS for SPSS was employed using model one to test the moderation model [36]. The analysis was based on the specifications set out by PROCESS using 5,000 bootstrap simulations. The effects were significantly different from zero if zero was not contained in the 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval using 5,000 bootstrap samples.

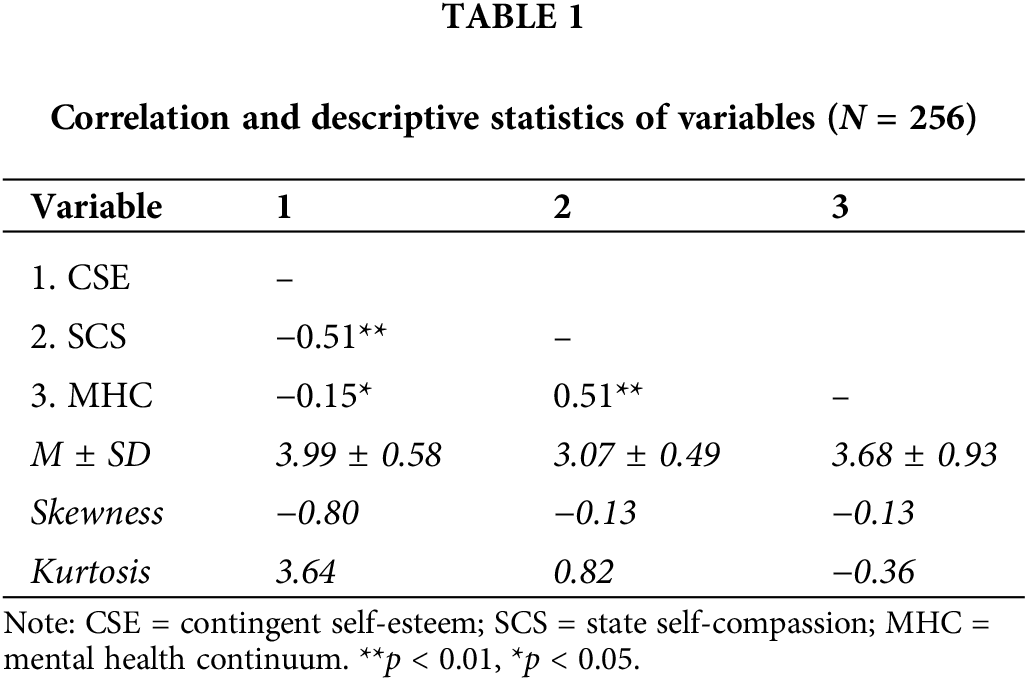

Correlations and descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among means of contingent self-esteem, self-compassion and mental health continuum. Self-compassion was correlated with contingent self-esteem negatively (r = −0.51, p < 0.01) and correlated with well-being measure positively (r = 0.51, p < 0.01) whereas contingent self-esteem had a modest negative correlation with well-being measure (r = −0.15, p < 0.05).

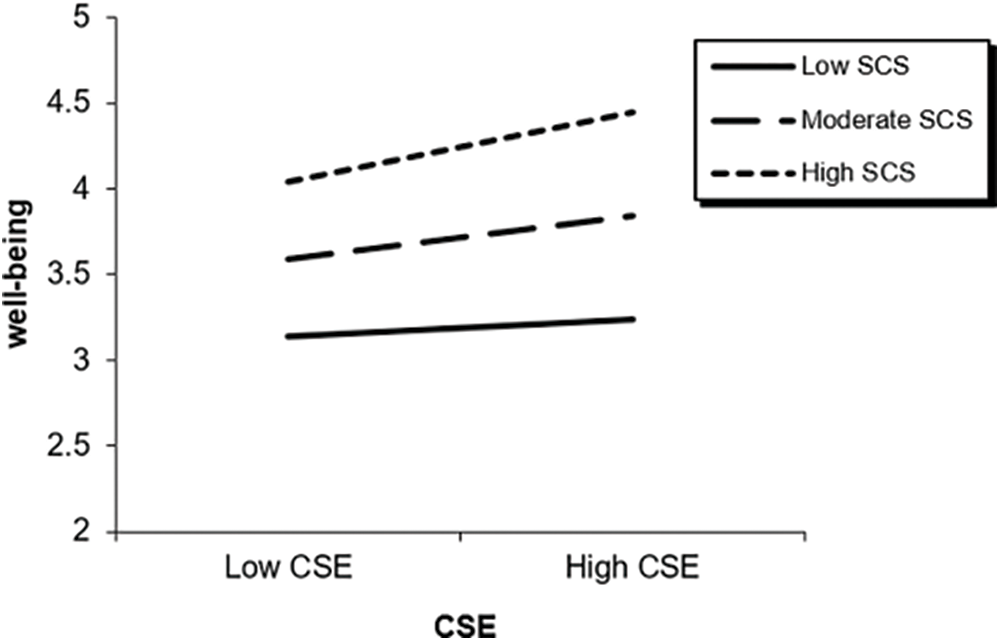

The moderation analyse was conducted using model one in PROCESS. Data analysis using 5,000 bootstrap simulations revealed a significant moderating role of self-compassion on the effect of contingent self-esteem on well-being, for the interaction term, ΔR2 = 0.01, ΔF = 5.17, p < 0.05. For individuals with low self-compassion (mean value = 2.65), the effect of contingent self-esteem on well-being was non-significant. For individuals with moderate self-compassion (mean value = 3.04), the effect of contingent self-esteem on well-being was significantly positive (effect = 0.21, SE = 0.10, p < 0.05 [95% CI 0.01, 0.41]). For individuals with high self-compassion (mean value = 3.54), the effect of contingent self-esteem on well-being was significantly positive as well (effect = 0.35, SE = 0.11, p < 0.01 [95% CI 0.13, 0.56]). Fig. 1 shows the interaction diagram between contingent self-esteem and self-compassion on well-being.

Figure 1: Interaction diagram between contingent self-esteem (CSE) and self-compassion (SCS) on well-being.

The results confirmed the hypothesis, showing that self-compassion could moderate the effect of contingent self-esteem on well-being. It is worth noting that the results revealed a strengthening positive effect of contingent self-esteem on well-being for individuals with higher self-compassion, instead of a decreased negative effect of contingent self-esteem on well-being.

Evidence shows that when failures or unsatisfactory outcomes threaten contingencies of self-worth, people may experience diminished self-esteem and respond defensively or maladaptively [2]. Contingent self-esteem may not be a good indicator to predict negative outcomes per se; rather, it is where, in a self-threatening situation, detrimental patterns emerge [37]. The link between contingent self-esteem and variables related to well-being might be more direct and stronger when encountering stressful events.

Study 2 adopted a social evaluative threat task to examine the influence of contingent self-esteem on the responses to such threats. The social evaluative threat task involved an awareness of social eyes, i.e., someone was watching the self, which was sufficient to evoke concern about potentially negative social evaluations held by others [38]. Chinese people are interdependently oriented and thus are likely to draw on social evaluations and be heavily influenced by such social evaluative threats [39].

The main purpose of Study 2 was to investigate whether baseline contingent self-esteem influenced affects in the face of a social stress task and to evaluate whether self-compassion served as a protective factor to maintain a positive self-regard, and to promote positive affects and reduce negative affects. The well-being measure in the situation was indicated by affects, which were reported immediately after the social stress task. Previous researchers argued that individuals’ emotional states were related to global well-being measures, initiating upward spirals toward emotional well-being [40]. As the measure was linked to actual events, it might reflect well-being in real-time with less filter of memory [41]. We proposed that self-compassion would moderate the effects of contingent self-esteem on the affects. Study 2 was guided by the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Self-compassion training would protect individuals from experiencing decreased self-worth facing social evaluative threats compared with the control group.

Hypothesis 2: Condition (whether people were in the self-compassion training group or in the control group) would moderate the effects of contingent self-esteem on affects. Specifically, for individuals in the self-compassion training group, their contingent self-esteem would lead to a higher level of positive affects/lower level of negative affects compared with the control group.

A pilot study was conducted before the main study to check the effectiveness of the self-compassion training. In the pilot study, fifty-eight undergraduates from a University in China were recruited and were randomly assigned to the self-compassion group (N = 28) and control group (N = 30). The results of Chi-square tests showed no significant differences between the two groups regarding the demographics, including age, gender, and study years. After listening to the 12-minute self-compassion audio or sitting calmly for 12 minutes, they were asked to complete the measurement of contingent self-esteem and state self-compassion (refer to the Measures below).

The t-test results showed a significantly higher level of self-compassion (M = 4.33, SD = 1.08) for the self-compassion group compared with the control group (M = 3.75, SD = 0.56), t = 2.47, df = 56, p < 0.05. There was no significant difference between the two groups on the measurement of contingent self-esteem (Mcontrol = 3.87, Msc = 3.97, t = 0.72, df = 56, p > 0.05). The results implied that self-compassion training was effective to induce self-compassion.

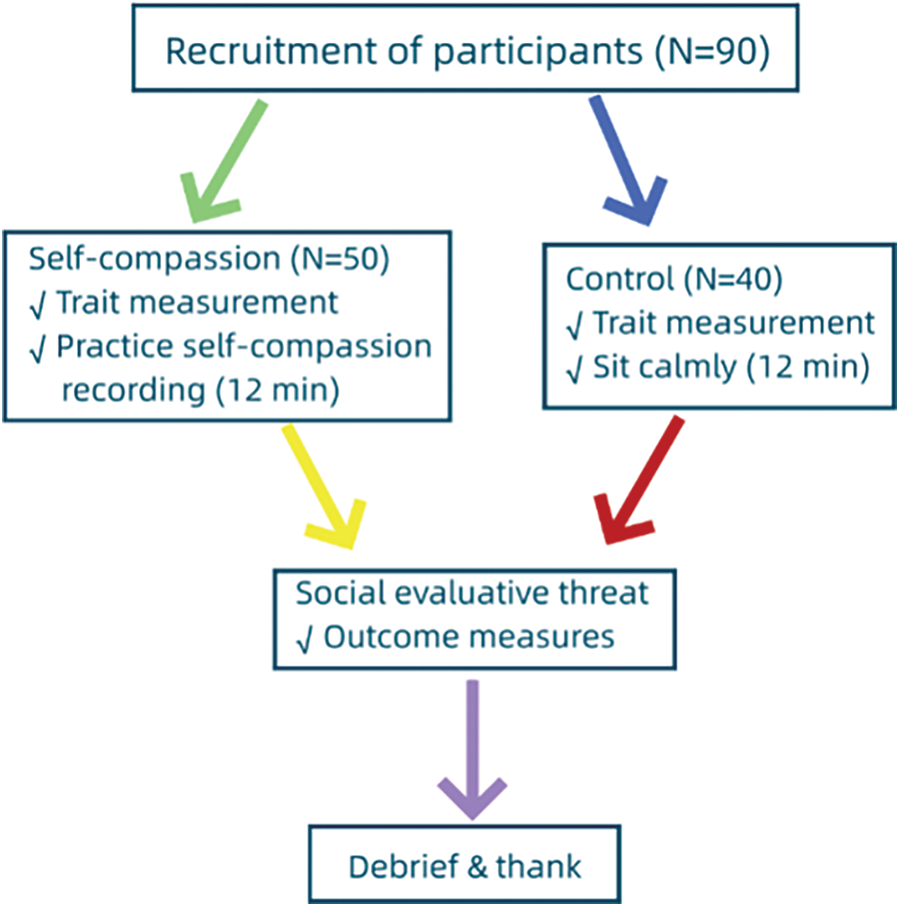

After obtaining ethics approval, 108 Chinese undergraduates were recruited for this study and were randomly assigned to two groups: a self-compassion training group and a control group. After deleting the participants whose data were missing, ultimately, 90 participants (40 for the control group and 50 for the self-compassion group) provided data for the study (34% male); their average age was 18.39 years (SD = 1.01).

Participants first provided informed consent and filled out baseline trait measures of contingent self-esteem and self-compassion. Afterward, participants were led to listen to either a self-compassion audio (for the self-compassion training group) or to have a break (for the control group). For the self-compassion training group, they listened to a self-compassion audio recording, which used visualization methods to cultivate self-compassion. For the control group they sit calmly with the same time length as the self-compassion training group, which was shown in previous studies to be effective as a control condition [42].

Participants did the social stress task after the 12-min audio practice or break, followed by outcome measures. Finally, participants completed demographic items and were then debriefed about the study’s purpose and thanked for their participation. Fig. 2 shows the flow of the whole procedure.

Figure 2: Flow of the whole procedure.

In line with the conceptualization of self-compassion, the audio used in the self-compassion training instructed listeners to visualize themselves, sending blessings and being compassionate to themselves with the cultivation of self-warmth and reduction of self-coldness. For example, “I wish I could accept and be kind to myself,” “suffering is a shared experience of all human beings,” and “If you find it is difficult, it’s OK. Just try to openly observe the feelings, thoughts, and body sensation in the present moment, without pushing yourself or criticizing yourself”. The audio began with instructions leading participants to close their eyes and take deep breaths several times. It also induced thinking of a stressful experience related to the self [43], observing the innate feelings and tension in the body and sending wishes to selves with a self-compassionate attitude.

The task of social evaluative threat was modified based on previous procedures of the Trier Social Stress Task (TSST) [44,45]. Participants were asked to imagine being interviewed for a “dream” job and to give a 2-min speech on why they felt they were qualified for this job. They were asked to deliver the speech in English and told that their performance would be recorded and evaluated by researchers. Participants had 1-min to prepare their speech. Then, participants delivered their 2-min speech through a microphone in front of the computer with the experimenter beside them. After the above procedure, the participants filled in the outcome measurements and were informed of the purpose of this experiment.

At the baseline, participants completed the measurements of contingent self-esteem and self-compassion, which were measured by the same scales used in Study 1, and the internal consistency of these scales in the present study was as follows: 0.82 for CSC and 87. for SCS.

After the social stress task, they filled in a set of questionnaires including affects (as dependent variables in hypothesis 2), state self-compassion (for manipulation check), and state self-esteem (as the dependent variable in hypothesis 1).

The affects were measured by the 20-item Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) [46]. It was rated on a 7-point scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. The internal consistency was as follows: 0.92 for positive affects, 0.91 for negative affects.

The 16-item state self-compassion scale [47] taps current compassionate feelings or attitudes towards the self. It was rated on a 6-point scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (6) strongly agree. A higher score indicated a higher level of state self-compassion. The internal consistency in the current study was 0.82.

The 20-item State Self-Esteem scale (SSES) [48] measures momentary fluctuations of self-esteem, which is sensitive to laboratory manipulations. It was rated on a 6-point scale from (1) not at all to (6) extremely; an example item was “I feel confident about my abilities.” The internal consistency was 0.85.

SPSS 26.0 was used to perform the descriptive statistics of the variables and preliminary analysis. Then Chi-square and one-way between-group ANOVA was conducted to compare the demographics differences as well as the baseline differences between two groups. In order to determine if the self-compassion training protected individuals from experiencing decreased self-worth (hypothesis 1), one-way ANOVA was performed to compare the group difference on state self-esteem.

To confirm hypothesis 2, Andrew Hayes’s PROCESS for SPSS was employed using model one to test the moderation model [36]. The analysis was based on the specifications set out by PROCESS using 5,000 bootstrap simulations. The effects were significantly different from zero if zero was not contained in the 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval using 5,000 bootstrap samples.

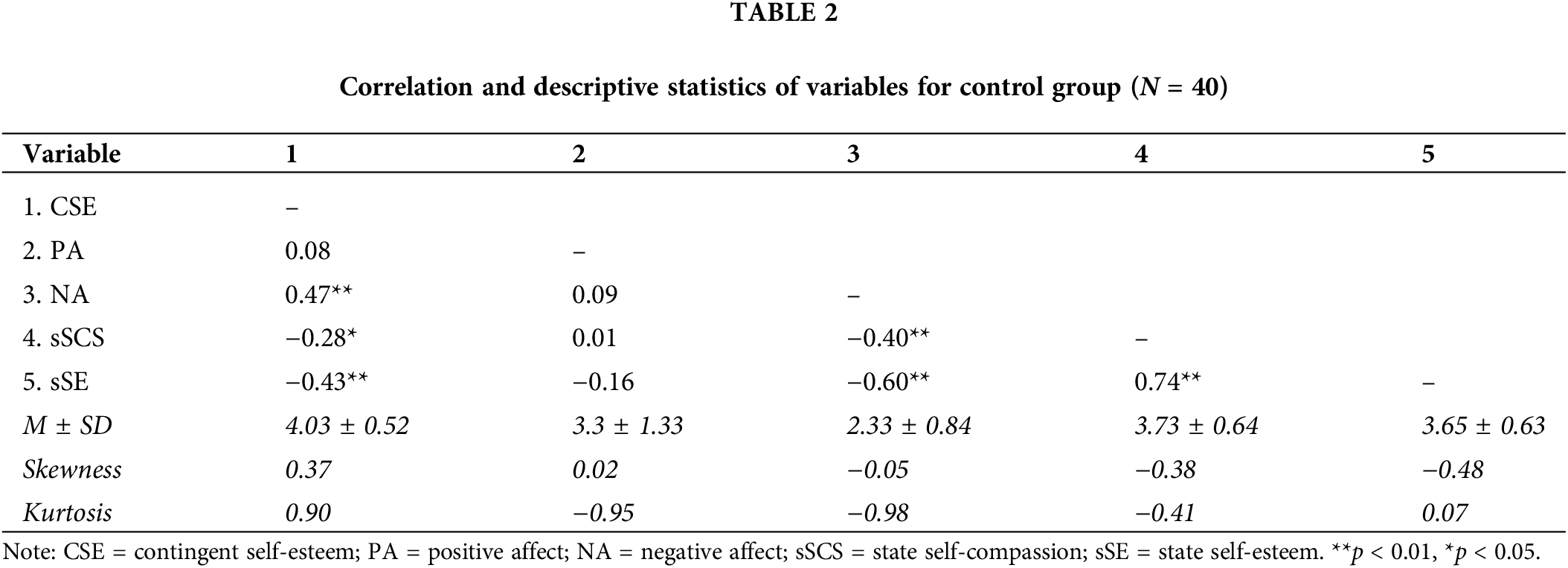

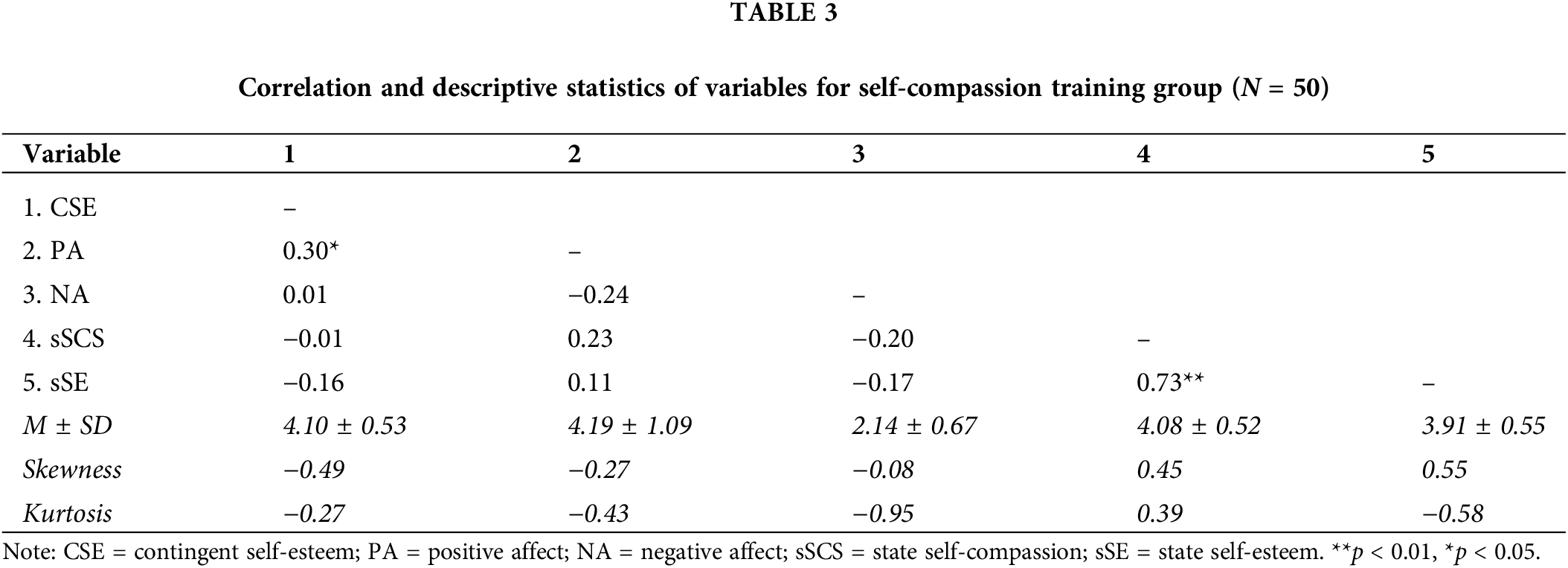

Correlations and descriptive statistics

Tables 2 and 3 present the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among means of contingent self-esteem, positive affect, negative affect, state self-compassion and state self-esteem for the control group and self-compassion training group. For the control group, baseline contingent self-esteem had a moderate positive correlation with negative affect (r = 0.47, p < 0.01) as well as a moderate negative correlation with state self-compassion (r = −0.28, p < 0.05) and state self-esteem (r = −0.44, p < 0.01), suggesting that contingent self-esteem had costs on responses to threatening situations; For the self-compassion training group, the costs of contingent self-esteem on negative affect and state self-compassion were buffered with non-significant associations between contingent self-esteem and these variables, instead, baseline contingent self-esteem had a positive correlation with positive affects (r = 0.30, p < 0.05). The above findings suggested that in a situation with self-evaluative threat, those with high contingent self-esteem experienced greater negative affect, less state self-compassion and diminished state self-esteem whereas self-compassion training seemed to buffer the costs of contingent self-esteem on negative affect, state self-compassion and state self-esteem.

Chi-square tests were conducted and no significant differences existed between the self-compassion training group and the control group regarding the demographics information, including gender, age, and study years. The t-test results showed the means of the two groups on the baseline measurement of contingent self-esteem (Mcontrol = 4.03, Msc = 4.10, t = −0.66, df = 88, p > 0.05), self-compassion (Mcontrol = 3.13, Msc = 3.06, t = 0.66, df = 88, p > 0.05) and self-esteem (Mcontrol = 4.21, Msc = 4.42, t = −1.32, df = 88, p > 0.05) were also non-significantly different.

For the manipulation check, the results of one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the control condition and self-compassion condition on state self-compassion (Mcontrol = 3.73, Msc = 4.08, F (1.88) = 8.25, p < 0.01), showing that self-compassion training was effective in inducing self-compassionate mindset under social evaluative threat. To test hypothesis 1, one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between the control condition and self-compassion condition on state self-esteem (F (1.88) = 4.16, p < 0.05)). The findings suggested that the self-compassion training group (M = 3.91, SD = 0.55) reported a higher level of state self-esteem in the face of a social evaluative threat compared with the control group (M = 3.65, SD = 0.63); therefore hypothesis 1 was confirmed.

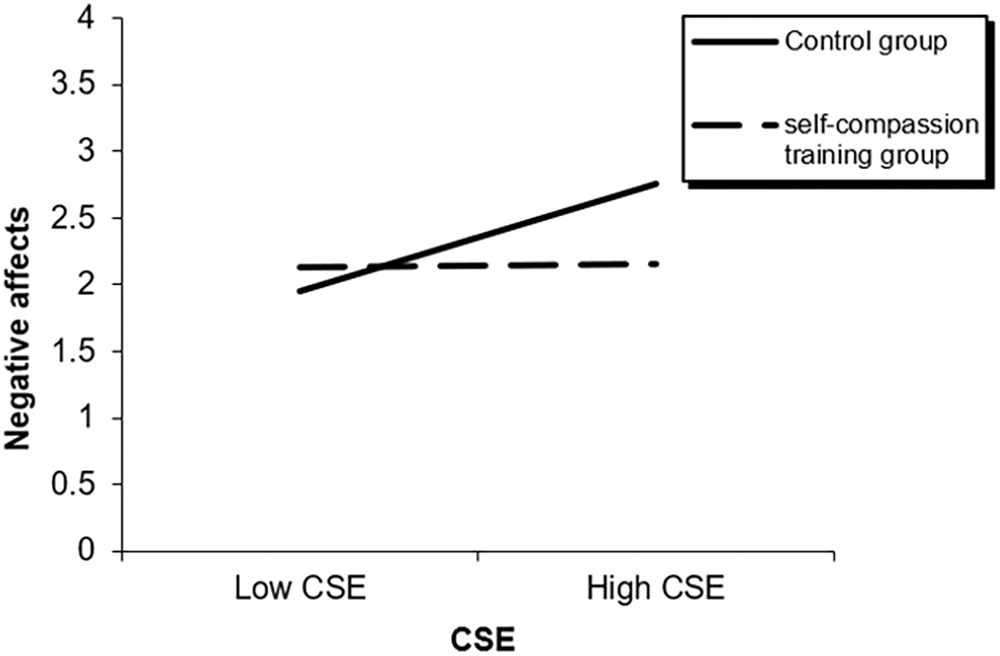

The moderation analyses was conducted using model one in PROCESS. Data analysis using 5,000 bootstrap simulations revealed a significant moderating role of condition on the effect of contingent self-esteem on negative affect, for the interaction term, ΔR2 = 0.07, ΔF = 6.69, p < 0.05. For individuals in the control condition, the effect of contingent self-esteem on negative affect was significantly positive (effect = 0.76, SE = 0.22, p < 0.01 [95% CI 0.33, 1.20]). For individuals in the self-compassion condition, the effect of contingent self-esteem on negative affect was non-significant. The results suggested that contingent self-esteem led to increased negative affects under social evaluative threats only among people in the control group while people who went through self-compassion training in advance did not experience diminution of negative affects. However, the moderating role of condition on the relationship between contingent self-esteem and positive affects was non-significant. Fig. 3 shows the interaction diagrams between contingent self-esteem and condition on negative affects.

Figure 3: Interaction diagram between contingent self-esteem (CSE) and condition on negative affects.

Taken as a whole, these findings showed a significant result that the self-compassion training group reported higher levels of state self-esteem facing social evaluative threat compared with the control group; The effect of contingent self-esteem on negative affects in a threatening situation was moderated by the condition such that self-compassion training buffered the negative effects of contingent self-esteem on responses to a social evaluative negative threat.

The results showed that self-compassion, either as a stable personality characteristic (Study 1), or as an active coping strategy (Study 1) exhibited a protective effect on the relation between contingent self-esteem and well-being. Contingent self-esteem may be associated with the problematic process of self-evaluation, especially navigating stressful life events. Our findings suggested that self-compassion, which is associated with the feelings of self-acceptance and self-kindness, alleviates the feelings of suffering, and contributes to a realistic, unbiased self-view and enhanced well-being. Self-compassion might provide a perspective to step back, observe, and embrace feelings with humility and balanced awareness. Therefore, in the self-compassion context, the threatening information in daily life loses its self-threatening capacity, enabling one to possess goals beyond ego protection with a sense of equanimity and a balanced reaction to suffering.

It is worth noting that in Study 1, contingent self-esteem had a modest negative correlation with well-being, and self-compassion serves as a booster to enhance the positive effects of contingent self-esteem on well-being, instead of a buffer against the negative effects of contingent self-esteem on well-being. Given the research was conducted among Chinese participants whose self emphasizes relatedness and interdependence (i.e., the self as interdependent is dominant) [39,49], it is likely that Chinese individuals intend to include the needs and expectations of social others in their own functioning [50] and the process of socialization (culture, society, family) as well as the reinforcement history influenced the development and display of contingent self-esteem [2]. Therefore, the meaning of contingent self-esteem varies depending on the cultural context and the functioning of contingent self-esteem in the Chinese context may be different from what is shown in Western cultures. Culture and environment may help to reframe the issue of contingency and determine whether contingent self-esteem is associated with psychological consequences, or it may bring benefits (e.g., contribute to social adaptation), depending on the salience of different self-construal.

Study 2 induced self-compassion successfully through a brief self-compassion training in an experimental setting and showed that self-compassion led to more adaptive responses and buffered the increased negative affects associated with contingent self-esteem under a social evaluative threat. Individuals’ reactions to self-threatening events should be more intense with contingent self-esteem [51]. However, for those in a self-compassionate context, contingent self-esteem did not drive them to respond to the social evaluative threat with decreased self-worth and increased negative affects, as in the control group. Contingent self-esteem coupled with frustration or shame may arise when encountering threats towards the self. In contrast, self-compassion intervention cultivates a non-judgmental attitude towards the self and emphasizes the feeling of compassion and caring towards oneself with stable self-acceptance, regardless of whether one’s performance matches their anticipation. The findings suggested that inducing a self-compassionate mindset in advance, people were propelled to confront negative life events head-on, thus maintaining emotional equanimity. Contrary to our expectation, the moderating role of condition on the relationship between contingent self-esteem and positive affects was non-significant. It may be because of the measures of positive affects consisting of “excited”, “enthusiastic”, “active”, etc., which may not be sensitive enough to reflect the effect of the self-compassion intervention.

The present work provided both cross-sectional and experimental evidence demonstrating a significant interaction relationship between contingent self-esteem and self-compassion. The findings have several implications for theory and practice. First, the results advance our appreciation of the significant role self-compassion plays in the psychological resilience of individuals with high contingent self-esteem facing threats towards the self, implying self-compassion can be a resilience mechanism that accounts for the association between contingent self-esteem and well-being, which adds to the growing body of evidence of the beneficial role of self-compassion on mental health [52,53]. Second, they support the notion that regardless of the possibly different functioning of contingent self-esteem in Chinese society, self-compassion is a beneficial way of relating to oneself and an important personal capacity for maintaining self-esteem stability [54], supporting the prior argument that self-compassion was a secure and positive element of “optimal self-esteem” [6,12,55–57]. The results also provide insights into how to develop “optimal self-esteem” that is secure and authentic rather than fragile and dependent on external validation.

In terms of clinical implications, the findings support that self-compassion can be cultivated through brief interventions and can lower the risk of the impairment of negative emotions induced by a fragile sense of self-worth in self-threatening situations, which may bolster improved well-being in the long run. For practitioners, such as counselors, educators, or coaches, this study adds to the evidence of the benefits of practicing self-compassion [58] and offers some suggestions for helping individuals who struggle with contingent self-worth. One suggestion is to foster a self-compassionate mindset that can help them cope with failure, criticism, or rejection without losing their sense of self-worth. Another suggestion is to implement self-compassion training programs that can increase their resilience and positive emotions in the face of social stressors. By cultivating self-compassion, individuals can achieve greater psychological well-being and optimal self-esteem.

Limitations and future research suggestions

The current research has some limitations. Firstly, the samples were Chinese undergraduate students, which restricted the generalizability of the research findings to other populations in various cultures. Future studies are expected to be conducted among various populations. Secondly, the mechanisms of how self-compassion functions and facilitates the alleviation of suffering are unclear; future studies are encouraged to explore the underlying mechanisms of self-compassion’s improvement on inner happiness [59].

As culture plays a significant role in shaping an ideal self, it should also be interesting to understand contingent self-esteem and self-compassion in particular cultural contexts. Future cross-cultural research on contingent self-esteem and self-compassion shall deepen the understanding of “optimal self-esteem” in various cultures. According to Crocker and Wolfe [2], due to various social influences, people are more likely to develop contingencies valued or rewarded by society over time. In addition, it will be helpful for future work to identify the cultural factors that may account for the difference regarding the meaning of contingent self-esteem. For example, relational interdependent self-construal, given that the salience of relational interdependence in Chinese culture might facilitate the internalization of expectations or requirements of external environments [60,61], contingent self-esteem could possibly bring benefits for Chinese people with a compassionate mindset.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the participants who participated this study.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Jilin Science and Technology Department 20200201280JC, and Shanghai special fund for ideological and political work in Shanghai University of International Business and Economics.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study design and administration: RZ and HZ; analysis and interpretation of results: RZ and XZ; draft manuscript preparation: HZ and XZ; writing-review and editing: HZ and MY. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data can be obtained by contacting the authors.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards and guidelines of the institutional research committee. All participants provided informed consent in the research.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Human autonomy. In: Kernis MH, editor. Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem. New York, USA: Springer; 1995. p. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

2. Crocker J, Wolfe CT. Contingencies of self-worth. Psychol Rev. 2001;108(3):593–607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Kernis MH. Toward a conceptualization of optimal self-esteem. Psychol Inq. 2003;14(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

4. Kärchner H, Schöne C, Schwinger M. Beyond level of self-esteem: exploring the interplay of level, stability, and contingency of self-esteem, mediating factors, and academic achievement. Soc Psychol Educ. 2021;24(2):319–41. [Google Scholar]

5. Kernis MH, Goldman BM. A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: theory and research. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2006;38:283–357. [Google Scholar]

6. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The what and” why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11(4):227–68. [Google Scholar]

7. Kang Y. The relationship between contingent self-esteem and trait self-esteem. Soc Behav Pers: An Int J. 2019;47(2):1–19. [Google Scholar]

8. Neff KD. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;2(2):85–101. [Google Scholar]

9. Crocker J, Park LE. The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):392–409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M, Tice DM. Ego depletion: is the active self a limited resource? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(5):1252–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Gilbert P, Procter S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2006;13(6):353–62. [Google Scholar]

12. Neff KD, Rude SS, Kirkpatrick KL. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. J Res Pers. 2007;41(4):908–16. [Google Scholar]

13. Neff KD, Vonk R. Self-compassion vs. global self-esteem: two different ways of relating to oneself. J Pers. 2009;77(1):23–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Muris P, Otgaar H. Self-esteem and self-compassion: a narrative review and meta-analysis on their links to psychological problems and well-being. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:2961–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Neff KD. The science of self-compassion. In: Germer C, Siegel R, editors Compassion and wisdom in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. p. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

16. Leary MR, Tate EB, Adams CE, Batts Allen A, Hancock J. Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: the implications of treating oneself kindly. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(5):887–903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Allen AB, Leary MR. Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2010;4(2):107–18. [Google Scholar]

18. Neff KD, Hsieh YP, Dejitterat K. Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self Identity. 2005;4(3):263–87. [Google Scholar]

19. Sajjadi M, Noferesti A, Abbasi M. Mindful self-compassion intervention among young adults with a history of childhood maltreatment: reducing psychopathological symptoms, shame, and self-criticism. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(30):26227–37. [Google Scholar]

20. Crego A, Yela JR, Riesco-Matías P, Gómez-Martínez MA, Vicente-Arruebarrena A. The benefits of self-compassion in mental health professionals: a systematic review of empirical research. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:2599–620. [Google Scholar]

21. McEwan K, Elander J, Gilbert P. Evaluation of a web-based self-compassion intervention to reduce student assessment anxiety. Interdiscip Educ Psychol. 2018;2(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

22. Krieger T, Reber F, von Glutz B, Urech A, Moser CT, Schulz A, et al. An internet-based compassion-focused intervention for increased self-criticism: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2019;50(2):430–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Hammad SS, Alzhrani MD, Almulla HA. Adolescents’ perceived stress of COVID-19 and self-compassion in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2023;10(2):215–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Chong ES, Chan RC. The role of self-compassion in minority stress processes and life satisfaction among sexual minorities in Hong Kong. Mindfulness. 2023;14(4):784–96. [Google Scholar]

25. Homan KJ, Tylka TL. Self-compassion moderates body comparison and appearance self-worth’s inverse relationships with body appreciation. Body Image. 2015;15:1–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Crocker J, Brook AT, Niiya Y, Villacorta M. The pursuit of self-esteem: contingencies of self-worth and self-regulation. J Pers. 2006;74(6):1749–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

27. Terry ML, Leary MR. Self-compassion, self-regulation, and health. Self Identity. 2011;10(3):352–62. [Google Scholar]

28. Germer CK. The mindful path to self-compassion: freeing yourself from destructive thoughts and emotions. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

29. Werner KH, Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Ziv M, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Self-compassion and social anxiety disorder. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2012;25(5):543–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

30. Brislin RW. Back translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216. [Google Scholar]

31. Paradise AW, Kernis MH. Development of the contingent self-esteem scale. Unpublished data, University of Georgia. 1999. [Google Scholar]

32. Kernis MH, Paradise AW, Whitaker DJ, Wheatman SR, Goldman BN. Master of one’s psychological domain? Not likely if one’s self-esteem is unstable. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2000;26(10):1297–305. [Google Scholar]

33. Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2(3):223–50. [Google Scholar]

34. Chen J, Yan L, Zhou L. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Self-compassion Scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2011;19(6):734–6. [Google Scholar]

35. Keyes CL, Wissing M, Potgieter JP, Temane M, Kruger A, van Rooy S. Evaluation of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF) in setswana-speaking South Africans. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2008;15(3):181–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

37. Dibello AM, Rodriguez LM, Hadden BW, Neighbors C. The green eyed monster in the bottle: relationship contingent self-esteem, romantic jealousy, and alcohol-related problems. Addict Behav. 2015;49(2):52–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

38. Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):355–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

39. Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98(2):224–50. [Google Scholar]

40. Fredrickson BL, Joiner T. Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychol Sci. 2002;13(2):172–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

41. Kahneman D, Krueger AB. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20(1):3–24. [Google Scholar]

42. Diedrich A, Gran M, Hofmann SG, Hiller W, Berking M. Self-compassion as an emotion regulation strategy in major depressive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2014;58:43–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

43. Shapira LB, Mongrain M. The benefits of self-compassion and optimism exercises for individuals vulnerable to depression. J Posit Psychol. 2010;5(5):377–89. [Google Scholar]

44. Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiol. 1993;28(1–2):76–81. [Google Scholar]

45. Eagle DE, Rash JA, Tice L, Proeschold-Bell RJ. Evaluation of a remote, internet-delivered version of the trier social stress test. Int J Psychophysiol. 2021;165(2):137–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

46. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

47. Breines JG, Chen S. Activating the inner caregiver: the role of support-giving schemas in increasing state self-compassion. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2013;49(1):58–64. [Google Scholar]

48. Heatherton TF, Polivy J. Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60(6):895–905. [Google Scholar]

49. Bedford O, Huang YHC, Ito K. An assessment of the relational orientation framework for Chinese societies: scale development and Chinese relationalism. PsyCh J. 2021;10(1):112–27. doi:10.1002/pchj.403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Hwang KK. Chinese relationalism: theoretical construction and methodological considerations. J Theory Soc Behav. 2000;30(2):155–78. [Google Scholar]

51. Crocker J. The costs of seeking self-esteem. J Soc Issues. 2002;58(3):597–615. [Google Scholar]

52. Neff KD. Self-compassion: theory, method, research, and intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2023;74(1):193–218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

53. Zipagan FB, Galvez Tan LJT. From self-compassion to life satisfaction: examining the mediating effects of self-acceptance and meaning in life. Mindfulness. 2023;14(9):2145–54. [Google Scholar]

54. Holas P, Kowalczyk M, Krejtz I, Wisiecka K, Jankowski T. The relationship between self-esteem and self-compassion in socially anxious. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(12):10271–6. [Google Scholar]

55. Barry CT, Loflin DC, Doucette H. Adolescent self-compassion: associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males. Pers Individ Diff. 2015;77:118–23. [Google Scholar]

56. Miyagawa Y. Self-compassion promotes self-concept clarity and self-change in response to negative events. J Pers. 2023. doi:10.1111/jopy.12885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Miyagawa Y, Kanemasa Y, Taniguchi J. A compassionate and worthy self: latent profiles of self-compassion and self-esteem in relation to intrapersonal and interpersonal functioning. Curr Psychol. 2023;1–14. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-05428-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Foerster K, Kanske P. Exploiting the plasticity of compassion to improve psychotherapy. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2021;39:64–71. [Google Scholar]

59. Bluth K, Neff KD. New frontiers in understanding the benefits of self-compassion. Self Identity. 2018;17(6):605–8. [Google Scholar]

60. Cross SE, Bacon PL, Morris ML. The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(4):791–810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

61. Wang ZD, Wang YM, Guo H, Zhang Q. Unity of heaven and humanity: mediating role of the relational-interdependent self in the relationship between Confucian values and holistic thinking. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1–11. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools