Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: The Role of Self-Esteem and Attachments in Early Adolescent Body-Esteem

Department of Child and Family Counseling, Gukje Cyber University, Gyeonggi-do, 16487, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Young Mi Kim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mental Health Promotion and Psychosocial Support in Vulnerable Populations: Challenges, Strategies and Interventions)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(12), 1017-1024. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.057597

Received 22 August 2024; Accepted 29 October 2024; Issue published 31 December 2024

Abstract

Background: Early adolescents become increasingly conscious of their body image, which can profoundly impact their mental health and well-being. In South Korea, societal pressures and expectations regarding physical appearance are particularly intense, making the study of body-esteem in Korean adolescents especially pertinent. This study explores the roles of self-esteem, peer attachment, and maternal attachments in shaping body-esteem among early adolescents. Methods: Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed using data from 1326 Korean middle school students (Meanage = 13.32, SD = 1.73). Results: The results revealed that self-esteem had a significantly positive effect on both peer attachment and maternal attachment. However, while peer attachment positively influenced body-esteem, maternal attachment did not have a significant direnct effect on body-esteem. Conclusions: These findings suggest that during early adolescence, peer relationships, rather than maternal bonds, play a more critical role in shaping body image. In a culture that emphasizes peer validation and societal beauty standards, peer relationships have a stronger impact on body-esteem. Interventions should focus on fostering supportive peer environments and enhancing self-esteem to promote positive body-esteem and mental health among adolescents.Keywords

Early adolescence, typically between the ages of 10 and 14, represents a transformative period characterized by significant changes in physical, psychological, and social domains [1]. During this stage, peer relationships, social comparisons, and physical appearance become increasingly influential, shaping adolescents’ self-worth and social identity [2]. With the onset of secondary sexual characteristics and increased self-awareness, adolescents often find themselves comparing their bodies to societal standards, which can critically impact their body image [3]. The development of a positive body image during these changes is crucial for fostering confidence, social competence, and emotional resilience, all of which contribute to healthy self-development [4,5].

Body-esteem, a specific facet of self-esteem, refers to how individuals evaluate and feel about their physical appearance, including body shape, size, and overall physical self [6]. While self-esteem is a broader concept encompassing overall self-worth, body-esteem focuses specifically on perceptions related to one’s physical appearance. Although these two constructs are interconnected, they operate within distinct domains: while self-esteem influences general life outlook and self-worth, body-esteem is centered narrowly on physical appearance [7,8]. This distinction is critical in understanding how negative body-esteem can lead to withdrawn social behavior, while positive body-esteem enhances confidence and proactive social interactions [4,9].

In South Korea, societal pressures surrounding physical appearance are particularly intense. Despite having the lowest average body weight among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, Korean adolescents report the highest levels of desire to lose weight [10]. A 2023 survey revealed that over half of the adolescents perceived themselves as overweight, despite much lower actual obesity rates [11]. This misperception often leads to extreme weight control behaviors and can exacerbate mental health issues related to body dissatisfaction. Sociocultural influences, particularly media portrayal of thinness as an ideal, further contribute to negative body-esteem among adolescents striving to meet these unrealistic standards [12–14].

Adolescents’ self-esteem is a fundamental factor in their psychological well-being and overall development [15]. Research consistently shows that higher levels of self-esteem are closely linked to more positive body-esteem and enhanced emotional resilience, both of which contribute to a lower risk of mental health challenges, such as depression and anxiety [16,17]. In contrast, low self-esteem is frequently tied to dissatisfaction with one’s body, potentially leading to eating disorders and other psychological difficulties [18]. Notably, the relationship between self-esteem and body-esteem is particularly strong during adolescence, as this period is marked by heightened concern with physical appearance [19,20].

Harter emphasized that self-esteem results from the interplay between global self-worth and domain-specific evaluations, such as perceptions of physical appearance [21]. Studies have consistently shown a correlation between global self-worth and physical appearance evaluations throughout life, particularly during adolescence when body image concerns peak [8,9,20]. During early adolescence, self-esteem tends to decline while body image concerns increase, making this a critical period for interventions aimed at promoting positive self-perceptions [15,22]. Understanding how self-esteem influences body-esteem and the mediating role of social attachments provides key insights into adolescent development.

Secure attachments with both peers and caregivers can buffer the negative effects of low self-esteem on body-esteem. According to attachment theory, early interactions with caregivers shape an internal working model that influences an individual’s self-worth and body image perceptions [23]. Adolescents with strong attachments to both their mothers and peers tend to have more positive body-esteem, as these relationships provide emotional support and validation [24,25]. On the other hand, insecure attachments can exacerbate body dissatisfaction and negative self-perceptions [26,27]. Therefore, examining the distinct roles that peer and maternal attachments play in mediating the relationship between self-esteem and body-esteem is critical for understanding adolescent mental health outcomes [28,29].

Although the importance of parental and peer attachments in adolescent psychological health is well-acknowledged, there remains mixed evidence regarding their relative significance [30,31]. Some research emphasizes the equal importance of peer and parental relationships for adolescent psychological health [31,32], while other studies suggest that parental influence continues to be predominant [33]. During early adolescence, as individuals seek acceptance and validation from peers, peer attachment becomes increasingly important. However, maternal attachment remains vital for emotional and social development [34]. Therefore, exploring the unique contributions of maternal and peer attachments is essential for understanding their roles in shaping both self-esteem and body-esteem.

This research focuses on exploring the complex interplay between self-esteem, maternal attachment, peer attachment, and body-esteem during early adolescence. By examining both the direct and indirect influences of self-esteem on body-esteem, as mediated by social attachments, the study seeks to deepen the understanding of factors that contribute to the formation of a positive body image during this critical stage of identity development. The primary research questions are: (1) How does self-esteem affect body-esteem in early adolescence? (2) How do maternal and peer attachments serve as mediators in the relationship between self-esteem and body-esteem?

This study used data from the 14th wave of the Panel Study on Korean children (PSKC), a longitudinal cohort study administered by the Korea Institute of Child Care and Education (KICCE). Initiated in 2008, the PSKC aims to track the developmental trajectories of Korean children from birth, focusing on their health, cognitive and socio-emotional development, and family dynamics. The nationally representative panel provides valuable insights into the growth and development of children across various life stages. Data for the 14th wave, collected in 2022, included 1326 adolescents (677 boys, 649 girls) excluding 824 adolescents who did not respond to all surveys. The participants’ mean age was 13.32 years (SD = 1.73) with 624 (47.0%) being first-born children. The majority resided in medium-sized cities (601%, 45.3%), followed by large cities (470%, 35.4%). The average Body Mass Index (BMI) of participants was 21.00 (SD = 3.66), with a range from 12.00 to 37.00. Additionally, 846 (63.7%) adolescents had begun experiencing secondary sexual characteristics. The PSKC data are publicly available as open-access for research purposes, and no special permission is required to use these data.

Adolescents’ self-esteem was evaluated using a shortened version of Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale, derived from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) data [35]. The scale consists of 5 items, and responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). An example item includes, “I feel that I have a number of good qualities.” Higher scores reflect greater levels of self-esteem. Data were collected through self-report questionnaires as part of the PSKC’s 14th wave. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.861.

Peer attachment was assessed using selected sub-factors from the Parent and Peer Attachment Scale by Armsden and Greenberg [36]. Specifically, 9 items assessing communication and trust between peers were used. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). An example item includes, “My friends listen to what I have to say.” Higher scores indicate stronger peer communication or trust. Data were collected through self-administered surveys conducted as part of the PSKC. Cronbach’s alpha for communication was 0.701, for trust 0.759, and the overall reliability was 0.845.

Maternal attachment was also measured using subscales from the Parent and Peer Attachment Scale [36], focusing on communication and trust. This scale included 12 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). An example item includes, “My mother respects my feelings.” Higher scores denote stronger maternal communication or trust. Data were collected through self-administered surveys conducted as part of the PSKC. Cronbach’s alpha for communication was 0.903, for trust 0.780, and the overall reliability was 0.903.

Body-esteem was assessed using 4 items from the revised Body-Esteem Scale developed by Mendelson and White [37], focusing on appearance and body satisfaction. Adolescents rated the items on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). An example item includes, “I feel satisfied with my body.” Higher scores indicate greater body satisfaction. Data for body-esteem were obtained from self-reported questionnaires collected as part of the PSKC. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.707.

For statistical analysis, SPSS Version 26.0 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA) was used for preliminary descriptive statistics, and AMOS 26.0 software (IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA) was employed for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). CFA validated the measurement model, ensuring that the latent constructs aligned with the observed data based on theoretical expectations. This process provided a statistical test of the model’s adequacy. Subsequently, SEM was applied to test the theoretical model, evaluating both direct and indirect effects among variables. SEM’s flexibility in modeling complex relationships between latent and observed variables makes it ideal for analyzing mediation effects and multiple pathways within a theoretical framework [38].

Model fit was assessed using several widely accepted fit indices: Chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom (χ2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The χ2/df ratio was used to compare the observed and expected data, with a value of 5 or less indicating an acceptable fit. CFI and TLI are incremental fit indices, with values greater than 0.90 suggesting that the model fits the data well compared to a null model. RMSEA evaluates the error of approximation in the model, with values below 0.06 indicating a good fit [39–41].

To assess the mediating effects of social attachments on the relationship between self-esteem and body-esteems, bootstrap sampling was conducted with 2000 iterations using the Panton variables. Bootstrap methods provide a robust estimate of mediation effects, particularly when normality assumptions are not met. Confidence intervals were set at a 95% level of significance [42].

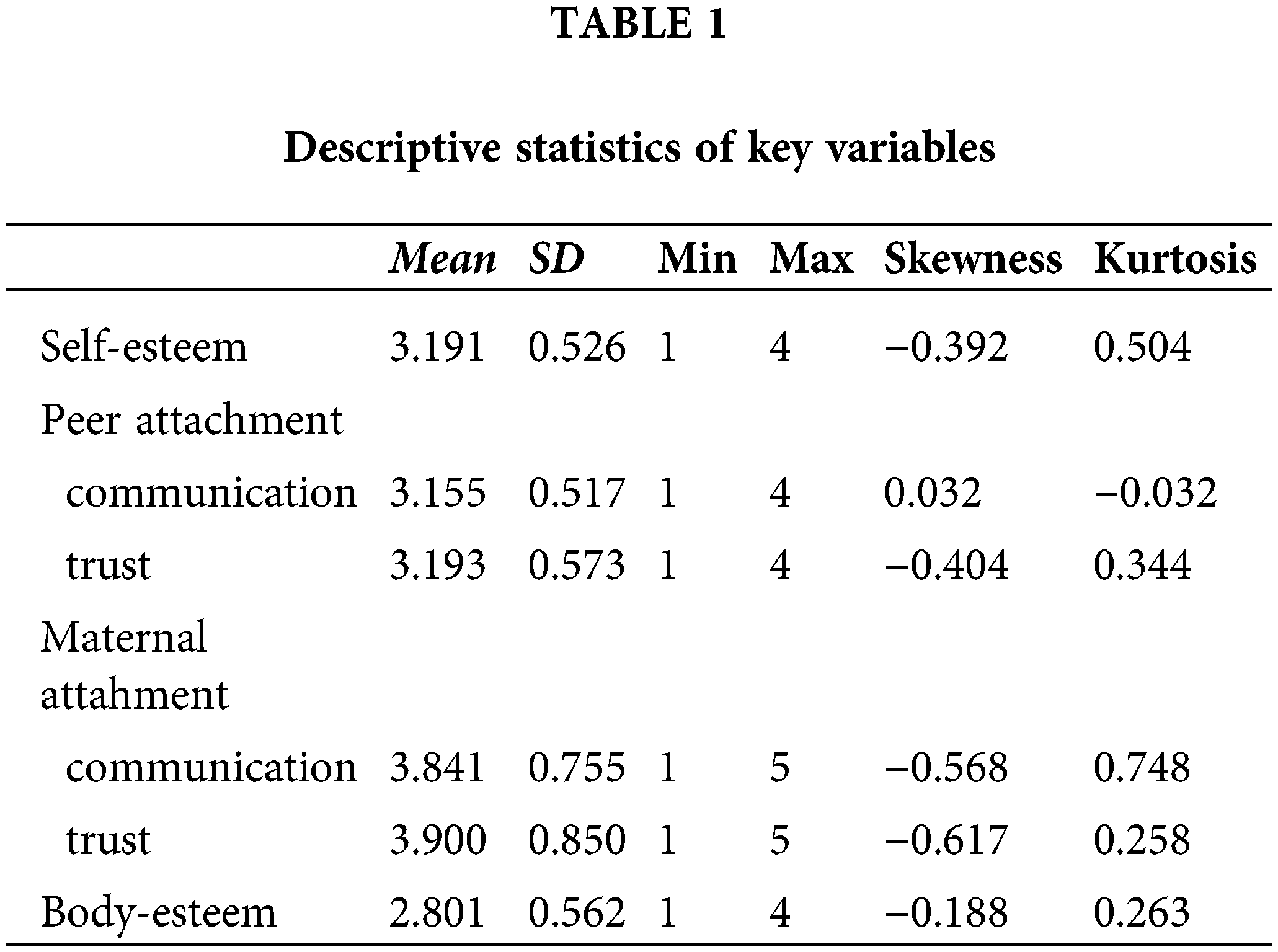

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, skewness, and kurtosis. The mean values ranged from 1.811 to 3.318, with standard deviations between 0.431 and 0.555. For all variables, the minimum value recorded was 1, and the maximum was 4. Furthermore, skewness and kurtosis values fell within the acceptable range of −2 to +2, indicating that the data met the assumption of normality.

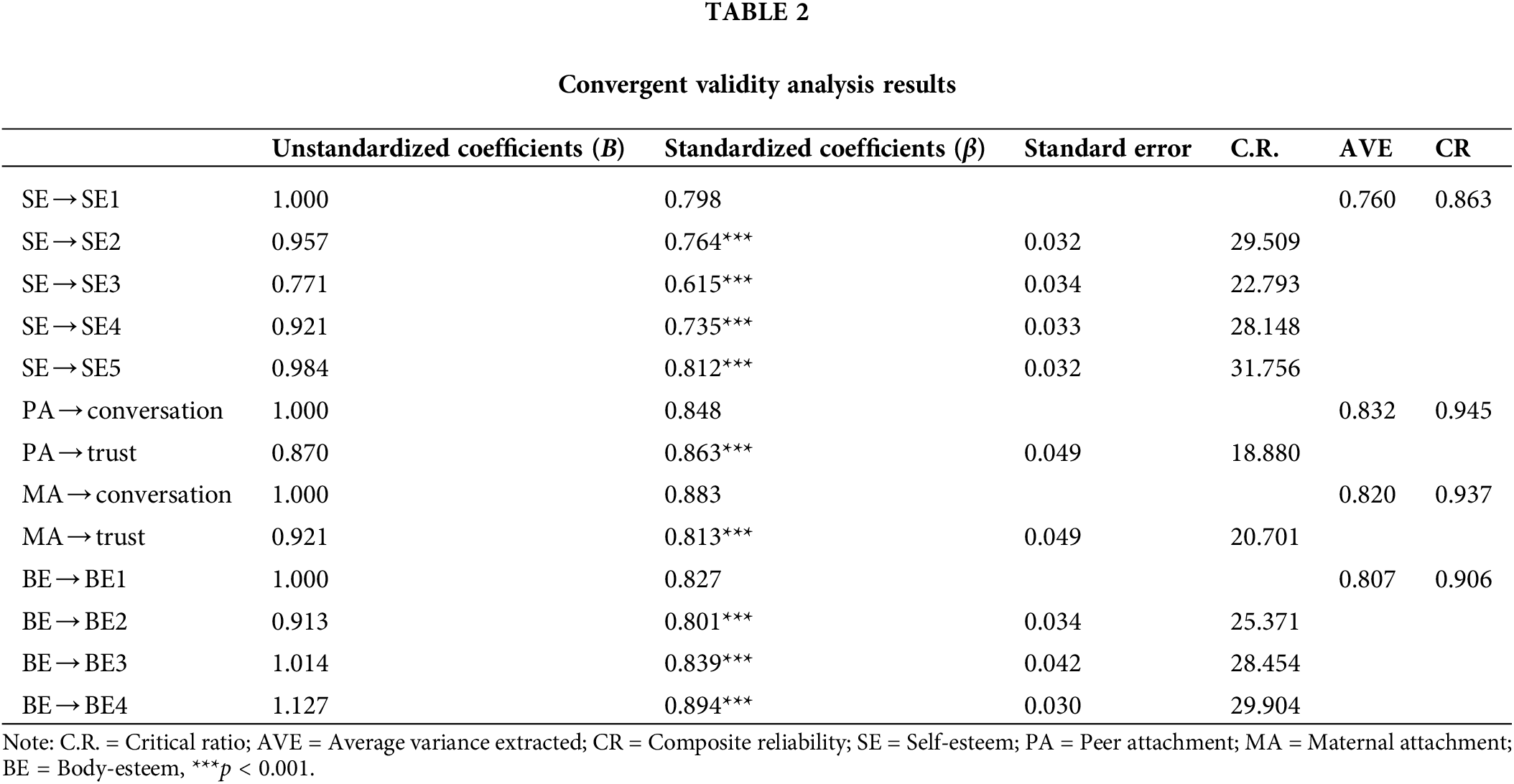

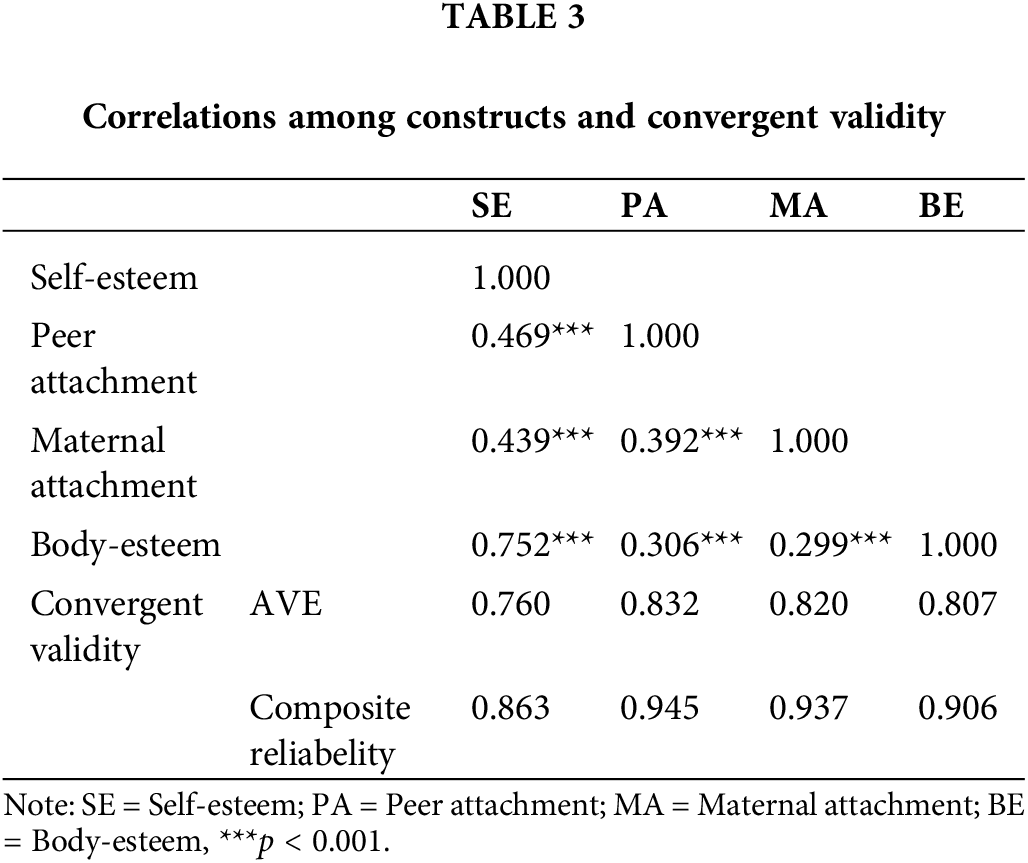

The measurement model was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis, yielding the following fit indices: χ2(df) = 358.098(38), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.956, TLI = 0.936, and RMSEA = 0.058. These values suggest that the model adequately fits the data. Convergent and discriminant validity were assessed to confirm the validity of the latent constructs. Convergent validity was verified with standardized estimates greater than 0.50, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values above 0.50, and Composite Reliability (CR) scores exceeding 0.70. As shown in Table 2, the standardized factor loading (β) for each observed variable ranged from 0.735 to 0.812 for self-esteem, 0.848 to 0.863 for peer attachment, 0.813 to 0.883 for maternal attachment, and 0.801 to 0.894 for body-esteem. All estimates were statistically significant at p < 0.001.

The AVE values for all latent variables exceeded 0.50, and the CR values were higher than 0.70, supporting convergent validity. Discriminant validity was verified by comparing the AVE values with the squared correlations between the constructs. Table 3 presents the inter-construct correlations based on the CFA results.

Structural equation model analysis

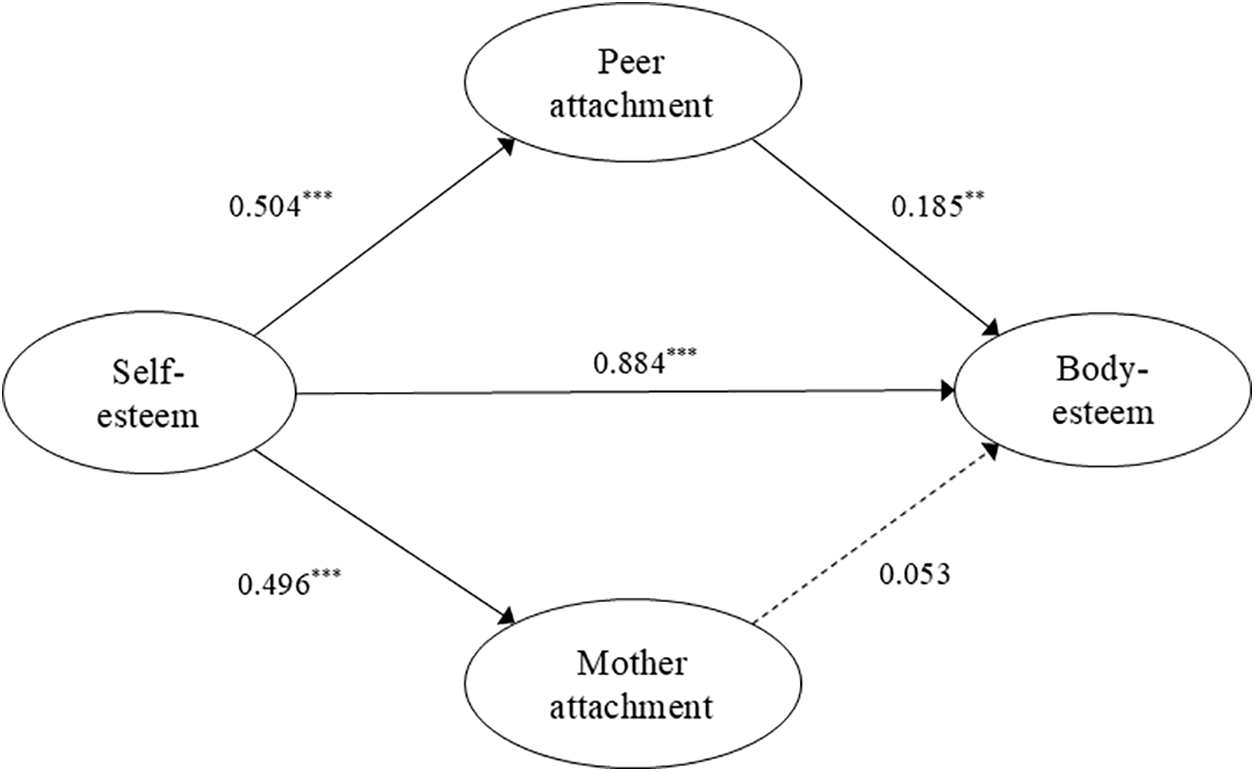

The structural relationships between self-esteem, peer attachment, maternal attachment, and body-esteem were examined using structural equation modeling (SEM), as depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Structural path model and coefficients.

Note: Unstandardized coeffifients are shown. Dotted paths represent non-significant paths. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

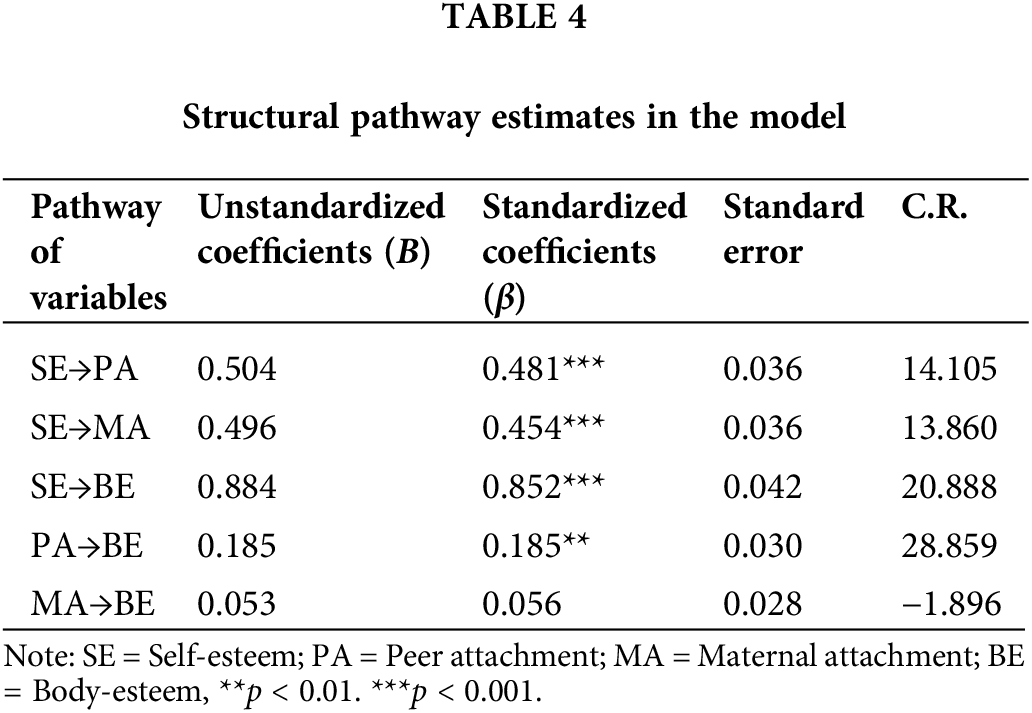

The maximum likelihood estimation method was used for parameter estimation. Model fit indices indicated an acceptable model fit: χ2(df) = 403.737(39), p < 0.001, CFI = 0.950, TLI = 0.929, and RMSEA = 0.058. Table 4 outlines the pathways in the model. Results revealed that self-esteem significantly and positively influenced peer attachment (β = 0.481, p < 0.001), maternal attachment (β = 0.454, p < 0.001), and body-esteem (β = 0.852, p < 0.001). Peer attachment also had a significant positive effect on body-esteem (β = 0.185, p < 0.01), whereas maternal attachment did not exhibit a significant impact on body-esteem.

To assess the mediating role of peer attachment in the relationship between self-esteem and body-esteem, a bootstrapping analysis was conducted. Results demonstrated that peer attachment significantly mediated the relationship between self-esteem and body-esteem (β = 0.043, p < 0.05, 95% CI = 0.08, 0.12).

This research investigated how self-esteem, as well as peer and maternal attachments, relate to body-esteem during early adolescence, with an emphasis on the mediating roles of peer and maternal attachments. The findings shed light on the complex relationships between these variables and provide insights into the factors that influence body-esteem among Korean adolescents. Importantly, this study makes a valuable contribution to existing literature by examining these dynamics within the unique cultural context of South Korea, where societal expectations regarding body image and appearance are particularly pronounced.

The direct effect of self-esteem

The results confirm the hypothesis that self-esteem exerts a positive influence on body-esteem, which aligns with previous findings highlighting self-esteem’s central role in shaping adolescents’ perceptions of their physical appearance [17,20]. These findings resonate with earlier research, which underscores the importance of global self-esteem in determining specific aspects of self-evaluations, such as body-esteem [16,21]. It is crucial to recognize that body-esteem encompasses not merely satisfaction with physical appearance but also an overall sense of worth derived from one’s body, which is closely related to personal identity [6,8]. Adolescents with high body-esteem are more likely to feel confident in social situations and develop a positive and realistic view of their bodies even in the face of societal pressures [4,7].

As adolescents become increasingly aware of societal standards and ideals, particularly those portrayed in the media, they may engage in social comparison, assessing their bodies against often unrealistic benchmarks [12]. The idealized images can distort adolescents’ perceptions of their own bodies, leading to body dissatisfaction. Those with lower self-esteem are especially vulnerable to the harmful effects of social comparison, particularly when exposed to unrealistic portrayals of beauty [13]. This often leads to increased body dissatisfaction, anxiety, and a higher risk of developing eating disorders [18,43]. In contrast, adolescents with higher self-esteem are more resilient to such detrimental comparisons. Their strong sense of self-worth acts as a buffer, allowing them to evaluate their physical appearance more objectively and resist external pressures from societal norms or peers [16,17].

On a global scale, studies from both Western and Asian contexts have consistently found that adolescents with higher self-esteem are better equipped to navigate social comparison and withstand societal pressures related to body image [8,12]. This resilience enables them to maintain a positive body image despite the pervasive influence of media portrayals [13,20]. In the context of South Korea, however, the pressure to adhere to specific beauty standards is exceptionally strong. Korean adolescents are especially susceptible to these pressures due to the cultural emphasis on physical appearance, which significantly affects their body-esteem, as noted in both Korean and other East Asian contexts [12,14].

The indirect effects of peer and maternal attachments

This study highlights the significant mediating effect of peer attachment on the relationship between self-esteem and body-esteem, emphasizing the critical impact of peer relationships during early adolescence. This finding aligns with prior studies indicating that peer relationships are integral to adolescent development, particularly in the formation of body image [30,32]. As adolescents seek acceptance and validation from peers, these relationships become a crucial source of support, reinforcing positive self-esteem and body image [33]. This dynamic reflects the broader need for social belonging and approval, suggesting that peer interactions are vital in developing a healthy body image during this formative period [43,44].

In contrast, this study found that maternal attachment did not significantly mediate the relationship between self-esteem and body-esteem. While traditional views emphasize strong parental influence during adolescence [25,28,31], this study suggests that the increasing importance of peer relationships may diminish the direct impact of maternal attachment on body image. In Korean society, this shift may be even more pronounced. Korean adolescents often face intense social and academic pressures, which may lead them to place greater value on peer approval than parental influence [11,14]. This trend mirrors those observed in other collectivist cultures, where the need for group belonging and peer validation becomes more prominent during adolescence [44,45].

Moreover, recent studies conducted within South Korea have reported a growing emphasis on body image and physical appearance among teenagers, driven largely by societal and media influences. Korean adolescents are frequently exposed to unrealistic beauty standards, often through media, further intensifying the role of peer attachment in shaping body-esteem. In this context, although maternal attachment continues to provide emotional support, its direct influence on body-esteem may be reduced as peer relationships take on a more dominant role [11,13].

Implications for interventions

The findings of this study suggest several key strategies for interventions that aim to enhance positive body-esteem and improve adolescent mental health. First, enhancing self-esteem should be a primary focus. Interventions designed to foster self-awareness and self-acceptance can aid adolescents in developing a healthy self-concept, making them less vulnerable to societal pressures regarding body image. Programs that encourage adolescents to identify their personal strengths and foster a positive sense of self-worth are essential components of these efforts. Furthermore, this study underscores the critical role of peer relationships in shaping body-esteem. As a result, interventions should prioritize creating supportive peer environments, such as peer-led mentoring programs and group-based activities. Considering the importance of peer influence within Korean culture, initiatives that incorporate peer involvement may be particularly effective in fostering body positivity among adolescents.

Practical recommendations for schools, parents, and policymakers

Based on these findings, it is recommended that schools and educational institutions focus on implementing programs that nurture both self-esteem and peer support systems. Group activities, peer mentoring, and social skills training can create a supportive environment where adolescents feel confident in their self-worth and body image. Schools should also collaborate with mental health professionals to organize workshops that address media literacy, educating students on the unrealistic portrayals of beauty standards in media, thus developing a more balanced and positive self-image.

For parents, maintaining open lines of communication and creating a nurturing home environment are crucial. While maternal attachment may not directly influence body-esteem, providing emotional support and encouraging self-acceptance remain vital in ensuring overall well-being. Parents should be encouraged to engage in meaningful conversations about body image and peer influence, equipping their children with the tools to resist negative societal pressures.

For policymakers, there is a strong case for integrating social-emotional learning (SEL) programs into school curricula to address the immense societal pressures adolescents face in terms of physical appearance and peer validation. National-level policies should support the development of peer mentoring systems and availability of mental health services within schools, ensuring that mental health evaluations are conducted regularly. Furthermore, workshops aimed at boosting self-esteem and fostering a positive body image should be tailored to align with Korean cultural values. These initiatives will help adolescents build resilience against appearance-based societal pressures, fostering healthier peer relationships and a stronger self-concept.

Limitaions and future research

Several limitations should be noted. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw conclusions about causal relationships between variables. Future research should employ longitudinal approaches to better clarify the directionality of the observed associations. Second, this study exclusively examined maternal attachment, thereby limiting the exploration of the distinct roles that both parents may have in shaping body-esteem. Future studies should also consider paternal attachment to provide a more holistic perspective on family dynamics and their influence on body-esteem. Lastly, other potential mediators, such as school environment, the use of social media, and broader cultural factors, should be explored in future research to offer a more nuanced understanding of the complex determinants of body-esteem.

This study highlights the important role of self-esteem and peer attachment in shaping body-esteem during early adolescence. The findings demonstrate that self-esteem has a direct positive influence on body-esteem, while peer attachment serves as a crucial mediator, enhancing the positive effects of self-esteem. These results emphasize the importance of interventions that focus on building self-esteem and fostering supportive peer networks to promote healthy body image among adolescents. Although maternal attachment provides emotional support, its direct influence on body-esteem was not significant, pointing to the increasing importance of peer relationships during this developmental stage. By examining both direct and indirect pathways within the specific cultural context of Korea, this study provides culturally relevant insights that can guide interventions focused on improving body-esteem and mental health in adolescents as they navigate this formative period.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Gukje Cyber University.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used in this study is available to individual researchers or institutions upon approval of the Korea Institute of Child Care and Education (KICCE, https://kicce.re.kr) (accessed on 28 October 2024).

Ethics Approval: No ethical approval was required for the secondary data analyses, as the data used in this study are open-access.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Ann Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):83–110. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Lerner RM. A life-span perspective for early adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Biological interactions in early adolescence. New York, NY: Routledge; 2021. p. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

3. Fioravanti G, Bocci Benucci S, Ceragioli G, Casale S. How the exposure to beauty ideals on social networking sites influences body image: a systematic review of experimental studies. Adolesc Res Rev. 2022;7(3):419–58. doi:10.1007/s40894-022-00179-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang SB, Haynos AF, Wall MM, Chen C, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Fifteen-year prevalence, trajectories, and predictors of body dissatisfaction from adolescence to middle adulthood. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019;7(6):1403–15. doi:10.1177/2167702619859331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Dunkley DM, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ. Examination of a model of multiple sociocultural influences on adolescent girls’ body dissatisfaction and dietary restraint. Adolescence. 2001;36(142):265–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Nelson SC, Kling J, Wängqvist M, Frisén A, Syed M. Identity and the body: trajectories of body esteem from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2018;54(6):1159–71. doi:10.1037/dev0000435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ricciardelli LA, Yager Z. Adolescence and body image: from development to preventing dissatisfaction. 1st ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2015. doi:10.4324/9781315849379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Alm S, Låftman SB. The gendered mirror on the wall: satisfaction with physical appearance and its relationship to global self-esteem and psychosomatic complaints among adolescent boys and girls. Young. 2018;26(5):525–41. doi:10.1177/1103308817739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ajmal A. The impact of body image on self-esteem in adolescents. Clin Couns Psychol Rev. 2019;1(1):44–54. doi:10.32350/ccpr.11.04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A. Body image and weight control in young adults: international comparisons in university students from 22 countries. Int J Obes. 2006;30(4):644–51. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kim B, Kim HS, Park S, Kwon JA. BMI and perceived weight on suicide attempts in Korean adolescents: findings from the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey (KYRBS) 2020 to 2021. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1107. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-16058-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Merino M, Tornero-Aguilera JF, Rubio-Zarapuz A, Villanueva-Tobaldo CV, Martín-Rodríguez A, Clemente-Suárez VJ. Body perceptions and psychological well-being: a review of the impact of social media and physical measurements on self-esteem and mental health with a focus on body image satisfaction and its relationship with cultural and gender factors. Healthcare. 2024;12(14):1396. doi:10.3390/healthcare12141396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Rodgers RF, Rousseau A. Social media and body image: modulating effects of social identities and user characteristics. Body Image. 2022;41(1):284–91. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.02.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. You S, Shin K, Kim E. The effects of sociocultural pressures and exercise frequency on the body esteem of adolescent girls in Korea. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(1):26–33. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0866-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Katsantonis I, McLellan R, Marquez J. Development of subjective well-being and its relationship with self-esteem in early adolescence. Br J Dev Psychol. 2023;41(2):157–71. doi:10.1111/bjdp.12436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Lacroix E, Atkinson MJ, Garbett KM, Diedrichs PC. One size does not fit all: trajectories of body image development and their predictors in early adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2022;34(1):285–94. doi:10.1017/S0954579420000917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kuck N, Cafitz L, Bürkner PC, Hoppen L, Wihelm S, Buhlmann U. Body dysmorphic disorder and self-esteem: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):310. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03185-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Vankerckhoven L, Raemen L, Claes L, Eggermont S, Palmeroni N, Luyckx K. Identity formation, body image, and body-related symptoms: developmental trajectories and associations throughout adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52(3):651–69. doi:10.1007/s10964-022-01717-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Roberts SR, Maheux AJ, Ladd BA, Choukas-Bradley S. The role of digital media in adolescents’ body image and disordered eating. In: Nesi J, Telzer EH, Prinstein MJ, editors. Handbook of adolescent digital media use and mental health. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2022. p. 242–63. [Google Scholar]

20. Meland E, Breidablik HJ, Thuen F, Samdal GB. How body concerns, body mass, self-rated health and self-esteem are mutually impacted in early adolescence: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):496. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10553-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Harter S. The development of self-esteem. In: Self-esteem issues and answers. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2013. p. 144–50. [Google Scholar]

22. Moradi M, Mozaffari H, Askari M, Azadbakht L. Association between overweight/obesity with depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and body dissatisfaction in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;62(2):555–70. doi:10.1080/10408398.2020.1823813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Eller J, Paetzold RL. Major principles of attachment theory. In: Van Lange P, Kruglanski A, Higgins ET, editors. Social psychology: handbook of basic principles. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2020. p. 222–39. [Google Scholar]

24. Ata RN, Ludden AB, Lally MM. The effects of gender and family, friend, and media influences on eating behaviors and body image during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36(8):1024–37. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9159-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Vagos P, Carvalhais L. The impact of adolescents’ attachment to peers and parents on aggressive and prosocial behavior: a short-term longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:592144. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.592144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Cash TF, Smolak L. Body image: a handbook of science, practice, and prevention. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

27. Davison TE, McCabe MP. Adolescent body image and psychosocial functioning. J Soc Psychol. 2006;146(1):15–30. doi:10.3200/SOCP.146.1.15-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Harandi TF, Taghinasab MM, Nayeri TD. The correlation of social support with mental health: a meta-analysis. Electron Physician. 2017;9(9):5212–22. doi:10.19082/5212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Morin AJS, Maïano C, Scalas LF, Janosz M, Litalien D. Adolescents’ body image trajectories: a further test of the self-equilibrium hypothesis. Dev Psychol. 2017;53(8):1501–21. doi:10.1037/dev0000355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Wilkinson RB. The role of parental and peer attachment in the psychological health and self-esteem of adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2004;33(6):479–93. doi:10.1023/B:JOYO.0000048063.59425.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Laible DJ, Carlo G, Raffaelli M. The differential relations of parent and peer attachment to adolescent adjustment. J Youth Adolesc. 2000;29(1):45–59. doi:10.1023/A:1005169004882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Brown B. Adolescent relationships with their peers. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. p. 363–94. [Google Scholar]

33. Tort-Nasarre G, Pollina-Pocallet M, Ferrer Suquet Y, Ortega Bravo M, Vilafranca Cartagena M, Artigues-Barberà E. Positive body image: a qualitative study on the successful experiences of adolescents, teachers and parents. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2023;18(1):77. doi:10.1080/17482631.2023.2170007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Miljkovitch R, Mallet P, Moss E, Sirparanta A, Pascuzzo K, Zdebik MA. Adolescents’ attachment to parents and peers: links to young adulthood friendship quality. J Child Fam Stud. 2021;30(6):1441–52. doi:10.1007/s10826-021-01962-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

36. Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 1987;16(5):427–54. doi:10.1007/BF02202939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Mendelson BK, White DR. Relation between body-esteem and self-esteem of obese and normal children. Percept Mot Skills. 1982;54(3):899–905. doi:10.2466/pms.1982.54.3.899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

39. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

40. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

41. Chen F, Curran PJ, Bollen KA, Kirby J, Paxton P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36(4):462–94. doi:10.1177/0049124108314720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

43. Holland G, Tiggemann M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image. 2016;17:100–10. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: do they predict social anxiety and depression? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(1):49–61. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Hill NE, Bromell L, Tyson DF, Flint R. Developmental commentary: ecological perspectives on parental influences during adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2007;36(3):367–77. doi:10.1080/15374410701444322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools