Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

How Does Social Media Usage Intensity Influence Adolescents’ Social Anxiety: The Chain Mediating Role of Imaginary Audience and Appearance Self-Esteem

1 Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior (CCNU), Ministry of Education, Wuhan, 430079, China

2 School of Psychology, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, 430079, China

3 School of Education Science, Hubei Normal University, Huangshi, 435000, China

* Corresponding Author: Fanchang Kong. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mattering in the Digital Era: Exploring Its Role in Internet Use Patterns and Mental Health Outcomes)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(12), 977-985. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.057596

Received 22 August 2024; Accepted 07 November 2024; Issue published 31 December 2024

Abstract

Background: To reduce adolescents’ social anxiety, the study integrates external factors (social media usage) with internal factors (imaginary audience and appearance-based self-esteem) to internal mechanisms of adolescents’ social anxiety in the Internet age based on objective self-awareness theory and self-esteem importance weighting model. Methods: Utilizing the Social Media Usage Intensity Scale, Social Anxiety Scale, imaginary Audience Scale, and Physical Self Questionnaire, we surveyed 400 junior high school students from three schools in Hubei province, China. Results: A significantly positive correlation is revealed between the intensity of social media usage and both social anxiety and imaginary audience (p < 0.001). Conversely, social media usage intensity and appearance self-esteem are significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.001). Additionally, the perception of an imaginary audience was negatively correlated with appearance self-esteem (p < 0.001). Furthermore, we found that imaginary audience (indirect effect of 0.14, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.07]) and appearance self-esteem (indirect effect of 0.14, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.07]) can respectively act as independent mediators between social networking site use intensity and social anxiety, Additionally, the relationship between imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem can also be chain-mediated (indirect effect of 0.03, 95% CI = [0.00, 0.02]) separately affect the relationship between the two. Conclusion: The imaginary audience serves as an independent mediator that links social media usage intensity to social anxiety among adolescents. Additionally, the observed chain mediation effect involving both the imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem provides novel insights for developing strategies aimed at addressing adolescent social anxiety.Keywords

Social anxiety (SA) is a prevalent anxiety disorder characterized by maladaptive emotional reactions, such as tension and shyness, during interpersonal interactions, which can arise from both actual and perceived stimuli [1]. The typical onset of social anxiety occurs during childhood or adolescence, usually between the ages of 14 and 16 years [2]. Both national and international research indicates that between 27.2% and 42.0% of the population experience elevated levels of SA [3]. Such heightened levels of SA not only undermine individual well-being but also hinder social adaptability, degrade the quality of interpersonal relationships, and may even lead to other mental disorders [4]. Therefore, understanding the determinants and underlying mechanisms of adolescent SA remains a primary focus of research.

The proliferation of social networking sites, characterized by straightforward communication, versatile user engagement, and personalized content, has solidified their status as preferred mediums for social interaction. According to the latest survey on internet usage in China, adolescents aged 10 to 19 constitute a significant segment of the online population, with 161 million users, accounting for 14.7% of the total internet users. Furthermore, a vast majority, 97% of these adolescents engage in instant messaging [5]. In a similar vein, a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center (2023) in the United States revealed that among teens aged 13 to 17, the usage rates for popular platforms are as follows: YouTube (90%), TikTok (63%), Snapchat (60%), and Instagram (59%). As the predominant demographic on social networking platforms and situated at a critical stage of psychosocial and physical development, adolescents are particularly susceptible to the onset of social anxiety [4]. Therefore, it is crucial to study the connection between social media use and adolescent social anxiety, as well as its underlying mechanisms.

Social media usage and adolescents’ social anxiety

Prominent social media platforms, including global networks such as Facebook and regional applications like QQ and WeChat, are founded on authentic interpersonal communication and interactions [6]. Social media usage intensity refers to the emotional investment and dependence exhibited during interactions on social networking platforms like WeChat and QQ [7]. The impact of social media usage on adolescents’ psychological growth, physical development, and social adaptability has emerged as a critical issue. Research findings indicate a robust association between the frequency of social media engagement and the onset and progression of social anxiety among adolescents [8,9]. On one hand, social psychology theory suggests that social networking sites can serve as a “compensatory” mechanism for individuals who struggle with interpersonal adaptation in real life, thereby alleviating certain psychological and behavioral aspects of social anxiety [10]. Conversely, social comparison theory posits that the high accessibility of social networking sites renders social comparison unavoidable, leading to increased self-focus among individuals. The use of these platforms can influence self-concept clarity through upward social comparisons and the internalization of information, ultimately contributing to the development of social anxiety [11].

Contemporary studies suggest that deep emotional investments and immersion in social media may foster maladaptive cognitive patterns in adolescents, leading to feelings of social disconnection and the emergence of anxiety states [6]. According to the Cognitive-Behavioral Model of social anxiety, an excessive emphasis on self-presentation in social contexts can inadvertently activate negative historical experiences and emotions, resulting in distorted cognitive assessments and subsequent feelings of apprehension and aversion [12,13]. Given the pivotal role of social media in shaping adolescent social interactions in contemporary society, it may serve as a novel catalyst for social anxiety among this demographic. Based on the aforementioned assertions, we propose the following hypothesis: Social media usage intensity is significantly positively related to social anxiety among adolescents (H1).

The mediating role of the imaginary audience

As individuals enter adolescence, they undergo significant physiological, psychological, and social transitions. These changes heighten self-consciousness, leading to an increased preoccupation with how they are perceived by others [14]. This preoccupation gives rise to the phenomenon known as the “imaginary audience”, where adolescents feel as though they are constantly being observed by their peers, a manifestation that is intricately linked to the individuation-separation stage of adolescence [14]. Furthermore, existing literature indicates a strong relationship between social media engagement and the sensation of this imaginary audience [15]. Unlike face-to-face interactions, social media allows individuals to curate their self-presentation based on anticipated audience reactions. Feedback received on these platforms can amplify adolescents’ feelings of being scrutinized [7,16]. This heightened sense of scrutiny may arise from pervasive upward comparisons facilitated by social media, further intensifying adolescents’ self-focus [17,18]. Notably, many online friendships stem from offline connections [19], suggesting that the perceived “audience” during online self-presentation often includes familiar individuals, thereby enhancing the impact of social media on the experience of the imaginary audience.

Additionally, adolescents with an intensified sense of the imaginary audience often demonstrate heightened self-consciousness during everyday interactions, which may lead to the emergence of anxiety [19]. Social anxiety, a distressing emotional experience, is influenced by factors such as self-concept clarity and the perception of an imaginary audience [3]. Quantitative analyses have established a strong correlation between the imaginary audience and adolescent social anxiety, with the former serving as a significant positive predictor for the “worry and fear of negative evaluation” component of social anxiety [11]. Furthermore, another study indicates that the imaginary audience is a critical predictor of increased social anxiety levels among adolescents [20]. The cognitive-behavioral theory of social anxiety posits that maladaptive cognition within social contexts is a primary contributor to social anxiety [12,13]. Given this context, it can be inferred that intensive social media usage may heighten adolescents’ perceptions of the imaginary audience, consequently exacerbating social anxiety. Therefore, this research proposes the hypothesis that the imaginary audience mediates the relationship between social media usage intensity and adolescent social anxiety (H2).

The mediated role of appearance self-esteem

Digital platforms, particularly social media, are saturated with content related to physical aesthetics, significantly influencing individuals’ self-perceptions of their own appearance [11]. Appearance self-esteem refers to an individual’s cognitive evaluation and emotional response to their physical appearance, which profoundly impacts their overall emotional and psychological well-being [21]. Consequently, the extent of social media engagement may affect appearance and self-esteem. Empirical evidence suggests that social media usage, such as liking and commenting on others’ posts, predicts a decrease in appearance self-esteem from childhood through adolescence [22]. The widespread dissemination of “idealized thinness” narratives on these platforms exacerbates body dissatisfaction [23], thereby adversely affecting adolescents’ appearance and self-esteem. Additionally, the Importance-Weighted Model of Self-Esteem posits that appearance self-esteem is influenced not only by self-evaluations across specific dimensions but also by the significance attributed to those dimensions [24]. Given that adolescents, during puberty, are particularly sensitive to their physical presentation and external evaluations [23], the omnipresent portrayals of the “ideal physique” and related discussions on social media may amplify upward social comparisons, further diminishing their appearance and self-esteem.

Moreover, self-esteem serves as a critical protective buffer against social anxiety, with individuals exhibiting diminished self-esteem being more vulnerable to its development [3]. According to the Vulnerability Model of Self-Esteem, individuals in a compromised cognitive state, such as low self-esteem, are predisposed to interpret external feedback negatively, resulting in maladaptive emotional states like social anxiety. Conversely, a resilient cognitive perspective can help mitigate these negative emotional responses [25]. Elevated self-esteem provides individuals with greater psychological resilience, thereby reducing the likelihood of experiencing social anxiety [26]. As a significant component of overall self-esteem, appearance self-esteem also predicts levels of social anxiety among adolescents [21]. Based on the preceding discussion, this research posits that increased social media engagement may diminish adolescents’ appearance and self-esteem, leading to an escalation in social anxiety. Consequently, the research proposes the hypothesis: Appearance of self-esteem plays a mediating role in the relationship between social media usage intensity and adolescent social anxiety (H3).

Furthermore, previous research indicates that the imaginary audience negatively correlates with adolescents’ self-esteem [15]. Adolescents with a heightened perception of the imaginary audience tend to be more concerned about the impressions they project to others. This preoccupation with seeking affirmation intensifies their awareness of perceived flaws, particularly regarding their physical appearance [14]. Additionally, the Objective Self-Awareness (OSA) Theory posits that environmental awareness interacts with individual social behavioral tendencies [27]. In the context of online social networking, when individuals believe that their actions are being observed by others, their perception of the imaginary audience increases significantly. This heightened perception, in turn, affects self-awareness and may lead to feelings of social anxiety [10]. Consequently, this research proposes that social media platforms may amplify perceptions of the imaginary audience, thereby diminishing appearance self-esteem, which may ultimately contribute to the development of social anxiety among adolescents. Thus, the formulated hypothesis states that imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem play a chain-mediated role in the association between adolescent social anxiety and social media engagement (H4).

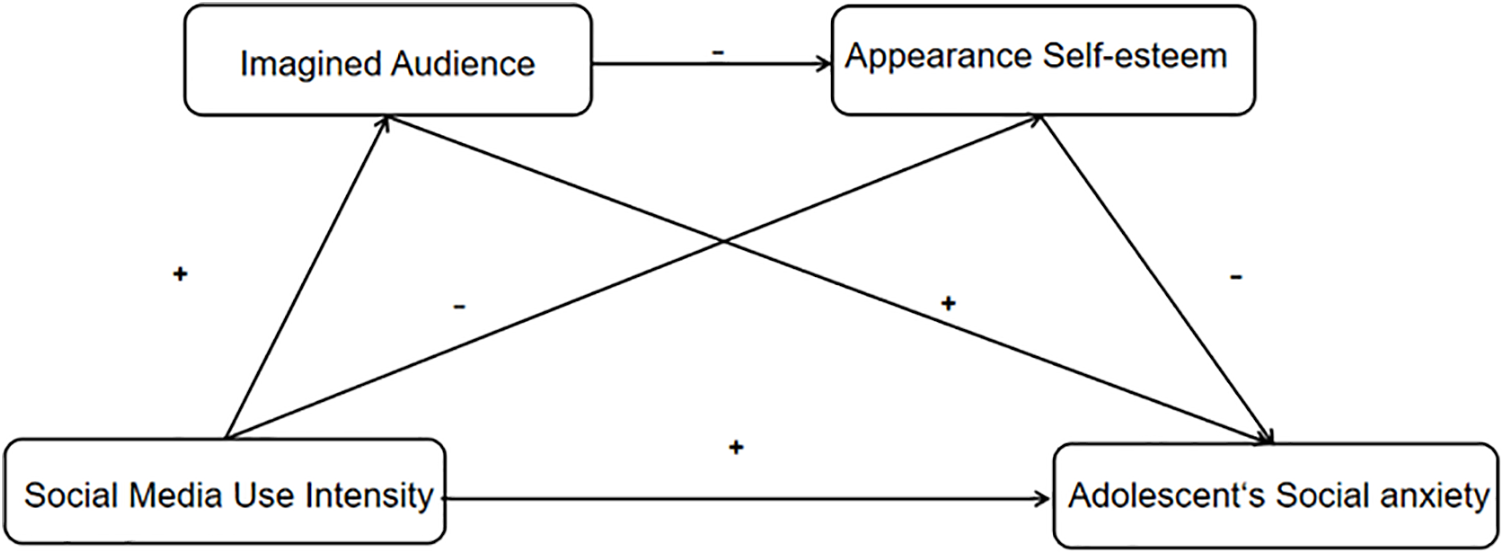

In summary, this research, grounded in Objective Self-Awareness Theory and the Importance-Weighted Model of Self-Esteem, integrates external factors (social media usage) with internal factors (imaginary audience and appearance-based self-esteem) to examine the correlation between the intensity of social media usage and adolescent social anxiety, along with the underlying mechanisms involved. The primary objective is to reduce social anxiety among adolescents and provide a reliable theoretical basis. The conceptual model is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Hypothesized model.

Surveys were administered to 430 students across three junior high schools located in Hubei province, with classes serving as the sampling units. From these, 400 valid responses were obtained, resulting in a 93.02% response rate. The gender distribution consisted of 221 males (55.25%) and 179 females (44.75%). The grade distribution was as follows: 155 first-year students, 111 second-year students, and 134 third-year students. The participants’ ages ranged from 12 to 16 years (Mean = 13.91, Standard Deviation (SD) = 1.04).

Social media usage intensity questionnaire

This questionnaire was originally developed by Ellison, et al. [28], and verified by Niu et al. [7] in Chinese adolescents, which to evaluate emotional investment and dependent on social media. For example, social media is integral to my daily activities. The questionnaire encompasses 8 items. The initial two items capture the number of connections on platforms such as Qzone, WeChat Moments, and RenRen as well as the average daily engagement duration. The subsequent six items utilize a Likert scale of 5 points, ranging from 1 (indicating “Strongly Disagree”) to 5 (indicating “Strongly Agree”). Given the variability in scoring procedures, scores from individual items were standardized and subsequently averaged, providing a metric for the intensity of a respondent’s social media engagement. This measurement has confirmed its reliability and validity for Chinese adolescents [29]. In this research, the Cronbach’s α coefficient reached 0.80.

Adolescent social anxiety scale

This scale, adapted and translated by Zhu [30] quantifies the extent of social anxiety experienced by adolescents. It comprises 13 items spanning three dimensions: apprehension of negative evaluations, distress in routine and novel settings, and tendencies for social avoidance. For example, I become reserved when surrounded by unfamiliar individuals. A 5-point Likert scale is employed, with scores ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). An aggregate of the scores from all items yields the overall social anxiety score, wherein elevated scores signify heightened levels of social anxiety. For this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was ascertained to be 0.92.

Originating from the Adolescent Egocentrism Scale by Liu et al. [31], the subscale which is named the imaginary audience scale incorporates 6 items. For example, When I wear new attire and venture out, individuals in the vicinity tend to observe. This scale evaluates a singular dimension and employs a 6-point scoring metric, from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree). The aggregate score across all items results in the total imaginary audience score, where elevated scores signify an intensified perception of an imaginary audience. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was identified to be 0.72 in this investigation.

This scale was from the Chinese version of the Physical Self-Description Questionnaire, which was developed by [32]. It includes 8 items, for example, I am satisfied with my facial features. The scale adopts a 6-point scoring metric, from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree). The total scores indicate the level of appearance self-esteem, the higher score denotes heightened self-esteem about one’s appearance self-esteem. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.81 in this research.

Utilizing classes as the sampling unit, participants were furnished with a standardized questionnaire and accompanying guidelines for a group assessment. The questionnaire used in this current study was approved by the Central China Normal University Human Ethics Committee (CCNU-IRB-202403023A). Considering that the study subjects were middle school students, the informed consent forms were brought by the students to the parents for signing, and handed over to the researcher after completion. Questionnaires were disseminated and accrued in situ, with the data-gathering phase concluding within a week. In line with preceding studies [7], both age and gender were statistically controlled. Males were coded as “1” while females received a “1” coding. Analytical procedures are run by SPSS 24.0 for descriptive statistics and correlational analyses, with mediation effect analyses conducted by Mplus 8.0. Before the main variables enter the mediation model they are standardized. To estimate the mediation effect, the Bias-corrected Bootstrap technique (n = 5000) is employed. When the 95% confidence interval does not encompass zero, it signifies a significant effect.

A Harman single-factor test was conducted, where all items were subjected to an unrotated principal component factor analysis. The results of the analysis showed that 15 factors had eigenvalues greater than 1. Importantly, the first factor accounted for only 18.94%, which is below 40% [33], suggesting no significant common method bias in this study.

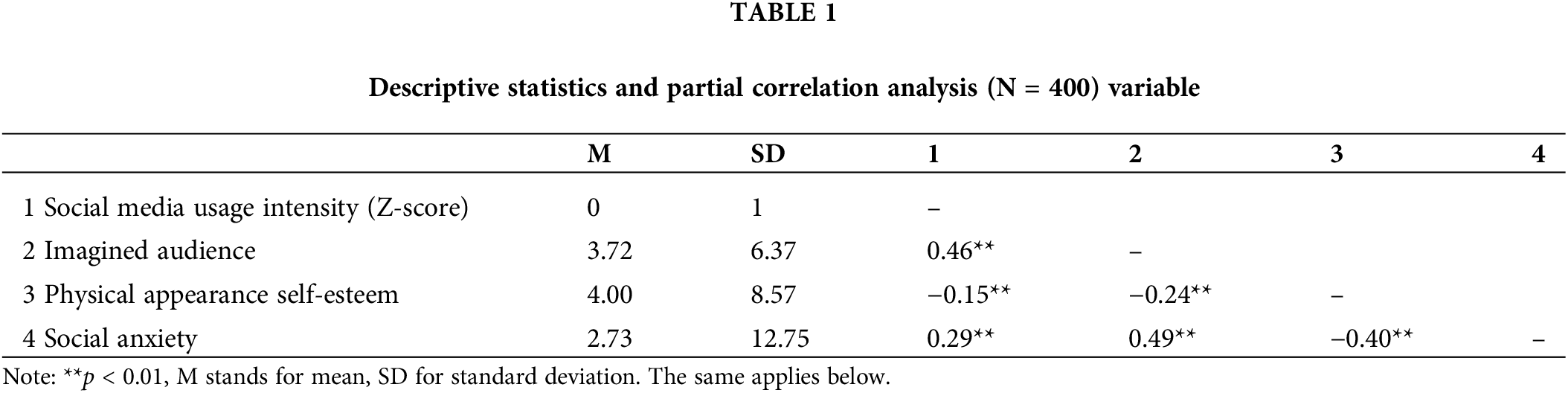

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Results showed that the mean duration of social media usage for adolescents was 3.80 ± 1.82 years. The mean value of daily social media usage was 32.4 ± 15.6 min. The mean count of friends on these platforms was 45.21 ± 17.22, while the mean score highlighting emotional involvement and integration with daily routines was 2.67 ± 0.80.

After controlling gender, age, total household income, parental education level, and duration of social media usage, the correlation analyses discerned significant associations between social media usage intention, imaginary audience, appearance self-esteem, and social anxiety. Specifically, social media usage intensity is positively related to social anxiety and imaginary audience, and negatively related to appearance self-esteem. Moreover, an imaginary audience is negatively related to appearance and self-esteem. Furthermore, imaginary audience positively related to adolescent social anxiety, and appearance self-esteem negatively related to adolescent social anxiety. These associations are detailed in Table 1.

Results showed that social media usage intensity positively predicted adolescents’ imaginary audience perceptions (β = 0.43, t = 9.95, p < 0.001) and it can predict appearance self-esteem (β = −0.06, t = 1.13, p < 0.01). However, it cannot predict social anxiety (β = 0.08, t = 1.51, p > 0.05). Moreover, Imaginary audience negatively predicted appearance self-esteem (β = −0.18, t = −3.21, p < 0.001) and positively predicted social anxiety (β = 0.39, t = 7.39, p < 0.001). Moreover, appearance self-esteem negatively predicted social anxiety (β = −0.30, t = −6.00, p < 0.001).

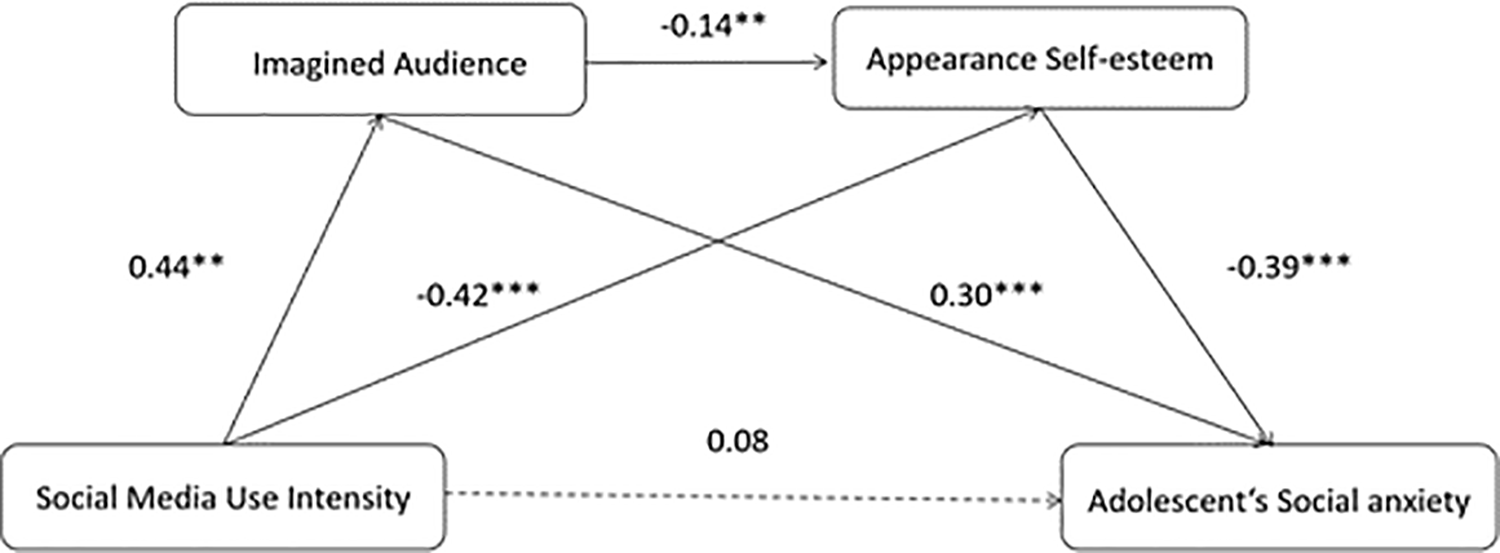

The results of the chain mediation model showed that social media usage intention significantly positively predicted imaginary audience (β = 0.44, p < 0.001) and negatively predicted appearance self-esteem (β = −0.42, p < 0.01). However, social media usage intention did not significantly predict adolescent social anxiety (β = 0.08, p > 0.05). imaginary audience significantly negatively predicted appearance self-esteem (β = −0.14, p < 0.01) and significantly positively predicted adolescent social anxiety (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). Appearance self-esteem significantly negatively predicted social anxiety (β = −0.39, p < 0.001).

Results showed that the mediation effect consisted of three indirect effects: (1) imaginary audience as independent mediator (indirect effect 1); (2) appearance self-esteem as independent mediator (indirect effect 2); (3) imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem as a chain mediator (indirect effect 3). The 95% confidence intervals for indirect effect 1 (95% CI [0.02, 0.07]), indirect effect 2 (95% CI [0.12, 0.21]), and indirect effect 3 (95% CI [0.00, 0.02]) did not include zero, indicating that the effects were significant.

The mediation analysis results (Fig. 2) indicated that the imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem had a significant mediating effect on the relationship between social media usage intensity and social anxiety, with a total mediation effect of 0.21, accounting for 72.41% of the total effect (0.29). The mediation effect consisted of three indirect pathways: the indirect effect from social media use intensity to social anxiety through imaginary audience (effect coefficient 0.14), the indirect effect from social media use intensity to social anxiety through appearance self-esteem (effect coefficient 0.04), and the indirect effect from social media use intensity to social anxiety through imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem (effect coefficient 0.03). These three indirect pathways accounted for 48.27%, 13.79%, and 10.35% of the total effect, respectively. The 95% confidence intervals for all these indirect effects did not include zero, indicating that all effects were significant.

Figure 2: Chain mediation model of the relationship between social media usage intensity and adolescents’ social anxiety.

Note: **p < 0.01; ***p < 0. 001.

This research investigates the process through which social media engagement influences adolescent social anxiety, focusing on the mediating roles of intrinsic psychological factors, specifically, the imaginary audience and appearance-based self-esteem. A more detailed exploration of the relationships between these factors is needed, along with an examination of the moderating effects of other factors.

Relationship between social media usage intensity and social anxiety

The results indicate a significant positive association between social media engagement and social anxiety. Subsequent regression analyses further support a strong positive predictive relationship between these two variables. However, when the imaginary audience and appearance-based self-esteem are included in the regression models, the direct predictive effect of social media usage intensity on social anxiety loses its statistical significance [7]. Sharing personal experiences on social platforms may alleviate feelings of isolation, strengthen interpersonal relationships, enhance self-esteem, and provide emotional support for adolescents [8]. In contrast, engaging in upward social comparisons on these platforms may erode self-esteem and increase vulnerability to anxiety [6]. A longitudinal study [34] found that online interactions centered on health concerns can exacerbate negative emotional states, such as anxiety, whereas digital communications directed toward family or friends can mitigate these negative emotions. This suggests that the outcomes of social media engagement may vary depending on the intent and content of the interaction [6]. It can thus be inferred that the motivation and nature of social media engagement may exert a more substantial influence on outcomes like social anxiety than merely the intensity of use.

Independent mediated role of imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem

The results indicate that the intensity of social media usage influences adolescent social anxiety through the mediating role of the imaginary audience. Social media platforms provide adolescents with spaces for nuanced self-presentation, and those with heightened tendencies toward an imaginary audience are more likely to amplify and emphasize these personalized aspects of presentation, thereby intensifying anxiety related to social perceptions and interactions [8]. This suggests that the imaginary audience may act as a catalyst for social anxiety. Supporting this, concurrent research demonstrates that negative online experiences and envy arising from social media interactions serve as significant mediators that exacerbate anxiety and depression [29]. These findings reinforce the idea that heightened perceptions of an imaginary audience, driven by social media engagement, are a key factor contributing to maladaptive outcomes in adolescents. Therefore, it is crucial to equip adolescents with the skills to critically evaluate online information, strengthen their interpersonal relationships, and cultivate a coherent and resilient self-concept to enhance their digital social well-being.

Moreover, the intensity of social media usage influences adolescent social anxiety through the mediating role of appearance-based self-esteem, supporting hypothesis H3. This can be explained by both the Importance-Weighted Model and the Vulnerability Model of self-esteem, which posit that low self-esteem contributes to social anxiety. Specifically, Lower levels of self-esteem make individuals more likely to interpret external evaluations negatively, resulting in maladaptive emotional responses, such as social anxiety. Social comparison theory further emphasizes that adolescents, particularly during their teenage years, place considerable emphasis on physical appearance and the evaluations of others. In the online environment, the widespread portrayal of the “ideal body image” and related comments can intensify upward social comparisons, thereby undermining adolescents’ appearance-based self-esteem. As research has shown, diminished appearance-based self-esteem is a significant contributing factor to social anxiety [34].

Although both appearance-based self-esteem and the imaginary audience demonstrate significant results as independent mediators, the relative contributions of these two pathways to the total effect vary. This can be understood from several perspectives. First, the participants in this study are middle school students, whose focus is predominantly on academic tasks and performance. Adolescents often lack independent control over their time spent on the internet, which may limit their engagement with social networking sites and may not reflect their actual social needs. Second, academic pressure significantly restricts daily social media usage among adolescents. Factors such as campus culture and the prevailing social culture in Chinese middle schools tend to diminish attention to physical appearance. Given their academic orientation, these students are likely to prioritize scholastic achievements over concerns related to physical appearance, potentially reducing the influence of social media on their appearance-based self-esteem. Consequently, the effect of social media use on social anxiety might be heightened by the mediating roles of the imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem. Third, the psychological constructs of the imaginary audience and concern for appearance are salient characteristics of adolescence. This developmental stage is also marked by increased self-awareness and the formation of a stable self-concept. Consequently, individuals in this stage are particularly susceptible to external influences and may experience heightened social anxiety stemming from upward social comparisons made online.

Chain mediation effects of imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem

The results indicate that social media usage influences individuals’ social anxiety through a chain mediation effect involving the imaginary audience and appearance self-esteem. These findings support hypothesis H4 and are consistent with Objective Self-Awareness Theory [27]. According to this theory, individuals operate within two internal systems: the self-system, which is oriented towards aligning one’s behavior, attitudes, or traits with perceived standards. Adolescents are particularly sensitive to their presentations on social media and tend to overestimate the significance of appearance in the eyes of others. As a result, they may experience heightened fears and concerns related to social interactions on these platforms, ultimately leading to increased social anxiety.

Furthermore, the Cognitive-Behavioral Theory of Social Anxiety [12] posits that unpleasant experiences in interpersonal interactions can lead adolescents to encode cognitive information, such as “I am not good,” into memory. The continuous internalization of this cognitive information can heighten self-focus and increase awareness of the imaginary audience [17]. Individuals with a heightened perception of the imaginary audience often demonstrate diminished appearance self-esteem [35,36]. Consistent with the Vulnerability Hypothesis of Self-Esteem, those with reduced self-worth are likely to possess cognitive schemas that predispose them to distorted perceptions of social dynamics, ultimately resulting in increased anxiety [20]. As a unique aspect of adolescent psychology, the imaginary audience magnifies negative feedback related to appearance, subsequently shaping one’s psychological disposition and social behavior [20]. Evidence suggests that adolescents with heightened perceptions of the imaginary audience exhibit a strong inclination to seek emotional validation in interpersonal contexts as a means of affirming their self-worth [8]. Additionally, during this developmental stage characterized by the quest for self-identity, there is a pronounced desire for social engagement. However, misinterpretations of social feedback can rapidly undermine their appearance and self-esteem, leading to increased social anxiety [37,38].

There are several limitations to the current study. First, cross-sectional design was employed inherently limits the capacity to discern causal relationships between independent and dependent variables. Future research employing longitudinal designs could provide more robust insights into causality and its moderating factors. Second, while a clear association was found between the intensity of social media engagement and adolescents’ imaginary audience, the complex dynamics of social media interactions—such as interpersonal feedback and specific online behaviors—may interact with the imaginary audience construct in unique ways. These nuances should be explored in greater depth in future studies. Lastly, the participants in this study were drawn from several junior middle schools in the eastern part of Hubei province, China. Future research should expand the sample size and broaden sample regions to recruit more participants with diverse cultural backgrounds to retest and clarify how social media use affects adolescent social anxiety.

We found two mediation paths between social media usage intensity and social anxiety among adolescents: (1) the imaginary audience serves as an independent mediator that links social media usage intensity to social anxiety among adolescents; (2) the imaginary audience and appearance of self-esteem serve as a chain mediation effect that links social media usage intensity to social anxiety among adolescents.

This study holds significant theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, it examines the relationship between social media use and social anxiety, providing support for both the Cognitive-Behavioral Theory of Social Anxiety and the Importance-Weighted Model of Self-Esteem. Furthermore, it extends research on Social Anxiety Theory and the Vulnerability Hypothesis of Self-Esteem within a digital context. Integrating external factors (social media use) with internal factors (imaginary audience and appearance-based self-esteem) clarifies the connection between the imaginary audience and appearance-based self-esteem, enriching the literature on the emergence of social comparison in the digital age.

Practically, this study provides a theoretical basis for the development of prevention and intervention strategies aimed at adolescent social anxiety in the context of digital media. To reduce social anxiety and promote healthy internet use among adolescents, mental health interventions should focus on promoting a realistic understanding of physical appearance and fostering the development of a healthy self-concept. Additionally, encouraging adolescents to engage in offline social interactions could enhance their interpersonal confidence and communication skills, while fostering a more objective perspective on others’ evaluations and attitudes.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge technical support from the Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior (CCNU), Ministry of Education. We also thank anonymous reviewers and their constructive comments.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of Humanities and Social Science project (2022YJA190006) and Research Program Funds of the Collaborative Innovation Center of Assessment toward Basic Education Quality at Beijing Normal University (2023-04-010-BZPKO1).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Study conception and design were carried out by Yunyu Shi and Fanchang Kong; data collection was conducted by Yunyu Shi; analysis and interpretation of the results were performed by Yunyu Shi; and the manuscript was drafted by Yunyu Shi, Fanchang Kong and Min Zhu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The current study was approved by the Central China Normal University Human Ethics Committee (CCNU-IRB-202403023A). Considering that the study subjects were middle school students, the informed consent forms were brought by the students to the parents for signing, and handed over to the researcher after completion.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Fernández RS, Pedreira ME, Boccia MM, Kaczer L. Commentary: forgetting the best when predicting the worst: preliminary observations on neural circuit function in adolescent social anxiety. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1088. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ran G, Zhang Q, Huang H. Behavioral inhibition system and self-esteem as mediators between shyness and social anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270(2):568–73. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.10.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang Y, Li S, Yu G. The relationship between self-esteem and social anxiety: a meta-analysis with Chinese students. Adv Psychol Sci. 2010;27(6):1005. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2019.01005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen B, Huang X, Niu G, Sun X, Cai Z. Developmental change and stability of social anxiety from toddlerhood to young adulthood: a three-level meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychol Sin. 2023;55(10):1637. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2023.01637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. China Internet Information Center. The 54st China internet development status report. 2024. Available from: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/NMediaFile/2024/0911/MAIN1726017626560DHICKVFSM6.pdf. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

6. Kong F, Wang M, Sun Y, Xia Y, Li X. The relationship between parental mobile phone neglect behavior and adolescents’ sense of alienation: a moderated mediation model. Stu Psychol Behav. 2021;19(4):486–92. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2019.01005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Niu G, Sun X, Zhou Z, Kong F, Tian Y. The impact of social network site (Qzone) on adolescents’ depression: the serial mediation of upward social comparison and self-esteem. J Psychol Sci. 2016;10(48):1282–98. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dai H, Guo F, Chen Z. Effect of imaginary audience on social network sites use in adolescents: a multiple mediating model. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2020;28(3):581–5 (In Chinese). doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.03.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. O’Reilly M. Social media and adolescent mental health: the good, the bad and the ugly. J Ment Health. 2020;29(2):200–6. doi:10.1080/09638237.2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhu L, Ye B, Ni L. Social exclusion on college students’ online deviant behavior: the mediating effect of social anxiety and moderating effect of negative online emotion experience. Chin J Spec Educ. 2020;1(96):79–83 (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2020.01.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Guo L, Huang M, Cai G. The influence of fashion media exposure on female middle school students’ eating disorders: the serial mediating roles of self-objectification and appearance anxiety. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2021;29(2):343–6 (In Chinese). doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.02.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Blöte AW, Miers AC, Heyne DA, Clark DM, Westenberg PM. The relation between social anxiety and audience perception: examining Clark and Wells’ (1995) model among adolescents. Behav Cogn Psychoth. 2014;42(5):555–67. doi:10.1017/S1352465813000271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Heimberg RG, Brozovich FA, Rapee RM. A cognitive-behavioral model of social anxiety disorder. In Social anxiety (third edition). USA: Academic Press; 2014. p. 705–28. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-394427-6.00024-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Guo F, Lei L. Relationship among imaginary audience personal fable and internet communication in early adolescents. Psychol Dev Educ. 2009;4:43–9 (In Chinese). doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2009.04.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Guo C. The relationship between college students’ egocentrism and subjective well-being: the mediating effect of self-esteem. Stu Psychol Behav. 2019;17(4):546–52. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2019.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Terán L, Yan K, Aubrey JS. But first let me take a selfie: US adolescent girls’ selfie activities, self-objectification, imaginary audience beliefs, and appearance concerns. J Child Media. 2020;14(3):343–60. doi:10.1080/17482798.2019.1697319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang Y, Qiao X, Wang H. Appearance comparisons on social networking sites and body dissatisfaction: a moderated mediation model of peer appearance pressure and self-objectification. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2023;31(2):459–62 (In Chinese). doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2023.02.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zheng D, Ni X, Luo Y. Selfie posting on social networking sites and female adolescents’ self-objectification: the moderating role of imaginary audience ideation. Sex Roles. 2019;80:325–31. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0937-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou Z, Cao M, Tian Y. Parent-child relationship and depression in junior high school student the mediating effect of self-esteem and emotional resilience. Psychol Dev Educ. 2021;37(6):864–75. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2021.06.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Du A, Hua X, Tian F. Influence of middle school students’ parental cohesion on school alienation: the mediator effects of imaginary audience. Psychol Res. 2021;4:369–74. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1159.2021.04.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Leary MR, Schreindorfer LS, Haupt AL. The role of low self-esteem in emotional and behavioral problems: why is low self-esteem dysfunctional? J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;14(3):297–314. doi:10.1521/jscp.1995.14.3.297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kong F, Qin J, Huang B, Zhang H, Lei L. The effect of social anxiety on mobile phone dependence among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;108(5):104517. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang Y, Xie X, Chen H. Body image disturbance among females: the influence mechanism of social network sites. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2017;25(3):1079–87 (In Chinese). doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.06.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Pelham BW, Swann WB. From self-conceptions to self-worth: on the sources and structure of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(4):672–80. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.57.4.672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Orth U, Robins RW, Meier LL, Conger RD. Refining the vulnerability model of low self-esteem and depression: disentangling the effects of genuine self-esteem and narcissism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016;110(1):133–49. doi:10.1037/PSPP0000038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wang N, Wang L. Effect of moments about appearance on female baby image. Chin J Health Psychol. 2020;27(12):66–71. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2020.01.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Duval S, Wicklund RA. A theory of objective self-awareness. USA: Academic Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

28. Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Comput-Media Comm. 2007;12(4):1143–68. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Luo Y, Kong F, Niu G, Zhou Z. The impact of stressful events on middle school students’ depression: role of online use motivation and online use intensity. Psychol Dev Educ. 2017;49(3):49–60. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2017.03.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhu H. A study on the relationship of attachment to social anxiety among adolescents (Ph.D. Thesis). Southwest University: China; 2008. p. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

31. Liu L, Li L. Ego-centrism of 93 adolescents. Chin Ment Health J. 2007;21(7):461–3 (In Chinese). doi:10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2007.07.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Schipke D, Freund PA. A meta-analytic reliability generalization of the Physical self-description questionnaire (PSDQ). Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13(6):789–97. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhou H, Long L. Statistical tests and control methods for common method bias. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;6(3):942–50. doi:10.1007/BF02911031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Obeid N, Buchholz A, Boerner KE, Henderson KA, Norris M. Self-esteem and social anxiety in an adolescent female eating disorder population: age and diagnostic effects. Eat Disord. 2013;21(2):140–53. doi:10.1080/10640266.2013.761088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Berger U, Keshet H, Gilboa-Schechtman E. Self-evaluations in social anxiety: the combined role of explicit and implicit social-rank. Pers Indiv Differ. 2017;10(4):368–73. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Schlenker BR, Wowra SA, Johnson RM, Miller ML. The impact of imagined audiences on self-appraisals. Pers Relationship. 2008;15(2):247–60. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00196.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kong L, Cui X, Tian L. The relationship between the intensity of WeChat use and college students’ self-esteem: the role of upward social comparison and closeness to friends. Psychol Dev Educ. 2021;37(4):576–83. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2021.04.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ye S, Lu Y, Li K. A cross-lagged model of self-esteem and life satisfaction: gender differences among Chinese university students. Pers Indiv Differ. 2012;52(4):546–51. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools