Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Do Victims Defend Victims? The Mediating Role of Empathy between Victimization Experience and Public-Defending Tendency in School Bullying Situations

1 School of Law, Department of Social Work, Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics, Hangzhou, 310018, China

2 Research Institute of Social Development, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu, 611130, China

* Corresponding Author: Kunjie Cui. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Healthy Lifestyle Behaviours and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(12), 1033-1043. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.056533

Received 24 July 2024; Accepted 15 November 2024; Issue published 31 December 2024

Abstract

Objectives: This study investigates the association between victimization experience and the tendency to defend on behalf of victims during school bullying incidents in public settings, with a focus on the mediating effect of empathy and the moderating role of school level among Chinese children and adolescents. Methods: Data were collected by a cross-sectional survey. A total of 1491 students in Grades 4–11 participated (Boys = 52.8%; Meanage = 13.00 years, Standard Deviationage = 2.31). Structural equation modeling is employed to test the hypotheses. Results: The results indicate that empathy measures partially mediate the relationship between victimization experience and defending tendency in public in-school bullying situations. In particular, individuals with a history of victimization typically demonstrate lower levels of empathy. They are less likely to protect victims in school bullying situations in the presence of others, which suggests that empathy plays a significant mediating role in this relationship. Group differences were found between primary and secondary school students, which indicates that the hypothesized model should be considered through a developmental perspective. Conclusions: The findings of this study emphasize the importance of children’s benign peer relationships, and practitioners are encouraged to prevent victimization in schools and care for students who have been victimized; specific measures include cultivating empathy, teaching defending skills that have been found to help reduce the adverse effects of victimization, and encouraging prosocial behavior during children's socialization development.Keywords

School bullying is a pervasive issue affecting students worldwide. Recent global estimates indicate that approximately one in three students have been bullied at school [1]. The adverse impact of victimization in school bullying is long-lasting, can significantly impede a student’s mental health [2], and can result in poor academic outcomes [3] and future conduct problems [4]. As a group process, most school bullying happens in a school or classroom context in the presence of bystanders [5]. Defending others in school bullying situations is a manifestation of prosocial behavior that includes actively stopping the bullying behavior, reporting the bullying to teachers and seeking help from others, and comforting the child who was bullied [6]. According to the research established, the actions of peer bystanders are pivotal in shaping the trajectory of school bullying [7]. It has been observed that instances of bullying escalate in frequency when classmates provide reinforcement to the aggressors, whereas interventions that demonstrate solidarity with and defense of the victims tend to mitigate such behaviors [8].

Even though the intervention of bystanders in the event of school bullying is an extremely effective way to put an end to the bullying altogether, studies have shown that children are often passive outsiders who stay away from the situation [6,7,9]. Hawkins et al. [7] revealed that even though approximately 85% of school bullying incidents are observed by peers, only 19% of these cases were defended. The role of the passive outsider may not be neutral, however, because it may signal acquiescence to the bullying behavior [9]. Huang et al. [10] conducted a study in China and also revealed that, when faced with school bullying, as many as 24.75% of students chose passive bystander behaviors. To elucidate the factors influencing peer bystanders’ behavior, numerous studies have investigated the cognitive and contextual factors associated with their intervention or passivity [11–14]. For example, helping the victim of bullying may require moral courage [15], high levels of empathy and self-efficacy [16,17], and being popular [18]. Since a majority of the research has focused on cognitive and contextual factors, relatively little is known about the impact of victimization experiences on the defending tendency, especially in public situations.

Additionally, the occurrences of school bullying are often repetitive, intentional, and due to power imbalances [19]. In this context, children’s defending tendency in school bullying scenarios when others are present may be complicated. In this study, we were particularly interested in peer bystanders’ defending tendency when they witnessed public school bullying and the association thereof with their previous victimization experiences, and we also assessed the underlying mechanism in this relationship.

Victimization experience and defending tendency in public

Adverse experiences influence prosocial behavior, including the defending tendency. According to peer socialization theory, positive, harmonious peer relationships provide children with opportunities to learn prosocial skills and practice prosocial behaviors during their socialization development [20]; this perspective presumes that a child who is well-accepted and cared for by their peers is more likely to behave in a prosocial manner in social contexts than their counterparts who are disliked, isolated, and/or rejected [21]. Victimization, which is a specific type of adverse experience, can result in children forming negative perceptions of their peer relationships; without benign social contacts, victims of school bullying may not have the opportunity and peer resources to learn how to treat others in a prosocial manner, and they are less likely to defend the victims of future school bullying situations when they are bystanders [22].

Previous studies have provided inconsistent findings on the association between victimization and defending tendencies. According to a systematic review of the factors associated with defending tendencies, 58.3% of the extant literature asserts a positive relationship between victimization and defending behavior, while the remaining 41.7% affirmed negative associations between these factors [23]. As a specific example, Pozzoli et al. [24] observed that prior experiences of being victimized positively predicted bystanders’ defending behaviors, yet Nail et al. [25] concluded that victimization was negatively related to defending behaviors. Notably, few studies have investigated the influence of victimization on defending actions in the presence of other bystanders, especially in the Chinese context. Wu et al. [26] made an initial effort to examine the association between defending behaviors and different roles in school bullying incidents using a sample from Taiwan, and even though they ascertained that victims were more likely to defend their peers, the reason for this was unclear. Further research is therefore needed to fully understand how children’s victimization experiences affect their public defending tendencies, and the underlying mechanism that may affect the relationship.

Empathy and defending tendency in public

Empathy refers to an affective state that is produced by comprehending others’ emotional conditions [27]. The impact of empathy on prosocial behaviors has been well-documented by theoretical and empirical evidence over the last few decades [28,29]. Defending peers who are being bullied at school as a type of prosocial behavior has also been determined to be the result of a high level of empathy [14,30,31].

However, little is known about the manner in which empathy affects defending tendencies in public situations, and because most bullying occurs in public places, the relationship between empathy and publicly defending bullied classmates is complicated. Some researchers have asserted that individuals who publicly engage in prosocial behaviors when others are watching are often motivated by potential rewards they could obtain through their intervention, and this rationale is negatively associated with empathy [32,33]. This negative association between empathy and public prosociality was only supported among adults, however, so the influence of empathy on children’s publicly defending tendencies in school bullying situations must therefore be further investigated.

Victimization experience and empathy

Even fewer studies have examined the impact of victimization experience on empathy, and the conclusions thereof were even more inconsistent. Malti et al. [34] posited that children with a history of being victimized typically have fewer friends and view their peers as offensive and distrustful; as a consequence, they may lack the opportunity to properly understand the feelings of other children and become less sensitive to others’ emotions, both of which are important prerequisites of developing empathy. This would suggest that children who have been victimized have reduced levels of empathy. This negative relationship between victimization experiences and empathy was later duplicated in other studies [35–37]. Malti et al. [34] argued, however, that experiences of being bullied may be positively related to a child’s empathy, because victims were usually more sensitive to others’ emotional responses than non-victims because they understand how it feels to be bullied. This conjecture was supported by Caravita et al. [38] who concluded that significant victimization was associated with higher levels of affective empathy. To further complicate the matter, Belacchi et al. [39] and Barhight et al. [40] did not find any significant association between victimization and empathy. This confirms that understanding the relationship between victimization and empathy is far from conclusive.

Based on the definition provided by Davis et al. [41], Olweus et al. [42] differentiated two types of empathy: empathic concern and empathic distress. Empathic concern is the dispositional tendency to experience others’ emotions and feelings, including sympathy, compassion, and concern. Empathic distress differs from empathic concern and focuses on one’s own distressful emotions, rather than those of others; this type of empathy refers to an individual’s emotional reactions when they witness others’ distress (i.e., feelings of discomfort and uneasiness). Because these definitions underscore the notion that both facets of empathy are based on adverse experience and negative emotions, it is reasonable to assume that these types of empathy are related to children’s victimization experiences and defending tendencies. Furthermore, it is important to recognize that not all forms of empathy are inherently positive or lead to prosocial behavior. For instance, as Bloom [43] suggested, being empathic and sharing the feelings of others can sometimes lead individuals to become overly immersed in the suffering of others. This emotional contagion can result in negative emotions that may impair one’s own emotional state and behavior, potentially reducing the likelihood of engaging in prosocial actions. Especially in specific contexts such as school bullying, empathy might cause individuals to resonate with the negative emotions of the victims, leading to a pessimistic and painfully passive state. This form of empathy, rather than motivating action, could paralyze individuals with the weight of the shared misery. These aforementioned counterexamples may be related to the unique dynamics of bullying situations and the varying roles that different types of empathy can play, yet little-to-no research has investigated both types of empathy in a single study to understand the consequences of children’s victimization.

What is also under-investigated is how the school bullying victim’s gender influences bystanders’ defending tendency. Only a few studies have investigated the relation between the gender of the target of the empathy and intervention in bullying [42,44]. For example, Van Noorden et al. [44] found that girls tend to exhibit higher levels of empathy toward other girls; however, their findings did not reflect bystanders’ experiences, nor whether the bullying happened in a public situation. In the present study, we were especially interested in whether empathic concern toward boys or girls and empathic distress uniquely mediated the associations between victimization experiences and children’s defending tendencies in school bullying scenarios.

We examined the mediating role of empathy for three reasons: First, while empathy has been found to be a significant predictor of defending behaviors in school bullying incidents [16], it is unknown whether this effect is applicable when explaining defending-in-public scenarios. Furthermore, even though evidence suggests that a child’s victimization experiences affect their empathy levels, the extent of this influence remains unclear, due to the conflicting results produced by previous studies [36,38,40]. Finally, the manner in which various dimensions of empathy (i.e., empathic concern with different stimulus and empathic distress) and victimization influence defending tendencies in the context of school bullying is unknown and should be clarified to gain a more nuanced understanding of this phenomenon.

In response to the aforementioned research gaps, the aim of the present study is to evaluate the ways in which children’s victimization experiences associate with their defending tendencies in public when they witness a peer being bullied at school and the mediating effects of empathy, especially among Chinese children and adolescents. The study of bystander behavior in school bullying is particularly pertinent among Chinese children and adolescents, given the high prevalence of peer victimization, which is recognized as a significant social issue in China. For instance, a study by Chen et al. [45] reported that a staggering 42.9% of Chinese adolescents had experienced peer victimization. Furthermore, the Chinese cultural emphasis on harmony, known as hexie [46], is deeply ingrained in compulsory education. This cultural value may subtly influence children’s behaviors during the incidents of peer victimization. In the interest of preserving harmony, peer bystanders may be less inclined to intervene, as they aim to de-escalate conflicts and maintain peace. This tendency suggests that the avoidance of conflict involvement could be particularly pronounced in this cultural context. Against this social and cultural background, it becomes essential to examine the model of the present study within the Chinese context, as it may offer insights into the unique dynamics of bystander intervention or inaction among Chinese children and adolescents.

The hypotheses of this study are as follows: H1) Children’s victimization experience is negatively associated with their defending tendency in public in school bullying situations; H2) Children who have been victimized are more likely to exhibit lower levels of empathy (i.e., empathic concern and empathic distress) and, in turn, less likely to defend others in public when they are bystanders in school bullying. This latter hypothesis was informed by Malti et al.’s [34] perception that victimized children often perceive their peers as untrustworthy, and they may struggle to understand others’ feelings and become less sensitive to emotions, hindering their empathy development and consequently making them less likely to defend other victims.

In addition, our study also considers the potential moderating role of school level, drawing on the developmental perspective [47]. It has now been well established by a variety of studies that school level is significantly associated with frequency of victimization [48], level of empathy [49], and likelihood of defending victims in school bullying [14]. Based on this evidence, our study proposes that the school level is a significant moderator due to the variations in social dynamics, cognitive development, and emotional regulation capabilities that occur as children progress through different educational levels. Therefore, we proposed the following final hypothesis: H3) The path coefficients in the mediation model are moderated by children’s school levels. Specifically, we expect to explore differences in these relationships as students move from primary to secondary education, reflecting developmental changes in empathy and prosocial responses to bullying.

A multistage stratified cluster random sampling method was used to administer a questionnaire in three districts of Wuhan, Hubei Province, China—namely Wuchang, Hanyang, and Hongshan—by simple random sampling. The Wuhan Education Bureau provided a comprehensive list of public schools in the three districts, and from each district, one primary school (Grades 4–6), one junior high school (Grades 7–9), and one senior high school (Grades 10–11) were randomly chosen. The participants needed to be in Grade 4 or higher to ensure they could read and understand the questionnaire, and Grade 12 students were excluded to allow them to focus on university entrance exams. In each selected school, one classroom per grade was randomly selected. In all, the questionnaire was completed by 1491 students.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with ethical standards of relevant institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Declaration of Helsinki in 1975, as revised in 2008. The procedures for this study and all consent forms and measurements were approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee in The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Prior to the commencement of the survey, an informed-consent form that included a brief introduction of the study was distributed to each of the students’ parents or guardians, and 88.7% of them approved of their child’s inclusion in the study. These students, whose parents or guardians provided consent, constituted the participants of this research. Before responding to the questionnaires, the participants were informed that their contributions were voluntary and confidential, and they could discontinue their involvement at any time for any reason. The questionnaire was conducted with the entire sample during the after-class period. Clear verbal and written instructions were provided to the participants. The first author of the study and the class’s head teacher were present during data collection, to address any issues or provide assistance if required.

The sample consisted of 1491 students: 788 (52.9%) boys, 693 (46.5%) girls, and 10 (0.6%) respondents who did not report their gender. The students’ ages ranged from 9–18 years, with a mean age of 13.0 years (SD = 2.31). When divided by school level, 514 (34.5%) were elementary school students, 977 (65.5%) were secondary school students. Within the secondary school group, 505 students were from junior high school, and 472 students were from senior high school.

All adopted measures had already been validated in Western societies and were translated by the study authors from English to Chinese and from Chinese to English under the supervision of bilingual professional researchers. Since these measures were not originally designed for the Chinese context, we re-evaluated the validity and reliability of each, and the results indicated that every scale was acceptably constructed, valid, and internally consistent. In addition, as our study specifically focuses on school bullying, we have presented the definition of school bullying at the beginning of the questionnaire. This definition includes the key elements of repetition and power imbalance, which are essential characteristics of bullying.

Victimization experience was measured according to the 7-item scale developed by Hunter et al. [50], which included the following scenarios in which someone could be victimized: “Someone called you names;” “You were threatened by someone;” “Your belongings were stolen/damaged;” “You were left out of games or groups;” “You were hit or kicked;” “Nasty stories were spread about you;” and “You were forced to do something you did not want to do.” The answers reflected the frequency of being treated in the above ways, which were coded as 0 = never; 1 = sometimes; 2 = often; and 3 = always. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the 7-item scale in the present sample was 0.85.

Empathy was tested by Olweus et al.’s Empathic Responsiveness Questionnaire [42], which originally consisted of three subscales: three items for the Girl-as-Stimulus Empathic Concern scale, three items for the Boy-as-Stimulus Empathic Concern scale, and four items for the Empathic Distress scale. Even though the item wording of the first two empathic concern subscales was identical, they each focused on different stimulus objects: “When I see a boy/girl who is hurt, I wish to help him/her;” “Seeing a boy/girl who is sad makes me want to comfort him/her;” “Seeing a boy/girl who can’t find anyone to be with makes me feel sorry for him/her.” The focus of the empathic distress subscale was emotional distress reactions, and we adopted two of the four items on this subscale: “It often makes me distressed when I see something sad on TV;” “Sometimes I feel a bit distressed when I read or hear about something sad.” The other two items—“When I see a boy/girl who is distressed I sometimes feel like crying”—were not included in the present study, because they emphasized crying behavior, which Olweus et al. [42] conceptualized as a relatively strong emotional reaction; moreover, because the exploratory factor analysis results in the present study found that neither of these items were significant indicators in the empathic distress construct, it seemed reasonable to exclude the “crying” items from this study. Each answer was scored within a 5-point range of “1 = not true for me” to “5 = always true for me.” The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.90 for the 8-item questionnaire, 0.89 for the Girl-as-Stimulus Empathic Concern scale, 0.88 for the Boy-as-Stimulus Empathic Concern scale, and 0.84 for the 2-item Empathic Distress scale.

Defending tendency in public was measured according to the public prosocial behavior subscale of the Prosocial Tendencies Measure devised by Carlo et al. [51], which originally included four items that presented four potential scenarios in which an individual might help someone else in a public setting. Since the focus of the present study is school bullying, we added “In school bullying situations,” before each item and adjusted some of the wording to suit this context, resulting in the following four items: “I can defend the victim best when people are watching me”; “It is easier for me to defend the victim when other people are around”; “It is easier for me to defend the victim when it is done in front of other people”; “Defending the victim when I am being watched is when I work best.” The score of each item fell within a 5-point range of “1 = does not describe me at all” to “5 = describes me greatly,” and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the adjusted 4-item scale in the present sample was 0.97.

Control variables include gender and grade level. Gender was coded as 1 = Boy, 0 = Girl. Grade level was from 1 = Grade 4 to 8 = Grade 11. The grade levels were categorized into primary school and secondary school for the purpose of comparing grade-level differences.

The descriptive statistics were initially analyzed using SPSS (Version 26.0) software to provide basic knowledge of the key variables in the present study. To test the hypotheses, structural equation modeling was then performed using Amos (Version 26.0) program. A p-value less than 0.05 is considered to indicate statistical significance.

The following indices were adopted to evaluate the model’s goodness-of-fit: the chi-square index (χ2), the comparative-fit index (CFI), the normed-fit index (NFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Because the likelihood ratio test is sensitive to sample size, it is acceptable to yield a significant χ2 in this study [52]; the CFI and NFI values should be at least 0.95 [53]; and a RMSEA value less than 0.08 suggests a reasonable fit and less than 0.05 suggests a close fit [54]. The mediation effect was assessed using the bootstrapping method with 2000 iterations and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) [55]. The absence of zero in the confidence interval for the indirect effect suggests a significant mediating role. Finally, the model compared primary and secondary school students using a multigroup comparison analysis.

Before conducting model testing, several steps were taken to refine the dataset. Initially, the records of eight participants, comprising less than 5% of the total sample, who had not specified their gender, were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, since the missing data for each variable was <5%, the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm was applied to impute these gaps in the continuous data.

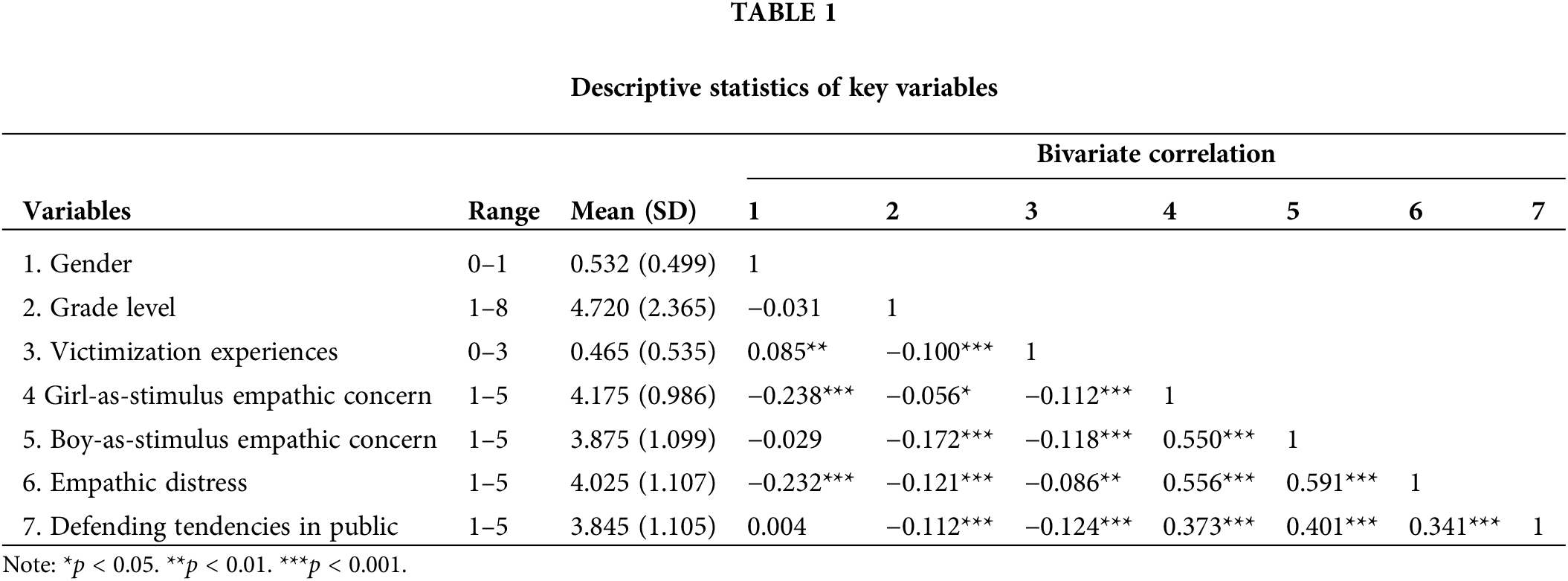

The means (M), standardized deviations (SD), and bivariate correlations are delineated in Table 1. According to the results of bivariate correlations, victimization experiences were negatively correlated with defending tendencies in public (r = −0.124, p < 0.001) and three types of empathy: girl-as-stimulus empathic concern (r = −0.112, p < 0.001); boy-as-stimulus empathic concern (r = −0.118, p < 0.001); and empathic distress (r = −0.086, p < 0.01). Notably, there were significantly positive correlation coefficients between defending tendencies in public and the three empathy subscales (r = ranging from 0.341 to 0.401, p < 0.001).

The goodness-of-fit indices of the measurement model indicated that the model fit the data very well (χ2 = 755.933; df = 142; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.969; NFI = 0.962; RMSEA = 0.054). All observed indicators were loaded on their corresponding latent variables, and the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.499–0.950 and were all greater than the recommended 0.40 criterion [56].

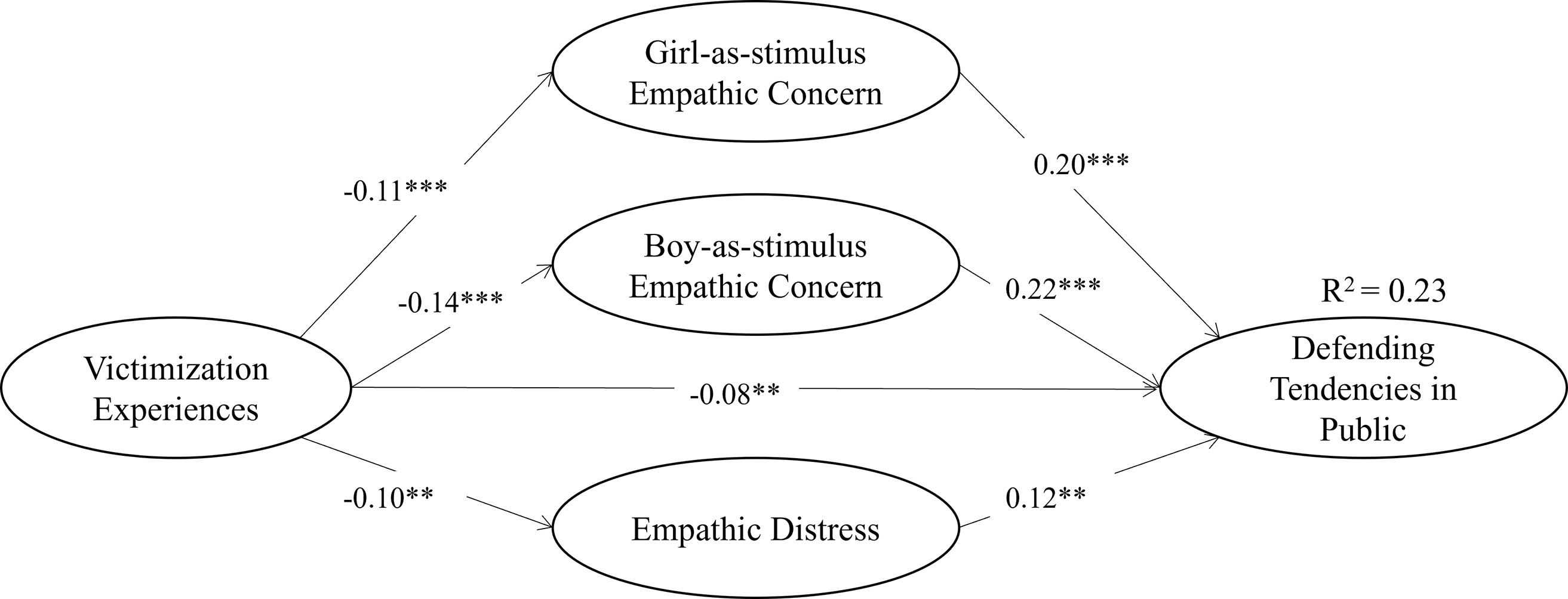

The standardized estimate of the structural model is shown in Fig. 1.1. According to the model-fit indices, the structural model appeared to reasonably fit the data (χ2 = 894.038; df = 170; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.964; NFI = 0.955; RMSEA = 0.054). Overall, the model explains 23.4% of the variances related to defending tendencies in public. Based on the bootstrapping results, the relationship between victimization experience and defending tendencies in public was partially mediated by the aforementioned three types of empathy (Total effect: 95% CI = [−0.167, −0.085], β = −0.15, p < 0.001; Direct effect: 95% CI = [−0.140, −0.026], β = −0.08, p < 0.01; Indirect effect: 95% CI = [−0.094, −0.032], β = −0.06, p < 0.001).

Figure 1: Standardized solutions of the structural model.

Note: **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

In particular, victimization experiences were negatively associated with girl-as-stimulus empathic concern (β = −0.11, p < 0.001), which in turn less likely to defend in public (β = 0.20, p < 0.001); victimization experiences were negatively associated with boy-as-stimulus empathic concern (β = −0.14, p < 0.001) and consequently less likely to defend in public (β = 0.22, p < 0.001); and the association between victimization experiences and empathic distress was also significant—albeit relatively weaker (β = −0.10, p < 0.01)—and eventually significantly associated with defending tendencies in public (β = 0.12, p < 0.01). In addition to the mediation effects of these factors, the negative association between victimization experiences and defending tendencies in public was significant (β = −0.08, p < 0.01).

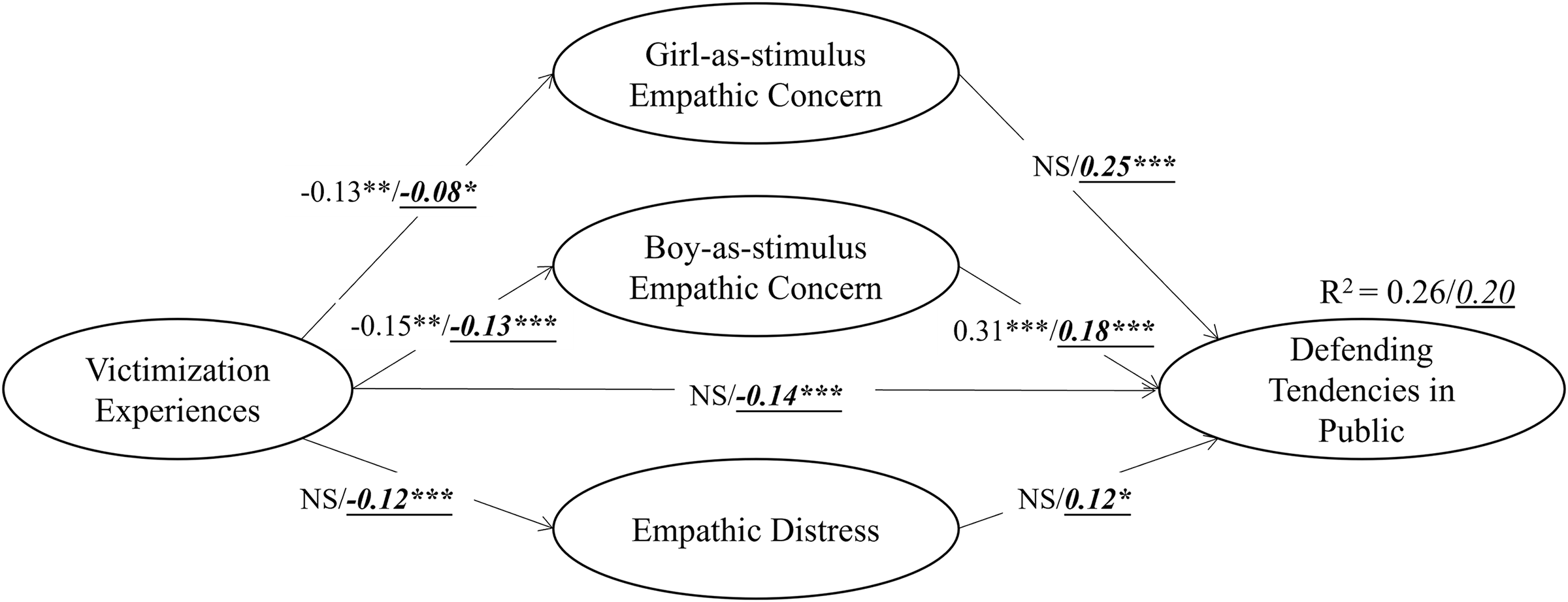

Subsequently, a multigroup analysis was conducted to determine whether the moderating effect of school level was significant across the overall model and specifically on each individual path. By constraining all the path equalities, the model comparison results indicated that the model of primary school students was significantly different from those of the secondary school students (Δχ2 = 20.194, Δdf = 7, p < 0.01). Upon constraining path equalities individually, two pathways exhibited significant variation between primary and secondary school students: the association between the girl-as-stimulus empathic concern and defending tendency in public (Δχ2 = 4.949, Δdf = 1, p < 0.05) and the association between victimization experience and the defending tendency in public (Δχ2 = 6.708, Δdf = 1, p < 0.01).

Finally, separate models were analyzed to examine primary vs. secondary school students (see Fig. 2). Among secondary school students, the pattern of the model’s results was similar to the results for the entire sample (Total effect: 95% CI = [−0.266, −0.120], β = −0.20, p < 0.001; Direct effect: 95% CI = [−0.198, −0.072], β = −0.14, p < 0.001; Indirect effect: 95% CI = [−0.098, −0.022], β = −0.06, p < 0.01): the students’ defending tendency in public was associated with their victimization experiences through the mediation effects of the three domains of empathy. In particular, victimization experiences were negatively associated with girl-as-stimulus empathic concern (β = −0.08, p < 0.05), boy-as-stimulus empathic concern (β = −0.13, p < 0.001), and empathic distress (β = −0.12, p < 0.001), all of which in turn less likely to defend in public (i.e., β = 0.25, p < 0.001; β = 0.18, p < 0.001; β = 0.12, p < 0.05, respectively). However, the model’s results among primary school students showed a different pattern (Total effect: 95% CI = [−0.165, 0.055], β = −0.05, p > 0.05; Direct effect: 95% CI = [−0.111, 0.115], β = 0.01, p > 0.05; Indirect effect: 95% CI = [−0.131, −0.011], β = −0.06, p < 0.05). Among the three domains of empathy, only boy-as-stimulus empathic concern significantly mediated the relationship between victimization experiences and defending tendencies in public (β = −0.15, p < 0.01; β = 0.31, p < 0.001); girl-as-stimulus empathic concern was significantly associated with victimization experiences (β = −0.13, p < 0.01), but its association with defending tendencies in public was not significant; furthermore, empathic distress did not exert a significant mediation effect.

Figure 2: Standardized solutions of the structural model for the primary school students vs. secondary school students.

Notes. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. NS = Not significant. Coefficients in italics represent results for the secondary school students.

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to examine the manner and extent to which children’s victimization experiences affected their defending tendencies in public in the event of bullying situations at school and the mediation of empathy based on a Chinese sample. These study findings will enhance the current understanding of the adverse effect of being victimized and pose considerable implications for educational settings.

The mediation model for the entire sample

The most notable finding of the present study is that the hypothesized model was supported by the data. Specifically, the model revealed that children with a history of victimization tend to have lower levels of empathy and are ultimately less likely to defend their peers when they are being bullied in school, especially when other people are present. The three empathy domains were found to play significant mediating roles in the relationship, and it did not matter whether the stimulus was a boy or a girl.

It should be noted that all three types of empathy exerted significant mediating effects, which indicates that experiences of being victimized could reduce concern for others and distressing feelings and further influenced children’s tendency to defend other bullying victims when they are bystanders. Of the three dimensions of empathy, the mediation effect of boy-as-stimulus empathic concern was relatively stronger than the other two; this may be related to different levels of empathic concern toward boys and girls. As shown in Table 1, the mean of empathic concern toward boys (M = 3.875, SD = 1.099) was relatively lower than empathic concern toward girls (M = 4.175, SD = 0.986), which indicates that the participants were more empathic toward girls; this result is consistent with that of Olweus et al. [42], who administered a questionnaire to Norwegian students. It could therefore be conjectured that those who feel empathy for a boy are more likely to defend than those who feel empathy for a girl; in other words, feeling empathy for a bullied boy can better reflect an individual’s defending motivation.

Victimization, empathy, and defending tendency in public interplay

We documented significantly negative direct and indirect associations between victimization experience and defending tendency in public. This finding supported the assumption of peer socialization theory from a reverse perspective: While children and adolescents need benign peer relationships to obtain opportunities to learn and practice prosocial behavior, undesirable peer relationships may reduce their prosocial tendencies [20–22].

The negative association between victimization and empathy observed in the present study corroborated Malti et al.’s [34] assertion that children who have experienced victimization are more likely to perceive their peers as offensive and untrustworthy and to feel unconcerned to about their and others’ emotions. Likewise, children with victimization experiences are often less empathic toward other bullying victims when they are bystanders. This finding expands the current knowledge by indicating that both empathic concern and empathic distress could be influenced by victimization experience.

Finally, while the positive relationship between empathy and defending tendencies in public in school bullying situations was consistent with the findings of Gini et al. [30] and Van der Ploeg et al. [31]. This result contradicted White’s [33] and McGinley et al. [32] that defending behavior among adults is motivated by potential rewards; this inconsistency may be due to the different target population in this study. This distinction expands the current body of knowledge, suggesting that, unlike adults, children and adolescents’ defending tendencies in public are positively associated with high levels of empathy.

Group differences between primary and secondary school students

Another important finding was that the models’ results differed significantly between primary and secondary school students. The significant differences in model outcomes between primary and secondary school students provide valuable insights into the developmental nature of empathy and its relationship with victimization experiences and defending tendencies. These findings support the Hypothesis 3 (H3) in that the mediation effects of empathy between victimization experiences and public defending tendencies are moderated by the school level of the children. For secondary school students, the presence of significant direct and indirect effects through various types of empathy suggest that empathy plays a complex role in explaining how these adolescents respond to victimization. This aligns with the understanding that older students have more advanced cognitive and emotional capacities, which allow them to process and respond to social situations, such as bullying, with a greater degree of empathy and a propensity to intervene. Conversely, for primary school students, only the boy-as-stimulus empathic concern significantly mediated the relationship between victimization and defending tendencies. This finding indicates that younger students’ empathic responses are more situation-specific and less generalized, possibly due to less developed cognitive empathy and a less mature understanding of social dynamics.

The findings of the group differences could be explained by a number of reasons. First, research has suggested that boys in primary school are more likely to be involved in school bullying—especially in the form of direct physical bullying [57], which usually happens in the classroom or school campus and is relatively easier to identify. Therefore, when faced with boys being bullied, primary school students who have been victimized are less likely to exhibit empathic concern toward bullied boys, and thus less likely to defend other victims in public. The second potential reason is related to the different developmental stages between childhood and adolescence. For instance, one study revealed that significant differences in life satisfaction emerge from the age of 12, with girls exhibiting significantly higher levels of dissatisfaction, depression, and anxiety than boys [58]. This leads us to postulate that, compared to primary school students, adolescents might have greater levels of empathic concern toward girls and empathic distress emerge, and that bystanders are more inclined to intervene in cases of victimization toward girls.

The study findings suggest that children’s experiences of being victimized adversely influence their emotional conditions and behavioral tendencies. Compared to their counterparts, children who have suffered victimization lack the opportunity to feel their and others’ emotions, and they ultimately become incapable of behaving in a prosocial manner, which is a necessary aspect of socialization that they will need in their future life.

Practitioners such as educators and social workers are therefore highly encouraged to prevent victimization in schools and to emphasize the importance of caring for students who have been victimized. Specific measures to take include cultivating children’s empathy for others, helping them to be sensitive to their and others’ emotions, and teaching them useful defense skills that they can use when they become embroiled in future school bullying incidents. For example, the KiVa program in Finland [59,60] employs a multifaceted approach to foster empathy among students. This initiative integrates various engaging methods, including role-playing exercises, collaborative group activities, interactive video games, and film screenings, all designed to enhance students’ capacity for empathy. These diverse strategies aim to provide a comprehensive learning experience that caters to different learning styles and promotes a deeper understanding of empathy’s role in social interactions. Our study’s findings underscore the potential benefits of empathy-focused interventions like the KiVa program in mitigating the adverse effects of victimization and fostering positive social development among children. While such programs have demonstrated efficacy in contexts such as Finland, there is a noted absence of their formal establishment and widespread adoption in China [61]. Our results suggest that introducing and adapting these evidence-based strategies could be profoundly beneficial for Chinese students’ socialization processes.

Furthermore, targeted intervention measures should be implemented for primary and secondary school students. For primary school students, greater emphasis should be placed on boys and include preventing bullying behavior among boys and fostering more empathy toward boys who are bullied. For secondary school students, both boys and girls need to be addressed, with a greater focus on providing care and consolation for the distressing feelings experienced by adolescents who witness bullying incidents.

Even though this study provided remarkable theoretical and practical implications, some limitations should also be noted. First, the nature of the data is cross-sectional, which only allows a limited examination of the causal relationships between variable; a longitudinal design is recommended for future research to verify these results. Second, all the data of this study were collected from Wuhan, a relatively well-developed city in China, so the study results may be limited by not including children from other parts of China, especially rural areas; considering the distinctive living environments, children from rural and urban backgrounds may exhibit different emotional and behavioral conditions, and future investigation should compare children from different backgrounds to more adequately confirm these study findings. Third, the model of our study only includes gender and grade levels as covariates, which are the most commonly used demographic covariates in existing studies [30]. However, it should be noted that bystanders’ defending tendencies in school bullying are a complex psychological process that may be influenced by various cognitive and environmental factors, and future research could consider adding additional variables to the model. Additionally, our research is focused on offline bullying scenarios within school contexts. However, with the rise of technology and the prevalence of cyberbullying as a new form of bullying [62], it is crucial to recognize that our findings may not be directly applicable to online contexts. The dynamics and implications of cyberbullying may introduce unique variables and complexities not captured in our model. Therefore, we suggest that future research should consider adapting our model within the context of cyberbullying to better understand its specific effects.

Based on the findings of this study, we conclude that empathy significantly mediates the relationship between victimization experience and the tendency to defend others in public school bullying situations among Chinese children and adolescents. The data analysis revealed that those who have experienced victimization exhibit reduced empathy and are less likely to engage in defending behavior. Additionally, the study identified developmental differences between primary and secondary school students, suggesting that specific grade-level interventions are necessary to address the complexities of victimization and empathy. In summary, the promotion of empathetic peer relationships is crucial for mitigating the adverse outcomes of victimization and fostering a positive school environment.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant Number 21YBQ005).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Han Xie; formal analysis: Kunjie Cui, Yizhe Jiang; validation and data curation: Yizhe Jiang; investigation: Han Xie, Kunjie Cui; writing—original draft preparation, Han Xie, Yizhe Jiang; writing—review and editing: Kunjie Cui. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with ethical standards of relevant institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Declaration of Helsinki in 1975, as revised in 2008. The procedures for this study and all consent forms and measurements were approved by the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics Committee in The Chinese University of Hong Kong. The approved project title is “Peer bystanders’ defending behavior in school bullying situations”. The ethical approval was obtained during Han Xie’s PhD studies at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Prior to the commencement of the survey, an informed-consent form that included a brief introduction of the study was distributed to each of the students’ parents or guardians, and 88.7% of them approved of their child’s inclusion in the study. These students, whose parents or guardians provided consent, constituted the participants of this research.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1Prior to engaging in the mediation model analysis, we initially tested the direct path relationship between victimization experience and defending tendencies in public, excluding mediators from the model. The results indicated a negative association (β = −0.13, p < 0.001).

References

1. UNESCO. Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Paris, France; 2019. Available from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366486. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

2. Oncioiu SI, Boivin M, Geoffroy MC, Arseneault L, Galéra C, Navarro MC, et al. Mental health comorbidities following peer victimization across childhood and adolescence: a 20-year longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2023;53(5):2072–84. doi:10.1017/S0033291721003822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Xie H, Cui K. Peer victimization, environmental and psychological distress, and academic performance among children in China: a serial mediation model moderated by migrant status. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;133:105850. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Walters GD. Trajectories of bullying victimization and perpetration in Australian school children and their relationship to future delinquency and conduct problems. Psychol Violence. 2021;11(1):19. doi:10.1037/vio0000322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Salmivalli C. Participant roles in bullying: how can peer bystanders be utilized in interventions? Theor Pract. 2014;53(4):286–92. doi:10.1080/00405841.2014.947222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Salmivalli C. Bullying and the peer group: a review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2010;15(2):112–20. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hawkins LD, Pepler DJ, Craig WM. Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Soc Dev. 2001;10(4):512–27. doi:10.1111/sode.2001.10.issue-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kärnä A, Salmivalli C, Poskiparta E, Voeten MJ. Do bystanders influence the frequency of bullying in a classroom. In: The XIth EARA Conference, 2008 May; Turin, Italy. [Google Scholar]

9. Bellmore A, Ma TL, You JI, Hughes M. A two-method investigation of early adolescents’ responses upon witnessing peer victimization in school. J Adolesc. 2012;35(5):1265–76. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.04.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Huang Z, Liu Z, Liu X, Lv L, Zhang Y, Ou L, et al. Risk factors associated with peer victimization and bystander behaviors among adolescent students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(8):759. doi:10.3390/ijerph13080759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Barhight LR, Hubbard JA, Grassetti SN, Morrow MT. Relations between actual group norms, perceived peer behavior, and bystander children’s intervention to bullying. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(3):394–400. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1046180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Campbell M, Hand K, Shaw T, Runions K, Burns S, Lester L, et al. Adolescent proactive bystanding versus passive bystanding responses to school bullying: the role of peer and moral predictors. Int J Bullying Prev. 2020;5:296–305. [Google Scholar]

13. Thornberg R, Pozzoli T, Gini G. Defending or remaining passive as a bystander of school bullying in Sweden: the role of moral disengagement and antibullying class norms. J Interpers. 2022;37(19–20):NP18666–689. [Google Scholar]

14. Xie H, Ngai SS. Participant roles of peer bystanders in school bullying situations: evidence from Wuhan, China. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;110:104762. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pouwels JL, Van Noorden TH, Caravita SC. Defending victims of bullying in the classroom: the role of moral responsibility and social costs. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2019;84:103831. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gini G, Albiero P, Benelli B, Altoe G. Does empathy predict adolescents’ bullying and defending behavior? Aggress Behav. 2007;33(5):467–76. doi:10.1002/ab.v33:5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Longobardi C, Borello L, Thornberg R, Settanni M. Empathy and defending behaviours in school bullying: the mediating role of motivation to defend victims. Brit J Educ Psychol. 2020;90(2):473–86. doi:10.1111/bjep.v90.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Garandeau CF, Vermande MM, Reijntjes AH, Aarts E. Classroom bullying norms and peer status: effects on victim-oriented and bully-oriented defending. Int J Behav Dev. 2022;46(5):401–10. doi:10.1177/0165025419894722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kaufman TM, Huitsing G, Veenstra R. Refining victims’ self-reports on bullying: assessing frequency, intensity, power imbalance, and goal-directedness. Soc Dev. 2020;29(2):375–90. doi:10.1111/sode.v29.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hartup WW. Friendships and their developmental significance. In: McGurk H, editor. Childhood social development. Hove, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2022. p. 175–205. [Google Scholar]

21. Wentzel KR, McNamara CC. Interpersonal relationships, emotional distress, and prosocial behavior in middle school. J Early Adolesc. 1999;19(1):114–25. doi:10.1177/0272431699019001006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wei HS, Williams JH. Relationship between peer victimization and school adjustment in sixth-grade students: investigating mediation effects. Violence Vict. 2004;19(5):557–71. doi:10.1891/vivi.19.5.557.63683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lambe LJ, Della Cioppa V, Hong IK, Craig WM. Standing up to bullying: a social ecological review of peer defending in offline and online contexts. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019;45:51–74. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Pozzoli T, Gini G, Vieno A. The role of individual correlates and class norms in defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: a multilevel analysis. Child Dev. 2012;83(6):1917–31. doi:10.1111/cdev.2012.83.issue-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Nail PR, Simon JB, Bihm EM, Beasley WH. Defensive egotism and bullying: gender differences yield qualified support for the compensation model of aggression. J Sch Violence. 2016;15(1):22–47. doi:10.1080/15388220.2014.938270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wu WC, Luu S, Luh DL. Defending behaviors, bullying roles, and their associations with mental health in junior high school students: a population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1. [Google Scholar]

27. Eisenberg N, Miller PA. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol Bull. 1987;101(1):91–119. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Marshall SL, Ciarrochi J, Parker PD, Sahdra BK. Is self-compassion selfish? The development of self-compassion, empathy, and prosocial behavior in adolescence. J Res Adolesc. 2020;30:472–84. doi:10.1111/jora.v30.s2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Paciello M, Fida R, Cerniglia L, Tramontano C, Cole E. High cost helping scenario: the role of empathy, prosocial reasoning and moral disengagement on helping behavior. Pers Indiv Differ. 2013;55(1):3–7. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Gini G, Albiero P, Benelli B, Altoe G. Determinants of adolescents’ active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying. J Adolesc. 2008;31(1):93–105. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Van der Ploeg R, Kretschmer T, Salmivalli C, Veenstra R. Defending victims: what does it take to intervene in bullying and how is it rewarded by peers? J School Psychol. 2017;65:1. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2017.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. McGinley M, Carlo G. Two sides of the same coin? The relations between prosocial and physically aggressive behaviors. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36:337–49. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9095-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. White BA. Who cares when nobody is watching? Psychopathic traits and empathy in prosocial behaviors. Pers Indiv Differ. 2014;56:116–21. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Malti T, Perren S, Buchmann M. Children’s peer victimization, empathy, and emotional symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2010;41:98–113. doi:10.1007/s10578-009-0155-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Kokkinos CM, Kipritsi E. The relationship between bullying, victimization, trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy among preadolescents. Soc Psychol Educ. 2012;15:41–58. doi:10.1007/s11218-011-9168-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Williford A, Boulton AJ, Forrest-Bank SS, Bender KA, Dieterich WA, Jenson JM. The effect of bullying and victimization on cognitive empathy development during the transition to middle school. Child Youth Care For. 2016;45(4):525–41. doi:10.1007/s10566-015-9343-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wong DS, Chan HC, Cheng CH. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;36:133–40. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.11.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Caravita SC, Di Blasio P, Salmivalli C. Early adolescents’ participation in bullying: is ToM involved? J Early Adolesc. 2010;30(1):138–70. doi:10.1177/0272431609342983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Belacchi C, Farina E. Feeling and thinking of others: affective and cognitive empathy and emotion comprehension in prosocial/hostile preschoolers. Aggress Behav. 2012;38(2):150–65. doi:10.1002/ab.2012.38.issue-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Barhight LR, Hubbard JA, Hyde CT. Children’s physiological and emotional reactions to witnessing bullying predict bystander intervention. Child Dev. 2013;84(1):375–90. doi:10.1111/cdev.2013.84.issue-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Davis MH, Luce C, Kraus SJ. The heritability of characteristics associated with dispositional empathy. J Pers. 1994;62(3):369–91. doi:10.1111/jopy.1994.62.issue-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Olweus D, Endresen IM. The importance of sex-of-stimulus object: age trends and sex differences in empathic responsiveness. Soc Dev. 1998;7(3):370–88. doi:10.1111/sode.1998.7.issue-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bloom P. Against empathy: the case for rational compassion. London, UK: Random House; 2017 Feb 2. [Google Scholar]

44. Van Noorden TH, Cillessen AH, Haselager GJ, Lansu TA, Bukowski WM. Bullying involvement and empathy: child and target characteristics. Soc Dev. 2017;26(2):248–62. doi:10.1111/sode.2017.26.issue-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Chen QQ, Chen MT, Zhu YH, Chan KL, Ip P. Health correlates, addictive behaviors, and peer victimization among adolescents in China. World J Pediatr. 2018;14:454–60. doi:10.1007/s12519-018-0158-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Lian Z, Oliver G. Information culture: a perspective from Mainland China. J Doc. 2020;76(1):109–25. [Google Scholar]

47. Volk AA, Dane AV, Al-Jbouri E. Is adolescent bullying an evolutionary adaptation? A 10-year review. Educ Psychol Rev. 2022;34(4):2351–78. doi:10.1007/s10648-022-09703-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Kennedy RS. Bullying trends in the United States: a meta-regression. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021;22(4):914–27. doi:10.1177/1524838019888555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Farrell AH, Volk AA, Vaillancourt T. Empathy, exploitation, and adolescent bullying perpetration: a longitudinal social-ecological investigation. J Psychopathol Behav. 2020;42(3):436–49. doi:10.1007/s10862-019-09767-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Hunter SC, Boyle JM. Appraisal and coping strategy use in victims of school bullying. Brit J Educ Psychol. 2004;74(1):83–107. doi:10.1348/000709904322848833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Carlo G, Randall BA. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2002;31:31–44. doi:10.1023/A:1014033032440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

53. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol Methods Res. 1992;21(2):230–58. doi:10.1177/0049124192021002005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015 Jan 7. [Google Scholar]

57. Morgan PL, Woods AD, Wang Y, Farkas G, Oh Y, Hillemeier MM, et al. Which children are frequently victimized in US elementary schools? Population-based estimates. School Ment Health. 2022;14(4):1011–23. doi:10.1007/s12310-022-09520-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Aymerich M, Cladellas R, Castelló A, Casas F, Cunill M. The evolution of life satisfaction throughout childhood and adolescence: differences in young people’s evaluations according to age and gender. Child Indic Res. 2021;14(6):2347–69. doi:10.1007/s12187-021-09846-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Garandeau CF, Laninga-Wijnen L, Salmivalli C. Effects of the KiVa anti-bullying program on affective and cognitive empathy in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2022;51(4):515–29. doi:10.1080/15374416.2020.1846541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Salmivalli C, Poskiparta E. KiVa antibullying program: overview of evaluation studies based on a randomized controlled trial and national rollout in Finland. Int J Confl Violence. 2012;6(2):293–301. [Google Scholar]

61. Jiang Y. The way to help Chinese bullied children?. In: Proc of the 2nd Int Conf on Culture, Design Social Devel (CDSD 2022), 2023 Mar 1; Nanjing, China: Atlantis Press; p. 131–38. Available from: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/cdsd-22/125984881. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

62. Li C, Wang P, Martin-Moratinos M, Bella-Fernandez M, Blasco-Fontecilla H. Traditional bullying and cyberbullying in the digital age and its associated mental health problems in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adoles Psy. 2024;33(9):2895–909. doi:10.1007/s00787-022-02128-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools