Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effect of Father Absence on Gratitude and Forgiveness: The Mediating Role of Resilience

1 Teacher Education College, Hunan City University, Yiyang, 413000, China

2 Department of Psychology, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410000, China

3 School of Teacher Education, Nanjing Xiaozhuang University, Nanjing, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaojun Li. Email:

# These authors are the co-first authors

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(12), 1025-1032. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.028301

Received 12 December 2022; Accepted 26 April 2023; Issue published 31 December 2024

Abstract

Background: Father absence has long been a popular issue in psychology due to its influence on adolescent well-being and development. Empirical studies have demonstrated the detrimental effects of father absence, such as disruptions in prosocial qualities like gratitude and forgiveness. However, the mediating factor between them remains unclear. Hence, this study aims to explore the mediating role of resilience in the influence of father absence on gratitude and forgiveness. Methods: 1951 participants completed the Revision of the Father Absence Questionnaire, the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, the Gratitude Questionnaire–6 and the Tendency to Forgive Scale. Harman single factor test was conducted followed by confirmatory factor analysis to assess the data for potential common method deviation. Results: The results showed that: Father absence was negatively associated with gratitude and forgiveness. Moreover, we found that resilience mediated between father absence and gratitude and forgiveness. Conclusion: The findings demonstrate that the undesirable effects of father absence on prosocial qualities may be ameliorated by intervening in the mediating factor among them. In other words, improving the resilience of individuals with paternity deficiency may help improve their gratitude and forgiveness, which is of great significance for the intervention of prosocial quality in individuals with paternity deficiency.Keywords

In the realm of family life, the role of fathers holds significant importance in individuals’ development. Krampe and Edythe’s theory of father presence [1] underscores the essentiality of a father’s involvement in this context. The theory posits that father presence refers to a father’s psychological presence in a child’s life, encompassing emotional proximity and availability, indicative of a favorable mental state. Extensive evidence has demonstrated that a high-quality father presence positively impacts children’s mental well-being. Conversely, father absence, the opposite of father presence, has become a pervasive concern in societal development. A multitude of studies have consistently linked father absence to a range of emotional and behavioral issues [2], encompassing anxiety, depression, other negative emotions [3–6], as well as antisocial behavior [7], psychological disorders [8] and interpersonal distress [9,10]. Moreover, father absence can even influence the development of of key personality traits in individuals [11,12]. Moreover, during the process of personality development, certain prosocial qualities like gratitude and forgiveness play a crucial role in socialization [13]. Consequently, this study aims to investigate the relationship between father absence and gratitude and forgiveness, as well as the mediating mechanism of resilience. Exploring this issue will contribute to a clearer understanding of the pivotal role fathers play in nurturing prosocial qualities.

Gratitude is widely acknowledged as a virtuous trait [14] characterized by individuals expressing appreciation for others’ assistance and engaging in spontaneous acts of altruism [15]. Prosocial behavior heavily relies on gratitude [16], as it not only strengthens interpersonal bonds but also enriches the quality of social relationships [17]. Previous research has extensively examined the determinants of gratitude, primarily from the perspective of interactions and relationships. For example, Wu et al. [18] demonstrated that a positive parent-child relationship significantly predicts the development of gratitude. Additionally, studies have highlighted the significant benefits of family-centered parenting styles, particularly those emphasizing emotional warmth, in fostering gratitude, while negative parenting styles such as parental rejection have been found to hinder its development [19]. Hence, both the parent-child relationship and parenting styles reflect parental attitudes, and the quality of parental care emerges as a crucial factor in gratitude formation. However, existing studies have predominantly focused on the impact of maternal care, paying scant attention to the influence of paternal affection. Addressing this research gap, the present study aims to investigate the effect of father absence on the formation of gratitude.

Furthermore, an extensive body of research has established the significant influence of family relationships, specifically the parent-child relationship and parenting styles, on the development of forgiveness. Forgiveness entails the voluntary demonstration of empathy by victims towards aggressors following harm, wherein they refrain from hostility and instead exhibit acts of kindness [20]. Notably, the quality of the parent-child relationship has been found to have a direct correlation with higher levels of forgiveness among adolescents, as demonstrated by Christensen et al. [21]. Additionally, Wang et al. [22] discovered that children raised by parents utilizing democratic parenting styles display a more pronounced tendency towards forgiveness. In light of these findings, our study aims to investigate the causal mechanism between father absence and two fundamental personality traits: gratitude and forgiveness. Accordingly, we posit Hypothesis 1: father absence predicts decreased levels of gratitude and forgiveness.

Resilience refers to an individual’s capacity to endure and adapt to significant disruptions while exhibiting minimal negative behavior [23]. The resilience framework posits that the ability of “high-risk” children facing prolonged adversity to adapt to challenging environments or stressors depends on both external pressure or challenge and their internal resilience [24]. Empirical investigations have shown that resilience can effectively mitigate the impact of adverse childhood experiences on negative emotions and behaviors. For instance, previous studies have demonstrated that resilience can alleviate the detrimental effects of childhood emotional abuse and family dysfunction on anxiety and depression [25–28]. Furthermore, resilience can serve as a mediator to suppress the adverse impact of childhood abuse on aggression [29]. Additionally, resilience can inhibit the unfavorable effects of challenging environments on the development of an individual’s personality traits. For instance, Friborg et al. [30] found that resilience predicts the development of personality traits such as extroversion and responsibility in the face of adversity. Considering that father absence constitutes a crucial aspect of an unfavorable early-life environment, we propose Hypothesis 2: enhancing the resilience of individuals experiencing father absence may bolster their gratitude and forgiveness.

In conclusion, the present study seeks to explore the relationship between father absence and gratitude, as well as forgiveness, while considering the mediating role of resilience, drawing upon the theoretical framework explicated earlier. Our specific hypothesis posits that father absence will be directly and indirectly associated with decreased levels of gratitude and forgiveness, with resilience serving as a mediating mechanism.

In this study, 1951 adolescents from several primary and secondary schools in Central China were selected using cluster sampling methodology. The sample consisted of 669 primary school students, 723 junior high school students and 559 senior high school students. There were 995 males and 956 female participants, with an average age of 12.93 ± 2.54 years (range, 8–19 years). All participants were free from any physical or psychological illnesses and provided written informed consent before completing the questionnaires. Detailed instructions were provided to the participants, who completed all the questionnaires within approximately 40 min. As a token of appreciation for their participation, all participants received a compensation of ¥30. The present study received ethical approval from the Academic Committee of the School of Psychology of Hunan Normal University (Grant Number: 2021051; Grant date: 2023.3.5).

The present study employed questionnaires consisting of 4 sub-questionnaires: the Father Absence Questionnaire, the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, the Gratitude Questionnaire–6 and the Tendency to Forgive Scale.

Revision of the father absence questionnaire (FAQ)

The 27-item Revised of the Father Absence Questionnaire (FAQ) was employed to assess the construct of father absence [31,32]. The questionnaire comprises of seven subscales designed to evaluate diverse aspects, including individuals’ sentiments towards their fathers, mother’s relationship with her own father, the dynamics between the father and mother and so on. Each item was scored on a Likert 5-point scale, providing a range of response options. Prior research has established the scale’s reliability and validity within the Chinese population. Within the context of our study, the FAQ exhibited a notably high level of internal consistency, as indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.911.

Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC)

The level of resilience was measured using the the 10-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [33,34]. The CD-RISC is a well-established instrument designed to assess an individual’s resilience. One example item from the scale includes the statement “able to cope with anything”. Participants responded to each item on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Higher scores on the scale indicate a greater level of resilience. The reliability and validity of the CD-RISC have been established within the Chinese population. In our study, the CD-RISC demonstrated a high level of internal consistency, as evidenced by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.880.

Gratitude questionnaire–6 (GQ-6)

The level of gratitude was assessed using the 6-item Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6) [35,36]. The GQ-6 is a validated instrument employed to measure gratitude. Participants responded to each item on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Notably, the third and sixth items were reverse-scored. Higher scores indicate a greater level of gratitude. The validity and reliability of this version of the GQ-6 have been demonstrated in previous studies conducted with Chinese samples [37,38]. In our study, the GQ-6 exhibited acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.684.

Tendency to forgive scale (TTF)

In this study, forgiveness was assessed using the Chinese version of the Tendency to Forgive Scale (TTF), which underwent a rigorous translation process following the standard forward-and-back translation approach [39]. The TTF scale has been widely utilized in prior studies conducted among Chinese populations [40,41], demonstrating robust levels of reliability and validity [39]. To measure the level of forgiveness, we employed the 4-item TTF, with one example item being “my approach is just to forgive and forget when people wrong me” [42]. Participants responded to each item on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (indicating strong disagreement) to 7 (indicating strongly agreement). Notably, the second item was scored in reverse. Higher scores on the TTF indicate a greater degree of forgiveness. In our study, the TTF exhibited acceptable internal consistency, as demonstrated by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.729.

Firstly, a Harman single factor test was conducted followed by confirmatory factor analysis to assess the data for potential common method deviation. To evaluate the goodness of fit, the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) and comparative fit index (CFI) were selected as indicators for the model [43]. Secondly, Amos 26.0 was utilized to construct a measurement model. Using the project construction balance method, father absence was divided into two dimensions, resilience into three dimensions, gratitude into six dimensions, and forgiveness into four dimensions as indicators of influencing factors. If the measurement model demonstrated good fit, a structural equation model was planned for construction. Subsequently, the mediating effect of resilience between father absence and gratitude and forgiveness was examined using the bootstrap method. Finally, the data was into male and female groups to assess the stability of the structural model across genders.

Measurement model verification

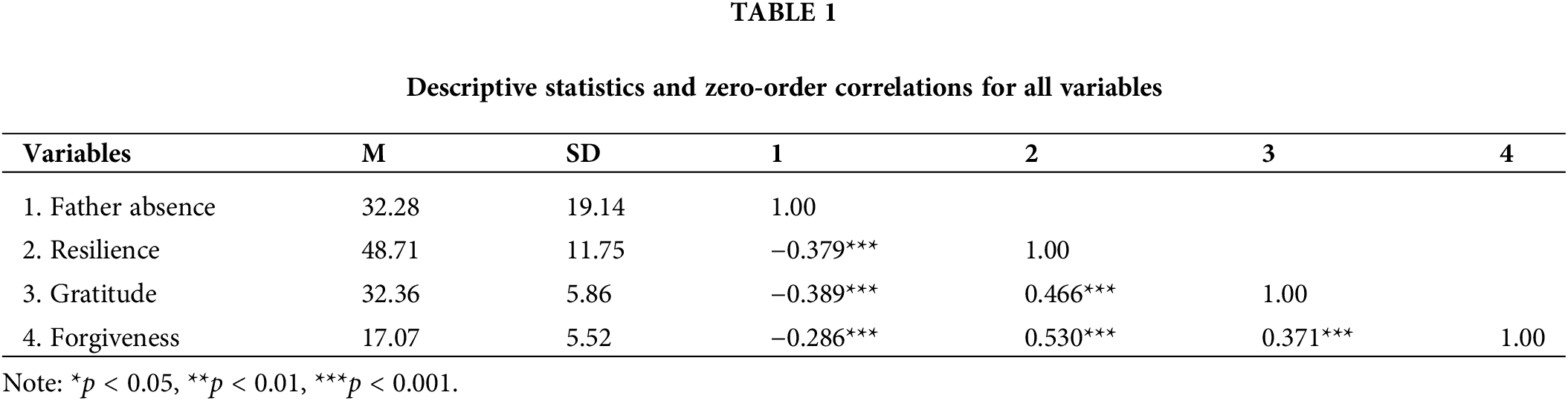

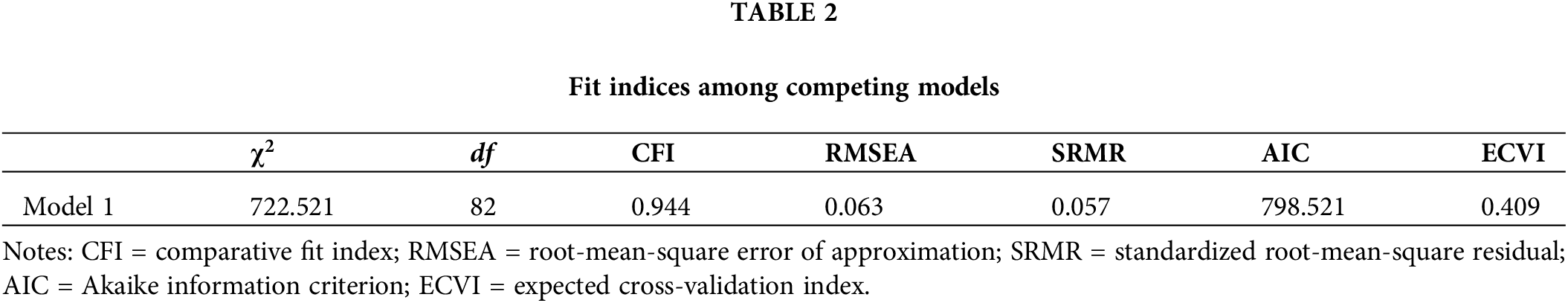

Four key variables, namely father absence, resilience, gratitude, and forgiveness, were incorporated into our comprehensive measurement model. The results revealed a favorable fit of the data to the measurement model [χ2 (82,1951) = 722.521, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.063; SRMR = 0.057; CFI = 0.944], signifying the model’s suitability for the data. Additionally, all potential variables demonstrated significant and substantial factor loading (p < 0.001), indicating that the selected variables effectively represented the observed variables. Detailed information on the average, standard deviation, and correlations of father absence, resilience, gratitude, and forgiveness, along with the intercorrelations between these variables, are presented in Table 1. Notably, significant correlations were observed among the main variables, aligning with theoretical expectations and providing initial support for the research hypotheses.

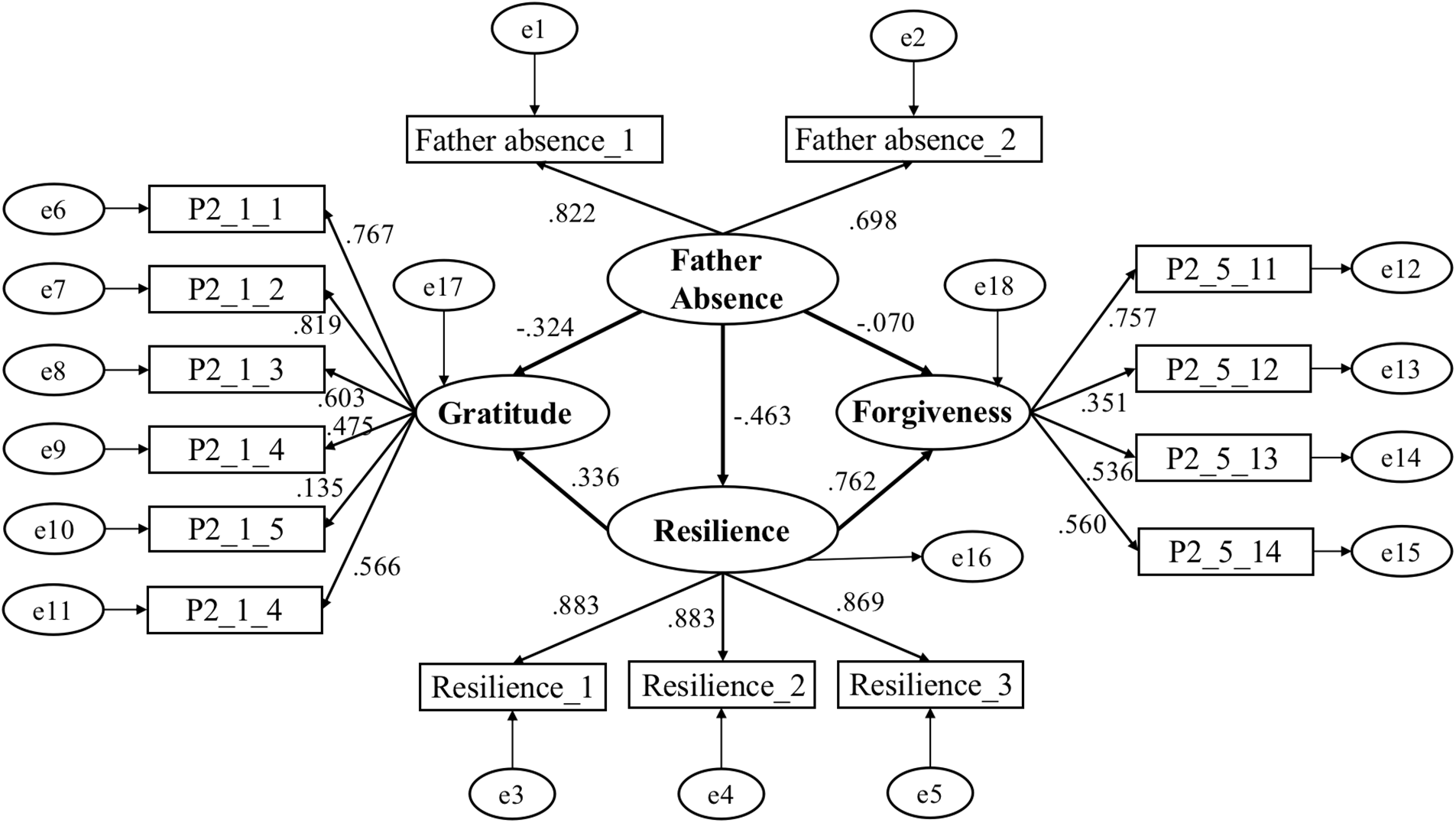

First, father absence significantly and directly predicted gratitude and forgiveness without considering the mediating role of resilience. Subsequently, Model 1 was established, encompassing direct paths from father absence to gratitude and forgiveness, as well as indirect paths mediated by resilience (see Fig. 1). The results showed that Model 1 exhibited superior fit compared to alternative models [χ2 (82,1951) = 722.521, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.063; SRMR = 0.0574; CFI = 0.944] (see Table 2). Consequently, Model 1 was selected as the final structural model.

FIGURE 1: The structural model of father absence, resilience, gratitude and forgiveness (N = 1951).

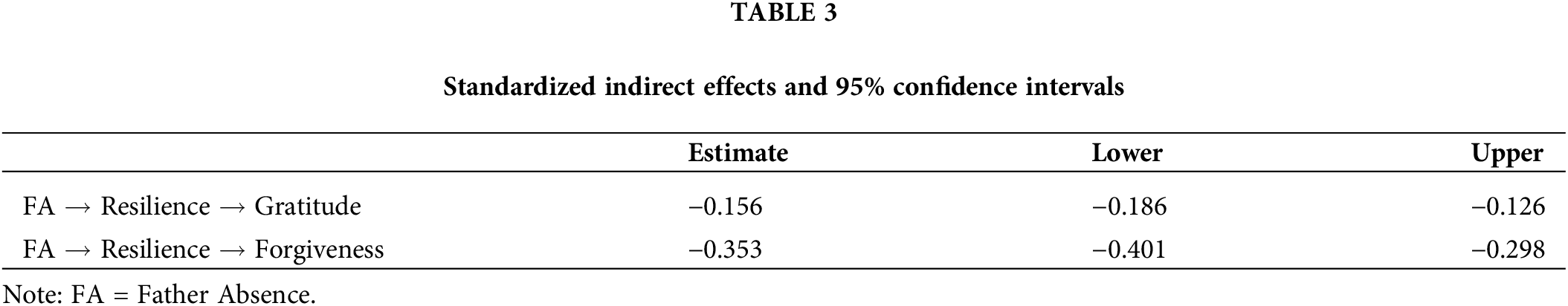

In addition, the mediating effect of resilience between father absence and gratitude, as well as father absence and forgiveness in Model 1, was examined using the bootstrap method. A total of 2000 bootstrap samples were randomly selected from the original dataset (N = 1951). The results indicated that, at the 95% confidence interval, exhibited a significant indirect effect in the relationship between father absence and gratitude [−0.186, −0.126], as well as between father absence and forgiveness [−0.401, −0.298] (see Table 3).

Furthermore, the stability of the model was assessed across genders. Initially, gender differences in the four latent variables were examined. The results showed that there were no significant gender differences in father absence [t(1951) = −1.915, p > 0.05], gratitude [t(1951) = −0.820, p > 0.05] and forgiveness [t(1951) = 1.586, p > 0.05]. However, a significant gender difference was observed in resilience [t(1951) = 5.695, p < 0.05], with males exhibiting higher scores compared to females.

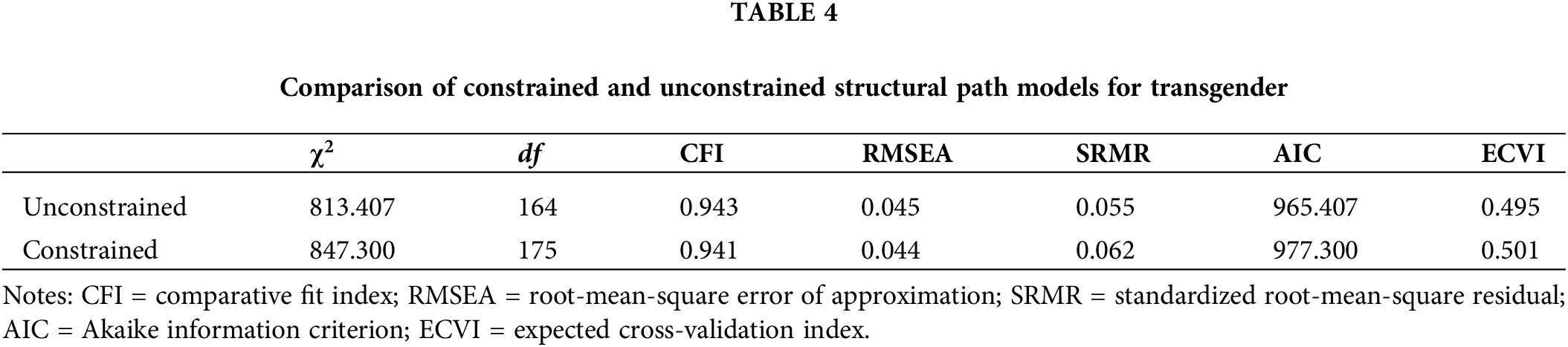

To assess the stability of the model across genders, a multi-group analysis was conducted in accordance with Byrne’s [44] recommendations. Two models were established, with basic parameters including factor load, error variance, and structural covariance unchanged. In one model, unconstrained structural paths were freely assessed for cross-gender analysis, while the other model imposed constrained structural path coefficients to be equal across genders. The results indicated significant differences between the two models [χ2 = 33.893, p < 0.001]. However, both models demonstrated satisfactory fitness indices, meeting the standard criteria (see Table 4). To further investigate the cross-gender stability of the structural model, the critical ratio of differences (CRD) between the two models was employed as an index. Considering that χ2 can be impacted by large sample sizes, the absolute value of CRD greater than 1.96 was used to determine statistically significant differences [45]. The results indicated no significant differences in the structural paths of all variables (CRD father absence→resilience = −0.160, CRD father absence→gratitude = 0.563, CRD father absence→forgiveness = 0.506, CRD resilience→gratitude = −1.536, CRD resilience→forgiveness = 1.226). Thus, it can be concluded that there were no significant differences in cross-gender comparisons between the two models, indicating cross-gender stability of the model.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between father absence and the prosocial qualities of gratitude and forgiveness, while also examining the mediating role of resilience integrating resilience theory for the first time. The findings of this study revealed a negative impact of father absence on the development of gratitude and forgiveness. In addition, the results indicated that father absence indirectly influenced gratitude and forgiveness through the mediating mechanism of resilience. In other words, enhancing the resilience of individuals who have experienced father absence may contribute to the improvement of their gratitude and forgiveness. These findings hold significant implications for interventions targeting the enhancement of prosocial qualities among individuals affected by father absence.

Firstly, the findings of this study provide support for Hypothesis 1, indicating that father absence has a negative predictive effect on gratitude and forgiveness. This suggests that individuals who have experienced father absence may exhibit lower levels of gratitude and forgiveness compared to those who have not experienced such absence. These results align with previous research and underscore the significant role of fathers in the development of individuals [46]. Adverse childhood experiences, including father absence, have been associated with impaired social development [47] and emotional development [48]. For instance, such experiences may lead to difficulties in emotion regularity [48] and impairing children’s social-emotional function [49]. Father absence represents a prototypical adverse childhood experience [50] and can impose detrimental effect on the development of prosocial qualities [51]. Children growing up in father-absence environments often exhibit insecure attachment patterns [52,53], which can contribute to challenges in interpersonal interaction [54] and an increased likelihood of displaying self-centered tendencies [55]. Consequently, developing the capacity for gratitude and forgiveness becomes more arduous. However, a nurturing environment can foster children’s prosocial qualities [56], with fathers playing a pivotal role in establishing such an environment within the family context. Typically, children growing up in supportive family environments tend to experience greater care [57,58] and are more likely to extend this care towards others, displaying a propensity for empathy and considering others’ perspectives [59]. Consequently, these individuals find it easier to cultivate gratitude and forgive others for their harmful behaviors. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that father absence detrimentally affects individuals’ moral development [60], while gratitude and forgiveness are are hallmark moral qualities [61–63]. Hence, father absence can directly influence the development of gratitude and forgiveness.

Secondly, our findings provide empirical support for hypothesis 2, which suggests that resilience plays a pivotal role in mediating the relationship between father absence and gratitude as well as forgiveness. Prior research has emphasized the significance of a supportive environment for children in fostering resilience [64]. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that adverse experiences such as childhood trauma and insufficient parental care can impede the adaptive capacity of individuals, thus exerting a detrimental impact on their resilience [65]. In the case of individuals who experience father absence, they are exposed to a family environment characterized by loss, which hampers their ability to receive adequate care and educational support from their fathers, consequently impeding the fulfillment of their emotional needs [66]. Consequently, their physical and mental well-being may be compromised [67]. These negative consequences can further undermine their ability to navigate and cope with adversities, ultimately diminishing their level of resilience [68–71]. Conversely, our results showed that resilience can positively predict the two prosocial qualities—gratitude and forgiveness—thus reinforcing the concept of resilience [72]. This positive association could be attributed to the notion that individuals with high levels of resilience possess superior interpersonal skills and psychological adaptability [73], granting them an advantage in social interactions. Consequently, they are more likely to receive support and assistance from others [74]. This enhanced social support, in turn, prompts a greater willingness among these individuals to reciprocate the kindness extended by others [75,76] and exhibit forgiveness towards aggressive behaviors directed at them [77]. Consequently, individuals with high resilience develop higher levels of gratitude and forgiveness [78]. In summary, our study underscores the role of resilience as a mediator between father absence and gratitude as well as forgiveness.

As the prevalence of single mother families continues to rise, it becomes increasingly crucial to comprehend the mechanisms through which father absence can detrimentally impact children’s development. In light of this, our study aims to shed light on the relationship between father absence and two key prosocial qualities—gratitude and forgiveness—by examining the mediating role of resilience. Our findings unequivocally demonstrate that children raised in father-absent families exhibit lower levels of gratitude and forgiveness. Specifically, this study adopts a resilience theory framework to elucidate the influence of father absence on these qualities and the results confirm a substantial and negative correlation between father absence and both gratitude and forgiveness. However, it is worth noting that the magnitude of this effect is contingent upon the presence of resilience. This implies that although father absence may indeed hinder the development of gratitude and forgiveness, cultivating inner strength—resilience—plays a pivotal role in ensuring continued growth despite adversities.

This study also has some limitations. Firstly, cross-sectional study is not sufficient enough to establish a true cause and effect relationship. Secondly, employing self-report questionnaires introduces the potential for validity issues, as participants may be inclined to provide socially desirable responses rather than honest ones. Thirdly, this study relied on convenience sampling, which may introduce sampling bias and limit the generalizability of the findings. To address these limitations, it is advisable to incorporate longitudinal designs that can capture temporal associations. Additionally, a combined approach utilizing both cross-sectional and longitudinal methodologies could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic. Furthermore, employing a more rigorous sampling strategy to ensure a representative sample would enhance the external validity of the findings.

Acknowledgement: We thank Ziyuan Chen, Rong Yuan, Wenrui Zhang, Qingyin Li, and Ying Xue for their useful advice on writing.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by grants from the project The Study on the Impact of Father Love Absence on the Development of Adolescent Moral Sensitivity and Countermeasures (23BSH144).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Rui Hu, Yanhui Xiang, Xiaojun Li; data collection: Hui Chen, Yanhui Xiang; analysis and interpretation of results: Rui Hu, Hui Chen, Xiaojun Li; draft manuscript preparation: Rui Hu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used in this study is not publicly available due to confidentiality and legal restrictions. We do not have the right to openly release the data as it contains sensitive information and is subject to privacy and ethical considerations. However, we would like to clarify that while we cannot openly share the data, we retain the right to use it for research purposes in accordance with the terms and conditions of our data access agreement. If there is a specific need for the data for purposes such as replication, further analysis, or verification of results, interested parties may contact the corresponding author to discuss the possibility of obtaining access to the data, subject to the necessary ethical and legal approvals. We are committed to upholding the principles of transparency and scientific rigor, and we will make every effort to facilitate access to the data within the constraints of the agreements and regulations governing its use. Please contact YanHui Xiang at xiangyh@hunnu.edu.cn for inquiries regarding data access. We appreciate your understanding of the limitations related to data availability in this study and thank you for your interest in our research.

Ethics Approval: This study involved human subjects and was conducted in accordance with ethical standards and guidelines. The present study was approved by the Academic Committee of Hunan Normal University. All participants provided written informed consent before completing the questionnaires and were paid after completing the whole questionnaires (Grant Number: 2021051; Grant Date: 2023.3.5).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Krampe EM. When is the father really there? J Fam Issues. 2009;30(7):875–97. [Google Scholar]

2. Carlson MJ, Corcoran ME. Family structure and children’s behavioral and cognitive outcomes. J Marriage Fam. 2001;63(3):779–92. [Google Scholar]

3. Yulan C, Yan D, Hong C, Ting Y. Influence of father’s parenting on mental health development of middle school students. Chin Sch Health. 2015;36(11):1728–31. [Google Scholar]

4. Chung J, Lam K, Ho K, Cheung A, Ho L, Gibson F, et al. Relationships among resilience, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(13–14):2396–405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Culpin I, Heron J, Araya R, Melotti R, Joinson C. Father absence and depressive symptoms in adolescence: findings from a UK cohort. Psychol Med. 2013;43(12):2615–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Jensen PS, Grogan D, Xenakis SN, Bain MW. Father absence: effects on child and maternal psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28(2):171–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Pfiffner LJ, Mcburnett K, Rathouz PJ. Father absence and familial antisocial characteristics. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2001;29(5):357–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Flouri E, Buchanan A. The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. J Adolescence. 2003;26(1):63–78. [Google Scholar]

9. Yulan C, Yingping W, Qian Z. Influence of father’s parenting involvement on healthy personality of college students. Chin Sch Health. 2016;37(4):550–3. [Google Scholar]

10. Qiongyao Z, Ping H, Huiyun H, Guolai W. The effect of father presence on social adaptation behavior of high-school students’ mediation and moderation effect. Stud Physiol Behav. 2017;15(6):786. [Google Scholar]

11. Plasc ID. Growing up in a single-parent family and anger in adulthood. J Loss Trauma. 2016;21(4):259–64. [Google Scholar]

12. Shaohua P, Xiaoyang D, Ning L. Relationship between father’s presence and personality characteristics of college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2012;2012(3):384–6. [Google Scholar]

13. Twenge JM, Baumeister RF, Dewall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Bartels JM. Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(1):56–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Mccullough ME, Kilpatrick SD, Emmons RA, Larson DB. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol Bull. 2001;127(2):249–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Yulan L, Fengning S, Yanjiao F. Gratitude: a new field of positive psychology research. Soc Psychol Sci. 2008;2008(2):12–6. [Google Scholar]

16. Bartlett MY, Desteno D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior: helping when it costs you. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(4):319–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Bartlett MY. Gratitude: prompting behaviors that build relationships. Cogn Emot. 2012;26(1):2–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

18. Wu HT, Tseng SF, Wu PL, Chen CM. The relationship between parent-child interactions and prosocial behavior among fifth- and sixth-grade students: gratitude as a mediating variable. Univers J Educ Res. 2016;4(10):2361–73. [Google Scholar]

19. Zhao G, Sun FC, Liu ZJ, Feng YM, Huang SP, et al. The influence of parental warmth on adolescent’s gratitude: the mediating role of sense of responsibility and belief in a just world. Psychol Dev Edu. 2018;34(3):257–63. [Google Scholar]

20. Luo CM, Hunag XT. Forgiveness and mental health. Chin J Ment Health. 2004;18(10):742–3. [Google Scholar]

21. Christensen KJ, Padilla-Walker LM, Busby DM, Hardy SA, Day RD. Relational and social-cognitive correlates of early adolescent’s forgiveness of parents. J Adolescence. 2011;34(5):903–13. [Google Scholar]

22. Wang L, Fu J. Parenting styles and child development in China. Prog Psychol Sci. 2005;13(3):298–304. [Google Scholar]

23. Werner EE. Resilience in development. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1995;4(3):81–4. [Google Scholar]

24. Kumpfer KL. Factors and processes contributing to resilience: the resilience framework. In: Glantz MD, Johnson JL, editors. Resilience and development: positive life adaptations. New York: Kluwer/Plenum; 1999. p. 179–224. [Google Scholar]

25. Anyan F, Hjemdal O. Adolescent stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression: resilience explains and differentiates the relationships. J Affect Disorders. 2016;203:213–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Hjemdal O, Vogel PA, Solem S, Hagen K, Stiles TC. The relationship between resilience and levels of anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in adolescents. Clin Psychol Psychot. 2011;18(4):314–21. [Google Scholar]

27. Ma X, Wang Y, Hu H, Tao XG, Zhang Y, Shi H. The impact of resilience on prenatal anxiety and depression among pregnant women in Shanghai. J Affect Disorders. 2019;250:57–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

28. Poole JC, Dobson KS, Pusch D. Anxiety among adults with a history of childhood adversity: psychological resilience moderates the indirect effect of emotion dysregulation. J Affect Disorders. 2017;217(12):144–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

29. Xiang Y, Chen Z, Zhao J. How childhood maltreatment impacts aggression from perspectives of social comparison and resilience framework theory. J Aggress Maltreat T. 2019;19:1–12. [Google Scholar]

30. Friborg O, Barlaug D, Martinussen M, Rosenvinge JH, Hjemdal O. Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;14(1):29–42. [Google Scholar]

31. Krampe EM, Newton RR. The father presence questionnaire: a new measure of the subjective experience of being fathered. Fathering: J Theory Res Practice Men Fathers. 2006;4(2):159–90. [Google Scholar]

32. Zhang WR, Chen QH, Xiang YH. Revision of the father absence questionnaire—based on the brief version of father presence questionnaire (In Press). [Google Scholar]

33. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISCvalidation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(6):1019–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

34. Kong F, Wang X, Hu S, Liu J. Neural correlates of psychological resilience and their relation to life satisfaction in a sample of healthy young adults. Neuroimage. 2015;123(4):165–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

35. McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):112–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Chen LH, Kee YH. Gratitude and adolescent athletes’ well-being. Soc Indic Res. 2008;89(2):361–73. [Google Scholar]

37. Kong F, Ding K, Zhao J. The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, social support and life satisfaction among undergraduate students. J Happiness Stud. 2015;16(2):477–89. [Google Scholar]

38. Xiang Y, Chao X, Ye Y. Effect of gratitude on benign and malicious envy: the mediating role of social support. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

39. Hu S, Zhang A, Zhong H, Jia Y. A study on interpersonal forgive and revenge of undergraduates and their links with depression. Psycho Dev Edu. 2005;1:101–8. [Google Scholar]

40. Zhu H. Social support and affect balance mediate the association between forgiveness and life satisfaction. Soc Indic Res. 2015;124(2):671–81. [Google Scholar]

41. Wang L, Xiang Y, Yuan R. How is emotional intelligence associated with moral disgust? The mediating role of social support and forgiveness. Curr Psychol. 2021;42:1–11. [Google Scholar]

42. Brown RP. Measuring individual differences in the tendency to forgive: construct validity and links with depression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(6):759–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

43. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int J Test. 2001;1(1):55–86. [Google Scholar]

44. Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. London: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

45. Arbuckle JL. AMOS 5.0 update to the AMOS user’s guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters; 2003. [Google Scholar]

46. Rohner RP, Veneziano RA. The importance of father love: history and contemporary evidence. Rev Gen Psychol. 2001;5(4):382–405. [Google Scholar]

47. Kerker BD, Zhang J, Nadeem E, Stein RE, Hurlburt MS, Heneghan A, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and metal health, chronic medical conditions, and development in young children. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(5):510–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

48. Treat AE, Sheffield-Morris A, Williamson AC, Hays-Grudo J. Adverse childhood experiences and young children’s social and emotional development: the role of maternal depression, self-efficacy, and social support. Early Child Dev Care. 2020;190(15):2422–36. [Google Scholar]

49. Wurster HE, Sarche M, Trucksess C, Morse B, Biringen Z. Parents’ adverse childhood experiences and parent-child emotional availability in an American Indian community: relations with young children’s social-emotional development. Dev Psychopathol. 2020;32(2):425–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

50. Jorm AF, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Jacomb PA, Easteal S. Association of adverse childhood experiences, age of menarche, and adult reproductive behavior: does the androgen receptor gene play a role? Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;125(1):105–11. [Google Scholar]

51. Bevilacqua L, Kelly Y, Heilmann A, Priest N, Lacey RE. Adverse childhood experiences and trajectories of internalizing, externalizing, and prosocial behaviors from childhood to adolescence. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;112(3):104890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

52. Bretherton I. Bowlby’s legacy to developmental psychology. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1997;28(1):33–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

53. McCain MN, Mustard JF, Shanker S. Early years study 2: putting science into action. Integration the VLSI Journal. Toronto, Ontario: Council for Early Child Development; 2007. p. 178. [Google Scholar]

54. Berry K, Barrowclough C, Wearden A. Attachment theory: a framework for understanding symptoms and interpersonal relationships in psychosis. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(12):1275–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

55. Fry PS, Scher A. The effects of father absence on children’s achievement motivation, ego-strength, and locus-of-control orientation: a five-year longitudinal assessment. Brit J Dev Psychol. 1984;2(2):167–78. [Google Scholar]

56. Alfirević N, Arslanagić-Kalajdžić M, Lep Ž. The role of higher education and civic involvement in converting young adults’ social responsibility to prosocial behavior. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):2559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

57. Qin Y, Wan X, Qu S, Chen G. Family cohesion and school belonging in preadolescence: examining the mediating role of security and achievement goals. http://www.shs-conferences.org [Accessed 2015]. [Google Scholar]

58. MacKey WC. Father presence: an enhancement of a child’s well-being. J Mens Stud. 1998;6(2):227–43. [Google Scholar]

59. Ye B, Lei X, Yang J, Byrne PJ, Wang X. Family cohesion and social adjustment of Chinese university students: the mediating effects of sense of security and personal relationships. Curr Psychol. 2019;40:1872–83. [Google Scholar]

60. Hoffman ML. Father absence and conscience development. Dev Psychol. 1971;4(3):400–6. [Google Scholar]

61. Carr D. Is gratitude a moral virtue? Philos Stud. 2015;172(6):1475–84. [Google Scholar]

62. Emmons RR, Mccullough RM, Larson ED, Kilpatrick ES. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol Bull. 2001;127(2):249–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

63. Young L, Saxe R. Innocent intentions: a correlation between forgiveness for accidental harm and neural activity. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(10):2065–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

64. Luthar SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12(4):857–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

65. Vella SLC, Pai NB. A theoretical review of psychological resilience: defining resilience and resilience research over the decades. Arch Med Health Sci. 2019;7(2):233. [Google Scholar]

66. Harper CC, Mclanahan SS. Father absence and youth incarceration. J Res Adolescence. 2010;14(3):369–97. [Google Scholar]

67. McLanahan S, Tach L, Schneider D. The causal effects of father absence. Annu Rev Sociol. 2013;39(1):399–427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

68. Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26(1):399–419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

69. Michael RMD. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. Am J Orthopsychiat. 2010;57(3):316–31. [Google Scholar]

70. Olsson CA, Bond L, Burns JM, Vella-Brodrick DA, Sawyer SM. Adolescent resilience: a concept analysis. J Adolescence. 2003;26(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

71. Wright MOD, Masten AS. Resilience processes in development. In: Handbook of resilience in children. Boston, MA: Springer; 2005. p. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

72. Kumpfer KL. Factors and processes contributing to resilience: the resilience framework. In: Resilience and development: positive life adaptations. Rockville, MD: Ctr for Substance Abuse Prevention; 2002. p. 179–224. [Google Scholar]

73. Frisby BN, Booth-Butterfield M, Dillow MR, Martin MM, Weber KD. Face and resilience in divorce: the impact on emotions, stress, and post-divorce relationships. J Soc Pers Relat. 2012;29(6):715–35. [Google Scholar]

74. Zhikai Li. A study on the relationship between resilience and social support of left behind children. Chin J Health Psychol. 2009;17(4):440–42. [Google Scholar]

75. Anming H, Qiuping H, Huashan L. The relationship between social support and loneliness in college students: the mediating role of gratitude. Chin J of Clin Psychol. 2015;23(1):150–3. [Google Scholar]

76. Zhan Y, Congshu Z. Relationship between university students’ gratitude, self-concept and social support. Chin J Health Psychol. 2012;20(7):1110–2. [Google Scholar]

77. Halilova JG, Struthers CW, Guilfoyle J, Shoikhedbrod A, George M. Does resilience help sustain relationships in the face of interpersonal transgressions? Pers Indiv Differ. 2020;160(3):109928. [Google Scholar]

78. Jing S. Research on the formation mechanism of gratitude quality in adolescents. Chin Youth Res. 2008;(9):93–5. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools