Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Impact of Supervisory Career Support on Employees’ Well-Being: A Dual Path Model of Opportunity and Ability

1 Business School, Hohai University, Nanjing, 211100, China

2 School of Management, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, 430070, China

3 Yale Health Mental Health & Counseling, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA

* Corresponding Author: Weibo Yang. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(11), 943-955. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.055730

Received 05 July 2024; Accepted 10 October 2024; Issue published 28 November 2024

Abstract

Background: In the pursuit of fostering employees’ well-being, leaders are recognized as playing a vital role. However, so far, most of the existing research has focused on leadership behavior and the superficial interaction between leaders and members but has unexpectedly ignored the specific supporting role of supervisors in the career development of employees, that is, supervisory career support. Additionally, the internal mechanism of how career support from supervisors is related to and promotes employees’ well-being is still unclear. Based on social cognitive career theory (SCCT), this study aimed to explore whether, how, and when supervisory career support affects employee well-being by introducing the two paths of ‘career prospect’ and ‘career confidence.’ Methods: During July 2023, this study employed a cross-sectional design. We gathered participants from corporate situated in Southern China. Results: Results based on a large sample of 14,533 employees showed that supervisory career support was positively related to employees’ well-being through the dual path of career prospects (opportunity) and career confidence (ability). Employees high in proactive personality experienced the above positive effects most. Conclusion: This study provides meaningful implications for managers to implement personalized support strategies to improve employees’ well-being.Keywords

In contemporary workplaces, the mental health and well-being of employees are facing unprecedented challenges. According to a recent survey, nearly 60% of employees reported experiencing the negative effects of work-related depression, highlighting the universality and urgency of the mental health crisis in the workplace [1]. Especially in the context of the global economic downturn, employees’ worries about their career prospects and anxiety about their own abilities have become increasingly prominent, which poses a severe challenge to the overall well-being of employees [2]. In order to implement countermeasures to handle mental health crises, the American Psychological Association (APA) [3] emphasized the critical role of leaders in promoting employee well-being. Survey data showed that over 80% of employees’ expectations of future jobs indicate that ‘supervisor support for mental health’ is an important factor in their consideration of job opportunities, which further illustrates the importance of leadership support in the process of employee career development. Therefore, it is both urgent and important to continue to explore the relationship between leaders’ and employees’ well-being.

In recent years, the role of leaders in promoting employees’ well-being has been widely investigated from different perspectives, from microscopic to macroscopic [4]. However, most studies have mainly focused on the perspective of ‘leadership behavior’ [5] and ‘leader member exchange’ [6,7], ignoring the supporting role of leadership in employee career development. In other words, although existing research has explored the influence of supervisory support on employees’ career-related results, it is still unclear which specific supervisory support is closely related to employees’ career outcomes and well-being. Considering the importance of career development to the overall well-being of employees, the specific role and effect of supervisory career support, which refers to the career support that employees get from their direct leaders, including career guidance and performance feedback, needs to be precisely described [8]. Another limitation is that the internal mechanism of how supervisory career support affects employees’ well-being is still unclear. One possible explanation is the lack of an appropriate theoretical framework to systematically describe this process. The existing studies mostly relied on social exchange theory and leadership member exchange theory [9,10]. Although these theories provide a valuable perspective for understanding the relationship between employees and leaders, they pay more attention to the superficial characteristics and relationship quality of the exchange process and fail to dig deep into the specific psychological mechanisms that promote the development of employees’ career well-being. In fact, social cognitive career theory (SCCT) points out that an individual’s career outcome, including their mental health and overall well-being, are developed through the joint influence of individual confidence in self-ability and positive expectations regarding career prospects [11]. Finally, the existing research has neglected to investigate which types of individuals are more susceptible to the positive impact of supervisory support on career outcomes, resulting in the fact that, although workplace supportive supervisor interventions are seen as important mechanisms, they are still underutilized in bolstering employee well-being. We also noted that SCCT also emphasizes the role of personal characteristics as a boundary condition, which means that different employees’ reactions to the same supervisor support can vary from individual to individual [12]. Therefore, it is also necessary to further clarify the interactions between personality traits and supervisory career support to further help managers implement support interventions more effectively.

To help close the above research gap and respond to the APA’s calls, this study aimed to explore whether, how, and when supervisory career support might influence employees’ well-being. Based on SCCT, this paper reveals the critical predicting role of supervisory career support and the mechanism through which supervisor support influences employee well-being by considering the dual perspectives of opportunities and abilities. By introducing two new paths—career prospects and career confidence—this study provides a new explanatory framework for understanding the complex relationship between supervisory career support and employee well-being. Additionally, we aimed to provide practical strategic guidance for enterprise managers to implement more targeted support interventions in their daily management. These, in turn, hopefully promote employees’ mental health and overall well-being, thereby enhancing their organization’s sustainable development.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Social cognitive career theory (SCCT)

SCCT is concerned with the ways in which other people and environmental factors help shape an individual’s career path [13,14] and how they affect an individual’s career perceptions and outcomes through two paths [11,15]. One path is the individual’s confidence, or self-ability. When individuals receive support from the environment, such as encouragement from a supervisor or the provision of resources, they experience enhancements in their confidence to complete their tasks, thus promoting their career satisfaction and well-being. The other path is career outcome expectations. Individuals are more likely to feel satisfied and happy in their jobs when they perceive opportunities for career development, or when they believe that the current working environment can yield valuable and positive outcomes [16]. SCCT also emphasizes the role of personal characteristics as a boundary condition [17]. Specifically, the impact of environmental factors on individual career satisfaction and well-being differs depending on individuals’ personalities.

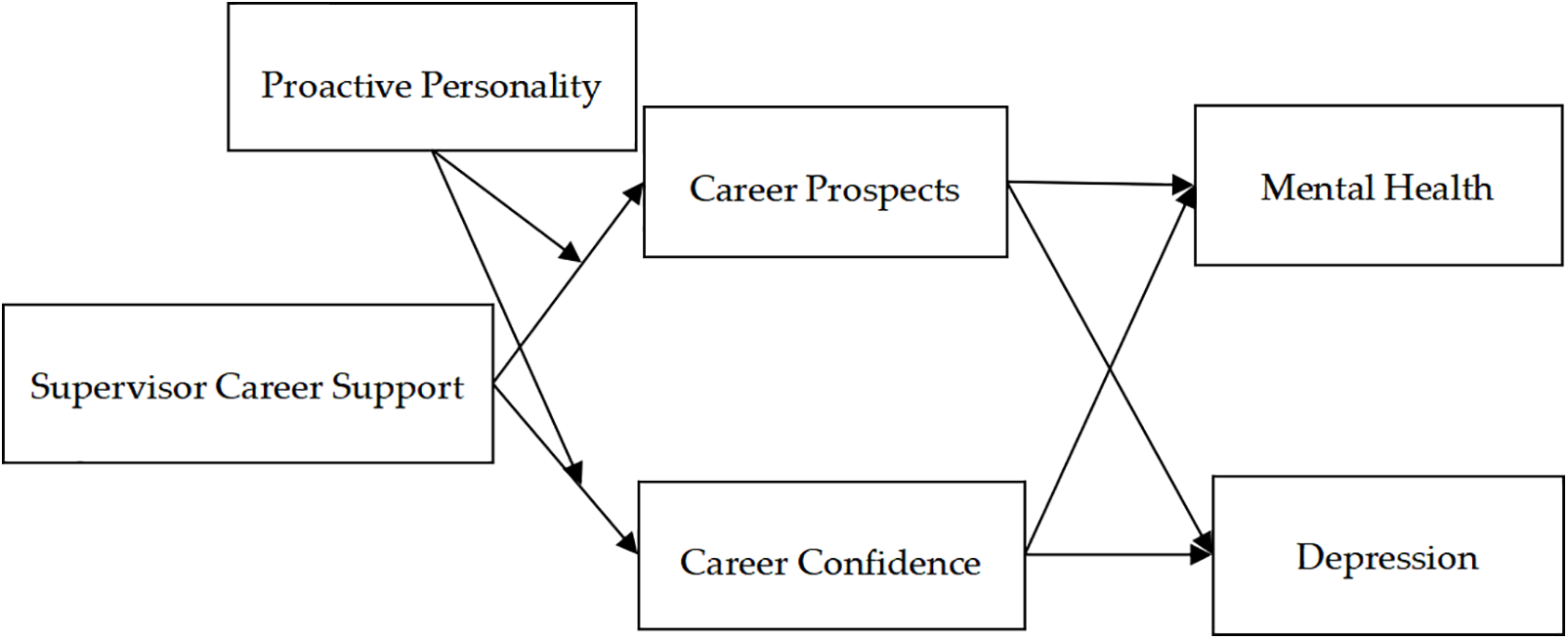

Based on SCCT, we hypothesized the following: (a) supervisory career support is positively associated with employee well-being, as evidenced by its positive impact on mental health and negative impact on depression; (b) career prospects serve as a mediator between supervisory career support and well-being, as indicated by levels of mental health and depression; (c) career confidence mediates the relationship between supervisory career support and well-being, as indicated by levels of mental health and depression; (d) the level of proactive personality moderates the indirect effect of supervisory career support on mental health and depression through career prospects and career confidence. The suggested research model is depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Hypothesis model.

Supervisory career support and well-being

Well-being refers to an overarching construct that encompasses a range of positive qualities and experiences [18]. The components of well-being can be divided into positive aspects and negative aspects [19]. However, most previous studies have focused on examining well-being using single indicators like job satisfaction or depression. A recent literature review also suggested that future researchers explore well-being from the integrative perspective of both positive and negative effect [20]. Specifically, mental health serves as a key indicator for measuring the positive effect of well-being. It represents a state of overall well-being that helps individuals effectively manage life’s challenges, utilize their strengths, and perform well [21]. Conversely, depression entails negative experiences which can manifest as psychological tension and discomfort, which serve as typical examples of the negative affect of well-being [22]. Therefore, the present study chose mental health as the representative of the positive effect of well-being and depression as the representative of the negative effect of well-being. Then, these indicators were integrated into the analytical framework of well-being to explore the well-being of individuals in the workplace from an integrative perspective.

SCCT provides us with a comprehensive theoretical framework to understand the factors that contribute to well-being in the workplace. Specifically, SCCT holds that relevant environmental support factors have an impact on individual career-related results [13]. Within this theoretical framework, supervisory career support represents a key environmental support factor, encompassing the assistance, guidance, and emotional support provided by leaders in the process of employee career development [23]. According to SCCT, we expected that supervisory career support would positively relate to employees’ well-being. Specifically, when employees perform tasks, the guidance and resource-support provided by their supervisors can reduce pressure at work [24]. When employees are faced with problems like career choice, development planning, and skill upgrading, if supervisors can provide the necessary resources, guidance, or solutions in time, the support can greatly reduce the pressure brought by the uncertainty of work and help employees maintain their mental health. Additionally, career support from a supervisor can also include care and help for the employee’s personal career development. When supervisors show concern for the personal career growth of the employees, the employees may feel their self-worth recognized and promoted [25]. The enhancement of this sense of self-worth is arguably the key factor in improving employees’ mental health. Finally, supervisory career support contributes to providing emotional comfort for employees. In the process of career development, employees will inevitably encounter setbacks and failures. When supervisors show care, understanding, and encouragement, the employees may experience emotional warmth and a sense of acceptance [26]. This positive emotional support can help boost employees’ mental health.

On the other hand, depression negatively impacts the perception of well-being. According to SCCT, we expected that supervisory career support would reduce employee depression. Specifically, the career support of the supervisor would stimulate employees’ sense of hope. Hope is an important psychological resource to resist depression because it assists employees in coping with the challenges in work and life and can reduce the risk of depression [27]. Additionally, a supervisor’s career support might also include creating a positive and warm environment for team employees. When employees feel warmth and acceptance from the team, their sense of loneliness in the workplace can be lessened. Loneliness is often associated with depression, especially for employees who lack social interaction at work [28]. Therefore, a supervisor’s career support can reduce the loneliness of employees and then reduce the employees’ risk of depression.

Hypothesis 1. Supervisory career support will be positively associated with well-being, which will be manifested by supervisory career support positively affecting mental health (1a) and negatively affecting depression (1b).

The mediating role of career prospects

How does supervisory career support positively affect well-being? SCCT emphasizes that environmental support affects an individual’s career satisfaction and well-being through two paths. One path is the expectation of positive results from career prospects [11]. Individuals are more likely to feel satisfied and happy in their jobs when they think their career has development opportunities or that the current working environment will result in valuable and positive results [29]. Within the framework of SCCT, career prospects refer to individuals’ expectations and views on their future career development, including positive expectations for promotion opportunities [12]. This expectation is highly consistent with the expected path of positive results, and both are based on optimistic judgments about future career development. According to SCCT, we expected that positive relations between supervisory career support and well-being, indicated by mental health and depression, are mediated by career prospects. Specifically, the career support of supervisors is cultivated to provide employees with more opportunities for learning and development, which will help employees improve their professional skills and knowledge [30], thus enhancing their competitiveness and expectations for their careers. Additionally, the career support from supervisors was predicted to help employees clarify their career development direction and goals [31]. Having a clear career goal promotes a sense of ease and purpose among employees, thereby boosting their expectations regarding their career prospects. Furthermore, supervisory career support is not limited to personal development, but may also include helping employees establish and maintain career networks [32]. Through introduction and recommendation, employees can connect with a wider range of industry contacts, which are crucial for expectations of future career opportunities and partnerships. Based on Hypothesis 1, supervisory career support was expected to positively affect well-being, which would be manifested in a positive impact on mental health and a negative impact on depression. Therefore:

Hypothesis 2. Career prospects will play a mediating role between supervisory career support and well-being, as indicated by employees’ levels of mental health (2a) and depression (2b).

The mediating role of career confidence

Apart from the expectations of results, SCCT also emphasizes that environmental support can also affect an individual’s career results through the other path of ‘individual confidence in self-ability’ [13]. When individuals perceive support from the environment (e.g., the encouragement of supervisors or the provision of resources), they will experience enhancements in their confidence that they can then use to complete their tasks, thus enhancing their well-being [15]. According to SCCT, career confidence refers to an individual’s belief that they can successfully meet challenges, complete tasks, and realize professional achievements in their field [33], which is consistent with the concept of self-efficacy, that is, an individual’s belief that they have the ability to successfully carry out necessary actions. Therefore, based on SCCT, we assumed that relations between supervisory career support and well-being, indicated by mental health and depression, can also be mediated by career confidence. Specifically, the career support of the supervisor can help provide recognition and affirmation of employees in their career paths [34]. When employees perceive their career affirmed and appreciated by their supervisors, they will be more convinced of their abilities and values. In addition, direct career support from supervisors for acquiring new skills or enhancing existing ones empowers employees, making them more confident in their professional abilities [35]. Finally, a career-supportive supervisor can help create a safe environment where mistakes are framed as learning opportunities, fostering psychological safety [36]. This allows employees to take risks and innovate without fear, enhancing their overall career confidence. Based on Hypothesis 1, supervisory career support was predicted to positively affect well-being, which would be manifested by a positive impact on mental health and a negative impact on depression. Therefore, we proposed:

Hypothesis 3. Career confidence will play a mediating role between supervisory career support and well-being, as indicated by employees’ mental health (3a) and depression (3b).

The moderating role of proactive personality

In this process, it is important to highlight that SSCT emphasizes the role of personal characteristics as boundary conditions [12]. Faced with the same supervisory career support, different employees’ reactions may vary from person-to-person due to different personalities. A ‘proactive personality’ refers to an individual’s active and spontaneous action-tendency in the face of environmental changes, which embodies the individual’s ability to actively adapt to and change the environment [37]. On the one hand, proactive individuals are characterized by initiative-taking and are inclined to seize opportunities without waiting for explicit instructions [38]. When encountering supervisory career support, they actively seek out ways to apply this support to their career development, translating the support from their supervisors into the prospect of going further on their career path and achieving greater accomplishments. This initiative-taking, when coupled with a highly proactive personality, is anticipated to enhance the positive outcomes of supervisory career support on mental health and the negative effects on depression. On the other hand, employees with highly proactive personalities tend to have a self-starting mindset [39]. They are more inclined to leverage external support into motivation, to show more confidence in their work, and thereby to experience a higher sense of well-being at work. Conversely, employees with a less proactive personality may be relatively passive in the face of the career support of their supervisors and may even turn a blind eye to the support, thus missing an opportunity to enhance their career prospects and their career confidence. Consequently, it would be difficult to promote one’s mental health and reduce depression without proactivity. Thus, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 4. Proactive personality levels will moderate the indirect effect of supervisory career support on well-being via career prospects (4a) and career confidence (4b).

This study employed a cross-sectional design. We gathered participants from corporate situated in Southern China. In order to ensure the representativeness and universality of the sample, this study adopts the method of combining random sampling with convenient sampling. Specifically, we first cooperated with the human resources department of the enterprise and obtained the employee list. On this basis, we use a random number generator to randomly select some employees from the employee list of each enterprise as potential survey objects. Random sampling is helpful to reduce artificial selection bias and improve the representativeness of samples. At the same time, considering the feasibility and efficiency of actual operation, we also combine the convenient sampling method. That is, with the assistance of the human resources department, an invitation email was sent to these randomly selected employees through the company’s internal mail system. The email explained the study’s objectives and guaranteed privacy for respondents. Employees interested in taking part could respond via email.

The questionnaire consists of a supervisory career support scale, career prospects scale, career confidence scale, mental health scale, depression scale, and proactive personality scale. Social-demographic information included gender, age, level of education, and job tenure. When determining the sample size, we considered the significance level of the expected effect, the statistical efficacy requirements, and the number of potential participants. In this study, G*Power is used to calculate the sample size [40]. A total of 14533 questionnaires (85.92%) were deemed valid self-report questionnaire. The participant demographics consisted of 59.6% males and 40.4% females, forming a well-balanced group. Among them, 29.1% were younger staff members aged between 25% and 30%, 29.2% were individuals in the age range of 31% to 40%, and 22.5% were those aged above 40. The median education level was a 4-year college degree. Among the employees. the manufacturing and information transmission industries accounted for 16.1%, the production industry accounted for 21.4%.

This study strictly followed the ethical requirements in the whole process of data collection. We followed the principles of voluntary participation and transparency. All participants were informed of the purpose, process, potential risks and benefits of their participation in the study, and signed an informed consent form. In addition, we have taken appropriate measures to protect the privacy and information security of participants and ensure that all data are used only for research purposes and kept strictly confidential.

Supervisory career support was assessed using a four-item scale created by Scandura et al. [41]. A representative sample item was “My leader showed personal concern for my career.” Participants were requested to provide their responses using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree”. This scale has demonstrated high levels of validity and reliability in previous research [42], as evidenced by the internal consistency of α = 0.93 reported in this study.

Career prospects were measured using a five-items scale adopted from Wan et al. [43]. A representative sample item was “I think about where my career future lies.” Participants were requested to provide their responses using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree”. This scale has been widely used and has shown to be a reliable and valid measure of career prospects [44], with an internal consistency of α = 0.87 in my sample.

Career confidence was measured using five items scale developed by Borgen et al. [45]. Sample item is “I am optimistic about my career.” Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Prior research has established the reliability of this tool, as evidenced by the internal consistency of α = 0.90 in this study.

Mental health was measured using a three-items scale adopted from Lukat et al. [46]. A sample item was “I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future.” Participants were requested to provide their responses using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree”. This scale has demonstrated high levels of validity and reliability in previous research, as evidenced by the internal consistency of α = 0.90 in this study.

Depression was measured using the thirteen items scale taken from Shaver et al. [47]. A sample item is “I feel lonely.” Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale has established validity and reliability in assessing depressive symptoms, with an internal consistency of α = 0.90 in this study.

Proactive personality was measured using the four items scale adopted from Parker et al. [48]. Sample item is “I am good at finding opportunities that are beneficial to me.” Participants were requested to provide their responses using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree”. This scale has been widely used and has shown to be a reliable and valid measure of career prospects, with an internal consistency of α = 0.81 in this study.

Previous studies have shown that certain socio-demographic variables can affect well-being, as indicated by mental health and depression [49–51]. As a result, these variables were deemed suitable for use as control variables in the present study. Participants provided this information at Time 1. Socio-demographic factors were assessed using age, gender (coded as 0 = male, 1 = female), educational level (categorized as 0 = associate, 1 = bachelor, 2 = master or higher), and duration of employment with the organization.

In this study, we used a variety of statistical methods to analyze the data, and used SPSS 26.0 software for data sorting and descriptive statistics. Given that the sample size is large enough, and there is no serious skew or extreme abnormal value in the data, the data in this study meet the normal hypothesis. Firstly, we used the software Mplus 8.0 to analyze the structural equation model (SEM). In the SEM analysis, we use the maximum likelihood estimation method to estimate the model parameters. In order to ensure the fitting degree of the model, we adopted several fitting indexes, including χ²/df, CFI, TLI, SRMR and RMSEA. Secondly, in the preliminary analysis, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Mplus 8.0 to test the discrimination validity between the core constructs in the study. In the correlation analysis, we used SPSS 26.0 software to calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between variables to preliminarily test the relationship between variables. In addition, we also used Mplus 8.0 software to analyze the mediation effect and adjust the mediation effect. In the analysis of mediating effect, we tested the mediating effect of career prospects and career confidence between superior career support and employee well-being through path analysis. In the analysis of mediating effect, we further discussed how active personality mediates the above-mentioned mediating path. We selected the significance level at 0.05 to judge the significance of each statistical test. All statistical methods were selected based on their applicability in this study, and the reliability of the results are ensured.

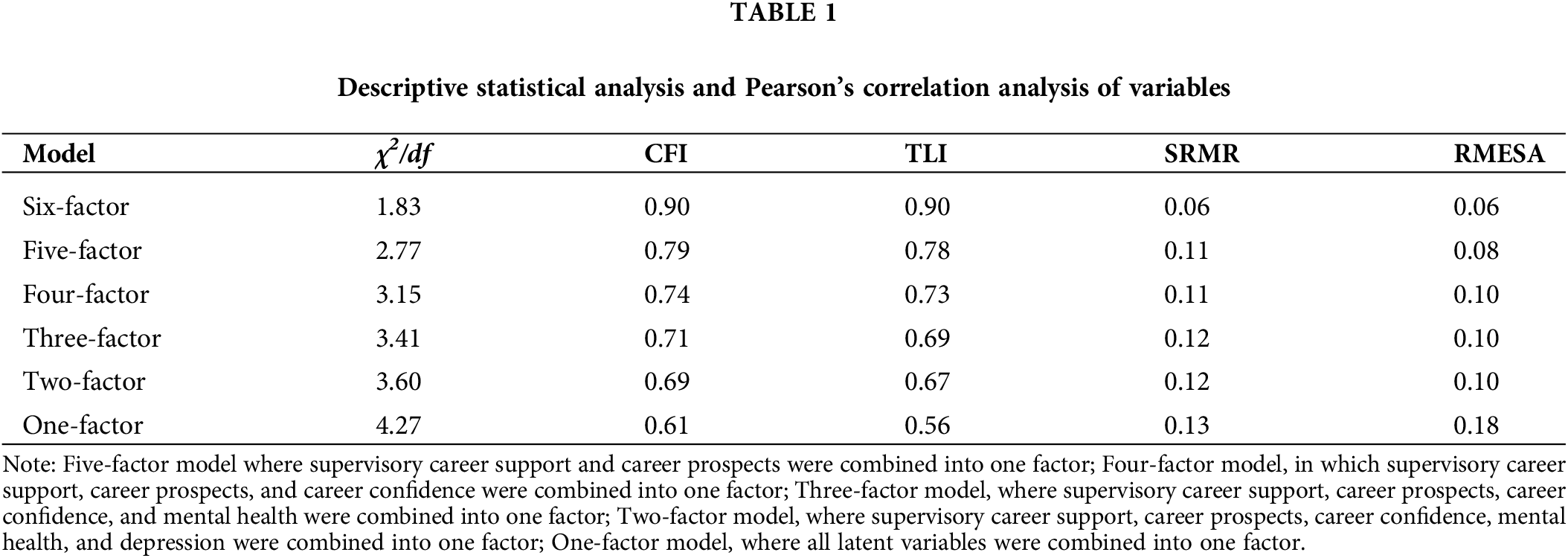

Initially, we utilized Mplus 8.0 to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis in order to evaluate the uniqueness of the primary constructs involved in this study. The findings indicated that the six-factor model, which distinguished between supervisory career support, career prospects, career confidence, mental health, depression, and proactive personality, provided a better fit to the data. χ2 = 2552.75, df = 1396, χ2/df = 1.83, CFI = 0.90 (CFI ≥ 0.90), TLI = 0.90 (TLI ≥ 0.90), SRMR = 0.06 (SRMR ≤ 0.07), RMSEA = 0.06 (RMSEA ≤ 0.07) [52], compared to alternative models. The results are shown in Table 1.

Second, following the advice of Podsakoff et al. [53], we conducted a test to examine common method deviation. The testing revealed that including the method factor did not significantly enhance the model compared to the theoretically assumed six-factor model (χ2/df = 1.90, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.05, ∆CFI = 0.01; ∆TLI = 0.00; ∆RMSEA = 0.01; ∆SRMR = 0.01). Therefore, no clear evidence of common method variance was found in the present study. As a result, common method bias is reduced in this study.

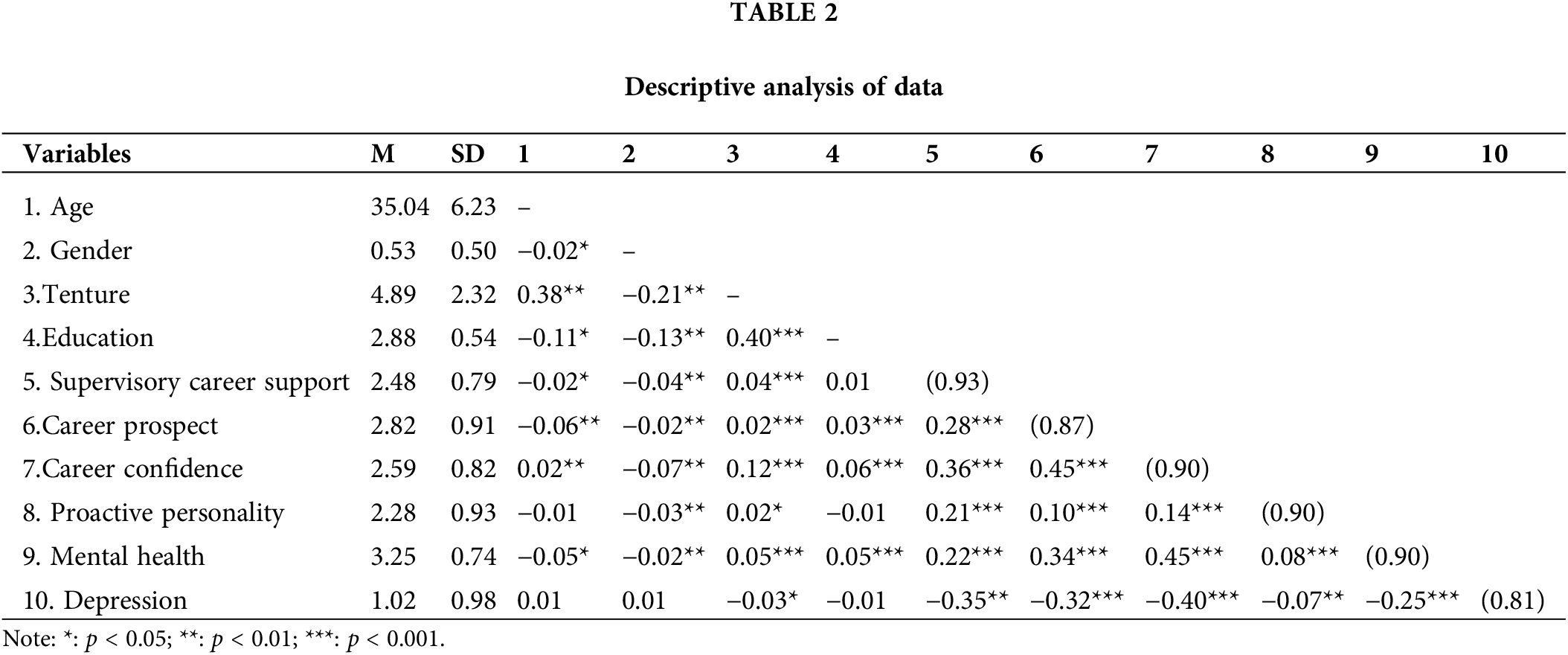

Table 2 reports the descriptive analysis of the study variables.

As shown in Table 2, supervisory career support was positively correlated with well-being indicated by mental health (r = 0.22, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with depression (r = −0.35, p < 0.01). Additionally, supervisory career support had a positive correlation with career prospects (r = 0.28, p < 0.001) and career confidence (r = 0.36, p < 0.001). Furthermore, career prospects were positively associated with mental health (r = 0.34, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with depression (r = −0.32, p < 0.001). The findings indicated that there is a positive relationship between career confidence and mental health (r = 0.45, p < 0.001), alongside a negative relationship with depression (r = −0.40, p < 0.001), thereby providing preliminary validation for hypotheses one to three.

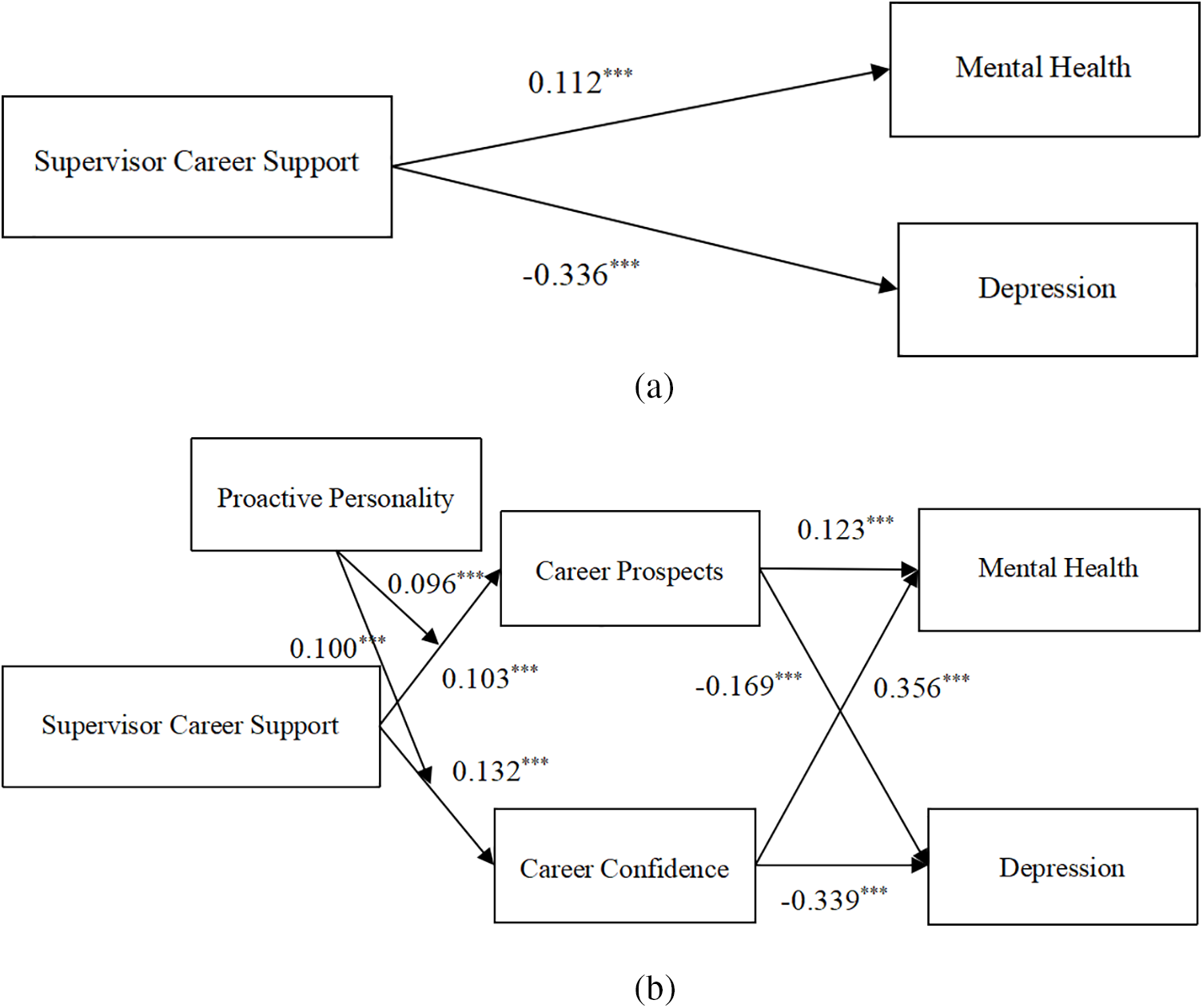

To verify our theoretical framework, we utilized structural equation modeling as our analytical tool. In Mplus 8.0, the estimation method is maximum likelihood parameter estimates. The standardized regression weights for each relationship within the structural equation model are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Results of structural model assessment. Note: ***p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 1 states that supervisory career support is related to well-being, which is manifested by positively affecting mental health and negatively affecting depression. Fig. 2 demonstrates that, after adjusting for the impact of age, work experience, gender, and educational level, supervisory career support remained significantly positively related to mental health (B = 0.112, SE = 0.026, p < 0.001) and significantly negatively related to depression (B = −0.336, SE = 0.017, p < 0.001). The findings confirmed both hypothesis 1a and hypothesis 1b. This finding aligns with previous studies that highlight the beneficial influence of social support on psychological well-being, which shows that vocational support from superiors can effectively buffer work pressure and enhance employees’ psychological resilience [44].

Hypothesis 2 states that career prospect acts as an intermediary in the connection between supervisory career support and well-being, as indicated by mental health and depression. Fig. 2 showed that supervisory career support positively influenced career prospects (B = 0.103, SE = 0.038, p < 0.001), which was also positively associated with mental health (B = 0.123, SE = 0.008, p < 0.001) and negatively related to depression (B = −0.169, SE = 0.010, p < 0.001). The interval for the indirect impact at the 95% confidence level indicated that managerial career support was positively and indirectly associated with mental health (estimate: 0.101, 95% CI = 0.071, 0.141) and negatively related to depression (estimate: 0.06, 95% CI = 0.042, 0.105). Consequently, hypothesis 2 was validated. Of note, Hypothesis 3 states that career confidence acts as an intermediary in the connection between supervisory career support and well-being, as indicated by mental health and depression. Fig. 2 showed that supervisory career support positively affected on career confidence (B = 0.132, SE = 0.044, p < 0.001), which, in turn, was associated with the high level of mental health (B = 0.356, SE = 0.011, p < 0.001) and negatively related to depression (B = −0.339, SE = 0.013, p < 0.001). The indirect effect was significant as well (mental health: 0.032, 95% CI = [0.022, 0.042]; depression: 0.021, 95% CI = [0.012, 0.031]). Consequently, hypothesis 3 was validated. This finding is consistent with the theory of career development, which shows that a clear career prospect can enhance employees’ work motivation and satisfaction, thus improving their mental health [42].

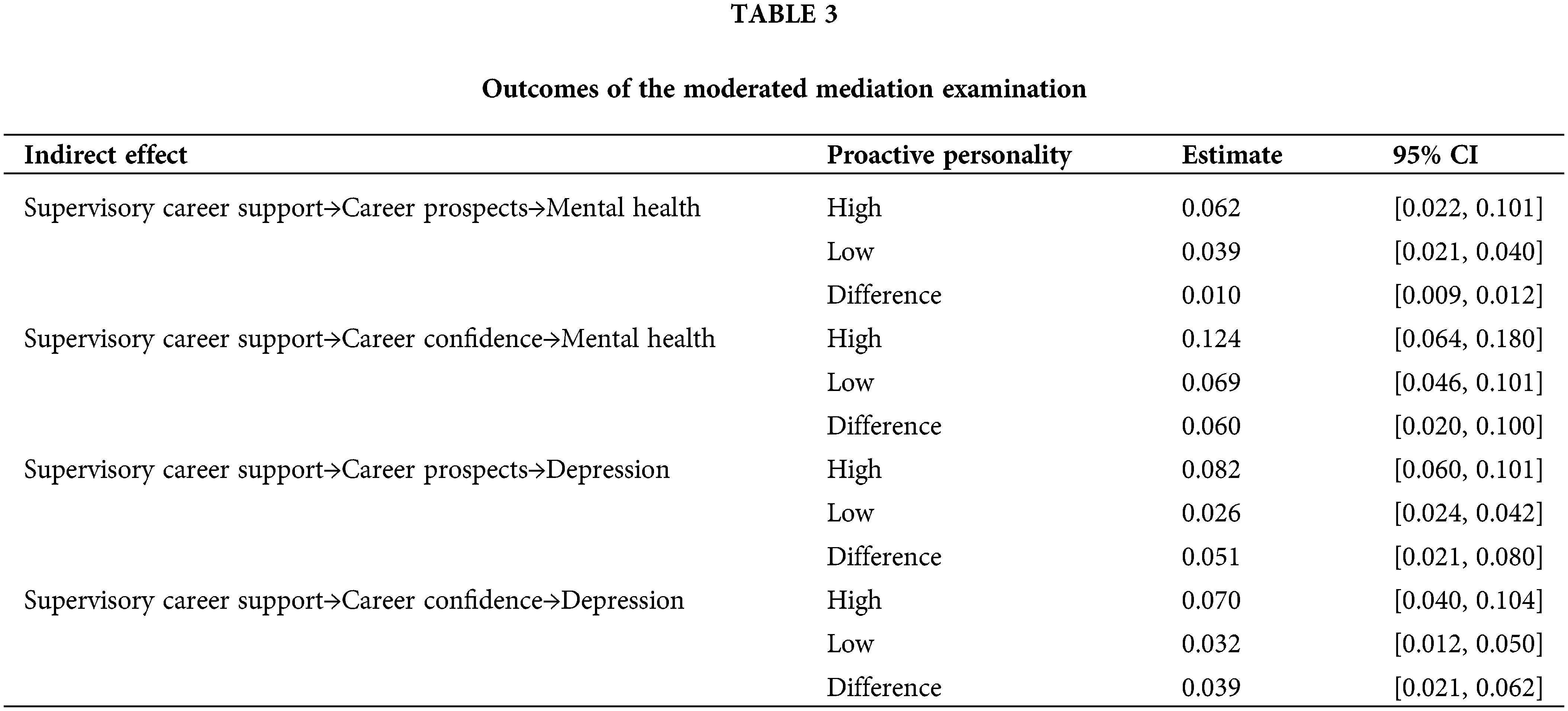

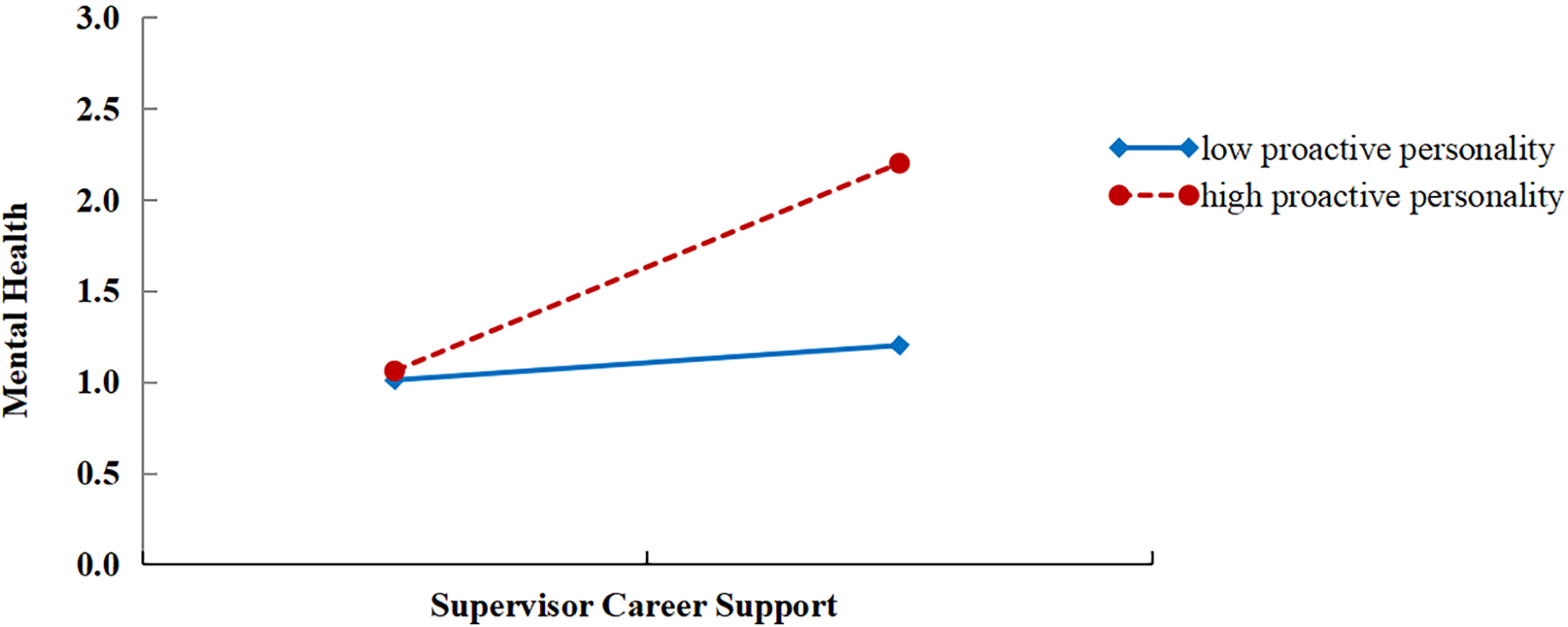

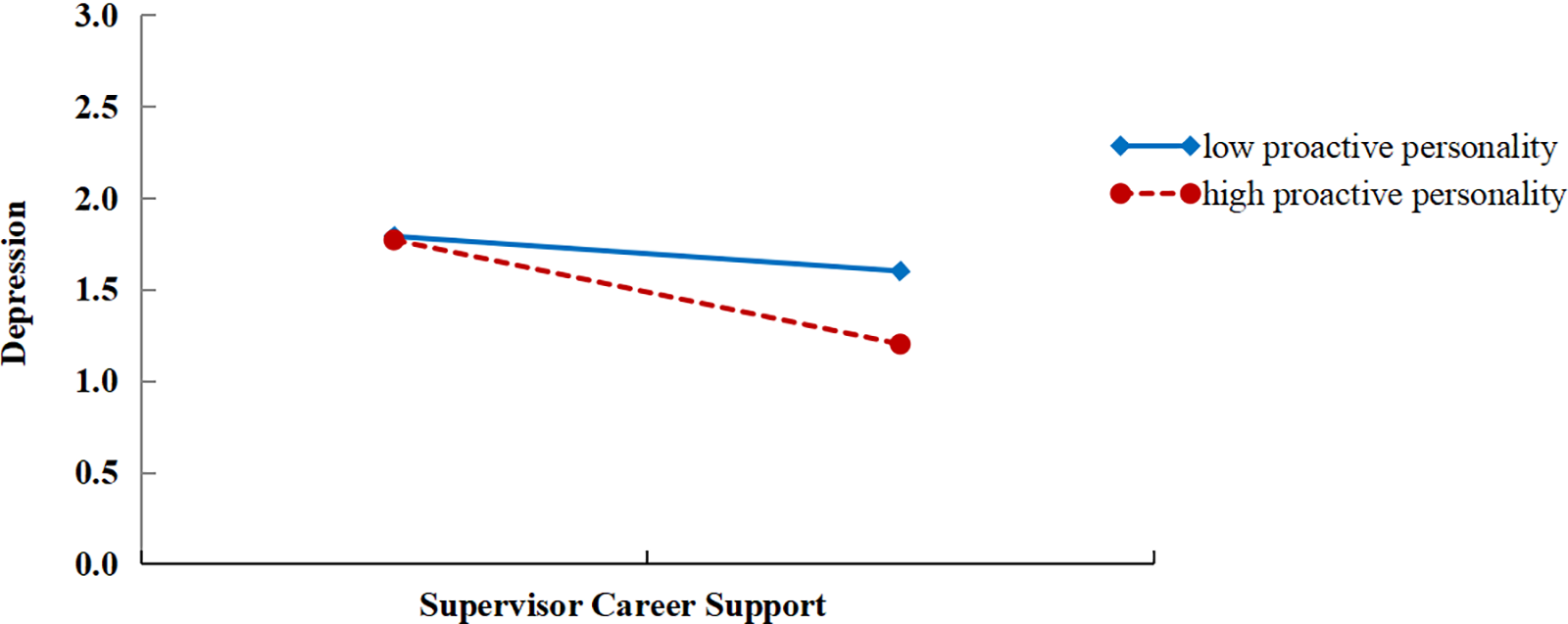

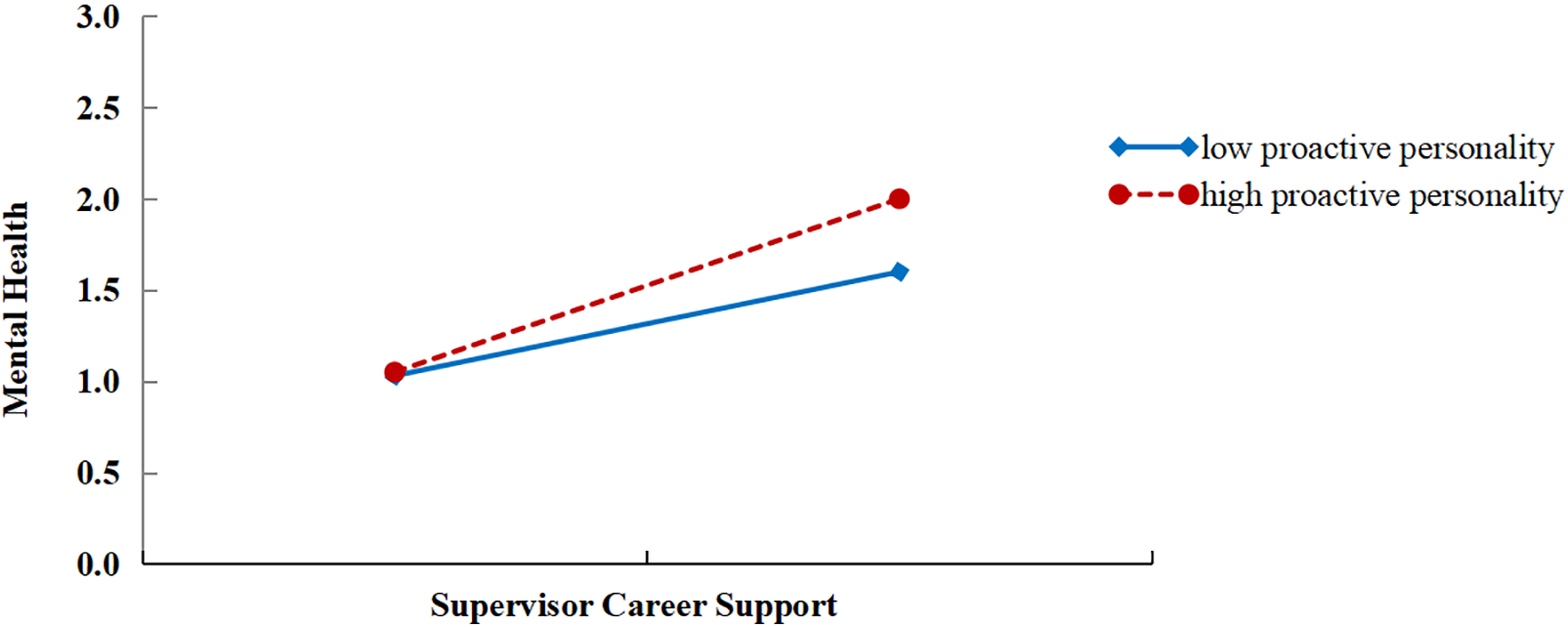

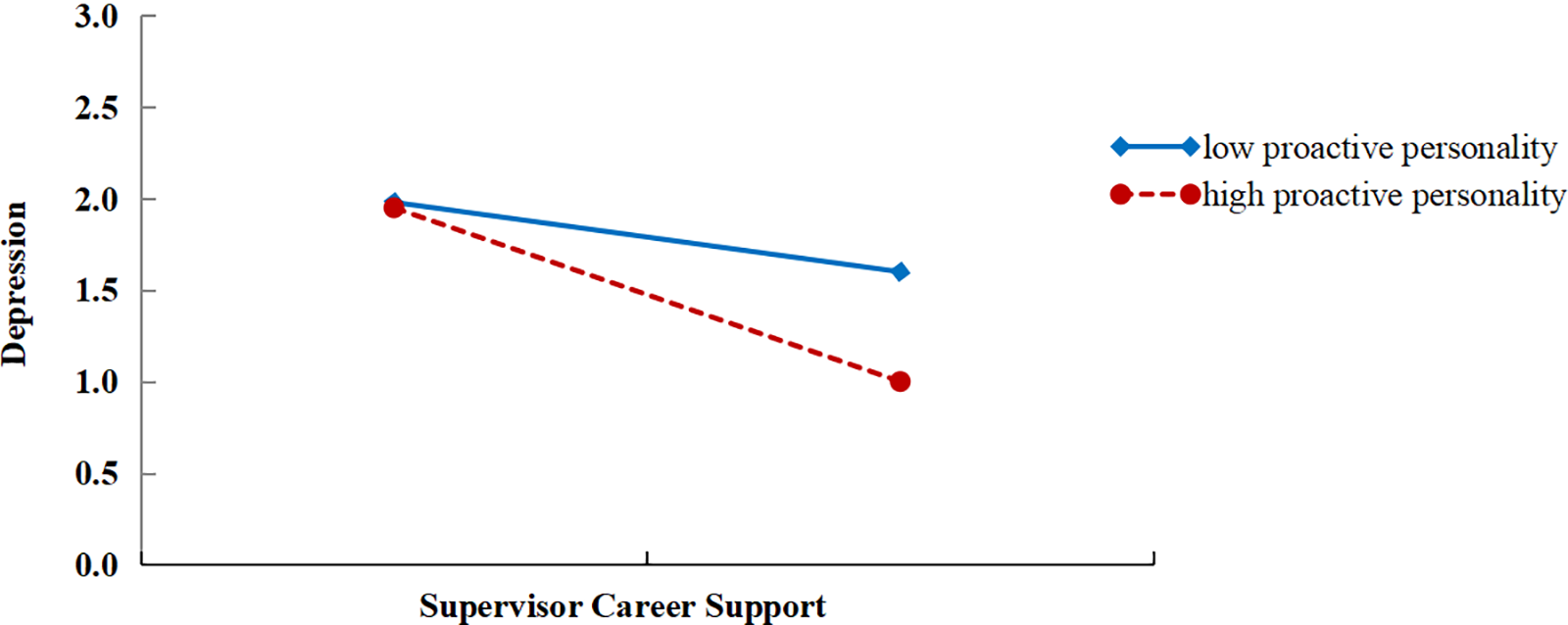

Hypothesis 4 states that proactive personality moderates the indirect effect of supervisory career support on well-being via career prospects and career confidence. This was examined using conditional process analysis in Mplus 8.0. Table 3 indicates that, starting with mental health, the positive indirect effect of supervisory career support on mental health through career prospects was significant at lower levels of proactive personality (−SD, estimate: 0.039, 95% CI = 0.021, 0.040) compared to higher levels (+SD, estimate: 0.062, 95% CI = 0.022, 0.101; difference = 0.010, 95% CI = 0.009, 0.012). Similarly, the indirect effect of supervisory career support on mental health through career confidence was significant at lower levels of proactive personality (−SD, estimate: 0.069, 95% CI = 0.046, 0.101) as compared to higher levels of proactive personality (+SD, estimate: 0.124, 95% CI = 0.064, 0.180; difference = 0.060, 95% CI = 0.020, 0.100). A similar pattern was observed for depression, with a more pronounced positive indirect effect through career prospects at low levels of proactive personality (+SD, estimate: 0.026, 95% CI = 0.024, 0.042) compared to high levels of proactive personality (−SD, estimate: 0.082, 95% CI = 0.060, 0.101; difference = 0.051, 95% CI = 0.021, 0.080). Similarly, the positive indirect effect of supervisory career support on depression via career confidence was significant at lower proactive personality (−SD, estimate: 0.032, 95% CI = 0.012, 0.050) compared to high levels of proactive personality (+SD, estimate: 0.070, 95% CI = 0.040, 0.104; difference = 0.039, 95% CI = 0.021, 0.062). Consequently, hypothesis 4 was validated. To clearly demonstrate the moderating effect of proactive personality, the following figures were created. The following figures show that the impact of managerial career support on well-being, as indicated by mental health, was more pronounced when proactive personality is high. Figs. 3 and 4 show that the effect of supervisory career support on well-being, as indicted by mental health, was more pronounced when proactive personality is high. Figs. 5 and 6 show that the impact of managerial career support on well-being, as indicated by depression, was more pronounced when proactive personality is high. This result is consistent with the theory of self-efficacy, that is, the confidence of individuals in their own abilities is an important factor affecting their mental health [54].

Figure 3: Proactive personality as a moderator between the relationship with supervisory career support and mental health via career prospects.

Figure 4: Proactive personality as a moderator between the relationship with supervisory career support and depression via career prospects.

Figure 5: Proactive personality as a moderator between the relationship with supervisory career support and mental health via career confidence.

Figure 6: Proactive personality as a moderator between the relationship with supervisory career support and depression via career confidence.

In today’s highly competitive working environment, employees’ happiness is closely related to their career development. So, how can leaders improve employees’ happiness through specific career support? Based on SCCT, the present study investigated whether, how, and when supervisory career support promotes employee well-being, as indicated by mental health and depression levels. We discovered a positive connection between managerial career support and well-being, manifested by its positive impact on mental health and negative impact on depression. Additionally, the impact of supervisory career support on employee well-being stemmed from two paths. The first path was the opportunity path, where career prospects mediated the connection between managerial career support and well-being, as indicated by mental health and depression. The second path was the ability path, where career confidence served as a mediator between supervisory career support and well-being, as indicated by mental health and depression. Furthermore, we found that levels of proactive personality moderated our mediation model. The current research thus extends the extant knowledge and provides practical implications for researchers.

First, based on SCCT, this study examined the predicting role of supervisory career support on employee well-being, which provides a new theoretical perspective for understanding the development of employee well-being in the workplace. In the past, most of the studies discussed the relationship of leadership and employee well-being from macro [55] to micro levels [56], ignoring the specific career supporting role of leaders in the career development of employees. In fact, the career development of employees is crucial to their overall well-being [57]. This study provides a new perspective for understanding the role of leadership on employee well-being and enriches the research on supervisory support by narrowing the scope to career support.

Second, from the perspective of the dual path of opportunity and ability, this study revealed the specific mechanism of supervisory career support affecting employee well-being. The APA pointed out the need for employers to improve employees’ mental health [3]. However, the current pathways for employers to achieve this improvement are not clear [58]. This uncertainty makes it difficult for employers to effectively support employees’ mental health and well-being in practice. Therefore, by examining the mechanism of supervisory career support on employee well-being through the two pathways of career prospects and career confidence, this study provides useful theoretical insights for further discussion on how employers can improve employee well-being.

Third, this study also clarifies the moderating role of proactive personality in the relationship between supervisory career support and employee well-being, providing new insights into the influence of individual differences in the promotion of employee well-being and further enriching SCCT. As a kind of individual characteristic of employees, a proactive personality can affect employees’ perceptions and utilization of supervisors’ support [59], therewith affecting employees’ well-being. By introducing proactive personality as a moderating variable, this study connects the different reactions of employees with different levels of proactive personality to the influence of supervisory career support on employee well-being, thereby providing theoretical support for managers seeking to formulate personalized support strategies.

From the perspective of organizational practice, the results of this study have the following important significance and suggestions. This study also provides practical insights for enterprise managers who seek to promote employee well-being through enhancing supervisory career support. Our findings indicate that supervisory career support can have a positive impact on employee well-being. Therefore, managers should demonstrate greater care for their employees in daily management by providing necessary support and assistance. Specifically, managers can provide training and development opportunities to assist employees in improving their skills and promote career growth. In addition to providing essential work resources and tools, emotional support should also be provided. This can be achieved through actions like giving praise, and encouragement, and organizing team-building activities to create a sense of warmth and support among employees.

Second, considering the pivotal role of career confidence and career prospects as key pathways, managers might concentrate their supportive efforts on fostering employee capability development and providing ample opportunities for growth. On the one hand, managers can assign tasks that exceed employees’ current capabilities but concurrently provide necessary resources and guidance to encourage these employees to step out of their comfort zone and engage in learning. Successful completion of such tasks will bolster employees’ career confidence. On the other hand, managers can enhance employees’ career prospects by organizing regular career planning seminars, helping them gain a clear understanding of their career orientation and potential future development paths.

Third, managers should consider employees’ personality traits when implementing support strategies. For example, for employees with a strong proactive personality, managers can provide more autonomy and decision-making power, encouraging active participation in innovation and improvement. Conversely, for employees with a less proactive personality, managers can help build their self-confidence and gradually improve their ability by offering more guidance and feedback. By implementing personalized support strategies, managers can effectively promote employees’ well-being and enhance the sustainable development capabilities of their organizations.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the discussed theoretical and practical insights, our study had some limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional in nature, and the data were collected only at a single point. While this method can reveal associations between different variables, we cannot use the results to discuss causal relationships between variables [60]. In addition, although the data analysis results of this study show that there is no obvious homogeneity error problem in this study, the possibility of homogeneity error cannot be completely ruled out. Future studies might incorporate rigorous longitudinal or experimental designs. Second, our data stemmed mainly from participants’ self-evaluations. Although self-evaluation is widely used in psychology and management research, self-reports can be influenced by individual subjectivity biases, like social-approval deviation [61]. To enhance the objectivity and accuracy of this research, future researchers might consider co-facilitating other assessments, like peer evaluations. Finally, this study assessed the influence of supervisory career support on employee well-being through the dual path of opportunity and ability, but there may be other, unexplored intermediary mechanisms. The relationship between managerial career support and employee well-being may also be influenced by mediating factors such as psychological capital or work-life balance [62]. Future researchers might explore these potential mediating variables to comprehensively investigate the impact of managerial career support on employee well-being, thus expanding upon our conclusions.

Based on SCCT, this study explored the critical role of supervisory career support on employee well-being and revealed the dual mechanism of career prospects (opportunity path) and career confidence (ability path). Our results not only enrich the field’s knowledge of the role of the leader in employees’ well-being from the new perspective of supervisory career support, but we also provided practical guidance for enterprise managers to implement personalized support strategies. Managers should understand the importance of career support by enhancing employees’ career prospects and career confidence and then customize support measures according to their employees’ levels of proactivity.

Acknowledgement: We thank all participants who took part in the current study.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project no. 72272117).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Lijun He and Weibo Yang; methodology, Jialing Miao; formal analysis, Lijun He, Weibo Yang, Jialing Miao and Jingru Chen; investigation, Jingru Chen; resources, Weibo Yang; data curation, Jialing Miao; writing—original draft preparation, Lijun He, Weibo Yang, Jialing Miao and Jingru Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Wuhan University of Technology Institutional Review Board (IRB No. MN 2023078). All participants signed an informed consent form in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. American Psychological Association. The American workforce faces compounding pressure. 2021. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/work-well-being/compounding-pressure-2021. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

2. Akkermans J, Richardson J, Kraimer ML. The COVID-19 crisis as a career shock: implications for careers and vocational behavior. J Vocat Behav. 2020;119:103434. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. American Psychological Association. Workers appreciate and seek mental health support in the workplace. 2022. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/work-well-being/2022-mental-health-support. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

4. Inceoglu I, Arnold KA, Leroy H, Lang JW, Stephan U. From microscopic to macroscopic perspectives and back: the study of leadership and health/well-being. J Occ Health Psych. 2021;26(6):459–68. doi:10.1037/ocp0000316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Guo Y, Wang S, Rofcanin Y, Las Heras M. A meta-analytic review of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSBswork-family related antecedents, outcomes, and a theory-driven comparison of two mediating mechanisms. J Voc Behav. 2024;1:103988. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2024.103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kaluza AJ, Weber F, Van Dick R, Junker NM. When and how health-oriented leadership relates to employee well-being—The role of expectations, self-care, and LMX. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2021;51(4):404–24. doi:10.1111/jasp.12744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Niessen C, Mäder I, Stride C, Jimmieson NL. Thriving when exhausted: the role of perceived transformational leadership. J Voc Behav. 2017;103:41–51. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yang F, Liu J, Huang X, Qian J, Wang T, Wang Z, et al. How supervisory support for career development relates to subordinate work engagement and career outcomes: the moderating role of task proficiency. Hum Resour Manag J. 2018;28(3):496–509. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hammer LB, Wan WH, Brockwood KJ, Bodner T, Mohr CD. Supervisor support training effects on veteran health and work outcomes in the civilian workplace. J Appl Psychol. 2019;104(1):52–67. doi:10.1037/apl0000354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mohr CD, Hammer LB, Brady JM, Perry ML, Bodner T. Can supervisor support improve daily employee well-being? Evidence of supervisor training effectiveness in a study of veteran employee emotions. J Occup Organ Psych. 2021;94(2):400–26. doi:10.1111/joop.12342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lent RW, Brown SD. Integrating person and situation perspectives on work satisfaction: a social-cognitive view. J Voc Behav. 2006;69:236–47. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2006.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lent RW, Ireland GW, Penn LT, Morris TR, Sappington R. Sources of self-efficacy and outcome expectations for career exploration and decision-making: a test of the social cognitive model of career self-management. J Voc Behav. 2017;99:107–17. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lent RW, Brown SD. Social cognitive career theory at 25: empirical status of the interest, choice, and performance models. J Voc Behav. 2019;115:103316. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2019.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Gao S, Sun S. Social cognitive career theory: its research and applications. Psychol Sci. 2005;28(5):1263–65 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

15. Schaub M, Tokar DM. The role of personality and learning experiences in social cognitive career theory. J Voc Behav. 2005;66(2):304–25. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2004.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sheu HB, Bordon JJ. SCCT research in the international context: empirical evidence, future directions, and practical implications. J Career Assess. 2017;25(1):58–74. doi:10.1177/1069072716657826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Conklin AM, Dahling JJ, Garcia PA. Linking affective commitment, career self-efficacy, and outcome expectations: a test of social cognitive career theory. J Career Dev. 2013;40(1):68–83. doi:10.1177/0894845311423534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lomas T, Ivtzan I. Second wave positive psychology: exploring the positive-negative dialectics of wellbeing. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17:1753–68. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9668-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lawton MP. The varieties of wellbeing. Exp Aging Res. 1983;9(2):65–72. doi:10.1080/03610738308258427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Van Agteren J, Iasiello M, Lo L, Bartholomaeus J, Kopsaftis Z, Carey M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(5):631–52. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01093-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. World Health Organization. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice. Geneva: WHO. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

22. Ryff CD, Singer B. Psychological well-being: meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65(1):14–23. doi:10.1159/000289026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Mihalache M, Mihalache OR. How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees’ affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Hum Resour Manag. 2022;61(3):295–314. doi:10.1002/hrm.22082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Li M, Ye H, Zhang G. How employees react to a narcissistic leader? The role of work stress in relationship between perceived leader narcissism and employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors to supervisor. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2018;20(3):83–97. doi:10.32604/IJMHP.2018.010806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sguera F, Bagozzi RP, Huy QN, Boss RW, Boss DS. The more you care, the worthier I feel, the better I behave: how and when supervisor support influences (un) ethical employee behavior. J Bus Ethics. 2018;153(3):615–28. doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3339-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Smollan RK. Supporting staff through stressful organizational change. Hum Resour Dev Int. 2017;20(4):282–304. doi:10.1080/13678868.2017.1288028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mao Y, He J, Morrison AM, Andres Coca-Stefaniak J. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: from the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr Issues Tour. 2021;24(19):2716–34. doi:10.1080/13683500.2020.1770706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ozcelik H, Barsade SG. No employee an island: workplace loneliness and job performance. Acad Manage J. 2018;61(6):2343–66. doi:10.5465/amj.2015.1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Tims M, Derks D, Bakker AB. Job crafting and its relationships with person-job fit and meaningfulness: a three-wave study. J Voc Behav. 2016;92:44–53. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jia S, Khassawneh O, Mohammad T, Cao Y. Knowledge-oriented leadership and project employee performance: the roles of organisational learning capabilities and absorptive capacity. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(10):8825–38. doi:10.1007/s12144-023-05024-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Charoensukmongkol P, Moqbel M, Gutierrez-Wirsching S. The role of coworker and supervisor support on job burnout and job satisfaction. J Adv Manag Res. 2016;13(1):1–17. doi:10.1108/JAMR-06-2014-0037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang S, Luan K. How do employees build and maintain relationships with leaders? Development and validation of the workplace upward networking scale. J Voc Behav. 2024;150:103985. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2024.103985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ocampo ACG, Reyes ML, Chen Y, Restubog SLD, Chih YY, Chua-Garcia L, et al. The role of internship participation and conscientiousness in developing career adaptability: a five-wave growth mixture model analysis. J Voc Behav. 2020;120:103426. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mao JY, Quan J, Li Y, Xiao J. The differential implications of employee narcissism for radical versus incremental creativity: a self-affirmation perspective. J Organiz Behav. 2021;42(7):933–49. doi:10.1002/job.2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Diamantidis AD, Chatzoglou P. Factors affecting employee performance: an empirical approach. Int J Prod Perform Manage. 2019;68(1):171–93. doi:10.1108/IJPPM-01-2018-0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Frazier ML, Fainshmidt S, Klinger RL, Pezeshkan A, Vracheva V. Psychological safety: a meta-analytic review and extension. Pers Psychol. 2017;70(1):113–65. doi:10.1111/peps.12183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhou W, Li M, Xin L, Zhu J. The interactive effect of proactive personality and career exploration on graduating students’ well-being in school-to-work transition. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2018;20(2):41–54. doi:10.32604/IJMHP.2018.010737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wu CH, Parker SK, Wu LZ, Lee C. When and why people engage in different forms of proactive behavior: interactive effects of self-construals and work characteristics. Acad Manage J. 2018;61(1):293–323. doi:10.5465/amj.2013.1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zahra M, Kee DMH. Influence of proactive personality on job performance of bank employees in Pakistan: work engagement as a mediator. Int J Manage Stud. 2022;29(1):83–108. doi:10.32890/ijms2022.29.1.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kang H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G* Power software. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2021;18:1–12. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Scandura TA, Ragins BR. The effects of sex and gender role orientation on mentorship in male-dominated occupations. J Voc Behav. 1993;43(3):251–65. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1993.1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Young AM, Perrewe PL. What did you expect? An examination of career-related support and social support among mentors and protégés. J Manage. 2000;26(4):611–32. doi:10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00049-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wan YKP, Wong IA, Kong WH. Student career prospect and industry commitment: the roles of industry attitude, perceived social status, and salary expectations. Tour Manage. 2014;40:1–14. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2013.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wen H, Li X, Kwon J. Undergraduate students’ attitudes toward and perceptions of hospitality careers in Mainland China. J Hosp Tour Ed. 2019;31(3):159–72. doi:10.1080/10963758.2018.1487787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Borgen FH, Betz NE. Career self-efficacy and personality: linking career confidence and the healthy personality. J Career Assess. 2008;16(1):22–43. doi:10.1177/1069072707305770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Lukat J, Margraf J, Lutz R, Van der Veld WM, Becker ES. Psychometric properties of the positive mental health scale (PMH-scale). BMC Psychol. 2016;4:1–14. doi:10.1186/s40359-016-0111-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Shaver PR, Brennan KA. Measures of depression. Meas Personal Soc Psychol Attitudes. 1991;1:195–289. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-590241-0.50010-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Parker SK, Williams HM, Turner N. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(3):636–52. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Jin W, Miao J, Zhan Y. Be called and be healthier: how does calling influence employees’ anxiety and depression in the workplace? Int J Ment Health Promot. 2022;24(1):1–12. doi:10.32604/IJMHP.2022.018624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Miao J, Liao W, Xie B. Who benefits more from physical exercise? On the relations between personality, physical exercise, and well-being. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2023;25(10):1147–57. doi:10.32604/ijmhp.2023.030671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Proto E, Quintana-Domeque C. COVID-19 and mental health deterioration by ethnicity and gender in the UK. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0244419. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivar Behav Res. 1990;25(2):173–80. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Carpinello SE, Knight EL, Markowitz FE, Pease EA. The development of the mental health confidence scale: a measure of self-efficacy in individuals diagnosed with mental disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2000;23(3):236–43. doi:10.1037/h0095162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Chughtai A, Byrne M, Flood B. Linking ethical leadership to employee well-being: the role of trust in supervisor. J Bus Ethics. 2015;128:653–63. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2126-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Carnevale JB, Hatak I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: implications for human resource management. J Bus Res. 2020;116:183–7. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Mäkikangas A, Kinnunen U, Feldt T, Schaufeli W. The longitudinal development of employee well-being: a systematic review. Work Stress. 2016;30(1):46–70. doi:10.1080/02678373.2015.1126870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Shipman K, Burrell DN, Huff Mac Pherson A. An organizational analysis of how managers must understand the mental health impact of teleworking during COVID-19 on employees. Int J Organ Anal. 2023;31(4):1081–104. doi:10.1108/IJOA-03-2021-2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. McCormick BW, Guay RP, Colbert AE, Stewart GL. Proactive personality and proactive behaviour: perspectives on person-situation interactions. J Occup Organ Psych. 2019;92(1):30–51. doi:10.1111/joop.12234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Spector PE. Do not cross me: optimizing the use of cross-sectional designs. J Bus Psychol. 2019;34(2):125–37. doi:10.1007/s10869-018-09613-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Mabe PA, West SG. Validity of self-evaluation of ability: a review and meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 1982;67(3):280–96. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.67.3.280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Roemer A, Harris C. Perceived organisational support and well-being: the role of psychological capital as a mediator. SA J Ind Psychol. 2018;44(1):1–11. doi:10.4102/sajip.v44i0.1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools