Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Promoting International Students’ Mental Health Unmet Needs: An Integrative Review

1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Health, Medicine and Wellbeing, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia

2 President’s Office, Tung Wah College, Hong Kong, China

3 The Nethersole School of Nursing, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong, China

* Corresponding Authors: Carmen Hei Man Shek. Email: ; Regina Lai Tong Lee. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Healthy Lifestyle Behaviours and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2024, 26(11), 905-924. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.055706

Received 04 July 2024; Accepted 17 October 2024; Issue published 28 November 2024

Abstract

Background: There are increasing concerns about the mental health needs of international students. Previous studies report that international students experience additional challenges and higher levels of stress compared to domestic students. This integrative review aimed to identify perceived stressors, coping strategies and factors that contributed to accessing mental health services of international students. Methods: A systematic search was performed between January 2010 and December 2023 using PubMed, CINAHL, ProQuest, the Cochrane Library, Scopus and PsycINFO databases. A manual search was also performed that included reference lists of included articles; data was extracted and reviewed by three reviewers. A total of 21 studies were included in this review with a total of 4442 international students recruited, with ages between 17 to 43 years. Nineteen studies reported international students’ gender, there were more females (n = 2205) than males (n = 1022). Ethnicity was reported in 18 studies. They included Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America, South America, Africa, the Middle East and Pacific Islands. This review adopted Whittemore and Knafl’s five-stage approach, with specific steps for problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation. Results: The Health Belief Model was used to explain relationships among independent and dependent variables and guide the findings of this review. Three identified progressive themes emerged including Theme 1: understanding cultural variations with perceived stress; Theme 2: coping strategies in dealing with stress and challenges in the new environment; and Theme 3: perceived threats and stress affecting how international students perceived barriers and benefits to access counselling support services and mental health services. This integrative review presents an overview of mental health needs and factors contributing to the mental health and well-being of international students via the inclusion of studies with different designs, providing an in-depth understanding of the study phenomenon. The findings of this review may help university health providers, mental health professionals, academic institutions and policymakers better understand the multifaceted needs of international students. Conclusion: This review demonstrates the importance of increased cross-cultural interactions between international students and domestic student counterparts to enhance belongingness and connection to host countries. This may facilitate adaptation to new living and learning environments. It is crucial academic institutions offer programs that can be effectively implemented and sustained to meet the unmet mental health needs of international students. University orientation programs, student counselling and health services may integrate cultural events, social support groups, leadership programs and resilience models of acculturation to promote mental health and well-being among international students. While these studies show promising results, there is a need for further robust evaluative studies to develop culturally sensitive mental health promotion programs for international students.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe unmet mental health needs of international students have gained increasing attention in recent years. Unlike domestic students, international students need to overcome challenges associated with new living and learning environments, language barriers, psychosocial and academic difficulties, and financial issues in their host country [1]. It has been found that a lack of social support in the new living and learning environment may lead to loneliness, isolation and psychological distress [2,3]. This results in poor mental health status among international students due to difficulty in coping with life changes in an unsupportive environment.

Previous research suggests individual, environmental and coping factors may influence how university students cope with stress [4]. University students with high neuroticism tend to have repeated negative thoughts and unpleasant emotions leading to higher levels of stress [5]. Environmental factors including accessibility of supportive resources on campus may empower students to seek support and thus help relieve stress [6]. Regarding coping factors, university students who adopted avoidance approaches in stressful situations such as substance use reported higher levels of stress than those using active approaches such as help-seeking behaviours from external sources [7]. Emotional self-regulation is a common element of healthy adjustment [8]. High emotional regulation may help mitigate the perceived stress associated with psychological and academic difficulties among international students [9]. An understanding of the emotional regulation of international students is important. Such understanding may help identify students who may have issues with emotion regulation and thus are at risk of developing mental health issues. This may further enable higher education institutions and mental health providers to offer timely support and prevent deterioration of mental health status. Literature reports on-campus mental health support services are available to international students, with only 17% of students accessing services, indicating low uptake [10]. Low uptake of services may be due to international students perceiving formal mental health support services as ineffective or inadequate to address their needs [11]; or they perceive seeking mental health support as taboo in their culture or due to a cultural perspective where mental illnesses have been labelled as ‘crazy’ or ‘mad’ [12]. Higher education providers also report challenges with cultural barriers in developing tailored mental health services and interventions to meet the specific needs of international students [2,10]. This is reportedly due to a lack of diversity in the mental health workforce [2,10].

Tailoring of mental health interventions is often guided by the Health Belief Model (HBM) [13]. The HBM is a theoretical framework based on psychological and behavioural theory which aims to understand and predict health-related behaviours. The HBM theory posits that decision-making occurs when the following four elements take place: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits and perceived barriers [13]. In this review, independent variables were adopted from the HBM [13]. They included perceived susceptibility, health motivation, perceived benefits, perceived barriers and cues to action. International students’ perceived susceptibility to stress, health motivation [strategies] to cope with demands in the new living and learning environments, their perceived benefits and perceived barriers based on their own cultural beliefs; and cues to action for health-related help-seeking behaviours in the host countries. Dependent variables were health-related, help-seeking behaviours in dealing with stresses and challenges to cope with the demands of new living and learning environments among international students.

International students are a unique population with diverse cultural backgrounds and personal past experiences. Culture may influence the perception, explanation, and behavioural decisions for health promotion and the relief of suffering [14]. Given the marked reluctance to access formal mental health support services among international students, how they perceived their susceptibility to stress, their motivations to cope with demands in their host country, and factors associated with help-seeking behaviours become a high priority for research, program initiatives and policy. This integrative review aimed to explore how international students perceived and coped with stress; and contributing factors to utilizing mental health support services. Such understanding may inform health policymakers, university health planners health promoters and educators to develop appropriate strategies to best support the university international students’ mental health needs.

An integrative review design offers a comprehensive understanding of a particular phenomenon to generate new knowledge in social and behavioural science [15]. To establish the reliability and rigour of the review, the steps of designing, conducting, and reporting the review in a stepwise approach are critical. This review adopted Whittemore et al. [16] five-stage approach, with specific steps for problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation. Whittemore et al. [16] review was appropriate as it outlined systematic steps to accommodate quantitative and qualitative literature ensuring consistency and rigour. The steps undertaken during data synthesis and further critical appraisal ensured quality assessment of included studies relevant to the research objectives was systematically completed [17]. The review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [18]. The systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines (Supplementary Checklist). The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Newcastle (Reference Number: H-2022-0397). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

This review aimed to i) explore perceptions of stress among international students, ii) investigate coping strategies adopted by international students to cope with demands of new living and learning environments, and iii) understand factors contributing to international students’ utilization of mental health support services.

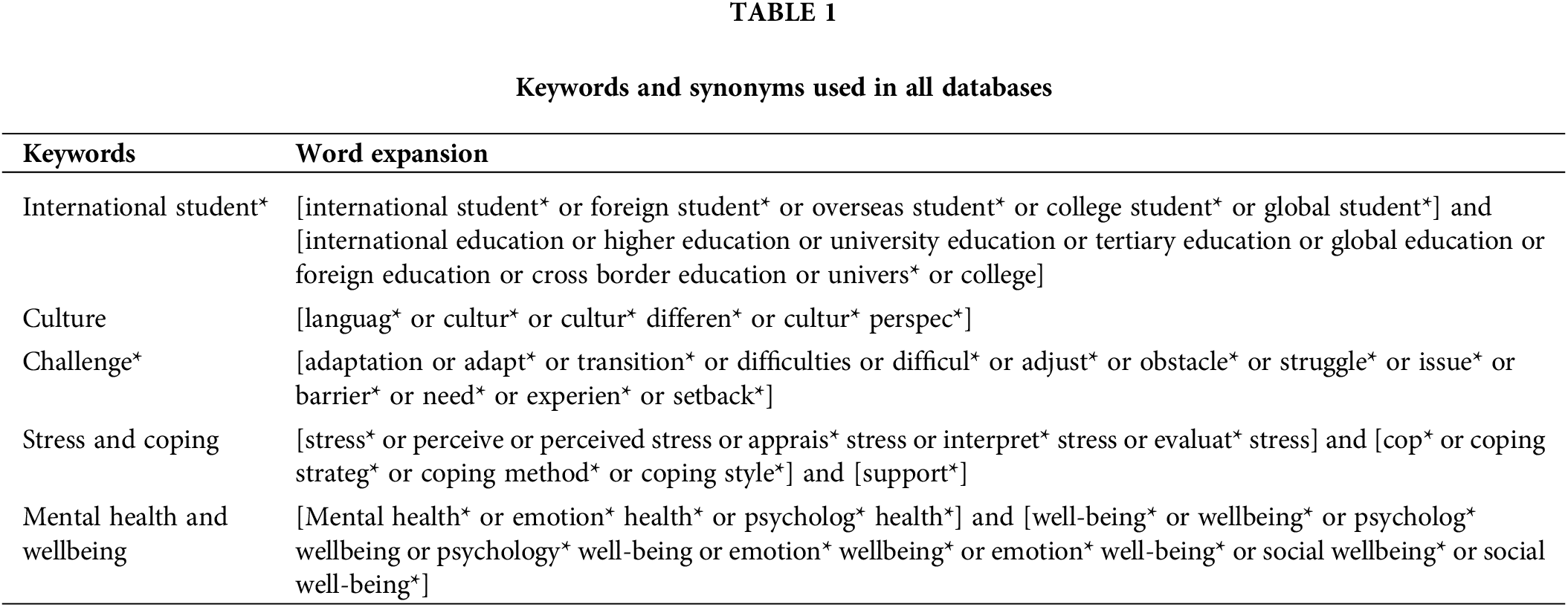

A systematic search was conducted using electronic databases including PubMed, CINAHL, ProQuest, the Cochrane Library, Scopus and PsycINFO after consulting two university librarians in 2023. An additional search was performed including hand-searching reference lists of included articles. Searched terms included ‘international student’, ‘overseas student’, ‘college student’, ‘higher education’, ‘university education’, ‘tertiary education’, ‘adaptation’, ‘challenges’ ‘sociodemographic’, ‘stress’, ‘coping’, ‘coping strategy’, ‘coping method’, ‘coping style’, ‘social support’, ‘mental health’, ‘wellbeing’, ‘well-being’, ‘psychological wellbeing’, ‘emotional wellbeing’, ‘social wellbeing’. Boolean operators [AND, OR, NOT] were used to combine the keywords. Synonyms of each keyword were generated via word expansion (see Table 1).

There is generally no limitation on the publication date in an integrative review [18]. Studies published within the past 10 years are suggested for inclusion, with literature being searched up to the time of review writing [19,20]. Inclusion criteria included: 1) published between January 2010 to December 2023; 2) full-text original research including both qualitative and quantitative designs; 3) published in English; and 4) international students who were studying on campus.

Studies were excluded if: 1) published in languages other than English; 2) not primary research, dissertations or conference abstracts, 3) included off-campus international students; and 4) focused on mental disorders and treatments.

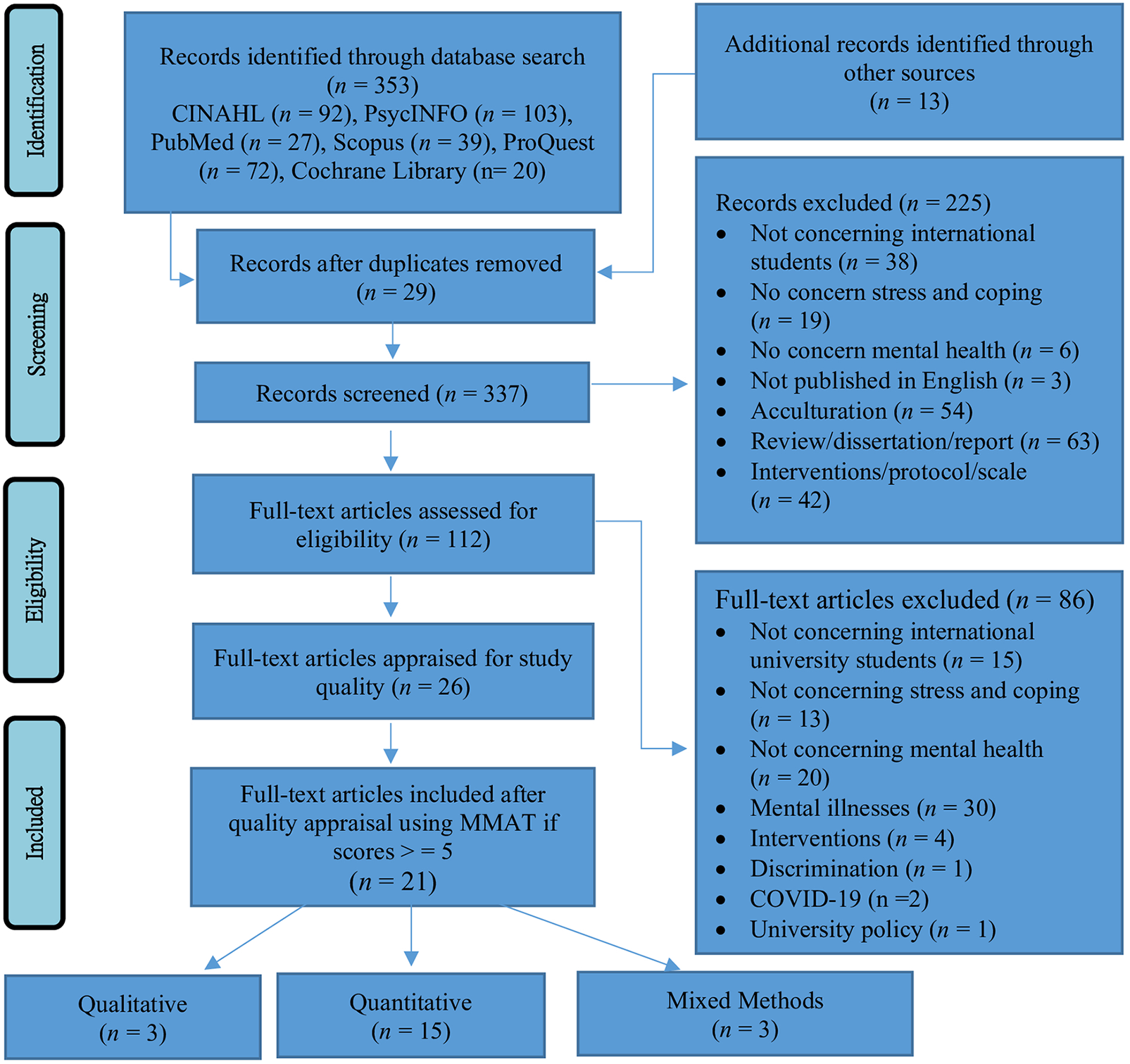

The initial search identified 353 studies. Another 13 studies from reference lists that were seemingly relevant were retrieved. Search results were imported into Endnote X9. Titles, abstracts and full texts of identified studies were assessed for duplication as well as eligibility for inclusion in this review. Duplicates (n = 29) were removed by extracting titles into a spreadsheet. Titles and abstracts of 337 studies were screened. A total of 225 studies were excluded, leaving 112 studies that were assessed according to eligibility criteria. A further 86 studies were excluded, and 26 studies were appraised for their methodological quality. There were 21 studies identified after quality appraisal. The guideline of the PRISMA diagram is presented in Fig. 1 [21].

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram.

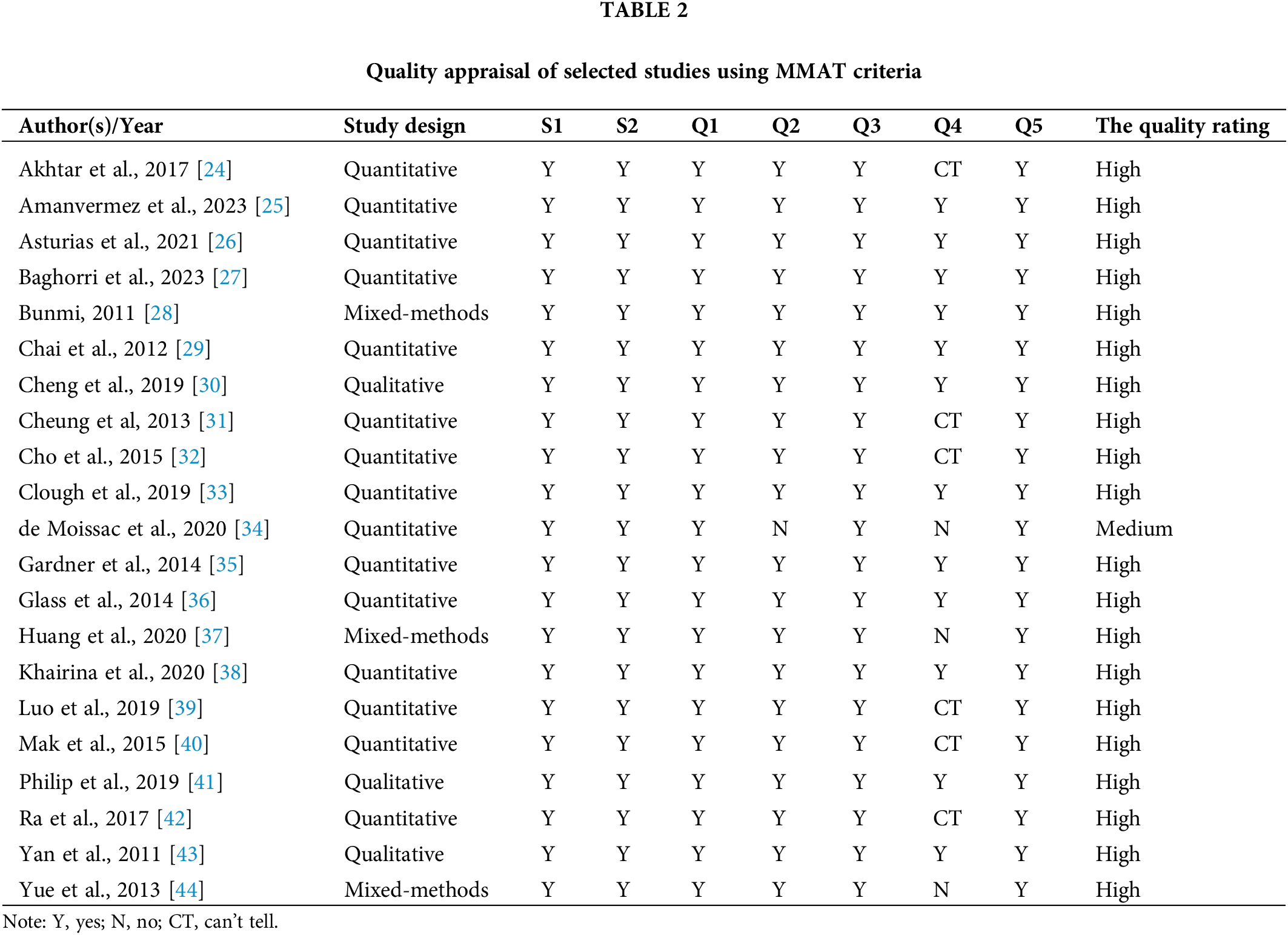

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (version 2018) [22] was used to examine included studies for methodological quality and relevance to the review question. The MMAT [22] is designed to appraise qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies. For each category of study, there are two screening questions and five methodological quality criteria relating to study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation. Studies with more than six ‘yes’ responses are considered high-quality, studies with five ‘yes’ responses are considered medium-quality and studies with four or fewer ‘yes’ responses are considered low-quality. Only high-quality and medium-quality studies were included in this review. Each study was appraised by three researchers independently. When a discrepancy was noted, researchers discussed the issue until a consensus was reached. Out of the 25 studies, 19 studies were rated as high-quality, and one was medium-quality. Only 5 studies were rated as low-quality and were excluded (see Table 2).

Data analysis and presentation

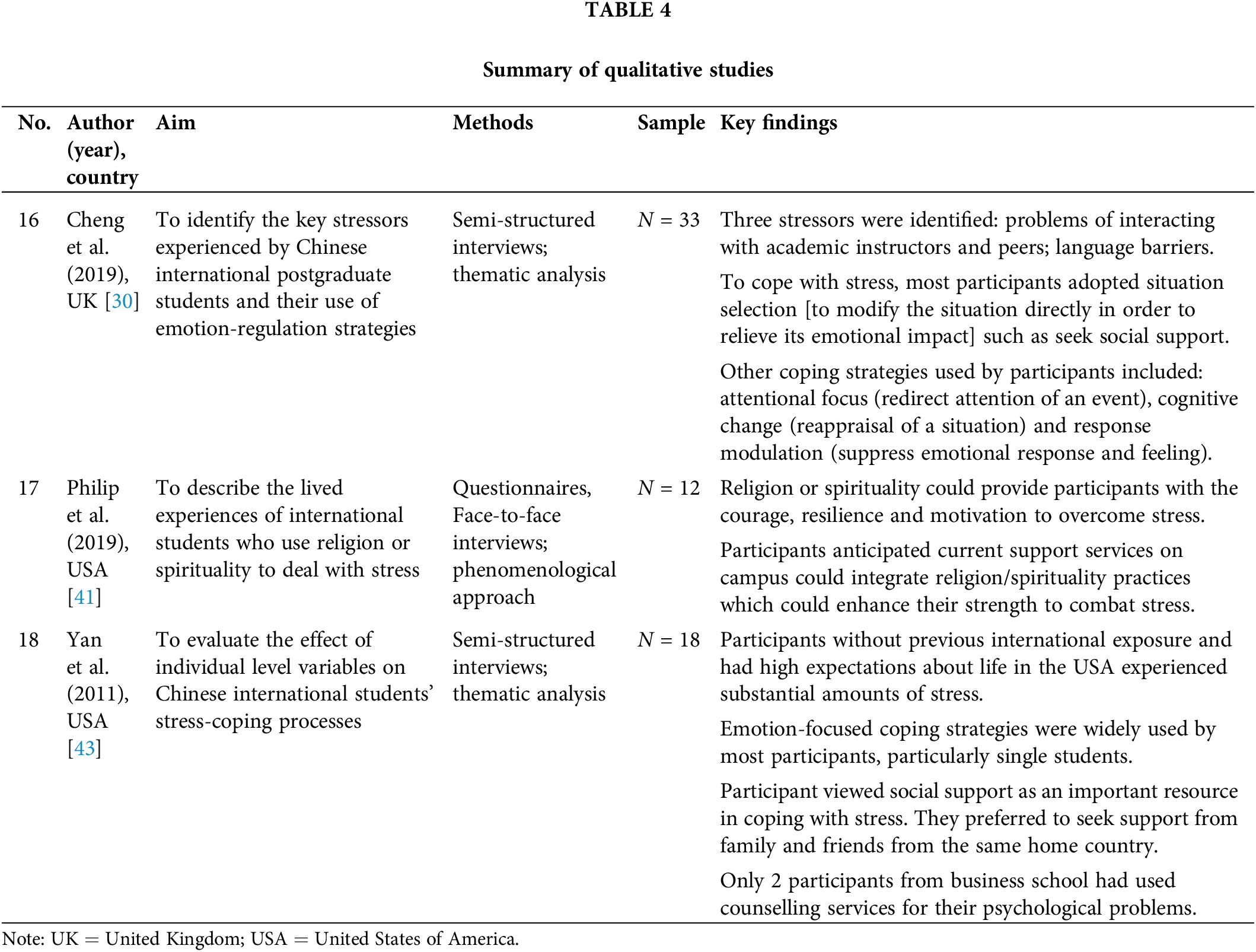

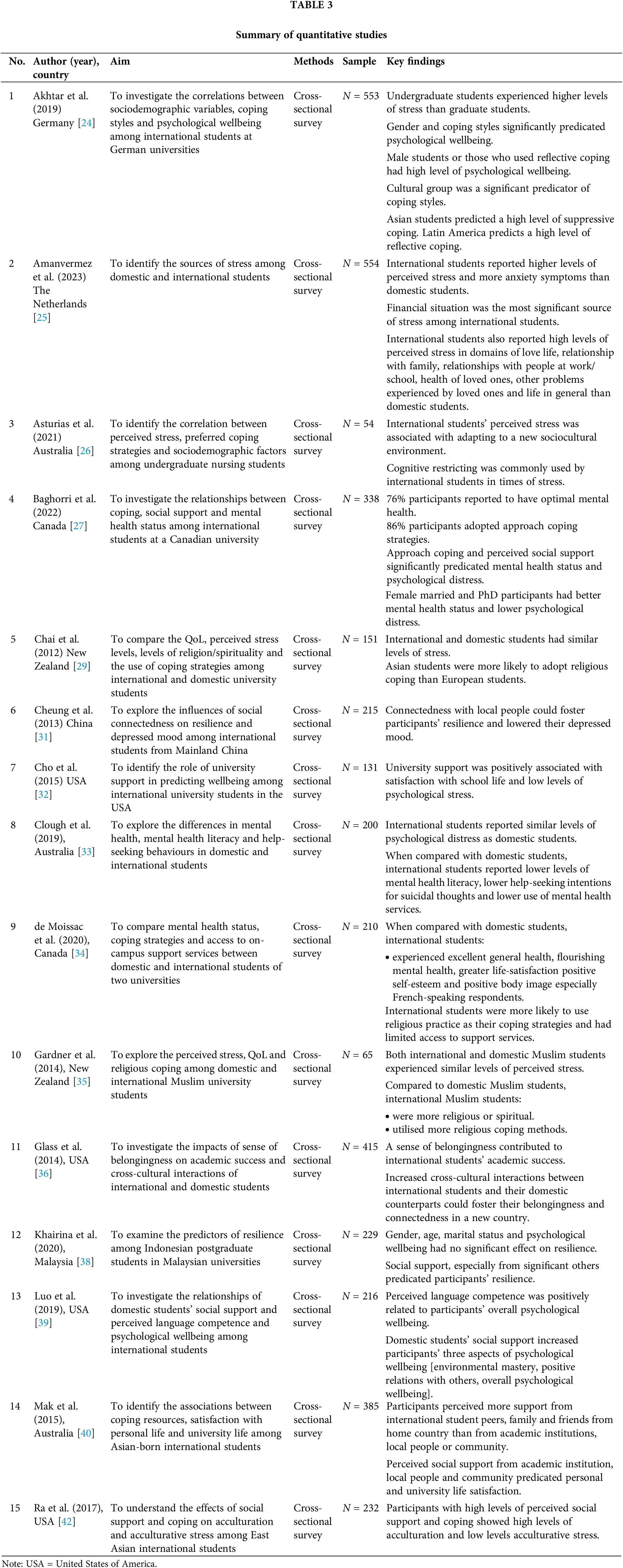

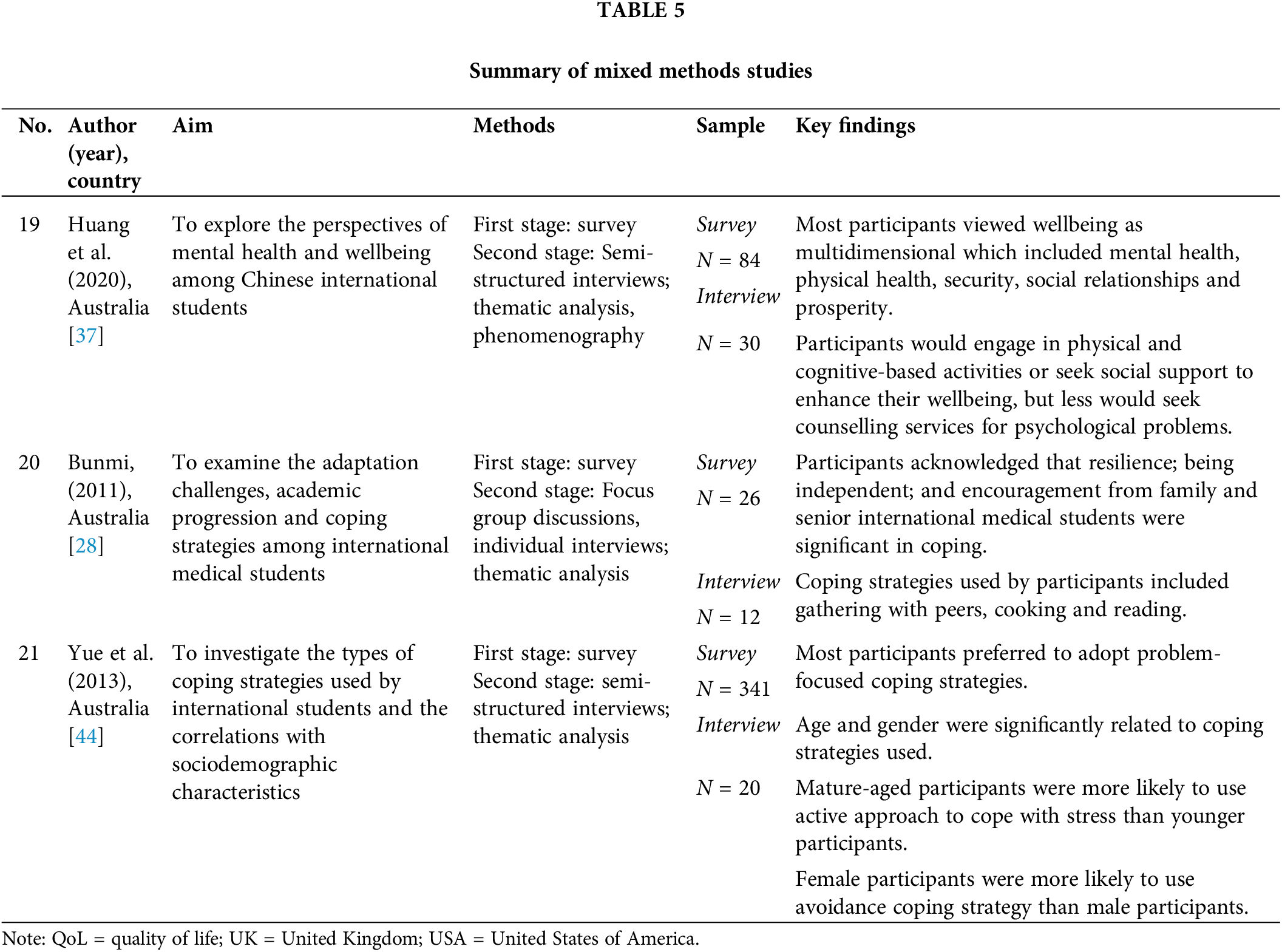

Key findings were extracted and organized using the data extraction form. Thematic analysis is a qualitative analysis method used in social sciences to identify and present recurring themes in data. It involves carefully reading and interpreting the material to extract meaning and understand different subjects and interpretations [23]. Thematic analysis was used to analyse data on international students’ perceived stress, coping strategies used, and factors associated with their utilization of mental health services. This included reading the studies, identifying the patterns of the data, generating codes, defining and organizing the themes and presenting the themes coherently [23]. Authors (CS, SC, MS, RL) reviewed and discussed the relationship of three identified themes based on the HBM [13] for accuracy and relevance of extracted data. Characteristics and key findings are summarized in Tables 3–5.

This review consisted of 21 studies: 15 quantitative studies, 3 qualitative studies and 3 mixed methods studies. These studies were conducted in the USA (n = 6), UK (n = 1), Australia (n = 6), New Zealand (n = 2), Canada (n = 2), Malaysia (n = 1), Hong Kong (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), The Netherlands (n = 1).

All quantitative studies (n = 15) adopted a cross-sectional design [24–27,29,31–36,38–40,42]. Sample sizes ranged from 54 to 554. Studies explored stress and coping (n = 5), coping and psychological wellbeing (n = 2), mental health and wellbeing (n = 3), social support and resilience (n = 2), sense of belongingness and connectedness (n = 1), social support and psychological wellbeing (n = 1), coping, social support and mental health status (n = 1).

All qualitative studies (n = 3) used semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions to collect data focusing on stress and coping [30,41,43]. Sample sizes ranged from 12 to 33. Two Studies used thematic analysis (n = 2) and thematic analysis with a phenomenological approach (n = 1).

Of mixed methods studies (n = 3) [28,37,44], two studies used a questionnaire survey, and one study used an online survey to collect data. To gather qualitative data, two studies conducted individual interviews and one study used focus group discussions, followed by individual interviews one week later. In all studies, quantitative data were collected prior to conducting qualitative interviews. Survey findings were used to guide the development of interview questions. Content analysis, thematic analysis and phenomenological approach were used to analyse data, respectively. Sample sizes ranged from 26 to 341 and 12 to 20 in quantitative and qualitative phases, respectively. Studies explored perceptions of mental health and well-being (n = 1) and coping strategies (n = 2).

Characteristics of international students

Of the 21 studies, a total of 4442 international students were recruited, with ages between 17 to 43 years. Nineteen studies reported international students’ gender, there were more females (n = 2205) than males (n = 1022). Ethnicity was reported in 18 studies. They included Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America, South America, Africa, Middle East and Pacific Island [24,25,27–32,34–43]. Most international students were from Asia. Six studies stated international students’ subject of study [24,26–28,33,43]. They included natural science, social science, applied science, humanities, law, business, nursing, medicine, dentistry, rehabilitation, psychology, art, engineering and education. Seventeen studies revealed academic degrees, including diploma, bachelor, master and doctorate programs [24–28,30,31,33,36–44].

Eleven studies reported on the duration of stay in the host countries which ranged between 1 month to 22 years [24,27,31,32,35,37,40–44]. Four studies reported on marital status with most international students ‘single’ [27,34,38,43]. Religious beliefs were reported in three studies and included Agnosticism, Christianity, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam [29,34,41]. Most international students were self-reported as Christians. Only two studies mentioned financial status, with sources of financial support including scholarships, parents/family, personal savings and earnings [24,34].

This review found diverse backgrounds of international students entering different host countries. They included international students from Asia, Africa, Europe, Central America, South America, the Middle East and the Pacific Islands included in studies conducted in North America (Canada and the United States) and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand) [27–29,32,34–37,39–42]. For Europe studies (Germany and the Netherlands), recruited international students from Asia, Europe and Latin America (24, 25, 30). Studies conducted in Asia (n = 2) (Hong Kong and Malaysia), recruited international students from China and Indonesia [31,38].

Three themes were identified via thematic progression. Thematic progression refers to the way themes interact with each other [45]. The HBM [13] was used to explain relationships among independent and dependent variables and guide the findings of this review. The three identified progressive themes included understanding cultural variations with perceived stress (Theme 1); coping strategies in dealing with stress and challenges in the new environment (Theme 2); and perceived threats and stress affecting how international students perceived barriers and benefits to access counselling support services and mental health services (Theme 3).

Theme 1: Embracing cultural variations

International students embraced differences in new learning cultures including language difficulties, new environments and academic expectations in host countries. The present review identified international students encountered difficulties in learning language [26,28,39,41,43], adapting to new environments [25,30,41–43], and academic demands [28,30,41]. International students embraced diversity by being aware of cultural distinctions and sensitivities of new cultures regarding local customs and traditions.

Dealing with language difficulties in the host country

For new international students, the first challenging issue was overcoming host language difficulties. Bunmi [28] found international medical students had difficulties in understanding Australian accents which significantly influenced their learning experiences. Another qualitative study identified host language difficulties may intensify psychological burdens among international students, particularly when their majors require higher levels of linguistic skills [43]. Host language difficulties were found to be an obstacle for international students when communicating with domestic peers and academic instructors. Several studies showed host language difficulties, fear of being misunderstood or making grammar mistakes may result in socialization difficulties among international students. It might also increase their hesitation to fully engage in academic activities [26,28,41,43]. Luo et al. [39] found that perceived language competence was positively related to international students’ psychological well-being and relationships with others.

Dealing with a new environment

International students in new environments experience differences in personal, social/cultural values and financial issues. Included studies report international students faced difficulties navigating new social customs and norms in the host country. This resulted in issues connecting with local people, leading to loneliness and feelings of exclusion [30,42,43]. International students further experienced a sense of cultural conflict in the host country, influencing their self-perception of identity [41,42]. They also faced financial issues while pursuing their education abroad. Amanvermez et al. [25] reported international students perceived financial pressures as the major source of stress, followed by health problems of loved ones. The inability to provide immediate support to loved ones caused significant amounts of stress [25]. Additionally, employment restrictions and limited job opportunities further limited financial support in their host country, contributing to high levels of stress.

Dealing with new expectations in academic

Adapting to new educational systems, teaching methods, learning styles and academic demands is overwhelming for international students [28,30,41]. Cheng et al. [30] reported most Chinese international students in the United States struggled with an active learning style, a style which encourages students to explore new knowledge and develop critical thinking. Bummi [28] identified academic challenges faced by a group of international medical students related to adjusting to new Australian healthcare systems, rigorous coursework and medical training. A cross-sectional study by Asturias et al. [26], reported international nursing students perceived clinical placement as a significant academic challenge and resulted in moderate amounts of stress.

Theme 2: Adopting coping strategies in dealing with challenges

International students in new environments adopted varying strategies to thrive and cope with challenging situations. Coping strategies included connecting with host culture to address underlying challenges that were causing stress [24,26–28,30,41–44]. Numerous studies report students would avoid problems causing stress, seek social support or engage in religious/spiritual practices [26–35,38,40–44]. These strategies also helped students regulate emotions.

Connecting with the host culture

Connecting with host culture to develop meaningful relationships with local people was perceived as most appropriate by international students [28,30,36,42]. This review highlights cross-cultural interactions with domestic students may foster a sense of belonging and connectedness in the host country, potentially leading to academic success [36]. Support from local peers increased life satisfaction, facilitated adaptation, and reduced psychological distress among international students while studying abroad [43]. However, lifestyle and cross-cultural differences created barriers for international students when trying to connect with local people [28,41,43]. A qualitative study found older international students [compared to younger ones] tend to adhere to their own social and cultural norms. This resulted in difficulties integrating into the host culture.

Solving the root causes of stress

International students manage stress in numerous ways [24,26,27,44]. Cheng et al. [30] reported that Chinese international students would change their study habits to minimize stress caused by academic demands. Akhtar et al. [24] reported that international students from Latin America take concrete steps to resolve problems. They also reported higher levels of psychological well-being than Asian and European international students. Baghoori et al. [27] reported that female and international doctoral students tended to actively solve their problems and stated better mental health status and lower psychological distress.

Avoiding the problems of stress

Akhtar et al. [24] reported that Asian international students tend to avoid coping activities and denied experiencing problems. They also demonstrated low levels of psychological well-being. Another study demonstrated that international students used distraction as a technique for thinking about problems and this technique was reported as being effective for providing temporary emotional relief [44]. Conversely, some international students accepted reality or changed their mindset when dealing with events that were beyond their control [44].

Several studies identified positive effects of perceived social support on stress and psychological well-being [26,31,32,42,43]. In three quantitative studies, international students with greater perceived social support from family, friends, significant others and university reported higher levels of psychological well-being, lower levels of acculturative stress, lower levels of psychological stress, better personal satisfaction and better satisfaction with university life [27,32,40,42]. Three studies stated international students would seek support from family, peers and church members as they provided them with practical information about new environments and emotional comfort [27,28,43]. Kharinia et al. [38] and Cheung et al. [31] found that perceived social support could foster resilience regarding coping with new environments in international students’. This review identified family members and friends were common sources of social support for most international students, followed by church members and counsellors [27,33,34,43]. Yan et al. [43] reported that Chinese international students were less likely to seek emotional support. In addition, the social stigma of mental health-related issues may prevent Chinese international students from seeking external psychological support. Another study conducted by Baghoori et al. [27] highlighted gender differences in perceived social support among international students. They report male international students had less perceived social support than female peers. This research discussed this finding may be related to men’s masculinity which emphasized self-reliance and emotional restraint. They report male international students tend to manage challenges on their own and avoided seeking advice and support from others [27].

Using religious/spiritual coping

Several studies reported that religious/spiritual coping may benefit international students by supporting their resilience, providing a sense of empowerment, comfort and direction to solve encounters and enhance mental well-being [29,34,35,44]. Religious and spiritual practices were particularly important for international students who might fear being judged when seeking help [41]. Some studies showed that religious/spiritual coping played a key role in alleviating stress caused by uncontrollable events such as homesickness, and cross-cultural differences [26,30,44]. Gardner et al. [35] highlighted a positive relation between religiously/spirituality and perceived stress among international Muslim students. Highly religious/spiritual students reported lower levels of perceived stress than those who were less religious. Two studies report engaging with religious/spiritual communities became a social resource that helped Chinese international students develop or expand social support in a new environment [43]. International students from various religious/spiritual backgrounds had different practices specific to their faith. Muslim students practised scripture reading and prayer, while Buddhist students performed chanting and meditation. Christian students would practice belief in God and spend time with church members. Yoga and meditation were common religious activities adopted by Hindu students [41].

Theme 3: Encountering barriers to accessing mental health services

Three barriers were identified in this review that hindered access to mental health services among international students in host countries including stigma of mental health, awareness of mental health issues, and culturally sensitive services.

Confronting the cultural stigma of mental health

Cultural stigma was found to be one of the biggest impediments to approaching and utilizing mental health services among international students. Even with awareness of mental problems, international students were still reluctant to seek help. Numerous studies report high stigmatization of mental health issues in some cultures which discouraged international students from approaching mental health services [33,34,37,43]. Yan et al. [43] reported that Chinese international students were concerned about bringing dishonour to their families if they sought help from health professionals. Additionally, the fear of being labelled as a ‘loser’ and the negative repercussions from peers deterred health-seeking behaviours. Huang et al. [37] further reported that stigma created feelings of shame leading to a reluctance to disclose their concerns with counsellors. Clough et al. [33] found that international students demonstrated lower mental health literacy, poorer help-seeking attitudes and lower help-seeking behaviours than domestic students, particularly relating to suicidal thoughts.

Recognizing mental health issues

A correlation between mental health knowledge and help-seeking behaviours among international students was reported in two studies. Results demonstrated that international students with low mental health literacy were unlikely to access mental health services [33,34]. Research suggests that international students with limited knowledge of mental health may lack awareness surrounding the signs and symptoms of mental health problems and the potential consequences of a delay in seeking help [34].

Lacking culturally sensitive support services

de Moissac et al. [34] reported that a lack of available mental health services in their native language may be a barrier discouraging participants to access/utilize mental health services. Another study reported a similar issue in that some international medical students were aware of available mental health services on campus, however, were unable to find the right person to discuss their concerns with [28].

This integrative review explored a variety of challenges and stressors international students experience in host countries, ways of coping, and barriers associated with the use of mental health services. Most included studies [n = 15] in this review were conducted in prominent countries with proven historical enrolments of international students [46]. This suggests a lack of research in several countries that have become popular destinations of international study in the present including the United Arab Emirates and Mexico [47,48]. Interestingly, the findings on the ethnicity of international students in this review were diverse. However, sample sizes of those participants from regions including Africa, the Pacific Island and the Middle East were relatively small, resulting in gaps in of understanding student needs and experiences. This may be explained by the higher enrolment numbers of Asian international students, which made them a prominent group for research when compared with other populations [49].

Perceived stress in the host country

Regarding the HBM, perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits and barriers provide cues in explaining or predicting people’s health-related behaviours [13,50]. Perceived susceptibility refers to individuals’ beliefs regarding the likelihood of having a health problem or issue [51]. For international students, their perceptions of stress were interconnected with their beliefs about susceptibility to stressors. Perceived stress is a psychological response to stressors which occurs when there is an imbalance between the environmental demands and a person’s coping capacity [52]. This review identified how international students perceived their stress as correlated with different domains including language, sociocultural, financial, interpersonal and educational.

This review found international students with host language difficulties were less actively engaging in-class activities and interacting with academic providers and peers. Prior studies highlighted that host language difficulties created barriers to adjustments in new academic and social environments [53–55]. The struggle to express ideas fluently in the host language and the fear of being misunderstood may contribute to international students’ reticence during class activities [56]. Host language proficiency further predicated international students’ abilities to relate to others. Host language difficulties may lower self-esteem and confidence among international students making it harder for them to develop rapport and relationships with academic advisors, other students and locals [57,58]. Such relationships may provide international students with a sense of connection and belonging to the host environment [59,60]. A sense of connection and belonging may provide an easier adjustment to life in a new country, increased engagement at university and improved academic performance [60–62].

Apart from host language difficulties, differences in cross-cultural values and social norms may be viewed as obstacles for international students via the formation of friendships in the host country [63]. Past studies report international students had difficulties in forming relationships with local students due to cross-cultural differences [64–66]. A study revealed international students who had satisfactory relationships with domestic peers demonstrated lower levels of stress [67]. In line with previous research, international students in this review faced difficulties in rebuilding social networks in a different sociocultural environment. Support from local peers was significant in increasing life satisfaction and psychological well-being. The journey of adapting to a new sociocultural environment may be stressful for international students due to navigating a balance between maintaining their home culture and adapting to the new culture of their host country. This may be explained by diverse cultural disparities, identity negotiation and feelings of helplessness [66,68]. Poor sociocultural adaptation was found to be significantly related to lower well-being, increased psychosomatic symptoms and anxiety [69]. Gebregergis et al. [70] highlighted prior travel experience played a positive role in facilitating international students’ sociocultural adaptation in host countries. Previous travel experience is known to prepare international students with realistic expectations and psychological readiness for sociocultural challenges [71,72]. It is imperative to increase cross-cultural understanding for international students and strengthen adaptive abilities. Promoting cross-cultural competence and adaptability may help international students better integrate into the host culture and promote meaningful connections with peers and locals within host countries.

In this review, a group of international students in the Netherlands perceived financial concerns as a major source of stress in the host country. Similar to Johnson’s [73] findings, 60% of international students in the United States report financial problems were the most frequent source of stress in the past 12 months. Financial hardship may have a profound impact on the mental health of international students. International students may need to invest significant amounts of financial resources to pursue education abroad. Financial worries as well as the pressure to fulfil academic requirements may have profound impacts on mental health [74,75]. It may also be challenging for international students to access financial aid in host countries. To alleviate financial stressors, host universities may consider increasing the number of scholarships on offer and establishing partnerships with local companies to increase job opportunities. Within communities, collaboration with local supermarkets to provide affordable groceries to international students may be advantageous.

This review identified concerns about health-related problems of loved ones as an important source of stress among international students. Being physically distant from family and loved ones may place international students at increased risk of mental problems. Harvey et al. [76] reported international students often experience negative emotions due to leaving their spouses and children in their home countries. Another study reports gender differences in emotional stress associated with distancing from family. Male international postgraduate students compared to females were less likely to experience emotional stress or distress [77]. In contrast, Brown [78] found distance from family and loved ones promoted greater independence and personal self-discovery in younger international students. Living away from family and loved ones may impact the psychological and emotional states of international students. Future support programs should prioritize emotional self-regulation skills that may help students improve their emotions while studying abroad.

According to Chen [79], educational stressors involve system adjustment, performance expectations and test-taking anxiety. Most international students in this review struggled with adjusting to unfamiliar educational environments, different teaching styles and learning methods as well as managing academic workloads. It may be critical for international students, particularly those coming from educational backgrounds where rote memorization and passive learning were prevalent, to adapt to Western universities where critical thinking and interactive learning are highly valued [80,81]. In Western education, students are encouraged to learn independently, to actively participate in class activities, and to critically appraise ideas discussed in class. Conversely, teachers in East Asian countries tend to dominate the learning process. Asking questions or sharing personal opinions is perceived as disrespectful to teachers and further disrupts class [82]. Evidence shows some educators view Asian international students as lacking independent analytic skills and creativity, with a noted lack of engagement towards local students [83,84]. Differences in educational cultures may affect international students’ relationships with academic providers and domestic peers, increasing levels of stress. To overcome this, providing international students with information regarding expectations of educational systems, and learning and teaching styles of host countries is ideal. Likewise, increasing awareness of cross-cultural differences in educational systems to host country academics may help create a supportive and inclusive academic environment.

This review highlights a correlation between international students’ susceptibility to stress and demands in new academic and sociocultural environments. Findings in this review were frequently numerical data. International students’ subjective experiences and interpretations of stressors within their cultural context may be overlooked. Further research should incorporate both qualitative and quantitative approaches to holistically acquire an understanding of cultural variations of stressors among international students. Acknowledging cultural variations in stress perception will assist mental health providers and academic institutions in creating culturally sensitive support services that empower international students to navigate stressors.

Navigating challenges and stress

Within the HBM, perceived severity is a person’s belief associated with the severity of a health problem and its potential consequences to his or her daily functioning [51]. Recognizing the severity of a situation may motivate individuals to take steps to mitigate health risks and to consider the benefits of taking action [51]. Perceived benefit is described as an individual’s beliefs regarding the effectiveness of particular behaviours or actions in minimizing the risk of health issues and improving health outcomes [51]. When international students perceived the severity of stress that influenced their mental health to be high, it motivated them to engage in varying coping strategies to enhance or improve their emotions and mental health status. Coping is important for international students as it enables them to navigate challenges more effectively and to promote positive psychological outcomes [85,86]. Coping refers to the thoughts and behaviours that people make to deal with stressful situations [85].

There were two general types of coping strategies: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping highlighted in this review [87]. Problem-focused coping includes active efforts to eliminate the sources of stress; whereas emotional-focused coping involves efforts to alleviate emotions associated with stress [87]. People from different cultures may have unique coping preferences based on cultural beliefs and values [88]. This review found Latin American international students tend to tackle problems related to stress in comparison to those students from Asia and Europe. In European and Northern American countries, people often conform to values of personal autonomy, self-reliance and independence. Here they are inclined to take active approaches to control/manage the environment [88,89]. Asian cultures demonstrate similar strategies emphasizing emotional restraint and avoiding discussing their struggles openly [90]. Consistent with this review, Asian international students reported frequent use of emotional regulation strategies in response to stressors or difficult situations. This review also found that mature-aged international students were more likely to initiate actions to alter stressful circumstances than their younger counterparts. Review findings suggest older students may know a wider range of cognitive, emotional and behavioural strategies leading to direct approaches in managing stress [91]. In terms of gender, female international students in this review exhibited greater tendencies to engage in passive or avoidant emotional coping strategies in handling stressful situations. Females may value interpersonal relationships than males leading them to seek support, rather than address stressors directly [92]. It might not be possible to draw a conclusion about which coping strategy is more effective than another as these two coping strategies may be equally effective in helping international students cope.

Most studies in this review focused on gender, age and ethnicity associated with coping. Indeed, other demographic characteristics such as personality, academic discipline, prior overseas experience and economic status may shape coping among international students. Previous research identified that enrolled psychology students report higher levels of coping than non-psychology students [93]. Research often overlooks how the interplay of various demographic characteristics determines coping among international students. There is a paucity of longitudinal research examining the coping processes of international students. Longitudinal studies may help capture how international students adjust their coping skills over time, with results potentially informing mental health support programs and services address the changing needs of this population.

Social support as a coping strategy

This review indicated international students often sought social support when encountering difficult situations. Social support refers to the availability of concrete and psychological resources that are perceived and received from interpersonal relationships [94]. These resources include emotional support [empathy and encouragement], informational support [advice and guidance], practical support [material resources, financial aid and needed services] or social companionship support [a sense of belonging to a social group] [87]. Social support offers empathy, comfort and practical assistance which may shape an individual’s evaluation and management of stress [87]. People with strong social support systems are likely to perceive stressful events as less threatening and increase their abilities to cope. The protective role of social support in mental health has been reported in various studies [95–97]. This review yielded similar results with increased social support leading to better mental health and wellbeing in international students. Family and friends were frequently cited in previous literature as the main source of social support [53,98,99]. Culture may significantly determine how people select their sources of social support [100]. Collectivistic culture emphasizes interdependence and familial ties. People from this cultural background [mostly Asia, Africa and the Middle East] tend to interact with or maintain relationships with family [101]. In line with this review, Chinese international students sought emotional support and advice from family when confronted with stress. The shared cultural ties and empathy may provide international students with a sense of safety and belonging [53,102]. One study in this review highlighted female international students sought more social support than male counterparts. Prior research suggests females have higher levels of social skills and hence, may receive more social support than males [103]. Another explanation is possibly related to females demonstrating a higher willingness to share their feelings when compared with males [104].

Ng et al. [102] highlighted that the importance of supportive relationships with local people. This review identified having strong social bonds with local people may increase a sense of belonging and connection among international students to host countries. Local people may provide practical support such as language assistance and cultural knowledge that influence an international student’s academic and sociocultural integration [102,105]. This review found cross-cultural differences may be an obstacle to both international and domestic students in building supportive relationships. To bridge the gap, academic institutions may implement campaigns to promote cross-cultural exchange.

Institutional support plays an important role in promoting international students’ academic success and social life [106]. Haslam et al. [107] reported that international students felt less stress with positive coping when they received cross-cultural institutional support. When international students received support from their institutions, they were more likely to have better life satisfaction and less stress. Similarly, this review found positive roles of university support resulted in increased school-life satisfaction and psychological well-being. Most studies in this review focused on seeking interpersonal support for international students, with only one study focused on university support using a quantitative approach. Thus, more qualitative research is needed to explore international students’ experiences and expectations of institutional support. This will provide insights that can guide academic institutions in planning and implementing mental health support services that can address the actual needs of international students.

In addition to seeking social support, this review found international students engaged in different religious/spiritual practices when dealing with adversity. Religious/spiritual coping refers to the use of religious or spiritual practices, beliefs and resources to overcome stress [108]. Being away from familiar supportive networks, and religious and spiritual practices might provide intentional students a sense of belonging, hope and guidance to deal with hardships [109]. Hence, universities may wish to consider integrating religious/spiritual support into existing mental health support and counselling services for international students.

This review revealed social support and religious/spiritual practices might help international students develop resilience. Resilience refers to the ability to recover from stressful circumstances and adjust to the environment [110]. Resilient people often have positive mindsets, confidence, strong problem-solving skills and the capacity to navigate challenges, hardships and failures. Therefore, resilience is perceived as a protective factor for mental health [111,112]. This review yielded similar results. International students who were highly resilient demonstrated a lower depressed mood. Studies reported resilience may be predicted by multiple factors. For instance, personal characteristics such as cultural origin, coping styles and social connectedness [113–115]. Further research is needed to explore how international students build resilience and explore factors that may contribute to it. Such understanding may guide the design of interventions or programs that foster resilient development among international students.

Obstacles of mental health help-seeking

According to HBM [13], perceived barriers, involve evaluations of obstacles or difficulties which may inhibit people from undertaking particular health actions. This review identified international students’ willingness to use mental health support services are correlated with cultural, psychological and institutional barriers.

Regarding cultural barriers, this review found host language difficulties significantly hindered access to mental health services among international students. International students may struggle with articulating their ideas, feelings and worries in the host language.

Psychological barriers including mental health stigma and mental health literacy might create hurdles to utilising mental health services among international students in this review. Cultural stigma may affect aspects of mental health including emotional expression, awareness of mental health issues and seeking mental health support [12,116]. Mental health stigma was endorsed in many cultures. The majority of people in Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean perceived mental health as dangerous, shameful, a weakness, and failure [117]. Such prejudice and discrimination may result in a reluctance to address mental health issues openly and deter help-seeking [117,118]. In some cultures, mental health issues are often rooted in religion and supernatural beliefs. In African culture, mental health may be attributed to supernatural causes like bewitchment and ancestral spirits, leading people to fear negative judgements from their communities. People may also turn to alternative help for mental health issues including rituals and spiritual guidance [119]. In Middle Eastern cultures, mental health may be perceived as a lack of religious commitment or faith that results in shame and hinders help-seeking [120]. Individualism is rooted in most European and American cultures. Individualism emphasizes personal autonomy, independence and individual success. This may empower individuals to seek help and disclose mental health issues without fear of judgement [121]. Consistent with review findings, Chinese international students were less likely to seek mental health support due to fear of being judged as incompetent, coupled with family shame. Previous studies found international students may conceal mental issues or wouldn’t seek formal help until the issue became severe or unmanageable [122,123]. This review identified mental health stigma associated with help-seeking in Chinese international students only. Further studies are needed to examine and compare mental health stigma across Muslim different ethnic groups. As international students interact with a new sociocultural environment, it may have profound effects that shape perceptions of help-seeking. Thus, there is a need to further explore this issue.

Mental health literacy involves knowledge and beliefs about mental problems the ability to recognize mental health needs and awareness of available treatments and resources [124]. Evidence shows mental health literacy predicted university students’ likelihood to seek help [125,126]. In line with this review, international students with low mental health literacy demonstrated poor help-seeking attitudes and low intentions to utilize mental health services. However, the results did not conclude whether a causal relationship existed between these variables. Understanding the causal relationship may help identify the root cause or other potential factors related to the utilization of mental health services. Moreover, people with limited mental health knowledge may fail to recognize their mental health needs, thus reducing intentions to seek support [127]. It is reported international students were less likely to self-report mental health which may relate to stigma or misconception of emotional and mental issues as physical problems [10,128]. More research is needed using qualitative and mixed methods approaches to explore gaps in international students’ mental health knowledge and awareness of mental health services. Such findings may be significant in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions and identifying areas of improvement.

This review found a lack of cultural sensitivity in mental health services was a crucial institutional barrier associated with international students’ help-seeking behaviours. Cultural sensitivity concerns understanding, awareness and acceptance of different cultures and identities [129]. Aligned with previous studies [122,130,131], international students reported they encountered difficulties in identifying an appropriate person to disclose emotional and mental health issues. This may indicate a lack of culturally sensitive programs that address mental health needs [132]. Furthermore, this review identified a requirement for educational and healthcare professionals to possess the necessary skills and knowledge to ensure tertiary education settings continue to be beneficial environments that promote mental health and emotional well-being. Competent counsellors and mental health providers should equip the required skills and knowledge to deliver appropriate mental health programs on campus for international students. Familiarity with shared cultural norms may offer international students a sense of comfort and safety, particularly when discussing sensitive mental health issues. Mental health training is commonly guided by Western psychological theories and frameworks, which may be inadequate to address the unique needs of international students [133]. This highlights a need to provide ongoing training focused on cultural competence for counsellors and mental health providers.

This review has several limitations. Most studies were conducted using a quantitative approach, indicating a lack of participants’ lived experience about the research phenomenon. Not all research questions, designs and data generated from the included articles are transparent and rigorous enough to reach comprehensive and reliable conclusions as suggested by Toronto et al. [134]. None of the included studies used longitudinal design. Thus, only associations between study variables (not causality) can be concluded. Moreover, several countries have become increasingly popular for overseas education in recent years including China and the Arabian Gulf due to affordable education and the availability of fully funded scholarships for international students [135,136]. Indeed, included studies focused on a few prominent countries that host many international students. This may limit the understanding of mental health issues among international students across the globe. Furthermore, the search was limited to articles published in English and may omit important evidence published in other languages.

Implications for future research and practice

This review identifies several knowledge gaps. They include: i] The undertaking of mixed-method research is necessary to understand cultural variations in perceived stress. Past research supports adopting such methods as the approach will contribute to a holistic view of the intersections of cultures and psychology [137]; ii] In considering international students’ unique sociocultural characteristics, it is worth investigating differences in academic disciplines, economic status, personality, prior overseas experiences as factors when examining influences if coping mechanisms and help-seeking behaviours; iii] There is a paucity of research regarding how international students build a sense of belonging and connection in host countries; iv] Existing research seems to not fully capture the development of resilience of international students. Longitudinal research may be fruitful here as resilience may change and develop over time [138]; v] Mental health literacy generally tends to be lower in Asian and African cultures compared to European and North American cultures [139]. Further research should address cross-cultural differences in mental health literacy, awareness of supporting resources and attitudes toward help-seeking among international students.

The findings of this review have shown positive effects of culturally sensitive promotion in areas of coping skills, help-seeking skills, social skills, emotional regulation and reduction of symptoms associated with low-level depression and anxiety. Any improvements to mental health and emotional well-being may reduce the likelihood of mental health problems developing or improve one’s ability to cope with future mental health problems, whether that be via stress management or positive help-seeking. Considering this, all available opportunities must be taken to promote mental health and emotional well-being interventions to young people in school environments—particularly through using a culturally sensitive approach. International students deal with different kinds of challenges and emotional struggles while studying abroad. It is important they feel a sense of belonging, support and connection to host countries. Current mental health support strategies focus primarily on cultural adjustment and stress management techniques [140,141]. How a sense of belonging and connection contribute to the cross-cultural relationships of international students and academic success are essential aspects for future research. Policymakers, academics and mental health practitioners need to develop resilience-based models of acculturation and propose mental health interventions that enhance belongingness and connection among international students.

This integrative review presents an overview of mental health needs and factors contributing to the mental health and well-being of international students via the inclusion of studies with different designs, providing an in-depth understanding of the study phenomenon. The findings of this review may help university health providers, mental health professionals, academic institutions and policymakers better understand the multifaceted needs of international students. This review demonstrates the importance of increased cross-cultural interactions between international students and domestic student counterparts to enhance belongingness and connection to host countries. This may facilitate adaptation to new living and learning environments. It is crucial academic institutions offer programs that can be effectively implemented and sustained to meet the unmet mental health needs of international students. University orientation programs, student counselling and health services may integrate cultural events, social support groups, leadership programs and resilience models of acculturation to promote mental health and wellbeing. It is concluded that while these studies show promising results, there is a need for further robust evaluative studies to develop culturally sensitive mental health promotion programs for international students.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the two university librarians for providing their professional advice.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Carmen Hei Man Shek, Regina Lai Tong Lee and Sally Wai Chi Chan conceptualised, designed, searched, reviewed, analysed and wrote the original draft of this review. Carmen Hei Man Shek, Regina Lai Tong Lee, Sally Wai Chi Chan and Michelle Anne Stubbs reviewed and edited the final manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original contributions presented in the study are included in the Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia (Reference Number: H-2022-0397). All participants signed the informed consent in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2024.055706.

References

1. Yuerong C, Susan LR, Samantha M, Joni S, Anthony TS. Challenges facing Chinese international students studying in the United States. Educ Res Rev. 2017;12(8):473–82. doi:10.5897/ERR2016.3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Orygen. International students and their mental health and physical safety. Melbourne, VIC: Orygen; 2020. [Google Scholar]

3. Forbes-Mewett H, Sawyer A-M. International students and mental health. J Int Stud. 2016;6(3):661–77. doi:10.32674/jis.v6i3.348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Rettew DC, McGinnis EW, Copeland W, Nardone HY, Bai Y, Rettew J, et al. Personality trait predictors of adjustment during the COVID pandemic among college students. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248895-e. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Liu A, Yu Y, Sun S. How is the big five related to college students’ anxiety: the role of rumination and resilience. Pers Individ Differ. 2023;200:111901. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2022.111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Harris BR, Maher BM, Wentworth L. Optimizing efforts to promote mental health on college and university campuses: recommendations to facilitate usage of services, resources, and supports. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2022;49(2):252–8. doi:10.1007/s11414-021-09780-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Deasy C, Coughlan B, Pironom J, Jourdan D, Mannix-McNamara P. Psychological distress and coping amongst higher education students: a mixed method enquiry. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115193-e. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Orgeta V. Emotion dysregulation and anxiety in late adulthood. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(8):1019–23. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.06.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Alharbi ES, Smith AP. Review of the literature on stress and wellbeing of international students in English-Speaking countries. Int Educ Stud. 2018;11(6):22. doi:10.5539/ies.v11n6p22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Forbes-Mewett H, Sawyer A-M. Mental health issues amongst international students in Australia: perspectives from professionals at the coal-face. In: Proceeding from The Australian Sociological Association Conference Local Lives/Global Networks, 2011; University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. [Google Scholar]

11. Koo K, Nyunt G. Culturally sensitive assessment of mental health for international students. New Dir Student Serv. 2020;2020(169):43–52. doi:10.1002/ss.v2020.169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gopalkrishnan N. Cultural diversity and mental health: considerations for policy and practice. Front Public Health. 2018;6:179. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175–83. doi:10.1177/109019818801500203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Saint Arnault D. Cultural determinants of help seeking: a model for research and practice. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2009;23(4):259–78. doi:10.1891/1541-6577.23.4.259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Torraco RJ. Writing integrative literature reviews: using the past and present to explore the future. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 2016;15(4):404–28. doi:10.1177/1534484316671606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53. doi:10.1111/jan.2005.52.issue-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hopia H, Latvala E, Liimatainen L. Reviewing the methodology of an integrative review. Scandinavian J Caring Sci. 2016;30(4):662–9. doi:10.1111/scs.2016.30.issue-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

19. Dhollande S, Taylor A, Meyer S, Scott M. Conducting integrative reviews: a guide for novice nursing researchers. J Res Nurs. 2021;26(5):427–38. doi:10.1177/1744987121997907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Kraus S, Breier M, Lim WM, Dabić M, Kumar S, Kanbach D, et al. Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice. Rev Manag Sci. 2022;16(8):2577–95. doi:10.1007/s11846-022-00588-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Marshall IJ, Marshall R, Wallace BC, Brassey J, Thomas J. Rapid reviews may produce different results to systematic reviews: a meta-epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;109:30–41. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.12.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Educ Inform. 2018;34(4):285–91. doi:10.3233/EFI-180221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Akhtar M, Kroener-Herwig B. Coping styles and socio-demographic variables as predictors of psychological well-being among international students belonging to different cultures. Current Psychol. 2019;38(3):618–26. doi:10.1007/s12144-017-9635-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Amanvermez Y, Karyotaki E, Cuijpers P, Ciharova M, Bruffaerts R, Kessler RC, et al. Sources of stress among domestic and international students: a cross-sectional study of university students in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Anxiety Stress Copin. 2024;37(4):428–45. doi:10.1080/10615806.2023.2280701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Asturias N, Andrew S, Boardman G, Kerr D. The influence of socio-demographic factors on stress and coping strategies among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;99(6):104780. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104780. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Baghoori D, Roduta Roberts M, Chen S-P. Mental health, coping strategies, and social support among international students at a Canadian university. J Am Coll Health. 2022;8(3):1–12. doi:10.1080/07448481.2022.2114803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Bunmi SM-A. Exploring the experiences and coping strategies of international medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):40. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-11-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Chai PPM, Krägeloh CU, Shepherd D, Billington R. Stress and quality of life in international and domestic university students: cultural differences in the use of religious coping. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2012;15(3):265–77. doi:10.1080/13674676.2011.571665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Cheng M, Friesen A, Adekola O. Using emotion regulation to cope with challenges: a study of Chinese students in the United Kingdom. Cambridge J Educ. 2019;49(2):133–45. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2018.1472744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Cheung CK, Yue XD. Sustaining resilience through local connectedness among Sojourn students. Soc Indic Res. 2013;111(3):785–800. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0034-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Cho J, Yu H. Roles of university support for international students in the United States: analysis of a systematic model of university identification, university support, and psychological well-being. J Studies Int Educ. 2015;19(1):11–27. doi:10.1177/1028315314533606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Clough BA, Nazareth SM, Day JJ, Casey LM. A comparison of mental health literacy, attitudes, and help-seeking intentions among domestic and international tertiary students. In: Migration and wellbeing. 1st ed. Routledge; 2019. [Google Scholar]

34. de Moissac D, Graham JM, Prada K, Gueye NR, Rocque R. Mental health status and help-seeking strategies of international students in Canada. Canadian J High Educ. 2020;50(4):52–71. [Google Scholar]

35. Gardner TM, Krägeloh CU, Henning MA. Religious coping, stress, and quality of life of Muslim university students in New Zealand. Mental Health, Relig Cult. 2014;17(4):327–38. doi:10.1080/13674676.2013.804044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Glass CR, Westmont CM. Comparative effects of belongingness on the academic success and cross-cultural interactions of domestic and international students. Int J Intercult Relat. 2014;38:106–19. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.04.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Huang L, Kern ML, Oades LG. Strengthening university student wellbeing: language and perceptions of Chinese international students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5538. doi:10.3390/ijerph17155538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Khairina K, Roslan S, Ahmad N, Zaremohzzabieh Z, Arsad NM. Predictors of resilience among Indonesian students in Malaysian universities. Asian J Univ Educ. 2020;16(3):169–82. doi:10.24191/ajue.v16i3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Luo Z, Wu S, Fang X, Brunsting N. International students’ perceived language competence, domestic student support, and psychological well-being at a U.S. university. J Int Stud. 2019;9(4):954–71. [Google Scholar]

40. Mak AS, Bodycott P, Ramburuth P. Beyond host language proficiency: coping resources predicting international students’ satisfaction. J Studies Int Educ. 2015;19(5):460–75. doi:10.1177/1028315315587109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Philip S, Neuer Colburn AA, Underwood L, Bayne H. The impact of religion/spirituality on acculturative stress among international students. J Coll Couns. 2019;22(1):27–40. doi:10.1002/jocc.2019.22.issue-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ra YA, Trusty J. Impact of social support and coping on acculturation and acculturative stress of east Asian international students. J Multicult Couns Dev. 2017;45(4):276–91. doi:10.1002/jmcd.2017.45.issue-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Yan K, Berliner DC. An examination of individual level factors in stress and coping processes: perspectives of Chinese international students in the United States. J Coll Stud Dev. 2011;52(5):523–42. doi:10.1353/csd.2011.0060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Yue Y, Lê Q. Coping strategies adopted by international students in an Australian tertiary context. Int J Interdiscip Educ Stud. 2013;7(2):25–39. [Google Scholar]

45. Hawes T. Thematic progression in the writing of students and professionals. Ampersand. 2015;2(C):93–100. [Google Scholar]

46. International Consultants for Education and Fairs (ICEF). How diverse is the international student population in leading study abroad destinations? 2024. Available from: https://monitor.icef.com/2024/08/how-diverse-is-the-international-student-population-in-leading-study-abroad-destinations/. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

47. Watkins J. The student: the best-value countries to study abroad. 2023. Available from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/news/best-value-countries-study-abroad. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

48. Batra G. Study abroad: how policies in popular countries are redirecting students toward alternative options. 2024. Available from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/education/features/study-abroad-how-policies-in-popular-countries-are-redirecting-students-toward-alternative-options-101724659236862.html. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

49. Guillerme G. International student mobility at a Glance 2023. 2023. Available from: https://timeassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Global_analysis_data_Oct_2023_G_Guillerme.pdf. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

50. Champion VL, Skinner CS. The health belief model. Health Behav Health Educ: Theory, Res Prac. 2008;4:45–65. [Google Scholar]

51. Henshaw EJ, Freedman-Doan CR. Conceptualizing mental health care utilization using the health belief model. Clin Psychol. 2009;16(4):420–39. [Google Scholar]

52. Lazarus RS. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am Psychol. 1991;46(8):819–34. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Pinarbasi G. International students’ sociocultural adaptation experiences: their perceived stress and coping strategies. Acad Soc Res J. 2023;8(55):4059–80. [Google Scholar]

54. Wang KT, Heppner PP, Fu C-C, Zhao R, Li F, Chuang C-C. Profiles of acculturative adjustment patterns among Chinese international students. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(3):424–36. doi:10.1037/a0028532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Rosenthal DA, Russell J, Thomson G. Social connectedness among international students at an Australian university. Soc Indic Res. 2007;84(1):71–82. doi:10.1007/s11205-006-9075-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Kao C, Gansneder B. An assessment of class participation by international graduate students. J Coll Stud Dev. 1995;36(2):132–40. [Google Scholar]

57. Poyrazli S, Arbona C, Nora A, McPherson R, Pisecco S. Relation between assertiveness, academic self-efficacy, and psychosocial adjustment among international graduate students. J Coll Stud Dev. 2002;43(5):632. [Google Scholar]

58. Zheng W. Beyond cultural learning and preserving psychological well-being: Chinese international students’ constructions of intercultural adjustment from an emotion management perspective. Lang Intercult Commun. 2017;17(1):9–25. doi:10.1080/14708477.2017.1261673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Church AT. Sojourner adjustment. Psychol Bulletin. 1982;91(3):540–72. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Rooney EQ. Creating connections to enhance international student sense of belonging (Master’s Theses). West Chester University: USA; 2022. [Google Scholar]

61. Stout JG, Wright HM. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer students’ sense of belonging in computing: an intersectional approach. Comput Sci Eng. 2016;18(3):24–30. doi:10.1109/MCSE.2016.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Glass CR, Kociolek E, Wongtrirat R, Lynch RJ, Cong S. Uneven experiences: the impact of student-faculty interactions on international students’ sense of belonging. J Int Stud. 2015;5(4):353–67. [Google Scholar]

63. Smith RA, Khawaja NG. A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. Int Journal Intercult Relat. 2011;35(6):699–713. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Liu DWY, Winder B. Exploring foreign undergraduate students’ experiences of university. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 2014;27(1):42–64. doi:10.1080/09518398.2012.736643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Zhang Z, Brunton M. Differences in living and learning: chinese international students in New Zealand. J Stud Int Educ. 2007;11(2):124–40. doi:10.1177/1028315306289834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Suanet I, Van de Vijver FJR. Perceived cultural distance and acculturation among exchange students in Russia. J Commun Appl Soc Psychol. 2009;19(3):182–97. doi:10.1002/casp.v19:3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Riaz MA, Rafique R. Psycho-social predictors of acculturative stress and adjustment in Pakistani institutions. Pakistan J Med Sci. 2019;35(5):1441–5. [Google Scholar]

68. Kim YY. Becoming intercultural: an integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. 1st ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

69. Razgulin J, Argustaitė-Zailskienė G, Šmigelskas K. The role of social support and sociocultural adjustment for international students’ mental health. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):893. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-27123-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Gebregergis WT, Mehari DT, Gebretinsae DY, Tesfamariam AH. The predicting effects of self-efficacy, self-esteem and prior travel experience on sociocultural adaptation among international students. J Int Stud. 2020;10(2):1–357. [Google Scholar]

71. Mustaffa CS, Ilias M. Relationship between students adjustment factors and cross cultural adjustment: a survey at the northern university of Malaysia. Intercult Commun Stud. 2013;22(1):279–300. [Google Scholar]

72. Searle W, Ward C. The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Int J Intercult Relat. 1990;14(4):449–64. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(90)90030-Z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Johnson AM. A survey of attitudes and utilization of counseling services among international students at Minnesota State University. Mankato; 2010. Available from: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/485. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

74. Olatunji EA, Ogunsola A, Elenwa F, Udeh M, Oginni I, Nmadu Y, et al. COVID-19: academic, financial, and mental health challenges faced by international students in the United States due to the pandemic. Curēus. 2023;15(6):e41081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]