Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

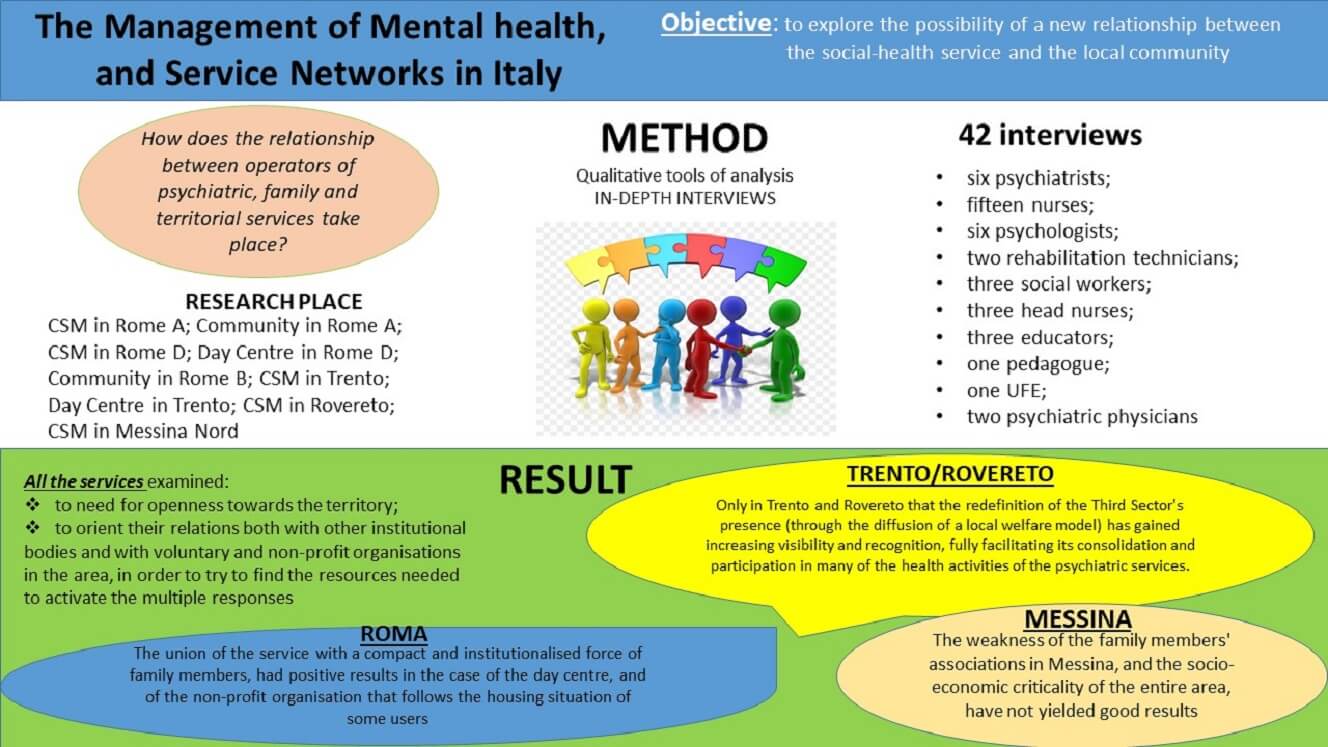

The Management of Mental Health, and Service Networks in Italy

Political and Legal Sciences Department, University of Messina, Messina, 98029, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Silvia Carbone. Email:

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(8), 927-935. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.027784

Received 15 November 2022; Accepted 08 February 2023; Issue published 06 July 2023

Abstract

Madness has attracted and frightened for centuries, and talking about this means discussing how this diversity was built and managed in different social contexts and historical periods. Not all societies have had, and still have, the same relationship with madness. It is only with the affirmation of the Modern State, and of Capitalism, that the idea of “normality” indispensable to be able to conceive diversity as something dangerously distant and different from the norm takes over. In our post-modern society, people with mental illness in Italy can resort to specialists and social-health services. But the heterogeneous answers given after the approval of law 180 appear to be increasingly diversified. In this research, much attention will be paid to how the social and health services, located in different areas of Italy (Messina, Rome, Trento) face the current growing risk of social, housing and economic isolation of these fragile subjects. The aim of the research is to explore the possibility of a new relationship between the social-health service and the local community. On the one hand, research investigates what the contribution of the services could be. On the other what the spaces of protagonism and participation of the community could be in inclusion process account. In order to better understand the differences between these two dimensions, a qualitative research approach was chosen through the conduct of in-depth interviews. In this way it was possible to investigate: (1) the partial representations characteristic of the single individual, family members, operators and stackholders in general; (2) the services around the topic dealt with is articulated. From the first results of the research it emerges that the territory can no longer be considered as an abstract entity, but becomes the social space within which the construction of a new community welfare can and must take place.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

From some archival analysis conducted by Roscioni [1] it emerges how internment practices (typical of the eighteenth century) were already widespread in Italy and can be traced back to pre-psychiatric experiences, occurring since the modern age, thus preceding Pinel’s French model of therapeutic treatment. It was Bonifacio Lupi, a famous military leader, who in 1369 created in Florence what to be considered the first Italian psychiatric hospital, at the time called the “pazzeria di Bonifacio,” institutionally dedicated to the exclusive “treatment” of the insane only from 1785. And, also in Florence, in 1643, it is possible to relocate the Casa Pia di Dorotea, a place of hospitalization where people with mental suffering could benefit from early forms of medical assistance. In Rome, on the other hand, in 1550, the Santa Maria della Pietà hospital was founded (on the initiative of a group of Christian Spaniards), destined to be considered, together with the Casa Pia di Dorotea, one of the first institutions for taking care of the insane [2]. Apart from these embryonic and marginal experiences of “psychiatric care,” the Italian system was deeply influenced by the classical French model of internment, although it differed in its social structure and slowed economic development (due to the difficulties that emerged during the unification process). Prior to the twentieth century, in Italy, the lack of a national law dealing specifically with the psychiatric sector added up to a dominant representation of the insane, imagined as a social danger to be kept tied to a bed, inside an asylum1.

An attitude found in the imagination of the population, but also in some professionals in the field, who referred to the conception of the Italian anthropological-positive school of psychiatrist Lombroso. According to this orientation, the criminal behaviour of the individual, or of the group, was explained based on innate biological characteristics, and therefore not modifiable [3].

This category of social dangerousness manifested itself openly in the formulation of Italy’s first law on psychiatric care, 36/19042, which—like the British Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 and the French law of 1838—was drafted to provide legislative regulation for the asylum institutions scattered throughout the country3. But the main objective put the implementation of social protection measures before treatment. Among the requirements for the internment of the alienated were, in fact, indicated dangerousness and public scandal as essential prerogatives for proceeding to forced hospitalization, by which the individual lost all civil rights and was entered in the criminal record; in short, he became almost like a prisoner. Therefore, what determined the alienated person’s hospitalization was not the suspected mental alienation, but his subsequent dangerous behaviour to the individual himself, or to society, of which he was a part. In this view, the interned individual, even before being considered ill, was labelled, and interned because he was dangerous.

To have him admitted, a request had to be made to the King’s Prosecutor and a medical certificate presented. Admission took place on a provisional basis; after a period of observation, the director of the asylum reported the outcome to the court, which could definitively authorise admission, without any defence intervention. From 1904 onward, from the North to the South of Italy the asylum facilities present became: fifty-nine public Psychiatric Hospitals, fifty private Psychiatric Hospitals and three Judicial Psychiatric Hospitals. Facilities that, based on Canosa’s description: “contained an average of 600 inmates; were completely closed to the outside world; inside, the use of violence was unavoidable; a strongly hierarchical pyramidal power was in force, which placed the figure of the doctor at its summit” [4]. By the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the following decade, conferences and debates had multiplied throughout the country to obtain a reform of the asylum sector, thanks to the impetus of a considerable number of hospital psychiatrists, who since 1959 had united in the AMOPI (Associazione medici delle organizzazioni psichiatriche italiane—Association of Physicians of Italian Psychiatric Organizations). After a full sixty years, a new law was passed—Law 431/1968, also known as the Mariotti Law—which, in addition to introducing voluntary hospitalization and abolishing registration with the criminal record, had the merit of promoting psychological and psychosocial intervention on behalf of the patients4. In addition, limits were imposed on Psychiatric Hospitals, establishing a maximum of 625 beds, and recognizing the need for a numerical ratio between staff and those under treatment. In other words, one operator was required for every four users.

The 1960s were also the years in which—in addition to the discovery of psychotropic drugs and the spread of new psychotherapy techniques—psychiatry finally came out of the academic and hospital walls and became a topic of public debate—thanks mainly to the contribution of Franco Basaglia5. This young psychiatrist from the hospital in Gorizia, who was able to concretize the experience of the first Italian therapeutic community, not only triggered a process of de-institutionalization, but also initiated the diffusion of the prevention phase of mental health. This is the event that Mauri identifies as the first step, on the Italian scenario, of an anti-psychiatric movement: by first and foremost demanding that the life of the person with mental suffering be rethought outside the institution, and in the social context to which he or she belongs, it recognizes and transforms him or her from an “object of institutional protection” to a “subject of social contractuality” [5]. A first step forward occurred in Italy in 1978, with Law No. 833, introducing the National Health Service, confirming the recognition and protection of the right to health and care, enshrined in the Constitution in Article 32. In part, this was the difficult challenge faced by the specific sector of Italian psychiatric care, despite the vanguard enclosed in the famous Law 180 (better known as the Basaglia Law), contained within Law 8336. With that reform operation, in fact, an attempt was first and foremost made to bind together the new requirements of prevention and rehabilitation of mental suffering, implementing a real legal upheaval. In fact, Law 180 initiated the complete abandonment of the use of terms such as dangerousness or obscenity; moreover, forced hospitalization was abolished, and Compulsory Health Treatment was to be implemented for a few days, with full and total respect for the person’s rights. Especially, it reiterated the overcoming of Psychiatric Hospitals, facilities now destined for progressive, complete emptying, as well as the social reintegration of people with mental suffering.

The different way of dealing with mental suffering in Italy, following the 180 reform, triggered a structural and organizational change in territorial services: no longer interested only in guarding the insane but also in implementing, and fostering, paths of recovery and planning for a social reintegration of the person in the context to which he or she belongs. The passage and gradual closure of Psychiatric Hospitals gave way to the construction of a broad national system of services, community-based, each of them afferent to the respective Departments of Mental Health (Dipartimenti di Salute Mentale, DSM), which in turn consists of different facilities with different types of care: Mental Health Centres (Centri di Salute Mentale, CSM); Psychiatric Diagnostic and Treatment Services (Servizi Psichiatrici di Diagnosi e Cura, SPDC) and Day Hospitals; Residential Facilities and Day Care Centres (Strutture Residenziali e Centri Diurni, CD). Nurses, who have been present in Psychiatric Hospitals as operators since Law 36 of 1904, had the task of “guarding” the person within the facility, even using coercive measures, even before therapeutic ones. Within this new organizational framework, the organization of space, understood as territory, recognized as functional, is called into question.

Law 180 was not easily and quickly implemented in all regions of Italy, and the closure of psychiatric hospitals took place—in most cases—extremely slowly. Added to this is the difficulty, encountered by many territorial services, of planning interventions for the social reintegration of the user, and of offering adequate structural and emotional support to family members. On the basis of these premises, the service, the family and the territory, today are increasingly promoting an alternative path of social reintegration of the person with mental suffering, thus avoiding the reproduction of new processes of segregation. In Italy, at present, there is no research that can describe the state of the art of psychiatric services in the entire country.

The concept of territory, in the psychiatric field, has been used and defined by various authors in a multidimensional way, often ending up becoming synonymous with citizenship and community [6]. In trying to go beyond this limited view of the territorial dimension, when speaking of territory (in this research work), we refer not only to the physical space of sociality and real life (in which the foundational processes of everyday existence take place), but above all to the set of activities and initiatives that the services examined develop in the social context to which the user belongs, through a network made up of organizations, associations, groups, cooperatives, and parishes active in the area. A territory, therefore, that does not remain in the background in a neutral and inert manner, but that is being shaped, depending on the relational content that is projected on its physical, social, and economic morphology. It is on the territory that the most significant relationships of proximity between people take place. And it is here that the confrontation between the user and the surrounding social fabric takes place; and it is therefore here that those interventions and initiatives capable of building conditions of reciprocal permeability should be structured, leading—over time—to a downplaying of fears and stigma towards “madness,” slowly setting in motion a process of profound cultural transformation. What emerges in the first instance (not only from the interviews, but also from the immediate impression that arises when one finds oneself at the psychiatric services in Trento/Rovereto, Rome and Messina), is both the history of the relationship between services and territory, and the different meaning, and the different form, that territory has respectively taken. In Trento and Rovereto, the presence of a network of associations that populate and structure the services is immediately palpable, giving liveliness and elasticity to the interventions—in terms of responses, languages, gestures, and experiences. This is thanks to a city social reality capable of offering complementary integrative spaces and resources that help enrich and define the practices of psychiatric territorial services, taking root in the social structure. In this sense, the territory-so understood and invaded, in addition to being a place of resource provision, becomes a resource itself, as a place of renewed social relations. On the other hand, the situation appears different in a city like Messina, which is economically static and socially inert, where planning capacity is left to individual operators, and where services must shoulder the full burden of rehabilitation interventions, clashing with territorial stickiness. Finally, in Rome the relationship with the territory continues along lines, of reflexive expansion and development of those potentials for socialization of needs and reunification of territorial forces. The different ways of understanding the relationship with the territory, specifically analysed below, and summarily distinguished into two different orientations, on the one hand allows the extension of the psychiatric circuit towards an “other” space, external and alternative to the service itself; on the other hand, it leads to a retreat of the service within itself, which results in an entropic attitude, which risks slowing down and preventing the construction of specific responses and solutions to the needs of individual users.

The research project comes to life from the choice to confront the new forms of organization of psychiatric services, and the new way of managing madness. The paradigmatic change (resulting from the gradual closure of asylums and the creation of a national territorial system that deals with the care and social reintegration of people with mental suffering) has, among other things, entailed a return of the subject to his or her social context of belonging, and especially to his or her family system, consequently multiplying the requests for assistance from families to the service. The new interweaving of primary and secondary, territorial, and family networks has changed demands and consequently expectations, tools, and resources. However, the increase in the modes of contact between these different entities (which are essential to support the individual rehabilitation path of the subject), is not without difficulties and conflicts [7]. In Italy, now, there is a lack of literature that analyses, specifically, the construction of the relationship between operators in psychiatric, family, and territorial services. In light of these considerations, the research presented here will investigate the predefined modes of relationship between these different actors, with reference to the various facilities examined. An attempt will be made to reflect (considering the guidelines and operational settings of the individual facilities, and how these influence the orientations of the different operators) on how these translate into the concrete creation of interstices of dialogue and collaboration with the territory and family members. We know that it is not enough to define the structural framework of an organizational reality in order to guide its operation, to promote its action and to succeed in achieving the established goals. What role, then, is the territory called upon to play today, in which a good part of psychiatry is oriented toward the involvement of these new actors? The starting hypothesis is that the different mechanisms (through which psychiatric services today structure, internally, the relationships between operators) are reflected, consequently, also in the relationship with the territory. The research, besides having a theoretical relevance (since it investigates a context still little explored by Italian social science scholars), also assumes a pragmatic relevance, because it provides insights that may be useful to guide future policy.

The question from which the research starts led to the identification of public psychiatric services as an appropriate empirical context. Considering the questions initially posed, it was chosen to consider different services: the CSMs, Communities and Day Care Centres7. By providing different services, these facilities offer different services in the area. Specifically, the facilities examined are: a CSM in Rome A; a Community in Rome A; a CSM in Rome D; a Day Centre in Rome D; a Community in Rome B; the CSM in Trento; a Day Centre in Trento; the CSM in Rovereto; and the CSM in Messina Nord. The Autonomous Province of Trento is a context that was chosen because of its ability to provide eloquent answers to the question from which the study moves, due to its good steadfastness and reliability requirements, which are above the national average. In fact, in the aforementioned Province there are well-established experiences of working on the ground and with family members, recognized and imitated in the rest of the peninsula and in many parts of the world, such as in China and Germany. The city of Rome, on the other hand, with its 8 Asl (Local Health Authorities), in addition to offering one of the most varied panoramas as far as mental health services are concerned, made it possible to include the work within an interdisciplinary research project. The CSM of Messina Nord was chosen as the control context because (due to existing relationships already woven during the volunteer and training activities carried out within the DSM), territorial and institutional “isolation” had been recorded. In order to initiate the research, a set of pilot interviews was initially used to better specify the problems, questions and hypotheses of the research itself. The indications that emerged from the pilot phase highlight the quality, strongly relational, of the issues to be investigated; the weight assumed by the subjectivity of the people involved; the importance of social representations, built around mental suffering, and the cultural references of which each person is the bearer. This set of indications has oriented to privilege qualitative tools of analysis. Thus, guided discursive interviews were chosen as a survey tool. As far as the choice of cases is concerned—in the first instance in an attempt to provide adequate support for the arguments dealt with—it was decided to interview all the managers of the facilities under consideration, with the intention of highlighting their orientations8.

The other figures taken into consideration are the staff members of the relevant psychiatric services. To recruit respondents, a letter was sent to the managers, inviting them to participate in the study and to grant us their support and welcome. The choice of cases was conducted according to a strategic and illustrative logic. For this reason, different professional figures were chosen to be interviewed, considering the differences that these roles imply in the relationship with families and the territory. The target audience for the administration of the interviews was restricted to a group of psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses and social workers permanently working within the hospital: because of their role as stakeholders directly involved in the processes of organizational, management and accountability change, they can be a good litmus test for assessing the “professional reaction”. Data were collected between October 2010 and February of 2011.

In choosing the people to be interviewed, age and gender differences were also taken into account to the extent possible to explore different circumstances. Individual interviews (n = 42) were conducted with staff: six psychiatrists in charge of the relevant centres; fifteen nurses; six psychologists; two rehabilitation technicians; three social workers; three head nurses; three educators; one pedagogue; one UFE; and two psychiatric physicians. Already through an initial narrative analysis of the interviews (from which the richness, complexity and detail of the processes examined emerged), it was evident that the necessary number of interviews had been reached to fulfil the initial purpose of the research [8]. Argumentation theory was used to support the legitimacy of the processes of extending predictability and sample size selected in this research.

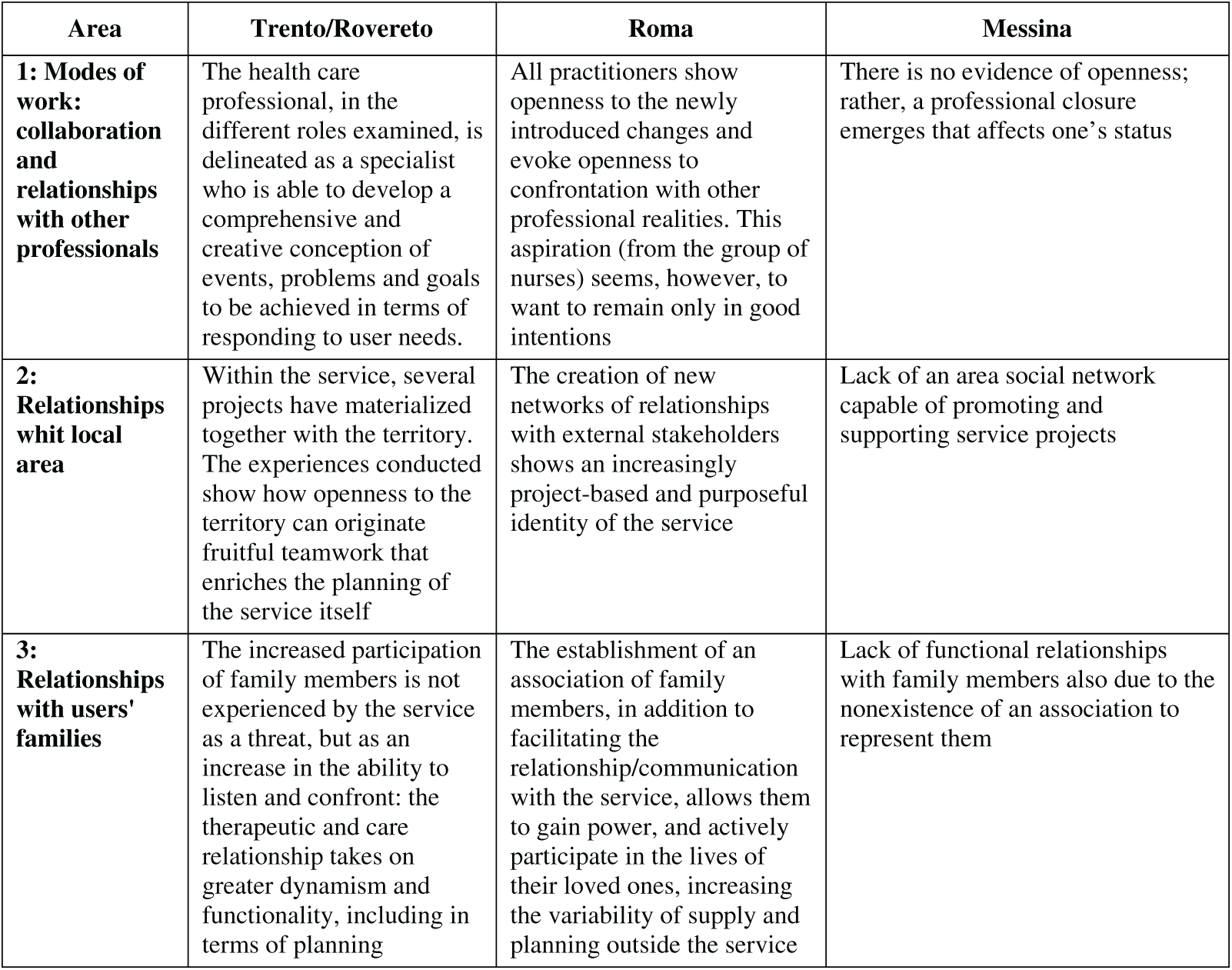

The study of these particular cases examined, allows us to draw (from the experience gained from the processing of the interviews and from the insights that emerged), useful elements to satisfy—taking up Boudon [9]—that aspiration to generality, because it can offer an extension, to similar contexts, of the predictability of the results, especially with regard to the nodes of interaction—on the basis of what Mason calls the theory of argumentation—while not forgetting the specific weight played by the individuality of each operator. Three thematic areas (conceptual cores of the research) functional to the process of understanding and interpreting the phenomenon have been identified:

- Area 1: Modes of work: collaboration and relationships with other professionals;

- Area 2: Relationships whit local area;

- Area 3: Relationships with users’ families.

The interviews were conducted on the basis of an outline that, for each area, included cognitive-type questions (aimed at investigating technical, professional, communicative... issues) and projective-type questions (aimed at bringing out the dynamics underlying attitudes).

After the 180 reform, the main challenge facing the new structure of mental health care services was opening to, and toward, the territory. This is a highly symbolic issue, because the very social system-which had for centuries guarded and confined the insane within structures completely closed to the outside world-is now called upon to welcome it back, valuing its diversity. The internal organization of the old asylums, assumed a technical knowledge on the part of the psychiatrist and nurse, based more on the analysis of pathological aspects. There was, therefore, no provision for knowledge through the relationship with the user, the family member, and the territory; therefore, the physiognomy of the service—at the architectural level—encapsulated this separation, symbolic and material, reproduced in these places and spaces, which in some cases have remained as they are, despite the passage of years. Among the facilities examined in the research, the CSM of Rome D is the one that, more than others, bears the physical signs of this historical division between the territory and the psychiatric facility, which also affected, inevitably, the family members of people with mental suffering:

First, the waiting room was a little more than 3 m × 3 m, 9 m2 room, open directly to the street and separated from the rest of the service by a door and communicating only through a small window. Patients waited in this micro waiting room, and inevitably-when there were more of them-they ended up in the middle of the street waiting. Even to attend the service bathroom they had to ring and ask permission, be escorted inside, and escorted back outside. [...] The current set-up, it’s been in place for quite some time now— it’s been like this for more than two years; now there’s a big lobby, with a dedicated desk, on view, there’s a decidedly... (Joy-CSM-RMD)

As the head of this service explains, the current change, at the architectural level, makes clear the importance of translating spaces into relationships. By acting on these, there has been an effort to create relationships between operators and users/family members, to use them as an important resource of the reintegration intervention. Tearing down a wall today, shows a willingness to reduce that distance, historically constructed on the social level, between normality and insanity. This psychiatrist, in grasping the strong nexus between place and reception, between care and relationship, in deciding to “open the doors to...” (taking up Basaglia’s words), seeks to make the operator’s head open to this “sick person,” and to what surrounds him [10]. This attitude of openness, in facilitating the encounter and relationship between the different entities that arrive in the service, determines the construction of an environment that leans toward listening to the various requests. Conversely, there are services that manage to project themselves directly and personally onto the social structure, managing to penetrate and transform it, so as to socialize needs. From the research, it is possible to see how in Trento and Rovereto, the centrality of a therapeutic relationship with the individual leaves the confines of the service, to go on to build inter-institutional relationships with the other territorial agencies of the social-health system, to obtain and activate immense resources for users, family members and the service itself. The overall physiognomy of these services does not, therefore, want to exhaust itself at the limits of the structure, but seeks to go beyond it, creating new networks of relationships, with external interlocutors, and showing in this sense an identity that is increasingly planning and purposeful. In the specific case of Rovereto:

Because we do, objectively all over the territory [...], a big territorial work [...]. So, a territorial service cannot have everything inside, it must use everything outside [...]. So, territory for us is a bit of everything: social service, associationism, cooperativism; these are the three pillars. [...] (Evan-CSM-RV)

The breaking of boundaries and the projection of service to the outside produce new places of intervention and new tools, capable of providing not only assistance, but empowerment, through work, housing, recreational placements, in order to build a condition of mutual penetrability between service and the surrounding territory. From this perspective, the territory should be understood not only as the “outside” with respect to the service, but as an extension of it, its own projection. The creation of territorial networks, widely distributed, requires a specific commitment, which in the case of the Rovereto service is carried out by the head of the facility. Evan, in the interview excerpt above, uses the word “care,” emphasizing the sense of responsibility and solicitude, which he recognizes in his commitment to interact with the other territorial agencies present. While maintaining its own specificity, in recent years the CSM of Trento, too, has promoted the importance of placing itself outward, in direct contact with the territory:

Certainly, in these years [...] it occurs to me that there have been changes even within what is our way of posing ourselves, even outwardly. Whereas before there was a bit of this tendency to say, “okay, we do our own thing within our service, within our own facilities and let’s see if we can engage the population”. On the one hand, we have activated a whole series of outreach events on the ground, we do a lot of work in high schools [...] Why should we be the ones waiting for people to come in? We are the ones doing things on the ground. (Marlene-CSM-TN)

One of the particularities of the Trento service lies in a specific approach, that of “Fareassieme,” an autonomous area of the CSM with dedicated operators (first in the whole of Italy), which was established in 1999 with the specific goal of actively involving users, family members and the territory. As Marlene, a young Fareassieme educator, explains:

I am mainly involved in Fareassieme. My job, and that of my colleagues, is to be a bit of a link between the inside and the outside. (Marlene-CSM-TN)

“Fareassieme” (doing together) are the activities, teams, and work areas promoted by the service and in which users, operators, family members and citizens are included on an equal footing. This Fareassieme approach, in becoming a fundamental component of the overall service system, has slowly transformed into a true philosophy, based on certain fundamental principles: recognising the experience and knowledge of each individual; valuing collaboration; believing in the value of personal responsibility; believing that change is always possible [11].

Notwithstanding the different management and organisation of relations between the service and the territory (in the case of Rovereto), which are encouraged and cared for by the manager and—in the case of Trento—followed by a specific local unit of the service, in both contexts the results of opening “to” and “towards” the territory are superimposable and follow the logic of strengthening and opening up the psychiatric circuit. In this sense, these services do not entrust their care-rehabilitation responsibilities to other bodies or institutions, but favour the creation of a complex network, which facilitates, first and foremost, the intersection of powers and knowledge (administrative, health, judicial and family). Moreover, this constant relationship with the social structure, as it enriches and takes root, reduces fears and stigmas; to such an extent as to set in motion a process of cultural transformation and awareness, a mutual permeability between service and territory, also evident through the numerous presence of volunteers within the psychiatric care services, as Evan tells us:

We, as strengths, have the richness of volunteering. (Evan-CSM-RV)

The complexity of the field of action (evident in the extreme articulation of activities and actors in the field) is managed, in particular, thanks to the propulsive presence of volunteering. Within this context, volunteering seems to have reached a high level of consolidation and rooting in the territory; to the extent that it constitutes a cardinal point of reference, even within the Trento service, as reported by Kirsti, an educator at the Day Centre:

We also have volunteers who come to the service. So, there is this continuous exchange between territories and service. [...] and then you also exploit them, these networks [...]. (Kirsti-CD-TN)

In Trento, what is immediately striking, in addition to the ‘youthfulness’ of most of the operators—recently graduated from university—is the presence of many volunteers. This creates a very large team within the service, made up of operators, volunteers and trainees; with different backgrounds, origins, and motivations, they manage to maintain an efficient and effective project unity. Volunteers replace operators in carrying out many activities, thus relieving the latter of “useless” burdens, and allowing them to focus directly on the user. The richness of the volunteer work thus comes back into circulation in the daily activities of the service, as the lifeblood of the structure itself. Moreover, volunteers make up for the lack of staff units that other services, such as the CSM of RomaD, complain about. The manager of the aforementioned structure explains as follows:

Reduced staffing at all levels, overload of work within the structure, and almost impossibility of being able to do anything outside. There are often barely enough staff to keep the facility open. (Joy-CSM-RMD)

Joy makes clear an institutional contextual element that needs to be considered, i.e., the downsizing of the internal staffing of the structures, despite the reverse trend of overloading the structure with other work and skills, mostly of administrative nature. The multiplicity and variety of demands flowing into the service, clashes hard with the poverty of the service’s resources. Thus, in contrast to a management that would like to enhance and increase relations between operators, families and the territory, there are institutional downsizing that go in the opposite direction. Joy draws a picture of the structural situation, of the objective limitation, which prevents the realisation of a large part of what he would like to achieve within the structure, with family members and the community. The limits of the structure examined correspond, therefore, with the scarcity of resources and the institutional overload of the service.

Continuing the analysis, the difficulty—encountered by another service examined—of creating a relationship with the territory (thus showing a concrete limitation of the application of Law 180), is that of the CSM of Messina Nord:

Now, I must tell the truth, I got tired... tired, but not for the users; I got tired above all of the lack of social network [...]. Also, because the territories are not working... and I had to take care of all the people, as the expression goes... because I could not discharge them, in the middle of the street, without help... and therefore, I was doing the work of the territory and the hospital. (Arial-CSM-ME)

The objective limitation mentioned by the social worker of the CSM of Messina is the lack of a social network. Arial has been working in the psychiatric assistance services for 33 years and, in performing the function of mediator between the user, family members and the territory—in the daily attempt to enhance the existing environmental resources—she complains about the lack of a territorial social network, capable of promoting and supporting reintegration projects. In this sense, the service remains closed in on itself; unable to offer medium- and/or long-term solutions for all users, it is forced to create interpersonal and clientelistic relationships that circumvent the professional relationship in order to find temporary solutions—as Miral, also a social worker at the CSM in Messina, explains:

In addition, we do not have the resources; therefore, often, interventions are dictated by the goodwill of the individual operator, the goodwill of the family members, and the desire to build—together with the family members and the patient—a rehabilitation path. Because then, if we look around, the tools... and the resources are really very few; therefore, we really have to invent them. (Miral-CSM-ME)

The poverty of means, the continuous reductions in the funding allocated to this specific sector of assistance, and the consequent evidence of the limits imposed on social intervention, pushes the service to see—and to look even more in family members—a possible collaborative link for the reintegration of the user. From this perspective, family members become the complementary pole of a constant attempt to influence institutional forces, to overcome administrative inertia, which slows down—and often blocks—the construction of answers and solutions for users. But, in the specific case of Messina, the city’s difficult reality continues to offer reduced spaces, and few complementary resources, which still fail to strengthen—in concrete terms—the united action of the service and family members. The city, economically in crisis and with a ‘non-existent’ labour market, where a widespread reality of unemployment, precariousness, and undeclared work reigns, does not however make it possible to create specific project spaces for fragile subjects. In this situation of institutional neglect, even Raul, one of the oldest nurses in the service, now close to retirement after 35 years of work in psychiatric care—and who in his professional experience retains the bad memory of the asylum—stresses the lack of an operational network, capable of coordinating and linking all the activities and services in the area, including family members:

We do not deal, as they say, on ‘paper’, with therapies with the team, and with meetings—or maybe this and that other activity. [...] There is no team; there is on paper, but in fact there is no team (Raul-CSM-ME)

This is—according to Raul—the motivation that forces the operator, and the service in general—to work in a condition of ‘institutional solitude’, in the performance of his professional mandate without interacting either with family members (too weak and not very active), or with other territorial agencies. Unlike what was found in Messina, faced with the impossibility of finding immediate solutions (and the lack of adequate public policies capable of facilitating and maintaining the user’s recovery pathway), the union between family members and the services of the CSM and the Community of Rome A was able to respond, positively and with concrete effects. Although lacking resources and a consolidated territorial network, the union—compact and organised—of some family members, in this case, showed its potential in exerting a strong institutional pressure, capable of obtaining results, from which all the agents involved derived concrete benefits—as Evelin, the psychologist who has been working in the service for 12 years, explains:

This allowed the birth and opening of some flats that we then supervised... so it also took the form of concrete help and work between them [...]. (Eveline-CT-RMA)

The Solaris Association was born out of the desire of several family members, participants in the family group and led within the community, to set up a non-profit organisation that would actively take care of the transition from the community to independent living. Over time, it became an element of social mediation for the rental of flats, in which a good number of users, discharged from the community, went to live.

Also, in the case of Trento, the service acts as an institutional form in ‘bargaining’ with institutional stakeholders, amplifying the negotiation, with pressure coming from family members, as Marlene explains:

The nice thing is that whatever is in the planning, the preparation, the imagination of our activities, we involve the users and the family members. This, in my opinion, is a strength, because when we are discussing with the municipality, with [...], it’s not just me as an operator, but I bring my users and family members; and, therefore, in some way, I force you to sit at the table. (Marlene-CSM-TN)

It is, therefore, through the presence of family members that in Rovereto—as in Roma D—the logic of relations with the various institutions is brought into tension; but in the case of Trento there is an extra step, and it is the ‘reunification’ of the various forces, between service and family members, which acquires fundamental importance; where the latter act as intermediaries, in relations with the institutions and with the territory.

We, as a reality in Trento, do not have [...] In the past there was this association, and I think there still is, but in a very marginal way, because most of the family members are integrated in what represent our work activities, our groups [...]. ‘Fareassieme’ is not a renouncement of the professionalism of us as professionals. (Marlene-CSM-TN)

This reunification of the various forces in Trento takes place through one of the most visible results of Fareassieme, namely the UFEs (Utenti Familiari Esperti, expert family members): a first experience in the whole of Italy, which is spreading to the rest of the peninsula and abroad, such as in Beijing and Berlin. UFEs are those who—from their own experience—have acquired an experiential knowledge that puts them in a position to favour interventions towards others. The figure of the UFE was born in 2001 in Trento, and today there are more than 40 people in the service, the majority of whom are women (i.e., 65%), with an average age of 48 years; and there are more users than family members, with a ratio of 3 to 1. The UFEs, who were initially born as simple volunteers, now work within the service; providing, in a structured and continuous manner, services recognised—to all intents and purposes—by the health authority. They are employed on a very wide range of tasks, and in practice they deal with first reception at the front office; accompaniment in crisis situations, both day and night; organisation of and participation in anti-stigma campaigns in the area; facilitation of meetings with families. In all these activities, they are constantly followed and supported by the service operators, so that they acquire adequate training. In relation to this last point, no structured training sessions are provided; however, monthly meetings are held between UFE and operators of each area of activity, in order to offer both a moment of systematic and open confrontation on reciprocal operations. During the meetings, a kind of in itinere and in-field training takes place. There are three requisites for becoming an UFE: (1) having acquired a clear awareness of the value of the use of one’s own experiential knowledge; (2) having a certain interest and motivation towards the UFE activity; (3) having basic relational skills, which allow the UFE to establish a spontaneous and positive relationship with users and family members in charge. In the case of the expert family member, he/she therefore becomes part of the life of the centre; he/she is integrated and active in internal relations, he/she is involved in the dynamics of intervention, from the planning phase to the implementation phase. As Oree, who is also within this service in Trento, explains, as happened with the association of family members for Crisanta in the CSM in RomaD, their presence was initially perceived as an invasion:

In the ward, initially there was more difficulty; they were a bit more reluctant about the figure of the UFE. I don’t know what they thought we were doing on the ward; maybe taking work away from them, or I don’t know what demands we might have had; I don’t know what they thought, we were not that well liked. After that, they saw that this figure is useful, and now they can’t do without it. (Oree-CSM-TN)

In the specific case of Trento, the service responded to this invasion through an involvement based on recognising—to the expert family members—a connotation that was able to break the classic operator/family role relations. The attribution to them of tasks and responsibilities as an operator takes place through a multitude of smaller moments in the life of the centre, leaving little space and little incentive for the strengthening of an association of family members. The acquisition of spaces of autonomy, responsibility, and fulfilment, produces, moreover, identification with those who ‘dominate’ within the Centre, constituting a break in the institutional dependence of the family member, on the Centre and on the other operators. What if it is precisely through this mode of inclusion of family members within the service (or rather their incorporation and identification with the entire structure) that their complete ‘management’ takes place? Adopting this perspective, and through a closer reading of the CSM of Trento, it is perhaps possible to find—within the structure and the relational network between operators and family members—relationship lines that remain vertical, although constitutively supported by horizontal lines. It is now possible to attempt an initial schematization of the results arising from the survey, placing them in the different thematic areas (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Results scheme.

We can affirm that all the services examined in the research demonstrate a desire—and a need—for openness towards the territory. All the facilities, in fact, orient their relations both with other institutional bodies and with voluntary and non-profit organisations in the area, in order to try to find the resources needed to activate the multiple responses. However, it is only in Trento and Rovereto that the redefinition of the Third Sector’s presence (through the diffusion of a local welfare model) has gained increasing visibility and recognition, fully facilitating its consolidation and participation in many of the health activities of the psychiatric services. The dense territorial network, which revolves around the Trento and Rovereto facilities, partly succeeds in compensating for the lack of social and economic resources that—transversally—all the services examined complain about; and, in particular, the head of the CSM of Roma D and the social workers of Messina Nord. It is precisely these ‘constraints’ of staff, space and time availability that drive the services to project outwards, to go beyond their own boundaries, in order to obtain the resources needed to fulfil their mandate. This constant bargaining of the service with other institutional bodies, if on the one hand breaks the institutional power of the service itself, on the other, pushes it to look for new ‘allies’ to exert pressure, thus fuelling bargaining.

This strategy had positive effects: for example, in Rovereto and Trento, where the entire service organisation managed to move ‘outside’ the places of intervention and the spaces of activity, finding new tools and inventing different actions; changing (also within them) the way of working, respectively ‘with’ and ‘together with’ the territory and the relatives. Also, in the CSM of Roma D, as in the CSM of Roma A, the union of the service with a compact and institutionalised force of family members, had positive results in the case of the day centre, and of the non-profit organisation that follows the housing situation of some users. On the contrary, the weakness of the family members’ associations in Messina, and the socio-economic criticality of the entire area, have not yielded good results; and, in the specific case of the CSM of Messina Nord, the necessary ‘bargaining’ is from time to time pursued, claimed and—exceptionally—obtained, only for individual cases.

A major strength of this study is our ability to highlight the experiences of people interviewed using their own words to discuss the strengths and challenges of the new management of mental illness.

Most studies examining the impact of interventions only focus on one perspective, however, the present study provides a comprehensive discussion of the benefits of service delivery and ways to strengthen and enhance their functioning.

In Italy there are no studies, with a sociological slant, that have analyzed this issue. The perspectives and recommendations discussed by interviewed are relevant for both families and health facilities the intervention. However, findings should be considered in the context of study limitations. First, as with all qualitative research, findings from this study cannot be generalized. Rather, the study provides an in-depth, nuanced examination of the perspectives of interviewed, revealing useful avenues for the implementation of newer interventions that strengthen service delivery for management.

1The laws regulating psychiatric hospitalisation in Italy in those years were those relating to the post-unification regulation of the Opere Pie, i.e., n° 753 of 1862 and n° 6972 of 1890, also known as the Crispi Law of the Opere Pie, which introduced the notion of IPAB (Istituzione di Pubblica Assistenza e Beneficenza, Public Assistance and Charity Institution). These charitable institutions, in offering their welcome and assistance to the poor and marginalised, also ‘cared’ for the ‘insane’.

2Law No. 36 of 14 February 1904, published in the Official Gazette No. 43 of 22 February, contained the provisions on asylums and alienated persons, and the methods of their custody and care.

3With the French law of 30 June 1838, inspired by Esquirol’s work mentioned above, the French government decreed that all départements had to build a public asylum.

4Law No. 431 of 18 March 1968, published in the Official Gazette No. 101 of 18 March.

5In 1961, the psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, with the help of nurses, psychologists, and the inmates themselves, made an attempt to transplant the therapeutic community formula—theorised by Maxwell Jones in England in 1942—into six hospital wards in the Psychiatric Hospital of Gorizia. Therefore, not only did the gates of the asylum open and all the instruments of restraint and methods of torture previously used on people were put aside, but an attempt was made to create a structure capable of encouraging encounters—between free subjects and different professional roles—with the primary objective of a circular exchange, made up of listening and understanding, through the affirmation of an equal interpersonal relationship, which would facilitate—in the fragile subject—the development of paths of empowerment and autonomy.

6Law No. 180 of 13 May 1978, published in the Official Gazette No. 133 of 16 May, on voluntary and compulsory health assessment and treatment.

7All the CSMs analysed in the research carry out home care and outpatient care in their territory, remaining open 12 h a day, 6 days a week. Only the CSM in Trento remains open also on Sunday mornings. These services have the task of creating, for each user, a global profile of the type of suffering and needs, in order to draw up a customised therapeutic project. Day care centres are semiresidential facilities, with therapeutic-rehabilitative functions, located in the territorial context, and equipped with a team, possibly integrated by operators of social cooperatives and voluntary organisations. Within the framework of customised therapeutic-rehabilitative projects, the centre enables people to experiment and learn skills in self-care, in activities of daily living and in individual and group interpersonal relations, also with a view to job placement. Communities are facilities that accommodate the user with mental suffering in a residential regime and have a maximum of 20 beds. Access to these services must take place exclusively on the basis of a specific programme agreed between the services, the users and their families.

8Only the head of the Trento CSM, due to numerous institutional commitments, could not grant the space for an interview.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

1. Roscioni L. Il governo della follia. Ospedale, medici e pazzi nell’età moderna [Internet]. Mondadori: Milano; 2003. [Google Scholar]

2. Magherini G, Bioti V. L’isola delle Stinche e i percorsi della follia a Firenze nei secoli XIV–XVIII [Internet]. Ponte alle Grazie: Firenze; 1992. [Google Scholar]

3. Lalli N. L’isola dei Feaci. Percorsi psicoanalitici nella storia della psichiatria, nella clinica, nella letteratura [Internet]. Roma: Nuove Edizioni Romane; 1997. [Google Scholar]

4. Canosa R. Storia del manicomio in Italia dall’unità ad oggi [Internet]. Feltrinelli: Milano; 1979. [Google Scholar]

5. Mauri D. La libertà è terapeutica? L’esperienza psichiatrica di Trieste [Internet]. Feltrinelli Editore: Milano; 1983. [Google Scholar]

6. Hillery G. Definitions of community: areas of agreement. Rural Sociol [Internet]. 1995;20;(4):111–24. [Google Scholar]

7. Maone A. Le chiavi di casa. Potenzialità e limiti dell’approccio di supported housing [Internet]. In: Psichiatria di Comunità, vol. V n°4 dicembre. Roma: Centro Scientifico Editore; 2006. [Google Scholar]

8. Glauser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research, New York, Aldine, (trad. it.: La scoperta della grounded theory. Strategie per la ricerca qualitativa [Internet]. Armando Editori: Roma; 1967. [Google Scholar]

9. Boudon R, Bourricaud F. Le dictionnaire critique de la sociologie [Internet]. Paris; 1991. [Google Scholar]

10. Mauri D. La libertà è terapeutica? L’esperienza psichiatrica di Trieste [Internet]. Milano: Feltrinelli Editore; 1983. [Google Scholar]

11. de Stefani R. Il fareassieme di utenti, familiari e operatori nel Servizio di salute mentale di Trento. Rivista Sperimentale di Freniatria [Internet]. 2007;2007:133–50. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools